Abstract

Purpose

The goal of this study was to assess perspectives of racially/ethnically diverse, low-income pregnant women on how doula services (nonmedical maternal support) may influence the outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth.

Methods

We conducted four in-depth focus group discussions with low-income pregnant women. We used a selective coding scheme based on five themes (agency, personal security, connectedness, respect, and knowledge) identified in the Good Birth framework, and analyzed salient themes in the context of the Gelberg-Anderson behavioral model and the social determinants of birth outcomes.

Results

Participants identified the role doulas played in mitigating the effects of social determinants. The five themes of a Good Birth characterized the means through which nonmedical support from doulas influenced the pathways between social determinants of health and birth outcomes. By addressing health literacy and social support needs, pregnant women noted that doulas affect access to and quality of health care services.

Conclusions

Access to doula services for pregnant women who are at risk of poor birth outcomes may help disrupt the pervasive influence of social determinants as predisposing factors for health during pregnancy and childbirth.

Keywords: Birth, Cultural Diversity, Health Care Disparities, Social Determinants of Health, Underserved Populations

Introduction

Social determinants of health (SDOH), including economic stability, level of education, neighborhood and environment, and social relationships and interactions1, are predisposing factors that influence health outcomes.2–4 The impact of SDOH is heightened for vulnerable populations, and plays a crucial role in maternal and infant health outcomes.5

For example, women who have or develop conditions such as diabetes or hypertension during pregnancy are more likely to have a primary cesarean or preterm birth.6 Development of these and related conditions, including obesity, relates to structural and environmental factors that affect access to exercise and nutrition.6 Women who experience intimate partner violence and exposure to abuse are more likely to have little or no prenatal care, be hospitalized during pregnancy, and give birth to low birth weight infants.7,8 Unsafe neighborhoods and adverse environmental exposures increase the likelihood of preterm birth.9–11 Low health literacy among pregnant women is associated with low attendance of prenatal care visits and poor birth outcomes.12,13 Women with low socioeconomic status have greater chances of having a low birth weight infant or preterm birth.14 In addition, pregnant women with limited social support are more likely to have a low birth weight infant.15

The pathways between social determinants and birth outcomes have contributed to pervasive racial/ethnic disparities in maternal health and health care.16–18 Longstanding; complex sociodemographic and historical factors perpetuate the challenges women of color face in achieving positive birth outcomes.19–20 These disparities have persisted despite clinical and non-clinical approaches and interventions in the healthcare setting, and few solutions have been identified with the potential to effectively disrupt the pathway between SDOH and poor birth outcomes.16,21

Non-medical interventions are preferred options in addressing the SDOH.22 Doulas are trained professionals who provide continuous, one-on-one emotional and informational support during the perinatal period. Similar to community health workers, they are not medical professionals and do not provide medical services, but work alongside health care providers. Studies show that doula care is associated with lower epidural use and cesarean delivery rates, shorter labors, higher rates of spontaneous vaginal birth, and higher levels of satisfaction.23–27 Low-income women and women of color at the highest risk of poor birth outcomes are also the most likely groups to report wanting, but not having, access to doula services.26 The current evidence base is lacking in effective means of mitigating the effects of SDOH on birth outcomes for these high-risk populations. The goal of this study was to assess perspectives of racially/ethnically diverse, low-income pregnant women on how access to and support from a doula may influence the outcomes of pregnancy and childbirth.

Methods

Conceptual model

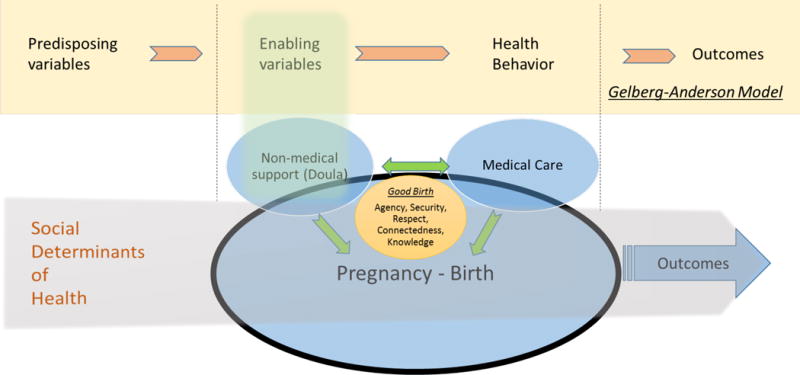

We used the Gelberg-Anderson model of health behavior and components of the Good Birth framework to create a conceptual model to describe the role of doulas – and of medical care - on the pathway between SDOH and birth outcomes.4,28 The SDOH are present before, during, and after pregnancy, but their effects on birth outcomes may be moderated by the quality of clinical care a woman receives and the nonmedical support she receives (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual Model

