Abstract

Background

The role of cervical muscle (neck) strength in traumatic brain and spine injury and chronic neck pain disorders is an area of active research. Characterization of the normal ranges of neck strength in healthy young adults is essential to designing future investigations of how strength may act as a modifier for risk and progression in head and neck disorders.

Objective

To develop a normative reference database of neck strength in a healthy young adult population; and to evaluate the relationship of neck strength to anthropometric measurements.

Design

Cross-sectional.

Setting

An academic medical center research institution.

Participants

157 healthy young adults (ages 18–35) had their neck strength measured with fixed frame dynamometry (FFD) during one visit to establish a normative neck strength database.

Interventions

Not applicable.

Main Outcome Measurements

Peak and average strength of the neck muscles was measured in extension, forward flexion, and right and left lateral flexion using FFD. The ranges of peak and average neck strength were characterized and correlated with anthropometric characteristics.

Results

157 subjects (84 male, 73 female; average age 27 years) were included in the normative sample. Neck strength ranged from 38–383 Newtons in men and from 15–223 Newtons in women. Normative data are provided for each sex in all four directions. Weight, BMI, neck circumference, and estimated neck muscle volume were modestly correlated with neck strength in multiple directions (correlation coefficients <0.43). In a multivariate regression model, weight in women and neck volume in men were significant predictors of neck strength.

Conclusions

Neck strength in healthy young adults exhibits a broad range, is significantly different in men than in women and correlates only modestly with anthropometric characteristics.

Introduction

Cervical musculature is essential for maintenance of posture and stabilization of the head. Moreover, cervical muscle strength (neck strength) may modify risk for mild traumatic brain injury in sports and accidents,1, 2 and is related to development and progression of chronic postural neck pain.3, 4 The description of the normal reference ranges of neck strength are essential to facilitate characterization of the role of neck strength in different types of head and neck disorders and investigate how strength can be leveraged to improve function and mitigate injury. The aims of this study are to develop a normative reference database of neck strength in a healthy young adult population and to evaluate the relationship of neck strength to anthropometric measurements.

The normal ranges of neck strength has been characterized in multiple populations including high school and collegiate athletes,1, 5 children,6 and across the lifespan.7–12 Across these studies, neck strength has consistently been found to be higher in men than in women and inconsistently correlated with factors including age, handedness, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), and neck circumference. However, there is no database published focusing on healthy young subjects that may be germane to studies of amateur, collegiate, semi-professional, and professional athletes. Additionally, few studies have examined combinations of anthropometric measures that more closely model neck muscle volume as a surrogate of neck strength.

In this study we characterized neck strength in 157 healthy young subjects using fixed frame dynamometry (FFD), a technique where resistance to muscle contraction is against a dynamometer mounted to a frame or a wall. Handheld dynamometry, by contrast, relies on a human tester to generate resistance to muscle contraction and so is more susceptible to tester-based error or bias. We also obtained multiple anthropometric measures, which were evaluated as potential indices of neck strength individually and in combinations designed to approximate neck muscle volume.

Methods

Subjects

Healthy subjects, ages 18–35, were recruited from a university student and employee population from December 2015 to June 2016. Subjects were not recruited from any particular athletic subset. Exclusion criteria included neck or shoulder pain or injury that limited mobility or impacted daily activity, medical illnesses, surgery or trauma affecting the spine, or a history of arthritis. Each subject included in the normative database underwent a single testing session with FFD. Ten of these subjects also participated in a sub-study to establish the reliability of the method of strength measurement. All data were collected using RedCap, a secure, web-based application designed to support data capture for research studies.13 The study was reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board and complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act. Written informed consent was obtained for all subjects.

Reliability of Strength Measurement

In order to determine reliability of our method of FFD for measuring neck strength, ten subjects (five men and five women) participated in an additional four testing sessions over a two-week period. Each testing session occurred on a different day. In order to account for variability attributable to subject positioning and/or verbal coaching, for each subject, two different raters alternated across the four visits. The sequence of raters was counterbalanced across subjects.

