Abstract

Purpose of Review

Our objective was to review advances in bile acids (BA) in health and disease published in the last two years. BA diarrhea (BAD) is recognized as a common cause of chronic diarrhea, and its recognition has been facilitated by development of new screening tests.

Recent Findings

Primary BAD can account for 30% of cases of chronic diarrhea. The mechanisms leading to BAD include inadequate feedback regulation by fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF-19) from ileal enterocytes, abnormalities in synthesis or degradation of proteins involved in FGF-19 regulation in hepatocytes, and variations in function of the bile acid receptor, TGR5 (GPBAR1).

75SeHCAT is the most widely used test for diagnosis of BAD. There has been significant validation of fasting serum FGF-19 and 7 α-hydroxy-cholesten-3-one (C4), a surrogate measure of BA synthesis.

BA sequestrants are the primary treatments for BAD; the FXR-FGF-19 pathway provides alternative therapeutic targets for BAD.

BA-stimulated intestinal mechanisms contribute to the beneficial effects of bariatric surgery on obesity, glycemic control, and the treatment of recurrent C. difficile infection.

Summary

Renewed interest in the role of BAs is leading to novel management of diverse diseases besides BAD.

Keywords: malabsorption, bile salts, diarrhea, chronic, glycemia, obesity, pouchitis

Introduction

In recent years, there has been new interest in the role of bile acids (BA) in diverse diseases including obesity, glycemic control, and C. difficile infection, besides BA diarrhea (BAD), although the latter still remains the predominant condition associated with altered BA balance.

BAD is a significant cause of diarrhea. There are three types of BAD: type 1, bile acid malabsorption (BAM), is secondary to ileal resection or active ileal disease; type 2 is associated with increased BA production; and type 3 is associated with other gastrointestinal conditions that result in malabsorption of BAs, such as post-cholecystectomy, celiac disease, chronic pancreatitis and microscopic colitis.

The first section reviews recent advances in the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and short- and long-term outcomes of treatment of BAD, with particular focus on type 2 BAD. In order to place recent advances in context, we include the use of 75selenium homotaurocholic acid test (75SeHCAT), 7 α-hydroxy-cholesten-3-one (C4), serum fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF-19), and treatment of BAD with bile acid sequestrants.

Emerging Epidemic: Epidemiology of Type 2 BAD

Type 2 BAD is estimated to occur in 28.1% of patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea (IBS-D) in secondary and tertiary centers in the United Kingdom (UK) and Sweden [1]. This estimate was based on a pooled analysis using diverse (Manning, Kruis, Rome I, II or III) criteria for IBS-D and a positive 75SeHCAT study of less than 10% retention. The estimate is similar to an average 25% of type 2 BAD in functional diarrhea or IBS-D, based on 75SeHCAT <10%, or increased fasting serum FGF-19, C4, or 48-hour fecal BA excretion from studies published from diverse centers [2]. 75SeHCAT was the most widely used test for the diagnosis of BAD. There is also increased appreciation of BAD in microscopic colitis [3].

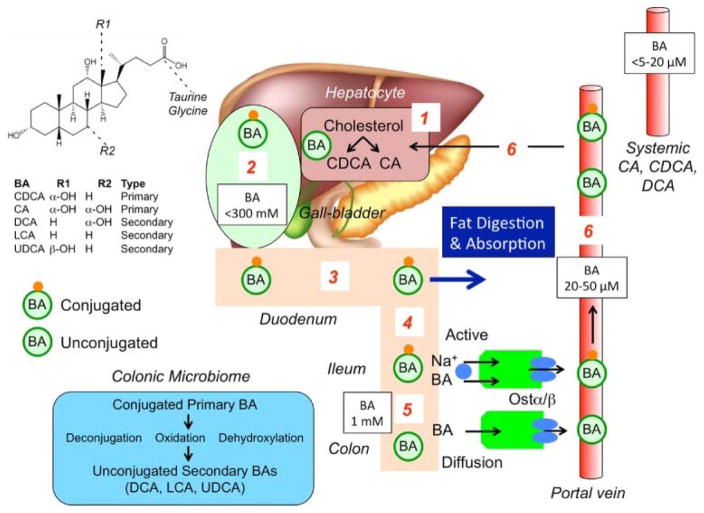

Enterohepatic Circulation of Bile Acids (Figure 1)

Figure 1. Synthesis, secretion and enterohepatic circulation of BAs in humans.

