Abstract

Transcription factors play crucial roles in patterning posterior neuroectoderm. Previously, zinc finger transcription factor znfl1 was reported to be expressed in the posterior neuroectoderm of zebrafish embryos. However, its roles remain unknown. Here, we report that there are 13 copies of znfl1 in the zebrafish genome, and all the paralogues share highly identical protein sequences and cDNA sequences. When znfl1s are knocked down using a morpholino to inhibit their translation or dCas9-Eve to inhibit their transcription, the zebrafish gastrula displays reduced expression of hoxb1b, the marker gene for the posterior neuroectoderm. Further analyses reveal that diminishing znfl1s produces the decreased expressions of pou5f3, whereas overexpression of pou5f3 effectively rescues the reduced expression of hoxb1b in the posterior neuroectoderm. Additionally, knocking down znfl1s causes the reduced expression of sall4, a direct regulator of pou5f3, in the posterior neuroectoderm, and overexpression of sall4 rescues the expression of pou5f3 in the knockdown embryos. In contrast, knocking down either pou5f3 or sall4 does not affect the expressions of znfl1s. Taken together, our results demonstrate that zebrafish znfl1s control the expression of hoxb1b in the posterior neuroectoderm by acting upstream of pou5f3 and sall4.

Keywords: development, homeobox, neurodevelopment, transcription factor, zebrafish, zinc finger

Introduction

During vertebrate gastrulation, three definitive germ layers including ectoderm, mesoderm, and endoderm are formed, and the anterior–posterior axis of an embryo is determined. The ectoderm gives rise to epidermal ectoderm and neuroectoderm (1). The neuroectoderm itself is regionalized along the anterior–posterior axis of an embryonic body, resulting in the anterior neuroectoderm that forms forebrain and the posterior neuroectoderm that gives rise to midbrain, hindbrain, and spinal cord (2). The posterior neuroectoderm is transformed from the newly induced neuroectoderm by graded posteriorizing signals including fibroblast growth factor, Wnt, and retinoic acid (RA)3 (3).

Transcription factors including zinc finger transcription factors (4, 5), POU domain proteins (6, 7), and homeodomain proteins (8–10) have been reported to be involved in patterning the posterior neuroectoderm in vertebrate gastrula. Zinc finger transcription factors Spalt-like (Sall) are vertebrate homologues of the Drosophila Spalt. In Xenopus, xSall4 represses the expression of xPou5f3 to provide a permissive environment allowing for additional RA signals to posteriorize the neural plate (11). Zebrafish sall4 is a downstream target of cdx4 but a direct upstream gene of pou5f3 (12). POU domain transcription factor Pou5f3 is expressed in the forming mid-hindbrain boundary during organogenesis and mediates the competence to respond to Fgf8 inductive signaling in this region of zebrafish embryos (13). The zygotic pou5f3-null mutants (Zspg) do not form mid-hindbrain boundary (14). HOX genes are classified into 13 paralogous groups based on sequence homology and colinear expression during formation of the posterior central nervous system (15). In general, Hox1–Hox5 paralogue group genes are expressed in the hindbrain, whereas Hox4–Hox11 genes are detected in the spinal cord (16). Mice lacking Hoxa1 exhibit defects in hindbrain segmentation, whereas Hoxb1-null mice do not manifest defects in early hindbrain patterning (16). In zebrafish, hoxb1b is the earliest gene that is expressed in the posterior neuroectoderm of gastrula (3). Zebrafish Hoxb1b shares ancestral functions with mammalian Hoxa1 and controls progenitor cell shape and oriented cell division during anterior hindbrain neural tube morphogenesis (17).

Zebrafish zinc finger-like gene 1 (znfl1), encoding a zinc finger transcription factor, was previously reported to be expressed in the posterior nervous system of zebrafish embryos (18). However, the functional roles of znfl1 in the formation of posterior neuroectoderm remain unknown. In this study, we report that there are 13 copies of znfl1 in the zebrafish genome, and all the paralogues share highly conserved protein sequences and cDNA sequences. They are zygotically expressed during embryogenesis. By knocking down znfl1s in zebrafish embryos using a morpholino (MO) to inhibit their translation or dCas9-Eve/sgRNAs to inhibit their transcription, we demonstrate that zebrafish znfl1s pattern the posterior neuroectoderm by acting upstream of pou5f3 and sall4.

Results

Zebrafish has 13 paralogues of znfl1, and all are expressed in the posterior neuroectoderm of gastrula

Performing bioinformatics analysis, we found that there are 13 copies of znfl1 in the zebrafish genome (Table 1). Although they are located in different chromosomes and have different genomic organization, 12 of the 13 paralogues of Znfl1 (except Znfl1f) share more than 93% amino acid identity among their protein sequences and exhibit more than 95% nucleotide sequence identity among their cDNAs (Ensemble, ENSDARG00000037914). The annotation of znfl1f is incomplete, but its annotated protein and cDNA sequences share more than 96% identity with those of znfl1 (Ensemble, ENSDARG00000037914), respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

Genomic organization of different zebrafish znfl1s and the identities of their cDNA sequences and protein sequences (%)

The sequence identities of all the other 12 paralogues are compared with znfl1, respectively.

| Gene name | Old gene name | Genomic locusa | Number of exons | Number of introns | cDNA sequence identity | Protein sequence identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % | % | |||||

| znfl1 | Zinc finger-like gene 1 | 3:34522636–34527237:−1 | 2 | 1 | 100 | 100 |

| znfl1b | si:dkey-103d23.5 | 18:5625861–5627378:−1 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 94 |

| znfl1c | si:ch211–155k24.1 | 19:20559527–20564146:−1 | 2 | 1 | 95 | 93 |

| znfl1d | si:dkey-103d23.5 | 9:15900132–15904731:1 | 2 | 1 | 95 | 94 |

| znfl1e | BX004876.1 | 11:12715661–12717178:−1 | 1 | 0 | 95 | 93 |

| znfl1f b | CABZ01054718.1 | KN150451.1:13411–14916:1 | 1 | 0 | 98 | 96 |

| znfl1g | si:ch211–168h21.3 | 13:45195299–45199801:1 | 3 | 2 | 95 | 94 |

| znfl1h | si:dkey-14o18.1 | 19:9852492–9857150:−1 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 95 |

| znfl1i | si:dkey-250i3.3 | 9:31947924–31952506:−1 | 4 | 3 | 95 | 94 |

| znfl1j | si:dkey-210i3.1 | 23:17117759–17120427:1 | 2 | 1 | 95 | 94 |

| znfl1k | si:dkeyp-11g8.3 | 20:34471856–34476777:1 | 1 | 0 | 96 | 95 |

| znfl1l | si:ch211–196c10.11 | 8:23224357–23228957:1 | 2 | 1 | 96 | 96 |

| znfl1m | si:ch211–152n14.4 | 6:19444281–19448656:−1 | 3 | 2 | 96 | 95 |

a “1” denotes forward strand, whereas “−1” denotes reverse strand.

b The annotation of znfl1f is incomplete. The incomplete protein sequence is 363 amino acids long, and the cDNA is 1,506 bp long. But the incomplete sequences share 98 and 96% identity with the corresponding sequences of znfl1 cDNA and protein, respectively.

