Abstract

Background

Methylation plays an important role in the etiology and pathogenesis of colorectal cancer (CRC). This study aimed to identify aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and pathways in CRC by comprehensive bioinformatics analysis.

Methods

Data of gene expression microarrays (GSE68468, GSE44076) and gene methylation microarrays (GSE29490, GSE17648) were downloaded from GEO database. Aberrantly methylated-DEGs were obtained by GEO2R. Functional and enrichment analyses of selected genes were performed using DAVID database. Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network was constructed by STRING and visualized in Cytoscape. MCODE was used for module analysis of the PPI network.

Results

Totally 411 hypomethylation-high expression genes were identified, which were enriched in biological processes of response to wounding or inflammation, cell proliferation and adhesion. Pathway enrichment showed cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, p53 signaling and cell cycle. The top 5 hub genes of PPI network were CAD, CCND1, ATM, RB1 and MET. Additionally, 239 hypermethylation-low expression genes were identified, which demonstrated enrichment in biological processes including cell–cell signaling, nerve impulse transmission, etc. Pathway analysis indicated enrichment in calcium signaling, maturity onset diabetes of the young, cell adhesion molecules, etc. The top 5 hub genes of PPI network were EGFR, ACTA1, SST, ESR1 and DNM2. After validation in TCGA database, most hub genes still remained significant.

Conclusion

In summary, our study indicated possible aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes and pathways in CRC by bioinformatics analysis, which may provide novel insights for unraveling pathogenesis of CRC. Hub genes including CAD, CCND1, ATM, RB1, MET, EGFR, ACTA1, SST, ESR1 and DNM2 might serve as aberrantly methylation-based biomarkers for precise diagnosis and treatment of CRC in the future.

Keywords: Methylation, Expression, Bioinformatics, Colorectal cancer

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is one of the most common malignant tumors with incidence ranked third in men and second in women worldwide [1]. Multiple factors might cause CRC including alcohol, smoking, obesity and insufficient physical exercise [2]. The accumulation of various genetic and epigenetic alternations in colorectal epithelial cells is also regarded as essential processes driving the initiation and progression of CRC [3].

Epigenetics is known as heritable alterations in gene expression that are not mediated by changes within the DNA sequence [4]. Cancer epigenetic covers aspects of DNA methylation, noncoding RNA and histone modification, of which the most widely investigated epigenetic changes is aberrant DNA methylation [5]. Aberrant methylation could influence the functions of key genes especially tumor suppressor genes through altering their expression, thus making it involved in various processes of CRC development [6]. Although multiple studies have demonstrated certain genes with aberrant DNA hypermethylation or hypomethylation in CRC, the comprehensive profile and pathways of the interaction network remain largely elusive.

In recent years, micoarrays based on high-throughput platforms emerge as a promising and efficient tool to screen significant genetic or epigenetic alternations in carcinogenesis and identify biomarkers for diagnosis and prognosis of cancer [7]. A number of gene expression profiling microarrays have been conducted to find various differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in CRC [8]. In addition, some studies concerning aberrant methylation in CRC have also been performed to indicate differentially methylated genes (DMGs) [9]. However, individual investigations possess limited numbers of overlapping gene profiling and insufficient power to identify key genes and pathways involved in multiple cellular process and biological function. Now, by the means of advanced bioinformatics analysis of available microarray data, it is possible to come up with more reliable and precise screening results via overlapping relevant data sets.

Until now, no research has been performed to jointly analyze information of both gene expression profiling microarray and gene methylation profiling microarray in the development of CRC. In the present study, data of gene expression profiling microarrays (GSE68468, GSE44076) and gene methylation profiling microarrays (GSE29490, GSE17648) were integrated and analyzed by a series of bioinformatics tools. Aberrantly methylated-DEGs and pathways were identified in CRC. Protein–protein interaction network was constructed and hub genes were revealed. By this means, we expect to find novel aberrantly methylated genes and pathways in CRC and shed light on the underlying molecular mechanisms that orchestrate colorectal carcinogenesis.

Materials and methods

Microarray data

In the present study, the gene expression profiling data sets (GSE68468, GSE44076) and gene methylation profiling data sets (GSE29490, GSE17648) were obtained from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) of The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI). Totally 186 CRC and 55 normal mucosa specimens were enrolled in GSE68468 (platform: GPL96 Affymetrix Human Genome U133A Array) while 98 CRC and 50 normal mucosa specimens were enrolled in GSE44076 (platform: GPL13667 Affymetrix Human Genome U219 Array). For gene methylation profiling microarray, GSE29490 included a total of 48 paired normal and CRC samples from 24 patients while GSE17648 included altogether 44 paired normal and CRC samples from 22 patients. Both of these two methylation microarray used platform GPL8490 (Illumina HumanMethylation27 BeadChip).

