Abstract

BACKGROUND

Transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has been associated with improved long-term dysphagia symptomatology as compared to chemoradiation. Dysphagia in the perioperative period has been inadequately characterized. The objective of this study is to characterize short-term swallowing outcomes after TORS for OPSCC.

METHODS

Patients undergoing TORS for OPSCC were prospectively enrolled. The Eating Assessment Tool 10 (EAT-10) was used as a measure of swallowing dysfunction (score > 2) and was administered on post-operative day (POD) 1, POD7, and POD30. Patient demographics, weight, pain level and clinical outcomes were recorded prospectively focused on time to oral diet, feeding tube placement and dysphagia-related readmissions.

RESULTS

51 patients were included with pathologic T-stages of T1 (24), T2 (20), T3 (3), Tx (4). Self-reported preoperative dysphagia was unusual (13.7%). The mean EAT-10 score on POD1 was lower than on POD7 (21.5 vs. 26.6, p=0.005) but decreased by POD30 (26.1 to 12.2, p<0.001). 47/51 (92.1%) were discharged on an oral diet but 57.4% required compensatory strategies or modification of liquid consistency. 98.0% of patients were taking an oral diet by POD30. There were no dysphagia-related readmissions.

CONCLUSIONS

This prospective study shows that most patients who undergo TORS experience dysphagia for at least the first month post-operatively but nearly all can be started on an oral diet. The dysphagia-associated complication profile is acceptable after TORS with a minority of patients requiring temporary feeding tube placement. Aggressive evaluation and management of postoperative dysphagia in TORS patients may help prevent dysphagia-associated readmissions.

INTRODUCTION

Since gaining FDA approval in 2009, transoral robotic surgery (TORS) for the resection of oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma (OPSCC) has increasingly gained use1. While concurrent chemoradiation for OPSCC is still considered the standard of care based on improved locoregional control as compared with radiation alone there is renewed interest in surgical management of OPSCC due to known long-term potential for severe late toxicity from chemoradiation2–4. A recent multi-institutional report suggests excellent (94.5%) 2-year disease-specific survival after TORS with risk-adjusted adjuvant therapy for OPSCC which compares favorably with survival after nonsurgical management5. While there are no prospective clinical trials comparing survival outcomes between the two treatment arms, meta-analyses of published data suggest equivalent survival between TORS and risk-adjusted adjuvant therapy and radiotherapy6,7. Because of this apparent equipoise, clinical trials currently underway are focused on ability of TORS to allow for de-intensification of adjuvant radiation (ECOG 3311) or on comparison of long-term functional outcomes between surgical and non-surgical treatment strategies (ORATOR) among several others8,9.

Given that the incidence of HPV-associated OPSCC has increased and that these patients tend to be younger and healthier and can expect to have good prognosis for long-term survival, functional outcomes are increasingly important10. While intermediate- and long-term dysphagia after TORS has been previously reported by several groups including ours, there are no publications which systematically describe short-term dysphagia after TORS for OPSCC11–20. Immediate post-operative dysphagia outcomes are rarely reported and, when reported, are only present at one data-point16,17,19. In a review of our departmental TORS database in 2014 we found that dysphagia-related readmissions occurred in 6.3% of cases which is similar to reported rates of dysphagia-related readmissions after TORS for OPSCC reported in the literature which ranges from 4.7% – 7.8%18,21,22. This prompted the design of a quality-improvement intervention to standardize swallowing evaluation after TORS for OPSCC and to prospectively follow these patients and assess their swallowing outcomes in the first month after TORS. Therefore, the objective of this study is to prospectively describe short-term dysphagia after TORS for OPSCC. Our primary outcome measure was defined as change in Eating Assessment Tool-10 (EAT-10) scores over the first month of recovery. Our secondary outcome measures included change in pain scores and weight over one month, time to transition to an oral diet, need for feeding tube placement, need for any compensatory swallowing strategies, and dysphagia-related readmissions.

METHODS

This prospective clinical study was approved by the University of Pittsburgh Institutional Review Board. Patients undergoing TORS for resection of OPSCC between June 2014 and March 2016 were prospectively enrolled into this study. Patients were excluded for a history of previous TORS, repeat TORS within one month after enrollment, TORS for non-malignancy, a procedure on a non-oropharyngeal aerodigestive subsite, tracheotomy in the perioperative period, a contraindication to swallowing evaluation, or less than two points of follow-up data. All patients were evaluated by Speech-Language Pathology on post-operative day (POD) 0 or 1 for appropriateness for oral diet as well as any dietary modifications or compensatory strategies needed with repeat evaluations in inpatient or outpatient setting as needed. Compensatory strategies and dietary modifications were utilized to eliminate clinical signs of aspiration present at the bedside and/or improve tolerance of oral intake secondary to pain. MBS (modified barium swallow) or FEES (fiberoptic endoscopic evaluation of swallowing) was not routinely used. The Eating Assessment Tool 10 (EAT-10), a 10-item validated questionnaire measuring dysphagia severity, was used as a measure of swallowing dysfunction (score > 2 is considered abnormal)23,24. This was administered on POD 1, POD 7, and POD 30. Only patients who had at least two administrations of the EAT-10 questionnaire were included in this study. Patient pain level (1–10) was recorded at the same time points and patient weight was recorded at admission, POD 7, and POD 30. Patient demographics and clinical outcomes were recorded prospectively with particular attention paid to need for dietary modifications, temporary feeding tube placement for alternative means of nutrition and dysphagia-related readmissions (dysphagia, dehydration, pneumonia). Temporary feeding tubes used in this study were Dobhoff nasogastric tubes.

