Abstract

Purpose

We elicited patient experiences from clinical trial simulations to aid in future trial development and to improve patient recruitment and retention.

Patients and methods

Two simulations of draft Phase II and Phase III anifrolumab studies for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)/lupus nephritis (LN) were performed involving African-American patients from Grady Hospital, an indigent care hospital in Atlanta, GA, USA, and white patients from Altoona Arthritis and Osteoporosis Center in Altoona, PA, USA. The clinical trial simulation included an informed consent procedure, a mock screening visit, a mock dosing visit, and a debriefing period for patients and staff. Patients and staff were interviewed to obtain sentiments and perceptions related to the simulated visits.

Results

The Atlanta study involved 6 African-American patients (5 female) aged 27–60 years with moderate to severe SLE/LN. The Altoona study involved 12 white females aged 32–75 years with mild to moderate SLE/LN. Patient experiences had an impact on four patient-centric care domains: 1) information, communication, and education; 2) responsiveness to needs; 3) access to care; and 4) coordination of care; and continuity and transition. Patients in both studies desired background material, knowledgeable staff, family and friend support, personal results, comfortable settings, shorter wait times, and greater scheduling flexibility. Compared with the Altoona study patients, Atlanta study patients reported greater preferences for information from the Internet, need for strong community and online support, difficulties in discussing SLE, emphasis on transportation and child care help during the visits, and concerns related to financial matters; and they placed greater importance on time commitment, understanding of potential personal benefit, trust, and confidentiality of patient data as factors for participation. Using these results, we present recommendations to improve study procedures to increase retention, recruitment, and compliance for clinical trials.

Conclusion

Insights from these two studies can be applied to the development and implementation of future clinical trials to improve patient recruitment, retention, compliance, and advocacy.

Keywords: systemic lupus erythematosus, lupus nephritis, clinical trial simulation, patient recruitment, patient retention

Introduction

Lack of patient involvement and engagement in clinical trials is a major issue that results in low recruitment and retention.1–3 As a consequence, 45% of clinical trials are unable to recruit their target sample sizes.1 Furthermore, dropout rates of 30% have been reported for some clinical trials.3

Important factors that affect patient recruitment and retention for clinical trials are socioeconomic status and race.4–6 Patients with household incomes <$50,000 have 32% lower odds of participating in a clinical trial compared with higher-income patients.4 Although African-Americans represent 12% of the U.S. population, they make up only 5% of clinical trial participants.5 In addition, patients from racial minority groups have higher dropout rates in clinical trials compared with white patients.5,7

This underrepresentation of African-Americans is particularly relevant for systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) clinical trials.6,8,9 African-Americans represent a substantial percentage of patients with SLE, with a prevalence of SLE in the United States of 112–119 per 100,000 for African-American women compared with 33–48 per 100,000 for white women.8,9 However, only 64.9% of African-Americans are willing to participate in a clinical trial for SLE compared with 84.3% of whites.6 Furthermore, in the only successful recent trial in SLE, the percentage of African-American patients was no more than 14.8% in any of the individual treatment arms.10 This Phase IIb trial evaluated anifrolumab, a fully human, immunoglobulin G1 κ monoclonal antibody that binds to and neutralizes receptors of all type I interferons and is in clinical development for the treatment of SLE and lupus nephritis (LN).10 In this trial, 12%–30% of the patients in each treatment arm discontinued treatment, including 3%–13% who withdrew consent.10

Understanding elements of clinical trial procedures that contribute to diminished recruitment and retention of patients is important, particularly when the afflicted population is from a minority group. These patients need sufficient representation in clinical trials so that researchers and patients can better understand the efficacy and safety of drugs in this population and results can be generalized to relevant patient groups.

To identify factors for improving clinical study protocols and study conduct, we obtained experiences from two simulations of draft Phase II and Phase III anifrolumab studies in which patients went through mock trial visits. One study involved African-American patients from an indigent care hospital in Atlanta, GA, USA, and the other study involved lower-middle-class white patients from a hospital in Altoona, PA, USA. Because this is a novel approach for understanding patient sentiments, we also present lessons learned from the development and implementation of trial simulations in the hope that these lessons will help to inform future efforts.

Materials and methods

Site feasibility

Two clinical trial simulations involving a mock trial environment were performed at separate clinical sites experienced with the SLE clinical trial process. One study site was at Grady Hospital, run by an Emory University School of Medicine investigator and associated staff (Atlanta study). Grady Hospital is a public hospital located in Atlanta, GA, with on site X-ray, electrocardiogram, clinical laboratory, and infusion facilities. The hospital serves a large number of low-income patients, many of whom are uninsured or underinsured, and the majority of whom are African-American. This site, which has been involved in >25 lupus clinical trials and other research studies, houses a large lupus clinic with >600 patients. Clinical research staff are dedicated and experienced in research involving this population, but the significant socioeconomic burdens of its patients are often a challenge.

The second site used was the Altoona Arthritis and Osteoporosis Center (Altoona study), a private health care practice in Altoona, PA, with on site magnetic resonance imaging, X-ray, dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, and a clinical laboratory. This rheumatology facility has >10,000 registered patients, with a catchment area of up to 150 miles. The population that this facility serves has a median household income that is 68% of the national average, with 16% holding a bachelor’s degree or greater compared with 33% nationwide. This center has completed >1,000 clinical studies (34 SLE trials) for different commercial sponsors and clinical research organizations (CROs) and has dedicated, experienced study teams for clinical trials.

Simulation procedure

The clinical trial simulations were led by Deloitte (London, UK) on behalf of AstraZeneca. The clinical trial simulation study involved four phases: site feasibility assessment, patient recruitment, simulation of two visits of a clinical trial, and a debrief session to gain more insight into what was observed. For both studies, selected patients were directly contacted in person to participate, with no patients declining.

