Abstract

Our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, have a complex demographic history. We have analyzed the high-coverage whole genomes of 75 wild-born chimpanzees and bonobos from ten countries in Africa. We find that chimpanzee population sub-structure makes genetic information a good predictor of geographic origin at country and regional scales. Most strikingly, multiple lines of evidence suggest that gene flow occurred from bonobos into the ancestors of central and eastern chimpanzees between 200 and 550 thousand years ago (Kya), probably with subsequent spread into Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees. Together with another possibly more recent contact (after 200 Kya), bonobos contributed less than 1% to the central chimpanzee genomes. Admixture thus appears to have been widespread during hominid evolution.

Main Text

Compared to our knowledge of the origins and population history of humans, much less is known about the extant species closest to humans, chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) and bonobos (Pan paniscus). Unraveling the demographic histories of our closest living relatives provides an opportunity for comparisons with our own history, and thus for studying processes that might have played a recurring role in hominid evolution. Due to a paucity of fossil records (1), our understanding of the demographic history of the Pan clade has primarily relied on population genetic data from mitochondrial genomes (2,3), nuclear fragments (4,5), and microsatellites (6,7). More recently, the analysis of whole-genome sequences from chimpanzees and bonobos hinted at a complex evolutionary history for the four taxonomically recognized chimpanzee subspecies (8). However, although chimpanzees and bonobos hybridize in captivity (9), the extent of interbreeding among chimpanzee subspecies and between chimpanzees and bonobos in the wild remains unclear.

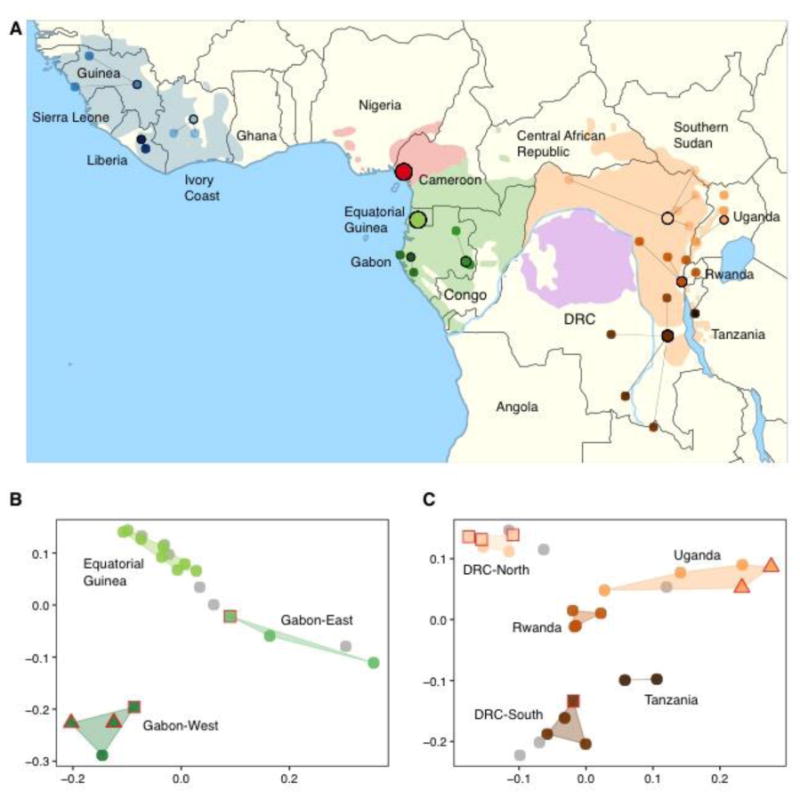

We analyzed 75 complete genomes from the Pan clade, of which 40 were sequenced for this project to a mean sequence coverage of 25-fold. Our samples span ten African countries, from the westernmost to easternmost regions of the chimpanzee range (Fig. 1A). We discover 32% more variable sites than previously identified (8,10), highlighting the value of our sampling scheme. Different analyses suggest larger historical effective population sizes in central chimpanzees, including haplotype diversity in each subspecies (Fig. S5), Y chromosome diversity (Fig. S3), FST-based phylogenies (Fig. S16) and genome-wide linkage disequilibrium (Fig S6). An analysis of the long-term demographic history using PSMC (11) (Fig. S17), and a composite-likelihood modelling approach performed to fit the observed joint site frequency spectrum (SFS) (12) infer a high long-term population size in central chimpanzees (10). The apportionment of genetic diversity among Pan populations reveals that central chimpanzees retain the largest diversity in the chimpanzee lineage, while the western, Nigeria-Cameroon and eastern subspecies harbor signals of population bottlenecks (Fig. S7).

Figure 1. Chimpanzee geography and genetic substructure.

