Abstract

People with type 2 diabetes are at increased risk of bladder cancer. Pioglitazone is said to increase it further, although published evidence is mixed. We conducted a meta-analysis to determine if any link between the use of pioglitazone and an increased risk of bladder cancer can be found. A comprehensive literature search was conducted through electronic databases as well as registries for data of clinical trials to identify studies that investigate the effect of pioglitazone on bladder cancer in diabetic patients. We used the risk ratio (RR) and the hazard ratio (HR) provided by the studies to illustrate the risk of occurrence of bladder cancer in the experimental group compared to that in the control group. Fourteen studies using RR and 12 studies using HR were included in the analysis. The overall RR was 1.13 with 95% CI (0.96–1.33) with low heterogeneity among the studies using RR, suggesting that no connection exists between use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder malignancy. The summary HR was 1.07 (0.96–1.18) allowing us to affirm that there is no link between long-term use of pioglitazone and bladder cancer. Our results support the hypothesis of no difference in the incidence of bladder cancer among the pioglitazone group and the nonuser group. Our conclusion is that the explanation of hypothetically increased risk of bladder malignancy should be attributed to other factors.

Funding : Tchaikapharma High Quality Medicines Inc.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13300-017-0273-4) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Bladder cancer, Hazard ratio, Pioglitazone, Type 2 diabetes, Risk ratio

Introduction

Pioglitazone belongs to the thiazolidinediones, a class of antidiabetic drugs that exert their action by binding to the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR-γ) [1]. It was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1999 and European Medicines Agency (EMA) in 2000 for the treatment of type 2 diabetes as monotherapy or in combination with metformin, sulfonylurea, or insulin [2]. It is known to successfully reduce HbA1c with an antihyperglycemic effect similar to that of metformin and sulfonylureas [3–5]. Pioglitazone improves insulin sensitivity, preserves β-cell function in diabetic patients, and is believed to have a favorable effect on the lipid profile [6]. It has a manageable safety profile with beneficial effect on coronary and peripheral vasodilation and with minimal improvement of blood pressure [7]. Nevertheless, it is associated with weight gain and peripheral edema [8].

Bladder cancer is the fourth and 11th most common cancer type in men and women in developed countries, respectively [9]. People with type 2 diabetes are at increased risk of several types of cancer, including a 40% increased risk of bladder cancer compared with those without diabetes. Additional risk factors for bladder cancer include increased age, male sex, smoking, occupational and environmental exposures, and urinary tract disease [10, 11].

Evidence linking the use of pioglitazone to the increased risk of bladder cancer is mixed. The first signals for a possible association of pioglitazone use and bladder cancer arose from a preclinical study included in the licensing applications which reported a higher number of urothelial hyperplasia in a rat population and malignant tumors in the urinary bladder in male rats treated with pioglitazone [12]. However, a number of studies later proved that this is a rat-specific phenomenon and does not pose a urinary bladder cancer risk to humans [13–15].

PROactive is the first trial that raised the question of a possible increase in bladder cancer risk with pioglitazone use. In the whole cohort of PROactive, the comparative incidence of all malignancies was similar. More cases of bladder neoplasm (14/2605 vs 6/2633) were observed in the pioglitazone versus placebo arms of the study [16, 17]; however, comparative analysis shows statistical insignificance with p = 0.069. When the fact that one patient in the placebo arm is incorrectly diagnosed is taken into account, the difference becomes significant, p = 0.036. An independent expert committee reviewed the 20 bladder cancer cases and concluded that 11 tumors that occurred within 1 year of randomization (eight in pioglitazone vs. three in placebo) could not plausibly be related to the treatment [17]. The remaining six cases with pioglitazone and three with placebo could not produce statistical significance (χ 2 1.034, p = 0.309).

A report by Hillaire-Buys and Faillie [18] and based on the analysis of randomized controlled trials [12] confidently claims to have determined that pioglitazone increases the risk of bladder cancer. At the same time Erdmann et al. [19] presenting the 6-year interim analysis of a 10-year observational follow-up of the PROactive study did not register imbalance between bladder cancer cases in the pioglitazone and placebo groups. This contradictory evidence led us to believe that a meta-analysis of the connection of pioglitazone use and the risk of bladder cancer is a must.

Methods

The rationale of this meta-analysis is to establish whether there is a link between the use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer. A comprehensive literature search was conducted through electronic databases (from 2000 until February 2016) MEDLINE, Scopus, PsyInfo, eLIBRARY.ru, as well as registries for data of clinical trials (http://ClinicalTrials.gov and http://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu) to identify studies that investigate the effect of pioglitazone on bladder cancer in diabetic patients. The following keywords and various combinations were used in the search: pioglitazone, thiazolidinediones, bladder cancer, and placebo. The search was not restricted to articles published in English. Full text articles and abstracts were checked for relevance to the topic and were assessed on the basis of the following inclusion criteria: type of study/trial—epidemiologic, controlled, and randomized; type of subjects included—representatives of the whole population or a specific stratum; access to raw data; eligibility for statistical analysis. If any clarification of results or conclusions was needed, authors were contacted for additional information.

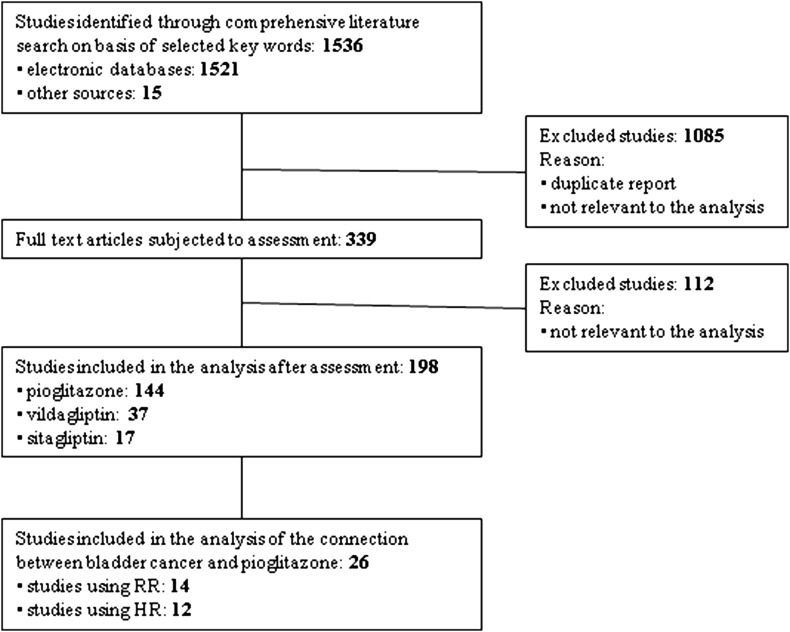

All relevant studies identified were carefully reviewed, sorted, and assessed. Figure 1 depicts the process of selection applied to evaluated studies in order to determine their eligibility for inclusion in the analysis. Extracted data encompassed publication year, study design, population (cases and controls), and RR or HR assessment. Quality of reviewed studies was evaluated, and any comments or conclusions of the authors were also summarized.

