Abstract

The aims of the study were to describe (1) the need for help as well as the use and costs of services of home help and/or home nursing (home care) and (2) to identify the variables associated with the use and costs of health and social care services. A total of 721 Finnish home-care clients were interviewed in 2001. The need for help was assessed by basic and instrumental activities of daily Living (ADL) and in terms of pain and illness, rest and sleep, psychosocial well-being and social and environment variables. The Anderson–Newman model was used to study predictors of use of services, including visits of home-care personnel and visits to the doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, laboratory and hospital. Weekly costs of services were calculated. Data were analyzed using multivariate analyses. The clients had poor functional ability and they needed help at least once a week with, on average, 6 out of 15 ADL functions, and 5 out of 13 items relating to pain and illnesses, rest and sleep, psychosocial well-being and social and environment items. The enabling and need variables, particularly the variables “living alone” and “perceived need for help”, were important predictors for the use of services. Social care constituted more than half of the average weekly costs of municipalities. The perceived need for help with basic ADL was associated with higher costs. To ensure the quality of life among home-care clients while keeping costs reasonable is a challenge for municipalities.

Keywords: Functional ability (ADL), Home-care services, Need for help, Use of services, Cost

Introduction

The focus of this paper is on older people receiving care at home in the form of home-care services. The main interests are in their ability to survive effectively at home and the costs accrued through the use of services. In 2003, 6.3% of elderly Finnish people, aged 65 or older, received home-care services regularly (Official Statistics of Finland 2003 and 2004). The number of these clients is continually growing because of the relative growth in the older population, with more and more elderly people living at home and requiring care (Population Statistics, Statistics Finland 2004). Further, the current Finnish policy on aging is to ensure that the greatest possible number of old people live independently in their homes, supported by their relatives and social and health-care services. This also reflects the wish of many elderly people (Hammar et al.1999).

The determination and structure of home-care services vary among studies and across countries (Andersson et al. 2005; Algera et al. 2004; Fortinsky et al. 2004; Modin and Furhoff 2002, 2004; Thome et al. 2003; Bruce et al. 2002; Lee and Mills 2000). Home-care services typically include a range of services, including skilled nursing care as well as home assistance and support services, such as personal care, cleaning and transfer services. Other services can include physical care and social work (Andersson et al. 2005).

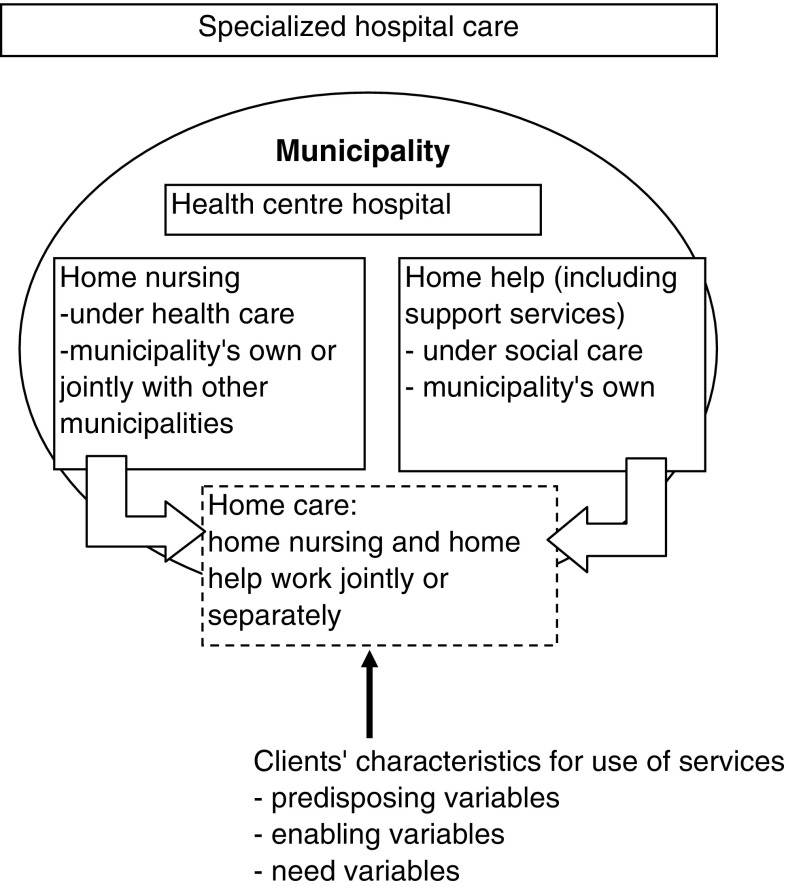

In Finland, municipalities are responsible for providing health and social services for elderly people (The Primary Health Care Act 66 1972; The Status and Right of Social Welfare Clients 812-2000). Home-care services are provided by home help service units (under social welfare) and home nursing units (under health care) either separately or together i.e., n unified home help and home nursing unit (Fig. 1) (see also Kauppinen et al. 2003, pages 21–23). Home-care services, especially home help, are nearly always provided as a long-term service. About half of the clients receive only home help services, a quarter solely home nursing and just under one-third both home help and home nursing services. About a quarter have more than one visit a day, and the proportion of those with a high service usage has increased between 1995 and 2003 (Kauppinen et al. 2003).

Fig. 1.

Simplified structure of home care in Finland and predictors for use of services according to Andersen–Newman model

In this study, home-care service includes home help and home nursing services. Home help services (under social care) include support services in addition to domestic help and personal/physical care provided by home helpers and home aids. Support services include meals-on-wheels, bathing, transferring, cleaning and electronic alarm service. Home nursing services (e.g., help with taking care of illness, medicines, treatment of wounds) are classified under health care and include visits by home nurses (i.e., district nurse, public health nurse, assistant nurse). Other health-care services (visits to doctor, physiotherapist, nurse, laboratory and hospital) and social service (social worker) are closely connected with home care and support clients’ survival at home.

According to previous studies, the majority of home-care clients are women, rather old, living alone with comorbidity and functional problems (Algera et al. 2004; Fortinsky et al. 2004; Kadushin 2004; van Campen and Woittiez 2003; Bruce et al. 2002; Lee and Mills 2000). The loss of function usually begins with those activities that are the most complex and least basic such as house cleaning (e.g., Dunlop et al. 1997). The most assistance is needed not only in instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) such as shopping and household chores, but also with basic hygiene (Grimmer et al. 2004; Laukkanen et al. 2001; Waters et al. 2001). Divan et al. (1997) showed that living alone predicted the use of home help, while low functional ability predicted the use of health-care services (see also Larsson et al. 2006; van Campen and van Gameren 2005; Kadushin 2004; van Campen and Woittiez 2003). Other factors found to be connected with the need for and use of services are female gender, self-rated health, comorbidity, recent inpatient care and feelings of loneliness (Bond et al. 2006; Fortinsky et al. 2004; Hellström et al. 2004; Lee and Mills 2000; Crets 1996; Wallace and Hirst 1996; Rannhoff and Laake 1995). However Algera et al.’s literature review (2004) revealed contradictory results on the association between client characteristics and need for care and the use of services. In some studies, age, female gender and living alone were associated with service use, but not in all. According to a study by Kadushin (2004), the presence of informal support delays the initiation of formal care until physical impairment of the care recipient is severe or the caregiver burden is high. Geerlings et al. (2005) found that informal care substituted for formal care, while in other studies informal and formal care complemented each other (Larsson and Silverstein 2004; Noro et al. 1999).