Neck Strength Testing Procedure

All strength testing was performed using the microFET2 dynamometer (Hoggan Scientific, Salt Lake City, Utah). Neck strength was measured in four directions: extension, forward flexion, and right and left lateral flexion. The testing order for the four directions was randomized by the RedCap Software.

The testing setup for each direction is shown in Supplementary Figure 1. During testing sessions subjects were seated in a custom built rigid chair with two seatbelts attached just below the axillae and at the waist. To minimize contributions from thoracic and abdominal musculature, seatbelts were tightened until subjects were unable to separate their torso from the back of the chair. To minimize contributions from the scapular and pectoral muscles and to prevent from bracing against the chair, subjects’ arms were positioned with 90-degree abduction at the shoulders and 90-degree flexion at the elbows.14 To minimize contributions of lower extremity muscles, the subject was asked to rest their feet lightly on top of an empty cardboard box and instructed not to exert any pressure on the box during testing.15 Trials where the box was crushed by the subject were discarded and repeated. The position of the dynamometer was adjusted for each direction: on the occipital protuberance for extension, above the eyebrows for forward flexion, and above the corresponding ear for right lateral flexion and left lateral flexion.

Subjects were encouraged to push against dynamometer continuously with full effort for 3–4 seconds during each trial with verbal coaching. Three trials were completed for each direction with a 5 second rest between trials and a 30 second rest between directions. The dynamometer records peak force for each 3-second trial in Newtons (N).

Anthropometric Measurements

Height, weight, neck circumference, neck length, and head circumference were measured on each subject. Neck circumference was taken immediately cranial to the thyroid cartilage, with the head in a neutral position. Neck length was measured from the most prominent vertebral spinous process (the seventh cervical vertebra) to the occipital protuberance with the subjects’ chin relaxed towards the chest and the tape measure flush against the curve of the neck. Head circumference was measured at the brow ridge and occipital protuberance. Subjects were asked to self-identify handedness as right-handed, left-handed, or ambidextrous. The secondary anthropometric measures included body-mass index (BMI; weight divided by the square of height) and an estimation of cylindrical neck volume calculated using the product of neck length and the square of neck circumference divided by the constant 4 π.

Data Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 13.1. All data were tested for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test.16 Because the extant literature has varied in its use of either the peak trial value or the average value across trials for analysis, we performed all analyses using both values. In theory, the peak trial value more closely approximates the true maximal strength generation capacity of the muscle.

Reliability of FFD for neck strength measurement was characterized using the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC).17 These reliability metrics were calculated for the two visits with the same rater (intra-rater reliability), and comparing two visits with different raters (inter-rater reliability). A random effects model for absolute agreement between raters was used.

In the normative sample we characterized the ranges of neck strength in men and women. Unpaired T-tests were used to compare average and peak neck strength between men and women. Paired t-tests were used to compare right lateral flexion and left lateral flexion for each subject, with separate tests in right handed and left-handed subjects. Pearson’s correlations were performed, separately for men and women, to assess the relationship of neck strength to each of the anthropometric measures (height, weight, head circumference, neck circumference, neck length, BMI, and neck volume) and age. Multiple linear regressions were calculated to predict neck strength in each direction based on height, weight, and neck volume (as a composite of neck length and neck circumference) in men and women separately.

Results

Reliability of Strength Measurement

The inter- and intra-rater reliability was characterized in ten subjects, five men and five women. For inter-rater reliability, in women the ICCs ranged from 0.60 (CI −0. 16–0.90) for right lateral flexion to 0.91 (CI 0.66–0.98) for forward flexion; in men the ICCs ranged from 0.88 (CI 0.60–0.98) for forward flexion to 0.95 (CI 0.81–0.99) for extension. For intra-rater reliability, in women the ICCs ranged from 0.70 (CI 0.20–0.91) for right lateral flexion to 0.96 (CI 0.86–0.99) for extension; in men the ICCs ranged from 0.72 (CI 0.21–0.92) for forward flexion to 0.94 (CI 0.79–0.98) for extension.