(A) Geographic distribution of Pan populations. Reported coordinates for individuals are shown as circles colored by broad region of origin. Grouping is based on prior information on geographical origin (Table S1), connected by lines to clustered locations within the current range of subspecies. No further coordinates were available for Equatorial Guinea and Nigeria-Cameroon. (B & C) PCA plot of chromosome 21 SNP data for central (B) and eastern (C) chimpanzees. PCA coordinates modified by Procrustes transformation. Samples with unknown origin colored in gray. Squares: Low coverage genomes. Triangles: Chromosome 21 captured from fecal samples. These GPS labelled samples cluster within the range of regional genetic variation reported in whole-genome sampling.

We explored chimpanzee population structure to determine the extent to which genetic information can predict geographic origin. This is important because determining the geographical origin of confiscated individuals can help to localize hotspots of poaching activity (13). Both PCA and population clustering analyses reveal local stratification most strongly in central and eastern chimpanzees (Fig. 1B, 1C), but less so in western chimpanzees (10). Although we could not include enough geolocalized samples to assess fine-scale population structure in Nigeria-Cameroon and western chimpanzees, we expect similar stratification with broader sampling. To test the accuracy of our current predictions, we produced low-coverage whole-genome sequences for six additional individuals whose geographical origins were known (Table S1) and sequenced chromosome 21 from four fecal GPS-labeled samples, all from central and eastern chimpanzees (10). The genetic predictions are accurate to a level of country and region within a country (Fig. 1B, C). In the future, probably the origins of confiscated chimpanzees of unknown origin will be discernible with sufficient data from reference populations, with implications for the in-situ and ex-situ management of this species.