Less attention has been paid to studying the association between the use of services and items relating to dementia, psychosocial symptoms, social items and housing environment among home-care clients. It is already known that the consequences of comorbidity, pain and low functional ability are often helplessness and dependency, which can contribute to a higher frequency of anxiety, feelings of insecurity and mental disorders (Grimmer et al. 2004; Kvaal and Laake 2003; Ellefsen 2002; Hellsröm and Hallberg 2001; Kvaal et al. 2001; Rannhoff 1997). Janlöv et al. (2005) underline that when older people face the fact that they need help, it evokes anxiety as it means a new, unknown and potentially unpleasant situation (see also Pot et al. 2005). In Rannhoff and Laake’s study (1995), home help clients suffered from poor physical as well as psychosocial health (sleeping problems, loneliness). In Hellström et al.’s study (2004) elderly people who received help had lower health-related quality of life than people without help.

According to Larsson et al. (2006), dementia and depressive symptoms predicted the use of home help services (c.f. van Gameren and Woittiez 2005). Bruce et al. (2002) found that geriatric depression is twice as common in patients receiving home care as in those receiving primary care. In the study of Van Campen and Woittiez (2003), clients with only psychosocial disorders had a greater chance of being offered packages that included social support.

In addition, a safe and functional home environment is a prerequisite for survival at home. Vaarama (2004) pointed out that those who have physical obstacles in their home environment have twice the risk of having problems with functional ability compared to those living in well-adapted houses (see also Gitlin et al. 2001).

The costs of home-care services will increase due to aging of clients and the growing number of new clients in home care (c.f. Räty et al. 2003). It has been reported that home-care clients use a lot of other services, in addition to home care, such as visits to doctors and to the emergency department, as well as periods in institutions (Andersson et al. 2005; Smith et al. 2005; Modin and Furhoff 2002, 2004; Chang et al. 2003). According to Noro et al. (1999), women were more likely to use health-care services, but their share of total expenditure was lower than that of men. Poor health status, psychosomatic symptoms, difficulties in functional ability and living alone were significant predictors of higher care expenditure for old people. In a study by Fortinsky et al. (2004), the number of ADL and IADL dependencies showed a statistically significant linear and positive association with home-care expenditures. Unfortunately, the literature contains only very limited comparative data on the use of home-care services and their cost (c.f. Patel 2006). Several studies have been conducted outside Europe (Andersson et al. 2005; Fortinsky et al. 2004; Hollander et al. 2002; Jacobs 2001), where the service structure is different.

In this study we sought to identify the significant determinants of service use in home care, including variables of ADL as well as psychosocial well-being and environmental and social items. The Andersen–Newman model (Andersen and Newman 1973) was used as a framework for analysis. This model suggests that an individual’s use of health services is dependent on predisposing variables (such as age, gender), enabling variables (such as living alone) and need variables (such as illness and disability). Further, we sought to gain knowledge on how the costs of home-care services are born and divided across the health and social sector. The aims of the study were to describe the need for help and the use and costs of services among home-care clients, and to identify the variables associated with the use and costs of services.

Methods

The study belongs to a series of studies called “Integrated Services in the Practices of Home Care and Discharge” (Perälä et al. 2004). The first was a register-based study that studied the variance in care and discharge practices in Finnish municipalities and the effects of these variances on patients’ management at home. The second was a survey that explored the service structure in relation to discharge practices and home care. The results of these studies were used as a basis for formulating the selection criteria of the municipalities for this cross-sectional study, which acted as a pilot for a further experimental trial. For the sake of the experimental trial which followed this pilot, the sample size was based on a power calculation that predicted that 22 clusters (municipalities) with 35 clients in each were needed to achieve adequate results. Municipalities were chosen from the total number of municipalities in Finland (N=448 as of 2000) using criteria described in Hammar et al. 2007. The municipalities differed in terms of the number of inhabitants (10,000–96,000) and in the administrative structure of social and health care (home help and home nursing working together or separately). The elderly population (65+) in the study municipalities represented 14% of the total elderly Finnish population as well as 14% of the total number of home-care clients (65+) in 2001.

Data

Two kinds of data were used for the study: client and register data were compiled by means of a personal identification number for the client.

The client data (N = 770) were gathered from the pool of home-care clients from 22 municipalities, i.e., 35 clients/municipality. Clients aged 65 years or more, who lived at home and who regularly received home care services (i.e., home help and/or home nursing) and who had also had an inpatient hospital stay during the previous 6 months before being discharged back home were eligible for the study. Those clients who had a cancer or psychiatric primary diagnoses in the last hospital admission as well as clients who did not pass the Short Portable Mental Status test (SPMSQ; Pfeiffer 1975) were excluded so as to minimize the loss to follow-up and to improve the validity of interviews. The strict criteria for clients were based on the design of the experimental trial that followed this pilot study (Hammar et al. 2007). During a randomly chosen period, the interviewers (trained during one day of education + tight collaboration with researchers) selected eligible participants consecutively from the records of all home-care clients. Clients were interviewed in spring 2001 using a structured questionnaire. The diagnoses and current medications were obtained from medical records.

The register data were gathered from municipalities using the Sotka municipal database for social and health statistics for the year 2000. These data were mainly used to build a new “outpatient care orientation” variable (OPCO, see “Instruments”).

This study was approved by the Ministry of Social Affairs and Health of Finland and the Ethics Committee at the National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health [STAKES]. All clients gave a written consent for the study.

Instruments

The “outpatient care orientation” (OPCO) variable describes how a municipality developed its outpatient care (e.g., orientation to home nursing, home help, financial support to informal caregivers, residential housing, etc.; Rissanen and Noro 1999). The construction of this OPCO variable involved adjusting the following cross-municipality factors using a regression technique: the proportion of women in the population, the proportion of the population aged 65 years or older, the dependency ratio, the proportion of the population 65 years or more living in poorly or very poorly equipped housing and the proportion of the population 65 years or more living alone.

The municipality-related variables were the number of inhabitants (size) in a municipality, administrative structure of social and health-care services, and OPCO. Municipalities were divided into three groups according to the number of inhabitants: small (10,000–21,000), medium (21,001–35,000) and large municipalities (35,001–96,000). The unification status of the social and health administration structures was either unified (=1) or non-unified (=0). Scores of OPCO were re-classified into three groups: high (11–13), medium (9–10) and low (6–8).

The client’s need of help was evaluated according to three items: self-rated health, self-rated functional ability and perceived need of help. Self-rated health was assessed using a global five-point scale on the question “How do you feel about your health today?” which was grouped into three categories (good/fairly good, moderate and poor/fairly poor).

Functional ability (FA) was assessed by the Finnish version of the measure of activities of daily living (ADL), which includes both dimensions for basic activities of daily living (PADL) and instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (Jylhä 1985). Each ADL item yields values from 0 (no problems) to 3 (unable to manage). Managing in ADL was used in three ways. First, ADL was classified into three categories (good, moderate or poor), thus building a new variable, coping ability in daily life (CADL), using the procedure described by Jylhä (1985) (c.f. Noro 1998; Rissanen 1996). According to this procedure, CADL was classified as good if the client had no difficulties in any of the items in ADL. If the client had difficulties in one or more of the PADL items, then the CADL was classified as poor. Anything in between these two was classified as moderate. Secondly, based on the clients’ perceptions of the need for help, all ADL variables were re-classified to dummy variables (0,1) where zero indicated no, and one indicated yes (Table 2). Third, the two sum factors PADL and IADL, used in our regression models, were built (Tables 4, 5).