Demographic and baseline clinical characteristics including sex, age, T-stage, N-stage, alcohol use at diagnosis, smoking history, preoperative dysphagia, primary TORS site, and neck dissection were summarized. The categorical variables were tested for association with EAT-10 score on POD 30 using either Wilcoxon Mann Whitney or a Kruskal Wallace test and a Spearman correlation coefficient was used to test for association of EAT-10 score at POD 10 with age and N-stage.

Paired T-tests were used to compare changes in EAT-10 scores, weight and pain levels from baseline to POD 7 and POD 30.

Results were based on 2-tailed tests and were considered significant when p<0.05. Analyses were performed in SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary NC) and in R version 3.1.1.

RESULTS

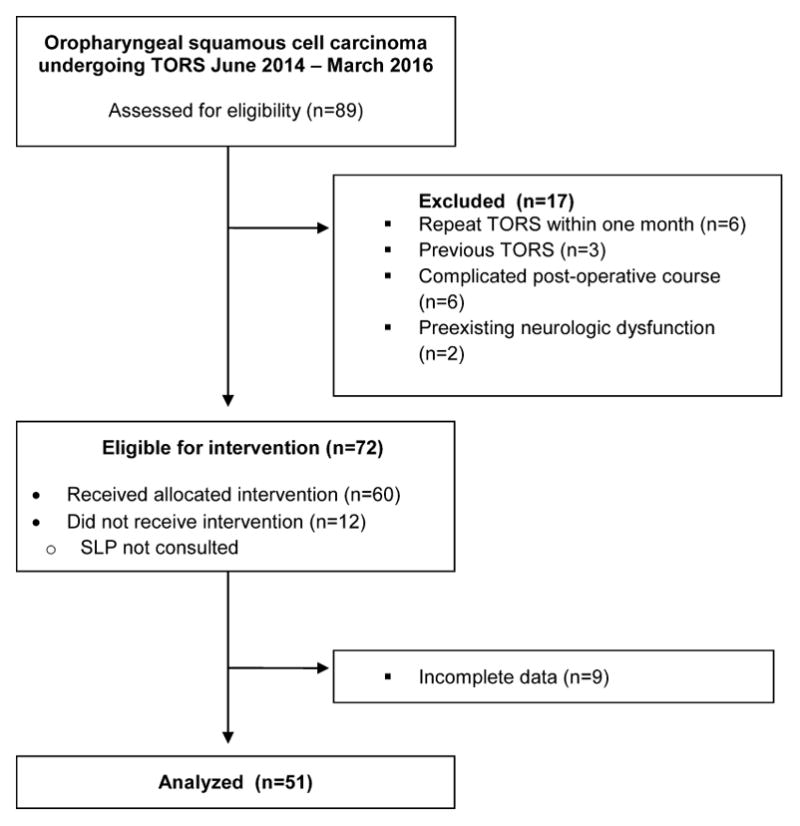

During the study time period, 89 patients underwent TORS for OPSCC and met our inclusion criteria (Figure 1). 77 of these patients were evaluated by Speech-Language Pathology on POD 0/1 and 26 of these patients did not meet our study criteria (3 for previous TORS, 6 for repeat TORS within one month, 9 for less than 2 data points, 6 for complicated post-operative courses and/or tracheotomy precluding accurate swallowing evaluation, 2 for preexisting neurologic dysfunction). 12 patients met the above criteria but were not evaluated by Speech-Language Pathology during their initial hospitalization and were thus not included. This left 51 patients for analysis whose baseline characteristics are depicted in Table I. There were 41 males and 10 females with a median age of 58 years (range 40–74). 30/51 (59%) underwent TORS tonsillectomy with the remainder undergoing base of tongue (BOT) resection. 43/51 (84%) underwent concurrent or staged neck dissection. Most (44/51, 86%) were pathologically staged as T1/T2 although 3 patients were T3 and 4 patients were Tx after bilateral tonsillectomy and BOT resection. 50/51 (98%) patients were p16 positive. 50/51 patients were evaluated on POD 0 or POD 1 by Speech-Language Pathology for a clinical swallowing evaluation and had at least one follow-up data point (POD 7 (n=50) and/or POD 30 (n=47)). One patient did not complete the EAT-10 on POD 1 due to alcohol withdrawal.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram showing the patient composition of the study cohort.

