Highlights

-

•

Paraduodenal pancreatitis is a rare form of focal chronic or recurrent pancreatitis that can present as gastric outlet obstruction.

-

•

Endoscopic ultrasound and fine needle aspiration biopsy provides the best diagnostic modality.

-

•

Key histopathologic features include Brunner gland hyperplasia, myofibroblastic proliferation, spindle cells and foamy cells.

-

•

Cross-sectional imaging demonstrates a fibrotic, sheet-like mass with cystic change between the duodenal wall and pancreatic head.

-

•

The optimal treatment for refractory symptoms is pancreaticoduodenectomy.

Keywords: Cystic pancreatic heterotopic dystrophy, Duodenal stenosis, Groove pancreatitis, Paraduodenal pancreatits, Case report

Abstract

Introduction

Paraduodenal pancreatitis (PP) is an under-recognized form of focal chronic or recurrent pancreatitis. Since PP presents with non-specific symptoms and shares radiological and histopathological features with other entities, it can be challenging to diagnose.

Presentation of case report

Herein, a case of a 64 year-old Caucasian male with PP presenting with recurrent gastric outlet obstruction (GOO) is detailed. Over the course of two years, he underwent multiple balloon dilatations for symptom management. His diagnostic course was complicated by inconclusive and misleading biopsies.

Conclusion

PP can rarely present as GOO in otherwise asymptomatic patients. A preoperative pathologic diagnosis can be difficult to obtain, and in this case delayed definitive surgical management. The case is discussed in detail, and a concise review the current literature was undertaken.

1. Introduction

PP, also commonly known as groove pancreatitis, is a less-recognized form of pancreatitis and often poses a diagnostic and therapeutic challenge [1], [2]. We herein report the clinical features and therapeutic management of a complex case of PP presenting with GOO. This work has been reported in line with the SCARE criteria [3]. Informed consent was obtained from the patient for this publication.

2. Presentation of case

A 64 year-old Caucasian male was referred to the Liver and Pancreas Unit at the Ottawa General Hospital for assessment of a cystic duodenal lesion abutting the head of the pancreas consistent. His past medical history was remarkable for multiple episodes of gastric outlet obstruction requiring urgent endoscopic duodenal dilation. Other medical co-morbidities included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, major depressive disorder, gastro-esophageal reflux disease, hypercholesterolemia, and hypertension. His past surgical history was remarkable for a remote hemorrhoidectomy and right total hip arthroplasty. He quit smoking 9 years prior to his presentation, and had a 35 pack-year smoking history. There was no significant history of alcohol use.

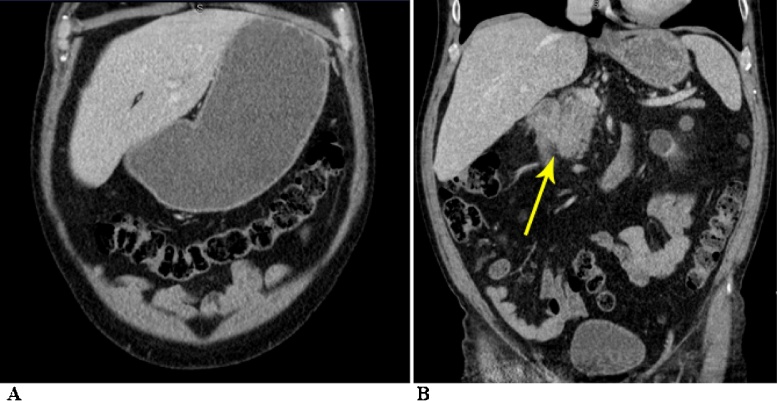

Two years prior the duodenal lesion was identified when he first presented to his local hospital with symptoms of gastric outlet obstruction (Fig. 1). At the time of presentation to our centre, computed tomography (CT) revealed narrowing at the junction of the 1st and 2nd part of the duodenum in conjunction with a cystic lesion abutting the pancreatic head (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) also obtained at this time revealed a 3.2 by 2.6 cm lesion between the duodenum and pancreatic head. The lesion demonstrated slightly low signal intensity on T2-weighted sequence, and low signal intensity on T1-weighted sequence with delayed enhancement. There was no evidence of common bile duct (CBD) or pancreatic duct dilatation. Based on the radiological findings, the differential diagnosis included ectopic pancreatic tissue, cystic gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and lymphoma. The possibility of adenocarcinoma was not completely ruled out, though felt less likely given the chronicity of both his symptoms and imaging findings.

