Abstract

Background

Race/ethnicity remains an important barrier in clinical care. We investigated differences in autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) utilization in multiple myeloma (MM) and outcomes based on race/ethnicity in the United States.

Methods

The CIBMTR database identified 28,450 patients who underwent AHCT for MM from 2008–2014. Using SEER 18, the incidence of MM was calculated. A stem cell transplant utilization rate (STUR) was derived. Among patients 18–75 years undergoing melphalan-conditioned peripheral cell grafts (N=24,102), we analyzed post-AHCT outcomes.

Results

The STUR increased across all groups from 2008 to 2014. The increase was substantially lower among Hispanics (8.6% to 16.9%) and non-Hispanic Blacks (12.2% to 20.5%) than for non-Hispanic Whites (22.6% to 37.8%). There were 18,046 non-Hispanic Whites, 4123 non-Hispanic Blacks and 1933 Hispanic patients. The Hispanic group was younger (p <0.001). Fewer patients over 60 were transplanted in Hispanic (39%) and non-Hispanic Blacks (42%) vs. non-Hispanic Whites (56%). A Karnofsky score <90 and HCT-CI>3 were more common in non-Hispanic Blacks compared to Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites (p<0.001). More Hispanic (57%) vs. non-Hispanic Blacks (54%) and non-Hispanic Whites (52%) (p<0.001) had stage III disease. More Hispanics (48%) vs. non-Hispanic Blacks (45%) and non-Hispanic Whites (44%) were in ≥very good partial response pre-transplant (p=0.005). Race/Ethnicity did not impact post-AHCT outcomes.

Conclusions

Although increasing, STUR remains low and significantly lower among Hispanic followed by non-Hispanic Blacks compared to non-Hispanic Whites. Race/ethnicity does not impact transplant outcomes. Efforts to increase transplant utilization for eligible MM patients, with emphasis on groups underutilizing transplant are warranted.

Keywords: myeloma, transplant utilization, Hispanic, Blacks

Introduction

Recent studies have confirmed the role of upfront autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (AHCT) in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM) even in the age of novel induction therapies.1–4 Despite these data and continued recommendations from the National Comprehensive Cancer Center (NCCN) that transplant should be considered in patients with symptomatic disease,5 studies from the United States (US) suggest that transplant is only used in approximately 30% of MM patients.6–8 Understanding barriers is critical to developing strategies to increase utilization of AHCT as a therapeutic option.

The role of race on the utilization and efficacy of AHCT in patients with MM has been previously studied.8–10 Despite a significantly higher incidence of MM in Blacks compared to Whites, these studies have shown lower utilization rates in Blacks. Importantly, studies have also showed that there are no differences in outcomes such as treatment-related mortality and survival after AHCT for MM based on race.9,10

There is little data on the utilization or efficacy of AHCT in other ethnic groups especially among patients who self-identify as Hispanic, which is the fastest growing segment of the population in the US. Using the Center for International Blood and Transplant Research (CIBMTR®) and Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) databases, we sought to identify differences in transplant utilization and outcomes among self-identified racial and ethnic groups among patients with MM who underwent an AHCT in the US.

Patients and Methods

Data source

The CIBMTR registry is a prospectively maintained transplant database that collects transplant data from over 450 centers worldwide. Data are submitted to the Statistical Center at the Medical College of Wisconsin in Milwaukee, where computerized checks for discrepancies, physicians’ review of submitted data, and on-site audits of participating centers ensure data quality. Collected data include disease type, age, gender, self-identified ethnicity, date of diagnosis, graft type, conditioning regimen, post-transplantation disease progression, survival and cause of death and includes all transplants reported to the CIBMTR. Data are collected pre-transplantation, 100 days and 6 months post-transplantation, and annually thereafter until death or last follow up. Between 2008 and 2014, the CIBMTR captured 75–80% of all autologous transplants performed in the US. For the purposes of this study, it was assumed that there was no systematic age, sex, race/ethnicity biases in reporting AHCT to the CIBMTR.

Patients

All US patients registered with the CIBMTR for a first AHCT for MM in 2008–2014 were collected (N=28,450) and used to determine stem cell transplant utilization rate (STUR). Only first transplants were counted. Among these, patients aged 18–75 years who received peripheral hematopoietic cells, with melphalan conditioning, provided informed consent and had a 100 day follow up form reported were included in the descriptive and multivariate analyses (N=24,102).

The incidence of MM was obtained from the SEER Program of the US National Cancer Institute. SEER data are derived from registries covering approximately 27.8% of the US population; we used SEER 18 database, which contains patients diagnosed from 2002–2013. Using publicly available software which also provides US population estimates (SEER*Stat, version 8.3.2), we calculated incidence rates per 100,000 persons for the years 2008–2013. We combined MM incidence derived from the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results program with transplantation activity reported to the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research for the period of 2008 to 2013 to assess the impact of disparities in AHCT.

