Abstract

All patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) should be managed with guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT), which reduces progression of atherosclerosis and prevents coronary thrombosis. Revascularization is also indicated in patients with SIHD and progressive or refractory symptoms, despite medical management. Whether a strategy of routine revascularization (with percutaneous coronary intervention or coronary artery bypass graft surgery as appropriate) plus GDMT reduces rates of death or myocardial infarction, or improves quality of life compared to an initial approach of GDMT alone in patients with substantial ischemia is uncertain. Opinions run strongly on both sides, and evidence may be used to support either approach. Careful review of the data demonstrates the limitations of our current knowledge, resulting in a state of community equipoise. The ongoing ISCHEMIA trial (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness With Medical and Invasive Approaches) is being performed to determine the optimal approach to managing patients with SIHD, moderate-to-severe ischemia, and symptoms that can be controlled medically.

Keywords: angina pectoris, coronary artery bypass, coronary artery disease, guideline-directed medical therapy, percutaneous coronary intervention

Patients with obstructive atherosclerotic coronary artery disease (CAD) may be asymptomatic (with or without ischemia), or present with symptoms ranging from stable angina, to acute coronary syndromes (ACS) (unstable angina, non– ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, or ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction), to sudden cardiac death. All patients with established CAD should be prescribed guideline-directed medical therapy (GDMT) to mitigate progression of atherosclerosis and to prevent myocardial infarction (MI) and cardiovascular death (1,2). In patients with biomarker-positive ACS, it is widely accepted that routine revascularization, in addition to GDMT, reduces the short- and long-term rates of death and MI compared with a more conservative approach (3–5). By contrast, the extent to which routine revascularization reduces death or MI, or improves quality of life (QoL) in patients with stable ischemic heart disease (SIHD) represents one of the greatest uncertainties in contemporary cardiology. Given that an estimated 15.5 million Americans have CAD, and that revascularization is performed in more than 1.3 million patients per year in the United States alone (6), the appropriate (but judicious) application of revascularization has enormous implications for the medical and economic health of the nation and the global community.

Early randomized trials of coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery versus conservative care in patents with SIHD performed several decades ago suggested a survival benefit for CABG in patients with extensive anatomic disease, in whom a large amount of myocardium was at risk (left main disease, 3-vessel disease, and possibly 2-vessel disease involving the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery) (7). Ischemia on an exercise stress test also identified patients in whom mortality was reduced with CABG compared with medical therapy (MT) (7). These earlier randomized trials of CABG versus MT, however, antedated the more contemporary use of “disease-modifying” pharmacological interventions, including statins, inhibitors of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone axis, and antiplatelet agents that individually have been shown to reduce death and MI in placebo-controlled trials. The aggregate use of such secondary prevention therapies, along with lifestyle interventions, such as cigarette smoking cessation, diet, and regular exercise, has been referred to as optimal medical therapy (OMT), or GDMT (1,2).

More recently, the benefits of routine revascularization in SIHD have been questioned by the similar rates of death and MI observed in OMT-treated patients with and without percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in the COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) trial, and with and without PCI or CABG in the BARI 2D (Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes) trial (8,9). It may be argued that revascularization in SIHD may not be beneficial because not all anatomically obstructive coronary stenoses produce ischemia, or because not all high-grade coronary stenoses result in cardiac death and/or MI, or conversely, because most cases of cardiac death and/or MI arise from angiographically mild coronary lesions, which are not revascularized. However, some observational studies and hypothesis-generating substudy data from randomized trials suggest that the magnitude of ischemia is associated with adverse outcomes and that alleviation of ischemia may improve prognosis. Conversely, credible studies drawn from different (or even the same!) data-sets have cast doubt on this premise. And importantly, often lost in this discussion is the extent to which revascularization improves QoL, a worthwhile goal, assuming noninferior rates of “hard” adverse event endpoints and reasonable cost-effectiveness.

Recent clinical practice guidelines from the United States and Europe, as well as U.S. appropriate use criteria, endorse GDMT for all patients with SIHD, but recommend (with variable levels of certainty) consideration of revascularization in patients with significant ischemia or symptoms that persist despite MT (10–14). Despite this uncertainty, highly enthusiastic proponents of both routine and selective revascularization for SIHD patients with ischemia may be found, and nearly everyone has an opinion. Indeed, attitudes run so strongly on this topic that it may be questioned whether clinical equipoise exists, although, when pushed, nearly all agree that definitive trials addressing the role of revascularization in optimally treated SIHD patients with substantial ischemia have not yet been performed.

The purpose of this review is to describe the evidence supporting the initial strategies of routine revascularization plus GDMT versus GDMT alone, with revascularization reserved for MT failure (e.g., progressive or refractory symptoms or the development of ACS), in patients with SIHD and moderate or severe ischemia. Each perspective is summarized in Table 1. The evidence is presented as an internal debate, and the reader may naturally gravitate to one position or the other. We recommend that those with a strong preconceived preference pay particular attention to the data supporting the opposite view. The authors believe that on the basis of the present level of evidence, a justifiable case can be made for either an initial strategy of upfront revascularization (with PCI or CABG, as determined by the local heart team) plus GDMT, or an initial strategy of GDMT alone. The equipoise expressed in this document served as the impetus for the collaborative ISCHEMIA trial (International Study of Comparative Health Effectiveness with Medical and Invasive Approaches), as described later.

TABLE 1.

Supportive Evidence for an Initial Routine Revascularization Strategy Plus GDMT Versus GDMT Alone in Patients With SIHD

| Favors an Initial Strategy of Routine Revascularization |

|

| Favors an Initial Conservative Strategy |

|

CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; CAD = coronary artery disease; GDMT = guideline-directed medical therapy; LDL = low-density lipoprotein; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention; PCSK9 = proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9; QoL = quality of life; SIHD = stable ischemic heart disease.

THE CASE FOR ROUTINE REVASCULARIZATION IN PATIENTS WITH SIHD AND ISCHEMIA

OVERVIEW

Revascularization may benefit SIHD patients by preventing death, MI, and unstable angina (which, even if successfully managed with urgent hospitalization and treatment, may be more distressing for patients than a controlled elective procedure), and by improving QoL. More than 25 years ago, Ellis et al. (15) reported that the incidence of anterior MI increases with the severity of untreated left anterior descending coronary artery lesions. The extent of incomplete anatomic revascularization after PCI and CABG is strongly associated with subsequent death, MI, and recurrent angina requiring rehospitalization (16,17). Furthermore, large-scale, nonrandomized studies have reported improved prognosis with revascularization in SIHD. In a propensity-matched observational analysis in 39,131 patients with SIHD, early revascularization was associated with fewer deaths and MI during 4-year follow-up, compared with initial MT alone (Figure 1) (18). Similarly, in a study of 15,223 patients with newly diagnosed SIHD by coronary computed tomographic angiography (CCTA), patients with high-risk CAD in whom revascularization was performed within 90 days had significantly reduced mortality at a median 2.1-year follow-up compared with those treated medically (2.3% vs. 5.3%, p = 0.008; adjusted hazard ratio [HR]: 0.38; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.18 to 0.83) (19). No significant difference in mortality with revascularization was observed in lower-risk patients without high-risk CAD. Finally, in a propensity-matched study of 1,866 patients in New York State with SIHD undergoing cardiac catheterization, PCI compared with MT was associated with reduced 4-year rates of death or MI (16.5% vs. 21.2%; adjusted HR: 1.49; 95% CI: 1.16 to 1.93) (20). Although not randomized, these real-world studies included higher-risk patients than the COURAGE and BARI 2D trials (8,9), and with many more events had substantially greater power to detect reductions in death and MI between treatments.

FIGURE 1. Propensity-Matched Analysis in 39,131 Canadian Patients With SIHD Undergoing Early Revascularization (n = 23,992) or Treated Conservatively (n = 15,139).

Over 4 years of follow-up, significant reductions in death (A) and myocardial infarction (B) were observed with revascularization. Adapted with permission from Wijey sundera et al.(18). CI = confidence interval; HR = hazard ratio; SIHD = stable ischemic heart disease.

These studies reported outcomes with anatomically driven revascularization. Targeting revascularization to lesions causing substantial ischemia may further improve results. The angiogram is a poor discriminator of physiological lesion significance. Many lesions that appear angiographically severe may not produce ischemia, and conversely, ischemia may be present despite a benign angiographic footprint (21,22).

