Abstract

Despite the recent rollout of Isoniazid Preventive Therapy (IPT) to prevent TB in people living with HIV in South Africa, adherence and completion rates are low. To explore barriers to IPT completion in rural KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa, we conducted individual semi-structured interviews among 30 HIV patients who had completed or defaulted IPT. Interview transcripts were analyzed according to the framework method of qualitative analysis. Facilitators of IPT completion included knowledge of TB and IPT, accepting one’s HIV diagnosis, viewing IPT as similar to antiretroviral therapy, having social support in the community and the clinic, trust in the healthcare system, and desire for health preservation. Barriers included misunderstanding of IPT’s preventive role in the absence of symptoms, inefficient health service delivery, ineffective communication with healthcare workers, financial burden of transport to clinic and lost wages, and competing priorities. HIV-related stigma was not identified as a significant barrier to IPT completion, and participants felt confident in their ability to manage stigma, for example by pretending their medications were for unrelated conditions. Completers were more comfortable communicating with health care workers than were defaulters. Efforts to facilitate successful IPT completion must include appropriate counseling and education for individual patients and addressing inefficiencies within the health care system in order to minimize patients’ financial and logistical burden. These patient-level and structural changes are necessary for IPT to successfully reduce TB incidence in this resource-limited setting.

Keywords: Isoniazid preventive therapy, tuberculosis, HIV/AIDS, adherence, qualitative methods

Introduction

South Africa has one of the greatest HIV and tuberculosis (TB) burdens worldwide (World Health Organization, 2007). Daily isoniazid for >6 months safely decreases active TB risk in HIV-positive patients by 60% (Akolo, Adetifa, Shepperd, & Volmink, 2010; Grant et al., 2010; van Halsema et al., 2010). South African guidelines recommend isoniazid preventive therapy (IPT) for all HIV-positive patients without active TB symptoms, regardless of CD4 count, antiretroviral therapy (ART) status or prior TB history (Launch of 2013 Isoniazid Preventive Therapy Guidelines, 2013), yet completion rates are low (Chehab, Vilakazi-Nhlapo, Vranken, Peters, & Klausner, 2012).

Previously reported barriers to IPT adherence and completion in resource-limited settings include HIV-related stigma (Makanjuola, Taddese, & Booth, 2014; Rowe et al., 2005), recent HIV diagnosis (Oni et al., 2012), male gender, poor understanding of IPT (Gust et al., 2011), transportation and medication expenses, unstable housing, and unemployment (Codecasa et al., 2013; Rutherford et al., 2012). Concurrent ART may predict IPT success (Durovni et al., 2010; Rutherford et al., 2012).

Previous data on IPT adherence in South Africa were collected in the pre-ART era, within monitored clinical trials, or urban settings. Our qualitative investigation uniquely explores factors influencing IPT completion or default among HIV-positive patients in rural South Africa who initiated IPT during routine HIV care in the post-ART era.

Methods

Study setting

Msinga subdistrict’s rural Zulu population largely survives on government welfare grants due to 80% unemployment; only half have access to electricity (KwaZulu-Natal uMzinyathi District Profile, 2012). TB incidence (>1100/100,000) and HIV antenatal prevalence (31.1%) are high (The national antenatal sentinel HIV and Syphilis prevalence survey, 2010). A government district hospital and 15 satellite primary health care clinics (PHCs) provide free ART and IPT to HIV-positive patients.

Participant selection

Eligible participants were HIV-positive, ≥18 years, and had initiated IPT at the district hospital clinic or one of four select PHCs. We recruited male and female “completers” (collected IPT for ≥6 consecutive months and self-reported ≥80% adherence) and “defaulters” (collected IPT for <6 months) through purposive sampling. Potential participants were identified by clinic IPT registers and approached in waiting rooms or by telephone. Those willing to participate were privately screened for inclusion criteria and completer/defaulter status.

Qualitative data collection

In a private setting, a Zulu-speaking researcher (NM) obtained verbal consent and conducted one-on-one, hour-long semi-structured interviews exploring knowledge and attitudes towards TB, IPT, and HIV, and reasons for initiating IPT and completing/defaulting treatment. Two pilot interviews were conducted to refine question prompts and train the study team.

