Abstract

Objectives

The aims of this study were to evaluate whether serum pancreatic enzyme levels could be used to aid screening for chronic pancreatitis (CP).

Methods

170 healthy volunteers were screened and prospectively enrolled in the control group. 150 patients who were diagnosed with calcific CP were enrolled in the patient group by retrospective review. Serum amylase and lipase levels were compared between the 2 groups.

Results

The mean values ± SD of the control group were compared with those of the patient group for serum amylase level (48.1 ± 13.2 vs 34.8 ± 17.2 U/L, P < 0.001) and serum lipase level (26.4 ± 11.3 vs 16.3 ± 11.2 U/L, P < 0.001). On the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis for amylase level, area under the curve was 0.740 (95% confidence interval), and sensitivity and specificity were 38.7% and 94.1%, respectively, with a cutoff value of 27.5 U/L. On the receiver operating characteristic curve analysis for lipase level, area under the curve was 0.748 (95% confidence interval), and sensitivity and specificity were 33.3% and 95.9%, respectively, with a cutoff value of 10.5 U/L.

Conclusions

Our results suggest that low serum pancreatic enzyme levels can be used to aid in detection of CP.

Keywords: amylase, lipase, pancreatitis, chronic, diagnosis

Chronic pancreatitis (CP) is defined as progressive inflammatory destruction of pancreatic secretory parenchyma with replacement by fibrous tissue, resulting generally in irreversible dysfunction of both endocrine and exocrine pancreatic function.1,2 Chronic pancreatitis is usually diagnosed based on clinical–historical information, results of imaging findings, pancreatic functional tests, and chronically or intermittently elevated pancreatic serum enzymes.3,4 Serum amylase and lipase are obtained in nearly all suspected patients with CP. When low serum values are obtained, does the clinician use this information to aid in CP diagnosis or is the value ignored (or perhaps considered laboratory error)?

The lipase expression can be detected to varying extent in the lingual salivary glands, gastric fundus, duodenum, liver, and the adipose tissue. But the main organ of lipase secretion is the pancreas. Total pancreatectomy patients commonly have low serum lipase levels.5,6 In CP, damage may affect pancreatic enzyme synthesis and entry into and clearance from the circulation. This may result in low serum enzyme levels. In the pathologic tissue analysis, pancreatic tissue in CP demonstrates decrease of both amylase and lipase activity. Notably, amylase activity is more decreased than lipase activity.7

The correlation between severe exocrine insufficiency and low pancreatic juice enzyme levels is well known. Older reports note low serum pancreatic enzymes, especially lipase, in up to 50% of patients with CP.1,8–10 Although the role of elevated serum lipase levels as a valid tool for diagnosing acute pancreatitis and acute episodes of CP has been well established, the low serum lipase levels in CP have not yet attracted much recent attention. Low serum amylase and lipase levels in CP are not discussed in several recent publications.3,11–18 Serum amylase and lipase remain as readily available and inexpensive tests. Methodologies for pancreatic enzymes measurement reports from older literature earlier than the year 2000 are different from that used in many modern laboratories.

The aims of this study were as follows: (1) to determine if amylase and lipase levels as assessed by modern-day methods are low in a portion of patients with CP, (2) to compare serum pancreatic enzyme levels between patients with CP and healthy controls, and (3) to evaluate whether serum pancreatic enzyme levels could be used to aid screening for CP.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Healthy volunteers were screened and prospectively enrolled in the control group. Patients who were diagnosed with calcific CP and underwent endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) were enrolled in the patient group. Serum amylase and lipase levels were compared between the 2 groups. This study was approved by Indiana University Institutional Review Board before the commencement of the study.

Control Group

Healthy paid volunteers were screened and prospectively enrolled in the control group from April 1, 2014, to March 15, 2015. Informed consent was obtained from all such volunteers before enrollment. Inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria are represented in Table 1. Aliquots blood samples from a single draw were analyzed for serum pancreatic enzyme levels.