Self-reported preoperative dysphagia was unusual (7/51, 14%). Although preoperative instrumental testing was not routine, 19/51 patients had a preoperative MBS as part of the protocol of Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) 3311 with 8/19 (42%) having some abnormality noted which was generally mild. The primary abnormality noted was premature spillage (6/8), attributed to poor posterior oral bolus control. One patient did demonstrate pre-prandial aspiration with thin liquids, however the patient was observed to be in a retroflexed head position when this occurred. No incidence of aspiration was observed when the patient’s head was properly positioned in the head neutral position. One additional patient demonstrated deep laryngeal penetration without aspiration, secondary to diminished base of tongue strength and decreased hyolaryngeal elevation. Incidence of laryngeal penetration was eliminated with the use of compensatory strategies.

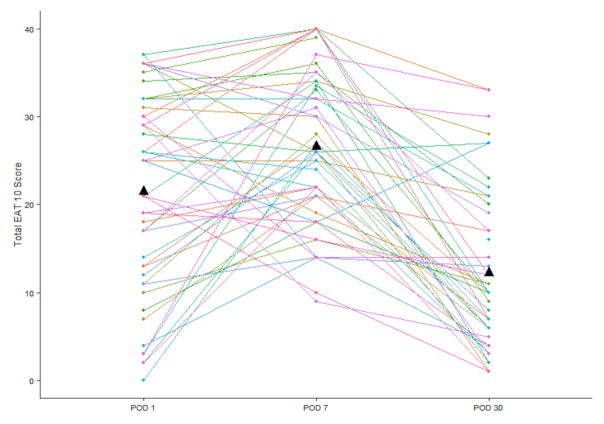

Mean EAT-10 scores increased significantly from POD 1 to POD 7 (21.5 to 26.6, p=0.005) but decreased by POD 30 (26.1 to 12.2, p<0.001) (Figure 2). The mean EAT-10 total score decreased, on average, 8.9 points from POD 1 to POD 30 (p<0.0001). 5/48 (11%) patients had an EAT-10 score <3 at one month.

Figure 2.

Patient EAT-10 scores on post-operative day (POD) 1, POD 7 and POD 30. Mean score at each time point is indicated by triangle.

31 patients had individual EAT-10 component scores recorded prospectively (Table 2). Each of the questions showed an average decrease from POD 1 to POD 30 with the exception of “lose weight.” The greatest decrease was seen in “painful swallowing” with a mean decrease of 1.7.

Table 2.

Change in individual EAT-10 category scores over time

| POD 1 Mean (SD) N=29 |

POD 7 Mean (SD) N=29 |

POD 30 Mean (SD) N=29 |

Paired change from POD 1 – POD 30 Mean (SD) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lose weight | 0.83 (1.4) | 2.38 (1.4) | 1.62 (1.4) | 0.62 (1.9) |

| Ability to out for meals | 2.38 (1.8) | 3.10 (1.0) | 1.34 (1.6) | −1.12 (2.3) |

