Abstract

Background:

Among a variety of complex factors affecting a decision to take family medicine as a future specialisation, this study focused on demographic characteristics and assessed empathic attitudes in final year medical students.

Methods:

A convenience sampling method was employed in two consecutive academic years of final year medical students at the Faculty of Medicine in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in May 2014 and May 2015. A modified version of the 16-item Jefferson Scale of Empathy – Student Version (JSE-S) was administered to examine self-reported empathic attitudes. An intended career in family medicine was reported using a five-point Likert scale.

Results:

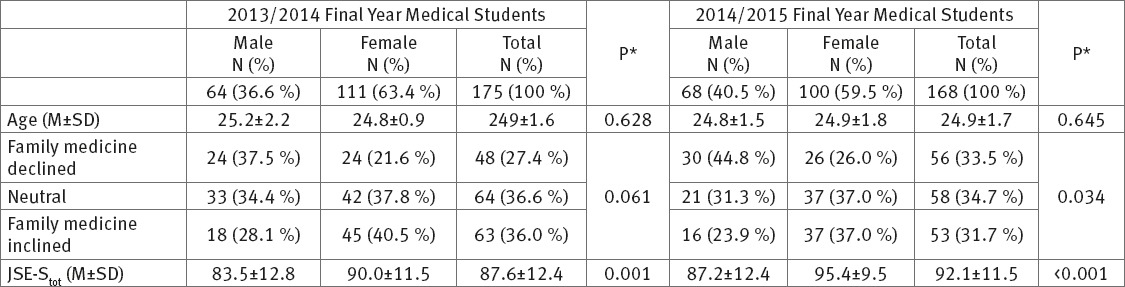

Of the 175 medical school seniors in study year 2013/14, there were 64 (36.6%) men and 111 (63.4%) women, while in the second group (study year 2014/5), there were 68 (40.5%) men and 100 (59.5%) women; 168 students in total. They were 24.9±1.6 (generation 2013/4) and 24.9±1.7 (generation 2014/15) years old. Thirty-six percent of the students in the academic year 2013/14 intended to choose family medicine as a future career, and a similar proportion in academic year 2014/15 (31.7%). Gender (χ2=6.763, p=0.034) and empathic attitudes (c2=14.914; p=0.001) had a bivariate association with an intended career choice of family medicine in the 2014/15 generation. When logistic regression was applied to this group of students, an intended career choice in family medicine was associated with empathic attitudes (OR 1.102, 95% CI 1.040-1.167, p=0.001), being single (OR 3.659, 95% CI 1.150-11.628, p=0.028) and the father having only primary school education (OR 142.857 95% CI 1.868, p=0.025), but not with gender (OR 1.117, 95% CI 0.854-1.621, p=0.320).

Conclusion:

The level of students’ father’s education, and not living in an intimate partnership, increased the odds on senior medical students to choose family medicine, yet we expected higher JSE-S scores to be associated with interest in this speciality. To deepen our understanding, this study should be repeated to give us solid grounded insight into the determinants of career choice; associations with gender in particular need to be re-tested.

Keywords: medical students, empathic attitudes, father’s educational status, career choice, family medicine

1. INTRODUCTION

In many European countries, there is lack of interest in family medicine among medical school graduates (1, 2), in spite of the utmost importance of primary care in health care systems all over the world (3). For students with an interest in family medicine, it is essential to have those personal and professional characteristics that patients expect and value in their family physician (FP). Delgrado and co-authors (4) identified the main expectations in patients, i.e. to be actively listened to and to be treated with the interest of the physician, although these expectations were not found to be homogenous in all clinical settings. Most patients also valued the physicians’ communication skills over the strictly medical components of the treatment (4).