TABLE 1.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria for Control Group

| Inclusion criteria |

|

| Exclusion criteria |

|

Patient Group

Patients who were diagnosed with calcific CP and underwent ERCP in Indiana University Health between January 1, 2012, and May 31, 2014, were enrolled in the patient group. All information was obtained by retrospective medical record review from patients identified through the IU ERCP procedure database. Calcific CP was diagnosed based on clinical symptoms and pancreatic calcifications detected by imaging studies (computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or ERCP). Serum amylase and lipase were obtained and analyzed a few hours before the ERCP by the routine clinical laboratory of the Indiana University Health. Patients were excluded from the study if they were younger than 18 years or older than 79 years or pregnant or had a condition, such as chronic kidney disease, previous gastrointestinal or pancreatic surgery that may affect serum amylase and lipase levels.

Analysis of Serum Pancreatic Enzymes

All serum amylase level and lipase level in both groups were measured using the same automated chemistry analyzer (AU 5822 analyzer; Beckman Coulter, Inc, Brea, Calif). Our validated reference range for amylase and lipase are between 19 and 86, and between 7 and 59 U/L, respectively.

Serum amylase and lipase levels were compared between the 2 groups. If a patient had blood drawn several times during enrollment period, the lowest level among the results was used for analysis. Patients with an abnormal high serum pancreatic enzyme level before ERCP were enrolled in the study only when their levels returned to below the upper limit of normal and pain was resolved or improved after ERCP.

Statistical Analysis

Pearson χ2 test and Student t test were used to analyze the differences between the 2 groups. Student t test was used to analyze the variables among the subgroups in control group. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was constructed and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated to determine the diagnostic performance of serum pancreatic enzymes. The levels of variables were described as mean ± SD. P < 0.05 was considered significant. Statistical analysis was performed with IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 22.0.0; SPSS Inc, Chicago, Ill).

RESULTS

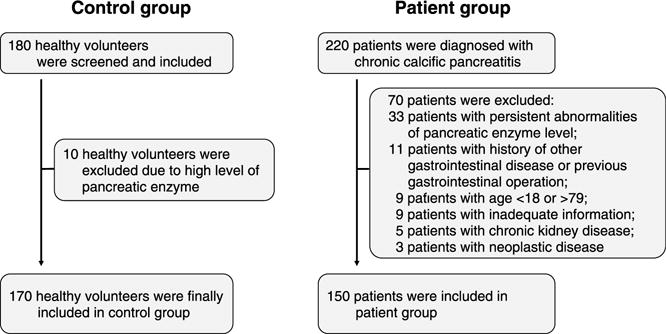

A total of 180 healthy volunteers were screened and enrolled in the control group. Ten healthy volunteers were excluded due to abnormal high levels of pancreatic enzymes (5.6%), resulting in a total of 170 healthy volunteers finally enrolled in the control group (44 men, 126 women with a mean age of 48.1 years; range, 20–78 years). A total of 220 patients were identified with calcific CP and underwent 370 ERCP procedures, of which 70 patients were excluded: 33 patients with persistent elevations of pancreatic serum enzyme levels; 11 patients with history of other gastrointestinal disease or previous gastrointestinal operation; 9 patients younger than 18 years or older than 79 years; 9 patients with inadequate information; 5 patients with chronic kidney disease; 3 patients with neoplastic disease. A total of 150 patients (76 men, 74 women with a mean age of 54.0 years; range, 23–78 years) were enrolled in the patient group (Fig. 1).

FIGURE 1.

Study enrollment flowchart. A total of 180 healthy volunteers were screened and 170 volunteers were enrolled in the control group. A total of 220 patients were diagnosed with chronic calcific pancreatitis and 150 patients were enrolled in the patient group.