Yale University’s Human Investigation Committee and the South African Medical Association Research Ethics Committee approved the protocol.

Data analysis

Transcribed audio recordings were professionally translated from Zulu to English. Data were analyzed with Atlas.ti qualitative analysis software using a framework approach (Pope, Ziebland, & Mays, 2000). A starting code list was applied to a subset of interviews and code definitions refined iteratively. The lead author coded all interviews, and all authors coded select interviews. Coding discrepancies were resolved through group discussion. Codes were organized in a working analytic framework based on previously-developed theoretical models of IPT and TB treatment adherence (Makanjuola et al., 2014; Munro et al., 2007) then merged into sub-themes and themes illustrating facilitators and barriers to IPT completion.

Results

Twelve male and 18 female participants were interviewed (Table 1). Seventeen completed IPT, and 13 defaulted. Several distinct themes emerged (Table 2).

Table 1.

Participant characteristics.

| Completers (n = 17) | Defaulters (n = 13) | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 7 | 5 |

| Female | 10 | 8 |

| Median Age (IQR) | 39 (32–43) | 37 (28–39) |

| Clinic | ||

| District Hospital HIV Clinic | 3 | 4 |

| Primary Health Clinic | 14 | 9 |

| TB History | ||

| Prior TB | 4 | 6 |

| No Prior TB | 13 | 7 |

| ART Status | ||

| On ART | 15 | 12 |

| Not on ART | 2 | 1 |

Table 2.

Quotes illustrating facilitators of and barriers to IPT adherence.

|

FACILITATORS OF

IPT ADHERENCE AND COMPLETION

| |

| Fear of TB and belief in IPT’s benefit | *“If there are no symptoms, they start you [on IPT] … I understood that it was going to minimize chances of TB infection because you can get TB everywhere … especially HIV+ people.” – Female, age 24 (C) |

| *“I work with cement and before taking IPT I could not tolerate dust. I felt like coughing … and was scared of getting TB so IPT helped me a lot, I no longer am short of breath.” Male, age 50 (C) | |

| Acceptance of HIV diagnosis | *“When I first find out that I was [HIV+] … I did not accept it, I kept on running [away from the clinic]. But last year … I accepted it because of the way I was sick …. They checked for TB and they could not detect it. I was then given the TB prevention tablets. So when I began [ART] and TB prevention tablets, I took them together.” – Male, age 40 (C) |

| Similarity of IPT and ART | *“I would take [IPT for life] because it is … the same as ARVs I am able to take them for life.” – Female, age 30 (C) |

| Social Support | *“I was worried that I could contract TB and … give it to my baby. So I took [IPT].” – Female, age 24 (C) |

| *“Patients at line in the clinic] encourage each other, especially those who are about to be started on [IPT], that it is important to take.” Female, age 30 (C) | |

| *“[My friend] asked why I did not go [to the clinic] and I told her that I did not have a transport fare. She went and got it from hers. On my return I ensured that I raised and returned her money.” Female, age 30 (C) | |

| Strategies for coping with HIV-related stigma | *“I don’t care if anyone knows about my status, most people are sick now [and] if you go to clinics and hospitals you can see that most people are infected. So I don’t care anymore, I’m not scared.” – Female, age 43 (C) |

| *“I can take [the IPT] and keep it my secret … When I am travelling for example with the church, I would take my tablet and put it in a different container so that it will look as if I have a headache.” – Female, age 48 (C) | |

| *“I stopped IPT because of the problem I had with my eyes not because I was scared of anyone … They know that I am sick because I collect tablets monthly … although they don’t know which tablets.” – Female, age 40 (D) | |

| Health Preservation | *“My health [is important], I wish I could live longer for my children’s sake. ” – Female, age 40 (D) |

| *“It’s all about my life. One cannot buy life, you only live once.” – Male, age 50 (C) | |

