Abstract

Background

Studying animal cognition in a social setting is associated with practical and statistical challenges. However, conducting cognitive research without disturbing species-typical social groups can increase ecological validity, minimize distress, and improve animal welfare. Here, we review the existing literature on cognitive research run with primates in a social setting in order to determine how widespread such testing is and highlight approaches that may guide future research planning.

Survey Methodology

Using Google Scholar to search the terms “primate” “cognition” “experiment” and “social group,” we conducted a systematic literature search covering 16 years (2000–2015 inclusive). We then conducted two supplemental searches within each journal that contained a publication meeting our criteria in the original search, using the terms “primate” and “playback” in one search and the terms “primate” “cognition” and “social group” in the second. The results were used to assess how frequently nonhuman primate cognition has been studied in a social setting (>3 individuals), to gain perspective on the species and topics that have been studied, and to extract successful approaches for social testing.

Results

Our search revealed 248 unique publications in 43 journals encompassing 71 species. The absolute number of publications has increased over years, suggesting viable strategies for studying cognition in social settings. While a wide range of species were studied they were not equally represented, with 19% of the publications reporting data for chimpanzees. Field sites were the most common environment for experiments run in social groups of primates, accounting for more than half of the results. Approaches to mitigating the practical and statistical challenges were identified.

Discussion

This analysis has revealed that the study of primate cognition in a social setting is increasing and taking place across a range of environments. This literature review calls attention to examples that may provide valuable models for researchers wishing to overcome potential practical and statistical challenges to studying cognition in a social setting, ultimately increasing validity and improving the welfare of the primates we study.

Keywords: Cognition, Primate, Animal welfare, Social, Methodology, Publication trends

Introduction

The study of animal cognition has a long history that has undergone a general evolution from topics such as self-awareness and whether animals possess human-like language capacities to studies of how animals learn in and navigate social worlds (Beran et al., 2014; Seyfarth & Cheney, 2017). Corresponding with this shift in focus, there has been an increasing interest in studying primate cognition in social environments that reflect the species’ natural history (Cronin & Hopper, 2017). However, implementing cognitive research in a social setting introduces several practical and statistical challenges. Here, we provide a review of publications that have tested primate cognition in a social context in order to provide an overview of the state of social testing in primate cognition research, and present strategies researchers have employed to overcome common challenges.

Testing primate cognition while subjects were isolated from social partners was the norm in the early years of primate cognition research. Rigorously controlled conditions that excluded social influences were the standard. The Wisconsin General Test Apparatus (WGTA), a setup in which a subject was isolated in a test cage and presented with an array of choices, was a widely adopted approach to studying the minds of other primates (Harlow, 1949; Suomi & Leroy, 1982). Although individual testing is still commonplace and does confer certain experimental advantages, researching primate cognition while subjects are in a social group can lend a number of advantages over individual testing.

Testing primates in a social environment that reflects their natural history maintains a more natural test environment that may be essential for an individual primate’s learning and typical cognitive performance (Drea, 2006; see also Koski & Burkart, 2015). For the large majority of primate species, this would be a social setting. Whereas individual testing may shed light on the cognitive capacities of primates, testing in a reduced social environment does little to inform us of the behaviors that would typically be expressed under natural social conditions and are thus subject to natural selection. Collaboration, prosociality, and social learning in particular appear to be affected by the presence of conspecifics, as well as the identity of the conspecifics and their relationship with the test subject, in many species of primates (reviewed in: Cronin, 2012; Yamamoto & Takimoto, 2012). In early studies, researchers typically dictated the social interactions of test subjects by deciding which animals to test in concert (e.g., Menzel Jr, Davenport & Rogers, 1972; Brosnan & de Waal, 2003; Horner et al., 2006). However, researchers are increasingly recognizing that testing primate cognition in the field or in less constrained social settings in captivity allows for subject-driven partner choice that provides a more valid representation of cognitive processes in several species (e.g., Whiten, Horner & de Waal, 2005; Noe, 2006; Crockford et al., 2012; Molesti & Majolo, 2016; Suchak et al., 2016). Maintaining the social environment that is characteristic of a species’ natural history as much as possible during cognitive testing improves the socio-ecological validity of the research. The increased validity should be especially pronounced for gregarious species and when social cognition is under investigation.

Even when non-social cognition is the focus of the research, removing primates from their familiar social setting may impact the validity of results via an increased stress response. Decreased stress is desirable not only to promote good animal welfare but also to assure validity of cognitive and behavioral research (Olsson & Westlund, 2007). There are likely cases in which subjects may experience less stress when isolated from conspecifics for cognitive testing. However, in general, for social species, separation from groupmates may induce negative physiological changes (e.g., Shively, Clarkson & Kaplan, 1989) whereas the presence of conspecifics may buffer individuals from psychological distress (e.g., Stanton, Patterson & Levine, 1985; Ragen et al., 2013). Separation-induced physiological changes may include the activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (e.g., Gonzales, Coe & Levine, 1982; Dettmer et al., 2012), which has well-established influences on learning and cognition (McEwen & Sapolsky, 1995; Newcomer et al., 1999; Lyons et al., 2000; Song et al., 2006). Some captive facilities have gone to great measures to acclimate primates to routine separation from groupmates for testing (e.g., Hare, Call & Tomasello, 2001; Hopper et al., 2014), yet success may vary by species, individual temperaments, and the experimental protocol (Hopper et al., 2013). Because of these potential impacts of individual testing, which may confound results of such testing, we believe it is important to look to previously-run studies that have successfully tested primate cognition in a social setting to inform future experimental design of primate cognitive research. While we acknowledge that both social and individual testing have advantages and disadvantages, we believe highlighting social approaches is a useful exercise given that the default protocol for many research studies is to test primates individually or in pairs.

Although testing primates in a group setting has the potential to increase validity and minimize stress, such methods are often not readily adopted because of the logistical challenges and statistical limitations of social testing (e.g., Gazes et al., 2013). For example, when primates are tested in a social group in the wild or captivity, it can be difficult to elicit participation from all group members due to competition within the social group, interference from other group members, the ability to scrounge without participating, and/or the tendency of low-ranking individuals to abstain from participating in the presence of higher ranking others (e.g., Santos et al., 2002; Hopper et al., 2007). Another challenge is the reduced experimental control that often comes with social testing. It is not always practical to control design aspects such as the number of trials per individual, order of participation, nor the social composition of subgroups present (e.g., Crockford et al., 2012; House et al., 2014). Furthermore, it can be difficult and laborious to identify individual responses, either in real time or from video (e.g., Drea, 2006; van Leeuwen et al., 2013). Finally, statistically speaking, testing entire social groups may essentially reduce a researcher’s sample size, as the subjects within a single group often cannot be considered independent from one another (e.g., Burkart et al., 2014; Cronin et al., 2014a). This limitation is exacerbated by the fact that groups will rarely be uniform in size, demographic makeup, nor in their physical environment.

Here, we provide an overview of cognitive studies that have taken place with primates in a social setting over a sixteen-year period, since the year 2000. We do so in order to understand the frequency with which such testing occurs, how it is distributed across taxa and environments, and the range of sample sizes (social groups and individuals) that researchers have studied. Another aim of this survey is to extract potential solutions to the practical and statistical challenges of social testing. Given that increased validity and improved welfare may be gained from testing social species in a social setting (e.g., Drea, 2006; Koski & Burkart, 2015), we hope that by providing this information scientists may be better equipped with promising approaches for future research design.