Factors Influencing Family Medicine Being Chosen as a Career

There are complex reasons for selecting family medicine as a career choice, identified (5) and categorised into several groups (6-12). The first group is comprised of socio-demographic factors, i.e. female gender, growing up in a rural area, and having under-educated parents (without a university degree) (7-10), while the second group includes personal characteristics of future physicians, i.e. positive social self-image, personal ambition, importance of income, and a wish to harmonise work and personal life (6). The third group of factors is related to the recognition of the importance of family medicine specifics, i.e. continuity of care, diversity, and community orientation (7-9), and the fourth group covers attitudes; attitudes towards this discipline have been shown to be especially important, since they can and should be addressed through education (13).

Students’ family practice placements during medical school training and personal contact with their own FP have been identified as the principal factors in students who were positively influenced (14). There are some reports that the motivating effect of this training is not long-lasting (2, 15); female graduate students were reported to change their interest in favour of other specialities (2). However, it has been shown that practically-oriented medical curricula in both the earlier and later stages of undergraduate medical education raised the output of future FPs (14). In Slovenia, family medicine training is an obligatory subject for sixth-year students. The programme lasts for seven weeks; students spend four days a week in a practice with a clinical mentor, while one day a week is dedicated to teaching in the department. The details of the programme have already been published (15).

The Role of Empathic Attitudes in Students’ Career Choice

In the context of health care, empathy as a predominantly cognitive attribute, combined with a capacity to communicate understanding of the patient’s experiences, concerns, and perspectives and an intention to help has been explained and measured by Hojat and co-workers (17). Recent empirical evidence suggests that empathy is associated with improved clinical outcomes (18) and decreased anxiety in patients (19, 20). The latter has been shown to be due to engaged communication and linked to physiological effects (20).

There is insufficient evidence to support the use of empathy measures in the selection of students for medical courses (21). It has been shown that students interested in ‘people-oriented specialities’ had higher empathy levels compared to those preferring ‘technology-oriented specialities’ (22).

Family medicine is a ‘people-oriented speciality’, considering the long-term relationship with patients and holistic approach towards patient care (23,24). The feminisation of family medicine is present all over the world and raises questions about the future provision of services and the position of the discipline (25, 26). More female GPs, shown to be more empathic, means longer consultations, more patient-centred communication and a greater involvement in preventive services, counselling and psychotherapy (27).

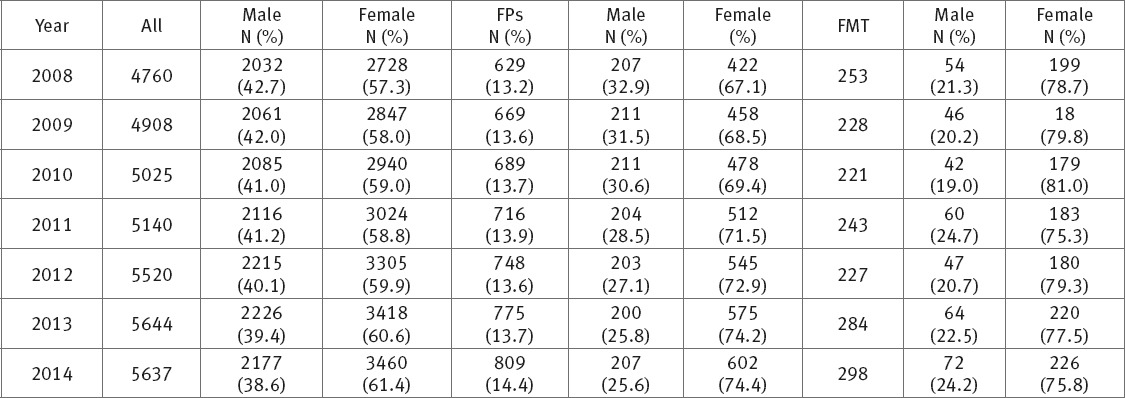

Women have prevailed for many years in the medical profession in Slovenia (see Table 1) (28); the proportion of women as physicians, GPs and also family medicine trainees has been significantly higher (p<0.001), and therefore a career in family medicine could be considered a feminine choice.