| Trust in health care system | *“I had sore feet when I started using [IPT]. … I decided to report and not to keep quiet. [They prescribed Vitamin B6 which] helped me a great deal because after taking them I never had sore feet again” – Male, age 37 (C) |

| *“I am sure most people do not know IPT even if they have been told about it at the facility, they simply take [it] and go.” – Male, age 39 (C) | |

|

| |

| BARRIERS TO IPT ADHERENCE AND COMPLETION | |

|

| |

| Absence of symptoms | *“After taking [IPT] the cough subsided. I felt … better [so] I decided to stop taking them.” – Female, age 30 (D) |

| Inefficient health care delivery | *“I will be [at the clinic] by 3 [AM] … because of the queue … I take my IPT while waiting … at 7 [AM]. The problem is I won’t have my porridge because I’m at the clinic, not at home, but I make sure that I take it.” – Male, age 39 (C) |

| *“My [pills ran out] while I was in Johannesburg. I could not go to the clinic there to ask for more pills because last year I went [there] but they told me not … to come to their clinic again [without a transfer letter].” – Female, age 34 (D) | |

| Cost of accessing health care | *“Sometimes the appointment clashes with a job so you end up not having money … They do not consider that you cannot stay home doing nothing waiting to collect treatment. You have to eat, you have children, and there are many needs that you have to provide for with money, it is tough.” – Male, age 38 (D) |

| Lack of effective communication with clinic staff | *“They did not tell me [how long to take IPT for … The second [visit] they gave me [ART but not IPT] so I thought I had completed the course. That is where the disturbance was … They did not say anything..” – Female, age 23 (D) |

| *“[The second month] I asked them about IPT … I waited for a long time until the nurse said it might be out of stock because many people have been taking it …. [The third month] they also did not mention anything … I was scared [to ask], I told myself that they were going to give me if they had them. [I was scared] that they will think I’m asking a lot of questions.” – Female, age 26 (D) | |

| Prioritizing ART over IPT | *“I was overwhelmed. My baby was very ill at that time … I could not sleep well at night. I said I better stop taking [IPT] and continue [ART] which is taken for a lifetime because I am now responsible [for these babies].” – Female, age 30 (D) |

| *“After I collected my ARV’s I forgot to collect IPT, and I remembered when I was on my way out of the clinic. When I went back the line was too many people.” – Male, age 40 (D) | |

Notes: IPT = Isoniazid Preventive Therapy, TB = Tuberculosis, C = Completer, D = Defaulter.

Facilitators of successful IPT completion included favorable (though not necessarily correct) knowledge of TB’s risk/IPT’s benefit, acceptance of one’s HIV diagnosis, viewing IPT and ART as similar, social support, coping with stigma, and desire for health preservation. Barriers included misunderstanding of IPT’s preventive role, inefficient health service delivery, expense of accessing health care including opportunity cost of lost wages, ineffective communication with healthcare providers, and prioritizing ART over IPT.

Facilitators of IPT success

Knowledge and beliefs about TB and IPT

Many participants feared TB. One-third had TB previously, and all knew someone with TB.

Most participants knew that IPT prevents TB. Some knew IPT is taken when asymptomatic. Others erroneously hoped it would alleviate present symptoms, prompting some to adhere but deterring others who were asymptomatic and doubted IPT’s value.

Accepting one’s HIV diagnosis

When discussing IPT, many participants first described their HIV history. Accepting their HIV diagnosis and beginning ART facilitated deciding to begin IPT.

Similarity of IPT and ART

IPT was viewed as similar to ART. Participants already accustomed to daily ART regarded one additional daily pill as trivial. All but 3 (2 completers, 1 defaulter) took IPT concurrently with ART.

Social support

Family, friends and coworkers of both completers and defaulters lent money for transport to clinic, collected treatment refills, provided childcare, and covered for absent employees. They also provided information about HIV, TB and IPT, encouragement to seek treatment, and reminders to take pills. Fear of transmitting TB to loved ones motivated adherence for both groups.

Many completers befriended fellow patients in clinic waiting rooms and exchanged information about medications and side effects. No defaulters described such interactions.