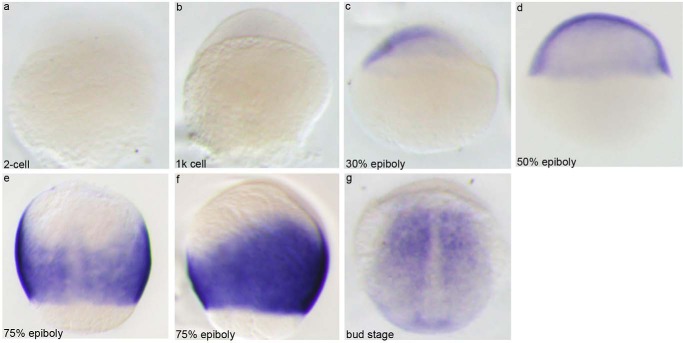

Because the 13 paralogues of znfl1s share high nucleotide sequence identity among their transcripts, we designed an antisense RNA probe to detect all their expressions during zebrafish early development by whole-mount in situ hybridization. As shown in Fig. 1, the mRNAs of znfl1s are not maternally detected (Fig. 1a). They are initially expressed at 30% epiboly (Fig. 1, b and c). The expressions are found in all the blastomeres of embryos at 50% epiboly (Fig. 1d), strongly distributed in the posterior neuroectoderm of embryos at 75% epiboly (Fig. 1, e and f), and relatively weakly present in the adaxial mesoderm of embryos at bud stage (Fig. 1g). The results confirm the previous report that znfl1 is present in the posterior neuroectoderm (18) and suggest that znfl1s are involved in patterning the formation of posterior neuroectoderm in zebrafish gastrula.

Figure 1.

Zebrafish znfl1s were expressed in the posterior neuroectoderm of gastrula. The mRNAs of zebrafish znfl1s were not present in the embryos at the two-cell stage (a) and 1,000 (1k)-cell stage (b). They were initially detected in the embryos at 30% epiboly stage (c), widely expressed in all the blastomeres of embryos at 50% epiboly (d), strongly distributed in the posterior neuroectoderm of embryos at 75% epiboly (e and f), and relatively weakly present in the adaxial mesoderm of embryos at bud stage (g). a–d and f, lateral view; e and g, dorsal view.

Knocking down znfl1s disrupts the formation of posterior neuroectoderm by reducing the expression of hoxb1b in zebrafish gastrula

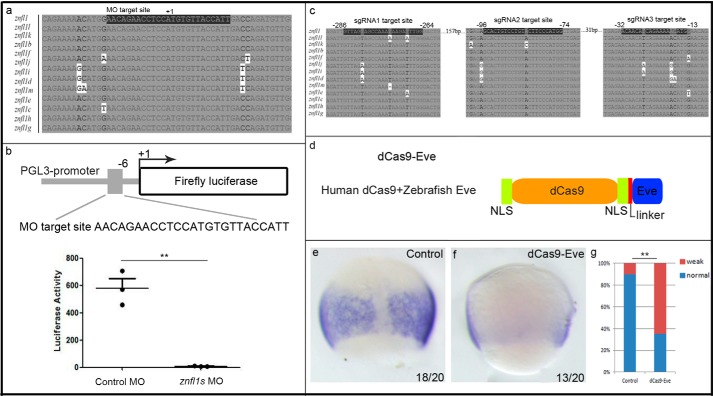

To explore the function of znfl1s in zebrafish early development, we developed two gene knockdown methods to inhibit the expressions of znfl1s in zebrafish embryos instead of performing knock-out due to the presence of 13 highly identical paralogues in zebrafish genome. Because all the transcripts of znfl1s share highly identical sequences around the start codon (Fig. 2a), we designed an antisense MO of znfl1s against the identical sequences to inhibit the translations of the mRNAs of all znfl1s. The specificity and efficiency of the znfl1MO (against all znfl1s) were determined by the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay. To perform the assay, we made the transcript containing the MO target site (the same sequence in all znfl1s) fused with the coding sequence of firefly luciferase reporter gene (Fig. 2b). After 4 ng of the znfl1 MO was microinjected into zebrafish embryos with the mRNA of the reporter genes, about 90% of the translational activity of firefly luciferase reporter was blocked (Fig. 2b). To confirm the knockdown results, we then developed a second method to deplete the expressions by using dCas9-Eve/sgRNAs (Fig. 2d) to inhibit the transcription of all znfl1s. The efficiency of dCas9-Eve guided by sgRNAs in repressing the expressions of all znfl1s was examined by whole-mount in situ hybridization. To perform the test, we made dCas9-Eve by fusing dCas9 with the putative Eve repressor domain of zebrafish Evx1 (Fig. 2d and Table 2) and prepared three sgRNAs recognizing the three potential target sites that are highly identical in all the 5′-flanking sequences upstream of the start codons of znfl1s (Fig. 2c). After dCas9-Eve mRNAs and the three sgRNAs were co-microinjected into zebrafish embryos at the one-cell stage, the expressions of znfl1s were significantly reduced in the posterior neuroectoderm of gastrula (Fig. 2, e–g). These results suggest that the two methods including blocking translation by MO and repressing transcription by dCas9-Eve are effective ways to knock down the expressions of znfl1s in zebrafish embryos.

Figure 2.

The expressions of znfl1s were effectively knocked down by morpholino and dCas9-Eve in zebrafish embryos. a, cDNA sequence alignment of partial cDNAs of znfl1s. +1 denotes the first nucleotide of the start codon. The letters highlighted in black are the MO target sequences that are the same in all paralogues of znfl1s. b, top, schematic diagram showing the translation blocker of the znfl1 MO used to inhibit the translations of the mRNAs of znfl1s. The arrow denotes the site where translation starts. Bottom, scatter plot showing the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay results revealing that the znfl1 MO represses translation of znfl1s significantly. c, genomic sequence alignment of part of the 5′-flanking sequence upstream of the start codons of znfl1s. The letters highlighted in black are the regions presumptively recognized by the three sgRNAs, respectively. The first nucleotide of start codon is denoted as +1. d, schematic diagram showing the organization of dCas9-Eve. The DNA sequences encoding the linker and Eve is shown in Table 2. NLS, nuclear localization signal. e and f, results from whole-mount in situ hybridization showing that the expressions of znfl1s were significantly inhibited in the embryos microinjected with dCas9-Eve mRNA plus three sgRNAs (f) compared with their control embryos without any microinjection (e). g, diagram showing the statistical analysis of the data derived from e and f. Error bars represent S.D. **, p < 0.01.

Table 2.