Characterizing Normal Neck Strength and Its Relationship to Anthropometrics

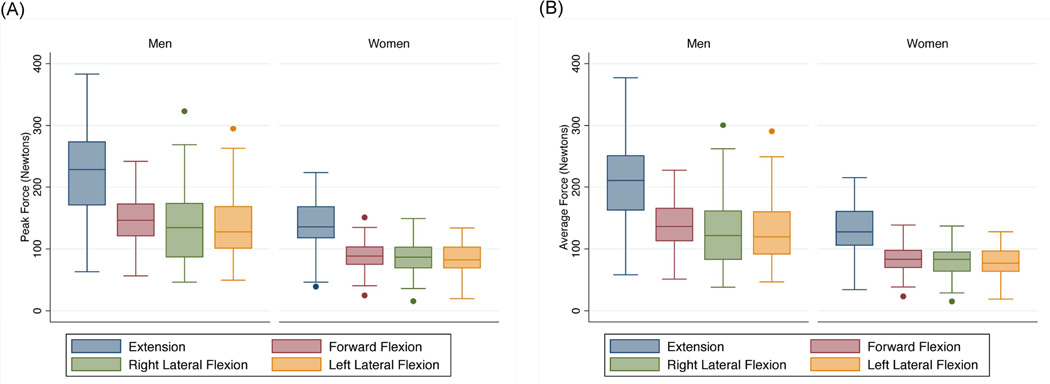

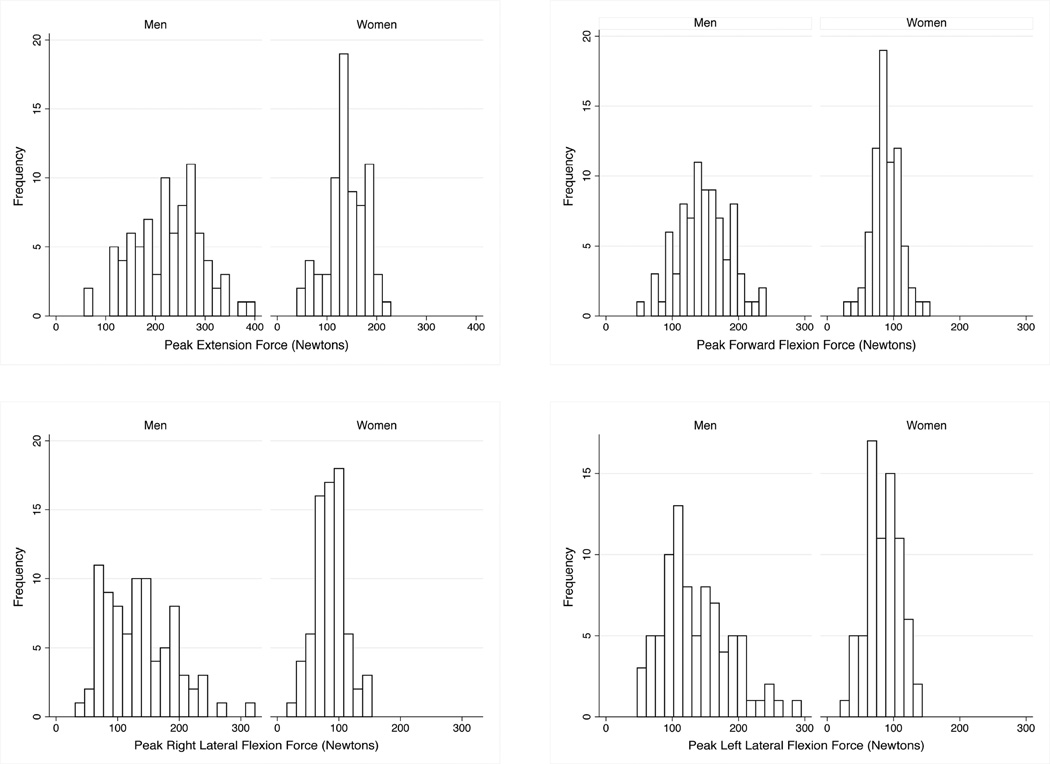

Characteristics of the 157 subjects enrolled are presented in Table 1B. Across the four directions, peak neck strength ranged from 46–383 N in men and 24–223 N in women; and average neck strength ranged from 38–377 N in men and 15–215 N in women (Tables 2 and 3, and Figures 1 and 2). Strength did not differ between right lateral flexion and left lateral flexion in either right handed or left handed individuals (Paired T-test, p-values >.38; data not shown). Men exhibited significantly greater strength than in women in all four directions (Unpaired T-test, p-values <.001).

Table 1.

Subject characteristics for the normative sample. All values shown as mean (standard deviation) except for percent right-handed (% R handed). Age is given in years.

| Subgroup | N | Age | Height | Weight | BMI | Neck Length | Neck Circum | Head Circum | % R Handed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | 157 | 27.0 (3.1) | 171.4 (9.0) | 72.0 (14.4) | 24.4 (3.9) | 18.2 (2.4) | 35.4 (3.8) | 57.4 (1.8) | 86.0 |

| Men | 84 | 27.0 (3.2) | 176.8 (7.2) | 78.6 (13.6) | 25.1 (3.6) | 18.8 (2.6) | 38.2 (2.4) | 58.2 (1.7) | 85.7 |

| Women | 73 | 27.1 (3.0) | 165.0 (6.2) | 64.4 (11.8) | 23.7 (4.2) | 17.5 (1.9) | 32.3 (2.2) | 56.4 (1.5) | 86.3 |

