Abstract

The shift to habitual bipedalism 4–6 million years ago in the hominin lineage created a morphologically and functionally different human pelvis compared to our closest living relatives, the chimpanzees. Evolutionary changes to the shape of the pelvis were necessary for the transition to habitual bipedalism in humans. These changes in the bony anatomy resulted in an altered role of muscle function, influencing bipedal gait. Additionally, there are normal sex-specific variations in the pelvis as well as abnormal variations in the acetabulum. During gait, the pelvis moves in the three planes to produce smooth and efficient motion. Subtle sex-specific differences in these motions may facilitate economical gait despite differences in pelvic structure. The motions of the pelvis and hip may also be altered in the presence of abnormal acetabular structure, especially with acetabular dysplasia.

Evolutionary changes in the shape of the human pelvis were necessary for habitual bipedalism. Fossil pelves early in the hominin lineage illustrate these adaptations including a wider sacrum and more laterally positioned flared ilia than what the human-chimpanzee last common ancestor is hypothesized to exhibit (Lovejoy 2005; Robinson 1972). These distinguishing characteristics early in hominin evolution allowed for lumbar lordosis, which is necessary to maintain the upright posture, as well as the conversion of hip extensors to hip abductors with an increased moment arm to balance the center of mass in the frontal plane (Lovejoy 2005; Robinson 1972). While the gait mechanics in fossil hominins has been debated (Berge 1994; Hunt 1994; Ruff 1998; Stern Jr and Susman 1983; Ward 2002), the modern human pelvis is adapted to habitual bipedality that results in specific pelvic motion during walking. These motions are thought to reduce energetic costs (Bramble and Lieberman 2004; Leonard and Robertson 1995; Saunders, Inman, Eberhart 1953). Potentially counter to the energetic cost savings, the female pelvis evolved to allow the birth of large-brained infants (Abitbol 1996; Caldwell and Moloy 1933; Lovejoy 2005; Meindl et al. 1985; Rosenberg 1992; Tague 1992; but see Warrener et al. 2015). Recent studies have challenged assumptions about the role of pelvic motion during gait and differences in that motion between males and females. The purpose of this article is to review the structure of the human pelvis and discuss the typical movements of the pelvis during human gait. Sex-specific variations in pelvis structure and two abnormal variations in acetabular structure and their influence on pelvic motion during gait will also be discussed.

Normal Structure of the Human Pelvis

The human pelvis includes the sacrum, the coccyx, and two os coxae (White, Black, Folkens 2011). Each os coxae is made up of three parts: the ischium, the ilium, and the pubis (White, Black, Folkens 2011). The articulations within the pelvis are: inferiorly between the sacrum and the coccyx (sacrococcygeal symphysis), posteriorly between the sacrum and each ilium (sacroiliac (SI) joint), and anteriorly between the pubic bodies (pubic symphysis). The SI joint offers some movement during childhood, but transitions to a modified synarthrodial joint, which allows little to no movement, by adulthood (Brooke 1924; Lovejoy et al. 1985). The pubic symphysis is a cartilaginous synarthordial joint with a fibrocartilaginous interpubic disc (Hagen 1974). This articulation allows a small amount of translation and rotation. As the pelvic ring creates a closed chain, movement at the pubic symphysis requires simultaneous movement at the SI joint, and vice versa.

The articulation between the pelvis and the femur is the acetabulum, which is formed by portions of the ilium, ischium, and pubis (White, Black, Folkens 2011). This synovial ball-and-socket joint allows substantial motion within the sagittal plane, with additional motion in the frontal and transverse planes. The acetabulum has articular cartilage in the shape of a horseshoe where the femoral head articulates with the os coxae. The normal orientation of the acetabulum is described as being rotated approximately 20–40 degrees off vertical in the frontal plane (Werner et al. 2012), and 20–30 degrees anteriorly (Merle et al. 2013; Murray 1993; Perreira et al. 2011; Reynolds, Lucas, Klaue 1999). This orientation positions the bone to provide the most stability medially, superiorly, and posteriorly.

In addition to the bony stability, other structures including the acetabular labrum, ligaments, and joint capsule, as well as muscles, provide stability anteriorly and laterally. The acetabular labrum, which is composed of fibrocartilage and dense connective tissue (Petersen, Petersen, Tillmann 2003), deepens the hip socket and helps provide a sealing mechanism for the joint (Hlavacek 2002; Tan et al. 2001). The primary hip ligaments (iliofemoral, ischiofemoral, and pubofemoral) each provide stability throughout different hip positions. All three ligaments, however, tighten as the hip moves into extension. The ligaments and capsule are most taut when the hip is in extension, slight internal rotation, and abduction (Neumann 2010b). Unlike at most other joints, this position of maximal ligamentous stability is not the position of maximal bony congruency. In the hip, maximal joint congruency occurs in 90 degrees of hip flexion with moderate hip abduction and external rotation. In addition to the capsular hip ligaments, smaller ligaments may also play a role in stability. For example, the ligamentum teres has recently been suggested to provide stability at end range hip motions, particularly hip abduction, medial rotation, and lateral rotation (Martin, Kivlan, Clemente 2013), and to prevent femoral head subluxation with combined hip flexion and abduction (Kivlan et al. 2013). The higher prevalence of ligamentum teres tears in individuals with decreased bony stability further supports this assertion (Domb, Martin, Botser 2013). This role of stabilizer is in addition to the traditional role of the ligamentum teres – carrying the blood supply to the femoral head.

Muscles around the hip joint can also provide substantial dynamic stability. Muscles which are close to the joint axis of rotation (local muscles) likely provide joint stability whereas muscles farther from the axis of rotation (global muscles) provide the joint torque. At the hip, these local muscles include the deep external rotators, iliopsoas, and gluteus medius and minimus (see Retchford et al., (2013) for an excellent review).

Sex-specific Differences in the Human Pelvis

Sex-specific differences are expressed in the overall structure of the human pelvis (Caldwell and Moloy 1933; Meindl et al. 1985; Tague 1992). The female pelvis tends to be wider and broader, with less prominent ischial spines (Kurki 2011; Meindl et al. 1985; Tague 1992). The male pelvis typically has a longer, more curved sacrum, and a narrower sub-pubic arch (between the left and right ischiopubic rami) (Caldwell and Moloy 1933; Tague 1992). While the female pelvis is wider when measured between the ischial spines (bispinous width) (Tague 1992), the biacetabular width is not significantly different between females and males across all populations (Kurki 2011). This discrepancy is partially due to the larger male femoral head (Kurki 2011) which shifts the hip joint center laterally. Whether the morphological differences between the sexes result from obstetric constraints or from differential allometric growth trajectories has been debated (Abitbol 1996; Abouheif and Fairbairn 1997; Badyaev 2002; Kurki 2011; Rosenberg 1992; Schultz 1949).

Sex-specific differences in the pelvis allow for a wider pelvic aperture in females which functions as the birth canal, facilitating the passage of large-brained neonates (Abitbol 1996; Caldwell and Moloy 1933; Kurki 2011; Lovejoy 2005; Meindl et al. 1985; Rosenberg 1992). In females, the birth canal is expanded as a result of anatomies including a wider sacrum, a wider subpubic angle, and less prominent ischial spines (Kurki 2011; Tague and Lovejoy 1986; Tague 1992). A larger birth canal becomes essential with the encephalized neonatal heads in humans (Abitbol 1996; Caldwell and Moloy 1933; Lovejoy 2005; Meindl et al. 1985; Rosenberg 1992).