Coding sequences for linker and zebrafish Eve of dCas9-Eve

| Name | Sequences 5′–3′ |

|---|---|

| Linker | AGCCCCAAGAAGAAGAGAAAGGTGGAGGCCAGCGGAGGTACGCGTTCTAGAACC |

| Zebrafish Eve | ATGGAAACCACAATAAAGGTTTGGTTTCAGAACCGTCGCATGAAGGACAAGAGACAGCGTCTGGCTATGACCTGGCCGCATCCTGCCGACCCCGCCTTTTACACCTATATGATGAGCCATGCTGCAGCAACGGGCAGTCTGCCCTATCCATTTCAATCTCATCTTCCCCTTCCTTACTATTCTCCACTAAGCAGTGTGACTGCAGGTTCAGCCACTGCCACTGCGGGTCCATTCTCAAATCCCCTGCGCTCGCTGGATAGTTTTCGGGTGCTTTCGCATCCATACCCGCGACCTGAACTGCTGTGCGCCTTCAGACACCCATCACTGTACCCCAGCCCGGGTCATGGGCTTGGTCCCGGTGGAAGTCCATGCTCCTGCCTTGCTTGCCACGCTTCCAGTCAAACAAACGGGCTCCAACATAGATCCAATAATGCAGAATTCTCGTGTTCGCCCACGACCAGGACTGAGGCCTTCCTCACTTTCTCGCCAGCAGTCATCAGCAAATCATCTTCGGTGTCTTTGGACCAGAGGGAGGAAGTGCCACTAACTAGA |

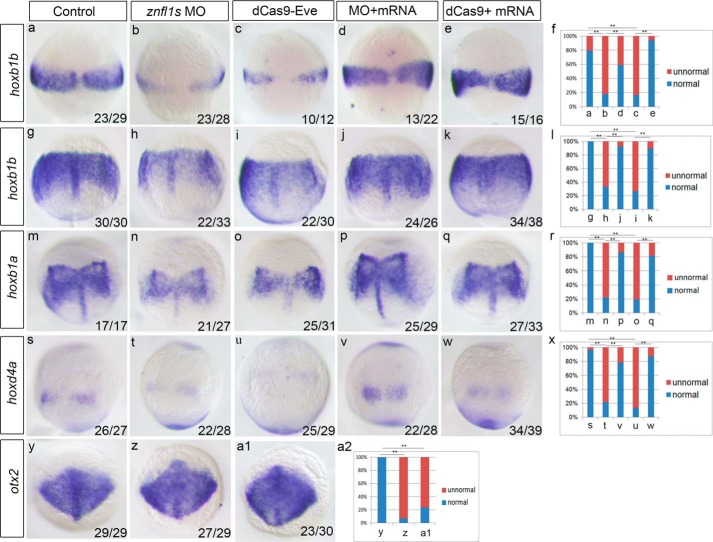

To determine whether znfl1s play crucial roles in the development of posterior neuroectoderm of zebrafish gastrula, we examined the expression of prospective posterior neural marker hoxb1b (3) in the knockdown embryos of znfl1s (referred to as the znfl1 knockdown embryos hereafter) at midgastrulation stage. The results showed that the morphants of znfl1s (referred to as the znfl1 morphants hereafter) exhibited a significantly reduced expression of hoxb1b in the embryos at 75% epiboly (Fig. 3, a, b, and f), and the decreased expression of hoxb1b in the znfl1 morphants was effectively rescued by overexpressing znfl1 mRNA (Fig. 3, a, b, d, and f). Consistently, the expression of hoxb1b was obviously decreased in the embryos in which the transcriptions of znfl1s were inhibited by dCas9-Eve (Fig. 3, a, c, and f), and overexpressing znfl1 effectively rescued the reduced expression of hoxb1b in the dCas9-Eve–microinjected embryos (Fig. 3, a, c, e, and f).

Figure 3.

Knocking down znfl1s affects the posterior neuroectoderm development through reducing the expressions of hoxb1b, hoxb1a, and hoxd4a in zebrafish gastrula. Expressions of hoxb1b, hoxb1a, hoxd4a, and otx2 were examined in 8- (a–e) and/or 10-hpf (g–k, m–q, s–w, y, z, and a1) embryos microinjected with the control MO (a, g, m, s, and y), znfl1 MO (b, h, n, t, and z), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (c, i, o, u, and a1), znfl1 MO plus znfl1 mRNA (d, j, p, and v), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs and znfl1 mRNA (e, k, q, and w), respectively. The statistical analyses of the data derived from a–e, g–k, m–q, s–w, and y–a1 are shown in f, l, r, x, and a2, respectively. All embryos except y, z, and a1 were positioned in dorsal view. Embryos y, z, and a1 were positioned in top view. **, p < 0.01.

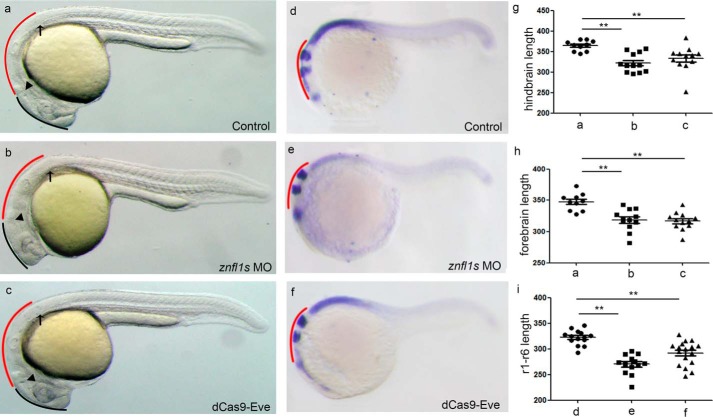

Subsequently, we determined whether the specification of posterior neuroectoderm was disrupted in the znfl1 knockdown embryos by examining the expressions of hoxb1b and hoxb1a, two marker genes for presumptive rhombomere 4 (r4) (19), and hoxd4a, a marker gene for presumptive r7 and r8 of hindbrain (20), in zebrafish embryos at the end of gastrulation. The results showed that the expressions hoxb1b, hoxb1a, and hoxd4a were all significantly decreased in the znfl1 knockdown embryos at bud stage (Fig. 3, g–i, i, l–o, r–u, and x). Moreover, the decreased expressions of hoxb1b, hoxb1a, and hoxd4a were all effectively rescued by overexpression of znfl1 in the znfl1 knockdown embryos, respectively (Fig. 3, g–x). Consistently, the expression of otx2, the prospective anterior neural maker gene, was increased and expanded in the znfl1 knockdown embryos (Fig. 3, y, z, a1, and a2). Furthermore, the hindbrain lengths of r1–r8 were significantly reduced (Fig. 4, a–c and g) in the znfl1 knockdown embryos at 24 hpf. Unexpectedly, decreased lengths of forebrain were also observed in the knockdown embryos (Fig. 4, a–c and h). Consistent with the morphological observation, the lengths of r1–r6 defined by hindbrain marker genes including eng2a (marking the midbrain–hindbrain boundary) and hoxb4a (marking the anterior boundary of r7) in the znfl1 knockdown embryos at 20 hpf (21) were significantly reduced (Fig. 4, d–f, and i). Taken together, these results strongly suggest that znfl1s are essential for the formation of posterior neuroectoderm.

Figure 4.

Knocking down znfl1s affects the hindbrain development. Morphological phenotypes of the 24-hpf embryos microinjected with the control MO (a), znfl1 MO (b), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (c) and the 20-hpf whole-mount in situ hybridized embryos microinjected with the control MO (d), znfl1 MO (e), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (f) were observed under a dissecting microscope. The statistical analyses of the data derived from a–c and d–f are shown in scatter plot diagrams in g–i, respectively. All embryos were positioned in lateral view. In a–c, the red curve shows the length of hindbrain, and the black curve shows the length of forebrain. The arrow indicates the position where the first somite starts. The arrowhead points to the midbrain–hindbrain boundary. d–f, embryos hybridized with the RNA probes detecting the expressions of eng2a, egr2b, and hoxb4a. The red curve shows the length of r1–r6. Error bars represent S.D. **, p < 0.01.

