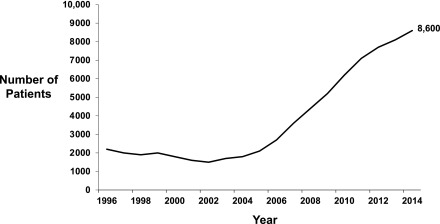

The past decade has seen a resurgence in the use of home dialysis in the United States (1). An increasing emphasis on home hemodialysis with the availability of simpler and more patient-friendly hemodialysis machines has contributed to this growth. Home hemodialysis allows for a flexible schedule, more frequent treatments, avoidance of long interdialytic interval, greater ability to travel, and an emphasis on self-management, which has been shown to improve patients’ independence and self-efficacy (2). Observational studies suggest a number of benefits associated with home hemodialysis compared with in-center hemodialysis, although direct comparisons across modalities may be problematic due to selection bias and confounding. Compared with its nadir in 2002, the number of patients treated with home hemodialysis in the United States has grown almost ninefold, and as of 2014, there were approximately 8600 patients treated with home hemodialysis in the United States (Figure 1) (1).

Figure 1.

Trend in prevalence of home hemodialysis in the United States 1996–2014. Data from the 2016 US Renal Data System Annual Data Report (Table D.1) (1).

As patient referrals and training for home hemodialysis continue to increase, understanding the outcomes of patients undergoing training and subsequently dialyzing independently at home is essential to maintaining patient safety and improving outcomes. Although much emphasis has been placed on predialysis education and patient choice before choosing a dialysis modality, surprisingly little information is available on process measures that allow for successful continuation of the selected home dialysis modality after the choice has been made. Home hemodialysis, in particular, lags behind in this area, and the clinical course of patients on home hemodialysis after they start dialyzing independently at home is not well described. The ideal study design to understand the life course of patients doing home hemodialysis would identify patients early in the course, perhaps at the time of home hemodialysis referral, and follow them longitudinally with serial assessment of health, functioning, quality of life, cardiovascular disease events, infection events, care partner burden, and other outcomes, including factors that allow patients to continue dialyzing independently at home. To our knowledge, such a prospective cohort study does not exist, and the best that we can do for now is piece together information from various sources to understand the course of patients after they have started home hemodialysis.

In this context, the two studies of Canadian patients on home hemodialysis reported in this issue of the Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (CJASN) provide important information. In the first study, Perl et al. (3) used data from the Canadian Organ Replacement Register to describe the temporal trends in home hemodialysis use and technique failure over a 17-year time period (1996–2012). There was a gradual increase in home hemodialysis uptake during this time period, with 33 patients per year starting home hemodialysis from 1996 to 2002 (n=233), 114 patients per year starting home hemodialysis from 2003 to 2007 (n=568), and 214 patients per year starting home hemodialysis from 2008 to 2012 (n=1068). With this sevenfold increase in the use of home hemodialysis, patients in the most recent period (2008–2012) were more likely to be older, new to dialysis, and treated with short daily hemodialysis compared with those in earlier time period (1996–2002). Perl et al. (3) defined home hemodialysis technique failure as receipt of an alternate dialysis modality for >60 days; whether this alternate modality was peritoneal dialysis or in-center hemodialysis was not reported. In the most recent period (2008–2012), the risk of technique failure was 51% higher overall and 2.5-fold higher during the first year of home hemodialysis compared with the period of 2003–2007. Most of this excess risk of technique failure occurred during the first 6 months of home hemodialysis initiation; the technique failure rates were 7% and 14% during the first 6 months of home hemodialysis during 2003–2007 and 2008–2012, respectively. Older individuals (≥65 years old) and those new to dialysis were each twofold more likely to experience technique failure compared with younger patients and those with prior dialysis history. Importantly, the risk of death in patients treated with home hemodialysis did not increase from the 2003–2007 period to the 2008–2012 period.

The second study in this issue of the CJASN by Shah et al. (4) complements this information by providing granular patient-level data on the causes and events preceding technique failure in patients commencing training from 2010 to 2014 in a single but large home hemodialysis program in Alberta. Using detailed medical record data, these investigators were able to define home hemodialysis technique failure as a switch to a different modality due to patient instability or patient or care partner burnout. Of the 94 patients who successfully completed home hemodialysis training, technique failure occurred in 22% of them; 16% (n=15) of the technique failures were due to medical instability, and 6% (n=6) were due to patient or care partner burnout. Data from the 6-month period before exit from the program provide valuable insight into the reasons that contributed to technique failure. Patients who died or converted to another dialysis modality had more frequent and prolonged hospitalizations, increasing numbers of respite dialysis treatments, and increasing numbers of health care professional interactions, compared with patients who remained on dialysis or underwent kidney transplantation. In hindsight, these data are not surprising, because declining health is likely to preclude continuing home dialysis. In fact, 64% of the patients who died or converted to another modality were previously flagged as “vulnerable for home hemodialysis failure” by the dialysis multidisciplinary team. On the basis of their experience and the results of the study by Shah et al. (4), the Alberta program has implemented a set of minimum criteria and interventions to support their patients’ ability to continue home hemodialysis.

