Abstract

Two diastereomeric analogues (1 and 2) of diaminopimelic acid (DAP) bearing an isoxazoline moiety were synthesized and evaluated for their inhibitory activities against meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase (m-Ddh) from the periodontal pathogen, Porphyromonas gingivalis. Compound 2 showed promising inhibitory activity against m-Ddh with an IC50 value of 14.9 μM at pH 7.8. The two compounds were further tested for their antibacterial activities against a panel of periodontal pathogens, and compound 2 was shown to be selectively potent to P. gingivalis strains W83 and ATCC 33277 with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 773 μM and 1.875 mM, respectively. Molecular modeling studies revealed that the inversion of chirality at the C-5 position of these compounds was the primary reason for their different biological profiles. Based on these preliminary results, we believe that compound 2 has properties consistent with it being a lead compound for developing novel pathogen selective antibiotics to treat periodontal diseases.

Keywords: diaminopimelic acid, antibacterial activity, meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase inhibitor, molecular modeling

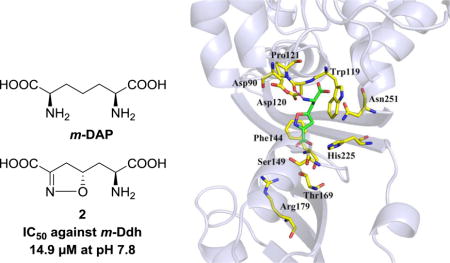

Graphical abstract

Bacterial infections remain a major threat to human health with considerable treatment costs and an array of related clinical complications. With the mounting incidence and mortality rates of infectious diseases, the current pace for discovery and development of novel antibiotics is far from satisfactory.1 A confounding factor is that, because maintenance of the human microbiome is vital for keeping in good physical health,2,3 the widespread use of broad-spectrum antibiotics in recent decades has perturbed the ecological balance of this microbiome. These drugs, with their unspecific effects on both pathogenic and non-pathogenic species, cause further unexpected clinical symptoms such as opportunistic infections, bacterial resistance and disorders of intestinal microbiota.4,5 Therefore, there is an urgent and continuing need to develop more efficient and less toxic antibiotics that could target a specific range of pathogenic species.

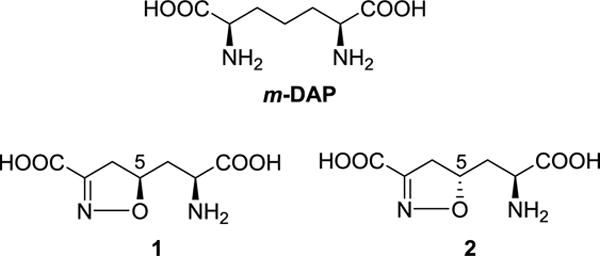

It is known that the diaminopimelic acid (DAP) biosynthesis pathway is the major source of L-lysine for most bacteria and some other related species,6 but this pathway is not present in mammalian cells. As a biosynthetic precursor in the DAP pathway, meso-diaminopimelic acid (m-DAP) plays a crucial role in the formation of peptidoglycan cell wall of Gram negative bacteria (Figure 1).7 Therefore, inhibitors that selectively suppress enzymes in this pathway may be able to act as novel antibiotics with selective anti-pathogenic action, satisfactory effectiveness and low toxicity. Meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase (m-Ddh), the only dehydrogenase present in the DAP biosynthetic pathway,8 acts as a critical enzyme, through which NADPH dependently catalyzes the conversion of L-tetrahydrodipicolinate (THDP) to m-DAP by utilizing an intermediate imine.9,10 One strategy to develop inhibitors against m-Ddh is to design and synthesize small molecules that are mimics of m-DAP. Consequently, a large number of m-DAP analogs have been previously reported;9,11,12 however, only a few of them showed notable activities. In particular, compound 1 (Figure 1) that contains an isoxazoline group had almost no activity against m-Ddh, while compound 2, its diastereoisomer, showed pH-dependent inhibition against m-Ddh from Bacillus sphaericus. Additionally, it also showed moderate antibacterial activity against B. sphaericus in an in vitro study.13 The most highly studied DAP enzymes are derived from B. sphaericus and Corynebacterium glutamicum,14,15 but, because Porphyromonas gingivalis is crucial in the onset and development of periodontal diseases that result from an unbalanced microbiome ecology in oral cavities,16,17 we are targeting meso-diaminopimelate dehydrogenase from that species in this study. In order to define a lead compound from DAP analogs to target m-Ddh, we synthesized compounds 1 and 2 in our laboratories, then evaluated their enzymatic inhibition against m-Ddh from P. gingivalis. Next, we tested their antibacterial activities against a panel of periodontal pathogens. Furthermore, molecular modeling studies were carried out to help understand interactions between these two compounds and the m-Ddh target protein.

