Abstract

Background and objectives

Little is known about patients exiting home hemodialysis. We sought to characterize the reasons, clinical characteristics, and pre-exit health care team interactions of patients on home hemodialysis who died or underwent modality conversion (negative disposition) compared with prevalent patients and those who were transplanted (positive disposition).

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted an audit of all consecutive patients incident to home hemodialysis from January of 2010 to December of 2014 as part of ongoing quality assurance. Records were reviewed for the 6 months before exit, and vital statistics were assessed up to 90 days postexit.

Results

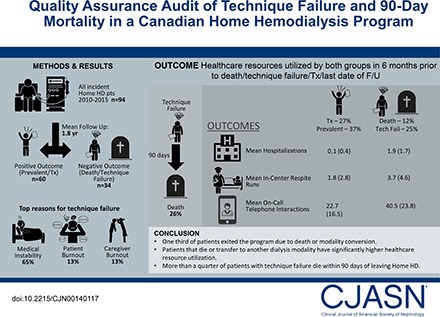

Ninety-four patients completed training; 25 (27%) received a transplant, 11 (12%) died, and 23 (25%) were transferred to in-center hemodialysis. Compared with the positive disposition group, patients in the negative disposition group had a longer mean dialysis vintage (3.15 [SD=4.98] versus 1.06 [SD=1.16] years; P=0.003) and were performing conventional versus a more intensive hemodialysis prescription (23 of 34 versus 23 of 60; P<0.01). In the 6 months before exit, the negative disposition group had significantly more in-center respite dialysis sessions, had more and longer hospitalizations, and required more on-call care team support in terms of phone calls and drop-in visits (each P<0.05). The most common reason for modality conversion was medical instability in 15 of 23 (65%) followed by caregiver or care partner burnout in three of 23 (13%) each. The 90-day mortality among patients undergoing modality conversion was 26%.

Conclusions

Over a 6-year period, approximately one third of patients exited the program due to death or modality conversion. Patients who die or transfer to another modality have significantly higher health care resource utilization (e.g., hospitalization, respite treatments, nursing time, etc.).

Keywords: mortality; intensive hemodialysis; modality conversion; transplantation; program exits; technique failure; technique survival; Home hemodialysis; training failure; therapy cessation; treatment discontinuation; Burnout, Professional; Canada; Caregivers; Hemodialysis, Home; hospitalization; Humans; Patient Care Team; Patient Discharge; Prevalence; renal dialysis; Vital Statistics

Introduction

There is ever increasing interest in home hemodialysis (HD), because intensive forms of home HD have been shown to normalize biochemical parameters, improve quality of life, and possibly afford a survival advantage over other forms of dialysis (1–6). Additionally, home HD in whatever form (a conventional dialysis prescription or a more intensive one) is less expensive than traditional thrice-weekly center-based treatments, making it an attractive option for health administrators and payers (7–9). Although dialysis programs dedicate valuable resources to selecting and training patients for home HD, less is known about patients exiting the program.

In our experience, program exits result from death, transplantation, patient choice, or modality change necessitated by medical instability, patient burnout, or care partner burnout. It is the subjective impression of our home HD unit nurses that patients who fail home HD and require transfer to in-center HD consume a disproportionate amount of nursing time in the months before discharge from the program. As such, we conducted an audit of our home HD unit admissions and discharges over a 6-year period to enumerate the number and type of program exits and measure the frequency of health care professional (HCP) interactions with patients on home HD in the 6 months before leaving the program. A secondary outcome was patient mortality 90 days after program exit for those alive at discharge. We hypothesized that patients exiting the home HD program due to death and modality change (i.e., negative disposition) would have more clinic visits, hospitalizations, telephone interactions, and respite HD treatments than prevalent patients or those exiting the program due to transplantation (i.e., positive disposition). Because there are no benchmarks or published guidelines for program exits, as a final step in this quality assurance audit, we sought to delineate minimum criteria for ongoing suitability for home HD and outline a strategy to support patients at home before a transfer to facility-based HD becomes necessary.

