Abstract

Plants employ various defences killing the insect attacker in an early stage. Oviposition by cabbage white butterflies (Pieris spp.) on brassicaceous plants, including Brassica nigra, induces a hypersensitive response (HR) - like leaf necrosis promoting desiccation of eggs. To gain a deeper insight into the arms race between butterflies and plants, we conducted field and greenhouse experiments using different B. nigra genotypes. We investigated variation in HR and consequent survival of P. brassicae egg clusters. Impact of egg density, distribution type and humidity on HR formation and egg survival was tested. HR differed among plant genotypes as well as plant individuals. Egg density per plant did not affect HR formation. Remarkably, egg survival did not depend on the formation of HR, unless butterflies were forced to lay single eggs. Larval hatching success from single eggs was lower on plants expressing HR. This may be due to increased vulnerability of single eggs to low humidity conditions at necrotic leaf sites. We conclude that effectiveness of HR-like necrosis in B. nigra varies with plant genotype, plant individual and the type of egg laying behaviour (singly or clustered). By clustering eggs, cabbage white butterflies can escape the egg-killing, direct plant defence trait.

Introduction

Plant defences against herbivory largely exhibit phenotypic plasticity, which is a powerful means to cope with threats because a target with variable traits is less likely to be hit1. Plants are well known to defend themselves against herbivorous insects by a wide range of strategies, some of which are genotypically fixed and employed constitutively, and numerous others are based on phenotypic changes that are induced in response to herbivore attack2–5. The range of phenotypic changes of a plant is determined by its genotype and its environment6. Hence, different accessions of a plant species exposed to variable environmental conditions may display variability with respect to the inducibility of their defensive responses.

Egg deposition by insects onto plants often represents the first step of infestation. Plant defences induced by insect oviposition may target the eggs themselves or the herbivorous larvae. Oviposition can inform plants about impending herbivory, and the “warned” plants prepare their defences against hatching larvae. Various plant responses are known to directly kill the eggs by ovicidal compounds, growth of plant tissue around the eggs, or the formation of neoplasms or necrotic leaf tissue (reviewed by refs 7-9). The formation of necrotic leaf tissue in response to insect egg deposition leads to detachment of eggs from leaves or desiccation of eggs and has been described as a hypersensitive-like response (HR)10–16.

From the insect’s perspective, the oviposition behaviour of a mother is an important determinant of successful reproduction17–19. Females invest in survival of their progeny by e.g. hiding the eggs, protecting them with sticky secretions that prevent parasitism, endowing them with predator-deterring compounds or by increasing egg size8, 20, 21. In herbivorous insects, clustering of eggs has been suggested as an adaptation to plant defences8, 21, 22.

Our understanding on the ecology and mechanisms of oviposition-induced plant responses is largely increasing8, 13, 23–25. However, some aspects of plant – insect egg interactions have remained largely unexplored such as (i) the ability of an herbivorous insect to counteract oviposition-induced plant responses, and (ii) the genotypic and individual variation of plant responses to insect oviposition. In contrast to these gaps in knowledge about plant – insect egg interactions, solid information is available on the variability of plant responses to feeding arthropods. Genotype-based plasticity of feeding-inducible plant defensive responses is well documented5, 26–30 and has been suggested to be shaped by the costs of this plasticity31. Furthermore, individual variation in the composition of plant defence-eliciting compounds that feeding larvae introduce into plant wounds is well known32, and some means of counteractions of larvae against feeding-induced plant defences have been detected33–39.

Here, we address the above-mentioned knowledge gaps in plant – insect egg interactions by studying the response of various accessions of the black mustard Brassica nigra to egg deposition by the large cabbage white butterfly (Pieris brassicae). The annual B. nigra shows diverse responses to eggs of Pieris spp., including accelerated flower and seed production as reproductive escape strategy4, 40, attraction of egg- and larval parasitoids14, 40–43, phenotypic changes that affect subsequent herbivore and parasitoid preferences and performances15, 24, 43, and HR - like necrosis10, 14, 15, 41. Different populations of B. nigra respond at different frequencies to singly laid P. rapae eggs or to clustered P. brassicae eggs by HR - like necrosis14, 41. Under both greenhouse and natural conditions, the hatching success of larvae from solitary P. rapae eggs was reduced when the plant expressed HR14.

For the gregarious P. brassicae which lays its eggs in clusters it is unknown as yet whether formation of egg-induced HR-like symptoms and the hatching success depend on the number of eggs per cluster. Although effects of HR-like necrosis on P. brassicae egg survival were previously studied under greenhouse conditions41, a thorough study examining the relationship between HR and survival of clustered eggs of P. brassicae under natural conditions is still lacking. To date, hardly anything is known about the ecological determinants of egg responses induced by herbivore oviposition. As shown in previous studies, egg load45 and abiotic factors such as temperature or water stress10, 12, 46 can negatively or positively affect egg-induced plant defences.

In the present study, we investigated the following specific questions by conducting field, greenhouse, and laboratory experiments: Does formation of HR-like symptoms by B. nigra in response to P. brassicae egg deposition differ (1) among plant accessions and (2) among individuals of a B. nigra accession? (3) Is mortality of clustered P. brassicae eggs dependent on the occurrence of HR and correlated with HR severity? (4) Does clustering of P. brassicae eggs counteract the plant´s HR? Since abiotic environmental conditions may significantly impact on phenotypic plant traits, we also investigated how (5) abiotic parameters (temperature, humidity, total radiation and sum of rain) affect the expression of the plant’s HR and mortality of butterfly eggs.

Results

Variation in HR among plant accessions: field data

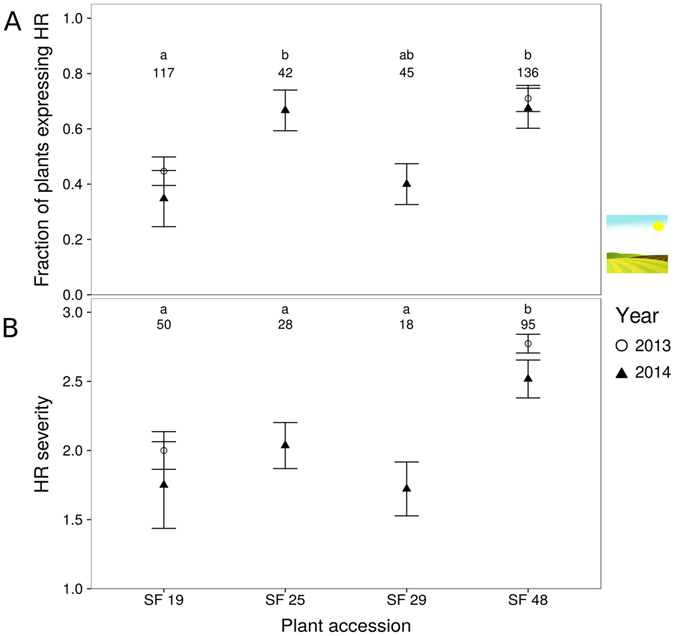

We used a common-garden setting to investigate whether four self-fertilised accessions of B. nigra show differences in expression of HR induced by P. brassicae eggs. Expression of HR was significantly influenced by the plant accession receiving the eggs (GLM, χ² = 24.74, df = 3, P < 0.001, Fig. 1A). Accessions SF25 and SF48 had a higher proportion of plants expressing HR than accession SF19. Moreover, HR severity was also significantly affected by plant accession (GLM, χ² = 69.32, df = 9, P < 0.001, Fig. 1B). HR severity of SF48 was significantly higher than HR severity of the three other plant accessions (Fig. 1B). We conducted this experiment in two consecutive years. The year of the experiment did neither influence the fraction of plants expressing HR, nor the HR severity for SF19 and SF48, which were tested in both years (GLM, χ² = 0.75, df = 1, P = 0.39 and GLM, χ² = 2.06, df = 1, P = 0.15, respectively, Fig. 1). In conclusion, some genotypes show a greater inducibility and severity of HR-like symptoms by P. brassicae eggs than others.

