Abstract

Resident microbes of the human body, particularly the gut microbiota, provide essential functions for the host, and, therefore, have important roles in human health as well as mitigating disease. It is difficult to study the mechanisms by which the microbiota affect human health, especially at a systems-level, due to heterogeneity of human genomes, the complexity and heterogeneity of the gut microbiota, the challenge of growing these bacteria in the laboratory, and the lack of bacterial genetics in most microbiotal species. In the last few years, the interspecies model of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and its bacterial diet has proven powerful for studying host-microbiota interactions, as both the animal and its bacterial diet can be subjected to large-scale and high-throughput genetic screening. The high level of homology between many C. elegans and human genes, as well as extensive similarities between human and C. elegans metabolism, indicates that the findings obtained from this interspecies model may be broadly relevant to understanding how the human microbiota affects physiology and disease. In this review, we summarize recent systems studies on how bacteria interact with C. elegans and affect life history traits.

Introduction

Humans are inhabited by microorganisms that altogether form our microbiota. Most of these microbes are harmless bacteria that, in fact, provide great benefits to human physiology and health. For instance, the human gut microbiota aides in the digestion of complex vegetables by breaking down fibers and producing short chain fatty acids propionate and butyrate [1]. The microbiota also provides essential micronutrients such as vitamins [2]. In addition, the microbiota plays a plethora of complex roles in human development, metabolism, immunity and lifespan [3–5]. The importance of the microbiota is underscored by the discoveries that its disruption is correlated with a broad range of diseases, including obesity, insulin resistance that is a precursor to type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, autoimmune disorders, autism, neurodevelopmental diseases, inflammatory diseases, cancer and aging [6–9]. Therefore, a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms that govern different types of human-microbiota interactions will likely provide important steps toward utilizing or perturbing the microbiota to support health and treat disease.

Studying the mechanisms by which bacteria affect human physiology at a systems-level is challenging because the human genome, diet and microbiota are highly heterogeneous, and many known human microbiota species are difficult to propagate and manipulate in the laboratory. Thus, large-scale genetic screens with the human microbiota are not yet feasible, even using mammalian model organisms.

The nematode Caenorhabditis elegans and its bacterial diet can be used to rapidly gain broad systems-level and deep mechanistic insights into bacterial effects on host physiology. We refer to this as an “interspecies model” because both the animal and the bacteria it eats are genetically tractable. Here, we summarize recent findings obtained with this interspecies model in both the laboratory and in the wild that demonstrate its utility in examining host-microbiota interactions.