Fig. 1.

Study selection process

From each study we obtained the relative association measure and the 95% confidence interval. We used the RR and the HR provided by the studies to illustrate the risk of occurrence of bladder cancer in the experimental group compared to that in the control group and to assess the relative probability of occurrence of bladder cancer in pioglitazone-treated patients after a certain period of time, respectively. For those studies that did not provide RR or HR, we calculated the epidemiological measures as described in Borenstein et al. [20].

We chose the random-effects method as the primary analysis because of the significant heterogeneity of the individual studies. To assess the aforementioned heterogeneity of treatment effect among trials, we used the Cochran Q and the I 2 statistics, where p values of less than 0.10 were used as an indication of the presence of heterogeneity and an I 2 parameter greater than 50% was considered indicative of substantial heterogeneity. The threshold for statistical significance was set at 0.05. Forest plots depict estimated results from the studies included in the analysis and funnel plots are used to evaluate publication bias.

Sensitivity analyses were performed to assess the effect if a given study has been excluded from the analysis set. The influence was estimated by consecutive elimination of each of the studies from the analysis and noting the degree to which the effect size and significance of the treatment effect changed. Calculations are made with language for statistical modeling R and MetaXL macro (add-ins of MSExel).

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Results

Our search returned 1536 titles. Once duplicate reports and studies not relevant to the analysis were excluded, 339 full text articles remained to be subjected to assessment. Of them 26 were included in the analysis of the connection between pioglitazone use and bladder cancer occurrence (Fig. 1).

Assessment of Studies Using RR as the Relative Association Measure

Fourteen studies using RR as the relative association measure were identified and included in the analysis [16, 19, 21–32]. Six of them are retrospective cohort studies [21, 24–27, 29]; four are case–control studies [23, 28, 30, and 31]; two are observational studies [19, 22]; one is multipopulation pooled cumulative exposure analysis [32] and one is the randomized controlled trial PROactive [16]. Nine of the studies did not demonstrate a significantly increased risk of bladder cancer in patients with diabetes treated with pioglitazone compared to nonusers; the others reported significantly increased risk of bladder malignancy. Potential confounders were controlled in most of the studies. All of the studies were assessed in terms of quality of the analysis and eligibility of the statistical analysis.

The PROactive trial randomized 2605 patients to receive pioglitazone titrated from 15 to 45 mg and 2633 to receive placebo in addition to their glucose-lowering drugs and other medications. It was originally published in 2005 [16], but an update with an interim 6-year analysis was presented in 2012 [17]. Its primary endpoint was to ascertain whether pioglitazone reduces macrovascular morbidity and mortality in high-risk patients with type 2 diabetes [16]. Oliveria et al. [21] commented on the risks of colorectal, bladder, liver, pancreatic, and melanoma cancers in users and nonusers of various antidiabetic pharmacotherapies, including thiazolidinediones, while Piccinni et al. [22] analyzed the association between pioglitazone use and bladder cancer through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System database. A 5-year prospective pharmacoepidemiological cohort study included 34,181 users of pioglitazone users and 158,918 control subjects from the Kaiser Permanente Northern California (KPNC) diabetes registry to examine whether pioglitazone use for type 2 diabetes is associated with risk of bladder and ten additional cancers [23]. A population-based study in Taiwan reviewed the National Health Insurance database and investigated the association of pioglitazone and bladder cancer in Asians among 54,928 patients with type 2 diabetes using pioglitazone [24]. A retrospective cohort study analyzed the clinical data of 5079 cancer patients with and without diabetes to assess the correlation between use of antidiabetic agents including pioglitazone and the incidence of bladder cancer [26]. Jin et al. [29] and Kuo et al. [30] investigated whether chronic exposure to relatively low doses of pioglitazone increases risk of bladder cancer in a total of 101,953 control patients and 11,240 pioglitazone-treated patients in Korean hospitals and 259 cases and 1036 controls randomly sampled from National Health Insurance enrollees in Taiwan, respectively.

