Abstract

Injury-induced sensitization of nociceptors contributes to pain states and the development of chronic pain. Inhibiting activity-dependent mRNA translation through mechanistic target of rapamycin and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways blocks the development of nociceptor sensitization. These pathways convergently signal to the eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4F complex to regulate the sensitization of nociceptors, but the details of this process are ill defined. Here we investigated the hypothesis that phosphorylation of the 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E by its specific kinase MAPK interacting kinases (MNKs) 1/2 is a key factor in nociceptor sensitization and the development of chronic pain. Phosphorylation of ser209 on eIF4E regulates the translation of a subset of mRNAs. We show that pronociceptive and inflammatory factors, such as nerve growth factor (NGF), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and carrageenan, produce decreased mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity, decreased affective pain behaviors, and strongly reduced hyperalgesic priming in mice lacking eIF4E phosphorylation (eIF4ES209A). Tests were done in both sexes, and no sex differences were found. Moreover, in patch-clamp electrophysiology and Ca2+ imaging experiments on dorsal root ganglion neurons, NGF- and IL-6-induced increases in excitability were attenuated in neurons from eIF4ES209A mice. These effects were recapitulated in Mnk1/2−/− mice and with the MNK1/2 inhibitor cercosporamide. We also find that cold hypersensitivity induced by peripheral nerve injury is reduced in eIF4ES209A and Mnk1/2−/− mice and following cercosporamide treatment. Our findings demonstrate that the MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling axis is an important contributing factor to mechanisms of nociceptor plasticity and the development of chronic pain.

SIGNIFICANCE STATEMENT Chronic pain is a debilitating disease affecting approximately one in three Americans. Chronic pain is thought to be driven by changes in the excitability of peripheral nociceptive neurons, but the precise mechanisms controlling these changes are not elucidated. Emerging evidence demonstrates that mRNA translation regulation pathways are key factors in changes in nociceptor excitability. Our work demonstrates that a single phosphorylation site on the 5′ cap-binding protein eIF4E is a critical mechanism for changes in nociceptor excitability that drive the development of chronic pain. We reveal a new mechanistic target for the development of a chronic pain state and propose that targeting the upstream kinase, MAPK interacting kinase 1/2, could be used as a therapeutic approach for chronic pain.

Keywords: chronic pain, dorsal root ganglion, eIF4E, MNK1, MNK2, nociceptor

Introduction

Translation of mRNAs is dynamically regulated in cells by upstream signaling factors that respond to a broad variety of receptors, including ion channels, G-protein-coupled receptors and tyrosine receptor kinases. For example, in dorsal root ganglion (DRG) neurons, nerve growth factor (NGF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6), two extracellular ligands intimately linked to pain across mammalian species, signal via their cognate receptors to the mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways to induce eukaryotic translation initiation factor (eIF) 4F complex formation and promote translation (Melemedjian et al., 2010). The eIF4F complex is composed of the 5′ cap binding protein eIF4E, the deadbox RNA helicase eIF4A, and the scaffolding protein eIF4G. Phosphorylation of 4E-binding proteins (4E-BPs) by mTOR relieves inhibition on eIF4E and allows for eIF4E association with eIF4G and eIF4A to form the eIF4F complex, which promotes cap-dependent translation (Sonenberg and Hinnebusch, 2009). On the other hand, MAPKs act via the MAPK interacting kinases (MNKs) 1/2 to phosphorylate eIF4E at Serine 209 (Pyronnet et al., 1999; Waskiewicz et al., 1999). While the precise role of eIF4E phosphorylation is not known, eIF4E phosphorylation has been linked to the development of cancer (Furic et al., 2010) and immunity (Herdy et al., 2012). Its physiological role in the context of sensory neuron plasticity and pathological pain is unexplored.

The diversity of the mechanisms of translation control by the eIF4F proteins is more complex than previously thought. It is now known that specific phosphorylation events on individual eIF4F complex proteins control the translation of distinct subsets of mRNAs. The mTOR pathway has recently been shown to primarily influence the translation of mRNAs that contain terminal oligopyrimidine tracts in their 5′ untranslated regions (UTRs; Thoreen et al., 2012). Similarly, the RNA helicase eIF4A primarily influences the translation of mRNAs with highly structured 5′ UTRs and/or 5′ UTRs that contain sequence motifs that form G-quadruplexes (Wolfe et al., 2014). In the context of pain, two recent studies have shown distinct phenotypes in 4E-BP1 knock-out mice or when eIF2α phosphorylation is genetically reduced. 4E-BP1 knock-out mice show increased spinal cord expression of neuroligin 1 and enhanced mechanical sensitivity with no change in thermal thresholds (Khoutorsky et al., 2015). On the other hand, mice lacking eIF2α phosphorylation on one allele have reduced responses to thermal stimulation and a deficit in thermal hypersensitivity after inflammation but normal mechanical pain (Khoutorsky et al., 2016). These studies highlight that distinct translation regulation signaling pathways produce diverse sensory phenotypes.

The goal of this study was to test the hypothesis that eIF4E phosphorylation is a central regulator of nociceptive plasticity and participates in the development of a chronic pain state. We tested this hypothesis using mice lacking the phosphorylation site for MNK1/2 on eIF4E (eIF4ES209A), mice lacking both Mnk1 and 2 (Mnk−/−; Ueda et al., 2004), and an inhibitor of MNK1/2 kinase activity, cercosporamide (Altman et al., 2013). We find that, different from 4E-BP1 knockouts or eIF2α mutants (Khoutorsky et al., 2015, 2016), eIF4E phosphorylation does not influence acute pain behavior but does promote nociceptor sensitization by a variety of endogenous factors known to promote pain in humans (NGF and IL-6) as well as exogenous pain-sensitizing factors. Moreover, eIF4E phosphorylation is an important contributor to the development of a chronic pain state, as shown in hyperalgesic priming, where mechanical hypersensitivity and grimacing are decreased. Finally, we show that MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling is involved in the generation of cold hypersensitivity in a nerve injury-induced neuropathic pain model. Our findings elucidate a new pathway regulating plasticity in the nociceptive system with implications for understanding signaling mechanisms in nociceptors that promote the development of a chronic pain state.

Materials and Methods

Experimental animals.

Male and female eIF4ES209A mice on a C57BL/6 background were generated in the Sonenberg laboratory at McGill University, as described previously (Furic et al., 2010), and bred at The University of Arizona or The University of Texas at Dallas to generate experimental animals. Mnk1/2−/− mice on a C57BL/6 background were obtained from Rikiro Fukunaga (Osaka University of Pharmaceutical Sciences in Japan, Osaka, Japan) (Ueda et al., 2004) and bred at McGill University. All animals were genotyped using DNA from ear clips taken at the time of weaning, and all animals were backcrossed to C57BL/6 background for at least 10 generations before experiments. All electrophysiological experiments using eIF4ES209A and WT mice were performed using mice between the ages of 4 and 6 weeks at the start of the experiment. Behavioral experiments using eIF4ES209A and WT mice were performed using mice between the ages of 8 and 12 weeks, weighing ∼20–25 g. Experiments using ICR mice obtained from Harlan Laboratories were performed using mice between 4 and 8 weeks of age, weighing ∼20–25 g at the start of the experiment. All animal procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committees at The University of Arizona, The University of Texas at Dallas, or McGill University and were performed in accordance with the guidelines of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Antibodies and chemicals.

The peripherin and neurofilament 200 (NF200) antibodies used for immunohistochemistry (IHC) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich. Isolectin B4 (IB4) conjugated to Alexa Fluor 568 and secondary Alexa Fluor antibodies were from Life Technologies. Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) antibody was purchased from Peninsula Laboratories International. Transient receptor potential V1 (TRPV1) antibody was procured from Neuromics. The phosphorylated (p) and total eIF4E, 4EBP1, extracellular signal-related protein kinase (ERK), and GAPDH antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology. The p-eIF4E antibody used for IHC was purchased from Abcam. (RS)-3,5-Dihyroxyphenylglycin (DHPG) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience. Cercosporamide was provided as a gift by Eli Lilly and Company to the Sonenberg laboratory. Mouse NGF was obtained from Millipore. Recombinant human or mouse IL-6 was purchased from R&D Systems. 2-Aminothiazol-4-yl-LIGRL-NH2 (2at-LIGRL) was synthesized in our laboratory as described previously (Boitano et al., 2011). Prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) was purchased from Cayman Chemicals. β-Cyclodextrin (45% weight/volume in H2O) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All other chemicals were attained from Thermo Fisher Scientific. See Table 1 for additional details on antibodies and chemicals used in this study.

Table 1.

List of antibodies used in this study

| Primary antibodies | Catalog number | Incubation | Secondary antibodies |

|---|---|---|---|

| eIF4E | Phospho-9741S | p, 1:500; p(IHC), 1:1000; t, 1:1000; overnight at 4°C | Goat anti-rabbit (Western blot, 1:10,000; IHC, 1:1000); 1 h at RT |

| Phospho (IHC)-ab76256 | |||

| Total-9742S | |||

| 4E-BP1 | Phospho-9459S | p, 1:500; t, 1:1000; overnight at 4°C | Goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000); 1 h at RT |

| Total-9452S | |||

| ERK | Phospho-9101S | p, 1:3000; t, 1:3000; overnight at 4°C | Goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000); 1 h at RT |

| Total-9102S | |||

| GAPDH | 2118 | 1:10,000; overnight at 4°C | Goat anti-rabbit (1:10,000); 1 h at RT |

| Peripherin | SAB 4502419 | 1:500; overnight at 4°C | Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 488 (1:1000); 1 h at RT |

| Neurofilament 200 | N0142 | 1:400; overnight at 4°C | Alexa Fluor goat anti-mouse 568 (1:1000); 1 h at RT |

| IB4−568 | I21412 | Spinal cord, 1:1000; DRG, 1:400; overnight at 4°C | None |

| CGRP | T-4032 | Spinal cord and DRG, 1:1000; overnight at 4°C | Alexa Fluor goat anti-rabbit 647 (1:2000); 1 h at RT |

| TRPV1 | GP14100 | Spinal cord and DRG, 1:1000; skin, 1:3000; overnight at 4°C | Alexa Fluor goat anti-guinea pig 488 (1:2000); 1 h at RT |

RT, Room temperature; t, total.

Behavior.

Mice were housed on 12 h light-/dark cycles with lights on at 7:00 A.M. Mice had food and water available ad libitum. All behavioral experiments were performed between the hours of 9:00 A.M. and 4:00 P.M. Mice were randomized to groups from multiple cages to avoid using mice from experimental groups that were cohabitating. Sample size was estimated by performing a power calculation using G*Power (version 3.1.9.2). With 80% power and an expectation of d = 2.2 effect size in behavioral experiments, and α set to 0.05, the sample size required was calculated as n = 5 per group. We therefore sought to have an n = 6 sample in all behavioral experiments. SD (set at 0.3) for the power calculation was based on previously published mechanical threshold data. The actual number of animals used in each experiment was based on available animals of the appropriate sex and weight but was at least n = 5 for behavior experiments, with the exception of testing the effects cercosporamide on cold hypersensitivity after spared nerve injury (SNI) where the sample size was determined by the amount of available drug and the dosing schedule given the findings in previous publications (Table 2). Mice were habituated for 1 h to clear acrylic behavioral chambers before beginning the experiment. Mechanical paw withdrawal thresholds were measured using the up-down method (Chaplan et al., 1994) with calibrated von Frey filaments (Stoelting Company). Thermal latency was measured using a Hargreaves device (IITC Life Science; Hargreaves et al., 1988) with heated glass. Settings of 29°C glass, 20% active laser power, and 20 s cutoff were used. Facial grimacing was evaluated using the Mouse Grimace Scale (MGS) as described previously (Langford et al., 2010). Nocifensive behavior in the formalin test was defined as licking, biting, or shaking of the affected paw, and was recorded over an observation period of 45 min. For intraplantar injections, 50 ng of NGF, 0.1 ng of IL-6, and 10 or 20 ng of 2at-LIGRL were diluted in 0.9% saline and injected with a volume of 25 μl via a 30.5-gauge needle. For intrathecal injections, 50 nmol DHPG was injected in a volume of 5 μl via a 30.5-gauge needle (Hylden and Wilcox, 1980). Cercosporamide for local injection was made up in 10% DMSO and 45% β-cyclodextrin in water and injected into the paw 15 min prior NGF, and simultaneously with 2at-LIGRL. Mice of both sexes were used in most experiments, and no significant differences between sexes were noted for drug or genotype in any experiments. The sexes of the mice used in all behavioral experiments is shown in Table 2. The experimenter was blinded to the genotype of the mice and the drug condition in all experiments. Behavioral experiments were performed by J.K.M., A.K., M.N.A., P.B.-I., and S.M.

