Abstract

Background

The experience of children undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), including how different participants (i.e. children, parents, nurses) contribute to an overall picture of a child’s experience, is poorly characterized. We evaluated parent, child and nurse perspectives on the experience of children during HSCT and factors contributing to inter-rater differences.

Methods

Participants were enrolled on a multicenter, prospective study evaluating child and parent health-related quality of life over the year post-HSCT. Children (n=165) and their parent and nurse completed the Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Experiences Scale (BASES) at baseline (before/during conditioning), day+7 (seven days post-stem cell infusion) and day+21. BASES domains include Somatic Distress, Mood Disturbance, Cooperation, and Getting Along. Higher scores indicate more distress/impairment. Repeated measures models by domain assessed differences by raters and change over time, and identified other factors associated with raters’ scores.

Results

Completion rates were high (≥73% across times and raters). Multivariable models revealed significant time-rater interactions, which varied by domain. For example, parent-rated Somatic Distress scores increased from baseline to day+7, remaining elevated at day+21 (p<0.001); child scores were lower than parents’ across time-points. Nurses’ baseline scores were lower than parents’, though by day+21 were similar. Older child age was associated with higher Somatic Distress and Mood Disturbance scores. Worse parent emotional functioning was associated with lower scores across raters and domains except Cooperation.

Conclusion

Multi-rater assessments are highly feasible during HSCT. Ratings differ by several factors; considering ratings in light of such factors may deepen our understanding of the child’s experience.

Keywords: hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, pediatrics, patient-reported outcomes, quality of life, self-report, proxy report, observer variation

Introduction

Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) offers potential cure for children with high-risk malignancies and other life-threatening conditions. Children undergoing this intense treatment are at high risk for distressing symptoms and impaired health-related quality of life (HRQL).

Optimizing these child outcomes and providing high quality care necessitate utilization of patient-reported outcomes.1,2 While considered the “gold standard” child report is subject to many factors (e.g. medical, developmental) that influence their understanding of their illness and the questions posed, sometimes preventing them from self-reporting altogether. Parents have a uniquely longstanding and nuanced understanding of their child. Clinician proxies have the experience of caring for many children, which can shape their views about a particular child. It is widely believed that input from multiple raters generates a more global view of the child’s experience. It is therefore imperative to understand rater experiences, beliefs, expectations and other factors underlying inter-rater differences.

Little is known about child, parent and clinician perspectives on the child’s experience during HSCT, and how each contributes to a larger picture. The few extant studies on child HRQL are single-center, largely focused on the post-HSCT period.3–6 They infrequently include clinician raters, and rarely utilize instruments entirely relevant to HSCT or employ repeated measures design.3,5–8 Phipps conducted the most comprehensive multi-rater (child, parent, nurse) evaluation during the acute transplant period, a single-center study of children during the first six months post-transplant.9,10 However, factors associated with the observed inter-rater differences were not evaluated.11,12

Multiple rater perspectives woven together, may deepen our understanding of the child’s experience. This, in turn, aids accurate anticipatory guidance and sound treatment decisions, and informs interventions maximizing wellbeing during transplant, with important implications for long-term adjustment. We therefore assessed the perspectives of children, parents and nurses in the context of a large, multicenter study of child and parent-reported outcomes during HSCT. We additionally sought to determine how certain factors contribute to differences in rater scores.

Methods

Participants (n=165) were drawn from a prospective, multicenter study evaluating child and parent HRQL through one-year post-transplant that is detailed elsewhere.13–16 Child-parent dyads from six U.S. transplant centers enrolled (2003–2008). Eligible children undergoing HSCT were 5 –17.9 years old, provided age-appropriate assent and had an eligible parent who consented to participate and provided informed permission for the child’s participation. Eligible parents were ≥18 years old and had a working knowledge of English. One parent per child, designated by the parents as the parent spending the most time with the child during transplant, participated. The institutional review boards of Tufts Medical Center and all participating transplant centers approved the study.

