Abstract

The cochlea and the vestibular organs are populated by resident macrophages, but their role in inner ear maintenance and pathology is not entirely clear. Resident macrophages in other organs are responsible for phagocytosis of injured or infected cells, and it is likely that macrophages in the inner ear serve a similar role. Hair cell injury causes macrophages to accumulate within proximity of damaged regions of the inner ear, either by exiting the vasculature and entering the labyrinth or by the resident macrophages reorganizing themselves through local movement to the areas of injury. Direct evidence for macrophage engulfment of apoptotic hair cells has been observed in several conditions. Here, we review evidence for phagocytosis of damaged hair cells in the sensory epithelium by tissue macrophages in the published literature and in some new experiments that are presented here as original work. Several studies also suggest that macrophages are not the only phaogocytic cells in the inner ear, but that supporting cells of the sensory epithelium also play an important role in debris clearance. We describe the various ways in which the sensory epithelia of the inner ear are adapted to eliminate damaged and dying cells. A collaborative effort between resident and migratory macrophages as well as neighboring supporting cells results in the rapid and efficient clearance of cellular debris, even in cases where hair cell loss is rapid and complete.

Keywords: phagocytosis, macrophage, hair cell, inflammation, supporting cell

Introduction

The events leading to hair cell loss have been rigorously studied, and the role of supporting cells in the sensory epithelium has been shown to be interesting and important during the loss of the sensory cells. In order to maintain the separation between perilymph and endolymph, the gaps that form in the sensory epithelium from loss of hair cells must be filled by the adjacent supporting cells. Recent studies indicate that hair cell death is indeed accompanied by a coordinated series of events that involve both hair cells and supporting cells. After injury, supporting cells expand to fill the space that remains after hair cell shrinkage and apoptosis, and restores the integrity of the reticular lamina. Furthermore, a number of studies have shown that supporting cells participate in clearing cellular debris during the process of hair cell death (Li et al., 1995; Abrashkin et al., 2006).

While the supporting cells are the closest neighbors to the hair cells, macrophages also live within the membranous labyrinth and are capable of responding to hair cell injury. Tissue macrophages are often the first-responders to local injury in many organ systems, where they contribute to the removal of cellular debris (Wynn and Vannelia, 2016). The inner ear is populated by resident macrophages and additional mononuclear phagocytes are readily recruited into the ear after injury. Activation of such cells could be an excellent method to augment and hasten the process of debris clearance (Savill and Fadok, 2000). Our laboratories have reported the recruitment of phagocytes into the mouse cochlea after acoustic injury and aminoglycoside ototoxicity (Hirose et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2009) and into the mouse cochlea and vestibular organs after selective hair cell ablation (Kaur et al., 2015a; 2015b). Using immunohistochemistry of fixed tissue, we have noted macrophage engulfment of vestibular hair cells, but have rarely observed macrophage-mediated phagocytosis in the injured cochlea. One possible explanation is that cochlear phagocytosis occurs rapidly and is difficult to capture in fixed tissue where only one time point is sampled.

All of the mechanisms that lead to the removal of hair cell debris appear to be initiated during the early phases of cell death, but the molecular signals that trigger such responses have not been identified. It is notable that there are different strategies for removal of cellular debris in different inner ear sensory organs. In some cases, dying hair cells remain in place and become condensed and fragmented, and are then surrounded and partially engulfed by nearby supporting cells. Other sensory epithelia appear to eject injured, but apparently intact hair cells from the sensory epithelium into the endolymph. Macrophages have also been observed to engulf hair cell debris. As described below, the precise method of debris clearance varies by species and by sensory organ (mammals versus birds and amphibians, cochlear versus vestibular organs).

In this review, we examine the role of both supporting cells and macrophages in the clearance of hair cell debris. We also report data from several new studies that further characterize the interaction between macrophages and dying hair cells. In one study, we have used time-lapse imaging of organotypic cultures of the mouse organ of Corti, in order to observe the actions of macrophages after aminoglycoside ototoxicity. Under these conditions, we show that macrophages are able to both identify and phagocytose dying hair cells. Previous studies have also indicated that CD36, which is expressed on the surface of macrophages, is critical for identifying cellular targets for phagocytosis and that CD36 knockout mice suffer from impaired phagocytosis (Silverstein and Febbraio, 2009). With time-lapse recording of organotypic cultures, we assessed whether CD36 is necessary for phagocytosis of damaged sensory cells, and whether deletion of CD36 would influence cochlear repair. Finally, we have characterized macrophage activity in lateral line neuromasts of larval zebrafish following ototoxic injury. We show that macrophages enter lesioned neuromasts and engulf the debris of dying hair cells. These new findings, combined with previous data, support the notion that cellular debris is removed from the sensory epithelia of the inner ear by both supporting cells and macrophages.

Phagocytosis by Professionals: Macrophages

Macrophages are present in the inner ear during development

Macrophages populate the central nervous system during early development, and we have limited data suggesting that macrophages are also present in the inner ear during early development. We have observed macrophages associated with the otic vesicle at E10 (Figure 1). The earliest myeloid cells that populate the embryo are derived from the yolk sac, including the primitive myeloid precursors that differentiate into microglia that migrate to the central nervous system. Subsequently, the fetal liver is the source of hematopoiesis. Later in mature mice, cochlear macrophages derive from the bone marrow and are released into circulation as monocytes. They constitutively express CX3CR1 (fractalkine receptor). This chemokine receptor can act as a chemotactic factor and as a strong adhesion molecule when coupled with its ligand. CX3CR1 has a unique ligand, CX3CL1, or fractalkine, which is primarily expressed by neurons. Monocytes migrate into target tissues and may differentiate into tissue macrophages where they may remain long term (Hoeffel and Ginhoux, 2015; Ginhoux and Guilliams, 2016). Tissue macrophages typically spend their entire lives in their target organs; when they undergo senescence, they are phagocytosed by other tissue macrophages. The time course and source of macrophages in the cochlea has not been studied systematically, and the potential sources of cochlear macrophage precursors includes both yolk sac-derived and bone marrow-derived macrophages. Further studies are needed to determine the sources of tissue macrophages.

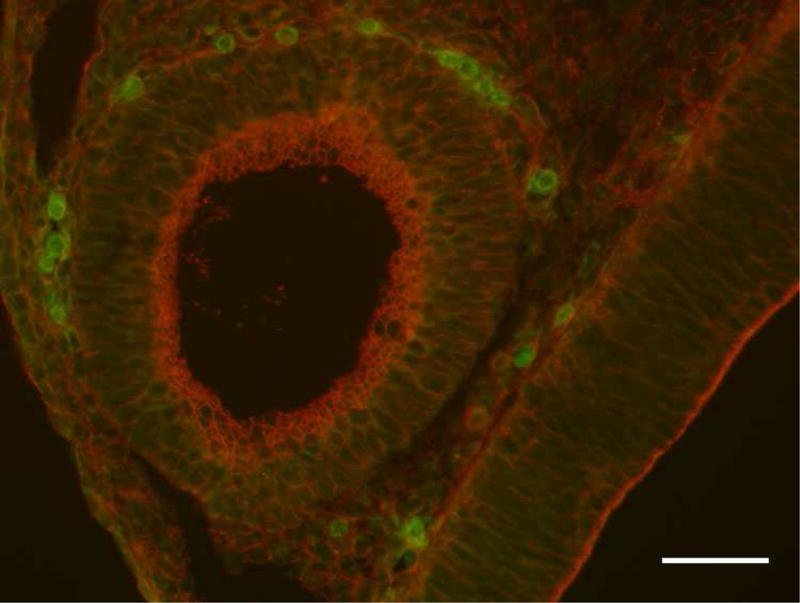

Figure 1.

E10 mouse embryo. Macrophages are observed adjacent to the otic vesicle at embryonic day 10 suggesting that macrophages may play a significant role during this period of inner ear development. Selection and elimination of unwanted cells may be undertaken by these local tissue macrophages. Green: CX3CR1GFP(macrophages), Red: phalloidin (f-actin). Scale bar: 50μm.

In addition to resident tissue macrophages, monocytes, derived from myeloid precursors in the bone marrow, circulate through tissues in the blood and patrol peripheral organs. These cells explore the somatic organs and reenter the circulation after a transient period of surveillance in target tissues. These cells express CCR2 and are described as “inflammatory” monocytes (Geissmann et al., 2003; Auffray et al., 2007; Geissmann et al., 2010; Schulz et al., 2012). These inflammatory monocytes are recruited to target tissues including the inner ear under more specific circumstances, such as in sepsis and in infectious conditions such as in bacterial meningitis (Hirose et al., 2014b). The CCR2 monocytes are not present in the inner ear of control animals. CCR2 monocytes are observed in the inner ear under circumstances where the blood labyrinth barrier is compromised, such as after LPS exposure, analogous to low level sepsis or in bacterial infection (Hirose et al., 2014a).