The Gelberg-Anderson model of health behavior focuses on vulnerable populations.4 The Predisposing, Enabling, and Need components of this model predict personal health practices, including the use of health services. The Predisposing domain includes “demographic characteristics” and “social structure patterned social arrangements in society that are both emergent from and determinant of the actions of the individuals.”4 Social structure includes a variety of components which create the context by which social determinants are manifested and maintained. Thus, our study considers the Social Determinants of Health1 a component of the Predisposing domain. The Predisposing variables impact Enabling variables (e.g. social support, health services resources, ability to negotiate the system), which subsequently impact Need. In our framework, the Enabling variables include doula services, which is directly associated with a pregnant woman’s perceived need for help. Gelberg and colleagues suggest that health behaviors and health outcomes will subsequently be impacted by Need.4 When placing this model within the context of childbirth in vulnerable populations, we also consider the elements of Agency, Personal Security, Connectedness, Respect and Knowledge that Dr. Anne Lyerly identified as characteristic of a Good Birth.28 These elements of a Good Birth can inform strategies to meet the physical and emotional needs of women during pregnancy and childbirth.28 Our model frames the context in which the trajectory of a woman’s pregnancy and the SDOHs may be influenced by the support of a doula, her clinical care, and potentially also by the interactions between the doula and her clinician.

Study participants

Thirteen racially/ethnically diverse, low-income pregnant women participated in four focus group discussions that were held at three locations in Minneapolis, MN in November and December of 2014. Multiple methods (flyers, emails and word of mouth) were used for recruitment. Inclusion criteria included pregnancy and fluency in English. The role of a doula was explained at the outset of the interview, and prior experience with a doula was not required, so as not to exclude potential participants who may not have been able to afford or access doula services.

Data and measurement

In collaboration with community-based partners, we developed and pilot tested a questionnaire to guide semi-structured focus group discussions (Appendix 1). These discussions were facilitated by two of the authors (RRH and CAV), both of whom are trained and experienced in qualitative data collection and analysis. Each focus group included between 2–6 participants. We had planned for three focus groups of 5–7 women; however, inclement weather precluded participation for several women in the first scheduled focus group, so we scheduled a fourth focus group meeting to allow their participation. Data saturation was achieved with four focus groups. All of the focus group discussions were recorded and transcribed using Automatic Sync Technologies. Manual notes taken by the facilitators (RRH, CAV) were used to augment the transcripts where comments were inaudible during the recording.

Questions focused on reasons for and barriers to doula support, and the ways doulas influence pregnancy and birth, based on prior research.24–27,29 We used the Good Birth framework’s themes (Agency, Personal Security, Respect, Knowledge, Connectedness)28 in a deductive approach to code the transcripts. We also created and used separate codes that highlighted 1) the mechanisms associated with doula support and healthy pregnancy, and 2) the relationship of these mechanisms with SDOHs.

Analysis

The initial coding was separately and independently validated using a co-analysis method among authors (CV, RRH, KBK).30 Coding was conducted in a shared Microsoft Excel document. After the first round of coding, we met to discuss differences among coders and to refine codes and definitions for clarity. Then, one of the authors (CAV) led a second round of coding, grouping each of the codes to identify which themes emerged as patterns across each focus group. We then followed the same two-step process to code the transcripts for specific mechanisms of doula support that were associated with birth outcomes.

All participants consented to participate using a human subjects protection process approved by the University of Minnesota IRB under Code Number: 1403S49085.

Results

The study participants represented a racial/ethnically diverse group of women as described in Table 1. Participants were nearly evenly split between nulliparous and parous, and three-quarters of participants had a doula supporting them during their current pregnancy. Nearly 40% of women who participated in the focus groups voluntarily disclosed that their pregnancy was complicated by a medical condition (such as hypertension, prior preterm birth, or gestational diabetes).

