Abstract

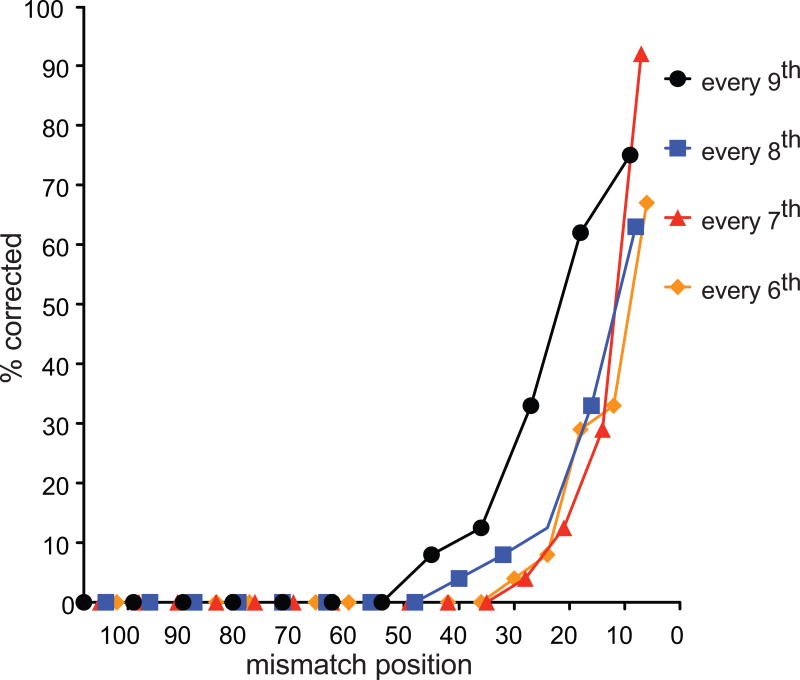

The RecA/Rad51 family of recombinases execute the critical step in homologous recombination (HR): the search for homologous DNA to serve as the template during DNA double-strand break (DSB) repair1–7. Although budding yeast Rad51 has been extensively characterized in vitro3,4,6–9, the stringency of its search and sensitivity to mismatched sequences in vivo remain poorly defined. We analyzed Rad51-dependent break-induced replication (BIR) where the invading DSB end and its donor template share 108 bp homology and the donor carries different densities of single-bp mismatches (Fig. 1a). With every 8th bp mismatched, repair was ~14% compared to completely homologous sequences. With every 6th bp mismatched, repair was >5%. Thus completing BIR in vivo overcomes the apparent requirement for at least 6–8 consecutive paired bases inferred from in vitro studies6,8. When recombination occurs without a protruding nonhomologous 3′ tail, mismatch repair protein Msh2 does not discourage homeologous recombination. However, when the DSB end contains a 3′ protruding nonhomologous tail, Msh2 promotes rejection of mismatched substrates. Mismatch correction of strand invasion heteroduplex DNA is strongly polar, favoring correction close to the DSB end. Nearly all mismatch correction depends on the proofreading activity of DNA polymerase δ, although Msh2-Mlh1 and Exo1 influence the extent of correction.

Each monomer of RecA/Rad51 binds 3 nt of single-strand DNA (ssDNA). The resulting nucleoprotein filament engages in a search for homologous double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) to carry out strand exchange, the first step in DSB repair by HR3. A recent in vitro study concluded that an initial, stable encounter between RecA/Rad51-bound ssDNA and mismatched dsDNA requires 8 perfectly matched bases, and that extension of the heteroduplex proceeds in steps of 3 nt bound to each Rad51/RecA monomer6. Another study, concluded that RecA-promoted strand exchange required segments of 8 nt that could tolerate a single mismatch7.

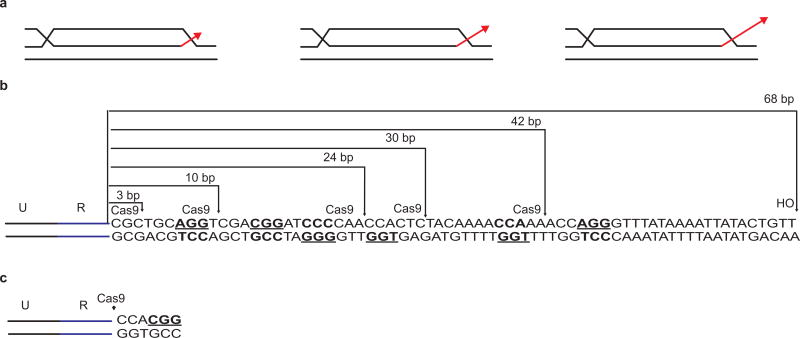

To examine the stringency of Rad51-mediated recombination in vivo, we designed substrates that placed mismatches along a 108-bp donor template and monitored DSB repair by break-induced replication (BIR). In BIR, only one DSB end shares homology with a donor (Fig. 1a). Strand invasion between the resected, Rad51-coated single-stranded DSB end and the donor results in recruitment of DNA polymerases and copying of sequences to the end of the chromosome arm10. Our design sidesteps the need to excise a 3′-ended nonhomologous tail from the invading end before initiating new DNA synthesis11–15. Tail removal proves to be a confounding variable when measuring HR success (see below).