For the Altoona study, recruited patients had mostly mild and stable SLE, whereas for the Atlanta study, recruited patients met at least most of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the Phase I and II trials for anifrolumab.11,12 Recruitment at both sites was nonbiased. During recruitment, patients were identified by site and provided with the simulation introduction letter, simulation participation agreement forms, and mock informed consent form. A booklet explaining the study was also given to patients to facilitate understanding of the study. For Atlanta study patients, this booklet was received at recruitment and patients had 2–3 days to review it. In the Altoona study, patients received this booklet at the mock screenings and could review it between visits.

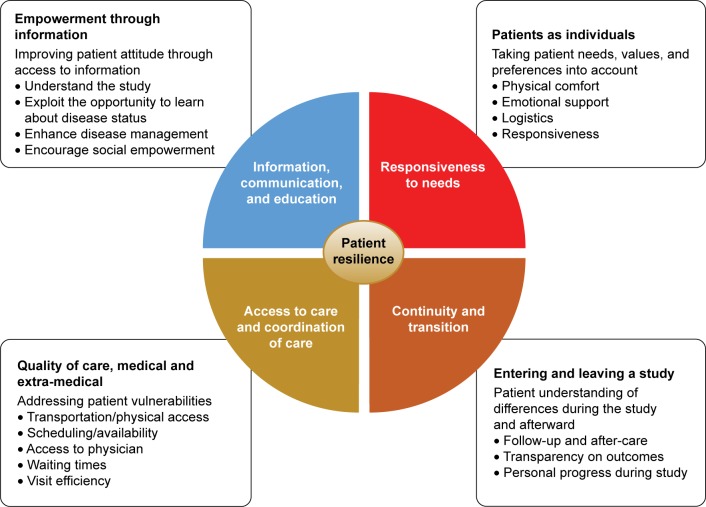

Patients underwent a simulation of two key mock study visits for a clinical trial (informed consent procedure, SLE/LN screening visit, and SLE/LN dosing) with a debriefing period for patients and staff. The informed consent procedure, which lasted 30–45 minutes, was conducted by the investigator or study coordinator, according to the standard site practice. During the consent procedure, patients were briefed on visit simulations and procedures, and patient expectations were obtained. The mock SLE/LN screening visit lasted 2.5/2.0−2.5 hours for the Atlanta/Altoona studies. During the mock SLE/LN screening visit, patients were briefed to explain the simulation process and procedures along with patient expectations and received the study booklet (Altoona study). Afterward, they underwent all study procedures per protocol in a noninvasive format, including radiographs and blood draws. The mock SLE/LN first dosing visit lasted 4.5−5.0/3.5−4.0 hours for the Atlanta/Altoona study. Patients were briefed as before and underwent all mock first dosing visit study procedures per protocol, including mock anifrolumab infusion. The patient debrief involved a semi-structured interview conducted by Deloitte. In the Atlanta study, this research was supported by Parexel Clinical Trial Services (Waltham, MA, USA), which provided an African-American lead interviewer. In the patient debrief, patients were interviewed to collect first-hand perceptions on simulated visits, obtain descriptions of patients’ individual concerns, and incorporate discussion of patients’ personal perspectives. Interview questions were based on the patient sentiment assessment concepts listed in Figure 1. Patient-reported outcome questionnaires were provided in paper and electronic formats for patients to complete during each stage of the clinical trial simulation and took ~30 minutes to 1 hour to complete.

Figure 1.

Patient sentiment assessment.

A standard staff preparation procedure was used for the trial simulation. Investigators and study coordinators were introduced to the trial simulation concept during the site feasibility and simulation preparation phases. Sites were provided simulation “playbooks,” which described the procedures and activities of all simulation participants, including the patients, site staff, and simulation team. Staff were allowed to use either source documentation templates that were prepared for the simulation or their own forms. Deloitte conducted the pre- and post-simulation briefings with investigators, study coordinators, and other participating staff members.

For the Altoona study, Schulman Associates Institutional Review Board (IRB; Cincinnati, OH, USA) reviewed the simulation summary and study materials. Based on a review of the materials, the IRB determined that a clinical trial simulation did not fall under the definition of clinical research and did not require ethics committee approval. For the Atlanta study, the study simulation proposal was presented to the Emory University IRB, which determined that the simulation did not fall under the definition of clinical research. All patients signed informed consent agreements to participate and to permit audio recordings. No patient-identifying information collected or generated was taken offsite. Transcripts from audio recordings were anonymized.

Analytical methodology

An analytical approach based on the frameworks developed by the Picker Institute and The Institute of Medicine was used to facilitate patient interviews and their subsequent analysis.13,14 Patient sentiment was assessed in the study to determine the impact on four patient-centric care domains: information, communication, and education; responsiveness to needs; access to care and coordination of care; and continuity and transition (Figure 1). Impact on patient resilience was also evaluated in the study, with four key aspects measured: physical, emotional, mental, and social. Patient responses were assessed centrally by Deloitte, with comparisons between the study site responses based on overall responses.

Results

The Atlanta study, which took place on April 2−3, 2015, involved six African-American patients (one male, five females) aged 27–60 years with moderate to severe SLE/LN. Five patients had no previous clinical trial experience (Table 1). In addition, patients differed in their cognitive abilities, general education level, and health literacy. The Altoona study took place on December 1–5, 2014, with 12 white females aged 32–75 years with mild to moderate SLE/LN; two participants had no previous clinical trial experience (Table 1).

Table 1.

