Abstract

Purpose of the review

There is ample and growing evidence that obesity increases the risk of asthma and morbidity from asthma. Here we review recent clinical evidence supporting a causal link between obesity and asthma, and the mechanisms that may lead to “obese asthma”.

Recent findings

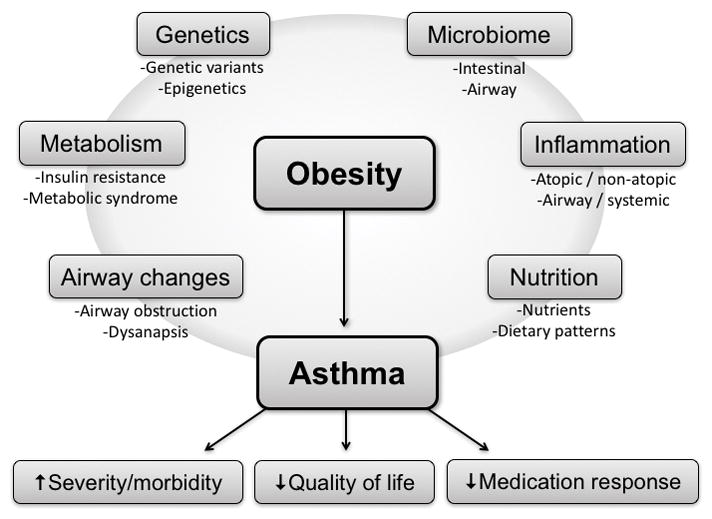

While in some children obesity and asthma simply co-occur, those with “obese asthma” have increased asthma severity, lower quality of life, and reduced medication response. Underlying mechanistic pathways may include anatomical changes of the airways such as obstruction and dysanapsis; systemic inflammation; production of adipokines; impaired glucose-insulin metabolism; altered nutrient levels; genetic and epigenetic changes; and alterations in the airway and/or gut microbiome. A few small studies have shown that weight loss interventions may lead to improvements in asthma outcomes, but thus far research on therapeutic interventions for these children has been limited.

Summary

Obesity increases the risk of asthma –and worsens asthma severity or control– via multiple mechanisms. “Obese asthma” is a complex, multifactorial phenotype in children. Obesity and its complications must be managed as part of the treatment of asthma in obese children.

Keywords: obese asthma, obesity-induced asthma, airway dysanapsis, metabolic syndrome, insulin resistance, diet and asthma, adipokines and asthma, microbiome and asthma

Introduction

Obesity is a well-known risk factor for cardiovascular disease and type-2 diabetes, and the processes that lead to these diseases may start in childhood and adolescence. Likewise, recent and growing evidence shows that childhood obesity affects the respiratory system. Obesity and its metabolic complications may affect lung function in otherwise healthy children, and increase the risk of new-onset asthma. This may start as early as in utero among children born to obese mothers. Among children with asthma, obesity is associated with increased symptoms and morbidity, decreased response to medications, and poorer quality of life. Here, we review recent evidence supporting a causal relation between obesity and asthma and the mechanisms that may underlie this link (see Figure 1), as well as the importance of taking obesity into consideration when treating children with “obese asthma”.

Figure 1. Multifactorial effects of obesity on childhood asthma.

The figure depicts several mechanisms by which obesity affects asthma and asthma morbidity, with particular emphasis on pathways that have been the focus of research over the past 1–2 years, as described in this review.

Epidemiology of obesity and asthma

From 2001 to 2010, the prevalence of childhood asthma increased 1.4% per year in the U.S., and currently over 6.3 million (~9%) children have asthma in this country1. Of these children, approximately 60% have persistent asthma, 58% have at least one exacerbation per year, and ~38.4% have uncontrolled symptoms1.

Obesity affects 12.7 million (17%) children and adolescents in the U.S. (with another 15% being overweight)2. Like childhood asthma, obesity disproportionately affects racial/ethnic minorities and those from lower socioeconomic status: up to 20–22% of Hispanics and non-Hispanic blacks are obese, compared to 14% of non-Hispanic whites. Moreover, obesity affects ~20% of children whose adult head of household did not finish high school, compared to ~10% of children whose head of household completed college2. Childhood overweight and obesity constitute modifiable risk factors for cardiovascular disease, insulin resistance, diabetes, gastro-esophageal reflux disease (GERD), obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), and fatty liver disease. Since 2015, the CDC has also listed obesity as a major risk factor for childhood asthma.

“Obese asthma” in childhood

There is solid epidemiological evidence to support obesity as a risk factor for incident asthma3–5. While obesity and asthma may simply co-occur in some children, growing evidence points towards the existence of an “obese asthma” phenotype in children6,7, in which obesity affects and modifies the asthma phenotype. This phenotype is likely complex and multifactorial, and our understanding of its subjacent causes and characteristics is far from complete.

Among children with asthma, obesity leads to increased symptoms, worse control8, more frequent and/or severe exacerbations9–12, decreased response to inhaled corticosteroids (ICS)13, and lower quality of life14. In a recent analysis of over 100,000 hospitalizations for asthma, obesity was associated with higher odds of mechanical ventilation and longer length of stay11. Although many studies have reported differing effects of obesity on asthma by sex15–18, their results have been conflicting and thus further research is needed on this topic.

Maternal obesity during pregnancy and weight gain in early post-natal life

In a meta-analysis of fourteen studies encompassing over 108,000 mother-child dyads, maternal obesity and maternal weight gain during pregnancy were associated with 21–31% and ~16% increased risk of asthma in the offspring19, respectively. Similar findings were reported in a recent study of almost 13,000 participants, with maternal pre-pregnancy overweight/obesity leading to 19–34% increased odds of childhood asthma20. In this study, boys were more likely to have non-atopic asthma and girls more likely to have atopic asthma20.

