Abstract

Background

One in nine US infants is born before 37 weeks gestation, incurring medical costs 10 times higher than full-term infants. One in three infants is born by cesarean; cesarean births cost twice as much as vaginal births. We compared rates of preterm and cesarean birth among Medicaid recipients with prenatal access to doula care (non-medical maternal support) with similar women regionally. We used data on this association to mathematically model the potential cost effectiveness of Medicaid coverage of doula services.

Methods

Data came from two sources: all Medicaid-funded, singleton births at hospitals in the West North Central and East North Central US (n=65,147) in the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample, and all Medicaid-funded singleton births (n=1,935) supported by a community-based doula organization in the Upper Midwest from 2010–2014. We analyzed routinely collected, de-identified administrative data. Multivariable regression analysis was used to estimate associations between doula care and outcomes. A probabilistic decision-analytic model was used for cost-effectiveness estimates.

Results

Women who received doula support had lower preterm and cesarean birth rates than Medicaid beneficiaries regionally (4.7% vs. 6.3%, and 20.4% vs. 34.2%). After adjustment for covariates, women with doula care had 22% lower odds of preterm birth (AOR=0.77, 95% CI[0.61–0.96]). Cost-effectiveness analyses indicate potential savings associated with doula support reimbursed at an average of $986, (ranging from $929 to $1,047 across states).

Conclusions

Based on associations between doula care and preterm and cesarean birth, coverage reimbursement for doula services would likely be cost saving or cost effective for state Medicaid programs.

Keywords: Medicaid, Preterm Birth, Cesarean Delivery, Doula

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, nearly one in nine U.S. newborns were preterm (before 37 weeks gestation), and one in three were born via cesarean delivery (1). Recent professional efforts highlight the need to reduce overall cesarean rates through more appropriate use of the procedure (2). Other professional efforts focus on preterm birth; thirty-five percent of all infant deaths in 2010 were from preterm-related causes, more than any other cause (3). In addition, both preterm birth and cesarean delivery are comparatively costly. Cesarean deliveries costs twice as much as vaginal deliveries, for both Medicaid and private payers (4). Preterm birth costs the U.S. health care system more than $26 billion annually (5). Infants born preterm incur medical costs ten times higher than full-term infants during the first year (5,6). This includes high costs of neonatal care and frequent hospitalizations in addition to ongoing medical care. Because nearly one-half of all U.S. births are publicly financed, preterm births are a sizable public cost burden (5). As the largest payer for maternity care, Medicaid programs, both fee-for-service and managed care, have a unique opportunity to address quality and cost of care through policies and incentives to increase consistent use of evidence-based childbirth practices (7).

One intervention being undertaken by a small but growing number of state Medicaid programs and managed care organizations is reimbursement for nonmedical assistance from a doula for pregnant beneficiaries (8–10). A doula is a trained professional who provides physical, emotional, and educational support to mothers before, during, and immediately following childbirth. Support from a doula during labor and delivery is associated with lower cesarean rates and fewer obstetric interventions, fewer complications, less pain medication, shorter labor hours, higher infant APGAR scores, and also shows potential for reducing racial-ethnic and socioeconomic disparities in breastfeeding initiation (11–15). In addition to support during labor and delivery, the scope of a doula’s work often includes prenatal psychosocial support, education, and health promotion. Typical doula services would include two to four prenatal visits, support during labor and childbirth, and one to two postpartum follow-up visits (16).

While many women may benefit from access to evidence-based, supportive interventions that confer positive health effects during pregnancy and childbirth, only 6% of women who gave birth in 2011–2012 reported having support from a doula (15). Women most likely to report that they wanted – but did not have – doula support were black (vs. white) women and uninsured (vs. privately-insured) women (15). These groups of women are also at increased risk of preterm birth (5). Studies have shown a direct relationship between maternal stress and negative birth outcomes, including a correlation between worries and fears about pregnancy and preterm birth (5,12,17). Evidence suggests that communication with and encouragement from a doula throughout the pregnancy may increase a mother’s self-efficacy regarding her own pregnancy (11–13).