Statistical Analysis

An estimate of transplant rate was calculated. This stem cell transplant utilization rate (STUR) was defined as new AHCT in a given year divided by newly diagnosed number of MM patients for that year. The number of new AHCT each year was calculated as the number of AHCT reported to the CIBMTR divided by the CIBMTR capture rate. Since the estimate of the CIBMTR capture rate during this time was 75–80%, a sensitivity analysis was performed to provide a range to the rate for +/−5% for the CIBMTR AHCT transplant capture rate in each year.

Patient-, disease- and treatment-related factors were compared using the chi-square test for categorical and the Kruskall-Wallis test for continuous variables. Outcomes analyzed included transplant related mortality (TRM), relapse/progression, progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS). Estimates of outcomes were reported as probabilities with 95% confidence intervals (CI). The probability of OS was calculated with the Kaplan-Meier estimator, with the variance estimated by Greenwood formula. Comparison of survival curves was done with the log-rank test. Multivariate analysis on OS was performed using a Cox proportional hazards model with race/ethnicity as the main effect. We explored interactions between the main effect and the variables in the final model. The assumption of proportional hazards was tested for each variable, and factors violating the proportionality assumption were adjusted by stratification. Potential interactions between the main effect and all other significant risk factors were tested. All p-values are 2-sided and given the large sample size, a p-value of <0.01 was considered significant a priori.

Results

Table 1 shows the incidence rate of MM calculated using the SEER database for the years 2008–2013. Next, the STUR was calculated (Supplemental table). The incidence of MM in the Hispanic and Non-Hispanic White groups remained stable during this period at an incidence rate of 5.6–6.3 per 100,000 for H and 5.7–6.0 per 100,000 for NHW. Among the Non-Hispanic Black group, the incidence of MM was nearly double at 12.7–13.7 per 100,000 during this time period. Overall STUR estimate was 19.1 (95% CI: 18.5–19.6) % in 2008 and increased to 30.8 (95% CI:30.0–31.6)% in 2013. When parsed between the 3 racial/ethnic groups, the STUR estimate increased across all three groups from 8.6 (95% CI:7.9–9.4)% in 2008 to 16.9 (95% CI:15.6–18.3)% in 2013 for Hispanics, 12.2 (95% CI:11.4–13.0)% in 2008 to 20.5 (95% CI:19.4–21.8)% in 2013 for non-Hispanic Blacks and from 22.6 (95% CI:21.8–23.9)% in 2008 to 37.8 (95% CI:35.5–38)% in 2013 for non-Hispanic Whites groups.

Table 1.

Stem cell Transplant Utilization Rates in Multiple Myeloma. Incidence rate is age-adjusted and shown per 100,000 persons; STUR rate is shown in percent. Both rates include the 95% confidence intervals in parenthesis.

| Year | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | Overall STUR estimate% | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Incidence | STUR estimate% | Incidence | STUR estimate% | Incidence | STUR estimate% | ||

| 2008 | 5.8 (5.3–6.3) |

8.6 (7.9 –9.4) |

12.6 (11.7–13.4) |

12.2 (11.4 –13.0) |

5.7 (5.5–5.9) |

22.6 (21.8 –23.9) |

19.1 (18.5–19.6) |

| 2009 | 5.9 (5.4–6.4) |

9.8 (9.0 –10.7) |

12.9 (12.1–13.8) |

13.2 (12.4 –14) |

5.7 (5.5–5.9) |

26.6 (25.7 –27.5) |

21.9 (21.3–22.5) |

| 2010 | 6.0 (5.5–6.5) |

11.9 (10.9–13.0) |

12.9 (12.2–13.8) |

15.7 (14.8–16.8) |

6.0 (5.8–6.2) |

29.4 (28.4–30.4) |

24.7 (24.1–25.4) |

| 2011 | 6.3 (5.9–6.9) |

11.4 (10.6–12.4) |

13.3 (12.5–14.1) |

18.2 (17.1–19.3) |

5.9 (5.7–6.1) |

34 (32.9 –35.1) |

27.8 (27.1–28.6) |

| 2012 | 6.2 (5.7–6.7) |

14.2 (13.1–15.4) |

13.7 (12.9–14.5) |

19 (18–20.2) |

6.0 (5.8–6.2) |

35.4 (34.3–36.6) |

29.5 (28.8–30.3) |

| 2013 | 5.6 (5.2–6.1) |

16.9 (15.6 –18.3) |

13.3 (12.5–14.1) |

20.5 (19.4–21.8) |

5.8 (5.6–6.0) |

37.8 (35.5 –38) |

30.8 (30.0–31.6) |

STUR- stem cell utilization rate

Table 2 shows the characteristics of 24,102 patients aged 18–75 years undergoing a first AHCT for MM reported to the CIBMTR between 2008 and 2014 who received melphalan conditioning and peripheral hematopoietic cell transplant, with at least 100 days of follow up using CIBMTR registration level data which captured 75–80% of MM AHCT activity in the US during this time period. In this cohort, we identified 18046 NHW, 1933 H and 4123 non-Hispanic Blacks who underwent transplantation.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics (N=24,102)