Zebrafish pou5f3 acts downstream of znfl1s to pattern the posterior neuroectoderm

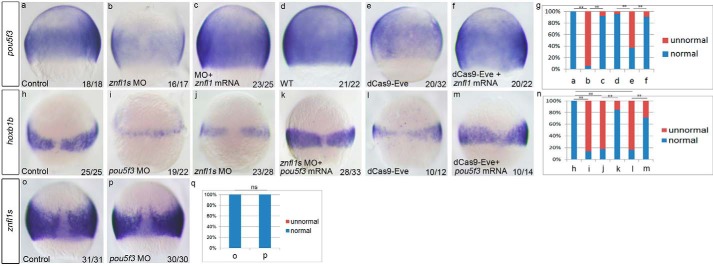

Pou5f3 is a transcription factor that has been demonstrated to regulate posterior neural fates in Xenopus embryos (11). To determine whether Pou5f3 mediates the roles of znfl1s in the formation of posterior neuroectoderm of zebrafish gastrula, we first examined the expression of pou5f3 in the znfl1 knockdown embryos. The results revealed that the embryos microinjected with either the znfl1 MO or dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs exhibited a dramatically decreased expression of pou5f3 in the posterior neuroectoderm compared with their control embryos at 75% epiboly, respectively (Fig. 5, a, b, d, e, and g). When znfl1 was overexpressed, the decreased expressions of pou5f3 were effectively rescued in the znfl1 morphants or the embryos in which the expressions of znfl1s were inhibited by dCas9-Eve, respectively (Fig. 5, a–g). Furthermore, the expressions of znfl1s were not changed in pou5f3 morphants (Fig. 5, o–q). Taken together, the results suggest that pou5f3 works downstream of znfl1s.

Figure 5.

Zebrafish znfl1s control hoxb1b expression by working upstream of pou5f3 in gastrula. Expressions of pou5f3 were examined in the embryos microinjected with the control MO (a), znfl1 MO (b), znfl1 MO together with znfl1 mRNA (c), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (e), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs and znfl1 mRNA (f) and wild-type control embryos (d) at 75% epiboly, respectively. Expressions of hoxb1b were examined in 8-hpf embryos microinjected with the control MO (h), pou5f3 MO (i), znfl1 MO (j), znfl1 MO plus pou5f3 mRNA (k), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (l), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNA and pou5f3 mRNA (m), respectively. Expressions of znfl1s were examined in the 8-hpf embryos microinjected with the control MO (o) and pou5f3 MO (p), respectively. The statistical analyses of the data derived from a–f, h–m, and o and p are shown in diagrams g, n, and q, respectively. Embryos were positioned in lateral view (a–f) or dorsal view (h–m and o–p). **, p < 0.01; ns, no significance.

We then examined the expression of hoxb1b in the pou5f3 morphants and found that it was significantly reduced (Fig. 5, i and n) like that in the znfl1 morphants (Fig. 5, j and n) and that in embryos in which the expressions of znfl1s were inhibited by dCas9-Eve (Fig. 5, l and n) compared with control embryos (Fig. 5, h and n). Moreover, the decreased expressions of hoxb1b were effectively rescued in the znfl1 morphants (Fig. 5, j, k, and n) and the embryos in which the expressions of znfl1s were inhibited by dCas9-Eve (Fig. 5, l–n) after pou5f3 mRNAs were microinjected into the two kinds of the znfl1 knockdown embryos. Taken together, these data substantiate that the function of znfl1s in posteriorizing neuroectoderm is mediated by the downstream gene pou5f3.

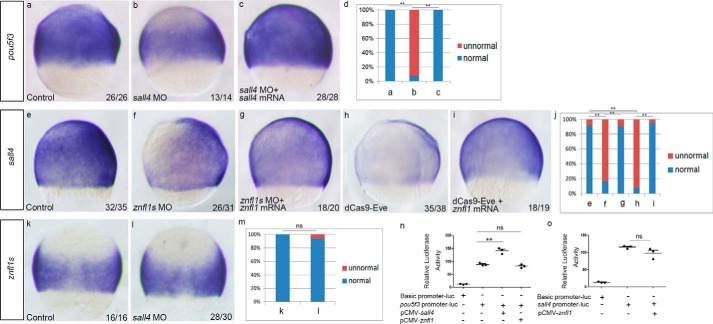

Zebrafish sall4 acts downstream of znfl1s and upstream of pou5f3 during its posterior neuroectoderm development

It has been demonstrated that zebrafish Sall4 can bind pou5f3 promoter to modulate the expression of pou5f3 directly (12). To investigate whether this direct regulation occurs in the formation of zebrafish posterior neuroectoderm, we first checked the expression of pou5f3 in sall4 morphants. The results revealed that the expressions of pou5f3 were significantly down-regulated in sall4 morphants at 75% epiboly (Fig. 6, a, b, and d), and the decreased expression of pou5f3 in sall4 morphants was effectively rescued by overexpressing sall4 (Fig. 6, a–d). The results are consistent with the previous report that Sall4 works upstream to activate pou5f3 expression in zebrafish embryos directly (12). To further support the conclusion, we performed bioinformatics analysis on the 3.0-kbp genomic sequence upstream of the translation start site of pou5f3 and found a presumptive Sall4-binding site with a core sequence of “ATTTGCAT” located between −558 and −551 of pou5f3 promoter. We then cloned the 3.0-kbp genomic fragment to perform a Dual-Luciferase reporter assay on the promoter's activity in response to Sall4. The results showed that the promoter's activity was significantly increased (p < 0.01) when sall4was overexpressed (Fig. 6n). However, the promoter had no response (p > 0.05) to the overexpression of znfl1 (Fig. 6n). The results support that pou5f3 is a direct target gene of sall4 but not znfl1s during the formation of zebrafish posterior neuroectoderm.

Figure 6.

Zebrafish znfl1s control pou5f3 expressions through sall4 in gastrula. Expressions of pou5f3 were examined in the embryos microinjected with the control MO (a), sall4 MO (b), and sall4 MO plus sall4 mRNA (c), respectively. Expressions of sall4 were examined in the embryos microinjected with the control MO (e), znfl1 MO (f), znfl1 MO plus znfl1 mRNA (g), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (h), and dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs and znfl1 mRNA (i), respectively. Expressions of znfl1s were examined in the embryos microinjected with the control MO (k) and sall4 MO (l), respectively. Embryos were positioned in lateral view (a–c and e–i) or dorsal view (k and l), and all were examined at 8 hpf. The statistical analyses of the data derived from a–c, e–i, and k and l are shown in diagrams d, j, and m, respectively. Scatter plots showing that no significant change of the firefly luciferase activity driven by the pou5f3 or sall4 promoter was found in the cells transfected with pCMV-znfl1 compared with control vehicle pGL3 vectors (n and o), but significant changes of the pou5f3 promoter activity were found in the cells transfected with pCMV-sall4 compared with control vehicle pGL3 vectors (n). Error bars represent S.D. **, p < 0.01; ns, no significance.

Now that Sall4 was shown to directly regulate the expression of pou5f3 that works downstream of znfl1s to pattern posterior neuroectoderm, we therefore explored whether sall4 works downstream of znfl1s during the formation of posterior neuroectoderm in zebrafish gastrula. To do this, we examined the expressions of sall4 in the znfl1 knockdown embryos. Results from whole-mount in situ hybridization showed that a dramatic decrease of sall4 expression occurred in the znfl1 morphants (Fig. 6, f and j) and the embryos in which the expressions of znfl1s were inhibited by dCas9-Eve (Fig. 6, h and j), and overexpression of znfl1 mRNA effectively rescued the decreased expression of sall4 in the embryos microinjected with the znfl1 MO (Fig. 6, e–g and j) or dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (Fig. 6, e and h–j). Furthermore, the expressions of znfl1s were not changed in sall4 morphants (Fig. 6, k–m).

