Abstract

Anxiety disorders are associated with enhanced defensive reactivity to errors, measured via the error-related negativity (ERN). There is some evidence to suggest that problematic alcohol use is also associated with an enhanced ERN; although prior studies have been almost exclusively in men and have yet to examine the potential interactive effects of anxiety and alcohol abuse symptoms. The aim of the current study was to address the gaps in this literature by examining the unique and interactive effects of anxiety symptoms and problematic alcohol use on the ERN in a sample of 79 heterogeneous internalizing disorder patients. All participants completed a flanker task designed to robustly elicit the ERN and questionnaires assessing current internalizing symptoms and problematic alcohol use. As expected, results revealed that greater anxiety symptoms, but not depressive symptoms, were associated with a more enhanced ERN. There was no main effect of problematic alcohol use but there was a significant anxiety by problematic alcohol use interaction. At high anxiety symptoms, greater problematic alcohol use was associated with a more enhanced ERN; at low anxiety symptoms, alcohol use was unrelated to the ERN. There was no depression by alcohol abuse interaction. The findings suggest that within anxious individuals, heightened reactivity to errors/threat may be related to risk for alcohol abuse. The findings also converge with a broader literature suggesting that heightened reactivity to threat may be a shared vulnerability factor for anxiety and alcohol abuse and a novel prevention and intervention target for anxiety-alcohol abuse comorbidity.

Keywords: alcohol abuse, anxiety, error-related negativity, threat sensitivity, psychophysiology

1. Introduction

Anxiety disorders and alcohol use disorder (AUD) frequently co-occur. According to several, large-scale epidemiological studies, individuals with anxiety disorders are 2-4 times more likely to have a co-occurring AUD than the general population, and close to 25% of AUD patients seeking treatment have an anxiety disorder (Grant et al., 2004; Kessler et al., 1997; Kushner, Sher & Beitman, 1990). While each disorder in isolation is associated with serious adverse consequences (Stahre, Roeber, Kanny, Brewer, & Zhang, 2014; Stein et al., 2005), individuals with co-occurring anxiety and AUD evidence a markedly worse prognosis including increased rates of impairment, high rates of service utilization, and poor treatment outcomes (Kessler et al., 1997; Kushner et al., 2005). Despite the known deleterious effects of anxiety and AUD comorbidity, relatively little is known about the mechanisms underlying the relation between these disorders. In order to develop more effective prevention and intervention efforts, there is an urgent need to increase mechanistic understanding of anxiety-AUD comorbidity.

Converging lines of research indicate that anxiety disorders are characterized by an increased sensitivity to threat. Studies have shown that relative to healthy controls, individuals with anxiety disorders display an attentional bias towards threating information, inflated estimates of threat probability and harm, and increased defensive reactivity to aversive stimuli (Bar-Haim, Lamy, Pergamin, Bakermans-Kranenburg, & Van Ijzendoorn, 2007; Etkin & Wager, 2007; Foa, Franklin, Perry, & Herbert, 1996; Shankman et al., 2013). Several studies have also shown that increased sensitivity to threat precedes disorder onset (Meyer et al., 2015; Woud et al., 2014) and is evident in healthy individuals at-risk for anxiety disorders (Kujawa et al., 2015; Nelson et al., 2013; Nelson, Perlman, Hajcak, Klein, & Kotov, 2015). These findings together demonstrate that threat sensitivity is a key construct related to anxiety psychopathology.

One way individual differences in threat sensitivity are measured in the laboratory is via the error-related negativity (ERN) - a fronto-centrally maximal event-related potential (ERP) component that appears as a negative-going deflection in the waveform between 0 and 100ms following the commission of an error (Falkenstein, Hohnsbein, Hoormann, & Blanke, 1991; Gehring, Goss, Coles, Meyer, & Donchin, 1993). Errors are inherently aversive events as they signal the potential for harm and require corrective action (Hajcak & Foti, 2008; Hajcak, Moser, Yeung, & Simons, 2005). Studies have shown that the ERN is generated by the anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), a brain region implicated in several affective and motivational processes including threat detection, conflict monitoring, pain perception, and cognitive control (Debener et al., 2005; Reinhart & Woodman, 2014; Shackman et al., 2011). Several recent theories regarding the ACC suggest a fundamental role in integrating information about threats and punishment to guide goal-directed behavior (Holroyd & McClure, 2015; Shackman et al., 2011). From this perspective, the ERN reflects not only the detection of errors but also the signaling of the salience of errors in-order to guide behavior across contexts (Olvet & Hajcak, 2008; Weinberg et al., 2016). As would be expected, numerous studies have found that individuals with current anxiety disorders, and those with high trait anxiety, display an enhanced ERN compared with healthy controls (Hajcak, McDonald, & Simons, 2003; Weinberg, Olvet, & Hajcak, 2010; Kujawa et al., 2016; Meyer, Hajcak, Glenn, Kujawa, & Klein, 2016a). An enhanced ERN is also thought to distinguish anxiety from depression. Indeed, the majority of studies investigating the ERN and depression have found either no difference (Schrijvers et al., 2009) or a blunted ERN (Ladouceur et al., 2012; Ruchsow et al., 2004) when comparing adults with depression and controls.

There have also been a few studies suggesting that problematic alcohol use is associated with an enhanced ERN. For instance, Padilla et al. (2011) reported that males with remitted AUD, who were currently abstinent, exhibited larger ERNs compared with controls. A previous study by our lab found that veterans (primarily male) with a diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and current AUD had larger ERNs relative to veterans with PTSD without AUD (Gorka, MacNamara et al., 2016). In addition, Schellekens et al. (2010) investigated the ERN in three groups of male volunteers: healthy controls, abstinent individuals with AUD-only, and abstinent individuals with AUD and a comorbid anxiety disorder (i.e., panic disorder [PD], social anxiety disorder [SAD], or generalized anxiety disorder [GAD]). Findings indicated that those with AUD-only had a larger ERN compared with healthy controls. Moreover, individuals with AUD plus an anxiety disorder displayed an even larger ERN relative to both the AUD-only and control participants. Together, these studies indicate that individuals with current and remitted AUD display an enhanced ERN. They also suggest that anxiety and alcohol abuse may interact such that those with AUD and an anxiety disorder are particularly sensitive to threat/errors.