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics for neck strength (in Newtons) in men and women. A) Values calculated from peak of three trials. (B) Values calculated from average across three trials. Standard deviation (SD).

| (2A) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | |

| Men | Extension | 223.6 | 69.2 | 228.3 | 63.2 | 383.1 |

| Forward Flexion | 147.3 | 37.9 | 146.2 | 56.5 | 241.6 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 136.0 | 55.7 | 134.4 | 46.3 | 323.1 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 136.5 | 51.2 | 127.5 | 49.4 | 294.6 | |

| Women | Extension | 138.8 | 38.8 | 135.7 | 39.2 | 223.4 |

| Forward Flexion | 89.2 | 21.7 | 88.6 | 24.9 | 150.9 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 86.0 | 25.3 | 86.8 | 15.6 | 149.1 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 84.3 | 24.1 | 82.3 | 19.6 | 133.9 | |

| (2B) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Mean | SD | Median | Min | Max | |

| Men | Extension | 207.6 | 65.7 | 210.6 | 58.3 | 377.2 |

| Forward Flexion | 138.1 | 36.8 | 136.2 | 51.2 | 227.1 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 126.4 | 52.3 | 121.6 | 38.1 | 300.2 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 127.4 | 49.6 | 119.6 | 46.6 | 290.1 | |

| Women | Extension | 129.4 | 38.5 | 127.6 | 34.3 | 215.1 |

| Forward Flexion | 83.6 | 20.7 | 83.2 | 23.3 | 138.5 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 80.1 | 24.0 | 83.1 | 15.1 | 137.1 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 78.9 | 23.1 | 76.8 | 19.0 | 127.7 | |

Table 3.