(1) Primary bile acids (BAs) are synthesized in hepatocytes from cholesterol. (2) BAs are conjugated to glycine and taurine and are stored in the gallbladder at high concentrations. (3) After feeding, conjugated BAs are secreted in the intestine where they emulsify dietary fats and form mixed micelles that facilitate digestion and absorption of the products of triglyceride digestion. (4) Conjugated BAs are actively absorbed by the apical sodium BA co-transporter (ASBT [IBAT]) at the apical membrane of enterocytes of the terminal ileum. (5) In the colon, bacteria deconjugate and dehydroxylate primary BAs to form secondary BAs, which are passively absorbed. (6) Conjugated and unconjugated BAs enter the portal vein and recirculate to the liver for re-use.

Reproduced with permission from ref. 4, Bunnett NW. Neuro-humoral signalling by bile acids and the TGR5 receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol 2014; 592:2943-2950.

Bile acids are produced from cholesterol in the liver. The rate limiting enzyme in bile acid synthesis is 7α-hydroxylase (cytochrome P4507A1 CYP7A1); C4, an intermediary in the pathway of cholesterol synthesis, is measurable in serum. The primary BAs produced in the liver are cholic acid (CA) and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), which are conjugated with taurine and glycine and are excreted into bile and stored in the gallbladder (Figure 1) [4]. In response to feeding, primary BAs are released into the small bowel and aid in the digestion of fat by formation of micelles. Most of the BAs (~95%) are absorbed in the conjugated form by active transporters [apical sodium bile acid transporter (ASBT) or ileal BA transporter (IBAT)] in the terminal ileum and transported to the liver via the portal circulation to be recycled and reused. CA and CDCA absorbed by the ileal enterocytes bind to farnesoid X-receptor (FXR) which stimulates synthesis of FGF-19. FGF-19 is transported via the portal circulation and enters the hepatocyte through fibroblast growth factor-receptor 4 (FGF-R4) with interaction with a surface protein, klotho β, and inhibits BA synthesis in the hepatocyte through actions on CYP7A1.

In the colon, CA and CDCA are deconjugated and dehydroxylated to secondary BAs, predominantly deoxycholic acid (DCA) and lithocholic acid (LCA). The colon reabsorbs passively by diffusion about 75% of the BAs passing the ileocecal valve. In the colon, CDCA and DCA stimulate secretion of fluids [5] and motility, including high amplitude propagated contractions [6, 7].

Recent Insights on Bile Acid Diarrhea and Enterohepatic Circulation

a. What causes primary BAD?