Cochlear macrophages in the mature ear

Local tissue macrophages are mobile and interact with their surroundings by extending processes or pseudopodia that are several times the length of the cell soma. While macrophages often occupy specific regions of the cochlea and tend to congregate in the spiral ganglion or in the spiral ligament, their processes continuously reach out and retract to sample the environment as far away as 25–50 microns. In the normal mammalian cochlea, tissue macrophages generally reside in two areas, the lateral wall and the spiral ganglion. In the lateral wall, macrophages are distributed among the fibrocytes, primarily concentrated among the type II and type IV fibrocytes. There are also macrophages of the stria vascularis, best described as perivascular macrophages. Others have called these cells ‘perivascular macrophage-like melanocytes’ (Zhang et al., 2012). However, an alternate explanation for the observed melanin in these phagocytes is the presence of melanin byproduct from ingested intermediate cells of the stria vascularis. In the spiral ganglion, tissue macrophages are uniformly distributed among neurons and satellite cells (see schematic diagram in Figure 2, adapted from Hirose et al., 2005.) There is typically a small population of macrophages that inhabit the spiral limbus and are located in the region where the tectorial membrane attaches to the limbus.

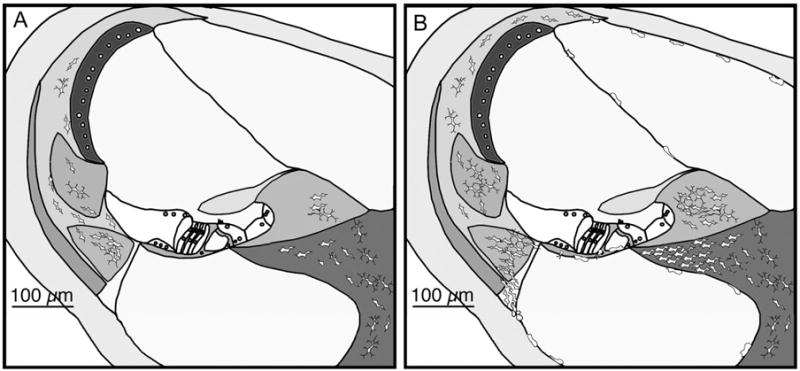

Figure 2.

Schematic figure shows the typical location of macrophages in the mammalian cochlea. A. Control mouse cochlea shows tissue macrophages in the spiral ligament and ganglion in the resting ear. B. Cochlear macrophages migrate from the vasculature after noise exposure. Mononuclear phagocytes typically accumulate in large numbers in the spiral ligament, spiral limbus, and in the spiral ganglion. They also enter the fluid-filled scalae and assume a rounded and less ramified shape when they migrate out of the spiral ligament.

Cochlear macrophages are tissue macrophages, not microglia

We have characterized these cochlear macrophages by their surface markers and functional proteins, and they demonstrate properties of typical tissue macrophages. They express CD45 (common leukocyte antigen), CD68 (lysosome associated membrane protein), iba-1, and CX3CR1 (fractalkine receptor). These cells do not express CD3, CD4, CD8, DEC-205, myeloperoxidase, NK1.1 or CCR2 (Hirose et al., 2005). Their large size, thick processes, and focal distribution within the inner ear are reminiscent of tissue macrophages and not microglia. By comparison to cochlear macrophages, microglia are smaller, have finer processes, are more regularly distributed within the brain parenchyma, and most importantly, are a terminally differentiated population of cells that originates from the yolk sac and is not replaced by bone marrow-derived leukocytes (Ajami et al., 2007; Ginhoux et al., 2010).

Unlike microglia, the population of inner ear macrophages has a regular rate of turnover, and circulating monocytes derived from myeloid precursors serve as a pool to replace these tissue macrophages. Murine bone marrow chimeras illustrate this feature of cochlear macrophages. We created bone marrow chimeric mice by irradiating wild-type mice, thus eliminating all the hematopoietic cells, and then transplanting new bone marrow from a donor in order to replace the native blood cells with endogenously fluorescent bone marrow (Sato et al., 2008). Inner ear macrophages, like the bone marrow, are vulnerable to radiation and are eliminated with a single dose of gamma radiation (900cGY). After the irradiated mice received bone marrow transplants from healthy donors, mice reconstituted the cochlear macrophages from the donor bone marrow within 2–3 months (Sato et al, 2008). Microglia do not repopulate from bone marrow precursors. Primitive yolk sac macrophages from the embryo are the progenitors of microglia, and bone marrow precursors do not produce new microglia either in development or in the mature mouse (Ajami et al., 2007; Ginhoux et al., 2010). Thus, we believe that ‘microglia’ is not the proper term for the population of myeloid cells in the cochlea because cochlear macrophages have a baseline rate of turn over and they are replaced by bone marrow. We have used the term ‘macrophage’ and not ‘microglia’ to designate these resident mononuclear phagocytes of the inner ear (Hirose et al., 2005).

Cochlear and vestibular macrophages have been observed in mice, birds, zebrafish, and in humans (Warchol, 1997; Hirose et al., 2005; Carrillo et al., 2016; O’Malley et al., 2016). Human temporal bone studies have shown an abundance of local tissue macrophages in the lateral wall, the spiral limbus, the osseus spiral lamina, and in the spiral ganglion. These human cochlear specimens demonstrate that these cells have similar markers to mouse cochlear macrophages, including iba-1 and CD68. While the regions of the cochlea bathed in perilymph are replete with tissue macrophages, the scala media, which contains endolymph, has very few macrophages, as we have observed in the mouse. Avian macrophages of the basilar papilla label with KUL01, a marker for monocytes and macrophages, and are distributed in large numbers along the abneural border of the sensory epithelium. Zebrafish also have tissue macrophages and circulating myeloid cells. With the use of molecular reagents, endogenously fluorescent macrophages are easily studied in vivo as these fish are translucent and cells can be imaged in live animals.

Macrophages in the damaged mammalian cochlea

Several studies have reported evidence for the infiltration of circulating monocytes and macrophages into the cochlea after injury. Macrophages migrate from the vasculature and preferentially enter the spiral ligament and the spiral limbus through blood vessels that perfuse the perilymph-filled regions of the mammalian cochlea (Fredelius and Rask-Andersen, 1990; Hirose et al., 2005; Tan et al., 2008). The vessels of the stria vascularis however, do not allow migration of leukocytes into the intrastrial space. The number of macrophages in the stria vascularis demonstrates little variation even in conditions of severe inflammation. The permeability of the strial capillaries to inflammatory cells appears to be distinctly different from that of the vessels that perfuse the spiral ligament, limbus and ganglion.

Noise, aminoglycoside antibiotics, aging, and diphtheria toxin-mediated targeted hair cell ablation all induce macrophage migration into the inner ear (Hirose et al., 2005; Sato et al., 2010; Hirose and Sato, 2011; Hirose et al., 2014a; Kaur et al., 2015b; Yang et al., 2015). These insults cause varying degrees of cochlear damage. Noise causes damage to both sensory and non-sensory inner ear structures while diphtheria toxin in the Pou4f3-huDTR mouse causes selective hair cell loss. After injury caused by noise exposure or aminoglycoside ototoxicity, macrophages accumulate in the cochlea in predictable locations, primarily in the spiral ligament and in the spiral ganglion. The observation that enhanced numbers of macrophages are observed after diphtheria toxin-mediated hair cell lesions (which cause no other apparent cochlear pathology) suggest that hair cell injury alone is sufficient to recruit macrophages into the cochlea (Kaur et al., 2015b). Other sources of injury, such as bacterial or viral infections, pneumococcal meningitis or congenital cytomegalovirus, evoke a more robust inflammatory response marked by recruitment of a diversity of leukocytes in addition to the mononuclear phagocytes present in non-infectious conditions of the inner ear.

Boundaries and neighborhoods of cochlear macrophages

In both healthy and injured inner ears, the macrophage population remains within scala vestibuli and scala tympani, compartments that contain perilymph (Hirose et al., 2005). The sensory epithelium of the cochlea is situated between two fluid compartments. The fluid in the space above the reticular lamina (scala media) is known as endolypmph, while the fluid below the reticular lamina (scala tympani) is called perilymph. It is rare to observe a macrophage within the scala media, likely due to the high potassium content of endolymph. Instead, processes from macrophages are often seen reaching from the scala tympani into the organ of Corti, presumably directed towards damaged sensory cells (Figure 3). There are two locations where macrophages migrate in the setting of hair cell injury: the habenula perforata is often crowded with macrophages alongside the afferent fibers of the spiral ganglion neurons (Sato et al., 2010). The undersurface of the basilar membrane in the scala tympani is also frequently the site of migrating cochlear macrophages (Hirose et al., 2005). They appear to seek or to create gaps where processes can reach through the basilar membrane to ingest dying sensory cells (Figure 3). These are the most frequent access points by which we observe interactions between macrophages and sensory cells in the damaged organ of Corti. Thus, due to the handicap of being poorly equipped to contact endolymph, the macrophages attain access to the sensory epithelium from perilymphatic spaces via mobility and extension of cytoplasmic processes through small gaps. Localization of damaged cells is likely assisted by cues elaborated by cells in distress. However, the specific cues that provide homing signals to cochlear macrophages are not yet known.