Percentile cut points for neck strength (in Newtons) in men and women. A) Values calculated from peak of three trials. (B) Values calculated from average across three trials.

| (3A) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |

| Men | Extension | 113.9 | 126.4 | 171.1 | 228.3 | 273.0 | 305.7 | 332.9 |

| Forward Flexion | 80.1 | 100.1 | 121.3 | 146.2 | 172.7 | 190.9 | 202.9 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 64.5 | 69.4 | 87.2 | 134.4 | 173.6 | 209.6 | 233.2 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 64.1 | 76.1 | 101.2 | 127.5 | 168.4 | 208.3 | 231.8 | |

| Women | Extension | 67.2 | 86.3 | 117.9 | 135.7 | 168.2 | 187.8 | 197,6 |

| Forward Flexion | 57.4 | 62.7 | 75.2 | 88.6 | 103.2 | 113.0 | 127.3 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 41.8 | 55.6 | 69.4 | 86.8 | 102.8 | 113.0 | 127.7 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 41.8 | 54.7 | 69.4 | 82.3 | 102.8 | 116.6 | 124.2 | |

| (3B) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | 5th | 10th | 25th | 50th | 75th | 90th | 95th | |

| Men | Extension | 104.0 | 118.4 | 162.8 | 210.6 | 250.5 | 292.2 | 314.3 |

| Forward Flexion | 73.0 | 92.6 | 113.2 | 136.2 | 165.5 | 183.5 | 194.8 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 59.3 | 66.2 | 83.0 | 121.6 | 161.4 | 199.4 | 217.8 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 58.0 | 68.1 | 91.7 | 119.6 | 159.9 | 194.0 | 217.6 | |

| Women | Extension | 58.7 | 80.7 | 105.9 | 127.6 | 160.6 | 179.0 | 185.6 |

| Forward Flexion | 51.0 | 58.7 | 70.0 | 83.2 | 97.8 | 110.2 | 113.9 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | 40.0 | 49.2 | 64.1 | 83.1 | 95.1 | 108.1 | 118.1 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | 39.8 | 50.4 | 63.8 | 76.8 | 96.7 | 106.1 | 114.2 | |

Figure 1.

Box plots showing normal ranges of (A) peak and (B) average neck strength in men and women in extension, forward flexion, and right and left lateral flexion.

Figure 2.

Histograms showing the distribution of neck strength in men and women in (A) extension, (B) forward flexion, and (C) right and (D) left lateral flexion. Values calculated from peak of three trials.

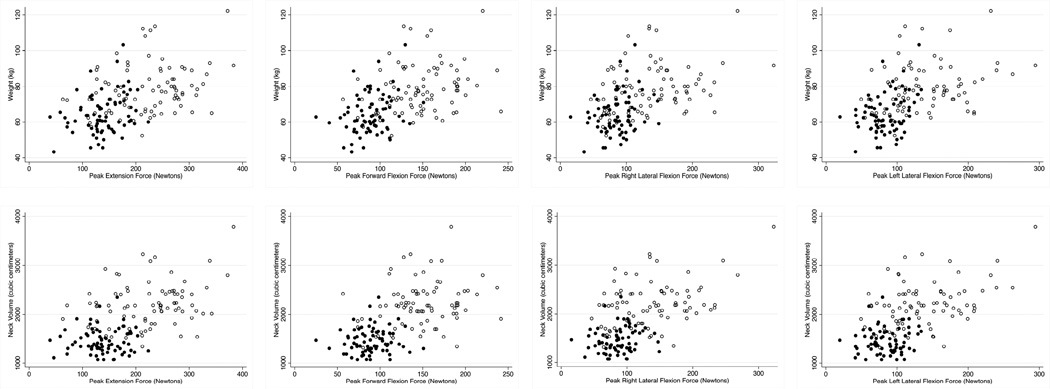

Associations of neck strength and anthropometrics measures are presented in Table 4 and Figure 3. For one male subject neck length and head circumference could not be accurately measured. In both men and in women, there were significant positive correlations between neck strength and weight and BMI. In men only, neck strength was positively correlated with head circumference, neck length, neck circumference, and neck volume. In multivariate regression, in men only, neck volume was a significant predictor of right and left lateral flexion strength, with neck strength increasing 0.04 N for every additional 1 cc of neck volume. In women, only weight was a significant predictor of extension and left lateral flexion strength, with neck strength increasing 1.0–1.4 N for every additional 1 kg of weight.