| Variable | Hispanic | Non-Hispanic Black | Non-Hispanic White | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of enrolled patients | 1933 | 4123 | 18046 | |

| Number of centers | 111 | 126 | 135 | |

| Patient-related variables | ||||

| Median age at transplant, years | 57 (19–75) | 58 (20–75) | 61 (19–75) | <0.001 |

| <45 | 213 (11) | 395 (10) | 838 (5) | |

| 45–60 | 972 (50) | 2003 (49) | 7164 (40) | |

| 61–75 | 748 (39) | 1725 (42) | 10044 (56) | |

| Gender, Male | 1097 (57) | 2062 (50) | 10693 (59) | <0.001 |

| Karnofsky Score, <90% | 750 (39) | 1807 (44) | 7116 (39) | <0.001 |

| HCT-CI index | <0.001 | |||

| No comorbidity | 618 (32) | 920 (22) | 5043 (28) | |

| 1–2 | 639 (33) | 1241 (30) | 5353 (30) | |

| >=3 | 465 (24) | 1587 (38) | 6209 (34) | |

| Missing | 211 (11) | 375 (9) | 1441 (8) | |

| Disease-related variables | ||||

| Immunochemical subtype | <0.001 | |||

| IgG | 1055 (55) | 2652 (64) | 10154 (56) | |

| IgA | 410 (21) | 662 (16) | 3899 (22) | |

| Light chain | 399 (21) | 725 (18) | 3469 (19) | |

| Non-secretory | 41 (2) | 61 (1) | 302 (2) | |

| Others | 28 (1) | 22 (<1) | 221 (1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (<1) | 1 (<1) | |

| Advanced Stage at diagnosis(ISS/DSS III) | 1100 (57) | 2216 (54) | 9379 (52) | <0.001 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | <0.001 | |||

| < 6 months | 436 (23) | 860 (21) | 5454 (30) | |

| 6 – 12 months | 860 (44) | 1839 (45) | 7864 (44) | |

| > 12 months | 634 (33) | 1420 (34) | 4699 (26) | |

| Missing | 3 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 29 (<1) | |

| Transplant-related variables | ||||

| Melphalan dose 200 mg/m2 | 1636 (85) | 3488 (85) | 15469 (86) | 0.29 |

| Disease Status prior to Transplant | 0.005 | |||

| sCR/CR | 315 (16) | 571 (14) | 2551 (14) | |

| VGPR | 611 (32) | 1260 (31) | 5388 (30) | |

| PR | 787 (41) | 1809 (44) | 8079 (45) | |

| SD/Relapse/Progression | 212 (11) | 476 (12) | 1953 (11) | |

| Missing | 8 (<1) | 7 (<1) | 75 (<1) | |

| Planned post-transplant therapy | <0.001 | |||

| No | 1571 (81) | 3205 (78) | 13426 (74) | |

| Yes | 360 (19) | 914 (22) | 4585 (25) | |

| Missing | 2 (<1) | 4 (<1) | 35 (<1) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 36 (1–99) | 37 (1–97) | 38 (1–98) |

Abbreviations: HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; ISS, International Staging System; DSS, Durie-Salmon Staging; CR, complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease

There were significant differences in pre-transplant characteristics between groups. The Hispanic group was younger with a median age of 57 (range 19–75) years versus non-Hispanic Blacks 58 (20–75) years and non-Hispanic Whites 61 (19–75) years (p<0.001). Fewer patients over the age of 60 were transplanted in the Hispanics (39%) and non-Hispanic Blacks (42%) groups versus the non-Hispanic Whites group (56%) (p< 0.001). More females underwent transplant in the non-Hispanic Blacks (50%) and Hispanic group (43%) versus the non-Hispanic Whites group (41%) (p<0.001). A greater proportion of non-Hispanic Blacks (44%) had lower Karnofsky scores (< 90%) versus Hispanic and non-Hispanic Whites (39% each) (p<0.001). Similarly a higher proportion of non-Hispanic Blacks (38%) and non-Hispanic Whites (34%) had higher hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index (HCT-CI) of >= 3 versus Hispanics (24%) (p<0.001). Advanced stage (Durie-Salmon or ISS Stage III) was more common among the Hispanic (57%) and non-Hispanic Black (54%) groups versus non-Hispanic Whites (52%) (p<0.001). Non-Hispanic Whites had a greater proportion proceeding to transplant < 6 months from diagnosis (30%) versus Hispanic (23%) and non-Hispanic Black patients (21%) (p<0.001). More Hispanic (48%) patients were in a VGPR or better disease status at AHCT compared with non-Hispanic Blacks (45%) and non-Hispanic Whites (44%) (p<0.005).