The studies reviewed above provide important initial evidence to suggest that heightened sensitivity to threat could reflect a shared vulnerability factor that drives AUD and anxiety comorbidity, and perhaps contributes to patterns of problematic alcohol use in anxious populations. However, only one prior study has examined the ERN in current drinkers, and that was in a sample of combat-exposed veterans, which raises concerns about the generalizability of findings to other samples (Gorka, MacNamara et al., 2016). There has also been only one study demonstrating an anxiety and AUD interaction (Schellekens et al., 2010) and in that study, it is unclear whether an enhanced ERN in the comorbid group was due to the presence of an anxiety disorder or reflects an interaction of anxiety and alcohol abuse symptoms as there was no anxiety only group for comparison. Related, all of the prior studies reviewed above have compared DSM-defined groups and it is unknown whether the same pattern of results is observed across anxiety and alcohol abuse symptom dimensions or is specific to discrete diagnoses. The question of generalization across symptom dimensions is a key topic within the field as there has been widespread recognition that categorically defined diagnoses fail to capture the full range of psychopathology and may obscure research findings (Kozak & Cuthbert, 2016; Insel et al., 2010).

The study was designed to address these gaps by examining the impact of anxiety symptoms and current problematic alcohol use on the ERN in a heterogeneous internalizing disorder patient sample. Adult volunteers completed a flanker task designed to robustly elicit the ERN and well-validated measures of current internalizing symptoms and levels of problematic alcohol use. We hypothesized that greater anxiety symptoms, but not depressive symptoms, would be associated with an enhanced ERN. We also hypothesized that greater problematic alcohol use would be associated with an enhanced ERN and that there would be an anxiety by alcohol use interaction such that at high anxiety symptoms, compared with low anxiety symptoms, greater problematic alcohol use would be associated with an enhanced ERN.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Participants

The sample was taken from a larger study focused on identifying biomarkers of treatment response across internalizing psychopathologies. The aims of the larger study therefore dictated the enrollment of a patient population with a full range of depression and anxiety who consented to treatment with pharmacotherapy (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors/SSRIs) or cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Participants were required to be between 18 and 65 and have a current full-threshold or sub-threshold DSM-5 depressive or anxiety disorder, report a total score of ≥23 on the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995a), and a Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) score of ≤ 60. Axis I diagnoses were assessed via the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-5 Disorders (SCID-5; American Psychiatric Association, 2013) by trained research staff. Exclusionary criteria included an inability to provide consent and read and write in English; major active medical or neurological problem; lifetime history of mania or psychosis; current obsessive-compulsive disorder; intellectual disability, or pervasive developmental disorder; any contraindication to receiving SSRIs; being already engaged in psychiatric treatment; psychoactive medication use within the past four months; history of traumatic brain injury; and being pregnant. This study was approved by the UIC Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

A total of 94 patients were enrolled in the study; however, eight were excluded due to missing or poor quality ERN data (i.e., less than six errors during the flanker task [Olvet & Hajcak, 2009] or excessive artifact) and seven were excluded due to missing self-report data. An additional two participants were found to be significant outliers on behavioral task performance (i.e., reaction time and task accuracy) and were also excluded. The final sample included 79 individuals. All data used in the current study were collected prior to treatment. All participants provided a negative breath test for alcohol and a negative urine screen for illicit drugs on the day of the evaluation. At the time of assessment no participant was taking psychoactive medication including SSRIs.

2.2 Internalizing Symptoms

Participants completed the DASS-21, which is a 21-item self-report questionnaire that includes three scales: depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms, and non-specific stress. The depression scale captures symptoms of dysphoria, hopelessness, self-deprecation and anhedonia; the anxiety scale measures automatic arousal, physical anxiety symptoms, situational anxiety, and subjective anxious affect; the stress scale assesses irritability, agitation, affective liability and nervous arousal (Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995b). Respondents are asked to indicate the extent to which each item applied to them within the past week using a 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied most of the time) Likert scale. The DASS-21 has been shown to have excellent convergent validity and reliability in patient populations (Antony et al., 1998). The DASS-21 also distinguishes between depressive and anxiety symptoms better than several other commonly used measures such as the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; see Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995b). The reliability of each of the scales was excellent in the current study (α = .82 - .93). All DASS-21 subscales were normally distributed (skew < 1.0).

2.3 Problematic Alcohol Use

Participants completed the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT; Babor et al., 1989) – a widely used self-report measure of problematic alcohol use developed by the World Health Organization (WHO). The AUDIT includes 10-items assessing alcohol consumption frequency (including binges), alcohol use problems, and dependence symptoms, and has been shown to be a sensitive measure of problematic drinking in diverse populations (Saunders et al., 1993a,b). In the current study, reliability of the measure was good (α=.74). Total scores were normally distributed (skew < 1.0).

2.4 Error Task

Participants completed a modified version of the original flanker task (Eriksen & Eriksen, 1974) to elicit the ERN. For each trial, participants viewed five horizontally aligned arrowheads. For half of the trials, arrows were compatible (“≫≫>” or “≪≪<”) and for the other half, the arrows were incompatible (“≫<≫” or “≪>≪”). Participants' were instructed to respond as quickly and as accurately as possible to indicate the direction of the center arrow (left or right) by pressing the appropriate mouse button. Stimuli were presented for 200ms, followed by a fixation cross. Participants were given up to 1800ms after the offset of the arrows to respond, followed by an intertrial interval (1000-2000ms) during which participants viewed a fixation cross.

The task consisted of 11 blocks of 30 trials (330 total trials), interspersed with self-timed breaks. To encourage fast and accurate responding, participants received performance-based feedback at the end of each block. If accuracy was ≤75%, the message “Please try to be more accurate” was presented; if accuracy was >90%, the message, “Please try to respond faster” was displayed; in all other cases, participants saw the message, “You're doing a great job”.

2.5 Data Recording

Continuous EEG was recorded during the task using an elastic cap and the ActiveTwo BioSemi system (BioSemi, Amsterdam, Netherlands). Thirty-four standard electrode sites were used and one electrode was placed on each mastoid. The EEG signal was pre-amplified at the electrode to improve the signal-to-noise ratio. The data were digitized at 24-bit resolution with a Least Significant Bit (LSB) value of 31.25nV and a sampling rate of 1024Hz, using a low-pass fifth order sinc filter with a -3dB cutoff point at 204.8Hz.

