Abstract

Transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) and fibroblast growth factor (FGF) signaling pathways play important roles in the proliferation and differentiation of lens epithelial cells (LECs) during development. Low dosage bFGF promotes cell proliferation while high dosage induces differentiation. TGFβ signaling regulates LEC proliferation and differentiation as well, but also promotes epithelial-mesenchymal transitions that lead to cataracts. Thus far, it has been difficult to recapitulate the features of germinative LECs in vitro. Here, we have established a LEC culture protocol that uses SB431542 (SB) compound to inhibit TGFβ/Smad activation, and found that SB treatment promoted mouse LEC proliferation, maintained LECs’ morphology and distinct markers including N-cadherin, c-Maf, Prox1, and αA-, αB-, and β-crystallins. In contrast, low-dosage bFGF was unable to sustain those markers and, combined with SB, altered LECs’ morphology and β-crystallin expression. We further found that Matrigel substrate coatings greatly increased cell proliferation and uniquely affected β-crystallin expression. Cultured LECs retained the ability to differentiate into γ-crystallin-positive lentoids by high-dosage bFGF treatment. Thus, a suppression of TGFβ/Smad signaling in vitro is critical to maintaining characteristic features of mouse LECs, especially expression of the key transcription factors c-Maf and Prox1.

Introduction

Cataracts are opacities of the lens and are the leading cause of world blindness according to the World Health Organization1. Although a cataractous lens can be surgically removed and replaced with an artificial lens, many patients cannot get this treatment, especially in developing countries. Therefore, non-surgical treatments or preventative therapies for cataracts are needed, but sorely lacking. Therapeutic development may require improved lens cell culture models in order to better understand the mechanisms of lens transparency and cataractogenesis.

The vertebrate lens is surrounded by a basement membrane capsule, beneath which lies a monolayer of lens epithelial cells (LECs) on the anterior hemisphere and a bulk mass of elongated fiber cells. Throughout life, LECs in a region just anterior to the lens equator known as the germinative zone are the most prone to proliferation and subsequent differentiation into lens fibers2. After intraocular lens implantation, undesired LEC proliferation, differentiation and migration can cause secondary cataracts. Therefore, a thorough understanding of LEC biology is required to understand lens growth, differentiation, and disease.

LECs were first cultured from embryonic chicken by Kirby in 19273. Since then, chicken LECs cultures have been widely used and significantly improved upon, especially by Menko et al.4, 5 and Musil et al.6. For mammalian LEC culture, Mann was the first to culture mouse embryonic LECs and observe cell growth7. After that, human fetal LECs were cultured, which expressed the epithelial marker αB-crystallin and the differentiating fiber cell markers β- and γ-crystallins8, 9. However, LECs isolated from different species including rat10, calf11, monkey12, and human13–16, grew slowly in vitro, and spontaneously differentiated into fiber cells or underwent apoptosis17. Several LEC lines established from rabbit or murine lenses lack appropriate expression of crystallins and their abilities to form differentiated lentoid bodies are uncertain18–20. Immortalized LEC lines generated with recombinant viruses21–23 were unable to differentiate into lentoids or lens fibers. Explant culture is an excellent alternative for mammalian lens culture in which LECs are grown on their native basement membrane capsule in serum free media conditions24, 25. However, explants display restricted cell proliferation, the majority of LECs on explants remain to have cell-cell contact inhibition, such that the most proliferative cells are presumably present at the explant’s edges. For research that benefits from high throughput techniques and large cell numbers, such as drug screening, lens capsule explant culture may not be an optimal choice, due to the large number of donor lenses that would be required and limited number of cells per lens (e.g. 40,000–50,000 LECs on the mouse lens capsule26, 27). At present, it is difficult to expand and maintain distinct properties of mammalian LECs in vitro due to epithelial-mesenchymal transitions (EMT) and cell senescence.

Results from previous studies have demonstrated the importance of basic fibroblast growth factor (bFGF) and transforming growth factor β (TGFβ) on LEC behavior2, 28–30. The capsule explant model was used to show that low concentrations bFGF could maintain LEC proliferation, while high concentrations could promote fiber cell differentiation and lentoid formation31, 32. Further studies show that the TGFβ signaling pathway plays an important role in EMT and the secondary cataract development33, 34. Under stimulation with TGFβ1, LECs lost epithelial identity, underwent EMT, differentiated into myofibroblast-like cells, or underwent apoptosis33–36. Phosphatidylinositol 3-OH kinase (PI3K)/Akt signaling and Snail are necessary for TGF-β induced EMT in LECs37. Inhibition of the TGFβ pathway with the TGFβ type 1 receptor inhibitor, SB431542, prevented or reversed EMT thereby maintaining epithelial identity in various cell types, including human keratinocytes and murine renal tubular epithelial cells38–40.

In this study, we examined the effects of SB431542, bFGF, and Matrigel coating on dissociated mouse LECs in a new medium. We found that a culture condition with SB431542 treatment promoted the proliferation of mouse LECs and supported some identities of lens equatorial epithelial cells in vitro. Low dosage bFGF treatment and Matrigel coating further promoted LEC proliferation, but affected cell morphology and/or expression of β-crystallins. The cultured LECs from mature lenses could be differentiated into lentoids by high dosage bFGF treatment. This culture condition provides an excellent alternative system for a uniform expansion of mouse LECs in vitro, which provides sufficient cells for investigating LEC proliferation, fiber cell differentiation and the regulation of crystallins expression (especially, β-crystallin isoforms) without undesired EMT or apoptosis.