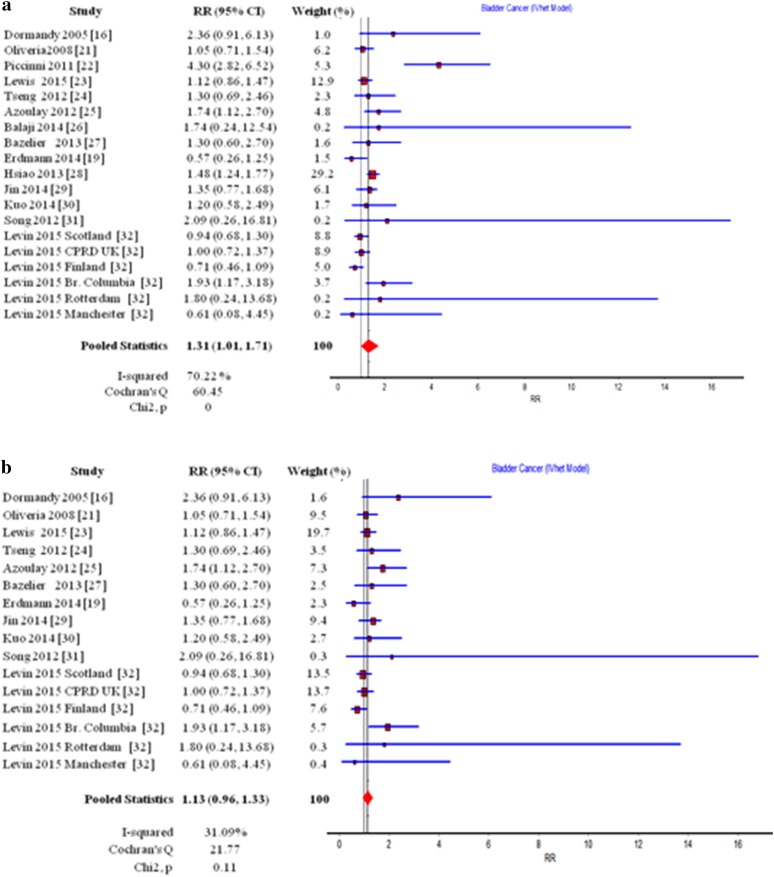

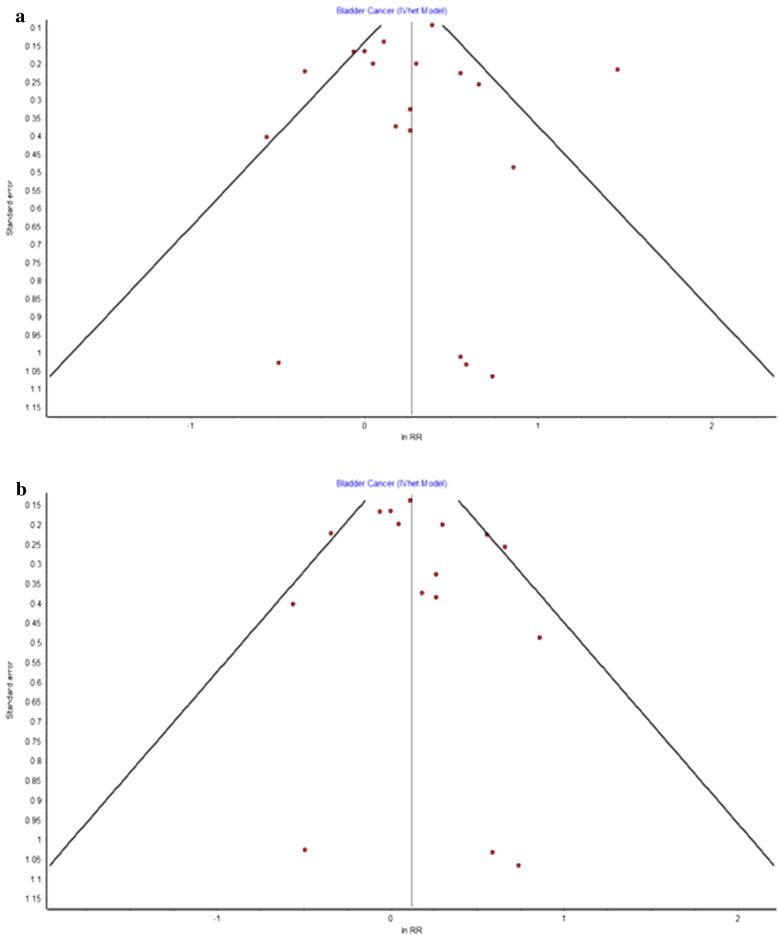

The summary RR for all studies with 95% CI is shown in Fig. 2a. The summary RR was 1.31 (95% CI 1.01–1.71) in a random-effects model and did not provide evidence for the existence of statistically significant increased risk of occurrence of bladder cancer in patients with diabetes using pioglitazone versus nonusers. There is noticeable heterogeneity among these studies with Cochran’s Q = 60.45, p = 0.00 and I 2 = 70%. The funnel plot (Fig. 3a) used to assess the publication bias suggested symmetry of the individual results. At the same time, there are three studies that remain outside of the border of the funnel [22, 26, 28]. They also happen to be the ones estimated to be of low quality (see Table 1).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of studies using RR as the relative association measure: a without estimation of quality, b after studies deemed to be of low quality were excluded

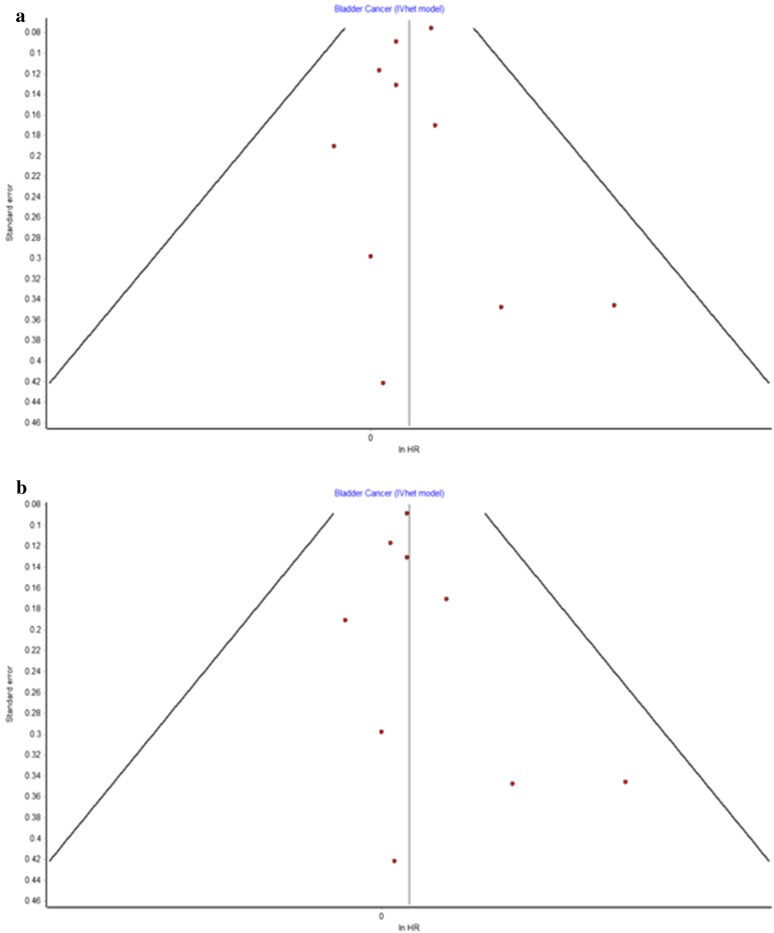

Fig. 3.

Funnel plot of studies using RR as the relative association measure: a without estimation of quality, b after studies deemed to be of low quality were excluded

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies using RR as the relative association measure

| Author, year, study | Type of study | No. of patients | No. of cases of bladder cancer | Risk ratio RR assessment (95% CI) | Quality assessment | Authors’ conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed group | Control group | Exposed group | Control group | |||||

| Dormandy, 2005, PROactive [16] | Prospective, randomized controlled trial | 2605 | 2633 | 14 | 6 | 2.36 (0.91–6.13) | H | Safety profiles of both arms are similar. When bladder cancer cases with different etiology are excluded, there is no connection between pioglitazone and bladder cancer |

| Oliveria, 2008 [21] | Retrospective cohort study using a large US population-based database | 191,223 | 178 | 1.05 (0.71–1.54) | H | Use of thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone included) does not increase the risk of bladder cancer. The adjusted RR is assessed after exclusion of patients on insulin monotherapy | ||

| Piccinni, 2011 [22] | Observational using reports recorded in FDA AERS | 37,841 | 561,244 | 31 | 93 | 4.30 (2.82–6.52) | L | There is significantly increased risk of bladder cancer. The significant problems with the reliability and control of information and possible major shifts in the inferences that are logically implausible should be taken into account |

| Lewis, 2015, KPNC [23] | Cohort and nested case–control analyses; cohorts from Kaiser Permanente Northern California | 464 | 464 | 91 | 81 |

