Summary

Objective

The Cox-Maze IV procedure has been shown to be an effective treatment for atrial fibrillation when performed concomitantly with other operations either via median sternotomy or right minithoracotomy. Few studies have compared these approaches in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. This study examined outcomes with sternotomy versus minithoracotomy in stand-alone Cox-Maze IV procedures at our institution.

Methods

Between 2002 and 2015, 195 patients underwent stand-alone biatrial Cox-Maze IV. Minithoracotomy was used in 75 patients, sternotomy in 120. Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias was ascertained using EKG, Holter, or pacemaker interrogation at 3-60 months. Predictors of recurrence were determined using logistic regression.

Results

Of 23 preoperative variables, the only differences between groups were that minithoracotomy patients had a higher rate of NYHA 3/4 symptoms and a lower rate of prior stroke. Minithoracotomy and sternotomy patients had similar atrial fibrillation duration and type. Minithoracotomy patients had a smaller LA diameter (4.5 vs. 4.8 cm, p=0.03). More minithoracotomy patients received a box lesion (73/75 vs. 100/120, p=0.002). Minithoracotomy patients had a shorter hospital stay (7 vs. 8 days, p=0.009) and a similar rate of major complications (3/75 (4%) vs. 7/120 (6%), p=0.74). There were no differences in mortality or freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias. Predictors of atrial fibrillation recurrence included a preoperative pacemaker, omission of the left atrial roof line, and NYHA 3/4 symptoms.

Conclusions

Stand-alone Cox-Maze IV via minithoracotomy was as effective as via sternotomy with a shorter hospital stay. A minimally invasive approach is our procedure of choice.

Keywords: atrial fibrillation, ablation, Cox-Maze IV, stand-alone

Introduction

The first successful surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation was performed by Dr. James L. Cox in 1987.1 The last iteration of this operation, the Cox-Maze III procedure, became the gold standard for the treatment of atrial fibrillation for over a decade. In this procedure, surgical incisions in both atria were used to create lines of conduction block to prevent atrial fibrillation. During the 2000's, the introduction of the use of ablation devices by our group and others made surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation safer and more widely performed.2-4 In 2002, a modified Cox-Maze procedure using ablation devices to replace most of the atrial incisions, the Cox-Maze IV, was introduced and has been widely accepted. A majority of surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation is performed concomitantly with other cardiac surgical procedures, especially mitral valve surgery. Our group has previously shown that a minimally invasive approach is as effective as a median sternotomy approach for a mixed group of patients, most of whom underwent concomitant procedures.5 There is a growing evidence base that concomitant surgical ablation should be considered standard of care for patients with preoperatively diagnosed atrial fibrillation undergoing cardiac surgery.

Patients undergoing stand-alone surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation represent a very different patient population. These patients have frequently undergone multiple trials of antiarrhythmic drug therapy as well as failed catheter ablation procedures. In our experience, their atria are frequently scarred, and have undergone significant remodeling. In the last multi-specialty consensus statement, the indications for surgical ablation in patients with lone atrial fibrillation include patients with symptomatic atrial fibrillation refractory or intolerant to at least one Vaughan-Williams class I or III antiarrhythmic drug who have failed catheter or prefer a surgical approach.6 Since these patients have no other cardiac pathology, it is imperative that procedures performed in these patients be as safe and effective as possible. Weimar and colleagues last reported our center's experience with this procedure in 2012, including patients who underwent a Cox-Maze III or a Cox-Maze IV.7 The Cox-Maze IV procedure was as effective as the Cox-Maze III with shorter operative times and a lower rate of major complications. Over the last decade, numerous groups have also introduced less invasive surgical approaches. In 2013, Ad and colleagues published a series of 104 stand-alone Cox-Maze procedures performed using cryothermal energy through a right minithoracotomy with 80% of patients free from atrial fibrillation and antiarrhythmic drugs at 36 months.8 Chitwood and colleagues have had similar results with a minimally invasive Cox-Maze procedure using cryothermal ablation. They reported a 41-patient series in 2007 with 87% of patients in sinus rhythm at one year.9 However, neither of these series directly compared their novel minimally invasive procedures to a traditional open approach. The purpose of this study was to compare a minimally invasive Cox-Maze IV procedure performed with bipolar radiofrequency ablation and cryoablation to a Cox-Maze IV procedure using the same ablation technology via a median sternotomy approach.