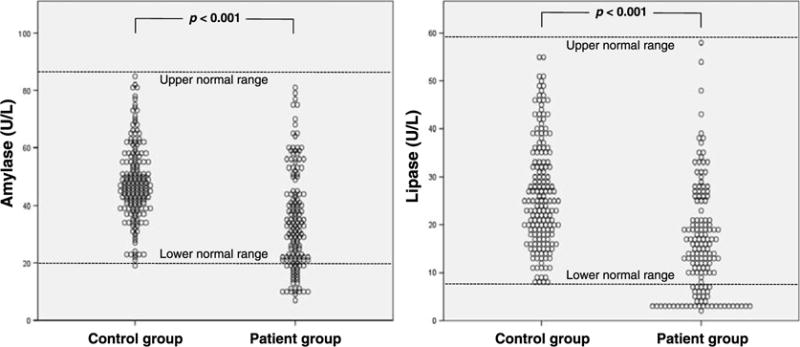

The characteristics of the study participants are presented in Table 2. There were significant differences in mean age (mean values ± SD; 48.1 ± 15.9 vs 54.0 ± 12.2, respectively, P < 0.001) and sex ratio (male/female; 44:126 vs 76:74, respectively, P < 0.001) between control group and patient group due to differences of frequency of volunteer subgroups. The mean serum amylase level was significantly higher in the control group compared with that of the patient group (reference range, 19–86 U/L: 48.1 ± 13.2 vs 34.8 ± 17.2 U/L, respectively, P < 0.001). The mean lipase level was also significantly higher in the control group compared with that of the patient group (reference range, 7–59 U/L: 26.4 ± 11.3 vs 16.3 ± 11.2 U/L, respectively, P < 0.001) (Fig. 2).

TABLE 2.

Baseline Characteristics of Control Group and Patient Group

| Control Group (n = 170) |

Patient Group (n = 150) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y | 48.1 ± 15.9 | 54.0 ± 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Sex (male) | 44 (25.9) | 76 (50.7) | <0.001 |

| Serum amylase, U/L* | 48.1 ± 13.2 | 34.8 ± 17.2 | <0.001 |

| Serum lipase, U/L† | 26.4 ± 11.3 | 16.3 ± 11.2 | <0.001 |

Values are presented as mean values ± SD or n (%).

Normal value: 19–86 U/L.

Normal value: 7–59 U/L.

FIGURE 2.

Results of serum pancreatic enzyme level analysis between control group and patient group. Scatter dot graphs show significantly higher levels of serum pancreatic enzymes in the control group compared with those of the patient group (Student t test).

Because of nonequal distribution of sex and age in the volunteer group, subgroup analyses were done in the control for the evaluation of age-related and sex-related differences. Between younger-age (age, 18–49 years) and older-age (age, 50–79 years) subgroups, there was no significant difference of serum amylase and lipase levels (amylase: 46.9 ± 11.6 vs 45.0 ± 11.4 U/L, respectively, P = 0.326; lipase: 24.1 ± 10.1 vs 25.9 ± 10.7 U/L, respectively, P = 0.303). Between male and female subgroups, there was no significant difference of serum amylase and lipase levels (amylase: 46.5 ± 14.2 vs 48.7 ± 12.8 U/L, respectively, P = 0.362; lipase: 29.6 ± 13.5 vs 25.3 ± 10.2 U/L, respectively, P = 0.058) (Table 3).

TABLE 3.

Age-Related and Sex-Related Subgroup Analysis in Control Group

| Age-Related Subgroup

|

P | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, 18–49 y (n = 78) |

Age, 50–79 y (n = 73) |

||

| Serum amylase, U/L* | 46.9 ± 11.6 | 45.0 ± 11.4 | 0.326 |

| Serum lipase, U/L† | 24.1 ± 10.1 | 25.9 ± 10.7 | 0.303 |

| Sex-Related Subgroup

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Male (n = 44) | Female (n = 126) | ||

| Serum amylase, U/L* | 46.5 ± 14.2 | 48.7 ± 12.8 | 0.362 |

| Serum lipase, U/L† | 29.6 ± 13.5 | 25.3 ± 10.2 | 0.058 |

Values are presented as mean values ± SD.