Table 1.

Gender Structure of all Slovenian Physicians, Family Physicians and Family Medicine Trainees for the Past Seven Year Period (2008-2014) All – All physicians in Slovenia FP – Family physicians FMT – Family Medicine Trainees

Since our previous research on empathic attitudes showed differences in the total score of JSE-S between female and male students (t=3.652, p=0.001) (31), this study aimed to re-test this finding, but more importantly to explore family medicine as an intended career choice and its associations with socio-demographic characteristics and empathic attitudes in final year medical students.

2. METHODS

Participants and Procedure

A convenience sampling method was employed in two consecutive academic years of final year medical students at the Faculty of Medicine in Ljubljana, Slovenia, in May 2014 and May 2015, within the obligatory course “family medicine training”. Participants were provided with an explanatory statement and were informed that participation was voluntary. Students needed approximately fifteen minutes to complete the questionnaire.

Instruments

Based on previous research in Slovenia (29), the empathic attitudes of the students were assessed using a modified 16-item JSE-S covering Perspective Taking and Standing in the Patient’s Shoes. Ten of the items in the original JSE-S are positively worded, while the other ten are negatively worded to reduce the confounding effect of the “acquiescence response style”, i.e. the tendency to consistently agree or disagree (yea/naysayers). The possible score range was 20-140; the higher the mean score, the higher the self-reported empathy level (22). Students rated their level of empathy for each item on a seven-point Likert scale (1–strongly disagree, 7–strongly agree), with higher scores indicating higher levels of empathy. The possible range of the modified 16-item JSE-S was 16 to 112. The total JSE-S score was used as a measure of self-assessed empathic attitudes in students.

Interest in family medicine as a chosen speciality was self-assessed using a five point Likert scale (1–no interest, 5–(almost) certain to become a GP). According to their preference for family medicine, students were categorised as 1. unlikely to become a GP (1 or 2 on the Likert scale) – family medicine disinclined, 2. neutral (3 on the Likert scale), and 3. likely to become a family physician (4 or 5 on the Likert scale) – family medicine inclined.

Data Analysis

The JSE-S was scored in line with the scoring algorithm for participants who completed 80% or more of the items. If a participant failed to answer four or fewer items, the missing values were replaced with the mean score of the completed items. The JSE-S score was calculated as the sum of the modified JSE-S version (22) involving the selected sixteen items (without items 1, 5, 18, and 19). Reliability was estimated using the Cronbach alpha (Cronbach α2013/4=0.84 and Cronbach α2014/5=0.83).

Descriptive statistics was used to analyse the main characteristics of the students considering their gender, age and level of (dis)agreement of items. The JSE-S score differences were examined by gender, age, and family medicine inclination. The differences in the JSE-S were assessed using difference tests for two or more independent samples, i.e. the t-test, the Mann-Whitney U test and the Kruskal-Wallis test. Data normality was tested by the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. The association between gender and family medicine inclination was examined using the chi-square test. When analysing factors associated with an intended career choice in family medicine, family medicine inclined and declined students were compared. Binary logistic regression was used to evaluate associations between gender, age and empathic attitudes and family medicine inclination in the students. Gender, age and the JSE-S score were selected as independent variables in the first regression modelling, while in the second the students’ family background-related variables were added. Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows (version 22.0). The level of significance was set at p≤0.05.

3. RESULTS

Characteristics of the Study Sample

Of 175 medical school seniors in study year 2013/14 (97.3 % response rate), there were 64 (36.6%) males and 111 (63.4%) females, while in the second group (study year 2014/5, 96.6 % response rate), there were 68 (40.5%) males and 100 (59.5%) females of a total 168 students, aged 24.9±1.6 (generation 2013/4) and 24.9±1.7 (generation 2014/15).

The highest proportion of students in both groups was of those undecided about their future speciality (n2013/4=64 (36.6%), n2014/5=58 (34.7%)). In the second group (study year 2014/5) there were fewer students with an interest in family medicine and more of those without, compared to those in study year 2013/4.