Survey Methodology

First, we used Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com/) to systematically identify peer-reviewed journal articles (see Table S1). Searches were performed in English separately for each year between 2000 and 2015, inclusive, using the search term “primate AND cognition AND experiment AND social group.” Searches were performed in one year increments by the authors, completed in February of 2016. The resulting list of articles was then screened for whether the methods described non-human primates that were tested in groups comprised of three or more individuals. Given the difficulty of defining “cognition,” for our purposes we considered any research that included an experimental intervention and measured behavioral responses. Therefore, we also filtered by whether the publication included any kind of experimental manipulation (e.g., presented a stimulus or a task); studies that were purely observational were not considered here. We included a continuum of social testing settings, from open access to an apparatus for an entire social group (e.g., van de Waal, Claidière & Whiten, 2015) to cases in which individuals or dyads from a larger social group were tested separately but were not physically separated from a larger social group (for example if they could enter and exit a test booth through a swinging door as they chose, e.g., Fagot & Paleressompoulle, 2009). We excluded cases in which primates were tested socially but with non-conspecifics, except for one case in which naturally occurring mixed-species groups were studied in the field (Kirchhof & Hammerschmidt, 2006). Next, we then returned to each journal that contributed a result to the first round of searching and performed two supplemental searches. The first used the terms “primate AND playback” (because we noted several playback studies were missed in the broad Google Scholar search) and a second search using the terms “primate AND experiment AND cognition” (because we noted that several field studies did not use the term “social group” when studying primates in a social setting). We also included input from two external colleagues (EJC van Leeuwen & E van de Waal) and three reviewers of an earlier draft of this manuscript.

For each publication satisfying the above criteria, we extracted the following information and entered it into a database: institution name(s), test environment (field, zoo, laboratory, or sanctuary), species, number of social groups studied, number of individuals tested, keywords, and the full citation. Additionally, we noted for each publication whether the target information was reported in the manuscript (or supplemental information) exactly, as a range, or whether the information was unreported. For example, while some articles reported the exact number of individuals in the groups tested, others only reported the range of group sizes. To determine the median number of social groups and individuals studied per publication, we first filtered our results to include only those publications that reported this information (or a range across multiple groups, in which case the average was taken). Initially, we attempted to document the statistical approaches employed in each study but found we were unable to do so in a consistent way given the number of approaches used per study and variability in statistical reporting. The final database was not adjusted in any way to standardize the number of publications from a single author or site, but a bias toward overrepresentation from certain animals or institutions is considered in the Discussion. The database does not include information about studies that were attempted in a group setting but failed to be completed.

Disagreements or uncertainties about inclusion were decided on by all authors based on the contents of the publication and our criteria (publication authors were never contacted for clarification or additional information). Data were analyzed in R version 3.1.2 (R Core Team, 2014) and visualized using “ggplot2” (Wickham, 2009).

Results

The search yielded 248 peer-reviewed publications in 43 journals (Table S1). The number of publications that measured primate cognition in a social setting increased significantly over the years examined (Spearman Rank Order correlation r = 0.80, S = 134.4, P < 0.001).

Test environment

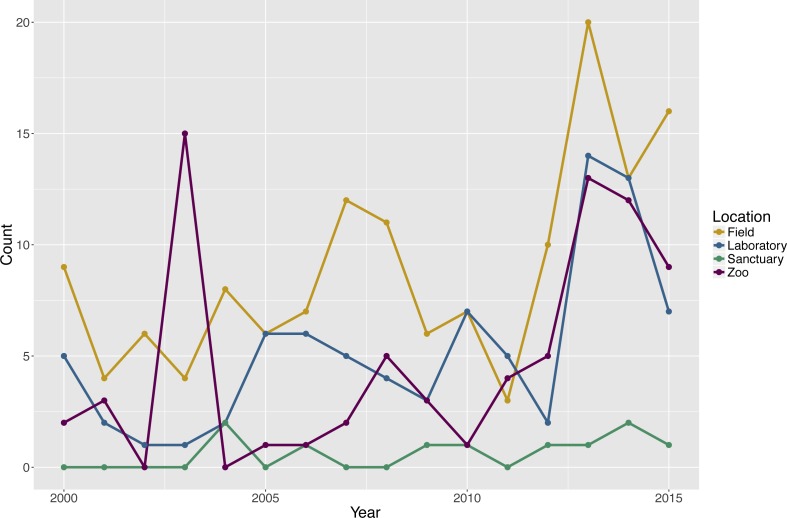

The search revealed that 142 publications (57.3%) tested subjects in a field setting, 84 publications (33.9%) tested subjects in a laboratory setting, 76 publications (30.6%) tested subjects in a zoo setting, and 10 publications (4.0%) tested subjects in a sanctuary setting. Two publications did not report the setting for the testing of six groups. Note that the percentages sum to greater than 100% because some publications tested social groups in more than one type of environment and each unique species and environment combination within a publication was considered separately in the analyses (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Count of publications testing primate cognition in a social setting, by environment and year of publication, with one entry per unique combination of environment type and species per publication.

Range of species tested

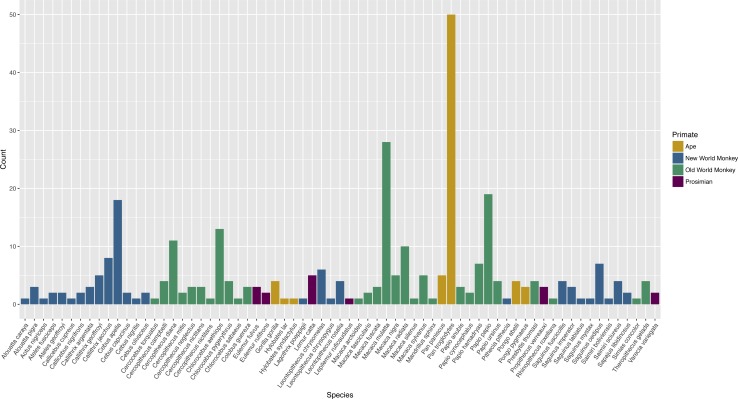

The publications encompassed 71 different species (Table S1). Apes were tested in 25.4% of publications, Old World monkeys in 55.6% of publications, New World monkeys in 29.8%, and prosimians in 6.0% of publications. Twenty-six publications (10.5%) included subjects of more than one species. Chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) were the most commonly tested species, represented in 18.5% of publications (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Count of publications testing primate cognition in a social setting, by species, with one entry per unique combination of environment type and species per publication.

Number of subjects and social groups tested

Two hundred and twenty-one of the 248 publications (89.1%) provided information regarding the number of subjects tested. The median number of subjects tested per publication was 17 (range 1–335). Two hundred and eighteen of the publications (87.9%) provided information regarding the number of social groups tested. The median number of social groups tested per publication was 2 (range 1–55).

Identification of promising approaches

We reviewed the literature for methodological approaches to overcoming four challenges common to social testing: reduced participation, reduced experimental control, difficulty identifying individual responses, and reduced sample size. All publications listed in Table S1 have overcome social testing challenges in some way, and may provide researchers with ideas for overcoming challenges specific to their own test environment or study species. However, to meet our aim of extracting potential solutions from the literature review that overcome these common practical and statistical challenges, we selected publications that we envisage will be useful to a broad audience. These publications are discussed in detail below.

Discussion

Conducting cognitive experiments in a social group comes with several potential benefits, including testing animals in a context that reflects their natural history and improved animal welfare. However, the challenges posed, including reduced participation due to competition or aggression in the group, reduced experimental control, reduced effective sample size, and difficulty identifying individual responses, may lead researchers to be wary of engaging in social testing. In this review encompassing articles published since the year 2000, we found that the number of publications that have tested primate cognition in a social setting has steadily increased and the coverage of species, while not evenly distributed, has been broad. Furthermore, such experimental studies have taken place in a range of captive environments and in the field. These findings suggest that there are feasible approaches to studying cognition in a social setting that we can turn to to extract strategies to overcoming real and perceived research challenges with social testing.