OR 1.18 (0.78–1.80) after adjustment RR 1.12 (0.86–1.47) |

H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Tseng, 2012 [24] | Retrospective cohort study of data from the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan | 2564 | 51,667 | 10 | 155 | 1.30 (0.69–2.46) | M | RR is additionally calculated; the original article employs HR. Use of pioglitazone shows insignificant risk of bladder cancer in comparison with nonuse |

| Azoulay, 2012 [25] | Retrospective cohort study using a nested case–control analysis | 191 | 6508 | 19 | 357 | 1.83 (1.10–3.05) | M | Use of pioglitazone is associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Balaji, 2014 [26] | Retrospective cohort study | 31 | 1077 | 1 | 20 | 1.74 (0.24–12.54) | L | Pioglitazone is highly unlikely to cause bladder cancer |

| Bazelier, 2013 [27] | Population-based cohort study using the Danish National Health Registers | NA | NA | NA | NA | 1.3 (0.6–2.7) | M | There is no evidence that use of pioglitazone is associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Erdmann, 2014, PROactive 6-year-update [19] | Observational multinational multicenter follow-up study of PROactive | 1820 | 1779 | 10 | 17 | 0.57 (0.26–1.25) | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Hsiao, 2013 [28] | Population-based nested case–control using Taiwan’s National Health Insurance Research Database | 3259 | 16,537 | 153 | 523 | 1.48 (1.24–1.77) | L | Use of pioglitazone, especially long-term, is associated with increased risk of bladder cancer. Using the same data Tseng [24] reach exactly the opposite conclusion |

| Jin, 2014 [29] | Retrospective cohort study | 11,240 | 101,953 | 30 | 237 | 1.35 (0.769–1.677) | M | Even though there is no evidence for the following, the authors conclude that risk of bladder cancer can be slightly increased in case of use for more than 6 months |

| Kuo, 2014 [30] | Nested case–control study | 52 | 985 | 15 | 244 | 1.20 (0.58–2.49) OR | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Song, 2012 [31] | Retrospective, matched case–control study | 329 | 658 | 21 | 99 | 2.09 (0.26–16.81) OR | M | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

KPNC Kaiser Permanente Northern California, AERS Adverse Event Reporting System, H high, M medium, L low, OR odds ratio

It is visible from Fig. 2 that the study by Hsiao et al. [28] has the highest weight. When the three studies [22, 26, 28] deemed to be of low quality are excluded from the analysis the situation is visibly altered (Fig. 2b). Heterogeneity among the studies is reduced with Cochran’s Q = 21.77, p = 0.11 and I 2 = 31%. The overall RR is now 1.13 with 95% CI (0.96–1.33) which suggests that no connection exists between use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder malignancy. Since these estimates are based on a significantly larger number of cases than in the individual studies, and include studies that meet the criteria for scientific quality, we can assume that these results are considerably more reliable than those published previously.

Sensitivity Analysis

The results of the sensitivity analyses for all studies regardless of quality and when studies deemed to be of low quality are excluded are summarized and presented in Table 2. In all sensitivity analyses, the use of pioglitazone was not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer, with pooled risk ratios ranging between 1.230 and 1.357 for all studies and between 1.092 and 1.174 when supposed low-quality studies were excluded. It is obvious from the results presented in Table 2 that the subsequent exclusion of each study from the analysis did not lead to a significant change in the pooled RR, suggesting consistency of our findings.

Table 2.

Sensitivity analysis

| Excluded study | For all studies | Low-quality studies excluded | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled RR | LCI 95% | HCI 95% | Cochran Q | χ 2 | I 2 | Pooled RR | LCI 95% | HCI 95% | Cochran Q | χ 2 | I 2 | |

| Dormandy et al. [16] | 1.306 | 0.997 | 1.709 | 58.980 | 0.000 | 71.177 | 1.117 | 0.955 | 1.307 | 19.430 | 0.149 | 27.945 |

| Oliveria et al. [21] | 1.333 | 0.999 | 1.778 | 59.083 | 0.000 | 71.227 | 1.139 | 0.950 | 1.365 | 21.614 | 0.087 | 35.226 |

| Piccinni et al. [22] | 1.230 | 1.039 | 1.455 | 27.977 | 0.045 | 39.236 | Excluded | |||||

| Lewis et al. [23] | 1.345 | 0.990 | 1.826 | 58.894 | 0.000 | 71.134 | 1.133 | 0.939 | 1.366 | 21.762 | 0.084 | 35.666 |

| Tseng [24] | 1.314 | 0.995 | 1.735 | 60.451 | 0.000 | 71.878 | 1.124 | 0.947 | 1.336 | 21.574 | 0.088 | 35.107 |

| Azoulay et al. [25] | 1.295 | 0.976 | 1.718 | 58.804 | 0.000 | 71.091 | 1.092 | 0.937 | 1.273 | 17.781 | 0.217 | 21.262 |

| Balaji et al. [26] | 1.313 | 1.002 | 1.719 | 60.374 | 0.000 | 71.842 | Excluded | |||||

| Bazelier et al. [27] | 1.314 | 0.997 | 1.731 | 60.452 | 0.000 | 71.878 | 1.126 | 0.949 | 1.336 | 21.631 | 0.087 | 35.277 |

| Erdmann et al. [19] | 1.330 | 1.023 | 1.730 | 56.043 | 0.000 | 69.666 | 1.149 | 0.985 | 1.340 | 18.778 | 0.174 | 25.444 |

| Hsiao et al. [28] | 1.250 | 0.954 | 1.638 | 58.010 | 0.000 | 70.695 | Excluded | |||||

| Jin et al. [29] | 1.311 | 0.979 | 1.756 | 60.432 | 0.000 | 71.869 | 1.110 | 0.930 | 1.324 | 20.884 | 0.105 | 32.962 |

| Kuo et al. [30] | 1.316 | 0.998 | 1.734 | 60.392 | 0.000 | 71.851 | 1.128 | 0.950 | 1.340 | 21.740 | 0.084 | 35.604 |

| Song et al. [31] | 1.312 | 1.002 | 1.718 | 60.261 | 0.000 | 71.789 | 1.128 | 0.955 | 1.332 | 21.432 | 0.091 | 34.677 |

| Levin et al. Scotland [32] | 1.357 | 1.019 | 1.807 | 55.960 | 0.000 | 69.621 | 1.163 | 0.975 | 1.388 | 20.330 | 0.120 | 31.137 |

| Levin et al. [32] CPRD UK | 1.349 | 1.008 | 1.806 | 57.420 | 0.000 | 70.394 | 1.152 | 0.961 | 1.382 | 21.122 | 0.099 | 33.719 |

| Levin et al. [32] Finland | 1.356 | 1.043 | 1.765 | 52.230 | 0.000 | 67.452 | 1.174 | 1.013 | 1.361 | 16.936 | 0.260 | 17.338 |

| Levin et al. [32] Br Columbia | 1.294 | 0.981 | 1.707 | 58.089 | 0.000 | 70.734 | 1.094 | 0.945 | 1.267 | 17.102 | 0.251 | 18.136 |

| Levin et al. [32] Rotterdam | 1.313 | 1.002 | 1.719 | 60.359 | 0.000 | 71.835 | 1.128 | 0.955 | 1.333 | 21.563 | 0.088 | 35.073 |

| Levin et al. [32] Manchester | 1.316 | 1.006 | 1.721 | 59.891 | 0.000 | 71.615 | 1.133 | 0.959 | 1.337 | 21.404 | 0.092 | 34.591 |

Assessment of Studies Using HR as the Relative Association Measure

In order to assess the cumulative effect of pioglitazone use and to determine whether there is an increased risk of urinary bladder cancer in case of prolonged use, we analyzed 12 studies using HR as the relative association measure [19, 23, 24, 33–41]. Ten of them are cohort studies with two prospective cohort studies [23, 33] and eight retrospective cohort studies [24, 34, 35, 37–41]. There is one observational study [19] and one case–control study [36]. The eligible 12 publications provided evidence for 881,907 patients with diabetes in total and 8873 cases of bladder cancer among patient groups. The minimum duration of follow-up was 1 year and the maximum was 6.5 years. The cumulative dose of pioglitazone taken by the different subgroups was in the range from 1 to 156,000 mg.