Table 2.

Percentage and odds ratio (OR) of home-care clients who had perceived need for help in ADL and other functions by gender and age adjusted

| ADL-functions (%) | Men ( n = 153–167) | Women (n = 501–537) | OR (95% Cl) | P |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PADL | ||||

| Walking between rooms | 13.3 | 10.3 | 0.83 (0.48–1.42) | 0.497 |

| Feeding oneself | 3.0 | 2.6 | 1.19 (0.41–3.44) | 0.751 |

| Dressing and undressing | 26.1 | 22.8 | 0.89 (0.60–1.35) | 0.586 |

| Getting in and out of bed | 11.4 | 8.8 | 0.81 (0.46–1.44) | 0.475 |

| Using the lavatory | 12.8 | 7.7 | 0.65 (0.36–1.14) | 0.133 |

| Washing and bathing | 52.1 | 57.7 | 1.19 (0.83–1.70) | 0.333 |

| IADL | ||||

| Moving outdoors | 39.2 | 47.3 | 1.32 (0.92–1.90) | 0.134 |

| Walking at least 400 m | 24.2 | 31.9 | 1.53 (0.99–2.35) | 0.054 |

| Using stairs | 24.5 | 34.4 | 1.61 (1.06–2.45) | 0.025 |

| Cutting own toenails | 67.5 | 71.3 | 1.17 (0.79–1.72) | 0.432 |

| Doing one’s own cooking | 68.7 | 68.0 | 0.91 (0.62–1.34) | 0.634 |

| Carrying a heavy load | 57.9 | 71.6 | 1.74 (1.19–2.54) | 0.004 |

| Doing light housework | 55.8 | 58.1 | 1.04 (0.76–1.49) | 0.825 |

| Doing heavy housework | 82.5 | 90.8 | 2.03 (1.22–3.38) | 0.006 |

| Banking, shopping | 69.8 | 79.9 | 1.61 (1.08–2.40) | 0.018 |

| n = 169–173 | n = 535–543 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Taking care of illnesses (%) | 80.0 | 85.0 | 1.55 (0.98–2.45) | 0.058 |

| Alleviating pain and aches (%) | 59.6 | 71.8 | 1.77 (1.22–2.55) | 0.002 |

| Getting sleep and rest (%) | 52.6 | 58.4 | 1.26 (0.89–1.79) | 0.197 |

| Psychosocial wellbeing (%) | ||||

| Anxiety, distress | 23.8 | 27.2 | 1.28 (0.85–1.99) | 0.231 |

| Insecurity feelings, fears | 11.0 | 20.7 | 2.06 (1.22–3.49) | 0.007 |

| Crises (death of spouse, child) | 9.8 | 20.9 | 2.51 (1.45–4.34) | 0.001 |

| Loneliness | 24.3 | 28.5 | 1.25 (0.84–1.87) | 0.276 |

| Social and environment items (%) | ||||

| Applying for social benefits and advantages | 52.1 | 55.9 | 1.24 (0.87–1.76) | 0.234 |

| Economical problems | 8.2 | 11.2 | 1.69 (0.90–3.16) | 0.099 |

| Lack of meaningful activities (hobbies) | 22.2 | 28.3 | 1.36 (0.90–2.06) | 0.140 |

| Limitations in living environment (doorsteps, lack of lifts) | 19.9 | 25.5 | 1.41 (0.91–2.16) | 0.120 |

| Lack or unworkability of aids | 33.5 | 45.3 | 1.60 (1.11–2.29) | 0.012 |

Table 4.

Variables associated with the use of home help, home nursing and support services (n= 691–699)

| Home help (yes = 1) | P | Home nursing (yes = 1) | P | Meals-on-wheels (yes = 1) | P | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | Adjusted OR | 95% Cl | ||||

| Constant | 0.23 | NS | 2.63 | NS | 1.77 | NS | |||

| Predisposing variables | |||||||||

| Age | 1.04 | 1.01–1.07 | 0.009 | 0.98 | 0.96–1.01 | NS | 1.03 | 0.98–1.03 | NS |

| Gender, male (female = 1)a | 0.82 | 0.52–1.32 | NS | 1.36 | 0.87–2.13 | NS | 1.40 | 0.89–2.20 | NS |

| Basic education, other (elementary = 1)a | 0.71 | 0.44–1.76 | NS | 0.42 | 0.23–0.79 | 0.007 | 0.80 | 0.42–1.52 | NS |

| Enabling variables | |||||||||

| Living arrangements, with others (alone = 1)a | 0.43 | 0.27–0.70 | 0.001 | 0.56 | 0.36–0.88 | 0.012 | 0.43 | 0.26–0.70 | 0.001 |

| Informal care during the previous week, no (yes = 1)a | 2.56 | 1.31–4.99 | 0.006 | 1.08 | 0.62–1.88 | NS | 0.80 | 0.46–1.40 | NS |

| Use of services, no (yes = 1)a | |||||||||

| Home help during the previous week | 2.34 | 1.51–3.62 | <0.001 | 0.37 | 0.24–0.57 | <0.001 | |||

| Home nursing during the previous week | 2.37 | 1.52–3.68 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.66–1.45 | NS | |||

| Doctor services after the last hospital stay | 1.49 | 0.98–2.26 | NS | 0.99 | 0.68–1.45 | NS | 0.81 | 0.55–1.19 | NS |

| Meals-of-wheels during the previous week | 0.35 | 0.23–0.55 | <0.001 | 0.98 | 0.66–1.45 | NS | |||

| Need variables | |||||||||

| Number of diagnoses | 0.98 | 0.97–1.10 | NS | 1.10 | 0.98–1.22 | NS | 0.96 | 0.86–1.07 | NS |

| Number of drugs | 1.03 | 0.87–1.10 | NS | 1.04 | 0.98–1.11 | NS | 0.97 | 0.92–1.03 | NS |

| Self-perceived health, good/moderate (poor = 1)a | 1.13 | 0.68–1.88 | NS | 1.52 | 0.96–2.41 | NS | 1.11 | 0.69–1.79 | NS |

| Functional ability (CADL), moderate/good (poor = 1)a | 0.55 | 0.35–0.86 | 0.009 | 0.61 | 0.40–0.93 | 0.022 | 0.74 | 0.48–1.13 | NS |

| Need for help, no (yes = 1)a | |||||||||

| Basic ADL | 0.52 | 0.31–0.87 | 0.012 | 1.12 | 0.72–1.74 | NS | 0.62 | 0.40–0.96 | 0.03 |

| Insrumental ADL | 0.25 | 0.06–1.02 | NS | 1.34 | 0.44–4.06 | NS | 0.78 | 0.20–3.01 | NS |

| Caring illnesses | 1.13 | 0.63–2.04 | NS | 0.38 | 0.23–0.63 | <0.001 | 1.06 | 0.63–1.80 | NS |

| Relieving pain | 0.82 | 0.51–1.32 | NS | 1.20 | 0.78–1.84 | NS | 1.83 | 1.19–2.80 | 0.006 |

| Getting sleep and rest | 1.05 | 0.68–1.63 | NS | 0.71 | 0.48–1.05 | NS | 0.92 | 0.62–1.37 | NS |

| Psychsocial wellbeing | 0.52 | 0.34–0.80 | 0.003 | 1.10 | 0.74–1.62 | NS | 1.07 | 0.72–1.58 | NS |

| Social and environment items | 0.87 | 0.53–1.40 | NS | 0.99 | 0.63–1.56 | NS | 0.67 | 0.42–1.07 | NS |

aThe value = 1 indicates the reference group

Table 5.