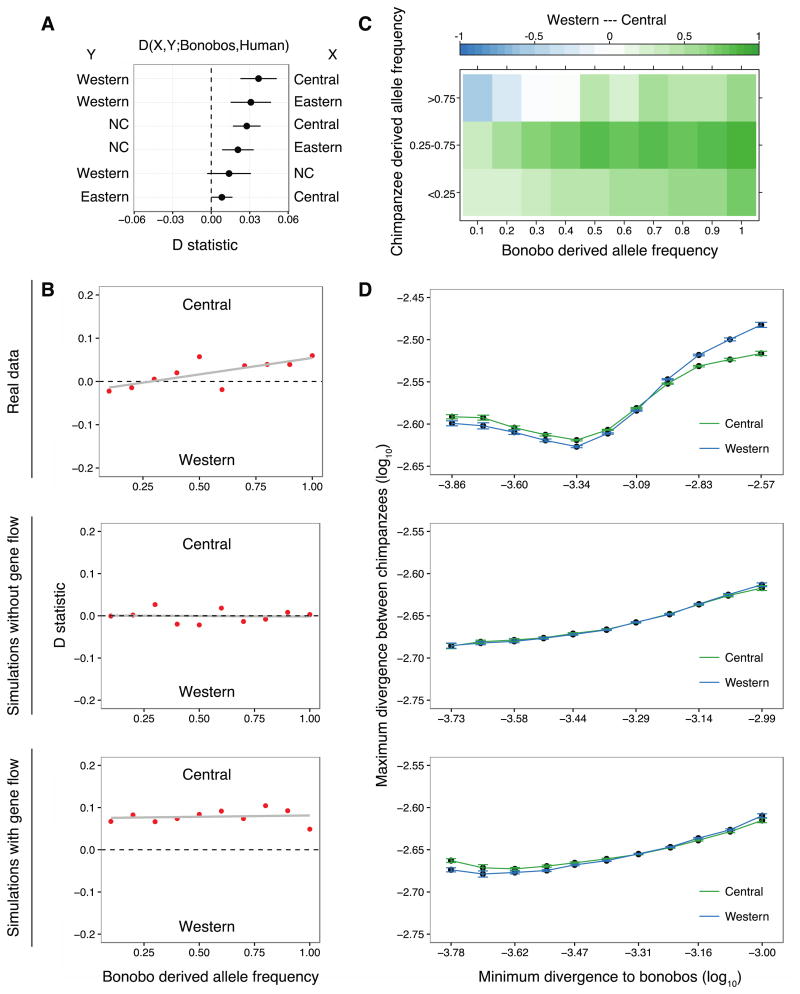

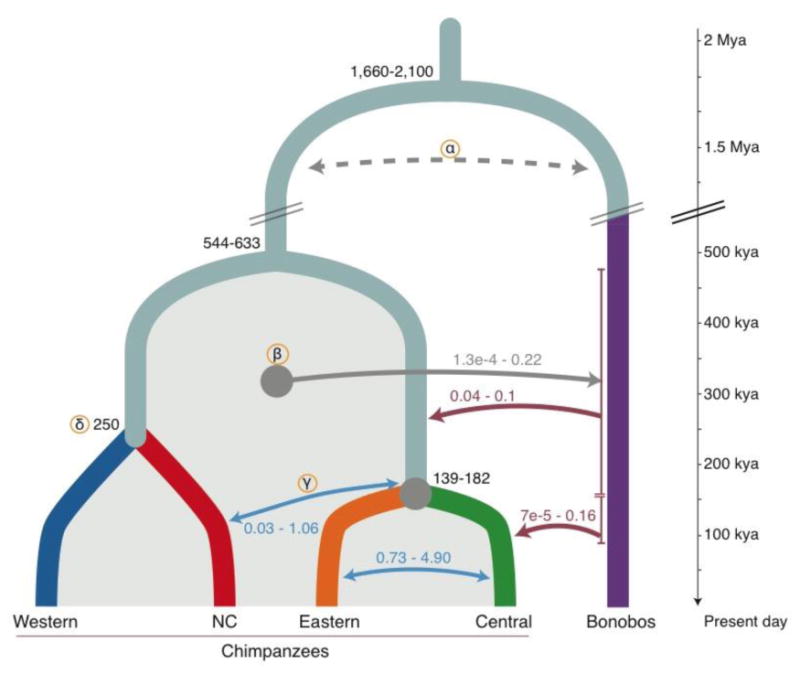

Since multiple events of gene flow between modern and archaic humans have been described (14–17), we explored similar evidence of admixture within the Pan clade. In our SFS-based demographic model, we found support for gene flow among chimpanzee subspecies embedded in an improved picture of the complex population history (10,12). Previously, gene flow between chimpanzees and bonobos was not supported in analyses of low-coverage genomes (18). However, here we find that central, eastern and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees share significantly more derived alleles with bonobos than western chimpanzees do (Figs. 2A, S26). Although an excess of derived allele sharing has been reported previously, it was attributed to greater genetic drift in the western subspecies (6,19), or described as inconclusive due to insufficient sampling (20), but using high-coverage data from more individuals allows to investigate the possibility of migration. Since the chance of derived alleles to be introduced through gene flow from bonobos into chimpanzees increases with the frequency in the donor population, alleles at high frequencies are expected to exhibit greater sharing (15,17). Indeed, derived alleles at high frequency in bonobos are disproportionally shared with central, compared to western, chimpanzees (Figs. 2B, S28). Since we used sites with high sequence coverage, we exclude contamination as a potential source of unequal allele sharing. Furthermore, gene flow should introduce bonobo alleles into chimpanzee populations at low frequency. We find that these shared derived alleles do indeed segregate at low and moderate frequencies in the non-western chimpanzee populations (Figs. 2C, S30). This observation thus suggests ancient low-level gene flow from bonobos, with a minority of introgressed alleles drifting to moderate frequencies after segregating in the chimpanzee populations, a scenario which is supported by the demographic model particularly into the ancestor of central and eastern chimpanzees (Fig. 3). An alternative explanation for such shared ancestry through incomplete lineage sorting would predict such alleles to drift towards fixation after their separation (10).

Figure 2. Genome-wide statistics support gene flow between chimpanzees and bonobos.

(A). Population-wise D-statistic of the form D(X, Y; Bonobos, Human). Non-western chimpanzees share more derived alleles with bonobos than western chimpanzees. (B) Western and central chimpanzee allele sharing with bonobos binned by derived allele frequency in bonobos (Dj); bonobo alleles are more often shared with central chimpanzees across bonobo frequencies. Real data (top panel); simulations without gene flow (middle); simulations of a model with gene flow into non-western chimpanzees (bottom). (C) Western and central chimpanzee allele sharing with bonobos stratified by both bonobo and chimpanzee derived allele frequency (Djx), calculated at a given frequency in bonobos and at least one of the chimpanzee subspecies (color gradient representing the extent of sharing). (D) Divergence between chimpanzee subspecies versus minimum divergence to bonobos at sites with bonobo derived allele frequency ≥90% in windows of 50 Kbp. Error bars represent 95% confidence intervals from 500 bootstrap replicates. Segments with low divergence to bonobos in the genomes of central chimpanzees show high divergence to western chimpanzees. Real data (top), simulated data without gene flow (middle) and with gene flow (bottom).

Figure 3. Conceptual model of a complex population history.