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics of Focus Group Participants

| Characteristics | N (%) |

|---|---|

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| African American | 5 (38.5) |

| African | 4 (30.7) |

| Native American | 2 (15.4) |

| Caucasian | 2 (15.4) |

| Parity | |

| First Pregnancy | 6 (46.2) |

| Multiple | 7 (53.8) |

| Doula with current pregnancy | |

| Yes | 10 (76.9) |

| No | 3 (23.1) |

| Voluntarily Disclosed High Risk Medical Status | |

| Yes | 5 (38.5) |

| No | 8 (61.5) |

Table 2 contains information on each the key themes, with illustrative quotes, as described below.

Table 2.

Exemplary quotations on key themes of the qualitative analysis

| 5 Themes from Good Birth framework | Definition of theme | Social Determinants of Health Categories: Traditional and Vulnerable Domains (Predisposing Factors) | Personal/Family/Community Resources (Enabling Factors) | Exemplary quotations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | How a woman makes choices and the ability she has to make choices and be in control. |

|

|

1. “I think it [having a doula] helps prepare you mentally; like it’s gotten me more in the mindset of, you know…the confidence throughout the pregnancy knowing that like I can do this…” 2. “And it’s [a doula is] someone that can help you with education, learn about yourself and the baby, but also ensure that what you want is heard.” 3. “my husband and I are taking childbirth classes but we still feel need for a doula. You can’t remember everything and having experienced person around is important. Especially if we want to avoid a c-section…” |

| Personal Security | How safe a woman feels in her environment and the people in her life. |

|

|

4. “…having people there who make me feel good and feel like I can do it, not making me feel anxious, or scared, or, you know, like, “Oh… it’s going to be really hard,” more like positive outlook on it, which I think a doula really has helped…You know, so just using her and the techniques to kind of cope with labor…” 5. “Cultural differences are a big deal too. If I have choices then I will want someone with my culture to make me feel comfortable and understand what we do.” 6. “… I talk to the doctor, I see the doctor and I’m calling the doula right after that. What does that mean? Like, I’m scared…And she’s like, “Oh, no don’t be…It’s very comforting to know that you have somebody has your back and explaining everything.” |

| Respect | How engaged a woman is in the decision-making process and the sense of dignity she has from the level of respect for herself and the way others treat her. |

|

|

7. “having someone that is not only knowledgeable, but can put things I guess in layman’s terms, but also in a way that you understand it and respects your culture…your wellbeing, your upbringing and things about you that you like to make sure that the baby is okay too.” 8. “Can help you make pregnancy plans if you don’t have someone. Your doula can make sure it is being followed. Like if you say you don’t want an epidural and she can make sure that the anesthesiologist doesn’t come to do that.” 9. “When you call the doctor then the doctor don’t have time. Doula takes time with you. When you are staying at home the doula helps with stress…” |

| Knowledge | How prepared a woman is for childbirth based on the information she receives and being informed about what is happening to her body and around her. |

|

|

10. “doula was coming on all my appointments with me and I was like, I don’t speak medical terminology, like what just happened? And she’d break it down and like, “It’s okay” “ 11. “I also had like a class, like we got together with other pregnant moms and had like, discussions and education and actually healthy food. So it was kind of cool because you’re seeing other moms, but then also having my doula talk about more than just what was going on with me, but talk about being a mom and changes and family and different things like that…So, in that sense, I think that doulas provide a lot of education. 12. “My reasons for wanting a doula because I don’t have nobody right now and if I go into labor. I didn’t pay attention to my breathing class. I don’t know the techniques or how to calm down.” 13. “…they [doulas] refer you to classes and the breast feeding classes, birthing classes, any class you can think of that has to do with pregnancy, they have a referral for it.” |

| Connectedness | How alone a woman feels versus having people in her life she can trust. |

|

|

14. “I definitely think doulas are helpful like with mental – especially with stress because even if you’re not alone, sometimes you may feel alone. You might not want to talk to anyone else except for the person that actually wants to talk about babies.” 15. “I’m really stressed out and worry about things a lot and doula is there to support you and help you through stressful moments. Doula won’t judge you or say anything bad about you – there to be supportive and tell you how it is – if this is going to happen and if this will hurt and what I’m supposed to feel when this happens. Communicates with you and helps you along the way…” 16. “it’s good to have a doula because the doctors will say this and your family may say this, but the doula is mindful of who you are.” 17. “I think it makes perfect sense. You want someone [a doula] who knows why you are doing things with the same culture. If they don’t understand your culture then you have to educate them.” |