Strategies for overcoming the challenge of reduced participation

A key challenge to testing primate cognition in a social setting is reduced participation due to competition or interference by group members, especially for lower-ranking individuals. Testing primates individually ensures that all subjects have equal exposure to the test stimuli and that their responses are uninfluenced by the actions or choices of others (Hopper et al., 2014). Hoewever, individual testing still does not guarantee that all subjects will participate, nor that their data are valid (Hopper et al., 2013). Therefore, we highlight four strategies that have been employed by researchers testing primates in a social setting to combat this. The first is to provide several test apparatuses so that access to them cannot be easily monopolized. For example, in a test of social learning in wild vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops), van de Waal and colleagues (2015) distributed between four and eight identical, baited puzzle boxes within the monkeys’ home range that allowed 40% of the individuals in the three wild groups under investigation to interact with the puzzle boxes (Fig. 3). The second strategy, which has been used with free-ranging rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) by Santos and colleagues, is to create a mobile task that experimenters can present to individuals or subgroups of interest as the opportunity arises (e.g., Santos, Hauser & Spelke, 2001; Hughes & Santos, 2012 Fig. 4; see also Almeling et al., 2016). The third strategy, designed to increase animals’ access to a single apparatus at a fixed location, is to run extended test sessions to allow lower-ranking individuals access to the test apparatus after more dominant group members become satiated. For example, Hopper et al. (2007) presented a tool-use task to captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) in 5-hour long sessions, obtaining data from 79% of the chimpanzees in two captive groups. Our fourth suggestion comes from a new cognitive testing paradigm used with a group of zoo-housed Japanese macaques (M. fuscata), where the whole social group has access to touchscreens in two test booths at the periphery of their habitat when a researcher is present (Cronin, Hopper & Ross, 2015). The macaques were trained to recognize an ‘end-of-session’ cue that indicates they will not receive any additional rewards for the day, causing them to leave the testing booth and allowing untested individuals to participate. This has proven an effective way to obtain touchscreen trials from lower ranking individuals who participate once the higher-ranking ones have disengaged after receiving their end-of-session cue.

Figure 3. Vervet monkey accessing one of several available apparatuses at Inkawu Vervet Project, South Africa.

Photo credit: Erica van de Waal.

Figure 4. A portable experimental setup for testing rhesus macaque cognition at the Cayo Santiago Field Station, Puerto Rico.

Photo credit: Alyssa Arre.

Strategies for overcoming the challenge of reduced experimental control

A second challenge to testing primates in a social setting is reduced experimental control. Specifically, in a social setting it is not often practical to control experimental design aspects such as the number of trials per individual, order of participation, nor the social composition of subgroups present (Carter et al., 2014), as can be acheieved with experimenter-controlled pairings (e.g., Silk et al., 2005; Cronin et al., 2014b). One strategy for overcoming an unbalanced number of trials per subject is to set up the experiment and analysis such that proportions of response types (rather than frequencies) can be informative of the subject’s knowledge or preference. For example, House and colleagues (2014) tested prosocial behavior in several groups of captive chimpanzees without isolating subjects. They designed an apparatus that subjects could control at the perimeter of their enclosure and compared changes in the proportion of food-sharing attempts made by individuals when different food distributions were possible. By employing a within-subjects design, it was not necessary to obtain the same number of trials across all individuals or conditions (see also Finestone et al., 2014; Molesti & Majolo, 2016). Other dynamic aspects of the testing environment, such as the order of exposure, amount of previous experience with the task, or the current social composition, can now be handled statistically through the use of generalized mixed effects models when sample sizes are sufficient (see Crockford et al., 2012; House et al., 2014). Those studying social relationships or social learning may actively wish to test within-group dynamics using social network analyses (Whitehead, 2008), network-based diffusion analysis (Franz & Nunn, 2009; Franz & Nunn, 2010) or option-bias analysis (Kendal et al., 2010; Kendal et al., 2015). Mixed effects models are useful for handling datasets in which the same individuals are tested in different social configurations, and they can also handle non-factorial designs that may be prevalent in experiments that rely on opportunistic data collection in a captive or wild setting.

Strategies for overcoming the challenge of identifying individual responses

A third challenge to testing primate cognition in a social setting is the difficulty of identifying individual responses. If an animal is housed alone or removed from its social group for testing, researchers are relieved of the responsibility to track which individual is making a response (e.g., Basile & Hampton, 2017; Cantlon et al., 2015). Typically, when testing primates in a social setting, researchers video record experimental test sessions so that they can later code the individuals involved in a given trial (e.g., van Leeuwen et al., 2013). Although a commonly-used and successful method, video recording and later coding experiments is a time-consuming process that is made more complex with small-bodied and fast-moving primates, or when testing animals in the field where viewing animals may be more difficult (e.g., Gunhold, Whiten & Bugnyar, 2014). More recently, creative testing arenas in captive settings have enabled researchers to identify individual subjects without removing the animal from its home enclosure. Researchers in zoos and laboratories have designed touchscreen test stations within, or attached to the periphery of, primates’ home enclosures, that allow animals to participate individually, while not being socially isolated from their group (Fagot & Paleressompoulle, 2009; Whitehouse et al., 2013; Cronin, Hopper & Ross, 2015). Live-stream footage or video recording can track which individuals are in the booth at any time, or, if resources allow, radio frequency identification (RFID) chips can be used to automatically track the identity of participating individuals and even queue up individually tailored task sets (Fagot & Paleressompoulle, 2009; Gazes et al., 2013; Claidière et al., 2014; Fig. 5). The Primate Research Institute at Kyoto University utilizes an automated face recognition program that allows them to identify the chimpanzee when he or she voluntarily breaks off from the social group to engage in touchscreen research. A system such as this also allows for automated coding of the participant’s identity and personalized administration of tasks.

Figure 5. Guinea baboons with RFID chips to automate individual identification of responses in touchscreen booths at the CNRS Primate Center in Rousset-sur-Arc, France.

Inset shows a baboon inside one of the touchscreen booths. Photo credit: Nicolas Claidière.

Strategies for overcoming the challenge of reduced sample size

A fourth challenge to testing in a social setting to address is the reduction in sample size. Given that individuals within a group are not independent from one another, the conservative statistical approach often used is to consider sample size as equivalent to social group. Obviously this is a limitation of statistical power and may turn researchers away from testing primates socially. However, as mentioned above, statistical mixed effects models can help with issues of interdependence through the inclusion of individuals and groups as random factors (Schneider, Melis & Tomasello, 2012; Gunhold, Whiten & Bugnyar, 2014). Furthermore, many research groups have included several social groups in a single publication, and we encourage others to follow their lead when feasible (e.g., Whiten et al., 2007; Burkart et al., 2014). It is common for those running experimental studies with wild primates to only work with individuals from one or two groups (median number of social groups in this analysis was two), yet several field sites have now been established that include multiple social groups (e.g., Cayo Santiago, Puerto Rico, Santos, Hauser & Spelke, 2001; Inkawu Vervet Project, South Africa, van de Waal, Borgeaud & Whiten, 2013). One way forward may be to seek out research at locations that are home to several social groups of the same species (e.g., as is typical of primate sanctuaries or National Primate Research Centers). Lastly, although numbers may be small at a single institution, research in zoos where collaboration between institutions is often already in the culture may be a feasible route to obtaining data from several groups and species (e.g., Dean et al., 2011; Cronin, 2017). Researchers would need to consider variation introduced from multiple sites, but would likely increase their statistical power and the generalizability of their findings.

Conclusions

In addition to illuminating strategies for overcoming challenges of group testing, this literature review revealed a number of interesting trends from sixteen years of research. First, the knowledge of primate cognition gained from testing primates in a social setting is not evenly distributed across species, with nearly a fifth of publications focusing on chimpanzees. A disproportionate emphasis on a small number of species has been noted previously as a criticism of comparative psychological research (e.g., Beach, 1950; Beran et al., 2014) and remains a pervasive issue for primate cognition research. It is likely that an over-emphasis on chimpanzees has influenced the inferences drawn about the unique nature of human cognition and the evolution of cognition more generally (e.g., Melis & Warneken, 2016). At a broader taxonomic level, prosimians were the least represented (approximately one in twenty publications included prosimians). This may reflect an under-representation of prosimians in cognitive research (Melfi, 2005), however studies of species naturally found living solitary or in pairs, as is the case for orangutans, night monkeys, and several prosimian species, would not have been included here, as discussed below.