Results

Inhibition of TGFβ signaling with SB431542 is critical for mouse primary cultured LECs in vitro

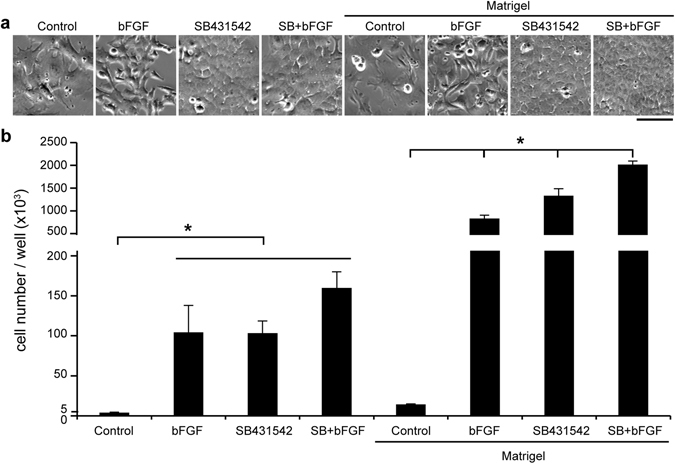

Mouse LECs were isolated from 3–4 week old lenses and cultured under different combinations of bFGF (5 ng/ml) and SB431542 (5 µM), and with or without Matrigel coated substrates (Fig. 1). We found that the LECs in the control groups grew very slowly and had a myofibroblast-like morphology (Fig. 1a), suggesting EMT. Only LECs treated with SB431542 maintained the cuboidal-like cell morphology. Surprisingly, SB431542 treatment alone was also sufficient to promote LEC growth to a similar extent as bFGF treatment did (Fig. 1b). Matrigel coating greatly promoted cell growth, but SB431542 treatment was still required for maintaining the cuboidal-like cell morphology. These data suggest that inhibition of TGFβ signaling with SB431542 is important to maintain cuboidal cell shape and proliferation of LECs in vitro.

Figure 1.

Treatment with SB431542 alone maintains adult mouse LEC morphology and promotes cell growth in vitro. (a) Phase contrast images of adult mouse LECs that were cultured on dishes with or without Matrigel coating, in media supplemented with nothing (Control), 5 ng/ml bFGF, 5 µM SB431542, or SB431542 and bFGF (SB + bFGF). (b) Primary adult mouse LECs were cultured in 6-well plates at a seeding density of 5000 cells per well. The cell counts for each group were determined after one week. N = 3. Scale bar, 100 µm. Two-way ANOVA showed a significant interaction between media composition and Matrigel coating. Post-hoc testing showed that all Matrigel coated conditions were significantly greater than their corresponding uncoated conditions. For uncoated conditions, bFGF, SB, and SB + bFGF groups were not significantly different than each other but were all significantly greater than control. For the coated conditions, all media resulted in significantly different cell counts than each other coated condition. *P < 0.05.

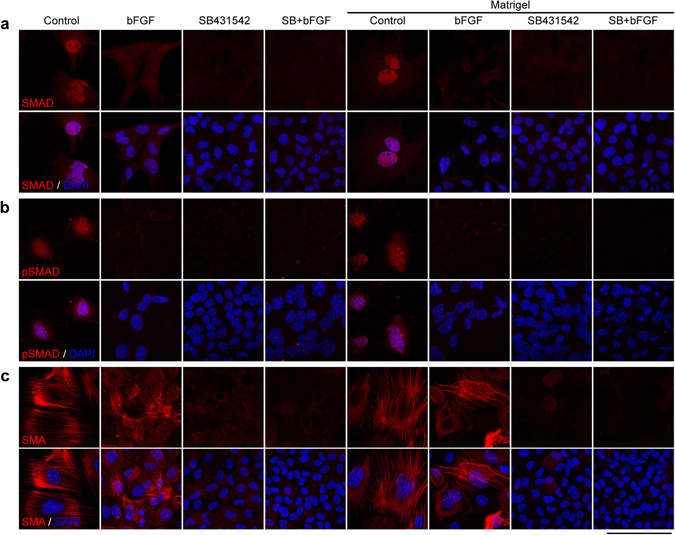

To examine whether there was active TGFβ signaling in the control groups that underwent EMT and whether TGFβ signaling was inhibited by SB431542, we performed immunofluorescence imaging. The results showed SMAD2/3 and phosphorylated SMAD2/3 signals in the nuclei and strong smooth muscle α-actin (SMA) in the cytoplasm of control LECs, but no or very weak signals in the LECs treated with SB431542 (Fig. 2). It was interesting that bFGF treatment also inhibited TGFβ signaling as shown by very weak SMAD2/3 and phosphorylated SMAD2/3 in the nuclei, but had SMA expression, which suggests that bFGF alone was not sufficient to inhibit EMT and maintain the cuboidal morphology of LECs (Figs 1 and 2).

Figure 2.

Inhibition of TGFβ signaling by SB431542. Mouse LECs of different culture groups were immunostained by the antibodies against SMAD2/3 (a), pSMAD2/3 (b) and SMA (c). Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI. Scale bar, 100 µm.