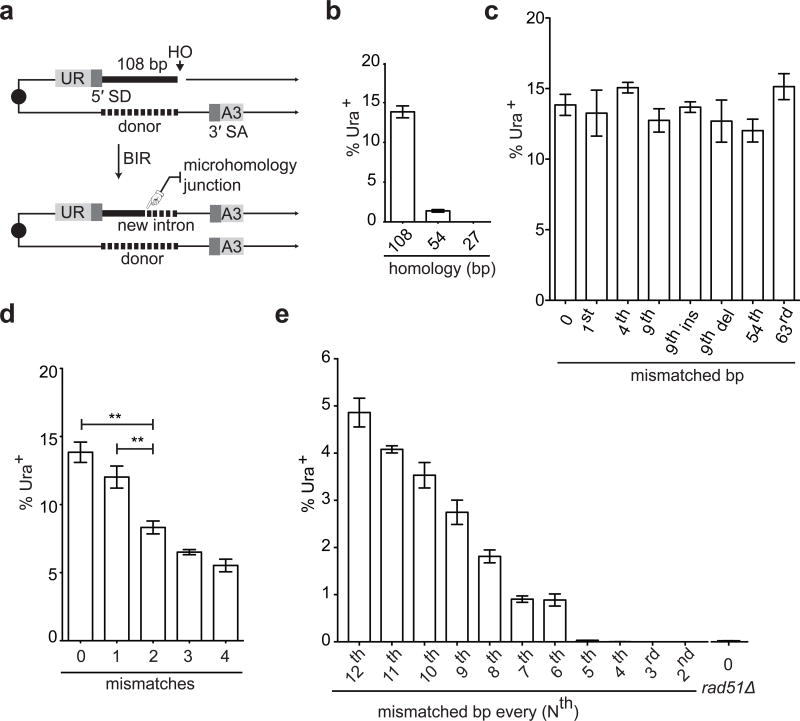

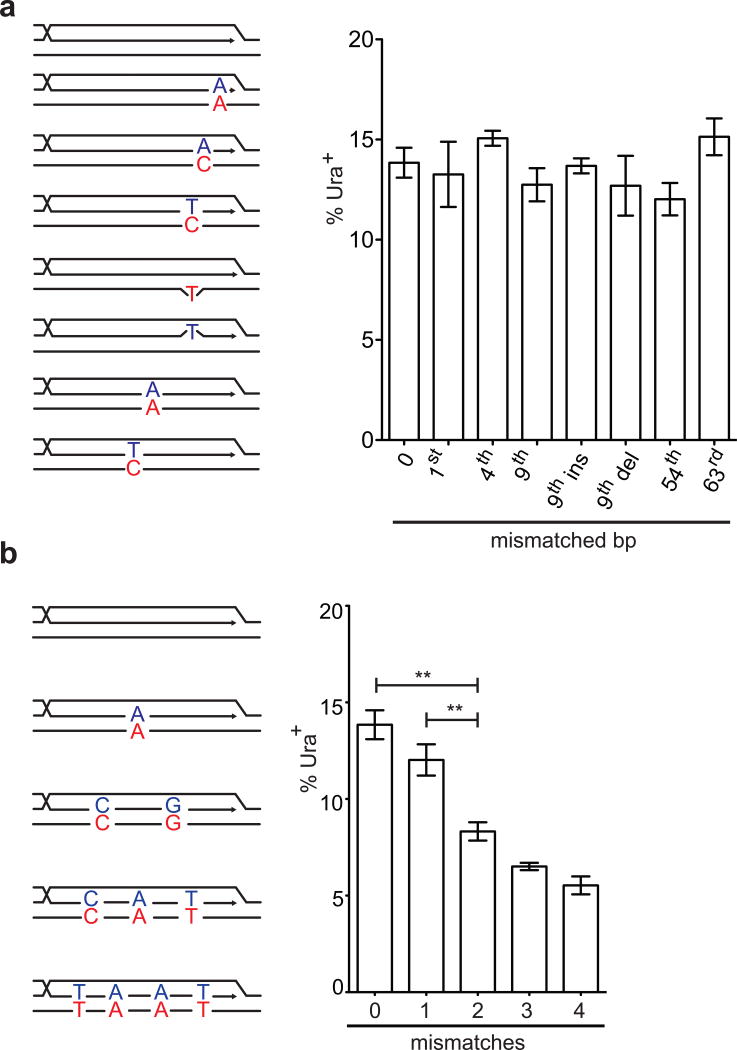

Fig. 1.

Stringency and sensitivity of Rad51-mediated recombination. a, A DSB is repaired by BIR using homologous or homeologous donor (108 bp). UR: first 400 bp of the URA3 ORF. SD: splice donor. SA: splice acceptor. A3: the remaining 404 bp of the URA3 ORF. b, 108, 54 and 27 bp donors. c, Donors differing by a single bp. d, Donors containing 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 mismatches. e, Donors containing mismatches every 12th, 11th, etc. position. Error bars represent s.e.m. Asterisks indicate p < 0.01, student’s t test.

A DSB was created by the galactose-inducible, site-specific HO endonuclease in strains lacking natural HO recognition sites16. The 108-bp region of shared homology includes the 5′ end of an artificial intron, so that when BIR is completed, a functional intron is formed and yeast become Ura3+ (Fig. 1a).

In the absence of mismatches, the viability of Ura3+ cells completing BIR was 14%. (Fig. 1b). When shared homology was reduced from 108 bp to 54 or 27 bp, the frequency of Ura3+ fell to 1% and 0.002%, respectively. Nonhomologous end-joining events, which do not become Ura3+, occurred ~0.8 % and were not considered.