The increased risk of asthma conferred by maternal obesity or weight gain during pregnancy is beyond that of any indirect effect mediated by the child’s own obesity21, and may be explained by several mechanisms. Maternal obesity leads to changes in immune cell counts –including eosinophils and monocytes, the levels of inflammatory cytokines (i.e. interleukin [IL]-1β, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor [TNF]-α, or interferon [IFN]-α2)22,23, and lipid profiles in cord blood or early post-natal life25. Moreover, maternal obesity may lead to metabolic and oxidative alterations in the placenta and the fetus24, and increased leptin level and insulin resistance in newborns26. Such pronounced changes may partly explain why excessive –or accelerated– weight gain in the first few months or years of life has also been linked to recurrent wheezing and incident asthma27,28.

Airway anatomy, mechanics, and physiology

A restrictive lung deficit –with decreased lung volumes, low FEV1 and FVC, and a normal FEV1/FVC ratio– has been reported in obese adults29,30. On the other hand, obese children have been shown to have a low FEV1/FVC ratio3,31 consistent with an obstructive deficit that could partly account for their increased asthma morbidity. For example, a study of over 2,700 children Taiwanese children showed that low FEV1/FVC was the most significant “mediator” between central obesity and active childhood asthma32. Moreover, normal-weight children with asthma who become obese in early adulthood have further worsening of FEV1/FVC (up to ~3% per each 10-kg/m2 change in BMI), without significant changes in FVC33.

Of interest, some obese children tend to have higher FVC and FEV1 than their non-obese counterparts34,35. We recently reported that obesity is associated with airway dysanapsis (an incongruence in the growth of the lung parenchyma and the caliber of the airways that leads to larger lungs with flows that are normal but comparatively appear to be low) in several cohorts of children with and without asthma36. These children had normal/high FVC, normal FEV1, and low FEV1/FVC. Moreover, airway dysanapsis was associated with reduced response to albuterol or long-term ICS treatment in these children. This relative obstruction may thus be a “developmental” feature instead of a marker of uncontrolled asthma, partly explaining why some obese asthmatic children have reduced response to bronchodilators37 and ICS13. Overweight and obesity have also been correlated with lower maximal inspiratory pressures (MIP)38, further suggesting a complex compromise of pulmonary function in obese children. Future studies should help elucidate how these dysanaptic or obstructive defects in childhood and adolescence relate to the restrictive deficit found during adulthood.

Inflammation

Whether obesity increases atopic inflammation is unclear, as some studies report that obesity is associated with atopy39–41 but others report no association or an association with non-atopic asthma42,43. In a recent study using data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), obesity was associated with asthma only among adolescents without eosinophilic airway inflammation. However, obesity was associated with increased disease among asthmatic children with eosinophilic airway inflammation44. These findings suggest that obesity predisposes to non-atopic asthma, while also increasing disease morbidity in children with atopic asthma (in whom obesity and atopy may have joint detrimental effects).

Beyond the airway, the systemic inflammatory milieu of obesity could also play an important role in asthma. Obese asthma may be related to Th1 rather than Th2 inflammatory profiles; such Th1 polarization has been associated with metabolic abnormalities, worse asthma severity and control, and abnormal lung function45. Different cytokines and adipokines associated with obesity may play a significant role, as evidenced by studies linking higher leptin and/or lower adiponectin with worse asthma severity or control42,46. Components of the innate immune system such as Th17 pathways and innate lymphoid cells have also been implicated47,48. Like other characteristics of obese asthma, its inflammatory profile is dynamic and may differ by sex and life stage. For example, a recent study found evidence of more prominent macrophage activation among girls, with soluble CD163 (a marker of macrophage activation) associated with higher android fat deposition, lower FEV1, and worse asthma control49.

Diet and nutrients

Dietary factors are evidently associated with childhood obesity, and several studies over the past few years have reported similar associations with asthma50. Breastfeeding51,52 and the Mediterranean diet53,54 have each been associated to lower risk of both obesity and asthma. We recently described that a diet abundant in sweets and dairy products is associated with increased asthma risk (and with higher serum IL-17F), while frequent consumption of vegetables and grains was linked to lower odds of asthma55. High-fat meals can lead to neutrophilic airway inflammation and decreased bronchodilator response among patients with asthma56. Among specific nutrients, low vitamin D could represent a common path for both obesity and asthma57. In a recent analysis, vitamin D deficiency was associated with low lung function among obese children with asthma, but not among those of normal weight58. Another recent study reported that high BMI was associated with asthma exacerbations among children with low vitamin D, with cathelicidin (an innate immunity polypeptide found in macrophages and neutrophils) potentially playing a mediating role59. Omega-3 and omega-6 fatty acids have also been linked to asthma60, and fish oil supplementation in early life has been reported to modulate immune responses61. Research is lacking, however, on whether dietary modifications can prospectively reduce obesity-related asthma risk or morbidity.

Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome

Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome have been associated with lower lung function in adolescents with and without asthma, with a more pronounced effect among those with asthma (up to 10% lower FEV1/FVC than that of healthy adolescents)62. More recently, obesity was shown to be associated with airway hyper-responsiveness (AHR) in children with asthma and coexisting insulin resistance63, but not in those with asthma but no insulin resistance. This could partly explain why some prior reports found no association between obesity and AHR. Several studies have associated dyslipidemia with asthma, independent of –or in synergy with– obesity64–66. Potential mechanisms for a causal effect of insulin resistance on asthma include Th1 polarization45, increased allergic sensitization67, increased oxidative stress68, airway smooth muscle dysfunction and fibroblast proliferation69,70, or airway epithelial damage, among others.

Genetics and genomics

While obesity and asthma have significant hereditary components, results from studies looking at the genetic determinants of “obese asthma” have been inauspicious. In a large study of over 23,000 children, only DENND1B (DENN Domain Containing 1B) was associated with both BMI and asthma71. Candidate-gene studies have reported associations or interactions between obesity and genes including PRKCA (protein kinase C alpha)72 and ADRB3 (adrenergic receptor beta-3)73 on asthma. More recent approaches have yielded more promising results: a study looking at asthma genes selected from the literature reported effect size differences between asthma risk in normal-weight children vs. obese children. After stratifying the analysis by obesity, that study replicated four potential asthma genes in normal-weight children, 17 in obese children, and five in both normal-weight and obese children74. Moreover, a recent Mendelian randomization study reported that a weighted allele score using 32 SNPs previously associated with BMI was also strongly associated asthma at ~7 years of age5.