LECs cultured with SB431542 recapitulate lens equatorial epithelial cells marker expression

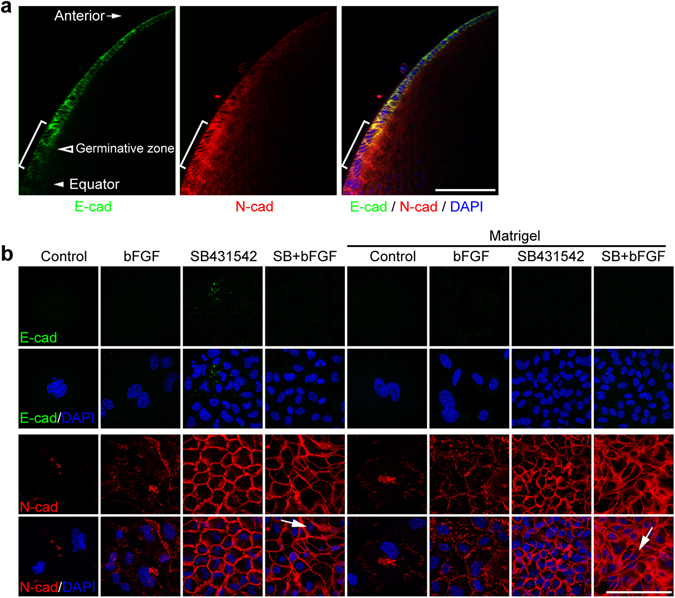

In a stained, intact mouse lens, we observed that E-cadherin expression decreased and N-cadherin expression increased when following LECs from the anterior to the germinative zone and lens equator (Fig. 3a). Immunostaining results of LECs under different culture conditions revealed that LECs lacked obvious E-cadherin expression (Fig. 3b). Few LECs under the control media condition expressed N-cadherin. The majority of bFGF treated LECs had N-cadherin expression to some extent, but it was not uniformly distributed at cell boundaries. All SB431542 treated cuboidal-like LECs displayed uniform distribution of N-cadherin on their cell boundaries. LECs treated with both bFGF and SB431542 showed high expression of N-cadherin, but many cells displayed deformed or elongated cell shape (Fig. 3b). Matrigel coated conditions had no dramatic effects on E-cadherin and N-cadherin expression and cell morphology compared to uncoated conditions (Fig. 3b). LECs without SB431542 treatment often displayed myofibroblast-like cell shapes with enlarged nuclei, expression of strong SMA and reduced expression of N-cadherin, indicating a loss of distinct epithelial cells features (Figs 1–3). These results indicate that these cultured mouse LECs share some distinct features with germinative zone LECs. However, there are obvious differences between these cultured LECs in vitro and germinative zone LECs in vivo, shown below.

Figure 3.

Treatment with SB431542 maintains N-cadherin expression in mouse LECs. (a) Whole-mounted mouse lens stained by antibodies against E-cadherin and N-cadherin. (b) Adult mouse LECs were cultured in different conditions for one week, and immunostained by antibodies against E-cadherin and N-cadherin. Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI. Brackets in a: transitional zone. Arrows in (b) elongated cells. Scale bars, 100 µm.

Presence of SB431542 is essential to maintain the expression of c-Maf and Prox1 but not Pax6

We next examined lens-specific transcription factors to further characterize LEC identity in different culture conditions. Specific transcription factors such as Pax6, c-Maf, and Prox1 are important in determining the cell fate, proliferation and differentiation of LECs41. Pax6 was detected under all culture conditions (Fig. 4a), but both c-Maf and Prox1 were uniformly detected in cells with SB431542 treatment regardless with or without FGF (Fig. 4b,c). The control and bFGF treatment alone were insufficient to support the expression of c-Maf and Prox1. Matrigel coating had no obvious effect on the expression profiles of these transcription factors (The right part of the panels in Fig. 4). Thus, SB431542 treatment is sufficient to support the expression of c-Maf and Prox1 in cultured mouse LECs.

Figure 4.

Treatment with SB431542 maintains c-Maf and Prox1 expression in adult mouse LECs. Mouse LECs of different groups were cultured for one week and immunostained by antibodies against Pax6 (a), c-Maf (b), and Prox1 (c). Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI. Scale bar, 100 µm.

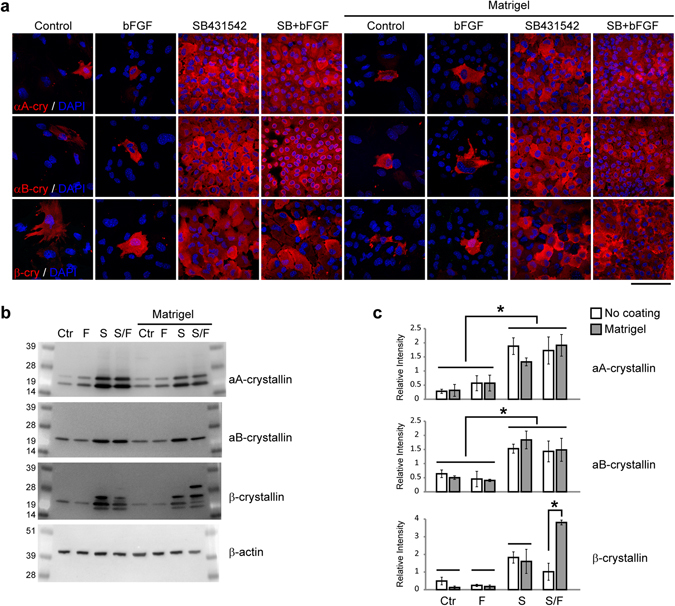

SB431542 treatment promotes the expression of αA-, αB- and β-crystallin in mouse LECs

The expression profiles of different crystallin proteins such as αA-, αB- and β-crystallin are useful markers for monitoring distinct properties of LECs in proliferation and differentiation. We examined both the distribution and level of different crystallins in LECs by immunostaining and western blotting. Very few LECs in control and bFGF treated samples regardless with or without Matrigel coating had αA-, αB- and β-crystallins (Fig. 5a). On the contrary, almost all the cells with SB431542 treatment, regardless with or without bFGF, or Matrigel coating, showed the presence of αA-, αB- and β-crystallins (Fig. 5a). Western blot data confirmed these immunostaining observations and showed that SB431542 treatment elevated the expression of different β-crystallin isoforms in both uncoated and Matrigel coated conditions (Fig. 5b,c). Without Matrigel coating, LECs with SB431542/bFGF treatment had reduced β-crystallin expression when compared to those with SB431542 treatment alone (p value, 0.036). With Matrigel coating, βB1-crystallin (the largest band detected in western blotting42, 43) was detected only in the LECs with SB431542/bFGF treatment (Fig. 5b). These results indicate that SB431542 treatment is critical to maintaining the expression of αA-, αB- and β-crystallin in cultured LECs and Matrigel coating may affect the expression of βB1-crystallin under certain conditions.