Results of linear regression analyses predicting the health and social care costs for all clients and for heavy users (>254€/week)

| Model for all clients (n = 626) | P | Model for heavy users (n = 195) | P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β coefficient | 95% Cl | β coefficient | 95% Cl | |||

| (Unstandardized) | (Unstandardized) | |||||

| Constant | 3.05 | 2.13 to 3.97 | <0.001 | 6.49 | 5.56 to 7.41 | <0.001 |

| Predisposing variables | ||||||

| Gender (female = 1, male = 0) | −0.11 | −0.29 to 0.07 | NS | −0.14 | −0.27 to −0.03 | 0.03 |

| Age | −0.001 | −0.06 to 0.01 | NS | 0.002 | −0.01 to 0.01 | NS |

| Enabling variables | ||||||

| Living alone (alone = 1, with others = 0) | 0.12 | −0.06 to 0.30 | NS | 0.1 | −0.04 to 0.24 | NS |

| Informal care (yes = 1, no = 0) | −0.04 | −0.22 to 0.14 | NS | −0.06 | −0.23 to 0.10 | NS |

| Use of services (yes = 1, no = 0) | ||||||

| Home help | 1.15 | 0.95 to 1.32 | <0.001 | 0.36 | 0.15 to 0.56 | <0.001 |

| Home nursing | 0.66 | 0.51 to 0.81 | <0.001 | 0.01 | −0.08 to 0.12 | NS |

| Visit to doctor | 0.18 | 0.03 to 0.33 | 0.022 | −0.02 | −0.13 to 0.10 | NS |

| Physiotherapist home visit | 0.83 | 0.50 to 1.16 | <0.001 | 0.12 | 0.01 to 0.35 | 0.04 |

| Meals-on-wheels | 0.23 | 0.07 to 0.39 | 0.004 | 0.03 | −0.09 to 0.14 | NS |

| Bathing service | 0.48 | 0.30 to 0.67 | <0.001 | 0.13 | 0.002 to 0.26 | NS |

| Cleaning service | −0.01 | −0.13 to 0.16 | NS | −0.10 | −0.22 to 0.03 | NS |

| Need variables | ||||||

| Perceived need for help (yes = 1, no = 0) | ||||||

| PADL functions | 0.29 | 0.12 to 0.46 | <0.001 | 0.17 | 0.004 to 0.33 | 0.045 |

| IADL functions | 0.12 | −0.30 to 0.53 | NS | −0.93 | −1.72 to −0.15 | 0.020 |

| Taking care of illnesses | 0.04 | −0.18 to 0.25 | NS | 0.01 | −0.16 to 0.19 | NS |

| Relieving pain | 0.07 | −0.10 to 0.24 | NS | −0.14 | −0.26 to −0.01 | 0.030 |

| Getting sleep and rest | −0.001 | −0.16 to 0.15 | NS | 0.10 | −0.01 to 0.21 | NS |

| Psychsocial wellbeing | −0.04 | −0.19 to 0.12 | NS | −0.05 | −0.16 to 0.27 | NS |

| Social and environment items | 0.18 | −0.03 to 0.36 | NS | 0.10 | −0.23 to 0.10 | NS |

| Adj. R2 | 50.4 | 20.0 | ||||

| F | 43.7 | 4.5 | ||||

In measuring the perceived need for help we expanded the concept of FA to include in addition to ADL also illnesses and pain, rest and sleep, psychological well-being and social and environment support (Vaarama 2004; Thome et al. 2003; Laukkanen et al. 2001; World Health Organization 2001). The perceived need for help was assessed with the question: “Do you need help in …?” with dichotomous variables constructed there from (no = 0, yes = 1).

The need for help in taking care of illnesses, in relieving pain and in getting rest and sleep were regarded as separate variables. The rest of the variables were built as sum factors (see Table 2). If the client perceived a need for help in any item of the sum factor it was coded 1 (yes). Cronbach’s α was used to assess the internal consistency of the sum factors. ADL was modified and summed to sum scores (1) PADL (six items summed, Cr α = 0.73) and (2) IADL (nine items summed, Cr α = 0.81) based on Jylhä (1985). From psychological well-being and social and environment support, two sum factors were formulated based on the literature (Roper et al. 2000) and on principal axis factor analysis. The sum factors were: (1) psychological well-being (four items summed, Cr α = 0.67 and (2) social and environment support (five items summed, Cr α = 0.57).

The use of health-care services included home nursing and physiotherapist’s home visits, visits to the doctor, nurse, physiotherapist, laboratory, outpatient clinic and emergency. The use of social services included visits by home help and support services (meals-on-wheels, transfer, bathing, cleaning, security telephone) and visits to the social worker. The use was measured by the number and the length (hours) of visits.

We derived data on service costs from questionnaire responses and calculated weekly costs. Unit costs were defined on the basis of a national standard cost study by Hujanen (2003), although the unit costs for transport, bathing and electronic alarm service were obtained from the annual account reports of two municipalities (Annual reports of Kangasala and Kuopio municipalities in Finland, year 2001). We also divided the costs into three classes based on the distribution of the total costs of visits. Those clients who belonged to the upper third in terms of costs were defined as “heavy users”, with the cut-off point for costs being € 254. (Note: the average costs to the municipality were different and higher; see Table 3).

Table 3.

Use and costs of services for clients receiving services during the week preceding the interview

| Services | Number of clients | Mean number of visits | Range | Unit cost per visit (€) | Weekly costs (€) mean | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health-care services | ||||||

| Home nursing visitsa | 409 | 1.67 | 0–14 | 40.30 | 67.30 | 9.07 |

| Visits to physicana | 258 | 0.14 | 0.03–2.80 | 75.70 | 10.60 | 1.43 |

| Visits to physiotherapistsa | 76 | 0.59 | 0.03–1.4 | 33.10 | 19.53 | 2.63 |

| Physiotherapist’s home visitsa | 29 | 1.45 | 0–4 | 101.90 | 147.76 | 19.92 |

| Visits to laboratorya | 322 | 0.18 | 0.03–4.2 | 5.10 | 0.92 | 0.12 |

| Visits to outpatient clinica | 109 | 0.11 | 0.04–0.54 | 147.20 | 16.19 | 2.18 |

| Visits to emergencya | 67 | 0.10 | 0.03–0.43 | 243.30 | 24.33 | 3.28 |

| Visits to nursea | 42 | 0.30 | 0.3–0.73 | 22.50 | 6.75 | 0.91 |

| Total costs | 293.37 | 39.54 | ||||

| Social-care services | ||||||

| Home help visitsa | 464 | 7.53 | 0–42 | 29.60 | 222.89 | 30.04 |

| Meals-on-wheelsa | 262 | 4.80 | 1–7 | 7.40 | 35.52 | 4.79 |

| Transfer servicesb | 113 | 1.37 | 1–5 | 16.90 | 23.15 | 3.12 |

| Bathing servicesb | 223 | 1.09 | 0–7 | 42.40 | 46.22 | 6.23 |

| Cleaning servicesa | 200 | 1.02 | 0–3 | 22.30 | 22.75 | 3.06 |

| Security telephone serviceb | 23 | 1.87 | 1–14 | 51.05 | 95.46 | 12.87 |

| Visits to social workera | 14 | 0.07 | 0.04–0.17 | 36.60 | 2.56 | 0.35 |

| Total costs | 448.55 | 60.46 | ||||

| Weekly costs total (mean) | 741.92 | 100.00 | ||||

aThe unit costs based on Hujanen’s study (2003)

bThe unit costs based on annual reports of municipalities

Demographic data on age, gender, education, marital status and living arrangements were also collected. We combined people who were married or cohabiting, as well as people with elementary and less education. Housing was re-classified into two groups (living alone and living with someone). The receipt of informal care was ascertained by asking: ‘Have you received help from spouse, other family members or friends during the previous week? (yes = 1, no = 0). A global dichotomous item was constructed indicating whether the client received informal care from any source (1) or did not receive any informal care at all (0).