Measures

The BASES was completed by children, parents and nurses as a secondary (optional for all) measure and is the primary focus of this analysis. Available in text-based format, it assesses acute, short-term outcomes of children hospitalized for intensive therapy (i.e., HSCT) and includes child, parent, and nurse versions. The initial 38-item measure is valid, reliable and sensitive to change.11,12

Use of the current 22-item BASES has been described; psychometrics have not.17 The child, parent, and nurse versions contain the same items. Recall periods are one day (child and parent versions) and the past shift (nurse version). Item scores range from 1–5. Parent and nurse versions of the Mood Disturbance scale were reverse scored so higher scores indicated greater distress/disturbance for all scales and raters. Items are grouped into domains: physical symptoms (5-item Somatic Distress), mood/psychological functioning (7-item Mood Disturbance), cooperation with medical care (5-item Cooperation), social interactions (3-item Getting Along), activity and sleep (1 item each). This analysis excluded activity and sleep items. Scores of items within a domain were summed using established scoring procedures to obtain domain scores at each time point. Missing items (maximum of 5–8% per item across raters) within domains primarily reflected differences in clinical care across patients and sites. Missing item scores were imputed based on the mean score of that item across all available scores at that time point for the same rater type.

Parents completed the General Health Module of the Child Health Rating Inventories, which assesses HRQL in chronically ill children and their parents in the preceding week.7,18–20 Parent emotional functioning subscale scores (range 0–100) were included in models (see below). Higher scores indicated better functioning.

Data Collection

Child, parent, and nurse raters (belonging to the child’s primary nursing team) completed the BASES via paper and pencil. At any given time point, all raters completed their assessments within a 24-hour window. Children and parents completed assessments independently, remaining blinded to one another’s responses. Trained research staff at each site administered the questionnaire to younger children (i.e. those 5–7 years of age). Participating parents were asked to leave the room, so as to not influence the child’s responses (verbally or non-verbally). Assessments were conducted at baseline (before HSCT), day+7 (seven days post-stem cell infusion) and day+21. The baseline assessment completion window was 30 days leading up to and including the day of stem cell infusion; some patients were assessed during conditioning. Day+7 and day+21 windows were +/− one day. Nursing staff were asked to use the average child, not pediatric transplant recipients, as the standard of comparison. Parents provided demographic information about the child and themselves. Detailed disease and HSCT characteristics were abstracted from the medical record.

Statistical Analysis

Analyses were based on 165 children for whom at least one BASES rating was completed. Descriptive statistics summarized child, clinical and parent characteristics. Completion rates, defined by the number of respondents completing the BASES divided by the number eligible at that time point were determined. Completers and non-completers were compared with respect to characteristics hypothesized to differ between the groups (e.g. transplant center, local versus referred to transplant center, timing of baseline assessment completion) using Fisher Exact tests and two-sample t-tests. Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to estimate internal consistency of the BASES domains at baseline. The minimum acceptable criterion for Cronbach’s alpha for exploratory scale development was considered to be ≥ 0.70, and for established scales, ≥0.80.21

Analyses were conducted using the SAS (v.9.2) statistical package (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC). Repeated measures linear regression models were created for each BASES domain and included indicators for rater and assessment period. Maximum likelihood estimation with repeated measures in SAS Proc Mixed was used to account for correlations between raters and over time, with an unstructured covariance matrix. Analyses were not restricted to children with all three raters at each time. Univariate analyses were conducted to identify variables for inclusion in the multivariable models. The following were considered: child age, child gender, HSCT type, illness duration, malignancy, baseline measure completion timing, baseline parent emotional functioning, parent education, household income, and timing of baseline assessment with respect to conditioning (before versus during).22 Variables with p>0.1 were removed via backwards elimination. Site was included in all models as a potential confounder. We assessed for interactions in rater and assessment period, and baseline timing and assessment period. Different forms of continuous variables (e.g., log, quadratic or splines) were considered if the variable was not linearly associated with the outcome. Likelihood ratio tests were used to determine the best form of the covariates. Due to lack of linear relationships among variables, Mood Disturbance, Cooperation and Getting Along Domain scores were transformed to the natural log scale and results are reported as exponentiated beta coefficients. Based on model results, least squares means were calculated and plotted for each rater and time point. Timing of baseline measures was assumed to be before conditioning, child age was set to 10, and other variables were set to their mean.

Results

With regard to the study sample, the majority of children (74%) had a hematologic malignancy. (Table 1) Half underwent allogeneic unrelated donor transplantation. Among those with cancer, half (48%) had previously relapsed.

Table 1.

