A 71-year-old woman with non-operable, peripheral type chronic thrombo-embolic pulmonary hypertension (CTEPH) and with World Health Organisation (WHO) class III dyspnoea was admitted to our department for balloon pulmonary angioplasty (BPA). Right heart catheterisation confirmed pulmonary hypertension (mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) 37 mm Hg, mean right atrial pressure (mRAP) 6 mm Hg, pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) 13 mm Hg, pulmonary vascular resistance (PVR) 214 dyn · s · cm–5 and cardiac Index (CI) 4.1 l/min · m2) and pulmonary scintigraphy showed multiple segmental perfusion defects (segments 1, 2, 8, 9 in the left lung and 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 in the right lung). Functional testing demonstrated a reduced 6-minute walk distance of 220 m. The BPA was performed from a right femoral vein approach. The 90-cm long 6Fr sheath (Flexor Shuttle Guiding Sheath, Cook Medical, Bloomington, IN, USA) and right Judkins 6-Fr guide catheter were used to achieve a good approach to the ostium of the A1 + A2 segmental branch. Selective pulmonary angiography revealed the subtotally occluded A1 segmental branch of the left pulmonary artery (Figure 1 A). Subsequently a Whisper MS coronary guidewire (Abbott Vascular, Santa Clara, Ca, USA) was advanced through the lesion to the distal part of the vessel. Then optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the target vessel was performed with the DragonFly (St. Jude Medical, USA) OCT catheter. Iodinated contrast was infused at a flow rate of 5 ml/s over 4 s at 400 psi of pressure and OCT images were acquired. Subsequently the vessel was accurately measured in several locations and the proper size of the balloon was selected to reduce the risk of post-reperfusion oedema.

Figure 1.

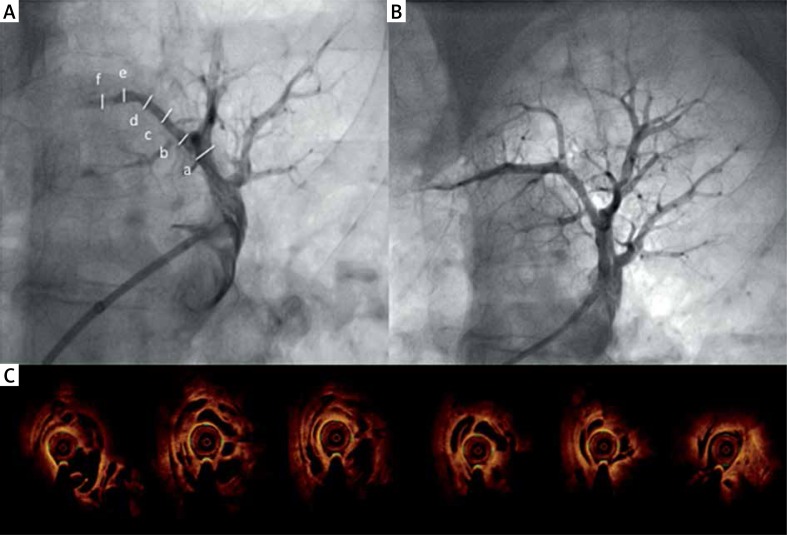

A – Selective angiography of A1 segmental branch left pulmonary artery before BPA. Subtotal occlusion of distal part of artery and minor lesions (webs) in mid part of the vessel. B – Optical coherence tomography cross-sections of the entire artery with extensive honeycomb lesions (meshwork). C – Angiography after BPA procedure

Surprisingly, OCT revealed extensive changes in the proximal and mid part of the target artery (“colander lesions” or meshwork) (Figure 1 B). The diameter of the vessel was 2.23 mm × 2.42 mm. Four inflations of a 2.0 mm × 20 mm semi-compliant balloon with the pressure of 4–10 atm were performed along the entire artery with good angiographic and hemodynamic effects (Figure 1 C). The procedure was uneventful. Three more BPA sessions at intervals of a few weeks were performed and mPAP was reduced to 29 mm Hg (mRAP – 7 mm Hg, PCWP – 13 mm Hg, PVR – 167 dyn · s · cm–5, CI – 4.1 l/min · m2) and 6-minute walking test (6-MWT) increased to 430 m. The BPA is an emerging method of treatment of patients with inoperable CTEPH [1, 2]. The use of intra-vessel imaging (intra-vessel ultrasound – IVUS) during BPA procedures has been shown to reduce complication frequency. The OCT offers better spatial image resolution (10–20 µm, which is tenfold higher than obtained with IVUS), higher reproducibility and lower inter- and intraobserver variability [3]. The OCT allows one to determine the location, extent and character of the pulmonary artery lesions and helps to choose the appropriate balloon size and length [4, 5]. However, it requires a high-pressure contrast injection, and the clearance of the pulmonary vessel might be insufficient in some cases, which may limit the usefulness of this technique in some cases.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Kurzyna M, Darocha S, Koteja A, et al. Balloon pulmonary angioplasty for chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Post Kardiol Interw. 2015;11:1–4. doi: 10.5114/pwki.2015.49176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mizoguchi H, Ogawa A, Munemasa M, et al. Refined balloon pulmonary angioplasty for inoperable patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012;5:748–55. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.971077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ikeda N, Kubota S, Okazaki T, et al. Comparison of intravascular optical frequency domain imaging versus intravascular ultrasound during balloon pulmonary angioplasty in patients with chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016;87:e268–74. doi: 10.1002/ccd.26437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roik M, Wretowski D, Łabyk A, et al. Refined balloon pulmonary angioplasty driven by combined assessment of intra-arterial anatomy and physiology – Multimodal approach to treated lesions in patients with non-operable distal chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension – Technique, safety and efficacy of 50 consecutive angioplasties. Int J Cardiol. 2016;203:228–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.10.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roik M, Wretowski D, Irzyk K, et al. Familial chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension in a mother and a son: successful treatment with refined balloon pulmonary angioplasty. Pol Arch Med Wewn. 2016;126:1014–6. doi: 10.20452/pamw.3723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]