Data processing

We used GEO2R online software to analysis the raw submitter-supplied data of microarrays and identify DEGs and DMGs. GEO2R is an interactive web tool which allows users to compare different groups of samples in a GEO series in order to screen genes that are differentially expressed across experimental conditions. P < 0.05 and |t| > 2 were used as the cut-off criteria to find DEGs and DMGs. Subsequently, MATCH function was adopted to identify overlapping DEGs in the two gene expression profiling data sets of GSE68468 and GSE44076, and overlapping DMGs in the two gene methylation profiling data sets of GSE29490 and GSE17648. Finally, hypomethylation-high expression genes were obtained by overlapping hypomethylation and up-regulated genes; hypermethylation-low expression genes were obtained by overlapping hypermethylation and down-regulated genes.

Functional and pathway enrichment analysis

The Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery (DAVID, https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) was used to perform functional and pathway enrichment analysis. DAVID offers systematic and integrative functional annotation tools for investigators to unravel biological meaning behind large list of genes [10]. Gene ontology (GO) analysis including the cellular component, molecular function, and biological process [11] and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway enrichment analysis [12] were conducted for the selected hypomethylation-high expression genes and hypermethylation-low expression genes by DAVID. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistical significance.

Protein–protein interaction (PPI) network construction and module analysis

The functional protein–protein interaction (PPI) analysis is essential to interpret the molecular mechanisms of key cellular activities in carcinogenesis. In this study, we used Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes (STRING) database to construct PPI network of hypomethylation-high expression genes and hypermethylation-low expression genes, respectively. Interaction score of 0.4 was regarded as the cut-off criterion and the PPI was visualized. Subsequently, the Molecular Complex Detection (MCODE) in Cytoscape software was conducted to screen modules within PPI network with MCODE score >3 and number of nodes >4. Hub genes were selected with connection degree >10. The functional enrichment analysis of the genes in individual module was achieved by DAVID with a significance threshold of P < 0.05.

Validation of the hub genes in TCGA database

The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database, a collaboration between the National Cancer Institute (NCI) and National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), has generated comprehensive, multi-dimensional maps of the key genomic changes in various types of cancers. In order to confirm the results, hypomethylation-high expression hub genes and hypermethylation-low expression hub genes were then validated in another database TCGA.

Results

Identification of aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes in CRC

Data from each microarray were separately analyzed by online software GEO2R to screen DEGs or DMGs. Fdor DEGs of gene expression microarray, 3411 overlapping up-regulated genes (4736 in GSE68468, 7618 in GSE44076) and 2623 overlapping down-regulated genes (3630 in GSE68468, 9686 in GSE44076) were identified. For DMGs of gene methylation microarray, 1534 overlapping hypermethylation genes (2071 in GSE29490, 2269 in GSE17648) and 3011 overlapping hypomethylation genes (3786 in GSE29490, 4907 in GSE17648) were found.

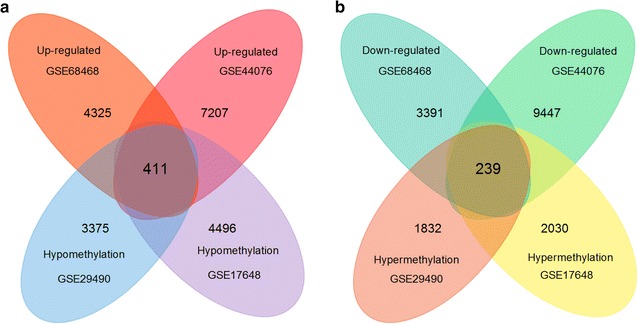

Then, totally 411 hypomethylation-high expression genes were obtained by overlapping 3011 hypomethylation genes and 3411 up-regulated genes; 239 hypermethylation-low expression genes were obtained by overlapping 1534 hypermethylation genes and 2623 down-regulated genes (Fig. 1). The representative heat map of GSE44076 (top 50 up-regulated and down-regulated genes) was shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 1.

Identification of aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes in gene expression datasets (GSE68468, GSE44076) and gene methylation datasets (GSE29490, GSE17648) a hypomethylation and up-regulated genes; b hypermethylation and down-regulated genes

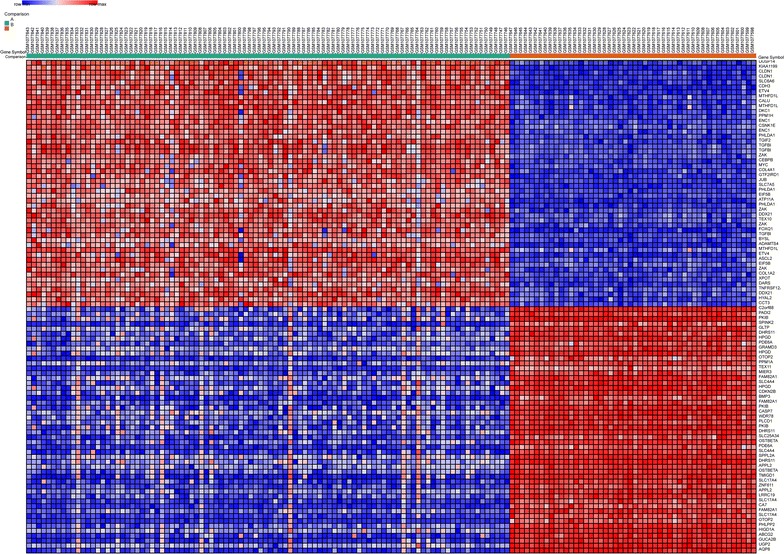

Fig. 2.