Table 2.

Sex of animals by genotype in behavioral experiments in this study

| Test | WT males | WT females | eIF4ES209A males | eIF4ES209A females |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tail flick/von Frey | 4 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| Formalin | 6 | 4 | 7 | 5 |

| DHPG | 5 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| IL-6 | 5 | 3 | 6 | 4 |

| NGF | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 |

| NGF thermal | 6 | 6 | ||

| 2at-LIGRL (PAR2) | 4 | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Grimace [2at-LIGRL (PAR2)] | 4 | 1 | 6 | |

| Carrageenan | 5 | 6 | ||

| Carrageenan thermal | 5 | 5 | ||

| CFA (MNK−/−) | 4 | 5 | 4 (MNK−/−) | 5 (MNK−/−) |

| Cercosporamide plus NGF (in eIF4ES209A mice) | 4 | 7 | ||

| SNI | 4 | 4 | 6 | 2 |

| SNI (in MNK−/− mice) | 10 | 10 (MNK−/−) | ||

| Cercosporamide (SNI) | 4 | 4 |

Immunohistochemistry.

Animals were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by decapitation, and tissues were flash frozen in O.C.T. on dry ice. Spinal cords were pressure ejected using chilled 1× PBS. Sections of spinal cord (25 μm), DRGs (20 μm), and glaborous skin (25 μm) were mounted onto SuperFrost Plus slides (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and fixed in ice-cold 10% or 4% (skin) formalin in 1× PBS for 1 or 4 h (skin) then subsequently washed three times for 5 min each in 1× PBS. Slides were then transferred to a solution for permeabilization made of 1× PBS with 0.2% Triton X-100 (Sigma-Aldrich). After 30 min, slides were washed three times for 5 min each in 1× PBS. Tissues were blocked for at least 2 h in 1× PBS and 10% heat-inactivated normal goat serum. Antibodies for CGRP, IB4, and TRPV1 were applied together and incubated with spinal cord and DRG sections on slides at 4°C overnight. A combination of TRPV1 and p-eIF4E antibodies were applied to glabrous skin sections and incubated at 4°C overnight. DRG slices were also stained with peripherin and NF200. Immunoreactivity was visualized following 1 h incubation with goat anti-rabbit, goat anti-mouse, and goat anti-guinea pig Alexa Fluor antibodies at room temperature. All IHC images are representations of samples taken from three animals per genotype except for glaborous skin IHC where two animals per genotype were used. Images were taken using an Olympus FluoView 1200 confocal microscope. Analysis of images was done using ImageJ Version 1.48 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) for Mac OS X (Apple).

Western blotting.

Male mice were used for all Western blotting experiments and were killed by decapitation following anesthesia, and tissues were flash frozen on dry ice. Frozen tissues were homogenized in lysis buffer (50 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm EDTA, pH 8.0, and 1% Triton X-100) containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich), and homogenized using a pestle. Cultured primary DRG neurons were used to test the effects of cercosporamide on eIF4E phosphorylation and other pathways. For these experiments, mice (∼20 g) were anesthetized with isoflurane and killed by decapitation. DRGs were dissected and placed in chilled HBSS (Invitrogen) until processed. DRGs were then digested in 1 mg/ml collagenase A (Roche) for 25 min at 37°C then subsequently digested in a 1:1 mixture of 1 mg/ml collagenase D and papain (Roche) for 20 min at 37°C. DRGs were then triturated in a 1:1 mixture of 1 mg/ml trypsin inhibitor (Roche) and bovine serum albumin (BioPharm Laboratories), then filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer (Corning). Cells were pelleted then resuspended in DMEM/F12 with GlutaMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Thermo Fisher Scientific), 1% penicillin and streptomycin, and 3 μg/ml 5-fluorouridine with 7 μg/ml uridine to inhibit mitosis of non-neuronal cells and were distributed evenly in a six-well plate coated with poly-d-lysine (Becton Dickinson). DRG neurons were maintained in a 37°C incubator containing 5% CO2 with a media change every other day. On day 5, DRG neurons were treated as indicated in the Results section, and cells were rinsed with chilled 1× PBS, harvested in lysis buffer containing protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich), and then sonicated for 10 s. To clear debris, samples were centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. Ten to 15 μg of protein was loaded into each well and separated by a 10% SDS-PAGE gel. Proteins were transferred to a 0.45 PVDF membrane (Millipore) at 30 V overnight at 4°C. Subsequently, membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk in 1× Tris buffer solution containing Tween 20 (TTBS) for 3 h. Membranes were washed in 1× TTBS three times for 5 min each then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. The following day, membranes were washed three times in 1× TTBS for 5 min each then incubated with the corresponding secondary antibody at room temperature for 30 min to 1 h. Membranes were then washed with 1× TTBS six times for 5 min each. Signals were detected using Immobilon Western Chemiluminescent HRP Substrate (Millipore). Bands were visualized using film (Kodak) or with a Bio-Rad ChemiDoc Touch. Overexposed or saturated pixels detected by the ChemiDoc Touch were not used in the analysis. Membranes were stripped using Restore Western Blot Stripping buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and reprobed with another antibody. Analysis was performed using ImageJ version 1.48.

Ca2+ imaging.

WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons were dissociated and cultured as described above with the exception that cells were plated on glass-bottom poly-d-lysine-coated dishes (MatTek). DRG neurons were maintained in a 37°C incubator containing 5% CO2 with no media changes.

Ca2+ imaging experiments began 48 h after dissociation. Each dish was loaded with 10 μg/ml fura-2 AM (Life Technologies) along with IL-6 (50 ng/ml) or vehicle in HBSS (Invitrogen) supplemented with 0.25% w/v bovine serum albumin and 2 mm CaCl2 for 1 h at 37°C. The cells were then changed to a bath solution (125 mm NaCl, 5 mm KCl, 10 mm HEPES, 1 m CaCl2, 1 m MgCl2, and 2 m glucose, pH 7.4, adjusted with N-methyl glucamine to an osmolarity of ∼300 mOsm) for 30 min in a volume of 2 ml for esterification. Dishes were then washed with 2 ml of bath solution before recordings. Only neurons were used in the analysis, and these were defined as cells with a ≥10% ratiometric change in intracellular Ca2+ in response to the 50 mm KCl perfusion. Maximum Ca2+ release was calculated by comparing the ratio value change by time compared with baseline. A change of at least 10% intracellular Ca2+ in response to 1 nm PGE2 or 250 nm capsaicin was used to classify a neuron as being responsive to the stimulus. Experiments were conducted using the MetaFluor Fluorescence Ratio Imaging Software on an Olympus TH4–100 apparatus.

Extracellular electrophysiology.

Microelectrode array (MEA)-based extracellular recording experiments were performed on dissociated mouse DRG neurons between days in vitro 11 and 15 using Ti or ITO 60-channel planar microelectrode arrays (Multichannel Systems) equipped with hardware/software from Plexon Data were acquired at 40 kHz/channel and digitally filtered (0.1–7000 Hz bandpass) during acquisition. An additional four-pole Butterworth bandpass filter (250–7500 Hz) was applied to raw, continuous data, enabling the detection of single-event extracellular voltage changes (spikes). Spikes were defined by filtered data crossing a 5σ threshold based on root mean square values calculated for each channel. Active channels were defined by template spike detection, resulting in average waveform amplitudes of ≥40 μV during any of the three 1 h experimental intervals: baseline, IL-6 treatment, and wash. Between each interval, recording was paused for ∼2 min to allow for the manual exchange of culture medium for medium plus IL-6 (IL-6 treatment, 50 ng/ml) or fresh culture medium (Wash). Active channel data were exported to NeuroExplorer (Nex Technologies) for mean spike rate calculations and further analysis. Statistical comparisons of channel activity were performed using OriginPro software (OriginLab). MEA cultures were maintained at 37°C, 5% CO2, and 90% humidity throughout all experiments (Okolab). Culture–surface preparation, DRG extraction, dissociation, and cell seeding was performed as described above.

Patch-clamp electrophysiology.

For culturing DRGs, acutely dissected DRGs were incubated for 15 min in 20 U/ml papain (Worthington) followed by 15 min in 3 mg/ml collagenase type II (Worthington). After trituration through a fire-polished Pasteur pipette, dissociated cells were resuspended in Liebovitz L-15 medium (Life Technologies) supplemented with 10% FBS, 10 mm glucose, 10 mm HEPES, and 50 U/ml penicillin/streptomycin and plated on poly-d-lysine and laminin (Sigma-Aldrich)-coated dishes. Cells were allowed to adhere for several hours at room temperature in a humidified chamber and were covered with the media described above. DRG neurons were treated with 50 ng/ml NGF 18–24 h before recordings or with 50 ng/ml mouse IL-6 for 1 h.

Whole-cell patch-clamp experiments were performed on isolated mouse DRG neurons within 24 h of dissociation using a MultiClamp 700B (Molecular Devices) patch-clamp amplifier and PClamp 9 acquisition software (Molecular Devices). Recordings were sampled at 2 kHz and filtered at 1 kHz (Digidata 1322A, Molecular Devices). Pipettes (outer diameter, 1.5 mm; inner diameter, 0.86 mm) were pulled using a P-97 puller (Sutter Instrument) and heat polished to 1.5–4 MΩ resistance using a microforge (MF-83, Narishige). Series resistance was typically <7 MΩ and was compensated 60–80%. Data were analyzed using Clampfit 10 (Molecular Devices) and Origin 8 (OriginLab). All neurons included in the analysis had a resting membrane potential (RMP) −60 mV or lower. The RMP was recorded 1–3 min after achieving whole-cell configuration. In current-clamp mode, action potentials were elicited by injecting slow ramp currents from 0.1 to 0.7 nA with Δ = 0.2 nA over 1 s to mimic slow depolarization. The pipette solution contained the following (in mm): 140 KCl, 11 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 10 NaCl, 10 HEPES, and 1 CaCl2 pH 7.3 (adjusted with N-methyl glucamine), and osmolarity was ∼320 mOsm. The external solution contained the following (in mm): 135 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 5 KCl, 10 glucose, and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 (adjusted with N-methyl glucamine), and osmolarity was ∼320 mOsm. For neuronal voltage-gated sodium channel (VGNaC) current recordings, the pipette solution contained the following (in mm): 120 CsCl, 10 EGTA, 2 MgCl2, 5 NaCl, 10 HEPES, and 2 CaCl2, pH 7.3 (adjusted with N-methyl glucamine), and osmolarity was 320 mOsm. The external solution contained the following (in mm): 95 choline, 20 tetraethyl ammonium (TEA), 20 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 5 KCl, 0.1 CdCl2, and 0.1 NiCl2, pH 7.3 (adjusted with N-methyl glucamine), and osmolarity was 320 mOsm. In whole-cell configuration, cells were voltage clamped and VGNaC currents were evoked by a 50 ms depolarizing steps (from −80 to +40 mV in 5 mV increments) from a holding potential of −120 mV. Sodium currents were normalized to whole-cell capacitance and expressed as current density (pA/pF).