Coping with stigma

Participants acknowledged community stigma against HIV, but not TB. No participants named HIV-related stigma as a barrier to IPT. Many participants felt no need to hide their medications, believing only other HIV patients would connect IPT with HIV. Completers and defaulters did not differ in describing stigma.

Health preservation

All interviewees were motivated to remain alive and healthy and willing to take medication despite barriers.

Trust in healthcare system

Both completers and defaulters trusted providers and followed instructions carefully. However, more completers than defaulters trusted clinic staff to respond supportively to their concerns.

Barriers to IPT success

Expense of accessing health care

Monthly transport to clinics was often expensive, and many participants had to forego income to attend appointments. Economic difficulties underlay most treatment interruptions.

Inefficient health care delivery

Participants endured long queues to collect medication, often skipping meals and taking medications on an empty stomach. Most clinics did not fully integrate TB and HIV services, dispensing IPT and ART in separate queues. Half of participants described service lapses including medication stock-outs and lost test results. Participants also faced difficulty obtaining refills from outside clinics while traveling.

Lack of effective patient-provider communication

Some patients followed providers’ directions despite incomplete understanding of IPT’s purpose or intended duration, causing treatment interruptions when patients assumed accidentally omitted IPT refills were purposeful. Defaulters avoided reporting side effects, questioning missing medications, or requesting to re-start IPT after treatment lapses for fear of nurses’ scolding. In contrast, completers also experienced side effects and drug stock-outs, but felt comfortable speaking up.

Prioritizing ART over IPT

Facing obstacles, patients were more likely to default IPT, but not ART. All but one defaulter continued to take ART even when interrupting IPT.

Discussion

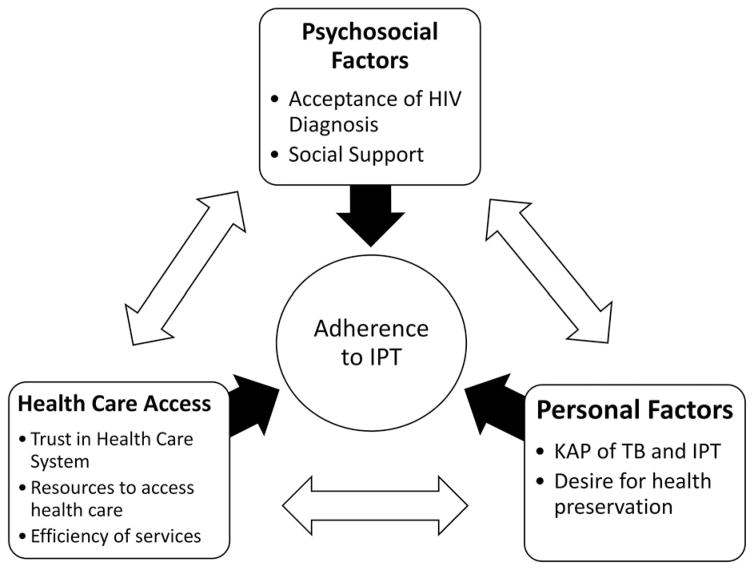

This is the first study to qualitatively examine barriers to IPT completion in programmatic health care settings in rural South Africa in the post-ART era. Consistent with existing literature, expense of clinic visits and inefficient health care delivery were major barriers. Our unique findings include the importance of accepting one’s HIV diagnosis for IPT success, absence of HIV-related stigma as a barrier to successful IPT completion, and prioritization of ART over IPT. Completers and defaulters differed in how they experienced social support and comfort with clinic staff in handling setbacks. Figure 1 illustrates major themes of health determinants relevant to our findings, and their reciprocal influence. These findings inform strategies to facilitate successful IPT completion at the provider, facility and policy levels (Table 3).

Figure 1.