Statistical analysis

The SPSS for Windows program (V.14) and the MLwin program (V.1.1) were used for statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics were used to characterize home-care clients and to assess these clients’ need for help and the use and costs of services. To assess differences between groups, a Chi-square test and non-parametric Man–Whitney U-test were used in cases where distributions were skewed. A t-test was used in case of a normal distribution.

Logistic regression analysis was used to identify variables significantly associated with the use of services. The “use of service” (home help, home nursing, meals-on-wheels, doctor) was a dependent, dichotomous variable (1 = yes, 0 = no). Where home help is the dependent variable, the “use of services” applies only to home nursing, meals-on-wheels and doctor, and similarly each of these variables in turn are used as the dependent variable. The explanatory variables were divided into three categories based on the Andersen–Newman model (Andersen and Newman 1973). Predisposing variables included “age”, “gender” and “basic education”. Enabling variables included “living alone”, “use of informal care” and “use of services”. Need variables included “self-perceived health”, “number of diagnoses and drugs”, “CADL” and “perceived need for help”. Marital status as an item was excluded from the model because there was a high statistical correlation with “living alone” and it was thought that “living alone” more self-evidently described a client’s need for help. All variables were classified or re-classified as dummy variables (0, 1), except age and number of diagnoses and drugs, which were continuous. Results are presented as odds ratios together with their significance level (95% Cl).

The ordinary least square (OLS) method was used to explore variables associated with costs. The costs of services were continuous variables. Log transformation of costs was used because of its skewed distribution. The explanatory variables were the same as in logistic regression.

Hierarchical regression models (component variance, Rasbash et al. 2001) were used to assess the differences between municipalities associated with the use and costs of services. We added municipality-related variables one by one to the client level variables, which were the same as that used in the logistic and OLS methods. The cluster effects in these models were weak (ICC varied between 2 and 4%) and not statistically significant.

Cases with missing values were excluded from analyses. Throughout, a value of P ≤ 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

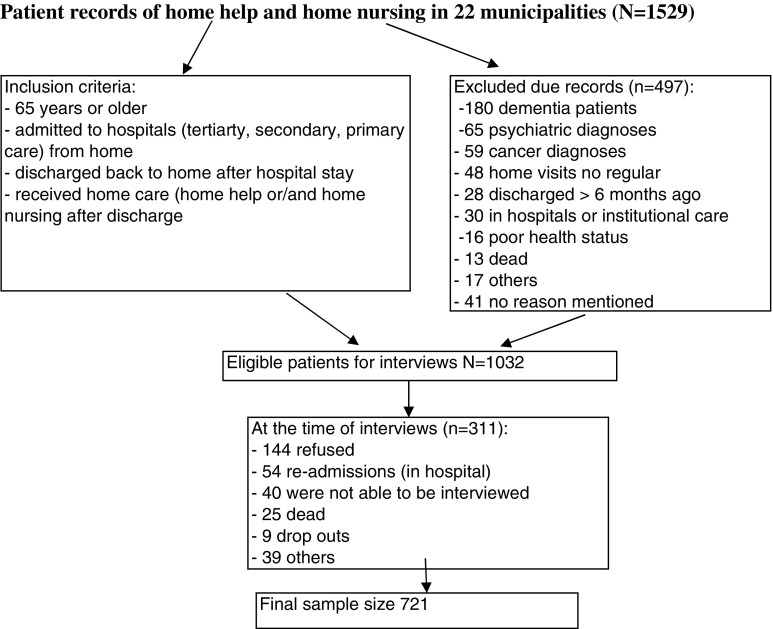

In total, 721 of 1,032 home-care clients were interviewed (Fig. 2). The time between the interview and hospital discharge varied from 3 weeks to 6 months. Clients were rather old (mean 80.2) and mostly women. They had multiple diseases and poor functional ability. Table 1 gives more detailed information on the client characteristics. The clients typically lived in their owner-occupied flats (64%). A fifth (21%) lived in sheltered housing. Most clients (82%) regarded their own home as the best place to live.

Fig. 2.

Flow of participants

Table 1.

Home-care clients’ characteristics

| n = 721 | |

|---|---|

| Gender, female (%) | 75.8 |

| Age, mean (sd) | 80.2 (7.01) |

| Marital status (%) | |

| Married | 20.3 |

| Widowed | 63.2 |

| Divorced | 6.5 |

| Single | 10.0 |

| Basic education, elementary or less (%) | 90.8 |

| Children, yes (%) | 81.6 |

| Help from Informal caregivers during the last week, yes (%) | 83.6 |

| Living arrangements (%) | |

| Alone | 74.0 |

| With spouse | 19.0 |

| With another person | 7.0 |

| Health (%) | |

| Poor | 21.3 |

| Moderate | 46.8 |

| Good | 31.9 |

| Functional ability (CADL), poor (%) | 63.0 |

| Poor eyesight, yes (%) | 34.1 |

| Reduced hearing, yes (%) | 47.0 |

| Number of diagnoses, mean (range) | 3.7 (0–10) |

| Number of medications, mean (range) | 7–8 (0–16) |

| Use of services during the previous week, yes (%) | |

| Home help | 67.1 |

| Home nursing | 59.7 |

| Meals-on-wheels | 38.4 |

| Use of doctor services during the last hospital stay, yes (%) | 38.4 |

Need for help

More than half of the clients needed daily help and almost all (93%) at least once a week. During the previous week, more than half (57%) had received help from their children, and 16% from their spouses or other informal caregivers. The clients needed weekly help on average with 6 out of 15 ADL functions (mean 5.6), particularly in IADL functions. The clients also perceived a need for help on average with 5 out of 13 variables (mean 5.3) related to dealing with illnesses, alleviating pain, getting sleep and rest, supporting psychological well-being and environments. Women tended to need more weekly help in almost all items compared to men (Table 2). Men, in turn, needed more help on a daily basis (63 vs. 57%, P = 0.027).

Use of services

Two-thirds (67%) received publicly provided home help and/or home nursing services during the week preceding the interview. Home help services were the most frequently used (mean number of visits 7.5 and mean number of hours 5.9), followed by meals-on-wheels (mean number of visits 4.8) and home nursing (mean number of visits 1.7 and mean number of hours 2.1). Visits to medical laboratories and doctors were also common (Table 3). Private services (private home nursing, home help and doctor) were used rarely. Gender, in general, was not associated with the use of services. Further, we found no association between the use of services received and the length of time from hospital discharge to interview data collection.