Statistics.

All data are represented as the mean ± SEM. Individual data points are represented in each graph to show the n in each group and the overall distribution of individual data points. All analyses was performed using GraphPad Prism 6 version 6.0 for Mac OS X (GraphPad Software). Single comparisons were performed using Student's t test, and multiple comparisons were performed using a one-way or two-way ANOVA with Bonferroni's post hoc tests for across-group comparisons or uncorrected Fisher's least significant difference test for within-group comparisons. Raw data from all experiments, including all of the statistical analysis, is available in prism file format on our website (http://www.utdallas.edu/bbs/painneurosciencelab/index.html).

Results

Nociceptive reflexes, acute pain behavior, and development of DRG–spinal dorsal horn connectivity is normal in eIF4ES209A mice

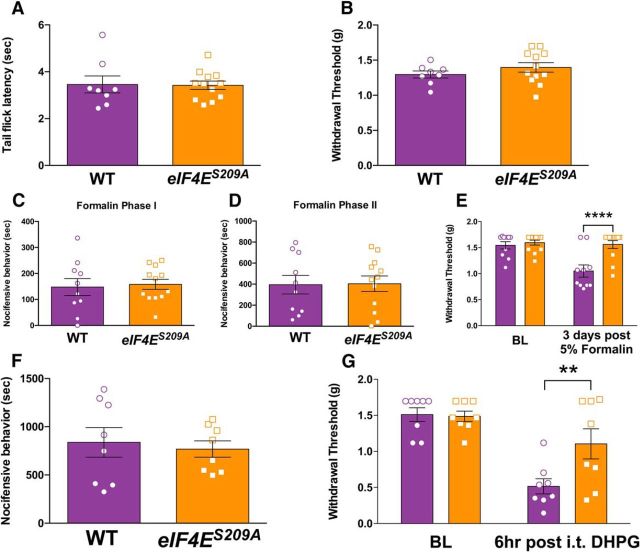

To test the hypothesis that eIF4E phosphorylation is a key factor in pain sensitization and the development of a chronic pain state, we used mice harboring a point mutation on the only known phosphorylation site in the eIF4E protein, S209 (Furic et al., 2010; Herdy et al., 2012; Gkogkas et al., 2014). We compared baseline thermal (Fig. 1A; t = 0.099, df = 18, p = 0.92) and mechanical thresholds (Fig. 1B; t = 1.1, df = 18, p = 0.29) between eIF4ES209A mice and their wild-type (WT) littermates and noted no differences in tail flick latencies to 55°C water or von Frey stimulation. When 5% formalin, a commonly used noxious irritant, was injected into the hindpaw, no differences in pain behaviors were noted between genotypes in either the first (Fig. 1C; 0–10 min; t = 0.29, df = 20, p = 0.78) or second (Fig. 1D; 15–45 min; t = 0.083, df = 20, p = 0.93) phases of the test. However, when mechanical sensitivity was examined 3 d after formalin administration, there was a striking difference between genotypes, with eIF4ES209A mice failing to develop mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 1E; F(1,40) = 12.56, p = 0.0010). The group I metabotropic glutamate receptor (mGluR) agonist DHPG promotes tonic pain-related behaviors when injected intrathecally (Karim et al., 2001). These behaviors are decreased by the inhibition of spinal mTOR signaling (Price et al., 2007). We did not detect any difference between genotypes in acute pain behaviors upon intrathecal injection of DHPG (Fig. 1F; t = 0.40, df = 14, p = 0.70), but 6 h following injection eIF4ES209A mice again showed a reduction in the magnitude of mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 1G; F(1,28) = 4.629, p = 0.040).

Figure 1.

eIF4ES209A mice have normal acute nociceptive responses but decreased mechanical hypersensitivity to formalin and a group I mGluR agonist. A, B, eIF4ES209A and WT mice show no differences in tail-flick responses (55°C; n ≥ 6; A) or baseline (BL) paw withdrawal thresholds (n ≥ 6; B). C, D, First phase (0–10 min) and second phase (15–45 min) summed responses were not different between eIF4ES209A and WT mice (n ≥ 10). E, Three days after intraplantar injection of 5% formalin, eIF4ES209A mice exhibited a significantly higher mechanical withdrawal threshold compared with WT mice (n ≥ 10). F, G, The mGlu1/5 receptor agonist DHPG (50 nmol) was injected intrathecally in both WT and eIF4ES209A mice. Nocifensive behaviors summed during the 30 min after injection were equal in both strains (n = 8). However, 6 h after DHPG intrathecal injection, WT mice exhibited mechanical hypersensitivity, whereas eIF4ES209A mice did not (n = 8). **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001.

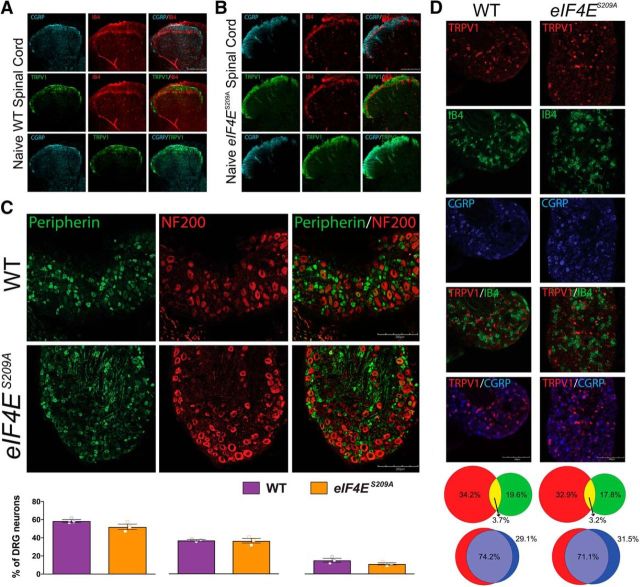

We next used a variety of histochemical markers to assess the possibility of developmental differences in sensory anatomy between eIF4ES209A mice and WT littermates. In both WT mice (Fig. 2A) and eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 2B), there was a clear delineation between the projections of CGRP-positive afferents and the IB4 population to lamina II of the dorsal horn. This was also true for TRPV1-positive and IB4-positive staining, while CGRP and TRPV1 afferents overlapped heavily in projections to lamina I and lamina II. Peripherin is expressed predominately in unmyelinated neurons in the DRG, whereas NF200 staining is used to label myelinated, large-diameter afferents that are mostly Aβ fibers. These two populations were nonoverlapping in both genotypes (Fig. 2C), and the proportions of DRG neurons expressing these markers were equivalent (Fig. 2C). Neuronal populations expressing TRPV1, IB4, and CGRP were also no different in eIF4ES209A versus WT DRGs (Fig. 2D).

Figure 2.

Normal development of nociceptive pathways in eIF4ES209A mouse DRGs and spinal cord. A, B, WT and eIF4ES209A mouse spinal cords were immunostained with CGRP (cyan), TRPV1 (green), and IB4 (red; representative images from n = 3 mice). C, Immunostaining for peripherin (green) and NF200 (red) in DRGs from WT and eIF4ES209A mice shows no differences in the proportion of peripherin-positive neurons per section (n = 3), the proportion of NF200-positive neurons per section (n = 3) or in overlap between the two markers (n = 3). D, WT and eIF4ES209A DRGs were stained for TRPV1 (red), IB4 (green), and CGRP (blue), and the proportion of neurons expressing each marker was assessed (TRPV1: WT mean = 34.3 ± 3.1% vs eIF4ES209A mean = 32.9 ± 1.3%; IB4: WT mean = 19.6 ± 1.8% vs eIF4ES209A mean = 17.8 ± 2.0%; WT mean = CGRP: 29.1 ± 1.5% vs eIF4ES209A mean = 31.5 ± 2.0%). TRPV1 and IB4 populations were segregated in both mouse strains (TRPV1/IB4 overlap: WT mean = 3.7 ± 0.1% vs eIF4ES209A mean = 3.2 ± 0.7%), while TRPV1 and CGRP overlapped substantially (TRPV1/CGRP overlap: WT mean = 74.2 ± 6.3% vs eIF4ES209A mean = 71.1 ± 2.3%) as demonstrated in the proportional Venn diagrams. Scale bars, 200 μm.

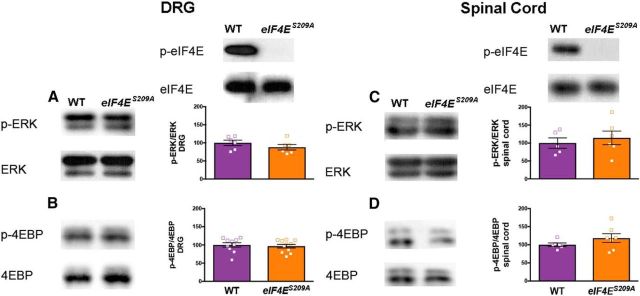

We were concerned about the possibility of feedback signaling that might change activity in upstream signaling pathways (Carracedo et al., 2008; Melemedjian et al., 2013) and complicate the interpretation of experimental results. We dissected lumbar DRGs and dorsal horn of the spinal cord from WT and eIF4ES209A mice and examined eIF4E, ERK, and 4E-BP phosphorylation in both tissues by Western blot. While eIF4E phosphorylation was completely absent in eIF4ES209A mice, there was no change in either ERK (Fig. 3A; t = 1.4, df = 10, p = 0.28) or 4E-BP (Fig. 3B; t = 0.43, df = 19, p = 0.67) phosphorylation in DRGs or spinal cord [Fig. 3C (t = 0.58, df = 19, p = 0.57), D (t = 1.3, df = 11, = 0.22)] in eIF4ES209A mice. These results rule out the possibility of feedback signaling in the ERK and mTOR pathways in tissues relevant to algesiometric assays.

Figure 3.

Normal ERK and 4E-BP phosphorylation in eIF4ES209A mouse DRGs and spinal cord. A, B, eIF4ES209A DRG shows equal levels of ERK and 4E-BP phosphorylation, while eIF4E phosphorylation is completely absent compared with WT DRG using Western blot analysis (n ≥ 6). C, D, Additionally, spinal cord from eIF4ES209A shows similar levels of p-ERK and p-4E-BP compared with WT spinal cord (n ≥ 5).