The interim report of the cohort study described by Lewis et al. [23] examined the association between pioglitazone therapy and the risk of bladder cancer using data about 193,099 patients in the KPNC diabetes registry [33]. Fujimoto et al. [34] examined the frequency of bladder cancer in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes in relation to use of pioglitazone among a total of 663 patients identified to be taking pioglitazone. An Indian retrospective cohort study aimed to determine whether pioglitazone is associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer and analyzed 2222 patients divided into two equal groups. It is interesting to point out that there was no evidence of bladder cancer in any of the studied groups [35]. The study by Lee et al. [37] investigated the factors that may link pioglitazone to bladder cancer among 34,970 subjects identified from the National Health Insurance Research Database. Mackenzie et al. [38] explored the relationship between use of one or both thiazolidinediones and angiotensin receptor blockers and incidence of bladder cancer among diabetic patients with diabetes enrolled in Medicare. A large retrospective study, conducted by the French National Fund for health insurance (La Caisse nationale de l’assurance maladie, CNAM), retrieved data on 155,535 pioglitazone users and 1,335,525 control subjects from several French databases [39]. Another retrospective cohort study extracted data from the InVision Data Mart database to evaluate safety data on pioglitazone for several outcomes such as an increased risk of bladder cancer, an increased risk of bone fracture and heterogeneous effects on cardiovascular events, and to examine them in context with each other as well as with insulin [40]. A cohort study using data from the General Practice Research Database aimed to examine whether exposure to pioglitazone use is associated with increased incidence of bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus [41].

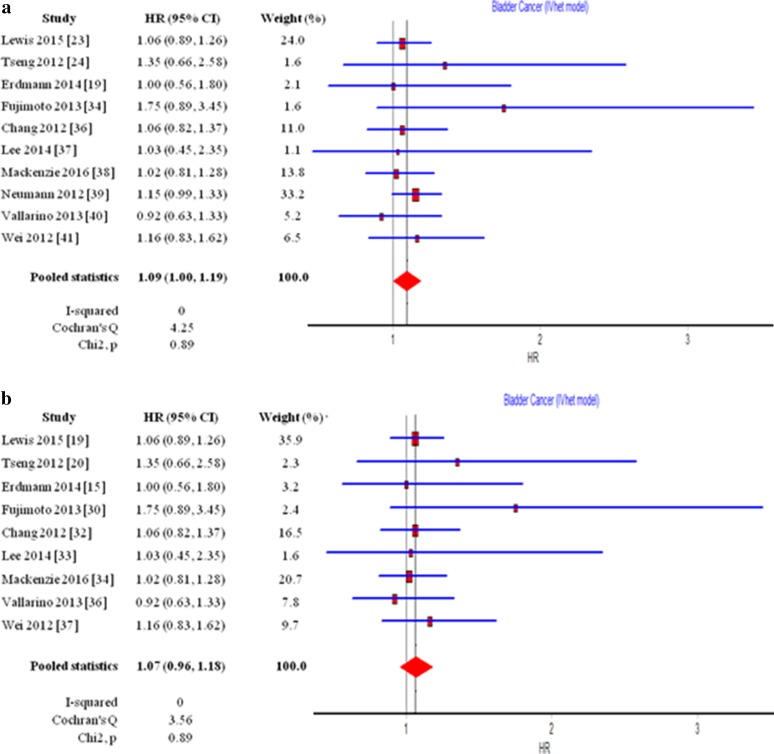

The summary HR for all 12 studies is 1.09 (1.00–1.19) which is on the border of statistical significance (Fig. 4a). The funnel plot (Fig. 5a) shows only slight asymmetry which suggests that there is almost no publication bias. Cochran’s Q of 4.25, p = 0.89, and I 2 = 0% signify the high degree of homogeneity of the different studies. These results, however, cannot help us determine whether there is any connection between the long-term use of pioglitazone and the increase in the chance of developing a bladder malignancy.

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of studies using HR as the relative association measure: a without estimation of quality, b after studies deemed to be of low quality were excluded

Fig. 5.

Funnel plot of studies using HR as the relative association measure: a without estimation of quality, b after studies deemed to be of low quality were excluded

In order to obtain a more definitive result concerning the link between pioglitazone therapy and bladder cancer, we repeated the analysis and this time we took into account the assessment of the quality of the studies which is summarized in Table 3. As it is visible from Fig. 4a, b, the study by Neumann et al. [39] has the highest weight but results summarized in Table 3 show that it is of arguable quality. When it is excluded from the analysis, together with the works of Gupta et al. [35] and Mackenzie et al. [38], which are also deemed to be of low quality, the summary HR for the rest of the studies becomes 1.07 (0.96–1.18). This result allows us to affirm that there is no link between long-term use of pioglitazone and bladder cancer.

Table 3.

Characteristics of studies using HR as the relative association measure

| Author, year, study | Type of study | No. of patients | No. of cases of bladder cancer | Follow-up, years | Hazard ratio assessment (95% CI) | Quality assessment | Authors’ conclusion | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposed group | Control group | Exposed group | Control group | ||||||

| Lewis, 2011, KPNC [33] | Interim analysis on a cohort and nested case–control study | 30,173 | 162,926 | 90 | 791 | 2 | 1.2 (0.9–1.5) | H | Pioglitazone use is not associated with increased risk of bladder cancer. Authors claim that risk is increased by 40% with long-term use (more than 2 years) |

| Lewis, 2015, KPNC [23] | Cohort and nested case–control study; cohorts from Kaiser Permanente Northern California | 34,181 | 158,918 | 186 | 1075 | 2.8 | 1.06 (0.89–1.26) | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Tseng, 2012 [24] | Retrospective cohort study of data from the National Health Insurance database in Taiwan | 2545 | 52,383 | 10 | 155 | 2 | 1.35 (0.66–2.58) | M | Use of pioglitazone shows insignificant risk of bladder cancer in comparison with nonuse |

| Erdmann, 2014 [19], PROactive 6-year-update | Observational multinational multicenter follow-up study of PROactive | 2605 | 2533 | 23 | 22 | 5.8 | 1.00 (0.56–1.80) | H | There is no increased risk with long-term use of pioglitazone |