We then characterized further details of the 1933 Hispanic patients who proceeded to transplant (Table 3). The majority (N=1590) identified as Hispanic White, 64 as Hispanic Black and 279 as Hispanic Other. There were no differences between these groups noted for age, gender, Karnofsky score, HCT-CI score, time to transplant and pre-transplant staging. There were a higher number of patients with stage III disease in the Hispanic White (59%) versus Hispanic Black (55%) and Hispanic Other (47%) (p 0.008).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Hispanic patients (N=1933)

| Variable | Hispanic White | Hispanic Black | Hispanic Others | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of enrolled patients | 1590 | 64 | 279 | |

| Number of centers | 102 | 32 | 54 | |

| Patient-related variables | ||||

| Median age at transplant, year | 57 (19–75) | 57 (40–74) | 57 (28–74) | 0.46 |

| <45 | 184 (12) | 4 (6) | 25 (9) | |

| 45–60 | 793 (50) | 32 (50) | 147 (53) | |

| 61–75 | 613 (39) | 28 (44) | 107 (38) | |

| Sex, Male | 907 (57) | 30 (47) | 160 (57) | 0.27 |

| Karnofsky Score <90% | 621 (39) | 28 (44) | 101 (36) | 0.72 |

| HCT-CI index | 0.09 | |||

| No comorbidity | 502 (32) | 19 (30) | 97 (35) | |

| 1–2 | 524 (33) | 15 (23) | 100 (36) | |

| ≥ 3 | 381 (24) | 23 (36) | 61 (22) | |

| Missing | 183 (12) | 7 (11) | 21 (8) | |

| Clinical Trial Enrollment | 51 (3) | 1 (2) | 13 (5) | 0.33 |

| Disease-related variables | ||||

| Immunochemical subtype | 0.67 | |||

| IgG | 862 (54) | 36 (56) | 157 (56) | |

| IgA | 340 (21) | 11 (17) | 59 (21) | |

| Light chain | 332 (21) | 15 (23) | 52 (19) | |

| Non-secretory | 35 (2) | 2 (3) | 4 (1) | |

| Others | 21 (1) | 0 | 7 (3) | |

| ISS/DSS III | 934 (59) | 35 (55) | 131 (47) | 0.008 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | 0.52 | |||

| < 6 months | 369 (23) | 12 (19) | 55 (20) | |

| 6 – 12 months | 711 (45) | 26 (41) | 123 (44) | |

| > 12 months | 508 (32) | 26 (41) | 100 (36) | |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Transplant-related variables | ||||

| Melphalan dose 200 mg/m2 | 1336 (84) | 51 (80) | 249 (89) | 0.04 |

| Disease status prior transplant | 0.98 | |||

| sCR/CR | 259 (16) | 10 (16) | 46 (16) | |

| VGPR | 499 (31) | 18 (28) | 94 (34) | |

| PR | 653 (41) | 27 (42) | 107 (38) | |

| SD/Relapse/Progression | 172 (11) | 9 (14) | 31 (11) | |

| Missing | 7 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | |

| Planned post-transplant therapy | 0.03 | |||

| No | 1294 (81) | 60 (94) | 217 (78) | |

| Yes | 295 (19) | 4 (6) | 61 (22) | |

| Missing | 1 (<1) | 0 | 1 (<1) | |

| Median follow-up of survivors (range), months | 37 (1–99) | 37 (4–74) | 25 (1–82) |

Abbreviations: HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; ISS, International Staging System; DSS, Durie-Salmon Staging; CR, complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease

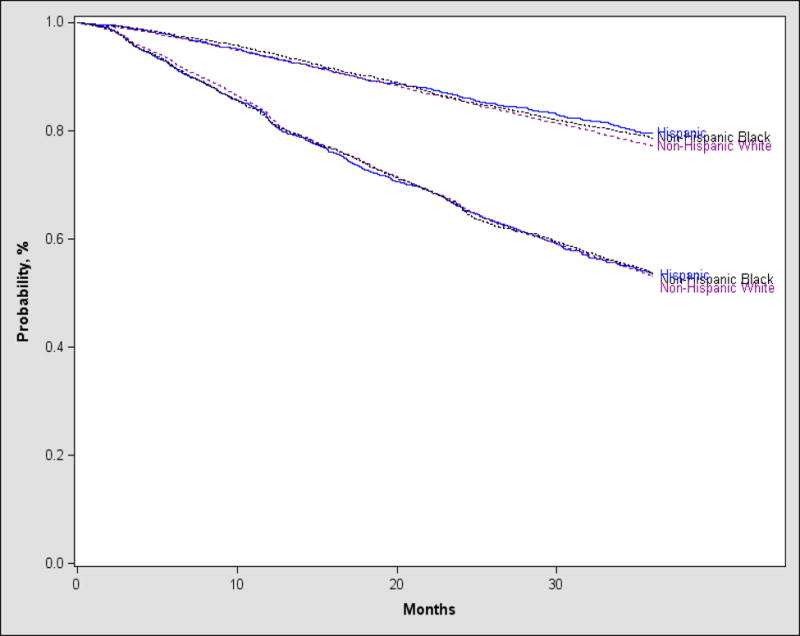

Post-transplant outcomes are shown in Table 4. There was no difference seen amongst the different racial and ethnic groups for TRM, PFS or OS (Figure 1). On multivariate analysis (Table 5), race and ethnicity had no influence on survival (Table 5), however older age (61–75 years), male sex, Karnofsky score < 90, HCT-CI score >= 3, longer interval from diagnosis to transplant (> 12 months), lower melphalan dose for conditioning (140 mg/m2) and adverse disease status (< CR) pre-transplant adversely affected survival.

Table 4.

Univariate outcomes of patients characterized by race and ethnicity (N=24,102)

| Outcomes | Hispanic (N = 1933) |

Non-Hispanic Black (N = 4123) |

Non-Hispanic White (N = 18046) |

p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

N | Prob (95% CI) |

||

| NRM | 1926 | 4104 | 18006 | 0.36‡ | |||

| 100 day | 0.6 (0.3–1)% | 0.6 (0.4–0.9)% | 0.9 (0.7–1)% | 0.15 | |||

| 1-year | 2 (2–3)% | 3 (2–3)% | 3 (2–3)% | 0.70 | |||

| PFS | 1926 | 4104 | 18006 | 1.0‡ | |||

| 1-year | 82 (80–84)% | 82 (81–83)% | 83 (82–83)% | 0.30 | |||

| 2-year | 66 (64–68)% | 66 (64–67)% | 66 (65–67)% | 0.93 | |||

| 3-year | 54 (51–56)% | 54 (52–55)% | 53 (52–54)% | 0.84 | |||

| OS | 1932 | 4120 | 18030 | 0.13‡ | |||

| 1-year | 94 (93–95)% | 94 (94–95)% | 94 (93–94)% | 0.26 | |||

| 2-year | 86 (85–88)% | 86 (85–87)% | 86 (85–86)% | 0.72 | |||

| 3-year | 80 (77–82)% | 79 (77–80)% | 77 (77–78)% | 0.05 | |||

Abbreviations: NRM, non-relapse mortality; PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival

Figure 1.

Progression-free and Overall Survival after AHCT in MM based on race and ethnicity

Table 5.

Multivariate analysis of overall survival

| Effect | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|

| Main Effect | 0.08 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 0.99 (0.89–1.11) | 0.2 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 1.07 (0.97–1.18) | 0.9 |

| Age | <.0001 | |

| <45 | 1 | |

| 45–60 | 1.15 (1.02–1.30) | 0.02 |

| 61–75 | 1.33(1.18–1.50) | <.0001 |

| Gender | <.0001 | |

| Male | 1 | |

| Female | 0.87 (0.823–0.92) | |

| Karnofsky score | <.0001 | |

| ≥90% | 1 | |

| <90% | 1.23 (1.19–1.32) | |

| Missing | 1.14 (1.01–1.29) | |

| HCT-CI | <.0001 | |

| No comorbidity | 1 | |

| 1–2 | 1.04 (0.97–1.11) | 0.26 |

| ≥3 | 1.21 (1.13–1.29) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 0.87 (0.79–0.96) | 0.006 |

| Stage at diagnosis | <.0001 | |

| <III | 1 | |

| III | 1.46 (1.39–1.54) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 1.17 (1.02–1.34) | 0.02 |

| Time from diagnosis to transplant | <.0001 | |

| <6 months | 1 | |

| 6–12 months | 1.08 (1.01–1.15) | 0.03 |

| >12 months | 1.44 (1.34–1.54) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 2.13 (1.28–3.55) | 0.004 |