Methods

The Institutional Review Board at our institution approved this study, and written informed consent was obtained from each patient prior to their enrollment. Over 400 demographic and perioperative variables were prospectively entered into The Society of Thoracic Surgeons database and a longitudinal database maintained at our institution.

Patient Population

Between January 2002 and October 2015, 195 consecutive patients underwent stand-alone biatrial CMIV at our institution. Our group has previously published detailed descriptions of the CMIV operative technique, performed via a median sternotomy or a right minithoracotomy.10, 11 Briefly, the steps of the right minithoracotomy approach to the operation are as follows. The patient is positioned supine, and general anesthesia is induced. A double-lumen endotracheal tube, a radial arterial line, and a central venous catheter are placed. Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) is used to confirm the absence of thrombus in the left atrial appendage. The right chest is then elevated to a 30-45° angle. The patient is marked, prepped and draped in sterile fashion. Femoral cannulation for cardiopulmonary bypass is obtained via a cutdown. The guidewires and cannulae are advanced into the descending thoracic aorta and the right atrium using TEE visualization. A 5-6 cm mini-thoracotomy is then made over the fourth intercostal space lateral to the nipple in the mid-axillary line in men; a submammary incision is used in women. A small segment of the posterior fifth rib is removed, and a soft tissue retractor is used to improve visualization. A Blake drain is placed through the lateral chest wall, and carbon dioxide is infused to prevent air embolism.

After the pericardium is opened, thoracoscope is placed through a port in the sixth intercostal space near the posterior axillary line. The SVC and IVC are mobilized and the right pulmonary veins are dissected. The right pulmonary veins are dissected and encircled with umbilical tape. Pacing thresholds are obtained from the right pulmonary veins. The right pulmonary veins are then isolated using three sequential ablations of a cuff of atrial tissue around the veins with a bipolar radiofrequency device. Ablation is continued until exit block is obtained. Exit block is tested by pacing the pulmonary veins at two times the previously documented pacing threshold while monitoring the surface electrocardiogram for capture.

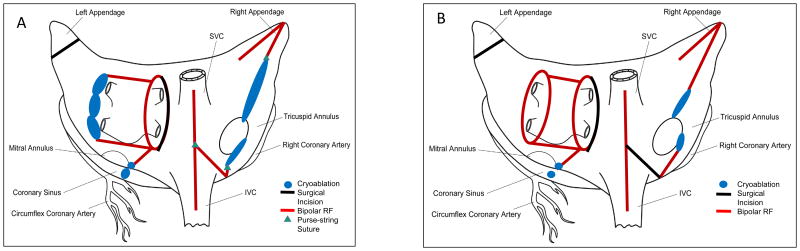

The Cox-Maze IV lesion set is shown in schematic form in Figure 1A. The right atrial lesions are created on cardiopulmonary bypass but before aortic cross-clamping. Three purse-string sutures are placed: one above the interatrial septum midway between the SVC and the IVC, one on the right atrial free wall near the atrioventricular groove, and one at the base of the right atrial appendage. The bipolar radiofrequency clamp is placed through the first purse-string suture is used to create three lesions: one toward the SVC, one toward the IVC, and one along the right atrial free wall. The device is fired three times with slight changes in position for each lesion. The second purse-string suture is placed at the end of the free wall lesion. A reusable linear cryoprobe is placed endocardially through the purse-string toward the tricuspid annulus at the 1 o'clock position. This cryoablation is performed by freezing to -60 °C for three minutes, as are all subsequent cryoablations. The third purse-string suture is opened with a stab incision, and the bipolar radiofrequency clamp is used to make a lesion toward the SVC at least 2 cm away from the previous SVC lesion. An endocardial cryoablation is then made to the tricuspid annulus at the 11 o'clock position with the linear cryoprobe.

Figure 1.

Schematic demonstrating the Cox-Maze IV lesion set. A – right minithoracotomy approach; B – median sternotomy approach.