Agency

“[having a doula] helps prepare you mentally; like it’s gotten me more in the mindset of…the confidence throughout the pregnancy knowing that I can do this…”

Agency is the capacity of an individual to act or to make his/her own choices (as opposed to being someone to whom things happen).28 Low income and racially/ethnically diverse women suffer a lack of Agency in their medical care.31,32 Our findings suggest that doulas play an important role in equipping low-income diverse pregnant women with Agency by either prompting expression of concerns or by facilitating interactions with the health care provider (Table 2, Quote 2). Having a doula plays an important role in a woman’s ability to make an informed decision while positively influencing her belief in herself (Table 2 Quote 1).

Personal Security

“… I talk to the doctor…and I’m calling the doula right after that…Like, I’m scared…And she’s like, oh, no don’t be…It’s very comforting to know that you have somebody has your back.”

Physical and emotional safety plays an important role in pregnancy and childbirth. Feeling secure, comfortable and calm is particularly crucial for women contending with complex social circumstances (e.g. unstable living situation, non-supportive partner). As reflected in the above quote, the respondent’s doula contributed to her personal security by addressing her health concerns after an encounter with her provider. This concept of Security extends to incorporation of culturally concordant beliefs about childbirth and personal safety (Table 2, Quote 5).

Respect

“…having someone that is not only knowledgeable, but can put things in layman’s terms, in a way that you understand it and respects your culture…your wellbeing, your upbringing and things about you …to make sure that the baby is okay too.”

Respect is critical to a patient-centered experience, and a physician’s respect of a patient’s autonomy is often cited as an important goal of the birthing process.28 Further, Respect is the basis of informed consent.28 Autonomy in decision-making is a marker of respect and was discussed among focus group participants as a key component (Table 2, Quote 8). This theme was echoed throughout the groups, and there was consensus that a doula’s presence, particularly during the childbirth process would facilitate greater autonomy and respect in decision-making.

Knowledge

“My reasons for wanting a doula. [It’s] because I don’t have nobody right now, and if I go into labor, …I don’t know the techniques or how to calm down.”

Our findings suggest that doulas play a critical role in imparting knowledge to their clients and empowering them to become knowledgeable about the physiologic process of pregnancy. Some women gain this knowledge from their healthcare providers, however many of the participants suggested that they often did not fully understand some of the things their provider shared with them. In these instances, they relied on their doula to help “translate” their clinical encounters. Additionally, having a doula present to share techniques and pass on wisdom and birth strategies is important (Table 2, Quote 12). Doulas also play an important role in connecting women with resources to gain new knowledge as they prepare for childbirth (Table 2, Quote 13; Table 2, Quote 11).

Connectedness

“…it’s good to have a doula because the doctors will say this and your family may say this, but the doula is mindful of who you are.”

Connectedness considers the level at which a woman feels connected to the resources that are available, her clinicians, her infant, and the support people in her life-including her doula. Participants observed that doulas play an important role in ensuring that women who lack social support do not feel isolated (Table 2, Quote 14). Women expressed that the connection with their doula would make a difference in their pregnancy and childbirth, sometimes even more so than a health care provider or family member (Table 2, Quote 16) Women found the connection with their doula to be important for the general support that the doula provides, beyond specific knowledge or guidance in the birth process (Table 2, Quote 15). Many of the participants described stressful life situations and emphasized the desire to connect with a person who shared their culture and background (Table 2, Quote 17).

Discussion

Participant responses revealed that non-medical support from a doula could play a role in helping women overcome barriers to achieving a healthy pregnancy and childbirth. Women’s responses aligned with two key categories of SDOH defined in Healthy People 20201: health and healthcare; and social and community context. While the skills they bring and the support they provide are nonmedical, doulas play a role in pregnant women’s ability to access health services and in the quality of care they receive by addressing their health literacy and social support needs and also through interaction with prenatal and intrapartum care providers. While clinicians provide direct patient care in the context of the health and health care social determinant of health category, study participants also identified doulas as facilitators of improved patient/provider interactions that influence the satisfaction of the birth experience and favorable birth outcomes.