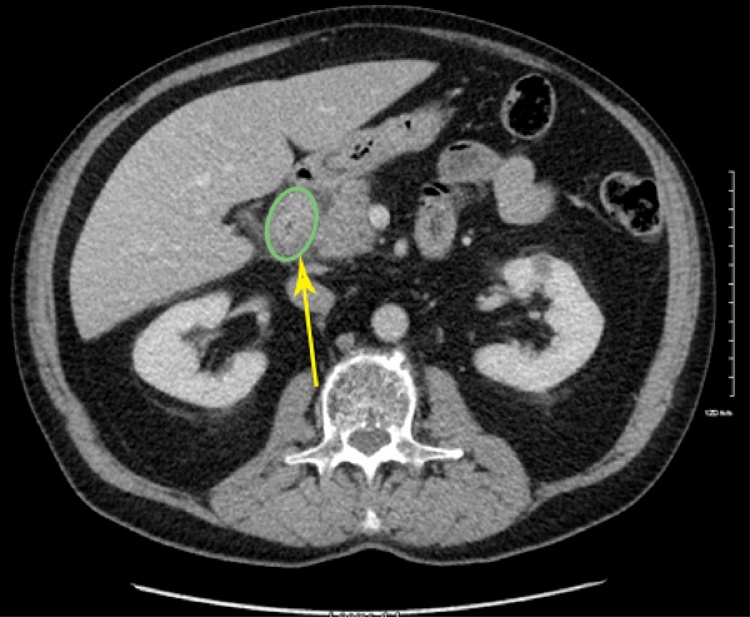

Fig. 1.

CT scan from 2 years prior demonstrating duodenitis (green circle) and periduodenal inflammatory change (yellow arrow).

Fig. 2.

Preoperative CT scan demonstrating (A) gastric outlet obstruction and (B) paraduodenal inflammatory changes (yellow arrow).

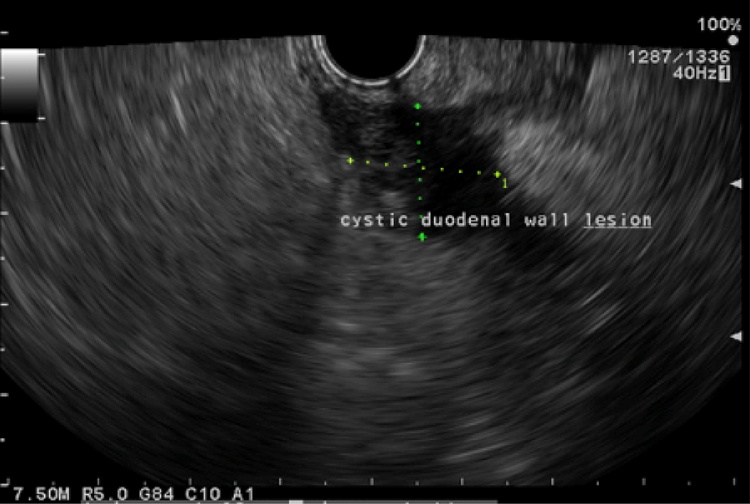

Oesophagogastroduodenoscopy (OGD) and biopsy of the lesion were carried out. Duodenoscopy showed a 2 cm stricture at junction of D1-D2 with overlying erythematous mucosa in the absence of any other abnormalities. A CRE™ balloon dilatation was undertaken to relieve the duodenal stenosis. Echoendoscopic evaluation revealed two hypoechoic, heterogenous, poorly demarcated lesions arising from the duodenal muscularis propria and abutting the pancreatic head; these lesions measured 12 × 4 mm and 5 × 3 mm (Fig. 3). The pancreatic parenchyma was noted to be unremarkable. No local lymphadenopathy was present. Biopsies of the stricture showed non-specific benign intestinal cells and lymphocytes admixed with histiocytes. Neither dysplasia or malignancy was present. On EUS evaluation the lesions were felt to be most compatible with PP.