Figure 5.

Treatment with SB431542 maintains αA-, αB- and β-crystallin expression in mouse LECs. (a) Mouse LECs were cultured in different conditions for one week, and immunostained by antibodies against αA-, αB- and β-crystallin. Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI. (b) Western blot results showed that proteins of primary adult mouse LECs in each culture condition were probed by the antibodies against αA-, αB-, β-crystallin, and β-actin. (c) Two-way ANOVA showed that only media composition, was important to αA- and αB-crystallins expression. Post-hoc tests showed that Control and bFGF media had less protein expression than SB and SB+bFGF media. β-crystallin levels showed an interaction between media composition and coating. Unlike αA- and αB-crystallins, Matrigel coating combined with SB and FGF significantly increased β-crystallin levels compared to SB+bFGF without coating and other coated conditions. Scale bar, 100 µm. N = 3. *P < 0.05.

Differentiation of LECs into lentoids

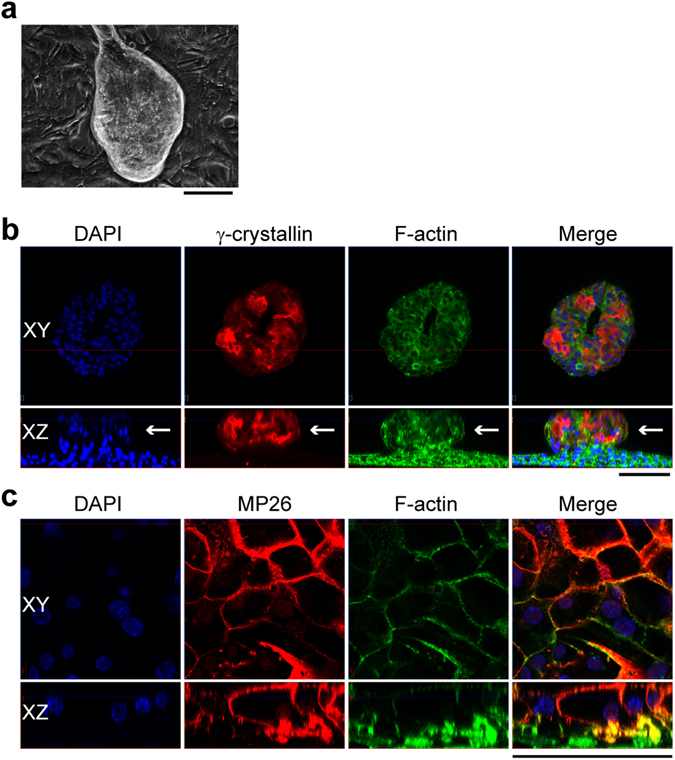

We next examined whether LECs could still differentiate into lentoid bodies. The LECs treated with SB431542 and Matrigel coating were used for differentiation assays. The primary cultured LECs were passaged to Matrigel-coated dishes at a density of 105 cells per 35-mm dish. The medium supplemented with SB431542 was used in the first two days of culture, and then changed to medium supplemented with 200 ng/ml high bFGF, without SB431542. Large lentoid bodies were observed after two to three weeks of high bFGF induction (Fig. 6a) and had varied sizes with diameters of 100–400 µm (See Supplementary Fig. S1). The total surface area of lentoid bodies was about 19 ± 5% of culture dishes. These lentoids expressed fiber cell markers including γ-crystallin and MP26 (Fig. 6b,c). Thus, these LECs have retained the capacity to differentiate into lens fiber-like cells.

Figure 6.

Mouse LECs could be induced to form lentoids in vitro. (a) Phase contrast image of lentoid after three weeks of treatment with 200 ng/ml bFGF. The lentoids were immunostained with antibodies against γ-crystallin (b) and MP26 (c). Cell nuclei were stained by DAPI and F-actin was stained by phalloidin. White arrow, the lentoid from side view. Scale bar, 100 µm.

Discussion

We found that SB431542 treatment, an inhibition of TGFβ/Smad signaling, is essential for maintaining distinct properties of primary cultured mouse LECs in vitro. These cultured mouse LECs express many specific markers of lens equatorial epithelial cells, including the adhesion molecule N-cadherin44, lens-specific transcription factors c-Maf and Prox1, and αA-, αB- and β-crystallins41. Moreover, the proliferation of LECs can be further promoted by Matrigel coating, which partly mimics certain components of lens capsule. The culture conditions with SB431542 treatment and Matrigel coating is highly repeatable and allows one mouse lens containing about 40,000–50,000 cells26, to be expanded into about 6 million cells after 7–10 days in culture. These LECs can be differentiated into lentoid forming lens fibers under high dosage bFGF. Thus, we have overcome difficulties such as EMT and senescence associated with mouse LEC culture in vitro. This LEC culture system provides a complementary approach to lens explant culture systems for studying the proliferation and differentiation of mammalian LECs.