Materials and Methods

Our audit cohort consisted of all patients incident to home HD who were assessed, were deemed suitable, and commenced training between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014. Note that patients were incident to the home HD program, not necessarily to ESRD. All patients were followed until program exit or study end date of December 31, 2015. A detailed description of the home HD program and typical dialysis prescriptions is found in the online Supplemental Material. This study was approved by the research ethics board of the University of Alberta and the University of Alberta Hospital.

Sources of Data

Patient demographics, comorbidities, dialysis referral history, details of most recent HD prescriptions, and vascular access status were gathered from patient paper and electronic records of the Northern Alberta Renal Program (NARP). Additionally, our home HD unit clinical database captures every HCP contact with every patient or care partner for whatever reason. These interactions are documented as training notes, vascular access notes, nurse on call telephone call logs, unscheduled unit drop-in logs, and calls made by an HCP back to patients for any reason. Our unit also tracks routine clinic appointments and individual in-center respite dialysis treatments. Patient disposition after leaving the home HD program was determined by review of an NARP-wide electronic data system.

Data Collection

Baseline data were collected at the time of cohort entry. For patients who died, were transplanted, or left the home HD program for any other reason, health records were reviewed for the preceding 6 months from the date of program exit. All HCP interactions were enumerated. These included number and duration of hospitalizations, number of in-center respite HD treatments, number routinely scheduled and unscheduled of clinic visits, and number of telephone calls with the home HD unit for whatever reason. For patients who remained on home HD, these interactions were enumerated for the 6-month period before the study end date. We also undertook a retrospective review of the minutes of all clinical meetings in our home HD unit for the duration of the cohort to determine which patients the care team flagged as being at risk for technique failure.

Variable Definitions

Training failures were defined as discharges from the home HD training unit before completion of the entire home HD training course for anyone not able to learn or manually perform self-care. Program exits were defined as permanent discharges from home HD for patients who had completed home HD training and successfully self-dialyzed for any duration of time. These were subcategorized as exits from death, transplantation, recovery of kidney function, or modality conversion. Nurses retrospectively reviewed case notes and further identified reasons for modality conversion as medical instability, relocation, patient choice, or patient or care partner burnout. Where more than one reason existed, only the root cause was considered (i.e., if a patient relocated to be closer to supportive family due to deteriorating health, the underlying reason for modality conversion was classified as medical instability rather than relocation or patient choice). This classification was made by consensus of frontline home HD unit nurses and the nurse manager. Technique failures were exits from modality conversion due to medical instability or patient or care partner burnout. Negative disposition included program exits from both death or modality conversion, and positive disposition encompassed patients remaining on home HD at the time of study end date and those transplanted.

Statistical Analyses

Continuous variables were described as means with SDs, and categorical variables were described as absolute numbers and proportions. Comparisons between groups were made using chi-squared tests and ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis tests as appropriate (α=0.05). All outcomes (e.g., respite treatments, hospitalizations, clinic visits, or HCP interactions) in the 6 months before exit were normalized to 180 days to account for hospitalizations. Kaplan–Meier survival analysis was used to estimate 1- and 5-year technique survival. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA MP 13 (www.stat.com).