Patient and site characteristicsa

| Patient characteristics | Atlanta study (N=6) |

Altoona study (N=12) |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 0 | 12 (100) |

| African-American | 6 (100) | 0 |

| Female | 5 (83) | 12 (100) |

| Age range, years | 27–60 | 32–75 |

| Lupus severity | ||

| Mild to moderate | 0 | 12 (100) |

| Moderate to severe | 6 (100) | 0 |

| Time to diagnosis | ||

| <1 year from symptom presentation | 1 (17) | 6 (50) |

| 1–27 (Atlanta)/2–6 (Altoona) years from symptom presentation | 5 (83) | 6 (50) |

| Site characteristic: practice type | Rheumatology | Rheumatology |

Note:

n (%).

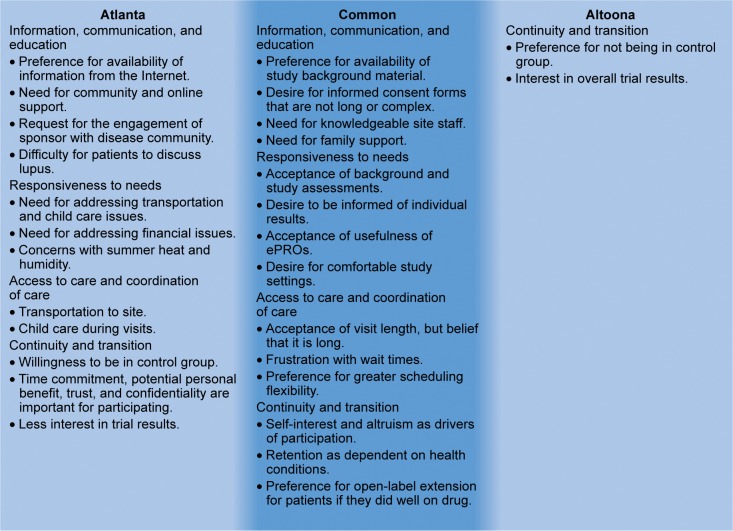

Common experiences expressed by patients from the Atlanta and Altoona studies

Common positive and negative experiences were expressed by patients from both the Atlanta and the Altoona studies, and spanned across different regional, ethnic, and socioeconomic backgrounds (Figure 2). With respect to the information, communication, and education domain, patients found it valuable to have background material provided prior to or during the study. Patients thought that the informed consent forms were too long and complex and should be revised accordingly. They also thought it was critically important to have knowledgeable site staff for providing information on items including side effects, value of research, and answers to questions. In addition, patients expressed a need for and valued support from family and friends.

Figure 2.

Similarities and differences in patient preferences and concerns between the Atlanta and Altoona studies.

Abbreviation: ePRO, electronic patient-reported outcome.

Various common statements associated with responsiveness to needs were expressed. In general, patients did not have concerns with performing baseline and study assessments. They appreciated being informed of their personal results on an ongoing basis during the study. Patients found the various electronic patient-reported outcomes instruments relevant to their experience and easy to use. In addition, patients greatly appreciated comfortable settings, including entertainment and refreshments.

For access to care and coordination of care, patients mentioned that visit length, although often long, was acceptable. However, wait times between procedures were a source of frustration for patients. Patients desired flexibility for scheduling matters, such as adjustments for travel planning and family-related issues. Their preferences included flexibility in time windows for visits, availability of evening and weekend hours, and the option of dividing long visits over 2–3 days.

With respect to continuity and transition, patients in both studies indicated that trial participation was driven by a mixture of self-interest and altruism. Patient willingness to enroll in the study was strong, but retention was dependent on changes in health conditions during the trial. In addition, patients mentioned that if they did well on the study drug, they would be more likely to enroll in an open-label extension.

Different experiences expressed by patients from the Atlanta and Altoona studies

Atlanta study patients also expressed various different preferences and concerns from the Altoona study patients that could potentially be used in clinical trial development for enrolling and retaining African-American patients. These differences may be associated with the two study groups’ socioeconomic and racial dissimilarities. With regard to information, communication, and education, patients from the Atlanta study expressed a greater preference for information from the Internet and conveyed greater importance for strong community and online support than did patients from the Altoona study. Atlanta study patients also recommended that the study and/or sponsor engage with the community (via patient ambassadors or support group leaders) to provide education about the disease and to demonstrate the importance of these studies and their potential impact on patients. Furthermore, unlike Altoona study patients, the Atlanta study patients reported a taboo around discussing SLE that was associated with a lack of education.

For the responsiveness to needs domain, Atlanta study patients indicated a greater importance for transportation and child care help during the visits, particularly during summer months, than did Altoona study patients. Atlanta study patients also had more concerns related to financial matters, such as reimbursement of costs, impact on work, and the potential for stipends. They also mentioned heat and humidity during the summer months as potential issues for retention and compliance, although these concerns could potentially be related to the study location.

For care and coordination of care, Atlanta study patients placed greater emphasis on transportation and child care. With regard to the continuity and transition element, Atlanta study patients, because of their health insurance status (eg, lack of insurance, inadequate insurance), were more satisfied participating than were Altoona study patients, even if they were in the control group. In addition, they placed greater importance on time commitment, understanding of potential personal benefit, trust, and confidentiality of patient data as factors for participation. Furthermore, Atlanta study patients were less interested than Altoona study patients in eventually being told the general results of the trial.

Lessons learned for implementing clinical trial simulations

On the basis of our experience of developing and implementing two clinical trial simulations, we have identified certain factors that we view as important for a successful trial in different locations and for various demographic groups. For planning a clinical trial simulation, sufficient expertise for properly designing and implementing the study is necessary. Objectives of the study (eg, identifying factors to improve enrollment or areas of complexity in a protocol) should be clearly defined. Site selection should be based on factors pertinent to the particular simulation, such as respective disease area experience; racial, ethnic, and demographic interests; and clinical experience.