Normal value: 19–86 U/L.

Normal value: 7–59 U/L.

Interestingly, no one in the healthy volunteer group had values of serum amylase and lipase levels below the reference range. Using mean value minus 2 SD of control group, 45 (30%) patients had low amylase level (mean level, 16.5 ± 4.7 U/L), 28 (18.7%) patients had low lipase level (mean level, 3.1 ± 0.4 U/L), 16 (10.7%) patients had both levels low, and 57 (38.0%) patients had either of both levels low.

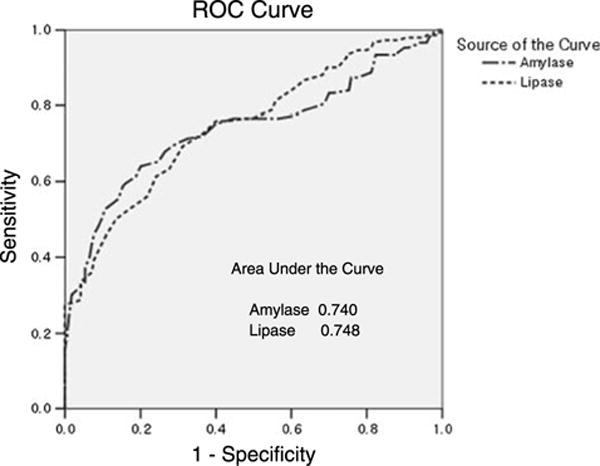

We next generated the ROC curves to assess the potential usefulness of low serum pancreatic enzyme levels as diagnostic modalities for CP (Fig. 3 and Table 4). On the ROC curve analysis for amylase level, AUC was 0.740 (95% confidence interval [CI]), and sensitivity and specificity were 70.0% and 70.6%, respectively, with an optimum diagnostic cutoff value of 41.5 U/L. Specificity of serum amylase level for diagnosis of CP was 94.1% with a cutoff value of 27.5 U/L. On the ROC curve analysis for lipase level, AUC was 0.748 (95% CI), and sensitivity and specificity were 69.3% and 68.8%, respectively, with an optimum diagnostic cutoff value of 19.5 U/L (Fig. 3 and Table 3). Specificity of serum lipase level for diagnosis of CP was 95.9% with a cutoff value of 10.5 U/L. If both serum amylase and lipase levels are lower than the reference range, sensitivity and specificity are 10.7% (16/150) and 100% (170/170), respectively. If either serum amylase or lipase level is lower than the reference range, sensitivity and specificity are 30.0% (45/150) and 100% (170/170), respectively.

FIGURE 3.

ROC curve analysis for the diagnostic performance of serum amylase and lipase level for detection of chronic calcific pancreatitis. AUCs are 0.740 (95% CI) for serum amylase level and 0.748 (95% CI) for serum lipase level.

TABLE 4.

Sensitivity and Specificity of Serum Pancreatic Enzyme Levels for CP Using Variable Cutoff Values

| Level, U/L | Sensitivity, % | Specificity, % | Positive Predictive Value, % | Negative Predictive Value, % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum amylase (normal: 19–86 U/L) | 18.5 | 16.0 | 100 | 100 | 57.4 |