Table 4.

Pearson’s correlations of neck strength with anthropometric measures. A) Values calculated from peak of three trials. (B) Values calculated from average across three trials.

| (4A) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Age | Height | Weight | Neck Length | Neck Circum | Head Circum | BMI | Neck Volume | |

| Men | Extension | −0.1 | 0.2* | 0.3* | 0.2 | 0.3* | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.3** |

| Forward Flexion | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.3* | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2* | 0.2* | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3* | 0.2* | 0.2* | 0.2*** | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3* | 0.3* | 0.2* | 0.4*** | |

| Women | Extension | −0.1 | 0.08 | 0.3* | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2* | 0.0 |

| Forward Flexion | −0.2 | 0.08 | 0.3* | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.00 | 0.3* | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3* | 0.1 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.07 | 0.3** | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3* | 0.1 | |

| (4A) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Direction | Age | Height | Weight | Neck Length | Neck Circum | Head Circum | BMI | Neck Volume | |

| Men | Extension | −0.1 | 0.2* | 0.3** | 0.2 | 0.3** | 0.2 | 0.2* | 0.3** |

| Forward Flexion | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.3* | 0.2 | 0.2** | 0.2* | 0.3* | 0.3* | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.2* | 0.2* | 0.4*** | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3** | 0.3* | 0.2* | 0.4*** | |

| Women | Extension | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.0 |

| Forward Flexion | −0.2 | 0.1 | 0.2* | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | |

| Right Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.0 | 0.3* | 0.0 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3* | 0.2 | |

| Left Lateral Flexion | −0.1 | 0.1 | 0.3** | −0.1 | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.3* | 0.1 | |

p-value<.05,

p-value<.01,

p-value<.001

Figure 3.

Correlations between anthropometric measures (weight and neck volume) and neck strength in men and women in extension, forward flexion, and right and left lateral flexion. Men shown with open circles, women shown with filled in circles. Values calculated from peak of three trials.

Discussion

Our method of neck strength measurement with FFD demonstrates moderate to high intra- and inter-rater reliability suggesting that single visit measurements with FFD are an appropriate way to capture neck strength. Our sample of 157 healthy young adults demonstrates the broad distribution of normal neck strength. Neck strength in extension, for example, varies across individuals by as much as 300 N in men and over 180 N in women. A number of other studies have characterized isometric neck strength with similar subject positioning (i.e. seated, rather than prone, supine, or standing) in healthy adults: Jordan et al. (n=100 healthy adults, ages 21–69), Chiu et al. (n=91 healthy adults, ages 20–84), Garces et al. (n=94 healthy adults, ages 20–60+), and Salo et al. (n=220 healthy women, ages 20–59). Additionally, two younger reference populations include Lavallee et al. (n=91 healthy children and adolescents, ages 6–23) and Hildenbrand et al. (n=149 high school and college athletes, ages 14–23). Another very large sample of children, Collins et al. (n=6,662 high school athletes), was described using handheld dynamometry. The normal ranges of neck strength found in our sample are similar to those of prior studies that used similar methodology. As has been previously reported,18 we found men to be significantly stronger than women in all directions tested. In contrast to prior studies, we did not identify a difference in right lateral flexion and left lateral flexion based on handedness.

It is worth noting that while many studies capture maximum isometric concentric contraction, there are a variety of approaches to measurement of neck muscle strength that reflect eccentric muscle strength, dynamic force generation, and sustained contraction strength (muscle endurance)18–20. There are also other directions of muscle contraction that may be measured including rotational strength that we did not measure here. These different parameters have a range of potential applications and may be strong predictors of dysfunction in injury prevention and progression21 and should be the focus of future descriptive studies.