Fig. 3.

EUS 1 month preoperatively demonstrating cystic lesion in duodenal wall.

Over the course of the next two years, the patient underwent six endoscopic duodenal dilatations for symptoms that included nausea, vomiting, postprandial fullness, nighttime coughing, and worsening regurgitation. While the endoscopic dilatations provided temporary relief of symptoms, the time between subsequent symptomatic episodes progressively shortened.

Considering the recurrent nature of obstructions, and the necessity for repeated endoscopic management, surgical intervention was recommended. Consideration was given to both resection consisting of pancreaticoduodenectomy, or a gastrojejunal bypass. Since his symptoms predominately related to obstruction without a history of pain, the initial surgical plan was to perform a bypass. Before the scheduled operation he again presented to the emergency department with gastric outlet obstruction. This lead to a repeat endoscopic duodenal dilatation and endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS) guided fine needle aspiration biopsy (FNAB). On this occasion the biopsies showed spindle cells, which raised doubt about the working diagnosis of PP, and the possibility of a mesenchymal tumor such as a GIST was considered. As such, the operative plan was changed, and he underwent a standard pancreaticoduodenectomy. During the operation, the mass in the head of the pancreas was easily palpated. There was no evidence of metastatic disease. The neck of the pancreas was relatively firm, which was favored to represent chronic inflammatory change as opposed to malignancy. The remaining pancreatic parenchyma was normal and soft. His postoperative course was complicated by paralytic ileus requiring nasogastric tube placement on post-operative day (POD) 3. Furthermore, on POD 7 he developed fever and leukocytosis and was diagnosed with an International Study Group of Pancreatic Surgery (ISGPS) Grade B pancreatic fistula requiring both antibiotics and insertion of a percutaneous peripancreatic drain.

The final pathology demonstrated typical features of PP. There was evidence of pseudocystic changes in the duodenal wall, numerous fibroblasts, and mixed inflammatory infiltrates, including plasma cells, eosinophils, and lymphoid aggregates. Diffuse, marked Brunner gland hyperplasia formed a thick layer with surrounding smooth muscle, adipose tissue and myofibroblastic proliferation. The myofibroblastic proliferation encased areas of cystic change corresponding to the spindle cells identified on the previous FNAB. Extensive duodenal submucosal fibrosis was evident, which replaced most of the muscularis propria of the duodenum, and extended to the adjacent peripancreatic tissues. There was no evidence of dysplasia or malignancy.

He was seen back in the surgical clinic 4 weeks following his hospital discharge. He was clinically well, maintaining weight, and the drain output had ceased. The drain was removed, and antibiotic therapy was discontinued.

3. Discussion

PP is a form of chronic or recurrent focal pancreatitis [1], [2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [8], [9]. It affects the gastroduodenal groove, which is an area between the dorso-cranial portion of the pancreatic head, duodenum, and CBD [1], [2], [4], [5]. It was first described in the French literature in 1970, and subsequently the English literature in 1993, as “cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas” by Potet et al. [10], [11]. However, it has since been known by a multitude of other names including; groove pancreatitis, cystic pancreatic heterotopic dystrophy, myoadenomatosis of the duodenum, pancreatic hamartoma of the duodenum, and paraduodenal wall cyst [5]. In 2004, Adsay and Zamboni proposed that the umbrella term of paraduodenal pancreatitis be used to describe this condition and provide clarity in the clinical literature [12].

The incidence of PP is not well established, as it is felt to represent an under-recognized form of pancreatitis. In published surgical series of patients undergoing pancreaticoduodenectomy for the indication of chronic pancreatitis, the incidence varied from 2.7% to 24.5% [4]. PP generally presents with symptoms of abdominal pain, nausea, postprandial vomiting, and long-term weight loss [1], [2], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Duodenal luminal obstruction leading to gastric outlet obstruction is rare [7]. Cancer antigen 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen tumor markers are usually normal, while amylase and lipase may be elevated during an acute flair of pain [4], [7], [9]. The time to diagnosis is highly variable and depends on the treating phycian’s familiarity with the diagnosis. The largest series to date demonstrated a median time from onset of symptoms to diagnosis of 1 year [13].