To investigate whether sall4 is directly regulated by Znfl1s, we performed the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay on its promoter's activity in response to Znfl1. The results showed that the promoter of sall4 had no response (p > 0.05) to the overexpression of znfl1 (Fig. 6o), suggesting that sall4 is not a direct target gene of znfl1s. Taken together, the results demonstrate that sall4 works downstream of znfl1s to directly control the expression of pou5f3 in zebrafish gastrula.

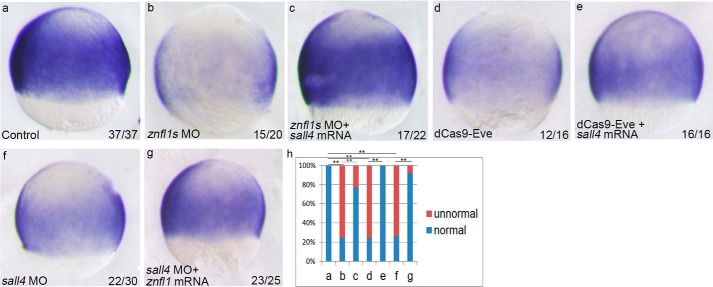

Next, we asked whether the loss of sall4 expression completely accounts for the decreased expression of pou5f3 caused by knocking down znfl1s in zebrafish embryos. To answer this, we examined the expression changes of pou5f3 in the znfl1 knockdown embryos in which sall4 was overexpressed. The results revealed that overexpression of sall4 effectively rescued pou5f3 expression in the znfl1 morphants (Fig. 7, a–c and h) and the embryos microinjected with dCas9-Eve (Fig. 7, a, d, e, and h). These data support the conclusion that znfl1s control pou5f3 expression by directly regulating sall4. However, the expression of pou5f3 was effectively rescued in sall4 morphants when znfl1 mRNA was overexpressed in the morphants (Fig. 7, a and f–h). The results suggest that zebrafish znfl1s play crucial roles in the formation of the posterior neuroectoderm by controlling the expression of pou5f3 through other factors besides sall4.

Figure 7.

Zebrafish znfl1s control pou5f3 expressions through other factors in addition to sall4 in gastrula. Expressions of pou5f3 were examined in the embryos microinjected with the control MO (a); znfl1 MO (b), znfl1 MO plus sall4 mRNA (c), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs (d), dCas9-Eve mRNA plus sgRNAs and sall4 mRNA (e), sall4 MO (f), and sall4 MO plus znfl1 mRNA (g), respectively. Embryos were positioned in lateral view, and all were examined at 8 hpf. The statistical analyses of the data derived from a–g are shown in diagram h. **, p < 0.01.

Discussion

Consistent with the fact that zebrafish genome underwent recent duplication, results from bioinformatics analysis reveal that it has 13 copies of znfl1, and all 13 paralogues of Znfl1 share highly identical cDNA sequences and protein sequences, although they are located in different chromosomes and have different genomic organization (Table 1 and Fig. 2, a and c). These features suggest that all the paralogues of Znfl1s should function redundantly during zebrafish early development. However, we found no gene homologues of znfl1s in other species by mining GenBankTM (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi). The results suggest that znfl1s might be unique genes existing in the zebrafish genome.

Consistent with the previous report that znfl1 is involved in the induction of the posterior nervous system in zebrafish (18), results from whole-mount in situ hybridization reveal that znfl1s are expressed in the posterior neuroectoderm of zebrafish gastrula. To uncover the roles of Znfl1s in the formation of posterior neuroectoderm, we developed the dCas9-Eve repression method to inhibit the transcriptions of all znfl1s as reported previously (22, 23) in addition to using the MO method to inhibit their translation. Performing the two kinds of knockdown experiments, we found that they both gave the same result: the 13 znfl1s function to pattern posterior neuroectoderm through regulating the expression of hoxb1b, the marker gene for the formation of posterior neuroectoderm (3), in zebrafish gastrula (Fig. 3).

Zebrafish pou5f3 encodes a POU-family transcription factor (24). It is expressed both maternally and zygotically. Maternal mutant embryos of pou5f3 develop into normal fertile adult fish, although cell movements during gastrulation are slightly delayed (25). In contrast, zygotic pou5f3 mutant embryos show neural plate patterning defects, displaying extended r2 and r4; narrowed r1, r3, and r5; and altered expression of egr2b (7). Moreover, maternal-zygotic pou5f3 mutants exhibit a more severe phenotype, failure of gastrulation to proceed normally (25). In this study, we found that pou5f3 acts downstream of znfl1s to determine the formation of posterior neuroectoderm by controlling the expression of hoxb1b (Fig. 5). Because znfl1s are zygotically expressed (Fig. 1), the reduced expression of pou5f3 in the znfl1 knockdown embryos should be due to the reduced expression of zygotic pou5f3. Consistent with this observation, the defective phenotype of posterior neuroectoderm and the reduced length of hindbrain (Fig. 4) in the znfl1 knockdown embryos are more similar to zygotic pou5f3 mutants (25). This at least partially explains why the phenotype of the znfl1 knockdown embryos was mimicked by microinjecting a low amount (0.1 ng) of pou5f3 MO.

Sall4 is a gene encoding a zinc finger transcription factor involved in the maintenance of embryonic stem cells (26). Although xSall4 was reported to represses xPou5f3 expression to provide a permissive environment allowing for additional Wnt/Fgf/RA signals to posteriorize the neural plate in Xenopus (11), the expression of Pou5f3 was regulated by transcription factor Sall4 through binding the core sequences of Sall4-binding sites that are present in the promoter of Pou5f3 both in mammalian embryonic stem cells and zebrafish embryos (12, 27). One explanation for the differences is that different molecules have come to assume distinct functions in different cell lineages (e.g. Snail-family proteins play different roles in zebrafish, Xenopus, and mouse) (28). Consistent with the directly regulated expression of pou5f3 by Sall4, we demonstrate in this study that knocking down sall4 results in the reduced expression of pou5f3, and the decreased expression of pou5f3 is effectively returned to normal by overexpressing sall4 in zebrafish sall4 morphants (Fig. 6, a–d). Moreover, results of the promoter activity assay of pou5f3 support that zebrafish pou5f3 is directly regulated by Sall4 during the formation of posterior neuroectoderm in zebrafish gastrula (Fig. 6n).

Although the znfl1 knockdown embryos display reduced expression of sall4 in the neuroectoderm (Fig. 6, e, f, and h) and overexpression of sall4 rescues the developmental defects of pou5f3 expression in the znfl1 knockdown embryos (Fig. 7, a–e and h), overexpression of znfl1s in sall4 knockdown embryos effectively rescues the expression of pou5f3 in neuroectoderm (Fig. 7, f–h). We therefore conclude that znfl1s regulate the expression of pou5f3 through other factor(s) in addition to sall4 (Fig. 7). This is consistent with the observation that the expression level of pou5f3 in the znfl1 morphants (Figs. 5b and 7b) is significantly lower than in sall4 morphants (Figs. 6b and 7f).