Figure 1.

HR induced by P. brassciae eggs in B. nigra plant accessions used in common garden experiments in 2013 (only SF19 and SF48) and 2014. (A) Fraction of plants expressing HR (mean ± SE) per plant accession. (B) HR severity (mean ± SE) per plant accession (severity 1–3, compare Fig. S1). Numbers of plants tested for each accession are indicated above each data point, different letters indicate significant differences (P < 0.01, LHT post hoc test).

Variation in HR among plant accessions and plant individuals: greenhouse data

In a greenhouse experiment we investigated the variation in expression of HR with respect to plant accession by examining 38 plant individuals belonging to two genotypes which were exposed to eight to ten butterflies that each laid five eggs.

Variation among plant accessions

Unlike under field conditions, neither the presence/absence of HR symptoms nor HR severity were significantly different between the two plant accessions SF19 and SF48 (GLM: χ² = 0.19, df = 1, P = 0.66 and χ² = 2.94, df = 2, P = 0.23).

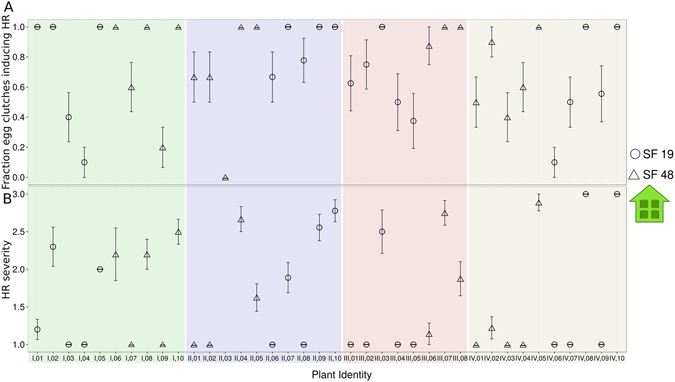

Variation among individual plants

Both the presence of HR symptoms in response to individual egg clutches and HR severity varied significantly among plant individuals (GLM: χ² = 196.59, df = 37, P < 0.001 and χ² = 352.27, df = 74, P < 0.001). As seen in Fig. 2A except for one plant (II.03), all plants expressed HR at least for some of the egg clutches. Seventeen plants expressed HR in response to all egg clutches laid onto them. With respect to the severity of the expressed HR about half of the plants (N = 18) expressed the lowest HR severity in response to all deposited egg clusters, one plant always the medium severity and two always the strongest. All other plants expressed varying degrees of HR severity for the egg clutches laid onto them (Fig. 2B). In conclusion, the data suggest that HR severity (and inducibility) is strongly linked to the individual plant, and differs only slightly between different egg clutches on the same plant.

Figure 2.

HR induced by P. brassicae eggs in different plant individuals from two accessions under greenhouse conditions. (A) Fraction of egg clutches expressing HR per plant (mean ± SD). (B) Severity of HR when HR is expressed in plants (mean ± SD). Four different replicates and therefore plant/butterfly sets were used and marked with differently shaded background and (Latin) numbers for plant identity. Both plant accessions, SF19 and SF48 are separated using different shapes for data points, (see explanation in the figure).

Effects of HR on survival of clustered eggs: field and greenhouse data

Brassica nigra plants were infested with egg clutches of P. brassicae females either in the greenhouse or outside in a field experiment.

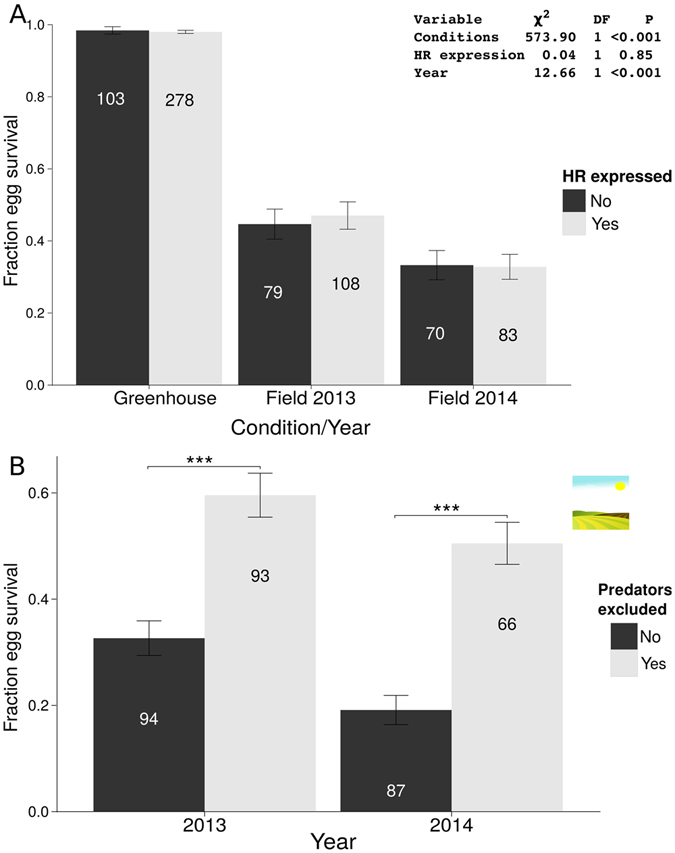

Survival of egg clutches did not depend on the expression of HR (GLM, χ² = 0.19, df = 1, P = 0.66), neither under greenhouse nor field conditions (GLM, χ² = 0.17, df = 1, P = 0.67 and GLM, χ² = 0.01, df = 1, P = 0.93, respectively, Fig. 3). Yet, egg survival was significantly greater in the greenhouse than in the field (GLM, χ² = 593.34, df = 1, P < 0.001). Moreover, under field conditions, survival rates were significantly higher in 2013 than in 2014 (GLM, χ² = 10.72, df = 1, P = 0.001). The large difference in egg survival rates between the greenhouse (almost 100% survival) and field (between 35 and 50% survival) could be due to abiotic factors as well as biotic factors, such as egg predation/parasitism. When egg clutches were protected by fine meshed nets from parasitoids and predators in the field, egg survival indeed significantly increased (from 33% to 60% in 2013, and 19% to 51% in 2014) in both years (MWU, 2013: W = 2700.5, P < 0.001 and 2014: W = 1256, P < 0.001, respectively, Fig. 3B. This suggests that HR is not an effective defence trait against clustered P. brassicae eggs.

Figure 3.

Effect of HR expression on survival of clustered P. brassicae eggs (mean ± SE) laid on B. nigra plants under greenhouse and field conditions (for 2013 and 2014). (A) The numbers within each bar represent the numbers of tested plants. The differences in egg survival until larval hatching between HR expressing (light grey) and non-HR expressing plants (dark grey) are not significant, GLM, family = quasibinomial. Differences between greenhouse and field conditions and between both years of field experiments are indicated by asterisks above the horizontal lines, GLM, family = quasibinomial. (B) Effect of predator/parasitoid exclusion on survival of clustered P. brassicae eggs (mean fraction ± SE) laid on B. nigra plants in the field. Plants were either covered with a fine mesh during the egg phase (predators excluded – light grey) or left uncovered (predators included – dark grey).