PP is most commonly seen in Caucasian men in their fifth decade of life, and particularly in those with a history of alcohol abuse [1], [2], [4], [5], [6], [7], [9], [13]. To date, the largest reported series examined 105 patients; 91% were male while 86% were described as chronic alcoholics [13]. A less-recognized risk factor is smoking [1], [8], [9]. The exact underlying etiology of how pancreatitis leads to duodenal and biliary stricture is unclear and believed to be multifactorial; obstruction of duct of Santorini (minor duct), structural and functional abnormalities of the minor papilla, pancreatic heterotopia, and the formation of duodenal wall cysts are believed to contribute to the process [4], [8]. One proposed mechanism suggests that both alcohol consumption and tobacco exposure increases the viscosity of pancreatic secretions leading to stasis and outflow obstruction of the minor pancreatic duct [8]. In turn, this causes local irritation and inflammation that over time causes calcification of duct of Santorini, minor papilla, and the area surrounding the pancreatic head. Fibrosis and scaring result in stenosis of the CBD, and increased rigidity of the duodenal wall leading to eventual duodenal stricture [1], [4], [8], [9]. Although the histopathologic findings of PP are commonly seen in conjunction with chronic pancreatitis, PP also exists as an independent pathologic finding in 29–50% of cases [13], [14].

The common pathologic findings consist of cystic lesions within both the duodenal submucosa and muscularis propria. These cysts can contain clear fluid, thick granular material, and occasionally stones [1], [2], [4], [6], [7], [8], [9], [15]. The most common histologic features of PP include Brunner gland hyperplasia, myofibroblastic proliferation, spindled stromal cells, lipid-laden macrophages (foamy cells), and granular cellular debris. There are no features that are truly specific to PP [15]. Myloid proliferation is often very prominent in the region of the minor papilla and has led to the misdiagnosis of leiomyoma or GIST on biopsy, as was seen in the presented case [15], [16]. Furthermore, biopsy can incorrectly push the diagnosis towards other malignancies as well, including islet cell neoplasms or undifferentiated carcinomas with osteoclast-like giant cells [16].

The diagnostic workup of PP includes cross-sectional imaging and EUS ± FNAB. OGD typically demonstrates extrinsic duodenal compression with the overlying mucosa appearing normal [2]. On CT scan, these lesions appear as fibrotic, sheet-like, hypodense masses lacking enhancement, located between the pancreatic head and a thickened duodenal wall [1], [4], [5], [6], [7]. Cystic changes may be visible within the duodenal wall or the duodenum may only appear markedly thickened. The CBD can be dilated with a smooth distal tapering [4]. Similarly, on MRI these lesions appear as sheet-like masses between the duodenum and pancreatic head [4], [5], [6], [7]. They are hypointense on T1-weighted images, but can be hypo-, iso-, or marginally hyperintense on T2-weighted images. The slight hyperintensity on T2 weighted images owes to the initial edema during the subacute phase in the paraduodenal groove; however with time the signal diminishes as edema is replaced with fibrosis [4], [5]. MRI is more sensitive than CT for demonstrating cystic changes within the thickened duodenal wall [7], [17]. Post-gadolinium MRI typically demonstrates patchy enhancement on venous phase. There an also be delayed enhancement, which is a feature of the fibrotic nature of these lesions [4].

Although both CT and MRI can be diagnostic, EUS-FNAB is the most accurate and reliable in differentiating and diagnosing inflammatory, cystic, and neoplastic diseases of the pancreas [2], [18], [19], [20]. EUS provides high resolution images by means of having a high-frequency transducer placed in close proximity of the lesion. It allows to visualize the anatomic layers of duodenum, assess the caliber and patency of the biliary and pancreatic ducts, and characteritize key features that enable PP to be differentiated from other pancreatic entities such as pancreatic pseudocysts, cystic tumors, or necrotic duodenal tumors. It also can provide a tissue diagnosis by means of FNAB [2]. In one study assessing the yield of EUS-FNAB in patients with pancreatic masses, EUS-FNAB sensitivity and specificity were 94.7% and 100%, respectively [19].