Representative heat map of the top 100 differentially expressed genes in dataset GSE44076 (50 up-regulated genes and 50 down-regulated genes). Red up-regulation; blue down-regulation

GO functional enrichment analysis

The top 5 significant terms of GO enrichment analysis in DAVID were illustrated in Table 1. Hypomethylation-high expression genes were enriched in biological processes (BP) of response to wounding, inflammatory response, cell proliferation, cell adhesion and biological adhesion. As for molecular function (MF), these genes showed enrichment in identical protein binding, cytokine activity, endopeptidase activity, heparin binding, protein binding and bridging. Besides, cell component (CC) indicated enrichment predominantly at extracellular region, which indicated that hypomethylation-high expression genes might play a critical role in tumor microenvironment of CRC (Table 2).

Table 1.

Gene ontology analysis of aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes in colorectal cancer

| Category | GO analysis | Term | Gene count | % | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylation and high expression | |||||

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0009611~response to wounding | 37 | 9.00 | 9.44E−08 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006954~inflammatory response | 25 | 6.08 | 3.48E−06 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0008283~cell proliferation | 29 | 7.06 | 7.95E−06 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007155~cell adhesion | 37 | 9.00 | 5.54E−05 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0022610~biological adhesion | 37 | 9.00 | 5.55E−05 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005576~extracellular region | 92 | 22.38 | 2.01E−08 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421~extracellular region part | 55 | 13.38 | 3.78E−08 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615~extracellular space | 42 | 10.22 | 4.12E−07 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005578~proteinaceous extracellular matrix | 21 | 5.11 | 2.45E−04 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005625~soluble fraction | 20 | 4.87 | 5.01E−04 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0042802~identical protein binding | 35 | 8.52 | 8.25E−05 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005125~cytokine activity | 15 | 3.65 | 6.69E−04 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0004175~endopeptidase activity | 21 | 5.11 | 2.33E−03 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0030674~protein binding, bridging | 9 | 2.19 | 3.39E−03 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0008201~heparin binding | 9 | 2.19 | 5.90E−03 | |

| Hypermethylation and low expression | |||||

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007267~cell–cell signaling | 29 | 12.13 | 3.32E−07 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0019226~transmission of nerve impulse | 18 | 7.53 | 4.70E−05 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0031644~regulation of neurological system process | 11 | 4.60 | 1.72E−04 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0007610~behavior | 20 | 8.37 | 1.90E−04 | |

| GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0030182~neuron differentiation | 19 | 7.95 | 2.35E−04 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044459~plasma membrane part | 64 | 26.78 | 2.13E−09 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005886~plasma membrane | 84 | 35.15 | 5.38E−07 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0043005~neuron projection | 19 | 7.95 | 1.13E−06 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005887~integral to plasma membrane | 38 | 15.90 | 1.67E−06 | |

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0031226~intrinsic to plasma membrane | 38 | 15.90 | 2.85E−06 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0003700~transcription factor activity | 38 | 15.90 | 2.48E−07 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0022836~gated channel activity | 16 | 6.69 | 9.15E−05 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0015267~channel activity | 18 | 7.53 | 2.17E−04 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0022803~passive transmembrane transporter activity | 18 | 7.53 | 2.23E−04 | |

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005216~ion channel activity | 17 | 7.11 | 3.17E−04 | |

Table 2.

KEGG pathway analysis of aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes in colorectal cancer

| Pathway ID | Pathway name | Gene no. | % | P value | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylation and high expression | |||||

| hsa04060 | Cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction | 20 | 4.87 | 5.86E−04 | CXCL1, IL2RA, LTBR, CXCL3, IL21R, CXCL2, MET, CXCL9, TNFSF15, TNFRSF4, CCL18, LIF, INHBA, TNFRSF9, TNFSF11, IL23A, PRLR, CCL20, IL20RA, ACVR1 |

| hsa04115 | p53 signaling pathway | 8 | 1.95 | 5.54E−03 | CCND1, SERPINB5, CD82, RRM2, TSC2, CASP8, PMAIP1, ATM |

| hsa04110 | Cell cycle | 9 | 2.19 | 0.045 | CCND1, PKMYT1, PRKDC, RB1, CDC16, CDC27, ATM, WEE1, TFDP1 |

| Hypermethylation and low expression | |||||

| hsa04020 | Calcium signaling pathway | 12 | 5.02 | 7.80E−04 | EGFR, EDNRB, ADCY2, PTGER3, PDE1B, PDE1C, DRD5, GRIN2A, PLCD1, ITPKB, CAMK2B, PTGFR |