The left atrium is then dissected and opened in the interatrial groove. Exposure is obtained using an atrial lift retractor. The bipolar radiofrequency clamp is used to make “roof” and “floor” lesions from the atriotomy to the left superior and inferior pulmonary veins, respectively. The clamp is also used to create an ablation from the inferior margin of the atriotomy toward the mitral annulus, taking care to avoid the circumflex coronary artery. As the bipolar clamp cannot reach the annulus itself, a bell-shaped cryoprobe is used to make an endocardial lesion to the mitral annulus and an epicardial lesion over the coronary sinus. The left atrial “box” is completed by using a linear cryoprobe to create a lesion behind the left pulmonary veins, along the lateral ridge, connecting the roof and floor lesions. The left atrial appendage is managed by oversewing its orifice in two layers from an endocardial approach.

The median sternotomy lesion set is shown in Figure 1B. It is similar to the right minithoracotomy lesion set but includes a right atriotomy and left pulmonary vein isolation using the bipolar radiofrequency clamp. The left atrial appendage is amputated and oversewn rather than endocardially oversewing it with the sternotomy approach.

It should be noted that in 2005, the CMIV was modified to include a superior connecting “roof” lesion between the left and right superior pulmonary veins, which has been shown to improve freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (Figure 1).12, 13 This box lesion was performed in 100 of 120 (83%) of patients undergoing CMIV via a median sternotomy and in 73 of 75 (97%) of patients undergoing CMIV via right minithoracotomy. Preoperative and perioperative variables were retrospectively evaluated and compared.

Follow-up

Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias (ATAs) and from antiarrhythmic drugs (AADs) at 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years were evaluated by electrocardiogram or by prolonged monitoring (24-hour Holter, pacemaker interrogation, or implantable loop recorder interrogation), as recommended by consensus guidelines.6 Success was defined as freedom from ATAs (AF, atrial flutter, or atrial tachycardia) after a 3-month blanking period as defined by consensus guidelines.6 As a part of routine postoperative care, patients were maintained on class I or III AADs and warfarin for at least 2 months after surgery unless they had specific contraindications. AADs were discontinued at 2 months if normal sinus rhythm was maintained; anticoagulation was discontinued at 3 months if no AF was found on prolonged monitoring and no left atrial stasis was found on echocardiography. Calcium channel blockers and beta blockers were not considered to be AADs.

Mean follow-up was 2.9 ± 1.9 years. At 1, 2, 3, 4 and 5 years after surgery, respectively, follow-up was 161 of 186 (86.6%), 113 of 161 (70.2%), 83 of 145 (57.2%), 70 of 129 (54.3%), and 60 of 104 (57.7%). Prolonged continuous monitoring was obtained in 110 of 161 (68.3%), 69 of 113 (61.1%), 52 of 83 (62.3%), 47 of 70 (67.1%) and 33 of 60 (55.0%), at each time point. Freedom from ATAs and AADs at each time point was compared between those who underwent CMIV via a median sternotomy and those who underwent CMIV via a right minithoracotomy (RMT).

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or as median with range. Student's t test was used to compare means of normally distributed continuous variables. The Mann-Whitney U nonparametric test was used to compare distributions of skewed continuous variables. Categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages, and outcomes were compared using the χ2 test or Fisher's exact test. Twenty-three preoperative and perioperative variables were evaluated in univariate logistic regression to identify potential predictors of ATA recurrence at 1 year. Significant covariates (p < 0.10) and factors believed to be significant predictors of recurrence in our clinical experience were entered into a multivariable logistic regression model. All statistical analyses were performed using R version 3.2.5 (R Foundation, Vienna, 2016).