There are a number of key imaging features that help differentiate these lesions from other pancreatic pathology. In contrary to pancreatic adenocarcinoma, there is absence of vascular encasement in PP. Additionally, periampullary carcinomas typically exhibit an abrupt termination of the CBD at the level of the tumor (‘shoulder sign’) [4], [5]. In contrast, a longer and smooth tapering CBD is observed in PP [4]. Unlike gastrinomas, which are the most common neuroendocrine tumors in the groove area, PP does not exhibit hypervascularity or peripheral ring-like enhancement [4]. Furthermore, there is also absence of invasion into neighboring organs or metastases in PP and there is generally not lymphadenopathy [7]. Still, the major difficulty in diagnosing PP is being able to reliably distinguish it from a pancreatic malignancy.

Since PP was first described in the 1970s, different treatment modalities have been proposed varying from symptom-directed medical therapy to surgical resection [1], [2], [4], [6], [9], [21]. Medical management during an acute exacerbation generally involves fasting, abstinence from alcohol, and analgesics [1], [2]. However, conservative management tends to be a temporizing measure, and patients generally continue to have progressive symptoms [4]. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) have been used, and can improve the symptoms of gastrointestinal reflux in patients with partial gastric outlet obstruction. Recent animal studies have suggested that PPIs may have the added benefit of decreasing pancreatic secretions [22]. Similarly, pharmacological management with octreotide has been also proposed [2], [23]. In chronic pancreatitis, pain is thought to be due to increase pressure within the pancreatic ductal system and parenchyma. The use of octreotide reduces pancreatic secretions, and theoretically relieves the elevated intrapancreatic pressure, thereby reducing pain. Based on the current literature, the effect of octreotide in patients with PP has been highly variable. The effect of octreotide is generally delayed, and somatostatin analogues exhibit tachyphalaxis, which limits the efficiacy of this treatment strategy [2], [21]. In addition, robust long-term follow-up data of PP patients treated with octreotide is not available [2], [21]. Endoscopic management with cyst fenestration or drainage, and pancreatic ductal stenting have also been proposed as management options, although symptom relapse is common [16], [22]. To date, surgical management with pancreaticoduodenectomy has achieved the best results in patients with PP [1], [2], [22], [24]. It allows for definitive tissue diagnosis, resolution of pain in up to 91% of patients, and avoids the risk of recurrence (Table 1) [1], [2], [9], [23], [25], [26]. Gastric bypass with gastro-jejunostomy has also been proposed, particularly for those with obstructive symptoms [1]. This less complex surgical approach allows pancreatic tissue to be spared and reduces surgical morbidity. However, the lesion is not removed and the potential risk of undiagnosed malignancy is not eliminated. In addition, while the obstruction is relieved by bypass, patients may continue to have pain due to the compressive effects of the mass; the pain may worsen over time as the mass continues to grow. Another surgical approach described for PP is a pancreas-preserving duodenectomy [1]. Although this enables the preservation of pancreatic tissue, long-term resolution of symptoms is less than with pancreaticoduodenectomy [1].

Table 1.

Surgical series of pancreaticoduodenectomy for PP: studies with 10 or more patients.

| Study (Year) | Country | Sample size, n (Male:Female) | No. of patients with preoperative pain (%) | Mean age, years (range) | No. of patients with preoperative diagnosis of PP n (%) | No. of pancreatico-duodenectomy (%) | Mean follow-up months (range) | Mortality n (%) | Complete resolution of pain n (%) | No of patients with dysplasia or malignancy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pessaux et al. [22] (2006) | France | 12 (11:1) | 11 (92) | 42.4 (34–54) | 8 (66.7) | 12 (100) | 64 (6–158) | 1 (8.3) | 10 (90.9) | 0 |

| Rebours et al. [12] (2007) | France | 105 (96:9) | 96 (91) | 48 (29–76)b | – | 17 (16) | 15 (0–243)b | – | 35 (33.3) | – |

| Rahman et al. [24] (2007) | United Kingdom | 11 (10:1) | 11 (100) | 48 (35–61)b | 6 (54.5) | 11 (100) | 52 (4–156)b | 1 (9.1) | 9 (90) | 0 |

| Casetti et al. [19] (2009) | Italy | 58 (54:4) | 46 (79.3) | 44.7 (aIQR 38.6–51.8)b | – | 58 (100) | 96.3 (IQR 59.7–129.7)b | 0 (0) | 35 (76) | 2 (3.4) |

| Egorov et al. [1] (2014) | Russia | 62 (59:3) | 62 (100) | 45.3 (28–73) | – | 29 (46.8) | – | 0 (0) | 23 (79) | – |

PP: Paraduodenal pancreatitis.