Our objectives were to compare rates of preterm and cesarean birth among Medicaid recipients with prenatal access to doula care with preterm and cesarean birth rates for Medicaid beneficiaries regionally, and to use data on this association to mathematically model the potential cost effectiveness of Medicaid coverage of doula services.

METHODS

This is a retrospective, secondary data analysis using an observational study design to assess statistical associations between key variables and mathematically model cost-effectiveness. Retrospective, multivariable regression analysis was used to estimate associations between doula care and preterm and cesarean births. A probabilistic decision-analytic model was used for cost-effectiveness estimates.

Data and Study Population

The study population comprised two groups: Medicaid-funded singleton births regionally (N = 65,147), and Medicaid-funded births with doula care provided by a nonprofit doula organization in a large metropolitan city in the upper Midwest (N = 1,935). Women receiving doula services are referred to the organization through one of the state’s largest Medicaid managed care organizations. The managed care organization provides a list of all enrolled pregnant women to the doula organization, and a staff member of the doula organization attempts to contact each eligible woman via telephone to notify them of the availability of doula services. These services are covered by the managed care program as one of the options for childbirth education, although the doula services provided encompass more than just prenatal education and include continuous labor support, postpartum visits and breastfeeding education. During the study period, doulas provided support at the births of approximately 15–20% of all eligible Medicaid managed care enrollees. Reasons for choosing doula care over other childbirth education options most often included convenience, proximity, and the availability of culturally-relevant support. Women receiving doula services from this organization typically receive four prenatal visits, support during labor and delivery, and two postpartum visits from doulas who completed DONA training requirements (18).

The study used the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), an all-payer inpatient claims database designed to approximate a 20 percent sample of discharges from U.S. hospitals (19). Using the NIS variable that designates the US Census Division in which each hospital is located, we limited the study sample to births that occurred in hospitals in the East North Central and West North Central regions. These include the states of Minnesota, North Dakota, South Dakota, Iowa, Missouri, Nebraska and Kansas (West North Central) and Wisconsin, Michigan, Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio (East North Central)(20). We also obtained state data on preterm birth rates for all Medicaid-funded deliveries from HCUPNet (http://hcupnet.ahrq.gov/), which generates estimates using the Statewide Inpatient Databases, a census of inpatient claims for participating states.

Data on the 1,935 doula-supported births are from de-identified client information that is routinely collected by the community-based doula organization. Data were collected for singleton babies born between January 1, 2010, and January 31, 2014, who received at least one prenatal doula visit. All births were financed by Medicaid.

In addition, we had access to detailed records on each prenatal doula visit from mid-2011 through mid-2013 pertaining to 811 births. Among these 811 cases, the mean number of prenatal visits was 3.77 (standard deviation [SD] 1.62), and ranged from one to eight visits. Of these 811 women, 222 (27.4 percent) had a visit with a doula early in the pregnancy (prior to the third trimester), and for those with early doula encounters, the average number of visits prior to the third trimester was 2.09 (SD 1.50). There were no significant differences in health or demographics between the 811 women for whom we have detailed data and the full doula sample of 1,935 women.

Measurement

The primary outcomes of interest were preterm birth and cesarean delivery. Preterm birth was identified in doula program data as deliveries prior to 37 weeks, and cesarean delivery was coded from the delivery mode listed. Using NIS data, we identified preterm birth using International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision diagnosis codes (6442, 64420, 64421). We identified cesarean births using Diagnosis-Related Group codes 765 or 766, as well as International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision procedure codes (740, 741, 742, 744, 7491, or 7499). These identification criteria are consistent with prior research using maternal hospital discharge records (21,22).

Measured covariates included maternal age, race-ethnicity, and two major pregnancy-related complications: hypertension and diabetes. Maternal age and race-ethnicity are self-reported in doula program data. The data set distinguishes between African-American women and women of African descent. We present information for each of these groups and combined results for “black women” for comparability with national estimates. NIS includes race and ethnicity in one data element, but reporting practices for race-ethnicity in the NIS vary across participating states. If the state supplied race and ethnicity in separate data elements, then ethnicity takes precedence over race in the combined variable. Final analytic categories for this study included black, white, Hispanic, Asian, Native American, and other. Hypertension and diabetes measures include both pre-existing and gestational conditions and are identified by patient report for doula data and by Clinical Classification System code 183 (for hypertension) and 196 (for diabetes) in NIS data.