Results

Demographics

Preoperative demographic data are shown in Table 1. The mean overall age was 58 ± 10 years, and 136 of 195 (69.7%) of the population were men. Of the overall cohort, 55 of 195 (28.2%) of the population had paroxysmal AF, 12 of 195 (6.2%) had persistent AF, and 128 of 195 (65.6%) had longstanding persistent AF. There was no significant difference in rhythm on the preoperative electrocardiogram between groups. Demographic data were compared between those who underwent CMIV via median sternotomy and those who underwent CMIV via right minithoracotomy. Compared with patients who underwent median sternotomy, a higher proportion of right minithoracotomy patients had NYHA class III or IV symptoms (37/75 [49.3%] vs. 38/120 [31.7%], p = 0.016). However, right minithoracotomy patients had a higher average LV ejection fraction (56 ± 10 vs. 51 ± 13, p = 0.004). Furthermore, a higher number of median sternotomy patients had a prior stroke (4/75 [5%] vs. 19/120 [16%], p = 0.038). The substrate for atrial fibrillation, including the proportion of patients with paroxysmal, persistent or longstanding persistent AF, median AF duration, and incidence of failed catheter ablation, was not significantly different.

Table 1.

Preoperative demographic data; bold denotes p < 0.05, * denotes median with range.

| Variable | RMT (n = 75) | ST (n = 120) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 58 ± 10 | 58 ± 11 | 0.814 |

| Male gender, n (%) | 46 (61) | 90 (75) | 0.054 |

| AF duration, y* | 7 (3-11) | 5.6 (2.5-10) | 0.191 |

| Paroxysmal AF, n (%) | 26 (34.7) | 29 (24.2) | 0.141 |

| Persistent AF, n (%) | 4 (5.3) | 8 (6.7) | 0.770 |

| Long-standing persistent AF, n (%) | 45 (60.0) | 83 (69.2) | 0.216 |

| Immediate preoperative rhythm, n (%) | 0.357 | ||

| Atrial fibrillation | 31 (41.3) | 61 (50.8) | |

| Atrial flutter | 11 (14.7) | 12 (10.0) | |

| Normal sinus rhythm or sinus bradycardia | 30 (40.0) | 41 (34.2) | |

| Atrial artificial pacemaker | 1 (1.3) | 5 (4.2) | |

| Ventricular artificial pacemaker, no atrial activity | 2 (2.7) | 1 (0.8) | |

| NYHA class III or IV, n (%) | 37 (49.3) | 38 (31.7) | 0.016 |

| LVEF (%) | 56 ± 10 | 51 ± 13 | 0.004 |

| Failed catheter ablation, n (%) | 43 (57) | 59 (49) | 0.303 |

| Preoperative PM, n (%) | 8 (11) | 15 (13) | 0.821 |

| LA diameter (cm) | 5.0 ± 3.7 | 4.9 ± 1.0 | 0.817 |

| Chronic lung disease, n (%) | 9 (12) | 16 (13) | 0.830 |

| Peripheral vascular disease, n (%) | 6 (8) | 5 (4) | 0.341 |

| Stroke, n (%) | 4 (5) | 19 (16) | 0.038 |

| Renal failure, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Dialysis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

Abbreviations: y – years; n – number of patients; AF – atrial fibrillation; NYHA – New York Heart Association; LVEF – left ventricular ejection fraction; PM – pacemaker; LA – left atrial; RMT – right minithoracotomy; ST – sternotomy

Perioperative Results

Perioperative outcomes are summarized in Table 2. A box lesion was more commonly used in right minithoracotomy patients (73/75 [97%] vs. 100/120 [83%], p = 0.002). Perfusion and cross-clamp times were both longer with the minimally invasive approach (160 ± 27 vs. 124 ± 27 minutes and 64 ± 17 vs. 39 ± 13 minutes, respectively, p < 0.001). There were no differences in overall major complications or 30-day mortality; there was only one early death, in the sternotomy group. Median hospital length of stay was one day shorter in the right minithoracotomy group (7 [range 4-27] vs. 8 [range 4-53] days, p = 0.009). There was a lower rate of early ATAs in the right minithoracotomy group (28/75 [37%] vs. 64/120 [53%], p = 0.042); there was no difference in permanent pacemaker placement (4/75 [5%] vs. 10/120 [8%], p = 0.572).

Table 2.