Facilitators and barriers to IPT adherence among HIV patients accessing HIV care in rural KZN, South Africa. IPT = Isoniazid preventive therapy, KAP = Knowledge, attitudes, practices, TB = Tuberculosis. In order to adhere to IPT, patients must have accepted their HIV diagnosis and be in a social situation in which they either feel comfortable disclosing their status or feel that they can manage their social situation to keep their status hidden. Patients must trust that the health care system will not only provide effective medical care but also will empower them to communicate effectively with providers so that any questions or problems such as side effects can be addressed. They must have the ability and resources (transport fare, a job that allows time off) to physically access care including getting to clinic appointments and taking pills consistently. They must believe that TB is a risk even if they are asymptomatic and that IPT will reduce that risk without adverse effects, and they must make health a priority. These concepts influence each other; for example, trust in health system is also necessary for HIV testing and diagnosis; presence of social support can mitigate economic burdens; knowledge and beliefs about IPT come from both social networks and within the health system; sometimes the desire for health preservation is outweighed by immediate lack of resources to survive.

Table 3.

Recommendations for increasing access to IPT among HIV patients accessing care at clinics in rural South Africa.

| Level of Action | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| Provider | In addition to a thorough review of the

benefits and risks of IPT, education and pre-counseling of patients

initiating IPT should specifically include the following information,

presented according to the patient’s level of health literacy.

|

| Health Facility |

|

| Policy |

|

Notes: Barriers to successful IPT completion can be minimized, and facilitators enhanced, by specific actions at the provider, facility, and policy levels.

Participants viewed IPT through the lens of their HIV diagnosis and treatment and many had trouble separating the two. Often, the major barrier to IPT had been entering HIV care. Once on lifelong ART, IPT’s marginal cost was low. Other studies have identified recent HIV diagnosis as a barrier (Oni et al., 2012) and concurrent ART as a facilitator (Durovni et al., 2010; Rutherford et al., 2012) to IPT completion. Newly diagnosed patients or those not yet on ART may require extra support before beginning IPT.

HIV-related stigma did not emerge as a specific barrier to IPT, and participants strategized successfully to avoid consequences of stigma while accessing HIV care and IPT. Stigma may remain a significant barrier among those not yet engaged in care.

While pill burden may discourage IPT adherence elsewhere (Mindachew, Deribew, Tessema, & Biadgilign, 2011), our study participants generally accepted one extra tablet. However, ART took priority over IPT, and all 12 IPT defaulters continued ART without interruption. Selective adherence to ART over active TB treatment has also been described (Daftary, Padayatchi, & O’Donnell, 2014). Integrating ART and IPT delivery may decrease the incremental burden of IPT, facilitating longer IPT duration according to recently updated guidelines (National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines, 2014).

Incomplete knowledge is sometimes a barrier to IPT completion (Ngamvithayapong, Uthaivoravit, Yanai, Akarasewi, & Sawanpanyalert, 1997). Misunderstanding the prophylaxis concept can demotivate asymptomatic patients (Gust et al., 2011). Poor understanding of IPT’s intended duration was only a barrier when clinic staff erred. IPT counseling should be tailored to the patient’s education level (Lester et al., 2010; Mindachew et al., 2011), perhaps using public holidays to help patients mark projected treatment end dates, and emphasizing that preventive medications are taken when asymptomatic.

Expense and inconvenience of collecting medications often led to IPT interruptions. Long queues, drug stock-outs, and lack of service integration are unfortunately commonplace in resource-limited settings (Munro et al., 2007), particularly PHCs (Szakacs et al., 2006), and require attention on an institution and policy level. Fear of speaking up to clinic staff often hindered problem-solving. Providers should empower patients to ask questions and report problems. Increasing the interval between clinic visits for stable patients and facilitating transfer of care between clinics may ease these burdens.

Despite barriers, motivation to preserve health was universal. Financial, logistic and emotional social support helped mitigate treatment barriers.

Our findings may not be generalizable to other settings, or to HIV-positive patients not yet in care. However, they are particularly relevant to rural South African patients already accessing HIV care and eligible for IPT.

Conclusion

For HIV-positive patients already engaged in care, IPT success depends on accepting one’s HIV diagnosis, social support, trust in healthcare system and desire for health preservation. Addressing economic and logistical difficulties, inefficient health care delivery and suboptimal patient-provider communication may facilitate patients’ completion of IPT and further this strategy’s impact on reducing TB incidence in resource-limited settings.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the wonderful staff at Philanjalo Care Centre, Church of Scotland Hospital ARV clinic, and Ethembeni, Noyibazi, Cwaka and Gateway clinics.