This work suggests that inhibition of TGFβ/Smad pathway is critical for maintaining the proliferation and distinct identity of mouse LECs in vitro. TGFβ is known to have both negative and positive effects on cell proliferation depending on the tissue or cell type45, 46. It induced epithelial growth arrest and apoptosis in mammary, skin, colon, pancreas, liver and prostate, but had opposite effects on cell proliferation in different cell layers of skin46 and affected acinar cell differentiation during pancreas development47. TGFβ signaling is essential for normal lens development and lens fiber differentiation48. TGFβs exist in ocular media and their activities are regulated by inhibitors, such as α2-macroglobulin49 and HtrA350. If not regulated properly, TGFβ could contribute to EMT and cataract formation36. In lens capsule explant culture models, addition of TGFβ1 to the culture media induced LECs to adopt a mesenchymal cell shape, secrete excessive extracellular matrix, differentiate into myofibroblasts, undergo apoptosis and lose lens cell identity33, 34. Inhibiting TGFβ by α2-macroglobulin maintained LEC morphology in vitro 49. SB431542 is a small molecule inhibitor of TGFβ type I receptor40, and could restore cell identity in other epithelial cells in vitro 37–39, but had never been fully characterized in lens epithelial cells. This work reveals that suppression of TGFβ/Smad pathway with SB431542 promotes mouse LEC proliferation, and supports cell morphology and the expression of c-Maf and Prox1.

Previous reports showed that a low concentration of bFGF promotes LECs proliferation and high bFGF promotes differentiation2, 51. bFGF can also counteract TGFβ-induced EMT and apoptosis in rat lens capsule explant culture52. Here we confirm that a low concentration of bFGF (5 ng/ml) promotes the proliferation of mouse LECs, suppressed TGFβ/Smad signaling, but at the same time is insufficient to inhibit SMA expression and maintain several key mouse LECs markers such as αA/αB-crystallins, c-Maf, and Prox1. Also, with bFGF alone, some cells might undergo EMT and adopt elongated cell shapes. Moreover, some cells might differentiate to highly express αA-, αB-, β-crystallins. Matrigel coating does not affect the consequence of low bFGF culture conditions. However, combined treatments of bFGF with SB431542 or bFGF with SB431542 and Matrigel coating alter the expression of β-crystallin isoforms in different manners. This culture system may be useful for studying the regulation of β-crystallin isoforms by FGF and other signaling pathways.

Matrigel is an extracellular protein mixture extracted from Engelbreth-Holm-Swarm mouse sarcoma, containing mainly collagen IV and laminin, and has been used for in vitro culture of various cell types. The lens capsule is composed of several extracellular proteins including collagen IV, laminin and fibronectin, and functions as a basement membrane for LEC attachment, proliferation, migration and differentiation53. Lens cells have membrane bound integrins that bind extracellular matrix proteins and regulate cell proliferation and differentiation54. Here, we observed that LECs in the Matrigel coating group had about 10 times the cell numbers compared to those without Matrigel coating. The effects on primary cultured mouse LECs match the roles of extracellular matrix in vivo, but differ from a previous study that showed that extracellular matrix proteins promoted human LEC line attachment and survival, but not proliferation55. This discrepancy indicates that this mouse LEC culture system may be a better model to study the mechanisms of lens epithelial cell proliferation in vitro than the virus-transfected human lens cell lines altered with unknown changes.

Pax6 is a master transcription factor during mammalian lens development41, and its expression in LECs is directly negatively regulated by TGFβ/SMAD signaling pathway56, 57. Pax6 expression is similar in all culture conditions including the control without bFGF and SB431542, which suggests maintained autoregulation of Pax656. Pax6 controls expression of transcription factors including c-Maf and Prox158 and α-crystallin59. Surprisingly, both c-Maf and Prox1 are barely detectable without SB431542. C-Maf is highly expressed in the equatorial lens cells and activates α- and β-crystallin expression60, and Prox1 regulates lens fiber differentiation61. Presence of both c-Maf and Prox1 induced by SB431542 treatment promotes the expression αA-, αB- and β-crystallins as a part of mechanism to maintain the characteristic features of lens equatorial epithelial cells in vitro.

In conclusion, inhibition of TGFβ pathway by the small molecule SB431542 promotes LEC proliferation and maintains characteristic features of mouse LECs in vitro. Matrigel coating further improves LEC proliferation. These LECs can be induced to differentiate into lentoids by high concentrations of bFGF. This in vitro model provides sufficient cells from an individual animal to study mouse LEC proliferation and differentiation. This model also provides a useful platform for studying lens epithelial cells in pathological conditions and for seeking potential therapeutic targets for cataract prevention. For future work, there are several challenges to overcome: (1) This culture method utilizes FBS and Matrigel that contain small amounts of growth factors with variations between batches. More defined culture protocols will be needed in the future for knowing all growth factors in the medium. The downstream signaling activities of insulin-like growth factor (IGF), platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) and other growth factors are unknown in cultured mouse LECs. Perhaps, testing IGF and PDGF dosages in serum free medium will be a future direction for developing a defined culture medium. (2) Although this method can successfully expand primary mouse LECs, they undergo senescence after two passages. Further modifications are also needed for translational studies in human LECs. (3) Instead of malformed lentoids, defined 3D lens culture models mimic native microenvironments in vitro by using mouse or human LECs will be valuable for investigating fiber differentiation and testing therapeutic reagents.

Materials and Methods

Mouse Strains

Mouse care, breeding, and euthanasia were performed according to an Animal Care and Use Committee (ACUC)–approved animal protocol (University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA) and the ARVO Statement for the Use of Animals in Ophthalmic and Vision Research. Lenses of wild-type 129S4 (129-SvJae) mice at the ages of 3–4 weeks were used for LEC culture.