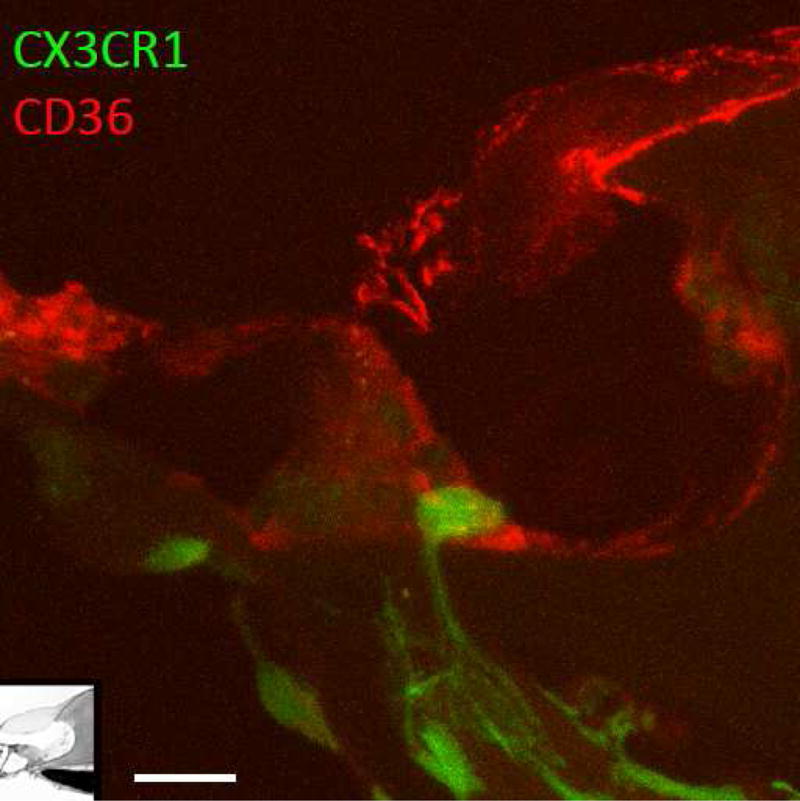

Figure 3.

Macrophages reach into the sensory epithelium in situ. Macrophage extending a process from the osseous spiral lamina through the habenula perforata towards the inner hair cell. The cochlea was fixed in vivo and then sectioned for light microscopy. Green: CX3CR1GFP (macrophage), Red: CD36 (scavenger receptor B). Scale bar: 10μm.

Cochlear macrophages phagocytose damaged hair cells in vitro

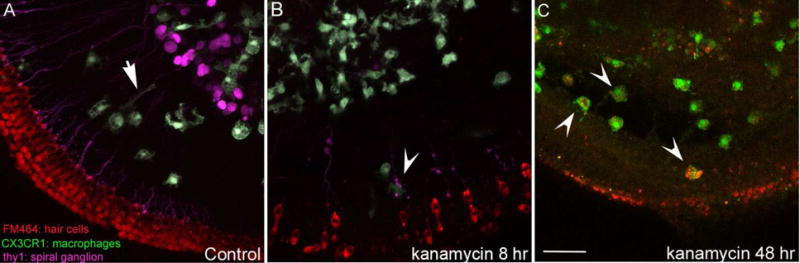

Time-lapse video studies of organotypic cultures of the mouse cochlea indicate that hair cell injury causes macrophages to migrate towards injured cells and to surround and consume damaged cells and the remaining debris. During the process of hair cell degeneration, macrophages send out multiple processes in rapid succession toward the damaged sensory epithelium. In culture media (which possess ionic concentrations similar to perilymph rather than endolymph), cochlear macrophages migrate to the sensory cells, sometimes positioning themselves directly underneath or on top of the sensory epithelium, and send out long processes to encircle hair cells (Figure 4). Within 24–48 hours of kanamycin application, macrophages internalize hair cell remnants in phagosomes (Figure 5C).

Figure 4.

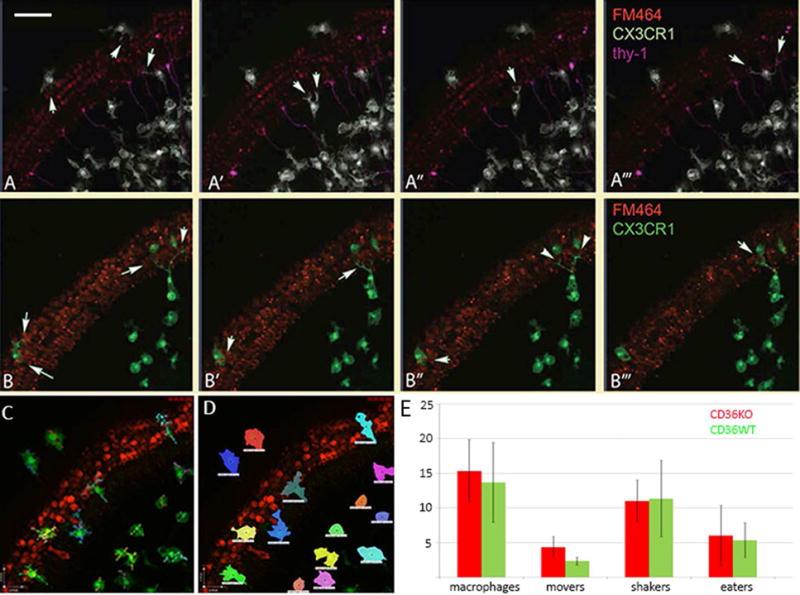

Time-lapse images from newborn mouse cochlear cultures.

A–A′″. Still images from time-lapse experiments highlight processes and displacement of cochlear macrophages. Mouse cochlear cultures were treated with kanamycin and hair cells were identified with FM464. Macrophages (white) are observed among the spiral ganglion neurons (magenta), locating injured hair cells and extending processes to engulf them. Arrows demonstrate processes extending around hair cells. Scale bar: 50μm.

B–B′″. Organotypic cultures harvested from CD36 null, CX3CR1GFP reporter mice. CD36 null macrophages were mobile, identified damaged hair cells readily and were active in phagocytosis. Arrows demonstrate processes surrounding and engulfing hair cells. Red: FM464 (hair cells), green: CX3CR1GFP (macrophages).

C. Example of cell length measurement in macrophages in culture.

D. Representative image of technique used to assess macrophage movement: all pixels that corresponded to individual macrophages were identified and followed over time. Displacement of macrophages in CD36KO mice were not different from displacement of CD36 WT mice (data not shown).

E. Numbers of macrophage types in CD36KO and CD36WT mice, where “movers” freely displaced greater than the length of a cell soma with X minutes, “shakers” extended processes while remaining in one location, and “eaters” consumed red material. There was no significant difference in numbers of movers, shakers, or eaters observed in CD36KO mice when compared to WT mice (two-tailed T test, n=220 macrophages assessed, compilations of videos from 8 preparations of CD36KO and 7 from CD36WT cochleae). Abbreviations: CD36KO: CD36 null mice, CD36WT: CD36 wild type mice.

Figure 5.

Confocal images of cochlear macrophages, whole mount preparation.

A. Control mouse organotypic cochlear culture: macrophages are concentrated among the spiral ganglion neurons. Some macrophages extend processes towards the hair cells along the afferent neurons (arrow). Red: FM464 (hair cells), Green: CX3CR1-GFP (macrophages), Magenta: thy-1 (neurons). B. Kanamycin-treated organotypic cultures with internalization of hair cell debris. Red: FM464 (hair cells), Green: CX3CR1-GFP (macrophages). C. Fixed whole organ preparation: 48 hours after kanamycin, hair cells are mostly absent, and hair cell debris is visible within the phagosomes of macrophages. Red: FM464 (hair cells), Green: CX3CR1-GFP (macrophages). Scale bar: 50μm.

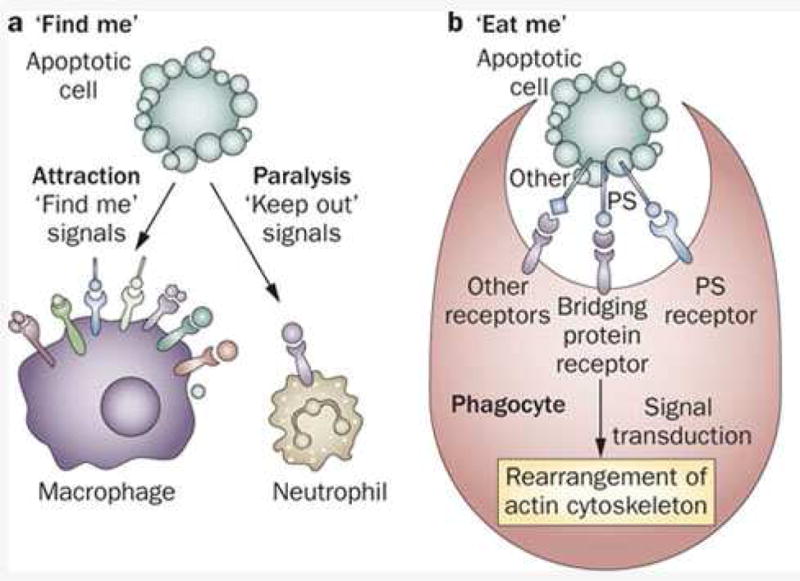

The ligands that signal macrophages to investigate an injured cell have been described as “find me” cues and those that prompt ingestion and phagocytosis as “eat me” cues. While these ligands and receptors have been carefully characterized for tissue macrophages and organs outside of the cochlea, the specific signals that summon cochlear macrophages to injured hair cells are not currently known. Typically, ligands exposed on the surface of distressed cells include externalized phosphatidyl serine, low density lipoprotein, annexin 1, C1q and C3b (complement), ICAM3, thrombospondin 1 (Fadok et al., 1998; Fadok et al., 2000; Fadok et al., 2001; Hoffmann et al., 2001; Ogden et al., 2001; Vandivier et al., 2002; Grimsley and Ravichandran, 2003; Ravichandran, 2003; Krispin et al., 2006; Ravichandran and Lorenz, 2007; Areschoug and Gordon, 2009). Receptors on the surface of macrophages that detect these “eat me” cues include the scavenger receptors, complement receptor, CD14, phosphatidyl serine receptor among others (see Figure 6). CD36 is the cardinal scavenger receptor of the SRB family that binds thrombospondin (Fadok et al., 1998; Silverstein and Febbraio, 2009).