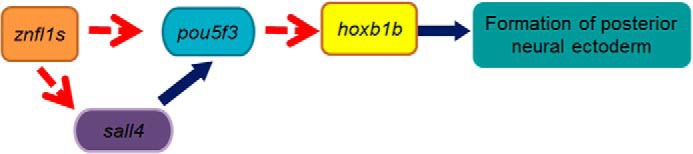

In summary, we demonstrate in this study that Znfl1s pattern posterior neuroectoderm through regulating hoxb1b expression by acting upstream of pou5f3 and sall4 (Fig. 8). It is well known that RA signaling ensures normal posterior neuroectoderm patterning through directly regulating hoxb1b expression (3, 29). In this study, our results provide a new finding that other transcription factors like Znfl1s, Sall4, and Pou5f3 are involved in regulating the formation of posterior neuroectoderm through controlling hoxb1b expression. Future work should be performed to explore whether znfl1s are the direct target genes that mediate the roles of RA signaling in patterning the posterior neuroectoderm of zebrafish gastrula.

Figure 8.

Working model proposed by this study. Blue arrows show direct regulation. Broken red arrows represent action upstream.

Experimental procedures

Zebrafish maintenance

Zebrafish were raised in the zebrafish facility of the Model Animal Research Center, Nanjing University, in accordance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee-approved protocol. The embryos were staged as described previously (30).

Bioinformatics analysis

All sequences were retrieved from Ensemble (http://asia.ensembl.org/index.html)4 or GenBank (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The ENSDARG identifiers and/or GenBank accession numbers to access the DNA and protein sequences of all znfl1s are ENSDARG00000037914, NM_194389 (znfl1); NP_001164503 (znfl1b); ENSDARG00000074359 (znfl1c); NM_001113633 (znfl1d); ENSDARG00000077719 (znfl1e); ENSDARG00000101498 (znfl1f); NM_001145701 (znfl1g); ENSDARG00000077877 (znfl1h); ENSDARG00000079126 (znfl1i), ENSDARG00000074668 (znfl1j); ENSDARG00000079036 (znfl1k); ENSDARG00000094197 (znfl1l); and ENSDARG00000074024 (znfl1m). The protein sequences or DNA sequences of the 13 Znfl1 paralogues were aligned using the software Vector NTI (Invitrogen). Promoter analysis was performed using online software (Genomatix).

Microinjection of morpholinos into zebrafish embryos

MOs were purchased from Gene Tools. The znfl1 MO (AATGGTAACACATGGAGGTTCTGTT) was designed to block the translations of the mRNAs of all znfl1s. Zebrafish pou5f3 and sall4 were knocked down using the MO as described previously (31, 32); the sequences are CGCTCTCTCCGTCATCTTTCCGCTA (pou5f3) (32) and CGCTCCAAACTCACCATTTTCTGTC (sall4) (31). The sequence of control MO is CCTCTTACCTCAGTTACAATTTATA (33).

MO was dissolved in Nanopure water and microinjected into the embryos at the one- to two-cell stage. The amount of MO microinjected into each embryo was ∼1 nl of solution containing 4 ng of the znfl1 MO, 0.1 ng of pou5f3 MO, 4 ng of sall4 MO, and an equal amount of control MO, respectively.

The specificity and efficiency of the znfl1 MO were determined by the in vitro Dual-Luciferase reporter assay (Promega). Briefly, a pair of oligos, AGCTTAACAGAACCTCCATGTGTTACCATTGACCAGC and CATGGCTGGTCAATGGTAACACATGGAGGTTCTGTTA, that contain the MO target sequence of znfl1s was first annealed and then recombined into pGL3-Basic vector (Promega) through HindIII and NcoI restriction endonuclease sites. The fused construct consisting of MO target sequence and the coding sequence of firefly luciferase was finally inserted into pBluescript SK (Stratagene) under the control of T7 promoter. The mRNA of the fused construct was then synthesized, capped, and tailed using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit (Ambion). 100 pg of synthesized mRNA plus 20 pg of Renilla luciferase expression vector (internal control) and 4 ng of the znfl1 MO or control MO were microinjected into each zebrafish embryo at the one- to two-cell stage. Three pools of 20 microinjected embryos at bud stage were collected to perform the Dual-Luciferase assay following the manufacturer's protocol as we described previously (21).

Construction of the expression vector dCas9-Eve

The full-length coding sequence of codon-humanized Cas9 with nuclear localization signal was synthesized by BGI (China) according to the published sequences in the literature (34). The coding sequences of dCas9 were therefore made by mutating the sequences of Cas9 following the description in the literature (23). The coding sequences of dCas9 were recombined into pBluescript KS under the control of T7 promoter (pKS-dCas9).

To make dCas9-Eve that works in the zebrafish system, we first amplified the coding sequence for the putative Eve repressor domain of zebrafish Evx1 (even-skipped homeobox 1) (NM_131249.2) using as template the cDNA derived from zebrafish embryos at 24 hpf with forward primer (TCTAGAACCATGgaaaccacaataaaggtttg) and reverse primer (CTCGAGGCTAGCGAGCTCtctagttagtggcacttcct). The PCR fragment was cloned into pGEM-T (pGEMT-Eve) and sequenced to confirm its identity. After digesting pGEMT-Eve and pCS2+ with XbaI and XhoI, we then cloned the coding sequence for zebrafish Eve into pCS2+, resulting in the expression plasmid named pCS2+Eve. We next fused the coding sequences of zebrafish Eve with the partial sequence encoding the C terminus of dCas9-Eve by performing overlapping PCR. We first amplified the partial sequence encoding the C terminus of dCas9-Eve using pKS-dCas9 as template with the primers dC9KS-F1 (GAAACCGGGGAGATCGTGTG) and dC9KS-R1 (gaacgcgtacctccGCTGGCCTCCACCTTTCTCTTC) and then amplified the sequence encoding the zebrafish Eve using pCS2+Eve as template with primers dC9CS-F2 (GTGGAGGCCAGCggaggtacgcgttctagaaccatg) and dC9CSdr-R2 (agatctctcgagTCAgctagcgagctcTCTAGTTAG). Overlapping PCR was then performed using as template the mixture of the two purified PCR fragments described above with primers dC9KS-F1 and dC9CSdr-R2. After digestion with SphI and XhoI, the overlapping PCR fragment was recombined into pKS-dCas9 to form the expression vector pKS-dCas9-Eve under the control of T7 promoter.

Design and synthesis of sgRNAs in vitro

Three sgRNAs were prepared to recognize the 5′-flanking sequence upstream of the start codons of znfl1s. The template sequences of the three CRISPRs (clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats) were GTTAGTAGCCAAATAAGATTTGG, ACAACATCAGAAAAACATGG, and GCACTGTCCTGTACTTCCCATGG (the underlined sequences represent protospacer adjacent motifs).

To synthesize sgRNA in vitro, templates of sgRNA were amplified by PCR with pYSY-gRNA vector (YSY, China) using the method reported previously (35). sgRNAs were synthesized using the MAXIscript In Vitro Transcription kit (Ambion).