Primary Lens Cell Culture

Lenses were immediately dissected from enucleated eyeballs of euthanized mice. After removing surrounding tissue, lenses were incubated in 0.05% trypsin-EDTA (Gibco, cat#: 25300-054) at 37 °C for 10 min to further remove any non-lens cells and then transferred to a new dissection tray. Lens capsules were peeled off by forceps and transferred into 100 µl of dispase per pair of lenses (2 U/ml, Sigma, cat#: D4693) in Advanced DMEM-F12 medium (Gibco, cat#: 12634-010). After 5 min of dispase treatment, 100 µl of 10 × TrypLE (Gibco, cat#: A12177-02) was added. After 10 min, the cell suspension was transferred to a new sterile tube and spun down at 1000 rpm for 4 min. The cell pellet was resuspended in culture medium and seeded into culture dishes. The control culture medium (Ctr) was Advanced DMEM/F12, supplemented with 1 × Penicillin-Streptomycin (Gibco, cat#: 15140-122), 1 × GlutaMax (Gibco, cat#: 35050-061), 2% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS, Gibco, cat#: 26140-079), and 1 × B-27 (Gibco, cat#: 17504-044). To test the effects of bFGF (Peprotech, cat#: 100-18B) and SB431542 (Stemgent, cat#: 04-0010-10), the control medium was further supplemented with 5 ng/ml bFGF (F), 5 µM SB431542 (S), or 5 ng/ml bFGF plus 5 µM SB431542 (SF). SB431542 was dissolved in DMSO to make stock solutions. Equal volumes of DMSO without SB431542 were added as vehicle controls to the Ctr and FGF groups. For Matrigel coating, the dishes were coated with Matrigel (Mg, 1:100 in Advanced DMEM/F12, Corning, cat#: 354248) for at least one hour at 37 °C, and washed with Advanced DMEM/F12 medium before seeding cells. A total of 8 different culture conditions (Ctr, F, S, SF, Mg-Ctr, Mg-F, Mg-S, and Mg-SF) were tested at 37 °C with 5% CO2 and 95% humidity incubation.

Proliferation and Differentiation of Primary Cultured LECs

To assay cell proliferation, 5000 cells per well were seeded into 6-well plates with 3 wells per experimental group. Culture medium was changed every day. After one week, total cell number per well was counted.

As differentiation medium, Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1× Penicillin-Streptomycin, 1× GlutaMax, 2% FBS, 1× B-27, and 200 ng/ml bFGF, was used and changed daily.

Western Blot

After one week of culture, LECs were collected in lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM EGTA, 1% Triton X-100, and protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche, Cat#: 11 836 153 001). The cell suspension was sonicated for 10 seconds by a Kontes micro ultrasonic cell disrupter, and then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 10 min. The supernatant was used for experiments. Protein concentration was measured by Coomassie assay (Pierce, cat#: 23200). Equal volumes of 2× sample buffer (0.1 M Tris-PO4, pH 6.8, 4% SDS, 8% Bromophenol blue, 20% Glycerol, 10% 2-mercaptoethanol) was added to the protein solution and mixed well. All procedures were performed on ice. Equal amounts of protein (10 µg) were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred to PVDF membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% non-fat milk and incubated with antibodies against αA-, αB-, β-crystallin, or β-actin (Sigma, cat#: A5441), at 4 °C overnight. After three 5 min washes in TBST (0.15 M NaCl, 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.4, 0.1% Tween 20) buffer, the membranes were incubated in HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies for one hour. After three washes with TBST, protein bands were visualized by an Azure Biosystems c600 imager.

Statistical analysis

Data were reported as means ± standard deviation (s.d.) All experiments were repeated at least three times. To account for the increases in variance with increases in cell counts, cell counts were transformed by putting them to the 1/4th power. Two-way ANOVA was performed on the transformed data followed by Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) comparisons. For western blot analysis, two-way ANOVA was performed followed by Tukey’s HSD comparisons. p-values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Immunostaining

Cultured mouse LECs after one week of culture and lentoids after three weeks of treatment with 200 ng/ml bFGF were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) for 15 min and then washed with PBS 3x, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton-X100 for one hour, and were incubated with specific primary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer overnight at 4 °C. For pSMAD2/3 staining, cells were permeabilized with methanol prior to blocking. The primary antibodies included SMA (Sigma, cat#A2547), SMAD2/3 (BD, cat#610843), pSMAD2/3 (Cell Signaling, cat#8828 S), αA-, αB- and γ-crystallin (generously provided by Dr. Joseph Horwitz at Jules Stein Eye Institute), β-crystallin (generously provided by J. Samuel Zigler at the National Eye Institute), Pax6 (Santa Cruz Tech, cat#sc-53108), c-Maf (Bethyl Laboratories, cat#: A300-613A), and Prox1 (EMD Millipore, cat#: AB5475), MP26 (generously provided by Joseph Horwitz at the Jules Stein Eye Institute of UCLA). After incubation with primary antibodies, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated in secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories) diluted in blocking buffer for one hour. The cells were then placed in mounting medium containing DAPI (Vector Laboratories, cat#: H-1200) and imaged by confocal microscopy (Zeiss, LSM700).

For whole-mount staining, mouse lenses were fixed in 1% PFA at 4 °C overnight and then washed with PBS 3 × 30 min on a shaker, blocked with 5% normal goat serum in 0.3% Triton X-100 for 2 h, incubated in primary antibodies (E-cadherin, Invitrogen cat#13-1900; N-cadherin, Invitrogen, cat#33-3900) diluted in blocking buffer at 4 °C for 1 day. The lenses were then washed with PBS three times for 30 min on a shaker, and then incubated in secondary antibodies diluted in blocking buffer at 4 °C overnight, washed with PBS 3 × 30 min, incubated in DAPI solution diluted in PBS for 1 h, and then imaged by confocal microscopy (Zeiss, LSM700).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants of the National Institutes of Health, EY 013849 (X.G.) and HL121450 (S.L.), and California Institute of Regenerative Medicine Postdoctoral Fellowship (E.W.).