Funding

The project described was supported by the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS [award number P30MH062294] from the National Institute of Mental Health and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. Karen Jacobson was a Doris Duke International Clinical Research Fellow. SS received funding from NIAID (K23 AI089260).

Appendix. Semi-structured qualitative interview format

I’m going to ask you a series of questions now. These questions are “open-ended”, meaning that you can answer with as many words as you would like. I would like this to feel like a conversation in which I am getting to know you and your opinions on these topics.

To ask Study Participant:

Age:

Gender:

Clinic:

IPT Start Date: Month: _________ Year: ___________

Date of last IPT pick-up: Month: ____________ Year: _____________

Date of Interview:

Tell me about your health – how has your health been in the last year?

-

Tell me about why you decided to start taking Isoniazid Preventive Therapy, or IPT?

When did you first hear about IPT?

What did you understand about how IPT would help you?

Tell me about the first time you came to the clinic to get IPT. Start from the beginning of the day and tell me what you did and what you were feeling.

Think back to before you took IPT. Describe a typical day for you then.

-

Now think back to the time when you were taking IPT, describe what was then a typical day for you.

How did taking IPT change your normal daily routine?

-

Do you take antiretroviral therapy, or ART?

Tell me about why you decided to start taking ART?

Were you taking ART when you were taking IPT?

If yes: Tell me about what it was like to take IPT in addition to the ART?

If no: Have you ever had to take any medication every day for a long period of time? What was the medication? Were you taking it at the same time as IPT? What was that like?

-

Tell me about how the IPT medication made you feel.

Did you feel any different when you were taking it?

Did you experience any side effects from IPT? Please describe them.

Tell me about your monthly visits to the clinic and pharmacy. How did you get there? How did it change your normal daily routine?

-

Was there a person or people at the clinic who you generally met with to discuss IPT? Describe this person to me.

What did you learn about IPT from this person?

What did this person tell you about potential side effects from IPT?

Think about a time that you told someone you were taking IPT. Who was this person? How did you tell them and what was their reaction?

If you went to the pharmacy to get your IPT meds and you saw a friend there, what would you do? What would you say?

Imagine a friend or family member told you that their doctor suggested they take IPT. What would you tell them about the process?

Now imagine this same friend came to tell you, a few weeks later, that they decided to stop IPT – what would you say?

What advice would you give this friend to help make it easier for them to take IPT every day for 6 months?

What are the three most important things in your life right now? (If health not mentioned, ask: How important is your health, compared to these things?)

What was the biggest challenge in taking IPT?

What was your greatest fear about taking IPT?

What have you learned from taking IPT?

In South Africa, doctors and scientists have found that taking IPT for longer than 6 months may possibly improve the protection against TB. If in the future your doctor offered you IPT for 36 months (3 years), would you be willing to take it? Would you be willing to take it every day lifelong?

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the Center for Interdisciplinary Research on AIDS, the National Institute of Mental health, or the National Institutes of Health.