Figure 6.

Dying cells exhibit surface molecules that are identified as “find me” cues and summon macrophages to target these damaged cells. Other leukocytes, such as neutrophils are repelled from these dying cells in order to limit resultant inflammation and adjacent injury. Other molecules then signal to the macrophage that the cell is suitable for digestion by exhibiting “eat me” cues. From (Munoz et al., 2010).

We have included two videos of time lapse experiments which demonstrate organotypic cochlear cultures, one of a control mouse explanted at P3 (supplement, video 1), and another treated with kanamycin (supplement, video 2). These experiments permit examination of the activity of live macrophages in the presence of degenerating hair cells. Cochlear tissues were harvested from CX3CR1-GFP knock in mice in which GFP is endogenously expressed by microglia, macrophages and monocytes (Jung et al., 2000). We found that in control cochleae, macrophages constantly extended processes into the surrounding environment, while the cell body maintained its location in the control mouse cochlear culture for the duration of the time lapse experiment (6 hours). In contrast, when treated with 1 mM kanamycin, hair cell degeneration was evident by 12–18 hours after addition of kanamycin, and macrophages avidly moved towards the sensory epithelium to ingest damaged hair cells and hair cell debris. Hair cells were contacted by macrophage processes shaped like cups, sometimes multiple times by the same macrophage before the cytoplasm fragmented and became internalized by the macrophage. Some macrophages were positioned directly on the apical surface of the sensory epithelium. Others remained positioned in the osseous spiral lamina and extended processes alongside the peripheral axons towards the hair cells; some macrophages extended multiple processes through the habenula and into the sensory epithelium. When compared to the macrophage in Figure 3, it appears that what we observe in vitro may replicate a similar process in vivo, although it is less common to observe macrophages at the habenula with processes extending to the sensory epithelium when hair cells are ablated in vivo. The act of macrophage process extension and retraction can be very rapid; during the course of a time lapse experiment, a process can appear and be lost during the interval between two frames (3 minutes).

We investigated the role of CD36 in cochlear macrophages to determine if this scavenger receptor played an important role in phagocytosis as has been shown in clearance of debris from other tissues. CD36 null mice were used to study phagocytosis in cochlear organotypic cultures and for in vivo studies using aminoglycoside antibiotics to ablate hair cells. We discovered that in vitro, cochlear macrophages that lack CD36 have no deficit in cell movement, displacement, or speed. We designated macrophages as “movers” or “shakers” depending on whether they remained stationary with processes extending in all directions away from the cell body (“shaker”) or if they moved a distance that was larger than one cell soma (“mover”) and we manually counted the numbers of movers and shakers in CD36 wild type and CD36 knockout organ cultures. We found that there was no deficit in the numbers of “movers” in the CD36 null cochleae. There were slightly more macrophages in the CD36 KO cochleae and there were slightly more “movers” in the knockout mice although these differences did not reach statistical significance (Figure 4E). There were no deficits noted in debris clearance when hair cells were ablated with aminoglycosides either in vivo or in vitro.

In the case of hair cell injury, the specific cues that serve as “find me/eat me” cues are not known, but likely involve some of the signals previously identified as important signals for macrophages in other tissues. CD36 null mice were studied both in live organotypic cultures and in fixed tissue explants, and were found to have no deficits in macrophage movement, process extension, or debris clearance. We calculated cell velocity, total displacement, skeletal length, and counted the number of times that cells extended processes to surround or ingest hair cell material. We found that the average speed, total displacement, number of extensions and number of macrophages were not different when we compared CD36 null mice to wild type mice.

Images from CD36 wild type and null organotypic cultures are shown in Figure 5, where panel A shows a control culture and panel B shows another one at 8 hours after treatment with kanamycin. Panel C was acquired 48 hours after kanamycin exposure, when internalized hair cell debris labeled with FM4-64 was observed in the phagosomes of cochlear macrophages. Thus, CD36 seems not to be essential for debris clearance by cochlear macrophages, and we continue to search for important signals that trigger the innate immune cells to find their phagocytic targets.

Macrophage response to hair cell injury in mammalian vestibular organs

Like the cochlea, the vestibular organs possess a resident macrophage population, which normally resides in the stromal tissues of the cristae and otolithic maculae. Macrophages are rarely observed in the normal sensory epithelium, but hair cell injury causes macrophages to migrate into the sensory region, where they actively ingest hair cell debris. Macrophage activity in the injured utricle has been studied in vivo with a transgenic mouse model in which hair cells express the human form of the diphtheria toxin receptor (described in Golub et al., 2012; Tong et al., 2015). In these Pou4f3-huDTR mice, a single injection of diphtheria toxin leads to the death of ~70% of hair cells in the utricle (Kaur et al., 2015a). Macrophages appear to enter the sensory epithelium by rising up through the stromal layer towards the apical surface. The number of macrophages within the injured sensory epithelium peaks at 14 days after DT treatment. Macrophage numbers are elevated in damaged ears of CX3CR1 knockout mice, as in damaged CX3CR1 wild type mice, suggesting that fractalkine receptor is not necessary for vestibular macrophages to find their targets (Kaur et al., 2015a). The vestibular organs of mammals possess a limited ability to regenerate hair cells (Forge et al., 1993; Warchol et al., 1993), and a role for macrophages in regeneration has been proposed. However, whether macrophages contribute to hair cell proliferation or differentiation is not currently known.

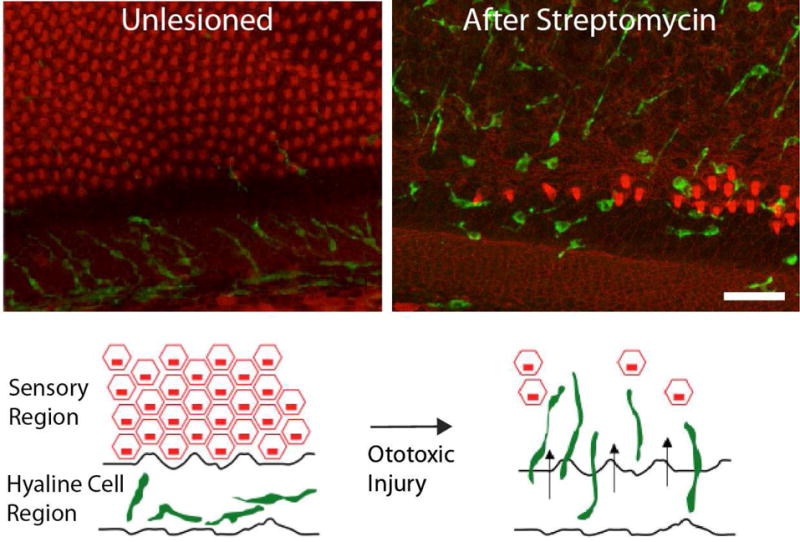

Macrophage Response to Injury in the Avian Inner Ear

The hearing organ of birds, known as the basilar papilla, shares many similarities with the mammalian cochlea. The basilar papilla is tonotopically organized with hair cells that are located on a basilar membrane and mechanically stimulated by a propagated traveling wave. Hair cells of the basilar papilla can be eliminated by acoustic trauma or by treatment with aminoglycoside antibiotics (Rubel and Ryals, 1982; Cruz et al., 1987; Corwin and Cotanche, 1988). Like the mammalian cochlea, the basilar papilla contains resident tissue macrophages, which are distributed throughout the sensory organ and are attracted to sites of hair cell injury (Warchol, 1997; Bhave et al., 1998). Macrophages are concentrated in the hyaline/cuboidal cell region of the papilla, which runs along the inferior boundary of the sensory epithelium (Warchol, 1997; Warchol et al., 2012).

Hair cell injury causes these macrophages to migrate toward the sensory region (Figure 7), but they remain below the basilar membrane. The role of these macrophages is unclear. Most apoptotic hair cells are extruded from the injured basilar papilla. A limited amount of cellular debris remains within the sensory epithelium and is likely removed by nearby supporting cells. It is possible that macrophages situated below the basilar membrane extend processes into the sensory epithelium and remove some remnants of apoptotic hair cells. It has further been suggested that macrophages may play a stimulatory role in hair cell regeneration in the avian ear (Warchol, 1997; Bhave et al., 1998; Warchol, 1999). However, selective ablation of macrophages with clodronate-containing liposomes caused no deficit in debris clearance, hair cell recovery or regeneration in organotypic cultures of the basilar papilla. The only apparent consequence of macrophage depletion was a reduction in the proliferation of tympanic border mesothelial cells associated with the basilar membrane (Warchol et al., 2012). This finding suggests that macrophages might be involved in the maintenance of the basilar membrane through support of the tympanic border cells. Additionally, in mice, the tympanic border cells have been proposed as potential precursors for regenerated hair cells (Jan et al., 2013). Therefore, there is a possibility that macrophages indirectly affect the potential for regeneration by interaction with tympanic border cells.

Figure 7.