For patient recruitment, site directors and staff should make the effort to obtain patient trust, particularly for those patients who are unfamiliar with the site. Furthermore, inclusion of uninsured and underinsured patients should be considered because these patients would find it beneficial to receive treatment, even if in the placebo group. Uninsured and underinsured patients may be a particularly important population to include in trials that initially lack a representative number of minority patients.

For patient retention, responding to patient needs is important. Waiting facilities should be comfortable and should have entertainment provided. Site directors and staff should consider reducing patient wait time for procedures because a decrease in wait time would improve patient recognition that site staff members value their time. Another consideration for improving patient retention and engagement is to provide results that are easy for patients to comprehend so that they can understand their health status. The ever-increasing complexity of study protocols and regulations, coupled with the advanced language and extensive length of informed consent documents, requires the study team to demonstrate great sensitivity and adaptiveness for recognizing and supporting those with more limited health literacy.

The skill and attitude of the study coordinator(s) and site staff are also critically important for patient retention and engagement. Study team members should be nimble, sensitive, and reactive enough to allow for inevitable schedule changes. Site staff should anticipate the necessity of accommodating a patient’s schedule. This degree of schedule change impact may differ according to the region and time of year. Furthermore, site staff should better understand how patients view studies and study procedures. If patients express a desire to withdraw, site staff should discuss with them what could make the study a better experience for them.

Another important factor that we identified for a successful clinical trial simulation is the relationship between the CRO or sponsor and the site staff. A good relationship between the CRO or sponsor and the site staff is crucial, for it opens up lines of effective communication. There should be site feedback related to various aspects of the trial, and there should be responsiveness and accountability on the part of both the CRO or sponsor and the site staff. This factor is essential, for often a mechanism to provide feedback is missing. The relationship between the CRO or sponsor and the site staff is relevant also for dealing with issues that are culturally and community sensitive. For such issues, it is necessary to think creatively and develop different approaches. One such example is preparing patient materials that account appropriately for educational, ethnic, and socioeconomic differences. Furthermore, the CRO may have to tailor its approach directly to sites with significant numbers of patients from ethnic or racial minority groups or with lower socioeconomic status.

Site staff noted that they needed help managing the increased workload associated with protocol amendments. Site staff discouraged risk-based monitoring because of the time/work associated with lengthy monitoring forms.

Discussion

We present the concerns and preferences expressed by patients involved in two clinical trial simulations: one involving African-American patients with moderate to severe SLE/LN from an urban indigent care clinic in Atlanta, and the second involving white female patients with mild to moderate SLE and who were lower-middle-class. On the basis of a literature review, we believe that this is the first report of the use of a mock clinical trial approach that assessed/predicted patient sentiments during the actual clinical trial and proactively adjusted the protocol and the related operational details to optimize patient experience. Clinical trial simulations present various advantages versus other approaches used for obtaining patient feedback, including patient trial surveys and patient advisory boards. Simulations are uniquely designed for the particular trial being developed. For this reason, they can identify patient concerns for related studies in the future that would not necessarily be identified from literature reports involving studies with different trial designs and populations. Simulations can be designed to identify reasons for issues that the investigator expects to encounter in a particular study, such as difficulties in increasing the diversity of the patient population for particular racial or socioeconomic backgrounds. Findings from these simulations can thus improve the recruitment process, which subsequently can increase the retention rate in clinical trials. Simulations are performed in a real-world setting, involving both patient and site feedback. They differ from other types of studies, which lack feedback from some relevant participants and whose feedback is obtained potentially months after the event.

Several sentiments were previously known by the site staff and are consistent with reports from previous studies that evaluated patient surveys from clinical trials for other diseases.15,16 In a review of 4,961 surveys from patients at 15 U.S. clinical research centers, patients were more likely to rate their experience as highly favorable if they trusted their investigators and had good communication with them.15 Furthermore, most patients (85%) wished to receive results from the study.15 In a survey of patients infected with human immunodeficiency virus who participated in the ESPRIT study of different therapeutic regimens, 90% of patients indicated an altruistic reason for their involvement.16

Some of the findings reported in this study are analogous also to those in a report that investigated reasons for inadequate recruitment for a feasibility study in an SLE clinical trial.17 Patients in the study identified health status, involvement with their personal physician, the chance to learn more about their disease, and altruism as key factors in their decision to participate.17 Patients who did not participate in the study noted health status, medication concerns, randomization apprehensions, and personal issues (eg, time allocation) as reasons for not participating.17 In our Atlanta study, African-American patients with low income emphasized that studies should place greater consideration on their financial requirements and logistical needs, such as those related to transportation and child care.

Based on these results, we propose certain recommendations to improve study procedures to increase retention, recruitment, and compliance for clinical trials (Table 2). Although we were able to implement some of these recommendations in different ways in our studies, we were not able to apply all of them. In all cases, compliance and Good Clinical Trial Practice guidelines and appropriate country and local regulations would need to be met before applying these recommendations. Some of these recommendations may be relevant for simulations and clinical trials for diseases other than SLE. In addition, some of these recommendations may be particularly relevant for African-American patients.

Table 2.