Effects of HR on survival of single versus clustered eggs

We investigated formation of HR in dependence of the egg clutch size (number of eggs) per plant and recorded egg survival in dependence of whether eggs were laid singly or clustered. Singly laid eggs were experimentally achieved by manipulating the female´s oviposition mode.

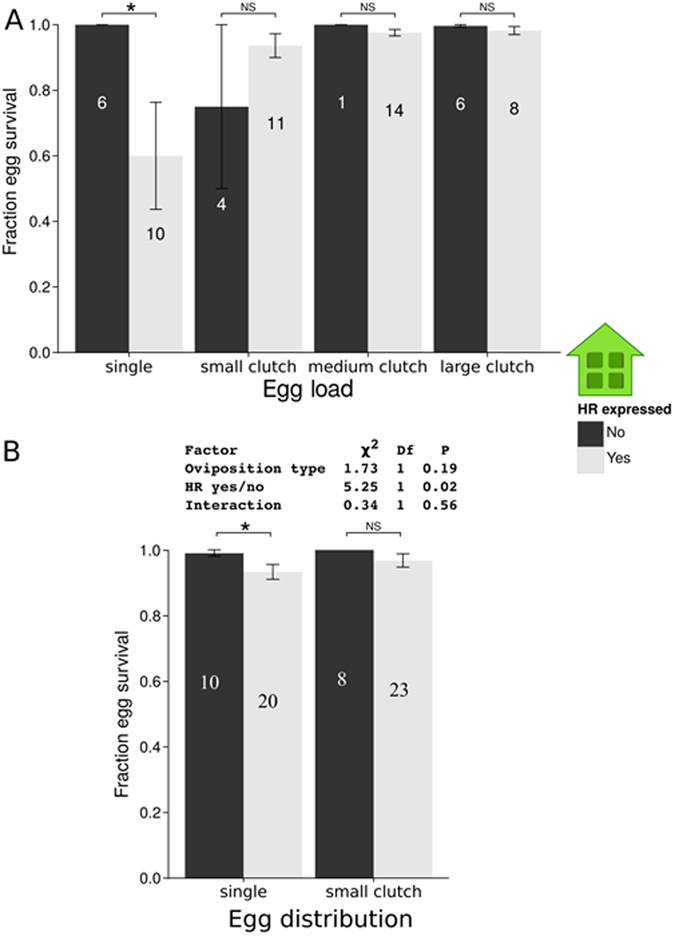

Under greenhouse conditions, HR negatively affected survival of a single egg per plant (GLM, χ² = 6.35, df = 1, P = 0.01, Fig. 4A). However, when more eggs were laid per plant and when these were laid in small (N = 10) or larger groups (N = 50 or 90), the expression of HR did not affect egg survival (GLM, small clutch size/number of eggs: χ² = 1.80, df = 1, P = 0.18, medium: χ² = 0.83, df = 1, P = 0.36, and large: χ² = 1.40, df = 1, P = 0.24, Fig. 4A), while HR negatively affected survival when a female was forced to lay a single egg (GLM, χ² = 6.35, df = 1, P = 0.01, Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Fraction of P. brassicae egg survival under greenhouse conditions. (A) Impact of number of eggs per plant and egg distribution. Effect of HR expression on survival (mean fraction ± SE) of single P. brassicae eggs per plant and P. brassicae egg clusters of different size as stated on the X-axis (small: 10, medium: 50 and large: 90 eggs) laid on B. nigra plants. Survival rates of P. brassicae eggs on B. nigra plants expressing HR (light grey columns) or not (dark grey columns). Numbers in the columns represent the numbers of tested plants. (B) Impact of egg distribution. Effect of HR expression on survival (mean fraction ± SE) of 10 singly laid P. brassicae eggs and of a P. brassicae egg cluster (containing 10 eggs) on B. nigra plants under greenhouse conditions. Survival rates of eggs on B. nigra plants expressing HR (light grey columns) or not (dark grey columns). Numbers in the columns represent the numbers of tested plants. Significant differences are indicated using asterisks. *P < 0.05, ns: not significant, GLM.

In a second experiment, we focused on the question how HR affects egg survival if the number of eggs is the same per plant (here 10 eggs per plant), but the type of egg distribution on a plant differs (singly laid eggs vs clustered eggs). Egg survival was significantly lower on plants expressing HR than on plants that did not express HR (GLM, χ² = 5.25, df = 1, P = 0.02, Fig. 4B). The egg distribution (10 singly laid eggs vs. 10 eggs laid in a cluster) and the interaction between HR expression and egg distribution did not affect egg survival (GLM, χ² = 1.73, df = 1, P = 0.19 and χ² = 0.34, df = 1, P = 0.56, Fig. 4B). However, when the effect of egg distribution on egg survival was tested separately, egg survival was only lower when HR was induced by singly laid eggs (GLM, χ² = 4.07, df = 1, P = 0.04, Fig. 4B) and not by a clutch of 10 eggs (GLM, χ² = 1.99, df = 1, P = 0.16, Fig. 4B).

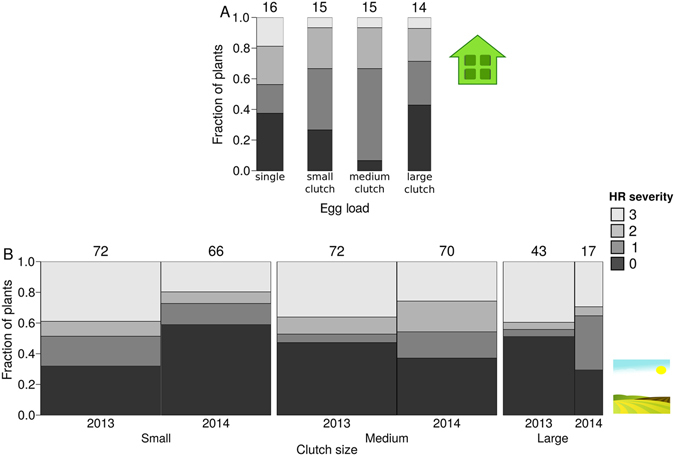

Moreover, both in the greenhouse and in the field, the number of eggs laid per plant did not affect whether HR was expressed or not. Under greenhouse conditions no significant differences were found between plants with varying numbers of eggs (a single egg, groups of 10, ca. 50, ca. 90) in their probability of HR expression (GLM, χ² = 0.001, df = 1, P = 0.98) or the severity of the HR expressed (GLM, χ² = 0.313, df = 1, P = 0.58, Fig. 5A). Under field conditions no significant differences in probability of HR expression were found between plants induced by eggs laid in different clutch sizes (GLM, χ² = 0.003, df = 1, P = 0.96). For the severity of expressed HR no significant differences were found either (GLM, χ² = 3.45, df = 1, P = 0.06, Fig. 5B). However, in the field one genotype (SF29) showed a significantly higher probability to express HR in response to medium-sized egg clutches compared with small ones (Supplementary Figure S1).

Figure 5.

Determination of HR severity induced by different numbers of P. brassicae eggs distributed singly or clustered in different clutch size on B. nigra plants. Mean fractions of plants expressing different degrees of HR severity are given. Each shade of grey represents a different HR severity, and the numbers above each column show the number of plants tested (also represented by the width of the bars). (A) Under greenhouse conditions with single P. brassicae eggs and P. brassicae egg clusters of different size (small: 10, medium: 50 and large: 90 eggs) in categories as stated on the X-axis. (B) Under field conditions with the following categories of egg clutch size: Small: ≥6 < 50 eggs, Medium: ≥50 < 100 eggs and Large: ≥100 eggs.

To conclude, the results suggest that HR is an effective defence strategy against single eggs, rather than clustered eggs and that plants do not increase expression or severity of HR with an increasing number of eggs laid.