Macrophage response to hair cell injury in the chick basilar papilla. A sizable population of macrophages resides in the hyaline/cuboidal cell region of the papilla, which adjoins the inferior (abneural) border of the sensory epithelium (left). Hair cell injury leads to an apparent redistribution of these macrophages, which migrate toward the sensory region (right). Such macrophages remain below the basilar membrane and are normally not observed within the sensory epithelium. Labels: Green: KUL01 (macrophages); red: phalloidin (f-actin). Modified from: ME Warchol, RA Schwendener, K Hirose, PLoS One: 7(12): e51574 (2012).

Macrophage Interactions with the Zebrafish Lateral Line

Hair cell-containing sensory organs are found on the external surfaces of fish and amphibians, where they detect fluid motion near the animal’s body. Such sensory organs are known as neuromasts and typically contain 10–20 hair cells. Neuromasts are arranged into precisely organized networks on the animal’s head (‘anterior lateral line’), or along the animal’s tail (‘posterior lateral line’). Pioneering studies of Jones and Corwin (Jones and Corwin, 1993, 1996) used time-lapse video microscopy to characterize the cellular events that occur in the tail regions of axolotl salamanders after ablation of lateral line hair cells. Macrophages and neutrophils, identified by specific markers, were quickly recruited to lesioned neuromasts. There, they phagocytosed hair cell debris and established transient contacts with surrounding supporting cells. Such activities were suggestive of a role in stimulating regeneration.

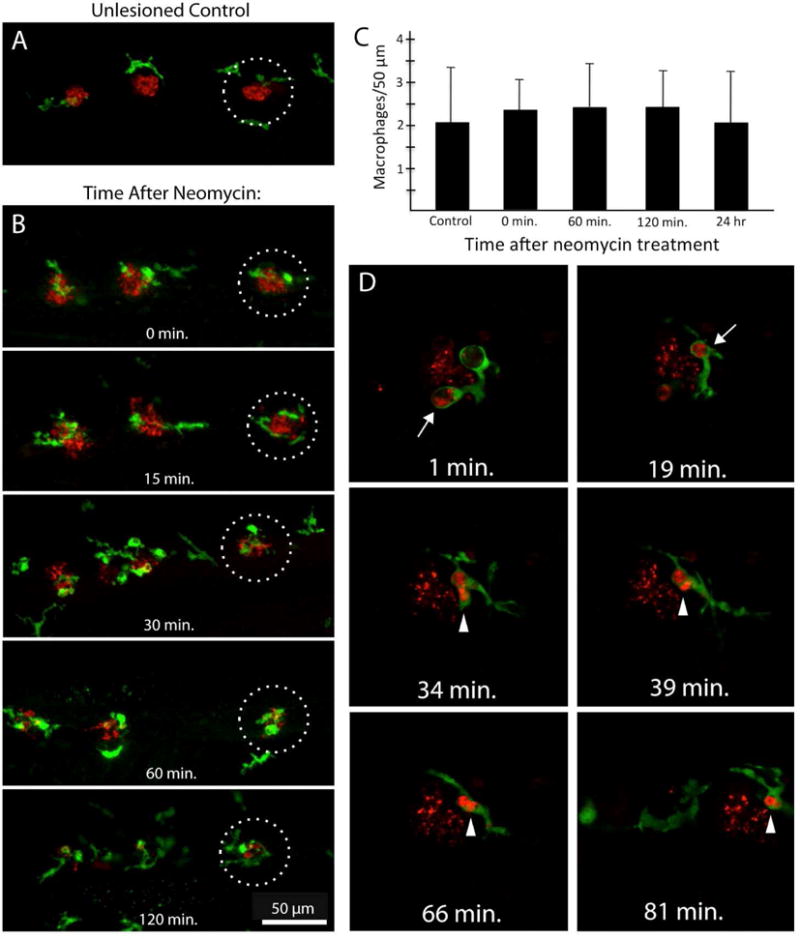

In the past decade, the zebrafish lateral line has emerged as a widely-studied model of hair cell development, pathology, and regeneration. Like their counterparts in the inner ear, hair cells in the lateral line can be selectively killed by exposure to aminoglycoside antibiotics or the antitumor agent cisplatin (Williams and Holder, 2000; Harris et al., 2003; Ou et al., 2007). The optical clarity of larval zebrafish permits direct visualization of the cellular events that occur during hair cell death and regeneration. Also, transgenic fish that express fluorescent proteins in selected cell populations have become commonly available. We have used such methods to characterize the behavior of macrophages in response to ototoxic injury of lateral line hair cells. Our studies utilize the Tg(mpeg1:YFP) fish line, which express YFP in all macrophages and microglia (Ellett et al., 2011). Use of this transgenic line allows us to identify and count macrophages associated with normal and damaged neuromasts. We have focused on hair cell injury and macrophage response in the three most-distal neuromasts of the posterior lateral line (P9-11, see (Raible and Kruse, 2000), using fish at 7 days post-fertilization (dpf)).

Quantitative observations indicate that uninjured neuromasts of the posterior lateral line normally possess ~2 macrophages within a 25 μm radius (Fig. 8A,C). Such macrophages often extend thin processes into neuromasts, suggesting that they are constantly monitoring the status of hair cells and supporting cells. Hair cell injury causes these macrophages to enter neuromasts (Fig. 8B), and time-lapse microscopy confirms that these macrophages are actively involved in the clearance of dying cells (Fig. 8D). Ototoxic hair cell death in zebrafish occurs quickly – treatment with neomycin is sufficient to kill most lateral line hair cells within thirty minutes (Harris et al., 2003), and nearby macrophages respond equally rapidly. A very similar macrophage response has recently been described following hair cell injury in a more anterior neuromast (L1) following CuSO4 exposure (Carrillo et al., 2016). Surprisingly, the number of macrophages associated with neomycin-lesioned neuromasts is not significantly enhanced by hair cell injury (Fig. 8C). Phagocytosis of hair cell debris is carried out by nearby macrophages and does not require recruitment of additional macrophages from distant locations. Lateral line neuromasts may also utilize other methods for disposing of hair cell debris (e.g., extrusion out of the sensory epithelium or phagocytosis by supporting cells).

Figure 8.

Macrophage activity in response to hair cell injury in lateral line neuromasts of larval zebrafish. A: Macrophages (green, YFP) are present in the near vicinity of uninjured neuromasts. Image shows the distal-most neuromasts (P9-11) of the posterior lateral line of a 7 dpf zebrafish. Red: HCS-1 immunoreactivity (hair cells). B: Neomycin-induced hair cell death causes nearby macrophages to enter the injured neuromasts. Note that the number of macrophages near each neuromasts appears nearly unchanged. C: Quantification of macrophages located near lateral line neuromasts at various time points after ototoxic injury. Fish were incubated for 30 min in 50 μM neomycin and then fixed at 0, 1, 2 or 24 hr recovery. Following fixation and immunoprocessing, the number of YFP-labeled macrophages within a 25μm radius of neuromasts P9, P10 and P11 was quantified. The numbers of macrophages associated with the lesioned neuromasts were relatively constant at all recovery times and also unchanged from the numbers near unlesioned (control) fish (n=10 fish/time point; mean±SD). D: Time-lapse imaging reveals macrophage phagocytosis of dying hair cells. Hair cells were loaded with FM464 (red) and zebrafish were incubated in neomycin. Fish were then anesthetized and imaged by time-lapse microscopy. Time stamps on each image refer to elapsed time after initiation of time-lapse recording. At early times (1 min, 19 min), cup-shaped macrophage phagosomes were observed in contact with hair cell debris (arrows, red). Such debris was then internalized and consolidated within the macrophage cytoplasm (arrowheads, red). Such observations confirm that macrophages actively participate in the removal of dying hair cells in zebrafish.

Studies of tissue injury in zebrafish suggest a number of candidate signals that may serve as chemotactic factors, including H2O2, ATP and various chemokines (Enyedi and Niethammer, 2013). In addition, recent data implicate the release of heat shock protein 60 (HSP60) as promoting the migration of macrophages toward injured neuromasts (Pei et al., 2016). HSP60 normally regulates protein folding in mitochondria, but is also released into the extracellular space after tissue injury, and can interact with the CD36 receptor on macrophages. Genetic deletion of HSP60 in zebrafish reduces leukocyte recruitment to injured neuromasts and also impairs regeneration. The actions of HSP60 appear complex, involving both macrophages and neutrophils, and it is possible that additional chemoattractants also participate in this recruitment and repair process. The accessibility and optical properties of neuromasts, combined with the ease of use of small molecule inhibitors and genetic manipulation, make the zebrafish lateral line an advantageous system in which to study signaling between hair cells and macrophages.

Phagocytosis by Amateurs: Response of Supporting Cells

Phagocytosis by supporting cells in the mammalian inner ear

As noted above, the death of a hair cell triggers a rapid and coordinated response from its surrounding supporting cells, in order to repair the lumen of the sensory epithelium (Li et al., 1995). Such sites of epithelial resealing are often referred to as ‘scars’ (Raphael and Altschuler, 1991; Forge et al., 1998). This repair process is a general property of epithelial cells and is observed in numerous organs and species, ranging from drosophila to mammals (Gudipaty and Rosenblatt, 2016). However, in addition to repairing the epithelial barrier, inner ear supporting cells can also serve as ‘amateur’ phagocytes, and often play a critical role in the removal of cellular debris. Time-lapse imaging studies of the injured mouse utricle demonstrate that hair cell death leads to the formation of a phagosome by surrounding supporting cells (Monzack et al., 2015). Supporting cells that surround a dying hair cell quickly assemble a cup-shaped, actin structure that pushes the apical portion of the hair cell towards the luminal surface of the epithelium, and then encloses the remaining basal portion and pushes it toward the basement membrane. Assembly of this structure begins once the dying hair cell loses membrane integrity. A subject of continued interest is to identify the signals that initiate the formation of this phagocytic structure.