References

- Akolo C, Adetifa I, Shepperd S, Volmink J. Treatment of latent tuberculosis infection in HIV infected persons. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2010;(1):CD000171. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000171.pub3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chehab JC, Vilakazi-Nhlapo K, Vranken P, Peters A, Klausner JD. Survey of isoniazid preventive therapy in South Africa, 2011. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2012;16(7):903–907. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.11.0722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codecasa LR, Murgia N, Ferrarese M, Delmastro M, Repossi AC, Casali L, … Raviglione MC. Isoniazid preventive treatment: Predictors of adverse events and treatment completion. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2013;17(7):903–908. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A, Padayatchi N, O’Donnell M. Preferential adherence to antiretroviral therapy over tuberculosis treatment: A qualitative study of drug-resistant TB/ HIV co-infected patients in South Africa. Global Public Health. 2014;9(9):1107–1116. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.934266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durovni B, Cavalcante SC, Saraceni V, Vellozo V, Israel G, King BS, … Golub JE. The implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV clinics: The experience from the TB/HIV in Rio (THRio) study. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 5):S49–S56. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000391022.95412.a6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant AD, Mngadi KT, van Halsema CL, Luttig MM, Fielding KL, Churchyard GJ. Adverse events with isoniazid preventive therapy: Experience from a large trial. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 5):S29–S36. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000391019.10661.66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gust DA, Mosimaneotsile B, Mathebula U, Chingapane B, Gaul Z, Pals SL, Samandari T. Risk factors for non-adherence and loss to follow-up in a three-year clinical trial in Botswana. PLoS One. 2011;6(4):e18435. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0018435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Halsema CL, Fielding KL, Chihota VN, Russell EC, Lewis JJ, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Tuberculosis outcomes and drug susceptibility in individuals exposed to isoniazid preventive therapy in a high HIV prevalence setting. AIDS. 2010;24(7):1051–1055. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833849df. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- KwaZulu-Natal uMzinyathi District Profile. KwaZulu-Natal South Africa: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Launch of 2013 Isoniazid Preventive Therapy Guidelines; Paper presented at the 6th South African AIDS Conference; Durban, South Africa. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lester R, Hamilton R, Charalambous S, Dwadwa T, Chandler C, Churchyard GJ, Grant AD. Barriers to implementation of isoniazid preventive therapy in HIV clinics: A qualitative study. AIDS. 2010;24(Suppl 5):S45–S48. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000391021.18284.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makanjuola T, Taddese HB, Booth A. Factors associated with adherence to treatment with isoniazid for the prevention of tuberculosis amongst people living with HIV/AIDS: A systematic review of qualitative data. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e87166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0087166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mindachew M, Deribew A, Tessema F, Biadgilign S. Predictors of adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy among HIV positive adults in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:213. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-916. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro SA, Lewin SA, Smith HJ, Engel ME, Fretheim A, Volmink J. Patient adherence to tuberculosis treatment: A systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Medicine. 2007;4(7):e238. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0040238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Tuberculosis Management Guidelines. National tuberculosis management guidelines. Pretoria: Department of Health, South Africa; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ngamvithayapong J, Uthaivoravit W, Yanai H, Akarasewi P, Sawanpanyalert P. Adherence to tuberculosis preventive therapy among HIV-infected persons in chiang Rai, Thailand. AIDS. 1997;11(1):107–112. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199701000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oni T, Tsekela R, Kwaza B, Manjezi L, Bangani N, Wilkinson KA, … Wilkinson RJ. A recent HIV diagnosis is associated with non-completion of Isoniazid preventive therapy in an HIV-infected cohort in Cape Town. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52489. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope C, Ziebland S, Mays N. Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320(7227):114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe KA, Makhubele B, Hargreaves JR, Porter JD, Hausler HP, Pronyk PM. Adherence to TB preventive therapy for HIV-positive patients in rural South Africa: Implications for antiretroviral delivery in resource-poor settings? The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease. 2005;9(3):263–269. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutherford ME, Ruslami R, Maharani W, Yulita I, Lovell S, Van Crevel R, … Hill PC. Adherence to isoniazid preventive therapy in Indonesian children: A quantitative and qualitative investigation. BMC Research Notes. 2012;5:7. doi: 10.1186/1756-0500-5-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szakacs TA, Wilson D, Cameron DW, Clark M, Kocheleff P, Muller FJ, McCarthy AE. Adherence with isoniazid for prevention of tuberculosis among HIV-infected adults in South Africa. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:1009. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The national antenatal sentinel HIV and Syphilis prevalence survey, South Africa. Pretoria: National Department of Health; 2010. Retrieved from http://www.gov.za/sites/www.gov.za/files/hiv_aids_survey_0.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis report 2014. Geneva: Author; 2007. (Report No. WHO/HTM/TB/2014.08) Retrieved from http://www.who.int/tb/publications/2014/en/ [Google Scholar]