Effects of desiccation on egg survival

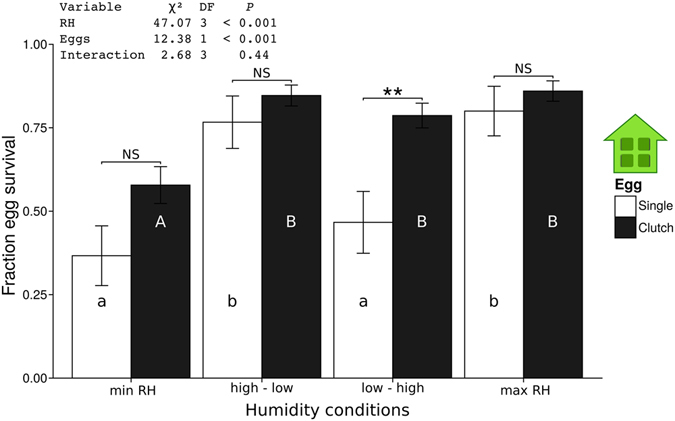

Since humidity conditions at necrotic leaf tissue are expected to differ from those at live, transpiring tissue, we tested how survival of Pieris eggs depends (i) on humidity and (ii) on whether eggs were laid singly or in a clutch (with five eggs).

Overall, eggs in groups of five showed higher survival rates than single eggs (GLM, χ² = 12.38, df = 1, P < 0.001). The humidity conditions applied here significantly affected egg survival (GLM, χ² = 47.07, df = 3, P < 0.001, Fig. 6), while the interaction between humidity and egg group/singly laid egg did not (GLM, χ² = 2.68, df = 3, P = 0.44).

Figure 6.

Effect of various humidity conditions on survival of P. brassicae eggs (mean fraction ± SE) until larval hatching. For the water/humidity treatment: compare Fig. S8. Different lowercase letters indicate significant differences in survival (P < 0.05, LHT post hoc test) of single eggs kept at different humidity conditions, while capital letters indicate significant differences in survival rates (P < 0.05, LHT post hoc test) of five eggs (clutch) kept at different humidity conditions. Asterisks above bars indicate whether or not survival rates of eggs differ between single and clustered eggs kept at a particular humidity treatment (LHT post hoc test). NS = Not significant, **P < 0.01, GLM. N per treatment = 30.

When considering egg survival rates at distinct humidity conditions, however, eggs in clutches of five showed a significantly higher survival rate for the treatment ‘low – high RH’ (GLM, χ² = 10.45, df = 1, P = 0.001), but not for the ‘min RH’ treatment (GLM, χ² = 3.02, df = 1, P = 0.08), ‘high – low RH’ (GLM, χ² = 0.99, df = 1, P = 0.32) or max RH treatment (GLM, χ² = 0.60, df = 1, P = 0.44, Fig. 6). The min RH treatment resulted in a significantly lower survival of eggs laid in a clutch compared to all other water treatments (Fig. 6). On the other hand, survival of singly laid eggs was significantly lower when no water was added in the beginning of the experiment (min RH and low – high RH treatments, Fig. 6). The weight loss/gain of eggs was different between single and clustered eggs. Single eggs lost or gained weight faster than the clustered eggs (Supplementary Figure S2). However, these differences were only significant for one time period in the high to low humidity treatment (between 51.625 h and 70.25 h after starting, Tukey HSD, P = 0.003, Fig. S2) and at two time periods in the low to high treatment (between 3.125 h and 22.875 h after starting, Tukey HSD, P = 0.001 and between 51.625 h and 70.25 h after starting Tukey HSD, P < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S2). The weight fluctuations are probably due to the loss and uptake of water and/or respiration. The stronger weight fluctuation in single eggs exposed to changing humidity conditions might explain their lower survival rates.

Effects of abiotic factors

None of the weather factors (sum daily rainfall, relative humidity, mean daily temperature and mean total daily radiation) was correlated with the fraction of plants expressing HR in both experimental field seasons. None of the parameters had a significant impact on the fraction of egg clutches inducing HR (GLM, for (a) χ² = 0.84, df = 1, P = 0.36, (b) χ² < 0.001, df = 1, P = 0.98, (c) χ² = 0.01, df = 1, P = 0.91 and (d) χ² = 0.82, df = 1, P = 0.37, Supplementary Figure S3). Egg survival was tested under the above-mentioned weather factors, the expression of HR and the interaction between the weather factor and HR expression. Mean sum of the daily rainfall did significantly influence egg survival (GLM, χ² = 4.95, df = 1, P = 0.03, χ² = 0.09, Supplementary Figure S4) Interestingly, survival rates were highest when rainfall was moderate, indicating again that higher air humidity benefits egg survival, while highest rainfall brought the egg survival back to the same level as low rainfall. Neither HR expression nor the interaction of both changed egg survival (GLM, df = 1, P = 0.77, χ² = 0.28, df = 1, P = 0.60, Supplementary Figure S4). None of the other factors significantly affected egg survival (Supplementary information).

Discussion

Our study reveals that plant genetic background influenced the likelihood and severity of HR induced by P. brassicae eggs under natural conditions. Interestingly, this variation in an egg-killing plant defence trait was not effective against a butterfly that deposits eggs in clusters. We show that the larval hatching rate from P. brassicae eggs laid in clutches of different sizes on B. nigra plants expressing HR - like necrosis is not affected by clutch size, neither under greenhouse nor under natural conditions. Only when butterflies were forced to lay single eggs, egg survival was lower when leaf necrosis was induced. Our data show that singly laid eggs suffer a stronger decrease in survival under low humidity conditions than eggs deposited in groups, which could explain the differences in the detrimental effect of HR – like necrosis on single and clustered eggs.

We hypothesize that formation of HR necrosis evolved as a defensive trait against lepidopteran specialists of brassicaceous plants. Two tested generalist moth species, Spodoptera exigua and Mamestra brassicae did not induce HR necrosis in B. nigra 40–42. A cue common to egg deposition by Pierid species might trigger HR. Pieris brassicae is the only Pierid species in The Netherlands that clusters eggs on brassicaceous plants47. This oviposition behaviour might render HR-like necrosis useless as a defence against eggs in this specific case.

An attenuating effect of egg clustering on the influence of an induced plant defensive response was also shown for the interaction between Viburnum plant and eggs of the viburnum leaf beetle (Pyrrhalta viburni): the beetle females prefer to oviposit on egg-infested Viburnum twigs by inserting their eggs into a cavity which the gravid female gnaws into the twig21, 48. Egg deposition induces the twig to grow wound tissue which squeezes the eggs. When eggs are aggregated in higher numbers, this egg-induced response is mitigated21.

Even though egg clustering seems very effective to counteract inducible egg-killing defences, it may increase the risk of parasitism and predation. Egg clusters might be easier detectable by visually orienting predators like birds than singly laid eggs. Furthermore, insect egg clusters might also be attractive targets for small egg parasitoids like Trichogramma spp. as they can easily parasitise many eggs after having encountered a clutch49, 50. Besides possible predation or parasitism risks, cannibalism is common in gregarious species. Upon hatching, P. brassicae caterpillars both eat their own egg shell and sometimes cannibalise the eggs of their siblings51 (E. Griese, pers. obs.). Finally, egg clustering may lead to competition for food among the caterpillars if the resources are limited. Some or all of these factors might have led to the situation where most species belonging to the Pierini such as P. rapae lay single eggs despite the fact that egg clustering can protect eggs from desiccation due to HR-like necrosis.