Supporting cells in the mammalian cochlea can also engulf apoptotic hair cells. Cochlear outer hair cells contain high amounts of prestin, a protein that mediates electromotility and enhances hearing sensitivity (Dallos and Fakler, 2002). In the normal cochlea, immunoreactivity for prestin is limited to outer hair cells. However, immunolabeling of cochleae after noise exposure or ototoxic injury reveals patches of prestin within the remaining supporting cells (Abrashkin et al., 2006). Such obervations are strong evidence that the supporting cells that adjoin outer hair cells can engulf debris that results from cell death. Additional studies, employing serial block face scanning electron microscopy, have revealed this process in more detail (Anttonen et al., 2014). Hair cell injury induced by ototoxic antibiotics results in shrinkage of the outer hair cells with concurrent expansion of the Deiters cell phalangeal processes. These swollen processes occupy the space formerly occupied by the outer hair cell, and appear to ‘push’ the disintegrating outer hair cells below the surface of the reticular lamina. Supporting cells also form “actin belts” around the dying hair cell, which may mediate subsequent elimination of cellular debris. The apical portion of the hair cell can be extruded into the endolymph, while the basal portion of the hair cell undergoes shrinkage, condensation, and fragmentation of the nucleus. While this process promotes the closing of the reticular lamina and containment of the dying hair cell to the perilymph compartment, it may also involve phagocytosis.

Extrusion of Dying Hair Cells from the Avian Basilar Papilla

The clearance of apoptotic hair cells from the basilar papilla occurs primarily via extrusion, a cellular process of debris clearance that is common in other types of epithelial cells (Rosenblatt et al., 2001). After noise or ototoxic exposure, the apical surfaces of injured hair cells begin to shrink, while the surfaces of surrounding supporting cells undergo a corresponding expansion. As a hair cell’s apical surface becomes progressively smaller, it also balloons outward from the lumen, culminating in the dying hair cell being completely ejected from the epithelium (Cotanche and Dopyera, 1990; Hirose et al., 2004; Mangiardi et al., 2004). These extruded hair cells appear largely intact, although many of them possess morphological features that are suggestive of apoptosis. Extruded cells initially occupy the space between the sensory epithelium and the tectorial membrane, and it is not clear how they are ultimately removed from endolymph.

Engulfment of Apoptotic Cells in the Avian Vestibular Organs

Debris clearance in the avian vestibular epithelia differs from that observed in the basilar papilla. Rather than being extruded intact from the sensory epithelium, dying hair cells are eliminated via a two-step mechanism that involves the extrusion of the apical portion of the hair cell, followed by the phagocytosis of the remaining basal portion of the hair cell (Bird et al., 2010). In essence, this process is similar to that which occurs in the vestibular organs of mammals (Monzack et al., 2015). The supporting cells that surround a dying hair cell first enlarge their apical surfaces, causing the upper portion of the hair cell, including the stereocilia bundle and cuticular plate to be pinched between adjacent supporting cells and then ejected from the epithelium. After several hours, these supporting cells coordinate to form a cup-shaped actin basket within the epithelium, which then constricts around the basal portion of the dying cell. Hair cell membrane integrity is lost shortly after this consumptive process begins, suggesting that engulfment may be critical for the progression of apoptosis of the basal portion of the hair cell. Notably, the ultimate fate of the basally-located debris is not clear. It could be processed by lysosomes contained within the supporting cells or transferred to recruited macrophages. Prior studies have shown that the avian vestibular organs contain resident macrophages and that their numbers are increased after ototoxic hair cell injury (Bhave et al., 1998; Warchol, 1999; O’Halloran and Oesterle, 2004; Bird et al., 2010).

Conclusions

Hair cell death triggers various processes for cell removal, which can involve both supporting cells and macrophages. These two major players in the maintenance of the sensory epithelium likely serve overlapping roles, such that inhibition of activity of one cell type leads to compensation by the other. The specific role of tissue macrophages in cochlear homeostasis, cell clearance, and phagocytosis, as well as their role in antigen presentation and induction of adaptive immunity are still under investigation. What is clear is that the population of macrophages in the inner ear is dynamic and highly inducible. Despite anatomical compartmentalization of the sensory cells, macrophages are sensitive to cues provided by the hair cells when they are in distress. In both in vitro and in vivo studies, macrophages are observed interacting with damaged hair cells and positioning themselves such that they gain access to the sensory epithelium. Morphologic changes associated with hair cell death have been characterized extensively. We are now learning how these changes are influenced by supporting cells and macrophages, both of which are invested with the task of making sure that dying hair cells find an orderly exit from the sensory epithelium.

Methods

Original data presented in this review were obtained using the following protocols. All animal protocols were approved by the IACUC at Washington University School of Medicine.

Mouse Studies

Animals

CD36 knockout mice (CD36−/−) were bred with CX3CR1-GFP mice such that all macrophages, monocytes, and microglia were endogenously green in the CD36 null mice. CD36−/− CX3CR1+/GFP mice were used for these experiments and CD36+/+ CX3CR1+/GFP mice served as controls. CD36 mice were kindly provided by Maria Febbraio, Cleveland Clinic, and CX3CR1 mice were provided by Dan Littman, NYU. Thy-1 YFP mice exhibiting fluorescently labeled neurons were created by Joshua Sanes and acquired through Washington University School of Medicine.

Aminoglycoside and CD36 null mice

CD36−/− mice were assigned to receive kanamycin (900mg/kg) and furosemide, or saline. CD36 WT mice were also randomly assigned to kanamycin/furosemide or saline with 10–15 mice per group. ABR, plastic sectioning, and immunohistochemistry were completed to assess the difference in outcome. CD36 antibody staining was performed with anti-mouse CD36 IgA (BD 552544 used at 1:100, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and Texas Red conjugated goat anti-mouse IgA (SC3693, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas TX).

Tissue Culture

Wild-type and CD36 knockout mice with fluorescent green macrophages were used for cochlear organ cultures. Organ cultures were placed in culture medium, following methods outlined in (Richardson and Russell, 1991). Briefly, neonatal (P2-P5) mice of each genotype were euthanized and the bony labyrinth was harvested. The otic capsule and lateral wall were removed, and the sensory epithelium and spiral ganglion cells were separated into segments of approximately 90 degree turns and placed in culture. Cochlear organotypic cultures were maintained in DMEM/F12 supplemented with ampicillin, 0.1% fetal bovine serum, and N2 (tissue culture medium supplement) and were grown on laminin-coated sterile chambered coverslips (Bottenstein and Sato, 1979). After 24 hours, organ cultures were treated with control reagent (media) or 1 mM kanamycin for 16 hours, resulting in extensive hair cell damage. The explants were then loaded with FM464, which labeled the inner and outer hair cells. Live time-lapse imaging was performed for the next 8 hours.

Time-Lapse Confocal Imaging

Images were acquired by confocal microscopy (Zeiss LSM700) while housing the cochlear culture on a warmed, humidified chamber with CO2 supplementation. Image stacks were acquired every 8–10 minutes for 4 hours (40–50 focal planes per maximum-intensity projection). Maximum-intensity projections were saved from each image stack and then made into movies.

Macrophage Movement Analysis

Raw images from Zen imaging software (Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) were uploaded to Volocity (PerkinElmer, Waltham MA) and analyzed for static and dynamic measurements including cell volume, skeletal length, displacement, and cell velocity. Movies were reviewed, and cells were categorized individually as “eaters” if they phagocytosed FM464-labeled hair cells. Moreover, cells were categorized as “movers” if they displaced by a distance equal to the diameter of one cell soma or greater during the course of the movie, or “shakers” if they extended processes but did not move from their original position. CD36KO macrophages were compared with CD36WT mice. All cultures were taken from mice with endogenously fluoresecent macrophages and monocytes (CX3CR1+/GFP background) using both subjective assessments (eaters, movers, shakers) and objective measurements (displacement, volocity, volume, length).

Zebrafish Studies

Macrophage response to hair cell injury in zebrafish lateral line neuromasts was characterized using the Tg (Mpeg1:YFP) transgenic zebrafish strain, which expresses YFP in all macrophages and microglia (Ellett et al., 2011). Fish were bred in the Zebrafish Core Facility of Washington University School of Medicine, maintained at 28.5° C in ‘egg water’ (Westerfield, 2000). Experiments were initiated when fish were 7 days post-fertilization (dpf). Lateral line hair cells were lesioned by incubation for 30 minutes in 50 μM neomycin. Fish were then rinsed 3x in fresh egg water and allowed to survive for 30–120 minutes. At that point, fish were euthanized by immersion in tricane and fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4° C. Immunolabeling was carried out following methods described in Ma et al., (2008). Hair cells were labeled using the HCS-1 antibody (Goodyear et al., 2010) and the fluorescent signal from macrophages was enhanced via an antibody against GFP (which recognizes a epitope common to both GFP and YFP). Fish were mounted on microscope slides in glycerol:PBS. Images were obtained on a Zeiss LSM700 confocal microscope and processed with Volocity software.