The nematode C. elegans

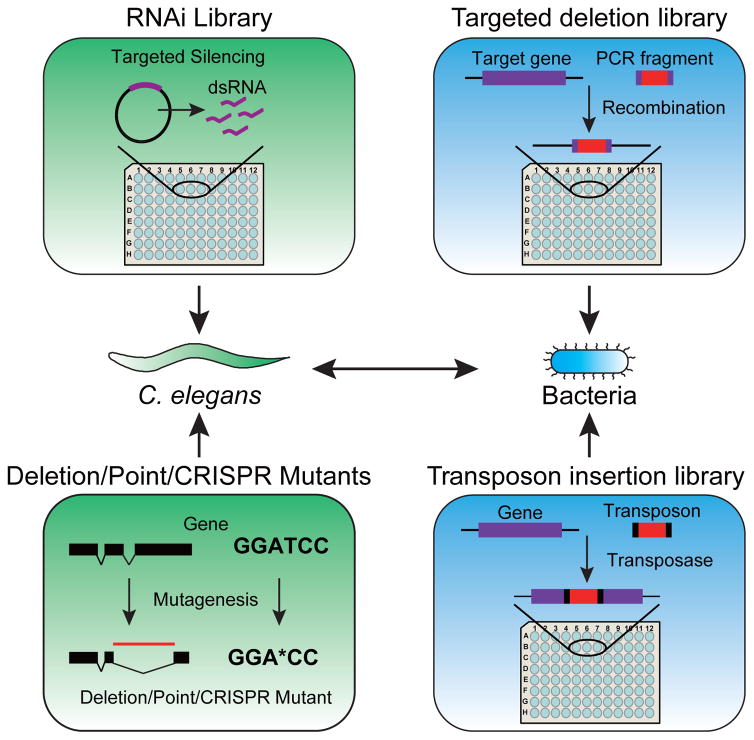

C. elegans is a free-living nematode with a short developmental cycle of about three days and a lifespan of approximately two weeks. It is easy and cost-efficient to culture C. elegans in the laboratory as it can be maintained at a range of temperatures from 15°C to 25°C and needs no special animal facility for growth. C. elegans has a simple body plan of ~1,000 somatic cells, the identity of which is invariant and known [10]. The transparent body of the animal enables the phenotypic characterization of tissues and cells. In addition, the use of fluorescent protein reporters allows researchers to monitor gene expression in living animals [11–15]. Much of basic C. elegans biology, including metabolism, is highly conserved in human, and an estimated 50% of C. elegans genes have clear orthologs in humans [16–18]. Finally, C. elegans can be subjected to forward genetics in which a phenotype is linked to a gene after mutagenizing the genome and whole genome sequencing can be used to identify the causal mutation, and to reverse genetic screens that allow the assignment of phenotypes to individual genes, for instance by RNA interference (RNAi). Genetic resources for C. elegans include publicly available gene deletion, point mutant, and CRISPR mutant strains that can be obtained through the Caenorhabditis genetics center (CGC) (Figure 1). Different RNAi libraries are also available, including two genome-scale libraries [19,20], a metabolic gene library [21], and a transcription factor library [22].

Figure 1.

C. elegans and its bacterial diet are both tractable model organisms for studying host-microbiota interactions at a systems-level. C. elegans phenotypes (green) can be screened by RNAi-mediated knock down libraries, or by examining collections of deletion, point, or CRISPR mutants. Bacterial mutant libraries (blue) for certain strains are available from targeted deletion or transposon insertion collections.

C. elegans is a bacterivore that can grow and reproduce on a variety of bacterial diets, including bacteria found in the human microbiota such as Escherichia coli. In fact, the diet most widely used for C. elegans in the laboratory is an E. coli strain called OP50. For reverse genetic screens, RNAi libraries have only been generated in another E. coli strain, HT115, thus generally limiting the use of RNAi to study bacterial effects on host phenotypes [19,20]. Recently, however, an E. coli OP50 RNAi-compatible strain has been generated expanding the possibilities of performing RNAi in C. elegans with different E. coli strains [23*]. Finally, other bacteria can be mixed in low dilutions with E. coli HT115, but still confer a particular phenotype [24*]. In such cases the E. coli HT115 RNAi resources can be used by simply adding a small amount of the relevant other bacteria [25*].

Bacterial mutant collections

Mutant libraries have been generated for several bacterial species that can be fed to C. elegans. A mutant library can be made either by recombination, which generates a precise gene deletion, or by using randomized transposon-based mutagenesis in which a transposon was inserted in an unknown location in the genome (Figure 1).

The most widely used bacterial mutant library is known as the E. coli Keio deletion collection [26]. This collection contains 3,985 strains each of which harbors a deletion in a single non-essential gene and this collection covers 93% of all annotated genes in this strain. Transposon-based mutagenesis has been used to create mutant strain collections for Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 [27], Comamonas aquatica DA1877 [28**] and E. coli OP50 [29*]. The P. aeruginosa PAO1 library contains more than 30,000 clones and was converted into an organized collection of non-redundant mutants that covers 88% of 5,570 predicted genes [30]. Comamonas DA1877 genome sequencing led to a predicted ~4,000 genes, and the deletion library contains 5,760 mutants. Several genes are represented by independent mutant clones and therefore, this library does not represent a genome-scale, complete deletion collection [28**]. For the laboratory C. elegans food source, E. coli OP50, a library comprising about 2,000 mutants was also generated by transposon mutagenesis [29*].