Analysis

We calculated means and 95 percent confidence intervals (CIs) for maternal characteristics and outcomes. Rate differences were evaluated using t-tests. We used multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the association between doula support and preterm birth, controlling for maternal age, race-ethnicity, diabetes, and hypertension. All women in this study met the income eligibility thresholds for Medicaid, ensuring some consistency in health care access and socioeconomic status. Doula care has previously been associated with reduced cesarean rates (2,8,11), and we modeled the association between doula support and cesarean delivery separately for full-term and preterm births.

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of doula services, we developed a decision-analytic model of the potential cost impacts of changes in preterm status and in delivery mode (cesarean vs. vaginal) that may be associated with doula support for Medicaid beneficiaries, facilitated through reimbursement for doula services. The decision tree we constructed for this analysis compared two different strategies of care for Medicaid beneficiaries: 1) usual care and benefits (i.e., standard of care), and 2) standard of care in addition to access to care from a trained doula via health insurance coverage for this service. The endpoints were cesarean and vaginal deliveries in both preterm and full-term births for both strategies. A diagram of the decision tree is shown in Supplemental Appendix 1. We used cost data from March of Dimes on private insurance payments in the first year of life following full-term or preterm birth (23). We conservatively estimated Medicaid payments for full-term or preterm birth at half those paid by private insurers, based on the March of Dimes data. We used published estimates of Medicaid costs for vaginal and cesarean births (4) as well as empirically derived preterm and cesarean birth rates (24). To test the sensitivity of the model’s results to specific parameters’ uncertainty, we conducted a probabilistic sensitivity analysis. This means that we simulated the full range of potential results 10,000 different times by varying all parameters simultaneously. The parameters and probability distributions are shown in Supplemental Appendix 2. We conducted an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis, looking at the lower rates of preterm deliveries among women with doula support, and one-way sensitivity analysis using linear regression metamodeling (25). We varied potential doula reimbursement values from $200 to $1,200.

Statistical analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 and decision-analytic models were developed in R program (www.r-project.org). This analysis used only de-identified data and was therefore granted exemption from review by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Minnesota (IRB# 1202E10162).

RESULTS

The mean maternal age was similar among Medicaid-funded births regionally (age 25.7) and doula-supported births (age 27.1). However, hypertension and diabetes rates were lower in the doula-supported births than the regional sample. There was a lower proportion (10.3 percent) of white women among the doula-supported births than among Medicaid-funded births regionally (48.1 percent). The doula-supported births had lower preterm births rates (4.7 percent) than Medicaid births regionally (6.3 percent) in uncontrolled comparisons (p<0.001).

Doula care was associated with 22 percent lower odds of preterm birth (Table 2; Adjusted Odds Ratio (AOR)=0.77, 95% Confidence Interval (CI)= [0.61–0.96]), compared with Medicaid births regionally, after controlling for maternal race-ethnicity, age, hypertension and diabetes. Consistent with prior studies, black women had higher odds of preterm birth than white women (AOR=1.38, 95% CI [1.29–1.49]). In addition, women with hypertension (AOR=1.83, 95% CI [1.66–2.01]) or diabetes (AOR=1.25, 95% CI [1.12–1.39]) had higher odds of preterm birth.

Table 2.

Adjusted odds of preterm birth for Medicaid-funded births

| Preterm Birth | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| AOR (95% CI) | |

|

|

|

| Doula support | 0.77 (0.61–0.96) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Asian | 0.72 (0.56–0.94) |

| Black | 1.38 (1.29–1.49) |

| Hispanic | 0.99 (0.89–1.10) |

| Caucasian | Reference |

| Age category | |

| ≤20 | 0.88 (0.80–0.97) |

| 21–25 | 1.00 (0.93–1.20) |

| 26–30 | Reference |

| 31–35 | 1.08 (0.97–1.20) |

| 36+ | 0.63 (0.54–0.73) |

| Clinical characteristics | |

| Hypertension | 1.83 (1.66–2.01) |

| Diabetes | 1.25 (1.12–1.39) |

Source: Authors own calculations using data from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (Regional Medicaid-Funded Deliveries) merged with 2010–2014 data from a community-based non-profit doula organization that serves Medicaid beneficiaries.