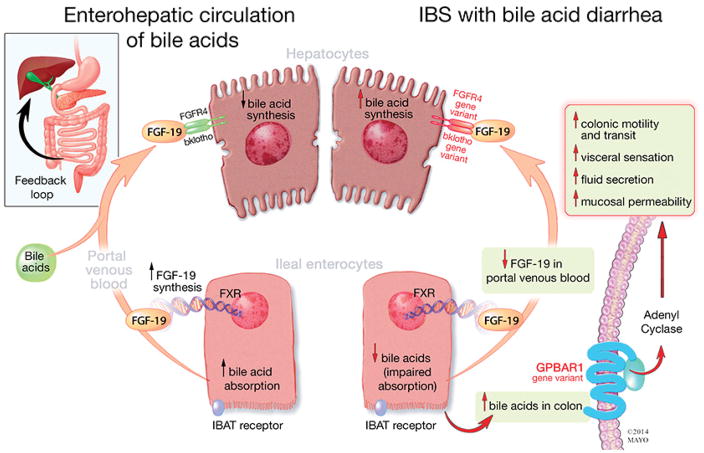

Type 2 (or primary) BAD is associated with decreased circulating levels of FGF-19, an indirect measure of decreased ileal FGF-19 production, and with lack of feedback inhibition of hepatic synthesis of BAs leading to high colonic concentrations and increase in fecal BA loss [8]. Mutations of the SLC10A2 gene (for ASBT or IBAT) are rare, and normal ileal uptake of BAs has been demonstrated, excluding membrane transport, as the cause of decreased FGF-19 production. However, a recent study showed decreased baseline expression of FGF-19 and ASBT measured by mRNA in ileal biopsies obtained from fasting patients with BAD (demonstrated by low 75SeHCAT values) [9]. These differences in expression were not the result of differences in genetic polymorphisms in the genes encoding the proteins and transporters on the enterohepatic circulation between patients with primary BAD (defined by 75SeHCAT less than 15%) and those with idiopathic diarrhea [9]. On the other hand, variants in genes involved in feedback regulation of BA synthesis [Klotho β (KLB), p=0.06 and FGF-R4, p=0.09] were potentially associated with a subgroup with elevated serum C4 [10]. Genetic polymorphisms in KLB, FGF-R4 and GPBAR1 (TGR5) are all associated with accelerated colonic transit that is attributed to increased hepatocyte synthesis or responsiveness of the BA receptor (summarized in Figure 2) [11].

Figure 2. Enterohepatic circulation of bile acids in irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhea (IBS-D).

Ileal enterocytes absorb BAs through a receptor-mediated process [ileal bile acid transporter (IBAT)]. Intracellular BAs activate farnesoid-X receptor to increase FGF-19 synthesis. FGF-19 in portal circulation downregulates hepatocyte BA synthesis through inhibition of CYP7A1, a rate limiting enzyme. Disorders of FGF-19 synthesis by ileal enterocytes or genetic variations of FGF-R4 or β-klotho result in excess BA synthesis by the hepatocytes and, ultimately, in higher levels of BAs that reach the colon, resulting in activation of the G-protein coupled BA receptor 1 (GPBAR1) with enteroendocrine cell stimulation [(e.g. release of 5-hydroxytryptamine (5-HT)] and stimulation of colonic motility, acceleration of colonic transit, activation of visceral sensation and fluid secretion (through increased intracellular cAMP, increased mucosal permeability or chloride ion secretion). Gene variation in GPBAR1 is associated with increased colonic transit in IBS-D.

Reproduced with permission from ref. 11, Camilleri M. Physiological underpinnings of irritable bowel syndrome: neurohormonal mechanisms. J Physiol 2014; 592:2967-2980.

b. What is the bile acid target receptor?

TGR5 is a G protein coupled receptor located in the epithelial surface of gallbladder and intestinal cells. It is also located in the basolateral surface of smooth muscle, neural, and immune cells. Bile acids activate TGR5 in enteroendocrine cells to produce glucagon like peptide 1 (GLP-1), primarily via targeting the receptors on the basolateral surface [12]. GLP-1 improves glucose homeostasis by inhibiting gastric motility, and by stimulating insulin secretion and inhibiting glucagon secretion by the pancreas [4]. TGR5 is an important receptor for mediating effects of BAs on motility, directly by action of TGR5 on neurons, and indirectly by stimulating serotonin release (4).

c. Are lipid abnormalities defining a separate group of BAD?

A subgroup of patients with type 2 BAD with close to normal fasting serum FGF-19 had fasting hypertriglyceridemia [9]. There were positive associations with triglycerides, weight and age in this group. The authors have postulated that this could be another subgroup of patients with type 2 BAD that cannot be explained by a defective FXR/FGF-19 pathway [9]. Further studies are needed.

d. Are bile acids potentially important in the absence of overt BAD?

Differences in BA profiles in stool have been observed in IBS-D without BAD compared to healthy volunteers. Specifically, a higher proportion of primary BAs is present in serum and stool of patients with IBS-D [13,14]. In addition, total and primary BAs were significantly associated with colonic transit at 48 hours in these patients with normal C4 levels [14]. These data suggest that, even in the absence of overt BAD, there may be effects of BAs that contribute to the diarrhea.

e. What about interaction of bile acids and microbiome in IBS?