Gender was found to be associated with JSE-Stot; in women JSE-Stot was approximately 9% higher than in men (p<0001). In the study year 2013/4 there were no gender differences regarding their interest in family medicine as a future speciality and career choice (χ2=5.603, df=2, p=0.061), while in the second group2014/15 of final year students, the proportion of men was higher in the family medicine inclined group (χ2=6.763, df=2, p=0.034). In this group, a significant association between an intended career choice in family medicine and the JSE-S score was also identified (c2=14.914, p=0.001).

The characteristics of this study sample are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

The Study Sample by Age, Gender, Empathic Attitudes and Family Medicine Inclination. *t-test, hi- square, Mann-Whitney U test

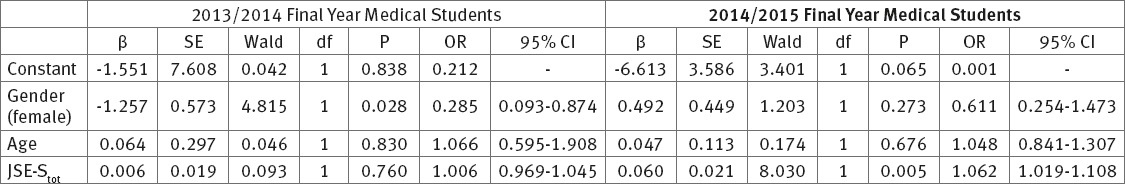

Associations between Family Medicine Inclination, Empathic Attitudes and Gender and Age: Multivariate Regression Modelling

Testing the hypothesis that intended career choice in family medicine was associated with gender and empathic attitudes in final year medical students, a multivariate modelling was performed for each group of final year students (c22013/4=6.871, df2013/4=3, p2013/4=0.076, c22014/5=16.140, df2014/5=3, p2014/5=0.001), explaining 12.1% and 18.5% of variance respectively. The results are presented in Table 3.

Table 3.

Factors Associated with Family Medicine Inclination in two Generations of Final Year Medical Students: Logistic Regression Modelling (c22013/4=6.871, df2013/4=3, p2013/4=0.076, R22013/4=0.121, c22014/5=16.140, df2014/5=3, p2014/5=0.001, R22014/5=0.185) β – regression coefficient, SE – standard error, Wald – Wald`s test, OR–exp(b) / odds ratio

Omnibus tests confirmed statistical significance (p£0.05) only for the study year 2014/5 modelling; empathic attitudes were associated with family medicine as intended career choice (p=0.005£0.05). The effect seems to be relatively small; however, comparing the students with the lowest (JSE-Stot=39) and the highest (JSE-Stot=110) self-assessed empathic attitudes showed that the odds for intended career choice in students with the highest JSE-S score was over four times higher.

Final Year 2014/5 Students: Associations between Family Medicine Inclination, Family Background and Previous Experience with the Health Care System

In the 2014/5 study year group, parents with a high educational status, i.e. Master’s degree or higher, prevailed (nfather=84 (50.6%), nmother=91 (54.4%)), while the fewest parents had only basic education, i.e. primary school (in Slovenia the leaving age of primary school is 14; nfather=11 (6.6%), nmother=5 (3.0%)).

The majority of students reported that their parents were employed either in the public sector or in the economy (nfather=97 (58.0%), nmother=120 (71.9%)); 3.0% (n=5) of fathers and 2.4% (n=4) of mothers were unemployed. Most students (n=120 (72.7%)) have siblings (M=1.1±1.1) and about a third of all the students (n=54 (32.7%)) had a close relative who was a physician. Some (n=61 (36.5%)) still lived with their parents, while about a quarter of all the students rented an apartment (n=39 (23.4%), and the others either lived in their own apartment (n=36 (21.6%)) or in a dormitory (n=28 (16.8%)). Most students lived in an intimate partnership (n=99 (59.3%)) or reported being single (n=62 (37.1%)), while five (3.0%) were married.