| 27.5 | 38.7 | 94.1 | 85.3 | 63.5 | |

| 32.5 | 49.3 | 90.6 | 82.2 | 67.0 | |

| 38.5 | 64.0 | 80.0 | 73.8 | 71.6 | |

| 41.5 | 70.0 | 70.6 | 67.8 | 72.7 | |

| Serum lipase (normal: 7–59 U/L) | 7.5 | 27.3 | 100 | 100 | 60.9 |

| 10.5 | 33.3 | 95.9 | 87.7 | 62.0 | |

| 13.5 | 45.3 | 89.4 | 79.1 | 65.0 | |

| 15.5 | 52.7 | 82.9 | 73.1 | 66.5 | |

| 19.5 | 69.3 | 68.8 | 66.2 | 71.8 |

DISCUSSION

Nearly every patient with clinically suspected CP has a serum amylase and lipase drawn. If values are elevated, suspicions for pancreatic diseases are increased and further studies are often done. If values are normal, no specific next step is suggested. If values are low, many clinicians (personal observation) have no increased suspicion of CP. Our study was done to reevaluate the utility of low serum pancreatic enzyme levels for diagnosing CP.

Our results show that patients with established calcific CP (with obviously advanced disease) had significantly lower levels of serum pancreatic enzymes than the healthy control group. Furthermore, when compared to the healthy control group, 57 (38%) patients of 150 patients had at least 1 enzyme level more than 2 SD below the levels of the control group. These results suggest that low levels in routine pancreatic serum enzyme tests should not be deemed “normal” nor dismissed clinically unimportant.

Low serum lipase and amylase levels in CP were observed long ago.1,8–10 Could this observation apply to currently used laboratory methodology? This study confirms prior studies and emphasizes the diagnostic values of low serum pancreatic enzymes. We conducted an ROC curve analysis to determine the diagnostic possibility of detecting patients with a CP. As can be seen in Figure 3 and Table 4, the AUC for serum amylase level and serum lipase level were both greater than 0.7, with sensitivity and specificity ranging between 65% and 70% depending on the optimal cutoff value. These values were somewhat different from the values presented by the diagnostic modalities of CP, but the specificity increased rapidly to beyond 90% with lower cutoff values. Specificity of serum amylase was 94.1% with cutoff level of 27.5 U/L and 100% when the level was lower than 18.5 U/L. Specificity of serum lipase was 95.9% when the cutoff level was 10.5 U/L and 100% when the cutoff level was lower than 7.5 U/L. These results suggest that normal subjects do not show values below a certain level and that this cutoff may be useful for the diagnosis of CP. The clinician should not ignore low serum amylase and lipase levels as they suggest CP in absence of pancreas resection surgery.

Previously reported noninvasive or indirect laboratory tests have highly variable accuracy in suggesting a diagnosis of CP depending on the severity of the disease.17,18 Serum trypsin level has similarly been found to be low in up to 50% of patients with calcific CP and moderate sensitivity in late disease state with steatorrhea. Some reports mentioned this in discussion of CP, whereas the sensitivity is at least intermediate, the specificity is near 100%.9,17,18 This would seem to have equal diagnostic values for amylase and lipase low values. The serum trypsin assay has not replaced amylase and lipase in clinical practice due to requiring several days to obtain a result, and 2- to 4-fold more expensive than serum amylase and lipase levels in our hospital.

Our contention is clinically to take further advantage of serum amylase and lipase values which are already drawn on virtually all suspected pancreatic disease patients. Low analysis cost of serum amylase and lipase levels are especially valuable in third world countries. Clinicians should not overlook low pancreatic enzyme values but should suspect CP and recommend further detailed examinations.

A large-scale, prospective, follow-up study based on our results would be able to establish critical diagnostic basis, such as using serum pancreatic enzyme level as an economic, long-term follow-up in patients with symptoms of CP but unremarkable findings from routine tests. If a patient’s levels are below certain levels or continuously decreasing, more accurate diagnostic tests can be recommended more confidently for confirmation of CP. Our study was not designed to detect the difference in pancreatic enzyme levels depending on the severity of CP or in the course of disease progression from recurrent pancreatitis to chronic calcific pancreatitis in a long-term follow-up. These could be addressed in future studies.