Figure 1.

The structures of m-DAP and its analogs.

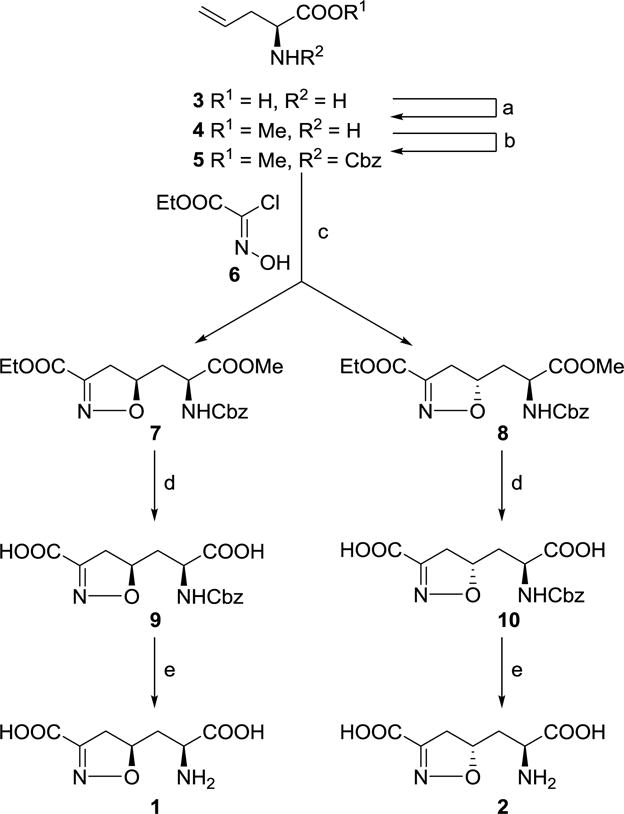

The syntheses of target compounds were performed following the reported procedure13 with modifications (Scheme 1). Protection of the amino and carboxyl groups of commercially available L-allylglycine was carried out via its conversion to the N-Cbz methyl ester (5). The key step in generating the isoxazoline skeleton was the 1,3-dipolar cycloaddition of ethyl chlorooximidoacetate by treatment of 5 (with protected amino and carboxyl groups) in the presence of a weak base that, in situ, generated the expected diastereoisomers 7 and 8.18 These two compounds were separated by flash column chromatography using Et2O/hexane system. Then, compound 7 was subjected to hydrolysis in NaOH aqueous solution to afford the diacid 9. Subsequent removal of Cbz group was carried out in the presence of TMSCl and NaI at room temperature in acetonitrile to generate compound 1. Similarly, hydrolysis of compound 8 gave the diacid 10, which was further deprotected to give compound 2.