More than half (n=101 (60.5%)) of the 2014/5 generation seniors reported that they had had negative experiences with the health care system in the past, but even more of them (n=119 (71.3%)) rated their past experience with physicians as good and 15.5% (n=25) as very good. None of the students reported a very bad past experience with physicians of any speciality.

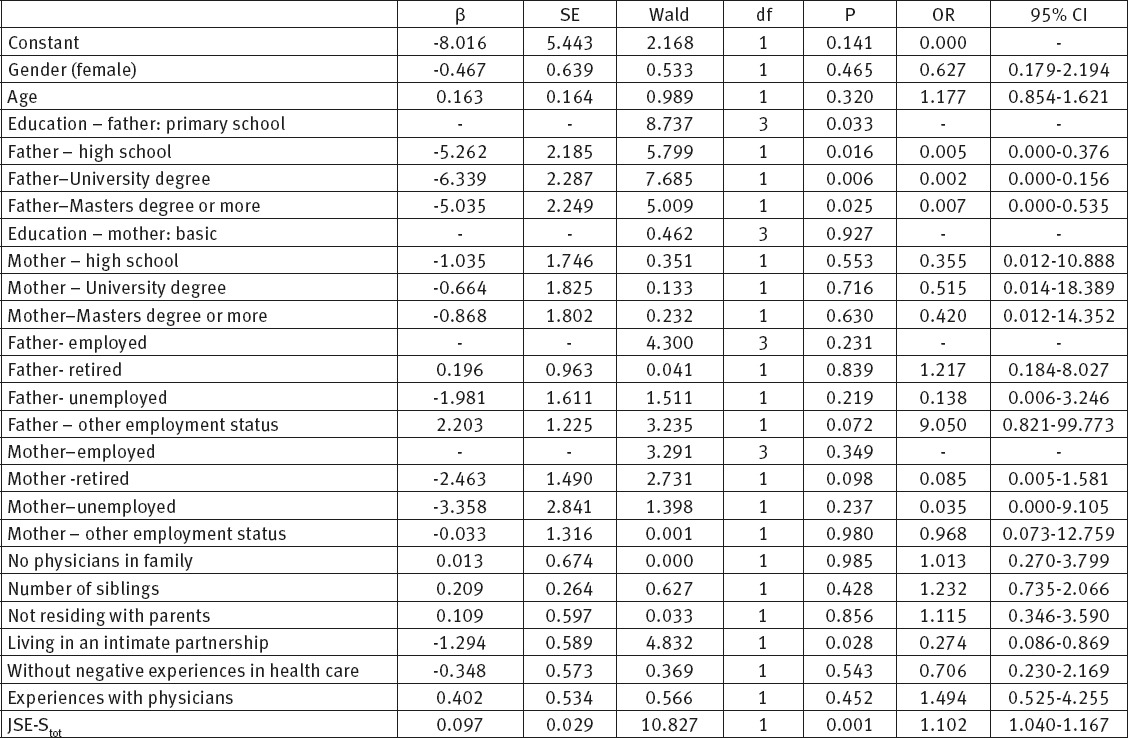

Logistic regression modelling procedures were used to partition the variance across a variety of the participants’ characteristics and experiences (c2=16.149, df=3, p=0.001), explaining 18.5% of the variance of family medicine inclination. The results are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

Multiple Logistic Regression Modelling Explaining Intended Career Choice in Family Medicine for the 2014/5 Study Year Seniors (c2=16.149, df=3, p=0.001, R2=0.185). β – Regression coefficient. SE – standard error. Wald – Wald`s test. OR–exp(b) / odds ratio

Of 13 variables, three were confirmed as being associated with an interest in family medicine, i.e. father`s educational status (β=-5.262, p=0.016), being single (β=-1.294, p=0.028) and empathic attitudes (JSE-Stot, β=0.097, p=0.001).