| Melphalan dose | <.0001 | |

| 140 mg/m2 | 1 | |

| 200 mg/m2 | 0.85 (0.80–0.91) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 0.41 (0.06–2.93) | 0.4 |

| Disease status at transplant | <.0001 | |

| sCR/CR | 1 | |

| VGPR | 1.22 (1.11–1.33) | <.0001 |

| PR | 1.32 (1.22–1.44) | <.0001 |

| SD/Relapse/Progression | 2.04 (1.84–2.25) | <.0001 |

| Missing | 1.39 (0.85–2.28) | 0.2 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HCT-CI, hematopoietic cell transplantation-comorbidity index; CR, complete response; VGPR, very good partial response; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease

Discussion

Multiple myeloma is one of the model cancers in which survival for patients has increased considerably during the first decade of the 21st century. However, this improvement has not increased across all racial/ethnic strata in the US. Multiple studies have shown disparities in outcomes in MM using SEER data. Pulte, et al. showed improvement in age-adjusted 5-year relative survival in MM to increase from 35.6% in 1998–2001 to 44% in 2006–2009.11 However, this increase was greatest for non-Hispanic Whites and excess mortality hazard ratios were observed amongst non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanics compared to non-Hispanic Whites11 suggesting that ethnic minorities may have not benefited from the advances in MM therapies to similar extent as non-Hispanic Whites patients have. Ailawadhi, et al. also showed similar findings using the SEER 17 Registry data.12

While AHCT is not a new therapy in MM, despite the availability of several novel therapies it remains an important treatment option, especially in the upfront setting based on numerous recent studies.1–3,13 We conducted this research to better understand disparities in transplant utilization in the US. In this large database study that captures the majority of MM AHCT activity in the US, we make the following observations: 1) STUR in MM has improved significantly from 2008 to 2013; 2) However, despite the increase, overall STUR was only 30.8% in 2013 and lowest among Hispanics followed by non-Hispanic Blacks and highest among non-Hispanic Whites; 3) Hispanic patients who undergo AHCT for MM tend to be younger, fitter and with more advanced disease; 4) Race/ethnicity did not impact post-AHCT MM outcomes.

Despite compelling evidence and NCCN recommendations5 that MM patients be evaluated at a stem cell transplant center, transplant utilization remains low at approximately 30.8% in 2013. Despite an almost doubling of the STUR rate from 8.6 to 16.9 % in Hispanics and a 70% increase in STUR rates in Blacks (12.2 to 20.5%), they remain substantially lower than non-Hispanic Whites which rose from 22.6 to 37.8 % in the same time frame. In addition, the rate increase of transplanted patients from 2008–2013 was far greater in non-Hispanic Whites (15.2 %), versus non-Hispanic Blacks (8.3%) and Hispanic (8.3%) groups. This means that Hispanic patients are transplanted at less than half the rate of non-Hispanic Whites (45%) and non-Hispanic Black patients are transplanted at a just over half the rate (54%) of non-Hispanic Whites. Others have also shown that non-Hispanic Blacks and Hispanic patients have lower incidence of AHCT in MM.6,8 Al-Hamadani, et al. demonstrated that older age, lower levels of education and household income, non-managed health care, residence in a metropolitan area, treatment at a community center, a treatment facility outside the Midwest and Western regions as well as racial and ethnic minorities are all less likely to predict receipt of AHCT in MM.6 Joshua, et al. has previously showed that transplant, both autologous and allogeneic, is used more frequently in White than in Black individuals to treat leukemia, lymphoma and MM.10

Our data also show that there is a difference by race/ethnicity in the profile of patients receiving AHCT for MM. Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients tend to be younger, with few patients over the age of 60 transplanted among these groups than the non-Hispanic White group. This is particularly poignant in MM, given the median age at diagnosis of MM is 69 years.14 This finding may also account in part for some of the differences in STUR across race/ethnicities. Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients were also more likely to have advanced stage disease at diagnosis and to undergo transplant later from diagnosis than non-Hispanic White patients. This confirms results from a small single center study from Baltimore which showed that among MM patients referred for AHCT, Black patients were younger and often had delayed referrals for AHCT than White patients.15 We now extend this finding to Hispanic patients as well.