We created four separate logistic regression models for each dependent variable: use of home help, home nursing and meals-on-wheels service and visit to a doctor. Most variables were found to be associated with the use of home help. “Living alone” was significantly associated with the use of home help, home nursing and meals-on-wheels. “Informal care” was significantly associated only with the use of home help, thus the probability of receiving home help decreased if the clients received informal care. Use of home help and home nursing had a negative association with each other, while use of home help and meals-on-wheels had a positive association. Perceived need for help in basic ADL increased the probability of using home help as well as meals-on-wheels services. Regarding the perceived need for help with other aspects, associations with use of services were different depending on the service in question (Table 4).

The fit of models were not improved by combining client level and municipality level variables in the component variance models. Moreover, we could not find any municipality-related variables that were associated with the use of services.

Cost of services

During the week preceding the interview, over 6,000 home visits took place, with a total cost of € 164,000 (range € 8–1,423). Following their previous hospital stay, clients also visited outpatient care services more than 2,200 times with total costs of € 106,000 (range € 5–3,515). Table 3 shows that the average weekly costs of social and health-care visits for municipalities were € 740, with the costs of social care constituting more than half. The home help visits constituted a third of weekly costs and physiotherapist’s home visits one-fifth (Table 3). One-third of home-care clients used a majority of the services and caused the greatest proportional costs for the municipality.

The linear regression models showed that the use of most of the services were significant factors that increased the costs for the municipality, as well as the perceived need for help in PADL. We also built a separate model for heavy users (average cost per client was € 254 or more). In this model, among the services, the use of home help was an important factor associated with costs. The need for help in PADL was positively associated with costs, whereas the need for help in IADL and in relieving pain were negatively associated with costs (Table 5). No other perceived needs were associated with costs. We also checked separately if the “perceived need for help in economic problems” was associated with the use and cost of services, but no association was found.

We found some differences between heavy users and others when we compared groups using cross-tabulation (results are shown only in the text). A larger proportion of heavy users compared to others perceived their FA as poor (76 vs. 57%; P < 0.001), needed daily help (96 vs. 40%; P < 0.001) and used home-care services, especially home help services (92 vs. 57%; P < 0.001). Heavy users, more often than others, did not live alone, but a large proportion had a spouse with poor health status (53 vs. 29%; P = 0.018) and they did not get help from their children as often as others (35 vs. 28%; P = 0.043).

We did not find any significant association between costs and municipality-related factors when client-level variations were adjusted using the multilevel regression technique (component variance model).

Discussion

Home-care clients needed help in ADL functions as well as in taking care of illnesses and alleviating aches and pain. The enabling and need variables, particularly the variables “living alone” and “perceived need for help” with several items, were important predictors for use of services. The average weekly costs of social and health-care visits for municipalities were € 740, with the costs of social care constituting more than half. The perceived need for help in PADL was associated with higher costs.

In keeping with the existing literature (e.g., Fortinsky et al. 2004; Kadushin 2004; Modin and Furhoff 2004; van Campen and Woittiez 2003) in relation to home-care clients, our study population included mostly older women living alone who had many comorbidities and declining FA. Clients cope fairly well in PADL functions, while they need help in applying for social benefits as well as with IADL functions. These findings support previous studies (Grimmer and Moss 2004; Dunlop et al. 1997) that showed that loss of function begins with those activities that are the most complex and least basic, and that a decline in FA increases IADL dependency. Women seemed to need more help in almost all ADL items. The result that men needed more help on a daily basis (e.g., in cooking) may result from these tasks being traditional women’s tasks.

In this study, taking care of illnesses, alleviating pain, getting sleep and rest, anxiety and loneliness were significant areas where home-care clients needed help, particularly female respondents. When clients responded with a “yes” to the question of receiving help in managing their illness, we could not say if it was received from a professional or from an informal caregiver. This interesting issue needs deeper investigation.

The results regarding perceived need of help in psychosocial well-being are not unexpected, as declining FA is associated with poorer psychological well-being (Voutilainen and Vaarama 2005; World Health Organization 2001). It is well known (cf. Ellefsen 2002; Kvaal et al. 2001; Rannhoff 1997) that a frail elderly person, who has a dependency on others, may experience feelings of insecurity, anxiety and distress for the future. On the other hand, Pot et al. (2005) found that transitions in professional care may increase older adults’ depression symptoms. But, the large number in our sample who needed help in these areas was a rather surprising finding. Another explanation may be that fears and insecurity are dominant in home care, where increasingly frail and old people live alone at home. Sometimes, depression, fears and insecure feelings may appear as aches and pains and in a higher use of services. The question is: how can we recognize those clients and give support based on their needs?

Enabling variables, particularly “living alone”, were important predictors for the use of services. Use of home nursing and home help, two other enabling variables, had a negative association; when a client received home help services, his/her probability of using home nursing decreased and vice versa. This result is in line with Finnish health policy data where just under a third of home-care clients received both home help and home nursing services. Informal care was negatively associated with home help and seems to be a substitute for home help, or vice versa. Similar results have been found in other studies (Geerlings et al. 2005; Kadushin 2004) although Noro et al. (1999) and Larsson and Silverstein (2004) have pointed out that home care was supplemental to informal care. In Pot et al.’s study (2005) the most common type of care among older Dutch people was informal care followed by professional home care. In our study, the great majority (84%) received informal care (from spouses and children), and the most frequently used services were home help services (67%) followed by meals-on-wheels and home nursing (c.f. Fortinsky et al. 2004; Modin and Furhoff 2004). In Finland, like in other countries, informal care has an important role in supporting older people’s managing at home (Finne-Soveri et al. 2006). It has been estimated that without support from informal caregivers, a large proportion of these elderly people would be cared for in institutions.

Need variables also played an important role in predicting the use of services (c.f. van Gameren and Woittiez 2005; Kadushin 2004; van Campen and van Gameren 2004). An association between the use of home nursing and the need for help in dealing with illnesses is quite expected, because home nursing aims at caring for illnesses and pain, while home help is focused on assistance with ADL functions. In our study, the need for help in psychosocial well-being was associated with the use of home help, but not with the use of home nursing (c.f. van Campen and Woittiez 2003). A large part of home care is given through collaboration with home help, resulting in more frequent home visits than home nursing, thus being a possible reason for this association. Older people do not always need professional care, but someone to listen and be present. These findings taken together raise the question of who is taking care of this expanding group in home care. Does home care sufficiently recognize the needs of psychosocial support and thereby arrange help from other sectors (voluntary, private sector) or from informal caregivers? Taking into consideration that most of the clients in our study lived alone and the probability of receiving informal care decreased if the clients used home help, it would seem that many clients do not have dear ones (close relatives or friends). The solution to this problem is not straightforward and needs deeper investigation.

A majority of clients used some services, but a third of them account for the majority of costs to the municipality (cf. Noro et al. 1999). A slightly inconsistent result was the decrease in costs found when heavy users were in need of help in IADL. One explanation may be that informal caregivers help clients in these items. On the other hand, a larger proportion of heavy users had a spouse with poor health status and they did not receive help from their children as often as others. Another reason might be a high correlation between PADL and IADL items, giving rise to unstable models and thus confusing the results. Based on this study, we could not give any clear explanation for these contradictory results and so it demands further specific research.