4. DISCUSSION

The data in this study on self-assessed empathic attitudes and family background in medical school seniors did not show the female gender to be significantly associated with family medicine inclination. However, students with an intended career in family medicine had a higher JSE-Stot score; less frequently lived in an intimate partnership and had a father with a lower level of education (Table 4). The higher JSE-Stot score in students with an intended career choice in family medicine was in line with the findings of other researchers (22,29-30).

Several studies have shown that the choice of specialities of medical school graduates is related to gender (9-12). However, Heiliger (31) found gender to be a weak predictor for a career choice in family medicine, and Scoot and co-authors (32) were unable to confirm the influence of gender on a career choice in family medicine. The authors explained the finding by the increasing number of women in medical school, and emphasised that in this era of the feminisation of medicine, interest in family medicine was not gender-related (31). The results of the present study (Table 4) can be interpreted in the same way, also taking into account the gender structure of physicians in Slovenia (Table 1).

In our study, parents’ education was found to be associated with family medicine inclination (Table 4), which is concordant with the findings of others, who reported that students who named family medicine as their top residency choice less frequently had parents with a postgraduate university degree (31). Furthermore, our study showed the father`s educational status as being associated with the highest odds for a medical school senior to choose family medicine as a future career (Table 4). Further research is to be conducted to test the association between lower educational status and a rural living environment, which could bring helpful insight into the factors associated with family medicine inclination. Generally speaking, people living in rural and/or deprived areas in Slovenia are less educated (33). Apart from that, a rural origin was found to be one of the key factors in students choosing family medicine as a future career (10,16).

The results of this study differ from most of the previous work suggesting living in a partnership as a predictor of career choice in family medicine (30,31), since married students tended to prefer family medicine over other medical specialities due to its compatibility with family life (33).

We agree with others who claim that there is no ideal selection tool to find the most appropriate students for the discipline (34). Taking into account that students with lower socioeconomic status frequently originate from rural areas and have higher interest in working in rural practices after graduation (35), and that the most serious lack of family physicians in Slovenia has been in rural areas, it could be worth trying to recruit students from lower socio-economic backgrounds to family medicine by offering them some advantages (e.g. affordable accommodation, additional income while working in out-of-hours services).

Strengths and Limitations of the Study

There were several limitations to our research. The study was cross-sectional with two consecutive data collection periods. The findings were based on data gathered from a single institution, arguably a sample of convenience. Convenience sampling, while making it easier to recruit participants, limits the capacity to control for non-respondent bias. Therefore, generalisation from these findings may be somewhat limited.

Due to the cross-sectional design of the study we were only able to collect data on intended career choice and not on definite career choice. The finding that professional preferences are relatively stable from graduation to the time of choosing a speciality somewhat mitigates this limitation (36).

Personality traits in students were not analysed, yet have been known to predict both academic and professional performance (37). This shall be considered in further, more complex research, given that this was the first study which focused on the association between empathic attitudes (measured by JSE-Stot score) and career choice in Slovenian medical school students, and, as far as these authors know, also in the region.

Future research is planned to be longitudinal, following the intended career choice of students from the beginning. Aside from the previously mentioned personality traits, monitoring other determinants of career choice, such as attitudes, values and coping strategies, would contribute to this evolving body of research.

5. CONCLUSIONS

In medical school seniors, the odds of choosing family medicine as a future speciality lessened with a higher-than-primary-school educational status of fathers and single marital status, and increased with the JSE-Stot of self-assessed empathic attitudes. A family medicine career choice was not shown to be gender-related. This could be an important message for the future development of the discipline – not gender, but other characteristics and attitudes in students, could be factors influencing a career choice in family medicine. Therefore it is up to those teaching family medicine to develop not only clinical competences, but also to empower the humanistic values of future FP.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank to all the students fulfilling the questionnaires and to our secretary Mrs. Lea Vilman for technical support.