OBSERVATIONAL DATA DEMONSTRATE A STRONG RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN THE EXTENT OF ISCHEMIA AND SUBSEQUENT DEATH AND/OR MI, AND A POSSIBLE BENEFIT FROM REVASCULARIZATION

Most single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) myocardial perfusion imaging studies have demonstrated a strong relationship between the extent of ischemia and prognosis. In 1,137 patients with chest pain or suspected CAD in whom thallium-201 SPECT was performed, a strong graded association was present between the number of abnormal segments and the 6-year rate of cardiac death and MI (23). In a study of 205 patients with angiographically proven CAD, freedom from cardiac death or MI at 10 years was greater in patients with a normal compared with an abnormal thallium-201 SPECT (83% vs. 58%; p = 0.005) (24). In a study of 1,126 asymptomatic patients, the presence of ≥10% ischemia by SPECT was independently associated with death or MI at median follow-up of 6.9 years (HR: 2.67; 95% CI: 1.31 to 5.44; p = 0.007) (25). Among 10,627 patients in whom a quantitative stress SPECT study was performed (671 of whom were treated with early revascularization), the mean 1.9-year rate of cardiac mortality in nonrevascularized patients increased monotonically, from 0.7% in those with no ischemia to 6.7% in those with >20% ischemia (Figure 2) (26). After accounting for baseline variables and the propensity for revascularization, a strong relationship was present between the percentage of myocardial ischemia and cardiac mortality.

FIGURE 2. Cardiac Mortality as a Function of Total Ischemic Myocardium at a Mean Follow-Up Time of 1.9 ± 0.6 Years.

Cardiac mortality as a function of total ischemic myocardium is shown at a mean follow-up time of 1.9 ± 0.6 years in 10,627 patients at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center without previous myocardial infarction or revascularization who underwent exercise or adenosine thallium 201 single-photon emission computed tomography myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Outcomes are shown according to whether elective revascularization was versus was not performed within 60 days. Patients with a greater percentage of ischemic myocardium had a greater survival benefit with revascularization. (A) Unadjusted analysis. (B) Log hazard ratio of cardiac mortality for revascularization versus medical therapy as a function of % ischemic myocardium from a Cox proportional hazards regression model. *p < 0.001. Adapted with permission from Hachamovitch et al. (26).

In the COURAGE serial nuclear substudy, 314 patients underwent rest/stress SPECT before treatment and at 6 to 18 months (mean 374 ± 50 days), with the amount of ischemia assessed at a blinded core laboratory (27). A strong graded relationship was present between the amount of residual ischemia on the 6- to 18-month test and subsequent death or MI (p = 0.001), which was attenuated after adjustment for baseline variables and treatment (p = 0.09). Similarly, long-term freedom from death or MI was greater in patients achieving versus not achieving ≥5% reduction in ischemia (whether attained by PCI or OMT alone), especially in those with at least moderate (≥10%) ischemia at baseline. Of note, PCI resulted in a substantial reduction in quantitative ischemia from the baseline to the follow-up SPECT study (8.2% vs. 5.5%; p < 0.0001). By contrast, despite excellent compliance with GDMT in the COURAGE trial, no reduction in ischemia from baseline to follow-up occurred with MT (8.6% vs. 8.1%; p = 0.93) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3. Reduction in Inducible Ischemia From Baseline to 6 to 18 Months.

Reduction in inducible ischemia from baseline to 6 to 18 months is shown in patients treated with OMT with versus without a strategy of routine upfront PCI, as assessed by myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Left graph: with routine upfront PCI; right graph: without. The reduction in ischemia in the PCI arm was significant, whereas there was no significant reduction in ischemia with OMT. Adapted with permission from Shaw et al. (27). CI = confidence interval; OMT = optimal medical therapy; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

The adverse prognostic implications of ischemia have been observed with other noninvasive imaging techniques and with invasive physiological lesion assessment. Among 7,061 patients at 4 centers in whom a clinically indicated rest/stress rubidium-82 positron emission computed tomography was performed, the adjusted risk of cardiac death at a median follow-up of 2.2 years increased 84% for each 10% of ischemic myocardium (p < 0.0001) (28). In another study, stress echocardiography was performed in 14,140 patients at 2 Italian institutions (29). At median 2.5-year follow-up, the presence of ischemia was a strong independent predictor of mortality in both diabetic patients (HR: 1.71; 95% CI: 1.34 to 2.18; p < 0.0001) and nondiabetic patients (HR: 1.54; 95% CI: 1.32 to 1.80; p < 0.0001). Finally, identification of hemodynamically significant flow-limiting lesions during hyperemia with adenosine in the cardiac catheterization laboratory (fractional flow reserve [FFR]) has been correlated with death and MI in medically treated patients. In a collaborative meta-analysis, the rates of death or MI and major adverse cardiac events (MACE) were inversely related to FFR at a median 16-month follow-up (Figure 4) (30).

FIGURE 4. Relationship Between FFR and 1-Year MACE According to Whether or Not Revascularization Was Performed.

(A) Study-level meta-regression in 8,418 patients from 90 cohorts. Revascularization was associated with a lower rate of MACE when the FFR was <0.75 in an unadjusted random effects model, and <0.90 in an adjusted model. (B) Patient-level meta-analysis in 5,979 patients. Revascularization was associated with a lower rate of MACE when the FFR was <0.67 in an unadjusted Cox model, and <0.76 in an adjusted model. Reprinted with permission from Johnson et al. (30). CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; FFR = fractional flow reserve; MACE = major adverse cardiac events; MI = myocardial infarction; PCI = percutaneous coronary intervention.

Observational studies further support the potential role of routine revascularization to improve prognosis in patients with moderate or severe ischemia. In a propensity-controlled multivariable analysis from Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, 2-year rates of cardiac death were lower with revascularization within 60 days in patients with moderate or severe ischemia (cutoff ~12.5% of the left ventricle) by SPECT (Figure 2) (26). In a subsequent investigation from the same center in 13,969 patients with a mean 8.7-year follow-up, early revascularization in patients with ≥10% inducible ischemia by SPECT was associated with improved late survival, unless a large fixed defect was present (31). Early revascularization in patients with ≥10% myocardial ischemia was associated with improved survival, even in those ≥75 years of age (32). In a Mayo Clinic study, a survival benefit among diabetic patients with CABG compared with MT or PCI was noted only in those with a high-risk SPECT scan (33). Finally, in an adjusted study-level meta-regression of 90 cohorts in which FFR was assessed, revascularization was associated with a lower 1-year rate of death or MI when FFR was <0.90 (30).

RANDOMIZED TRIAL DATA SUGGEST REVASCULARIZATION IS SAFE AND REDUCES DEATH AND/OR MI AND/OR IMPROVES QoL, ESPECIALLY WHEN SUBSTANTIAL ISCHEMIA IS PRESENT

In the MASS II trial (Medicine, Angioplasty or Surgery Study), 611 patients with proximal multivessel disease and documented ischemia were randomly assigned to CABG, PCI, or OMT (34). The 10-year mortality rates in the 3 groups were 25.1%, 24.9%, and 31.0%, respectively (p = 0.09). The 10-year MI rates were 10.3%, 13.3%, and 20.7%, respectively (p < 0.01). Freedom from angina at 10 years was 64% with CABG, 59% with PCI, and 43% with OMT (p < 0.001).

In the COURAGE trial, randomization of 2,287 patients to PCI plus OMT versus OMT alone did not reduce the long-term rate of death or MI (8). Nor, however, did PCI worsen prognosis, and crossover to PCI for progressive symptoms or ACS was required in 32% of OMT patients during a median 4.6-year follow-up. Moreover, patients randomized to PCI had less documented angina, were more likely to be angina-free (despite requiring fewer nitrates and calcium-channel blockers), and had improved QoL for up to 3 years (8,35). The reduction in angina (assessed by the Seattle Angina Questionnaire) with PCI versus OMT was most evident in those with the greatest level of baseline angina (35).