Study Sample Characteristics

| Child/Clinical Characteristics (n=165) | |

|---|---|

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 10.8 (3.9) |

| median (IQR) | 11 (8–14) |

| Children ≥ 12 years, n (%) | 73 (44%) |

| Female sex, n (%) | 82 (50%) |

| White non-Hispanic, n (%) | 114 (69%) |

| Months since diagnosis, median (25–75 percentile) | 10.0 (5.0–31.0) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |

| Non-malignant condition | 24 (15%) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 120 (73%) |

| Solid tumor (peripheral/CNS) | 21 (12%) |

| Months since diagnosis, median (IQR) | 10 (5–31) |

| Prior relapse,a n (%) | 67 (48%) |

| Transplant type, n (%) | |

| Autologous | 32 (19%) |

| Allogeneic related donor | 51 (31%) |

| unrelated donor | 82 (50%) |

| Transplant center, n (%) | |

| A | 65 (40%) |

| B | 21 (13%) |

| C | 29 (17%) |

| D | 28 (17%) |

| E | 4 (2%) |

| F | 18 (11%) |

| Local to transplant center | 67 (41%) |

|

Parent Characteristics (n=165) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 38.9 (6.9) |

| median (IQR) | 39 (34–44) |

| Female, n (%) | 139 (84%) |

| White non-Hispanic, n (%) | 114 (69%) |

| Post-secondary education, n (%) | 107 (65%) |

| Income >$40,000/year, n (%) | 70 (42%) |

| Emotional functioning (baseline), mean (SD) | 49.2 (18.4) |

Children with malignancy (n=141)

Abbreviations: HSCT, hematopoietic stem cell transplant; CNS, central nervous system

Among baseline assessments, 58% were completed before conditioning. Baseline completion rates for the BASES measure were high (≥78%) for all raters, and almost all children (98%) were represented by at least one rater. (Table 2) Day+7 completion rates remained high. Day+21 rates were somewhat lower, though they remained ≥73%, with most (85%) children represented by at least one rater. Survey completers (for all rater types) were more likely to be non-local (p<0.05 for all) and nurse completion rates varied significantly across the six centers (62% to 100%, p<0.001). There were no differences between completers and non-completers with respect to baseline assessment, and child age, sex, or vital status at study end, or parent emotional functioning (all p>0.05).

Table 2.

Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Experiences Scale Completion Rates by Time Point

| Baseline | Day+7 | Day+21 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Eligible N |

Completed n (%) |

Eligible N |

Completed n (%) |

Eligible N |

Completed n (%) |

|

| Child | 165 | 152 (92) | 164 | 139 (85) | 162 | 125 (77) |

| Parent | 165 | 145 (88) | 164 | 135 (82) | 162 | 124 (77) |

| Nurse | 165 | 129 (78) | 164 | 146 (89) | 162 | 119 (73) |

| ≥1 rater | 165 | 162 (98) | 164 | 156 (95) | 162 | 137 (85) |

| ≥2 raters | 165 | 153 (93) | 164 | 150 (91) | 162 | 131 (81) |

| 3 raters | 165 | 111 (67) | 164 | 114 (70) | 162 | 100 (62) |

The BASES demonstrated adequate internal consistency at baseline. Cronbach’s alpha for all domains for parent and nurse raters were ≥0.8. They were slightly lower (≥0.69) for child-rated domains. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Cronbach’s Alpha for Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Experiences Scale Domains at Baseline

| Domain | Parent | Child | Nurse |

|---|---|---|---|

| Somatic Distress | 0.83 | 0.69 | 0.82 |

| Mood Disturbance | 0.86 | 0.82 | 0.87 |

| Cooperation | 0.80 | 0.73 | 0.86 |

| Getting Along | 0.86 | 0.77 | 0.87 |

Multivariable Domain Models

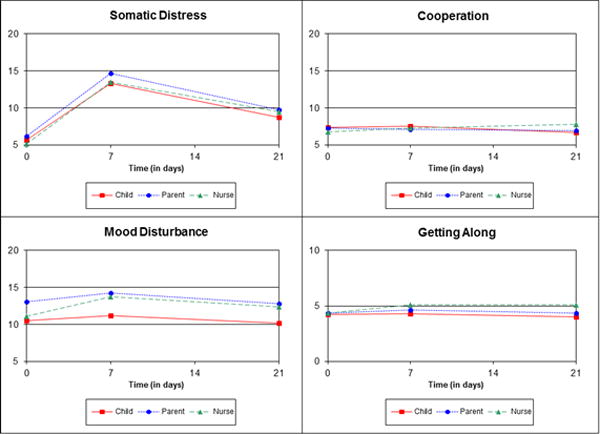

All domain models (Table 4) indicated significant interactions between assessment period and rater (p≤0.02 for all). Figure 1 plots present patterns of scores by rater over time based on the least mean squares from each model.