Footnotes

• List of abbreviations: All – all physicians in Slovenia, FP – family physician, FMT – Family Medicine Trainees, β – Regression coefficient, SE – Standard Error, Wald – Wald`s test, OR–exp(b) / Odds Ratio,

• Ethics approval and consent to participate: The research protocol was approved by the Commission of the Republic of Slovenia for Medical Ethics, decision number 143/02/11, on January 31, 2011

• Consent for publication: Not applicable.

• Availability of data and materials: Data supporting our findings can be found in Additional Files.

• Competing interests: The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

• Funding: The study was partly supported by the Slovenian Research Agency, Research Programme Code P3-0339.

• Authors’ contributions: PS and MPS conceived the study. MPS carried out the coordination and drafted the manuscript. PS participated in interpretation and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lambert T, Goldacre M. Trends in doctors’ early career choice for general practice in UK. Br J Gen Pract. 2011;61(588):e397–403. doi: 10.3399/bjgp11X583173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gibis B, Heinz A, Rudiger J, Muller KH. The career expectations of medical students: findings of a nationwide survey in Germany. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2012;109(18):327–32. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2012.0327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lefevre JH, Roupret M, Kerneis S, Karila L. Career choices of medical students: a national survey of 1780 students. Med Educ. 2010;44(6):603–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03707.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Maiorova T, Stevens F, van der Zee J, Boode B, Scherpbier A. Shortage in general practice despite the feminisation of the medical workforce: a seeming paradox? A cohort study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8:262. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Starfield B. Primary care: an increasingly important contributor to effectiveness, equity, and efficiency of health services. Gac Sanit. 2012;26(Suppl1):20–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delgado A, Lopez-Fernandez LA, De Dios Luna J, Gil N, Jimenez M, Puga A. Patient expectations are not always the same. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2008;62(5):427–34. doi: 10.1136/jech.2007.060095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yuko Takeda Y, Morio K, Snell L, Otaki J, Takahashi M, Kai I. Characteristic profiles among students and junior doctors with specific career preferences. BMC Med Educ. 2013;13:125. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-13-125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kiolbassa K, Hermann K, Loh A, Szecsenyi J, Joss S, Goetz K. Becoming a general practitioner–Which factors have most impact on career choice of medical students? BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12:25. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Scott I, Wright B, Brenneis F, Brett-MacLoad P, McCaffrey L. Why would I choose a career in family medicine? Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(11):1956–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Senf J, Campus-Outcalt D, Kutob R. Factors related to the choice of family medicine: a reassessment and literature review. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2003;16(6):502–12. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.16.6.502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tolhurst H, Stewart M. Becoming a GP–a qualitative study of the career interest of medical students. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34(3):204–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gill H, McLeod S, Duerksen K, Szafran O. Factors influencing medical students’ choice of family medicine: effects of rural versus urban background. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58(11):e649–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zurro AM, Villa JJ, Hijar AM, Tuduri XM, Puime AO, Coello PA, et al. Medical students’ attitudes toward family medicine in Spain: a state-wide analysis. BMC Fam Pract. 2012;29(13):47. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-13-47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Natanzon I, Ose D, Szecsenyi J, Campbell S, Roos M, Joos S. Does GPs’ self-perception of their professional role correspond to the social self-image? A qualitative study from Germany. BMC Fam Pract. 2010 Feb 4;11:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-11-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petek Šter M, Švab I, Šter B. Prediction of intended career choice in family medicine using artificial neural networks. Eur J Gen Pract. 2015;21(1):63–9. doi: 10.3109/13814788.2014.933314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parker JE, Hudson B, Wilkinson TJ. Influences on final year medical students’ attitudes to general practice as a career. J Prim Health Care. 2014;6(1):56–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Švab I, Petek Šter M. Long-term evaluation of undergraduate family medicine curriculum in Slovenia. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2008;136(5-6):274–9. doi: 10.2298/sarh0806274s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deutsch T, Lippmann S, Frese T, Sandzholzer H. Who wants to become a general practitioner? Student and curriculum factors with choosing a GP career–a multivariable analysis with particular consideration of practice-oriented GP course. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2015;33(1):47–53. doi: 10.3109/02813432.2015.1020661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hojat M, Louis DZ, Markham FW, Wender R, Rabinowitz C, Gonnella JS. Physicians’ empathy and clinical outcomes for diabetic patients. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):359–64. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086fe1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Williams B, Brown T, McKenna L, Boyle MJ, Palermo C, Nestel D, et al. Empathy levels among health professional students: a cross-sectional study at two universities in Australia. Adv Med Educ Pract. 2014;5:107–13. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S57569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Butow P, Maclean M, Dunn S, Tattersall M, Boyer M. The dynamics of change: cancer patients’ preferences for information, involvement and support. Ann Oncol. 1997;8(9):857–63. doi: 10.1023/a:1008284006045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hemmerdinger JM, Stoddart SD, Lilford RJ. A systematic review of tests of empathy in medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2007;7:24. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-7-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stepien KA, Baernstein A. Educating for Empathy. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(5):524–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00443.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hojat M, Gonnella JS, Nasca TJ, Mangione S, Vergare M, Magee M. Physician empathy: definition, components, measurement, and relationship to gender and specialty. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1563–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Heyrman J, editor. European Academy on Teachers in General Practice. Leuven: EURACT; 2005. [Assessed 7.5.2017]. The EURACT Educational Agenda. http://euract.woncaeurope.org/sites/euractdev/files/documents/publications/official-documents/euract-educationalagenda.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 26.McKinstry B, Colthart I, Katy E, Hunter K. The feminization of the medical work force, implications for Scottish primary care: a survey of Scottish general practitioners. BMC Health Serv Res. 2006;6:56. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-6-56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Teljur C, O'Down T. The feminisation of general practice- crisis or business as usual? Lancet. 2009;374(9696):1147. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61742-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Biringer A, Carroll JC. What does the feminisation of family medicine mean? CMAJ. 2012 Oct 16;184(15):1752. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.120771. PubMed PMID:23008491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Medical chamber of Slovenia Members. [Assessed 7.5.2017]. http://www.zdravniskazbornica.si/f/4470/clanstvo-010511 .