In the BARI 2D trial, 2,368 patients with type 2 diabetes (90% with SIHD) were randomized to prompt revascularization with intensive MT or to intensive MT alone, with randomization stratified by intended PCI versus CABG (9). The 5-year rates of death (the primary endpoint) and MACE (death, MI, or stroke) were not significantly different with either strategy. However, patients in the CABG stratum had more advanced CAD (including more triple-vessel and proximal left anterior descending coronary artery disease) than those in the PCI stratum, and patients randomized to CABG versus intensive MT had lower 5-year rates of MACE (22.4% vs. 30.5%; p = 0.01), driven by less MI (7.4% vs. 14.6%). In patients with less extensive CAD, there was no difference in MACE with PCI versus intensive MT. Compared with intensive MT, prompt revascularization resulted in significantly greater freedom from angina for up to 4 years (36). Most measures of QoL through the 4-year follow-up were also improved with routine revascularization compared with intensive MT only (37), and revascularization was ultimately required in 42% of MT patients during follow-up (9).

Meta-analyses have also shown reduced mortality and greater angina relief with early routine revascularization versus MT. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials comparing PCI versus MT in 7,182 SIHD patients, Pursnani et al. (38) found a strong trend for lower mortality with PCI (risk ratio [RR]: 0.85; 95% CI: 0.71 to 1.01; p = 0.07). Others have reported similar trends (39,40). From 17 trials of PCI versus OMT in 7,513 stable patients with ischemia (some with recent MI), Schömig et al. (41) reported that PCI was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality (odds ratio [OR]: 0.80; 95% CI: 0.64 to 0.99). Jeremias et al. (42) performed the largest meta-analysis to date from 28 trials of revascularization versus MT in 13,121 patients with nonacute CAD. Revascularization was associated with a reduction in mortality (OR: 0.74; 95% CI: 0.63 to 0.88), a difference that was significant for both CABG (OR: 0.62; 95% CI: 0.50 to 0.77) and PCI (OR: 0.82; 95% CI: 0.68 to 0.99). PCI was also associated with greater freedom from angina compared with MT in a meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials in SIHD (RR: 1.20; 95% CI: 1.06 to 1.37), a benefit that was present at follow-up durations ≤1 year, 1 to 5 years, and ≥5 years (38).

Of note, bare-metal stents (BMS) were used in most PCI versus MT trials to date (including the MASS II, COURAGE, and BARI 2D studies). First-generation drug-eluting stents (DES) markedly reduce recurrent ischemia compared with BMS (43), resulting in fewer hospitalizations for repeat revascularization (44). Compared with BMS and first-generation DES, second-generation DES may further reduce death and MI, and enhance event-free survival (39,45,46). In a comprehensive network meta-analysis of revascularization versus MT in SIHD in which stent type was considered (100 trials, 93,553 patients, 262,090 patient-years of follow-up), PCI with everolimus-eluting stents compared with MT was associated with significant 25%, 22%, and 73% reductions in death, death or MI, and repeat revascularization, respectively (Figure 5) (47). Similar benefits were noted with CABG compared with MT, and in analyses that excluded trials of patients with recent MI or stabilized ACS.

FIGURE 5. Network Meta-Analysis Comparing Different Revascularization Modalities With MT.

Estimated risk rate ratios (95% credible intervals) are shown for death, MI, and the composite of death or MI. Compared with MT, a reduction in death was observed with EES, R-ZES, and CABG; a reduction in MI was observed with CABG; and a reduction in the composite of death or MI was observed with EES and CABG. Adapted with permission from Windecker et al. (47). BMS = bare-metal stent(s); CrI = credible interval; EES = everolimus-eluting stent(s); E-ZES = fast-release zotarolimus-eluting stent(s); MT = medical therapy; PES = paclitaxel-eluting stent(s); PTCA = percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty; R-ZES = slow-release zotarolimus eluting stent(s); SES = sirolimus-eluting stent(s); other abbreviations as in Figure 4.

Outcomes may be further improved by a routine revascularization strategy in patients with more extensive ischemia. Only ~33% of patients in COURAGE had at least moderate (≥10%) ischemia at baseline, either measured quantitatively (27) or site assessed (48); ~40% of patients had <5% ischemia (27). Ischemia, as evidenced by FFR, may predict which patients and lesions are likely to benefit from routine revascularization versus GDMT alone. In the DEFER trial, 91 patients with FFR >0.75 were randomized to balloon angioplasty versus MT (49). The 2-year rates of death, MI, or repeat revascularization were similar in the deferral and PCI groups (89% vs. 83%, respectively). In the FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation) trial, FFR was performed in 1,005 patients with multivessel disease undergoing PCI with first-generation DES. Patients were randomized to treatment of all angiographically significant lesions, versus only lesions with FFR ≤0.80. Compared with anatomically based revascularization, FFR-guided PCI resulted in lower rates of the primary endpoint of death, MI, or repeat revascularization at 1 year (13.2% vs. 18.3%; p = 0.02), and of death or MI at 2 years (8.4% vs. 12.9%; p = 0.02) (50,51). These data, consistent with earlier observational studies, suggest that the prognosis of non-ischemia-producing lesions without revascularization is favorable.

By contrast, the FAME-2 trial demonstrated worse outcomes with an initial MT approach in flow-limiting lesions. In the FAME-2 trial, 888 of a planned 1,632 patients with SIHD and 1 or more lesions with an FFR ≤0.80 (i.e., ischemia) were randomized to PCI with second-generation DES plus GDMT versus GDMT alone (52). The trial was stopped early because of excess events in the GDMT arm. The 2-year primary endpoint of death, MI, or urgent revascularization occurred in 8.1% of PCI patients versus 19.5% of GDMT patients (HR: 0.39; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.57; p < 0.001), driven by fewer urgent revascularizations (4.0% vs. 16.3%; p < 0.001), including those triggered by MI or severe unstable angina (3.4% vs. 7.0%; p = 0.01). Class II to IV angina was also significantly more frequent in the GDMT arm during follow-up, and PCI was required in 40.6% of GDMT-assigned patients within 2 years for refractory symptoms or ACS. Although there was no significant difference in the composite rate of death or MI, landmark analysis showed that periprocedural MI rates were increased with PCI, whereas MI occurred less frequently in the PCI group compared with the GDMT group between 8 days and 2 years. Similarly, in a meta-analysis of 12 randomized trials of PCI versus OMT with 37,548 patient-years of follow-up, PCI compared with MT was associated with a significant 23% reduction in spontaneous MI, which paralleled a trend toward reduced mortality (53). Spontaneous MI has been strongly associated with subsequent mortality, whereas most periprocedural MIs are not clinically relevant (54).

Finally, because most periprocedural MIs do not have major clinical consequence (54), their inclusion in a primary composite death or MI endpoint of prior trials may have statistically masked an isolated mortality benefit of revascularization in SIHD patients with documented ischemia. Three randomized trials of PCI versus MT in SIHD have been performed in which 1,557 patients had evidence of ischemia on noninvasive stress imaging or FFR before randomization (the COURAGE baseline nuclear substudy, the FAME-2 study, and the SWISSI [Silent Ischemia After Myocardial Infarction] II trial [which enrolled stabilized patients after acute MI]) (48,52,55). In a meta-analysis of these 3 trials, routine PCI compared with MT was associated with lower 3-year mortality (HR: 0.52; 95% CI: 0.30 to 0.92; p = 0.02), with no heterogeneity between studies (56).

MEDICATION DISUTILITY AND PATIENT PREFERENCE

Adherence to biology-altering medications, such as aspirin and statins, reduces death and MI in SIHD patients treated with or without revascularization (1,2,57). In addition to potentially improving prognosis, routine revascularization reduces the requirement for antianginal medications, as observed in the COURAGE trial (8). Recent studies have emphasized the cost and inconvenience (disutility) to the patient of taking medications. Participants of 2 large surveys were willing to sacrifice 4 and 6 months of life, respectively, to avoid taking a daily pill (58,59). A meta-analysis from 20 studies and 376,162 patients examining usage of 7 drug classes that prevent cardiovascular disease reported average 2-year adherence rates of 50% for primary prevention and 66% for secondary prevention, with few differences between drug classes (60). Recent reports have emphasized the importance of patient-centered care and shared decision making, taking into account patient goals and preferences when choosing between therapies, especially when the prognosis of alternative approaches are roughly similar (61). Beyond considerations of whether revascularization reduces death and MI in SIHD, many patients favor the more immediate reduction in symptoms achievable with PCI and CABG, and avoidance of antianginal medications.