Table 4.

Multivariable Models of Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Experiences Scale Domains

| Somatic Distress | β(95% CI) | p |

|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 1.91 (−1.35, 5.18) | 0.25 |

| Time | <0.001a | |

| 0 days (ref) | ||

| 7 days | 8.48 (7.30, 9.66) | <0.001 |

| 21 days | 3.52 (2.39, 4.66) | <0.001 |

| Rater | <0.001a | |

| Parent (ref) | ||

| Child | −0.53 (−1.13, 0.06) | 0.08 |

| Nurse | −1.03 (−1.56, −0.51) | <0.001 |

| Time × Rater | 0.02a | |

| 7 days × child | −0.80 (−1.55, −0.05) | 0.04 |

| 21 days × child | −0.44 (−1.22, 0.34) | 0.27 |

| 7 days × nurse | −0.11 (−0.89, 0.67) | 0.78 |

| 21 days × nurse | 0.85 (0.01, 1.68) | 0.05 |

| Baseline timing | 3.91 (2.89, 4.92) | <0.001 |

| Time × Baseline timing | <0.001a | |

| 7 days × baseline timing | −4.97 (−6.29, −3.66) | <0.001 |

| 21 days × baseline timing | −3.24 (−4.50, −1.99) | <0.001 |

| Non-linear ageb | 0.52 (0.31, 0.73) | <0.001 |

| Baseline parent emotional functioning per ½ SDc | −0.17 (−0.35, 0.01) | 0.07 |

| Mood Disturbance(log) | exp(β) (95% CI) | p |

| Intercept | 11.17 (8.19, 15.23) | <0.001 |

| Time | <0.001a | |

| 0 days (ref) | ||

| 7 days | 1.09 (1.00, 1.18) | 0.04 |

| 21 days | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.66 |

| Rater | <0.001a | |

| Parent (ref) | ||

| Child | 0.81 (0.75, 0.86) | <0.001 |

| Nurse | 0.85 (0.78, 0.92) | <0.001 |

| Time × Rater | 0.04a | |

| 7 days × child | 0.98 (0.89, 1.07) | 0.64 |

| 21 days × child | 0.99 (0.90, 1.09) | 0.80 |

| 7 days × nurse | 1.14 (1.02, 1.26) | 0.02 |

| 21 days × nurse | 1.14 (1.01, 1.27) | 0.03 |

| Non-linear ageb | 1.03 (1.01, 1.05) | <0.001 |

| Baseline parent emotional functioning per ½SDc | 0.97 (0.96, 0.99) | <0.001 |

| Cooperation(log) | exp(β) (95% CI) | p |

| Intercept | 10.15 (8.71, 11.83) | <0.001 |

| Time | 0.43a | |

| 0 days (ref) | ||

| 7 days | 0.98 (0.92, 1.05) | 0.61 |

| 21 days | 0.96 (0.89, 1.02) | 0.19 |

| Rater | 0.45a | |

| Parent (ref) | ||

| Child | 1.02 (0.96, 1.08) | 0.61 |

| Nurse | 0.94 (0.88, 1.00) | 0.04 |

| Time × Rater | <0.001a | |

| 7 days × child | 1.04 (0.96, 1.12) | 0.35 |

| 21 days × child | 0.95 (0.88, 1.02) | 0.16 |

| 7 days × nurse | 1.09 (0.99, 1.20) | 0.07 |

| 21 days × nurse | 1.20 (1.10, 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Baseline timing | 1.09 (1.01, 1.18) | 0.03 |

| Non-linear aged | 0.97 (0.96, 0.98) | <0.001 |

| Getting Along(log) | exp(β) (95% CI) | p |

| Intercept | 5.07 (4.37, 5.87) | <0.001 |

| Time | 0.007a | |

| 0 days (ref) | ||

| 7 days | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) | 0.13 |

| 21 days | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) | 0.91 |

| Rater | <0.001a | |

| Parent (ref) | ||

| Child | 0.97 (0.91, 1.04) | 0.36 |

| Nurse | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | 0.91 |

| Time × Rater | 0.006a | |

| 7 days × child | 0.96 (0.88, 1.05) | 0.40 |

| 21 days × child | 0.94 (0.86, 1.03) | 0.18 |

| 7 days × nurse | 1.11 (1.00, 1.23) | 0.05 |

| 21 days × nurse | 1.17 (1.05, 1.31) | <0.001 |

| Baseline parent emotional functioning per ½SDc | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | 0.02 |

All models adjust for site.

