Atypical Haemolytic Uraemic Syndrome (aHUS) has been conventionally defined by the triad of microangiopathic haemolytic anaemia, thrombocytopenia and renal failure, without an infectious cause. It is now known as a form of thrombotic microangiopathy (TMA), caused by uncontrolled over-activation of the alternative pathway (AP) of complement which results in the generation of the membrane attack complex (C5b-9) leading to endothelial injury and microvascular thrombosis. This viewpoint has allowed recognition of aHUS in patients with a variety of comorbidities (Cataland & Wu, 2014; Tsai, 2014). TMA with multi-organ involvement has been described in patients with sickle cell disease (SCD) as a rare complication of unknown aetiology (Bolanos-Meade et al, 1999; Lee et al, 2003; Shome et al, 2013). We report here a patient with SCD and TMA with evidence of complement AP activation successfully treated with eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody to C5, that blocks terminal complement activation and is approved for treatment of aHUS.

A 19-year-old African-American female with SCD (βSβS genotype), hospitalized for vaso-occlusive crisis, developed acute exacerbation with generalized pain associated with fever, tachypnoea and pulmonary infiltrates consistent with acute chest syndrome. She required erythrocytapheresis (day 0 in Fig 1) with prompt improvement of her respiratory symptoms. However, significant haemolysis, thrombocytopenia and renal failure were noted over the next 24 h. Direct antiglobulin test was negative. She was commenced on daily dialysis; a seizure occurred during dialysis on day 4. A brain magnetic resonance imaging scan was normal, but the patient remained disoriented and difficult to arouse. Schistocytes were noted on a blood smear (Fig 2), which, along with thrombocytopenia and end-organ failure, were suggestive of TMA. Plasma ADAMTS13 activity was normal at 80%, ruling-out congenital or acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Plasmapheresis was initiated immediately after the seizure as first line of therapy for TMA (Cataland & Wu, 2014) with dramatic platelet count recovery (Fig 1), but our patient continued to show signs of central nervous system (CNS) depression with slow improvement of renal failure. She continued to receive plasmapheresis (daily × 4, and then every other day) but on day 11 whilst receiving plasmapheresis, she experienced respiratory distress, with hypoxia and crackles on auscultation. Chest radiograph showed bibasilar opacities concerning for Transfusion-Associated Lung Injury. Plasmapheresis was discontinued and, as renal failure persisted, we initiated eculizumab treatment. Within 24 h of administration of anti-C5, the patient’s alertness dramatically improved, reporting less pain with decreased use of opiates. Continued improvement in haemolysis and renal function was noted. Eculizumab was infused weekly at 900 mg for 4 weeks, leading to normalization of renal function. Currently, 26 months after the occurrence of aHUS, the patient has normal renal function without evidence of relapse even at times of vaso-occlusive crisis. Frozen stored plasma samples were used to measure sC5b-9 levels retrospectively (Fig 1). Prior to plasmapheresis increased levels of sC5b-9 confirmed complement activation, while, after eculizumab treatment and return to clinical and laboratory baseline for the patient, sC5b-9 levels normalized. Sequence analysis of the complement regulatory genes revealed a heterozygous mutation of CFB (c.724A>C, p.I242L), previously reported to be associated with aHUS (Maga et al, 2010).

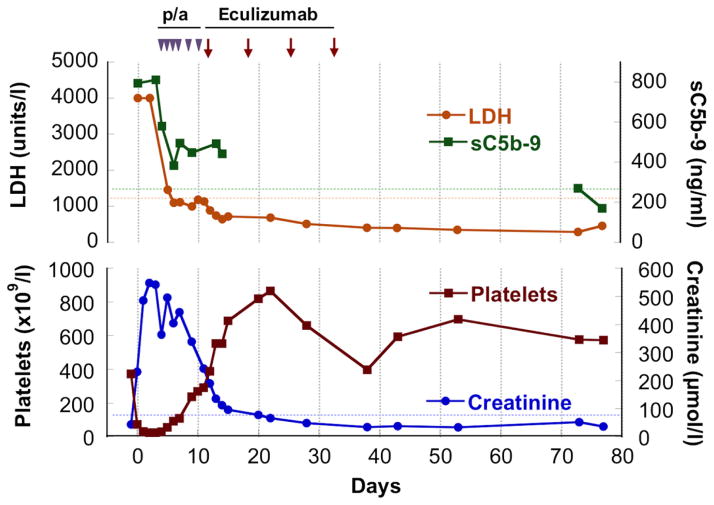

Fig 1.