Finally, as the disutility of taking medications increases with the number of daily pills, reducing the requirement for antianginal medications may facilitate compliance with GDMT that reduces MI and death, such as statins. Revascularization may serve as a “wake-up call” to patients, and stimulate compliance with secondary prevention. In fact, GDMT adherence may be increased after PCI, compared with more conservative care (62).

THE CASE FOR INITIAL GDMT IN PATIENTS WITH SIHD AND ISCHEMIA

OVERVIEW

GDMT should be initiated in all SIHD patients, whether or not revascularization is performed. GDMT consists of lifestyle and pharmacological interventions that lower the risk of death and MI; revascularization is not a substitute for this. Although revascularization might be considered a reasonable alternative to antianginal medications to treat angina, disease-modifying medications are still necessary to improve survival (Figure 6) (57,63). Comprehensive risk factor control, although not commonly achieved, is associated with a 50% reduction in mortality over 5 years in SIHD patients with diabetes, with or without revascularization (64). Adherence to GDMT following revascularization in the SYNTAX (Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery) trial was suboptimal in the PCI group, and even worse in the CABG group (57). Clearly, strategies are required to improve GDMT adherence, whether or not early revascularization is performed.

FIGURE 6. Effect of OMT on Clinical Outcomes in Patients Undergoing PES Implantation and CABG in the SYNTAX Trial.

OMT significantly lowered the risk of death throughout the 5-year follow-up. In a Cox regression model, OMT as a time-dependent covariate was independently associated with improved survival throughout follow-up both in PCI patients (HR: 0.70; 95% CI: 0.48 to 0.998) and CABG patients (HR: 0.65; 95% CI: 0.49 to 0.86; pinteraction = 0.44). Adapted with permission from Iqbal et al. (57). SYNTAX = Synergy Between Percutaneous Coronary Intervention With TAXUS and Cardiac Surgery; other abbreviations as in Figures 1, 3, 4, and 5.

Recent studies suggest that, in the contemporary GDMT era, the extent of ischemia is not related to the risk of death or MI in patients with SIHD, and that revascularization does not improve prognosis, regardless of the extent of ischemia. If true, then the only reason to routinely revascularize SIHD patients would be to improve QoL. If an initial trial of GDMT does not increase the risk of death or MI, it is difficult to justify revascularization in patients with absent or mild symptoms not treated with anti-anginal therapy, because all procedures have inherent risks. Furthermore, as MT improves and event rates decrease, possible early harm from routine revascularization–death, MI, and stroke– become relatively more important in weighing the potential benefits and risks of performing PCI or CABG.

OBSERVATIONAL DATA SUGGEST THE EXTENT OF ISCHEMIA IS NOT RELATED TO DEATH AND MI IN THE CONTEMPORARY GDMT ERA

In the COURAGE serial nuclear substudy, a strong relationship was found between the extent of core laboratory-assessed residual ischemia at 6 to 18 months and subsequent death or MI in 314 patients, but this was not significant after multivariable adjustment (27). This sub-study included ~14% of enrolled patients and may not be representative of the entire COURAGE population. Although there was a signal that ischemia reduction was associated with better outcomes, and that PCI was associated with a greater degree of ischemia reduction than OMT, the critical link of whether PCI was causally associated with fewer cardiac events was not analyzed. Thus, this substudy was underpowered and hypothesis-generating. In a separate, larger COURAGE report, in which site investigators evaluated the extent of ischemia in 1,381 patients with baseline SPECT imaging, no significant relationship was present between the rates of death and MI in those with ≥3 versus <3 ischemic segments (Figure 7) (48). In a follow-up COURAGE core laboratory study in 621 patients, the extent of baseline ischemia did not correlate with the rate of death, MI, or ACS after a mean follow-up of 4.7 years, whereas the angiographic extent of atherosclerosis correlated with events (Figure 8) (65). These COURAGE trial analyses assessed death and MI rates differently. In the serial nuclear substudy, outcomes after repeat SPECT did not include events between randomization and 6 to 18 months, or events in patients who did not return for the follow-up stress test, and events were not reported according to treatment group. By contrast, in the substudies that evaluated prognosis using baseline ischemia, all events during follow-up were ascertained, and event rates were reported according to treatment group.

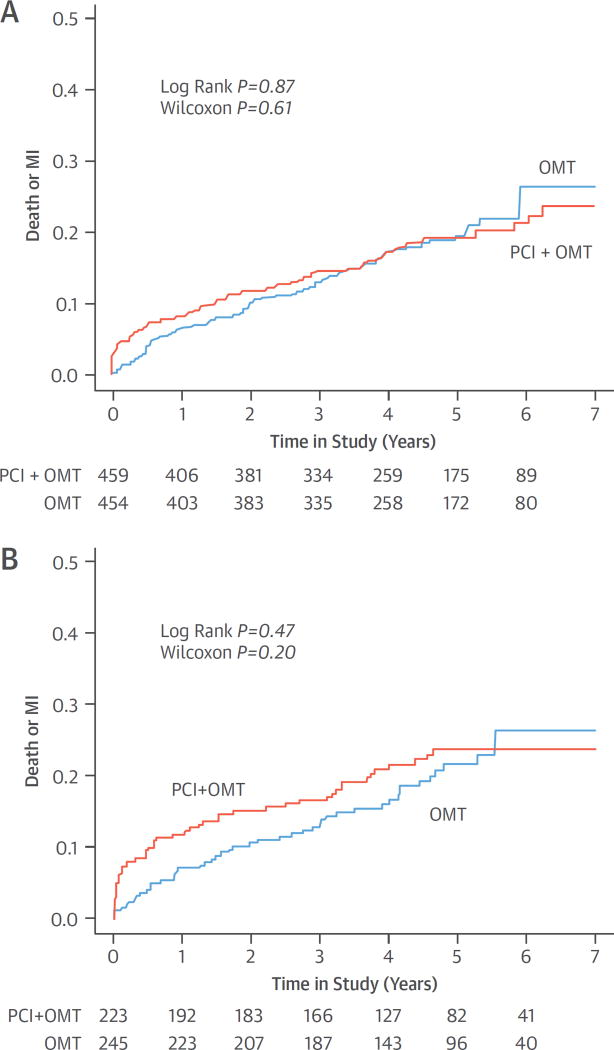

FIGURE 7. Baseline Severity of Ischemia and Outcomes by Treatment Group in the COURAGE Trial.

Cumulative rates of all-cause death or MI are shown according to randomized treatment assignment in patients with no-to-mild ischemia and moderate-to-severe ischemia on myocardial perfusion imaging at baseline in the COURAGE (Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation) trial. (A) No-to-mild ischemia. (B) Moderate-to-severe ischemia. Ischemia severity was determined by the participating sites, and was not associated with risk of death or MI. PCI did not reduce death or MI in patients with moderate or severe ischemia. Adapted with permission from Shaw et al. (48). Abbreviations as in Figures 3 and 4.

FIGURE 8. Ischemia Severity, Anatomic Burden, and Outcomes in COURAGE.

Freedom from death, MI, or NSTE-ACS is shown by percent ischemic myocardium and burden of angiographic atherosclerosis. (A) Percent ischemic myocardium. (B) Burden of angio-graphic atherosclerosis. The number of patients pertaining to each colored curve is shown per year of follow-up. The Cedars-Sinai Nuclear Core Laboratory determined the percent ischemic myocardium at baseline. Atherosclerotic burden was determined by a custom score, accounting for the number and specific diseased coronary arteries, and proximal versus nonproximal location. Ischemic burden was not associated with events, in contrast to anatomic burden, which was. PCI did not reduce the event rate in patients with high ischemic or anatomic burden. Adapted with permission from Mancini et al. (65). NSTE-ACS = non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome; other abbreviations as in Figures 3, 4, and 7.