There are several advantages and disadvantages with regards to constructing and using precise deletion compendia versus random transposon-based mutant collections. The main advantage of using directed deletion libraries is that they are comprehensive, provide complete loss-of-function alleles, and provide a direct link between mutant and the identity of the gene knockout due to the known location of each mutant in the compendium. Disadvantages of constructing such a library include the need for costly primer pairs for each gene and the labor-intensive process of strain generation and verification. Advantages of random libraries include the low cost and relative ease of generation. However, with such libraries, the identity of the genes mutated need to be determined by PCR amplification and sequencing. Further, random mutagenesis may result in partial loss of function alleles, the phenotypes of which may be more difficult to interpret. Finally, depending on the size of the library, only a subset of genes is likely covered.

The natural microbiome of C. elegans

Bacteria are the major dietary source of nutrition for C. elegans. In the wild, live bacteria can also be found in the animal’s gut [31,32]. Advances in high-throughput sequencing of 16S ribosomal DNA to define bacterial species, together with worldwide sample collection, has facilitated the characterization of the composition of microbes digested by C. elegans in the wild. Several recent studies have contributed to our understanding of the natural diet and microbiota of C. elegans. These studies performed systematic sequencing of the gut bacteria from animals grown in natural-like environments made of soil and rotting fruits [33], and nematodes isolated from natural habitats [34**]. Although there are variations in the composition of the microbiota, and not all of the dominant microbes detected in these studies are the same, broad trends exist, particularly at the phylum level (Figure 2). A high abundance of Enterobacteriace, Pseudomonadaceae, Xanthomonadaceae and Sphingobacteriaceae was found in different studies using different methods, which indicates that C. elegans carries a microbiome that can be comprised of different species.

Figure 2.

The structure of the native microbiome in C. elegans. The most abundant phyla and families are indicated. Phyla are represented by color and families are represented by name. This figure was produced with data from [34].

Bacterial effects on C. elegans life history traits, pathogen resistance and behavior

Bacteria can interact with C. elegans in different ways. First, bacteria serve as a natural food source. Bacterial diets supply the animal with macronutrients such as carbohydrates, fats and proteins to support the animal’s growth and reproduction. In addition, bacteria provide essential micronutrients such as vitamins and cofactors. Finally, bacteria can be pathogenic to C. elegans.

In the laboratory, C. elegans fed different bacterial diets can exhibit remarkable differences in life history traits such as developmental rate, fecundity and life span. For instance, when fed Comamonas aquatica DA1877, C. elegans developed faster, exhibited reduced fecundity and a shorter lifespan compared to animals fed the E. coli OP50 diet [24*]. Interestingly, mixing only a very small amount of Comamonas aquatica DA1877 into E. coli OP50 was sufficient to exert developmental acceleration and reduce fecundity, demonstrating that Comamonas aquatica DA1877 produces a dilutable metabolite that modulates the animal’s life history traits.

C. elegans have been fed individual bacteria isolated from wild habitats. Of all bacteria tested, ~80% supported robust nematode growth, while ~20% impaired growth and induced a stress reporter [35]. Strikingly, mixing the harmful bacteria at low ratios with the standard laboratory diet of E. coli OP50 was detrimental to C. elegans growth, indicating that the harmful bacteria are not merely nutritionally deficient, but rather that they may produce toxins that suppresses C. elegans growth.

Certain bacteria can also protect C. elegans from microbial pathogenicity. For instance, C. elegans fed B. subtilis GS67 (GS67) showed strong resistance to the pathogenic effects of B. thuringiensis DB27 (DB27) [36]. GS67 can inhibits growth of DB27 directly and also reduce the colonization of DB27 in C. elegans intestine. A GS67 mutant defective in fengycin production lost inhibition against DB27 and was unable to protect C. elegans from DB27, indicating that fengycin may mediate inhibition of pathogens and C. elegans protection. Further, animals grown on B. megaterium and P. mendocina both show protection to pathogenic P. aeruginosa compared to animals grown on E. coli [37]. B. megaterium and P. mendocina increase C. elegans resistance to infection through distinct mechanisms. The ability of B. megaterium to enhance infection resistance was linked to its effects on reproduction, while P. mendocina functions by activating the p38-dependent MAP kinase pathway to prime the C. elegans innate immune system [37].