SFS-based modeling infers several contacts between chimpanzees and bonobos after their divergence. Split times (Kya) and migration rates correspond to 95% confidence intervals (CI) obtained with the demographic model with western, central and eastern chimpanzees (10). Quantification of gene flow as migration rates scaled by the effective size (2Nm). Red arrows: gene flow from bonobos into chimpanzees. The ancestral population of central and eastern chimpanzees received the highest amount of bonobo alleles, while central chimpanzees received additional, more recent gene flow (<200 Kya). Blue arrows: Highest inferred migrations within chimpanzee subspecies; intense gene flow between central and eastern chimpanzees. (α) Dotted line: Putative ancient gene flow between the ancestors of all chimpanzees and bonobos is inferred by the model. (β) More recent gene flow from chimpanzees into bonobos is inferred. Shaded area: Range of estimates across all chimpanzee populations. (γ) Inferred admixture between Nigeria-Cameroon and central/eastern chimpanzees; indirect gene flow from bonobos into Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees might have occurred through these contacts. (δ) Divergence time between western and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees is estimated by using MSMC2 (10).

If bonobos contributed alleles to chimpanzees, these should be recognizable as introgressed segments in chimpanzees, i.e. regions with unusually low divergence to bonobos and unusually high heterozygosity. Following an approach used to identify gene flow from modern humans into Neandertals (17), we calculated the divergence from bonobos to the chimpanzee alleles that result in the minimum divergence to derived alleles at high frequency (≥90%) in sequence windows of 50 Kbp (10), and compared it to the maximum divergence between chimpanzee subspecies. Genomic regions in the non-western chimpanzees were least divergent to bonobos and more divergent to western chimpanzees than western chimpanzees are to non-western chimpanzees (Figs. 2D, S36), and these also showed an increase in heterozygosity (Fig. S37).

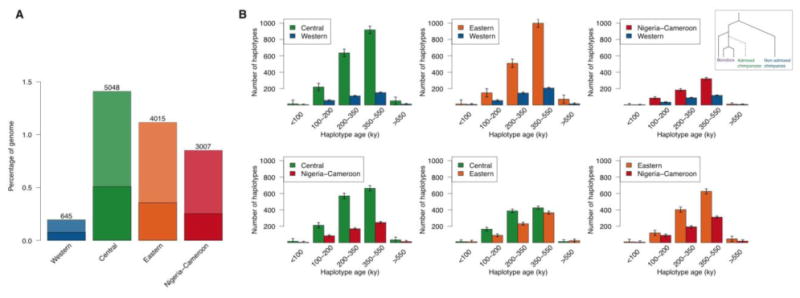

We identified discrete putatively introgressed regions in the individual genomes harboring heterozygous bonobo-like and chimpanzee haplotypes (17). We detect almost an order of magnitude more of such haplotypes in central chimpanzees than in western chimpanzees, spanning a total of ∼2.4% across the genomes of ten individuals, while the amount is smaller in eastern and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees (Fig. 4A, Table S6). Furthermore, central chimpanzees carry an excess of haplotypes which do not overlap with any of the other subspecies (P < 0.01, G-test). These regions also show a significant depletion in background selection (21) (P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank test), suggesting that bonobo alleles might have been disadvantageous in a chimpanzee genetic background (10). This observation, together with the X chromosome not carrying more derived alleles shared between bonobos and non-western chimpanzees (Fig. S31), resembles patterns in modern and archaic human genomes (16,22,23).

Figure 4. Introgressed segments and inferred age of introgressed haplotypes.

(A) Numbers of putatively introgressed segments in heterozygosity per population, and proportion of the chimpanzee genome. Dark bars represent segments uniquely found in each population, grey bars simulations without gene flow. (B) Age distribution of bonobo-like haplotypes in chimpanzee populations as estimated by ARGweaver. Chimpanzee subspecies are compared pairwise, and bonobo-like haplotypes are defined as regions of at least 50 Kbp that coalesce within the bonobo subtree before coalescing with the other chimpanzee population (inset). Error bars represent 95% confidence across MCMC replicates (10).

Further support for a scenario of gene flow between chimpanzees and bonobos is provided by a model-based inference with TreeMix (24) (Fig. S24), and the SFS-based demographic models described above (10), which have significantly higher likelihoods when the models include multiple gene flow events between species (Figs. S50, S52). The best-fitting models infer a complex admixture history, including low-level gene flow from bonobos to central chimpanzees, the ancestors of central and eastern chimpanzees, as well as from chimpanzees into bonobos (Figs. 3, S51, S54).

We used simulations to test whether these differential allele sharing patterns would be expected in the absence or presence of gene flow under the demographic history inferred by our models (10). Only a scenario including gene flow reproduced stratified D-statistics different from zero (Fig. S33), and even substantial genetic drift in the western subspecies could not explain the asymmetries in shared derived alleles with bonobos (Fig. S34, S35). Additionally, only models with gene flow from bonobos into the ancestors of central and eastern chimpanzees, and to a lesser extent into Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees, reproduced the observed patterns in sequence windows (Figs. 2D, S38-S43), and heterozygous regions (Fig. S45). In sum, the unequal allele and haplotype sharing is unlikely to result from alternative demographic models without gene flow from bonobos into chimpanzee populations. Although alternative models – e.g. different gene flow events or differences in population size – may explain some features of the data, none of those tested here could reproduce all features of the data (10).