When this pelvic sexual dimorphism occurred in human evolutionary history is unclear due to the paucity and fragmentary nature of fossil pelvic remains. Ardipithecus ramidus (ARA-VP-6/500), a hominin from 4.4 million years ago, exhibits synapomorphies with humans in its pelvic morphology including superior-inferiorly shortened and mediolaterally broad iliac blades (Lovejoy et al. 2009; White et al. 2009). The small cranial capacity in Ar. ramidus indicates that these pelvic morphologies are probably a result of locomotor, rather than obstetric, demands (Lovejoy et al. 2009; White et al. 2009). Later hominins such as A.L. 288-1 (Australopithecus afarensis) and Sts 14 (Au. africanus) exhibit female-specific pelvic morphologies (Berge et al. 1984; Tague and Lovejoy 1986; but see Häusler and Schmid 1995). However, it is not until the dramatic increase in brain size around 1.8 million years ago that obstetric constraints probably contributed to hominin pelvic morphology (Simpson et al. 2008).

The pelvic differences between males and females may be a result of hormonal influence on bone growth (Badyaev 2002; Huseynov et al. 2016; Tague 1989). Sex-specific hormones during growth, such as testosterone and estrogen, have been hypothesized to influence pelvic morphology (Badyaev 2002; Huseynov et al. 2016; Tague 1989). There is a greater degree of sexual dimorphism as body size increases across most mammalian species (Abouheif and Fairbairn 1997). In humans, where males are slightly larger than females, the growth trajectories between the sexes vary (Badyaev 2002; Huseynov et al. 2016). Whether this is the cause of the sex-specific pelvic morphologies in humans has yet to be determined, but recent research has suggested that female hormones at puberty influence the obstetric dimensions of the pelvis (Huseynov et al. 2016).

As reviewed, intersexual pelvic morphological differences in humans may be the result of obstetric demands, differences in growth patterns, or a combination of the two. The idea that the wide pelvis increases the locomotor costs for females has been proposed (Bramble and Lieberman 2004; Rosenberg 1992; Tague 1989; Zihlman and Brunker 1979), but has not been supported by empirical data (Dunsworth et al. 2012; Warrener et al. 2015). In one study by Leonard and Robertson (1995), it was found that when walking normally, women were actually more efficient than men. Nonetheless, kinematic differences between men and women have been noted in pelvic motions (Bruening et al. 2015) which may be a result of a wider female pelvis. We discuss the sex-specific differences of pelvic motion in human gait later in this article.

Abnormal Structure of the Human Acetabulum: Under-coverage and Over-coverage

In addition to the sex-specific variation in the human pelvis, such as widening of the female pelvis, there is also variation in the structure of the human acetabulum. This variation, when viewed through an evolutionary lens, may be a by-product of the changes in overall pelvic morphology necessary for bipedal locomotion (Hogervorst et al. 2011). While a wide range of this variability is considered normal, two structural abnormalities commonly noted today can generally be described as under-coverage and over-coverage of the acetabulum on the femur. Although these abnormal structures are thought to contribute to hip pain, the exact point at which these structures vary enough to be termed pathologic is not well established (Anderson et al. 2012; Diesel et al. 2015; Harris-Hayes and Royer 2011; Nepple et al. 2013). Under-coverage and over-coverage are clinically referred to as acetabular dysplasia and pincer femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), respectively. Interestingly, each of these occur more often in females than males (Bache, Clegg, Herron 2002; Tannast, Siebenrock, Anderson 2007). This sex-specific prevalence may be a result of the dual evolutionary challenge of bipedalism and obstetric constraints (Hogervorst et al. 2011).

Acetabular dysplasia is when the acetabulum fails to provide the normal amount of bony coverage, or stability, around the femoral head. The reported incidence of dysplasia ranges from 0.06 to 76.1 per 1000 live births, with most developed countries reporting an incidence between 1.5 and 20 per 1000 live births. (Bache, Clegg, Herron 2002; Loder and Skopelja 2011; Patel and Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care 2001; Rosendahl, Markestad, Lie 1994) Risk factors for dysplasia include breech intrauterine position, female sex, high birth weight, family history of dysplasia, firstborn status, and race (Bache, Clegg, Herron 2002; Storer and Skaggs 2006).

The degree of under-coverage exists along a continuum. The mildest forms can be asymptomatic and undetected, while moderate and severe forms can cause hip instability, subluxation, or dislocation (McWilliams et al. 2010; Storer and Skaggs 2006). The more severe forms are usually diagnosed in infancy during physical examination or ultrasonography screening. Milder forms of dysplasia, however, may not be diagnosed until insidious hip or groin pain develops in skeletally mature adults (Hickman and Peters 2001; McCarthy and Lee 2002; Nunley et al. 2011; Peters and Erickson 2006).

In the presence of dysplasia, there is less containment of the femoral head within the shallow acetabulum during weight-bearing. The poor congruency leads to increased stress which may cause a fracture of the acetabular rim and separation of rim fragments as well as labral hypertrophy and tears (Chegini, Beck, Ferguson 2009; Hickman and Peters 2001; Horii et al. 2003; Klaue, Durnin, Ganz 1991; Lane et al. 2000; Leunig et al. 2004; Mavcic et al. 2008; McCarthy and Lee 2002). In adults, the primary treatment of acetabular dysplasia is acetabular reorientation surgery, usually with the Bernese periacetabular osteotomy (PAO) (Ganz et al. 1988; Hickman and Peters 2001). The general goal of this surgical reorientation is to reduce contact stress by improving the congruency and coverage of the femoral head, and thereby delay or prevent the onset of hip osteoarthritis (OA). However, non-surgical interventions may be successful in individuals with mild dysplasia (Lewis, Khuu, Marinko 2015).

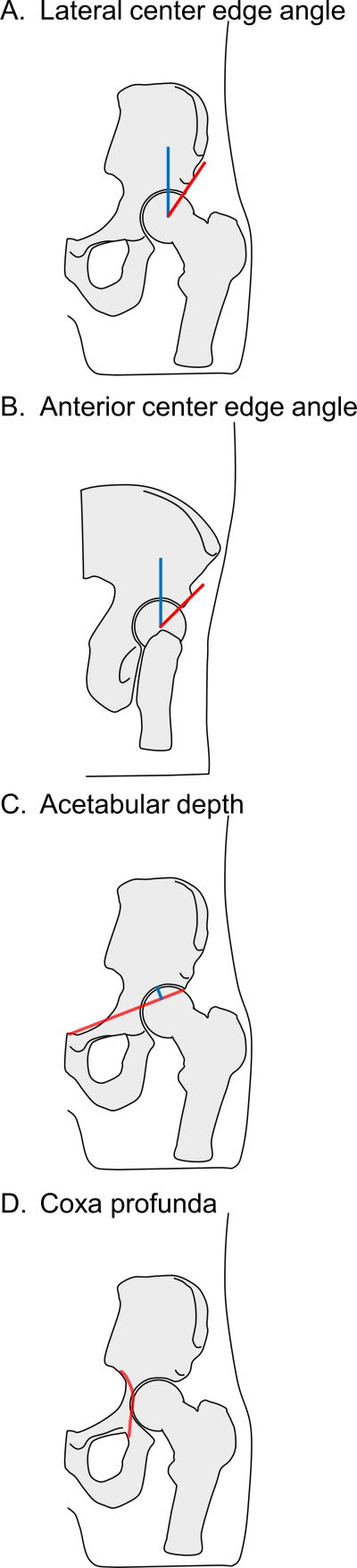

Common measures for acetabular dysplasia include the center edge angle and acetabular depth. The center edge angle is defined as the angle between a line drawn vertically from the center of the femoral head and a line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the lateral edge of the weight-bearing zone of the acetabulum (Clohisy et al. 2008). This angle is most typically measured on an anteroposterior view of the pelvis, and is called the lateral center edge angle (Figure 1A). It is also sometimes measured anteriorly on a false-profile view, and is called the anterior center edge angle (Figure 1B). In the false-profile view, the radiograph is obtained with the pelvis rotated posteriorly 25 degrees (65 degrees relative to image receptor) (Clohisy et al. 2008) to allow a less obstructed view of the acetabulum and femur. While it is agreed that a reduced center edge angle indicates dysplasia, the exact cutoff value is not well established. Cutoff values of 20 degrees, 25 degrees, and 30 degrees have all been used (Harris-Hayes and Royer 2011).