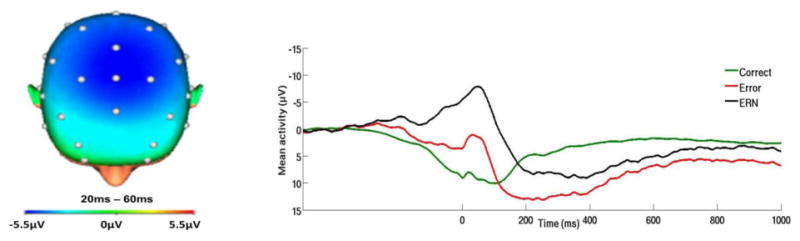

Off-line analyses were performed using Brain Vision Analyzer 2 software (Brain Products, Gilching, Germany). Data were re-referenced to the average of the two mastoids and high-pass (0.1Hz) and low-pass (30Hz) filtered. Standard eyeblink and ocular corrections were performed (Miller, Gratton & Yee,1988). Data were segmented beginning 500ms before each response onset and continuing for 1500ms. Standard artifact rejection procedures were used (see Gorka, MacNamara et al., 2016). Baseline correction for each trial was performed using the 500 to 300ms prior to response onset. Across subjects, ERN amplitude peaked at 42.3ms ±28.5 after responding. Therefore, in-order to capture this peak, the ERN and CRN (i.e., correct-response negatively) were scored as the average activity on error and correct trials, respectively, from 20 to 60ms after response at electrode FCz, where amplitude was maximal (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

On the left, topographic map of neural activity (error minus correct) across the entire sample. On the right, response-locked ERP waveform for correct and error trials, as well as the difference waves (error-related negativity; ΔERN) across the entire sample.

In addition to the individual ERN and CRN variables, we also calculated the ΔERN by subtracting the correct from error waveform and averaging activity 20-60ms post-response at FCz. The ΔERN is used to isolate activity unique to error processing (Simons, 2010), and has been extensively used in prior studies investigating the ERN (Jackson, Nelson, Meyer, & Hajcak, 2017; Kujawa et al., 2016). The ΔERN was therefore considered the primary dependent variable; however, secondary models were also run using the individual ERN and CRN variables to provide additional information regarding variations in activity to errors and correct trials.

As for task performance, accuracy data were computed as the percentage of correct trials. Reaction time was computed as the amount of time it took participants to respond from stimulus onset, separately for error and correct trials.

2.6 Data Analysis Plan

To test our hypotheses, we conducted hierarchical linear regression analyses with the ΔERN as the dependent variable. All continuous variables were mean centered prior to analysis. Given that the sample included both males and females, biological sex was included as a covariate and tested for interactions with all study variables. Biological sex was entered in Step 1. The main effects of DASS-anxiety and total AUDIT scores were entered in Step 2, and all two-way interactions were entered in Step 3. The DASS-anxiety by AUDIT by sex three-way interaction was entered in Step 4. A significant interaction was followed-up using a standard simple slopes approach (Aiken, West, & Reno, 1991). Specifically, the moderator was re-centered at 1 SD above the mean for “high symptoms” and 1 SD below the mean for “low symptoms.” Two new interaction terms were created and post-hoc additional follow-up linear regression models were run at high and low symptoms.

In order to test the specificity of the present findings to anxiety symptoms, we conducted additional hierarchical linear regression models with DASS-depression scores. The model and procedures were identical except DASS-anxiety was replaced with DASS-depression. We additionally ran all models with the ERN and CRN as separate dependent variables to better understand whether variations in the ERN, CRN, or both were contributing to significant results.

3. Results

3.1 Descriptives

Demographic and descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. Participants were primarily female, which differs from prior studies investigating the ERN and alcohol use (e.g., Schellekens et al., 2010). All participants had at least one current internalizing Axis I diagnosis, and 92% had a current anxiety disorder. Approximately 43% of participants reported at least one alcohol binge within the past 30-days (5+ drinks for men, 4+ drinks for women, in one sitting) and 25.3% of the sample had total AUDIT scores at or above the cut-off for problematic drinking (i.e., ≥8; Babor et al., 1989), which is similar to, or slightly above, expected rates of problematic drinking in an internalizing disorder patient sample (Wolitzky-Taylor et al., 2015). Participants did not endorse high levels of other forms of substance use.

Table 1.

Demographics and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Mean (SD; Range) or % (n = 79) |

|

|---|---|

| Demographics | |

| Age (years) | 27.6 (9.6; 18 - 58) |

| Sex (female) | 73.4% |

| Education (years) | 16.2 (3.2; 12-26) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Caucasian | 50.6% |

| African American | 10.1% |

| Hispanic | 19.0% |

| Asian | 12.7% |

| ‘Other’ | 7.6% |

| Diagnoses | |

| Current Major Depressive Disorder | 55.7% |

| Current Dysthymia | 3.8% |

| Current Generalized Anxiety Disorder | 67.1% |

| Current Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder | 12.7% |

| Current Social Anxiety Disorder | 63.3% |

| Current Panic Disorder | 26.6% |

| Current Specific Phobia | 11.4% |

| Any Current Anxiety Disorder | 92.4% |

| Flanker Task Variables | |

| CRN | 9.43 (6.4; -4.8 – 22.9) |

| ERN | 1.90 (8.3; -16.3 – 16.3) |

| ΔERN | -7.53 (5.9; -19.3 – 9.7) |

| Congruent Error RT (ms) | 289.47 (64.8; 201.0 – 578.3) |

| Congruent Correct RT (ms) | 356.70 (65.3; 276.3 – 740.2) |

| Incongruent Error RT (ms) | 304.25 (59.2; 239.0 – 633.0) |

| Incongruent Correct RT (ms) | 415.41 (63.6; 296.1 – 717.3) |

| Self-Report Variables | |

| Daily Cigarette Smoker | 3.8% |

| Used Cannabis in Past Six Months | 8.9% |

| Used Illicit Drugs* in Past Six Months | 2.5% |

| Binge Drank in Past Month | 43.0% |

| AUDIT Total Score | 4.8 (3.3; 0 - 16) |

| DASS-Anxiety | 8.5 (4.4; 1 -18) |

| DASS-Depression | 11.2 (5.6; 0 - 30) |

| DASS-Stress | 13.4 (3.8; 5 - 22) |

Note. ERN = error-related negativity; CRN = correct response negativity; ΔERN = ERN minus CRN; RT = reaction time. Illicit drugs were coded as any illegal substance other than cannabis.