Other recent studies have also failed to demonstrate a link between ischemia and prognosis. In a post-hoc analysis from the BARI 2D trial, the prognostic impact of SPECT performed 1 year after randomization was examined in 1,505 patients, as assessed by a core laboratory (66). Increasing severity of ischemia did not predict greater risk of death or cardiovascular events. In an observational study, Cleveland Clinic investigators compared survival of asymptomatic patients with previous revascularization and documented ischemia on SPECT 5 years after the initial revascularization with a mean 5.7-year follow-up. The severity of ischemia was not associated with all-cause death, regardless of whether early repeat revascularization was performed or MT continued (67). In the STICH (Surgical Treatment for IsChemic Heart Failure) trial of CABG versus MT in SIHD patients with left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) ≤35%, at a median follow-up of 4.7 years, the presence of inducible ischemia at baseline did not identify patients with a worse prognosis (68). The CLARIFY (Prospective Observational Longitudinal Registry of Patients With Stable Coronary Artery Disease) registry enrolled 32,105 outpatients with prior MI, of whom 20,291 had undergone a noninvasive test for ischemia within 12 months of enrollment (69). Anginal symptoms (with or without ischemia), but not silent ischemia, were associated with an increased 2-year rate of cardiovascular death or MI. These studies, performed in an era of more intensive MT, are distinct from earlier reports in which strong associations between ischemia and outcomes were observed.

RANDOMIZED TRIALS SUGGEST REVASCULARIZATION DOES NOT REDUCE DEATH OR MI, EVEN IF ISCHEMIA IS PRESENT, AND DOES NOT PRODUCE A DURABLE IMPROVEMENT IN QoL

In the COURAGE trial, after a median 4.6-year follow-up, there was no significant difference between PCI plus OMT versus OMT alone in the primary endpoint of death or MI (19.0% vs. 18.5%, respectively; HR: 1.05; 95% CI: 0.87 to 1.27; p = 0.62) (8). Although high-risk subgroups were identified, none had an improved prognosis with PCI. Similarly, in the BARI 2D study, 5-year survival rates in type 2 diabetic patients did not differ significantly between the revascularization and MT groups (88.3% vs. 87.8% respectively; p = 0.97); MACE rates were also similar (77.2% vs. 75.9% respectively; p = 0.70) (9). A lower rate of MI was reported in the BARI 2D CABG stratum with revascularization compared with MT, although CABG-related MI was not ascertained, and this subgroup finding should be considered hypothesis-generating. BARI 2D patients who achieved excellent risk factor control had one-half the death rate of those with poor risk factor control (64).

Meta-analyses of SIHD strategy trials that exclude patients with recent ACS do not support a difference in prognosis between routine revascularization and MT only. Before the COURAGE trial, Katritsis and Ioannidis (70) performed a meta-analysis of 11 randomized trials with 2,950 patients comparing PCI (with balloon angioplasty or BMS) to conservative treatment. PCI did not reduce the rates of death or MI. Addition of the results from the COURAGE trial to this meta-analysis did not alter the estimate of PCI on mortality (71). Schömig et al. (41) reported, in a meta-analysis of 17 trials, that PCI was associated with a significant reduction in all-cause mortality. However, in 4 trials, patients were treated with CABG as well as PCI, 1 trial included patients with MI within 3 months, and 4 trials included MI patients within 4 weeks. If the studies that included CABG and recent MI patients are excluded from the analysis, a significant mortality difference between PCI and medical therapy is no longer present (OR: 0.91; 95% CI: 0.74 to 1.12). Trikalinos et al. (72) performed a network meta-analysis of 61 randomized trials (n = 25,388) comparing balloon angioplasty, BMS, and DES with each other and with MT in SIHD. None of the PCI modalities was associated with reduced death or MI. The RR for comparisons between DES and MT was 0.96, (95% CI: 0.60 to 1.52) for death, and 1.15 (95% CI: 0.73 to 1.82) for MI. Stergiopoulos et al. (73) performed a meta-analysis of the subset of patients from 5 SIHD strategy trials (5,286 patients) in which stents and statins were used in more than 50% of patients, with ischemia diagnosed by stress testing or FFR. There were no significant differences in event rates for PCI plus GDMT versus GDMT alone for death or nonfatal MI, respectively (Figure 9). By contrast, early randomized trials (before the establishment of current standards for secondary prevention) demonstrated reduced rates of death, MI, and ACS with CABG compared with MT in patients with ischemia (7,34). For example, in the MASS II study, 1-year usage rates of aspirin (77%), statins (63%), beta-blockers (58%), and angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (27%) were substantially less than in recent strategy trials (74).

FIGURE 9. Meta-Analysis of PCI and MT Versus MT Alone in Patients With Documented Myocardial Ischemia.

(A) Death. (B) Nonfatal MI. This meta-analysis required 50% statin use and only included studies of SIHD that directly compared the 2 randomized groups. The addition of PCI to MT did not reduce the incidence of death or MI as compared with MT alone. Adapted with permission from Stergiopoulos et al. (73). OR = odds ratio; other abbreviations as in Figures 3, 4, and 5.

Recent randomized trials with greater use of secondary prevention measures have not shown a reduction in death or MI after PCI or CABG in patients with documented ischemia. In a COURAGE trial analysis of 1,381 patients, including 468 with at least moderate ischemia on site-interpreted SPECT studies, PCI was not associated with a reduction in the 5-year rate of death or MI (48) (Figure 7). Similarly, in a separate COURAGE substudy of 621 patients with core laboratory–interpreted SPECT data, ischemic burden at baseline did not predict cardiovascular events, nor did it identify a subgroup with an improvement in prognosis after PCI (65). Although the extent of atherosclerosis was associated with the composite endpoint of death, MI, or ACS in this study (Figure 8), there was no benefit from PCI across the spectrum of disease. In the BARI 2D SPECT substudy, a greater extent of ischemia 1 year after randomization did not predict reduced death or cardiovascular events from revascularization (66). In the STICH trial, inducible ischemia did not identify patients with benefit from CABG compared with MT in patients with reduced LVEF (68). In the FAME-2 trial, FFR-guided PCI did not significantly reduce the 2-year risk of death or MI compared with MT (52). FAME-2 reported an increase in periprocedural MI (defined by stringent criteria that required ≥10× creatine kinase-myocardial band [CK-MB] elevation or new Q waves with ≥5-fold CK-MB elevation), but a reduction in spontaneous MI with PCI compared with GDMT between 8 days and 2 years. In light of recent evidence that prolonged dual antiplatelet therapy (which is more likely to be used after PCI than MT) reduces spontaneous MI and the composite rate of cardiovascular death, MI, and stroke (75,76), the extent to which late benefits of PCI in FAME-2 and reductions of death and MI in some meta-analyses with PCI (53) are attributable to dual antiplatelet therapy, rather than revascularization, is uncertain.

The impact of revascularization on angina-related QoL has more evidence to support its practice, although its effects are time-limited, and intensive MT results in a high proportion of patients becoming angina-free. In the COURAGE trial, using the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, patients randomized to PCI reported greater freedom from angina for 24 months after the procedure (35). In the BARI 2D study, greater freedom from angina with revascularization compared with intensive MT lasted beyond 1 year only in the CABG stratum (36). Finally, a report from 10 randomized trials of PCI versus MT in 6,762 patients with SIHD found no difference in angina relief between the 2 approaches at the end of study follow-up (RR: 1.10; 95% CI: 0.97 to 1.26) (40). The incremental benefit of PCI observed in older trials (OR: 3.38; 95% CI: 1.89 to 6.04) was substantially less or absent in recent trials (OR: 1.13; 95% CI: 0.76 to 1.68), possibly due to greater use of evidence-based therapies. It should also be recognized that a challenge in the assessment of QoL in all of these trials is the placebo effect, given the absence of sham PCI/CABG procedures in the comparator groups.

COST-EFFECTIVENESS AND INFORMED CONSENT

The cost-effectiveness of routine revascularization in SIHD must be considered. If revascularization does not reduce cardiovascular death or MI when added to GDMT, it is difficult to justify the cost of revascularization for asymptomatic patients or those with mild symptoms who have not had a trial of anti-anginal therapy. Furthermore, if revascularization improves QoL (but does not reduce death or MI), patients and payers should understand what it costs to buy a period of freedom from angina.