| Swallowing liquids | 2.28 (1.4) | 2.10 (1.5) | 0.83 (0.9) | −1.62 (1.7) |

| Swallowing solids | 2.69 (1.5) | 3.03 (1.1) | 1.86 (1.3) | −0.96 (1.8) |

| Swallowing pills | 2.34 (1.7) | 2.14 (1.6) | 1.17 (1.2) | −1.30 (2.1) |

| Swallowing is painful | 2.45 (1.4) | 2.60 (1.3) | 0.83 (1.0) | −1.73 (1.6) |

| Pleasure of eating | 2.69 (1.6) | 3.31 (0.8) | 1.72 (1.5) | −1.00 (2.2) |

| Food sticks in throat | 1.86 (1.6) | 2.28 (1.2) | 1.52 (1.2) | −0.46 (1.9) |

| Coughing with eating | 1.07 (1.3) | 1.41 (1.5) | 0.69 (1.0) | −0.42 (1.6) |

| Swallowing is stressful | 2.07 (1.4) | 2.41 (1.3) | 1.06 (1.3) | −1.12 (1.8) |

POD: Post-operative day

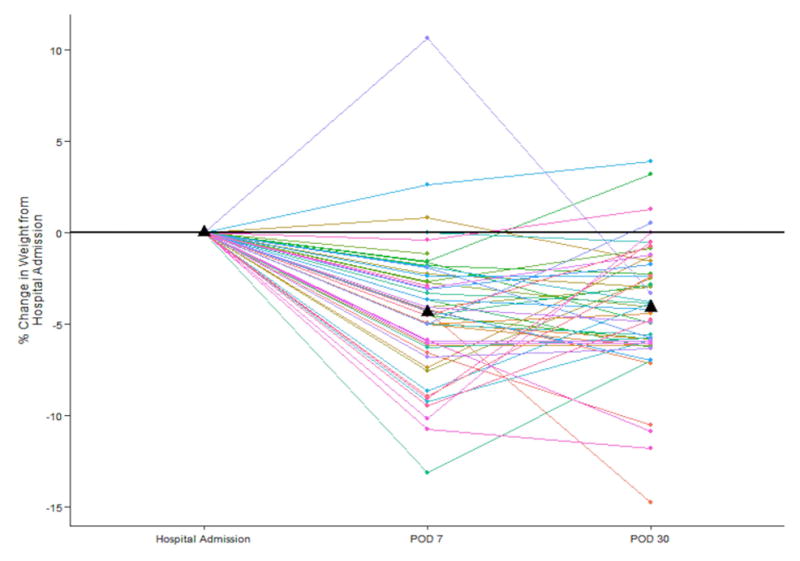

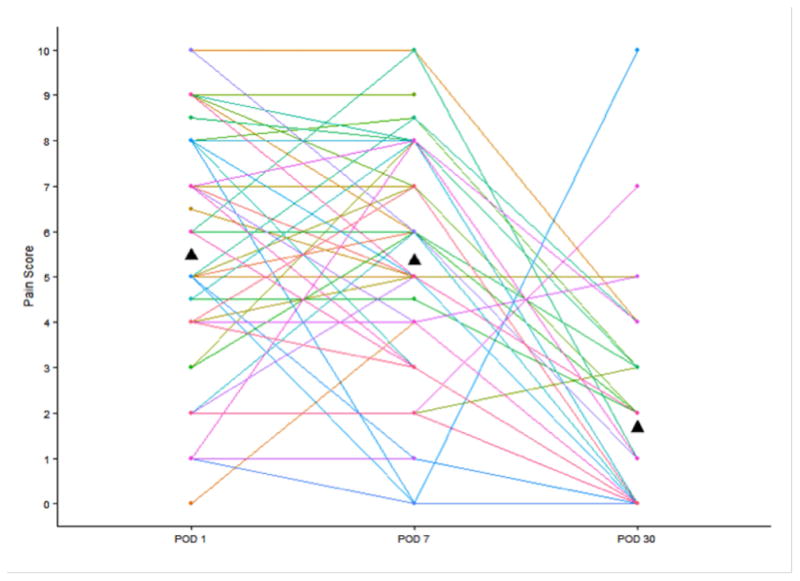

Subject weight decreased, on average, from POD 0 to POD 7 (mean weight, 207.6 to 198.2 lbs respectively, p<0.001) but there was no change in weight between POD 7 and POD 30 (198.8 to 199.7 lbs, p=0.45). Mean percentage change in body weight at 1 month was −4.4% (range +3.8% to −17.4%) (Figure 3). At POD 30 there was an average weight loss of 4.1% of subject body weight at admission (p<0.0001). There was no difference in pain levels between POD 1 and POD 7 (mean difference 0.03 (SD 3.2), p=0.95) but a significant decrease by POD 30 (mean difference −3.9 (SD 3.2), p<0.001) (Figure 4).

Figure 3.

Percentage change in weight in individual patients as compared to date of admission preoperatively. Mean percentage weight change at each time point is indicated by triangle.

Figure 4.

Patient pain scores on post-operative day (POD) 1, POD 7 and POD 30. Mean score at each time point is indicated by triangle.

45/51 (88.2%) patients were started on an oral diet based on a clinical swallow evaluation (POD 0 or POD 1). 2 additional patients were started on an oral diet by the time of discharge: one patient remained intubated until POD 1 and was started on a diet on POD 2 and one patient was kept NPO until POD 3 due to anxiety and discomfort with swallowing and ultimately had feeding tube placed to supplement inadequate oral intake. 4 additional patients remained NPO until outpatient swallowing evaluation (these patients were cleared for oral intake on POD 12, POD 15, POD 18, POD 21).

Six patients (11.8%) required a temporary feeding tube. Two were placed prophylactically at the time of surgery, two on POD 1 for poor oral intake, and two on POD 3 for poor oral intake. Tube feedings were removed an average of 15.6 days post-operatively (range 3 – 31 days). One patient required tube feedings through his adjuvant therapy.

Of the 47 patients cleared for PO intake while inpatient, 45/47 (95.7%) required a soft or pureed consistency for solids. 39/47 (82.9%) patients were able to safely consume thin liquids while 8/47 (17.1%) required nectar- or honey-thickened consistency. 25/47 (53.1%) required postural maneuvers for swallowing such as rotation with or without chin tuck, liquid wash or effortful swallow. Strategies were used to mitigate clinical signs of aspiration (e.g. coughing or throat clearing) and/or to improve reported pain associated with swallowing. Overall, 27/47 (57.4%) required either compensatory strategies or modification of liquid consistency for safe oral intake.

By one month, 50/51 (98.0%) patients were taking an oral diet and 41/51 (80.4%) patients were taking a regular diet. One patient remained feeding tube dependent at the end of one month. 8/16 (50.0%) patients who underwent planned one-month MBS had abnormalities noted, primarily premature spillage, transient laryngeal penetration, or incomplete clearance of bolus. 1/16 (6.25%) had aspiration with thin liquids noted.