The patient was diagnosed with acute chest syndrome and treated with erythrocytapheresis on day 0. Haemolysis [haemoglobin decrease by 30 g/l and lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) >4000 iu/l; upper limit of normal 920 iu/l], thrombocytopenia (platelet count down to 31 × 109/l) and renal failure (creatinine up to 548 μmol/l) developed by day 1, requiring dialysis. With the diagnosis of thrombotic microangiopathy on day 4, the patient was started on plasmapheresis (p/a) with slow improvement of her renal failure. Eculizumab was initiated on day 11 due to worsening respiratory status with plasma therapy; the patient had already been immunized against meningococcus according to sickle cell disease care guidelines. A remarkable clinical improvement was noted within a day after eculizumab infusion, while normalization of LDH, creatinine and platelet count followed in the ensuing 7 d. Retrospective evaluation of sC5b-9 plasma levels (MicrovueTM Enzyme Immunoassay, Quidel Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA) revealed that sC5b-9 was initially markedly elevated to >800 ng/ml (normal <244 ng/ml). The levels improved after plasmapheresis and eculizumab treatment; no plasma samples were available between day 14 and 73 to determine the sC5b-9 course in detail. We confirmed the return to normal levels when the patient had completely recovered and was seen in follow-up on days 73–77. During dialysis and plasma therapy, creatinine levels remained elevated between 230 and 539 μmol/l and decreased only after eculizumab was started, normalizing (below 84 μmol/l) by day 22. Dotted lines signify the higher level of normal range for SC5b-9, LDH and creatinine. Eculizumab therapy was cautiously discontinued after a 4-week course with close monitoring of the patient.

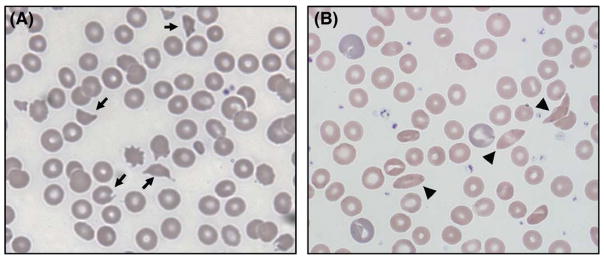

Fig 2.

(A) Blood smear on day 4 showing schistocytes and helmet cells (arrows), along with paucity of platelets. (B) Blood smear after complete recovery, post-eculizumab, showing occasional sickle cells (arrowheads) and normal platelet count. Polychromasia of the red blood cells seen in this blood smear is normal at baseline for this patient with sickle cell disease.

Thrombotic microangiopathy secondary to complement AP activation is suspected when haemolytic anaemia and thrombocytopenia is associated with severe acute kidney injury. Complement-mediated TMA can occur secondary to a hereditary complement defect and/or complement AP activation precipitated by systemic infection, inflammation, cancer or haematopoietic stem cell transplant, among others (Tsai, 2014). Hereditary complement defect-related TMA usually results from heterozygous mutations involving CFH, CFI, C3, CD46 (MCP), CFB and THBD genes (Roumenina et al, 2011). CFH autoantibodies are also a frequent cause of aHUS. It is important to note that severe neurological injury can occur, even in ADAMTS13-sufficient aHUS patients. Complement AP activation in SCD may result from the effect of haem on endothelial surfaces (Frimat et al, 2013) or from the effect of altered erythrocyte membrane phospholipids (Wang et al, 1993). In addition, overactive, ultra-large von Willebrand factor (VWF) multimers released from damaged endothelial cells or caused by inability of ADAMTS13 to cleave haemoglobin-bound VWF may contribute to the pathogenesis of TMA in SCD (Shome et al, 2013). Although, we did not detect a significant presence of ultra-large VWF multimers in our patient’s plasma during the acute phase of the crisis, on day 3 (data not shown), there was significant increase of VWF antigen (249 iu/dl, normal range 50–160 iu/dl) and activity (219 iu/dl, normal range 46–141 iu/dl). We cannot exclude the possibility that hyperadhesive VWF strands were tethered to the endothelial surface, contributing to microangiopathic haemolysis (Chen et al, 2011) with consecutive complement AP activation. Free haem from haemolysis secondary to SCD crisis has been shown to interact with C3 either in fluid-phase or on endothelial surfaces and result in increased sC5b-9 levels (Frimat et al, 2013). SCD patients have high levels of C3 at baseline in comparison to control subjects with normal haemoglobin. Further increase of C3 was noted during crisis, which, in addition to increased phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine exposure on sickle erythrocytes, may cause complement AP activation (Wang et al, 1993). In our patient, such phenomena might have initiated complement AP activation and the presence of CFB mutation exacerbated its deleterious effects.