In the COURAGE trial, the addition of PCI to OMT was not cost-effective (77). The added cost of PCI was approximately $10,000, without significant gain in life-years or quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio varied from just over $168,000 to just under $300,000 per life-year or QALY gained with PCI. In the BARI 2D study, cost-effectiveness also favored MT over prompt revascularization (78). Lifetime projections of cost-effectiveness found MT to be cost-effective ($600 per life-year added) compared with PCI, but suggested that CABG may be cost-effective ($47,000 per life-year added). In the FAME-2 trial, the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio of PCI was $36,000 per QALY (79), and the authors concluded that PCI was economically attractive compared with the best available MT. However, this analysis was limited, because 12-month QoL data was available for only 11% of patients in the economic substudy.

In the era of patient-centered care, patients should be educated regarding the potential risks and benefits of undergoing versus not undergoing revascularization. Interviews of patients suggest that they are not truly knowledgeable after receiving “informed consent” for elective PCI. Rothberg et al. (80) found that most patients believe elective PCI will prevent death or MI. Better informed patients are less likely to choose angiography and possible PCI (81). Decision support tools are needed to assess procedural risk and educate patients about the probability of death or MI and improved QoL with or without PCI or CABG. Part of the challenge is that providers are not skilled at explaining risks in probabilistic terms to patients. Providers need training to accurately and effectively communicate potential risks and benefits to patients.

ANALYSIS, DATA GAPS, AND FUTURE DIRECTIONS

ACKNOWLEDGING EQUIPOISE

Credible observational data support the position that ischemia is a predictor of adverse events, or alternatively, the position that systemic inflammation and thrombosis of vulnerable plaques (either with or without ischemia) are responsible for most cases of cardiovascular death, MI, and ACS (82,83). The optimal approach to patients with SIHD remains unsettled because all prior randomized trials, either by design or execution, have limitations. Indeed, varying COURAGE nuclear substudy results can be used to support either routine revascularization or a more conservative approach. Similarly, the case can be made from large-scale observational studies and randomized trial substudy data that either initial strategy is appropriate. The strengths and limitations of randomized trials versus observational studies must be weighed. For example, death and MI was not reduced in 2,287 patients with SIHD randomized to PCI plus OMT versus OMT in the randomized COURAGE trial (8), but revascularization (PCI or CABG) compared with MT was associated with reduced death and MI among 9,676 propensity-matched “real-world” patients meeting COURAGE eligibility criteria (18). Are these discordant results explained by residual confounding in the observational study analysis (e.g., factors contributing to patient unsuitability for revascularization after cardiac catheterization), by the inclusion of a higher-risk population, revascularization by CABG, as well as PCI, and more endpoints yielding greater power to elicit differences between the groups, or by better MT in the clinical trial setting? Frequent crossovers in strategy trials, although arguably representing an essential aspect of each approach, reduce power to demonstrate differences. For example, in the STICH trial, CABG reduced mortality in both the per-protocol and crossover patient populations (although whether ischemia was a modulating influence in these cohorts was not reported) (84). It should also be acknowledged that the risk profile of patients with SIHD may vary greatly, independent of the degree of ischemia, and that optimal tools for risk stratification are lacking.

When data are conflicting or individual trials are underpowered, meta-analysis is often relied upon to provide a consensus direction. However, the results of meta-analyses may vary tremendously, depending on the studies selected for inclusion. For example, some meta-analyses included patients with recent MI; others did not. Meta-analyses share the limitations of their component trials, and have other drawbacks that may not be immediately obvious. For example, in the 100-trial network meta-analysis of revascularization versus MT (47), only 15 trials had a MT arm that reported all-cause mortality. Most of the conclusions from this study were thus drawn from indirect comparisons across studies, and should be considered hypothesis-generating. Moreover, patient-level data were not available, and thus comparisons were unadjusted. Numerous confounders were likely present, which varied between studies, including differences in baseline patient and lesion characteristics, and the type of and adherence to GDMT and other pharmacotherapies. Endpoint definitions, such as periprocedural MI, varied between studies. Subgroup analysis was not possible, and outcomes according to the extent of CAD and ischemia are undetermined. In addition, these studies were performed over several decades, and controlling for evolution in general medical practice is not possible. Indeed, many of these studies are of questionable relevance to contemporary practice, given advances in GDMT and revascularization techniques and devices. These and other factors likely explain why many of the 16 meta-analyses described in the present report reached diametrically opposite conclusions.

Beyond death and MI, the extent to which revascularization incrementally improves QoL may also be debated, and the frequency and importance of revascularization-related complications, as well as the impact of drug-related side effects on QoL and adherence must be considered. And although both emphasize the central role of GDMT in all patients with SIHD, current U.S. and European guidelines differ regarding the strength of the evidence for revascularization in SIHD, and the relative weight that should be accorded to anatomy versus ischemia when considering whether revascularization is useful (10–13) (Table 2). Reasonable physicians may variably evaluate the strength of the evidence presented herein; thus, a lucid argument can be made for either management approach, emphasizing the importance of shared decision making between the treating cardiologist, the referring physician, and the patient. Thus, despite strongly held individual beliefs, the overall balance of data supporting each approach reflects a state of “community equipoise” (85). Exemplifying this equipoise, only 35% to 65% of SIHD patients with documented moderate or severe ischemia undergo cardiac catheterization within 90 days (86,87).

TABLE 2.

Current Guideline Indications for Revascularization in SIHD

| To Improve Survival

|

To Improve Symptoms

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Class of Recommendation |

Level of Evidence |

Class of Recommendation |

Level of Evidence |

|

| 2012/2014 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guidelines (10,11) | ||||

| Left main disease | ||||

| CABG | I | B | – | – |

| PCI | IIa, IIb or III* | B or C* | – | – |

| 3-vessel disease | ||||

| CABG | I | B | – | – |

| PCI | IIb | B | – | – |

| 2-vessel disease with PLAD disease | ||||

| CABG | I | B | – | – |

| PCI | IIb | B | – | – |

| 2-vessel disease without PLAD disease | ||||

| CABG | IIa | B | – | – |

| CABG | IIb | C | – | – |

| PCI | IIb | B | – | – |

| 1-vessel disease with PLAD disease | ||||

| CABG | IIa | B | – | – |

| PCI | IIb | B | – | – |

| 1-vessel disease without PLAD disease | ||||

| CABG | III | B | – | – |

| PCI | III | B | – | – |

| Left ventricular dysfunction | ||||

| CABG | IIa or IIb† | B | – | – |

| CABG | IIb | B | – | – |

| PCI | –‡ | – | ||

| Unacceptable angina despite GDMT‡ | ||||

| PCI or CABG | – | – | I | A |

| PCI | – | – | IIa§ | C |

| CABG | – | – | IIb§ | C |

| Unacceptable angina with GDMT noncompliance or side effects, or patient preference‖ | ||||

| PCI or CABG | – | – | IIa | C |

| 2013/2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines (12,13) | ||||

| Left main disease | I | A | I | A |

| Proximal LAD disease | I | A | I | A |

| Multivessel disease with LVEF <40% | I | B | IIa | B |

| Large area of ischemia (>10% LV) | I | B | I | B |

| Single remaining vessel | I | C | I | A |

| Limiting symptoms or symptoms not responsive/intolerant to GDMT | – | – | I | A |

| Heart failure with >10% ischemia/viability | IIb | B | IIa | B |

| No limiting symptoms with GDMT and with none of the above or with FFR ≥0.80 | III | A | III | C |

Varies according to associated clinical conditions and anatomic complexity.

IIa for LVEF 35% to 50%; IIb for LVEF <35% without left main disease.

Insufficient data for a recommendation.

In patients with prior CABG.

In patients with significant anatomic (>50% left main or >70% non-left main disease) or physiological (FFR <0.80) coronary artery stenoses.

ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS = American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines/American College of Physicians/American Association for Thoracic Surgery/Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association/Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions/Society of Thoracic Surgeons; ESC = European Society of Cardiology; EACTS = European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery; FFR = fractional flow reserve; LAD = left anterior descending coronary artery; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; PLAD = proximal left anterior descending artery; other abbreviations as in Table 1.

An adequately powered, randomized trial of contemporary conservative versus invasive approaches is greatly needed to provide guidance for the optimal approach in patients with SIHD, moderate or severe ischemia, and symptoms that can be controlled with MT. Despite frequently held fervent beliefs favoring either early revascularization or initial GDMT in SIHD, 80% of 499 cardiologists surveyed stated that they would enroll their patients with stable anginal symptoms, >10% myocardial ischemia, and normal LVEF in a randomized trial with a 50% chance of being conservatively managed without cardiac catheterization, provided their patients did not have very high-risk features on stress imaging (88). Following this positive response, the ISCHEMIA trial was formulated.