Global test of significance

Age defined as the maximum of child’s age or 12.

A ½ SD for parent emotional functioning is 8.

Age defined as the minimum of child’s age or 12.

Figure 1.

Least Square Means from Multivariable Models Plotted for Domains of the Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Experiences Scale Y-axis range is 5–20 for all domains except Getting Along (range 0–10). Ranges were selected to best reflect the range of possible scores for each domain.

Somatic Distress

Averaged over time periods, child-rated scores were marginally lower than parents’ (β=−0.53, p=0.08). Nurses’ were also lower than parents’ (β=−1.03, p<0.001). Parent-rated scores were higher (more impairment) at day+7 than baseline (β=8.48, p<0.001). Child-rated scores were also higher at day+7 as compared with baseline, but the increase was 0.80 points less than it was for parents. The increase for nurses was similar to that for parents. Day+21 scores remained elevated compared with baseline (β=3.52 for parents, p<0.001) but to a lesser degree than day+7 scores. The baseline to day+21 difference for children was similar to that for parents, but was larger for nurses (β=0.85, p=0.05). Scores among those who completed the baseline measure during conditioning were higher (β=3.91, p<0.001); this difference was attenuated at day+7 (β=−4.97, p<0.001) and day+21 (β=−3.24, p<0.001). After age 12, older child age was associated with higher scores (β=0.52, p<0.001). Better parent emotional functioning (β=−0.17 per ½ SD, p=0.07) was marginally associated with lower scores.

Mood Disturbance

At baseline, child-rated (exp(β)=0.81, p<0.001) and nurses-rated scores were lower (exp(β)=0.85, p<0.001) than parents’. On average, all raters’ scores were higher (more impaired) at day+7 (exp(β)=1.09, p=0.04) than baseline, and nurses had even higher increases in scores (exp(β)=1.14, p=0.02), attenuating the differences seen with parents at baseline. For parents (p=0.66) and child raters (p=0.80), day+21 scores were no different than baseline, but nurses’ scores remained elevated (exp(β)=1.14, p=0.03). After age 12, older child age was associated with higher scores (exp(β)=1.03, p<0.001). Higher (better) parent emotional functioning was associated with lower scores (exp(β)=0.97 per ½ SD, p<0.001).

Cooperation

Parent scores did not vary over time (p=0.43). There were no differences between child and parent ratings at any time point. In contrast, baseline nurse scores were lower (less impaired) (exp(β)=0.94, p=0.04) than parents’; this difference marginally attenuated at day+7 (exp(β)=1.09, p=0.07). Nurses’ scores were higher than parents’ at day+21 (exp(β)=1.20, p<0.001). Scores decreased (improved) with increasing child age until age 12 (exp(β)=0.97, p<0.001), and then remained constant. Measure completion during conditioning was associated with higher scores (exp(β)=1.09, p=0.03).

Getting Along

The global test for parent scores showed variation over time (p=0.007). However, pair-wise comparisons showed no difference between baseline and day+7 (p=0.13) and day+21 (p=0.91). There was no difference between child and parent scores (p=0.36) or their changes at day+7 (p=0.40), or day+21 (p=0.18). At baseline, there was no difference between nurses’ and parents’ scores (p=0.81), but nurses’ scores were higher (more impaired) than parents’ at day+7 (exp(β)=1.11, p=0.05) and day+21 (exp(β)=1.17, p<0.001). Higher (better) baseline parent emotional function was associated with lower scores (exp(β)=0.98 per ½ SD, p=0.02).

Discussion

Our findings illustrate how children, parents and nurses provide different perspectives about the child’s HSCT experience. We also report of psychometric properties of the 22-item BASES, with internal consistency reliability for all raters at baseline. Observed trends, such as the worsening of physical and psychological symptoms after conditioning and improvement thereafter, demonstrate BASES construct validity and sensitivity to change.