From the plant’s perspective, successful egg-killing defences reduce the chance of larval feeding damage. Gregariously feeding P. brassicae larvae can completely defoliate a B. nigra plant and cause irreversible damage to flowers (E. Griese & D. Lucas-Barbosa pers. obs.). In a previous study, it was shown for the solitary P. rapae that the percentage of eggs inducing HR is not dependent on the number of singly laid eggs on the plant, ranging from 2 to 9. However, formation of strong HR resulted in significantly reduced survival of the singly laid P. rapae eggs14. For Heliconius subflexa, the survival of singly laid eggs on Physalis sp. plants was lower when HR and/or neoplasm formation were expressed12. These examples corroborate our observation that singly deposited eggs of butterflies are affected by egg-killing plant responses.

Because plants will suffer more feeding damage from larvae hatching from egg clutches than from a few singly laid eggs, plants likely benefit from expressing a stronger HR - like necrosis against a higher number of eggs laid in a cluster. However, we did not find a correlation between the number of eggs laid (in a single clutch) and the probability or strength of HR formation. Moreover, the hatching success of P. brassicae larvae was not reduced by HR. Only when P. brassicae butterflies were forced to lay eggs singly onto the plant, the expression of HR reduced the hatching success. Our data indicate that P. brassicae can benefit from laying eggs in clutches. So far, it has been suggested that egg clustering increases the reproductive success of female butterflies17, especially when host plants are scarce. Hence, egg clustering may be beneficial for P. brassicae for two reasons: on the one hand it may be a cost-saving behaviour with respect to the energy invested in searching for oviposition sites, and on the other hand it obviously counteracts the negative effects of an egg-inducible direct plant defence trait, i.e. HR-like leaf necrosis.

The present study reveals that plant accessions differ in HR inducibility (likelihood of expressing HR) and the severity of HR expressed in response to insect egg deposition. Previous studies have shown genetic variation in plant defence traits only for defences against feeding herbivores (e.g. ref. 52), among them also laboratory and field studies of Brassica species investigating defence traits against feeding Pieris larvae. For example, laboratory experiments revealed that differences in volatile blends of B. oleracea var. alba L. varieties induced by feeding P. brassicae caterpillars lead to differences in attraction of a larval parasitoid. The differential attractiveness of these plant varieties to larval parasitoids matched different parasitism rates of larvae feeding on different varieties in the field; furthermore, herbivore preference and performance, as well as insect communities living on the plants varied among these plant varieties53–55. These results are in line with our findings, confirming that different genotypes of a Brassica species differ in their feeding- and oviposition-inducibility of anti-herbivore defence traits under field conditions.

Our data further show variation among individual plants in HR expression. Some plant individuals exhibited resistance to eggs and expressed an HR-like response, whereas others did not. It is likely that this variation is caused by a high variation in the responsiveness of a resistance (R) gene in B. nigra plants recognising specific cues of Pieris eggs. R-genes targeting phytopathogens are among the most polymorphic loci in plant genomes56, 57. Whether this is similar for R-gene(s) involved in HR against Pieris eggs is an open question. Studies of plant-pathogen co-evolution often report one type of interaction, the gene-for-gene interaction, whereby plants generate R products that recognise cues from the specific attacker58. Although the plant genotypes used in our study originated from a self-fertilisation event (produced by E.H. Poelman) (or crossing of two self-fertilised plants of the same genotype, produced by E.H. Poelman and E. Griese), they are not homozygous which may explain the observed variation in HR expression between individual plants of each accession.

Our data suggest that laying eggs in clusters reduces their susceptibility to HR-like necrosis. Formation of necrotic leaf tissue might lower the humidity around the egg clutch because of reduced plant transpiration at this site. Shapiro and DeVay10 suggest that HR kills eggs by reducing humidity at the interface between plant surface and eggs, thus resulting in detachment of eggs from the leaf or in egg desiccation. Water loss of eggs is determined by various factors. In addition to atmospheric humidity, transpiration of the plant tissue and other egg-related factors like the chemical composition of the eggshell, the serosa, size of the egg surface as well as the exocrine secretion attached to the eggshell may play a role in preventing egg desiccation59–61. Especially the formation of the serosa has been shown to drastically increase drought resistance in eggs of several insect species, including beetles and mosquito species62–64. Whether the serosa plays a similar role in butterfly eggs remains to be investigated. In addition to the mentioned parameters, aggregation of eggs could prevent desiccation under low humidity conditions, as was shown for Chlosyne lacinia butterflies feeding on the common sunflower Helianthus annuus 51. Their egg clutches can vary in size and the number of layers. A higher number of egg layers and larger clutch size improved the hatching success under low humidity conditions51. In the present study, we show that clustered P. brassicae eggs can recover better from low humidity conditions when transferred to high humidity than singly laid eggs; the survival rate of clustered eggs was higher under these conditions. This indicates that the strong, negative effects of HR-related necrosis on especially the singly laid eggs might also be due to reduced humidity at the oviposition site. Thus, by implication, egg aggregation can protect eggs against a detrimental HR-associated effect, i.e. low humidity at the oviposition site.

Unlike under field conditions, the different accessions did neither differ in the likelihood of expressing HR nor in the strength of HR expression when placed under greenhouse conditions. Furthermore, the proportion of plants that show HR as well as the average HR severity were generally lower. These results suggest that abiotic factors present in the field but not in the greenhouse (e.g. UV-light or higher temperature and humidity fluctuations), affect HR expression. However, in our field experiment, none of the particular abiotic factors that we determined affected the expression of HR in B. nigra in neither of the two seasons. Nevertheless, some plant accessions might have been more affected by changes in abiotic conditions in the field than others, which would explain the more similar HR expression of the accessions in the greenhouse. In contrast to our experimental field data, Petzold-Maxwell et al.12 showed that temperature was positively correlated with the likelihood of the expression of HR and neoplasm formation induced by eggs of the moth Heliothis subflexa in Physalis angulata plants in a field experiment; the temperatures measured in this study were higher than the highest temperature measured in our field study (ca. 21 °C). Furthermore, a previous study on B. nigra and P. rapae in California, U.S.A., indicated that HR necrosis was more pronounced at high temperatures (above 30 °C)10. The range of changes of abiotic factors as well as very high temperature and low humidity may affect the expression of HR.

Our study revealed that aggregating eggs is a strategy for P. brassicae to avoid negative effects of HR as a direct egg-killing response. However, there must be some fitness costs associated with egg clustering, because other common Pieris species (e.g. P. rapae and P. napi) lay single eggs65. Costs of egg clustering could be associated with increased larval competition on the same food source and/or increased egg and larval predation or parasitism risks. Future studies need to elucidate the ecological consequences that B. nigra plant genotypes and individuals face when not expressing HR-like necrosis in response to P. brassicae eggs.

Methods

Plants and insects

Brassica nigra L. plants were grown either in a greenhouse (18 ± 5 °C, 50–70% RH, L16: D8) or, for field experiments, first grown in the greenhouse for ca. one week, and then placed in an outdoor area protected from wind and rain for two to three weeks. For the experiments in 2013, we used seeds of two self-fertilised plants (SF19 and SF48) that had been collected in 2009 from a B. nigra population near the River Rhine in Wageningen, The Netherlands (N51.96, E05.68). In 2014, seeds produced from plants of the original self-fertilised plants of the same accessions- and of two additional accessions were used (SF19, SF25, SF29 and SF48).

Pieris brassicae L. (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) was reared on Brussels sprouts plants (B. oleracea var. gemmifera cv. Cyrus) in a climate room (21 ± 1 °C, 50–70% RH, L16: D8). Freshly emerged virgin female and male P. brassicae butterflies were obtained from the rearing and kept isolated. Two days after emergence they were allowed to mate, and two days later the mated female butterflies were used for egg deposition in the experiments.