BIR was not sensitive to donors with a single mismatch at different positions relative to the 3′ end of the invading strand (Fig. 1c and Extended Data Fig.1a). A donor containing either a single bp insertion or deletion also did not reduce BIR (Fig. 1c). When donors contained 2, 3 or 4 evenly spaced mismatches, BIR frequencies decreased progressively to 45% of the no-mismatch control (Fig. 1d and Extended Data Fig.1b). BIR was successful when donor sequences contained mismatches at every 12th, 11th, etc. position, down to every 6th bp (~6%) (Fig. 1e). Donors carrying mismatches every 5th bp were as defective as a rad51Δ strain without mismatches (Fig. 1e); however, even these recombinants were Rad51-dependent (Extended Data Fig. 2). Thus recombination in vivo can occur when there is no possibility of 8 consecutive base pairs; indeed, 5 consecutive base pairs appears to be sufficient to assure a modest level of recombination when the strand exchange machinery can “step over” a mismatch and extend the heteroduplex. For successful recombination, heteroduplex DNA apparently must extend over most of the 108-bp length, because even 54 bp of perfect homology had a lower rate of recombination than the 108-bp segment with every 9th bp mismatched (compare Fig. 1b and e).

If we adopt the assumptions of the in vitro-modeled initial step7,17, involving 3 Rad51 monomers (9 possible base-pairs), our data imply that recombination can be successful in cases where the initial stable encounter in vivo can occur when 5 consecutive base pairs can be formed and when there is a single mismatch in the remaining base-pairing sites (Extended Data Fig. 3). That the basic unit of encounter could be a Rad51 dimer is supported by studies of the initiation of RecA filament formation on ssDNA18 and from some structural studies of Rad51 and its paralogs4,19. We note that these models only address the first encounter between the Rad51 filament and the donor – analogous to the in vitro tests for initial, stable strand-pairing6–8 - and do not address either barriers to extending the heteroduplex past other mismatches or cooperativity that could arise by extending the duplex. That the fit is reasonably good suggests that the initial, stable encounter is likely to be the efficiency-determining step.