Recommendations for improving study procedures to increase retention, recruitment, and compliance for clinical trials

| Finding | Impact | Recommendations |

|---|---|---|

| Information, communication, and education | ||

| 1. Not all patients are fully informed about and appreciate study requirements at the time of enrollment. | Lower retention as a result of dropouts as true trial burden becomes apparent. | • Provide more time between provision of consent document and site-led consent process. • Use electronic study information/consent document, with definitions of words embedded and an audio functionality; a relatively simple tool such as this is likely to engage investigators and facilitate the consenting process. • Offer simplified paper informed consent form. • Provide guidance to sites on minimum understanding to be demonstrated by patients. • Provide options available before and during the study for patients to be fully informed according to their own learning styles. |

|

| ||

| 2. Patients perceive a benefit from having up-to-date information about the latest science and treatment options for their disease. | Participation in a clinical trial is an opportunity to increase patient engagement by providing new data of interest to patients. | • Use study and site as a focal point for providing information with salience and relevance to patients about their disease. • Develop and/or provide materials to participating patients on the “state of the art” for SLE. • Provide access to materials designed to help patients feel empowered about managing their condition. |

|

| ||

| 3. Patients are overwhelmed by the amount and complexity of information provided during screening and enrollment and display cognitive biases, including primacy, recency, self-relevance effects, and use of heuristic or rule-of-thumb strategies for decision making. | If patients do not consider how study participation will affect their lives, the reality of participation may lead them to feel dissatisfied, influencing, eg, PRO responses, or may lead patients to drop out. | • Reconfirm patient consent with different aspects of the study at intervals/milestones during the study to ensure ongoing comfort with the study. • Provide any patient materials, eg, study booklet/website, for as long a period as possible in advance of enrollment. • Provide simplified materials that are more accessible/easily digested. • Encourage involvement from family/friends where possible to allow the patients some leverage in dealing with a large amount of data. |

|

| ||

| 4. Study booklet and website are valuable additions to the range of information on offer to the patients and are likely to be used by patients (not all). Some patients had issues with the font size and color and image sizes. |

Study information well presented will allow patients to have a point of reference and a foundational understanding to support them throughout the study. | • Continue to refine the study booklet. • Consider reinstating notes pages in the study booklet, if it is possible to avoid an additional monitoring step. • Conduct readability assessments of the booklet with representative samples of patients. • Provide the booklet widely to patients who are considering enrollment/undergoing screening; consider lost booklets as a study advertising/awareness cost. • Provide the screening patients with static website access (booklet material), providing study booklet on randomization, if cost to provide booklets is an issue. |

|

| ||

| 5. Patients want to know how their SLE experience compares with that of others and are interested in the study results, their own results, and the relative positioning of their response or disease progression relative to those of the study cohort. | Patients are engaged by information that helps them feel in control of their conditions, which includes tracking of performance. | • Proactively provide a comparative assessment of a patient’s conditions (investigators) (eg, compared with baseline, or with patients like them). • Provide educational material to patients on how lupus is assessed as part of the study (eg, explanations of SLEDAI, etc.). • Prior to the end of the study, estimate for both the sites and patients the time frame in which the patients can expect to be unblinded and receive the study results and their individual responses relative to those of the rest of the cohort. • Provide timely follow up with patients according to commitments made. • Provide materials in lay terms and with recommendations for disease management. • Establish a mechanism to inform study participants if the investigational product receives a marketing authorization or if development is discontinued. |

|

| ||

| 6. Family and friends of patients are often nervous or not comfortable with patients taking part in a clinical trial. | Negative attitudes to clinical research limit recruitment and increase the probability of patient dropout. | • Seek to involve patients’ families where possible to ensure that concerns are allayed and that the positive aspects of trial participation are supported. • Develop materials that can be used by patients to educate friends and family on their disease status. • Encourage patients to be accompanied by family/friends for study visits and encourage site staff to engage positively with them. • Enlist the support of the patients’ social network as co-responsible for patients’ attendance (when possible). • Create an appropriate reward mechanism for supportive family/friends. |

|

| ||

| 7. A taboo against discussion may exist in certain communities around a diagnosis of SLE, possibly because of a confusion of the term “autoimmune” with “immune deficiency.” | Unwillingness to communicate with family or others about their health status could limit patients’ willingness to be involved. | • Create awareness at sites that this possibility of a taboo exists and to be mindful of it. • Provide educational material to sites and patients. • Support discussions with family members (investigators or study coordinators). |

|

| ||

| 8. Some patients are medically illiterate to the extent of not knowing what they are taking to manage their condition. | The meaning of access to standard of care may not be fully appreciated by patients. | • Investigators and coordinators should take care to explain to patients when participation in the study will give patients access to treatment options that may otherwise not be available to them. |

|

| ||

| 9. A kidney biopsy is a painful and traumatic experience for some patients. | The requirement for the kidney biopsy could limit patient willingness to enroll. | • Educate investigators and site staff to clarify that the kidney biopsy is not a study procedure, but that it is a necessity of their diagnosis that they would have to undergo if entering the study or not. |

|

| ||

| Responsiveness to needs | ||

| 1. Altruism is an important component of a decision to enroll in a clinical study. | Reinforcing a patient’s sense of doing something good and larger than oneself is likely to increase commitment and engagement with the study. | • Seek opportunities to recognize and speak authentically about the patients’ contribution to other sufferers and future generations. |

|

| ||

| 2. The degree of disruption to patients’ lives due to study participation is very important to patients’ propensity to enroll and continue in the study. | The study may be difficult to recruit for if the visit duration and number of procedures per visit cannot be mitigated. | • Establish total time commitment of a study visit by sites, and communicate this as a commitment to patients and meet that expectation. • Consider if and how visits could be split without causing disruption to the data and to the study coordinator planning. • Provide guidance to sites on how to split a visit without triggering monitoring or data queries. |

|

| ||

| 3. The degree of support of family and friends and fellow patients has an effect on the experience of clinical trial participation. | Enlisting allies in an endeavor to try to improve one’s health such as clinical trial participation is a powerful motivator. | • Encourage awareness and involvement of family members in patients’ participation. • Consider if and when responsibility can be given to family members to engage them in the patient’s well-being. • Provide material to the participant that will facilitate discussion with family members. |