Results

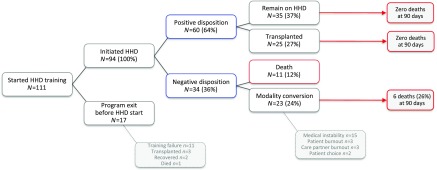

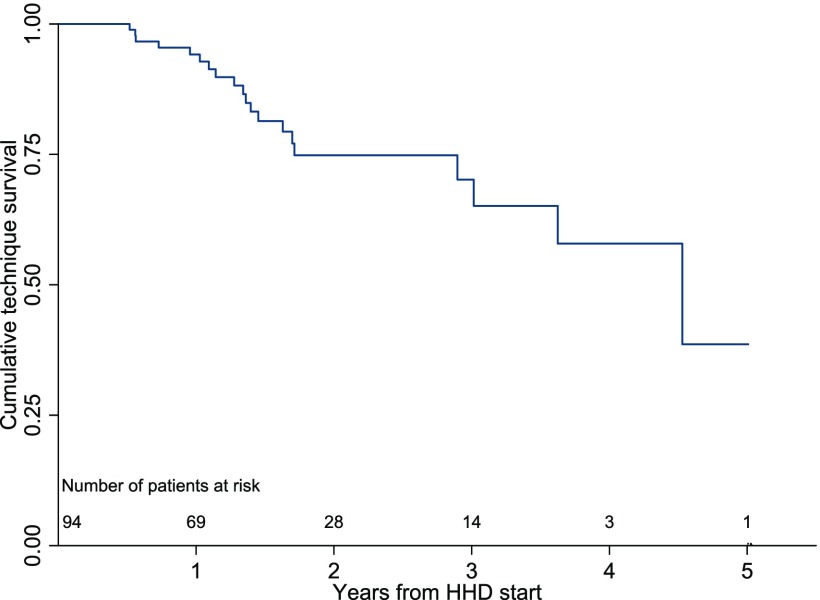

Between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014, our home HD program commenced training with 111 patients with ESRD, of whom 94 completed training and began self-administered HD in their homes (Figure 1). Of those leaving the program during the training period, 11 patients experienced training failure, two patients recovered kidney function, three were transplanted, and one person died. Of the patients who graduated to home dialysis, the mean follow-up was 1.8 years. Twenty-five of 94 (27%) were transplanted during the follow-up period, 11 of 94 (12%) died, 23 of 94 (25%) experienced modality conversion to in-center HD, and 35 of 94 (37%) remained active patients on home HD at study end date. The reasons for modality conversion were medical instability (15 of 23; 65%), patient burnout (three of 23; 13%), caregiver burnout (three of 23; 13%), and patient choice (two of 23; 9%). Collectively, technique failure made up approximately one fifth (21 of 94; 22%) of home HD program exits over 6 years. One- and 5-year technique survival rates were 94% and 38%, respectively (Figure 2).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of patient disposition for all individuals commencing home hemodialysis (HHD) training between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014.

Figure 2.

Kaplan–Meier curve for technique survival censored for death, transplantation, and program exit for patient choice for all individuals commencing home hemodialysis (HHD) training between January 1, 2011 and December 31, 2014. Outcomes included patient exits where the primary reason was medical instability, patient burnout, or care partner burnout; 1-, 2-, and 5-year technique survival rates were 94.2%, 74.8%, and 38.6%, respectively.

Baseline and exit characteristics are summarized in Tables 1 and 2, respectively. Comparing patients exiting home HD from death and modality conversion with those remaining prevalent or transplanted, the former had longer ESRD vintage (P=0.003), were less likely to be completely independent (P=0.05), and were more likely to have performed conventional dialysis at home at program exit (P<0.01).

Table 1.

Baseline cohort patient characteristics for all individuals commencing home hemodialysis training between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014

| Variable | All | Positive Dispositiona | Negative Dispositionb | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 94 | 60 | 34 | |

| Men, % | 67 | 40 (67) | 27 (79) | 0.19 |

| Race, % | 0.26 | |||

| White | 84 | 52 (87) | 32 (94) | |

| Other | 10 | 8 (13) | 2 (6) | |

| Mean age (SD), yr | 53.4 (13.2) | 51.8 (12.7) | 56.4 (13.8) | 0.10 |

| Mean ESRD vintage at cohort entry (SD), yr | 1.82 (3.3) | 1.06 (1.2) | 3.15 (5.0) | 0.003 |

| Urban residence | 75 | 50 (83) | 25 (74) | 0.26 |

| Primary renal disease, % | ||||

| GN | 25 | 19 (32) | 6 (18) | 0.14 |

| Diabetes | 28 | 15 (25) | 13 (38) | 0.18 |

| Hypertension | 7 | 5 (8) | 2 (6) | 0.66 |

| Cystic disease | 17 | 11 (18) | 6 (18) | 0.93 |

| Other | 17 | 10 (17) | 7 (21) | 0.64 |

| Smokers, % | 12 | 6 (10) | 6 (18) | 0.29 |

| Previous transplant, % | 5 | 8 (13) | 8 (24) | 0.21 |

| Pre-ESRD clinic attendance, % | 55 | 38 (63) | 17 (50) | 0.21 |

Positive disposition includes patient exits for transplantation and patients remaining on home hemodialysis at cohort end date.