Obese asthma may also be caused by epigenetic mechanisms. A recent study identified significant DNA methylation changes in peripheral blood mononuclear cells in children with obesity and asthma75, and a study in mice and humans reported that CHI3L1 (chitinase 3-like 1) can be induced by a high-fat diet, and contributes to truncal obesity and asthma symptoms76.

The microbiome

Exposure to antibiotics in early life has been associated with both asthma77 and obesity78. While confounding by respiratory infections may partly explain the estimated effect of antibiotics on asthma, the same is not true for potential effects of antibiotic use on obesity. Alterations in the nasal or airway microbiome have been described in asthma79. Similarly, changes in the gut microbiome have been implicated in the pathogenesis of obesity80 and atopic diseases (including asthma)81,82. Moreover, aberrant responses to these microbiota have been reported to precede asthma and allergy83. Probiotic supplementation has been shown to reduce the risk of atopy84 but not asthma.

Our understanding of the importance of the microbiome in both obesity and asthma is still incipient, and several aspects –such as sampling-related variability85– need to be addressed. Nonetheless, obesity could plausibly induce or facilitate changes in the microbiome that lead to asthma. Alternatively, microbiome-host dysfunction may increase the risk of both obesity and asthma. Several factors associated with asthma, including living in an urban environment, diet, Caesarean delivery, or repeated antibiotic use, could be linked to the microbiome and –in some children– obesity. Future research in this field could yield preventive or therapeutic approaches for patients with obese asthma86.

Misclassification

Researchers and clinicians must be aware that not all children with co-existing obesity and asthma have “obese asthma”. Comorbidities such as OSA or GERD may cause difficulty breathing or chest pain/tightness87,88, and obesity (and related deconditioning) may lead to dyspnea or exercise limitation89,90. Such symptoms can mimic asthma and lead to misdiagnosis or misattribution. Moreover, some children with severe asthma (or whose parents perceive it to be severe) may have reduced physical activity leading to obesity (“reverse causation”)91.

Much of the existing literature has used BMI to define obesity. Recent evidence suggests that, while convenient, BMI may not be the best measure to encapsulate the complexities of “obese asthma”16,92–95. Most, but not all96 of these studies have reported that other measures of adiposity type and distribution may increase our understanding of “obese asthma” phenotypes (e.g., central vs. truncal obesity).

Weight loss and management of obesity complications

In spite of growing awareness of “obese asthma”, this entity is not being appropriately recognized and managed. For example, a recent study showed that less than 10% of obese children who had been hospitalized with asthma had an obesity discharge code or received treatment for their obesity97.

Data are scarce on weight loss in children with asthma. In a pilot study of 28 children, diet-induced weight loss in obese children with asthma was associated with improved asthma control and lower C-reactive protein (CRP)98. Similarly, a non-controlled intervention study of 20 children, diet-induced weight loss was associated with decreased exercise-induced bronchospasm99. A recent randomized, controlled trial (RCT) in 87 children improved asthma outcomes for both the intervention (weight loss) and control groups, with some effects –such as asthma control and quality of life– being more pronounced in the intervention group100. In another RCT in 51 adolescents, a normo-caloric diet led to reductions in BMI that correlated with improved quality of life and reduced asthma exacerbations101. While these results are promising and should prompt providers to consider managing obesity in children asthma, larger RCTs are needed to further elucidate the effects of weight loss on “obese asthma” in children.

Beyond weight loss, few other therapeutic options have been explored in “obese asthma”. A recent retrospective study in adults found that the use of metformin among patients with diabetes and asthma was associated with improved asthma outcomes102. Metformin, which acts via AMP-protein kinase (AMPK), has been shown to decrease eosinophilic airway inflammation and inhibit airway smooth muscle hypertrophy in murine models103,104. A recent meta-analysis showed a modest reduction in BMI from metformin use in non-diabetic obese adolescents105, and another study showed improved insulin profiles106. Thus, metformin may represent a possible adjunct therapy in obese asthma that warrants further investigation. Finally, some studies in adults have suggested that, while response to ICS may be decreased, response to leukotriene antagonists may be preserved in obese subjects with asthma106.

Conclusions

Obesity increases the risk of incident asthma and worsens asthma severity or control via multiple mechanisms. Thus, obesity and its complications should be managed as part of the treatment of “obese asthma” in children. Like both obesity and asthma, “obese asthma” is a complex phenotype in children. While our understanding of this phenotype has increased over the last few years, its underlying mechanistic pathways and appropriate management approach are far from fully elucidated and warrant further research.

Key Points.

Obesity increases the risk of incident asthma and asthma-related morbidity in children. “Obese asthma” is a complex phenotype, and potential contributing mechanisms include abnormalities in airway and lung mechanics, airway and systemic inflammation, dietary and nutrient imbalances, changes in the gut and airway microbiome, and epigenetic changes.

Large clinical studies are needed to assess whether weight loss leads to significant improvements in asthma severity or control; and whether pharmacological treatment of obesity and its complications play a role in asthma management in these patients.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Dr. Forno’s contribution was supported by grant HL125666 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by a grant from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Dr. Celedón’s contribution was supported by grants HL079966, HL117191 and HL119952 from the US NIH, and by The Heinz Endowments.

Financial support and sponsorship: Dr. Forno’s contribution was supported by grant HL125666 from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) and by a grant from Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh of UPMC. Dr. Celedón’s contribution was supported by grants HL079966, HL117191 and HL119952 from the US NIH, and by The Heinz Endowments.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.CDC. Asthma Data, Statistics, and Surveillance. Most Recent Asthma Data. 2016 [updated 4/14/2016; cited 2016 10/18/2016] Available from: http://www.cdc.gov/asthma/most_recent_data.htm.