Correlations of Anthropometrics with Neck Strength

If anthropometric measures indexed neck strength they might provide a simple and inexpensive surrogate for neck strength measurement. However, we found that anthropometric measures, such as weight, height, and neck circumference and length and BMI, only modestly correlate with neck strength (r<.32). Overall, the most significant predictor of neck strength we identified was biological sex, with men stronger than women in all directions. Prior studies have identified relationships between neck strength and height, weight, and BMI,9, 10, 12 and shown sex differences among these relationships.8 Neck volume, calculated as a proxy for neck muscle volume, was found to correlate with force in all directions in men, but not in women. The lack of correlation between neck strength and neck volume in women may reflect relative sexual dimorphisms in body fat composition or distribution,22 with neck size being less reflective of muscle mass in women compared with men. This was supported by the results of the multivariate analysis, which showed that neck volume was an independent predictor of neck strength in men, but not in women. Previous studies have also shown a decline in neck strength with age.8, 11, 12 The lack of a significant correlation of neck strength and age, given the restriction of the sample to individuals under 35 years, is unsurprising; prior results have shown neck strength is maintained until at least the seventh decade.8, 10

Given the substantial degree of normal variation in any given anthropometric measurement, it is unlikely that a single metric would be an accurate and reliable index of neck strength, which depends on multiple physical factors and in large part on subject effort during testing. Thus it is unlikely that direct neck strength measurement can be replaced by estimations derived from anthropometric measurements. However, when considering neck-related injuries (e.g. whiplash, cervical sprain, concussion), these anthropometrics may modify or predict outcomes independently of their association with strength and thus should be measured in concert with explicit strength measurements.

Study Limitations

This study aims to provide reference ranges for neck strength in a sample of healthy young adults, and correlate strength with anthropometrics. Our reference population was defined using FFD with a custom apparatus and thus the normative data may not be comparable to studies using other FFD resistance systems or handheld dynamometry. Additionally, we characterized exclusively maximal isometric contraction strength and thus these data may not be applicable to investigations examining other dimensions of neck muscle function including muscle endurance or rotational strength.

Conclusion

Our study found that neck strength ranges widely across healthy young adults and differs significantly between the sexes, but is only modestly correlated with anthropometric characteristics. Studies that aim to characterize the role of neck strength in modifying risk for injury and dysfunction will require relevant well-characterized control populations against which athletes and young adults with head and neck injury can be compared. Our findings take an important step toward addressing these scientific and clinical needs.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding sources: NIH R01 NS082432; Dana Foundation David Mahoney Neuroimaging Program; Einstein Research Fellowship; NIH/National Center for Advancing Translational Science (NCATS) Einstein-Montefiore CTSA Grant Number UL1TR001073

The authors would like to thank Liane Hunter for her feedback on the manuscript.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

This research was presented at the AAPM&R Annual Assembly in 2015.

Device Status: the Microfet2 dynamometer (Hoggan Scientific) used in this study is registered with the FDA but is not approved for any specific clinical indications.