Much of the current research on successful interventions to address SDOH at the time of childbirth come from the international context33 but programs addressing SDOH for maternal and child health are increasingly being adopted in the U.S., owing largely to the persistence of disparities despite medically-focused interventions. For example, a community-based project in California serves as a model for successfully addressing SDOH to reduce racial disparities and improve birth outcomes for African American women.34 This program shifted prenatal care and case management to include support groups that educate, inform, empower and connect women socially, culturally and financially.34 Our findings are consistent with the those that emerged from the California initiative. However, our findings extend the learnings gleaned from individual projects and programs to explore a concept (nonmedical support) that can be integrated within health care financing and delivery systems in order to affect system change and potentially create long-term, sustainable solutions to persistent disparities in birth outcomes.

Much prior research on doula care has been conducted among white, upper-middle class women and/or in a randomized controlled trial context.23,29 While emerging research24,26 shows that the known benefits of doula care may be even greater among vulnerable populations, those who could most benefit from doula care frequently have the least access to it.23 Future work should examine the perspectives of doulas and of clinicians to further inform the conceptual model developed here. Also, policy and clinical efforts to increase access to doula services should address cultural, financial, and geographic barriers to care identified by pregnant women.

Implications for policy

Access to culturally-concordant care and support during childbirth was noted as a potential benefit of doula services by the women in our study, but lack of diversity among the doula workforce was seen as a potential barrier. Difficulty in ensuring representativeness among doulas is likely exacerbated by the fact that doula services are rarely covered by health insurance, thus creating a barrier to entry to this profession that disproportionately affects low-income communities.29, 35 Recent research on doula care and cost savings, especially among low-income women, has ignited discussion regarding reimbursement of doula care by health insurance programs, including Medicaid programs.24,26,27 Two states (Oregon and Minnesota) currently allow Medicaid reimbursement for doula services. Minnesota passed legislation in May 2013 establishing Medicaid reimbursement for doulas, which became effective on federal approval, starting September 25, 2014.36 Implementation challenges have been substantial and include lack of awareness about doula services on the part of pregnant women, maternity care clinicians, hospitals and clinics, and the health insurance plans that provide coverage to Medicaid beneficiaries.37 This research provides a framework for understanding how doula care may influence the pathways between social determinants of health and birth outcome, which may inform future efforts to expand health insurance coverage of doula services and integrate non-medical support within healthcare delivery systems.

Implications for clinical practice

Means of addressing SDOH are not inherently present in current health care delivery models. In childbirth particularly there is a tendency toward a ‘technocratic’ approach that privileges medical care over nonmedical support.38 Pregnancy and childbirth are critical junctures in the lifecourse, when the impacts of social determinants are heightened. Increasingly, women giving birth in the US are doing so in isolation, with a lack of personal, social, and emotional support.39,40 Recent studies have highlighted the importance of trust within the patient/provider relationship, the challenges this presents for low-income women, and the resulting effects on overall quality and disparities in maternal and child health outcomes.41,42

Prior research has suggested the need for adequate clinical care as well as personal support at the individual level, during pregnancy.41 Doulas were seen in our study as providing social support to help improve communication between low-income, racially/ethnically diverse pregnant women and their health care providers, via an increase in women’s Agency and Knowledge during pregnancy. Women in our study indicated that doulas helped create an environment of trust. Our study reflected the sense of engagement and connectedness participants felt in the presence of doulas, and noted that this presence can enhance the clinical encounter via improving the process of informed consent and increasing patient satisfaction.23

Limitations

The sample used for this study included 13 women and was a convenience sample from one metropolitan area of the United States; thus broad generalizations cannot be made. This exploratory study helped generate a conceptual model that sets forth hypotheses for future work, but does not itself establish a causal pathway. The focus groups took place during the early phases of implementation of Medicaid coverage of doula services in Minnesota and do not reflect full implementation of that policy, which may influence access to doula care for vulnerable populations. These results indicate the need for further investigation of the role of non-medical support in addressing social determinants of health.