Figure 1.

Measures of the acetabulum. A. Lateral center edge angle: on an anteroposterior view of the pelvis, the angle between a line drawn vertically from the center of the femoral head (blue) and a line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the lateral edge of the weight-bearing zone of the acetabulum (red). B. Anterior center edge angle: on a false-profile view of the pelvis, the angle between a line drawn vertically from the center of the femoral head (blue) and a line drawn from the center of the femoral head to the anterior edge of the weight-bearing zone of the acetabulum (red). C. Acetabular depth: on an anteroposterior view of the pelvis, the perpendicular distance (blue line) from the deepest part of the acetabular roof to a line connecting the lateral margin of the acetabular roof to the upper corner of the pubic symphysis (red). D. Coxa profunda: on an anteroposterior view of the pelvis, when the floor of the acetabulum is medial to or touching the ilioischial line (red).

Acetabular depth is an additional measure used to diagnosis dysplasia. It is the perpendicular distance from the deepest part of the acetabular roof to a line connecting the lateral margin of the acetabular roof to the upper corner of the pubic symphysis (Lane et al. 2000; Murray 1965). (Figure 1C) An acetabular depth of less than 9 mm is considered indicative of dysplasia (Lane et al. 2000; Reijman et al. 2005).

Acetabular dysplasia has been linked with the development of hip OA (Birrell et al. 2003; Lievense et al. 2004; Nunley et al. 2011; Reijman et al. 2005). Untreated moderate and severe dysplasia can lead to early hip OA and the need for hip arthroplasty (Murphy, Ganz, Muller 1995). Even mild dysplasia more than doubles the risk of hip OA (Lane et al. 2000; McWilliams et al. 2010). However, in one study, hips with a lateral center edge angle even as low as 16 degrees, did not progress to OA by age 65 years (Murphy, Ganz, Muller 1995), indicating that the natural progression for mild dysplasia is less clear.

Acetabular over-coverage contributing to FAI has been recently recognized as an abnormal bone shape contributing to hip pain, acetabular labral tears, and chondral pathology (Ganz et al. 2003). This type of FAI called “pincer FAI” is thought to lead to impingement between the enlarged acetabular rim and the femur (Ganz et al. 2003). Whereas acetabular dysplasia is diagnosed by a smaller than normal center edge angle, pincer FAI is diagnosed when the center edge angle is greater than 40 degrees (Clohisy et al. 2011; Tannast et al. 2007). This over-coverage, which is diagnosed more often in females than males (Tannast et al. 2007), can be local or global, and can be anterior or lateral or both. In addition to the center edge angle, the relative position of the acetabulum within the pelvis has been used to diagnose pincer FAI. When the floor of the acetabulum is touching or medial to the ilioischial line (Figure 1D), this indicates coxa profunda, and is often classified as pincer FAI (Clohisy et al. 2011).

While a center edge angle greater than 40 degrees or the presence of coxa profunda are commonly thought to indicate abnormal acetabular geometry, the prevalence of pincer deformity detected in asymptomatic hips is approximately 67% (Frank et al. 2015). Additionally, multiple studies have found high prevalence of coxa profunda in asymptomatic individuals, and little or no correspondence with other measures of pincer FAI (Anderson et al. 2012; Diesel et al. 2015; Nepple et al. 2013). Together, these studies indicate that coxa profunda itself should not be used as an indicator of pincer FAI, especially in females (Diesel et al. 2015; Nepple et al. 2013). Furthermore, the increased prevalence of coxa profunda in females (Diesel et al. 2015; Nepple et al. 2013) may be an adaptation to the wider pelvis which accommodates obstetric demands. From a biomechanical perspective, the deep acetabulum moves the hip joint center more medially. This change reduces the moment arm for the center of mass, and therefore reduces the force required of the hip abductors (Hogervorst et al. 2011), a potential energetic advantage. Thus, the deep hip socket may be a beneficial variation instead of a pathology.

While there is strong evidence supporting the link between hip OA and acetabular dysplasia, the link with pincer FAI is questionable. Initial studies reported a potential increased risk (Chung et al. 2010); however, a more recent large cohort study did not find an increased risk (Agricola et al. 2013).

Motions of the Human Pelvis

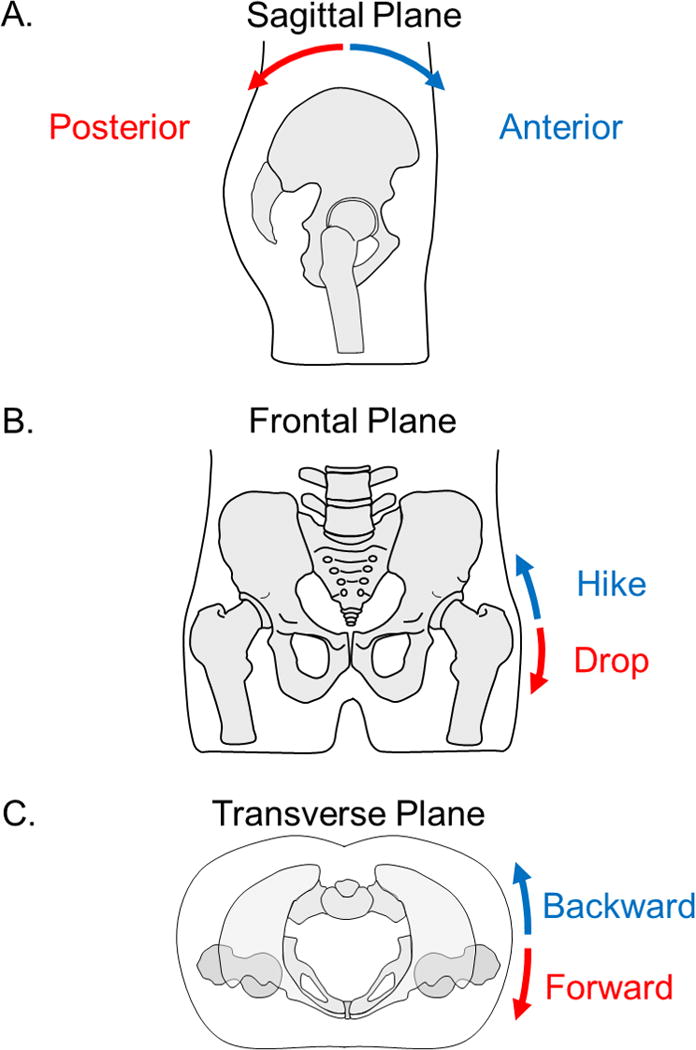

Generally, motions of the pelvis are described as rotations about one of three cardinal axes, each of which creates motion in one of the planes (Cappozzo et al. 2005). The terminology for these rotations is not consistent across different scientific and clinical fields, and therefore, will be explained in depth here. Rotation about a mediolateral axis produces motion within the sagittal plane, and is often referred to as anterior or posterior tilt or rotation (Figure 2A). With anterior pelvic tilt, the anterior superior iliac spines (ASIS) each move anteriorly and inferiorly while the posterior superior iliac spines (PSIS) each move superiorly (Levangie and Norkin 2011; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970; Neumann 2010a). Conversely, posterior pelvic tilt occurs when the ASIS move posteriorly and superiorly while the PSIS move inferiorly.

Figure 2.

Motions of the pelvis. A. Pelvic motion in the sagittal plane described as posterior and anterior tilt. B. Pelvic motion in the frontal plane described as pelvic drop and pelvic hike. C. Pelvic motion in the transverse plane described as forward rotation and backward rotation. The motions in the frontal and transverse planes are typically described by the motion of the side of the pelvis opposite the stance leg (right leg in this case).