Deficits in mechanical sensitization, affective pain expression, and the development of hyperalgesic priming in eIF4ES209A mice

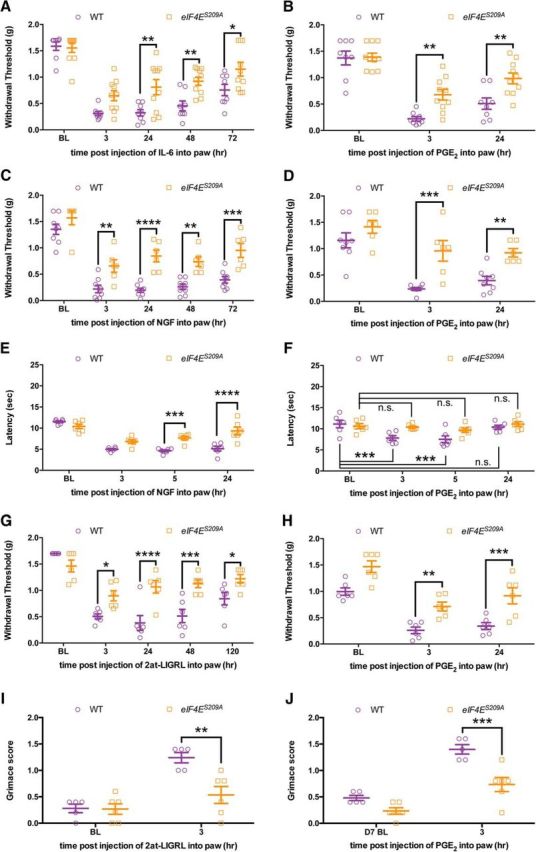

Previous studies have shown that IL-6, NGF (Melemedjian et al., 2010), and activation of protease-activated receptor 2 (PAR2; Tillu et al., 2015) promote mechanical hypersensitivity in an ERK-dependent fashion that requires de novo local protein synthesis. To test the role of eIF4E phosphorylation in this process, we injected IL-6, NGF, and the PAR2 agonist 2at-LIGRL (Flynn et al., 2011) into the hindpaw of WT and eIF4ES209A mice. IL-6 (0.1 ng) injected into the paw evoked mechanical hypersensitivity lasting ∼72 h (Fig. 4A; F(1,80) = 27.21, p < 0.0001) in WT mice. The magnitude of mechanical hypersensitivity was significantly reduced in eIF4ES209A mice 24, 48, and 72 h after injection (Fig. 4A). We, and others, have previously shown that activity-dependent translation regulation pathways are required for the full expression of hyperalgesic priming (Melemedjian et al., 2010, 2014; Asiedu et al., 2011; Bogen et al., 2012; Ferrari et al., 2015a,b), but the role of eIF4E phosphorylation in this development of a chronic pain state has not been addressed. We “primed” WT and eIF4ES209A mice with IL-6 (Fig. 4A) and, after their mechanical thresholds had completely returned to baseline, challenged these mice with a dose of PGE2 (100 ng) that fails to induce mechanical hypersensitivity in “unprimed” mice. We observed that the response to PGE2 injection in eIF4ES209A mice was blunted compared with that in WT mice (Fig. 4B; F(1,48) = 15.71, p = 0.0002).

Figure 4.

Mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity, facial grimacing, and the development of hyperalgesic priming are decreased in eIF4ES209A mice. A, IL-6 (0.1 ng) was injected into the hindpaw in both WT and eIF4ES209A mice. Hindpaw mechanical thresholds were measured at 3, 24, 48, and 72 h. B, eIF4ES209A mice exhibited reduced mechanical hypersensitivity compared with WT mice, and a deficit in hyperalgesic priming (n ≥ 6). C–F, eIF4ES209A mice also demonstrated decreased mechanical (C) and thermal (D; n = 6) hypersensitivity in response to intraplantar injection of 50 ng of NGF (n ≥ 6) and NGF-induced hyperalgesic priming (E, F). G, Intraperitoneal injection of 20 ng of 2at-LIGRL likewise induced decreased mechanical hypersensitivity in eIF4ES209A mice and a decrease of hyperalgesic priming in response to IL-6 (H; n ≥ 6). I, J, 2at-LIGRL induces facial grimacing in WT mice but not in eIF4ES209A mice (I); moreover, eIF4ES209A mice fail to show facial grimacing after 2at-LIGRL priming when subsequently challenged with PGE2 (n ≥ 6; J). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. BL, Baseline.

Similar experiments were performed using a hindpaw injection of NGF (50 ng). NGF evoked robust mechanical hypersensitivity in WT mice, whereas in eIF4ES209A mice it was dramatically reduced (Fig. 4C; F(1,60) = 67.01, p < 0.0001). After the mice returned to baseline mechanical thresholds, we assessed priming with a hindpaw injection of PGE2. We observed that, similar to IL-6-induced priming, NGF was unable to produce the same magnitude of priming in eIF4ES209A mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4D; F(1,36) = 28.24, p < 0.0001). To examine whether changes in thermal hypersensitivity were also present in these mice, we used the Hargreaves test (Hargreaves et al., 1988) in mice treated with NGF. We observed decreased thermal hyperalgesia in eIF4ES209A mice compared with WT mice (Fig. 4E; F(3,40) = 44.08, p < 0.0001) and a transient thermal hypersensitivity during priming in WT mice, but no change in eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 4F; F(3,40) = 7.209, p = 0.0006).

Likewise, the specific PAR2 agonist 2at-LIGRL (20 ng) evoked mechanical hypersensitivity and hyperalgesic priming precipitated by PGE2 in WT mice, but this effect was strongly reduced in eIF4ES209A mice [Fig. 4G (F(1,50) = 33.57, p < 0.0001), H (F(1,30) = 40.25, p < 0.0001)]. These results indicate that eIF4E phosphorylation is a key downstream event for pronociceptive factors that act via the ERK pathway to promote mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity, but whether this also influences spontaneous, nonevoked components of pain is not known. We used the MGS (Langford et al., 2010) to determine this with hindpaw injection of 2at-LIGRL (20 ng). While PAR2 activation induced a robust grimacing in WT mice, this effect was reduced in eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 4I; F(1,18) = 9.176, p = 0.0072), suggesting that this signaling pathway is critical for the full expression of affective pain components downstream of ERK activation. Additionally, when we measured facial grimacing in response to PGE2 injection in mice previously injected with 2at-LIGRL, there was a significant increase in grimacing in WT mice but no change in facial expression scores in eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 4J; F(1,18) = 23.96, p < 0.0001).

Mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity induced by complex inflammatory stimuli are regulated by MNK1/2-eIF4E phosphorylation signaling

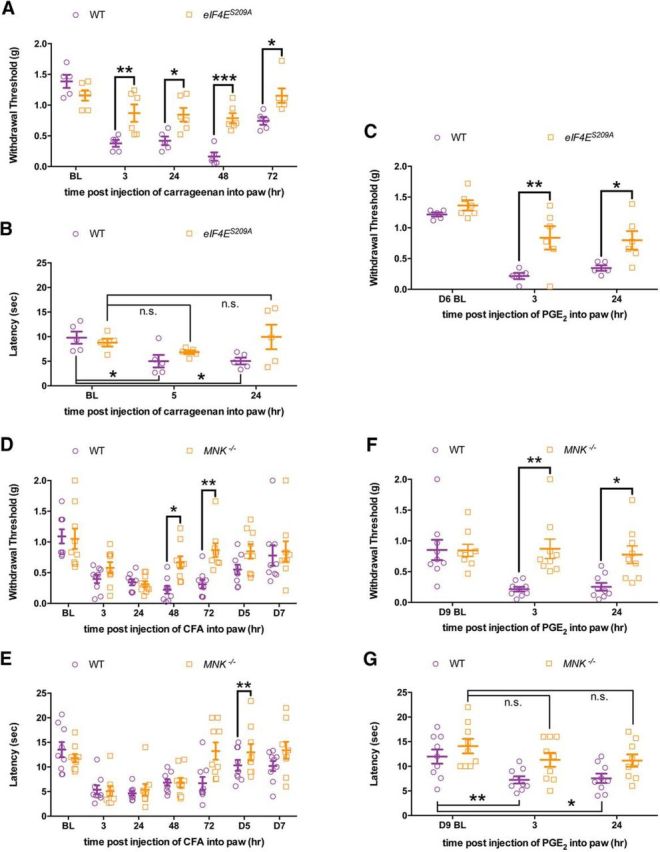

While the findings above indicate that eIF4E phosphorylation strongly contributes to mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity induced by algogens that signal via ERK, we asked whether eIF4E phosphorylation likewise plays an important role in mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity induced by inflammation. We used a hindpaw injection of carrageenan (0.5% w/v) in WT and eIF4ES209A mice and measured mechanical hypersensitivity (Fig. 5A; F(1,45) = 30.88, p < 0.0001) and thermal hypersensitivity (Fig. 5B; F(2,24) = 28.35, p = 0.05). WT mice developed robust mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity, whereas this effect was abrogated in eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 5A,B). When we tested whether carrageenan-induced hyperalgesic priming was dependent on eIF4E phosphorylation, we observed that WT mice developed increased long-lasting mechanical hypersensitivity compared with eIF4ES209A mice when priming was precipitated with PGE2 injection (Fig. 5C; F(1,27) = 17.69, p = 0.0003).

Figure 5.

MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling contributes to the development of mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity and hyperalgesic priming in response to inflammatory stimuli. A, B, Carrageenan (0.5% w/v) was injected into the hindpaw in both WT and eIF4ES209A mice. Hindpaw mechanical and thermal thresholds show that eIF4ES209A mice exhibited a blunted mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity compared with WT mice (n ≥ 5). C, eIF4ES209A mice developed reduced hyperalgesic priming when injected with PGE2 (n ≥ 5). D, E, Mnk1/2−/− mice injected with CFA (0.5 mg/ml, i.pl.; 10 μl) recover faster in both mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity compared with WT mice (n = 9). F, G, Mnk1/2−/− mice show decreased mechanical and thermal response to PGE2 after recovering from the initial hypersensitivity from CFA (n = 9). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001. BL, Baseline.

Additionally, we used mice lacking MNK1 and 2 (MNK−/− mice) and complete Freund's adjuvant (CFA) to further test the role of this signaling axis in inflammatory pain. We injected CFA (0.5 mg/ml in 10 μl) into the hindpaw of WT and MNK−/− mice. While we observed mechanical (Fig. 5D; F(1,112) = 13.27, p = 0.0004) and thermal (Fig. 5E; F(1,112) = 5.989, p = 0.016) hypersensitivity in both WT and MNK−/− mice at early time points, MNK−/− mice recovered faster than their WT littermates. When we tested whether MNK−/− mice transitioned into the primed state with a subsequent injection of PGE2, we saw reduced mechanical (Fig. 5F; F(1,48) = 15.58, p = 0.0003) and thermal (Fig. 5G; F(2,48) = 5.943, p = 0.005) hypersensitivity in MNK−/− mice but a robust response in WT mice.

Pharmacological inhibition of MNK1/2 with cercosporamide recapitulates eIF4ES209A phenotypes

To determine whether cercosporamide inhibits eIF4E phosphorylation in DRG neurons, these cells were cultured for 5 d and exposed to 10 μm cercosporamide (Altman et al., 2013) or vehicle for 1 h. Western blot analysis demonstrated a significant decrease of p-eIF4E in treated DRG neurons compared with vehicle (Fig. 6A; t = 6.6, df = 4, p = 0.027). Cercosporamide-treated DRG neurons showed no change in levels of p-4E-BP1 (Fig. 6B; t = 1.1, df = 4, p = 0.34), indicating that cercosporamide does not induce feedback activation of mTORC1. Levels of p-ERK were also unchanged (Fig. 6C; t = 0.32, df = 4, p = 0.76), demonstrating that upstream regulators of MNK1/2 are unaffected by cercosporamide, and are not activated via a feedback mechanism as we have shown previously for mTORC1 inhibitors (Melemedjian et al., 2013). We also assessed whether systemic injection of cercosporamide (40 mg/kg; Gkogkas et al., 2014) in mice influenced eIF4E phosphorylation. In DRG tissue taken 2 h after cercosporamide injection, we observed an ∼50% decrease in eIF4E phosphorylation (Fig. 6D; t = 4.5, df = 10, p = 0.0011), whereas no effect was observed in 4E-BP1 phosphorylation (Fig. 6E; t = 1.39, df = 4, p = 0.24).

Figure 6.