With regard to behavioral performance during the flanker task, participants committed an average of 56.2±29.8 errors on incongruent trials and 31.0±41.9 errors on congruent trials. This corresponds to 83.0% and 90.6% accuracy for incongruent and congruent trials, respectively. Reaction times were faster for errors than for correct responses, t(78)=17.53, p<0.01. Task accuracy and RTs were not correlated with the study variables (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Pearson's correlations for all study variables.

| Variable | 1. | 2. | 3. | 4. | 5. | 6. | 7. | 8. | 9. | 10. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. DASS-Anxiety | 1.0 | |||||||||

| 2. DASS-Dep | -.21 | 1.0 | ||||||||

| 3. DASS-Stress | .30* | -.07 | 1.0 | |||||||

| 4. AUDIT | -.07 | -.13 | -.01 | 1.0 | ||||||

| 5. ERN | -.26* | .03 | -.20 | .02 | 1.0 | |||||

| 6. CRN | -.03 | .03 | -.11 | .04 | .71* | 1.0 | ||||

| 7. ΔERN | -.34* | <.01 | -.16 | -.01 | .64* | -.09 | 1.0 | |||

| 8. Task Accuracy | -.24 | .10 | -.21 | .05 | <.01 | .06 | -.08 | 1.0 | ||

| 9. Correct RT | -.19 | .15 | .12 | -.20 | -.15 | -.23 | .15 | .41* | 1.0 | |

| 10. Error RT | -.03 | .09 | -.01 | -.21 | -.06 | -.24 | .21 | .27* | .64* | 1.0 |

Note. ERN = error-related negativity standardized residual; CRN = correct response negativity standardized residual; ΔERN = ERN minus CRN; RT = reaction time; Dep = Depression. Task accuracy and reaction times are collapsed across congruent and incongruent trials.

3.2 Impact of Internalizing Symptoms and Problematic Alcohol Use

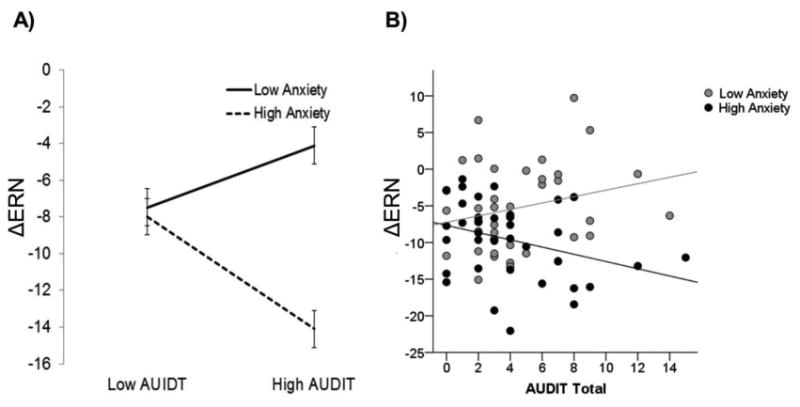

Results of all hierarchical linear regression models are presented in Table 3.With regard to the ΔERN, there was a main effect of DASS-anxiety such that greater anxiety symptoms were associated with a larger (more negative) ΔERN. There was no main effect of the AUDIT; however, there was a significant DASS-anxiety by AUDIT interaction. Follow-up analyses revealed that at high levels of anxiety symptoms, greater AUDIT scores were associated with a larger ΔERN, β= -.47, t = -2.58, p < 0.05 (see Figure 2). However, at low levels of anxiety symptoms, AUDIT scores were not related to the ΔERN, though there was a trend-level effect in the opposite direction - greater AUDIT scores associated with a more blunted ΔERN, β= 27, t = 1.71, p = 0.09. There were no two- or three-way interactions involving sex. There were also no main effects or interactions for the ΔERN depression model.

Table 3.

Hierarchical linear regression analyses examining the impact of internalizing and alcohol abuse symptoms on error-related negativity, correct-related negativity, and the difference score of the two measures.

| ERN | CRN | ΔERN | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| β | t | p | R2 | β | t | p | R2 | β | t | p | R2 | |

| Anxiety Model | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 | |||||||||

| Sex | -.02 | -.21 | .84 | .02 | .16 | .87 | -.05 | -.47 | .64 | |||

| Step 2 | .07 | <.01 | .11 | |||||||||

| DASS-Anxiety | -.27* | -2.41 | .02 | -.05 | -.43 | .67 | -.33* | -2.95 | <..01 | |||

| AUDIT Total | -.01 | -.10 | .92 | .04 | .29 | .77 | -.05 | -.48 | .63 | |||

| Step 3 | .11 | .02 | .18 | |||||||||

| DASS-Anxiety × AUDIT | -.24 | -1.48 | .14 | .09 | .57 | .51 | -.29* | -2.39 | .02 | |||

| Sex × AUDIT | -.08 | -.40 | .69 | -.11 | -.53 | .60 | <.01 | .04 | .97 | |||

| Sex × DASS-Anxiety | -.22 | -1.06 | .29 | -.17 | -.76 | .45 | -.13 | -.65 | .52 | |||

| Step 4 | .12 | .02 | .21 | |||||||||

| DASS-Anxiety × AUDIT × Sex | .19 | 1.10 | .27 | .04 | .20 | .85 | .23 | 1.39 | .18 | |||

| Depression Model | ||||||||||||

| Step 1 | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 | |||||||||

| Sex | -.03 | -.25 | .81 | .02 | .14 | .89 | -.06 | -.49 | .62 | |||

| Step 2 | <.01 | <.01 | <.01 | |||||||||

| DASS-Depression | .03 | .26 | .79 | .03 | .23 | .82 | .02 | .13 | .90 | |||

| AUDIT Total | .02 | .16 | .88 | .05 | .39 | .70 | -.02 | -.20 | .85 | |||

| Step 3 | .07 | .03 | .05 | |||||||||

| DASS-Depression × AUDIT | .20 | 1.47 | .15 | .13 | .96 | .34 | .14 | .99 | .33 | |||

| Sex × AUDIT | -.09 | -.51 | .61 | -.01 | -.03 | .98 | -.12 | -.67 | .51 | |||

| Sex × DASS-Depression | -.27 | -1.03 | .31 | -.14 | -.52 | .60 | -.23 | -.86 | .39 | |||

| Step 4 | .08 | .03 | .05 | |||||||||

| DASS-Depression × AUDIT × Sex | -.19 | -.87 | .39 | -.17 | -.78 | .44 | -.08 | -.36 | .72 | |||

Note.

p < .05;

DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Figure 2.