Perioperative results. Bold denotes p < 0.05.

| Variable | RMT (n = 75) | ST (n = 120) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Box lesion, n (%) | 73 (97) | 100 (83) | 0.002 |

| Perfusion time (min) | 160 ± 27 | 124 ± 27 | <0.001 |

| Crossclamp time (min) | 64 ± 17 | 39 ± 13 | <0.001 |

| Early ATA, n (%) | 28 (37) | 64 (53) | 0.042 |

| Permanent PM, n (%) | 4 (5) | 10 (8) | 0.572 |

| Overall major complication, n (%) | 3 (4) | 7 (6) | 0.744 |

| Pneumonia, n (%) | 2 (3) | 5 (4) | 0.709 |

| Mediastinitis, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Intra-aortic balloon pump, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Permanent stroke, n (%) | 0 (0) | 2 (2) | 0.524 |

| Reoperation for bleeding, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1.000 |

| Renal failure requiring dialysis, n (%) | 1 (1) | 0 (0) | 0.385 |

| Median ICU LOS, d (range) | 2 (1-20) | 2 (1-36) | 0.397 |

| Median hospital LOS, d (range) | 7 (4-27) | 8 (4-53) | 0.009 |

| 30-d mortality, n (%) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) | 0.623 |

Abbreviations: n – number of patients; min – minutes; ATA – atrial tachyarrhythmia; PM – pacemaker; ICU – intensive care unit; LOS – length of stay; d – days; RMT – right minithoracotomy; ST – sternotomy

Follow-Up

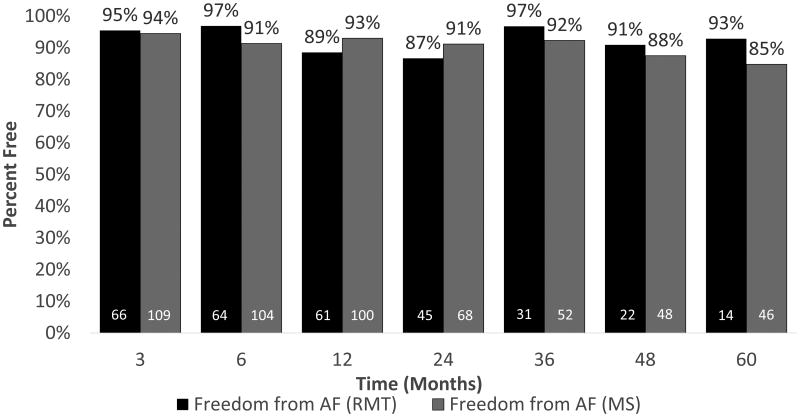

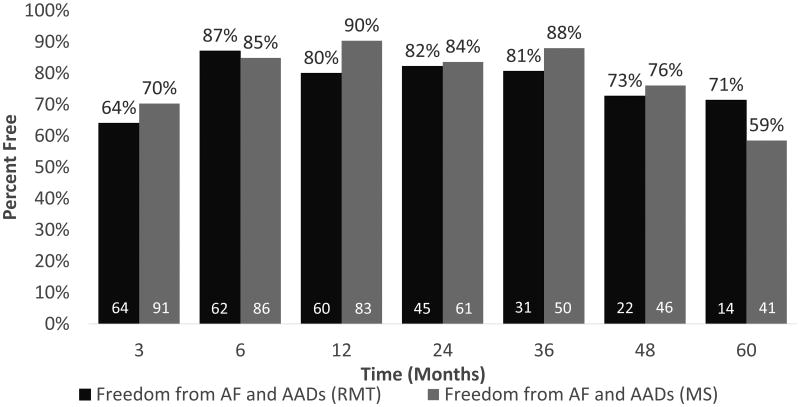

Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and antiarrhythmic drugs were not significantly different between groups at 1, 2, 3, 4 or 5 years. Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias is shown in Figure 2. As shown in Figure 3, excluding patients who did not receive complete isolation of the posterior left atrial wall, freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and antiarrhythmic drugs was 80% at one year in the right minithoracotomy group and 90% in the sternotomy group. Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and antiarrhythmic drugs at five years was 71% (10/14) in the right minithoracotomy group and 59% (24/41) in the median sternotomy group, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2.

Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias for right minithoracotomy (dark gray) and median sternotomy (light gray) by time point. White numbers denote number at risk.

Figure 3.

Freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and antiarrhythmic drugs for right minithoracotomy (dark gray) and median sternotomy (light gray) by time point. Patients who did not receive a box lesion are excluded. White numbers denote number at risk.

Multivariable analysis revealed that omission of the left atrial roof line, preoperative NYHA class III or IV symptoms, diabetes mellitus, and the presence of a preoperative pacemaker were significant risk factors for recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmias at 12 months, as shown in Table 1.

Discussion

The results of this study lend support to the concept that a minimally invasive approach to stand-alone surgical ablation for atrial fibrillation provides patients with a faster recovery while maintaining the efficacy of the traditional median sternotomy approach. There were no significant differences between groups in freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias or in freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and antiarrhythmic drugs at any time point. Although operative times were longer with the minimally invasive approach, this was not associated with higher rates of major complications or mortality.

This study adds to the literature supporting the efficacy of a modified Cox-Maze procedure using ablation devices. Weimar and colleagues from our group have previously shown the Cox-Maze IV employing bipolar radiofrequency clamps and cryoablation to have equivalent freedom from atrial fibrillation compared to the cut-and-sew Cox-Maze III procedure with a lower rate of major complications.7 Ad and colleagues have established the safety and efficacy of a stand-alone minimally invasive Cox-Maze procedure performed using cryothermal energy alone.8 The Cox-Maze IV procedure has also been shown to be effective in large cohorts of patients undergoing stand-alone and concomitant procedures.14

The present study also represents an important contribution to the body of literature showing the superiority of the full biatrial Cox-Maze lesion set over more limited lesion sets for stand-alone surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. In this series, omission of the left atrial roof line, leaving the left atrial posterior wall in electrical continuity with the anterior and superior left atrium, is associated with a significantly increased rate of atrial tachyarrhythmia recurrence. Many small series of totally epicardial and hybrid operations using varied lesion sets have been published in the medical literature over the past several years. This work has been summarized in a systematic review by Je and colleagues in 2015.15 After reviewing 37 studies including 1877 patients, they found that patients undergoing minimally invasive full Cox-Maze procedures had a significantly higher rate of freedom from atrial fibrillation at one year than those who underwent fully epicardial or hybrid procedures. In their review, a full Cox-Maze procedure also had important safety advantages over epicardial or hybrid procedures including lower rates of conversion to median sternotomy and reoperation for bleeding. Notably, results from our center were not included in the meta-analysis. The freedom from atrial tachyarrhythmias and complication rates in the present series were similar to those reported in that review.

This study has several limitations. First, this is a retrospective cohort study performed at a single institution, with the majority of cases performed by a single surgeon, introducing potential bias. Second, there is a possibility of temporal confounding. As our practice evolved, we have had less enthusiasm for the median sternotomy approach to stand-alone surgical ablation. The applicability of these results to surgeons starting new programs is limited, as the surgeons performing these cases were already proficient in surgical ablation prior to this case series. Third, some of the follow-up in this case series was not performed according to current reporting guidelines, and not all patients had prolonged monitoring at each follow-up time point.

In summary, this study showed a minimally invasive Cox-Maze IV procedure via a right minithoracotomy to be as effective as the Cox-Maze IV procedure via a traditional median sternotomy with a shorter hospital stay. These findings should encourage the broader adoption of a minimally invasive approach to stand-alone surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation using the full biatrial Cox-Maze lesion set.

Table 3.

Regression analysis of risk factors for recurrent atrial tachyarrhythmias. Only statistically significant risk factors listed.

| Variable | Odds Ratio | 95% CI Low | 95% CI High | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Omission of left atrial roof line | 10.74 | 2.17 | 58.66 | 0.004 |

| NYHA 3-4 Symptoms | 5.53 | 1.33 | 29.34 | 0.026 |

| Diabetes | 6.95 | 1.30 | 38.67 | 0.021 |

| Preoperative Pacemaker | 11.05 | 2.39 | 57.23 | 0.002 |

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants T32-HL-007776-21 and R01-HL-032257-32.