There were several practical decisions that limited the scope of this review. The first is that we restricted the search to research with non-human primates. However, we hope some lessons learned here may apply to other social species as well. In fact, recent work has called to light the limited validity of testing human cognition in non-social paradigms as well (e.g., Reader & Holmes, 2016). The selection criteria included studies that took place in social groups of three or more, primarily to avoid studies using the common approach of testing dyads extracted from a larger group (e.g., Melis, Hare & Tomasello, 2006; Cronin et al., 2014b; Brosnan et al., 2015), as this approach misses the spirit of what we were trying to evaluate. Admittedly, this leaves species naturally living alone or in pairs to be excluded from our dataset, which may affect our conclusions above about the relative contribution of species to studies of cognition in a social setting. We also opted to include only studies in which there was some experimental manipulation or presentation of a task in order to have objective criteria for what was included as experimental, “cognitive research.” This ignores several interesting findings from observational research relevant to primate cognition, such as vocal learning and cultural transmission of naturally-occurring behaviors (e.g., Luncz, Mundry & Boesch, 2012; van Leeuwen, Cronin & Haun, 2014). With the focus on experimental, cognitive research, we also did not tackle other realms of primate research, such as biomedical research, an area that may also be growing in its desire to test socially-housed primates for the same reasons of increased validity and improved welfare (e.g., Kelly, 2008; DiVincenti & Wyatt, 2011). Unfortunately, due to practical limitations, this review also excludes research that was not published in English.

It is also worth noting that this review did not provide a direct comparison of individual versus group testing; our aim was to highlight practical take-aways from previously-published work to facilitate future cognitive testing of primates in a social setting. Indeed, such a comparative evaluation would be difficult. There are very few examples in which primates have been tested with the same apparatus in a social as well as an individual setting to test the effect of social environment on cognition (although see Hopper et al., 2015b, and also Krasheninnikova & Schneider, 2014 for an example with birds, Amazona amazonica). Typically, if an experiment tests both individuals and groups of primates with the same task, the individually-tested subjects represent ‘control’ animals to be compared to socially-tested subjects, in studies of social learning for example (e.g., Whiten, Horner & de Waal, 2005; Kendal et al., 2015). However, the relative impact of the social environment on differences in learning are rarely considered.

The majority of publications describing tests of primates in social groups resulted from experiments that took place in the field and laboratories; these environments were nearly equally represented. Zoos and sanctuaries, on the other hand, contributed only a small fraction of the publications. Notably, representation of environments in our database is characterized by number of publications, not by number of institutions. Moving forward, zoos and sanctuaries may provide a valuable resource for conducting enriching, non-invasive, voluntary research with socially-housed primates (Cronin, 2017; Hopper, 2017), and this may be especially attractive to institutions if the research proves enriching to the subjects (Hopper, Shender & Ross, 2016). In the past sixteen years, there have been over two hundred publications describing cognitive research with primate subjects tested in the presence of at least two other conspecifics. These studies spanned several species and test environments. We also note that, although the majority of studies identified in our review, unsurprisingly, tested aspects of primate social cognition (e.g., social learning, cooperation, competition, and communication), this was not exclusively so. Highlighting that a social test setting does not prohibit the testing of non-social cognition, our review revealed tests of, for example, analogical reasoning (Fagot & Maugard, 2013), memory (Fagot & de Lillo, 2011; Maugard, Marzouki & Fagot, 2013), visual perception (Cheries et al., 2006), numerical understanding (Hauser, Carey & Hauser, 2000), and personality (Carter et al., 2012; Neumann et al., 2013), although we note the inherent complexity of teasing apart “social” from “non-social” cognition (c.f. Seyfarth & Cheney, 2017).

Many researchers are overcoming several of the hurdles inherent to social testing using creative paradigms, embracing collaboration, and employing advances in statistics and technology. Moving forward, we hope that researchers will consider the strategies we have highlighted as well as publications summarized in Table S1 as a resource for designing, conducting and analyzing cognitive research with primates in a social setting. Social testing will continue to present challenges; many of the strategies highlighted above require additional time, collaboration, and statistical expertise. However, continuing to focus efforts on facilatiting cognitive testing in a social setting should continue to strengthen the validity of conclusions drawn from studies of primate cognition and improve animal welfare.

Supplemental Information

The publications that reported tests of primate cognition in a social setting published between 2000 and 2015 (inclusive), sorted by species, with one entry per unique combination of environment type and species per publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edwin J.C. van Leeuwen and Erica van de Waal for providing feedback on the completeness of our database. We also thank three helpful reviewers (Jorg Massen, Agustin Fuentes and Vanessa Schmitt) for providing feedback on the completeness of our database and search strategies. We thank Steve Ross for providing valuable feedback on earlier versions of this manuscript.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by the Leo S. Guthman Fund. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Additional Information and Declarations

Competing Interests

Lydia M. Hopper is an Academic Editor for PeerJ.

Author Contributions

Katherine A. Cronin and Lydia M. Hopper conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Sarah L. Jacobson analyzed the data, wrote the paper, prepared figures and/or tables, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Kristin E. Bonnie conceived and designed the experiments, analyzed the data, wrote the paper, reviewed drafts of the paper.

Data Availability

The following information was supplied regarding data availability:

The raw data has been supplied as a Supplemental File.

References

- Almeling et al. (2016).Almeling L, Hammerschmidt K, Sennhenn-Reulen H, Freund AM, Fischer J. Motivational shifts in aging monkeys and the origins of social selectivity. Current Biology. 2016;26:1744–1749. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2016.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basile & Hampton (2017).Basile BM, Hampton RR. Dissociation of item and source memory in rhesus monkeys. Cognition. 2017;166:398–406. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beach (1950).Beach FA. The snark was a boojum. American Psychologist. 1950;5:115–124. doi: 10.1037/h0056510. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beran et al. (2014).Beran MJ, Parrish AE, Perdue BM, Washburn DA. Comparative cognition: past, present, and future. International Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2014;27:3–30. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan & de Waal (2003).Brosnan SF, de Waal FBM. Monkeys reject unequal pay. Nature. 2003;425:297–299. doi: 10.1038/nature01963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brosnan et al. (2015).Brosnan SF, Hopper LM, Richey S, Freeman HD, Talbot CF, Gosling SD, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ. Personality influences responses to inequity and contrast in chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour. 2015;101:75–87. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart et al. (2014).Burkart JM, Allon O, Amici F, Fichtel C, Finkenwirth C, Heschl A, Huber J, Isler K, Kosonen ZK, Martins E, Meulman EJ, Richiger R, Rueth K, Spillmann B, Wiesendanger S, van Schaik CP. The evolutionary origin of human hyper-cooperation. Nature Communications. 2014;5:4747. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cantlon et al. (2015).Cantlon JF, Piantadosi ST, Ferrigno S, Hughes KD, Barnard AM. The origins of counting. Psychological Science. 2015;26:853–865. doi: 10.1177/0956797615572907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter et al. (2012).Carter AJ, Marshall HH, Heinsohn R, Cowlishaw G. How not to measure boldness: novel object and antipredator responses are not the same in wild baboons. Animal Behaviour. 2012;84:603–609. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.06.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carter et al. (2014).Carter AJ, Marshall HH, Heinsohn R, Cowlishaw G. Personality predicts the propensity for social learning in a wild primate. PeerJ. 2014;2:e283. doi: 10.7717/peerj.283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheries et al. (2006).Cheries EW, Newman GE, Santos LR, Scholl BJ. Units of visual individuation in rhesus macaques: objects or unbound features? Perception. 2006;35:1057–1071. doi: 10.1068/p5551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claidière et al. (2014).Claidière N, Smith K, Kirby S, Fagot J. Cultural evolution of systematically structured behaviour in a non-human primate. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2014;281:20141541. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2014.1541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford et al. (2012).Crockford C, Wittig R, Mundry R, Zuberbuhler K. Wild chimpanzees inform ignorant group members of danger. Current Biology. 2012;22:142–146. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.11.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin (2012).Cronin KA. Prosocial behaviour in animals: the influence of social relationships, communication and rewards. Animal Behaviour. 2012;84:1085–1093. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.08.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin (2017).Cronin KA. APA handbook of comparative psychology. American Psychological Association; Washington, D.C.: 2017. Comparative studies of cooperation: collaboration and prosocial behavior in animals. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin & Hopper (2017).Cronin KA, Hopper LM. A comparative perspective on helping and fairness. In: Sommerville JA, Decety J, editors. Social cognition: development across the life span. Taylor and Francis; New York: 2017. pp. 26–45. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, Hopper & Ross (2015).Cronin KA, Hopper LM, Ross SR. Snow monkeys settle in: the design of a new zoo-based research program for Japanese macaques (Macaca fuscata) American Journal of Primatology. 2015;77:64–65. [Google Scholar]