| hsa04950 | Maturity onset diabetes of the young | 5 | 2.09 | 1.45E−03 | HHEX, NEUROD1, HNF4G, NEUROG3, NKX2-2 |

| hsa04514 | Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 8 | 3.35 | 0.017 | NCAM1, CD8A, ITGA8, NLGN4X, CNTN1, ITGA4, JAM2, HLA-G |

| hsa04080 | Neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction | 11 | 4.60 | 0.033 | EDNRB, SSTR2, PTGER3, GABRB3, GRIK1, GRIK2, DRD5, GRIN2A, GRIA3, PTGFR, VIPR2 |

| hsa04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 9 | 3.77 | 0.035 | DOCK2, ADCY2, CXCL14, TIAM1, HCK, PIK3CD, CCR10, RAP1A, ELMO1 |

| hsa04666 | Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis | 6 | 2.51 | 0.043 | DOCK2, HCK, PIK3CD, ARF6, AMPH, DNM2 |

For hypermethylation-low expression genes, enriched biological processes included cell–cell signaling, transmission of nerve impulse, regulation of neurological system process and neuron differentiation. Molecular function enrichment indicated transcription factor activity, gated channel activity, channel activity, passive transmembrane transporter activity and ion channel activity. Additionally, cell component displayed plasma membrane and neuron projection.

KEGG pathway analysis

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis suggested that hypomethylation-high expression genes were significantly enriched in pathways including cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, p53 signaling and cell cycle. Hypermethylation-low expression genes demonstrated enrichment in pathways of calcium signaling pathway, maturity onset diabetes of the young, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, chemokine signaling and Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis.

PPI network construction, module analysis and hub gene selection

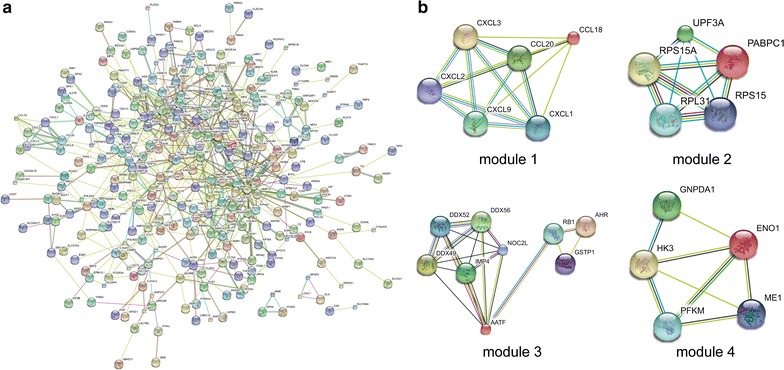

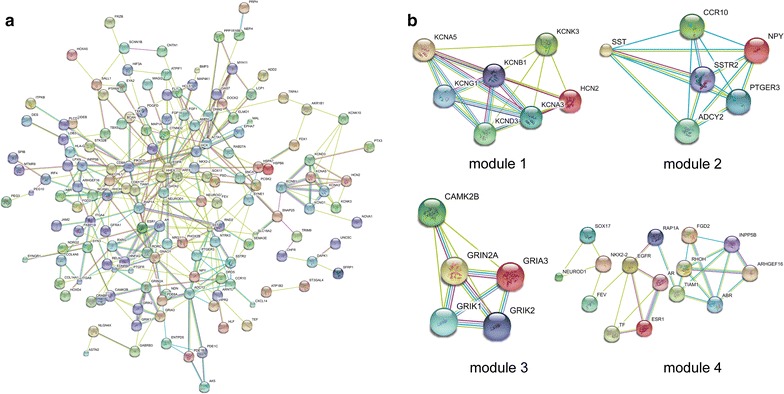

PPI networks were constructed on the basis of STRING database. Module analysis was conducted by MCODE in Cytoscape software. For hypomethylation-high expression genes, PPI network was shown in Fig. 3a and top four modules were displayed in Fig. 3b. Significant core modules demonstrated functions of chemokine signaling, ribosome, nucleic acid binding, carbon metabolism, cell cycle and proteasome (Table 3). Top five hub genes were CAD, CCND1, ATM, RB1 and MET. PPI network of hypermethylation-low expression genes was illustrated in Fig. 4a and top four modules were displayed in Fig. 4b. Significant key modules showed functions including synaptic transmission, gastric acid secretion, glutamatergic synapse and cell fate specification. Top five hub genes included EGFR, ACTA1, SST, ESR1 and DNM2.

Fig. 3.

PPI network and top four modules of hypomethylation-high expression genes (a PPI network; b top module 1–4)

Table 3.