The C. elegans natural microbiome can also protect the nematode from fungal pathogens [34**]. For instance, Pseudomonas MYb11 isolated from wild C. elegans strains impaired fungal growth in comparison to E. coli. These studies have provided important first insights into how bacteria affect C. elegans life history traits and pathogen resistance.

Bacterial metabolites that modulate C. elegans life history traits

Bacterially produced metabolites that have been reported to modulate C. elegans life history traits include nitric oxide, folate, and vitamin B12. Nitric oxide is a diffusible signaling molecule that is produced by some bacteria but not by the nematode. Feeding C. elegans nitric oxide-deficient B. subtilis shortens the animal’s lifespan, while exogenous supplementation of nitric oxide results in an increase in lifespan. Nitric oxide-mediated lifespan extension may function through DAF-16 and HSF-1, which induce aging-related genes and an anti-stress response [38].

Folate, or vitamin B9, plays an important role in nucleotide biosynthesis, the salvage of methionine from homocysteine, and the generation of methyl donors used in various metabolic reactions [39]. A serendipitously isolated E. coli HT115 mutant that is deficient in the 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase-encoding gene aroD was found to extend C. elegans lifespan [40**]. The aroD-encoded enzyme is involved in the synthesis of aromatic compounds, including folates. Adding the folate precursor para-aminobenzoic acid (PABA) to aroD mutants reversed the lifespan increase in C. elegans, suggesting that decreased E. coli folate from this mutant bacterial diet is the major cause of the increased C. elegans lifespan [40**]. Interestingly, drugs inhibiting E. coli folate synthesis also increased C. elegans lifespan [40**]. A follow-up study identified two more genes involved in E. coli folate synthesis as effecting C. elegans longevity [41**]. These findings indicated that folate is required by E. coli, rather than by C. elegans, to modulate the animal’s lifespan.

Bacterial genetics revealed that the micronutrient provided by the Comamonas aquatica DA1877 diet described above is vitamin B12 [28**], which is exclusively synthesized by a minority of bacterial species [42]. Vitamin B12 is an essential micronutrient for both humans and C. elegans, but is dispensable for other model organisms such as yeasts, flies and plants. Vitamin B12 is a critical cofactor for two metabolic enzymes: methylmalonyl-CoA mutase, which is involved in the breakdown of propionate, and methionine synthase, which converts homocysteine into methionine in the methionine/S-adenosylmethionine cycle [43]. In C. elegans, genetically perturbing the canonical propionate breakdown pathway mimics vitamin B12 depletion [25*]. However, it is clear from more than four decades of C. elegans research that nematodes can be maintained on low vitamin B12 diets such as E. coli OP50. Recently, it has been discovered that C. elegans can grow on low vitamin B12 conditions because, under such conditions, it transcriptionally activates a propionate shunt, thereby preventing the toxic buildup of this metabolite [21].

Bacterial metabolites can also influence the C. elegans response to pathogenic microbes. For instance, two secondary metabolites produced by P. aeruginosa, phenazine-1-carboxamide and pyochelin, can activate a G protein-signaling pathway in C. elegans chemosensory neuron, and induce expression of DAF-7/TGF-β, which activates the canonical TGF-β signaling pathway in C. elegans interneurons, thereby promoting the animal to seek environments with higher oxygen levels and avoid pathogens [44].