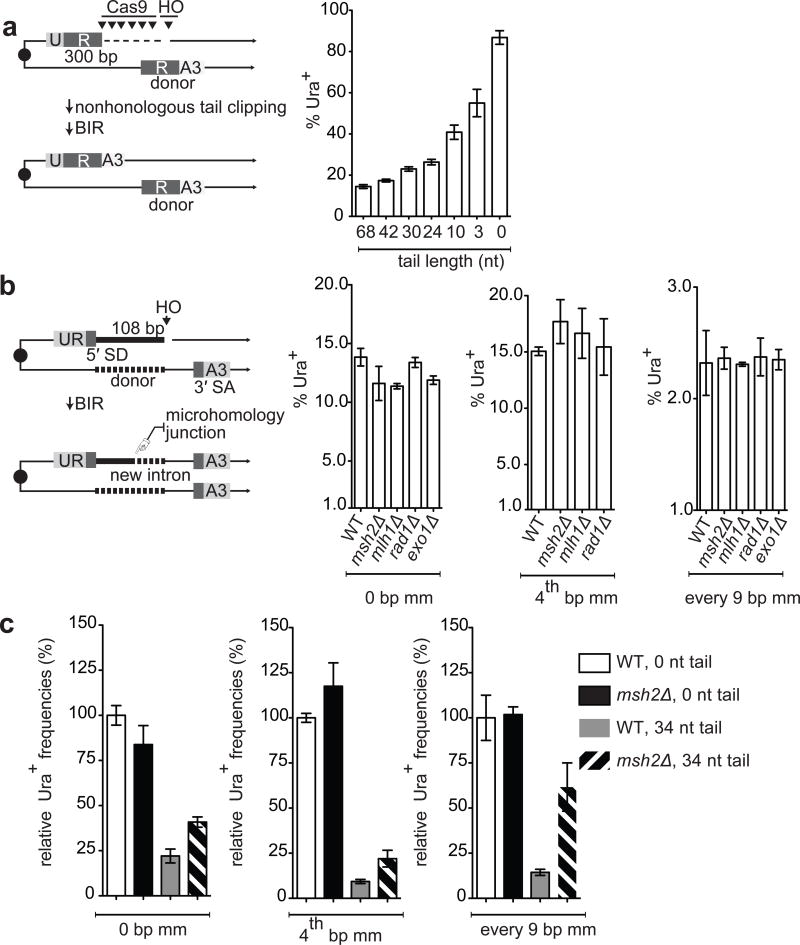

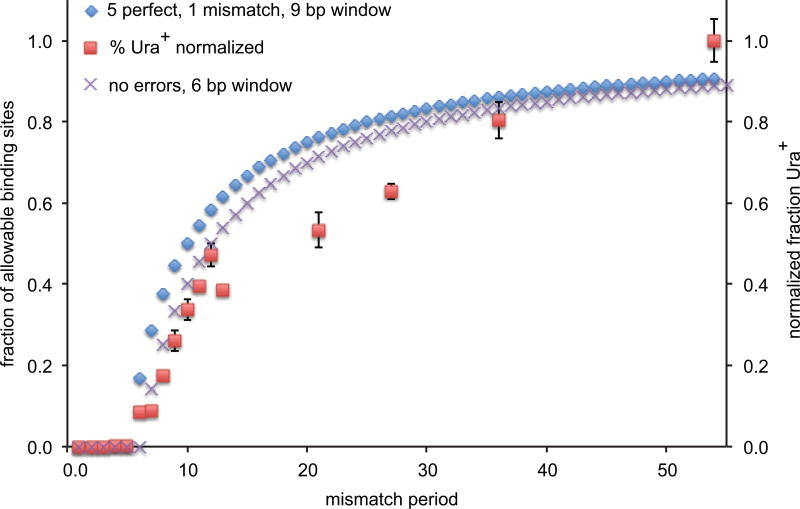

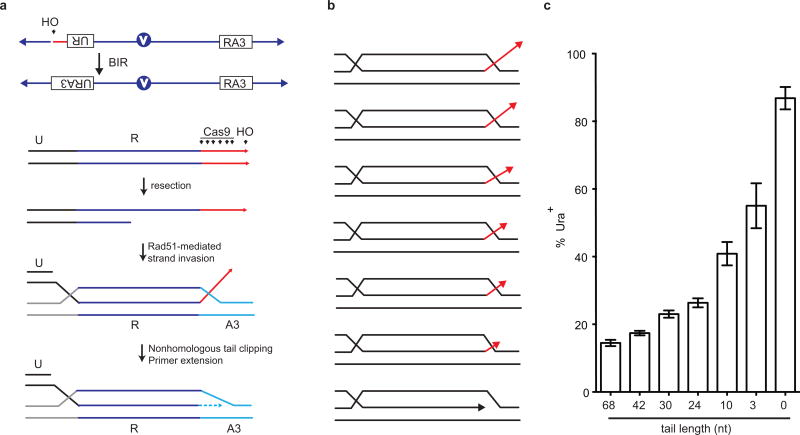

We discovered that the presence of a nonhomologous tail at the 3′ end of the DSB profoundly affects recombination. We studied a previously described BIR assay16, where recombination between ‘UR’ and ‘RA3’ sequences share 300 bp perfect homology (Fig 2a). HO-induction generates a 68-bp nonhomologous tail that must be excised before new DNA synthesis can proceed from the 3′ end. Shorter nonhomologous tails were generated by Cas9 endonuclease (Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5). Compared to the 68-bp tail, the absence of a tail improved BIR 6-fold. Even a 3-bp nonhomologous tail is a barrier to recombination (Fig. 2a).

Fig. 2.

Influence of nonhomologous tail on recombination. a, Efficiencies of BIR between ‘UR’ and ‘RA3’ in the presence of varying lengths of nonhomologous tail. UR and RA3 share 300 bp. HO endonuclease generates a 68 bp nonhomologous tail. Cas9 endonuclease generates 42, 30, 24, 10, 3 or 0 nt tails. b, Effect of deleting mismatch repair genes when there is no nonhomologous tail (108 bp donor). c, Effect of introducing a 34 bp nonhomologous tail with 108-bp donor (Fig. 2b) in the presence or absence of mismatches. Cas9 endonuclease was used to generate a 34 bp tail. Error bars represent s.e.m.

A nonhomologous tail also affects toleration of mismatches. In spontaneous recombination a single-bp mismatch decreased recombination efficiency by 4-fold20. However, in the BIR assay shown in Fig. 1, where HO cleavage does not produce a nonhomologous tail, a single mismatch had no effect, nor did deleting mismatch repair genes (Fig. 2b). However, when we used Cas9 endonuclease to cleave 34 bp away from the end of the 108-bp region, a single mismatch now caused a more than 2-fold reduction in BIR (Fig. 2c). Thus the presence of a nonhomologous 3′ tail promotes strong heteroduplex rejection. Moreover, deleting MSH2 improved recombination, even when there were no mismatches, as seen also in spontaneous recombination20. We conclude that a nonhomologous tail at the 3′ end during strand invasion 1) is a major impediment to recombination and 2) is a confounding variable when examining recombination between mismatched substrates.