Experimental conditions

Common garden experiments under field conditions. Research questions 1, 3 and 5 were tested in a common garden setup, conducted in two consecutive years (2013 and 2014). In both years, young greenhouse-grown seedlings (three weeks old) were planted into the field in three different periods, two weeks apart from each other, starting mid-May and ending end of July. The seedlings were planted in fields of the experimental farm of Wageningen University (Unifarm), The Netherlands. Several B. nigra accessions were planted in the field. In 2013, SF19 and SF48 were grown, and in 2014 we planted SF19, SF25, SF29 and SF48. In total 192 plants in 2013 and 240 in 2014 were infested with P. brassicae eggs. The plants were organised into plots namely in 12 rows of four plots each in 2013 and in 15 rows of four plots each in 2014. Each plot contained four egg-infested plants with three metre distance between the plots. A mixture of Lolium and Poa grasses was sown in between the plots. The egg-infested plants were grown about two metre apart from each other within a plot. Half of the plants were covered with a fine mesh protecting eggs from predators and parasitoids. Plants were infested with eggs when they were four to five weeks old. One to two weeks after planting, each plant was exposed to a mated female which was kept on a plant until egg deposition (between 0.5 to 24 h) by covering it with a gauze net. After deposition of one egg cluster (additional clusters were gently removed), the leaf with the egg cluster was photographed for documentation and later counting of the eggs per cluster.

Greenhouse experiments. Research questions 1 to 4 were also addressed under greenhouse conditions (22 ± 2 °C, 50–70% RH, L16: D8).

Egg survival

The survival rate of eggs was calculated based on the total number of eggs and the number of caterpillars that hatched (hatched caterpillars/total number of eggs). The number of caterpillars was counted just after hatching by visual observation or by taking a picture and counting eggs and caterpillars with the help of the computer programmes ImageJ as described by Schneider et al.66 and Gimp (see http://www.gimp.org/).

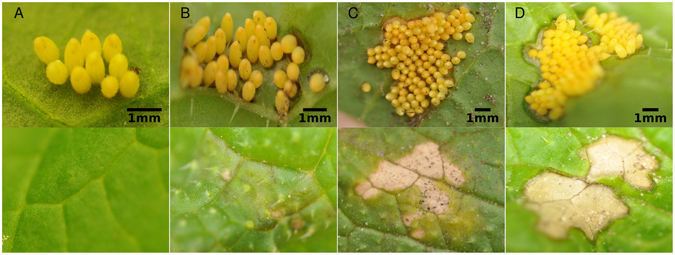

Determination of HR-like necrosis

All plants in the field and greenhouse were visually checked for HR symptoms three to four days after egg deposition (Fig. 7). The plants were categorised into ‘HR-‘ (no necrotic zone observed, Fig. 7A) or ‘HR+ ’ (with necrotic zone, Fig. 7A–D). When HR was observed, its severity was quantified by categorising it into three different classes: necrosis visible underneath the eggs (HR severity ‘1’) (Fig. 7B), necrosis also visible on the other side of the leaf (HR severity ‘2’) (Fig. 7C), and necrosis visible around the eggs and the other side of leaf with clear edges (HR severity ‘3’) (Fig. 7D). Four days after egg deposition, the HR is fully expressed and does not change any more.

Figure 7.

Different severity levels of HR - like necrosis induced by egg clutches of P. brassicae laid onto B. nigra plants under field conditions. The upper row shows the abaxial side of a leaf with eggs, the lower row shows the adaxial side of a leaf. (A) No HR - like necrosis induced (no HR = 0), (B) HR severity 1: necrosis can be observed below eggs, but hardly on the other side of the leaf, (C) HR severity 2: necrosis has spread and can be clearly observed on both sides of the leaf, the edges of the reaction are diffuse. (D) HR severity 3: necrosis is strongly expressed also around the egg clutch with sharp edges. All clutches shown are the same age (four days after egg deposition).

Effect of plant individual and genotype on HR expression

A four-week-old B. nigra plant from either the SF19 or SF48 accession was infested with eggs in the greenhouse as described above. A female butterfly was placed on a leaf for oviposition. As soon as it had laid five eggs, the butterfly was removed from the cage and a new female was introduced. After a plant had received eggs from eight to ten female individuals (five eggs per female), it was replaced by a new one and offered to the same set of butterflies. Hence, in total each plant received 40 to 50 eggs on a single leaf, a procedure which was repeated for eight to ten plants (half of them being SF19, half SF48) using the same set of females (Supplementary Figure S5). In total, four sets of eight to ten plants, each with eggs from a different set of eight to ten butterflies were prepared. The youngest leaf large enough to sustain all eggs (usually 3rd or 4th leaf from the top of the plant) was infested with eggs, and infestation took less than one hour per plant. The sequence of butterflies used for oviposition was randomised for each plant. We recorded HR-like symptoms and their severity induced by each egg cluster for a period of four days after egg deposition. Egg survival was recorded as well (as described above). Thus, these parameters were assessed for each plant individual.

Effects of egg clutch size and egg clustering on HR expression and egg survival

To investigate whether the number of eggs laid affects HR severity under greenhouse conditions, P. brassicae butterflies were allowed to deposit eggs in three different clutch sizes on plants from two B. nigra accessions (SF19 and SF48). Four-week-old B. nigra plants were placed in a cage (35 × 60 × 40 cm) together with one P. brassicae female to obtain either 1, 10, 50 or 90 eggs per plant. Additional eggs were gently removed right after discovery using a soft brush. Fourteen to sixteen plants per treatment were infested.

To investigate further whether the type of egg distribution (singly laid eggs versus clustered eggs) impacts on the effects of HR on egg survival when plants are deposited with the same number of eggs, we conducted a further experiment in which B. nigra plants were always infested with 10 P. brassicae eggs. The eggs were either laid as a clutch or singly. The 10 singly laid eggs were at least 5 mm apart but still on the same leaf. For each egg distribution mode we used 32 plants. However, one female which was used for both egg distributions laid unfertilised eggs, and one egg-deposited leaf of a plant used for the single egg distribution broke off during the experiment, thus reducing the number of plants to 30 (for singly laid eggs) and 31 (for clustered eggs).

Under field conditions, we recorded HR-like symptoms and their severity induced by each egg cluster for a period of four days after egg deposition. We correlated the different egg clutch sizes with formation of HR and egg survival.

Effect of abiotic factors on HR expression and egg survival

Microclimate

Egg-induced formation of necrotic leaf tissue is likely to be associated with changes in humidity at the interface between plant surface and eggs. To investigate whether differences in humidity and changes in humidity affect single and aggregated eggs differentially, a laboratory experiment was conducted in which freshly laid eggs were kept in a climate cell under controlled temperature and light conditions (24 ± 0.5 °C, L16: D8) but different humidity conditions (Supplementary Figure S6). First, a filter paper disc was laid into a Petri dish (9.4 cm diameter), and lids of small Petri dishes (5.8 cm diameter) were placed onto the filter paper discs. Eggs were carefully removed from B. oleracea var. gemmifera plants and transferred singly or in a group of five into the cap of an Eppendorf tube (1.5 ml). The eggs had been laid maximally two hours before the experiment. Five caps with eggs were placed onto each small Petri dish lid. Then the large Petri dishes (9.4 cm diameter) were closed. The set up was chosen to avoid direct contact of eggs with the water. The following humidity conditions were generated: (i) The filter paper was completely soaked with 2 ml water after placing the eggs into the dishes. We assumed that the relative humidity was constantly kept at nearly 100% under the closed lid during the whole egg-development period (4.5 days) (max RH treatment). (ii) A dry environment of the eggs (mimicking plant cell necrosis) was reached by not adding water (min RH treatment). (iii) The effect of change in humidity on egg survival was tested by adding 1 ml water at the beginning of the experiment, and then allowing complete evaporation (humidity changes from high to low (referred to as high-low RH). (iv) The reverse treatment (humidity changes from low to high) was created by adding 1 ml water only 2.5 days after placing the eggs into the setup (referred to as low-high RH). The hatching success was measured after four to five days.