References

- 1.Collins CL, Fletcher EN, Fields SK, Kluchurosky L, Rohrkemper MK, Comstock RD, et al. Neck strength: a protective factor reducing risk for concussion in high school sports. The journal of primary prevention. 2014;35(5):309–319. doi: 10.1007/s10935-014-0355-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Viano DC, Casson IR, Pellman EJ. Concussion in professional football: biomechanics of the struck player--part 14. Neurosurgery. 2007;61(2):313–327. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000279969.02685.D0. discussion 27–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ylinen J, Salo P, Nykanen M, Kautiainen H, Hakkinen A. Decreased isometric neck strength in women with chronic neck pain and the repeatability of neck strength measurements. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2004;85(8):1303–1308. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2003.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gilchrist I, Storr M, Chapman E, Pelland L. Neck Muscle Strength Training in the Risk Management of Concussion in Contact Sports: Critical Appraisal of Application to Practice. J Athl Enhancement. 2015;4(2) [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hildenbrand KJ, Vasavada AN. Collegiate and high school athlete neck strength in neutral and rotated postures. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2013;27(11):3173–3182. doi: 10.1519/JSC.0b013e31828a1fe2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lavallee AV, Ching RP, Nuckley DJ. Developmental biomechanics of neck musculature. Journal of biomechanics. 2013;46(3):527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2012.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cagnie B, Cools A, De Loose V, Cambier D, Danneels L. Differences in isometric neck muscle strength between healthy controls and women with chronic neck pain: the use of a reliable measurement. Archives of physical medicine and rehabilitation. 2007;88(11):1441–1445. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2007.06.776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jordan A, Mehlsen J, Bulow PM, Ostergaard K, Danneskiold-Samsoe B. Maximal isometric strength of the cervical musculature in 100 healthy volunteers. Spine. 1999;24(13):1343–1348. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199907010-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salo PK, Ylinen JJ, Malkia EA, Kautiainen H, Hakkinen AH. Isometric strength of the cervical flexor, extensor, and rotator muscles in 220 healthy females aged 20 to 59 years. The Journal of orthopaedic and sports physical therapy. 2006;36(7):495–502. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2006.2122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu TT, Lam TH, Hedley AJ. Maximal isometric muscle strength of the cervical spine in healthy volunteers. Clinical rehabilitation. 2002;16(7):772–779. doi: 10.1191/0269215502cr552oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Staudte HW, Duhr N. Age- and sex-dependent force-related function of the cervical spine. European spine journal : official publication of the European Spine Society, the European Spinal Deformity Society, and the European Section of the Cervical Spine Research Society. 1994;3(3):155–161. doi: 10.1007/BF02190578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garces GL, Medina D, Milutinovic L, Garavote P, Guerado E. Normative database of isometric cervical strength in a healthy population. Medicine and science in sports and exercise. 2002;34(3):464–470. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200203000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. Journal of biomedical informatics. 2009;42(2):377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vernon HT, Aker P, Aramenko M, Battershill D, Alepin A, Penner T. Evaluation of neck muscle strength with a modified sphygmomanometer dynamometer: reliability and validity. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1992;15(6):343–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almosnino S, Pelland L, Stevenson JM. Retest reliability of force-time variables of neck muscles under isometric conditions. Journal of athletic training. 2010;45(5):453–458. doi: 10.4085/1062-6050-45.5.453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shapiro SS, Wilk MB. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples) Biometrikia. 1965;52(3–4):591–611. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Weir JP. Quantifying test-retest reliability using the intraclass correlation coefficient and the SEM. Journal of strength and conditioning research / National Strength & Conditioning Association. 2005;19(1):231–240. doi: 10.1519/15184.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dvir Z, Prushansky T. Cervical muscles strength testing: methods and clinical implications. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2008;31(7):518–524. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.O'Leary SP, Vicenzino BT, Jull GA. A new method of isometric dynamometry for the craniocervical flexor muscles. Phys Ther. 2005;85(6):556–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jull GA, O'Leary SP, Falla DL. Clinical assessment of the deep cervical flexor muscles: the craniocervical flexion test. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 2008;31(7):525–533. doi: 10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jull G, Kristjansson E, Dall’Alba P. Impairment in the cervical flexors: a comparison of whiplash and insidious onset neck pain patients. Manual therapy. 2004;9(2):89–94. doi: 10.1016/S1356-689X(03)00086-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Janssen I, Heymsfield SB, Wang ZM, Ross R. Skeletal muscle mass and distribution in 468 men and women aged 18–88 yr. Journal of applied physiology. 2000;89(1):81–88. doi: 10.1152/jappl.2000.89.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.