Rotation about an anteroposterior axis creates motion within the frontal or coronal plane (Figure 2B). This motion occurs when one side of the pelvis moves lower as the other side moves higher, and is often referred to as pelvic drop or hike; or in some fields, pelvic obliquity or list. Typically, this occurs while weight-bearing on a single lower extremity and is described by the motion of the contralateral side of the pelvis (Levangie and Norkin 2011; Neumann 2010a). For example, when standing on the right lower extremity, pelvic drop is when the left side of the pelvis is lowered. Conversely, when the left side of the pelvis is raised, this is considered pelvic hike. Sometimes this is referred to as contralateral pelvic drop or hike in order to convey the sense that the description refers to the side away from the stance lower extremity. It is important to understand, however, that the motion is controlled by the stance hip abductor muscles (Neumann 2010b).

Rotation about a vertical axis produces motion in the transverse or horizontal plane (Figure 2C). In some fields, this is referred to as forward and backward rotation (Levangie and Norkin 2011), or similarly as anterior and posterior rotation. Again, the naming convention is based on the motion of the side contralateral to the hip controlling the motion. For example, when standing on the right lower extremity, forward rotation is when the contralateral side is moving forward or anteriorly. Backward rotation is when the contralateral side is moving backward or posteriorly. Others refer to these motions as internal and external rotation (Neumann 2010a), and is named similarly to the motions of the lower extremity segments. Just as right femoral internal rotation is counter-clockwise rotation of the femur when viewed from a superior perspective, internal rotation of the pelvis during right stance is counter-clockwise rotation of the pelvis or backward rotation (Neumann 2010a).

These same terms for pelvic motion (hike / drop, tilt and rotation) are also used to describe the position of the pelvis in certain postures or activities. In standing with weight equally distributed between both lower extremities, the pelvis is normally level with the left and the right ASIS being at the same height (Michaud, Gard, Childress 2000), indicating neither pelvic hike nor drop or no obliquity. In the sagittal plane, “neutral” pelvis has sometimes been defined as the ASIS being in the same vertical plane as the symphysis pubis (Kendall, McCreary, Provance 1993; Levangie and Norkin 2011). This definition is often extended to indicate that a line drawn between the ASIS and PSIS is horizontal, indicating no tilt. Use of these bony landmarks allow the clinician to easily palpate and measure pelvic tilt. Typically, people stand in 11 to 13 degrees of anterior pelvic tilt (Crowell et al. 1994; Levine and Whittle 1996). One should be cautioned that this pelvic tilt is not the same as the radiological measure of “pelvic tilt” commonly noted in literature focusing on the spine. In spine literature, the pelvic tilt measurement is the angle between a vertical line passing through the center of the bicoxofemoral axis and a line drawn between the axis and the middle of the superior endplate of S1 (Ames et al. 2013; Garbossa et al. 2014; Roussouly et al. 2005). Using this measure, pelvic tilt in standing is typically between 12 and 15 degrees (Ames et al. 2013; Roussouly et al. 2005). Despite the range being similar to the anterior pelvic tilt measure using ASIS as a reference, in this radiological measure of pelvic tilt, increasing numbers indicate increasing posterior pelvic tilt.

Pelvic motion during human gait

During human gait, the pelvis has motions about all three axes. The magnitude of these motions is partially dependent on walking speed, with larger motions occurring at faster walking speeds (Bejek et al. 2006; Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970; Stokes, Andersson, Forssberg 1989). Here, we present data from our laboratory collected on 44 healthy individuals (22 females (age: 22.9 ± 2.8 years (mean ± standard deviation (SD)), height: 1.63 ± 0.07 m, mass: 61.1 ± 8.5 kg) and 22 males (age: 24.9 ± 6.3 years, height: 1.78 ± 0.09 m, mass: 75.2 ± 14.2 kg) while walking on an instrumented force treadmill (Bertec Corporation, Columbus, OH). Data were collected and processed using standard motion capture methodology which has been previously published (Ogamba et al. 2016). Individuals were tested walking at two walking speeds: self-selected (~1.27 m/s) and prescribed (1.25 m/s). Using a prescribed walking speed where all individuals walk at the same speed allows for comparison of parameters which may be affected by walking speed.

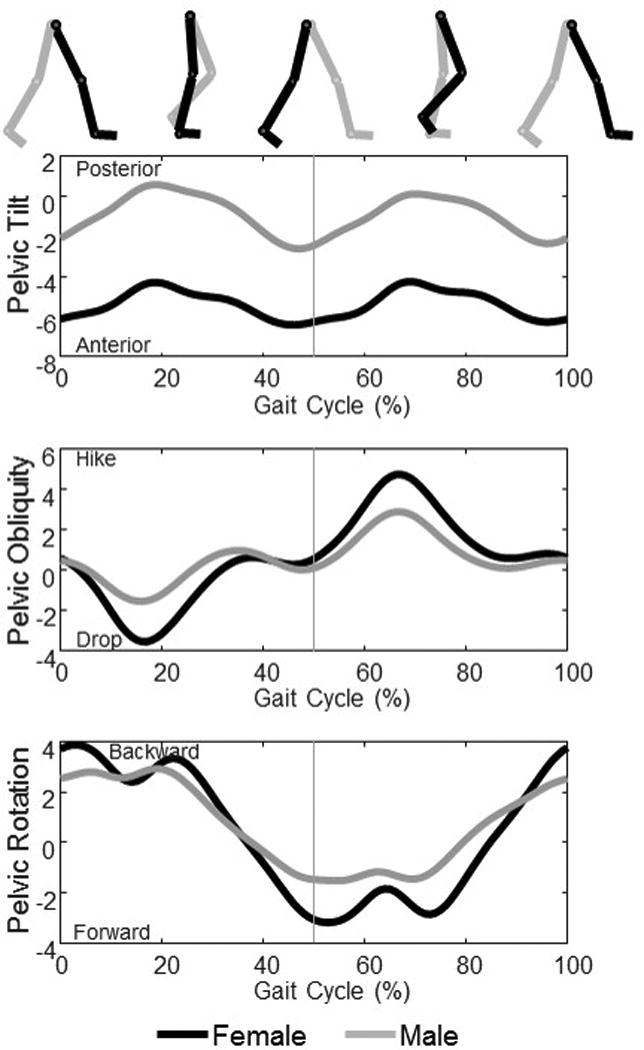

In the sagittal plane, the pelvis is typically maintained in anterior pelvic tilt throughout gait (O’Neill et al. 2015), and completes two full cycles of a sinusoidal wave for each gait cycle (Figure 3). Following initial contact, the pelvis tilts posteriorly for less than 20% of the gait cycle. It then begins to tilt anteriorly again until the contralateral foot contacts the ground at approximately 50% of the gait cycle. The cycle then repeats itself, tilting posteriorly, and anteriorly again. The total excursion of this movement is relatively small, approximately 2 to 5 degrees (Bruening et al. 2015; Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997; Kadaba, Ramakrishnan, Wootten 1990; Murray, Drought, Kory 1964; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002). In our data, the mean total excursion was 4.3 degrees with an SD of 1.1 degrees and range of 2.6 to 7.3 degrees at preferred walking speed.

Figure 3.

Sex-specific differences in pelvic motion during gait. These data were the mean from 22 healthy females and 22 healthy males (walking at a controlled speed (1.25 m/s) on an instrumented treadmill. Data are presented as ipsilateral initial foot contact (heel strike) to ipsilateral initial foot contact. The vertical gray line indicates contralateral initial foot contact. Differences in pelvic position and motion in all three planes can be observed. Females walk in more anterior pelvic tilt, and have greater excursion in pelvic obliquity, and slightly greater pelvic rotation while males maintain the pelvis closer to neutral tilt, and have less pelvic obliquity and rotation excursion.