In vitro deconjugation of glycine-conjugated ursodeoxycholic acid (GUDCA) to ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) in feces of patients with IBS was decreased compared to feces from healthy volunteers. There were no differences in effects between IBS subtypes (IBS-C vs. IBS-D). These data suggest that alterations in microbiome may play a role in the differences in effects of BAs in IBS subgroups [13]. In this same study, the microbiome of IBS-D had higher relative counts of E.coli in IBS-D and Bacteroides and Bifidobacterium in IBS-C. None of the patients had type 2 BAD (according to serum C4 levels). The reason for the increase in fecal primary BA proportions may be alteration in microbiota in IBS or failure of dehydroxylation due to rapid colonic transit in patients with IBS-D.

f. A novel role for a non-secretory secondary BA, UDCA, in Clostridium difficile sporulation, infection and pouchitis

The restoration of secondary BA metabolism may be the key mechanism for fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) in treating recurrent C. difficile infection. Thus, BAs at concentrations found in patients after FMT did not induce germination and inhibited vegetative growth of C. difficile strains [15]. Moreover, administration of UDCA eradicated C. difficile infection in a patient with recurrent pouchitis [16]. Complete microbial engraftment following FMT is not required to recover from recurrent C. difficile infection, and secondary BA metabolism could potentially provide resistance to infection [17]. Subjects cured by autologous FMT typically harbored greater relative abundance of members of the Clostridium XIVa clade or Holdemania in the family Erysipelotrichaceae, as well as Parasutterella pre-FMT. The authors proposed that subjects who recovered following autologous FMT may have done so, at least in part, because of the presence of taxa active in secondary BA biosynthesis [17].

Diagnosis of Bile Acid Diarrhea

The most commonly used test for the diagnosis of BAD since 1983 is the 75SeHCAT test. The 75SeHCAT utilizes a taurine conjugate of 23-selena-25-homocholic acid (SeHCAT) which is given to the patient orally. 75SeHCAT is reabsorbed and recirculated by the same process as natural BAs [18]. A baseline scan by a gamma counter detects 75SeHCAT activity, and a repeat scan is done in 7 days to determine the amount (percentage) of 75SeHCAT retained. 75SeHCAT retention <10% suggests moderate BAD and <5% suggests severe BAD. These cut-offs have been corroborated with response to BA sequestrants of 80% and 96% respectively compared to 70% in patients with 75SeHCAT retention <15% [19].

A 48-hour stool collection for total fecal BAs is done during the last two days of ingestion of a high fat diet and is the gold standard for measurement of BA excretion with a value of >2337μM/48 hours as the cut-off for abnormal [20]. The test is available in a few laboratories; it is used clinically for diagnosis of BAD and is available as a reference lab test for centers in the USA.

A recent advance in the diagnosis of BAD is the measurement of fasting FGF-19, based on a commercially available ELISA. A fasting level of <145 pg/mL has 61% and 82% positive and negative predictive value respectively for BAD using 75SeHCAT retention of <10% as a gold standard [21]. A recent study confirmed low FGF-19 in patients with BAD compared to diarrhea controls (62–70 pg/mL and 103–116 pg/mL respectively). The recent values are lower than prior reports, and robust values to define what is abnormal are required to establish FGF-19 as a clinical diagnostic test. In addition, postprandial levels may also prove useful, but require validation [22]. The picture is further complicated by past work that demonstrated a triphasic response of FGF-19 post-meals with an initial decrease, followed by an increase and subsequent decrease.

Another diagnostic test for BAD is increased serum C4, a BA precursor. In patients with all three types of BAD, fasting C4 >35 ng/ml had sensitivity and specificity of 87% and 86% when compared to 75SeHCAT retention <10%. This translates to a high negative likelihood ratio of 94% and positive likelihood ratio of 71%. The same ratios increase to 98% and 74% respectively when response to BA sequestrant is used as the gold standard [23]. This has been further validated in other studies. The timing of measurements is important; serum C4 has two peaks at noon and at 9:00 p.m. [24]. There is great promise in the development of serum C4 test for use in clinical practice in the U.S. through reference labs. Fasting serum C4 >52.5 ng/mL defines abnormal values in our laboratory [25].

Treatments for Bile Acid Diarrhea

Bile acid sequestrants

BA sequestrants are approved for the treatment of hyperlipidemia. They bind BAs and decrease their potential to cause diarrhea. They are the treatment of choice for BAD. There are three currently available BA sequestrants: cholestyramine (powder form), colestipol and colesevelam (both available in tablet form).