Hispanic patients had a significantly higher percentage with lower comorbidity scores and were more likely to have a better disease status (> VGPR) prior to transplant compared with non-Hispanic Black and non-Hispanic White patients. This suggests that Hispanic patients that undergo transplant tend to be younger, fitter with more advanced but responsive disease and are transplanted later in their disease course than non-Hispanic White patients. Non-Hispanic Black recipients of AHCT are also with a similar profile - younger, with more advanced disease and transplanted later than non-Hispanic White patients. In addition, they were more likely to have higher comorbidities than non-Hispanic White and Hispanic patients. Fiala, et al. showed that the racial disparities between Black and White patients with MM undergoing AHCT are not fully accounted for by age, gender, socioeconomic status, insurance and comorbidities.16 The Institute of Medicine has also reported that racial and ethnic disparities in healthcare are not entirely explained by the differences in access to care, clinical appropriateness or patient preferences.17 Studies have also documented differential receipt of technical aspects of care such as tests and therapies and procedures among racial/ethnic minorities compared with Whites even after the control for insurance status and access to medical care.18 These data point toward an interplay of many other complex factors such as physician bias, referral bias, cultural beliefs, language barriers that may affect the utilization of AHCT among different race/ethnic groups.

Previous literature, including from the CIBMTR, has shown that post-transplant outcomes are identical regardless of race.9,15,19 Our current results extend that literature among ethnic subgroups with identical results. With this in mind and recognizing the differences in STUR, we believe it is time to have a concerted effort to improve STUR among all groups with special emphasis for the low performing ethnicities. NCCN and other national guidelines could address the fact that outcomes for similarly treated patients are comparable across racial and ethnic groups but utilization variable.

Our data have some limitations. Our assumption was that there was no age, sex, race/ethnicity bias in reporting AHCT to the CIBMTR. It is possible but highly unlikely that such a bias exists in the reporting of data to the CIBMTR and that this could have influenced the STUR rates across ethnic groups. Notably, centers are required to register consecutive patients and this is audited and monitored by a robust continuous performance improvement process. Secondly, it is unlikely given the magnitude of the disparities observed that systematic under reporting would account for the difference in STUR rates although it could influence the patient differences noted between ethnic groups in terms of those who proceed to transplant. In addition, our data are based on only those patients who actually proceed to transplant and we cannot comment in this analysis on those patients with MM who did not proceed to AHCT. It is possible that in areas with a high proportion of Hispanic patients transplant centers may not be located at an accessible distance. For instance, for the majority of the time from 2008–2013 there was not a local transplant center for patients in New Mexico and Nevada where a sizable share of the state population is Hispanic (48% and 28%).20 Eligible patients would have had to travel out of state to get transplant. Previous studies have shown such barriers may decrease utilization of transplant and this by itself may be an important factor in the lower STUR rates noted among Hispanics.10 Our strength however is in our ability to capture of the majority of MM patients who received an AHCT in the US.

With clear data showing no differences in outcomes and a clear difference in transplant utilization by ethnic groups, it is crucial that we now perform additional studies to understand why a disproportionate number of Black and Hispanic patients fail to undergo transplant for MM. It is also important that race and ethnicity should be clearly delineated as factors that do not impact outcomes in terms of proceeding to transplant. Further education on early referral to transplant centers for all populations is critical, and efforts should be made to expand community outreach across racial and ethnic groups. Development of strategies to increase access to transplant across all ethnic groups with an emphasis on those who are currently underutilizing this modality is urgently needed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The CIBMTR is supported by Public Health Service Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U24-CA076518 from the National Cancer Institute (NCI), the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID); a Grant/Cooperative Agreement 5U10HL069294 from NHLBI and NCI; a contract HHSH250201200016C with Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA/DHHS); two Grants N00014-15-1-0848 and N00014-16-1-2020 from the Office of Naval Research; and grants from Alexion; *Amgen, Inc.; Anonymous donation to the Medical College of Wisconsin; Astellas Pharma US; AstraZeneca; Be the Match Foundation; *Bluebird Bio, Inc.; *Bristol Myers Squibb Oncology; *Celgene Corporation; Cellular Dynamics International, Inc.; *Chimerix, Inc.; Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center; Gamida Cell Ltd.; Genentech, Inc.; Genzyme Corporation; *Gilead Sciences, Inc.; Health Research, Inc. Roswell Park Cancer Institute; HistoGenetics, Inc.; Incyte Corporation; Janssen Scientific Affairs, LLC; *Jazz Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Jeff Gordon Children’s Foundation; The Leukemia & Lymphoma Society; Medac, GmbH; MedImmune; The Medical College of Wisconsin; *Merck & Co, Inc.; Mesoblast; MesoScale Diagnostics, Inc.; *Miltenyi Biotec, Inc.; National Marrow Donor Program; Neovii Biotech NA, Inc.; Novartis Pharmaceuticals Corporation; Onyx Pharmaceuticals; Optum Healthcare Solutions, Inc.; Otsuka America Pharmaceutical, Inc.; Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co, Ltd. – Japan; PCORI; Perkin Elmer, Inc.; Pfizer, Inc; *Sanofi US; *Seattle Genetics; *Spectrum Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; St. Baldrick’s Foundation; *Sunesis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; Swedish Orphan Biovitrum, Inc.; Takeda Oncology; Telomere Diagnostics, Inc.; University of Minnesota; and *Wellpoint, Inc. The views expressed in this article do not reflect the official policy or position of the National Institute of Health, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) or any other agency of the U.S. Government