In the frontal plane, the pelvis completes one cycle of motion throughout each gait cycle (Figure 3). At initial contact, the pelvis is approximately neutral with left and right ASIS being level (or 0 degrees of obliquity). Following contact, the pelvis drops for less than 20% of the gait cycle, after which it begins to raise again. When the other foot contacts the ground, the pelvis is approximately neutral again. If viewed relative to the initial foot, the pelvis would be described as continuing to hike. However, in some fields, it is customary to switch the perspective to the now stance leg, and say that the pelvis is dropping again (Levangie and Norkin 2011). The total excursion for this motion is approximately 6 to 11 degrees at preferred walking speed (Bruening et al. 2015; Chumanov, Wall-Scheffler, Heiderscheit 2008; Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997; Kadaba, Ramakrishnan, Wootten 1990; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002; Stokes, Andersson, Forssberg 1989). In our data, the range was 1.9 to 12.5 degrees with a mean total excursion of 7.4 degrees and SD of 2.5 degrees walking at a preferred speed.

In the transverse plane, the pelvis completes one cycle of motion as well (Figure 3). At initial contact of the right foot, the pelvis is in backward rotation with the left ASIS posterior to the right ASIS. This backward rotation continues briefly during the double support phase, and then changes to forward rotation of the pelvis. The forward rotation continues until just after contralateral heel strike (around 50%). From the view point of the swing leg, the pelvis is then rotating backward again until just after ipsilateral heel strike. Again, it is customary in some fields to switch the perspective and say that the pelvis is rotating forward on the left leg (Levangie and Norkin 2011). The reported magnitude of the excursion of the pelvis in the transverse plane is as low as 3 degrees (Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997), and as high as 14 degrees (Bruening et al. 2015) with most somewhere in between (Kadaba, Ramakrishnan, Wootten 1990; Kerrigan et al. 2001; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002; Stokes, Andersson, Forssberg 1989). Similarly, the range in our data was from 4.0 to 16.8 with a mean and SD of 9.5 ± 2.9 at preferred walking speed.

Theoretically, these motions of the pelvis during human gait help to decrease the movement of the center of mass in the vertical and horizontal direction (Neumann 2010a). In the vertical direction, the center of mass moves in a sinusoidal curve which reaches a maximum during each single leg stance and a minimum during each double support period when both feet are on the ground, resulting in two complete cycles per gait cycle (Neumann 2010a). In contrast, the sinusoidal movement in the horizontal direction completes one cycle, shifting to the right during right stance and to the left during left stance (Neumann 2010a). Saunders and colleagues (1953) described six “determinants of gait” – motions of the pelvis and lower extremities which were thought to minimize the motion of the center of mass and thus be energetically economical. Two of these determinants were specifically about pelvic rotations during gait. The first determinant was the rotation of the pelvis in the transverse plane. For a given step length, this rotation of the pelvis would reduce the magnitude of the drop in the center of mass which occurs during double support. The second determinant was the pelvic motion in the frontal plane. The pelvic drop during single leg stance lowers the maximum height of the pelvis and trunk, and thus lowers the center of mass (Stokes, Andersson, Forssberg 1989).

The notion that pelvic and lower extremity movements “minimize” the excursion of the center of mass has come under increasing scrutiny (Della Croce et al. 2001; Kerrigan et al. 2001; Lin, Gfoehler, Pandy 2014). Pelvic rotation in the transverse plane provides a small, but notable, reduction in center of mass excursion (Della Croce et al. 2001; Kerrigan et al. 2001; Lin, Gfoehler, Pandy 2014). Pelvis obliquity has been found to contribute to the mediolateral excursion of the center of mass, but very little to the reduction of the vertical excursion (Lin, Gfoehler, Pandy 2014). When taken to the extreme of eliminating vertical motion of the center of mass, Gordon and colleagues (2009) clearly demonstrate that metabolic cost and mechanical work in the lower extremity increase as a result. However, it is still appreciated, especially when analyzing pathological gait, that normal pelvic motion plays a role in reducing exaggerated movements of the center of mass. Furthermore, the importance of the normal movement of the pelvis during gait has been highlighted in recent work. Restrictions of pelvic motion, as can occur in robotic assistive devices, lead to compensation in upper and lower extremity kinematics (Mun, Guo, Yu 2016; Veneman et al. 2008).

Sex-specific differences in pelvic motion in human gait

Just as there are sex-specific differences in the shape of the pelvis, there are sex-specific differences in pelvic position and motion during gait (Bruening et al. 2015; Cho, Park, Kwon 2004; Chumanov, Wall-Scheffler, Heiderscheit 2008; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002). On average, females maintain the pelvis in a position of slight anterior pelvic tilt (approximately 4 degrees in our data) while males maintain the pelvis in a position closer to neutral (Cho, Park, Kwon 2004) but differences in the motion of the pelvis in the sagittal plane during walking are not typically noted (Bruening et al. 2015; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002).

In the frontal plane, females have more excursion of the pelvis while males have less (Bruening et al. 2015; Chumanov, Wall-Scheffler, Heiderscheit 2008; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002) (Figure 3). The mean difference between males and females in our study was 1.9 degrees (95% Confidence Interval (CI) of 0.9 to 2.9 degrees) which was significant (p < 0.001) as determined by an Independent-Samples T-Test in SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). The increased frontal plane motion may contribute to the smaller vertical displacement of the COM during gait as noted in females (Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002), further facilitating economical gait; however, another study did not find differences in center of mass motion (Bruening et al. 2015).

Movement of the pelvis in the transverse plane is usually greater in females and lesser in males (Bruening et al. 2015; Chumanov, Wall-Scheffler, Heiderscheit 2008; Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997). Similarly, we found a mean difference of 2 degrees with a 95% CI of 0.6 to 3.4 degrees (p = 0.029) when walking at the same speed. Conversely, Murray et al. (1970) reported slightly less transverse plane rotation in females and more in males; however, this finding may be due to the faster walking speed and longer stride length noted in the males in the comparative study (Murray, Drought, Kory 1964).

These differences in pelvic motion may contribute to or result from other differences between how males and females walk. For example, walking speed can affect the magnitude of pelvic motion (Bejek et al. 2006; Crosbie, Vachalathiti, Smith 1997; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970; Stokes, Andersson, Forssberg 1989). In our participants, there was not a difference in preferred walking speed between our males and females. The mean and SD of the preferred walking speed was 1.26 ± 0.17 m/s in males and 1.28 ± 0.16 m/s in females (p = 0.735). However, some studies have reported slower walking speeds in females and faster speeds in males (Cho, Park, Kwon 2004; Frimenko, Goodyear, Bruening 2015; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970), but no difference in others (Bruening et al. 2015; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002). When detected, differences in walking speed may be due to differences in height as the effect is often lost after normalizing for height (Cho, Park, Kwon 2004; Frimenko, Goodyear, Bruening 2015) or including height as a co-variate (Cho, Park, Kwon 2004).

Additionally, females tend to walk with a faster cadence while males walk with a slower cadence at their self-selected speed (Boyer, Beaupre, Andriacchi 2008; Frimenko, Goodyear, Bruening 2015; Kerrigan et al. 1998; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002). Stride length has also been found to be different between the sexes with females taking shorter steps while males take longer ones (Cho, Park, Kwon 2004; Frimenko, Goodyear, Bruening 2015; Murray, Kory, Sepic 1970; Smith, Lelas, Kerrigan 2002). Again, this difference may be due to height differences and not pelvic structure as stride length was actually longer after normalization (Kerrigan et al. 1998).

Altered gait in the presence of abnormal acetabular structure

In individuals with altered acetabular anatomy, slight differences in pelvic and hip kinematics during walking have been noted. Patients with acetabular dysplasia have altered pelvic and hip kinematics during walking. In individuals with dysplasia, Romano et al. (1996) reported significantly increased pelvic drop and forward displacement during stance on their affected side. This was accompanied by decreased transverse plane pelvic excursion compared to individuals without dysplasia. At the hip, decreased peak hip extension (Jacobsen et al. 2013; Romano et al. 1996; Skalshøi et al. 2015) have also been reported. While no studies to date have looked exclusively at pincer FAI separate from its femoral counterpart (cam FAI), minimal changes in gait have been reported in individuals with FAI. For example, Hunt et al. (2013) found that individuals with FAI walked slower than healthy controls and had lower peak hip extension, adduction and internal rotation. When walking at similar speeds, Diamond et al., (2016) found only a small reduction in the sagittal plane hip excursion in individuals with FAI compared to healthy controls. It is thought, however, that gait does not challenge the hip sufficiently to detect changes with FAI (Diamond et al. 2016).