In vitro synthesis of mRNA and microinjection of RNAs into zebrafish embryos

To synthesize mRNA in vitro, we first cloned the full-length coding sequences of znfl1, pou5f3, and sall4 by RT-PCR using the cDNAs derived from zebrafish embryos at 75% epiboly with primers ATGTTGGAGAATTTTAATGC (forward) and CTATTTTTGTTGTATTGTTA (reverse) for znfl1 (NM_194389), GAAGATCTTTACTATTCGCCCCTGAT (forward, the underlined sequences represent restriction site hereafter) and GGACTAGTGGTTTGGGAACAACTGGA (reverse) for sall4 (NM_001080609), and GAAGATCTATGACGGAGAGAGCGCAGAGC (forward) and GGACTAGTTTAGCTGGTGAGATGACCC (reverse) for pou5f3 (NM_131112). The PCR products were then subcloned into pXT-7 vector under T7 promoter direction as we reported previously (33). znfl1, pou5f3, sall4, and dCas9-Eve mRNAs were synthesized, capped, and tailed in vitro using the mMESSAGE mMACHINE T7 Ultra kit. The mRNAs of znfl1, pou5f3, and sall4 did not contain the corresponding MO target sequences. About 1 nl of 100 ng/μl znfl1 mRNA, 100 ng/μl sall4 mRNA, 20 ng/μl pou5f3 mRNA, and 100 ng/μl sgRNA plus 250 ng/μl dCas9-Eve mRNA was microinjected into a zebrafish embryo at the one-cell stage.

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations

Whole-mount in situ hybridizations were performed as we described previously (36). The templates for making the RNA probes to examine the expressions of hoxb1b (NM_131142), eng2a (NM_131044), egr2b (previously named krox20; NM_130997), hoxb4a (NM_131118), and otx2 (BC115165) were prepared as we described previously(33). The cDNA templates for making antisense RNA probes of znfl1 (NM_194389), pou5f3 (NM_131112), sall4 (NM_001080609), hoxb1a (NM_131115), and hoxd4a (NM_001126445) were RT-PCR-amplified fragments. The sequences of primers for cloning the probe templates were GACAATGAGGAGGGCTAT (forward) and AAACTGCTTGAACAGGTG (reverse) for znfl1, CTGAGTTCTCGCAGCGTTCT (forward) and TGGAAGTCGGCTGGCTAA (reverse) for sall4, CAGAGCCCAACAGCAGCAGA (forward) and GTGAGATGACCCACCAAACCAG (reverse) for pou5f3, TGGAACTGGGACAACAAG (forward) and AGACGAAGTGGAGGAAGC (reverse) for hoxb1a, and AGCTTCTTCTCGGTTGAT (forward) and GCTGTCCGAGAACGTTTG (reverse) for hoxd4a.

Promoter cloning, construction of eukaryotic expression vector, and in vitro Dual-Luciferase reporter assay

2,839 bp of sall4 promoter (NM_001080609) and 3,000 bp of pou5f3 promoter (NM_131112) were cloned by PCR with the primers ATTTTGGGCTGCTAAGTT and GGGTCGTCCGAATTGATAT (for sall4) and TGTTACTTTGTGCCCTGCTC and CTTTCCGCTAAAAAGGTTGT (for pou5f3) using the template genomic DNA prepared as we reported previously (37). All the PCR products were first subcloned into pGEM-T Easy vector (Promega). The amplified promoters were sequenced to confirm their identities and then recombined into pGL3-Basic luciferase reporter vector using the One Step Cloning kit (Vazyme, China) with primers CTATCGATAGGTACCGAGCTCATTTTGGGCTGCTAAGTTCTATCGATAGGTACCGAGCTCGGGAAAACTCAGTCACTTC (forward) and ACTTAGATCGCAGATCTCGAGGGGTCGTCCGAATTGATAT (reverse) for sall4 promoter and CTATCGATAGGTACCGAGCTCTGTTACTTTGTGCCCTGCTC (forward) and ACTTAGATCGCAGATCTCGAGCTTTCCGCTAAAAAGGTTGT (reverse) for pou5f3 promoter. The plasmids were named pGL3-sall4 and pGL3-pou5f3, respectively. The full-length coding sequences of znfl1 and sall4 were recombined into pCMV-3Tag-7 vector (Stratagene) to form the eukaryotic expression vectors pCMV-znfl1 and pCMV-sall4, respectively.

Dual-Luciferase reporter assays were performed on 293T cells as we reported previously (38) using the Dual-Luciferase reporter assay kit (Promega). About 100 ng/μl expression vectors pCMV-znfl1, pCMV-sall4, pGL3-sall4, and pGL3-pou5f3 and 2 ng/μl Renilla luciferase expression vector were used. The assays were performed in at least three independent experiments.

Measurement of forebrain and hindbrain length

The zebrafish embryos fixed by 4% paraformaldehyde were photographed in bright field under a dissecting microscope using digital cameras. The lengths of forebrain and hindbrain were measured in laterally viewed embryos at 24 or 20 hpf with Image-Pro Plus software. The length unit was arbitrary.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 software package (SPSS, Chicago, IL) with an independent-samples t test or χ2 test between two groups. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 or p < 0.01.

Author contributions

Q. Zhao contributed to the conception of the study. X. D., Jingyun L., L. H., C. G., W. J., Y. Y., Q. Zhang, and L. C performed the experiments. Q. Zhao, Jingyun L. and X. D. wrote the paper. Jun L. contributed to analysis with constructive discussions.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 31471355 and 31271569. The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest with the contents of this article.

Please note that the JBC is not responsible for the long-term archiving and maintenance of this site or any other third party-hosted site.

- RA

- retinoic acid

- Sall

- Spalt-like

- znfl1

- zinc finger-like gene 1

- MO

- morpholino

- sgRNA

- single-guide RNA

- r

- rhombomere

- hpf

- hours postfertilization.