Notes: Cells show adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the association between doula support and preterm birth, controlling for maternal age, race-ethnicity, and clinical complications.

The adjusted odds of cesarean delivery for preterm and full term deliveries are presented in Table 3. Among preterm births, doula support was not associated with odds of cesarean delivery (AOR=1.63, 95% CI [0.99–2.64]); however doula support was associated with substantially lower odds of cesarean among full-term births (AOR=0.44, 95% CI [0.39–0.49]), consistent with prior research (2,8,11,15). Other covariates were associated with cesarean birth, as expected, for both preterm and full-term births, with higher rates of cesarean delivery among women over age 30 (especially those over age 35), compared with women ages 26–30, and among women with hypertension and diabetes, compared with women who did not have these conditions. Also, among full-term births, black women had higher odds of cesarean (AOR=1.12, 95% CI [1.07–1.16]), compared with white women, whereas Asian and Hispanic women had comparatively lower odds of cesarean (AOR=0.74, 95% CI [0.65–0.83], AOR=0.76, 95% CI [0.72–0.80], respectively).

Table 3.

Odds of Cesarean Delivery for Medicaid-Funded and Doula-Supported Singleton Births, Compared with Medicaid-Funded U.S. Regional Births, Controlling for Demographic and Clinical Factors, Stratified by Preterm or Full-Term Status

| Odds of Cesarean Delivery among Preterm Births | Odds of Cesarean Delivery among Full-Term Births | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| AOR (95% CI) | AOR (95% CI) | |

|

|

||

| Doula support | 1.63 (0.99–2.64) | 0.44 (0.39–0.49) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| Asian | 0.75 (0.42–1.34) | 0.74 (0.65–0.83) |

| Black | 0.91 (0.78–1.05) | 1.12 (1.07–1.16) |

| Hispanic | 0.96 (0.77–1.21) | 0.76 (0.72–0.80) |

| Caucasian | Reference | Reference |

| Age category | ||

| ≤20 | 0.58 (0.47–0.73) | 1.46 (1.38–1.53) |

| 21–25 | 1.01 (0.86–1.19) | 0.90 (0.86–0.94) |

| 26–30 | Reference | Reference |

| 31–35 | 1.35 (1.10–1.65) | 1.29 (1.22–1.37) |

| 36+ | 2.08 (1.53–2.81) | 4.67 (4.35–5.01) |

| Clinical characteristics | ||

| Hypertension | 2.63 (2.18–3.18) | 1.33 (1.25–1.42) |

| Diabetes | 1.83 (1.48–2.28) | 1.76 (1.65–1.88) |

Source: Authors own calculations using data from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (Regional Medicaid-Funded Deliveries) merged with 2010–2014 data from a community-based non-profit doula organization that serves Medicaid beneficiaries.

Notes: Cells show adjusted odds ratios (AOR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) from multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the association between doula support and cesarean delivery, stratified by preterm birth status and controlling for maternal age, race-ethnicity, and clinical complications.