Conclusions

In summary, the structure of the human pelvis reflects the transition to habitual bipedality. The pelvic motions during gait serve to optimize the movement of the center of mass, producing smooth and energetically efficient locomotion. Normal variation in the structure of the pelvis and its motion during gait exist between sexes. It remains unclear if these sex-specific differences during gait are related to specific pelvic structure or to differences in body size and height. Specific variations in the structure of the acetabulum may contribute to hip pain and pathology. These variations are noted more often in females than males. In the presence of abnormal acetabular structure, especially with acetabular dysplasia, the pelvic motions also may be altered. While it is suggested that coxa profunda may be energetically beneficial, it is not well established why these variations occur or how the variation affects gait.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases of the National Institutes of Health; Grant number: K23 AR063235

References

- Abitbol MM. The shapes of the female pelvis. contributing factors. J Reprod Med. 1996;41(4):242–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abouheif E, Fairbairn DJ. A comparative analysis of allometry for sexual size dimorphism: Assessing rensch’s rule. Am Nat. 1997:540–62. [Google Scholar]

- Agricola R, Heijboer M, Roze R, Reijman M, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Verhaar J, Weinans H, Waarsing J. Pincer deformity does not lead to osteoarthritis of the hip whereas acetabular dysplasia does: Acetabular coverage and development of osteoarthritis in a nationwide prospective cohort study (CHECK) Osteoarthr Cartil. 2013;21(10):1514–21. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2013.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ames CP, Blondel B, Scheer JK, Schwab FJ, Le Huec JC, Massicotte EM, Patel AA, Traynelis VC, Kim HJ, Shaffrey CI, et al. Cervical radiographical alignment: Comprehensive assessment techniques and potential importance in cervical myelopathy. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2013;38(22 Suppl 1):S149–60. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182a7f449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson LA, Kapron AL, Aoki SK, Peters CL. Coxa profunda: Is the deep acetabulum overcovered? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470(12):3375–82. doi: 10.1007/s11999-012-2509-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bache CE, Clegg J, Herron M. Risk factors for developmental dysplasia of the hip: Ultrasonographic findings in the neonatal period. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2002;11(3):212–8. doi: 10.1097/00009957-200207000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Badyaev AV. Growing apart: An ontogenetic perspective on the evolution of sexual size dimorphism. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2002;17(8):369–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bejek Z, Paroczai R, Illyes A, Kiss RM. The influence of walking speed on gait parameters in healthy people and in patients with osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2006;14(7):612–22. doi: 10.1007/s00167-005-0005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berge C. How did the australopithecines walk? A biomechanical study of the hip and thigh of australopithecus afarensis. J Hum Evol. 1994;26(4):259–73. [Google Scholar]

- Berge C, Orban-Segebarth R, Schmid P. Obstetrical interpretation of the australopithecine pelvic cavity. J Hum Evol. 1984;13(7):573–87. [Google Scholar]

- Birrell F, Silman A, Croft P, Cooper C, Hosie G, Macfarlane G PCR Hip Study Group. Syndrome of symptomatic adult acetabular dysplasia (SAAD syndrome) Ann Rheum Dis. 2003;62(4):356–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.62.4.356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyer KA, Beaupre GS, Andriacchi TP. Gender differences exist in the hip joint moments of healthy older walkers. J Biomech. 2008;41(16):3360–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2008.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramble DM, Lieberman DE. Endurance running and the evolution of homo. Nature. 2004;432(7015):345–52. doi: 10.1038/nature03052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooke R. The sacro-iliac joint. J Anat. 1924;58(Pt 4):299–305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruening DA, Frimenko RE, Goodyear CD, Bowden DR, Fullenkamp AM. Sex differences in whole body gait kinematics at preferred speeds. Gait Posture. 2015;41(2):540–5. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell W, Moloy HC. Anatomical variations in the female pelvis and their effect in labor with a suggested classification. Obstet Gynecol. 1933;26(4):479–505. [Google Scholar]