- Cronin et al. (2014b).Cronin KA, Pieper BA, van Leeuwen EJC, Mundry R, Haun DB. Problem solving in the presence of others: how rank and relationship quality impact resource acquisition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) PLOS ONE. 2014b;9:e93204. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0093204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin et al. (2014a).Cronin KA, van Leeuwen EJC, Vreeman V, Haun DBM. Population-level variability in the social climates of four chimpanzee societies. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2014a;35:389–396. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.05.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean et al. (2011).Dean LG, Hoppitt W, Laland KN, Kendal RL. Sex ratio affects sex-specific innovation and learning in captive ruffed lemurs (Varecia variegata and Varecia rubra) American Journal of Primatology. 2011;73:1210–1221. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dettmer et al. (2012).Dettmer AM, Novak MA, Suomi SJ, Meyer JS. Physiological and behavioral adaptation to relocation stress in differentially reared rhesus monkeys: hair cortisol as a biomarker for anxiety-related responses. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2012;37:191–199. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiVincenti & Wyatt (2011).DiVincenti J, Wyatt JD. Pair housing of macaques in research facilities: a science-based review of benefits and risks. Journal of the American Association for Laboratory Animal Science. 2011;50:856–863. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drea (2006).Drea CM. Studying primate learning in group contexts: tests of social foraging, response to novelty, and cooperative problem solving. Methods. 2006;38:162–177. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2005.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot & de Lillo (2011).Fagot J, de Lillo C. A comparative study of working memory: immediate serial spatial recall in baboons (Papio papio) and humans. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49:3870–3880. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot & Maugard (2013).Fagot J, Maugard A. Analogical reasoning in baboons (Papio papio): flexible reencoding of the source relation depending on the target relation. Learning & Behavior. 2013;41:229–237. doi: 10.3758/s13420-012-0101-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot & Paleressompoulle (2009).Fagot J, Paleressompoulle D. Automatic testing of cognitive performance in baboons maintained in social groups. Behavior Research Methods. 2009;41:396–404. doi: 10.3758/BRM.41.2.396. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finestone et al. (2014).Finestone E, Bonnie KE, Hopper LM, Vreeman VM, Lonsdorf EV, Ross SR. The interplay between individual, social, and environmental influences on chimpanzee food choices. Behavioural Processes. 2014;105:71–78. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz & Nunn (2009).Franz M, Nunn CL. Network-based diffusion analysis: a new method for detecting social learning. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2009;276:1829–1836. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2008.1824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Franz & Nunn (2010).Franz M, Nunn CL. Investigating the impact of observation errors on the statistical performance of network-based diffusion analysis. Learning and Behavior. 2010;38:235–242. doi: 10.3758/LB.38.3.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazes et al. (2013).Gazes RP, Brown EK, Basile BM, Hampton RR. Automated cognitive testing of monkeys in social groups yields results comparable to individual laboratory-based testing. Animal Cognition. 2013;16:445–458. doi: 10.1007/s10071-012-0585-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, Coe & Levine (1982).Gonzales CA, Coe CL, Levine S. Cortisol responses under different housing conditions in female squirrel monkeys. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1982;7:209–216. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(82)90014-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunhold, Whiten & Bugnyar (2014).Gunhold T, Whiten A, Bugnyar T. Video demonstrations seed alternative problem-solving techniques in wild common marmosets. Biology Letters. 2014;10:20140439. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2014.0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare, Call & Tomasello (2001).Hare B, Call J, Tomasello M. Do chimpanzees know what conspecifics know? Animal Behaviour. 2001;61:139–151. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2000.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow (1949).Harlow HF. The formation of learning sets. Psychological Review. 1949;56:51–65. doi: 10.1037/h0062474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hauser, Carey & Hauser (2000).Hauser MD, Carey S, Hauser LB. Spontaneous number representation in semi–free–ranging rhesus monkeys. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2000;267:829–833. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper (2017).Hopper LM. Cognitive research in zoos. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences. 2017;16:100–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2017.04.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper et al. (2013).Hopper LM, Holmes AN, Williams LE, Brosnan SF. Dissecting the mechanisms of squirrel monkey (Saimiri boliviensis) social learning. PeerJ. 2013;1:e13. doi: 10.7717/peerj.13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper et al. (2015b).Hopper LM, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Whiten A. The importance of witnessed agency in chimpanzee social learning of tool use. Behavioral Processes. 2015b;112:120–129. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2014.10.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper et al. (2014).Hopper LM, Price SA, Freeman HD, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Kendal RL. Influence of personality, age, sex, and estrous state on chimpanzee problem-solving success. Animal Cognition. 2014;17:835–847. doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0715-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper, Shender & Ross (2016).Hopper LM, Shender MA, Ross SR. Behavioral research as physical enrichment for captive chimpanzees. Zoo Biology. 2016;35:293–297. doi: 10.1002/zoo.21297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopper et al. (2007).Hopper LM, Spiteri A, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Horner V, Whiten A. Experimental studies of traditions and underlying transmission processes in chimpanzees. Animal Behaviour. 2007;73:1021–1032. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.07.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Horner et al. (2006).Horner V, Whiten A, Flynn E, de Waal FBM. Faithful replication of foraging techniques along cultural transmission chains by chimpanzees and children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:13878–13883. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606015103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- House et al. (2014).House BR, Silk JB, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ. Task design influences prosociality in captive chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) PLOS ONE. 2014;9:e103422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0103422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes & Santos (2012).Hughes KD, Santos LR. Rotational displacement skills in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2012;126:421–432. doi: 10.1037/a0028757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly (2008).Kelly J. Implementation of permanent group housing for cynomolgus macaques on a large scale for regulatory toxicology studies. Japanese Society for Alternative Animal Experiments. 2008;14:S107–S110. [Google Scholar]

