Dermatological toxicities represent the most frequent immune-related adverse events (irAEs) induced by immune checkpoint inhibitors (1, 2). Safety profiles for anti-CTLA-4 inhibitors (ipilimumab) and agents targeting the programmed cell death (PD-1) receptor (nivolumab, pembrolizumab) appear to be very similar, yet a lower frequency is observed with the latter (2). A non-specific maculopapular rash represents the most frequent cutaneous toxicity of anti-PD-1 inhibitors, with a calculated all-grade incidence of 14.3% and 16.7% for nivolumab and pembrolizumab, respectively (3). These lesions mostly remain mild/moderate, self-limiting, and manageable with topical and/or oral steroids. Other dermatological complications can also occur, including pruritus, xerosis, alopecia, mucosal involvement, autoimmune disorders and vitiligo, the latter being exclusively described in patients treated for melanoma (1–3). More recently, additional skin adverse events have been described, including lichenoid reactions, blistering disorders or occurrence and exacerbation of psoriasis (1–4). We report here 6 patients who developed a mid-facial rash suggestive of papulopustular rosacea, triggered or exacerbated by nivolumab therapy, which has not been reported so far in association with anti-PD-1 therapy.

CASE REPORTS

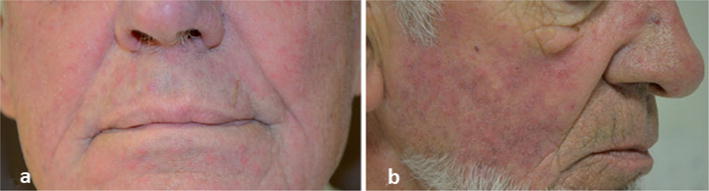

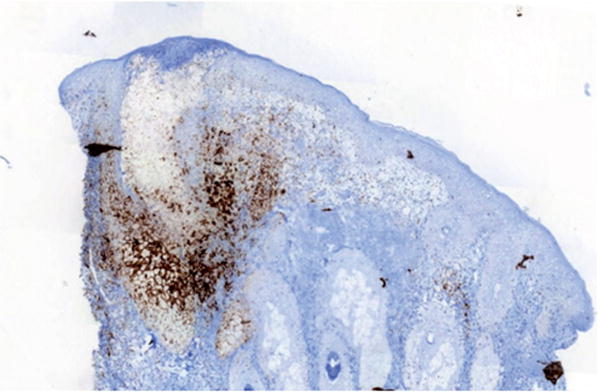

All patients (5 men, 1 woman) were treated for different types of metastatic solid cancers (Table I). Lesions occurred after 1–19 cycles of nivolumab therapy (3 mg/kg every 2 weeks). They were mostly localized on the medial part of the face, with a characteristic combination of papules and pustules on an underlying erythema, consistent with papulopustular rosacea. Symptoms were of mild intensity in all cases (grade 1 papulopustular rash) (Fig. 1a) except for one patient, who presented with an intolerable grade 2 toxicity (Fig. 1b). Lesions were easily managed with symptomatic treatment (topical metrodinazole and/or oral doxycycline), leading to a significant improvement in all cases. Nivolumab therapy was delayed in one patient and resumed after one cycle. Cutaneous biopsy was performed on the patient with grade 2 toxicity, which demonstrated characteristic histopathological features of papulopustular rosacea, with a predominant perivascular and perifollicular CD3+ T-cell infiltrate, associated with small and superficial dilated blood vessels. In addition, PD-L1 immunostaining revealed a strong positivity in the perifollicular infiltrate cells (60%) (Fig. 2). Close examination of the patients’ history suggested pre-existing erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in 3 patients.

Table I.

Clinical description of reported patients

| Case No./Sex/Age, years | Underlying malignancies | Treatment | Time to onset | Clinical gradinga | Management | Outcome | Pre-existing rosaceab |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1/F/48 | Melanoma | Nivolumab | 19 cycles | Grade 1 | Topical metronidazole | Regression | No |

| 2/M/83 | Renal cell carcinoma | Nivolumab | 1 cycle | Grade 1 | Topical metronidazole | Regression | Yes |

| 3/M/68 | Tonsillar carcinoma | Nivolumab | 4 cycles | Grade 1 | Topical metronidazole | Regression | No |

| 4/M/70 | Lung cancer | Nivolumab | 16 cycles | Grade 2 (intolerable) | Temporary discontinuation, topical metronidazole, oral doxycycline (100 mg/day) | Regression | Yes |

| 5/M/58 | Renal cell carcinoma | 2 cycles of nivolumab+ipilimumab, followed by nivolumab in monotherapy | 8 cycles | Grade 1 | Topical metronidazole | Complete resolutionc | Yes |

| 6/M/66 | Melanoma | 4 cycles of nivolumab+ipilimumab, followed by nivolumab in monotherapy | 15 cycles | Grade 1 | Topical metronidazole, oral doxycycline (100 mg/day) | Complete resolutionc | No |

Following National Cancer Institute CTCae V4.02.

erythemato-telangiectatic rosacea.