- Cappozzo A, Della Croce U, Leardini A, Chiari L. Human movement analysis using stereophotogrammetry: Part 1: Theoretical background. Gait Posture. 2005;21(2):186–96. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chegini S, Beck M, Ferguson SJ. The effects of impingement and dysplasia on stress distributions in the hip joint during sitting and walking: A finite element analysis. J Orthop Res. 2009;27(2):195–201. doi: 10.1002/jor.20747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S, Park J, Kwon O. Gender differences in three dimensional gait analysis data from 98 healthy korean adults. Clin Biomech. 2004;19(2):145–52. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2003.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chumanov ES, Wall-Scheffler C, Heiderscheit BC. Gender differences in walking and running on level and inclined surfaces. Clin Biomech (Bristol, Avon) 2008;23(10):1260–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2008.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung CY, Park MS, Lee KM, Lee SH, Kim TK, Kim KW, Park JH, Lee JJ. Hip osteoarthritis and risk factors in elderly korean population. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2010;18(3):312–6. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2009.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clohisy JC, Dobson MA, Robison JF, Warth LC, Zheng J, Liu SS, Yehyawi TM, Callaghan JJ. Radiographic structural abnormalities associated with premature, natural hip-joint failure. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(Suppl 2):3–9. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clohisy JC, Carlisle JC, Beaule PE, Kim YJ, Trousdale RT, Sierra RJ, Leunig M, Schoenecker PL, Millis MB. A systematic approach to the plain radiographic evaluation of the young adult hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(Suppl 4):47–66. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.H.00756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosbie J, Vachalathiti R, Smith R. Age, gender and speed effects on spinal kinematics during walking. Gait Posture. 1997;5(1):13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Crowell RD, Cummings GS, Walker JR, Tillman LJ. Intratester and intertester reliability and validity of measures of innominate bone inclination. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1994;20(2):88–97. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1994.20.2.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Della Croce U, Riley PO, Lelas JL, Kerrigan DC. A refined view of the determinants of gait. Gait Posture. 2001;14(2):79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0966-6362(01)00128-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond LE, Wrigley TV, Bennell KL, Hinman RS, O’Donnell J, Hodges PW. Hip joint biomechanics during gait in people with and without symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Gait Posture. 2016;43:198–203. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diesel CV, Ribeiro TA, Coussirat C, Scheidt RB, Macedo CA, Galia CR. Coxa profunda in the diagnosis of pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement and its prevalence in asymptomatic subjects. Bone Joint J. 2015;97-B(4):478–83. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.97B4.34577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Domb BG, Martin DE, Botser IB. Risk factors for ligamentum teres tears. Arthroscopy. 2013;29(1):64–73. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2012.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunsworth HM, Warrener AG, Deacon T, Ellison PT, Pontzer H. Metabolic hypothesis for human altriciality. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109(38):15212–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205282109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frank JM, Harris JD, Erickson BJ, Slikker W, Bush-Joseph CA, Salata MJ, Nho SJ. Prevalence of femoroacetabular impingement imaging findings in asymptomatic volunteers: A systematic review. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(6):1199–204. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2014.11.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frimenko R, Goodyear C, Bruening D. Interactions of sex and aging on spatiotemporal metrics in non-pathological gait: A descriptive meta-analysis. Physiotherapy. 2015;101(3):266–72. doi: 10.1016/j.physio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Klaue K, Vinh TS, Mast JW. A new periacetabular osteotomy for the treatment of hip dysplasias. technique and preliminary results. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;(232):26–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganz R, Parvizi J, Beck M, Leunig M, Notzli H, Siebenrock KA. Femoroacetabular impingement: A cause for osteoarthritis of the hip. Clin Orthop. 2003;(417):112–20. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000096804.78689.c2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbossa D, Pejrona M, Damilano M, Sansone V, Ducati A, Berjano P. Pelvic parameters and global spine balance for spine degenerative disease: The importance of containing for the well being of content. Eur Spine J. 2014;23(6):616–27. doi: 10.1007/s00586-014-3558-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon KE, Ferris DP, Kuo AD. Metabolic and mechanical energy costs of reducing vertical center of mass movement during gait. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(1):136–44. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2008.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hagen R. Pelvic girdle relaxation from an orthopaedic point of view. Acta Orthop Scand. 1974;45(1–4):550–63. doi: 10.3109/17453677408989178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris-Hayes M, Royer NK. Relationship of acetabular dysplasia and femoroacetabular impingement to hip osteoarthritis: A focused review. Pm&r. 2011;3(11):1055, 1067.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2011.08.533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Häusler M, Schmid P. Comparison of the pelves of Sts 14 and AL288-1: implications for birth and sexual dimorphism in australopithecines. J Hum Evol. 1995;29(4):363–83. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman JM, Peters CL. Hip pain in the young adult: Diagnosis and treatment of disorders of the acetabular labrum and acetabular dysplasia. Am J Orthop. 2001;30(6):459–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hlavacek M. The influence of the acetabular labrum seal, intact articular superficial zone and synovial fluid thixotropy on squeeze-film lubrication of a spherical synovial joint. J Biomech. 2002;35(0021-9290; 10):1325–35. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9290(02)00172-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogervorst T, Bouma H, de Boer SF, de Vos J. Human hip impingement morphology: An evolutionary explanation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2011;93(6):769–76. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.93B6.25149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horii M, Kubo T, Inoue S, Kim WC. Coverage of the femoral head by the acetabular labrum in dysplastic hips: Quantitative analysis with radial MR imaging. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003;74(3):287–92. doi: 10.1080/00016470310014201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt KD. The evolution of human bipedality: Ecology and functional morphology. J Hum Evol. 1994;26(3):183–202. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt MA, Gunether JR, Gilbart MK. Kinematic and kinetic differences during walking in patients with and without symptomatic femoroacetabular impingement. Clin Biomech. 2013;28(5):519–23. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiomech.2013.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huseynov A, Zollikofer CP, Coudyzer W, Gascho D, Kellenberger C, Hinzpeter R, de León MS. Developmental evidence for obstetric adaptation of the human female pelvis. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2016;113(19):5227–32. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1517085113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen JS, Nielsen DB, Sørensen H, Søballe K, Mechlenburg I. Changes in walking and running in patients with hip dysplasia. Acta Orthop. 2013;84(3):265–70. doi: 10.3109/17453674.2013.792030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kadaba MP, Ramakrishnan HK, Wootten ME. Measurement of lower extremity kinematics during level walking. J Orthop Res. 1990;8(0736-0266; 3):383–92. doi: 10.1002/jor.1100080310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendall FP, McCreary EK, Provance PG. Muscles testing and function. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Riley PO, Lelas JL, Della Croce U. Quantification of pelvic rotation as a determinant of gait. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82(2):217–20. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.18063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerrigan DC, Todd MK, Della Croce U, Lipsitz LA, Collins JJ. Biomechanical gait alterations independent of speed in the healthy elderly: Evidence for specific limiting impairments. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79(3):317–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90013-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivlan BR, Richard Clemente F, Martin RL, Martin HD. Function of the ligamentum teres during multi-planar movement of the hip joint. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(7):1664–8. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2168-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klaue K, Durnin CW, Ganz R. The acetabular rim syndrome. A clinical presentation of dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1991;73(3):423–9. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.73B3.1670443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurki HK. Pelvic dimorphism in relation to body size and body size dimorphism in humans. J Hum Evol. 2011;61(6):631–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lane NE, Lin P, Christiansen L, Gore LR, Williams EN, Hochberg MC, Nevitt MC. Association of mild acetabular dysplasia with an increased risk of incident hip osteoarthritis in elderly white women: The study of osteoporotic fractures. Arthritis Rheum. 2000;43(2):400–4. doi: 10.1002/1529-0131(200002)43:2<400::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonard WR, Robertson ML. Energetic efficiency of human bipedality. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1995;97(3):335–8. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330970308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leunig M, Podeszwa D, Beck M, Werlen S, Ganz R. Magnetic resonance arthrography of labral disorders in hips with dysplasia and impingement. Clin Orthop. 2004;(418):74–80. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200401000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levangie PK, Norkin CC. Joint structure and function: A comprehensive analysis. FA Davis; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Levine D, Whittle MW. The effects of pelvic movement on lumbar lordosis in the standing position. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1996;24(3):130–5. doi: 10.2519/jospt.1996.24.3.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis CL, Khuu A, Marinko LN. Postural correction reduces hip pain in adult with acetabular dysplasia: A case report. Man Ther. 2015;20(3):508–12. doi: 10.1016/j.math.2015.01.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lievense AM, Bierma-Zeinstra SM, Verhagen AP, Verhaar JA, Koes BW. Influence of hip dysplasia on the development of osteoarthritis of the hip. Ann Rheum Dis. 2004;63(6):621–6. doi: 10.1136/ard.2003.009860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin Y, Gfoehler M, Pandy MG. Quantitative evaluation of the major determinants of human gait. J Biomech. 2014;47(6):1324–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2014.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loder RT, Skopelja EN. The epidemiology and demographics of hip dysplasia. ISRN Orthopedics. 2011 doi: 10.5402/2011/238607. 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy CO, Meindl RS, Pryzbeck TR, Mensforth RP. Chronological metamorphosis of the auricular surface of the ilium: A new method for the determination of adult skeletal age at death. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1985;68(1):15–28. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330680103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy CO, Suwa G, Spurlock L, Asfaw B, White TD. The pelvis and femur of ardipithecus ramidus: The emergence of upright walking. Science. 2009;326(5949):71–71e6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovejoy CO. The natural history of human gait and posture. part 2. hip and thigh. Gait Posture. 2005;21(1):113–24. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2004.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin RL, Kivlan BR, Clemente FR. A cadaveric model for ligamentum teres function: A pilot study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2013;21(7):1689–93. doi: 10.1007/s00167-012-2262-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavcic B, Iglic A, Kralj-Iglic V, Brand RA, Vengust R. Cumulative hip contact stress predicts osteoarthritis in DDH. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(4):884–91. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0145-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy JC, Lee JA. Acetabular dysplasia: A paradigm of arthroscopic examination of chondral injuries. Clin Orthop. 2002;(405):122–8. doi: 10.1097/00003086-200212000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams DF, Doherty SA, Jenkins WD, Maciewicz RA, Muir KR, Zhang W, Doherty M. Mild acetabular dysplasia and risk of osteoarthritis of the hip: A case-control study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69(10):1774–8. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.127076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meindl RS, Lovejoy CO, Mensforth RP, Carlos LD. Accuracy and direction of error in the sexing of the skeleton: Implications for paleodemography. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1985;68(1):79–85. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330680108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merle C, Grammatopoulos G, Waldstein W, Pegg E, Pandit H, Aldinger PR, Gill HS, Murray DW. Comparison of native anatomy with recommended safe component orientation in total hip arthroplasty for primary osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):e172. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.01014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud SB, Gard SA, Childress DS. A preliminary investigation of pelvic obliquity patterns during gait in persons with transtibial and transfemoral amputation. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 2000;37(1):1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mun K, Guo Z, Yu H. Restriction of pelvic lateral and rotational motions alters lower limb kinematics and muscle activation pattern during over-ground walking. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2016:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11517-016-1450-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy SB, Ganz R, Muller ME. The prognosis in untreated dysplasia of the hip. A study of radiographic factors that predict the outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(7):985–9. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199507000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray DW. The definition and measurement of acetabular orientation. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1993;75(2):228–32. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.75B2.8444942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MP, Kory RC, Sepic SB. Walking patterns of normal women. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1970;51(11):637–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray MP, Drought AB, Kory RC. Walking patterns of normal men. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1964;46:335–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RO. The aetiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38(455):810–24. doi: 10.1259/0007-1285-38-455-810. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nepple JJ, Lehmann CL, Ross JR, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Coxa profunda is not a useful radiographic parameter for diagnosing pincer-type femoroacetabular impingement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(5):417–23. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.K.01664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the musculoskeletal system: Foundations for rehabilitation. 2. St. Louis, MO: Elsevier; 2010a. [Google Scholar]