The present case demonstrates that complement-mediated TMA, i.e. aHUS, can develop in patients with SCD, which may function as a complement-activating comorbidity, particularly when an underlying genetic defect in complement regulation is present. The benefit of eculizumab clearly noted in our patient with rapid resolution of renal failure, probably preventing chronic kidney damage, and clinical improvement of CNS further strengthens the pathogenicity of complement AP activation. Retrospectively, real-time results on sC5b-9 levels or knowledge of the patient’s complement-altering mutation would have allowed us to proceed to eculizumab treatment earlier. In this first report of use of eculizumab for aHUS in SCD, we want to emphasize the importance of high index of suspicion for early diagnosis of TMA in SCD as early institution of appropriate treatment can prevent chronic multi-organ damage and death.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the USA National Institutes of Health grant NHLBI U01 HL117709.

Footnotes

Author contributions

SC, ShC, KAK, and TAK collected the data, DI performed the sC5b-9 assay, SC, RG, and TAK analyzed and interpreted the data and all authors contributed to the writing of the paper.

Competing interests

SC, ShC, KAK, DI and TAK have nothing to disclose and no competing interests. RG is a member of the speaker’s bureau for Alexion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., manufacturer of eculizumab.

References

- Bolanos-Meade J, Keung YK, Lopez-Arvizu C, Florendo R, Cobos E. Thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura in a patient with sickle cell crisis. Annals of Hematology. 1999;78:558–559. doi: 10.1007/s002770050558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cataland SR, Wu HM. How I treat: the clinical differentiation and initial treatment of adult patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2014;123:2478–2484. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-11-516237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Hobbs WE, Le J, Lenting PJ, de Groot PG, Lopez JA. The rate of hemolysis in sickle cell disease correlates with the quantity of active von Willebrand factor in the plasma. Blood. 2011;117:3680–3683. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-302539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frimat M, Tabarin F, Dimitrov JD, Poitou C, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Fremeaux-Bacchi V, Roumenina LT. Complement activation by heme as a secondary hit for atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Blood. 2013;122:282–292. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-03-489245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee HE, Marder VJ, Logan LJ, Friedman S, Miller BJ. Life-threatening thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP) in a patient with sickle cell-hemoglobin C disease. Annals of Hematology. 2003;82:702–704. doi: 10.1007/s00277-003-0715-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maga TK, Nishimura CJ, Weaver AE, Frees KL, Smith RJ. Mutations in alternative pathway complement proteins in American patients with atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Human Mutation. 2010;31:E1445–E1460. doi: 10.1002/humu.21256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roumenina LT, Loirat C, Dragon-Durey MA, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L, Sautes-Fridman C, Fremeaux-Bacchi V. Alternative complement pathway assessment in patients with atypical HUS. Journal of Immunological Methods. 2011;365:8–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shome DK, Ramadorai P, Al-Ajmi A, Ali F, Malik N. Thrombotic microangiopathy in sickle cell disease crisis. Annals of Hematology. 2013;92:509–515. doi: 10.1007/s00277-012-1647-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsai HM. A mechanistic approach to the diagnosis and management of atypical hemolytic uremic syndrome. Transfusion Medicine Reviews. 2014;28:187–197. doi: 10.1016/j.tmrv.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang RH, Phillips G, Jr, Medof ME, Mold C. Activation of the alternative complement pathway by exposure of phosphatidylethanolamine and phosphatidylserine on erythrocytes from sickle cell disease patients. Journal of Clinical Investigation. 1993;92:1326–1335. doi: 10.1172/JCI116706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]