- 30.Petek Šter M, Selič P. Assessing empathic attitudes in medical students: the re-validation of the Jefferson scale of empathy–student version report. Zdr Varst. 2015;54(4):282–92. doi: 10.1515/sjph-2015-0037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tavakol S, Dennick R, Tavakol M. Empathy in UK medical students: differences by gender, medical year and specialty interest. Educ Prim Care. 2011;22(5):297–303. doi: 10.1080/14739879.2011.11494022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Heiligers PJ. Gender differences in medical students’ motives and career choice. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12:82. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-12-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, Brenneis F, Banner S, Boone J. Determinants of choosing a career in family medicine. CMAJ. 2011;183(1):E1–8. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.091805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Education in Slovenia. Final data, January 1 2011. [Assessed 7.5.2017]. http://www.stat.si/StatWeb/glavnanavigacija/podatki/prikazistaronovico?IdNovice=4412 .

- 35.Barshes NR, Vavra AK, Miller A, Brunicardi FC, Goss JA, Sweeney JF. General surgery as a career: a contemporary review of factors central to medical student specialty choice. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199(5):792–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.05.281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Puddey IB, Mercer A, Playford DE, Pougnault S, Riley GJ. Medical student selection criteria as predictors of intended rural practice following graduation. BMC Med Educ. 2014 Oct 14;14:218. doi: 10.1186/1472-6920-14-218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, Brenneis F. Stability of medical student career interest: a prospective study. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1260–7. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826291fa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hojat M, Zuckerman M. Personality and specialty interest in medical students. Med Teach. 2008;30(4):400–6. doi: 10.1080/01421590802043835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]