Negative disposition is patient exits from death or modality conversion.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics at cohort exit for all individuals commencing home hemodialysis training between January 1, 2010 and December 31, 2014

| Variable | All | Positive Dispositiona | Negative Dispositionb | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | 94 | 60 | 34 | |

| Comorbidities at cohort exit, % | ||||

| Diabetes | 41 | 23 (38) | 18 (53) | 0.17 |

| Hypertension | 71 | 48 (80) | 23 (68) | 0.18 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 39 | 22 (37) | 17 (50) | 0.21 |

| Malignancy | 23 | 12 (20) | 11 (32) | 0.18 |

| Vascular access at cohort exit, % | 0.30 | |||

| AVF/AVG | 59 | 40 (67) | 14 (56) | |

| CVC | 35 | 20 (33) | 15 (44) | |

| Level of dependence at cohort exit, % | 0.11 | |||

| Independent | 59 | 42 (70) | 17 (50) | 0.05 |

| Dependent | 23 | 13 (22) | 10 (29) | 0.40 |

| Shared | 12 | 5 (8) | 7 (21) | 0.09 |

| Home HD prescription at cohort exit,c % | 0.02 | |||

| Conventional | 46 | 23 (38) | 23 (68) | <0.01 |

| Frequent conventional | 19 | 14 (23) | 5 (15) | 0.32 |

| Long | 29 | 23 (38) | 6 (18) | 0.04 |

AVF, arteriovenous fistula; AVG, arteriovenous graft; CVC, tunneled cuffed central venous catheter; HD, hemodialysis.

Positive disposition includes patient exits for transplantation and patients remaining on home HD at cohort end date.

Negative disposition is patient exits from death or modality conversion.

Conventional: three to four treatments per week, <5 hours. Frequent conventional: five to seven treatments per week, <5 hours. Long: three to seven treatments per week, >5 hours.

Significant differences in the number and type of HCP interactions were noted in the 6 months before exit or study end date among the two subgroups of patients (Table 3). Those with a negative disposition had significantly more and longer hospitalizations, a greater number of respite HD treatments, and more telephone calls than patients with a positive disposition. Of the 23 patients who underwent modality conversion to in-center HD after leaving home HD, 6 (26%) died within 90 days compared with no deaths among transplant recipients and patients who remained on home HD (P<0.001).

Table 3.

Outcomes of patients on home hemodialysis in the 6 months before program exit or study end date

| Variable | All | Positive Dispositiona | Negative Dispositionb | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean length of follow-up (median, IQR), yr | 1.8 (1.4, 1.0–2.4) | 1.8 (1.5, 1.0–2.4) | 1.7 (1.4, 0.9–2.1) | 0.78 |

| Mean no. of hospitalizations (SD)c | 0.8 (1.4) | 0.1 (0.4) | 1.9 (1.7) | <0.001 |

| Mean length of hospital stay (SD) | 7.4 (14.4) | 1.0 (3.2) | 18.6 (19.0) | <0.001 |

| Mean routine scheduled clinic visits (SD)c | 1.8 (0.8) | 1.7 (0.7) | 1.9 (1.1) | 0.28 |

| Mean respite treatments (SD)c | 2.5 (3.7) | 1.8 (2.8) | 3.7 (4.6) | 0.01 |

| Mean health care professional interactions (SD)c | 29.1 (21.2) | 22.7 (16.5) | 40.5 (23.8) | <0.001 |

IQR, interquartile range.