Bacterial respiration affects C. elegans life history traits

More than 10 years ago, it was found that C. elegans fed E. coli GD1, which has reduced levels of coenzyme Q, have a prolonged life span [45]. Coenzyme Q is an essential component of the respiratory chain in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes [46]. Remarkably, however, C. elegans life span extension produced by feeding GD1 was found not to be due to a lack of coenzyme Q, since adding exogenous coenzyme Q to the animal did not reverse the phenotype [47]. Thus, this is a second example, with folate described above, where the gene found initially can be misleading with regard to phenotypic modulation of C. elegans life history traits. Lacking coenzyme Q causes compromised respiration in the GD1 strain, suggesting that reduced bacterial respiration may affect C. elegans. Indeed, a deletion in another E. coli respiratory chain gene, atpA, also confers a robust life span extension in C. elegans [48]. Respiration-deficient E. coli proliferates slowly compared to wild-type E. coli, and it is known that bacterial proliferation inside the animal influences C. elegans life span [49]. Thus, C. elegans life span may be extended by certain mutants because they do not grow as well as wild type bacteria. E. coli cyoA mutants, which are also deficient in respiration, cause developmental delay when fed to C. elegans. This delay is thought to be caused by excessive reactive oxygen species produced by cyoA that induce a mitochondrial stress response in C. elegans and thereby affects development [29*]. These studies indicate that different components of the bacterial respiratory chain affect C. elegans development and life span.

Conclusions and future perspectives

The interspecies systems biology model of C. elegans and its bacterial diet has proven to be powerful for the elucidation of the interactions between microbes and animals, and the mechanisms involved. Moving forward, it will be important to decipher precisely how bacterial metabolic networks interact with C. elegans metabolic and gene regulatory networks. Such studies will be greatly facilitated by the recently reconstructed C. elegans metabolic network, called iCEL1273, that can be combined with mathematical flux balance analysis to computationally model C. elegans metabolism under different nutritional or environmental conditions [50**]. In the future, combining C. elegans network with bacterial metabolic networks, such as E. coli [51], B. subtilis [52], P. aeruginosa PAO1 [53], Lactococcus lactis [54] and human gut microbiota [55], will provide a stepping stone toward the deep mechanistic understanding of how bacteria affect C. elegans life history traits.

Table 1.

The effects of various bacterial diets on C. elegans and the known metabolites involved in these effects. Bacterial diet effect is relative to E. coli OP50.

| Bacterial strain | Metabolite Involved | Effect | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| C. aquatica DA1877 | Vitamin B12 | Accelerated growth | 21, 24, 25, 28 |

| B. subtilis Δnos | Nitric oxide | Decreased lifespan | 38 |

| E. coli HT115 aroD | Folate | Increased lifespan | 40, 41 |

| E. coli GD1 | Co-enzyme Q | Increased lifespan | 45, 47, 48 |

| E. coli OP50 cyoA | Decelerated growth | 29 | |

| B. subtilis GS67 | Fengycin | Anti-pathogen | 36 |

| P. mendocina | Anti-pathogen | 37 | |

| B. megaterium | Anti-pathogen | 37 | |

| Pseudomonas MYb11 | Anti-fungal | 34 |

Highlights.

C. elegans and its bacterial diet is an excellent model system for mammalian host-microbiota interactions.

C. elegans carries a distinct and species-rich microbiome.

Metabolites produced by bacteria modulate C. elegans life history traits.

Bacterial respiration affects C. elegans development and life span.

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Walhout laboratory for discussions and critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health grants DK068429 and GM082971 to A.J.M.W.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