Child, nurse, and parent ratings differed across time points and in their association with other factors. Child raters, for example, had lower Somatic Distress and Mood Disturbance ratings compared with parents, and younger children had lower Somatic Distress and Mood Disturbance scores than did older ones. These findings are consistent with prior observations of children post-HSCT.4 Whether this reflects less somatic and mood disturbance/impairment among children (especially younger ones), child understanding of the question, response bias, beliefs (e.g. symptoms are to be expected), or another phenomenon remains unknown.

An important factor was parent emotional functioning, with worse functioning associated with worse Somatic Distress, Mood Disturbance and Getting Along ratings for all three raters. An association between worse child HRQL and worse parent emotional functioning has been previously described.4,18,23 Child distress may worsen parent emotional functioning. The reverse is also possible. Parent ratings of their child may also be a direct reflection of their own experience. That is, parents’ impaired emotional functioning and acute awareness of transplant risks, present before and during the transplant,24 may bias their perceptions of their child.20,25 These possibilities do not negate the value of the parent perspective. In fact, because parent emotional functioning and the child’s experience are inter-related, it is an important aspect of the child’s experience. Furthermore, detection of significantly impaired child somatic, mood or social functioning should prompt further consideration of parent functioning and need for support.

We also found an interaction between nurse-rated scores and timing post-transplant. Baseline nurse-rated Somatic Distress, Mood Disturbance and Cooperation scores were better than parents’. This may be because the nurse is not yet familiar with how the child exhibits distress. However, by day+7 (Mood Disturbance, Cooperation, Getting Along) and/or day+21 (Mood Disturbance, Cooperation, Getting Along, Somatic Distress) nurse scores were worse than parents’. Worse patient (or parent) scores early in transplant may reflect high anxiety and hypervigilance for symptoms. Among adults, patient symptom ratings were worse than those of nurses at baseline, while nurse ratings were worse than patients’ at day+20–23.26 Because nurses know at the outset that symptoms will likely worsen, their initial ratings may be low, with an increase over time. While differences in nurse ratings might be attributed to different individuals completing measures at day+7 versus day+21, this is unlikely as there is no reason for ratings to systematically differ between time points.

Completion rates of the (optional) BASES were high. Furthermore, through use of three raters, the vast majority of children were represented by at least one rater at every time point. These high completion rates demonstrate that assessment of child symptoms is highly feasible in the stressful circumstances of HSCT, as is concurrent collection of data from multiple raters. We found that assessments completion was more likely if the child was referred to the transplant center. This was true across rater types, suggesting that local HSCT processes (e.g. intake evaluation and admission procedures) influence completion rates. Completion rate differences across sites may stem from variation in local clinical or research practices. Local HSCT processes may also have influenced the timing of baseline assessment completion, which was variable. Because local study and HSCT program characteristics can impact completion rates they warrant careful consideration during study design. In this study, we accounted for variable timing of baseline assessment completion by adjusting for this in the multivariable models.

A strength of this study is its longitudinal, multi-rater design allowing exploration of views of three different raters during HSCT. The repeated measures design and inclusion of clinical, child, and parent variables permitted in-depth analysis of analysis of how raters contribute to assessment of the child’s experience at various times. Few studies have evaluated factors influencing raters or parent-child agreement.27 The multicenter design increases generalizability of findings. In addition, great care was taken to have raters answer independently, thereby avoiding contamination of responses, and inflation of inter-rater agreement.

The BASES is brief and easy to complete. Even so, less medically stable children may have been less likely to be represented in the assessments. Bias in the opposite direction, favoring inclusion of ratings of less stable patients is also possible. For example, parents may have been less likely to be at the bedside (and available to complete an assessment) if the child was doing well. In future studies, reasons for missing data should be collected to evaluate patterns of missingness across all raters.

While designed to be brief to facilitate completion, the BASES’ limited item set may decrease detection of inter-rater differences. In addition, the unidimensional items focus on severity, precluding evaluation of other symptom dimensions (e.g. frequency). In addition, BASES instructions do not define the reference group for nurse raters. Despite verbal instructions defining the reference group (healthy children), use of an incorrect reference group was possible, producing “anchor drift” and decreasing response validity.