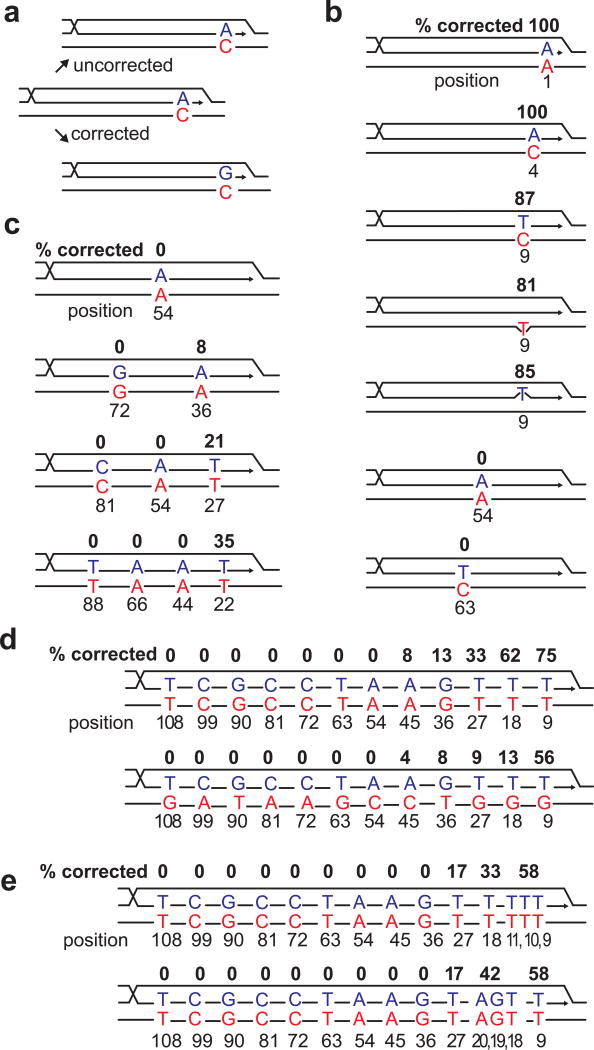

We next examined how mismatches were corrected in the strand invasion heteroduplex (Fig. 3a and Extended Data Fig. 6) by determining chimeric junction sequences of Ura3+ recombinants. With substrates containing a single mismatch, there is a clear gradient of correction, with mismatches close to the 3′ end almost always repaired in favor of the donor sequence (Fig. 3b). Donor sequences remained unchanged (data not shown). Correction at the 9th nt was >80% whether there was a single bp mismatch or a single nucleotide insertion or deletion. Mismatches at the 54th or the 63rd position were uncorrected, despite the fact that efficient recombination depends on homology extending >54 bp (Fig. 1b). The same gradient of correction was also seen for 2, 3 or 4 evenly-spaced mismatches (Fig. 3c). When every 9th bp was mismatched, including both transversion and transition mismatches or multiple adjacent mismatches (Fig. 3d–f), there is a clear polarity to mismatch correction, extending inwards about 50 nt. All mismatches 3′ to a given corrected mismatch are corrected. While mismatches close to the invading terminus could create a short 3′-ended flap and might attract the 3′ flap endonuclease Rad1/Rad10 to remove the non-homologous tail11,12, deleting Rad1 did not affect correction (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Table 1). Deleting mismatch repair genes also did not affect correction of a single base mismatch near the 3′ end (Extended Data Table 1).

Fig. 3.

Mismatch correction during BIR is dependent on the placement of the mismatch along the heteroduplex. a, Predicted sequence-changes in the recipient during BIR with or without correction. b, Correction of a single bp mismatch at different positions. c, Correction of 1, 2, 3 and 4 evenly-spaced mismatches. d, Correction of multiple, evenly-spaced mismatches. e, Correction of transversion (top) and transition (bottom) mismatches. f, Correction of clustered mismatches. Percent correction (%) and positional information of mismatches are indicated.

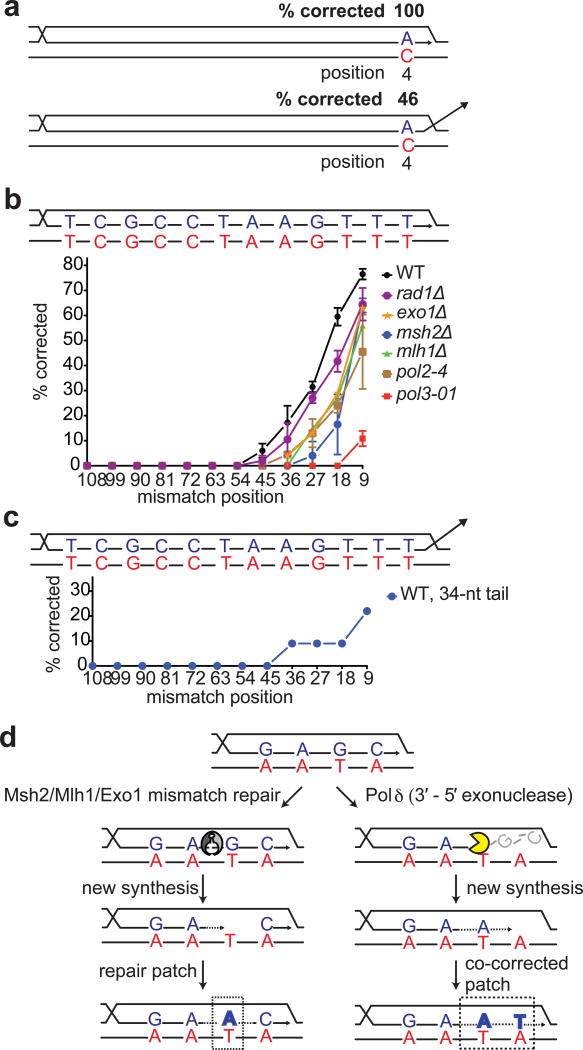

Fig. 4.

Mismatch-correction in the heteroduplex. a, Effect of nonhomologous tail on correcting a single mismatch. b, Effect of mutations on correction of multiple mismatches. c, Effect of nonhomologous tail compared to panel b. d, Model depicting correction in the heteroduplex. Left panel: Mlh1/Pms1-mediated correction may result in a repair patch (dashed box) whereas mismatches closer to the 3′ end are left unrepaired. No such instances were found. Right panel: DNA polymerase δ-mediated correction resulting in a co-corrected patch (dashed box). Predictions by each model are represented in bold letters.