* of special interest

** of outstanding interest

- 1.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Backhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165:1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Biesalski HK. Nutrition meets the microbiome: micronutrients and the microbiota. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2016;1372:53–64. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sommer F, Backhed F. The gut microbiota--masters of host development and physiology. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2013;11:227–238. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Functional interactions between the gut microbiota and host metabolism. Nature. 2012;489:242–249. doi: 10.1038/nature11552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rooks MG, Garrett WS. Gut microbiota, metabolites and host immunity. Nat Rev Immunol. 2016;16:341–352. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell. 2012;148:1258–1270. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Belkaid Y, Hand TW. Role of the microbiota in immunity and inflammation. Cell. 2014;157:121–141. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.03.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boulange CL, Neves AL, Chilloux J, Nicholson JK, Dumas ME. Impact of the gut microbiota on inflammation, obesity, and metabolic disease. Genome Med. 2016;8:42. doi: 10.1186/s13073-016-0303-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wu H, Tremaroli V, Backhed F. Linking microbiota to human diseases: a systems biology perspective. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2015;26:758–770. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2015.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chalfie M, Tu Y, Euskirchen G, Ward WW, Prasher DC. Green Fluorescent Protein as a marker for gene expression. Science. 1994;263:802–805. doi: 10.1126/science.8303295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hunt-Newbury R, Viveiros R, Johnsen R, Mah A, Anastas D, Fang L, Halfnight E, Lee D, Lin J, Lorch A, et al. High-throughput in vivo analysis of gene expression in Caenorhabditis elegans. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e237. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ritter AD, Shen Y, Bass JF, Jeyaraj S, Deplancke B, Mukhopadhyay A, Xu J, Driscoll M, Tissenbaum HA, Walhout AJ. Complex expression dynamics and robustness in C. elegans insulin networks. Genome research. 2013;23:954–965. doi: 10.1101/gr.150466.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez NJ, Ow MC, Reece-Hoyes J, Ambros V, Walhout AJ. Genome-scale spatiotemporal analysis of Caenorhabditis elegans microRNA promoter activity. Genome Res. 2008;18:2005–2015. doi: 10.1101/gr.083055.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grove CA, deMasi F, Barrasa MI, Newburger D, Alkema MJ, Bulyk ML, Walhout AJ. A multiparameter network reveals extensive divergence between C. elegans bHLH transcription factors. Cell. 2009;138:314–327. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Consortium TCeS. Genome sequence of the nematode C. elegans: a platform for investigating biology. Science. 1998;282:2012–2018. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5396.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Harris TW, Chen N, Cunningham F, Tello-Ruiz M, Antoshechkin I, Bastiani C, Bieri T, Blasiar D, Bradnam K, Chan J, et al. WormBase: a multi-species resource for nematode biology and genomics. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:D411–417. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Markaki M, Tavernarakis N. Modeling human diseases in Caenorhabditis elegans. Biotechnol J. 2010;5:1261–1276. doi: 10.1002/biot.201000183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kamath RS, Fraser AG, Dong Y, Poulin G, Durbin R, Gotta M, Kanapin A, Le Bot N, Moreno S, Sohrmann M, et al. Systematic functional analysis of the Caenorhabditis elegans genome using RNAi. Nature. 2003;421:231–237. doi: 10.1038/nature01278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rual J-F, Ceron J, Koreth J, Hao T, Nicot A-S, Hirozane-Kishikawa T, Vandenhaute J, Orkin SH, Hill DE, van den Heuvel S, et al. Toward improving Caenorhabditis elegans phenome mapping with an ORFeome-based RNAi library. Genome Res. 2004;14:2162–2168. doi: 10.1101/gr.2505604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Watson E, Olin-Sandoval V, Hoy MJ, Li C-H, Louisse T, Yao V, Mori A, Holdorf AD, Troyanskaya OG, Ralser M, et al. Metabolic network rewiring of propionate flux compensates vitamin B12 deficiency in C. elegans. Elife. 2016;5 doi: 10.7554/eLife.17670. pii: e17670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.MacNeil LT, Pons C, Arda HE, Giese GE, Myers CL, Walhout AJM. Transcription factor activity mapping of a tissue-specific gene regulatory network. Cell Syst. 2015;1:152–162. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23.Xiao R, Chun L, Ronan EA, Friedman DI, Liu J, Xu XZ. RNAi interrogation of dietary modulation of development, metabolism, behavior, and aging in C. elegans. Cell Rep. 2015;11:1123–1133. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.04.024. The authors genetically engineer the E. coli OP50 strain to make it possible to perform RNAi experimenats in C. elegans fed this strain. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *24.MacNeil LT, Watson E, Arda HE, Zhu LJ, Walhout AJM. Diet-induced developmental acceleration independent of TOR and insulin in C. elegans. Cell. 2013;153:240–252. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *25.Watson E, MacNeil LT, Arda HE, Zhu LJ, Walhout AJM. Integration of metabolic and gene regulatory networks modulates the C. elegans dietary response. Cell. 2013;153:253–266. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2013.02.050. With [24], a diet of C. aquatica verses the standard laboratory diet of E. coli causes changes in C. elegans life history traits independently of insulin signaling, and these changes are cause by modulation of the C. elegans metabolic network. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baba T, Ara T, Hasegawa M, Takai Y, Okumura Y, Baba M, Datsenko KA, Tomita M, Wanner BL, Mori H. Construction of Escherichia coli K-12 in-frame, single-gene knockout mutants: the Keio collection. Mol Sys Biol. 2006;2 doi: 10.1038/msb4100050. 2006 0008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jacobs MA, Alwood A, Thaipisuttikul I, Spencer D, Haugen E, Ernst S, Will O, Kaul R, Raymond C, Levy R, et al. Comprehensive transposon mutant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:14339–14344. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2036282100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **28.Watson E, MacNeil LT, Ritter AD, Yilmaz LS, Rosebrock AP, Caudy AA, Walhout AJM. Interspecies systems biology uncovers metabolites affecting C. elegans gene expression and life history traits. Cell. 2014;156:759–770. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.01.047. An interspecies systems study which demonstrates that a diet of C. aquatica, which produces vitamin B12, causes changes in C. elegans life history traits relative to a diet of E. coli, which does not produce vitamin B12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *29.Govindan JA, Jayamani E, Zhang X, Mylonakis E, Ruvkun G. Dialogue between E. coli free radical pathways and the mitochondria of C. elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:12456–12461. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517448112. Reactive oxygen species produced by bacterial respiration induces the mitochondrial stress response in C. elegans and affects animal development. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liberati NT, Urbach JM, Miyata S, Lee DG, Drenkard E, Wu G, Villanueva J, Wei T, Ausubel FM. An ordered, nonredundant library of Pseudomonas aeruginosa strain PA14 transposon insertion mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:2833–2838. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511100103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Felix MA, Braendle C. The natural history of Caenorhabditis elegans. Curr Biol. 2010;20:R965–969. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2010.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Felix M-A, Duveau F. Population dynamics and habitat sharing of natural populations of Caenorhabditis elegans and C. briggsae. BMC Biology. 2013;10:59. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Berg M, Stenuit B, Ho J, Wang A, Parke C, Knight M, Alvarez-Cohen L, Shapira M. Assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans gut microbiota from diverse soil microbial environments. ISME J. 2016;10:1998–2009. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2015.253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **34.Dirksen P, Marsh SA, Braker I, Heitland N, Wagner S, Nakad R, Mader S, Petersen C, Kowallik V, Rosenstiel P, et al. The native microbiome of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans: gateway to a new host-microbiome model. BMC Biol. 2016;14:38. doi: 10.1186/s12915-016-0258-1. First sequencing and systematic analysis of bacteria isolated from wild C. elegans reveals C. elegans carries a species-rich microbiome and examines the influence of this microbiome on C. elegans. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Samuel BS, Rowedder H, Braendle C, Felix MA, Ruvkun G. Caenorhabditis elegans responses to bacteria from its natural habitats. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:E3941–3949. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1607183113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Iatsenko I, Yim JJ, Schroeder FC, Sommer RJ. B. subtilis GS67 protects C. elegans from Gram-positive pathogens via fengycin-mediated microbial antagonism. Curr Biol. 2014;24:2720–2727. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2014.09.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Montalvo-Katz S, Huang H, Appel MD, Berg M, Shapira M. Association with soil bacteria enhances p38-dependent infection resistance in Caenorhabditis elegans. Infect Immun. 2013;81:514–520. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00653-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gusarov I, Gautier L, Smolentseva O, Shamovsky I, Eremina S, Mironov A, Nudler E. Bacterial nitric oxide extends the lifespan of C. elegans. Cell. 2013;152:818–830. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.12.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nazki FH, Sameer AS, Ganaie BA. Folate: metabolism, genes, polymorphisms and the associated diseases. Gene. 2014;533:11–20. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2013.09.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **40.Virk B, Correia G, Dixon DP, Feyst I, Jia J, Oberleitner N, Briggs Z, Hodge E, Edwards R, Ward J, et al. Excessive folate synthesis limits lifespan in the C. elegans: E. coli aging model. BMC Biology. 2012;10:67. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-10-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **41.Virk B, Jia J, Maynard CA, Raimundo A, Lefebvre J, Richards SA, Chetina N, Liang Y, Helliwell N, Cipinska M, et al. Folate Acts in E. coli to Accelerate C. elegans Aging Independently of Bacterial Biosynthesis. Cell Rep. 2016;14:1611–1620. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.01.051. Together with [40], this paper describes how the inhibition of E. coli folate synthesis increases C. elegans lifespan. Folate synthesis is required by E. coli, but not by C. elegans, to modulate the animal’s lifespan. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Roth JR, Lawrence JG, Bobik TA. Cobalamin (coenzyme B12): synthesis and biological significance. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1996;50:137–181. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.50.1.137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Banerjee R, Ragsdale SW. The many faces of vitamin B12: catalysis by cobalamin-dependent enzymes. Ann Rev Biochem. 2003;72:209–247. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.72.121801.161828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Meisel JD, Panda O, Mahanti P, Schroeder FC, Kim DH. Chemosensation of bacterial secondary metabolites modulates neuroendocrine signaling and behavior of C. elegans. Cell. 2014;159:267–280. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Larsen PL, Clarke CF. Extension of life-span in Caenorhabditis elegans by a diet lacking coenzyme Q. Science. 2002;295:120–123. doi: 10.1126/science.1064653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Laredj LN, Licitra F, Puccio HM. The molecular genetics of coenzyme Q biosynthesis in health and disease. Biochimie. 2014;100:78–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Saiki R, Lunceford AL, Bixler T, Dang P, Lee W, Furukawa S, Larsen PL, Clarke CF. Altered bacterial metabolism, not coenzyme Q content, is responsible for the lifespan extension in Caenorhabditis elegans fed an Escherichia coli diet lacking coenzyme Q. Aging Cell. 2008;7:291–304. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2008.00378.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gomez F, Saiki R, Chin R, Srinivasan C, Clarke CF. Restoring de novo coenzyme Q biosynthesis in Caenorhabditis elegans coq-3 mutants yields profound rescue compared to exogenous coenzyme Q supplementation. Gene. 2012;506:106–116. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Portal-Celhay C, Bradley ER, Blaser MJ. Control of intestinal bacterial proliferation in regulation of lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:49. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **50.Yilmaz LS, Walhout AJ. A Caenorhabditis elegans genome-scale metabolic network model. Cell Syst. 2016;2:297–311. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2016.04.012. The first genome-scale reconstruction of the C. elegans metabolic network starting with a systematic annotation of metabolic genes enables predictions of gene essentiality and the unraveling of the mechanisms of different nutrient contributions influencing the animal’s physiology. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Orth JD, Conrad TM, Na J, Lerman JA, Nam H, Feist AM, Palsson BO. A comprehensive genome-scale reconstruction of Escherichia coli metabolism--2011. Mol Sys Biol. 2011;7:535. doi: 10.1038/msb.2011.65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oh YK, Palsson BO, Park SM, Schilling CH, Mahadevan R. Genome-scale reconstruction of metabolic network in Bacillus subtilis based on high-throughput phenotyping and gene essentiality data. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:28791–28799. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703759200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Oberhardt MA, Palsson BO, Papin JA. Applications of genome-scale metabolic reconstructions. Mol Syst Biol. 2009;5:320. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Flahaut NA, Wiersma A, van de Bunt B, Martens DE, Schaap PJ, Sijtsma L, Dos Santos VA, de Vos WM. Genome-scale metabolic model for Lactococcus lactis MG1363 and its application to the analysis of flavor formation. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;97:8729–8739. doi: 10.1007/s00253-013-5140-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shoaie S, Nielsen J. Elucidating the interactions between the human gut microbiota and its host through metabolic modeling. Front Genet. 2014;5:86. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2014.00086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]