A) Graph illustrating the effect of problematic alcohol use on the ΔERN at high and low levels of anxiety symptoms (± 1 standard deviation from the mean). B) Scatter plot depicting the effect of problematic alcohol use on the ΔERN at high and low anxiety symptoms (median split). ΔERN = difference between error-related negativity and correct-related negativity; DASS = Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; AUDIT = Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test.

Follow-up analyses analyzing the ERN and CRN separately revealed that the main effect of DASS-anxiety was observed for the ERN but not the CRN (see Table 3). The DASS-anxiety by AUDIT interaction was trending towards significance for the ERN and was not significant for the CRN suggesting that the interaction was driven by the differentiation of activity during errors vs. correct trials. The separate ERN and CRN models did not indicate any novel findings beyond what was found for the ΔERN.

4. Discussion

Prior evidence indicates that both anxiety disorders and AUD are associated with increased threat sensitivity, measured via the ERN. The aim of the current study was to extend this work by examining the unique and interactive effects of anxiety and alcohol abuse symptoms, across a continuum, in an internalizing disorder patient sample. Results revealed that greater levels of anxiety symptoms, but not depressive symptoms, were associated with a more enhanced ΔERN. There was no main effect of problematic alcohol use but there was an anxiety by alcohol use interaction. In the context of high anxiety symptoms, greater levels of problematic drinking were associated with a more enhanced ΔERN. However, in the context of low anxiety symptoms, there was no relation between problematic alcohol use and the ΔERN. This pattern of results was notably specific to anxiety symptoms as there was no depression by problematic alcohol use interaction. These findings together suggest that anxiety and alcohol abuse interact and that increased threat sensitivity may characterize anxious individuals with a propensity towards alcohol abuse.

It is important to highlight that the present findings indicated a main effect of anxiety symptoms on the ΔERN, which follow-up analyses confirmed was driven by the association between anxiety and the ERN, not the CRN. The majority of prior research investigating the ERN and anxiety has been within clearly defined DSM groups (e.g., GAD, SAD) with limited comorbidities (Weinberg et al., 2010; Ruchsow et al., 2005). There have been a few studies looking at anxiety symptoms, rather than DSM disorders, that have found significant relationships with the ERN, but none with a highly comorbid, representative patient population (Weinberg et al., 2016). Thus, the present findings add to a growing literature supporting an association between anxiety and the ERN across diagnostic groups, and clinical and non-clinical samples. The results also indicate that prior ERN findings are generalizable to a highly comorbid, representative, treatment-seeking patient population. Given that the ERN has been shown to be moderately heritable (Anokhin et al., 2008), stable over time (Weinberg & Hajcak, 2011), and resistant to treatment effects (Kujawa et al., 2016), it may reflect an endophenotype for anxiety psychopathology (Olvet & Hajcak, 2008) and distinguish anxiety from depression.

Based on the few existing studies examining the ERN in individuals with a history of AUD, we expected that current levels of problematic alcohol use would also be associated with a larger ΔERN (e.g., Schellekens et al., 2010). This hypothesis was not supported but results did show that greater problematic alcohol use was associated with a larger ΔERN in the context of high anxiety symptoms, and this finding was driven by the differentiation of activity during errors vs. correct trials rather than the ERN or CRN individually. This interaction is notably consistent with the results of Schellekens et al. (2010), and our prior PTSD study (Gorka, MacNamara et al., 2016), in which anxiety and AUD comorbidity was associated with an exaggerated ERN. This finding also extends prior work by suggesting that an enhanced ERN within anxiety-AUD patients is related to an interaction between symptoms. An emerging theory is that within anxious individuals, those that are especially sensitive to threat may be motivated to consume alcohol to alleviate their distress, which is negatively reinforced promoting continued, excessive alcohol use. In support of this theory, several studies have demonstrated that acute alcohol intoxication dampens the ERN and alleviates reactivity to errors (Easdon, Izenberg, Armilio, Yu, & Alain, 2005; Ridderinkhof et al., 2002). Moreover, one study has specifically shown that alcohol dampens the ERN by reducing negative affect (Bartholow, Henry, Lust, Saults, & Wood, 2012). Thus, within anxious individuals, an exaggerated ERN may be an objective vulnerability factor for the onset and/or maintenance of problematic alcohol use.

The ERN is considered a measure of defensive reactivity to internal threat (i.e., errors) (Weinberg et al., 2015). Interestingly, the present findings converge with a parallel literature focused on defensive reactivity to external threat (i.e., threat-of-electric shock). In a series of papers, our laboratory has shown that anxiety disorders, and anxiety symptoms, are associated with an exaggerated reactivity to uncertain threat-of-shock, measured via startle eyeblink potentiation (Gorka, Lieberman, Shankman, & Phan, 2017; Lieberman, Gorka, Shankman, & Phan, 2016; Shankman et al., 2013). We have also shown in two separate samples that greater levels of problematic alcohol use are associated with an exaggerated startle response to uncertain threat (Gorka, Lieberman, Phan, & Shankman, 2016a), and that individuals with comorbid PD and alcohol dependence display greater startle to uncertain threat than individuals with PD-only (Gorka, Nelson, & Shankman, 2013). We have posited that increased sensitivity to threat may be a shared vulnerability factor for anxiety and problematic drinking as we have shown that startle potentiation to uncertain threat is related to familial risk for both classes of disorders (Nelson et al., 2013; Gorka et al., 2016b). The present findings help extend this theory to include sensitivity to internal and external threats. Notably, like the ERN studies, startle to uncertain threat is dampened during acute alcohol intoxication (Moberg & Curtin, 2009; Bradford, Shapiro, & Curtin, 2013), further highlighting that individuals who are particularly sensitive to threat may turn to alcohol as a means of avoidance-based coping and that exaggerated threat sensitivity may be one phenotype for anxiety-alcohol comorbidity.