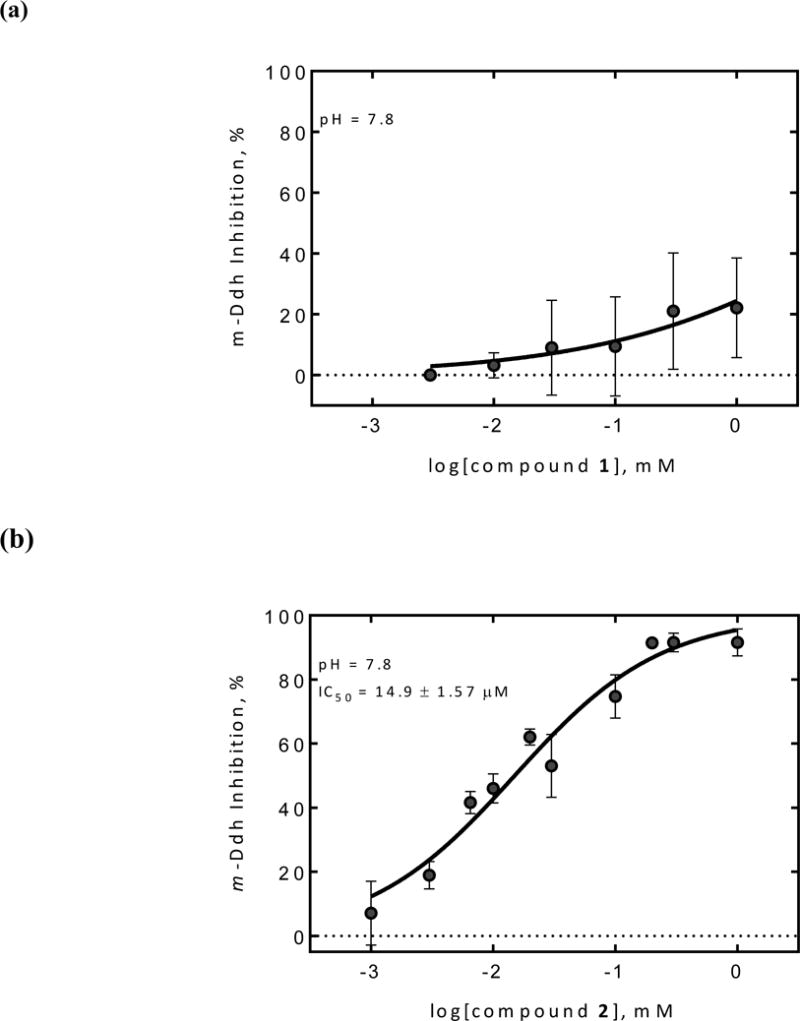

Both compounds were tested for their inhibition against m-Ddh according to the reported procedures.17 Since earlier work by Abbott et al. had shown the pH of the buffer solution was a crucial factor for inhibitory activity against B. sphaericus m-Ddh,9,13 we conducted the assay at pH 7.8 and pH 10.5, respectively (Figure 2). The results showed that compound 1 with a R configuration at C-5 position had no activity (up to 1 mM) at physiological condition (pH = 7.8), while compound 2 exhibited significant inhibitory activity against m-Ddh with an IC50 value of 14.9 μM. At the more basic condition of pH = 10.5, compound 1 was still not active against m-Ddh up to 3 mM while compound 2 had a steep reduction in potency with an IC50 value of 221 μM. These results were in line with previous reports, suggesting that the configuration inversion at the C-5 position in the isoxazoline ring diminished the binding interaction between compound 1 and m-Ddh. Additionally, compound 2 could exert its enzymatic inhibition effectively at physiological-like conditions, but was less effective at more basic conditions. A conformational change or ionization of the enzyme at high pH presumably accounts for the reduced enzymatic inhibition of compound 2.13

Figure 2.

Dose-dependent studies of compound 1 and 2 against P. gingivalis m-Ddh at different pH values. (a) Compound 1 and (b) Compound 2 inhibition against P. gingivalis m-Ddh at pH 7.8. (c) Compound 1 and (d) Compound 2 inhibition against P. gingivalis m-Ddh at pH 10.5.

Compound 2 was further evaluated for its potentially selective whole-cell activity against specific pathogens with respect to a panel of periodontal pathogens. In this assay, four strains were chosen, including P. gingivalis strains W83 and ATCC 33277, which possess the target m-Ddh, and Fusobacterium nucleatum strain ATCC 25586 and Staphylococcus aureus strain N315, which do not possess m-Ddh. Compound 2 was thus tested by a broth microdilution method.19 The assay results showed that compound 2 exhibited inhibitory activities against P. gingivalis strains W83 and ATCC 33277 with minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) values of 773 μM and 1.875 mM, respectively (Table 1). In contrast, there was no visual inhibition of cell growth by the F. nucleatum strain ATCC 25586 and the S. aureus strain N315 with concentrations of up to 3 mM. These preliminary screens suggest that compound 2 shows selective growth inhibition against P. gingivalis. A likely explanation for the significant enzymatic activity and relatively lower cellular activity of compound 2 is that the highly hydrophilic molecule does not easily penetrate through cell membranes. Thus, increasing its hydrophobicity by modifying of the DAP skeleton would appear to be a reasonable strategy for improving cellular activity.

Table 1.

The minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of compound 2 against periodontal pathogens.

| Periodontal pathogens | MIC | m-Ddh homologs |

|---|---|---|

| P. gingivaiis strain W83 | 773 μΜ | Yes |

| P gingivaiis strain ATCC 33277 | 1.875 mM | Yes |

| Fusobacterium nucieatum strain ATCC 25586 | No growth inhibition up to 3 mM | No |

| Staphylococcus aureus strain N315 | No growth inhibition up to 3 mM | No |

The different biological assay results of these two enantiomers in their enzymatic inhibitions and antibacterial activities prompted us to look for the binding interactions with m-Ddh. m-DAP, compounds 1 and 2 were first sketched in Sybyl-X 2.0 and assigned Gasteiger-Hückel charges. Then, each was immersed in a square box of water molecules and these solvated systems were energy minimized (20,000 iterations) with the Tripos forcefield. The resulting 3D structures of m-DAP, compounds 1 and 2 are displayed in Figure 3. Overlaying these molecules showed that the conformations of portion A in compounds 1 and 2 were similar, while the conformations of portion B were different due to the effects of stereochemistry.