Disclosures:Matthew R. Schill, MD, received travel funding related to research supported by AtriCure, Inc., West Chester, OH USA. Richard B. Schuessler, PhD, received research funding from AtriCure, Inc., West Chester, OH USA. Ralph J. Damiano, Jr., MD, is a consultant for AtriCure, Inc., West Chester, OH USA, and Edwards Lifesciences Corp., Irvine, CA USA; he is on the speaker's bureau for LivaNova, Inc, London, UK.

Footnotes

Presented at the Annual Scientific Meeting of the International Society for Minimally Invasive Cardiothoracic Surgery, June 15 –18, 2016, Montreal, QC, Canada.

Laurie A. Sinn, RN, BSN, Jason W. Greenberg, BS, Matthew C. Henn, MD, Timothy S. Lancaster, MD, and Hersh S. Maniar, MD, declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Cox JL, Schuessler RB, D'Agostino HJ, Jr, et al. The surgical treatment of atrial fibrillation. III. Development of a definitive surgical procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1991;101:569–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ad N, Suri RM, Gammie JS, et al. Surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation trends and outcomes in North America. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;144:1051–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2012.07.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lall SC, Melby SJ, Voeller RK, et al. The effect of ablation technology on surgical outcomes after the Cox-maze procedure: a propensity analysis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;133:389–96. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2006.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mokadam NA, McCarthy PM, Gillinov AM, et al. A prospective multicenter trial of bipolar radiofrequency ablation for atrial fibrillation: early results. Ann Thorac Surg. 2004;78:1665–70. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2004.05.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lawrance CP, Henn MC, Miller JR, et al. A minimally invasive Cox maze IV procedure is as effective as sternotomy while decreasing major morbidity and hospital stay. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;148:955–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2014.05.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Calkins H, Kuck KH, Cappato R, et al. 2012 HRS/EHRA/ECAS expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: recommendations for patient selection, procedural techniques, patient management and follow-up, definitions, endpoints, and research trial design: a report of the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) Task Force on Catheter and Surgical Ablation of Atrial Fibrillation. Developed in partnership with the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society (ECAS); and in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). Endorsed by the governing bodies of the American College of Cardiology Foundation, the American Heart Association, the European Cardiac Arrhythmia Society, the European Heart Rhythm Association, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons, the Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society, and the Heart Rhythm Society. Heart Rhythm. 2012;9:632–96 e21. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2011.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weimar T, Schena S, Bailey MS, et al. The cox-maze procedure for lone atrial fibrillation: a single-center experience over 2 decades. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2012;5:8–14. doi: 10.1161/CIRCEP.111.963819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ad N, Henry L, Friehling T, et al. Minimally invasive stand-alone Cox-maze procedure for patients with nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Ann Thorac Surg. 2013;96:792–9. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2013.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Moten SC, Rodriguez E, Cook RC, et al. New ablation techniques for atrial fibrillation and the minimally invasive cryo-maze procedure in patients with lone atrial fibrillation. Heart Lung Circ. 2007;16(Suppl 3):S88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2007.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gaynor SL, Diodato MD, Prasad SM, et al. A prospective, single-center clinical trial of a modified Cox maze procedure with bipolar radiofrequency ablation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2004;128:535–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2004.02.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Robertson JO, Saint LL, Leidenfrost JE, et al. Illustrated techniques for performing the Cox-Maze IV procedure through a right mini-thoracotomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2014;3:105–16. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2225-319X.2013.12.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Voeller RK, Bailey MS, Zierer A, et al. Isolating the entire posterior left atrium improves surgical outcomes after the Cox maze procedure. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2008;135:870–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2007.10.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee AM, Clark K, Bailey MS, et al. A minimally invasive cox-maze procedure: operative technique and results. Innovations. 2010;5:281–6. doi: 10.1097/IMI.0b013e3181ee3815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henn MC, Lancaster TS, Miller JR, et al. Late outcomes after the Cox maze IV procedure for atrial fibrillation. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;150:1168–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2015.07.102. 78 e1-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Je HG, Shuman DJ, Ad N. A systematic review of minimally invasive surgical treatment for atrial fibrillation: a comparison of the Cox-Maze procedure, beating-heart epicardial ablation, and the hybrid procedure on safety and efficacy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:531–41. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezu536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]