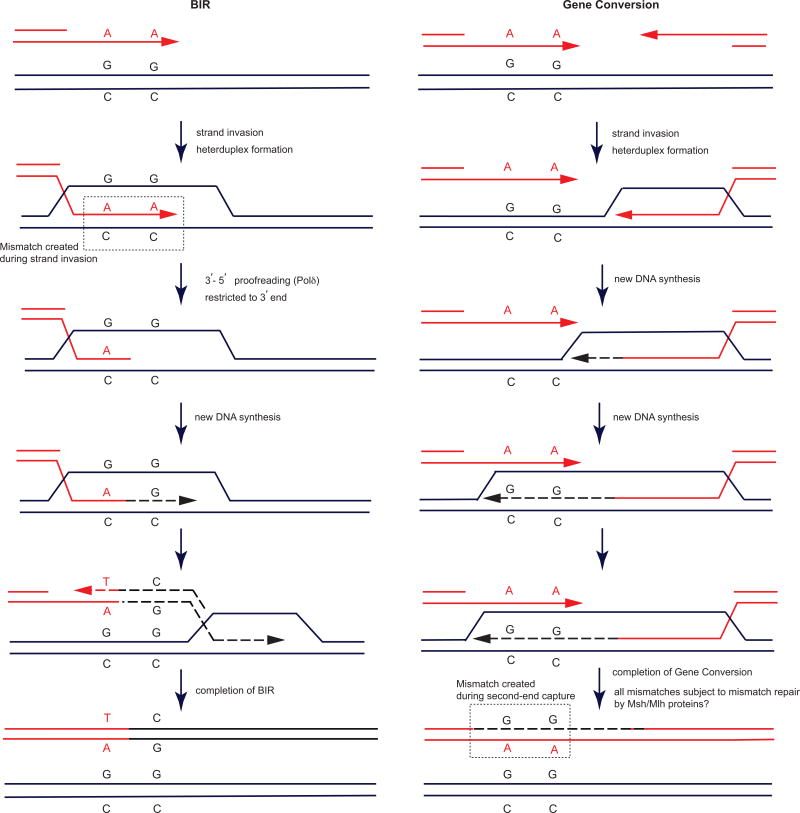

Nearly all correction was eliminated when the proofreading 3′-to-5′ exonuclease activity21 of DNA Polδ was ablated (pol3-01) (Fig. 4b and Extended Data Table 1), suggesting that proofreading activity is responsible for correcting mismatches as far as 45 nt from the 3′ end. In vitro studies have shown that 3′ to 5′ resection can degrade efficiently into a dsDNA region lacking any heterologies22. We conclude that proofreading activity of Polδ plays the major role of removing mismatches from the 3′ invading end during strand invasion (Fig. 4d). Proofreading-defective DNA Polε had only a minor effect. Correction can extend >45 nt from the 3′ end, however, removing mismatches beyond ~30 nt becomes dependent on Msh2, Mlh1 and the Exo1 exonuclease associated with mismatch repair (Fig. 4b). We previously reported that nonhomologous tails of ~20 nt could be removed by the 3′ to 5′ exonuclease activity of Polδ13; the results here suggest that such “backing up” can continue into heteroduplex DNA. Beyond about 40 nt, Msh2-Mlh1 appear to be required, possibly using Exo1 to excise these mismatches and then using Polδ to resynthesize the region or to stimulate further excision by Polδ. Although Msh2/Mlh1 could produce a patch of correction that would not necessarily include markers closest to the invading end (Fig. 4d, left panel), we found no such instances. It is unlikely that mismatches close to the 3′ end are simply unpaired and removed as a 3′ flap, because without Polδ proofreading, all the nucleotides of the invading strand can be incorporated into the DNA polymerase-extended BIR product.

Finally we note that the presence of a nonhomologous tail at the 3′ end of the invading strand alters mismatch correction. Whereas a single mismatch at the 4th base is essentially always corrected when there is no 3′ tail, its repair was reduced to about half by the presence of a 34-nt tail (Fig. 4a). In the presence of a nonhomologous tail, a similar inhibition of correction occurs when the substrates differ at every 9th position (Fig. 4c). Thus the presence of the tail not only promotes Msh2-dependent anti-recombination, it also impairs mismatch correction that is presumably still Pol3-dependent.

Our results differ from an analysis of gene conversion (GC) where mismatch correction was seen >200 nt from the DSB end23. We believe the difference reflects the more complex series of events that take place in gene conversion compared to the single strand invasion in BIR (Extended Data Fig. 7). In GC, sequences copied from the donor and then annealed to the resected second end can result in long tracts of heteroduplex DNA whose correction may be more dependent on the mismatch repair proteins. In our BIR system, we exclusively measure mismatch correction of heteroduplex DNA formed during the initial strand invasion (Extended Data Fig. 7).

A common thread tying topics such as origins of genetic diversity, evolution and cancer biology is the origin and transmission of mutations. DNA sequence changes may arise not only during replication but also during recombination24–26. We show that Polδ can influence inheritance of mutations during recombination between divergent sequences. Whereas proofreading suppresses an increase in spontaneous, replication- and repair-associated single base-pair mutations, it increases the transmission of such mutations in heteroduplex DNA during strand invasion. Mismatch correction by Polδ occurring within the heteroduplex of the recombining substrate prior to new DNA synthesis exhibits strong polar co-correction (Fig. 4d). Understanding the fate of mismatched sequences is also important in design of gene-targeting strategies, as one proposed pathway involves a BIR-like, one-ended strand invasion mechanism27,28, where Polδ-mediated corrections may play an important role in dictating targeting outcomes.

Extended Data

Extended Data Figure 1.

Sensitivity of BIR to mismatches. a, Donors differing by a single bp. b, Donors containing 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 mismatches. Experiments were independently repeated 3 times and averaged to arrive at experimental mean. Error bars represent s.e.m. Asterisks indicate p < 0.01, student’s t test. Blue and red letters represent the mismatches in the recipient and donor.