5/51 (9.8%) of patients required readmission within 30-days, 4 for post-operative hemorrhage and 1 for nephrolithiasis. None of these readmissions were dysphagia-related.

On univariate analysis only self-reported preoperative dysphagia was associated with a higher EAT-10 score at 30 days (median 19 (interquartile range (IQR) 10–30) vs. 9.5 (IQR 4–17), p=0.04) (Table 3). Those patients who required a temporary feeding tube also had higher mean EAT-10 score at 30 days (28 (IQR 21–30) vs. 9.5 (IQR 4–17), p-value = 0.005). There was no difference predicted by age, sex, T-stage, N-stage, primary subsite, neck dissection or a previous history of radiation therapy.

Table 3.

Univariate associations of factors with 30-day EAT-10 score.

| N | Median (range) | Mean (SD) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 47 | - | - | 0.483 |

| Gender | 0.581 | |||

| Male | 37 | 11 (1, 33) | 12.7 (8.9) | |

| Female | 10 | 8.5 (1, 33) | 11.4 (10.6) | |

| History of H&N surgery | 0.731 | |||

| Yes | 6 | 10 (5, 30) | 13.2 (9.2) | |

| No | 41 | 10 (1, 33) | 12.3 (9.3) | |

| History of XRT | 0.371 | |||

| Yes | 3 | 13 (7, 30) | 16.7 (11.9) | |

| No | 44 | 10 (1, 33) | 12.1 (9.0) | |

| Tobacco use | 0.782 | |||

| Never smoker | 22 | 8.5 (1, 28) | 11.5 (8.8) | |

| Former smoker | 13 | 10 (3, 33) | 12.6 (9.7) | |

| Current smoker | 12 | 12 (1, 33) | 13.9 (9.9) | |

| Daily alcohol use | 0.372 | |||

| Never | 42 | 10 (1, 33) | 11.8 (9.2) | |

| Former | 3 | 21 (6, 27) | 18 (10.8) | |

| Current | 2 | 16.5 (16, 17) | 16.5 (0.7) | |

| Preoperative dysphagia | 0.041 | |||

| Yes | 7 | 19 (6, 33) | 19.7 (10.8) | |

| No | 40 | 9.5 (1, 33) | 11.1 (8.4) | |

| Dysphagia on preoperative MBS | 0.411 | |||

| Yes | 8 | 13 (3, 28) | 14.3 (8.3) | |

| No | 11 | 9 (1, 23) | 10.9 (7.6) | |

| Aspiration on preoperative MBS | 0.411 | |||

| Yes | 1 | 20 (20) | 20 (.) | |

| No | 18 | 10 (1, 28) | 11.9 (7.9) | |

| Primary TORS surgery | 0.661 | |||

| Radical tonsillectomy | 28 | 9.5 (1, 33) | 12.3 (9.6) | |

| BOT | 19 | 11 (3, 33) | 12.6 (8.8) | |

| Neck dissection | 0.662 | |||

| No | 7 | 6 (2, 27) | 10.0 (9.1) | |

| Concurrent | 37 | 10 (1, 33) | 13 (9.6) | |

| Staged | 3 | 11 (10, 11) | 10.7 (0.6) | |

| Local flap | 0.361 | |||

| Yes | 28 | 9.5 (1, 28) | 10.9 (7.3) | |

| No | 19 | 12 (1, 33) | 14.7 (11.2) | |

| T-stage | 0.992 | |||

| TX | 3 | 10 (2, 27) | 13.0 (12.8) | |

| T1 | 23 | 11 (3, 33) | 12.0 (8.1) | |

| T2 | 19 | 9 (1, 33) | 12.7 (10.3) | |

| T3 | 2 | 14 (5, 23) | 14.0 (12.7) | |

| N-stage | 0.863 | |||

| N0 | 7 | 22 (3, 33) | 19 (12) | |

| N1 | 5 | 4 (1, 20) | 6.4 (7.7) | |

| N2a | 10 | 9 (4, 17) | 9.5 (4.4) | |

| N2b | 21 | 12 (1, 33) | 13.9 (9.5) | |

| N2c | 3 | 11 (7, 11) | 9.7 (2.3) | |

| N3 | 1 | 2 (2) | 2 (.) | |

| Subject received feeding tube | 0.0051 | |||

| Yes | 5 | 28 (12, 33) | 24.8 (8.4) | |

| No | 42 | 9.5 (1, 33) | 10.9 (8.1) |

SD=standard deviation;

Wilcoxon Mann Whitney test;

Kruskal-Wallis test;

Spearman correlation

Among the 3 patients with T3 primary tumors, all were able to be started on an oral diet with thin liquids on POD 1. None of them required temporary feeding tube placement.