Module analysis of the protein–protein interaction network

| Category | Module | Function description | FDR | Nodes | Genes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylation and high expression | |||||

| 1 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 1.14E−10 | 6 | CCL18, CXCL2, CXCL1, CCL20, CXCL9, CXCL3 | |

| 2 | Ribosome | 6.80E−04 | 5 | RPL31, PABPC1, UPF3A, RPS15A, RPS15 | |

| 3 | Nucleic acid binding | 0.0195 | 9 | DDX49, AHR, GSTP1, RB1, AATF, DDX56, NOC2L, IMP4, DDX52 | |

| 4 | Carbon metabolism | 3.43E−04 | 5 | GNPDA1, PFKM, ENO1, ME1, HK3 | |

| 5 | Cell cycle | 3.01E−10 | 8 | CDC16, PKMYT1, CDC27, TFDP1, SMARCAL1, ATM, RECQL5, WEE1 | |

| 6 | Proteasome | 0.0344 | 8 | FGFR1, SOX9, PSMD6, FOXD1, CCND1, MSX1, PSMF1, FOXA2 | |

| Hypermethylation and low expression | |||||

| 1 | Synaptic transmission | 1.04E−07 | 7 | KCND3, KCNG1, KCNB1, HCN2, KCNK3, KCNA5, KCNA3 | |

| 2 | Gastric acid secretion | 2.19E−04 | 6 | SST, NPY, SSTR2, CCR10, PTGER3, ADCY2 | |

| 3 | Glutamatergic synapse | 1.09E−06 | 5 | GRIK1, GRIK2, GRIA3, GRIN2A, CAMK2B | |

| 4 | Cell fate specification | 9.20E−03 | 15 | ARHGEF16, RHOH, TIAM1, ABR, RAP1A, NEUROD1, AR, ESR1, EGFR, TF, FEV, INPP5B, SOX17, FGD2, NKX2-2 | |

Fig. 4.

PPI network and top four modules of hypermethylation-low expression genes (a PPI network; b top module 1–4)

Validation of the hub genes in TCGA database

Hypomethylation-high expression hub genes and hypermethylation-low expression hub genes were then validated in another database TCGA to confirm the results. The outcome was summarized in Table 4. For most of the hub genes, the methylation and expression status were still significant altered and same with our results, which suggest the stability and reliability of the findings.

Table 4.

Validation of the hub genes in TCGA database

| Category | Hub gene | Methylation status | P value | Expression status | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hypomethylation and high expression | |||||

| CAD | Hypomethylation | 5.55E−16 | Up-regulated | 3.88E−18 | |

| CCND1 | Hypomethylation | 0.032 | Up-regulated | 7.26E−17 | |

| ATM | – | – | Up-regulated | 0.006 | |

| RB1 | Hypomethylation | 5.27E−03 | Up-regulated | 1.17E−11 | |

| DNM2 | Hypomethylation | 1.36E−13 | Up-regulated | 5.23E−08 | |

| Hypermethylation and low expression | |||||

| EGFR | Hypermethylation | 4.65E−14 | Down-regulated | 7.20E−21 | |

| ACTA1 | Hypermethylation | 1.64E−14 | – | – | |

| SST | Hypermethylation | 9.67E−14 | Down-regulated | 2.22E−31 | |

| ESR1 | Hypermethylation | 1.18E−14 | Down-regulated | 9.62E−20 | |

| DNM2 | Hypermethylation | 5.43E−06 | – | – | |

Discussion

Elucidating the underlying mechanisms of the initiation and development of CRC would greatly benefit the diagnosis, treatment and prognosis evaluation. In this study, we identified 411 hypomethylation-high expression genes and 239 hypermethylation-low expression genes through analyzing available data of gene expression (GSE68468, GSE44076) and gene methylation (GSE29490, GSE17648) microarrays in CRC by multiple bioinformatics tools. Enrichment of these genes demonstrated certain pathways and hub genes affected by aberrant methylation, which may provide novel insights for unraveling pathogenesis of CRC.

As was suggested by DAVID analysis, hypomethylation-high expression genes in CRC were enriched in biological processes of response to wounding, inflammatory response, cell proliferation, cell adhesion and biological adhesion. Molecular function of GO analysis showed enrichment in identical protein binding, cytokine activity, endopeptidase activity, heparin binding, protein binding and bridging. It is reasonable because frequent cell proliferation and loss of cell adhesion is an apparent hallmark of cancers including CRC [13]. Chronic inflammatory and wounding conditions in the intestinal tract have also been found to increase CRC risk [14]. As main inflammatory mediators, cytokines critically determine the pro- or anti-tumorigenic signals within the environment of CRC [15]. KEGG pathway enrichment analysis suggested significant enrichment in pathways including cytokine–cytokine receptor interaction, p53 signaling and cell cycle. It was consistent with the fact that p53 signaling was frequently dysregulated in CRC [16].