To use the findings from these two studies to improve care of patients on home hemodialysis, we must answer two key questions. First, are the data from Canadian patients on home hemodialysis generalizable to other settings? As the authors pointed out, home hemodialysis in the United States is almost exclusively performed using the NxStage system. However, in our experience, the complexity of the dialysis machine is usually a deterrent to acceptance of home hemodialysis rather than a cause for technique failure. The medical instability identified as a factor preceding technique failure by Shah et al. (4) is likely generalizable to other health care settings. The experience of the home hemodialysis team managing these patients is also likely to be a key factor. The Alberta program seems to be a relatively large home hemodialysis program, with approximately two new patients per month undergoing training. Using the data from the Alberta program, assuming 15% program exits before completing training and 60% program exits due to other causes, a minimum of 10–12 new patients will need to be successfully trained every year to maintain a home hemodialysis clinic census of 15 patients. The trend in the United States has been toward proliferation of multiple small programs offering both home hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. In a recent report using data from a large dialysis organization in the United States, the average census across 323 clinics offering home hemodialysis was four patients per clinic and 1-year technique failure rate was 25% (5). Furthermore, certain thresholds may be needed for clinic staff to maintain confidence (as opposed to regulatory “competency”) in managing patients on home hemodialysis, and perhaps, the current trend in the United States of multiple small programs may be detrimental to the success of home hemodialysis.

Second, what programmatic changes need to be implemented to improve the experience of patients on home hemodialysis, and what should be the process to implement these changes? The paper by Shah et al. (4) documenting the Alberta experience and implementation of a prospective monitoring program highlights one such strategy. Dialysis care in the United States is highly regulated, and multidisciplinary teams are in place to coordinate patient care. However, dialysis care processes are often driven by regulatory requirements or factors directly linked to reimbursement, and implementing new “nonmandatory” programs at the unit level can be challenging. Nevertheless, as physicians and providers at the frontline of patient care, we must be the drivers of change and high quality care rather than passive implementers of regulations. Table 1 presents such a model of care on the basis of the Alberta program, designed to provide a dynamic assessment of patients’ skills and safety as well as interventions designed to potentially improve patient experience and allow patients to continue home hemodialysis.

Table 1.

Potential causes of home hemodialysis technique failure and management approaches

| Domains | Problems | Potential Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Patient/care partner burnout | Treatment frequency | Incremental hemodialysis |

| Treatment length | Nocturnal hemodialysis | |

| Care partner support | ||

| Respite hemodialysis | ||

| Major medical events | Major surgical procedures | Technique audit |

| Stroke, other cardiovascular | Retraining | |

| Bacteremia/other infections | Staff-assisted dialysis | |

| Hypotension | Home health aides | |

| Remote monitoring/telemedicine | ||

| Medication timing | ||

| Dialysis procedure related | Dialysis access | Staff assistance |

| Cannulation difficulties | Care partner training | |

| Change in access site/type | Retraining | |

| Dialysis equipment | Dialysate bags | |

| Change in water quality | Water filtration systems | |

| Plumbing issues | Financial support for plumbing | |

| Dialysis monitoring | Medication timing | |

| Use of new psychoactive medications, such as opioids | Care partner training |

The use of home hemodialysis is likely to continue growing, with an increasing emphasis on patient education in choosing dialysis modalities, incorporation of home hemodialysis training in renal fellowships, and emerging technologies that may make home hemodialysis less cumbersome. To allow patients to make informed choices and provide guidance to physicians with managing their patients, we must move the bar on the quality of evidence upward from its current state of expert opinion and retrospective studies to the gold standard of randomized clinical trials. A trial of implementing best practices for home hemodialysis, including some that are outlined here, and assessing the effect of these practices on meaningful patient-centered outcomes is one such strategy.

Disclosures

None.

Acknowledgments

T.S. is supported by grants R03-DK-104012 from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases and R01-HL-132372-01 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related articles, “Temporal Trends and Factors Associated with Home Hemodialysis Technique Survival in Canada,” and “Quality Assurance Audit of Technique Failure and 90-Day Mortality after Program Discharge in a Canadian Home Hemodialysis Program,” on pages 1248–1258 and 1259–1264, respectively.

References

- 1.US Renal Data System: 2016 USRDS Annual Data Report: Epidemiology of Kidney Disease in the United States, Bethesda, MD, National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young BA, Chan C, Blagg C, Lockridge R, Golper T, Finkelstein F, Shaffer R, Mehrotra R; ASN Dialysis Advisory Group: How to overcome barriers and establish a successful home HD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 2023–2032, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Perl J, Na Y, Tennankore KK, Chan CT: Temporal trends and factors associated with home hemodialysis technique survival in Canada. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1248–1258, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shah N, Reintjes F, Courtney M, Klarenbach S, Ye F, Schick-Makaroff K, Jindal K, Pauly RP: Quality assurance audit of technique failure and 90-day mortality after program discharge in a Canadian home hemodialysis program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1259–1264, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seshasai RK, Mitra N, Chaknos CM, Li J, Wirtalla C, Negoianu D, Glickman JD, Dember LM: Factors associated with discontinuation of home hemodialysis. Am J Kidney Dis 67: 629–637, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]