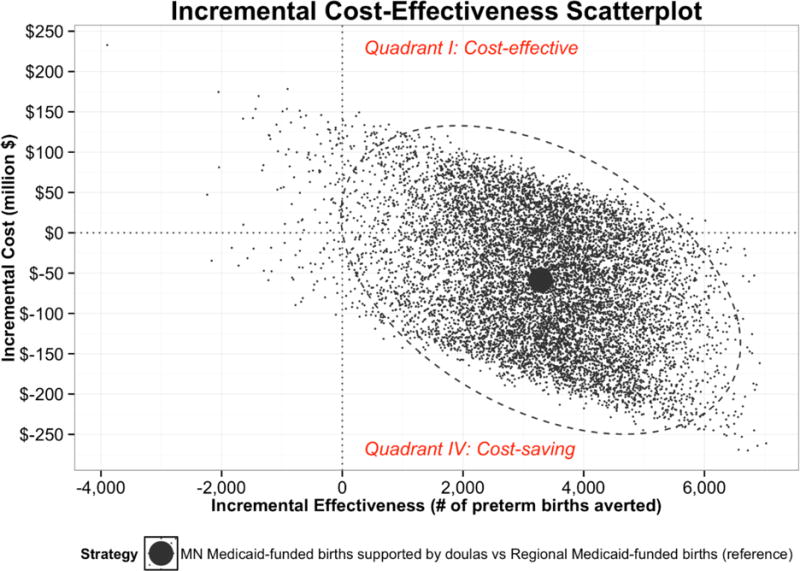

The incremental cost-effectiveness result is shown in Figure 1. The quadrants in Figure 1 plot costs and health outcomes (measured in terms of preterm births, where doula support is associated with a lower odds of preterm birth, as described in Table 2). Each dot represents one simulated scenario and the bigger dot represents the average incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of doula-supported deliveries. The lower right quadrant (quadrant IV) represents estimates that are “cost-saving,” that is, such scenarios improve health while saving money. Estimates in the upper right quadrant (quadrant I) are “cost-effective,” that is, such a scenario would improve health at a particular financial cost. We found that, on average, doula-supported deliveries among Medicaid beneficiaries regionally would save $58.4 million and avert 3,288 preterm births each year. Of the 10,000 simulated scenarios comparing Medicaid-funded deliveries with doula support to Medicaid-funded deliveries regionally, 73.3 percent resulted in cost savings (i.e., a greater effectiveness at a lower cost) and 25.3 percent were cost-effective (i.e., greater effectiveness at a higher cost).

Figure 1.

Incremental cost effectiveness analysis. Amount in $ represents break-even amount of reimbursement for doulas at which cost–savings equal 0.

We also calculated expected cost savings, using 10,000 simulated scenarios across a range of reimbursement rates. To estimate potential cost savings across these scenarios, we compared potential changes in Medicaid expenditures for childbirth based on the reimbursement rates for doulas and costs related to childbirth care (measured in terms of preterm and cesarean births, where doula support is associated with a lower odds of preterm birth, and lower odds of cesarean delivery among full-term births, per results presented in Tables 2 and 3). Supplemental Appendix 3 shows cost savings figures for all study states for which data are available, where the x-axis represents doula reimbursement rates, and the y-axis represents all childbirth-related costs. In each figure, the blue line represents the anticipated cost and health impacts across the rate range, and the place where the blue line intersects with 0 represents the “cost equivalency” point, where the costs of reimbursement for doulas are offset by savings related to lower rates of preterm and cesarean birth. This amount varies across states (which have different baseline preterm and cesarean rates, as well as different Medicaid reimbursement rates for care), but averages $986 and ranges from $929 to $1,047 across states.

DISCUSSION

This study presents the first cost-effectiveness data on doula care in a Medicaid context. Prior research suggested potential cost savings associated with reduced cesarean rates among Medicaid beneficiaries with access to doula care (8), but the current analysis improves on these estimates by 1) employing rigorous decision-analytic modeling, 2) using simulation and empirical assessment of model sensitivity to uncertainty in parameter estimates, and 3) accounting for associations with both preterm birth and cesarean delivery. Results from this analysis indicate that Medicaid coverage of doula services may be cost-effective – or even cost saving – for state programs.

Substantial clinical evidence supports the positive effects of doula care on a range of birth outcomes, with no known risks (11–15). However, prior research has not established whether there is an association between prenatal doula support and preterm birth. After adjusting for age, race, diabetes and hypertension, we found women with prenatal doula care had 22 percent lower odds of preterm birth, a substantial – but not unprecedented – effect size. Analyses of the CenteringPregnancy group prenatal care model show preterm risk reduction ranging from 33–47 percent among women randomized to group care, compared with those randomized to usual care (26,27). In addition, consistent with prior research (2,8,15), this analysis shows a relationship between doula support and reduced risk of cesarean delivery. Interestingly, the association between doula care and lower odds of cesarean delivery was only detected among women with full-term births, potentially reflecting consistency with a pattern uncovered in prior research, where doula support had a stronger effect on reducing cesarean among women without a medical indication for the procedure (15).