- 2.CDC. Childhood Obesity. 2016 [updated 11/09/2015; cited 2016 10/18/2016]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/obesity/childhood/index.html.

- 3**.Weinmayr G, Forastiere F, Buchele G, Jaensch A, Strachan DP, Nagel G, et al. Overweight/obesity and respiratory and allergic disease in children: international study of asthma and allergies in childhood (ISAAC) phase two. PLoS One. 2014;9(12):e113996. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0113996. Large epidemiological study of asthma in over 10,000 children from 24 countries that reported that overweight/obesity is associated with both asthma and lower lung function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mebrahtu TF, Feltbower RG, Greenwood DC, Parslow RC. Childhood body mass index and wheezing disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Feb;26(1):62–72. doi: 10.1111/pai.12321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5**.Granell R, Henderson AJ, Evans DM, Smith GD, Ness AR, Lewis S, et al. Effects of BMI, fat mass, and lean mass on asthma in childhood: a Mendelian randomization study. PLoS Med. 2014 Jul;11(7):e1001669. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001669. Mendelian randomization study in ~4,8000 children that used information from single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with obesity, in order to evaluate the causal association between obesity and asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wood LG. Metabolic dysregulation. Driving the obese asthma phenotype in adolescents? Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jan 15;191(2):121–2. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201412-2221ED. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7*.Lang JE, Hossain J, Dixon AE, Shade D, Wise RA, Peters SP, et al. Does age impact the obese asthma phenotype? Longitudinal asthma control, airway function, and airflow perception among mild persistent asthmatics. Chest. 2011 Dec;140(6):1524–33. doi: 10.1378/chest.11-0675. Longitudinal study that evaluated 490 children with asthma over the course of a 16-week clinical trial, and reported that age (and gender) modify the obesity-asthma association. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Borrell LN, Nguyen EA, Roth LA, Oh SS, Tcheurekdjian H, Sen S, et al. Childhood obesity and asthma control in the GALA II and SAGE II studies. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Apr 1;187(7):697–702. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201211-2116OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahmadizar F, Vijverberg SJ, Arets HG, de Boer A, Lang JE, Kattan M, et al. Childhood obesity in relation to poor asthma control and exacerbation: a meta-analysis. Eur Respir J. 2016 Oct;48(4):1063–73. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00766-2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Denlinger LC, Phillips BR, Ramratnam S, Ross K, Bhakta NR, Cardet JC, et al. Inflammatory and Co-Morbid Features of Patients with Severe Asthma and Frequent Exacerbations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Aug 24; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201602-0419OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okubo Y, Nochioka K, Hataya H, Sakakibara H, Terakawa T, Testa M. Burden of Obesity on Pediatric Inpatients with Acute Asthma Exacerbation in the United States. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2016 Jun 30; doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2016.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aragona E, El-Magbri E, Wang J, Scheckelhoff T, Scheckelhoff T, Hyacinthe A, et al. Impact of Obesity on Clinical Outcomes in Urban Children Hospitalized for Status Asthmaticus. Hosp Pediatr. 2016 Apr;6(4):211–8. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13*.Forno E, Lescher R, Strunk R, Weiss S, Fuhlbrigge A, Celedon JC. Decreased response to inhaled steroids in overweight and obese asthmatic children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Mar;127(3):741–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.010. Epub 2011/03/08. eng. Post-hoc analysis of data from a clinical trial that found that overweight/obese children have a reduced response to inhaled corticosteroids. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Gent R, van der Ent CK, Rovers MM, Kimpen JL, van Essen-Zandvliet LE, de Meer G. Excessive body weight is associated with additional loss of quality of life in children with asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007 Mar;119(3):591–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.11.007. Epub 2007/01/09. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lu KD, Billimek J, Bar-Yoseph R, Radom-Aizik S, Cooper DM, Anton-Culver H. Sex Differences in the Relationship between Fitness and Obesity on Risk for Asthma in Adolescents. J Pediatr. 2016 Sep;176:36–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.05.050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maltz L, Matz EL, Gordish-Dressman H, Pillai DK, Teach SJ, Camargo CA, Jr, et al. Sex differences in the association between neck circumference and asthma. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016 Sep;51(9):893–900. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castro-Rodriguez JA. A new childhood asthma phenotype: obese with early menarche. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016 Mar;18:85–9. doi: 10.1016/j.prrv.2015.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Willeboordse M, van den Bersselaar DL, van de Kant KD, Muris JW, van Schayck OC, Dompeling E. Sex differences in the relationship between asthma and overweight in Dutch children: a survey study. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e77574. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Forno E, Young OM, Kumar R, Simhan H, Celedon JC. Maternal obesity in pregnancy, gestational weight gain, and risk of childhood asthma. Pediatrics. 2014 Aug;134(2):e535–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-0439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20*.Dumas O, Varraso R, Gillman MW, Field AE, Camargo CA., Jr Longitudinal study of maternal body mass index, gestational weight gain, and offspring asthma. Allergy. 2016 Sep;71(9):1295–304. doi: 10.1111/all.12876. Large longitudinal study of almost 13,000 mother-child pairs that found increased risk of asthma in the offspring of mothers who were obese during pregnancy, and also found differing effects of obesity on childhood asthma by allergic status and sex. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Harskamp-van Ginkel MW, London SJ, Magnus MC, Gademan MG, Vrijkotte TG. A Study on Mediation by Offspring BMI in the Association between Maternal Obesity and Child Respiratory Outcomes in the Amsterdam Born and Their Development Study Cohort. PLoS One. 2015;10(10):e0140641. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0140641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Wilson RM, Marshall NE, Jeske DR, Purnell JQ, Thornburg K, Messaoudi I. Maternal obesity alters immune cell frequencies and responses in umbilical cord blood samples. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Jun;26(4):344–51. doi: 10.1111/pai.12387. In this study, umbilical cord blood from babies born to obese mothers had lower eosinophil and CD4 T-helper cells, altered monocyte and dendritic cell responses, and higher IL-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dosch NC, Guslits EF, Weber MB, Murray SE, Ha B, Coe CL, et al. Maternal Obesity Affects Inflammatory and Iron Indices in Umbilical Cord Blood. J Pediatr. 2016 May;172:20–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malti N, Merzouk H, Merzouk SA, Loukidi B, Karaouzene N, Malti A, et al. Oxidative stress and maternal obesity: feto-placental unit interaction. Placenta. 2014 Jun;35(6):411–6. doi: 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Costa SM, Isganaitis E, Matthews TJ, Hughes K, Daher G, Dreyfuss JM, et al. Maternal obesity programs mitochondrial and lipid metabolism gene expression in infant umbilical vein endothelial cells. International journal of obesity. 2016 Oct 04; doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Catalano PM, Presley L, Minium J, Hauguel-de Mouzon S. Fetuses of obese mothers develop insulin resistance in utero. Diabetes Care. 2009 Jun;32(6):1076–80. doi: 10.2337/dc08-2077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Popovic M, Pizzi C, Rusconi F, Galassi C, Gagliardi L, De Marco L, et al. Infant weight trajectories and early childhood wheezing: the NINFEA birth cohort study. Thorax. 2016 Jul 1; doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-208208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28*.Casas M, den Dekker HT, Kruithof CJ, Reiss IK, Vrijheid M, de Jongste JC, et al. Early childhood growth patterns and school-age respiratory resistance, fractional exhaled nitric oxide and asthma. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016 Oct 5; doi: 10.1111/pai.12645. Population-based cohort of over 5,300 children, which reported that BMI and peak weight gain velocity before age 3 years are both associated with risk of early and persistent wheezing. Peak height velocity was associated with lower respiratory resistance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beuther DA, Weiss ST, Sutherland ER. Obesity and asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2006 Jul 15;174(2):112–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200602-231PP. Epub 2006/04/22. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wei YF, Wu HD, Chang CY, Huang CK, Tai CM, Hung CM, et al. The impact of various anthropometric measurements of obesity on pulmonary function in candidates for surgery. Obes Surg. 2010 May;20(5):589–94. doi: 10.1007/s11695-009-9961-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cibella F, Bruno A, Cuttitta G, Bucchieri S, Melis MR, De Cantis S, et al. An elevated body mass index increases lung volume but reduces airflow in Italian schoolchildren. PLoS One. 2015;10(5):e0127154. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0127154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32*.Chih AH, Chen YC, Tu YK, Huang KC, Chiu TY, Lee YL. Mediating pathways from central obesity to childhood asthma: a population-based longitudinal study. Eur Respir J. 2016 Sep;48(3):748–57. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00226-2016. Large population-based study of Taiwanese children, which reported an association between central obesity (waist-to-hip ratio) and asthmathat was significantly mediated by low lung function (FEV1/FVC), atopy, and eosinophilic airway inflammation. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Strunk RC, Colvin R, Bahcarier LB, Fuhlbrigge A, Forno E, Arbelaez Tantisira KG. Airway obstruction worsens in young adults with asthma who become obese. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2015 Sep-Oct;3(5):765–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2015.05.009. Epub 2015 Jul 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Del Rio-Navarro BE, Blandon-Vijil V, Escalante-Dominguez AJ, Berber A, Castro-Rodriguez JA. Effect of obesity on bronchial hyperreactivity among Latino children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2013 Dec;48(12):1201–5. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen YC, Huang YL, Ho WC, Wang YC, Yu YH. Gender differences in effects of obesity and asthma on adolescent lung function: Results from a population-based study. J Asthma. 2016 Jul;19:1–7. doi: 10.1080/02770903.2016.1212367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36**.Forno E, Weiner DJ, Mullen J, Sawicki G, Kurland G, Han YY, et al. Obesity and Airway Dysanapsis in Children With and Without Asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016 Aug 23; doi: 10.1164/rccm.201605-1039OC. In this analysis of six cohorts of children with and without asthma, obesity was associated with airway dysanapsis (an incongruence in lung and airway growth), and dysanapsis in turn was associated with increased asthma morbidity in obese children. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37*.McGarry ME, Castellanos E, Thakur N, Oh SS, Eng C, Davis A, et al. Obesity and bronchodilator response in black and Hispanic children and adolescents with asthma. Chest. 2015 Jun;147(6):1591–8. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-2689. In this analysis of a cohort of Latino and black children, obesity was associated with decreased response to albuterol, and these obese children with decreased treatment response reported increased asthma symptoms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.da Rosa GJ, Schivinski CI. Assessment of respiratory muscle strength in children according to the classification of body mass index. Rev Paul Pediatr. 2014 Jun;32(2):250–5. doi: 10.1590/0103-0582201432210313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Forno E, Acosta-Perez E, Brehm JM, Han YY, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, et al. Obesity and adiposity indicators, asthma, and atopy in Puerto Rican children. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 May;133(5):1308–14. 14 e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2013.09.041. Epub Nov 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray CS, Canoy D, Buchan I, Woodcock A, Simpson A, Custovic A. Body mass index in young children and allergic disease: gender differences in a longitudinal study. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011 Jan;41(1):78–85. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2010.03598.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nordlund B, Melen E, Schultz ES, Gronlund H, Hedlin G, Kull I. Risk factors and markers of asthma control differ between asthma subtypes in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014 Oct;25(6):558–64. doi: 10.1111/pai.12271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kattan M, Kumar R, Bloomberg GR, Mitchell HE, Calatroni A, Gergen PJ, et al. Asthma control, adiposity, and adipokines among inner-city adolescents. The Journal of allergy and clinical immunology. 2010;125(3):584–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Visness CM, London SJ, Daniels JL, Kaufman JS, Yeatts KB, Siega-Riz AM, et al. Association of childhood obesity with atopic and nonatopic asthma: results from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 1999–2006. J Asthma. 2010 Sep;47(7):822–9. doi: 10.3109/02770903.2010.489388. Epub 2010/08/17. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44*.Han YY, Forno E, Celedon JC. Adiposity, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and asthma in U.S children. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014 Jul 1;190(1):32–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0565OC. In this analysis, the authors report that obesity is only associated with asthma in children without atopic airway inflammation, but that obesity makes asthma worse in children with asthma and atopy. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45*.Rastogi D, Fraser S, Oh J, Huber AM, Schulman Y, Bhagtani RH, et al. Inflammation, metabolic dysregulation, and pulmonary function among obese urban adolescents with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jan 15;191(2):149–60. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201409-1587OC. In this study, the authors looked at 168 adolescents with or without asthma or obesity and evaluated the associations between obesity, metabolic abnormalities, lung function, and asthma symptoms. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46**.Sood A, Shore SA. Adiponectin, Leptin, and Resistin in Asthma: Basic Mechanisms through Population Studies. Journal of allergy. 2013;2013:785835. doi: 10.1155/2013/785835. Interesting review of the role of adipokines leptin, adiponectin, and resistin in asthma, looking both at animal studies and epidemiological human studies. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Everaere L, Ait-Yahia S, Molendi-Coste O, Vorng H, Quemener S, LeVu P, et al. Innate lymphoid cells contribute to allergic airway disease exacerbation by obesity. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Apr 4; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48**.Kim HY, Lee HJ, Chang YJ, Pichavant M, Shore SA, Fitzgerald KA, et al. Interleukin-17-producing innate lymphoid cells and the NLRP3 inflammasome facilitate obesity-associated airway hyperreactivity. Nat Med. 2014 Jan;20(1):54–61. doi: 10.1038/nm.3423. Study looking at the role of innate lymphoid cells and IL-17 in asthma. High-fat fed mice developed airway-hyperreactivity, which was dependent on IL-17 producing innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49*.Periyalil HA, Wood LG, Scott HA, Jensen ME, Gibson PG. Macrophage activation, age and sex effects of immunometabolism in obese asthma. Eur Respir J. 2015 Feb;45(2):388–95. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00080514. This study looked at the associations between body composition, several adipokines, and asthma outcomes. The authors found that sCD163, a marker of macrophage activation, was associated with obesity and lower lung function in obese girls. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berentzen NE, van Stokkom VL, Gehring U, Koppelman GH, Schaap LA, Smit HA, et al. Associations of sugar-containing beverages with asthma prevalence in 11-year-old children: the PIAMA birth cohort. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2015 Mar;69(3):303–8. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2014.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Dogaru CM, Nyffenegger D, Pescatore AM, Spycher BD, Kuehni CE. Breastfeeding and childhood asthma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol. 2014 May 15;179(10):1153–67. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwu072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan J, Liu L, Zhu Y, Huang G, Wang PP. The association between breastfeeding and childhood obesity: a meta-analysis. BMC public health. 2014 Dec 13;14:1267. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-1267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rice JL, Romero KM, Galvez Davila RM, Meza CT, Bilderback A, Williams DL, et al. Association Between Adherence to the Mediterranean Diet and Asthma in Peruvian Children. Lung. 2015 Dec;193(6):893–9. doi: 10.1007/s00408-015-9792-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lv N, Xiao L, Ma J. Dietary pattern and asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of asthma and allergy. 2014;7:105–21. doi: 10.2147/JAA.S49960. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Han YY, Forno E, Brehm J, Acosta-Perez E, Alvarez M, Colon-Semidey A, et al. Diet, Interleukin-17, and Childhood Asthma in Puerto Ricans. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2015 Aug 26; doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2015.07.020. Epub ahead of print Epub Jul 8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56*.Wood LG, Garg ML, Gibson PG. A high-fat challenge increases airway inflammation and impairs bronchodilator recovery in asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 May;127(5):1133–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.036. In this study, the investigators demonstrated that one high-fat meal can increase neutrophilic airway inflammation and supress bronchodilator recovery. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vo P, Bair-Merritt M, Camargo CA. The potential role of vitamin D in the link between obesity and asthma severity/control in children. Expert Rev Respir Med. 2015 Jun;9(3):309–25. doi: 10.1586/17476348.2015.1042457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58*.Lautenbacher LA, Jariwala SP, Markowitz ME, Rastogi D. Vitamin D and pulmonary function in obese asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016 Jun 6; doi: 10.1002/ppul.23485. Study reporting that vitamin D deficiency is associated with lower lung function among obese children with asthma, but not among those of normal weight. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Arikoglu T, Kuyucu S, Karaismailoglu E, Batmaz SB, Balci S. The association of vitamin D, cathelicidin, and vitamin D binding protein with acute asthma attacks in children. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2015 Jul-Aug;36(4):51–8. doi: 10.2500/aap.2015.36.3848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Li J, Xun P, Zamora D, Sood A, Liu K, Daviglus M, et al. Intakes of long-chain omega-3 (n-3) PUFAs and fish in relation to incidence of asthma among American young adults: the CARDIA study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013 Jan;97(1):173–8. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.112.041145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.D’Vaz N, Meldrum SJ, Dunstan JA, Lee-Pullen TF, Metcalfe J, Holt BJ, et al. Fish oil supplementation in early infancy modulates developing infant immune responses. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012 Aug;42(8):1206–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2012.04031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62*.Forno E, Han YY, Muzumdar RH, Celedon JC. Insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome, and lung function in US adolescents with and without asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Aug;136(2):304–11. e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2015.01.010. Insulin resistance and the metabolic syndrome are associated with decreased lung function in obese adolescents with and without asthma, with a worse decrease in those with asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63*.Karampatakis N, Karampatakis T, Galli-Tsinopoulou A, Kotanidou EP, Tsergouli K, Eboriadou-Petikopoulou M, et al. Impaired glucose metabolism and bronchial hyperresponsiveness in obese prepubertal asthmatic children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016 Jun 30; doi: 10.1002/ppul.23516. Obesity is associated with airway hyper-reactivity only among children with insulin resistance and glucose intolerance. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cottrell L, Neal WA, Ice C, Perez MK, Piedimonte G. Metabolic abnormalities in children with asthma. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011 Feb 15;183(4):441–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201004-0603OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Del-Rio-Navarro BE, Castro-Rodriguez JA, Garibay Nieto N, Berber A, Toussaint G, Sienra-Monge JJ, et al. Higher metabolic syndrome in obese asthmatic compared to obese nonasthmatic adolescent males. J Asthma. 2010 Jun;47(5):501–6. doi: 10.3109/02770901003702808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Chen YC, Tung KY, Tsai CH, Su MW, Wang PC, Chen CH, et al. Lipid profiles in children with and without asthma: interaction of asthma and obesity on hyperlipidemia. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2013 Jan-Mar;7(1):20–5. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2013.02.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sanchez Jimenez J, Herrero Espinet FJ, Mengibar Garrido JM, Roca Antonio J, Penos Mayor S, del Penas Boira MM, et al. Asthma and insulin resistance in obese children and adolescents. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2014 Nov;25(7):699–705. doi: 10.1111/pai.12294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Singh VP, Aggarwal R, Singh S, Banik A, Ahmad T, Patnaik BR, et al. Metabolic Syndrome Is Associated with Increased Oxo-Nitrative Stress and Asthma-Like Changes in Lungs. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0129850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dekkers BG, Schaafsma D, Tran T, Zaagsma J, Meurs H. Insulin-induced laminin expression promotes a hypercontractile airway smooth muscle phenotype. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2009;41(4):494–504. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2008-0251OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Agrawal A, Mabalirajan U, Ahmad T, Ghosh B. Emerging interface between metabolic syndrome and asthma. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2011 Mar;44(3):270–5. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0141TR. Epub 2010/07/27. eng. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71*.Melen E, Granell R, Kogevinas M, Strachan D, Gonzalez JR, Wjst M, et al. Genome-wide association study of body mass index in 23 000 individuals with and without asthma. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013 Apr;43(4):463–74. doi: 10.1111/cea.12054. Large GWAS of BMI in children and adults with and without asthma, reported that DENND1B was a significant SNP for BMI; DENND1B has also been associated with asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Murphy A, Tantisira KG, Soto-Quiros ME, Avila L, Klanderman BJ, Lake S, et al. PRKCA: a positional candidate gene for body mass index and asthma. American Journal of Human Genetics. 2009;85(1):87–96. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kuo NW, Tung KY, Tsai CH, Chen YC, Lee YL. beta3-Adrenergic receptor gene modifies the association between childhood obesity and asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2014 Sep;134(3):731–3. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Butsch Kovacic M, Martin LJ, Biagini Myers JM, He H, Lindsey M, Mersha TB, et al. Genetic approach identifies distinct asthma pathways in overweight vs normal weight children. Allergy. 2015 Aug;70(8):1028–32. doi: 10.1111/all.12656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rastogi D, Suzuki M, Greally JM. Differential epigenome-wide DNA methylation patterns in childhood obesity-associated asthma. Scientific reports. 2013;3:2164. doi: 10.1038/srep02164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76**.Ahangari F, Sood A, Ma B, Takyar S, Schuyler M, Qualls C, et al. Chitinase 3-like-1 regulates both visceral fat accumulation and asthma-like Th2 inflammation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Apr 1;191(7):746–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201405-0796OC. High-fat diet in mice induces CHI3L1 expression in adipose tissue and lung, and in turn CHI3LI led to Th2 inflammation in the lungs. In humans, serum Chi3l1 levels were associated with adiposity, persistent asthma, and lower lung function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Pitter G, Ludvigsson JF, Romor P, Zanier L, Zanotti R, Simonato L, et al. Antibiotic exposure in the first year of life and later treated asthma, a population based birth cohort study of 143,000 children. Eur J Epidemiol. 2016 Jan;31(1):85–94. doi: 10.1007/s10654-015-0038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bailey LC, Forrest CB, Zhang P, Richards TM, Livshits A, DeRusso PA. Association of antibiotics in infancy with early childhood obesity. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Nov;168(11):1063–9. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.1539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Depner M, Ege MJ, Cox MJ, Dwyer S, Walker AW, Birzele LT, et al. Bacterial microbiota of the upper respiratory tract and childhood asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Jul 27; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Khan MJ, Gerasimidis K, Edwards CA, Shaikh MG. Role of Gut Microbiota in the Aetiology of Obesity: Proposed Mechanisms and Review of the Literature. Journal of obesity. 2016;2016:7353642. doi: 10.1155/2016/7353642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Forno E, Onderdonk AB, McCracken J, Litonjua AA, Laskey D, Delaney ML, et al. Diversity of the gut microbiota and eczema in early life. Clin Mol Allergy. 2008;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1476-7961-6-11. Epub 2008/09/24. eng. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82**.Fujimura KE, Sitarik AR, Havstad S, Lin DL, Levan S, Fadrosh D, et al. Neonatal gut microbiota associates with childhood multisensitized atopy and T cell differentiation. Nat Med. 2016 Oct;22(10):1187–91. doi: 10.1038/nm.4176. In this study, researchers identify different patterns of neonatal gut microbiota, one of which was associated with higher risk of atopy and asthma. One mechanism identified is the increase in IL-4 producing CD4+ T-cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dzidic M, Abrahamsson TR, Artacho A, Bjorksten B, Collado MC, Mira A, et al. Aberrant IgA responses to the gut microbiota during infancy precede asthma and allergy development. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Aug 13; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Elazab N, Mendy A, Gasana J, Vieira ER, Quizon A, Forno E. Probiotic Administration in Early Life, Atopy, and Asthma: A Meta-analysis of Clinical Trials. Pediatrics. 2013 Sep;132(3):e666–76. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Perez-Losada M, Crandall KA, Freishtat RJ. Two sampling methods yield distinct microbial signatures in the nasopharynges of asthmatic children. Microbiome. 2016 Jun 16;4(1):25. doi: 10.1186/s40168-016-0170-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86**.Shore SA, Cho Y. Obesity and Asthma: Microbiome-Metabolome Interactions. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2016 May;54(5):609–17. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2016-0052PS. Noteworthy basic science review of how obesity may alter the microbiome, leading to metabolic changes that in turn lead to asthma. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lang JE, Hossain J, Holbrook JT, Teague WG, Gold BD, Wise RA, et al. Gastro-oesophageal reflux and worse asthma control in obese children: a case of symptom misattribution? Thorax. 2016 Mar;71(3):238–46. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207662. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Lang JE, Hossain MJ, Lima JJ. Overweight children report qualitatively distinct asthma symptoms: analysis of validated symptom measures. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Apr;135(4):886–93. e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Westergren T, Berntsen S, Carlsen KC, Mowinckel P, Haland G, Fegran L, et al. Perceived exercise limitation in asthma: the role of disease severity, overweight and physical activity in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2016 Oct 13; doi: 10.1111/pai.12670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Sah PK, Gerald Teague W, Demuth KA, Whitlock DR, Brown SD, Fitzpatrick AM. Poor asthma control in obese children may be overestimated because of enhanced perception of dyspnea. The journal of allergy and clinical immunology In practice. 2013 Jan;1(1):39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Leinaar E, Alamian A, Wang L. A systematic review of the relationship between asthma, overweight, and the effects of physical activity in youth. Ann Epidemiol. 2016 Jul;26(7):504–10. e6. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2016.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.den Dekker HT, Ros KP, de Jongste JC, Reiss IK, Jaddoe VW, Duijts L. Body fat mass distribution and interrupter resistance, fractional exhaled nitric oxide, and asthma at school-age. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Jul 16; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.06.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Forno E. Childhood obesity and asthma -to BMI or not to BMI? J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Sep 19; doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.08.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Hacihamdioglu B, Arslan M, Yesilkaya E, Gok F, Yavuz ST. Wider neck circumference is related to severe asthma in children. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2015 Aug;26(5):456–60. doi: 10.1111/pai.12402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Wisner E, Shah H, Sorenson R. The obesity-asthma link in different ages and the role of body mass index in its investigation: findings from the genesis and healthy growth studies. Pediatrics. 2014 Nov;134( Suppl 3):S168–9. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-1817III. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Egan KB, Ettinger AS, DeWan AT, Holford TR, Holmen TL, Bracken MB. General, but not abdominal, overweight increases odds of asthma among Norwegian adolescents: the Young-HUNT study. Acta Paediatr. 2014 Dec;103(12):1270–6. doi: 10.1111/apa.12775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Borgmeyer A, Ercole PM, Niesen A, Strunk RC. Lack of Recognition, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Overweight/Obesity in Children Hospitalized for Asthma. Hosp Pediatr. 2016 Oct 12; doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jensen ME, Gibson PG, Collins CE, Hilton JM, Wood LG. Diet-induced weight loss in obese children with asthma: a randomized controlled trial. Clin Exp Allergy. 2013 Jul;43(7):775–84. doi: 10.1111/cea.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.van Leeuwen JC, Hoogstrate M, Duiverman EJ, Thio BJ. Effects of dietary induced weight loss on exercise-induced bronchoconstriction in overweight and obese children. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2014 Dec;49(12):1155–61. doi: 10.1002/ppul.22932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100*.Willeboordse M, Kant KD, Tan FE, Mulkens S, Schellings J, Crijns Y, et al. A Multifactorial Weight Reduction Programme for Children with Overweight and Asthma: A Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS One. 2016;11(6):e0157158. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157158. Randomized controlled trial in 87 obese children with asthma over 18 months. Changes in BMI were associated with improvements in asthma control, quality of life, and lung function. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101*.Luna-Pech JA, Torres-Mendoza BM, Luna-Pech JA, Garcia-Cobas CY, Navarrete-Navarro S, Elizalde-Lozano AM. Normocaloric diet improves asthma-related quality of life in obese pubertal adolescents. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2014;163(4):252–8. doi: 10.1159/000360398. Randomized controlled trial of 51 adolescents with asthma over 28 weeks. Changes in BMI were associated with improvements in asthma quality of life and fewer exacerbations. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Li CY, Erickson SR, Wu CH. Metformin use and asthma outcomes among patients with concurrent asthma and diabetes. Respirology. 2016 Oct;21(7):1210–8. doi: 10.1111/resp.12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103*.Calixto MC, Lintomen L, Andre DM, Leiria LO, Ferreira D, Lellis-Santos C, et al. Metformin attenuates the exacerbation of the allergic eosinophilic inflammation in high fat-diet-induced obesity in mice. PLoS One. 2013;8(10):e76786. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0076786. In this study, the investigators report that metformin administration in obese mice led to reduced eosinophil airway infiltration, as well as reduced eosinophilic inflammatory activity in the airways and bronchoalveolar lavage. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ratnovsky A, Mellema M, An SS, Fredberg JJ, Shore SA. Airway smooth muscle proliferation and mechanics: effects of AMP kinase agonists. Mol Cell Biomech. 2007 Sep;4(3):143–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.McDonagh MS, Selph S, Ozpinar A, Foley C. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of metformin in treating obesity in children aged 18 years and younger. JAMA Pediatr. 2014 Feb;168(2):178–84. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106*.Marques P, Limbert C, Oliveira L, Santos MI, Lopes L. Metformin effectiveness and safety in the management of overweight/obese nondiabetic children and adolescents: metabolic benefits of the continuous exposure to metformin at 12 and 24 months. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2016 Feb 19; doi: 10.1515/ijamh-2015-0110. In this study, the authors found that metformin administration to obese (non-diabetic) adolescents was associated with improved insulin sensitivity, although BMI change was no different from that observed in adolescents in a lifestyle modification group. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Peters-Golden M, Swern A, Bird SS, Hustad CM, Grant E, Edelman JM. Influence of body mass index on the response to asthma controller agents. The European respiratory journal: official journal of the European Society for Clinical Respiratory Physiology. 2006;27(3):495–503. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00077205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]