PPI network of hypomethylation-high expression genes illustrated the overview of their functional connections, of which top 5 hub genes were also selected: CAD, CCND1, ATM, RB1 and MET. CAD gene encodes a trifunctional protein which is associated with the enzymatic activities of the first 3 enzymes in the 6-step pathway of pyrimidine biosynthesis [17]. Regulatory component of the cyclin D1-CDK4 (DC) complex that phosphorylates and inhibits members of the retinoblastoma (RB) protein family including RB1 and regulates the cell-cycle during G1/S transition [18]. Therefore, CCND1 and RB1 might be candidate genes affected by aberrant methylation that modulate cell cycle during CRC progression. ATM gene encodes a protein named serine/threonine protein kinase, which is a crucial cell cycle checkpoint kinase responsible for regulating a wide variety of downstream proteins including tumor suppressor protein p53 [19]. Aberrant methylation of the promoter region of ATM has been found to associate with increased radiosensitivity in human CRC cell-line HCT-116 [20]. Besides, aberrant methylation of ATM was also detected in colorectal cancers and adenomas [21, 22]. MET gene encodes a member of the receptor tyrosine kinase family of proteins which regulate various physiological processes including proliferation, morphogenesis and survival, but little is known about its role in CRC.

Module analysis of the PPI network for hypomethylation-high expression genes suggested that chemokine signaling, ribosome, nucleic acid binding, carbon metabolism, cell cycle and proteasome might be involved in CRC development. Ribosome, nucleic acid binding and cell cycle were all critical cellular processes during DNA replication and translation, which tend to be disordered in cancer. Chemokine signaling has been found to influence CRC invasion and/or metastasis via changing tumor microenvironment [23]. As an essential process for the degradation of proteins and maintenance for homeostasis in eukaryotic cells, ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) alternations have been linked to gastrointestinal malignancies including CRC [24]. Our findings highlighted the probable importance of the regulation of these key biological behaviors by aberrantly hypomethylation in CRC, which warranted further investigations to confirm.

For hypermethylation-low expression genes in CRC, GO analysis showed that enriched biological processes were cell–cell signaling, transmission of nerve impulse, regulation of neurological system process and neuron differentiation. Recently, nerve ablation was found to delay development of precancerous lesions and inhibit tumor growth and metastasis [25], but relevant studies were still limited in CRC. The regulation of hypermethylation for nerve related genes might become promising research direction for CRC development in the future. Molecular function enrichment revealed transcription factor activity, channel activity and passive transmembrane transporter activity. KEGG analysis displayed enrichment in pathways of calcium signaling, maturity onset diabetes of the young, cell adhesion molecules (CAMs), neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction, chemokine signaling and Fc gamma R-mediated phagocytosis. These results outlined the important roles of transcription factor, cellular channel and adhesion in CRC, which were candidate study targets for their underlying mechanisms of hypermethylation and dysregulation.

After constructing PPI network for hypermethylation-low expression genes, top 5 hub genes appeared to be EGFR, ACTA1, SST, ESR1 and DNM2. As the most significant hub gene, promoter hypermethylation of EGFR gene has been proved to be related with worse survival of CRC patients who received cetuximab treatment [26]. Additionally, upregulation of EREG expression through promoter demethylation might activate the EGFR pathway during the genesis of CRC [27], which also emphasize the role of aberrant methylation in EGFR pathway. Somatostatin, encoded by SST gene, is a hormone important for regulation of the endocrine system and proliferation of both normal and tumorigenic cells [28]. Promoter hypermethylation-related decreased somatostatin production was found to promote uncontrolled cell proliferation in CRC [29], and methylation of serum SST gene might be an independent prognostic marker in CRC [30]. These results all suggested that SST gene methylation may serve as a critical regulator during CRC development. Estrogen receptor, encoded by ESR1 gene, is important for hormone binding, DNA binding and activation of transcription. And aberrant methylation of ESR1 gene in CRC has previously been discovered by several studies [31, 32]. ACTA1 gene encodes a protein belonging to actin family, which exert functions in cell motility, structure and integrity [33]. DNM2 gene encodes dynamin-2, which is subfamily of GTP-binding proteins and implicated in cell processes such as endocytosis and cell motility [34]. The roles of ACTA1 and DNM2 and their methylation status in CRC require further explorations.

Core modules within PPI network of hypermethylation-low expression genes possessed functions including synaptic transmission, gastric acid secretion, glutamatergic synapse and cell fate specification. Up to now, little is known concerning the effect of glutamatergic synapse and synaptic transmission in CRC as well as its regulation by aberrant methylation. Cell fate specification and differentiation were key procedure during cancer development [13]. According to our analysis, hypermethylation might modulate key genes responsible for cell fate determination, thus influencing the progression of CRC. It is worth noting that biological process of gastric acid secretion might also play a critical role in colorectal carcinogenesis. Gastrin has been identified as a major regulator of gastric acid secretion [35] and it also exerts effects in different tissues promoting cell division and inhibiting apoptosis [36]. Non-amidated gastrins have been proved to accelerate the development of CRC [37]. Moreover, progastrin expression level was higher in CRC than that in normal colorectal mucosa [38], and CRC patients have elevated circulating concentrations of Gamide and total gastrins [39]. The specific roles of these key modules affected by hypermethylation in the occurrence and progression of CRC still need future experiments to elucidate.

Several limitations should be acknowledged in this investigation. The clinical parameters and prognosis were not analyzed in this study due to the availability of data. Besides, the influence of aberrantly methylation on gene expression was only validated in TCGA database. Further molecular experiments are needed to better confirm the findings of the identified genes and pathways in CRC of our investigation.