At low levels of anxiety symptoms we did not find that problematic alcohol use is related to the ΔERN. In fact, we found a trend for the opposite such that greater problematic alcohol use was associated with a more blunted ΔERN. It is worth noting that there have been several studies and a recent systematic review suggesting that illicit substance use, and difficulties with impulse control, are associated with a blunted ERN and feedback error-related negativity (fERN) (see Luijten et al., 2014 for a review; Baker et al., 2011; Hall, Bernat, & Patrick, 2007; Luijten, van Meel, & Franken, 2011). For instance, findings indicate that cocaine and opiate-dependent individuals (Marhe, van de Wetering, & Franken, 2013; Forman et al., 2004), and adolescent offspring of parents with illicit substance use disorders (Euser, Evans, Greaves, Lord, Huizink, & Franken, 2013), display a reduced ERN and blunted ACC activity across a variety of cognitive tasks (e.g., Kaufman et al., 2003; Hester & Garavan, 2004). It has been suggested that a blunted ERN may be characteristic of an ‘externalizing’ phenotype susceptible to substance abuse (Hall et al., 2007; Santesso & Segalowitz, 2009); however, the existing alcohol literature has generally not corroborated this theory though one study by Smith and colleagues did find evidence for a blunted ERN in female heavy drinkers who also demonstrated impaired inhibitory control (Smith & Mattick, 2013). Based on the current findings, it is possible that there is a subgroup of problematic drinkers who display a blunted ERN and/or decreased threat sensitivity, particularly those with low levels of anxiety. However, there is also a separate subgroup of problematic drinkers who are hypersensitive to threat. Thus, a blunted response to threat and an exaggerated response to threat may reflect separate ‘externalizing’ and ‘internalizing’ phenotypes for AUD. Given that the current study included a sample of individuals with relatively high mean levels of anxiety symptoms, it is difficult to parse these two possibilities. Future studies should therefore directly test the possibility that individual differences in threat sensitivity could be one factor that captures risk for both internalizing and externalizing pathways to problem alcohol use.

The current study addressed several important gaps in the existing literature; however, there are limitations. Most notably, the sample was comprised of internalizing disorder patients presenting to treatment. Although this is a population for whom anxiety-alcohol comorbidity is particularly salient, it is unknown whether the present pattern of results generalizes to less severely anxious samples. Additional studies that include a wide range of anxiety and alcohol abuse symptoms are needed to ensure that these findings generalize across populations. Relatedly, given the nature of the sample, we were unable to examine differences in the ERN across DSM-defined groups and symptom dimensions. This was never the design of the current study but it may be useful for additional research to directly compare patterns of results across categories and dimensions.

The present findings indicate that within a heterogeneous clinical sample, greater anxiety symptoms are associated with greater threat sensitivity measured via the ERN. Finding also indicate that in the context of high anxiety symptoms, but not low anxiety symptoms, greater levels of problematic alcohol use are associated with an enhanced ERN. This suggests that within anxious individuals, heightened threat sensitivity may promote drinking behaviors as a means of dampening anxiety and distress. The findings also converge with a broader literature suggesting that heightened reactivity to threat may be a shared vulnerability factor for anxiety and AUD and perhaps, a novel prevention and intervention target for anxiety-AUD comorbidity.

Highlights.

In patients, greater anxiety symptoms relate to greater defensive reactivity

Problem drinking is also related to defensive reactivity at high anxiety symptoms