Risk of preterm birth varies by medical factors, socioeconomic conditions, race-ethnicity, substance abuse, and social factors such as high stress levels and lack of social support (5). Doula support during pregnancy may influence this constellation of risks for preterm birth by reducing stress, improving nutrition, improving health literacy, providing referrals and connections to resources, and improving emotional well-being (11–13,16). Prior randomized controlled trials of doula support during labor show stronger effects for women who are low income, socially disadvantaged, or who experience cultural or language barriers to accessing care (11). Extant research from both randomized trials (11) and observational studies (15) also finds that access to doula support, not a desire for doula support, is associated with improved outcomes, reduced rates of procedure use, and higher levels of satisfaction.

All women in this study with access to doula care had at least one prenatal visit with a doula, but without detailed information for the entire cohort on the number and timing of prenatal visits, we were not able to distinguish a dose-response relationship between prenatal doula visits and odds of preterm birth and cesarean delivery. Future research should examine this question in the context of expanded access to doula services. In addition, future research could also prospectively analyze doula care, possibly through a randomized controlled trial, to assess the causal pathway between prenatal doula support, preterm birth and cesarean delivery.

Results from cost models can help inform decisions around benefits design, case management, coverage policies, and value (28). There are limited published data (8,15) that have modeled the potential cost savings that could be achieved with doula support for pregnant Medicaid beneficiaries. Further, state Medicaid programs and managed care organizations have more accurate data—there is a need for potential benefit in either internal analyses or research using that data.

Strengths and Limitations

This study is the first rigorous cost-effectiveness analysis of doula care in the context of U.S. state Medicaid programs. It provides timely, policy-relevant information to inform ongoing efforts to expand access to doula services and improve maternity care outcomes. Yet, there are some important limitations on interpretation of these findings. The mathematical cost-effectiveness models presented here are based on associational, not causal, relationships between doula support and preterm and cesarean birth. Also, the doula data used in this study come from one organization in one state; however, relationships are consistent with studies using other data sets (11–13,15). In addition, information on preterm birth and maternal complications are from self-reports in doula data but hospital discharge reports in NIS data. Importantly, we did not have access to consistent information on the number of prenatal doula visits for all women with doula support in the study population, limiting our ability to assess a potential dose-response relationship. Other limitations include lack of information on prior preterm birth, educational attainment, marital status, prenatal care, and other risk markers; differences in racial-ethnic distribution between the study groups; and lack of data on whether Medicaid beneficiaries in NIS data may have received doula care. Cost data are estimated from previously published sources (4, 23) because we were unable to identify a source of accurate state-level data for childbirth-related hospitalizations.

In nonrandomized studies, like this one, there is a risk of selection bias and unmeasured confounding. That is, women who receive doula care may differ in important ways from women who do not. Our “comparison group” is a regional sample and not a population of women without access to doula care, but access to doula care, especially among lower-income women, is minimal based on survey responses from a national sample of childbearing women (29), so we assume that the vast majority of women in the regional comparison group did not have doula support. Future studies should compare women with and without access to doula care (intention to treat analysis) as well as between women who had doula care and those who may have been eligible but did not use these services (per protocol analysis).

Conclusions

In addition to providing support during labor, the scope of a doula’s work also includes prenatal psychosocial support, education, and health promotion. This type of care may be associated with lower risk of preterm birth, in addition to reductions in the chance of cesarean, and cost-effectiveness results indicate that achieving these health benefits may warrant investment in doula care as a covered benefit for Medicaid plans. Facilitating financial access to prenatal doula support should be given serious consideration by Medicaid programs and managed care organizations concerned with reducing overall rates of preterm birth and cesarean delivery and decreasing associated costs. This cost-effectiveness analysis clearly points to potential value in greater access to doula services among Medicaid beneficiaries.

Supplementary Material

Table 1.