Local inhibition of MNK1/2 with cercosporamide reduces eIF4E phosphorylation, mechanical hypersensitivity, grimacing, and inhibits the development of hyperalgesic priming. A–C, In vitro treatment for 1 h of DRG neurons with cercosporamide (10 μm) decreased eIF4E phosphorylation (n = 3; A) but did not influence 4E-BP1 phosphorylation (B; n = 3) or ERK phosphorylation (C; n = 3). D, E, Injection of cercosporamide (40 mg/kg, i.p.) results in a decreased eIF4E phosphorylation in DRGs (n = 3; D) but does not affect 4E-BP1 phosphorylation (E; n = 3). F, G, Mechanical hypersensitivity induced by NGF (50 ng) or 2at-LIGRL (20 ng) was reduced by cercosporamide (10 μg, n ≥ 9). Similar to eIF4ES209A mice, pharmacological inhibition of MNK1/2 using cercosporamide attenuated the development of hyperalgesic priming induced by NGF (H) and 2at-LIGRL (I; n ≥ 5). J, K, Facial grimacing induced by the injection of 2at-LIGRL (20 ng, i.pl.) was also attenuated with local cercosporamide (10 μg) treatment (J) as was facial grimacing with subsequent PGE2 challenge (K; n ≥ 5). L, Immunostaining of glabrous skin for TRPV1 (red) and p-eIF4E (green) revealed that eIF4E phosphorylation is present in TRPV1-positive fibers in WT mice, but is absent in eIF4ES209A mice. Scale bar, 20 μm. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. BL, Baseline; Cerco, cercosporamide.

We then determined the effects of cercosporamide on NGF or PAR2 activation-induced mechanical hypersensitivity and hyperalgesic priming in vivo. Similar to observations in eIF4ES209A mice, treatment with cercosporamide [10 μg, intraplantar (i.pl.)] 15 min before treatment with NGF (Fig. 6F; F(1,114) = 11.43, p = 0.001) produced blunted mechanical hypersensitivity acutely. Similar results were obtained when 2at-LIGRL was applied in the presence or absence of cercosporamide (Fig. 6G; F(1,45) = 13.84, p = 0.0006). When animals treated with NGF or 2at-LIGRL were subsequently tested for hyperalgesic priming with PGE2 [Fig. 6H (F(1,54) = 37.72, p < 0.0001), I (F(1,75) = 9.62, p = 0.0027)], there was also a reduction in the magnitude of mechanical hypersensitivity. Moreover, coinjection of cercosporamide with 2at-LIGRL slightly attenuated grimacing recorded 3 h after injection (Fig. 6J; F(1,18) = 3.1 p = 0.010), although there was not a main effect for drug treatment in this experiment, and prevented facial grimacing (Fig. 6K; F(1,18) = 6.744, p = 0.018) in response to PGE2 injection, which again is consistent with observations in eIF4ES209A mice.

Our demonstration that hindpaw cercosporamide administration reduces behavioral pain plasticity suggests that p-eIF4E-mediated local translation in peripheral nociceptive fibers contributes to this effect. We therefore sought to evaluate whether p-eIF4E could be observed in nerve fibers innervating the hindpaw. Glabrous skin from both WT and eIF4ES209A mice was immunostained for TRPV1 and p-eIF4E and imaged. We observed p-eIF4E in TRPV1-positive nerve fibers in WT mice, and this staining was completely absent in eIF4ES209A mouse skin samples (Fig. 6L), demonstrating the specificity of this antibody and the presence of p-eIF4E in terminals of TRPV1-positive nociceptors.

eIF4E phosphorylation regulates DRG neuron excitability following NGF and IL-6 exposure

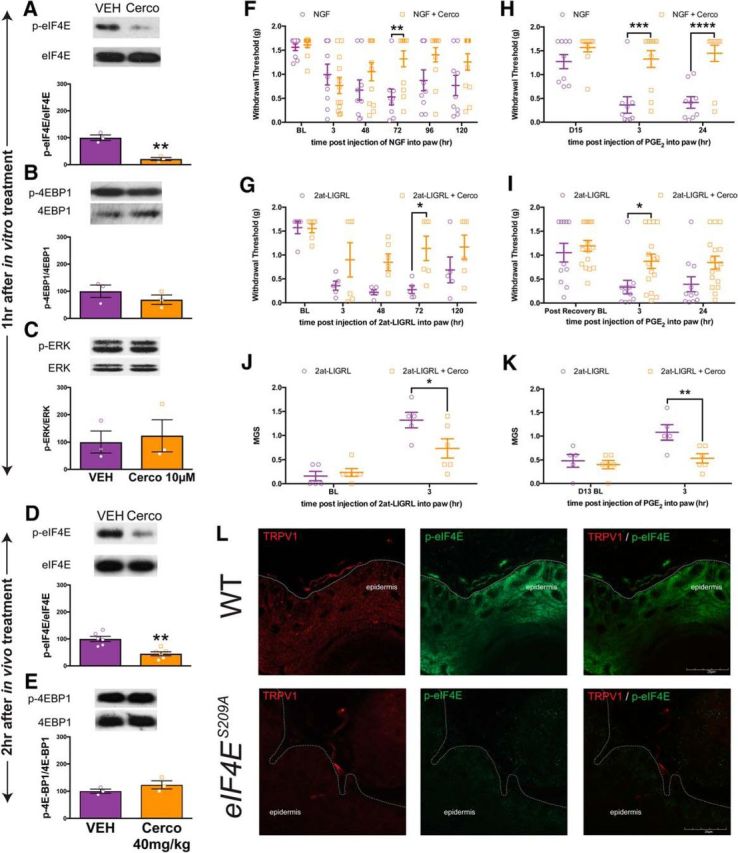

To directly test the effect of NGF and IL-6 on DRG neuron excitability in the presence and absence of eIF4E phosphorylation, we used patch-clamp electrophysiology. DRG neurons were isolated from WT and eIF4ES209A mice and exposed to 50 ng/ml NGF or vehicle for 18–24 h before recordings. In WT neurons, NGF caused an increase in the number of action potentials fired in response to slowly depolarizing ramp currents of 100 through 700 pA amplitudes (Fig. 7A; F(1,44) = 37.49, p < 0.0001). In contrast, DRG neurons isolated from eIF4ES209A mice showed elevated baseline excitability versus WT neurons but did not show a change in their excitability at any individual time points after exposure to the same concentration of NGF over an identical time course, although there was a significant main effect for NGF treatment (Fig. 7B; F(1,64) = 5.724, p = 0.02). For the DRG neurons sampled from both treatments and genotypes, there were no differences in membrane capacitance (Fig. 7C; F(3,27) = 0.4859, p = 0.70) or other parameters such as resting membrane potential (WT mice: −63.34 ± 1.12 mV, n = 10; eIF4ES209A mice: −61.63 ± 1.13 mV, n = 11; p < 0.05, t test). We next examined NGF-induced changes in DRG excitability in the presence of cercosporamide (10 μm) for 1 h before recordings. Analogous to eIF4ES209A DRG neurons, cercosporamide inhibited NGF-induced hyperexcitability (Fig. 7D; F(1,64) = 24.07, p < 0.0001), demonstrating that brief pharmacological inhibition of MNK1/2 reverses augmented excitability in DRG neurons induced by NGF treatment.

Figure 7.

MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling mediates NGF- and IL-6-induced changes in excitability in DRG neurons. A, WT DRG neurons were exposed to NGF or vehicle 18–24 h before patch-clamp recordings. Ramp current-evoked spiking demonstrates that NGF exposure increases the excitability of WT DRG neurons. B, eIF4ES209A DRG neurons showed no difference in the number of spikes evoked by ramp currents between NGF and vehicle-treated DRG neurons. C, Membrane capacitance measures between WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons show no difference in neuron size between samples demonstrating that small-diameter neurons were used for recordings. D, Pharmacological inhibition of MNK1/2 using cercosporamide (10 μm, n ≥ 9) recapitulated the effect seen in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons blocking NGF-induced hyperexcitability. E, F, IL-6 (50 ng/ml) exposure to WT DRG neurons for 1 h caused an increase in excitability compared with vehicle (E) but failed to do so in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons (F). G, Membrane capacitance between these samples was not different. N for each condition is shown in the appropriate bar. H, Cercosporamide blocked enhanced excitability induced by IL-6 in small-diameter DRG neurons (50 ng/ml; n ≥ 7). Traces shown in all panels are for the 700 pA stimulus. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. Cerco, Cercosporamide; VEH, vehicle.

Similar experiments were conducted with IL-6 (50 ng/ml), except that IL-6 was applied for only 1 h before patch-clamp recordings. IL-6, as we have observed previously in rat trigeminal ganglion neurons (Yan et al., 2012), caused an increase in the number of action potentials fired in response to ramp current injection at 300, 500, and 700 pA amplitudes (Fig. 7E; F(1,36) = 48.67, p < 0.0001). As we observed with NGF, IL-6 failed to increase the excitability of DRG neurons from eIF4ES209A mice at any time point and there was no main effect of IL-6 treatment (Fig. 7F; F(1,36) = 0.7019, p = 0.41). Again, there were no significant differences in membrane capacitance in the populations sampled for any of these experimental conditions (Fig. 7G; F(3,18) = 0.1955, p = 0.90). When we examined the effect of cercosporamide on IL-6-induced hyperexcitability, we found that, synonymous with eIF4ES209A DRG neurons, cercosporamide inhibited increased neuronal excitability induced by IL-6 treatment (Fig. 7H; F(1,52) = 31.22, p < 0.0001).

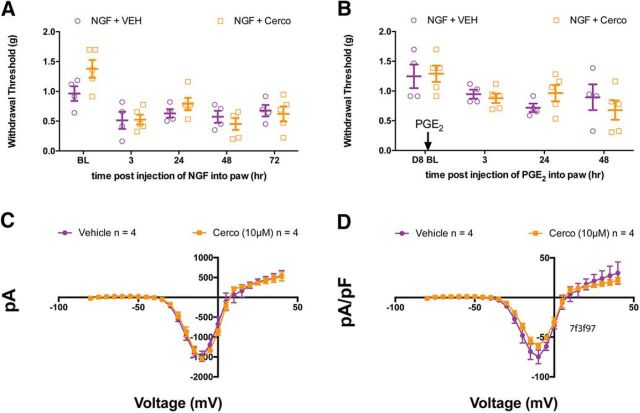

To assess whether cercosporamide is specific to MNK1/2 in our behavioral paradigm, we used cercosporamide in eIF4ES209A mice and measured mechanical hypersensitivity induced by NGF. We found no differences in NGF-induced mechanical hypersensitivity between cercosporamide and vehicle-injected eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 8A; F(1,35) = 1.297, p = 0.26). Subsequent injection of PGE2 to precipitate hyperalgesic priming additionally showed no difference in either eIF4ES209A mice previously injected with cercosporamide or vehicle (Fig. 8B; F(1,28) = 0.001, p = 0.99). While these behavioral results suggest that the actions of cercosporamide are specific to MNK1/2, we also tested for a possible acute effect of cercosporamide on VGNaCs that could lead to a decrease in excitability and confound results with this drug. VGNaC currents were elicited in cultured DRG neurons by 50 ms depolarizing steps, and currents were expressed as current density. Acute application of cercosporamide (10 μm) had no effect on VGNaC density, ruling out this possibility [Fig. 8C (F(1,150) = 0.038, p = 0.85), D (F(1,150) = 1.678, p = 0.20)].

Figure 8.