4 and 8 weeks after the last dose of nivolumab, respectively.

Fig. 1. Clinical examples of rosacea in the study.

(a) Grade 1 papulopustular rosacea in case 2 and (b) intolerable grade 2 papulopustular rosacea in case 4 induced by nivolumab therapy.

Fig. 2.

PD-L1 immunostaining individualizing a strong positivity in the lympho-histiocytic infiltrate, associated with exocytosis into the pilosebaceous follicle (×50 magnification Ventana Ultraview DAB Detection Kit; Antigen retrieval was a standard automated process on the Ventana BenchMark XT clone SP142, Spring Bioscience, Pleasanton, CA, USA).

DISCUSSION

Development or exacerbation of papulopustular rosacea with anti-PD-1 therapy has not been described previously. We cannot, however, rule out the possibility that this event is under-reported during its development because of unperformed complete skin examination by investigators. Moreover, acneiform rash has been infrequently reported with anti-PD-1 agents, but only by non-dermatologist investigators (5). This so-called “acneiform” rash could potentially correspond, at least in part, to a papulopustular rosacea. The pathophysiology of rosacea remains poorly understood, involving complex dysregulation of the innate immune, vascular and nervous systems (6). However, it has been postulated that the adaptive immune system, involving CD4+ Th1/Th17 cell activities, plays a significant role in the development of all subtypes of rosacea (6, 7). In addition, it has been demonstrated that blockade of the PD-1 receptor may promote Th1/Th17 pathways (8). We therefore can speculate that anti-PD-1 monoclonal antibodies may favour the development of either psoriasis (4) or rosacea in predisposed patients. Clinicians should be aware of this new dermatological adverse event, which remains, in our experience, self-limiting, but may lead to temporary interruption. Early recognition and appropriate management also appear crucial to prevent a negative impact on patients’ quality of life.

Acknowledgments

VS has a speaking, consultant or advisory role with Roche, GlaxoSmithKline, Pierre Fabre, Merck, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Bayer and Boehringer Ingelheim. MEL receives research support from Roche/Genentech, Berg, the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P20 CA008748; consulting fees from Boehringer Ingelheim, Galderma, Amgen, Roche/Genentech.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: JM has a speaking, consultant or advisory role with Roche, Bristol-Myers Squibb, PUMA, Pfizer, Novartis, Astra Zeneca and Boehringer Ingelheim EB, ET, CC and AZ declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Hofmann L, Forschner A, Loquai C, Goldinger SM, Zimmer L, Ugurel S, et al. Cutaneous, gastrointestinal, hepatic, endocrine, and renal side-effects of anti PD-1 therapy. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:190–209. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sibaud V, Meyer N, Lamant L, Vigarios E, Mazieres J, Delord JP. Dermatologic complications of anti PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint antibodies. Curr Opin Oncol. 2016;28:254–263. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0000000000000290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Belum VR, Benhuri B, Postow MA, Hellmann MD, Lesokhin AM, Segal NH, et al. Characterisation and management of dermatologic adverse events to agents targeting the PD-1 receptor. Eur J Cancer. 2016;60:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2016.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Matsumura N, Ohtsuka M, Kikuchi N, Yamamoto T. Exacerbation of psoriasis during nivolumab therapy for metastatic melanoma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016;96:259–260. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garon EB, Rizvi NA, Hui R, Leighl N, Balmanoukian AS, Eder JP, et al. Pembrolizumab for the treatment of non-small-cell lung cancer. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:2018–2028. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1501824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melnik B. Rosacea: the blessing of the celts -An approach to pathogenesis through translational research. Acta Dermatol Venereol. 2016;96:147–156. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Buhl T, Sulk M, Nowak P, Buddenkotte J, McDonald I, Aubert J, et al. Molecular and morphological characterization of inflammatory infiltrate in rosacea reveals activation of Th1/ Th17 pathways. J Invest Dermatol. 2015;135:2198–2208. doi: 10.1038/jid.2015.141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dulos J, Carven GJ, van Boxtel SJ, Buddenkotte J, McDonald I, Aubert J, et al. PD-1 blockade augments Th1 and Th17 and suppresses Th2 responses in peripheral blood from patients with prostate and advanced melanoma cancer. J Immunother. 2012;35:169–178. doi: 10.1097/CJI.0b013e318247a4e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]