Figure 3.

The 3D structures of m-DAP, compounds 1 and 2 after energy minimization. The parts in compounds 1 and 2 share similar conformation was defined as portion A and the rest as portion B. All oxygen atoms are in red and nitrogen atoms in blue; For carbon atoms, m-DAP is in yellow, compounds 1 in orange, compound 2 in green.

We are not aware of any report on the crystal structure of m-Ddh (oxidoreductase, Gfo/Idh/MocA family member) from P. gingivalis in complex with compounds 1 or 2. However, the crystal structures of m-Ddh from P. gingivalis in complex with another compound, 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid (PDB ID: 3BIO) and compound 2 in complex with C. glutamicum diaminopimelate dehydrogenase have been reported (PDB ID: 3DAP).20 Comparing these two crystal structures, we found that the binding site of compound 2 in C. glutamicum diaminopimelate dehydrogenase was very similar to that of 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazine ethanesulfonic acid in m-Ddh from P. gingivalis (Figure 4). Thus, we adopted 3BIO as our template protein and the binding orientation of compound 2 in 3DAP for the target compounds in m-Ddh. The protein was built by adding hydrogen atoms, assigning Gasteiger-Hückel charges, and optimizing hydrogen coordinates by a 10,000 iteration minimization while holding all heavy atoms as fixed (an aggregate) under the Tripos forcefield (TAFF) in Sybyl-X 2.0.21

Figure 4.

The alignment of backbone atoms of proteins 3BIO (blue) and 3DAP (orange). The ligands in 3BIO and 3DAP are shown as sticks and colored in magentas and green, respectively.

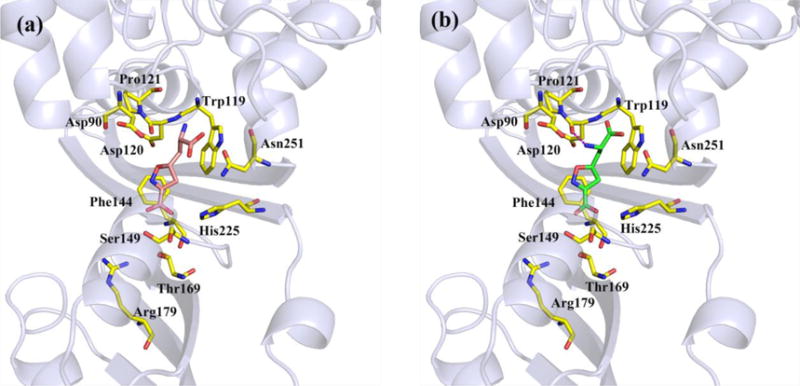

Compounds 1 and 2 were next docked into the m-Ddh binding site with GOLD 5.4.22 The docking models were analyzed based on two criteria: 1) the binding orientation of compounds 1 and 2 in m-Ddh being similar to that of compound 2 in the C. glutamicum protein and 2) high CHEM-PLP scores. We then ranked these docking models using the HINT (Hydropathic INTeractions) free energy scoring tool.23 The docking models with the highest HINT score of compounds 1 and 2 were chosen as the optimal docking models, respectively (Table 2 and Figure 5). Figure 5 shows that the hydrophobic interactions with Trp119, Phe144 and the electrostatic interactions with the side chains of Ser149 and Thr169 in the m-Ddh/compound 1 and m-Ddh/compound 2 complexes were almost the same, i.e., mainly with portion A of 1 and 2. However, for portion B of compounds 1 and 2, the interactions are very different: in the m-Ddh/compound 2 complex (Figure 5b), there is a hydrogen bond to Asp120, but in the m-Ddh/compound 1 complex (Figure 5a), the inversion of chirality leads to two consequences, a) that hydrogen bond to Asp120 is lost and 2) the carboxyl group of 1 moved closer to the side chain of Asp90. This produces an unfavorable interaction between these two negative centers, which is detrimental to the binding of compound 1. The two different configurations of 1 and 2, particularly in portion B, produces variant binding affinities and ultimately, different enzymatic activities of the two compounds.

Table 2.

The GOLD (CHEM-PLP) and HINT scores for the optimal binding poses of compounds 1 and 2.

| Compound 1 | Compound 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| CHEM-PLP | 41 | 51 |

| HINT | 245 | 477 |

Figure 5.