*Corporate Members

This publication is funded in part by the Research and Education Program Fund, a component of the Advancing a Healthier Wisconsin endowment at the Medical College of Wisconsin and by KL2TR001438 from the Clinical and Translational Science Award program of the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (D’Souza, A). Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Footnotes

This work was presented in part as an oral presentation at the 58th American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting in San Diego, CA on December 5th, 2016.

Author contributions:

Conception and design: Jeffrey Schriber, Parameswaran Hari, Kwang Woo Ahn, Anita D’Souza.

Collection and assembly of data: Jeffrey Schriber, Parameswaran Hari, Kwang Woo Ahn, Mingwei Fei, Anita D’Souza

Data analysis and interpretation: All authors

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval: All authors

Conflicts of interests: none

References

- 1.Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, et al. Autologous Transplantation for Multiple Myeloma in the Era of New Drugs: A Phase III Study of the Intergroupe Francophone Du Myelome (IFM/DFCI 2009 Trial) Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology. 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. The New England journal of medicine. 2014;371(10):895–905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1402888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cavo M, Palumbo A, Zweegman S, et al. 2016 American Society of Clinical Oncology. Chicago: 2016. Upfront autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT) versus novel agent-based therapy for multiple myeloma (MM): A randomized phase 3 study of the European Myeloma Network (EMN02/HO95 MM trial) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. The lancet oncology. 2015;16(16):1617–1629. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(15)00389-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.NCCN Guidelines Version 1.2017. Multiple Myeloma. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Al-Hamadani M, Hashmi SK, Go RS. Use of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation as initial therapy in multiple myeloma and the impact of socio-geo-demographic factors in the era of novel agents. American journal of hematology. 2014;89(8):825–830. doi: 10.1002/ajh.23753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Warren JL, Harlan LC, Stevens J, Little RF, Abel GA. Multiple myeloma treatment transformed: a population-based study of changes in initial management approaches in the United States. Journal of clinical oncology: official journal of the American Society of Clinical Oncology. 2013;31(16):1984–1989. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.46.3323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Costa LJ, Huang JX, Hari PN. Disparities in utilization of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for treatment of multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21(4):701–706. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2014.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hari PN, Majhail NS, Zhang MJ, et al. Race and outcomes of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2010;16(3):395–402. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joshua TV, Rizzo JD, Zhang MJ, et al. Access to hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: effect of race and sex. Cancer. 2010;116(14):3469–3476. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pulte D, Redaniel MT, Brenner H, Jansen L, Jeffreys M. Recent improvement in survival of patients with multiple myeloma: variation by ethnicity. Leukemia & lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1083–1089. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.827188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ailawadhi S, Aldoss IT, Yang D, et al. Outcome disparities in multiple myeloma: a SEER-based comparative analysis of ethnic subgroups. British journal of haematology. 2012;158(1):91–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2012.09124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gay F, Cerrato C, Hajek R, et al. Impact of Autologous Transplantation Vs. Chemotherapy Plus Lenalidomide in Newly Diagnosed Myeloma According to Patient Prognosis: Results of a Pooled Analysis of 2 Phase III Trials. Annual Meeting of the American Society of Hematology; 2014; San Francisco. [Google Scholar]

- 14.SEER Data, 1973–2011. 2013 http://seercancergov/data/

- 15.Bhatnagar V, Wu Y, Goloubeva OG, et al. Disparities in black and white patients with multiple myeloma referred for autologous hematopoietic transplantation: a single center study. Cancer. 2015;121(7):1064–1070. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fiala MA, Finney JD, Stockerl-Goldstein KE, et al. Re: Disparities in Utilization of Autologous Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation for Treatment of Multiple Myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2015;21(7):1153–1154. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health-Care. Institute of Medicine; 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mayberry RM, Mili F, Ofili E. Racial and ethnic differences in access to medical care. Med Care Res Rev. 2000;57(Suppl 1):108–145. doi: 10.1177/1077558700057001S06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Costa LJ, Zhang MJ, Zhong X, et al. Trends in utilization and outcomes of autologous transplantation as early therapy for multiple myeloma. Biology of blood and marrow transplantation: journal of the American Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation. 2013;19(11):1615–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2013.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.United States Census. 2010 https://wwwcensusgov/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.