Limitations of our study are as follows. Healthy volunteers were enrolled prospectively but the subjects in the patient group were enrolled retrospectively. Although there is no statistical difference of serum amylase and lipase level between male and female subgroup, men and women were not evenly distributed across the healthy group due to low rate of volunteering in men, especially younger men. Patients with early-stage CP were not involved in this comparative study, and those differences in terms of the severity or cause of CP could not be investigated. We are not aware of other clinical conditions with low serum amylase and lipase level (except for resection surgery of pancreas or salivary glands, chronic salivary gland disease, or pancreatitis with extensive necrosis, and others).

In conclusion, our results suggest that low serum amylase and lipase levels should not be discarded for patients, and that further testing may be warranted if there is the possibility of underlying pancreatic disease. Also, low serum amylase and lipase levels as detected by modern methodology laboratory can be used to aid in the screening of CP. These results confirm previous studies stating up to 50% sensitivity for CP diagnosis. Further studies in noncalcific CP are needed to clarify the pancreatic enzyme levels about the demographic factors and severity status of CP.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gwangil Kim, MD, for the devoted cooperation during the study.

This work was partially funded by a gift from Maryam Al-Rashed and family of Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, who had no involvement in the conduct of this study.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ammann RW, Akovbiantz A, Largiader F, et al. Course and outcome of chronic pancreatitis. Longitudinal study of a mixed medical-surgical series of 245 patients. Gastroenterology. 1984;86:820–828. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steer ML, Waxman I, Freedman S. Chronic pancreatitis. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1482–1490. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199506013322206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Forsmark CE. Management of chronic pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:1282–1291. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Braganza JM, Lee SH, McCloy RF, et al. Chronic pancreatitis. Lancet. 2011;377:1184–1197. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61852-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hayakawa T, Kondo T, Shibata T, et al. Enzyme immunoassay for serum pancreatic lipase in the diagnosis of pancreatic diseases. Gastroenterol Jpn. 1989;24:556–560. doi: 10.1007/BF02773885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurooka S, Kitamura T. Properties of serum lipase in patients with various pancreatic diseases. J Biochem. 1978;84:1459–1466. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a132269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Apple F, Benson P, Preese L, et al. Lipase and pancreatic amylase activities in tissues and in patients with hyperamylasemia. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:610–614. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/96.5.610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benini L, Caliari S, Vaona B, et al. Variations in time of serum pancreatic enzyme levels in chronic pancreatitis and clinical course of the disease. Int J Pancreatol. 1991;8:279–287. doi: 10.1007/BF02952721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldberg DM, Durie PR. Biochemical tests in the diagnosis of chronic pancreatitis and in the evaluation of pancreatic insufficiency. Clin Biochem. 1993;26:253–275. doi: 10.1016/0009-9120(93)90124-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nagata A, Homma T, Oguchi H, et al. Study of chronic alcoholic pancreatitis by means of serial pancreozymin-secretin tests. Digestion. 1986;33:135–145. doi: 10.1159/000199285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Conwell DL, Wu BU. Chronic pancreatitis: making the diagnosis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1088–1095. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, editors. Harrison’s Principles of Internal Medicine. 18th. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goldman L, Schafer AI, editors. Goldman’s Cecil Medicine. 24th. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Feldman M, Friedman LS, Brandt LJ, editors. Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease: Pathophysiology, Diagnosis, Management. 9th. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gupte AR, Forsmark CE. Chronic pancreatitis. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30:500–505. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Conwell DL, Lee LS, Yadav D, et al. American Pancreatic Association practice guidelines in chronic pancreatitis: evidence-based report on diagnostic guidelines. Pancreas. 2014;43:1143–1162. doi: 10.1097/MPA.0000000000000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chowdhury RS, Forsmark CE. Review article: pancreatic function testing. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:733–750. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2003.01495.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lieb JG, 2nd, Draganov PV. Pancreatic function testing: here to stay for the 21st century. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:3149–3158. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.3149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]