DISCUSSION

In this prospective cohort we describe the expected post-operative swallowing outcomes in the short-term after patients undergo uncomplicated TORS for oropharyngeal malignancy. Our primary outcome measure was change in EAT-10 scores over time and we found a significant increase in EAT-10 score from POD 1 to POD 7 as well as a substantial decrease by POD 30. While there is limited data on swallowing outcomes in the TORS literature after resection of OPSCC the two studies which we identified which have reported data within that time period show improved but not normalized HRQOL and MDADI scores by 3 weeks16,17. This is consistent with our data which shows that 34/46 (73.9%) of patients will have improved EAT-10 scores by 1 month as compared with POD 1 and 42/46 (91%) of patient as compared with POD 7. Despite significant improvement by POD 30, only 10% of patients normalized (EAT-10 < 3) which suggests that normal swallowing function should not be expected by one month and, by extrapolation, the start of radiation therapy. In those who do not receive adjuvant chemo/radiation therapy others have reported normalization of patient-reported swallowing outcome measures by 3 months11,20.

Most (45/51, 88.2%) of the patients were started on an oral diet by POD 1 while 46/51 (90.1%) of the patients were discharged on an oral diet (1 patient required feeding tube placement once cleared for an oral diet and two patients were cleared for oral intake on POD 2 and 3 prior to discharge). Despite continued elevation of EAT-10 scores at one month after TORS, 98% of patients are able to be continued on an oral diet without the need for tube feeding supplementation and 80% of patients are able to take a regular diet. This is higher than previously reported in the literature with 69–73% of patients reported beginning oral intake prior to discharge, 83% by week 2 and 89% by 1 month18,25–27.

Our feeding tube placement rate was 11.8% with the majority of these patients requiring feeding tube placement in the postoperative setting due to inability to tolerate an oral diet safely as determined by Speech-Language Pathology or to supplement oral intake. Feeding tube placement rates in the literature vary widely in reported series from 3 – 100% with a mean placement rate of 33% with several groups still advocating for routine intraoperative feeding tube placement25. However, based off of these results, we believe that feeding tube placement can be safely avoided in the majority of patients.

The time to oral intake and feeding tube rates are lower as compared to previously reported series which could be related to several factors. The inclusion of only those with uncomplicated postoperative courses may explain some of this difference although only 6 such patients were excluded for this reason and of our entire TORS experience over this time period, 18.5% of patients required a temporary feeding tube which is still well below previous reported frequencies. Similarly, our practice of a team-based approach with a Speech-Language Pathology evaluation of each patient for swallowing dysfunction and appropriate diet as well as any compensatory strategies needed could have allowed more patients to be started on a safer diet sooner. Given that in this series, 57.4% of patients require compensatory strategies or are not able to tolerate thin liquids safely we would advocate that Speech-Language Pathology evaluation be routine in the post-operative setting after TORS for OPSCC. We believe that among appropriately selected patients oral intake should be the expectation prior to discharge and nearly all patients can be expected to have begun oral intake within one month.

Dysphagia-related readmissions after TORS, most notably aspiration pneumonia, are not common although they are inconsistently reported within the TORS literature. Among those who have reported it, the readmission rate ranges from 4.7% – 7.8%18,21,22. This is similar to our past experience of a 6.3% dysphagia-related readmission rate. After our initiation of this quality improvement initiative we did not have any dysphagia-related readmissions or incidences of aspiration pneumonia. Whether this is due to more careful evaluation of dysphagia in the immediate post-operative setting or to better surgical technique or patient selection or chance is unclear. Regardless, this should continue to be an area of active evaluation and quality improvement amongst TORS surgeons.

Reporting of objective swallowing outcomes with instrumental testing such as MBS or FEES has been identified as an area of need within the TORS literature25. Instrumental testing was not necessary prior to initiation of diet in the immediate post-operative setting. However, among those who were discharged with a feeding tube, MBS or FEES was used in all cases prior to initiation of diet. Additionally, in a subset of our cohort a planned 1-month MBS was obtained as part of the protocol of ECOG 33118. 8/17 patients who underwent planned post-operative MBS exhibited abnormalities. Of these patients, the majority (63%) had demonstrated dysphagia on pre-operative MBS. The primary characteristics were again noted to be premature spillage, as well as transient penetration. The incidence of deep laryngeal penetration or aspiration did not increase. Patients were, however, observed to have increased pharyngeal residue compared to initial MBS. One patient who required a feeding tube did have new aspiration of thin liquids post-operatively on planned MBS. Interestingly, abnormalities on pre-operative MBS such as premature spillage, penetration or post-swallow residuals did not predict post-operative outcomes including EAT-10 score, weight loss or need for feeding tube. Self-reported pre-operative dysphagia, on the other hand, was predictive of needing post-operative feeding tube (42.9% vs. 6.8%) and 1-month EAT-10 score but there was no difference in weight loss. Thus, patients with preoperative subjective dysphagia should be counseled that they are at risk of worsened short-term swallowing outcomes.