|

| ||

| 4. The completion of ePRO questionnaires is generally viewed as easy by the majority of patients; however, there are exceptions. Some patients find the exercise exhausting. | As the first item performed by patients at the study visit, ePRO potentially sets the tone for the study visit. | • Identify patients who are potentially uncomfortable with the questionnaire or the use of the ePRO device and provide them with the option of completing paper versions. • Consider allowing patients the option to complete paperwork at home, decoupled from study visits. |

|

| ||

| 5. Some patients will have concerns associated with the need to undergo additional Pap smears. | For those patients with Pap smear concerns, this perception may limit their willingness to participate. | • Consider how to reduce the probability of required Pap smear by using the window of acceptability. • Ensure that Pap smears performed by patients’ usual obstetrician/gynecologist can be accepted. • Educate patients on the usual benefit of having this procedure, explaining that in a 16-month period they should probably have had a Pap smear in any case. |

|

| ||

| 6. Providing the right type of support to study coordinators will give them the incentive to drive patients to a given study where a choice exists. | Study coordinators often have a choice of studies in which to place patients and will select the study in their own interest if there is no clear distinction for the patient. Equally, difficult or complex studies may under-recruit for the same reasons in the absence of competition. | • Conduct further research to identify the specific pain points of study coordinator and how these can specifically be mitigated. • Perform regular sampling of study coordinator experiences and feedback to the sponsor study team with a commitment to act on widely expressed concerns. • Promote and communicate any improvements made to the study to demonstrate that the study coordinators’ voices are being heard. |

|

| ||

| 7. Visits are longer than optimal for patient population, and the ability to have flexibility around patients’ schedules is a minimum requirement. | Without the ability to reschedule, drop some visits, or avoid some assessments for reasonable cause, the patients will not feel in control and are likely to disengage initially emotionally and then physically by dropping out. | • See previous recommendations on split visits (finding 2 in “Responsiveness to needs” subsection). • Work with sites to establish an optimal visit flow structure to minimize patient time on site. • Proactively identify and communicate best practices for visit efficiency at sites. • Consider if key/specific sites will require additional resources and if these can be provided (eg, administrative support in advance of monitoring visits). |

|

| ||

| 8. Monthly visits that require more than half a day to complete will effectively exclude patients who work. | A visit lasting more than half a day may require use of vacation time by patients. For others, it will result in loss of earnings. | • See previous recommendations for visit flexibility (finding 7 in “Responsiveness to needs” subsection). • Provide reimbursement for lost earnings to allow hourly wage workers to participate. • Early morning and late evening visits or visits that can be split over 2 days could be provided. |

|

| ||

| 9. Child care is a concern for patients with children, particularly during summer months. | If options are not communicated upfront, patients with child care responsibilities may not enroll. | • Provide reimbursement for child care. • Provide temporary crèche facilities. |

|

| ||

| 10. Transport to and from sites is a material concern for patients in lower socioeconomic groups. | Without a reliable form of transportation, certain patients will not be able to enroll and/or will have a high likelihood of missed visits or study dropout. | • Provide transportation or transportation reimbursement via the site. • Clearly communicate the availability of this option to patients. |

|

| ||

| 11. Possibility that younger patients may be less inclined to manage their disease adequately. | If true, there may exist an untapped resource of poorly controlled patients who could benefit from trial participation. If this is not addressed, there is a possibility of an unrepresentative sample biased toward older patients. | • Recognize that younger patients may have different needs from an older cohort. • Develop patient materials targeted at a younger age group. • Use the “Lupus Ambassadors” concept to identify these younger patients for screening. • Create a subsection of any forum or community to address the younger cohort. • Encourage investigators to use the study as an educational tool for reaching the medically underserved in their community. |

|

| ||

| 12. Lupus creates a sense of isolation in many patients who have a need for community. This is not necessarily a desire for a connection in real life, but may also be a requirement for virtual contact. | Creation of an online or real- life community for patients could provide a support structure for patients if and when the study becomes challenging. | • Encourage investigators to allow patients to engage with one another. • Allow proliferation of online communities if they arise spontaneously. • Create a study-specific online community for patients to interact with each other. • Leverage existing lupus communities online or in real life by directing patients toward them. |

|

| ||

| 13. Community engagement is likely to be very important for the African-American population; peer and family approval seem to be more of a factor in decision making. | Opportunity to drive recruitment and retention by leveraging community effects. | • Identify existing lupus communities local to sites and engage with them. • Identify “SLE Ambassadors” active in the community who can help sites identify and overcome barriers to recruitment. • Use SLE community involvement to differentiate the study sponsor as a patient-focused partner in fighting SLE. |

|

| ||

| Access to care and coordination of care | ||

| 1. Maintaining patient comfort during study visits is important to the patients’ experience of study participation. | Positive experiences during study visits are assumed to be linked to patients’ willingness to return to the clinic for follow up visits. | • Ensure that study coordinators are aware that discomfort during the study visit could affect retention. • Encourage specific actions to address patients’ individual difficulties, such as pain, fatigue, etc. • Consider and develop an action plan for how patients will be engaged for study visits that occur during a flare. |

|

| ||

| 2. The completion of the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale questionnaire is a negative experience for study participants. | Repeated questioning on suicidal ideation is likely to be uncomfortable for patients and could potentially create an unintended impression of risk. | • Explain to patients the reason for the assessment before administration. • Ensure that physicians administering the questionnaire have been trained in the use of the tool. • Consider if the tool needs to be used at every site visit. Consider if the tool can be used selectively, that is, not for patients with no relevant history. |