The binding modes of (a) compound 1 and (b) compound 2 in the binding pocket of m-Ddh from docking studies. Compounds 1 atoms: carbon (orange); compounds 2 atoms: carbon (green); amino acid residue atoms: carbon (yellow); oxygen (red); nitrogen (blue). The magenta dashed lines represent the hydrogen bond.

In conclusion, two diastereomers of DAP analogs bearing an isoxazoline moiety were synthesized and evaluated for their inhibition against m-Ddh from the periodontal pathogen P. gingivalis, and for their antibacterial activities. The results showed that only compound 2, which has an S stereocenter at the C-5 position of the isoxazoline ring, displays significant inhibitory activity against m-Ddh under physiological conditions. Additionally, in our limited survey, compound 2 also shows selective inhibition against P. gingivalis. Molecular modeling studies suggested that the inversion of chirality at the C-5 position of isoxazoline ring between compounds 1 and 2 leads to their different binding affinities and that the hydrogen bond between compound 2 and m-Ddh plays a crucial role in its enzymatic inhibition. These preliminary results suggest that compound 2 may serve as a promising lead compound for the discovery of novel antibiotics to treat periodontal diseases with selective effectiveness and reduced toxicity. Further studies on rational design and synthesis of m-DAP analogs are underway.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis route of m-DAP analogs 1 and 2 containing an isoxazoline ring system. Reagents and conditions: (a) TMSCl, MeOH, 97%; (b) CbzCl, Et3N, DMAP, CH2Cl2, 49%; (c) NaHCO3, AcOEt, 37% for 7 and 42% for 8; (d) MeOH, 1 N NaOH, 90% for 9 and 95% for 10; (e) TMSCl, NaI, MeCN, 35% for 1 and 43% for 2.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank NIH for financial support. This work was partially supported by R01DE023078 and Virginia Commonwealth University CCTR Endowment Fund Multi-School Grant.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Boucher HW, Talbot GH, Bradley JS, et al. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:1. doi: 10.1086/595011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Avila M, Ojcius DM, Yilmaz O. DNA Cell Biol. 2009;28:405. doi: 10.1089/dna.2009.0874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Johnson CL, Versalovic J. Pediatrics. 2012;129:950. doi: 10.1542/peds.2011-2736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jernberg C, Lofmark S, Edlund C, et al. Microbiol-Sgm. 2010;156:3216. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.040618-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rashid MU, Weintraub A, Nord CE. Anaerobe. 2012;18:249. doi: 10.1016/j.anaerobe.2011.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Scapin G, Blanchard JS. Adv Enzymol Ramb. 1998;72:279. doi: 10.1002/9780470123188.ch8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox RJ. Nat Prod Rep. 1996;13:29. doi: 10.1039/np9961300029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scapin G, Cirilli M, Reddy SG, et al. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3278. doi: 10.1021/bi9727949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misono H, Soda K. J Biol Chem. 1980;255:599. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Maniscalco SJ, Saha SK, Fisher HF. Biochemistry. 1998;37:14585. doi: 10.1021/bi980923v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gelb MH, Lin YK, Pickard MA, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 1990;112:4932. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam LKP, Arnold LD, Kalantar TH, et al. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:11814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Abbott SD, Lanebell P, Sidhu KPS, et al. J Am Chem Soc. 1994;116:6513. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Misono H, Soda K. Agr Biol Chem. 1980;44:227. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Misono H, Ogasawara M, Nagasaki S. Agr Biol Chem. 1986;50:2729. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kassebaum NJ, Bernabe E, Dahiya M, et al. J Dent Res. 2014;93:1045. doi: 10.1177/0022034514552491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stone VN, Parikh HI, El-rami F, et al. PloS one. 2015:10. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0141126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kozikowski AP, Adamczyk M. J Org Chem. 1983;48:366. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jorgensen JH, Turnidge JD. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 9th. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scapin G, Cirilli M, Reddy SG, et al. Biochemistry. 1998;37:3278. doi: 10.1021/bi9727949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ballesteros JA, Weinstein H. Integrated methods for the construction of three dimensional models and computational probing of structure function relations in G protein-coupled receptors. In: Sealfon SC, Conn PM, editors. Methods in Neurosciences. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 1995. pp. 366–428. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gohlke H, Kiel C, Case DA. J Mol Biol. 2003;330:891. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(03)00610-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kellogg GE, Abraham DJ. Hydrophobicity: is LogP o/w more than the sum of its parts? Eur J Med Chem. 2000;651:661. doi: 10.1016/s0223-5234(00)00167-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]