Strengths of this study are its prospective nature and minimal loss to follow-up. Limitations of this study include the lack of preoperative EAT-10 scores. Although self-reported preoperative dysphagia was unusual in this study others have reported abnormalities in up to 40% of preoperative TORS patients screened with the MD Anderson Dysphagia Index17. Our experience is that most TORS patients have small HPV-related tumors and, as such, have limited self-reported dysphagia prior to surgery. This is borne out in our data (14% self-report dysphagia). Also, although not part of the design of the study, 32 TORS patients (including 19 in this cohort) have pre-operative EAT-10 scores with 27/32 (85%) in the normal range. Our objective of the study was to show the natural course of swallowing sympatomatology after TORS which has been inadequately characterized to this point. Not having baseline data certainly limits the interpretability of the 30-day EAT-10 score as it relates to the patient baseline but we do not think it limits interpretation of the trends in the post-operative period.

While our study is also limited by the lack of a functional swallowing assessment, we think that functional swallowing assessment is not necessary in the vast majority of TORS (oropharynx) patients. Most patients who do not have a tracheotomy and who are not frail at baseline do quite well from a swallowing standpoint and this is borne out in this study. Only 4 patients required functional swallowing testing prior to initiation of diet. Among the 51 patients assessed in this study, there were no dysphagia-related readmissions or episodes of aspiration pneumonia. Thus, we think that careful bedside swallowing evaluation by a trained Speech-Language Pathologist is a safe first step and that functional swallowing assessment can be reserved for those who there remains concern for potential aspiration. However, there will remain doubt until prospective functional swallowing assessment data on TORS patients is published. Fortunately, this data is being collected as part of the protocol of ECOG 3311 and should be available when that study population is mature. While we recognize that another limitation is its lack of inclusion of patients with complicated postoperative course we feel this work can be generalized to most patients undergoing TORS for OPSCC.

Further, other symptomatology which may be germane to patients undergoing TORS including trismus and velopharyngeal insufficiency was not assessed in this study and we would advocate for further prospective data in these areas.

CONCLUSION

Dysphagia is common in the first month after TORS when patients are followed prospectively. Despite elevated EAT-10 scores up to a month post-operatively, adverse dysphagia-related outcomes are rare. Evaluation for dysphagia should be considered routine in this cohort of patients given the prevalence of dietary modifications and compensatory strategies needed.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patients

| Characteristic | N (N=51) | % |

|---|---|---|

| Age | ||

| mean (SD) | 57 (8) | |

| median (range) | 58 (40–74) | |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 41 | 80 |

| Female | 10 | 20 |

| History of H&N surgery | ||

| Yes | 6 | 12 |

| No | 45 | 88 |

| History of radiation | ||

| Yes | 3 | 6 |

| No | 48 | 94 |

| Tobacco use | ||

| Never smoker | 24 | 47 |

| Former smoker | 14 | 27.5 |

| Current smoker | 13 | 25.5 |

| Daily alcohol use | ||

| Never | 46 | 90 |

| Former | 3 | 6 |

| Current | 2 | 4 |

| Preoperative dysphagia | ||

| Yes | 7 | 14 |

| No | 44 | 86 |

| Primary TORS | ||

| Radical tonsillectomy | 30 | 59 |

| Base of tongue resection | 21 | 41 |

| Neck dissection | ||

| No | 8 | 16 |

| Concurrent | 40 | 78 |

| Staged | 3 | 6 |

| Local flap | ||

| Yes | 32 | 63 |

| No | 19 | 37 |

| T-stage | ||

| TX | 4 | 8 |

| T1 | 24 | 47 |

| T2 | 20 | 39 |

| T3 | 3 | 6 |

| N-stage | ||

| N0 | 7 | 14 |

| N1 | 5 | 10 |

| N2a | 11 | 22 |

| N2b | 24 | 47 |

| N2c | 3 | 6 |

| N3 | 1 | 2 |

| P16 | ||

| Yes | 50 | 98 |

| No | 1 | 2 |

TORS: transoral robotic surgery

SD: standard deviation

Footnotes

There are no conflicts of interest to disclose.

DISCLOSURES

Contract grant sponsor: This project was conducted using the University of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute Biostatistics Facility that is supported in part by award from the National Institutes of Health - P30CA047904.

This works was supported in part by a Career Development Award from the Department of Veterans Affairs, BLR&D and a grant from the PNC Foundation (U.D.).

This work does not represent the views of the US Government nor the Department of Veterans Affairs.