Macroclimate

Weather data for the periods in which the common garden experiments were conducted (see above) were obtained from the Veenkampen weather station of Wageningen University, around 3.25 km west of the field site. Data on the daily mean temperature (°C), the sum of all net radiation per day (W/m²), mean relative humidity (%) and the sum of daily rainfall were collected for all days of the experiment during the field season. Their values over the four days following egg deposition were used to calculate a mean ± SE value. The mean value was checked for correlation with expression of HR and its severity. The mean value was also correlated with the mean value of egg survival for the period of time.

Statistical analysis

Generalised linear models (GLM) were used as the main tool for statistical analysis for all experiments. Egg survival and HR expression as response variable were analysed using a binominal distribution. The HR severity as response variable was analysed using a Poisson distribution. To compare different factor levels within a model pairwise Mann-Whitney – U tests were conducted. Alternatively, a Tukey HSD test was conducted if applicable. All tests were conducted using the statistic platform R 3.2.567.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank André Gidding, Léon Westerd, Joop Woelke and Frans van Aggelen for culturing insects and Unifarm of Wageningen University for providing plants for the field experiments. We thank Erik Poelman for the self-fertilised B. nigra lines, help with setting up the field experiments and fruitful discussions. Furthermore, we thank Emilie Scheggetman, Michele Alfano and Ingeborg van Es, for help with some experiments. We thank the DAAD (57044990), The Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO/TTW Vidi grant 14854) and the German Research Foundation (CRC 973; www.sfb973.de) for funding.

Author Contributions

All authors conceived and designed the experiments. E.G. and N.E.F. performed experiments, conducted fieldwork. E.G. conducted statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the paper. All authors interpreted results, drafted and revised the article.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-06704-z

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Adler F, Karban R. Defended fortresses or moving targets - another model of inducible defenses inspired by military metaphors. Am. Nat. 1994;144:813–832. doi: 10.1086/285708. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrawal AA. Specificity of induced resistance in wild radish: causes and consequences for two specialist and two generalist caterpillars. Oikos. 2000;89:493–500. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2000.890308.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agrawal AA. Ecology - Phenotypic plasticity in the interactions and evolution of species. Science. 2001;294:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1060701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lucas-Barbosa D, van Loon JJA, Gols R, van Beek TA, Dicke M. Reproductive escape: annual plant responds to butterfly eggs by accelerating seed production. Funct. Ecol. 2013;27:245–254. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.12004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stam JM, et al. Plant interactions with multiple insect herbivores: From community to genes. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2014;65:689–713. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050213-035937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marais DLD, Hernandez KM, Juenger TE. Genotype-by-environment interaction and plasticity: Exploring genomic responses of plants to the abiotic environment. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2013;44:5–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-110512-135806. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hilker M, Fatouros NE. Resisting the onset of herbivore attack: plants perceive and respond to insect eggs. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2016;32:9–16. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2016.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hilker M, Fatouros NE. Plant responses to insect egg deposition. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2015;60:493–515. doi: 10.1146/annurev-ento-010814-020620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fatouros, N. E., Cusumano, A., Danchin, E. G. J., and Colazza, S. Prospects of pest-killing defenses for sustainable crop protection. Ecology and Evolution. 6, 6906–6918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Shapiro AM, DeVay JE. Hypersensitivity reaction of Brassica nigra L. (Cruciferae) kills eggs of Pieris butterflies (Lepidoptera: Pieridae) Oecologia. 1987;71:631–632. doi: 10.1007/BF00379310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Balbyshev NF, Lorenzen JH. Hypersensitivity and egg drop: A novel mechanism of host plant resistance to Colorado potato beetle (Coleoptera: Chrysomelidae) J. Econ. Entomol. 1997;90:652–657. doi: 10.1093/jee/90.2.652. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Petzold-Maxwell J, Wong S, Arellano C, Gould F. Host plant direct defence against eggs of its specialist herbivore. Heliothis subflexa. Ecol. Entomol. 2011;36:700–708. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2011.01315.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reymond P. Perception, signaling and molecular basis of oviposition-mediated plant responses. Planta. 2013;238:247–258. doi: 10.1007/s00425-013-1908-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fatouros NE, et al. Synergistic effects of direct and indirect defences on herbivore egg survival in a wild crucifer. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2014;281:20141254. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pashalidou FG, Fatouros NE, Van Loon JJA, Dicke M, Gols R. Plant-mediated effects of butterfly egg deposition on subsequent caterpillar and pupal development, across different species of wild Brassicaceae. Ecol. Entomol. 2015;40:444–450. doi: 10.1111/een.12208. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gouhier-Darimont C, Schmiesing A, Bonnet C, Lassueur S, Reymond P. Signalling of Arabidopsis thaliana response to Pieris brassicae eggs shares similarities with PAMP-triggered immunity. J. Exp. Bot. 2013;64:665–674. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Courtney S. The evolution of egg clustering by butterflies and other insects. Am. Nat. 1984;123:276–281. doi: 10.1086/284202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ramos RR, Rodrigues D, Freitas AVL. Oviposition preference and larval performance in a Heliconius erato phyllis (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae) population from southeastern Brazil: is there a positive relationship? J. Nat. Hist. 2012;46:669–681. doi: 10.1080/00222933.2011.651633. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortuna TM, et al. A tritrophic approach to the preference-performance hypothesis involving an exotic and a native plant. Biol. Invasions. 2013;15:2387–2401. doi: 10.1007/s10530-013-0459-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Blum, M. S. & Hilker, M. Chemical protection of insect eggs. in Chemoecology of Insect Eggs and Egg Deposition (eds Hilker, M. & Meiners, T.) 61–90 (Blackwell, Berlin and Oxford, 2002).