Cercosporamide has no additional effect in eIF4ES209A mice and no acute effect on sodium current density. A, Mechanical hypersensitivity induced by NGF (50 ng) showed no difference between eIF4ES209A mice that additionally received a hindpaw injection of cercosporamide (10 μg) and eIF4ES209A mice that did not (n ≥ 4; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA). B, Subsequent injection of PGE2 to precipitate priming also shows no difference between eIF4ES209A mice that previously received cercosporamide and eIF4ES209A mice that did not (n ≥ 4; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA). C, D, Sodium current (C) and sodium current density (D) were measured in WT DRG neurons with cercosporamide (10 μm) perfused acutely over a 5–10 s period (n = 4; p > 0.05, two-way ANOVA), indicating the cercosporamide does not block voltage-gated sodium channels at this concentration. BL, Baseline; Cerco, cercosporamide; VEH, vehicle.

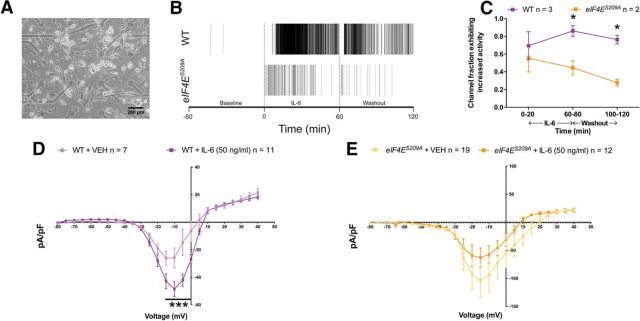

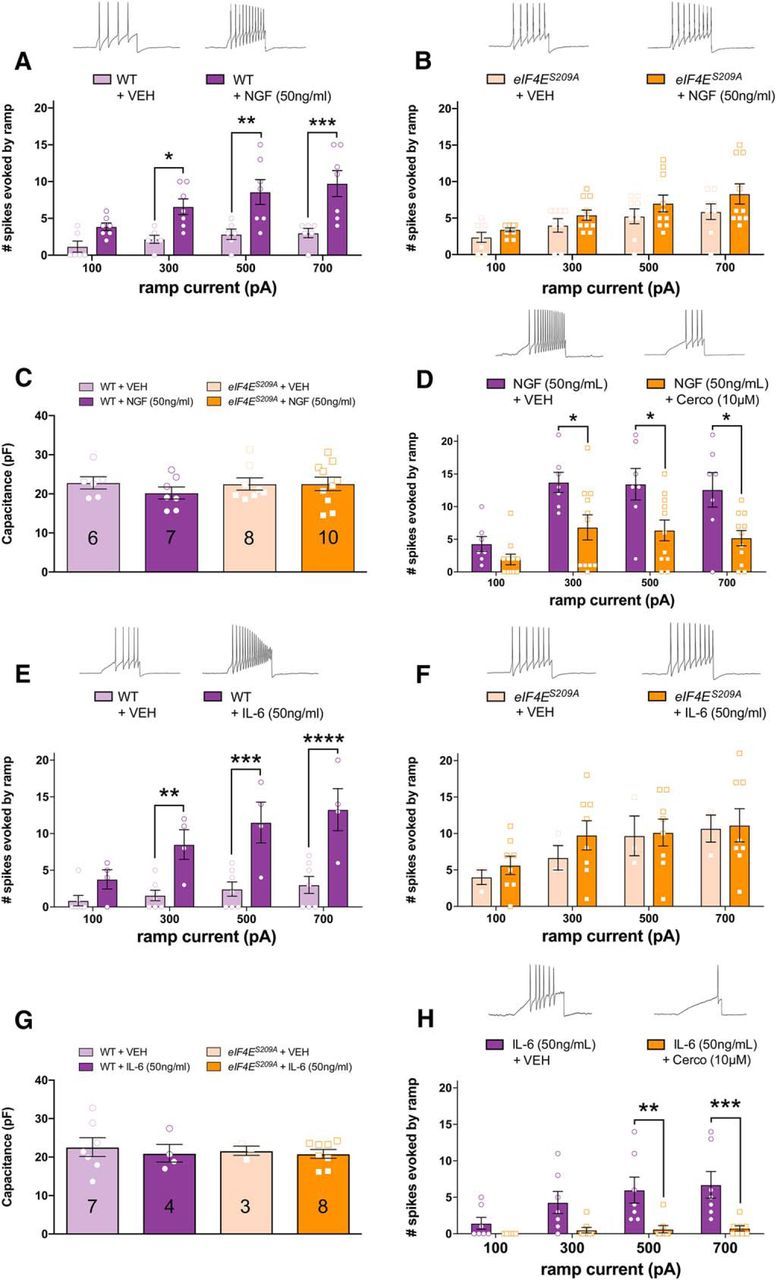

As an independent assay to support our whole-cell patch-clamp electrophysiological findings, we assessed excitability with extracellular recordings using MEAs. DRG neurons from both WT and eIF4ES209A mice were dissociated and cultured on MEA devices (Breckenridge et al., 1995; Potter and DeMarse, 2001; Frega et al., 2012; Enright et al., 2016; Fig. 9A) for 11–15 d before recordings. Action potentials were recorded for 1 h before IL-6 exposure, during 1 h of IL-6 (50 ng/ml) treatment, and again during a 1 h washout period. WT and eIF4ES209A neurons were mostly silent during recordings preceding IL-6 exposure. In WT DRG neurons, spiking was significantly increased during IL-6 treatment and was maintained during washout (Fig. 9B). In contrast, DRG neurons isolated from eIF4ES209A mice showed a brief increase in spiking in response to IL-6 that rapidly decreased to spiking rates that were significantly less than what was observed in WT neurons (Fig. 9C; F(1,9) = 15.48, p = 0.0034).

Figure 9.

IL6-induced sustained spiking and increased voltage-gated sodium current density is altered in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons. A, Image of DRG neurons cultured on an MEA device. Scale bar, 200 μm. B, Raster plot showing electrical activity of WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neuronal networks observed using MEAs during baseline, IL-6 treatment, and 1 h wash. C, IL-6 elicited increased spiking in WT DRG cultures during treatment that was sustained throughout the washout period and was significantly greater than the spiking observed in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons. D, E, Sodium current density was increased after 1 h of IL-6 exposure in WT DRG neurons but was decreased in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons (WT, n ≥ 7; eIF4ES209A, n ≥ 12). *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001.

The whole-cell patch-clamp and MEA experiments described above indicate that NGF and IL-6 increase excitability in WT neurons, but this response is blunted in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons. To further investigate the cellular mechanisms responsible for this effect, we examined the effect of IL-6 treatment on sodium current density. In DRG neurons from WT mice, there was a significant increase in sodium current density after 1 h of IL-6 treatment compared with vehicle, suggesting that IL-6 treatment altered the number of available VGNaCs or changed channel gating properties in WT DRG neurons (Fig. 9D; F(1,400) = 25.78, p < 0.0001). Consistent with voltage-ramp experiments, baseline VGNaC density was higher in eIF4ES209A neurons. However, these neurons failed to respond to IL-6 with an increase in VGNaC density (Fig. 9E; F(1,725) = 7.897, p = 0.005). In fact, we observed a trend toward decreased VGNaC density in eIF4ES209A mice. From these experiments, we conclude that, while baseline excitability and VGNaC availability may be higher in eIF4ES209A nociceptors, these neurons fail to respond to algogens with an increase in VGNaC-mediated responses. Importantly, this baseline increased VGNaC availability in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons does not lead to ectopic activity since no difference in spiking was observed at baseline in our MEA experiments (Fig. 9B,C), and it does not seem to be recapitulated by brief cercosporamide treatment because we did not observe enhanced excitability in whole-cell patch-clamp experiments with this drug (Fig. 8C,D).

eIF4E phosphorylation regulates IL-6-induced enhancements in Ca2+ signaling in DRG neurons

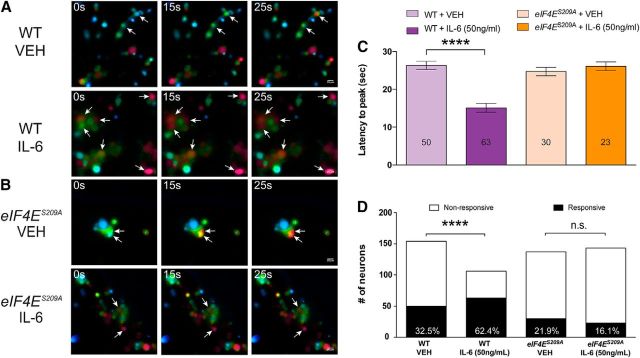

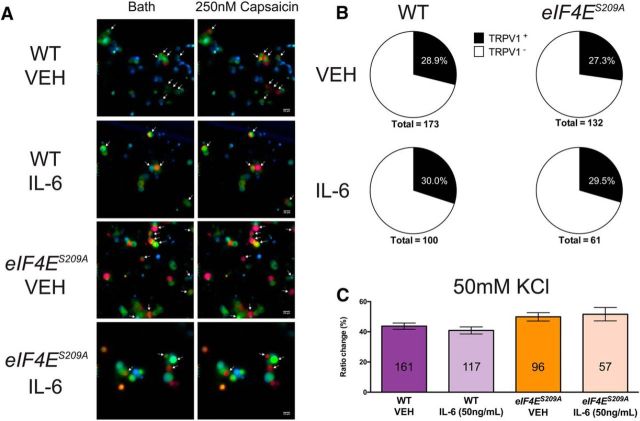

To further elucidate the role of eIF4E phosphorylation on DRG excitability, we investigated IL-6-induced changes in Ca2+ signaling in DRG neurons by measuring intracellular Ca2+ concentration [Ca2+]i with ratiometric imaging. Dissociated DRG neurons from both WT mice (Fig. 10A) and eIF4ES209A mice (Fig. 10B) were loaded with fura-2 and treated with either vehicle or IL-6 (50 ng/ml) for 1 h. Kinetic changes in [Ca2+]i in response to PGE2 (1 nm) were measured in all conditions. WT DRG neurons treated with IL-6 displayed a significant decrease in the latency to peak [Ca2+]i in response to PGE2 compared with vehicle-treated neurons (Fig. 10C; F(3,162) = 24.65, p < 0.0001). In contrast, DRG neurons isolated from eIF4ES209A mice showed no differences in the kinetics of PGE2-induced responses between IL-6 and vehicle treatments (Fig. 10C). On the other hand, the number of WT DRG neurons responding with a [Ca2+]i that rise above a threshold of 10% was drastically increased after IL-6 treatment, whereas no change was observed in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons (Fig. 10D; WT neurons: χ2 = 18.58, df = 1, p < 0.0001; eIF4ES209A neurons: χ2 = 1.541, df = 1, p = 0.21). Capsaicin-evoked changes in [Ca2+]i were equivalent in both WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons (Fig. 11A), and the proportion of TRPV1-positive DRG neurons (defined as those neurons responding to the specific agonist capsaicin) was the same in all conditions (Fig. 11B), which is consistent with our immunostaining results. Responses in [Ca2+]i evoked by increasing extracellular K+ from 5 to 50 mm were consistent between genotypes (Fig. 11C).

Figure 10.

IL-6 treatment alters PGE2 responsiveness in DRG neurons in an eIF4E phosphorylation-dependent fashion. A, B, WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons were cultured and treated with vehicle or IL-6 (50 ng/ml) for 1 h. PGE2 (1 nm) was perfused for 30 s, during which Ca2+ responses were measured. C, IL-6 treatment decreased the latency of PGE2-evoked Ca2+ release in WT DRG neurons compared with vehicle-treated WT neurons (n ≥ 50). D, The proportion of neurons responding to PGE2 was increased after IL-6 exposure in WT DRG neurons but was unchanged in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons. Scale bar, 20 μm. ****p < 0.0001. VEH, Vehicle.

Figure 11.