| Fujimoto, 2013 [34] | Retrospective cohort study | 663 | 20,672 | 9 | 673 | NA | 1.75 (0.89–3.45) | M | Use of pioglitazone shows insignificant risk of bladder cancer in comparison with nonuse |

| Gupta, 2015 [35] | Retrospective cohort study | 1111 | 1111 | 0 | 0 | NA | NA | L | Results are odd. There is not a single bladder cancer case registered |

| Chang, 2012 [36] | Retrospective case–control study | 401 | 7490 | 84 | 1499 | 1 (375 days) | 1.06 (0.82–1.37) | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Lee, 2014 [37] | Retrospective study | 3497 | 31,473 | 12 | 72 | 1 | 1.03 (0.45–2.35) | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

| Mackenzie, 2016 [38] | Retrospective cohort study using Medicare data | 38,091 | 281,999 | 1159 | 1.4 | 1.02 (0.81–1.28) | L | There is no evidence of connection between bladder cancer and pioglitazone | |

| Neumann, 2012 [39] | Retrospective cohort study using data from the French national health insurance information system | 155,535 | 1,335,525 | 175 | 1841 | 6.5 | 1.22 (1.05–1.43) or 1.15 (0.99–1.33) when all patients over 40 are included | L | There is a link between dose and response. The study is badly controlled and does not take into account any confounding covariates |

| Vallarino, 2013 [40] | Retrospective cohort study | 38,588 | 17,948 | 84 | 44 | 2.2 | 0.92 (0.63–1.33) | M | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer. Insulin-treated patients are used as controls |

| Wei, 2012 [41] | Retrospective cohort study | 23,548 | 184,166 | 66 | 803 | 3.2 | 1.16 (0.83–1.62) | H | Use of pioglitazone is not associated with an increased risk of bladder cancer |

H high, M medium, L low, NA not available

Sensitivity Analysis

Summarized results from the sensitivity analysis for all studies using HR as the relative association measure are presented in Table 4. It must be noted that the subsequent exclusion of each study leads to pooled HR ranging from 1.065 to 1.105 for all studies and from 1.059 to 1.078 when low-quality studies are excluded. The consistency of the results is yet another proof that there is no statistically significant increase in the risk of bladder cancer in case of long-term use of pioglitazone from patients with type 2 diabetes.

Table 4.

Sensitivity analysis

| Excluded study | For all studies | Low-quality studies excluded | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pooled HR | LCI 95% | HCI 95% | Cochran Q | χ 2 | I 2 | Pooled HR | LCI 95% | HCI 95% | Cochran Q | χ 2 | I 2 | |

| Lewis et al. [23] | 1.103 | 1.001 | 1.216 | 4.097 | 0.848 | 0.000 | 1.068 | 0.938 | 1.217 | 3.557 | 0.829 | 0.000 |

| Tseng [24] | 1.089 | 1.000 | 1.187 | 3.876 | 0.868 | 0.000 | 1.059 | 0.953 | 1.177 | 3.087 | 0.877 | 0.000 |

| Erdmann et al. [19] | 1.095 | 1.005 | 1.193 | 4.161 | 0.842 | 0.000 | 1.067 | 0.960 | 1.187 | 3.515 | 0.834 | 0.000 |

| Fujimoto et al. [34] | 1.084 | 0.995 | 1.182 | 2.365 | 0.968 | 0.000 | 1.053 | 0.947 | 1.170 | 1.449 | 0.984 | 0.000 |

| Chang et al. [36] | 1.097 | 1.002 | 1.200 | 4.191 | 0.840 | 0.000 | 1.066 | 0.951 | 1.195 | 3.560 | 0.829 | 0.000 |

| Lee et al. [37] | 1.093 | 1.004 | 1.191 | 4.231 | 0.836 | 0.000 | 1.066 | 0.960 | 1.184 | 3.555 | 0.829 | 0.000 |

| Mackenzie et al. [38] | 1.105 | 1.008 | 1.211 | 3.848 | 0.871 | 0.000 | 1.077 | 0.959 | 1.211 | 3.387 | 0.847 | 0.000 |

| Neumann et al. [39] | 1.065 | 0.960 | 1.182 | 3.562 | 0.894 | 0.000 | Excluded | |||||

| Vallarino et al. [40] | 1.103 | 1.011 | 1.204 | 3.392 | 0.907 | 0.000 | 1.078 | 0.968 | 1.202 | 2.920 | 0.892 | 0.000 |

| Wei et al. [41] | 1.088 | 0.997 | 1.188 | 4.120 | 0.846 | 0.000 | 1.056 | 0.946 | 1.178 | 3.285 | 0.857 | 0.000 |

Discussion

In recent years there have been a number of studies and meta-analyses connecting pioglitazone use and the risk of bladder cancer in type 2 diabetes patients [2, 23, 26, 29, 39] with such emphasis on the danger involved that authors and clinicians worldwide have started to recommend that pioglitazone is avoided. Although various other sources have claimed that the apprehension is unfounded, misgivings concerning the use of pioglitazone nevertheless remain.

Our meta-analysis aimed to reinterpret evidence provided by the literature about the risk of bladder malignancy in case of treatment with pioglitazone. We reviewed and evaluated a large number of sources and based our conclusions only on studies we assessed to be of satisfactory quality. Our findings prove, just like other authors have claimed before us [16, 19, 23, 37, 41], that pioglitazone use is not associated with increased odds of developing bladder cancer in patients with type 2 diabetes and the reason behind the rising number of bladder cancer cases should be attributed to other factors.

First of all, it should be noted that a lot of the works testifying to a connection between pioglitazone and blabber cancer risk are observational studies like that of Azoulay et al. [25]. A major disadvantage of these studies is that the characteristics of treatment and comparison groups cannot be well balanced as a result of the nature of the study itself. Azoulay et al. stated that participants prescribed thiazolidinediones (pioglitazone and rosiglitazone) were more likely to be obese, to have ever smoked, and to have uncontrolled diabetes than those who never used any thiazolidinedione, this way setting significant baseline differences among the groups and making it harder to draw a definite conclusion about the connection between pioglitazone and bladder cancer.

The prescription practices of pioglitazone could provide an explanation for the imbalance of baseline characteristics of patients treated with thiazolidinediones. Recommendations from NICE [42, 43] list pioglitazone as third-line therapy for patients already treated with other antihyperglycemic drugs like gliptins, insulin, and insulin analogues. This is yet another confounding factor because there is also evidence for the risk of cancer connected with the use of other antidiabetic medications. Smith and Gale [44] comment that even though metformin is known to be safe [45], high circulatory levels of endogenous insulin overlap with an increase of the risk of certain types of cancer, suggesting a connection between oncological disease and insulin analogues such as insulin glargine. Other antihyperglycemics are also known to increase the risk of cancer such as sulfonylureas [46] and rosiglitazone [47].