Characteristics of regional Medicaid-funded births (2012), compared with Medicaid-funded births supported by doulas (2010–14)

| Medicaid-Funded Deliveries, West North Central and East North Central US (2012) | Medicaid-Funded Deliveries with Doula Support (2010–2014) | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| N=65,147 | N=1,935 | |||

|

|

||||

| Maternal characteristics | ||||

| Mothers age (mean) | 25.7 | 27.1 | 1.4 | <0.001 |

| Maternal hypertension rate (%) | 7.8 | 3.2 | −4.6 | <0.001 |

| Maternal diabetes rate (%) | 7.9 | 5.4 | −2.5 | <0.001 |

| Maternal race-ethnicity (%) | ||||

| Asian | 2.0 | 8.8 | 6.8 | <0.001 |

| Black | 22.9 | 47.2 | 24.3 | <0.001 |

| African American | NA | 10.0 | NA | |

| African descent | NA | 37.3 | NA | |

| Caucasian | 48.1 | 10.3 | −37.8 | <0.001 |

| Hispanic | 10.7 | 29.3 | 18.6 | <0.001 |

| Labor and delivery (%) | ||||

| Cesarean rate | 34.2 | 20.4 | −13.8 | <0.001 |

| Epidural rate | NA | 25.8 | NA | |

| Other pain medicine use rate | NA | 18.6 | NA | |

| Birth outcomes (%) | ||||

| Low birth weight rate | NA | 7.1 | NA | |

| Preterm birth rate | 6.3 | 4.7 | −1.6 | <0.001 |

Source: Authors own calculations using data from the 2012 Nationwide Inpatient Sample (Regional Medicaid-Funded Deliveries) and 2010–2014 data from a community-based non-profit doula organization that serves Medicaid beneficiaries.

Notes: P-values are from rate differences calculated using t-tests.

Acknowledgments

Funding acknowledgment: Research reported in this manuscript was supported by the Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health Grant (K12HD055887) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institutes of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD), the Office of Research on Women’s Health, and the National Institute on Aging, at the National Institutes of Health. This research was also supported by a Community Health Collaborative Grant from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences of the National Institutes of Health Award Number UL1TR000114. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Contributor Information

Katy B Kozhimannil, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Rachel R. Hardeman, Research Program on Equity and Inclusion in Healthcare, Division of Health Care Policy & Research (HCPR), Mayo Clinic, Rochester.

Fernando Alarid-Escudero, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Carrie Vogelsang, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Cori Blauer-Peterson, Division of Health Policy and Management, University of Minnesota School of Public Health.

Elizabeth A. Howell, Departments of Population Health Science & Policy and Obstetrics, Gynecology, and Reproductive Sciences, Center for Health Equity and Community Engaged Research, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- 1.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Osterman MJK, et al. National Vital Statistics Reports Births: Preliminary Data for 2013. National Vital Statistics Reports from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics National Vital Statistics System. 2014;63(2):1–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Caughey AB, Cahill AG, Guise JM, Rouse DJ, American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Safe prevention of the primary cesarean delivery. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 2014;210(3):179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.01.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Murphy SL, Jiaquan X, Kochanek DK. Deaths: Final Data for 2010. National Vital Statistics Reports. 2014;61(4):1–118. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Truven Health Analytics. The Cost of Having a Baby in the United States. 2013 Accessed on February 10, 2015. Available at http://transform.childbirthconnection.org/reports/cost/

- 5.Behrman R, Butler A. Preterm Birth : Causes, Consequences, and Prevention. Washington, DC: Institute of Medicine National Academies Press; 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markus AR, Andres E, West KD, et al. Medicaid Covered Births, 2008 through 2010, in the Context of the Implementation of Health Reform. Women’s Health Issues. 2013;23(5):e273–80. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Markus AR, Rosenbaum S. The Role of Medicaid in Promoting Access to High-Quality, High-Value Maternity Care. Women’s Health Issues. 2010;20(1):S67–78. doi: 10.1016/j.whi.2009.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kozhimannil KB, Hardeman RR, Attanasio LB, et al. Doula Care, Birth Outcomes, and Costs among Medicaid Beneficiaries. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(4):113–21. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oregon Health Authority Office of Equity and Inclusion. Oregon Legislature House Bill 3311- Doula Report. Accessed on February 10, 2015. Available at http://www.oregon.gov/oha/legactivity/2012/hb3311report-doulas.pdf.