Positive disposition includes patient exits for transplantation and patients who remain on home hemodialysis at cohort end date.

Negative disposition is patient exits from death or modality conversion.

Normalized to 180 hospitalization-free days during the 6 months before program exit.

On reviewing clinical meeting notes from the study period, the multidisciplinary team flagged 22 patients as being vulnerable for home HD failure. Of these, 14 of 22 (64%) actually experienced failure or death, although the time from initial flagging to eventual program exit was highly variable (range from <1 to 17 months). Conversely, eight of 22 (36%) were flagged but did not experience an adverse outcome (modality conversion or death). This latter finding must be interpreted with caution, because flagged patients who remained on home HD at the study end date may still go on to experience technique failure or death after study end date. Three patients were flagged who eventually received a kidney transplant.

A small proportion of patients was transferred to center-based dialysis against their will (four of 23; 17%). In all patients, the underlying reason for transfer was a serious concern for safety. From the entire cohort, one patient was provided palliative end of life care while still on home HD.

Discussion

The result of our quality assurance review shows that, among patients incident to home HD who transferred to center-based dialysis, the majority did so because of medical instability preventing the safe conduct of home HD. Most other transfers occurred because of patient or care partner burnout. Our study also reveals that patients who exit due to death or conversion to conventional center-based HD have a longer dialysis vintage, are less likely to have performed labor-intensive dialysis prescriptions at the time of program exit (perhaps reflecting some degree of treatment fatigue), and consumed more health care resources before exit compared with patients who were transplanted or remained prevalent on home HD. Increased resource utilization comes in the form of hospitalizations, respite dialysis treatments, unscheduled clinic visits, and other health system interactions. Additionally, patients who experienced technique failure and transferred to in-center HD were more likely to have died within 90 days of leaving home HD than those patients with positive outcomes.

Although there is a small body of literature investigating factors that predict technique failure among patients on home HD, these cohorts are too small to reliably identify more than a handful of variables, the most common being age, diabetes, and central venous catheter use (10–13). Although these studies provide clues into potentially modifiable patient and program characteristics of home HD success or failure, they do not provide any insight into programmatic activity before patient exits, and they do not report on patient mortality after they leave the program. One-year technique survival is reported anywhere from 67% to 98% (10,11,14,15); technique survival in this study was 94%, which is typical of the Canadian experience reported previously (11,15). Our program audit builds on this literature by not only characterizing the reasons for exit but also, granular reporting on the patient and care team interaction in the 6 months before exit. Our observations have a number of important implications.

First, frail and/or failing patients in the home setting should be anticipated. Our results are themselves not surprising and likely reflect the natural history of patients on dialysis nearing the end of their lives or at least the end of their ability to self-manage dialysis. The fact that a large proportion of these patients will ultimately die while still performing home HD or shortly after converting to facility-based dialysis should not necessarily be interpreted as a sign of impending modality failure; rather, that more intensive follow-up and personalized care may be needed to facilitate successful management at home (including potential palliation).

Second, discharge from home HD is typically a process rather than a discrete event. This is supported by the observation that exits from modality conversion and death are preceded by increased hospitalizations, unscheduled clinic visits, respite treatments, and telephone calls with the home HD unit in the months before exit. This is not true for patients who exit home HD due to transplantation. This suggests a certain forewarning of an eventual adverse outcome that is underscored by the fact that over one quarter of patients who undergo modality conversion are deceased by 90 days.

Third, negative program exits are resource intensive. Although it was beyond the scope of this audit to cost the individual components of increased hospitalizations, unscheduled clinic visits, respite treatments, and telephone calls in the 6 months before exit, there is a realization that home HD units must be appropriately staffed to manage patients at all stages in the natural history of ESRD. Although some dialysis programs may espouse a programmatic philosophy that frail or failing patients are expeditiously transferred to facility-based HD, others take the view that such patients will require an escalation of nursing care that must be resourced accordingly within the home program.