An increasing number of epidemiologic studies have found that diabetes mellitus may alter the risk of developing a variety of cancers [48–51]. Diabetes was a significant predictor of death from cancer of the colon, liver, pancreas, and bladder [52]. History of diabetes was related to an increased bladder cancer risk (adjusted odds ratio = 2.1, 95% CI 1.1–4.1). The association was strongest in those who had diabetes for the longest duration [45]. The study by Yeung et al. [53] proved that diabetic patients had an increased, significant odds ratio for bladder cancer compared with nondiabetics even after adjustment for smoking and age [OR 2.69, p = 0.049 (95% CI 1.006–7.194)]. This study has again highlighted a potential association between diabetes mellitus and transitional cell bladder cancer [53]. Common metabolic complications associated with diabetes mellitus such as higher body mass index (BMI), obesity, and insulin resistance are also known to be individually connected with an increase in the risk of bladder cancer development in diabetes patients [54–56]. The recommendation to apply pioglitazone as a third-line therapy for type 2 diabetes leads to it being prescribed to patients with more advanced forms of the disease with higher possibility of metabolic and other complications which could be another confounding factor for increased bladder cancer risk.

Our study has limitations which are mainly connected with the different designs and methods among the included studies. We did not have individual patient data and therefore could not examine other known risk factors for bladder cancer (such as age, smoking, or occupational exposure). The possibility of publication bias cannot be fully ruled out either, although funnel plot examination did not show any statistical significance.

Conclusions

Many authors claim to have determined that pioglitazone use by patients with diabetes is associated with an increase in the risk of bladder cancer development. Our results are a testament of the opposite. With an overall RR of 1.13 with 95% CI (0.96–1.33) our results support the hypothesis of no difference in the incidence of bladder cancer among the pioglitazone group and the nonuser group. The link between long-term use of pioglitazone and bladder cancer was not confirmed either. Our conclusion is that the explanation of hypothetically increased risk of bladder malignancy should be attributed to other factors. Therefore, there is no eligible reason for diabetes patients not to exploit the benefits of the antihyperglycemic medication pioglitazone.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The meta-analysis is funded by Tchaikapharma High Quality Medicines Inc and the article processing charges are covered by Prof. Toni Vekov. Elena Filipova, Katya Uzunova, and Toni Vekov were involved in the literature search and initial selection of studies. Krassimir Kalinov performed quality assessment of studies and statistical analysis. Elena Filipova, Katya Uzunova, Krassimir Kalinov, and Toni Vekov were involved in the interpretation of results. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. The authors wish to thank Rossitsa Tuneva for providing medical writing support as a language editor.

Disclosures

Katya Uzunova is an employee of Tchaikapharma High Quality Medicines Inc. and Elena Filipova is an employee of Tchaikapharma High Quality Medicines Inc. Krassimir Kalinov and Toni Vekov have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article is based on previously conducted studies, and does not involve any new studies of human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Footnotes

Enhanced content

To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/1598F060448B3052.

References

- 1.Lehmann JM, Moore LB, Smith-Oliver TA, Wilkison WO, Willson TM, Kliewer SA. An antidiabetic thiazolidinedione is a high affinity ligand for peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPAR gamma) J Biol Chem. 1995;270:12953–12956. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.12953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferwana M, Firwana B, Hasan R, et al. Pioglitazone and risk of bladder cancer: a meta-analysis of controlled studies. Diabet Med. 2013;30(9):1026–1032. doi: 10.1111/dme.12144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Charbonnel B, Roden M, Urquhart R, et al. Pioglitazone elicits long-term improvements in insulin sensitivity in patients with type 2 diabetes: comparisons with gliclazide-based regimens. Diabetologia. 2005;48:553–560. doi: 10.1007/s00125-004-1651-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Staels B. Metformin and pioglitazone: effectively treating insulin resistance. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22:S27–S37. doi: 10.1185/030079906X112732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chilcott J, Tappenden P, Jones ML, Wight JP. A systematic review of the clinical effectiveness of pioglitazone in the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Clin Ther. 2001;23:1792–1823. doi: 10.1016/S0149-2918(00)80078-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Krishnaswami A, Ravi-Kumar S, Lewis JM. Thiazolidinediones: a 2010 perspective. Perm J. 2010;14(3):64–72. doi: 10.7812/TPP/09-052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McGuire DK, Inzucchi SE. New drugs for the treatment of diabetes mellitus: part I: thiazolidinediones and their evolving cardiovascular implications. Circulation. 2008;117(3):440–449. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.704080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mearns ES, Sobieraj DM, White CM, et al. Comparative efficacy and safety of antidiabetic drug regimens added to metformin monotherapy in patients with type 2 diabetes: a network meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(4):e0125879. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0125879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Burger M, Catto JWF, Dalbagni G, et al. Epidemiology and risk factors of urothelial bladder cancer. Eur Urol. 2013;63:234–241. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giovannucci E, Harlan DM, Archer MC, et al. Diabetes and cancer: a consensus report. Diabetes Care. 2010;33:1674–1685. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kakehi Y, Hirao Y, Kim W-J, et al. Bladder Cancer Working Group report. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2010;40(Suppl 1):i57–i64. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyq128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.European Medicines Agency. Assessment report for Actos, Glustin, Competact, Glubrava, Tandemact (INN: pioglitazone, pioglitazone + glimepiride, pioglitazone + metformin) (EMA, CHMP/940059/2011). London: EMA; 2011.