Conclusion

In summary, our study indicated a series of aberrantly methylated-differentially expressed genes and pathways in CRC by joint bioinformatics analysis of both gene expression and gene methylation microarrays, which may contribute to the finding of molecular mechanisms underlying the initiation and development of CRC. Hub genes including CAD, CCND1, ATM, RB1, MET, EGFR, ACTA1, SST, ESR1 and DNM2 might serve as aberrantly methylation-based biomarkers for precise diagnosis and treatment of CRC in the future. Compared with individual investigation, this study is possible to come up with more reliable and accurate screening results via overlapping relevant data sets. Further molecular experiments are needed to confirm the findings of the identified candidate genes in CRC.

Authors’ contributions

JL and HL collected the data; LS and ZW performed the statistical analysis; JL and LS wrote the paper; CX and YY conceived the study. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Availability of data and materials

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Funding

This study is supported by grants from Public Welfare Foundation of Liaoning Province (No. 2015005002) and the National Science and Technology Support Program (2015BAI13B07).

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Abbreviations

- CRC

colorectal cancer

- DEG

differentially expressed gene

- DMG

differentially methylated gene

- GO

gene ontology

- KEGG

Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes

- PPI

protein–protein interaction

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes

- TCGA

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- BP

biological processes

- MF

molecular function

- CC

cell component

Contributor Information

Jingwei Liu, Email: jwliu@cmu.edu.cn.

Hao Li, Email: drlee0103@outlook.com.

Liping Sun, Email: lipingsun@hotmail.com.

Zhenning Wang, Email: josieon826@sina.cn.

Chengzhong Xing, Email: xcz1966@126.com.