Finally, if gene flow occurred between the Pan species after their separation 1.5-2.1 million years ago (Fig. 3), haplotypes younger than this should be shared among them. Using ARGweaver (25), we estimated the age of haplotypes for which one chimpanzee subspecies coalesces within the subtree of bonobos more recently than with another chimpanzee subspecies (10). A fraction of these haplotypes may result from incomplete lineage sorting, but it has been shown that gene flow introduces an excess of young haplotypes into the receiving population (17). We found that central chimpanzees carry 4.4-fold more bonobo-like haplotypes than western chimpanzees, and these are longer (P < 0.01, Wilcoxon rank test), while eastern and Nigeria-Cameroon chimpanzees smaller amounts (Table S10). These haplotypes are inferred to coalesce 200 to 550 Kya, consistent with gene flow from bonobos into the ancestors of central and eastern chimpanzees less than 650 Kya (Fig. 3, 4B). The smaller amount of such haplotypes in Nigeria-Cameroon and western chimpanzees might result from subsequent gene flow between chimpanzee populations. Additionally, central chimpanzees carry a slightly larger proportion of younger haplotypes (100 to 200 Kya), supporting another, more recent phase of secondary contact between chimpanzees and bonobos. These estimates agree with the phases of gene flow before and after the split of central and eastern chimpanzees (< 180 Kya) inferred by our demographic model (Fig. 3), and the excess of bonobo-like alleles and haplotypes in central chimpanzees. These methods estimate the overall contribution to individual genomes to less than 1% (10).

Through the analysis of multiple high-coverage genomes we were able to reconstruct a complex history of admixture within the Pan clade. It appears that there was gene flow from an ancestral bonobo population into non-western chimpanzees several hundred thousand years ago. Although we cannot distinguish whether the gene flow occurred at low levels over a long time or in discrete pulses, it seems likely that at least two phases of secondary contact between the two species took place. This study reveals that our closest living relatives experienced a history of admixture similar to that within the Homo clade. Thus, gene flow might have been widespread during the evolution of the great apes and hominins.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

All sequence data have been submitted to the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA) and are available under the following accession: PRJEB15083. We greatly appreciate all the sample providers: Centre de Conservation pour Chimpanzés (CCC), Chimfunshi Wildlife Orphanage Trust, Centre de Primatologie; Centre International de Recherches Médicales de Franceville, Jeunes Animaux Confisqués Au Katanga (J.A.C.K.), Ngamba Island Chimpanzee Sanctuary, Sweetwaters Chimpanzee Sanctuary, Stichting AAP, Bioparc Valencia, Edinburgh Zoo, Furuviksparken, Kolmårdens Djurpark, Zoo de Barcelona, Parc le Pal, Zoo Aquarium de Madrid, Zoo Parc de Beauval and Zoo Zürich. We respectfully thank the Agence Nationale des Parcs Nationaux, Gabon, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CENAREST), Gabon, Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST) and the Ugandan Wildlife Authority (UWA) for permission for collecting fecal samples in Gabon and Uganda. We particularly thank K. Prüfer for advices on technical aspects; M. Meyer and A. Weihmann for helping with the capture of fecal samples; M. J. Hubisz for advice on ARGweaver; KJ. Bertranpetit, C. Lalueza-Fox, M. Mondal and S. Han for reading the manuscript and providing valuable comments. Marc de Manuel is supported by a FI fellowship from Generalitat de Catalunya. Martin Kuhlwilm is supported by a DFG fellowship (KU 3467/1-1). Vitor C. Sousa, Isabelle Dupanloup and Laurent Excoffier are supported by a Swiss NSF grant No. 31003A-143393. Tariq Desai is funded by the Gates Cambridge Trust. Oscar Lao is supported by a Ramón y Cajal grant from MINECO (RYC-2013-14797), and BFU2015-68759-P (FEDER). Pille Hallast is supported by Estonian Research Council Grant PUT1036. Joshua M. Schmidt, Aida M. Andrés and Sergi Castellano are funded by the Max Planck Society. Javier Prado-Martinez, Chris Tyler-Smith and Yali Xue were supported by The Wellcome Trust (098051). José María Heredia-Genestar is supported by the María de Maeztu Programme (MDM-2014-0370). Aylwyn Scally is supported by an Isaac Newton Trust/Wellcome Trust ISSF Joint Research Grant. John Novembre had support from an NIH U01CA198933 grant, and Benjamin M. Peter is supported by a Swiss SNF postdoctoral fellowship. The collection of fecal samples was supported by the Max Planck Society and Krekeler Foundation's generous funding for the Pan African Programme. Tomas Marques-Bonet would like to thank ICREA, EMBO YIP 2013, MINECO BFU2014-55090-P (FEDER), BFU2015-7116-ERC and BFU2015-6215-ERCU01, MH106874 grant, Fundacio Zoo Barcelona and Secretaria d'Universitats i Recerca del Departament d'Economia i Coneixement de la Generalitat de Catalunya for the support to his lab.