Normal Ca2+ signaling evoked by KCl and capsaicin in eIF4ES209A DRG neurons. A, WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons were imaged after 1 h of treatment with vehicle or IL-6 (50 ng) during vehicle-containing bath solution and capsaicin (250 nm)-containing bath solution perfusions. B, The proportion of TRPV1-positive neurons was unchanged in WT and eIF4ES209A DRG neurons treated with vehicle of IL-6. C, Moreover, Ca2+ signaling evoked by KCl (50 mm) was unchanged in all conditions (n ≥ 57 neurons/condition; p > 0.05, one-way ANOVA). Scale bar, 20 μm. VEH, Vehicle.

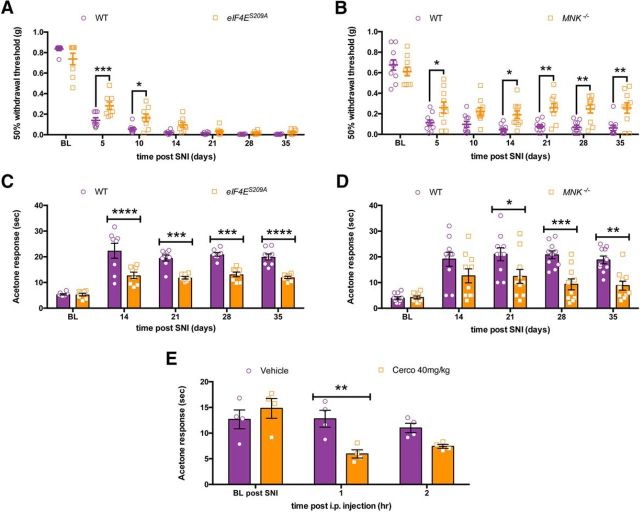

Cold hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury is reduced in eIF4ES209A and Mnk−/− mice

WT, Mnk−/− and eIF4ES209A mice were subjected to SNI surgery, and mechanical and cold hypersensitivity were measured over the ensuing 35 d. We observed a delay in the development of full mechanical hypersensitivity in eIF4ES209A mice, but by 14 d these mice developed mechanical hypersensitivity that was similar to their WT littermates (Fig. 12A; F(1,98) = 9.915, p = 0.0022). On the other hand, in Mnk−/− mice mechanical hypersensitivity after SNI was blunted in magnitude compared with WT mice (Fig. 12B; F(1,126) = 43.47, p < 0.0001). eIF4ES209A mice displayed significantly less cold hypersensitivity than WT littermates throughout the time course of the experiment (Fig. 12C; F(1,70) = 73.63, p < 0.0001), an effect that was also observed in Mnk−/− mice (Fig. 12D; F(1,90) = 31.82, p < 0.0001). Finally, we asked whether pharmacological inhibition of MNK1/2 with cercosporamide could alleviate cold hypersensitivity in SNI mice. We waited until 4 weeks after SNI (28 d), when mice display very stable cold hypersensitivity, and treated mice with vehicle or 40 mg/kg cercosporamide for 3 consecutive days. On the third day, we measured cold sensitivity using the acetone test. We observed decreased cold hypersensitivity in the cercosporamide-treated group at 1 h after the third injection of drug (Fig. 12E; F(1,18) = 6.041, p = 0.024), suggesting, that even late after the development of neuropathic pain, targeting MNK1/2 signaling to eIF4E is able to alleviate some aspects of neuropathic pain.

Figure 12.

Decreased neuropathic pain in eIF4ES209A mice and through MNK1/2 inhibition. A, Following SNI surgery eIF4ES209A mice show reduced mechanical hypersensitivity that normalizes 14 d following surgery compared with WT mice (n = 8). B, Mnk1/2−/− mice show blunted mechanical hypersensitivity lasting 35 d after SNI surgery (n = 10). C, Following SNI eIF4ES209A mice have a decrease in cold hypersensitivity as measured in the acetone test compared with WT mice (n = 8). D, Mnk1/2−/− mice show a sustained decrease in cold hypersensitivity after SNI compared with WT mice (n = 10). E, Following systemic administration of cercosporamide (40 mg/kg) for 3 d, WT mice show a transient decrease in cold hypersensitivity (n = 4). *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01; ***p < 0.001; ****p < 0.0001. BL, Baseline; Cerco, cercosporamide.

Discussion

The activity-dependent regulation of protein synthesis is a core mechanism mediating neuronal plasticity (Costa-Mattioli et al., 2009). In the nociceptive system, translation regulation pathways have been shown to contribute to the development and maintenance of pain hypersensitivity in a variety of preclinical models, suggesting that targeting these pathways may lead to new pain therapeutics (Price and Géranton, 2009; Obara et al., 2012; Melemedjian and Khoutorsky, 2015; Price and Inyang, 2015). Here we report that phosphorylation of eIF4E at S209 is a key biochemical event for the sensitization of DRG neurons by pronociceptive factors that are known to promote pain in rodents and humans, and that the loss of this phosphorylation event does not affect baseline pain behaviors or neurodevelopment in the nociceptive system. Our electrophysiological and Ca2+ imaging experiments show that the generation of nociceptor hyperexcitability is influenced by eIF4E phosphorylation by MNK1/2. Moreover, eIF4E phosphorylation plays a key role in the development of a chronic pain state, as reflected by deficiencies in peripherally mediated hyperalgesic priming and a loss of cold hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury. Our genetic and pharmacological experiments demonstrate that targeting MNK1/2 recapitulates the phenotype of eIF4ES209A mice pointing out that MNK1/2 might be advantageously targeted in the peripheral nervous system for the treatment and/or prevention of chronic pain conditions.

While upstream signaling factors like mTOR and MAPK have been implicated in pain plasticity using pharmacological tools and biochemical measures (Aley et al., 2001; Zhuang et al., 2004; Price et al., 2007; Jiménez-Díaz et al., 2008; Asante et al., 2009, 2010; Codeluppi et al., 2009; Géranton et al., 2009; Melemedjian et al., 2010, 2011, 2014; Obara et al., 2011; Ferrari et al., 2013), specific downstream mechanisms and mRNA targets linked to these kinase signaling cascades have been elusive until very recently. Recent evidence suggests that different translation regulation targets play strikingly uniquely roles in different aspects of pain sensitivity. For example, genetic loss of a major downstream target of mTORC1, 4E-BP1, leads solely to changes in mechanical sensitivity via central mechanisms governed by a synaptic adhesion molecule known as neuroligin 1 (Khoutorsky et al., 2015). In contrast, mice lacking a key phosphorylation site for eIF2α on a single allele have deficits in baseline thermal nociception without any changes in mechanical thresholds (Khoutorsky et al., 2016). This phenotype can be recapitulated with pharmacological modulation of eIF2α, and a deficit in thermal, but not mechanical, hyperalgesia is also associated with this pathway in inflammatory pain. Collectively, these studies suggest that individual translation regulation pathways may target specific subsets of genes that have profound impacts on certain aspects of nociception (e.g., thermal vs mechanical pain; Table 3, summary of previous findings compared with the present article). We previously showed that NGF and IL-6 are capable of promoting eIF4E phosphorylation in nociceptors in vitro and that disrupting eIF4F complex formation with 4EGI-1 leads to a blockade of the development of mechanical hypersensitivity and hyperalgesic priming by these pronociceptive factors (Melemedjian et al., 2010; Tillu et al., 2015). Here we used eIF4ES209A and MNK−/− mice and pharmacological tools to definitively demonstrate that eIF4E phosphorylation is a core biochemical event modulating how inflammatory stimuli promote mechanical and thermal hypersensitivity, spontaneous pain responses, and the development of a chronic pain state. These findings distinguish the MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling cascade from 4E-BP1 and eIF2α signaling, which have specific effects on certain pain modalities. Our results support the conclusion that MNK1/2–eIF4E signaling plays an important role in altering the excitability of a wide population of nociceptors because genetic and pharmacological manipulation of this pathway had robust effects on thermal and mechanical hypersensitivity, as well as spontaneous pain. In our view, this identifies MNK1/2-mediated eIF4E phosphorylation as a crucial target for plasticity in nociceptors that drives the development of a chronic pain state. MNK1/2-dependent signaling to eIF4E therefore represents a strong mechanistic target for pharmacological manipulation of chronic pain.

Table 3.

Different translation regulation pathways control different aspects of pain and pain amplification

| Mutant mouse | Thermal | Mechanical | Thermal hyperalgesia | Mechanical hyperalgesia | Proposed mechanism |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eIF4ES209A | Normal | Normal | Decreased to inflammatory stimuli | Decreased to inflammatory stimuli | Decreased nociceptor plasticity |

| MNK−/− | Normal | Normal | Decreased to inflammatory stimuli | Decreased to inflammatory stimuli and neuropathic | Decreased nociceptor plasticity |

| Eif4ebp1−/− (Khoutorsky et al., 2015) | Normal | Increased sensitivity | Not tested | Increased hypersensitivity to inflammatory stimuli | Decreased spinal neuroligin 1 |

| eIF2α+/S51A (Khoutorsky et al., 2016) | Decreased sensitivity | Normal | Not tested | Decreased hypersensitivity to inflammatory stimuli | Decreased TRPV1 functional activity in DRG |

| Fmr1 KO (Price et al., 2007) | Normal | Normal | Not tested | Decreased hypersensitivity to inflammatory and neuropathic stimuli | Decreased spinal and peripheral mGluR1/5 and mTOR signaling |

Cold hypersensitivity induced by peripheral nerve injury was decreased in eIF4ES209A mice, but mechanical hypersensitivity developed normally, albeit with a delay to reach its full magnitude. This is in contrast to a clear deficit in mechanical hypersensitivity induced by inflammation or common inflammatory mediators. A potential explanation is that mechanisms involved in changes in mechanical reflex withdrawal responses after peripheral nerve injury are dependent on centrally mediated effects, for instance downregulation of KCC2 function (Coull et al., 2003; Price and Prescott, 2015). This would suggest that different subsets of peripheral afferents are responsible for mechanical hypersensitivity under different injury conditions. In fact, mechanical hypersensitivity following nerve injury persists even when the vast majority of C-fibers are eliminated (Abrahamsen et al., 2008; Minett et al., 2014). On the other hand, eliminating neurons in the TRPM8 lineage is sufficient to eliminate cold hypersensitivity after peripheral nerve injury (Knowlton et al., 2013). We observed a strong decrease in cold hypersensitivity induced by nerve injury in eIF4ES209A and Mnk−/− mice, and cercosporamide treatment was able to lead to a transient decrease in cold hypersensitivity. Therefore, our findings are consistent with the notion that MNK–eIF4E signaling is a key signaling hub for the sensitization of peripheral nociceptive neurons but that this signaling pathway is dispensable for the generation of mechanical hypersensitivity after nerve injury. In the nerve injury scenario, this mechanical hypersensitivity could be generated exclusively via Aβ-fiber input coupled to spinal dorsal horn disinhibitory mechanisms such as those observed after spinal BDNF (Lee and Prescott, 2015), cytokine (Kawasaki et al., 2008), chemokine (Gosselin et al., 2005), or PGE2 (Ahmadi et al., 2002) application or with traumatic injury to peripheral nerves (Coull et al., 2005; Abrahamsen et al., 2008; Minett et al., 2014). Another possibility is that different translation regulation mechanisms are involved in mechanical hypersensitivity after nerve injury. Interestingly, AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activators reduce neuropathic mechanical hypersensitivity in rats and mice (Melemedjian et al., 2010). AMPK activation inhibits both mTOR and MAPK pathway signaling (Melemedjian et al., 2010). Therefore, only influencing an end point of MAPK signaling in the reduction of eIF4E phosphorylation may be insufficient to reduce neuropathic mechanical hypersensitivity, and additional inhibition of mTOR signaling may be needed.