Interactions between macrophages and lateral line hair cells in living fish were examined using time-lapse video microscopy. Zebrafish (age: 7 dpf) were first incubated for 120 seconds in FM464 (3 μM; Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) in order to label hair cells. The animals were then anesthetized in 50 μg/ml tricane and placed in a glass coverslip culture well (MatTek, Ashland, MA), in a drop of 1.5% low melting point agarose). Once the agarose had solidified, the embedded fish were covered in 1–2 ml of egg water that contained 50 μg/ml tricane. MatTek dishes containing 5–8 immobilized fish were placed in a heated stage on a Zeiss LSM700 inverted confocal microscope. Fish were maintained at 28.5° C and confocal images were collected (7–8 image planes per stack) at 120 sec intervals for 2–4 hours.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Resident macrophages are present in the inner ear.

Cochlear mononuclear phagocytes have a normal turnover rate unlike microglia, which are terminally differentiated and are not replaced by bone marrow precursors.

Damage to the inner ear induces migration of macrophages from the circulation into the mammalian cochlea.

Vestibular organs also possess a population of resident macrophages.

Active phagocytosis of dying and damaged hair cells by macrophages are observed.

Supporting cells also play an important role in clearance of hair cells through extrusion, filling the spaces that hair cells vacate and in some cases, disposing of hair cell remnants.

Acknowledgments

We thank Lalita Ramakrishnan and Graham Lieschke for providing Tg(mpeg1:YFP) zebrafish.

Supported by grants R01DC011315 (KH) and R01DC006283 (MEW). Work on zebrafish was initiated with the assistance of David W. Raible and Edwin W Rubel (University of Washington) and was partially supported by a Bloedel Traveling Scholar Fellowship to MEW.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Literature Cited