References and Notes

- 1.McBrearty S, Jablonski NG. First fossil chimpanzee. Nature. 2005;437:105–108. doi: 10.1038/nature04008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hvilsom C, Carlsen F, Heller R, Jaffré N, Siegismund HR. Contrasting demographic histories of the neighboring bonobo and chimpanzee. Primates. 2014;55:101–12. doi: 10.1007/s10329-013-0373-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobon I, et al. Demographic History of the Genus Pan Inferred from Whole Mitochondrial Genome Reconstructions. Genome Biol Evol. 2016;8:2020–2030. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evw124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Caswell JL, et al. Analysis of chimpanzee history based on genome sequence alignments. PLoS Genet. 2008;4:e1000057. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fischer A, et al. Bonobos fall within the genomic variation of Chimpanzees. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0021605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Becquet C, Patterson N, Stone AC, Przeworski M, Reich D. Genetic structure of chimpanzee populations. PLoS Genet. 2007;3:e66. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.0030066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fünfstück T, et al. The sampling scheme matters: Pan troglodytes troglodytes and P. t. schweinfurthii are characterized by clinal genetic variation rather than a strong subspecies break. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2015;156:181–91. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prado-Martinez J, et al. Great ape genetic diversity and population history. Nature. 2013;499:471–5. doi: 10.1038/nature12228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vervaecke H, Van Elsacker L. Hybrids Between Common Chimpanzees (Pan Troglodytes) And Pygmy Chimpanzees (Pan Paniscus) In Captivity. Mammalia. 1992;56:667–669. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Supplementary materials are available on Science Online.