Despite intact normal acute pain behavior and anatomy in eIF4ES209A mice, we observed that DRG neurons surprisingly trended toward higher levels of excitability in response to slowly depolarizing ramp currents and a larger baseline sodium current density. On the other hand, these neurons fail to demonstrate a change in excitability in response to either IL-6 or NGF in vitro, an effect that is reflected in a behavioral deficit in vivo. A recent study (Martínez et al., 2015) revealed that eIF4E phosphorylation is mechanistically linked to stress granule formation and mRNA sequestration through an interaction with the eIF4E-interacting protein 4E-T and that this leads to the suppression of translation of some mRNAs. While this has not been explored in neurons, it is possible that eIF4E phosphorylation can suppress the translation of certain mRNA species under some circumstances and promote the translation of the same, or other, mRNAs in different circumstances, for instance in response to inflammatory mediators in DRG nociceptors. Such a mechanism linked to eIF4E phosphorylation could lead to the cellular phenotype of increased basal excitability but a loss of induced hyperexcitability in the complete absence of eIF4E phosphorylation. In fact, similar phenotypes have been consistently observed in Fmr1 knock-out mice (a model of fragile X syndrome), leading to baseline alterations in neuronal excitability or in signaling pathway efficacy coupled with a lack of plasticity (Grossman et al., 2006; Hanson and Madison, 2007; Pfeiffer and Huber, 2007; Bureau et al., 2008), including in the nociceptive system (Price et al., 2007). Interestingly, recent studies found that eIF4E phosphorylation is enhanced in fragile X syndrome and that crossing mice lacking fragile X mental retardation protein with eIF4ES209A mice or treating Fmr1 mutant mice with cercosporamide rescues many phenotypes in these mice (Gkogkas et al., 2014).

An unanswered question arising from this work is what are the key mRNA targets for eIF4E phosphorylation in the context of nociceptor excitability. Our electrophysiology and Ca2+ imaging experiments provide some possible clues. The trafficking of channels to the membrane is an important regulatory mechanism for nociceptor excitability (Matsuoka et al., 2007; Hudmon et al., 2008; Andres et al., 2013). Our findings are consistent with a model where eIF4E phosphorylation enhances the translation of a subset of mRNAs that influence the membrane trafficking of voltage-gated channels (e.g., VGNaCs, consistent with our current density experiments) and G-protein-coupled receptors (e.g., PGE2 receptors, consistent with our Ca2+ imaging experiments) to enhance nociceptor excitability and increase their responsiveness to inflammatory mediators. While we cannot currently pinpoint the identity of these locally translated mRNAs, we have now identified a precise signaling event that can be manipulated to identify these mRNAs. Discovering these eIF4E-controlled mRNAs will yield significant insight into how nociceptors alter their excitability downstream of initial phosphorylation events that are likely more transient than the synthesis of new proteins that contribute to the maintenance of long-term nociceptor plasticity.

Notes

Supplemental material for this article is available at http://www.utdallas.edu/bbs/painneurosciencelab/index.html. This consists of raw data files for all figures in the manuscript. This material has not been peer reviewed.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R01-NS-065926 (T.J.P.), R01-GM-102575 (T.J.P. and G.D.), R01-NS-073664 (T.J.P., S.B., and J.V.), The University of Texas STARS program (T.J.P. and G.D.), and the postdoctoral Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia fellowship program 274414 (P.B.-I.).

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

References

- Abrahamsen B, Zhao J, Asante CO, Cendan CM, Marsh S, Martinez-Barbera JP, Nassar MA, Dickenson AH, Wood JN (2008) The cell and molecular basis of mechanical, cold, and inflammatory pain. Science 321:702–705. 10.1126/science.1156916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmadi S, Lippross S, Neuhuber WL, Zeilhofer HU (2002) PGE(2) selectively blocks inhibitory glycinergic neurotransmission onto rat superficial dorsal horn neurons. Nat Neurosci 5:34–40. 10.1038/nn778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aley KO, Martin A, McMahon T, Mok J, Levine JD, Messing RO (2001) Nociceptor sensitization by extracellular signal-regulated kinases. J Neurosci 21:6933–6939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altman JK, Szilard A, Konicek BW, Iversen PW, Kroczynska B, Glaser H, Sassano A, Vakana E, Graff JR, Platanias LC (2013) Inhibition of Mnk kinase activity by cercosporamide and suppressive effects on acute myeloid leukemia precursors. Blood 121:3675–3681. 10.1182/blood-2013-01-477216 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andres C, Hasenauer J, Ahn HS, Joseph EK, Isensee J, Theis FJ, Allgöwer F, Levine JD, Dib-Hajj SD, Waxman SG, Hucho T (2013) Wound-healing growth factor, basic FGF, induces Erk1/2-dependent mechanical hyperalgesia. Pain 154:2216–2226. 10.1016/j.pain.2013.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante CO, Wallace VC, Dickenson AH (2009) Formalin-induced behavioural hypersensitivity and neuronal hyperexcitability are mediated by rapid protein synthesis at the spinal level. Mol Pain 5:27. 10.1186/1744-8069-5-27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asante CO, Wallace VC, Dickenson AH (2010) Mammalian target of rapamycin signaling in the spinal cord is required for neuronal plasticity and behavioral hypersensitivity associated with neuropathy in the rat. J Pain 11:1356–1367. 10.1016/j.jpain.2010.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asiedu MN, Tillu DV, Melemedjian OK, Shy A, Sanoja R, Bodell B, Ghosh S, Porreca F, Price TJ (2011) Spinal protein kinase M ζ underlies the maintenance mechanism of persistent nociceptive sensitization. J Neurosci 31:6646–6653. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6286-10.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogen O, Alessandri-Haber N, Chu C, Gear RW, Levine JD (2012) Generation of a pain memory in the primary afferent nociceptor triggered by PKCε activation of CPEB. J Neurosci 32:2018–2026. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5138-11.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boitano S, Flynn AN, Schulz SM, Hoffman J, Price TJ, Vagner J (2011) Potent agonists of the protease activated receptor 2 (PAR2). J Med Chem 54:1308–1313. 10.1021/jm1013049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breckenridge LJ, Wilson RJ, Connolly P, Curtis AS, Dow JA, Blackshaw SE, Wilkinson CD (1995) Advantages of using microfabricated extracellular electrodes for in-vitro neuronal recording. J Neurosci Res 42:266–276. 10.1002/jnr.490420215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bureau I, Shepherd GM, Svoboda K (2008) Circuit and plasticity defects in the developing somatosensory cortex of FMR1 knock-out mice. J Neurosci 28:5178–5188. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1076-08.2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carracedo A, Ma L, Teruya-Feldstein J, Rojo F, Salmena L, Alimonti A, Egia A, Sasaki AT, Thomas G, Kozma SC, Papa A, Nardella C, Cantley LC, Baselga J, Pandolfi PP (2008) Inhibition of mTORC1 leads to MAPK pathway activation through a PI3K-dependent feedback loop in human cancer. J Clin Invest 118:3065–3074. 10.1172/JCI34739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaplan SR, Bach FW, Pogrel JW, Chung JM, Yaksh TL (1994) Quantitative assessment of tactile allodynia in the rat paw. J Neurosci Methods 53:55–63. 10.1016/0165-0270(94)90144-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Codeluppi S, Svensson CI, Hefferan MP, Valencia F, Silldorff MD, Oshiro M, Marsala M, Pasquale EB (2009) The Rheb-mTOR pathway is upregulated in reactive astrocytes of the injured spinal cord. J Neurosci 29:1093–1104. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4103-08.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa-Mattioli M, Sossin WS, Klann E, Sonenberg N (2009) Translational control of long-lasting synaptic plasticity and memory. Neuron 61:10–26. 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.10.055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JA, Boudreau D, Bachand K, Prescott SA, Nault F, Sík A, De Koninck P, De Koninck Y (2003) Trans-synaptic shift in anion gradient in spinal lamina I neurons as a mechanism of neuropathic pain. Nature 424:938–942. 10.1038/nature01868 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coull JA, Beggs S, Boudreau D, Boivin D, Tsuda M, Inoue K, Gravel C, Salter MW, De Koninck Y (2005) BDNF from microglia causes the shift in neuronal anion gradient underlying neuropathic pain. Nature 438:1017–1021. 10.1038/nature04223 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enright HA, Felix SH, Fischer NO, Mukerjee EV, Soscia D, Mcnerney M, Kulp K, Zhang J, Page G, Miller P, Ghetti A, Wheeler EK, Pannu S (2016) Long-term non-invasive interrogation of human dorsal root ganglion neuronal cultures on an integrated microfluidic multielectrode array platform. Analyst 141:5346–5357. 10.1039/C5AN01728A [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari LF, Bogen O, Chu C, Levine JD (2013) Peripheral administration of translation inhibitors reverses increased hyperalgesia in a model of chronic pain in the rat. J Pain 14:731–738. 10.1016/j.jpain.2013.01.779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari LF, Araldi D, Levine JD (2015a) Distinct terminal and cell body mechanisms in the nociceptor mediate hyperalgesic priming. J Neurosci 35:6107–6116. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5085-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrari LF, Bogen O, Reichling DB, Levine JD (2015b) Accounting for the delay in the transition from acute to chronic pain: axonal and nuclear mechanisms. J Neurosci 35:495–507. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5147-13.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flynn AN, Tillu DV, Asiedu MN, Hoffman J, Vagner J, Price TJ, Boitano S (2011) The protease-activated receptor-2-specific agonists 2-aminothiazol-4-yl-LIGRL-NH2 and 6-aminonicotinyl-LIGRL-NH2 stimulate multiple signaling pathways to induce physiological responses in vitro and in vivo. J Biol Chem 286:19076–19088. 10.1074/jbc.M110.185264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frega M, Pasquale V, Tedesco M, Marcoli M, Contestabile A, Nanni M, Bonzano L, Maura G, Chiappalone M (2012) Cortical cultures coupled to micro-electrode arrays: a novel approach to perform in vitro excitotoxicity testing. Neurotoxicol Teratol 34:116–127. 10.1016/j.ntt.2011.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furic L, Rong L, Larsson O, Koumakpayi IH, Yoshida K, Brueschke A, Petroulakis E, Robichaud N, Pollak M, Gaboury LA, Pandolfi PP, Saad F, Sonenberg N (2010) eIF4E phosphorylation promotes tumorigenesis and is associated with prostate cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 107:14134–14139. 10.1073/pnas.1005320107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Géranton SM, Jiménez-Díaz L, Torsney C, Tochiki KK, Stuart SA, Leith JL, Lumb BM, Hunt SP (2009) A rapamycin-sensitive signaling pathway is essential for the full expression of persistent pain states. J Neurosci 29:15017–15027. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3451-09.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gkogkas CG, Khoutorsky A, Cao R, Jafarnejad SM, Prager-Khoutorsky M, Giannakas N, Kaminari A, Fragkouli A, Nader K, Price TJ, Konicek BW, Graff JR, Tzinia AK, Lacaille JC, Sonenberg N (2014) Pharmacogenetic inhibition of eIF4E-dependent Mmp9 mRNA translation reverses fragile X syndrome-like phenotypes. Cell Rep 9:1742–1755. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.10.064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gosselin RD, Varela C, Banisadr G, Mechighel P, Rostene W, Kitabgi P, Melik-Parsadaniantz S (2005) Constitutive expression of CCR2 chemokine receptor and inhibition by MCP-1/CCL2 of GABA-induced currents in spinal cord neurones. J Neurochem 95:1023–1034. 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03431.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]