Author Contributions

D.W. and X.G. designed the experiments. D.W., E.W. and X.G. wrote the manuscript. D.W. performed all the experiments. E.W., K.L. and C.X. assisted animal samples, cell culture and western blot. S.L. helped with data analysis and discussion.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at doi:10.1038/s41598-017-07619-5

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Resnikoff S, et al. Global data on visual impairment in the year 2002. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2004;82:844–851. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW. Growth factor regulation of lens development. Dev Biol. 2005;280:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2005.01.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kirby DB. The Cultivation of Lens Epithelium in Vitro. J Exp Med. 1927;45:1009–1016. doi: 10.1084/jem.45.6.1009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Menko AS, Klukas KA, Johnson RG. Chicken embryo lens cultures mimic differentiation in the lens. Dev Biol. 1984;103:129–141. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(84)90014-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Banks EA, Yu XS, Shi Q, Jiang JX. Promotion of lens epithelial-fiber differentiation by the C-terminus of connexin 45.6 – a role independent of gap junction communication. Journal of Cell Science. 2007;120:3602–3612. doi: 10.1242/jcs.000935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Musil LS, Beyer EC, Goodenough DA. Expression of the gap junction protein connexin43 in embryonic chick lens: molecular cloning, ultrastructural localization, and post-translational phosphorylation. J Membr Biol. 1990;116:163–175. doi: 10.1007/BF01868674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mann I. Tissue Cultures of Mouse Lens Epithelium. Br J Ophthalmol. 1948;32:591–596. doi: 10.1136/bjo.32.9.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nagineni CN, Bhat SP. Maintenance of the synthesis of alpha B-crystallin and progressive expression of beta Bp-crystallin in human fetal lens epithelial cells in culture. Dev Biol. 1988;130:402–405. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(88)90446-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hamada Y, Okada TS. In vitro differentiation of cells of the lens epithelium of human fetus. Exp Eye Res. 1978;26:91–97. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(78)90156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.FitzGerald PG, Goodenough DA. Rat lens cultures: MIP expression and domains of intercellular coupling. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1986;27:755–771. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.V D Veen J, Heyen CF. Lens cells of the calf in continuous culture. Nature. 1959;183:1137–1138. doi: 10.1038/1831137a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ogiso M, Takehana M, Kobayashi S, Hoshi M. Expression of sialylated Lewisx gangliosides in cultured lens epithelial cells from rhesus monkey. Exp Eye Res. 1998;66:765–773. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mamo JG, Leinfelder PJ. Growth of lens epithelium in culture. I. Characteristics of growth. AMA Arch Ophthalmol. 1958;59:417–419. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1958.00940040123014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pomerat CM, Littlejohn L., Jr. Observations on tissue culture of the human eye. South Med J. 1956;49:230–237. doi: 10.1097/00007611-195603000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sundelin K, Petersen A, Soltanpour Y, Zetterberg M. In vitro growth of lens epithelial cells from cataract patients - association with possible risk factors for posterior capsule opacification. Open Ophthalmol J. 2014;8:19–23. doi: 10.2174/1874364101408010019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arita T, Lin LR, Susan SR, Reddy VN. Enhancement of differentiation of human lens epithelium in tissue culture by changes in cell-substrate adhesion. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1990;31:2395–2404. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Musil LS. Primary cultures of embryonic chick lens cells as a model system to study lens gap junctions and fiber cell differentiation. J Membr Biol. 2012;245:357–368. doi: 10.1007/s00232-012-9458-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reddan JR, Chepelinsky AB, Dziedzic DC, Piatigorsky J, Goldenberg EM. Retention of lens specificity in long-term cultures of diploid rabbit lens epithelial cells. Differentiation. 1986;33:168–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1986.tb00422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sax CM, Dziedzic DC, Piatigorsky J, Reddan JR. Analysis of alpha-crystallin expression in cultured mouse and rabbit lens cells. Exp Eye Res. 1995;61:125–127. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(95)80066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Krausz E, et al. Expression of Crystallins, Pax6, Filensin, CP49, MIP, and MP20 in lens-derived cell lines. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2120–2128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ibaraki N, et al. Human Lens Epithelial Cell Line. Experimental Eye Research. 1998;67:577–585. doi: 10.1006/exer.1998.0551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Andley UP, Rhim JS, Chylack JLT, Fleming TP. Propagation and immortalization of human lens epithelial cells in culture. Investigative Ophthalmology & Visual Science. 1994;35:3094–3102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lenstra JA, et al. Gene expression of transformed lens cells. Experimental Eye Research. 1982;35:549–554. doi: 10.1016/S0014-4835(82)80069-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell MT, McAvoy JW. Onset of fibre differentiation in cultured rat lens epithelium under the influence of neural retina-conditioned medium. Exp Eye Res. 1984;39:83–94. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(84)90117-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McAvoy JW, Fernon VT. Neural retinas promote cell division and fibre differentiation in lens epithelial explants. Curr Eye Res. 1984;3:827–834. doi: 10.3109/02713688409000795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bassnett S, Shi Y. A method for determining cell number in the undisturbed epithelium of the mouse lens. Mol Vis. 2010;16:2294–2300. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dawes LJ, et al. Interactions between lens epithelial and fiber cells reveal an intrinsic self-assembly mechanism. Dev Biol. 2014;385:291–303. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2013.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Robinson ML. An essential role for FGF receptor signaling in lens development. Seminars in Cell & Developmental Biology. 2006;17:726–740. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2006.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Garcia CM, et al. The function of FGF signaling in the lens placode. Developmental Biology. 2011;351:176–185. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madakashira BP, et al. Frs2α enhances fibroblast growth factor-mediated survival and differentiation in lens development. Development. 2012;139:4601–4612. doi: 10.1242/dev.081737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McAvoy JW, Chamberlain CG. Fibroblast growth factor (FGF) induces different responses in lens epithelial cells depending on its concentration. Development. 