There has been only one randomized trial of cholestyramine efficacy in BAD, defined by a mean of 3 stools per day with less than 1 watery stool per day. The trial showed response rates of 40% and 53.8% in patients with 75SeHCAT retention <10% or 20% respectively. In comparison, the placebo hydroxypropyl cellulose group showed response rates of 25% and 38.5% respectively (no statistical difference between the two treatments) [26]. However, there was a statistically significant difference in the decreased number of watery stools with cholestyramine compared to hydroxypropyl cellulose, which also binds bile salts in the colon without affecting hepatic BA synthesis [27]. Eleven percent of the cholestyramine group had to discontinue treatment because of side effects and unpalatability [28].

Colestipol has been assessed in an open-label trial in patients with 75SeHCAT retention <20% in whom it reduced stool frequency and IBS severity score using the IBS Severity Scoring System (IBS-SSS) [29].

Colesevelam, 1875 mg daily, was tested in an open-label study in patients with BAD and resulted in a decrease in average stool consistency and increase in stool excretion of fecal BAs, which was reflected in an increase in C4 [30].

Patients will likely need long-term therapy with BA sequestrants for symptom relief. In a recent long-term follow-up study of patients with a median time from diagnosis of 6.8 years, 38% were still on BA sequestrants with adequate relief of their symptoms, while 24% had discontinued therapy, with the most common reason being tolerability [31].

FXR agonist

Obeticholic acid, a potent FXR agonist that stimulates FGF-19 production and decreases hepatic BA synthesis, has been shown (at 25 mg orally, daily for two weeks) to decrease stool frequency and improve stool consistency, increase FGF-19 levels, and decrease serum C4 and serum BAs in patients with primary and secondary BAD, particularly those with ileal resection length less than 45 cm. A clinical benefit was not seen in patients with idiopathic chronic diarrhea with normal 75SeHCAT levels [32].

Low fat diet

A low fat diet improves several gastrointestinal symptoms including urgency to open bowels, abdominal bloating, bowel frequency, lack of control, and flatulence when used alone in mild BAD or in those with 75SeHCAT retention of 10–15%, or when used in combination with colesevelam in patients with severe BAD or in those with 75SeHCAT retention <5% [33].

Role of Bile Acids in Effects of Roux-en-Y Bariatric Surgery

There is an increase in the total BA pool and in alteration of composition of BAs after Roux-en-Y- gastric bypass (RYGB) and vertical sleeve gastrectomy (VSG). An increase in BAs has been linked to the improved glucose homeostasis and sustained weight loss post- bariatric surgery. The increase in BAs is associated with increase in circulating GLP-1, caused by stimulation of GLP-1 secretion from intestinal enteroendocrine L cells via the GPBAR1/TGR5 receptor. FXR has also been shown to be a target that mediates effects of VSG [34].

Conclusion

Bile acid diarrhea is a significant and treatable cause of diarrhea in patients with chronic idiopathic diarrhea and should be evaluated as the cause in these patients. Studies on the mechanisms and diagnosis are progressing rapidly, and the renewed interest in the role of BAs is leading to novel management of human diseases including obesity, glycemic control, and recurrent C. difficile infection.

Key Points.

Bile acid diarrhea is a significant cause of chronic diarrhea.

Primary bile acid diarrhea results from decreased FGF-19 and increased liver production of bile acids that may result from different mechanisms.

Bile acid sequestrants are effective treatments of bile acid diarrhea; in the future FXR agonists may also prove efficacious.

Renewed interest in BAs is leading to novel management of human diseases including obesity, glycemic control, and recurrent C. difficile infection.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mrs. Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial assistance.

Financial Support

Dr. Camilleri is supported by grant R01-DK92179 from National Institutes of Health.

Abbreviations used

- BAD

bile acid diarrhea

- C4

7 α-hydroxy-cholesten-3-one

- FGF-19

fibroblast growth factor-19

- FGFR4

fibroblast growth factor receptor 4

- FXR

farnesoid X receptor

- GPBAR1

G-protein coupled bile acid receptor (aka TGR5)

- KLB

klotho β

Footnotes

Disclosures: The authors have no financial or personal relationships that could present a potential conflict of interest.