We note that most discharges to facility-based dialysis result from joint decision making between the care team and the patient, with an understanding that a patient may no longer be safe to self-dialyze. However, in our experience, a small proportion of patients was transferred against their will. We recognize that there may be tension between patients’ wishes to perform home HD (either independently or with a care partner), despite a deteriorating ability to do so, and the unit’s obligation to provide safe care. Supporting such patients who understand and accept the risks of self-management to continue home HD places staff in an uncomfortable position of providing care where they perceive an unreasonable potential for unstable clinical demise in an unsupervised setting. Conversely, forcing a transfer to in-center dialysis is equally uncomfortable because of the perception of withholding treatment and forcing a modality change (often against a patient’s wishes). Thus, a secondary goal of our quality assurance audit was to use our experience to explicitly delineate minimum requirements to continue performing home HD and develop a menu of options to assist programs to maintain patients at home for as long as possible; these are outlined in Supplemental Material and Supplemental Tables 1–3.

A number of limitations of our study must be considered. First, as with all retrospective audits, our audit relies on the quality of record keeping. Fortunately, because of the links to resource allocation and employee compensation, our program must keep meticulous records regarding all patient interactions, even including all individual telephone calls made between patients and the home HD unit staff. Second, although we present the results of a 6-year program audit of patients on incident home HD, this is still a relatively short time for many patients to develop a negative disposition—especially those who only entered the audit cohort in the most recent years. This is particularly relevant for patients who are flagged by our nursing team as being subjectively at increased risk for technique failure. Many of these patients may have gone on to exit the program after the audit end date. Third, we describe a single-center experience and acknowledge that our case mix and practice patterns may not be representative of home HD everywhere (16). However, we believe that lessons derived from this program audit will be broadly applicable and of value to other home programs. Fourth, because the annual turnover of the home HD population is relatively modest, even in a large program such as ours, it will take years to prospectively evaluate the utility of the proposed minimum criteria to maintain patients at home and delineate which of these are most commonly at risk. Our program has implemented a monitoring process to assess the frequency with which we initiate the proposed measures to support patients at home to guide future resource allocation. Although prospective monitoring is a key element in a quality improvement initiative, our more immediate goal was to provide our home HD frontline staff with clear guidance about their responsibilities toward their failing patients and provide some reassurance that they have exhausted all possible avenues to support patients at home before beginning the process of transition to facility-based dialysis. Prospective monitoring, while initiated, will take years to complete.

We have presented the results of a comprehensive home HD program exit audit to build on our understanding of patient disposition, the drivers of these exits, and type of health system interaction in the 6 months before leaving home HD. These findings suggest that patient exits should be anticipated and are resource intensive. As part of this quality assurance exercise, we propose minimum criteria to maintain patients in the home setting and describe concrete strategies to assist in maintaining patients at home before planning a transition to facility-based dialysis.

Disclosures

None.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the dedicated staff of the Northern Alberta Renal Program Baldwin Family Home Hemodialysis Unit and the generous philanthropic support of the Baldwin Family. The home hemodialysis nurses include Normandy Bello, Joanne Budjak, Valerie Gerla, Kim Gordon, Elizabeth Hryciw, Francis Leda, Lisa Lillebuen, Nadine Mass, Shonna McCormack, Barbara Salter, Robyn Shelemay, and Harmony Wallace. The technicians include Andrew Bowling, Amandeep Brar, Nim Herian, Mark Jordan, Joe Reynolds, and Wes Rideout. Additional support staff include Francie Astorino, Ashu Dhanju, Melanie Fougere, Glenna McQueen, Karen Peddle, Sheri Thompson, and Laura White.

The salary of N.S is supported by the Division of Nephrology at the University of Alberta. K.S.-M. is supported as a Canadians Seeking Solutions and Innovations to Overcome Chronic Kidney Disease–Kidney Research Scientist Core Education and National Training Program New Investigator. The project reflects a quality assurance audit funded by the Division of Nephrology, Department of Medicine, University of Alberta.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Maintaining Patients on Home Hemodialysis: The Journey Matters as Does the Destination,” on pages 1209–1211.