Conclusions

Improving access to doula services for pregnant women who are at risk of poor birth outcomes may enhance clinical efforts to overcome the pervasive influence of SDOH on pregnancy and childbirth. This study contributes to the growing body of evidence that doulas as a social support intervention that can influence the pathways between social determinants and birth outcomes by addressing some of the underlying issues that evade clinical approaches to persistent disparities.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge data entry support from Shruthi Kamisetty and input and feedback provided by Amanda Huber, CMN; Rita O’Reilly, CNM; Debby Prudhomme; and Mary Williams, LPN. This research would not have been possible without the collaboration of community partners, Everyday Miracles, Cultural Wellness Center and Missionaries of Charity all located in Minneapolis, MN

Funding Support: Research reported in this manuscript was supported a Community Health Collaborative Grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Katy B. Kozhimannil, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Carrie A. Vogelsang, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health

Rachel R. Hardeman, Division of Health Care Policy & Research, Mayo Clinic College of Medicine, Rochester.

Shailendra Prasad, Department of Family Medicine and Community Health, University of Minnesota Medical School.

References

- 1.Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; Accessed July 16, 2015. Retrieved from: http://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/social-determinants-health. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Babitsch B, Gohl D, von Lengerke T. Re-revisiting Andersen’s Behavioral Model of Health Services Use: a systematic review of studies from 1998–2011. GMS Psycho-Social-Medicine. 2012;9:Doc11. doi: 10.3205/psm000089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andersen RM. Revisiting the behavioral model and access to medical care: does it matter? Journal of health and social behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gelberg L, Andersen RM, Leake BD. The Behavioral Model for Vulnerable Populations: application to medical care use and outcomes for homeless people. Health services research. 2000;34(6):1273–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halfon L, Larson K, Lu M, Tullis E, Russ S. Lifecourse health development: past, present and future. Child Health Journal. 2014 Feb;18(2):344–65. doi: 10.1007/s10995-013-1346-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rosenberg TJ, Garbers S, Lipkind H, Chiasson MA. Maternal Obesity and Diabetes as Risk Factors for Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes: Differences Among 4 Racial/Ethnic Groups. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(9):1545–1551. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2005.065680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parker Barbara, Judith McFarlane, Karen Soeken. Abuse during pregnancy: effects on maternal complications and birth weight in adult and teenage women. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1994;84(3):323–328. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cokkinides VE, Coker AL, Sanderson M, Addy C, Bethea L. Physical violence during pregnancy: maternal complications and birth outcomes. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1999;93(5 Part 1):661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00486-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Farley TA, Mason K, Rice J, Habel JD, Scribner R, Cohen DA. The relationship between the neighbourhood environment and adverse birth outcomes. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology. 2006;20:188–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stillerman KP, Mattison DR, Guidice LC, Woodruff TJ. Environmental exposures and adverse pregnancy outcomes: a review of the science. Reproductive Sciences. 2008;15(7):631–650. doi: 10.1177/1933719108322436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kruger DJ, Munsell MA, French-Turner T. Using a life history framework to understand the relationship between neighborhood structural deterioration and adverse birth outcomes. Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. 2011;5(4):260. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bennett IM, Switzer J, Aguirre A, Evans K, Barg F. Breaking it down’: Patient-clinician communication and prenatal care among African women of low and higher literacy. Annals of Family Medicine. 2006;4(4):334–340. doi: 10.1370/afm.548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Endres LK, Sharp LK, Haney E, Dooley SL. Health literacy and pregnancy preparedness in pregestational diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(2):331–4. doi: 10.2337/diacare.27.2.331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhong-Cheng L, Wilkins R, Kramer MS. Effect of neighbourhood income and maternal education on birth outcomes: a population-based study. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 2006;174(10):1415–20. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.051096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feldman PJ, Dunkel-Schetter C, Sandman CA, Wadhwa PD. Maternal social support predicts birth weight and fetal growth in human pregnancy. Psychosomatic Medicine. 2000;62(5):715–25. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200009000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and ethnic disparities in birth outcomes: a life-course perspective. Maternal and child health journal. 2003;7(1):13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.ACOG. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Women’s Health. 2005 Oct; Committee Opinion #317. [Google Scholar]