It is understandable that social care costs comprise over half of the average weekly cost of municipalities because the majority of respondents use home help and support services. Although one visit is quite cheap, a large number of visits during a week increase the cost. On the other hand, expensive visits to an outpatient clinic or to an emergency room were not common. It might be a better alternative, both for the elderly people and the municipalities, if an increasing number of home-care visits could prevent or reduce the number of visits to emergency rooms. Among health-care services, the physiotherapist’s home visit incurred the highest cost for a municipality. One-quarter of the study sample needed help in managing their living environments (e.g., coping with doorsteps). Further, many reported a lack of aid to help them live independently at home (cf. Vaarama 2004; Gitlin et al. 2001). All are items that require the physiotherapist’ expertise. One home visit may seem expensive, but if those visits can prevent or at least delay the entry into institutional care then the visits will pay for themselves in the long run.

Receiving home-care services may not always depend on the clients themselves, but can be related to the municipality’s ability to take care of its citizens. The aim of the Finnish aging policy is to support all kinds of clients irrespective of the socioeconomic status or the municipality in which they live. The size or administrative structure of the municipality or economic problems were not associated with the use and cost of services, which might reflect a situation where clients received services based on their needs and where home care was distributed equally over the whole country. Clearly, additional evidence on this subject is required before we can draw any strong conclusions. More studies are needed to ensure the equity of clients and the quality of care.

There are some limitations to our study. First, when measuring the perceived need for help in psychological well-being and in social and environment variables, we built two sum factors. The reliability of the sum factors was quite low, but the classification of sum factors was based on previous literature (Roper et al. 2000) and factor analyses. The factors behaved well and were feasible in regression models, but only the psychological well-being variable was able to prove statistical significance. Second, calculating and comparing health and social care costs is difficult, as there are different ways to construct costs among municipalities and among countries (c.f. Patel 2006). Further, it has to be taken into account that in Finland the relative wages in health and social care are below the levels of other countries (c.f. OECD 2005) and that is why the unit costs of services may seem low. We derived unit costs from a national standard costs study by Hujanen (2003), so the costs of these services are comparable across Finland. Costs, such as transport, cleaning and electronic alarm services were taken from the annual accounts of two municipalities. These unit costs were then applied to all study municipalities. When conclusions are drawn, attention should be paid to the fact that the original costs of those services may vary among municipalities. The results, however, give a picture of how costs relating to the home-care population described here are borne and divided between health and social care. Third, our data may have been biased in the population distribution, because the sample consisted predominantly of rather old, frail, and female persons. Further, the sample was restricted to persons without dementia or cognitive impairments or acute psychiatric or cancer diagnoses. In Finland in 2003, 9.1% of all home-care clients had a dementia diagnosis (Statistical summary 2007; Finne-Soveri et al. 2006). It has been reported that depression, dementia and other cognitive impairments are important predictors for the use of services (Larsson et al. 2006; Pot et al. 2005; Bruce at al. 2002). As a consequence, it is not possible to draw any conclusions, based on our data, about the associations between these important variables and the use and cost of services. Future research that is able to include these client groups in the study population will give a more realistic picture of costs and services.

The strengths of this paper include the fact that the study municipalities were spread across the country and varied in the number of inhabitants and the administrative structure of health and social care. The large number of respondents (population in study municipalities represented 14% of the elderly population in Finland and 14% of home-care clients 65+) constitute a sufficient basis to draw conclusions about the need for and the use and costs of services among those specific home-care clients who have had a hospital discharge during the previous 6 months and who do not have dementia and other cognitive impairments or acute cancer. Those clients who did not participate because of poor health were not likely to have received less service than our study population. Nevertheless, as research into care practices takes place in the context of the local health and social service system, the results must be carefully scrutinized before adapting to other countries or contexts.

Conclusions

Home-care clients need significant help in ADL functions as well as in maintaining their psychosocial well-being and in creating a workable housing environment. Based on the Andersen–Newman model, the enabling variables, particularly “living alone”, and several perceived need variables were important and associated with the use and cost of home care services. It is expected that the demographics of the home-care clientele covers more people living alone, with poor functional ability as well as cognitive impairments and psychosocial problems. The clients with poor functional and cognitive ability and psychosocial problems are also likely to be “high-cost clients” in home care. To ensure the quality of life among all home-care clients, while keeping costs reasonable, is a challenge to municipalities, and clearly more studies in this area are needed.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the Development Centre for Welfare and Health (STAKES) and doctoral programmes in public health at the Helsinki and Tampere universities.

Contributor Information

Teija Hammar, Phone: +358-93-9671, FAX: +358-93-9672227, Email: teija.hammar@stakes.fi, Email: marja-leena.perala@stakes.fi.

Pekka Rissanen, Phone: +358-33-5516897, Email: pekka.rissanen@uta.fi.

References

- Algera M, Francke AL, Kerkstra A, van der Zee J. Home-care needs of patients with long-term conditions: literature review. Integrative literature reviews and meta-analyses. J Adv Nurs. 2004;46(4):417–429. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03031.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen R, Newman J. Societal and individual determinants of medical care utilization in the United Sates. Milbank Fund Q. 1973;51:95–124. doi: 10.2307/3349613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersson MA, Clarke M, Helms L, Foreman M. Hospital readmission from home health care before and after prospective payment. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2005;37(1):73–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.2005.00001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annual reports of Kangasala and Kuopio municipalities in Finland, year 2001

- Bond J, Dickinson HO, Matthews F, Jagger C, Brayne C. Self-rated health status as a predictor of death, functional and cognitive impairment: a longitudinal cohort study. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:193–206. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0039-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce M, McAvay G, Raue PJ, Brown E, Meyers B, Keohane D, Jagoda D, Weber C. Major depression in elderly home health-care patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(8):1367–1374. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.8.1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang S-H, Chiu Y, Liou I-P. Risks for unplanned hospital readmission in a teaching hospital in southern Taiwan. Int J Nurs Pract. 2003;9(6):389–395. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-172X.2003.00443.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crets S. Determinants of the use of ambulant social care by the elderly. Soc Sci Med. 1996;43(12):1709–1720. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(96)00060-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Divan S, Berger C, Manns EK. Composition of the home-care service package: predictors of type, volume, and mix services provided to poor and frail older people. Gerontologist. 1997;37(2):169–181. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.2.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DD, Hughes SL, Manheim LM. Disability in activities of daily living: patterns of change and a hierarchy of disability. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(3):378–383. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.87.3.378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellefsen B. Dependency as disadvantage—patients’ experiences. Scand J Caring Sci. 2002;16:157–164. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-6712.2002.00073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finne-Soveri H, Björkgren M, Vähäkangas P, Noro A (eds) (2006) Kotihoidon asiakasrakenne ja hoidon laatu - RAI-järjestelmä vertailukehittämisessä. (Quality and case-mix among elderly clients in home care. Benchmarking with RAI) STAKES, Helsinki, Finland

- Fortinsky R, Fenster J, Judge J. Medicare and medicaid home health and medicaid waiver services for dually eligible older adults: risk factors for use and correlates of expenditures. Gerontologist. 2004;44(6):739–749. doi: 10.1093/geront/44.6.739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geerlings S, Pot A, Twisk J, Deeg D. Predicting transitions in the use of informal and professional care by older adults. Ageing Soc. 2005;25:111–130. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002740. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gitlin L, Mann W, Tomit M, Marcus S. Factors associated with home environmental problems among community-living older people. J Disabil Rehabil. 2001;23(20):777–787. doi: 10.1080/09638280110062167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimmer K, Moss J, Falco J. Experience of elderly patients regarding independent community living after discharge from hospital: a longitudinal study. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16(6):465–472. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar T, Perälä M-L, Rissanen P. The effects of integrated home care and discharge practice on functional ability and health-related quality of life: a cluster-randomised trial among home-care patients. Int J Integr Care. 2007;27:1568–4156. doi: 10.5334/ijic.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammar T, Raatikainen R, Perälä M-L. Sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelut tulevaisuudessa: 60–65-vuotiaiden odotukset palveluista 80-vuotiaana. (Social and health-care services in the future: 60–65 years old inhabitants’ expectation of services as 80 years old) Gerontologia. 1999;13(4):189–199. [Google Scholar]