This article contains supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.00140117/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pauly RP, Chan CT: Reversing the risk factor paradox: Is daily nocturnal hemodialysis the solution? Semin Dial 20: 539–543, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pauly RP, Gill JS, Rose CL, Asad RA, Chery A, Pierratos A, Chan CT: Survival among nocturnal home haemodialysis patients compared to kidney transplant recipients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 24: 2915–2919, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pauly RP: Survival comparison between intensive hemodialysis and transplantation in the context of the existing literature surrounding nocturnal and short-daily hemodialysis. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 44–47, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weinhandl ED, Gilbertson DT, Collins AJ: Mortality, hospitalization, and technique failure in daily home hemodialysis and matched peritoneal dialysis patients: A matched cohort study. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 98–110, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nadeau-Fredette A-C, Hawley CM, Pascoe EM, Chan CT, Clayton PA, Polkinghorne KR, Boudville N, Leblanc M, Johnson DW: An incident cohort study comparing survival on home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis (Australia and New Zealand dialysis and transplantation registry). Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 1397–1407, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walsh M, Culleton B, Tonelli M, Manns B: A systematic review of the effect of nocturnal hemodialysis on blood pressure, left ventricular hypertrophy, anemia, mineral metabolism, and health-related quality of life. Kidney Int 67: 1500–1508, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Klarenbach S, Tonelli M, Pauly R, Walsh M, Culleton B, So H, Hemmelgarn B, Manns B: Economic evaluation of frequent home nocturnal hemodialysis based on a randomized controlled trial. J Am Soc Nephrol 25: 587–594, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Komenda P, Gavaghan MB, Garfield SS, Poret AW, Sood MM: An economic assessment model for in-center, conventional home, and more frequent home hemodialysis. Kidney Int 81: 307–313, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mowatt G, Vale L, Perez J, Wyness L, Fraser C, MacLeod A, Daly C, Stearns SC: Systematic review of the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness, and economic evaluation, of home versus hospital or satellite unit haemodialysis for people with end-stage renal failure. Health Technol Assess 7: 1–174, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jayanti A, Nikam M, Ebah L, Dutton G, Morris J, Mitra S: Technique survival in home haemodialysis: A composite success rate and its risk predictors in a prospective longitudinal cohort from a tertiary renal network programme. Nephrol Dial Transplant 28: 2612–2620, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pauly RP, Maximova K, Coppens J, Asad RA, Pierratos A, Komenda P, Copland M, Nesrallah GE, Levin A, Chery A, Chan CT; CAN-SLEEP Collaborative Group : Patient and technique survival among a Canadian multicenter nocturnal home hemodialysis cohort. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 5: 1815–1820, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seshasai RK, Mitra N, Chaknos CM, Li J, Wirtalla C, Negoianu D, Glickman JD, Dember LM: Factors associated with discontinuation of home hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 629–637, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schachter ME, Tennankore KK, Chan CT: Determinants of training and technique failure in home hemodialysis. Hemodial Int 17: 421–426, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jaber BL, Schiller B, Burkart JM, Daoui R, Kraus MA, Lee Y, Miller BW, Teitelbaum I, Williams AW, Finkelstein FO; FREEDOM Study Group : Impact of short daily hemodialysis on restless legs symptoms and sleep disturbances. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 6: 1049–1056, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Komenda P, Copland M, Er L, Djurdjev O, Levin A: Outcomes of a provincial home haemodialysis programme--a two-year experience: Establishing benchmarks for programme evaluation. Nephrol Dial Transplant 23: 2647–2652, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pauly RP, Komenda P, Chan CT, Copland M, Gangji A, Hirsch D, Lindsay R, MacKinnon M, MacRae JM, McFarlane P, Nesrallah G, Pierratos A, Plaisance M, Reintjes F, Rioux J-P, Shik J, Steele A, Stryker R, Wu G, Zimmerman DL: Programmatic variation in home hemodialysis in Canada: results from a nationwide survey of practice patterns. Can J Kidney Health and Dis 1: 11, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.