- 21.Desurmont GA, Weston PA. Aggregative oviposition of a phytophagous beetle overcomes egg-crushing plant defences. Ecol. Entomol. 2011;36:335–343. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2011.01277.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stamp N. Egg deposition patterns in butterflies - Why do some species cluster their eggs rather than deposit them singly. Am. Nat. 1980;115:367–380. doi: 10.1086/283567. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hilker M, Meiners T. Plants and insect eggs: How do they affect each other? Phytochemistry. 2011;72:1612–1623. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pashalidou FG, et al. Early herbivore alert matters: plant-mediated effects of egg deposition on higher trophic levels benefit plant fitness. Ecol. Lett. 2015;18:927–936. doi: 10.1111/ele.12470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Little D, Gouhier-Darimont C, Bruessow F, Reymond P. Oviposition by pierid butterflies triggers defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2007;143:784–800. doi: 10.1104/pp.106.090837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Degen T, Dillmann C, Marion-Poll F, Turlings TCJ. High genetic variability of herbivore-induced volatile emission within a broad range of maize inbred lines. Plant Physiol. 2004;135:1928–1938. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.039891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gols R, et al. Performance of generalist and specialist herbivores and their endoparasitoids differs on cultivated and wild Brassica populations. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008;34:132–143. doi: 10.1007/s10886-008-9429-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gols R, et al. Genetic variation in defense chemistry in wild cabbages affects herbivores and their endoparasitoids. Ecology. 2008;89:1616–1626. doi: 10.1890/07-0873.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gols R, van Dam NM, Raaijmakers CE, Dicke M, Harvey JA. Are population differences in plant quality reflected in the preference and performance of two endoparasitoid wasps? Oikos. 2009;118:733–743. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0706.2008.17231.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kappers IF, Hoogerbrugge H, Bouwmeester HJ, Dicke M. Variation in herbivory-induced volatiles among cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) varieties has consequences for the attraction of carnivorous natural enemies. J. Chem. Ecol. 2011;37:150–160. doi: 10.1007/s10886-011-9906-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agrawal AA. Herbivory and maternal effects: Mechanisms and consequences of transgenerational induced plant resistance. Ecology. 2002;83:3408–3415. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2002)083[3408:HAMEMA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Roda A, Halitschke R, Steppuhn A, Baldwin IT. Individual variability in herbivore-specific elicitors from the plant’s perspective. Mol. Ecol. 2004;13:2421–2433. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2004.02260.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Musser RO, et al. Herbivory: Caterpillar saliva beats plant defences - A new weapon emerges in the evolutionary arms race between plants and herbivores. Nature. 2002;416:599–600. doi: 10.1038/416599a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lawrence SD, Novak NG, Blackburn MB. Inhibition of proteinase inhibitor transcripts by Leptinotarsa decemlineata regurgitant in Solanum lycopersicum. J. Chem. Ecol. 2007;33:1041–1048. doi: 10.1007/s10886-007-9285-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lawrence SD, Novak NG, Ju CJ-T, Cooke JEK. Potato, Solanum tuberosum, defense against colorado potato beetle, Leptinotarsa decemlineata (Say): Microarray gene expression profiling of potato by colorado potato beetle regurgitant treatment of wounded leaves. J. Chem. Ecol. 2008;34:1013–1025. doi: 10.1007/s10886-008-9507-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Weech M-H, Chapleau M, Pan L, Ide C, Bede JC. Caterpillar saliva interferes with induced Arabidopsis thaliana defence responses via the systemic acquired resistance pathway. J. Exp. Bot. 2008;59:2437–2448. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ern108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bos JIB, et al. A functional genomics approach identifies candidate effectors from the aphid species Myzus persicae (green peach aphid) Plos Genet. 2010;6:e1001216. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Consales F, et al. Insect oral secretions suppress wound-induced responses in Arabidopsis. J. Exp. Bot. 2012;63:727–737. doi: 10.1093/jxb/err308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chung SH, et al. Herbivore exploits orally secreted bacteria to suppress plant defenses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2013;110:15728–15733. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1308867110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pashalidou FG, Lucas-Barbosa D, van Loon JJA, Dicke M, Fatouros NE. Phenotypic plasticity of plant response to herbivore eggs: effects on resistance to caterpillars and plant development. Ecology. 2013;94:702–713. doi: 10.1890/12-1561.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fatouros NE, et al. Plant volatiles induced by herbivore egg deposition affect insects of different trophic levels. Plos One. 2012;7:e43607. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0043607. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cusumano A, Weldegergis BT, Colazza S, Dicke M, Fatouros NE. Attraction of egg-killing parasitoids toward induced plant volatiles in a multi-herbivore context. Oecologia. 2015;179:163–174. doi: 10.1007/s00442-015-3325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pashalidou FG, et al. To be in time: egg deposition enhances plant-mediated detection of young caterpillars by parasitoids. Oecologia. 2015;177:477–86. doi: 10.1007/s00442-014-3098-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ponzio C, et al. Volatile-mediated foraging behaviour of three parasitoid species under conditions of dual insect herbivore attack. Anim. Behav. 2016;111:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.10.024. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Desurmont GA, Donoghue MJ, Clement WL, Agrawal AA. Evolutionary history predicts plant defense against an invasive pest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7070–7074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102891108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Desurmont GA, Donoghue MJ, Clement WL, Agrawal AA. Evolutionary history predicts plant defense against an invasive pest. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2011;108:7070–7074. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1102891108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lewington, R. Zakgids. Dagvlinders voor Nederland en Vlaanderen. (2016). Kosmos Uitgevers Utrecht/Antwerpen

- 48.Hilker M. Protective devices of early developmental stages in Pyrrhalta viburni (Coleoptera, Chrysomelidae) Oecologia. 1992;92:71–75. doi: 10.1007/BF00317264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fatouros NE, Huigens ME. Phoresy in the field: natural occurrence of Trichogramma egg parasitoids on butterflies and moths. Biocontrol. 2012;57:493–502. doi: 10.1007/s10526-011-9427-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Huigens, M. E. & Fatouros, N. E. A hitch-hikers guide to parasitism: the chemical ecology of phoretic insect parasitoids. in Chemical Ecology of Insect Parasitoids (eds Wajnberg, E. & Colazza, S.) 86–111 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd., 2013).

- 51.Clark BR, Faeth SH. The evolution of egg clustering in butterflies: A test of the egg desiccation hypothesis. Evol. Ecol. 1998;12:543–552. doi: 10.1023/A:1006504725592. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Agrawal AA, van Zandt PA. Ecological play in the coevolutionary theatre: genetic and environmental determinants of attack by a specialist weevil on milkweed. J. Ecol. 2003;91:1049–1059. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00831.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Poelman EH, van Dam NM, van Loon JJA, Vet LEM, Dicke M. Chemical diversity in Brassica oleracea affects biodiversity of insect herbivores. Ecology. 2009;90:1863–1877. doi: 10.1890/08-0977.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Poelman EH, Van Loon JJA, Van Dam NM, Vet LEM, Dicke M. Herbivore-induced plant responses in Brassica oleracea prevail over effects of constitutive resistance and result in enhanced herbivore attack. Ecol. Entomol. 2010;35:240–247. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2311.2010.01179.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Poelman EH, et al. Field parasitism rates of caterpillars on Brassica oleracea plants are reliably predicted by differential attraction of Cotesia parasitoids. Funct. Ecol. 2009;23:951–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2435.2009.01570.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Karasov TL, Horton MW, Bergelson J. Genomic variability as a driver of plant-pathogen coevolution? Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2014;18:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2013.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Karasov TL, et al. The long-term maintenance of a resistance polymorphism through diffuse interactions. Nature. 2014;512:436–440. doi: 10.1038/nature13439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jones JDG, Dangl JL. The plant immune system. Nature. 2006;444:323–329. doi: 10.1038/nature05286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hinton, H. E. Biology of insect eggs. I–III (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1981).

- 60.Margaritis, L. H. Structure and physiology of the eggshell. in Comprehensive Insect Physiology, Piochemistry and Pharmacology (eds. Kerkut, G. A. & Gilbert, L. I.) 15, 153–230 (Pergamon Press, Oxford, 1985).

- 61.Woods HA. Water loss and gas exchange by eggs of Manduca sexta: Trading off costs and benefits. J. Insect Physiol. 2010;56:480–487. doi: 10.1016/j.jinsphys.2009.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rezende GL, et al. Embryonic desiccation resistance in Aedes aegypti: presumptive role of the chitinized Serosal Cuticle. BMC Dev. Biol. 2008;8:82. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-8-82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goltsev Y, et al. Developmental and evolutionary basis for drought tolerance of the Anopheles gambiae embryo. Dev. Biol. 2009;330:462–470. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.02.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jacobs CGC, Rezende GL, Lamers GEM, van der Zee M. The extraembryonic serosa protects the insect egg against desiccation. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biol. Sci. 2013;280:20131082. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wiklund C. Egg-laying patterns in butterflies in relation to their phenology and the visual apparency and abundance of their host plants. Oecologia. 1984;63:23–29. doi: 10.1007/BF00379780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat. Methods. 2012;9:671–675. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. (2014).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.