Author’s contributions: Both authors performed the literature review, and drafting and revision of the manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors are currently conducting sponsored research funded by NGM Pharmaceuticals on effects of an FGF-19 analog.

References

- 1.Slattery SA, Niaz O, Aziz Q, et al. Systematic review with meta-analysis: the prevalence of bile acid malabsorption in the irritable bowel syndrome with diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;42:3–11. doi: 10.1111/apt.13227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Valentin N, Camilleri M, Altayar O, et al. Biomarkers for bile acid diarrhoea in functional bowel disorder with diarrhoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gut. 2015 Sep 7; doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2015-309889. pii: gutjnl-2015–309889 Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fernandez-Bañares F, Esteve M, Salas A, et al. Bile acid malabsorption in microscopic colitis and in previously unexplained functional chronic diarrhea. Dig Dis Sci. 2001;46:2231–2238. doi: 10.1023/a:1011927302076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bunnett NW. Neuro-humoral signalling by bile acids and the TGR5 receptor in the gastrointestinal tract. J Physiol. 2014;592:2943–2950. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.271155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wingate DL, Krag E, Mekhjian HS, Phillips SF. Relationships between ion and water movement in the human jejunum, ileum and colon during perfusion with bile acids. Clin Sci Mol Med. 1973;45:593–606. doi: 10.1042/cs0450593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kirwan WO, Smith AN, Mitchell WD, et al. Bile acids and colonic motility in the rabbit and the human. Gut. 1975;16:894–902. doi: 10.1136/gut.16.11.894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bampton PA, Dinning PG, Kennedy ML, et al. The proximal colonic motor response to rectal mechanical and chemical stimulation. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2002;282:G443–G449. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00194.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Walters JR, Tasleem AM, Omer OS, et al. A new mechanism for bile acid diarrhea: defective feedback inhibition of bile acid biosynthesis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:1189–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.04.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9**.Johnston IM, Nolan JD, Pattni SS, et al. Characterizing factors associated with differences in FGF19 blood levels and synthesis in patients with primary bile acid diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111:423–432. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.424. This article provides further insights on the differences in serum fasting and postprandial FGF-19 levels and associations with genetic and transcription changes in ileal mucosa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Acosta A, et al. Effect of increased bile acid synthesis or fecal excretion in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1621–1630. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Camilleri M. Physiological underpinnings of irritable bowel syndrome: neurohormonal mechanisms. J Physiol. 2014;592:2967–2980. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.270892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12*.Brighton CA, Rievaj J, Kuhre RE, et al. Bile acids trigger GLP-1 release predominantly by accessing basolaterally located G protein–coupled bile acid receptors. Endocrinology. 2015;156:3961–3970. doi: 10.1210/en.2015-1321. This article provides further details on bile acid signalling of GLP-1 production. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13*.Dior M, Delagrèverie H, Duboc H, et al. Interplay between bile acid metabolism and microbiota in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2016;28:1330–1340. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12829. The authors provide information on microbiota and its influences on bile acid changes in patients with IBS. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peleman C, Camilleri M, Busciglio I, et al. Colonic transit and bile acid synthesis or excretion in patients with irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea without bile acid malabsorption. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016 Nov 14; doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2016.11.012. pii: S1542–3565(16)31047-3 [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15**.Weingarden AR, Dosa PI, DeWinter E, et al. Changes in colonic bile acid composition following fecal microbiota transplantation are sufficient to control Clostridium difficile germination and growth. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0147210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147210. This is one of the first studies to highlight the role of bile acids in FMT for Clostridium difficile infection. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16*.Weingarden AR, Chen C, Zhang N, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid inhibits Clostridium difficile spore germination and vegetative growth, and prevents the recurrence of ileal pouchitis associated with the infection. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2016;50:624–630. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000427. This article reports the inhibitory action of UDCA on inhibiting the vegetative growth of Clostridium difficile. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Staley C, Kelly CR, Brandt LJ, et al. Complete microbiota engraftment is not essential for recovery from recurrent Clostridium difficile infection following fecal microbiota transplantation. MBio. 2016 Dec 20;7(6) doi: 10.1128/mBio.01965-16. pii: e01965-16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merrick MV, Eastwood MA, Anderson JR, Ross HM. Enterohepatic circulation in man of a gamma-emitting bile-acid conjugate, 23-selena-25-homotaurocholic acid (SeHCAT) J Nucl Med. 1982;23:126–130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wedlake L, A’Hern R, Russell D, et al. Systematic review: the prevalence of idiopathic bile acid malabsorption as diagnosed by SeHCAT scanning in patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;30:707–717. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.04081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Camilleri M, Busciglio I, Acosta A, et al. Effect of increased bile acid synthesis or fecal excretion in irritable bowel syndrome-diarrhea. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:1621–1630. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2014.215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pattni SS, Brydon WG, Dew T, et al. Fibroblast growth factor 19 in patients with bile acid diarrhoea: a prospective comparison of FGF19 serum assay and SeHCAT retention. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38:967–976. doi: 10.1111/apt.12466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22*.Borup C, Syversen C, Bouchelouche P, et al. Diagnosis of bile acid diarrhoea by fasting and postprandial measurements of fibroblast growth factor 19. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:1399–1402. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000476. This study provides further validation of the use of serum FGF-19 for the diagnosis of BAD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brydon WG, Nyhlin H, Eastwood MA, Merrick MV. Serum 7 alpha-hydroxy-4-cholesten-3-one and selenohomocholyltaurine (SeHCAT) whole body retention in the assessment of bile acid induced diarrhoea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1996;8:117–123. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199602000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lundåsen T, Gälman C, Angelin B, Rudling M. Circulating intestinal fibroblast growth factor 19 has a pronounced diurnal variation and modulates hepatic bile acid synthesis in man. J Intern Med. 2006;260:530–536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2006.01731.x. Erratum in: J Intern Med 2008; 263:459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kenyon SM, Lueke A, Meeusen JW, Camilleri M, Donato LJ. Measurement of 7α-hydroxy-cholestene-3-one in serum using LC-MS/MS for the screening of bile acid malabsorption in IBS-D. Presentation at The Association for Mass Spectrometry Application to the Clinical Lab; January 22–25, 2017; manuscript to be submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 26**.Fernández-Bañares F, Rosinach M, Piqueras M, et al. Randomised clinical trial: cholestyramine vs. hydroxypropyl cellulose in patients with functional chronic watery diarrhoea. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:1132–1140. doi: 10.1111/apt.13193. This is the only randomized controlled trial of the use of cholestyramine for the treatment of BAD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brydon WG, Walters JR, Ghosh S, Culbert P. Letter: hydroxypropyl cellulose as therapy for chronic diarrhoea in patients with bile acid malabsorption – possible mechanisms. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2016;44:306–307. doi: 10.1111/apt.13678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilcox C, Turner J, Green J. Systematic review: the management of chronic diarrhoea due to bile acid malabsorption. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;39:923–939. doi: 10.1111/apt.12684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bajor A, Törnblom H, Rudling M, et al. Increased colonic bile acid exposure: a relevant factor for symptoms and treatment in IBS. Gut. 2015;64:84–92. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Camilleri M, Acosta A, Busciglio I, et al. Effect of colesevelam on faecal bile acids and bowel functions in diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:438–348. doi: 10.1111/apt.13065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31**.Lin S, Sanders DS, Gleeson JT, et al. Long-term outcomes in patients diagnosed with bile-acid diarrhoea. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;28:240–245. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000541. This study suggests that patients with BAD will continue to need bile acid sequestrant long term for management of symptoms. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32**.Walters JR, Johnston IM, Nolan JD, et al. The response of patients with bile acid diarrhoea to the farnesoid X receptor agonist obeticholic acid. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:54–64. doi: 10.1111/apt.12999. This important study provides proof of concept that activated farnesoid X receptor and increasing FGF-19 can be a treatment of BAD. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Watson L, Lalji A, Bodla S, et al. Management of bile acid malabsorption using low-fat dietary interventions: a useful strategy applicable to some patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome? Clin Med (Lond) 2015;15:536–540. doi: 10.7861/clinmedicine.15-6-536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ryan KK, Tremaroli V, Clemmensen C, et al. FXR is a molecular target for the effects of vertical sleeve gastrectomy. Nature. 2014;509:183–188. doi: 10.1038/nature13135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]