References

- 1.Weinstein GS, O’Malley BW, Jr, Snyder W, Sherman E, Quon H. Transoral robotic surgery: radical tonsillectomy. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;133(12):1220–1226. doi: 10.1001/archotol.133.12.1220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100(1):33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Machtay M, Moughan J, Trotti A, et al. Factors associated with severe late toxicity after concurrent chemoradiation for locally advanced head and neck cancer: an RTOG analysis. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(21):3582–3589. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forastiere AA, Zhang Q, Weber RS, et al. Long-term results of RTOG 91-11: a comparison of three nonsurgical treatment strategies to preserve the larynx in patients with locally advanced larynx cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(7):845–852. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.6097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Almeida JR, Li R, Magnuson JS, et al. Oncologic Outcomes After Transoral Robotic Surgery: A Multi-institutional Study. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(12):1043–1051. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.1508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.de Almeida JR, Byrd JK, Wu R, et al. A systematic review of transoral robotic surgery and radiotherapy for early oropharynx cancer: a systematic review. Laryngoscope. 2014;124(9):2096–2102. doi: 10.1002/lary.24712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morisod B, Simon C. Meta-analysis on survival of patients treated with transoral surgery versus radiotherapy for early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx. Head Neck. 2016;38(Suppl 1):E2143–2150. doi: 10.1002/hed.23995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holsinger FC, Ferris RL. Transoral Endoscopic Head and Neck Surgery and Its Role Within the Multidisciplinary Treatment Paradigm of Oropharynx Cancer: Robotics, Lasers, and Clinical Trials. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(29):3285–3292. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.3157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nichols AC, Yoo J, Hammond JA, et al. Early-stage squamous cell carcinoma of the oropharynx: radiotherapy vs. trans-oral robotic surgery (ORATOR)--study protocol for a randomized phase II trial. BMC Cancer. 2013;13:133. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-13-133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chaturvedi AK, Anderson WF, Lortet-Tieulent J, et al. Worldwide trends in incidence rates for oral cavity and oropharyngeal cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(36):4550–4559. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Choby GW, Kim J, Ling DC, et al. Transoral robotic surgery alone for oropharyngeal cancer: quality-of-life outcomes. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2015;141(6):499–504. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Almeida JR, Park RC, Villanueva NL, Miles BA, Teng MS, Genden EM. Reconstructive algorithm and classification system for transoral oropharyngeal defects. Head Neck. 2014;36(7):934–941. doi: 10.1002/hed.23353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Park YM, Kim WS, Byeon HK, Lee SY, Kim SH. Oncological and functional outcomes of transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal cancer. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2013;51(5):408–412. doi: 10.1016/j.bjoms.2012.08.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.More YI, Tsue TT, Girod DA, et al. Functional swallowing outcomes following transoral robotic surgery vs primary chemoradiotherapy in patients with advanced-stage oropharynx and supraglottis cancers. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;139(1):43–48. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2013.1074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leonhardt FD, Quon H, Abrahao M, O’Malley BW, Jr, Weinstein GS. Transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal carcinoma and its impact on patient-reported quality of life and function. Head Neck. 2012;34(2):146–154. doi: 10.1002/hed.21688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurtuk AM, Marcinow A, Agrawal A, Old M, Teknos TN, Ozer E. Quality-of-life outcomes in transoral robotic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;146(1):68–73. doi: 10.1177/0194599811421298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sinclair CF, McColloch NL, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL, Desmond RA, Magnuson JS. Patient-perceived and objective functional outcomes following transoral robotic surgery for early oropharyngeal carcinoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137(11):1112–1116. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Iseli TA, Kulbersh BD, Iseli CE, Carroll WR, Rosenthal EL, Magnuson JS. Functional outcomes after transoral robotic surgery for head and neck cancer. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;141(2):166–171. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2009.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Genden EM, Kotz T, Tong CC, et al. Transoral robotic resection and reconstruction for head and neck cancer. Laryngoscope. 2011;121(8):1668–1674. doi: 10.1002/lary.21845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moore EJ, Olsen KD, Kasperbauer JL. Transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective study of feasibility and functional outcomes. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(11):2156–2164. doi: 10.1002/lary.20647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Aubry K, Vergez S, de Mones E, et al. Morbidity and mortality revue of the French group of transoral robotic surgery: a multicentric study. J Robot Surg. 2016;10(1):63–67. doi: 10.1007/s11701-015-0542-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cognetti DM, Luginbuhl AJ, Nguyen AL, Curry JM. Early adoption of transoral robotic surgical program: preliminary outcomes. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;147(3):482–488. doi: 10.1177/0194599812443353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Belafsky PC, Mouadeb DA, Rees CJ, et al. Validity and reliability of the Eating Assessment Tool (EAT-10) Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2008;117(12):919–924. doi: 10.1177/000348940811701210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang K, Amdur RJ, Mendenhall WM, et al. Impact of post-chemoradiotherapy superselective/selective neck dissection on patient reported quality of life. Oral Oncol. 2016;58:21–26. doi: 10.1016/j.oraloncology.2016.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hutcheson KA, Holsinger FC, Kupferman ME, Lewin JS. Functional outcomes after TORS for oropharyngeal cancer: a systematic review. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2015;272(2):463–471. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-2985-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moore EJ, Olsen SM, Laborde RR, et al. Long-term functional and oncologic results of transoral robotic surgery for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(3):219–225. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2011.10.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Abel KM, Moore EJ, Carlson ML, et al. Transoral robotic surgery using the thulium:YAG laser: a prospective study. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(2):158–166. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]