IQR – Interquartile range.

Median.

4. Conclusion

PP is a rare and distinct form of chronic or recurrent focal pancreatitis. It typically presents with non-specific symptoms including; abdominal pain, nausea, postprandial vomiting, and weight loss. There are key radiological and histopathological features that can help to clarify the diagnosis. EUS-FNAB provides the best diagnostic modality, short of surgical resection, however biopsies can, at times, be misleading. Key histopathological features include Brunner gland hyperplasia, myofibroblastic proliferation, spindle cells, foamy cells, and granular cellular debris. Cross-sectional imaging demonstrates fibrotic, sheet-like mass in between the pancreatic head and a thickened duodenal wall with cystic changes. Pancreaticoduodenectomy is the optimal treatment for patients with refractory symptoms as it has excellent short and long term efficacy, and definitive surgical resection eliminates diagnostic uncertainty.

Paraduodenal pancreatitis presenting as an isolated gastric outlet obstruction has not been previously reported in the literature. Awareness about PP with atypical symptomatology as well as common diagnostic dilemas in this condition are paramount in improving timely access to definitive diagnosis and treatment.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Institutional Ethics Board at The Ottawa Hospital was made aware of this case report and no objection was expressed. No REB review was required as this was a case report and not a research study.

Consent

The authors confirm that consent has been obtained from the patient and the manuscript includes a statement of consent at the end of the manuscript.

Authors contribution

Conception and Design: FKB, KAB.

Acquisition of Data: SL, VRB, LAS, FKB.

Analysis and Interpretation of Data: SL,VRB, LAS, PAJ, GM, RM, FKB, KAB.

Drafting the article: SL,VRB, LAS, PAJ, GM, RM, FKB, KAB.

Critically revising the article: SL, VRB, LAS, PAJ, GM, RM, FKB, KAB.

Surgical review and revision: GM, RM, FKB, KAB.

Gastroenterology review and revision: PDJ.

Study supervision: KAB, FKB.

All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Guarantor

Kimberly A Bertens.

Acknowledgment

None.