- Kendal et al. (2010).Kendal RL, Custance DM, Kendal JR, Vale G, Stoinski TS, Rakotomalala NL, Rasamimanana H. Evidence for social learning in wild lemurs (Lemur catta) Learning & Behavior. 2010;38:220–234. doi: 10.3758/LB.38.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendal et al. (2015).Kendal R, Hopper LM, Whiten A, Brosnan SF, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, Hoppit W. Chimpanzees copy dominant and knowledgeable individuals: implications for cultural diversity. Evolution and Human Behavior. 2015;36(1):65–72. doi: 10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2014.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirchhof & Hammerschmidt (2006).Kirchhof J, Hammerschmidt K. Functionally referential alarm calls in tamarins (Saguinus fuscicollis and Saguinus mystax)—evidence from playback experiments. Ethology. 2006;112:346–354. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2006.01165.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koski & Burkart (2015).Koski SE, Burkart JM. Common marmosets show social plasticity and group-level similarity in personality. Scientific Reports. 2015;5:8878. doi: 10.1038/srep08878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krasheninnikova & Schneider (2014).Krasheninnikova A, Schneider JM. Testing problem-solving capacities: differences between individual testing and social group testing. Animal Cognition. 2014;17:1227–1232. doi: 10.1007/s10071-014-0744-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luncz, Mundry & Boesch (2012).Luncz LV, Mundry R, Boesch C. Evidence for cultural differences between neighboring chimpanzee communities. Current Biology. 2012;22:922–926. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2012.03.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons et al. (2000).Lyons DM, Lopez JM, Yang C, Schatzberg AF. Stress-level cortisol treatment impairs inhibitory control of behavior in monkeys. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2000;20:7816–7821. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-20-07816.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maugard, Marzouki & Fagot (2013).Maugard A, Marzouki Y, Fagot J. Contribution of working memory processes to relational matching-to-sample performance in baboons (Papio papio) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2013;127:370–379. doi: 10.1037/a0032336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen & Sapolsky (1995).McEwen BS, Sapolsky RM. Stress and cognitive function. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 1995;5:205–216. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(95)80028-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melfi (2005).Melfi V. The appliance of science to zoo-housed primates. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2005;90:97–106. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2004.08.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melis, Hare & Tomasello (2006).Melis AP, Hare B, Tomasello M. Engineering cooperation in chimpanzees: tolerance constraints on cooperation. Animal Behaviour. 2006;72:275–286. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.09.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Melis & Warneken (2016).Melis AP, Warneken F. The psychology of cooperation: insights from chimpanzees and children. Evolutionary Anthropology: Issues, News, and Reviews. 2016;25:297–305. doi: 10.1002/evan.21507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menzel Jr, Davenport & Rogers (1972).Menzel Jr EW, Davenport RK, Rogers CM. Protocultural aspects of chimpanzees’ responsiveness to novel objects. Folia Primatologica. 1972;17:161–170. doi: 10.1159/000155425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molesti & Majolo (2016).Molesti S, Majolo B. Cooperation in wild Barbary macaques: factors affecting free partner choice. Animal Cognition. 2016;19:133–146. doi: 10.1007/s10071-015-0919-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann et al. (2013).Neumann C, Agil M, Widdig A, Engelhardt A. Personality of wild male crested macaques (Macaca nigra) PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e69383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newcomer et al. (1999).Newcomer JW, Selke G, Melson AK, Hershey T, Craft S, Richards K, Alderson AL. Decreased memory performance in healthy humans induced by stress-level cortisol treatment. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1999;56:527–533. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.56.6.527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noe (2006).Noe R. Cooperation experiments: coordination through communication versus acting apart together. Animal Behaviour. 2006;71:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.03.037. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Olsson & Westlund (2007).Olsson IAS, Westlund K. More than numbers matter: the effect of social factors on behaviour and welfare of laboratory rodents and non-human primates. Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 2007;103:229–254. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2006.05.022. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- R Core Team (2014).R Core Team . R Foundation for Statistical Computing; Vienna: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ragen et al. (2013).Ragen BJ, Maningerand N, Mendoza SP, Jarcho MR, Bales KL. Presence of a pair-mate regulates the behavioral and physiological effects of opioid manipulation in the monogamous titi monkey (Callicebus cupreus) Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2013;28:2448–2461. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2013.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reader & Holmes (2016).Reader AT, Holmes NP. Examining ecological validity in social interaction: problems of visual fidelity, gaze, and social potential. Culture and Brain. 2016;4:134–146. doi: 10.1007/s40167-016-0041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos, Hauser & Spelke (2001).Santos LR, Hauser MD, Spelke ES. Recognition and categorization of biologically significant objects by rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta): the domain of food. Cognition. 2001;82:127–155. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(01)00149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos et al. (2002).Santos LR, Sulkowski GM, Spaepen GM, Hauser MD. Object individuation using property/kind information in rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) Cognition. 2002;83:241–264. doi: 10.1016/S0010-0277(02)00006-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, Melis & Tomasello (2012).Schneider A-C, Melis AP, Tomasello M. How chimpanzees solve collective action problems. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2012;279:4946–4954. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2012.1948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seyfarth & Cheney (2017).Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. Social cognition in animals. In: Sommerville JA, Decety J, editors. Social cognition: development across the life span. Taylor and Francis; New York: 2017. pp. 46–68. [Google Scholar]

- Shively, Clarkson & Kaplan (1989).Shively CA, Clarkson TB, Kaplan JR. Social deprivation and coronary artery atherosclerosis in female cynomolgus monkeys. Atherosclerosis. 1989;77:69–76. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(89)90011-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silk et al. (2005).Silk JB, Brosnan SF, Vonk J, Henrich J, Povinelli DJ, Richardson AS, Lambeth SP, Mascaro J, Schapiro SJ. Chimpanzees are indifferent to the welfare of unrelated group members. Nature. 2005;437:1357–1359. doi: 10.1038/nature04243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song et al. (2006).Song L, Che W, Min-Wei W, Murakami Y, Matsumoto K. Impairment of the spatial learning and memory induced by learned helplessness and chronic mild stress. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2006;83:186–193. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stanton, Patterson & Levine (1985).Stanton ME, Patterson JM, Levine S. Social influences on conditioned cortisol secretion in the squirrel monkey. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1985;10:125–134. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(85)90050-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suchak et al. (2016).Suchak M, Eppley TM, Campbell MW, Feldman RA, Quarles LF, de Waal FBM. How chimpanzees cooperate in a competitive world. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2016;113:201611826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611826113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suomi & Leroy (1982).Suomi SJ, Leroy HA. In memoriam: Harry F. Harlow (1905–1981) American Journal of Primatology. 1982;2:319–342. doi: 10.1002/ajp.1350020402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waal, Borgeaud & Whiten (2013).van de Waal E, Borgeaud C, Whiten A. Potent social learning and conformity shape a wild primate’s foraging decisions. Science. 2013;340:483–485. doi: 10.1126/science.1232769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waal, Claidière & Whiten (2013).van de Waal E, Claidière N, Whiten A. Social learning and spread of alternative means of opening an artificial fruit in four groups of vervet monkeys. Animal Behaviour. 2013;85:71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2012.10.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van de Waal, Claidière & Whiten (2015).van de Waal E, Claidière N, Whiten A. Wild vervet monkeys copy alternative methods for opening an artificial fruit. Animal Cognition. 2015;18:617–627. doi: 10.1007/s10071-014-0830-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen, Cronin & Haun (2014).van Leeuwen EJC, Cronin KA, Haun DBM. A group-specific arbitrary tradition in chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) Animal Cognition. 2014;17:1421–1425. doi: 10.1007/s10071-014-0766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Leeuwen et al. (2013).van Leeuwen EJC, Cronin KA, Schuette S, Call J, Haun DBM. Chimpanzees flexibly adjust their behaviour in order to maximize payoffs, not to conform to majorities. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e80945. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0080945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitehead (2008).Whitehead H. Analyzing animal societies: quantitative methods for vertebrate social analysis. The University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Whitehouse et al. (2013).Whitehouse J, Micheletta J, Powell LE, Bordier C, Waller BM. The impact of cognitive testing on the welfare of group housed primates. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e78308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0078308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten, Horner & de Waal (2005).Whiten A, Horner V, de Waal FBM. Conformity to cultural norms of tool use in chimpanzees. Nature. 2005;437:737–740. doi: 10.1038/nature04047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiten et al. (2007).Whiten A, Spiteri A, Horner V, Bonnie KE, Lambeth SP, Schapiro SJ, de Waal FBM. Transmission of multiple traditions within and between chimpanzee groups. Current Biology. 2007;17:1038–1043. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham (2009).Wickham H. ggplot2: elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag; New York: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto & Takimoto (2012).Yamamoto S, Takimoto A. Empathy and fairness: psychological mechanisms for eliciting and maintaining prosociality and cooperation in primates. Social Justice Research. 2012;25:233–255. doi: 10.1007/s11211-012-0160-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Further reading