Yuan Yuan, Email: yuanyuan@cmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Nishihara R, Ogino S, Chan AT. Colorectal-cancer incidence and mortality after screening. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(24):2355. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1313116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fearon ER. Molecular genetics of colorectal cancer. Annu Rev Pathol. 2011;6:479–507. doi: 10.1146/annurev-pathol-011110-130235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Cancer genes and the pathways they control. Nat Med. 2004;10(8):789–799. doi: 10.1038/nm1087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bird A. DNA methylation patterns and epigenetic memory. Genes Dev. 2002;16(1):6–21. doi: 10.1101/gad.947102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baylin SB, Jones PA. A decade of exploring the cancer epigenome—biological and translational implications. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):726–734. doi: 10.1038/nrc3130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.van Rijnsoever M, Grieu F, Elsaleh H, Joseph D, Iacopetta B. Characterisation of colorectal cancers showing hypermethylation at multiple CpG islands. Gut. 2002;51(6):797–802. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulasingam V, Diamandis EP. Strategies for discovering novel cancer biomarkers through utilization of emerging technologies. Nat Clin Pract Oncol. 2008;5(10):588–599. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nannini M, Pantaleo MA, Maleddu A, Astolfi A, Formica S, Biasco G. Gene expression profiling in colorectal cancer using microarray technologies: results and perspectives. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35(3):201–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2008.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmona FJ, Azuara D, Berenguer-Llergo A, Fernandez AF, Biondo S, de Oca J, Rodriguez-Moranta F, Salazar R, Villanueva A, Fraga MF, et al. DNA methylation biomarkers for noninvasive diagnosis of colorectal cancer. Cancer Prev Res. 2013;6(7):656–665. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dennis G, Jr, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, Lempicki RA. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4(5):P3. doi: 10.1186/gb-2003-4-5-p3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gene Ontology Consortium. The gene ontology (GO) project in 2006. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34 (Database issue):D322–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Kanehisa M, Goto S. KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2000;28(1):27–30. doi: 10.1093/nar/28.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144(5):646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carethers JM, Jung BH. Genetics and genetic biomarkers in sporadic colorectal cancer. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(5):1177–1190. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2015.06.047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mager LF, Wasmer MH, Rau TT, Krebs P. Cytokine-induced modulation of colorectal cancer. Front Oncol. 2016;6:96. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2016.00096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stracquadanio G, Wang X, Wallace MD, Grawenda AM, Zhang P, Hewitt J, Zeron-Medina J, Castro-Giner F, Tomlinson IP, Goding CR, et al. The importance of p53 pathway genetics in inherited and somatic cancer genomes. Nat Rev Cancer. 2016;16(4):251–265. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2016.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grande-Garcia A, Lallous N, Diaz-Tejada C, Ramon-Maiques S. Structure, functional characterization, and evolution of the dihydroorotase domain of human CAD. Structure. 2014;22(2):185–198. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.10.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jirawatnotai S, Sharma S, Michowski W, Suktitipat B, Geng Y, Quackenbush J, Elias JE, Gygi SP, Wang YE, Sicinski P. The cyclin D1-CDK4 oncogenic interactome enables identification of potential novel oncogenes and clinical prognosis. Cell Cycle. 2014;13(18):2889–2900. doi: 10.4161/15384101.2014.946850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brown KD, Barlow C, Wynshaw-Boris A. Multiple ATM-dependent pathways: an explanation for pleiotropy. Am J Hum Genet. 1999;64(1):46–50. doi: 10.1086/302223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kim WJ, Vo QN, Shrivastav M, Lataxes TA, Brown KD. Aberrant methylation of the ATM promoter correlates with increased radiosensitivity in a human colorectal tumor cell line. Oncogene. 2002;21(24):3864–3871. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bai AH, Tong JH, To KF, Chan MW, Man EP, Lo KW, Lee JF, Sung JJ, Leung WK. Promoter hypermethylation of tumor-related genes in the progression of colorectal neoplasia. Int J Cancer. 2004;112(5):846–853. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rengucci C, De Maio G, Casadei Gardini A, Zucca M, Scarpi E, Zingaretti C, Foschi G, Tumedei MM, Molinari C, Saragoni L, et al. Promoter methylation of tumor suppressor genes in pre-neoplastic lesions; potential marker of disease recurrence. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2014;33:65. doi: 10.1186/s13046-014-0065-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itatani Y, Kawada K, Inamoto S, Yamamoto T, Ogawa R, Taketo MM, Sakai Y. The role of chemokines in promoting colorectal cancer invasion/metastasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(5):643. doi: 10.3390/ijms17050643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Voutsadakis IA. The ubiquitin–proteasome system in colorectal cancer. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2008;1782(12):800–808. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saloman JL, Albers KM, Rhim AD, Davis BM. Can stopping nerves, stop cancer? Trends Neurosci. 2016;39(12):880–889. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2016.10.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scartozzi M, Bearzi I, Mandolesi A, Giampieri R, Faloppi L, Galizia E, Loupakis F, Zaniboni A, Zorzi F, Biscotti T, et al. Epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) gene promoter methylation and cetuximab treatment in colorectal cancer patients. Br J Cancer. 2011;104(11):1786–1790. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2011.161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Qu X, Sandmann T, Frierson H, Jr, Fu L, Fuentes E, Walter K, Okrah K, Rumpel C, Moskaluk C, Lu S, et al. Integrated genomic analysis of colorectal cancer progression reveals activation of EGFR through demethylation of the EREG promoter. Oncogene. 2016;35(50):6403–6415. doi: 10.1038/onc.2016.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Theodoropoulou M, Stalla GK. Somatostatin receptors: from signaling to clinical practice. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2013;34(3):228–252. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2013.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Leiszter K, Sipos F, Galamb O, Krenacs T, Veres G, Wichmann B, Furi I, Kalmar A, Patai AV, Toth K, et al. Promoter hypermethylation-related reduced somatostatin production promotes uncontrolled cell proliferation in colorectal cancer. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(2):e0118332. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0118332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu Y, Chew MH, Tham CK, Tang CL, Ong SY, Zhao Y. Methylation of serum SST gene is an independent prognostic marker in colorectal cancer. Am J Cancer Res. 2016;6(9):2098–2108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sahnane N, Magnoli F, Bernasconi B, Tibiletti MG, Romualdi C, Pedroni M, Ponz de Leon M, Magnani G, Reggiani-Bonetti L, Bertario L, et al. Aberrant DNA methylation profiles of inherited and sporadic colorectal cancer. Clin Epigenetics. 2015;7:131. doi: 10.1186/s13148-015-0165-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Magnani G, Furlan D, Sahnane N, Reggiani Bonetti L, Domati F, Pedroni M. Molecular features and methylation status in early onset (</=40 years) colorectal cancer: a population based, case–control study. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:132190. doi: 10.1155/2015/132190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zukosky K, Meilleur K, Traynor BJ, Dastgir J, Medne L, Devoto M, Collins J, Rooney J, Zou Y, Yang ML, et al. Association of a novel ACTA1 mutation with a dominant progressive scapuloperoneal myopathy in an extended family. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(6):689–698. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gonzalez-Jamett AM, Momboisse F, Haro-Acuna V, Bevilacqua JA, Caviedes P, Cardenas AM. Dynamin-2 function and dysfunction along the secretory pathway. Front Endocrinol. 2013;4:126. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2013.00126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schubert ML. Gastric secretion. Curr opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30(6):578–582. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0000000000000125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grabowska AM, Watson SA. Role of gastrin peptides in carcinogenesis. Cancer Lett. 2007;257(1):1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Aly A, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS. Gastrins, cholecystokinins and gastrointestinal cancer. Biochem Biophys Acta. 2004;1704(1):1–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbcan.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Van Solinge WW, Nielsen FC, Friis-Hansen L, Falkmer UG, Rehfeld JF. Expression but incomplete maturation of progastrin in colorectal carcinomas. Gastroenterology. 1993;104(4):1099–1107. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90279-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ciccotosto GD, McLeish A, Hardy KJ, Shulkes A. Expression, processing, and secretion of gastrin in patients with colorectal carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(4):1142–1153. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(95)90572-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.