Another limitation is that the parents were largely highly educated, which could limit the generalizability of study findings. It should also be noted that the data is from 2003–2008. Shifts in practice (e.g. increased use of reduced intensity conditioning regimens, advances in supportive care) since that time might reduce the burden of transplant on children. That being said, we would not expect that parent emotional distress, which was a key factor in worse functioning associated with worse Somatic Distress, Mood Disturbance and Getting Along ratings for all three raters, would have changed significantly in the past ten years. This analysis is also limited to the acute transplant period, and whether our findings would hold true in farther out in the post-HSCT period are unknown. Further work to evaluate whether relationships between child, parent and nurse ratings have held true in recent years and how they compare with later post-HSCT time points will further elucidate the underpinnings of their ratings and the relationships between them.

Our findings make evident the feasibility of querying multiple raters, even in a population of children with serious illness undergoing intensive treatment. Different raters clearly bring unique perspectives with different factors underlying them. Taken together, they can enrich our understanding of a child’s -and parent’s- experience during HSCT. Instances of disagreement might also present opportunities to further explore the child’s experience. This deeper understanding of the child’s experience will be instrumental in supporting children and families through this intense and trying phase of transplant.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the patients, parents and nurses who shared their perspectives. We are also indebted to Patti Branowicki, MS, RN, FAAN, who championed this Study and advanced the care of children with cancer through her wisdom, compassion and steadfast dedication.

Support: American Cancer Society 5RSGPB-02-186 (Parsons, PI); 1K23HL107452 (Ullrich, PI)

Footnotes

Disclosures: None

- Conceptualization: Parsons

- Data curation: Terrin, Rodday, Parsons

- Formal analysis: Ullrich, Rodday, Tighiouart, Terrin, Parsons

- Funding acquisition: Parsons

- Investigation: Ullrich, Rodday, Terrin, Parsons

- Methodology: Ullrich, Rodday, Tighiouart, Terrin, Parsons

- Project administration: Kupst, Patel, Syrjala, Harris, Recklitis, Parsons

- Resources: Phipps, Parsons

- Software: N/A

- Supervision: Parsons

- Validation: Ullrich, Rodday, Parsons

- Visualization: Ullrich, Rodday, Parsons

- Writing–original draft: Ullrich, Rodday, Parsons

- Writing–review & editing: Ullrich, Rodday, Kupst, Bingen, Patel, Syrjala, Harris, Recklitis, Guinan, Chang, Tighiouart, Terrin, Phipps, Parsons