Defensive reactivity may underlie anxiety and alcohol abuse comorbidity

Heightened defensive reactivity may contribute to drinking behaviors

Acknowledgments

This study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health grant R01MH101497 (to KLP) and Center for Clinical and Translational Science (CCTS) UL1RR029879.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: Both authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Heath AC. Heritability of frontal brain function related to action monitoring. Psychophysiology. 2008;45(4):524–534. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00664.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antony MM, Bieling PJ, Cox BJ, Enns MW, Swinson RP. Psychometric properties of the 42-item and 21-item versions of the depression anxiety stress scales in clinical groups and a community sample. Psychological Assessment. 1998;10:176–181. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.10.2.176. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Babor TF, De La Fuente JR, Saunders J, Grant M. AUDIT: The Alcohol Use Identification Test Guidelines for use in primary healthcare. World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Baker TE, Stockwell T, Barnes G, Holroyd CB. Individual differences in substance dependence: at the intersection of brain, behaviour and cognition. Addiction Biology. 2011;16(3):458–466. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00243.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Haim Y, Lamy D, Pergamin L, Bakermans-Kranenburg MJ, Van Ijzendoorn MH. Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: a meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133(1):1–24. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartholow BD, Henry EA, Lust SA, Saults JS, Wood PK. Alcohol effects on performance monitoring and adjustment: affect modulation and impairment of evaluative cognitive control. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121(1):173–186. doi: 10.1037/a0023664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradford DE, Shapiro BL, Curtin JJ. How bad could it be? Alcohol dampens stress responses to threat of uncertain intensity. Psychological Science. 2013;24(12):2541–2549. doi: 10.1177/0956797613499923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Debener S, Ullsperger M, Siegel M, Fiehler K, Von Cramon DY, Engel AK. Trial-by-trial coupling of concurrent electroencephalogram and functional magnetic resonance imaging identifies the dynamics of performance monitoring. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2005;25(50):11730–11737. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3286-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Easdon C, Izenberg A, Armilio ML, Yu H, Alain C. Alcohol consumption impairs stimulus-and error-related processing during a Go/No-Go Task. Cognitive Brain Research. 2005;25(3):873–883. doi: 10.1016/j.cogbrainres.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eriksen BA, Eriksen CW. Effects of noise letters upon the identification of a target in a nonsearch task. Perception & Psychophysics. 1974;16:143–149. doi: 10.3758/BF03203267. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin A, Wager TD. Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: a meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1476–1488. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07030504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Euser AS, Evans BE, Greaves-Lord K, Huizink AC, Franken IH. Diminished error-related brain activity as a promising endophenotype for substance-use disorders: evidence from high-risk offspring. Addiction Biology. 2013;18(6):970–984. doi: 10.1111/adb.12002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein M, Hohnsbein J, Hoormann J, Blanke L. Effects of crossmodal divided attention on late ERP components. II. Error processing in choice reaction tasks. Electroencephalography and Clinical Neurophysiology. 1991;78(6):447–455. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(91)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa EB, Franklin ME, Perry KJ, Herbert JD. Cognitive biases in generalized social phobia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1996;105:433–439. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.105.3.433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forman SD, Dougherty GG, Casey BJ, Siegle GJ, Braver TS, Barch DM, Lorensen E. Opiate addicts lack error-dependent activation of rostral anterior cingulate. Biological Psychiatry. 2004;55(5):531–537. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gehring WJ, Goss B, Coles MGH, Meyer DE, Donchin E. A neural system for error detection and compensation. Psychological Science. 1993;4(6):385–390. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.1993.tb00586.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Lieberman L, Phan KL, Shankman SA. Association between problematic alcohol use and reactivity to uncertain threat in two independent samples. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2016a;164:89–96. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.04.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Lieberman L, Shankman SA, Phan KL. Startle potentiation to uncertain threat as a psychophysiological indicator of fear-based psychopathology: An examination across multiple internalizing disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2017;126(1):8–18. doi: 10.1037/abn0000233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Hee D, Lieberman L, Mittal VA, Phan KL, Shankman SA. Reactivity to uncertain threat as a familial vulnerability factor for alcohol use disorder. Psychological Medicine. 2016b:1–10. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, MacNamara A, Aase D, Proescher E, Greenstein JE, Walters R, Passi H, Babione JM, Levy DM, Kennedy AE, DiGangi JA, Rabinak C, Schroth C, Afshar K, Fitzgerald J, Hajcak G, Phan KL. Impact of alcohol use disorder comorbidity on defensive reactivity to errors in veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors. doi: 10.1037/adb0000196. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorka SM, Nelson BD, Shankman SA. Startle response to unpredictable threat in comorbid panic disorder and alcohol dependence. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;132(1):216–222. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Dawson DA, Chou SP, Dufour MC, Compton W, Kaplan K. Prevalence and co-occurrence of substance use disorders and independent mood and anxiety disorders: Results from the national epidemiologic survey on alcohol and relatedconditions. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61(8):807–816. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.8.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Foti D. Errors are aversive defensive motivation and the error-related negativity. Psychological Science. 2008;19(2):103–108. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02053.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, McDonald N, Simons RF. Anxiety and error-related brain activity. Biological Psychology. 2003;64(1):77–90. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0511(03)00103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hajcak G, Moser JS, Yeung N, Simons RF. On the ERN and the significance of errors. Psychophysiology. 2005;42(2):151–160. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2005.00270.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JR, Bernat EM, Patrick CJ. Externalizing psychopathology and the error-related negativity. Psychological Science. 2007;18(4):326–333. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hester R, Garavan H. Executive dysfunction in cocaine addiction: evidence for discordant frontal, cingulate, and cerebellar activity. Journal of Neuroscience. 2004;24(49):11017–11022. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3321-04.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holroyd CB, McClure SM. Hierarchical control over effortful behavior by rodent medial frontal cortex: A computational model. Psychological review. 2015;122(1):54–83. doi: 10.1037/a0038339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Insel T, Cuthbert B, Garvey M, Heinssen R, Pine DS, Quinn K, Sanislow C, Wang P. Research Domain Criteria (RDoC): Developing a valid diagnostic framework for research on mental disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;167:748–751. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09091379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson F, Nelson BD, Meyer A, Hajcak G. Pubertal development and anxiety risk independently relate to startle habituation during fear conditioning in 8–14 year-old females. Developmental Psychobiology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/dev.21506. e-pub ahead of press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman JN, Ross TJ, Stein EA, Garavan H. Cingulate hypoactivity in cocaine users during a GO-NOGO task as revealed by event-related functional magnetic resonance imaging. Journal of Neuroscience. 2003;23(21):7839–7843. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-21-07839.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Crum RM, Warner LA, Nelson CB, Schulenberg J, Anthony JC. Lifetime co-occurrence of DSM-III-R alcohol abuse and dependence with other psychiatric disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1997;54(4):313–321. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1997.01830160031005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozak MJ, Cuthbert BN. The NIMH research domain criteria initiative: Background, issues, and pragmatics. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(3):286–297. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Glenn CR, Hajcak G, Klein DN. Affective modulation of the startle response among children at high and low risk for anxiety disorders. Psychological Medicine. 2015;45(12):2647–2656. doi: 10.1017/S003329171500063X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujawa A, Weinberg A, Bunford N, Fitzgerald KD, Hanna GL, Monk CS, Phan KL. Error-related brain activity in youth and young adults before and after treatment for generalized or social anxiety disorder. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology and Biological Psychiatry. 2016;71:162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2016.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Abrams K, Thuras P, Hanson KL, Brekke M, Sletten S. Follow-up study of anxiety disorder and alcohol dependence in comorbid alcoholism treatment patients. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2005;29(8):1432–1443. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000175072.17623.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushner MG, Sher KJ, Beitman BD. The relation between alcohol problems and anxiety disorders. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1990;147:685–695. doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.6.685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur CD, Slifka JS, Dahl RE, Birmaher B, Axelson DA, Ryan ND. Altered error-related brain activity in youth with major depression. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience. 2012;2(3):351–362. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2012.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieberman L, Gorka SM, Shankman SA, Phan KL. Impact of panic on psychophysiological and neural reactivity to unpredictable threat in depression and anxiety. Clinical Psychological Science. 2016 doi: 10.1177/2167702616666507. 2167702616666507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond SH, Lovibond PF. Manual for the depression anxiety stress scales. Sydney, Australia: Psychology Foundation of Australia; 1995a. [Google Scholar]