- 10.Minnesota State Legislature. Minnesota State Legislature State Senate Bill 699. Minnesota Statutes 2012, Section 256B.0625 Doula Services section148.995, Subdivision 2. 2013 Accessed February 10, 2015. Available at: https://legiscan.com/MN/text/SF699/id/752534.

- 11.Hodnett E, Gates S, Hofmeyr G, et al. Continuous Support for Women during Chidlbirth. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2013;(7):CD003766. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gruber KJ, Cupito SH, Dobson CF. Impact of Doulas on Healthy Birth Outcomes. The Journal of Perinatal Education. 2013;22(1):49–58. doi: 10.1891/1058-1243.22.1.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vonderheid S, Kishi R, Norr K, et al. Reducing Racial/Ethnic Disparities in Reproductive and Perinatal Outcomes. New York: Springer Science and Business Media; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kozhimannil KB, Attanasio LB, Hardeman RR, et al. Doula Care Supports near-Universal Breastfeeding Initiation among Diverse, Low-Income Women. Journal of Midwifery and Women’s Health. 2013;58(4):378–82. doi: 10.1111/jmwh.12065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozhimannil KB, Attanasio LB, Jou J, et al. Potential Benefits of Increased Access to Doula Support during Childbirth. The American Journal of Managed Care. 2014;20(8):e340–52. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simkin P. New York, NY: 2012. Position Paper: The Birth Doula’s Contribution to Modern Maternity Care. Accessed February 10, 2015. Available at http://www.dona.org/PDF/BirthPosition Paper_rev0912.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lu MC, Halfon N. Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Birth Outcomes: A Life-Course Perspective. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2003;7(1):13–30. doi: 10.1023/a:1022537516969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DONA International. DONA International Certification. 2012 Accessed on February 10, 2015. Available at: http://www.dona.org/develop/certification.php.

- 19.Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), Health Care Cost and Utilization Project (HCUP) Overview. 2012 Accessed February 10, 2015. Available at http://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/nisoverview.jsp.

- 20.United States Census Bureau. Census Bureau Regions and Divisions with State FIPS Codes. Accessed October 29, 2015. Available at http://www2.census.gov/geo/pdfs/maps-data/maps/reference/us_regdiv.pdf.

- 21.Kuklina EV, Whiteman EK, Hillis SD, et al. An Enhanced Method for Identifying Obstetric Deliveries: Implications for Estimating Maternal Morbidity. Maternal and Child Health Journal. 2008;12(4):469–77. doi: 10.1007/s10995-007-0256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kozhimannil KB, Law MR, Virnig BA. Cesarean Delivery Rates Vary Tenfold among US Hospitals; Reducing Variation May Address Quality and Cost Issues. Health Affairs. 2013;32(3):527–35. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.March of Dimes. Premature Birth: The Financial Impact on Business. 2013 Accessed on February 10, 2015. Available at: http://www.marchofdimes.org/materials/premature-birth-the-financial-impact-on-business.pdf.

- 24.Grant RL. Converting an Odds Ratio to a Range of Plausible Relative Risks for Better Communication of Research Findings. BMJ (Clinical Research Ed) 2014;348:f7450. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f7450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jalal H, Dowd B, Sainfort F, et al. Linear Regression Metamodeling as a Tool to Summarize and Present Simulation Model Results. Medical Decision Making. 2013;33(7):880–90. doi: 10.1177/0272989X13492014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ickovics JR, Kershaw TS, Westdahl C, et al. Group Prenatal Care and Perinatal Outcomes: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2007;110(2 Pt 1):330–39. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000275284.24298.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Picklesimer AH, Billings D, Hale N, et al. The Effect of Centering Pregnancy Group Prenatal Care on Preterm Birth in a Low-Income Population. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012;206(5):415.el–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2012.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bundled Payments: A Glimpse into the Future? Hospital Case Management : The Monthly Update on Hospital-Based Care Planning and Critical Paths. 2014;22(10):135–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, et al. Listening to Mothers III: Pregnancy and Birth; Report of the Third National US Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences. New York, NY: Childbirth Connection; 2013. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.