References

- 1. Muñoz-Sanjuán I., and Brivanlou A. H. (2002) Neural induction, the default model and embryonic stem cells. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 3, 271–280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Stern C. D. (2006) Neural induction: 10 years on since the 'default model'. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 18, 692–697 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kudoh T., Wilson S. W., and Dawid I. B. (2002) Distinct roles for Fgf, Wnt and retinoic acid in posteriorizing the neural ectoderm. Development 129, 4335–4346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Weidinger G., Thorpe C. J., Wuennenberg-Stapleton K., Ngai J., and Moon R. T. (2005) The Sp1-related transcription factors sp5 and sp5-like act downstream of Wnt/β-catenin signaling in mesoderm and neuroectoderm patterning. Curr. Biol. 15, 489–500 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tallafuss A., Wilm T. P., Crozatier M., Pfeffer P., Wassef M., and Bally-Cuif L. (2001) The zebrafish buttonhead-like factor Bts1 is an early regulator of pax2.1 expression during mid-hindbrain development. Development 128, 4021–4034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cao Y., Knöchel S., Donow C., Miethe J., Kaufmann E., and Knöchel W. (2004) The POU factor Oct-25 regulates the Xvent-2B gene and counteracts terminal differentiation in Xenopus embryos. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43735–43743 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Hauptmann G., Belting H. G., Wolke U., Lunde K., Söll I., Abdelilah-Seyfried S., Prince V., and Driever W. (2002) spiel ohne grenzen/pou2 is required for zebrafish hindbrain segmentation. Development 129, 1645–1655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Parker H. J., Bronner M. E., and Krumlauf R. (2016) The vertebrate Hox gene regulatory network for hindbrain segmentation: evolution and diversification: coupling of a Hox gene regulatory network to hindbrain segmentation is an ancient trait originating at the base of vertebrates. BioEssays 38, 526–538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kam M. K., and Lui V. C. (2015) Roles of Hoxb5 in the development of vagal and trunk neural crest cells. Dev. Growth Differ. 57, 158–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Cruz C., Maegawa S., Weinberg E. S., Wilson S. W., Dawid I. B., and Kudoh T. (2010) Induction and patterning of trunk and tail neural ectoderm by the homeobox gene eve1 in zebrafish embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3564–3569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Young J. J., Kjolby R. A., Kong N. R., Monica S. D., and Harland R. M. (2014) Spalt-like 4 promotes posterior neural fates via repression of pou5f3 family members in Xenopus. Development 141, 1683–1693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paik E. J., Mahony S., White R. M., Price E. N., Dibiase A., Dorjsuren B., Mosimann C., Davidson A. J., Gifford D., and Zon L. I. (2013) A Cdx4-Sall4 regulatory module controls the transition from mesoderm formation to embryonic hematopoiesis. Stem Cell Rep. 1, 425–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Reim G., and Brand M. (2002) Spiel-ohne-grenzen/pou2 mediates regional competence to respond to Fgf8 during zebrafish early neural development. Development 129, 917–933 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Belting H. G., Hauptmann G., Meyer D., Abdelilah-Seyfried S., Chitnis A., Eschbach C., Söll I., Thisse C., Thisse B., Artinger K. B., Lunde K., and Driever W. (2001) spiel ohne grenzen/pou2 is required during establishment of the zebrafish midbrain-hindbrain boundary organizer. Development 128, 4165–4176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lippmann E. S., Williams C. E., Ruhl D. A., Estevez-Silva M. C., Chapman E. R., Coon J. J., and Ashton R. S. (2015) Deterministic HOX patterning in human pluripotent stem cell-derived neuroectoderm. Stem Cell Rep. 4, 632–644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Philippidou P., and Dasen J. S. (2013) Hox genes: choreographers in neural development, architects of circuit organization. Neuron 80, 12–34 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Zigman M., Laumann-Lipp N., Titus T., Postlethwait J., and Moens C. B. (2014) Hoxb1b controls oriented cell division, cell shape and microtubule dynamics in neural tube morphogenesis. Development 141, 639–649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Yoda H., Momoi A., Esguerra C. V., Meyer D., Driever W., Kondoh H., and Furutani-Seiki M. (2003) An expression pattern screen for genes involved in the induction of the posterior nervous system of zebrafish. Differentiation 71, 152–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. McClintock J. M., Kheirbek M. A., and Prince V. E. (2002) Knockdown of duplicated zebrafish hoxb1 genes reveals distinct roles in hindbrain patterning and a novel mechanism of duplicate gene retention. Development 129, 2339–2354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Maves L., and Kimmel C. B. (2005) Dynamic and sequential patterning of the zebrafish posterior hindbrain by retinoic acid. Dev. Biol. 285, 593–605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Xu F., Li K., Tian M., Hu P., Song W., Chen J., Gao X., and Zhao Q. (2009) N-CoR is required for patterning the anterior-posterior axis of zebrafish hindbrain by actively repressing retinoid signaling. Mech. Dev. 126, 771–780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Long L., Guo H., Yao D., Xiong K., Li Y., Liu P., Zhu Z., and Liu D. (2015) Regulation of transcriptionally active genes via the catalytically inactive Cas9 in C. elegans and D. rerio. Cell Res. 25, 638–641 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Gilbert L. A., Larson M. H., Morsut L., Liu Z., Brar G. A., Torres S. E., Stern-Ginossar N., Brandman O., Whitehead E. H., Doudna J. A., Lim W. A., Weissman J. S., and Qi L. S. (2013) CRISPR-mediated modular RNA-guided regulation of transcription in eukaryotes. Cell 154, 442–451 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Parvin M. S., Okuyama N., Inoue F., Islam M. E., Kawakami A., Takeda H., and Yamasu K. (2008) Autoregulatory loop and retinoic acid repression regulate pou2/pou5f1 gene expression in the zebrafish embryonic brain. Dev. Dyn. 237, 1373–1388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lunde K., Belting H. G., and Driever W. (2004) Zebrafish pou5f1/pou2, homolog of mammalian Oct4, functions in the endoderm specification cascade. Curr. Biol. 14, 48–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Robles V., Martí M., and Izpisua Belmonte J. C. (2011) Study of pluripotency markers in zebrafish embryos and transient embryonic stem cell cultures. Zebrafish 8, 57–63 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Zhang J., Tam W. L., Tong G. Q., Wu Q., Chan H. Y., Soh B. S., Lou Y., Yang J., Ma Y., Chai L., Ng H. H., Lufkin T., Robson P., and Lim B. (2006) Sall4 modulates embryonic stem cell pluripotency and early embryonic development by the transcriptional regulation of Pou5f1. Nat. Cell Biol. 8, 1114–1123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Klymkowsky M. W., Rossi C. C., and Artinger K. B. (2010) Mechanisms driving neural crest induction and migration in the zebrafish and Xenopus laevis. Cell Adh. Migr. 4, 595–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ishioka A., Jindo T., Kawanabe T., Hatta K., Parvin M. S., Nikaido M., Kuroyanagi Y., Takeda H., and Yamasu K. (2011) Retinoic acid-dependent establishment of positional information in the hindbrain was conserved during vertebrate evolution. Dev. Biol. 350, 154–168 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kimmel C. B., Ballard W. W., Kimmel S. R., Ullmann B., and Schilling T. F. (1995) Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev. Dyn. 203, 253–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Harvey S. A., and Logan M. P. (2006) sall4 acts downstream of tbx5 and is required for pectoral fin outgrowth. Development 133, 1165–1173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Burgess S., Reim G., Chen W., Hopkins N., and Brand M. (2002) The zebrafish spiel-ohne-grenzen (spg) gene encodes the POU domain protein Pou2 related to mammalian Oct4 and is essential for formation of the midbrain and hindbrain, and for pre-gastrula morphogenesis. Development 129, 905–916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Liang D., Jia W., Li J., Li K., and Zhao Q. (2012) Retinoic acid signaling plays a restrictive role in zebrafish primitive myelopoiesis. PLoS One 7, e30865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Cong L., Ran F. A., Cox D., Lin S., Barretto R., Habib N., Hsu P. D., Wu X., Jiang W., Marraffini L. A., and Zhang F. (2013) Multiplex genome engineering using CRISPR/Cas systems. Science 339, 819–823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chang N., Sun C., Gao L., Zhu D., Xu X., Zhu X., Xiong J. W., and Xi J. J. (2013) Genome editing with RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease in zebrafish embryos. Cell Res. 23, 465–472 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Li J., Li K., Dong X., Liang D., and Zhao Q. (2014) Ncor1 and Ncor2 play essential but distinct roles in zebrafish primitive myelopoiesis. Dev. Dyn. 243, 1544–1553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Xu S., Cao S., Zou B., Yue Y., Gu C., Chen X., Wang P., Dong X., Xiang Z., Li K., Zhu M., Zhao Q., and Zhou G. (2016) An alternative novel tool for DNA editing without target sequence limitation: the structure-guided nuclease. Genome Biol. 17, 186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Li J., Hu P., Li K., and Zhao Q. (2012) Identification and characterization of a novel retinoic acid response element in zebrafish cyp26a1 promoter. Anat. Rec. 295, 268–277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]