- 11.Li H, Durbin R. Inference of human population history from individual whole-genome sequences. Nature. 2011;475:493–496. doi: 10.1038/nature10231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Excoffier L, Dupanloup I, Huerta-Sánchez E, Sousa VC, Foll M. Robust Demographic Inference from Genomic and SNP Data. PLoS Genet. 2013;9 doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wasser SK, et al. Genetic assignment of large seizures of elephant ivory reveals Africa's major poaching hotspots. Science. 2015;349:84–88. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa2457. (80-.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Green RE, et al. A Draft Sequence of the Neandertal Genome. Science. 2010;328:710–722. doi: 10.1126/science.1188021. (80-.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Prüfer K, et al. The complete genome sequence of a Neanderthal from the Altai Mountains. Nature. 2014;505:43–9. doi: 10.1038/nature12886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fu Q, et al. An early modern human from Romania with a recent Neanderthal ancestor. Nature. 2015;524:216–219. doi: 10.1038/nature14558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kuhlwilm M, et al. Ancient gene flow from early modern humans into Eastern Neanderthals. Nature. 2016;530:429–433. doi: 10.1038/nature16544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Prüfer K, et al. The bonobo genome compared with the chimpanzee and human genomes. Nature. 2012;486:527. doi: 10.1038/nature11128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Won YJ, Hey J. Divergence population genetics of chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 2005;22:297–307. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msi017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Becquet C, Przeworski M. A new approach to estimate parameters of speciation models with application to apes. Genome Res. 2007;17:1505–19. doi: 10.1101/gr.6409707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McVicker G, Gordon D, Davis C, Green P. Widespread Genomic Signatures of Natural Selection in Hominid Evolution. PLoS Genet. 2009;5:e1000471. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sankararaman S, et al. The genomic landscape of Neanderthal ancestry in present-day humans. Nature. 2014;507:354–357. doi: 10.1038/nature12961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vernot B, et al. Excavating Neandertal and Denisovan DNA from the genomes of Melanesian individuals. Science. 2016 doi: 10.1126/science.aad9416. (80-.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pickrell JK, Pritchard JK. Inference of Population Splits and Mixtures from Genome-Wide Allele Frequency Data. PLoS Genet. 2012:8. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rasmussen MD, Hubisz MJ, Gronau I, Siepel A. Genome-wide inference of ancestral recombination graphs. PLoS Genet. 2014;10:e1004342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meyer M, Kircher M. Illumina sequencing library preparation for highly multiplexed target capture and sequencing. Cold Spring Harb Protoc. 2010;5 doi: 10.1101/pdb.prot5448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kircher M, Sawyer S, Meyer M. Double indexing overcomes inaccuracies in multiplex sequencing on the Illumina platform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40 doi: 10.1093/nar/gkr771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fu Q, et al. DNA analysis of an early modern human from Tianyuan Cave, China. Pnas. 2013;110:2223–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1221359110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Renaud G, Stenzel U, Kelso J. LeeHom: Adaptor trimming and merging for Illumina sequencing reads. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014;42:e141. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate long-read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:589–595. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Garrison E, Marth G. Haplotype-based variant detection from short-read sequencing. arXiv Prepr. 2012:9. arXiv1207.3907. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marco-Sola S, Sammeth M, Guigó R, Ribeca P. The GEM mapper: fast, accurate and versatile alignment by filtration. Nat Methods. 2012;9:1185–8. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.2221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Delaneau O, Marchini J, Zagury JF. A linear complexity phasing method for thousands of genomes. Nat Methods. 2012;9:179–81. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Auton A, et al. A Fine-Scale Chimpanzee Genetic Map from Population Sequencing. Science. 2012;336:193–198. doi: 10.1126/science.1216872. (80-.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kuhn RM, Haussler D, James Kent W. The UCSC genome browser and associated tools. Brief Bioinform. 2013;14:144–161. doi: 10.1093/bib/bbs038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Paten B, et al. Genome-wide nucleotide-level mammalian ancestor reconstruction. Genome Res. 2008;18:1829–1843. doi: 10.1101/gr.076521.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paten B, Herrero J, Beal K, Fitzgerald S, Birney E. Enredo and Pecan: Genome-wide mammalian consistency-based multiple alignment with paralogs. Genome Res. 2008;18:1814–1828. doi: 10.1101/gr.076554.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.The Chimpanzee Sequencing and Analysis Consortium, Initial sequence of the chimpanzee genome and comparison with the human genome. Nature. 2005;437:69–87. doi: 10.1038/nature04072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Manichaikul A, et al. Robust relationship inference in genome-wide association studies. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:2867–2873. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Purcell S, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–2079. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hughes JF, et al. Chimpanzee and human Y chromosomes are remarkably divergent in structure and gene content. Nature. 2010;463:536–539. doi: 10.1038/nature08700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Danecek P, et al. The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics. 2011;27:2156–2158. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Excoffier L, Lischer HEL. Arlequin suite ver 3.5: A new series of programs to perform population genetics analyses under Linux and Windows. Mol Ecol Resour. 2010;10:564–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-0998.2010.02847.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.H P, et al. Great ape Y Chromosome and mitochondrial DNA phylogenies reflect subspecies structure and patterns of mating and dispersal. 2016:427–439. doi: 10.1101/gr.198754.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Felsenstein J. Phylip: phylogeny inference package (version 3.2) Cladistics. 1989;5:164–166. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:1969–1973. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Helgason A, et al. The Y-chromosome point mutation rate in humans. Nat Genet. 2015;47:453–457. doi: 10.1038/ng.3171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Langergraber K, Prüfer K. Generation times in wild chimpanzees and gorillas suggest earlier divergence times in great ape and human evolution. Proc …. 2012;109:15716–15721. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1211740109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kaessmann H, Wiebe V, Weiss G, Paabo S. Great ape DNA sequences reveal a reduced diversity and an expansion in humans. Nat Genet. 2001;27:155–156. doi: 10.1038/84773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Browning BL, Browning SR. Improving the accuracy and efficiency of identity-by-descent detection in population data. Genetics. 2013;194:459–471. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.150029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fischer A, Wiebe V, Pääbo S, Przeworski M. Evidence for a Complex Demographic History of Chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 2004;21:799–808. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msh083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reich DE, et al. Linkage disequilibrium in the human genome. Nature. 2001;411:199–204. doi: 10.1038/35075590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Henn BM, et al. From the Cover: Feature Article: Hunter-gatherer genomic diversity suggests a southern African origin for modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:5154–5162. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017511108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Shannon LM, et al. Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:13639–13644. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1516215112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Slatkin M. Linkage disequilibrium--understanding the evolutionary past and mapping the medical future. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:477–85. doi: 10.1038/nrg2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Peter BM, Slatkin M. Detecting range expansions from genetic data. Evolution (N Y) 2013;67:3274–3289. doi: 10.1111/evo.12202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gonder MK. Evidence from Cameroon reveals differences in the genetic structure and histories of chimpanzee populations. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:4766–4771. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1015422108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Wegmann D, Excoffier L. Bayesian inference of the demographic history of chimpanzees. Mol Biol Evol. 2010;27:1425–35. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Mitchell MW, et al. The population genetics of wild chimpanzees in Cameroon and Nigeria suggests a positive role for selection in the evolution of chimpanzee subspecies. BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15:3. doi: 10.1186/s12862-014-0276-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Oksanen J, et al. Package “vegan.” R Packag ver 2.0–8. 2013;254 [Google Scholar]