- Lovibond PF, Lovibond SH. The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 1995b;33:335–343. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijten M, Machielsen MW, Veltman DJ, Hester R, Haan LD, Franken IH. Systematic review of ERP and fMRI studies investigating inhibitory control and error processing in people with substance dependence and behavioural addictions. Journal of Psychiatry & Neuroscience. 2014;39:149–169. doi: 10.1503/jpn.130052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luijten M, van Meel CS, Franken IH. Diminished error processing in smokers during smoking cue exposure. Pharmacology Biochemistry and Behavior. 2011;97(3):514–520. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marhe R, van de Wetering BJ, Franken IH. Error-related brain activity predicts cocaine use after treatment at 3-month follow-up. Biological Psychiatry. 2013;73(8):782–788. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Hajcak G, Glenn CR, Kujawa AJ, Klein DN. Error-Related brain activity is related to aversive potentiation of the startle response in children, but only the ERN is associated with anxiety disorders. Emotion. 2016a doi: 10.1037/emo0000243. e-pub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Hajcak G, Torpey-Newman DC, Kujawa A, Klein DN. Enhanced error-related brain activity in children predicts the onset of anxiety disorders between the ages of 6 and 9. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2015;124(2):266–274. doi: 10.1037/abn0000044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer A, Bress JN, Hajcak G, Gibb BE. Maternal depression is related to reduced error-related brain activity in child and adolescent offspring. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2016b;8:1–12. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016.1138405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Gratton G, Yee CM. Generalized implementation of an eye movement correction procedure. Psychophysiology. 1988;25:241–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.1988.tb00999.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moberg CA, Curtin JJ. Alcohol selectively reduces anxiety but not fear: startle response during unpredictable versus predictable threat. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2009;118(2):335. doi: 10.1037/a0015636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BD, McGowan SK, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Altman SE, Campbell ML, Shankman SA. Biomarkers of threat and reward sensitivity demonstrate unique associations with risk for psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(3):662–671. doi: 10.1037/a0033982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson BD, Perlman G, Hajcak G, Klein DN, Kotov R. Familial risk for distress and fear disorders and emotional reactivity in adolescence: An event-related potential investigation. Psychological medicine. 2015;45(12):2545–2556. doi: 10.1017/S0033291715000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Hajcak G. The error-related negativity (ERN) and psychopathology: toward an endophenotype. Clinical Psychology Review. 2008;28(8):1343–1354. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olvet DM, Hajcak G. The effect of trial-to-trial feedback on the error-related negativity and its relationship with anxiety. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience. 2009;9(4):427–433. doi: 10.3758/CABN.9.4.427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padilla ML, Colrain IM, Sullivan EV, Mayer BZ, Turlington SR, Hoffman LR, Pfefferbaum A. Electrophysiological evidence of enhanced performance monitoring in recently abstinent alcoholic men. Psychopharmacology. 2011;213(1):81–91. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-2018-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhart RM, Woodman GF. Causal control of medial–frontal cortex governs electrophysiological and behavioral indices of performance monitoring and learning. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(12):4214–4227. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5421-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridderinkhof KR, de Vlugt Y, Bramlage A, Spaan M, Elton M, Snel J, Band GP. Alcohol consumption impairs detection of performance errors in mediofrontal cortex. Science. 2002;298(5601):2209–2211. doi: 10.1126/science.1076929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchsow M, Grön G, Reuter K, Spitzer M, Hermle L, Kiefer M. Error-related brain activity in patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder and in healthy controls. Journal of Psychophysiology. 2005;19(4):298–304. doi: 10.1027/0269-8803.19.4.298. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ruchsow M, Herrnberger B, Wiesend C, Grön G, Spitzer M, Kiefer M. The effect of erroneous responses on response monitoring in patients with major depressive disorder: A study with event-related potentials. Psychophysiology. 2004;41(6):833–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2004.00237.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santesso DL, Segalowitz SJ. The error-related negativity is related to risk taking and empathy in young men. Psychophysiology. 2009;46(1):143–152. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2008.00714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Amundsen A, Grant M. Alcohol consumption and related problems among primary health care patients: WHO Collaborative Project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption I. Addiction. 1993a;88:349–362. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb00822.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders JB, Aasland OG, Babor TF, de la Fuente JR, Grant M. Development of the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT): WHO collaborative project on early detection of persons with harmful alcohol consumption II. Addiction. 1993b;88:791–804. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02093.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellekens AF, De Bruijn ER, Van Lankveld CA, Hulstijn W, Buitelaar JK, De Jong CA, Verkes RJ. Alcohol dependence and anxiety increase error-related brain activity. Addiction. 2010;105(11):1928–1934. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schrijvers D, De Bruijn ER, Maas YJ, Vancoillie P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe BG. Action monitoring and depressive symptom reduction in major depressive disorder. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2009;71(3):218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shackman AJ, Salomons TV, Slagter HA, Fox AS, Winter JJ, Davidson RJ. The integration of negative affect, pain and cognitive control in the cingulate cortex. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2011;12(3):154–167. doi: 10.1038/nrn2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shankman SA, Nelson BD, Sarapas C, Robison-Andrew EJ, Campbell ML, Altman SE, Gorka SM. A psychophysiological investigation of threat and reward sensitivity in individuals with panic disorder and/or major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2013;122(2):322–338. doi: 10.1037/a0030747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons RF. The way of our errors: theme and variations. Psychophysiology. 2010;47(1):1–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8986.2009.00929.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith JL, Mattick RP. Evidence of deficits in behavioural inhibition and performance monitoring in young female heavy drinkers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2013;133(2):398–404. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stahre M, Roeber J, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Zhang X. Contribution of excessive alcohol consumption to deaths and years of potential life lost in the United States. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2014;11:130293. doi: 10.5888/pcd11.130293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein MB, Roy-Byrne PP, Craske MG, Bystritsky A, Sullivan G, Pyne JM, Sherbourne CD. Functional impact and health utility of anxiety disorders in primary care outpatients. Medical Care. 2005;43(12):1164–1170. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000185750.18119.fd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Dieterich R, Riesel A. Error-related brain activity in the age of RDoC: a review of the literature. International Journal of Psychophysiology. 2015;98(2):276–299. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2015.02.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Hajcak G. Longer term test–retest reliability of error-related brain activity. Psychophysiology. 2011;48(10):1420–1425. doi: 10.1111/j.14698986.2011.01206.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Meyer A, Hale-Rude E, Perlman G, Kotov R, Klein DN, Hajcak G. Error-related negativity (ERN) and sustained threat: Conceptual framework and empirical evaluation in an adolescent sample. Psychophysiology. 2016;53(3):372–385. doi: 10.1111/psyp.12538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg A, Olvet DM, Hajcak G. Increased error-related brain activity in generalized anxiety disorder. Biological Psychology. 2010;85(3):472–480. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.09.01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolitzky-Taylor K, Brown LA, Roy-Byrne P, Sherbourne C, Stein MB, Sullivan G, Craske MG. The impact of alcohol use severity on anxiety treatment outcomes in a large effectiveness trial in primary care. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2015;30:88–93. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.12.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woud ML, Zhang XC, Becker ES, McNally RJ, Margraf J. Don't panic: Interpretation bias is predictive of new onsets of panic disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders. 2014;28(1):83–87. doi: 10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.11.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]