|

| ||

| 3. Uninsured and underinsured patients are more comfortable with the probability of receiving placebo compared with insured patients. | This circumstance can result in preferential selection of patients of lower socioeconomic status and with associated lower health literacy and health status, with unknown effects on response rate. | • Ensure that the open-label extension option is clearly communicated at enrollment, when applicable. • Ensure that patients understand that they will receive standard of care whether they are given the placebo or not. Where applicable, indicate if this is a change to the individual patient’s regimen. • Highlight that participation in the study means that the patient’s SLE is more closely monitored than it would be otherwise without participation, and that the physician will always recommend the course of action in the best interest of the patients, regardless of study participation. |

|

| ||

| 4. Large volumes of blood drawn are a concern to patients. | A large number of tubes to be filled is likely to overrepresent the perceived volume of blood to be taken, leading to patient discomfort. | • Use combined sample tubes for aliquoting offsite at analytical labs. • Use prelabeled tubes to allow the study coordinator to be more efficient. • Explain the total volume of blood drawn for a visit in terms that are familiar (eg, volume equivalent to two tablespoons, etc). • Avoid presenting the full lab kit to patients at the same time. |

|

| ||

| 5. The administrative burden on site staff generated by “loose” lab kits that need to be created is excessive and likely to lead to errors. Prelabeled drug kits preassembled by visit are preferred. | Impact on study coordinator choice of study for which to recruit. | • See finding 4 in “Access to care and coordination” subsection. |

|

| ||

| 6. Study coordinators request a direct line of communication with the decision maker for the sponsor to be able to quickly deal with “unique” patient situations as they arise. | Impact on study coordinator choice of study for which to recruit, and may avoid loss of potential recruits because of undue caution on part of study coordinator, as well as reduce dropout rate due to erroneous recruitment. | • Establish a list of decisions that can be made by the coordinator for repeated/common situations (when possible). • Maintain accessible, easily searchable decision log to support study coordinator’s decision making. • Use an international team to provide support during out-of-office hours, establishing a joint decision-making capability (when possible). • Ensure that areas where there is no need for discretion are made clear to the study coordinator. For areas where there is need for discretion, verify that there is no potential cost to the study coordinator for making a decision. • Establish a minimum turnaround time for response to study coordinator’s queries. |

|

| ||

| 7. Any reduction in the administrative burden of site staff that can be applied has the potential to affect patient experience positively by creating additional capacity for the study coordinator to focus on the patient experience. | Potential positive impact on study coordinator’s choice of study for which to recruit. Such an improvement can result in better care from the study coordinator for patients in the study. | • Track study coordinator-identified pain points and address where possible. • Establish and maintain a study coordinator forum at which coordinators can share information. • Follow up on clinical research agency/monitoring issues if identified (clinical research agency quality was a high-sensitivity point for study coordinators). |

|

| ||

| 8. The vital signs and blood draws section in the protocol (SLE and LN) is quite difficult to understand. | The complexity of this section can increase the potential for site error. | • Provide guidance with examples as to how this section can be interpreted. Reference minimum and expected numbers of vitals taken. |

|

| ||

| 9. Some patients view study visits as an excuse to take time out from their lives. | This circumstance presents an opportunity to position trial participation as a resilience boosting, positive experience. | • Encourage patients to enjoy the break afforded by the study visit if they are so inclined. • Remind all patients of the visit duration in advance and provide, or encourage them to bring, books, magazines, music, or other diversions to use during the study visit. • Find out what the patients would be doing if not at the visit, and explore options to take care of that responsibility for them to enable study participation (eg, dry cleaning, dog walking). |

|

| ||

| 10. The 24-hour urine sampling was not seen as practical by site staff, who expressed concerns for data quality linked to patient collection. Patients, however, did not express undue concerns. | 24-hour urine collection represents a burden for site staff. | • Provide a robust mechanism for the collection and storage of 24-hour urine sampling from patients. • Consider if it can be collected directly from patients. • Provide suitable materials to minimize the burden on staff and the risk of unusable data (eg, carry bags, etc.). |

|

| ||

| Continuity and transition | ||

| 1. Patients want feedback on the assessments they undergo in the course of the study and how they relate to their general health status and the progression (improvement or deterioration) of their SLE status. | Satisfying this informational need of patients will increase engagement; the possibility of greater insight into one’s health or condition could be a deciding factor in participation and retention. | • Investigators could provide a verbal or printed summary of the lab results to patients and the implications for their general health. • Investigators could schedule a “My Lupus” review with patients at intervals during the study. • Provide regular, eg, quarterly, readouts on study progress designed for participating patients. |

|

| ||

| 2. Patients see the possibility of an open-label extension as a potential benefit. | This circumstance provides an opportunity to drive greater recruitment through a clearer message around the potential benefit to patients if they are responders. | • Ensure the open-label extension option is well understood prior to enrollment, as well as the implications. • Remind patients of the open-label extension option at intervals throughout the study to ensure the message is not lost. |

|

| ||

| 3. The study coordinator may find the inclusion/exclusion criteria challenging when borderline scores would exclude a patient known to the investigator to be otherwise suitable for the study. | General observations about studies from staff feedback (examples provided included age, weight, and SLEDAI) suggest that the selection criteria may appear arbitrary to site staff, with a negative impact on attitude to the study if recruitment is difficult. | • Provide the summary rationale to study coordinators and investigators on the inclusion and exclusion criteria selected. • Seek out the opinion of study coordinators on potential recruitment challenges, and host a discussion about potential mitigation and options. |

|

| ||

| 4. Simulation patients with experience of clinical trial participation and site staff are unhappy with the time it usually takes for them to be unblinded and to receive the study results. | A poor experience, or lack of follow up, is likely to devalue the patients’ participation in their mind and will reduce the likelihood of future cooperation, participation, or advocacy of the product or company. | • See finding 5 in “Information, communication, and education” subsection. |

Abbreviations: ePRO, electronic patient-reported outcomes; LN, lupus nephritis; PRO, patient-reported outcomes; SLE, systemic lupus erythematosus; SLEDAI, SLE Disease Activity Index.