- 63.Frichot E, Mathieu F, Trouillon T, Bouchard G, François O. Fast and efficient estimation of individual ancestry coefficients. Genetics. 2014;196:973–983. doi: 10.1534/genetics.113.160572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tang H, Peng J, Wang P, Risch NJ. Estimation of individual admixture: Analytical and study design considerations. Genet Epidemiol. 2005;28:289–301. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K. Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res. 2009;19:1655–1664. doi: 10.1101/gr.094052.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lawson DJ, Hellenthal G, Myers S, Falush D. Inference of population structure using dense haplotype data. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:11–17. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Leslie S, et al. The fine-scale genetic structure of the British population. Nature. 2015;519:309–314. doi: 10.1038/nature14230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Schiffels S, Durbin R. Inferring human population size and separation history from multiple genome sequences. Nat Genet. 2014;46:919–25. doi: 10.1038/ng.3015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Staab PR, Zhu S, Metzler D, Lunter G. Scrm: Efficiently simulating long sequences using the approximated coalescent with recombination. Bioinformatics. 2014;31:1680–1682. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Burgess R, Yang Z. Estimation of hominoid ancestral population sizes under Bayesian coalescent models incorporating mutation rate variation and sequencing errors. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:1979–1994. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Miyata T, Hayashida H, Kuma K, Mitsuyasu K, Yasunaga T. Male-driven molecular evolution: a model and nucleotide sequence analysis. Cold Spring Harb Symp Quant Biol. 1987;52:863–867. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1987.052.01.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Venn O, et al. Strong male bias drives germline mutation in chimpanzees. Science. 2014;344:1272–1275. doi: 10.1126/science.344.6189.1272. (80-.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Patterson N, et al. Ancient admixture in human history. Genetics. 2012;192:1065–1093. doi: 10.1534/genetics.112.145037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Slatkin M, Pollack JL. Subdivision in an ancestral species creates asymmetry in gene trees. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:2241–2246. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msn172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Durand EY, Patterson N, Reich D, Slatkin M. Testing for ancient admixture between closely related populations. Mol Biol Evol. 2011;28:2239–2252. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Vernot B, Akey JM. Resurrecting Surviving Neandertal Lineages from Modern Human Genomes. Science. 2014;343:1017–1021. doi: 10.1126/science.1245938. (80-.) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Prüfer K, et al. FUNC: a package for detecting significant associations between gene sets and ontological annotations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2007;8:41. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-8-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Racimo F, Sankararaman S, Nielsen R, Huerta-Sánchez E. Evidence for archaic adaptive introgression in humans. Nat Rev Genet. 2015;16:359–371. doi: 10.1038/nrg3936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Hudson RR. Generating samples under a Wright-Fisher neutral model of genetic variation. Bioinformatics. 2002;18:337–8. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/18.2.337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Otto SP, Whitlock MC. eLS. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; Chichester, UK: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yang MA, Malaspinas AS, Durand EY, Slatkin M. Ancient structure in Africa unlikely to explain neanderthal and non-african genetic similarity. Mol Biol Evol. 2012;29:2987–2995. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mss117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sousa V, Hey J. Understanding the origin of species with genome-scale data: modelling gene flow. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14:404–414. doi: 10.1038/nrg3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Hernandez RD, et al. Classic selective sweeps were rare in recent human evolution. Science. 2011;331:920–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1198878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Nielsen R. Estimation of population parameters and recombination rates from single nucleotide polymorphisms. Genetics. 2000;154:931–942. doi: 10.1093/genetics/154.2.931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Adams AM, Hudson RR. Maximum-likelihood estimation of demographic parameters using the frequency spectrum of unlinked single-nucleotide polymorphisms. Genetics. 2004;168:1699–1712. doi: 10.1534/genetics.104.030171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Meng XL, Rubin DB. Maximum likelihood estimation via the ecm algorithm: A general framework. Biometrika. 1993;80:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Cunningham F, et al. Ensembl 2015. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D662–D669. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Rosenbloom KR, et al. The UCSC Genome Browser database: 2015 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43:D670–D681. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Davydov EV, et al. Identifying a high fraction of the human genome to be under selective constraint using GERP++ PLoS Comput Biol. 2010;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1001025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Davison AC, Hinkley DV. Bootstrap methods and their application. Cambridge University Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.