- 13.Suzuki S, Arnold LL, Pennington KL, et al. Effects of pioglitazone, a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma agonist, on the urine and urothelium of the rat. Toxicol Sci. 2010;113:349–357. doi: 10.1093/toxsci/kfp256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sato K, Awasaki Y, Kandori H, et al. Suppressive effects of acid-forming diet against the tumorigenic potential of pioglitazone hydrochloride in the urinary bladder of male rats. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2011;251:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2011.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.El-Hage J. Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists: carcinogenicity findings and regulatory recommendations. Monte Carlo: International Atherosclerosis Society Symposium on PPAR; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dormandy JA, Charbonnel B, Eckland DJ, et al. Secondary prevention of macrovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes in the PROactive Study (PROspective pioglitAzone Clinical Trial In macroVascular Events): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2005;366(9493):1279–1289. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67528-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Scheen AJ. Outcomes and lessons from the PROactive study. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2012;98(2):175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hillaire-Buys D, Faillie JL. Pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer. BMJ. 2012;344:e3500. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Erdmann E, Song E, Spanheimer R, van Troostenburg de Bruyn AR, Perez A. Observational follow-up of the PROactive study: a 6-year update. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2014;16:63–74. doi: 10.1111/dom.12180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Borenstein M, Hedges LV, Higgins JPT, Rothstein HR. Introduction to meta-analysis. New York: Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oliveria SA, Koro CE, Yood MU, Sowell M. Cancer incidence among patients treated with antidiabetic pharmacotherapy. Diabetes Metab Syndr Clin Res Rev. 2008;2:47–57. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2007.11.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piccinni C, Motola D, Marchesini G, Poluzzi E. Assessing the association of pioglitazone use and bladder cancer through drug adverse event reporting. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:1369–1371. doi: 10.2337/dc10-2412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lewis JD, Habel LA, Quesenberry CP, et al. Pioglitazone use and risk of bladder cancer and other common cancers in persons with diabetes. JAMA. 2015;314(3):265–277. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.7996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tseng CH. Pioglitazone and bladder cancer: a population-based study of Taiwanese. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:278–280. doi: 10.2337/dc11-1449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Azoulay L, Yin H, Filion KB, et al. The use of pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer in people with type 2 diabetes: nested case–control study. Br Med J. 2012;344:e3645. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e3645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Balaji V, Seshiah V, Ashtalakshmi G, Ramanan SG, Janarthinakani M. A retrospective study on finding correlation of pioglitazone and incidences of bladder cancer in the Indian population. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2014;18(3):425–427. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.131223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bazelier MT, de Vries F, Vestergaard P, Leufkens HG, De Bruin ML. Use of thiazolidinediones and risk of bladder cancer: disease or drugs? Curr Drug Saf. 2013;8(5):364–370. doi: 10.2174/15748863113086660069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hsiao F-Y, Hsieh P-H, Huang W-F, Tsai Y-W, Gau C-S. Risk of bladder cancer in diabetic patients treated with rosiglitazone or pioglitazone: a nested case–control study. Drug Saf. 2013;36:643–649. doi: 10.1007/s40264-013-0080-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jin S-M, Song SO, Jung CH, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among patients with diabetes treated with a 15 mg pioglitazone dose in Korea: a multi-center retrospective cohort study. J Korean Med Sci. 2014;29(2):238–242. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2014.29.2.238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kuo H-W, Tiao M-M, Ho S-C, Yang C-Y. Pioglitazone use and the risk of bladder cancer. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2014;30(2):94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.kjms.2013.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Song SO, Kim KJ, Lee BW, Kang ES, Cha BS, Lee HC. The risk of bladder cancer in Korean diabetic subjects treated with pioglitazone. Diabetes Metab J. 2012;36(5):371–378. doi: 10.4093/dmj.2012.36.5.371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin D, Bell S, Sund R, et al. Pioglitazone and bladder cancer risk: a multipopulation pooled, cumulative exposure analysis. Diabetologia. 2015;58(3):493–504. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3456-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lewis JD, Ferrara A, Peng T, et al. Risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients treated with pioglitazone: interim report of a longitudinal cohort study. Diabetes Care. 2011;34:916–922. doi: 10.2337/dc10-1068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fujimoto K, Hamamoto Y, Honjo S, et al. Possible link of pioglitazone with bladder cancer in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2013;99(2):e21–e23. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2012.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gupta S, Gupta K, Ravi R, et al. Pioglitazone and the risk of bladder cancer: an Indian retrospective cohort study. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(5):639–643. doi: 10.4103/2230-8210.163187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chang C-H, Lin J-W, Wu L-C, Lai M-S, Chuang L-M, Chan KA. Association of thiazolidinediones with liver cancer and colorectal cancer in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Hepatology. 2012;55(5):1462–1472. doi: 10.1002/hep.25509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee M-Y, Hsiao P-J, Yang Y-H, Lin K-D, Shin S-J. The association of pioglitazone and urinary tract disease in type 2 diabetic Taiwanese: bladder cancer and chronic kidney disease. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85479. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Mackenzie TA, Zaha R, Smith J, Karagas MR, Morden NE. Diabetes pharmacotherapies and bladder cancer: a medicare epidemiologic study. Diabetes Ther. 2016;7:61–73. doi: 10.1007/s13300-016-0152-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neumann A, Weill A, Ricordeau P, Fagot JP, Alla F, Allemand H. Pioglitazone and risk of bladder cancer among diabetic patients in France: a population-based cohort study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:1953–1962. doi: 10.1007/s00125-012-2538-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vallarino C, Perez A, Fusco G, et al. Comparing pioglitazone to insulin with respect to cancer, cardiovascular and bone fracture endpoints, using propensity score weights. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(9):621–631. doi: 10.1007/s40261-013-0106-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wei L, Macdonald TM, Mackenzie IS. Pioglitazone and bladder cancer: a propensity score matched cohort study. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04325.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Guidance on the use of pioglitazone for the treatment of type 2 diabetes. London: NICE. Technology Appraisal 63. 2003.

- 43.National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. The management of type 2 diabetes. Quick reference guide. http://www.nice.org.uk/nicemedia/pdf/CG87Quick-RefGuide.pdf. Accessed 04 March 2016.

- 44.Smith U, Gale EA. Does diabetes therapy influence the risk of cancer? Diabetologia. 2009;52:1699–1708. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1441-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.MacKenzie T, Zens MS, Ferrara A, Schned A, Karagas MR. Diabetes and risk of bladder cancer: evidence from a case–control study in New England. Cancer. 2011;117:1552–1556. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vigneri P, et al. Diabetes and cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2009;16(4):1103–1123. doi: 10.1677/ERC-09-0087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.National Diabetes Data Group (U.S.), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (U.S.), National Institutes of Health (U.S.). Diabetes in America, 2nd edn. Bethesda: National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. NIH publication no. 95-1468. 1995.

- 48.Will JC, Vinicor F, Calle EE. Is diabetes mellitus associated with prostate cancer incidence and survival? Epidemiology. 1999;10:313–318. doi: 10.1097/00001648-199905000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Adami HO, McLaughlin J, Ekbom A, et al. Cancer risk in patients with diabetes mellitus. Cancer Causes Control. 1991;2:307–314. doi: 10.1007/BF00051670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wideroff L, Gridley G, Mellemkjaer L, et al. Cancer incidence in a population-based cohort of patients hospitalized with diabetes mellitus in Denmark. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1997;89:1360–1365. doi: 10.1093/jnci/89.18.1360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Will JC, Galuska DA, Vinicor F, et al. Colorectal cancer: another complication of diabetes mellitus? Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:816–825. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Coughlin SS, Calle EE, Teras LR, Petrelli J, Thun MJ. Diabetes mellitus as a predictor of cancer mortality in a large cohort of US adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1160–1167. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Yeung NG, Husain I, Waterfall N. Diabetes mellitus and bladder cancer—an epidemiological relationship? Pathol Oncol Res. 2003;91:30–31. doi: 10.1007/BF03033711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Holman RR, Turner RC. A practical guide to basal and prandial insulin therapy. Diabet Med. 1985;2:45–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.1985.tb00592.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koebnick C, Michaud D, Moore SC, et al. Body mass index, physical activity, and bladder cancer in a large prospective study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomark Prev. 2008;17:1214–1221. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Berhanu P, Perez A, Yu S. Effect of pioglitazone in combination with insulin therapy on glycaemic control, insulin dose requirement and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes previously poorly controlled with combination therapy. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9:512–520. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2006.00633.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.