Although these were SLE trial simulations, we believe that many of our findings would be useful in studies of other diseases. However, we understand that investigators may be interested in conducting simulations specific to their particular disease. Because implementation of clinical trial simulations is complicated, we recommend reviewing certain considerations from our experience before deciding if a trial simulation would be of value (Table 3). For instance, investigators should determine whether they fully understand the patient population, any difficulties in patient recruitment, and the complexity of the protocol. Furthermore, we recommend conducting such simulations in an established framework, as we have done, to analyze and report the findings more thoroughly.

Table 3.

Questions for sponsors to consider in deciding if a protocol simulation design would be of value

| Is there a significant unmet patient need? |

| Are there recent changes in standard of care? |

| Does the sponsor have significant internal/current expertise in designing similar studies (indication and mechanism of action)? |

| Does the sponsor expect difficulty in enrolling patients (based on the study design and/or competitive landscape)? |

| Based on the protocol design, does the sponsor expect a high dropout rate or poor compliance to study visits/procedures? |

| Are there significant design challenges that might benefit from patient insights/input? |

| Does the sponsor think that the draft protocol is too complex? |

| Does the sponsor understand moments pre-/on-/post-study that matter disproportionately to the patient? |

In conclusion, insights from these simulations can be directed toward designing future clinical trials to improve recruitment, retention, compliance, and advocacy, especially for minority patients.

Acknowledgments

Editorial assistance was provided by Alan Saltzman, of Endpoint Medical Communications, Conshohocken, PA, USA, and Michael A Nissen, ELS, of AstraZeneca. Study support was funded by AstraZeneca.

Footnotes

Disclosure

SSL and AJK are study investigators contracted by AstraZeneca and their respective institutions, DM is an employee of Deloitte and an AstraZeneca vendor. MEP and FSO are AstraZeneca employees. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Sully BG, Julious SA, Nicholl J. A reinvestigation of recruitment to randomised, controlled, multicenter trials: a review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials. 2013;14:166. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-14-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDonald AM, Knight RC, Campbell MK, et al. What influences recruitment to randomised controlled trials? A review of trials funded by two UK funding agencies. Trials. 2006;7:9. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-7-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Research Council Panel on Handling Missing Data in Clinical Trials . The Prevention and Treatment of Missing Data in Clinical Trials. Washington, DC: The National Academy Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Unger JM, Gralow JR, Albain KS, Ramsey SD, Hershman DL. Patient income level and cancer clinical trial participation: a prospective survey study. JAMA Oncol. 2016;2(1):137–139. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.3924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The Society for Women’s Health Research, United States Food and Drug Administration Office of Women’s Health Dialogues on diversifying clinical trials. Successful strategies for engaging women and minorities in clinical trials. 2011. [Accessed November 2, 2016]. Available from: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/ScienceResearch/SpecialTopics/WomensHealthResearch/UCM334959.pdf.

- 6.Vina ER, Utset TO, Hannon MJ, Masi CM, Roberts N, Kwoh CK. Racial differences in treatment preferences among lupus patients: a two-site study. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2014;32(5):680–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cooper AA, Conklin LR. Dropout from individual psychotherapy for major depression: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Clin Psychol Rev. 2015;40:57–65. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lim SS, Bayakly AR, Helmick CG, Gordon C, Easley KA, Drenkard C. The incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus, 2002–2004: the Georgia Lupus Registry. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):357–368. doi: 10.1002/art.38239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Somers EC, Marder W, Cagnoli P, et al. Population-based incidence and prevalence of systemic lupus erythematosus: the Michigan Lupus Epidemiology and Surveillance program. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66(2):369–378. doi: 10.1002/art.38238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Furie R, Petri M, Zamani O, et al. A phase III, randomized, placebo-controlled study of belimumab, a monoclonal antibody that inhibits B lymphocyte stimulator, in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2011;63(12):3918–3930. doi: 10.1002/art.30613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Furie R, Khamashta M, Merrill JT, et al. Anifrolumab, an anti-interferon-α receptor monoclonal antibody, in moderate-to-severe systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2017;69(2):376–386. doi: 10.1002/art.39962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goldberg A, Geppert T, Schiopu E, et al. Dose-escalation of human anti-interferon-alpha receptor monoclonal antibody MEDI-546 in subjects with systemic sclerosis: a phase 1, multicenter, open label study. Arthritis Res Ther. 2014;16(1):R57. doi: 10.1186/ar4492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rathert C, Wyrwich MD, Boren SA. Patient-centered care and outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. Med Care Res Rev. 2013;70(4):351–379. doi: 10.1177/1077558712465774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Institute of Medicine (US), Committee on Quality of Health Care in America . Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kost RG, Lee LM, Yessis J, Wesley RA, Henderson DK, Coller BS. Assessing participant-centered outcomes to improve clinical research. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(23):2179–2181. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1311461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wendler D, Krohmal B, Emanuel EJ, Grady C, ESPRIT Group Why patients continue to participate in clinical research. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(12):1294–1299. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.12.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Costenbader KH, Brome D, Blanch D, et al. Factors determining participation in prevention trials among systemic lupus erythematosus patients: a qualitative study. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57(1):49–55. doi: 10.1002/art.22480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]