- Addessi & Visalberghi (2001).Addessi E, Visalberghi E. Social facilitation of eating novel food in tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella): input provided by group members and responses affected in the observer. Animal Cognition. 2001;4:297–303. doi: 10.1007/s100710100113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold, Pohlner & Zuberbühler (2008).Arnold K, Pohlner Y, Zuberbühler K. A forest monkey’s alarm call series to predator models. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2008;62:549–559. doi: 10.1007/s00265-007-0479-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold & Zuberbühler (2006).Arnold K, Zuberbühler K. The alarm-calling system of adult male putty-nosed monkeys, Cercopithecus nictitans martini. Animal Behaviour. 2006;72:643–653. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2005.11.017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold & Zuberbühler (2008).Arnold K, Zuberbühler K. Meaningful call combinations in a non-human primate. Current Biology. 2008;18:R202–R203. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.01.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold & Zuberbühler (2013).Arnold K, Zuberbühler K. Female putty-nosed monkeys use experimentally altered contextual information to disambiguate the cause of male alarm calls. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e65660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0065660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbet & Fagot (2011).Barbet I, Fagot J. Processing of contour closure by baboons (Papio papio) Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2011;37:407–419. doi: 10.1037/a0025365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bard et al. (2006).Bard KA, Todd BK, Bernier C, Love J, Leavens DA. Self-awareness in human and chimpanzee infants: what is measured and what is meant by the mark and mirror test? Infancy. 2006;9:191–219. doi: 10.1207/s15327078in0902_6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bardo, Pouydebat & Meunier (2015).Bardo A, Pouydebat E, Meunier H. Do bimanual coordination, tool use, and body posture contribute equally to hand preferences in bonobos? Journal of Human Evolution. 2015;82:159–169. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauman et al. (2006).Bauman MD, Toscano JE, Mason WA, Lavenex P, Amaral DG. The expression of social dominance following neonatal lesions of the amygdala or hippocampus in rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Behavioral Neuroscience. 2006;120:749–760. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.120.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman (2010).Bergman TJ. Experimental evidence for limited vocal recognition in a wild primate: implications for the social complexity hypothesis. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2010;277:3045–3053. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2010.0580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman & Kitchen (2009).Bergman TJ, Kitchen DM. Comparing responses to novel objects in wild baboons (Papio ursinus) and geladas (Theropithecus gelada) Animal Cognition. 2009;12:63–73. doi: 10.1007/s10071-008-0171-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bicca-Marques & Garber (2004).Bicca-Marques JC, Garber PA. Use of spatial, visual, and olfactory information during foraging in wild nocturnal and diurnal anthropoids: a field experiment comparing Aotus, Callicebus, and Saguinus. American Journal of Primatology. 2004;62:171–187. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie et al. (2007).Bonnie KE, Horner V, Whiten A, de Waal FBM. Spread of arbitrary conventions among chimpanzees: a controlled experiment. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2007;274:367–372. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnie et al. (2012).Bonnie KE, Milstein MS, Calcutt SE, Ross SR, Wagner KE, Lonsdorf EV. Flexibility and persistence of chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes) foraging behavior in a captive environment. American Journal of Primatology. 2012;74:661–668. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonté, Flemming & Fagot (2011).Bonté E, Flemming T, Fagot J. Executive control of perceptual features and abstract relations by baboons (Papio papio) Behavioural Brain Research. 2011;222:176–182. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2011.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boose, White & Meinelt (2013).Boose KJ, White FJ, Meinelt A. Sex differences in tool use acquisition in bonobos (Pan paniscus) American Journal of Primatology. 2013;75:917–926. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeaud et al. (2015).Borgeaud C, Alvino M, van Leeuwen K, Townsend SW, Bshary R. Age/sex differences in third-party rank relationship knowledge in wild vervet monkeys, Chlorocebus aethiops pygerythrus. Animal Behaviour. 2015;102:277–284. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2015.02.006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeaud & Bshary (2015).Borgeaud C, Bshary R. Wild vervet monkeys trade tolerance and specific coalitionary support for grooming in experimentally induced conflicts. Current Biology. 2015;25:3011–3016. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgeaud, van de Waal & Bshary (2013).Borgeaud C, van de Waal E, Bshary R. Third-party ranks knowledge in wild vervet monkeys (Chlorocebus aethiops pygerythrus) PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e58562. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0058562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braccini & Caine (2009).Braccini SN, Caine NG. Hand preference predicts reactions to novel foods and predators in marmosets (Callithrix geoffroyi) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2009;123:18–25. doi: 10.1037/a0013089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley & McClung (2015).Bradley CE, McClung MR. Vocal divergence and discrimination of long calls in tamarins: a comparison of allopatric populations of Saguinus fuscicollis nigrifrons and S. f. lagonotus. American Journal of Primatology. 2015;77:679–687. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Briseño Jaramillo, Estrada & Lemasson (2015).Briseño Jaramillo M, Estrada A, Lemasson A. Individual voice recognition and an auditory map of neighbours in free-ranging black howler monkeys (Alouatta pigra) Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2015;69:13–25. doi: 10.1007/s00265-014-1813-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bshary (2001).Bshary R. Diana monkeys, Cercopithecus diana, adjust their antipredator response behaviour to human hunting strategies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2001;50:251–256. doi: 10.1007/s002650100354. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burkart & van Schaik (2013).Burkart JM, van Schaik CP. Group service in macaques (Macaca fuscata), capuchins (Cebus apella) and marmosets (Callithrix jacchus): a comparative approach to identifying proactive prosocial motivations. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2013;127:212–225. doi: 10.1037/a0026392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burns-Cusato, Cusato & Glueck (2013).Burns-Cusato M, Cusato B, Glueck AC. Barbados green monkeys (Chlorocebus sabaeus) recognize ancestral alarm calls after 350 years of isolation. Behavioural Processes. 2013;100:197–199. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calcutt et al. (2014).Calcutt SE, Lonsdorf EV, Bonnie KE, Milstein MS, Ross SR. Captive chimpanzees share diminishing resources. Behaviour. 2014;151:1967–1982. doi: 10.1163/1568539X-00003225. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell & Snowdon (2009).Campbell MW, Snowdon CT. Can auditory playback condition predator mobbing in captive-reared Saguinus oedipus? International Journal of Primatology. 2009;30:93–102. doi: 10.1007/s10764-008-9331-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Candiotti, Zuberbühler & Lemasson (2013).Candiotti A, Zuberbühler K, Lemasson A. Voice discrimination in four primates. Behavioural Processes. 2013;99:67–72. doi: 10.1016/j.beproc.2013.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cäsar et al. (2013).Cäsar C, Zuberbühler K, Young RJ, Byrne RW. Titi monkey call sequences vary with predator location and type. Biology Letters. 2013;9:20130535. doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2013.0535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caselli et al. (2015).Caselli CB, Mennill DJ, Gestich CC, Setz EZF, Bicca-Marques JC. Playback responses of socially monogamous black-fronted titi monkeys to simulated solitary and paired intruders. American Journal of Primatology. 2015;77:1135–1142. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claidière et al. (2015).Claidière N, Gullstrand J, Latouche A, Fagot J. Using automated learning devices for monkeys (ALDM) to study social networks. Behavior Research Methods. 2015;49:1–11. doi: 10.3758/s13428-015-0686-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claidière et al. (2013).Claidière N, Messer EJ, Hoppitt W, Whiten A. Diffusion dynamics of socially learned foraging techniques in squirrel monkeys. Current Biology. 2013;23:1251–1255. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark & Smith (2013).Clark FE, Smith LJ. Effect of a cognitive challenge device containing food and non-food rewards on chimpanzee well-being. American Journal of Primatology. 2013;75:807–816. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clay & Zuberbühler (2011).Clay Z, Zuberbühler K. Bonobos extract meaning from call sequences. PLOS ONE. 2011;6:e18786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coss, McCowan & Ramakrishnan (2007).Coss RG, McCowan B, Ramakrishnan U. Threat-related acoustical differences in alarm calls by wild bonnet macaques (Macaca radiata) elicited by python and leopard models. Ethology. 2007;113:352–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0310.2007.01336.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coye et al. (2015).Coye C, Ouattara K, Zuberbühler K, Lemasson A. Suffixation influences receivers’ behaviour in non-human primates. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 2015;282:20150265. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.0265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crast, Hardy & Fragaszy (2010).Crast J, Hardy JM, Fragaszy D. Inducing traditions in captive capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Animal Behaviour. 2010;80:955–964. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.08.023. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford et al. (2007).Crockford C, Wittig RM, Seyfarth RM, Cheney DL. Baboons eavesdrop to deduce mating opportunities. Animal Behaviour. 2007;73:885–890. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.10.016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crockford, Wittig & Zuberbühler (2015).Crockford C, Wittig RM, Zuberbühler K. An intentional vocalization draws others’ attention: a playback experiment with wild chimpanzees. Animal Cognition. 2015;18:581–591. doi: 10.1007/s10071-014-0827-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cronin, de Groot & Stevens (2015).Cronin KA, de Groot E, Stevens JM. Bonobos show limited social tolerance in a group setting: a comparison with chimpanzees and a test of the relational model. Folia Primatologica. 2015;86:164–177. doi: 10.1159/000373886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- da Cunha & Byrne (2006).da Cunha RGT, Byrne RW. Roars of black howler monkeys (Alouatta caraya): evidence for a function in inter-group spacing. Behaviour. 2006;143:1169–1199. doi: 10.1163/156853906778691568. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Day et al. (2003).Day RL, Coe RL, Kendal JR, Laland KN. Neophilia, innovation and social learning: a study of intergeneric differences in callitrichid monkeys. Animal Behaviour. 2003;65:559–571. doi: 10.1006/anbe.2003.2074. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de A Moura, Nunes & Langguth (2010).de A Moura AC, Nunes HG, Langguth A. Food sharing in lion tamarins (Leontopithecus chrysomelas): does foraging difficulty affect investment in young by breeders and helpers? International Journal of Primatology. 2010;31:848–862. doi: 10.1007/s10764-010-9432-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dean et al. (2012).Dean LG, Kendal RL, Schapiro SJ, Thierry B, Laland KN. Identification of the social and cognitive processes underlying human cumulative culture. Science. 2012;335:1114–1118. doi: 10.1126/science.1213969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Bitetti (2003).Di Bitetti MS. Food-associated calls of tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella nigritus) are functionally referential signals. Behaviour. 2003;140:565–592. doi: 10.1163/156853903322149441. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dindo, Whiten & de Waal (2009).Dindo M, Whiten A, de Waal FBM. In-group conformity sustains different foraging traditions in capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) PLOS ONE. 2009;4:e7858. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois et al. (2001).Dubois M, Gerard J-F, Sampaio E, de Faria Galvão O, Guilhem C. Spatial facilitation in a probing task in wedge-capped capuchins (Cebus Olivaceus) International Journal of Primatology. 2001;22:993–1006. doi: 10.1023/A:1012065605329. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubois et al. (2000).Dubois M, Sampaio E, Gerard JF, Quenette PY, Muniz J. Location-specific responsiveness to environmental perturbations in wedge-capped capuchins (Cebus olivaceus) International Journal of Primatology. 2000;21:85–102. doi: 10.1023/A:1005475613697. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dubuc et al. (2012).Dubuc C, Hughes KD, Cascio J, Santos LR. Social tolerance in a despotic primate: co-feeding between consortship partners in rhesus macaques. American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 2012;148:73–80. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans & Westergaard (2006).Evans TA, Westergaard GC. Self-control and tool use in tufted capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2006;120:163–166. doi: 10.1037/0735-7036.120.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot & Bonté (2010).Fagot J, Bonté E. Automated testing of cognitive performance in monkeys: use of a battery of computerized test systems by a troop of semi-free-ranging baboons (Papio papio) Behavior Research Methods. 2010;42:507–516. doi: 10.3758/BRM.42.2.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot, Bonté & Hopkins (2013).Fagot J, Bonté E, Hopkins WD. Age-dependent behavioral strategies in a visual search task in baboons (Papio papio) and their relation to inhibitory control. Journal of Comparative Psychology. 2013;127:194–201. doi: 10.1037/a0026385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot et al. (2014).Fagot J, Gullstrand J, Kemp C, Defilles C, Mekaouche M. Effects of freely accessible computerized test systems on the spontaneous behaviors and stress level of Guinea baboons (Papio papio) American Journal of Primatology. 2014;76:56–64. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagot & Parron (2010).Fagot J, Parron C. Relational matching in baboons (Papio papio) with reduced grouping requirements. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Animal Behavior Processes. 2010;36:184–193. doi: 10.1037/a0017169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtel (2004).Fichtel C. Reciprocal recognition of sifaka (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi) and redfronted lemur (Eulemur fulvus rufus) alarm calls. Animal Cognition. 2004;7:45–52. doi: 10.1007/s10071-003-0180-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtel (2007).Fichtel C. Avoiding predators at night: antipredator strategies in red-tailed sportive lemurs (Lepilemur ruficaudatus) American Journal of Primatology. 2007;69:611–624. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtel (2008).Fichtel C. Ontogeny of conspecific and heterospecific alarm call recognition in wild Verreaux’s sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi verreauxi) American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:127–135. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtel & Hammerschmidt (2002).Fichtel C, Hammerschmidt K. Responses of redfronted lemurs to experimentally modified alarm calls: evidence for urgency-based changes in call structure. Ethology. 2002;108:763–778. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2002.00816.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fichtel & Kappeler (2002).Fichtel C, Kappeler PM. Anti-predator behavior of group-living Malagasy primates: mixed evidence for a referential alarm call system. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2002;51:262–275. doi: 10.1007/s00265-001-0436-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer, Cheney & Seyfarth (2000).Fischer J, Cheney DL, Seyfarth RM. Development of infant baboons’ responses to graded bark variants. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences. 2000;267:2317–2321. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer & Hammerschmidt (2001).Fischer J, Hammerschmidt K. Functional referents and acoustic similarity revisited: the case of Barbary macaque alarm calls. Animal Cognition. 2001;4:29–35. doi: 10.1007/s100710100093. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, Rattermann & Thompson (2006).Flemming TM, Rattermann MJ, Thompson RK. Differential individual access to and use of reaching tools in social groups of capuchin monkeys (Cebus apella) and human infants (Homo sapiens) Aquatic Mammals. 2006;32:491–499. doi: 10.1578/AM.32.4.2006.491. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming, Thompson & Fagot (2013).Flemming TM, Thompson RK, Fagot J. Baboons, like humans, solve analogy by categorical abstraction of relations. Animal Cognition. 2013;16:519–524. doi: 10.1007/s10071-013-0596-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flombaum et al. (2004).Flombaum JI, Kundey SM, Santos LR, Scholl BJ. Dynamic object individuation in rhesus macaques a study of the tunnel effect. Psychological Science. 2004;15:795–800. doi: 10.1111/j.0956-7976.2004.00758.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flombaum & Santos (2005).Flombaum JI, Santos LR. Rhesus monkeys attribute perceptions to others. Current Biology. 2005;15:447–452. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.12.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forss et al. (2015).Forss SIF, Schuppli C, Haiden D, Zweifel N, van Schaik CP. Contrasting responses to novelty by wild and captive orangutans. American Journal of Primatology. 2015;77:1109–1121. doi: 10.1002/ajp.22445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fragaszy et al. (2013).Fragaszy DM, Liu Q, Wright BW, Allen A, Brown CW, Visalberghi E. Wild bearded capuchin monkeys (Sapajus libidinosus) strategically place nuts in a stable position during nut-cracking. PLOS ONE. 2013;8:e56182. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fruteau, van Damme & Noë (2013).Fruteau C, van Damme E, Noë R. Vervet monkeys solve a multiplayer “forbidden circle game” by queuing to learn restraint. Current Biology. 2013;23:665–670. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2013.02.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu et al. (2013).Fu W, Zhao D, Qi X, Guo S, Wei W, Li B. Free-ranging Sichuan snub-nosed monkeys, Rhinopithecus roxellana: neophobia, neophilia, or both. Current Zoology. 2013;59:311–316. doi: 10.1093/czoolo/59.3.311. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fugate, Gouzoules & Nygaard (2008).Fugate JMB, Gouzoules H, Nygaard LC. Recognition of rhesus macaque (Macaca mulatta) noisy screams: evidence from conspecifics and human listeners. American Journal of Primatology. 2008;70:594–604. doi: 10.1002/ajp.20533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes & Bicca-Marques (2012).Gomes DF, Bicca-Marques JC. Capuchin monkeys (Cebus nigritus) use spatial and visual information during within-patch foraging. American Journal of Primatology. 2012;74:58–67. doi: 10.1002/ajp.21009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goujon & Fagot (2013).Goujon A, Fagot J. Learning of spatial statistics in nonhuman primates: contextual cueing in baboons (Papio papio) Behavioural Brain Research. 2013;247:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunhold et al. (2014).Gunhold T, Massen JJ, Schiel N, Souto A, Bugnyar T. Memory, transmission and persistence of alternative foraging techniques in wild common marmosets. Animal Behaviour. 2014;91:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gustison et al. (2012).Gustison ML, MacLarnon A, Wiper S, Semple S. An experimental study of behavioural coping strategies in free-ranging female Barbary macaques (Macaca sylvanus) Stress. 2012;15:608–617. doi: 10.3109/10253890.2012.668589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gygax (2000).Gygax L. Hiding behaviour of long-tailed macaques (Macaca fascicularis): II. use of hiding places during aggressive interactions. Ethology. 2000;106:441–451. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0310.2000.00549.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]