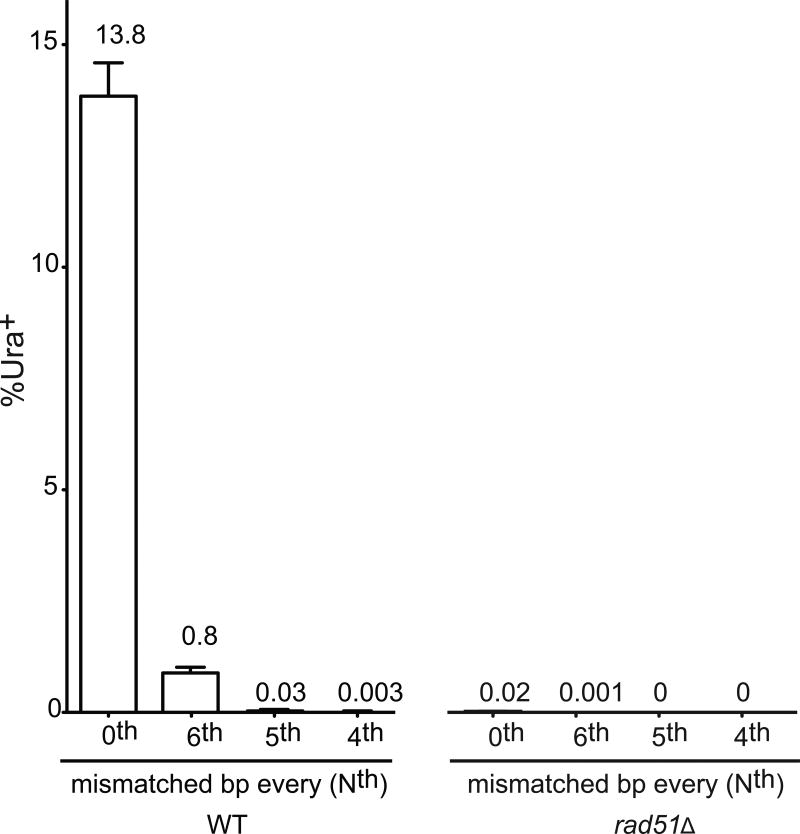

Extended Data Figure 2.

Sensitivity of BIR to mismatches. In the strains carrying mismatches at every 6th, 5th and 4th position, all of the residual recombinants were Rad51-dependent. BIR data for WT and rad51Δ are shown. Mean of each of the experiments are shown at the top of the respective histogram. Error bars represent s.e.m based on a minimum of 3 independent experiments.

Extended Data Figure 3.

Theoretical modeling of recombination in vivo. Fraction of possible alignments of Rad51 multimers that meet the criteria for an initial, stable strand invasion between ssDNA and homeologous donor sequences. Blue symbols show a model in which 3 Rad51 monomers can bind if the first 5 sites are perfectly base-paired and the remaining 4 sites can tolerate a single mismatch, plotted for each possible donor with donors having uniformly spaced mismatches with 1 to 54 bp spacings, compared to the measured data (red symbols) derived from Fig. 1. Purple Xs show the expected fraction of possible alignments based on a dimer of Rad51 that must complete all 6 consecutive base pairs.

Extended Data Figure 4.

Presence of a nonhomologous tail affects recombination. a, Schematic of the chromosomal construct. A DSB is induced by the galactose-inducible HO endonuclease adjacent to the UR segment, located at the CAN1 locus in a non-essential terminal region of chromosome 5 (Chr 5). This break can be repaired by a BIR mechanism using the donor sequences that share 300 bp of homology (R) located on the opposite arm of Chr 5 and situated about 30 kb proximal to the telomere. DSB induction by HO generates a 68-bp nonhomologous tail that is removed before primer extension by DNA polymerase. DSB induction by various Cas9 constructs generates 42, 30, 24, 10, 3 and 0 nt tails respectively. b, Invasion intermediates (D-loop) with or without a nonhomologous tail (red arrow). c, Influence of nonhomologous tail on BIR.

Extended Data Figure 5.

Nonhomologous tails generated by HO and Cas9 endonuclease. a, Schematic of the invasion intermediates (D-loop) with or without a nonhomologous tail (red arrow). b, To use pGAL1-Cas9, the HO cleavage site was first removed by selecting nonhomologous end-joining (NHEJ) survivors that had a ‘CA’ insertion at the HOcs after induction of pGAL1-HO endonuclease29. Such NHEJ survivors are immune to cutting by HO endonuclease. pGAL1-Cas9 constructs were then used to generate nonhomologous tails of various lengths. PAM sequences are in bold. c, For generating a 0-nt tail, a strain with CAACGG adjacent to the UR region was constructed that could be cut with Cas9. See Supplementary Table 1.

Extended Data Figure 6.

Mismatch correction of multiple, evenly-spaced mismatches. Donors differ at every 6th, 7th, 8th or 9th position. A minimum of 24 samples were sequence analyzed for each of the construct.

Extended Data Figure 7.

Series of events that take place in BIR vs. GC. a, In BIR, we exclusively measure mismatch correction of heteroduplex DNA (dashed box) formed during the initial strand invasion. b, In GC, sequences copied from the donor by extending the invading strand may extend well beyond half the length of the homology on the second end. Annealing between this extended end and the resected second end (second-end capture) would result in heteroduplex DNA (dashed box). For simplicity, only 2 mismatches are shown. Mismatch correction in GC studies therefore could be a combination of correction in the context of invasion and second-end capture.

Extended Data Table 1.

Mismatch correction of a single bp mismatch in various repair defective mutants. Mismatch correction in the heteroduplex is primarily dependent on DNA polymerase δ. For determining % correction, a minimum of 24 samples were sequence analyzed for each of the construct.

| strain | WT | msh2Δ | msh6Δ | mlh1Δ | rad1Δ | exo1Δ | pol2-4 | pol3-01 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % corrected | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 92 | 0 |

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Wolf-Dietrich Heyer, Tom Petes, Mara Prentiss, Scott Keeney and members of the Haber lab for their critical comments. We thank Valmik Vyas (Fink Lab, Whitehead Institute for Biomedical Research, Cambridge) for providing the S. cerevisiae codon optimized Cas9 plasmid and James E. DiCarlo (Church Lab, Harvard University) for providing hCas9 plasmid. We are grateful to the makers of the freely available DNA analyses software Serial Cloner 2.6.1 (Franck Perez, SerialBasics). R.A. is a former recipient of NRSA award (1F32GM096690). This work was supported by the NIH grants GM20056 and GM76020 to J.E.H.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest: None declared

Contributions: R.A., and J.H. conceived, designed and developed the genetic assays to measure BIR efficiencies. R.A. designed synthetic constructs (“G blocks”) with defined mismatches. R.A. designed and developed Cas9-based protocols. R.A and A.B. carried out experiments that measured BIR efficiencies. R.A. did the data analyses including, data compilation, statistical testing, and DNA sequence analyses of the break repair junctions. Theoretical modeling was done by K.L., and J.H. R.A., and J.H., wrote the paper.