- Abrashkin KA, Izumikawa M, Miyazawa T, Wang CH, Crumling MA, Swiderski DL, Beyer LA, Gong TW, Raphael Y. The fate of outer hair cells after acoustic or ototoxic insults. Hearing research. 2006;218:20–29. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2006.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajami B, Bennett JL, Krieger C, Tetzlaff W, Rossi FM. Local self-renewal can sustain CNS microglia maintenance and function throughout adult life. Nat Neurosci. 2007;10:1538–1543. doi: 10.1038/nn2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anttonen T, Belevich I, Kirjavainen A, Laos M, Brakebusch C, Jokitalo E, Pirvola U. How to bury the dead: elimination of apoptotic hair cells from the hearing organ of the mouse. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2014;15:975–992. doi: 10.1007/s10162-014-0480-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Areschoug T, Gordon S. Scavenger receptors: role in innate immunity and microbial pathogenesis. Cellular microbiology. 2009;11:1160–1169. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2009.01326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Auffray C, Fogg D, Garfa M, Elain G, Join-Lambert O, Kayal S, Sarnacki S, Cumano A, Lauvau G, Geissmann F. Monitoring of blood vessels and tissues by a population of monocytes with patrolling behavior. Science. 2007;317:666–670. doi: 10.1126/science.1142883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhave SA, Oesterle EC, Coltrera MD. Macrophage and microglia-like cells in the avian inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398:241–256. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-9861(19980824)398:2<241::aid-cne6>3.0.co;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bird JE, Daudet N, Warchol ME, Gale JE. Supporting cells eliminate dying sensory hair cells to maintain epithelial integrity in the avian inner ear. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2010;30:12545–12556. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3042-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bottenstein JE, Sato GH. Growth of a rat neuroblastoma cell line in serum-free supplemented medium. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1979;76:514–517. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.1.514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo SA, Anguita-Salinas C, Pena OA, Morales RA, Munoz-Sanchez S, Munoz-Montecinos C, Paredes-Zuniga S, Tapia K, Allende ML. Macrophage Recruitment Contributes to Regeneration of Mechanosensory Hair Cells in the Zebrafish Lateral Line. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 2016;117:1880–1889. doi: 10.1002/jcb.25487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corwin JT, Cotanche DA. Regeneration of sensory hair cells after acoustic trauma. Science. 1988;240:1772–1774. doi: 10.1126/science.3381100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotanche DA, Dopyera CE. Hair cell and supporting cell response to acoustic trauma in the chick cochlea. Hearing research. 1990;46:29–40. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(90)90137-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruz RM, Lambert PR, Rubel EW. Light microscopic evidence of hair cell regeneration after gentamicin toxicity in chick cochlea. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;113:1058–1062. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1987.01860100036017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellett F, Pase L, Hayman JW, Andrianopoulos A, Lieschke GJ. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood. 2011;117:e49–56. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-10-314120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enyedi B, Niethammer P. H2O2: a chemoattractant? Methods Enzymol. 2013;528:237–255. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-405881-1.00014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Warner ML, Bratton DL, Henson PM. CD36 is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by human macrophages that use either a phosphatidylserine receptor or the vitronectin receptor (alpha v beta 3) Journal of immunology. 1998;161:6250–6257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, de Cathelineau A, Daleke DL, Henson PM, Bratton DL. Loss of phospholipid asymmetry and surface exposure of phosphatidylserine is required for phagocytosis of apoptotic cells by macrophages and fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1071–1077. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003649200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Bratton DL, Rose DM, Pearson A, Ezekewitz RA, Henson PM. A receptor for phosphatidylserine-specific clearance of apoptotic cells. Nature. 2000;405:85–90. doi: 10.1038/35011084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Li L, Nevill G. Hair cell recovery in the vestibular sensory epithelia of mature guinea pigs. J Comp Neurol. 1998;397:69–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forge A, Li L, Corwin JT, Nevill G. Ultrastructural evidence for hair cell regeneration in the mammalian inner ear. Science. 1993;259:1616–1619. doi: 10.1126/science.8456284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fredelius L, Rask-Andersen H. The role of macrophages in the disposal of degeneration products within the organ of corti after acoustic overstimulation. Acta oto-laryngologica. 1990;109:76–82. doi: 10.3109/00016489009107417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Jung S, Littman DR. Blood monocytes consist of two principal subsets with distinct migratory properties. Immunity. 2003;19:71–82. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(03)00174-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geissmann F, Manz MG, Jung S, Sieweke MH, Merad M, Ley K. Development of monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. Science. 2010;327:656–661. doi: 10.1126/science.1178331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Guilliams M. Tissue-Resident Macrophage Ontogeny and Homeostasis. Immunity. 2016;44:439–449. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ginhoux F, Greter M, Leboeuf M, Nandi S, See P, Gokhan S, Mehler MF, Conway SJ, Ng LG, Stanley ER, Samokhvalov IM, Merad M. Fate mapping analysis reveals that adult microglia derive from primitive macrophages. Science. 2010;330:841–845. doi: 10.1126/science.1194637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golub JS, Tong L, Ngyuen TB, Hume CR, Palmiter RD, Rubel EW, Stone JS. Hair cell replacement in adult mouse utricles after targeted ablation of hair cells with diphtheria toxin. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2012;32:15093–15105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1709-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodyear RJ, Legan PK, Christiansen JR, Xia B, Korchagina J, Gale JE, Warchol ME, Corwin JT, Richardson GP. Identification of the hair cell soma-1 antigen, HCS-1, as otoferlin. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2010;11:573–586. doi: 10.1007/s10162-010-0231-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimsley C, Ravichandran KS. Cues for apoptotic cell engulfment: eat-me, don’t eat-me and come-get-me signals. Trends Cell Biol. 2003;13:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gudipaty SA, Rosenblatt J. Epithelial cell extrusion: Pathways and pathologies. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2016.05.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris JA, Cheng AG, Cunningham LL, MacDonald G, Raible DW, Rubel EW. Neomycin-induced hair cell death and rapid regeneration in the lateral line of zebrafish (Danio rerio) Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2003;4:219–234. doi: 10.1007/s10162-002-3022-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Sato E. Comparative analysis of combination kanamycin-furosemide versus kanamycin alone in the mouse cochlea. Hearing research. 2011;272:108–116. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2010.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Westrum LE, Cunningham DE, Rubel EW. Electron microscopy of degenerative changes in the chick basilar papilla after gentamicin exposure. J Comp Neurol. 2004;470:164–180. doi: 10.1002/cne.11046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Discolo CM, Keasler JR, Ransohoff R. Mononuclear phagocytes migrate into the murine cochlea after acoustic trauma. J Comp Neurol. 2005;489:180–194. doi: 10.1002/cne.20619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Li SZ, Ohlemiller KK, Ransohoff RM. Systemic lipopolysaccharide induces cochlear inflammation and exacerbates the synergistic ototoxicity of kanamycin and furosemide. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2014a;15:555–570. doi: 10.1007/s10162-014-0458-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirose K, Hartsock JJ, Johnson S, Santi P, Salt AN. Systemic lipopolysaccharide compromises the blood-labyrinth barrier and increases entry of serum fluorescein into the perilymph. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2014b;15:707–719. doi: 10.1007/s10162-014-0476-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoeffel G, Ginhoux F. Ontogeny of Tissue-Resident Macrophages. Front Immunol. 2015;6:486. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00486. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann PR, deCathelineau AM, Ogden CA, Leverrier Y, Bratton DL, Daleke DL, Ridley AJ, Fadok VA, Henson PM. Phosphatidylserine (PS) induces PS receptor-mediated macropinocytosis and promotes clearance of apoptotic cells. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:649–659. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200108080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jan TA, Chai R, Sayyid ZN, van Amerongen R, Xia A, Wang T, Sinkkonen ST, Zeng YA, Levin JR, Heller S, Nusse R, Cheng AG. Tympanic border cells are Wnt-responsive and can act as progenitors for postnatal mouse cochlear cells. Development. 2013;140:1196–1206. doi: 10.1242/dev.087528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JE, Corwin JT. Replacement of lateral line sensory organs during tail regeneration in salamanders: identification of progenitor cells and analysis of leukocyte activity. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1993;13:1022–1034. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.13-03-01022.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones JE, Corwin JT. Regeneration of sensory cells after laser ablation in the lateral line system: hair cell lineage and macrophage behavior revealed by time-lapse video microscopy. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:649–662. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-02-00649.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung S, Aliberti J, Graemmel P, Sunshine MJ, Kreutzberg GW, Sher A, Littman DR. Analysis of fractalkine receptor CX(3)CR1 function by targeted deletion and green fluorescent protein reporter gene insertion. Mol Cell Biol. 2000;20:4106–4114. doi: 10.1128/mcb.20.11.4106-4114.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Hirose K, Rubel EW, Warchol ME. Macrophage recruitment and epithelial repair following hair cell injury in the mouse utricle. Front Cell Neurosci. 2015a;9:150. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2015.00150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur T, Zamani D, Tong L, Rubel EW, Ohlemiller KK, Hirose K, Warchol ME. Fractalkine Signaling Regulates Macrophage Recruitment into the Cochlea and Promotes the Survival of Spiral Ganglion Neurons after Selective Hair Cell Lesion. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015b;35:15050–15061. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2325-15.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krispin A, Bledi Y, Atallah M, Trahtemberg U, Verbovetski I, Nahari E, Zelig O, Linial M, Mevorach D. Apoptotic cell thrombospondin-1 and heparin-binding domain lead to dendritic-cell phagocytic and tolerizing states. Blood. 2006;108:3580–3589. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-03-013334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Nevill G, Forge A. Two modes of hair cell loss from the vestibular sensory epithelia of the guinea pig inner ear. J Comp Neurol. 1995;355:405–417. doi: 10.1002/cne.903550307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma EY, Rubel EW, Raible DW. Notch signaling regulates the extent of hair cell regeneration in the zebrafish lateral line. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2008;28:2261–2273. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4372-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mangiardi DA, McLaughlin-Williamson K, May KE, Messana EP, Mountain DC, Cotanche DA. Progression of hair cell ejection and molecular markers of apoptosis in the avian cochlea following gentamicin treatment. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:1–18. doi: 10.1002/cne.20129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monzack EL, May LA, Roy S, Gale JE, Cunningham LL. Live imaging the phagocytic activity of inner ear supporting cells in response to hair cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2015;22:1995–2005. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2015.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munoz LE, Lauber K, Schiller M, Manfredi AA, Herrmann M. The role of defective clearance of apoptotic cells in systemic autoimmunity. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2010;6:280–289. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2010.46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Halloran EK, Oesterle EC. Characterization of leukocyte subtypes in chicken inner ear sensory epithelia. J Comp Neurol. 2004;475:340–360. doi: 10.1002/cne.20162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Malley JT, Nadol JB, Jr, McKenna MJ. Anti CD163+, Iba1+, and CD68+ Cells in the Adult Human Inner Ear: Normal Distribution of an Unappreciated Class of Macrophages/Microglia and Implications for Inflammatory Otopathology in Humans. Otology & neurotology : official publication of the American Otological Society, American Neurotology Society [and] European Academy of Otology and Neurotology. 2016;37:99–108. doi: 10.1097/MAO.0000000000000879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogden CA, deCathelineau A, Hoffmann PR, Bratton D, Ghebrehiwet B, Fadok VA, Henson PM. C1q and mannose binding lectin engagement of cell surface calreticulin and CD91 initiates macropinocytosis and uptake of apoptotic cells. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2001;194:781–795. doi: 10.1084/jem.194.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ou HC, Raible DW, Rubel EW. Cisplatin-induced hair cell loss in zebrafish (Danio rerio) lateral line. Hearing research. 2007;233:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.heares.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pei K, Tanaka K, Huang SC, Xu L, Liu B, Sinclair J, Idol J, Varshney GK, Huang H, Lin S, Nussenblatt RB, Mori R, Burgess SM. Extracellular HSP60 triggers tissue regeneration and wound healing by regulating inflammation and cell proliferation. Regen Med. 2016;1:16013. doi: 10.1038/npjregenmed.2016.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raible DW, Kruse GJ. Organization of the lateral line system in embryonic zebrafish. J Comp Neurol. 2000;421:189–198. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raphael Y, Altschuler RA. Scar formation after drug-induced cochlear insult. Hearing Research. 1991;51:173–183. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90034-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KS. “Recruitment signals” from apoptotic cells: invitation to a quiet meal. Cell. 2003;113:817–820. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00471-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravichandran KS, Lorenz U. Engulfment of apoptotic cells: signals for a good meal. Nature reviews Immunology. 2007;7:964–974. doi: 10.1038/nri2214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson GP, Russell IJ. Cochlear cultures as a model system for studying aminoglycoside induced ototoxicity. Hearing research. 1991;53:293–311. doi: 10.1016/0378-5955(91)90062-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt J, Raff MC, Cramer LP. An epithelial cell destined for apoptosis signals its neighbors to extrude it by an actin- and myosin-dependent mechanism. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1847–1857. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00587-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubel EW, Ryals BM. Patterns of hair cell loss in chick basilar papilla after intense auditory stimulation. Exposure duration and survival time. Acta otolaryngologica. 1982;93:31–41. doi: 10.3109/00016488209130849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato E, Shick HE, Ransohoff RM, Hirose K. Repopulation of cochlear macrophages in murine hematopoietic progenitor cell chimeras: the role of CX3CR1. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506:930–942. doi: 10.1002/cne.21583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato E, Shick HE, Ransohoff RM, Hirose K. Expression of Fractalkine Receptor CX3CR1 on Cochlear Macrophages Influences Survival of Hair Cells Following Ototoxic Injury. J Assoc Res Otolaryngol. 2009 doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0198-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sato E, Shick HE, Ransohoff RM. Hirose K Expression of fractalkine receptor CX3CR1 on cochlear macrophages influences survival of hair cells following ototoxic injury. Journal of the Association for Research in Otolaryngology : JARO. 2010;11:223–234. doi: 10.1007/s10162-009-0198-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savill J, Fadok V. Corpse clearance defines the meaning of cell death. Nature. 2000;407:784–788. doi: 10.1038/35037722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C, Gomez Perdiguero E, Chorro L, Szabo-Rogers H, Cagnard N, Kierdorf K, Prinz M, Wu B, Jacobsen SE, Pollard JW, Frampton J, Liu KJ, Geissmann F. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 2012;336:86–90. doi: 10.1126/science.1219179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein RL, Febbraio M. CD36, a scavenger receptor involved in immunity, metabolism, angiogenesis, and behavior. Sci Signal. 2009;2:re3. doi: 10.1126/scisignal.272re3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan BT, Lee MM, Ruan R. Bone-marrow-derived cells that home to acoustic deafened cochlea preserved their hematopoietic identity. J Comp Neurol. 2008;509:167–179. doi: 10.1002/cne.21729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong L, Strong MK, Kaur T, Juiz JM, Oesterle EC, Hume C, Warchol ME, Palmiter RD, Rubel EW. Selective deletion of cochlear hair cells causes rapid age-dependent changes in spiral ganglion and cochlear nucleus neurons. The Journal of neuroscience: the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2015;35:7878–7891. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2179-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandivier RW, Ogden CA, Fadok VA, Hoffmann PR, Brown KK, Botto M, Walport MJ, Fisher JH, Henson PM, Greene KE. Role of surfactant proteins A, D, and C1q in the clearance of apoptotic cells in vivo and in vitro: calreticulin and CD91 as a common collectin receptor complex. Journal of immunology. 2002;169:3978–3986. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME. Macrophage activity in organ cultures of the avian cochlea: demonstration of a resident population and recruitment to sites of hair cell lesions. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:724–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME. Immune cytokines and dexamethasone influence sensory regeneration in the avian vestibular periphery. J Neurocytol. 1999;28:889–900. doi: 10.1023/a:1007026306730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Schwendener RA, Hirose K. Depletion of resident macrophages does not alter sensory regeneration in the avian cochlea. PloS one. 2012;7:e51574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warchol ME, Lambert PR, Goldstein BJ, Forge A, Corwin J. Regenerative proliferation in inner ear sensory epithelia from adult guinea pigs and humans. Science. 1993;259:1619–1622. doi: 10.1126/science.8456285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westerfield M. The Zebrafish Book. University of Oregon Press; Eugene OR: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Williams JA, Holder N. Cell turnover in neuromasts of zebrafish larvae. Hearing research. 2000;143:171–181. doi: 10.1016/s0378-5955(00)00039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang W, Vethanayagam RR, Dong Y, Cai Q, Hu BH. Activation of the antigen presentation function of mononuclear phagocyte populations associated with the basilar membrane of the cochlea after acoustic overstimulation. Neuroscience. 2015;303:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2015.05.081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Dai M, Fridberger A, Hassan A, Degagne J, Neng L, Zhang F, He W, Ren T, Trune D, Auer M, Shi X. Perivascular-resident macrophage-like melanocytes in the inner ear are essential for the integrity of the intrastrial fluid-blood barrier. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:10388–10393. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205210109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.