1989;107:221–228. doi: 10.1242/dev.107.2.221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW. Structural analysis of lens epithelial explants induced to differentiate into fibres by fibroblast growth factor (FGF) Exp Eye Res. 1989;49:479–494. doi: 10.1016/0014-4835(89)90056-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu J, Hales AM, Chamberlain CG, McAvoy JW. Induction of cataract-like changes in rat lens epithelial explants by transforming growth factor beta. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1994;35:388–401. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hales AM, Schulz MW, Chamberlain CG, McAvoy JW. TGF-beta 1 induces lens cells to accumulate alpha-smooth muscle actin, a marker for subcapsular cataracts. Curr Eye Res. 1994;13:885–890. doi: 10.3109/02713689409015091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hales AM, Chamberlain CG, Dreher B, McAvoy JW. Intravitreal injection of TGFbeta induces cataract in rats. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1999;40:3231–3236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.de Iongh RU, Wederell E, Lovicu FJ, McAvoy JW. Transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition in the lens: a model for cataract formation. Cells Tissues Organs. 2005;179:43–55. doi: 10.1159/000084508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cho HJ, Baek KE, Saika S, Jeong MJ, Yoo J. Snail is required for transforming growth factor-beta-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition by activating PI3 kinase/Akt signal pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2007;353:337–343. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.12.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Kane D, et al. SMAD inhibition attenuates epithelial to mesenchymal transition by primary keratinocytes in vitro. Exp Dermatol. 2014;23:497–503. doi: 10.1111/exd.12452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Das S, Becker BN, Hoffmann FM, Mertz JE. Complete reversal of epithelial to mesenchymal transition requires inhibition of both ZEB expression and the Rho pathway. BMC Cell Biol. 2009;10:94. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Inman GJ, et al. SB-431542 Is a Potent and Specific Inhibitor of Transforming Growth Factor-β Superfamily Type I Activin Receptor-Like Kinase (ALK) Receptors ALK4, ALK5, and ALK7. Molecular Pharmacology. 2002;62:65–74. doi: 10.1124/mol.62.1.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ogino H, Yasuda K. Sequential activation of transcription factors in lens induction. Dev Growth Differ. 2000;42:437–448. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2000.00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ueda Y, Duncan MK, David LL. Lens proteomics: the accumulation of crystallin modifications in the mouse lens with age. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:205–215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lampi KJ, Shih M, Ueda Y, Shearer TR, David LL. Lens proteomics: analysis of rat crystallin sequences and two-dimensional electrophoresis map. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2002;43:216–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu L, Overbeek PA, Reneker LW. Systematic Analysis of E-, N- and P-cadherin Expression in Mouse Eye Development. Experimental Eye Research. 2002;74:753–760. doi: 10.1006/exer.2002.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alexandrow MG, Moses HL. Transforming growth factor beta and cell cycle regulation. Cancer Res. 1995;55:1452–1457. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Siegel PM, Massague J. Cytostatic and apoptotic actions of TGF-beta in homeostasis and cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3:807–821. doi: 10.1038/nrc1208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bottinger EP, et al. Expression of a dominant-negative mutant TGF-beta type II receptor in transgenic mice reveals essential roles for TGF-beta in regulation of growth and differentiation in the exocrine pancreas. EMBO J. 1997;16:2621–2633. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.10.2621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Iongh RU, et al. Requirement for TGFbeta receptor signaling during terminal lens fiber differentiation. Development. 2001;128:3995–4010. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.20.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schulz MW, Chamberlain CG, McAvoy JW. Inhibition of transforming growth factor-beta-induced cataractous changes in lens explants by ocular media and alpha 2-macroglobulin. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:1509–1519. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tocharus J, et al. Developmentally regulated expression of mouse HtrA3 and its role as an inhibitor of TGF-beta signaling. Dev Growth Differ. 2004;46:257–274. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2004.00743.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chamberlain CG, McAvoy JW. Induction of lens fibre differentiation by acidic and basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF) Growth Factors. 1989;1:125–134. doi: 10.3109/08977198909029122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mansfield KJ, Cerra A, Chamberlain CG. FGF-2 counteracts loss of TGFbeta affected cells from rat lens explants: implications for PCO (after cataract) Mol Vis. 2004;10:521–532. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Danysh BP, Duncan MK. The lens capsule. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:151–164. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Walker J, Menko AS. Integrins in lens development and disease. Exp Eye Res. 2009;88:216–225. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2008.06.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oharazawa H, Ibaraki N, Lin LR, Reddy VN. The effects of extracellular matrix on cell attachment, proliferation and migration in a human lens epithelial cell line. Exp Eye Res. 1999;69:603–610. doi: 10.1006/exer.1999.0723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Grocott T, et al. The MH1 domain of Smad3 interacts with Pax6 and represses autoregulation of the Pax6 P1 promoter. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:890–901. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl1105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shubham K, Mishra R. Pax6 interacts with SPARC and TGF-beta in murine eyes. Mol Vis. 2012;18:951–956. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Cvekl A, Duncan MK. Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms of gene regulation during lens development. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2007;26:555–597. doi: 10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yang Y, et al. Regulation of alphaA-crystallin via Pax6, c-Maf, CREB and a broad domain of lens-specific chromatin. EMBO J. 2006;25:2107–2118. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ring BZ, Cordes SP, Overbeek PA, Barsh GS. Regulation of mouse lens fiber cell development and differentiation by the Maf gene. Development. 2000;127:307–317. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.2.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wigle JT, Chowdhury K, Gruss P, Oliver G. Prox1 function is crucial for mouse lens-fibre elongation. Nat Genet. 1999;21:318–322. doi: 10.1038/6844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.