- Neumann DA. Kinesiology of the hip: A focus on muscular actions. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2010b;40(2):82–94. doi: 10.2519/jospt.2010.3025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nunley RM, Prather H, Hunt D, Schoenecker PL, Clohisy JC. Clinical presentation of symptomatic acetabular dysplasia in skeletally mature patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(Suppl 2):17–21. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.J.01735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogamba MI, Loverro KL, Laudicina NM, Gill SV, Lewis CL. Changes in gait with anteriorly added mass: A pregnancy simulation study. J Appl Biomech. 2016 doi: 10.1123/jab.2015-0178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill MC, Lee L, Demes B, Thompson NE, Larson SG, Stern JT, Umberger BR. Three-dimensional kinematics of the pelvis and hind limbs in chimpanzee (pan troglodytes) and human bipedal walking. J Hum Evol. 2015;86:32–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jhevol.2015.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel H and Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care. Preventive health care, 2001 update: Screening and management of developmental dysplasia of the hip in newborns. Cmaj. 2001;164(12):1669–77. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perreira AC, Hunter JC, Laird T, Jamali AA. Multilevel measurement of acetabular version using 3-D CT-generated models: Implications for hip preservation surgery. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research®. 2011;469(2):552–61. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1567-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters CL, Erickson J. The etiology and treatment of hip pain in the young adult. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 4):20–6. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen W, Petersen F, Tillmann B. Structure and vascularization of the acetabular labrum with regard to the pathogenesis and healing of labral lesions. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2003;123(0936-8051; 6):283–8. doi: 10.1007/s00402-003-0527-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reijman M, Hazes JM, Pols HA, Koes BW, Bierma-Zeinstra SM. Acetabular dysplasia predicts incident osteoarthritis of the hip: The rotterdam study. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52(3):787–93. doi: 10.1002/art.20886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Retchford TH, Crossley KM, Grimaldi A, Kemp JL, Cowan SM. Can local muscles augment stability in the hip? A narrative literature review. J Musculoskelet Neuronal Interact. 2013;13(1):1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds D, Lucas J, Klaue K. Retroversion of the acetabulum. A cause of hip pain. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1999;81(0301-620; 2):281–8. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.81b2.8291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robinson JT. Early hominid posture and locomotion. University of Chicago Press; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Romano CL, Frigo C, Randelli G, Pedotti A. Analysis of the gait of adults who had residua of congenital dysplasia of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(10):1468–79. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199610000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg KR. The evolution of modern human childbirth. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1992;35(S15):89–124. [Google Scholar]

- Rosendahl K, Markestad T, Lie RT. Ultrasound screening for developmental dysplasia of the hip in the neonate: The effect on treatment rate and prevalence of late cases. Pediatrics. 1994;94(1):47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussouly P, Gollogly S, Berthonnaud E, Dimnet J. Classification of the normal variation in the sagittal alignment of the human lumbar spine and pelvis in the standing position. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30(3):346–53. doi: 10.1097/01.brs.0000152379.54463.65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruff C. Primate locomotion. Springer; 1998. Evolution of the hominid hip; 449 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Inman VT, Eberhart HD. The major determinants in normal and pathological gait. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1953;35-A(3):543–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz AH. Sex differences in the pelves of primates. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1949;7(3):401–24. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330070307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson SW, Quade J, Levin NE, Butler R, Dupont-Nivet G, Everett M, Semaw S. A female Homo erectus pelvis from Gona, Ethiopia. Science. 2008;322(5904):1089–92. doi: 10.1126/science.1163592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalshøi O, Iversen CH, Nielsen DB, Jacobsen J, Mechlenburg I, Søballe K, Sørensen H. Walking patterns and hip contact forces in patients with hip dysplasia. Gait Posture. 2015;42(4):529–33. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2015.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LK, Lelas JL, Kerrigan DC. Gender differences in pelvic motions and center of mass displacement during walking: Stereotypes quantified. J Womens Health Gend Based. 2002;11(5):453–8. doi: 10.1089/15246090260137626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stern JT, Jr, Susman RL. The locomotor anatomy of australopithecus afarensis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1983;60(3):279–317. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330600302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stokes V, Andersson C, Forssberg H. Rotational and translational movement features of the pelvis and thorax during adult human locomotion. J Biomech. 1989;22(1):43–50. doi: 10.1016/0021-9290(89)90183-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Storer SK, Skaggs DL. Developmental dysplasia of the hip. Am Fam Physician. 2006;74(8):1310–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tague RG. Sexual dimorphism in the human bony pelvis, with a consideration of the neandertal pelvis from kebara cave, israel. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1992;88(1):1–21. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330880102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tague RG. Variation in pelvic size between males and females. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1989;80(1):59–71. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.1330800108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tague RG, Lovejoy CO. The obstetric pelvis of AL 288-1 (lucy) J Hum Evol. 1986;15(4):237–55. [Google Scholar]

- Tan V, Seldes RM, Katz MA, Freedhand AM, Klimkiewicz JJ, Fitzgerald RH., Jr Contribution of acetabular labrum to articulating surface area and femoral head coverage in adult hip joints: An anatomic study in cadavera. Am J Orthop. 2001;30(1078-4519; 11):809–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannast M, Siebenrock KA, Anderson SE. Femoroacetabular impingement: Radiographic diagnosis--what the radiologist should know. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2007;188(6):1540–52. doi: 10.2214/AJR.06.0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tannast M, Kubiak-Langer M, Langlotz F, Puls M, Murphy SB, Siebenrock KA. Noninvasive three-dimensional assessment of femoroacetabular impingement. J Orthop Res. 2007;25(1):122–31. doi: 10.1002/jor.20309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Veneman JF, Menger J, van Asseldonk EH, van der Helm Frans CT, van der Kooij H. Fixating the pelvis in the horizontal plane affects gait characteristics. Gait Posture. 2008;28(1):157–63. doi: 10.1016/j.gaitpost.2007.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward CV. Interpreting the posture and locomotion of australopithecus afarensis: Where do we stand? Am J Phys Anthropol. 2002;119(S35):185–215. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.10185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warrener AG, Lewton KL, Pontzer H, Lieberman DE. A wider pelvis does not increase locomotor cost in humans, with implications for the evolution of childbirth. PloS One. 2015;10(3):e0118903. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Werner CM, Ramseier LE, Ruckstuhl T, Stromberg J, Copeland CE, Turen CH, Rufibach K, Bouaicha S. Normal values of wiberg’s lateral center-edge angle and lequesne’s acetabular index-a coxometric update. Skeletal Radiol. 2012;41(10):1273–8. doi: 10.1007/s00256-012-1420-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White TD, Black MT, Folkens PA. Human osteology. Academic press; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- White TD, Asfaw B, Beyene Y, Haile-Selassie Y, Lovejoy CO, Suwa G, WoldeGabriel G. Ardipithecus ramidus and the paleobiology of early hominids. Science. 2009;326(5949):64–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zihlman AL, Brunker L. Hominid bipedalism: Then and now. Yb.Physical Anthropol. 1979;22:132–62. [Google Scholar]