References

- 1.Bradlyn AS, Ritchey AK, Harris CV, et al. Quality of Life Research in Pediatric Oncology. Research Methods and Barriers. Cancer. 1996;78(6):1333–1339. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0142(19960915)78:6<1333::AID-CNCR24>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sung L. Priorities for Quality Care in Pediatric Oncology Supportive Care. J Oncol Pract. 2015;11(3):187–189. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2014.002840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feichtl RE, Rosenfeld B, Tallamy B, Cairo MS, Sands SA. Concordance of Quality of Life Assessments Following Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Psychooncology. 2010;19(7):710–717. doi: 10.1002/pon.1630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Forinder U, Lof C, Winiarski J. Quality of Life Following Allogeneic Stem Cell Transplantation, Comparing Parents’ and Children’s Perspective. Pediatr Transplant. 2006;10(4):491–496. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3046.2006.00507.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barrera M, Boyd-Pringle LA, Sumbler K, Saunders F. Quality of Life and Behavioral Adjustment after Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2000;26(4):427–435. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1702527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nespoli L, Verri AP, Locatelli F, Bertuggia L, Taibi RM, Burgio GR. The Impact of Paediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation on Quality of Life. Qual Life Res. 1995;4(3):233–240. doi: 10.1007/BF02260862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parsons SK, Barlow SE, Levy SL, Supran SE, Kaplan SH. Health-Related Quality of Life in Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplant Survivors: According to Whom? Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:46–51. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<46::aid-ijc9>3.0.co;2-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Felder-Puig R, di Gallo A, Waldenmair M, et al. Health-Related Quality of Life of Pediatric Patients Receiving Allogeneic Stem Cell or Bone Marrow Transplantation: Results of a Longitudinal, Multi-Center Study. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2006;38(2):119–126. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1705417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Lensing S, Rai SN. Acute Health-Related Quality of Life in Children Undergoing Stem Cell Transplant: II. Medical and Demographic Determinants. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(5):435–442. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Garvie PA, Lensing S, Rai SN. Acute Health-Related Quality of Life in Children Undergoing Stem Cell Transplant: I. Descriptive Outcomes. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2002;29(5):425–434. doi: 10.1038/sj.bmt.1703377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Phipps S, Dunavant M, Jayawardene D, Srivastiva DK. Assessment of Health-Related Quality of Life in Acute in-Patient Settings: Use of the Bases Instrument in Children Undergoing Bone Marrow Transplantation. Int J Cancer Suppl. 1999;12:18–24. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0215(1999)83:12+<18::aid-ijc5>3.0.co;2-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Phipps S, Hinds PS, Channell S, Bell GL. Measurement of Behavioral, Affective, and Somatic Responses to Pediatric Bone Marrow Transplantation: Development of the Bases Scale. J Pediatr Oncol Nurs. 1994;11(3):109–117. doi: 10.1177/104345429401100305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bingen K, Kent MW, Rodday AM, Ratichek SJ, Kupst MJ, Parsons SK. Children’s Coping with Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Stressors: Results from the Journeys to Recovery Study. Children’s Health Care. 2012;41(2):145–161. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang G, Ratichek SJ, Recklitis C, et al. Children’s Psychological Distress During Pediatric Hsct: Parent and Child Perspectives. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;58(2):289–296. doi: 10.1002/pbc.23185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rodday AM, Terrin N, Chang G, Parsons SK. Performance of the Parent Emotional Functioning (Premo) Screener in Parents of Children Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation. Qual Life Res. 2013;22(6):1427–1433. doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0240-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terrin N, Rodday AM, Tighiouart H, Chang G, Parsons SK, Journeys to Recovery S Parental Emotional Functioning Declines with Occurrence of Clinical Complications in Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(3):687–695. doi: 10.1007/s00520-012-1566-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Phipps S, Barrera M, Vannatta K, Xiong X, Doyle JJ, Alderfer MA. Complementary Therapies for Children Undergoing Stem Cell Transplantation: Report of a Multisite Trial. Cancer. 2010;116(16):3924–3933. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rodday AM, Terrin N, Parsons SK, Journeys to Recovery S, Study H-C Measuring Global Health-Related Quality of Life in Children Undergoing Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant: A Longitudinal Study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-11-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Mayer DK, et al. Preliminary Psychometric Evaluation of the Child Health Ratings Inventory (Chris) and Disease-Specific Impairment Inventory-Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (Dsii-HSCT) in Parents and Children. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(6):1613–1625. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-1004-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Parsons SK, Shih MC, Duhamel KN, et al. Maternal Perspectives on Children’s Health-Related Quality of Life During the First Year after Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. J Pediatr Psychol. 2006;31(10):1100–1115. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsj078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nunnally JaB, I. Psychometric Theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Parsons SKS,MC, Ratichek S, Recklitis CJ, Chang G. Establishing the Baseline in Longitudinal Evaluation of Health-Related Quality of Life (Hrql): The Pediatric Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (Hsct) Example. Paper presented at: Presentation at the Patient-Reported Outcomes Assessment in Cancer Trials; September, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barrera M, Atenafu E, Hancock K. Longitudinal Health-Related Quality of Life Outcomes and Related Factors after Pediatric SCT. Bone Marrow Transplant. 2009;44(4):249–256. doi: 10.1038/bmt.2009.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodrigue JR, Hoffmann RG, 3rd, MacNaughton K, et al. Mothers of Children Evaluated for Transplantation: Stress, Coping Resources, and Perceptions of Family Functioning. Clin Transplant. 1996;10(5):447–450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jobe-Shields L, Alderfer MA, Barrera M, Vannatta K, Currier JM, Phipps S. Parental Depression and Family Environment Predict Distress in Children before Stem Cell Transplantation. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2009;30(2):140–146. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181976a59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Larson PJ, Viele CS, Coleman S, Dibble SL, Cebulski C. Comparison of Perceived Symptoms of Patients Undergoing Bone Marrow Transplant and the Nurses Caring for Them. Oncol Nurs Forum. 1993;20(1):81–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. Parent-Child Agreement across Child Health-Related Quality of Life Instruments: A Review of the Literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17(6):895–913. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9350-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]