THE ISCHEMIA TRIAL

The primary aim of the ISCHEMIA trial (NCT01471522) is to determine whether an initial invasive strategy of cardiac catheterization and optimal revascularization (with PCI or CABG, as determined by the local heart team) plus OMT will reduce the primary composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or nonfatal MI in SIHD patients with moderate or severe ischemia and medically controllable or absent symptoms, as compared with an initial conservative strategy of OMT alone, with catheterization reserved for failure of OMT (Central Illustration). The major secondary endpoint is angina-related QoL. Other important secondary endpoints are health resource utilization, costs, and cost-effectiveness. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute is sponsoring the trial, with oversight by a National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–appointed independent data and safety monitoring board. In addition to the main trial, patients with advanced chronic kidney disease (estimated glomerular filtration rate <30 ml/min or on dialysis) are randomized in a parallel substudy. Blinded CCTA is performed before randomization in participants with normal renal function to exclude those with significant left main disease and no obstructive CAD. Enrollment began in late 2012 and is projected to end in 2017. Average follow-up will be approximately 3 years. There are currently ~300 participating sites in more than 30 countries. The ISCHEMIA study thus aims to address limitations of previous strategy trials by: 1) enrolling patients before catheterization, so that anatomically high-risk patients are not excluded; 2) enrolling a higher-risk group with at least moderate ischemia; 3) minimizing crossovers; 4) using contemporary DES and physiologically guided decision making (FFR) to achieve complete ischemic (rather than anatomic) revascularization; and 5) being adequately powered to demonstrate whether routine revascularization reduces cardiovascular death or nonfatal MI in patients with SIHD and at least moderate ischemia.

CENTRAL ILLUSTRATION. Ischemia Revascularization Equipoise: The ISCHEMIA Trial Design.

CCTA may not be performed in participants with estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 ml/min. Participants in whom CCTA shows significant left main disease (≥50% stenosis) or no obstructive disease are excluded. CCTA results are otherwise kept blinded. Cath = catheterization; CCTA = coronary computed tomographic angiography; CKD = chronic kidney disease; eGFR = estimated glomerular filtration rate; OMT = optimal medical therapy; SIHD = stable ischemic heart disease.

The results of the ISCHEMIA trial will have important implications regarding global guidelines for performance and reimbursement of revascularization procedures in patients with SIHD. To date, over 2,000 patients have been randomized, with no safety concerns expressed by the data and safety monitoring board. Given the clear state of community equipoise that exists regarding how best to manage patients with SIHD, it is our hope that primary care providers, cardiologists, and cardiac surgeons around the world will enthusiastically support enrollment of their patients into the ISCHEMIA trial so that we may provide much needed prospective evidence to inform the optimal management of patients with SIHD, substantial myocardial ischemia, and angina symptoms that are controlled or absent.

Acknowledgments

The ISCHEMIA trial, which is discussed in this article, is supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute grant U01HL105907, in-kind donations from Abbott Vascular; Medtronic, Inc., St. Jude Medical, Inc., Volcano Corporation, Arbor Pharmaceuticals, LLC, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, LP, Merck Sharp & Dohme Corp., and Omron Healthcare, Inc.; and by financial donations from Arbor Pharmaceuticals LLC and AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals LP. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Stone is a consultant for Reva Corporation; and as received NIH grant support for the ISCHEMIA trial. Drs. Hochman, Boden, and Maron have received NIH grant support for the ISCHEMIA trial. Dr. Harrington has received consultant fees or honoraria from Amgen Inc., Adverse Events, Daiichi-Lilly, GILEAD Sciences, Janssen, Medtronic, Merck & Co., Novartis, The Medicines Company, Vida Health, Vox Media, and WebMD; has received research grants from AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CSL Behring, Glaxo-SmithKline, Merck & Co., Portola, Regado, Sanofi, and The Medicines Company; has equity in Element Science and MyoKardia; and is an officer, director, or trustee of Evidint and Scanadu.

ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

- ACS

acute coronary syndrome

- BMS

bare-metal stent(s)

- CABG

coronary artery bypass graft

- CAD

coronary artery diseas

- CCTA

coronary computed tomographic angiography

- CI

confidence interval

- DES

drug-eluting stent(s)

- FFR

fractional flow reserve

- GDMT

guideline-directed medical therapy

- HR

hazard ratio

- LVEF

left ventricular ejectio fraction

- MACE

major adverse cardia events

- MI

myocardial infarction

- MT

medical therapy

- OMT

optimal medical therap

- OR

odds ratio

- PCI

percutaneous coronary intervention

- QALY

quality-adjusted life-year

- QoL

quality of life

- RR

risk ratio

- SIHD

stable ischemic heart disease

- SPECT

single-photon emission computed tomography;