Literature cited

- 1.Greene EC. DNA Sequence Alignment during Homologous Recombination. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:11572–11580. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R116.724807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Symington LS, Rothstein R, Lisby M. Mechanisms and regulation of mitotic recombination in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics. 2014;198:795–835. doi: 10.1534/genetics.114.166140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen Z, Yang H, Pavletich NP. Mechanism of homologous recombination from the RecA-ssDNA/dsDNA structures. Nature. 2008;453:489–484. doi: 10.1038/nature06971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conway AB, et al. Crystal structure of a Rad51 filament. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2004;11:791–796. doi: 10.1038/nsmb795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sung P. Catalysis of ATP-dependent homologous DNA pairing and strand exchange by yeast RAD51 protein. Science. 1994;265:1241–1243. doi: 10.1126/science.8066464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JY, et al. DNA RECOMBINATION. Base triplet stepping by the Rad51/RecA family of recombinases. Science. 2015;349:977–981. doi: 10.1126/science.aab2666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Danilowicz C, Yang D, Kelley C, Prevost C, Prentiss M. The poor homology stringency in the heteroduplex allows strand exchange to incorporate desirable mismatches without sacrificing recognition in vivo. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:6473–6485. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ragunathan K, Liu C, Ha T. RecA filament sliding on DNA facilitates homology search. Elife. 2012;1:e00067. doi: 10.7554/eLife.00067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Petukhova G, Stratton S, Sung P. Catalysis of homologous DNA pairing by yeast Rad51 and Rad54 proteins. Nature. 1998;393:91–94. doi: 10.1038/30037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Llorente B, Smith CE, Symington LS. Break-induced replication: what is it and what is it for? Cell Cycle. 2008;7:859–864. doi: 10.4161/cc.7.7.5613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fishman-Lobell J, Haber JE. Removal of nonhomologous DNA ends in double-strand break recombination: the role of the yeast ultraviolet repair gene RAD1. Science. 1992;258:480–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1411547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Colaiacovo MP, Paques F, Haber JE. Removal of one nonhomologous DNA end during gene conversion by a RAD1- and MSH2-independent pathway. Genetics. 1999;151:1409–1423. doi: 10.1093/genetics/151.4.1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paques F, Haber JE. Two pathways for removal of nonhomologous DNA ends during double-strand break repair in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1997;17:6765–6771. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.11.6765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Studamire B, Price G, Sugawara N, Haber JE, Alani E. Separation-of-function mutations in Saccharomyces cerevisiae MSH2 that confer mismatch repair defects but do not affect nonhomologous-tail removal during recombination. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:7558–7567. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.11.7558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hicks WM, Yamaguchi M, Haber JE. Inaugural Article: Real-time analysis of double-strand DNA break repair by homologous recombination. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:3108–3115. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1019660108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Anand RP, et al. Chromosome rearrangements via template switching between diverged repeated sequences. Genes Dev. 2014;28:2394–2406. doi: 10.1101/gad.250258.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Qi Z, et al. DNA sequence alignment by microhomology sampling during homologous recombination. Cell. 2015;160:856–869. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.01.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bell JC, Plank JL, Dombrowski CC, Kowalczykowski SC. Direct imaging of RecA nucleation and growth on single molecules of SSB-coated ssDNA. Nature. 2012;491:274–278. doi: 10.1038/nature11598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sasanuma H, et al. A new protein complex promoting the assembly of Rad51 filaments. Nat Commun. 2013;4:1676. doi: 10.1038/ncomms2678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Datta A, Hendrix M, Lipsitch M, Jinks-Robertson S. Dual roles for DNA sequence identity and the mismatch repair system in the regulation of mitotic crossing-over in yeast. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:9757–9762. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morrison A, Sugino A. The 3'-->5' exonucleases of both DNA polymerases delta and epsilon participate in correcting errors of DNA replication in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Gen Genet. 1994;242:289–296. doi: 10.1007/BF00280418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jin YH, Ayyagari R, Resnick MA, Gordenin DA, Burgers PM. Okazaki fragment maturation in yeast. II. Cooperation between the polymerase and 3'-5'-exonuclease activities of Pol delta in the creation of a ligatable nick. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:1626–1633. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209803200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mitchel K, Zhang H, Welz-Voegele C, Jinks-Robertson S. Molecular structures of crossover and noncrossover intermediates during gap repair in yeast: implications for recombination. Molecular cell. 2010;38:211–222. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deem A, et al. Break-induced replication is highly inaccurate. PLoS Biol. 2011;9:e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Strathern JN, Shafer BK, McGill CB. DNA synthesis errors associated with double-strand-break repair. Genetics. 1995;140:965–972. doi: 10.1093/genetics/140.3.965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hicks WM, Kim M, Haber JE. Increased mutagenesis and unique mutation signature associated with mitotic gene conversion. Science. 2010;329:82–85. doi: 10.1126/science.1191125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung WH, Zhu Z, Papusha A, Malkova A, Ira G. Defective resection at DNA double-strand breaks leads to de novo telomere formation and enhances gene targeting. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000948. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Langston LD, Symington LS. Gene targeting in yeast is initiated by two independent strand invasions. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:15392–15397. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0403748101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore JK, Haber JE. Cell cycle and genetic requirements of two pathways of nonhomologous end-joining repair of double-strand breaks in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2164–2173. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.