References

- 1.Egorov V.I., Vankovich A.N., Petrov R V., Starostina N.S., Butkevich A.T., Sazhin A.V. Pancreas-preserving approach to paraduodenal pancreatitis treatment: why, when, and how? Experience of treatment of 62 patients with duodenal dystrophy. BioMed Res. Int. 2014;2014 doi: 10.1155/2014/185265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Galloro G., Napolitano V., Magno L., Diamantis G., Nardone G., Bruno M. Diagnosis and therapeutic management of cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall in heterotopic pancreas. A case report and revision of the literature. J. Pancreas. 2008;9:725–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agha R.A., Fowler A.J., Saetta A., Barai I., Rajmohan S., Orgill D.P., for the SCARE Group The SCARE statement: consensus-based surgical case report guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2016;34:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2016.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferreira A., Ramalho M., Herédia V., de Campos R., Marques P. Groove pancreatitis: a case report and review of the literature. J. Radiol. Case Rep. 2010;4:9–179. doi: 10.3941/jrcr.v4i11.588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gupta R., Williams G.S., Keough V. Groove pancreatitis: a common condition that is uncommonly diagnosed preoperatively. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2014;28:181–182. doi: 10.1155/2014/947156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Malde D.J., Oliveira-Cunha M., Smith A.M. Pancreatic carcinoma masquerading as groove pancreatitis: case report and review of literature. J. Pancreas. 2011;12:598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hungerford J.P., Neill Magarik M.A., Hardie A.D. The breadth of imaging findings of groove pancreatitis. Clin. Imaging. 2015;39:363–366. doi: 10.1016/j.clinimag.2015.01.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Raman S.P., Salaria S.N., Hruban R.H., Fishman E.K. Groove pancreatitis: spectrum of imaging findings and radiology-pathology correlation. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2013;201:29–39. doi: 10.2214/AJR.12.9956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.DeSouza K., Nodit L. Groove pancreatitis: a brief review of a diagnostic challenge. Arch. Pathol. Lab. Med. 2015;139:417–421. doi: 10.5858/arpa.2013-0597-RS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fléjou J.F., Potet F., Molas G., Bernades P., Amouyal P., Fékété F. Cystic dystrophy of the gastric and duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas: an unrecognised entity. Gut. 1993;34:343–347. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Potet F., Duclerc N. Dystropie kystique sur pancreas aberrant de la paroi duodenale. Arch. Fr. Mal. App. Dig. 1970;59:223–238. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Adsay N.V., Zamboni G. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a clinico-pathologically distinct entity unifying cystic dystrophy of heterotopic pancreas, para-duodenal wall cyst, and groove pancreatitis. Semin. Diagn. Pathol. 2004;21:247–254. doi: 10.1053/j.semdp.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rebours V., Lévy P., Vullierme M.P., Couvelard A., O’Toole D., Aubert A. Clinical and morphological features of duodenal cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2007;102:871–879. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pezzilli R., Santini D., Calculli L., Casadei R., Morselli-Labate A.M., Imbrogno A. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall is not always associated with chronic pancreatitis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2011;17:4349–4364. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i39.4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fléjou J.F. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: a new unifying term and its morphological characteristics. Diagn. Pathol. 2011;18(1):31–36. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laugier R., Grandval P. Does paraduodenal pancreatitis systematically need surgery? Endoscopy. 2014;46:588–590. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1377268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalb B., Martin D.R., Sarmiento J.M., Erickson S.H., Gober D., Tapper E.B. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: clinical performance of MR imaging in distinguishing from carcinoma. Radiology. 2013;269:475–481. doi: 10.1148/radiology.13112056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bournet B., Gayral M., Torrisani J., Selves J., Cordelier P., Buscail L. Role of endoscopic ultrasound in the molecular diagnosis of pancreatic cancer. World J. Gastroenterol. 2014;20:10758–10768. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v20.i31.10758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eloubeidi M.A., Jhala D., Chhieng D.C., Chen V.K., Eltoum I., Vickers S. Yield of endoscopic ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration biopsy in patients with suspected pancreatic carcinoma: emphasis on atypical, suspicious, and false-negative aspirates. Cancer. 2003;99:285–292. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arora A., Dev A., Mukund A., Patidar Y., Bhatia V., Sarin S.K. Paraduodenal pancreatitis. Clin. Radiol. 2014;69:299–306. doi: 10.1016/j.crad.2013.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Becker V. Bauchspeicheldrüse. In: Doerr W., Seifert G., Ühlinger E., editors. Spezielle Pathologische Anatomie, Bd VI Hrsg. Springer; Berlin: 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wang J., Barbuskaite D., Tozzi M., Giannuzzo A., Sørensen C.E., Novak I. Proton pump inhibitors inhibit pancreatic secretion: role of gastric and non-gastric H+/K+-ATPases. PLoS One. 2015;10:1–20. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0126432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pessaux P., Lada P., Etienne S., Tuech J.J., Lermite E., Brehant O. Duodenopancreatectomy for cystic dystrophy in heterotopic pancreas of the duodenal wall. Gastroenterol. Clin. Biol. 2006;30:24–28. doi: 10.1016/s0399-8320(06)73073-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tison C., Regenet N., Meurette G., Mirallie E., Cassagnau E., Frampas E. Cystic dystrophy of the duodenal wall developing in heterotopic pancreas. Report of 9 cases. Pancreas. 2007;34(1):152–156. doi: 10.1097/01.mpa.0000246669.61246.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rahman S.H., Verbeke C.S., Gomez D., McMahon M.J., Menon K.V. Pancreatico-duodenectomy for complicated groove pancreatitis. HPB (Oxford) 2007;9:229–234. doi: 10.1080/13651820701216430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casetti L., Bassi C., Salvia R., Butturini G., Graziani R., Falconi M. Paraduodenal pancreatitis: results of surgery on 58 consecutives patients from a single institution. World J. Surg. 2009;33:2664–2669. doi: 10.1007/s00268-009-0238-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]