- 18.ACOG. Health Disparities in Rural Women. 2014 Feb; Committee Opinion #586. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Giscombé CL, Lobel M. Explaining disproportionately high rates of adverse birth outcomes among African Americans: the impact of stress, racism, and related factors in pregnancy. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131(5):662–683. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.5.662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hogan VK, Shanahan ME, Rowley DL. In: Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes. Handler A, Kennelly J, Peacock N, editors. 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Livingood WC, Brady C, Pierce K, Atrash H, Hou T, Bryant T., III Impact of preconception health care: Evaluation of a social determinants focused intervention. Maternal and child health journal. 2010;14(3):382–391. doi: 10.1007/s10995-009-0471-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Braveman P, Egerter S, Williams DR. The social determinants of health: coming of age. Annual review of public health. 2011;32:381–98. doi: 10.1146/031210-101218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hodnett E, Gates S, Hofmeyr G, Sakala C. Continuous Support for Women During Childbirth (Review) Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Attanasio LB, Blauer-Peterson C, O’Brien M. Doula Care, Birth Outcomes, and Costs Among Medicaid Beneficiaries. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(4):e113–e121. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kozhimannil KB, Attanasio LB, Hardeman RR, O’Brien M. Doula Care Supports Near-Universal Breastfeeding Initiation among Diverse, Low-Income Women. J Midwifery Womens Health. 2013;58(4):378–382. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kozhimannil KB, Attanasio LB, Jou J, Joarnt LK, Johnson PJ, Gjerdingen DK. Potential benefits of increased access to doula support during childbirth. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(8):e340–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Vogelsang C, Blauer-Peterson C, Alarid-Escudero F, Howell EA. Policy options for improving value in childbirth: doula care during pregnancy and preterm birth. Under review. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lyerly AD. A good birth: finding the positive and profound in your childbirth experience. Penguin; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lantz PM, Low LK, Varkey S, Watson RL. Doulas as childbirth paraprofessionals: results from a national survey. Women’s Heal Issues. 2005;15(3):109–116. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Creswell JW, Maietta RC. Systematic procedures of inquiry and computer data analysis software for qualitative research. Handbook of Research Design and Social Measurement. 2001;6:143–184. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Malley AS, Sheppard VB, Schwartz M, Mandelblatt J. The role of trust in use of preventive services among low-income African-American women. Preventive medicine. 2004;38(6):777–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sword W. A socio-ecological approach to understanding barriers to prenatal care for women of low-income. J Adv Nurs. 1999;29(5):1170–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00986.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.United Nations Development Program. A Social Determinants Approach to Maternal Health Discussion Paper. 2011 Accessed August 10, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/Democratic%20Governance/Discussion%20Paper%20MaternalHealth.pdf.

- 34.WK Kellogg Foundation. California Black Infant Health Program. Accessed August 10, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.wkkf.org/what-we-do/featured-work/a-new-approach-to-maternal-and-child-health.

- 35.Morton CH, Bastille M. Medicaid Coverage for Doula Care: Re-Examining the Arguments through a Reproductive Justice Lens, Part One. Science & Sensibility. 2013 Accessed March 31, 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.scienceandsensibility.org/?p=6461.

- 36.Minnesota Statutes, section 256B.0625, subd.28b. Accessed June 29, 2015 Retrieved from: https://legiscan.com/MN/text/SF699/id/752534.

- 37.Kozhimannil KB, Vogelsang CA, Hardeman RR. Medicaid Coverage of Doula Services in Minnesota: Preliminary findings from the first year. Interim Report to the Minnesota Department of Human Services. 2015 Jul; [Google Scholar]

- 38.Davis-Floyd R. The technocratic, humanistic, and holistic paradigms of childbirth. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2001;75:S5–S23. doi: 10.1016/S0020-7292(01)00510-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Leavitt JW. The growth of medical authority: technology and morals in turn-of-the-century obstetrics. Medical anthropology quarterly. 1987;1(3):230–255. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leavitt JW. Women and health in America: historical readings. Univ of Wisconsin Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Aved BM, Irwin MM, Cummings LS, Findeisen N. Barriers to prenatal care for low-income women. Western Journal of Medicine. 1993;158(5):493–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sheppard VB, Zambrana RE, O’Malley AS. Providing health care to low-income women: a matter of trust. Family Practice. 2004;21:484–91. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]