Footnotes

All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

References

- 1.Smith SC, Jr, Benjamin EJ, Bonow RO, et al. AHA/ACCF secondary prevention and risk reduction therapy for patients with coronary and other atherosclerotic vascular disease: 2011 update: a guideline from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;58:2432–46. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.10.824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Piepoli MF, Corrà U, Benzer W, et al. Secondary prevention through cardiac rehabilitation: from knowledge to implementation: a position paper from the Cardiac Rehabilitation Section of the European Association of Cardiovascular Prevention and Rehabilitation. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:1–17. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283313592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keeley EC, Boura JA, Grines CL. Primary angioplasty versus intravenous thrombolytic therapy for acute myocardial infarction: a quantitative review of 23 randomised trials. Lancet. 2003;361:13–20. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)12113-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehta SR, Cannon CP, Fox KA, et al. Routine vs selective invasive strategies in patients with acute coronary syndromes: a collaborative meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA. 2005;293:2908–17. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.23.2908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fox KA, Clayton TC, Damman P, et al. Long-term outcome of a routine versus selective invasive strategy in patients with non-ST-segment elevation acute coronary syndrome a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2435–45. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS, et al. American Heart Association Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131:e29–322. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yusuf S, Zucker D, Peduzzi P, et al. Effect of coronary artery bypass graft surgery on survival: overview of 10-year results from randomised trials by the Coronary Artery Bypass Graft Surgery Trialists Collaboration. Lancet. 1994;344:563–70. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)91963-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boden WE, O’Rourke RA, Teo KK, et al. For the COURAGE Trial Research Group. Optimal medical therapy with or without PCI for stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:1503–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa070829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.BARI 2D Study Group. A randomized trial of therapies for type 2 diabetes and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:2503–15. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0805796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. 2012 ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/ American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60:e44–164. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fihn SD, Blankenship JC, Alexander KP, et al. 2014 ACC/AHA/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS focused update of the guideline for the diagnosis and management of patients with stable ischemic heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1929–49. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Montalescot G, Sechtem U, Achenbach S, et al. 2013 ESC guidelines on the management of stable coronary artery disease: the Task Force on the management of stable coronary artery disease of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2013;34:2949–3003. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Windecker S, Kolh P, Alfonso F, et al. 2014 ESC/EACTS guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2014;35:2541–619. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patel MR, Dehmer GJ, Hirshfeld JW, et al. ACCF/SCAI/STS/AATS/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/SCCT 2012 appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization focused update: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Thoracic Surgeons, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, and the Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59:857–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ellis S, Alderman E, Cain K, et al. Prediction of risk of anterior myocardial infarction by lesion severity and measurement method of stenoses in the left anterior descending coronary distribution: a CASS Registry study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1988;11:908–16. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)90044-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Garcia S, Sandoval Y, Roukoz H, et al. Outcomes after complete versus incomplete revascularization of patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: a meta-analysis of 89,883 patients enrolled in randomized clinical trials and observational studies. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1421–31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Head SJ, Mack MJ, Holmes DR, Jr, et al. Incidence, predictors and outcomes of incomplete revascularization after percutaneous coronary intervention and coronary artery bypass grafting: a subgroup analysis of 3-year SYNTAX data. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2012;41:535–41. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezr105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijeysundera HC, Bennell MC, Qiu F, et al. Comparative-effectiveness of revascularization versus routine medical therapy for stable ischemic heart disease: a population-based study. J Gen Intern Med. 2014;29:1031–9. doi: 10.1007/s11606-014-2813-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Min JK, Berman DS, Dunning A, et al. All-cause mortality benefit of coronary revascularization vs. medical therapy in patients without known coronary artery disease undergoing coronary computed tomographic angiography: results from CONFIRM (COronary CT Angiography EvaluatioN For Clinical Outcomes: An InteRnational Multi-center Registry) Eur Heart J. 2012;33:3088–97. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehs315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hannan EL, Samadashvili Z, Cozzens K, et al. Comparative outcomes for patients who do and do not undergo percutaneous coronary intervention for stable coronary artery disease in New York. Circulation. 2012;125:1870–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.071811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tonino PAL, Fearon WF, De Bruyne B, et al. Angiographic versus functional severity of coronary artery stenoses in the FAME study: fractional flow reserve versus angiography in multivessel evaluation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2816–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.11.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Park SJ, Kang SJ, Ahn JM, et al. Visual-functional mismatch between coronary angiography and fractional flow reserve. J Am Coll Cardiol Intv. 2012;5:1029–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vanzetto G, Ormezzano O, Fagret D, et al. Long-term additive prognostic value of thallium-201 myocardial perfusion imaging over clinical and exercise stress test in low to intermediate risk patients: study in 1137 patients with 6-year follow-up. Circulation. 1999;100:1521–7. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.100.14.1521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pavin D, Delonca J, Siegenthaler M, et al. Long-term (10 years) prognostic value of a normal thallium-201 myocardial exercise scintigraphy in patients with coronary artery disease documented by angiography. Eur Heart J. 1997;18:69–77. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.eurheartj.a015120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang SM, Nabi F, Xu J, et al. The coronary artery calcium score and stress myocardial perfusion imaging provide independent and complementary prediction of cardiac risk. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1872–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.05.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hachamovitch R, Hayes SW, Friedman JD, et al. Comparison of the short-term survival benefit associated with revascularization compared with medical therapy in patients with no prior coronary artery disease undergoing stress myocardial perfusion single photon emission computed tomography. Circulation. 2003;107:2900–7. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000072790.23090.41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shaw LJ, Berman DS, Maron DJ, et al. For the COURAGE Investigators. Optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention to reduce ischemic burden: results from the Clinical Outcomes Utilizing Revascularization and Aggressive Drug Evaluation (COURAGE) trial nuclear substudy. Circulation. 2008;117:1283–91. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.743963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorbala S, Di Carli MF, Beanlands RS, et al. Prognostic value of stress myocardial perfusion positron emission tomography: results from a multicenter observational registry. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:176–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.09.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cortigiani L, Borelli L, Raciti M, et al. Prediction of mortality by stress echocardiography in 2835 diabetic and 11305 nondiabetic patients. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015;8:e002757. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.114.002757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Johnson NP, Tóth GG, Lai D, et al. Prognostic value of fractional flow reserve: linking physiologic severity to clinical outcomes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;64:1641–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.07.973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hachamovitch R, Rozanski A, Shaw LJ, et al. Impact of ischaemia scar on the therapeutic benefit derived from myocardial revascularization vs. medical therapy among patients undergoing stress-rest myocardial perfusion scintigraphy. Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1012–24. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hachamovitch R, Kang X, Amanullah AM, et al. Prognostic implications of myocardial perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography in the elderly. Circulation. 2009;120:2197–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.817387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sorajja P, Chareonthaitawee P, Rajagopalan N, et al. Improved survival in asymptomatic diabetic patients with high-risk SPECT imaging treated with coronary artery bypass grafting. Circulation. 2005;112:I311–6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.525022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hueb W, Lopes N, Gersh BJ, et al. Ten-year follow-up survival of the Medicine, Angioplasty, or Surgery Study (MASS II): a randomized controlled clinical trial of 3 therapeutic strategies for multi-vessel coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2010;122:949–57. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.911669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weintraub WS, Spertus JA, Kolm P, et al. For the COURAGE Trial Research Group. Effect of PCI on quality of life in patients with stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:677–87. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dagenais GR, Lu J, Faxon DP, et al. For the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) Study Group. Effects of optimal medical treatment with or without coronary revascularization on angina and subsequent revascularizations in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2011;123:1492–500. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.110.978247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Brooks MM, Chung SC, Helmy T, et al. For the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) Study Group. Health status after treatment for coronary artery disease and type 2 diabetes mellitus in the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes trial. Circulation. 2010;122:1690–9. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.912642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circ CardiovascInterv. 2012;5:476–90. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.112.970954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bangalore S, Toklu B, Amoroso N, et al. Bare metal stents, durable polymer drug eluting stents, and biodegradable polymer drug eluting stents for coronary artery disease: mixed treatment comparison meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6625. doi: 10.1136/bmj.f6625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomas S, Gokhale R, Boden WE, et al. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing percutaneous coronary intervention with medical therapy in stable angina pectoris. Can J Cardiol. 2013;29:472–82. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2012.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schömig A, Mehilli J, de Waha A, et al. A meta-analysis of 17 randomized trials of a percutaneous coronary intervention-based strategy in patients with stable coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:894–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jeremias A, Kaul S, Rosengart TK, et al. The impact of revascularization on mortality in patients with nonacute coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 2009;122:152–61. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2008.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zellweger MJ, Kaiser C, Brunner-La Rocca HP, et al. For the BASKET Investigators. Value and limitations of target-vessel ischemia in predicting late clinical events after drug-eluting stent implantation. J Nucl Med. 2008;49:550–6. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.046771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kirtane AJ, Gupta A, Iyengar S, et al. Safety and efficacy of drug-eluting and bare metal stents: comprehensive meta-analysis of randomized trials and observational studies. Circulation. 2009;119:3198–206. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.826479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Valgimigli M, Sabaté M, Kaiser C, et al. Effects of cobalt-chromium everolimus eluting stents or bare metal stent on fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: patient level meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;349:g6427. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g6427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Palmerini T, Biondi-Zoccai G, Della Riva D, et al. Clinical outcomes with bioabsorbable polymer- versus durable polymer-based drug-eluting and bare-metal stents: evidence from a comprehensive network meta-analysis. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63:299–307. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Windecker S, Stortecky S, Stefanini GG, et al. Revascularisation versus medical treatment in patients with stable coronary artery disease: network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2014;348:g3859. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shaw LJ, Weintraub WS, Maron DJ, et al. Baseline stress myocardial perfusion imaging results and outcomes in patients with stable ischemic heart disease randomized to optimal medical therapy with or without percutaneous coronary intervention. Am Heart J. 2012;164:243–50. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2012.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bech GJ, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. Fractional flow reserve to determine the appropriateness of angioplasty in moderate coronary stenosis: a randomized trial. Circulation. 2001;103:2928–34. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.24.2928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tonino PA, De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, et al. for the FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:213–24. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0807611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pijls NH, Fearon WF, Tonino PA, et al. For the FAME Study Investigators. Fractional flow reserve versus angiography for guiding percutaneous coronary intervention in patients with multivessel coronary artery disease: 2-year follow-up of the FAME (Fractional Flow Reserve Versus Angiography for Multivessel Evaluation) study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:177–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.De Bruyne B, Pijls NH, Kalesan B, et al. For the FAME 2 Trial Investigators. Fractional flow reserve-guided PCI versus medical therapy in stable coronary disease. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:991–1001. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1205361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bangalore S, Pursnani S, Kumar S, et al. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy for prevention of spontaneous myocardial infarction in subjects with stable ischemic heart disease. Circulation. 2013;127:769–81. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.131961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Moussa ID, Klein LW, Shah B, et al. Consideration of a new definition of clinically relevant myocardial infarction after coronary revascularization: an expert consensus document from the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62:1563–70. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.08.720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Erne P, Schoenenberger AW, Burckhardt D, et al. Effects of percutaneous coronary interventions in silent ischemia after myocardial infarction: the SWISSI II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;297:1985–91. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.18.1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gada H, Kirtane AJ, Kereiakes DJ, et al. Meta-analysis of trials on mortality after percutaneous coronary intervention compared with medical therapy in patients with stable coronary heart disease and objective evidence of myocardial ischemia. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115:1194–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.01.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]