- Hellström Y, Persson G, Hallberg IR. Quality of life and symptoms among older people living at home. JAdv Nurs. 2004;48(6):584–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström Y, Hallberg I. Perspectives of elderly people receiving home help on health care and quality of life. Health Soc Care Community. 2001;9(2):61–71. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2524.2001.00282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollander M, Chappell N, Havens B, McWilliam C, Miller JA (2002) Study of the costs and outcomes of home care and residential long-term care services. Substudy 5. A report prepared for the Health Transition Fund, Health Canada. http://www.homecarestudy.com

- Hujanen T (2003) Terveydenhuollon yksikkökustannukset Suomessa vuonna 2001. (Unit cost of health care service in Finland 2001) STAKES, Themes 1, Helsinki, Finland

- Unit cost of health-care services in Finland 2001(2003) STAKES, Aiheita

- Jacobs P (2001) Costs of acute care and home-care services. Substudy 9. A report prepared for the Health Transition Fund, Health Canada. http://www.homecarestudy.com

- Janlöv AC, Hallberg IR, Petersson K. The experience of older people of entering into the phase of asking for public home help—a qualitative study. Int J Soc Welfare. 2005;14:326–336. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-6866.2005.00375.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jylhä M (1985) Oman terveyden kokeminen eläkeiässä. (Self-perceived health of the elderly) Acta Universitatis Tamperensis ser A vol 195. Doctoral thesis, University of Tampere, Tampere, Finland

- Kadushin G. Home health-care utilization: a review of the research for social work. Health Soc Work. 2004;29(3):219–248. doi: 10.1093/hsw/29.3.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen S, Forss A, Säkkinen A, Voutilainen P, Noro A (eds) (2003) Ikääntyneiden sosiaali-ja terveyspalvelut 2002. Suomen virallinen tilasto (SVT) [Care and services for older people 2002. Official Statistics of Finland, (SVT)]. STAKES, Helsinki, Finland (in Finnish, English and Swedish)

- Kvaal K, Laake K. Anxiety and well-being in older people after discharge from hospital. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44(3):271–277. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvaal K, Macijauskiene J, Engedal K, Laake K. High prevalence of anxiety symptoms in hospitalized geriatric patients. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2001;16:690–693. doi: 10.1002/gps.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson K, Thorslund M, Kårenholt I. Are public care and services for older people targeted according to need? Applying the Behavioural Model on longitudinal data of a Swedish urban older population. Eur J Ageing. 2006;3:23–33. doi: 10.1007/s10433-006-0017-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson K, Silverstein M. The effects of marital and parental status on informal support and service utilization: a study of older Swedes living alone. J Aging stud. 2004;18:231–244. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2004.01.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laukkanen P, Karppi P, Heikkinen E, Kauppinen M. Coping with activities of daily living in different care settings. Age Ageing. 2001;30:489–494. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.6.489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee TT, Mills ME. Analysis of patient profile in predicting home care resource utilization and outcomes. J Nurs Adm. 2000;30(2):67–75. doi: 10.1097/00005110-200002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modin S, Furhoff AK. Care by general practitioners and district nurses of patients receiving home nursing: a study from suburban Stockholm. Scand J Prim Care. 2002;20:208–212. doi: 10.1080/028134302321004854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Modin S, Furhoff AK (2004) The medical care of patients with primary care home nursing is complex and influenced by non-medical factors: a comprehensive retrospective study from a suburban area in Sweden. BMC Health Services Research 4(22). http://biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/4/22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- National Research and Development Centre for Social Welfare and Health (2000) The Finnish care registers for social and welfare and health (HILMO). STAKES, Helsinki, Finland

- Noro A, Häkkinen U, Laitinen O. Health services research. Determinants of health service use and expenditure among the elderly Finnish population. Eur J Public Health. 1999;9:174–180. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/9.3.174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noro A (1998) Long-term institutional care among Finnish elderly population. Trends and potential for discharge. STAKES, research report 87. Doctoral thesis, Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy, Jyväskylä, Finland

- OECD (Organisation for economic co-operation and development) Reviews of Health Systems. Finland. OECD 2005. STAKES, Helsinki, Finland

- Patel A (2006) Conducting and interpreting multi-national economic evaluations: the measurement of costs. In: Curtis L, Netten A (eds) Unit costs of health and social care. Personal Social Services Research Unit, University of Kent, UK, pp 9–22. http://www.pssru.ac.uk/uc/uc2006contents.htm

- Pfeiffer E. A short portable mental status questionnaire for the assessment of organic brain deficit in elderly patients. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1975;23(10):433–441. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1975.tb00927.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Primary Health Care Act 66/1972, Helsinki, Finland (in Finnish). Accessed http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/1972/19720066

- Population Statistics, Statistics Finland (2004)

- Pot A, Deeg D, Twisk J, Beekman A, Zarit S. The longitudinal relationship between the use of long-term care and depressive symptoms in older adults. Gerontologist. 2005;45:359–369. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.3.359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rannhoff AH. Activities of daily living, cognitive impairment and other psychological symptoms among elderly recipients of home help. Health Soc Care Community. 1997;5:147–152. [Google Scholar]

- Rannhoff AH, Laake K. Health and functional among elderly recipients of home help in Norway. Health Soc Care. 1995;3:115–123. [Google Scholar]

- Rasbash J, Browne W, Goldstein H, Yang M, Plewis I, Healy M, Woodhouse G, Draper D, Langford I, Lewis T (2001) A user’s guide to MLwin. Version 2.1c. Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Institute of Education, University of London, UK

- Ikääntyvien potilaiden hoito- ja kotiuttamiskäytännöt. Rekisteripohjainen analyysi aivohalvaus-ja lonkkamurtumapotilaista (1999) In: Rissanen P, Noro A (eds) Hospital care and discharge practices of elderly patients—register-based analysis. STAKES, Themes 44, Helsinki, Finland.

- Rissanen P (1996) Effectiveness, costs and cost-effectiveness of hip and knee replacements. STAKES, Research report 64 (doctoral thesis) Gummerus Kirjapaino Oy, Jyväskylä, Finland

- Roper N, Logan W, Tierney AJ. The Roper Logan Tierney. Model of nursing. Based on activities of living. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Räty T, Luoma K, Mäkinen E, Vaarama M. The factors affecting the use of elderly care and the need for resources by 2030 in Finland. Governments Institute for Economic Research (VATT) -research reports 99. Helsinki, Finland: Oy Nord Print Ab; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Smith A, Carusone S, Willison K, Babineu T, Smith SD, Abernathy T, Marrie T, Loeb M (2005) Hospitalization and emergency department visits among seniors receiving homecare: a pilot study. BMC Geriatr 5:9. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2318/5/9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Sotka -municipal database for social and health statistics in Finland, year 2000. Accessed http://uusi.sotkanet.fi/portal/page/portal/etusivu (in Finnish and English)

- Statistical summary (2007) Dementia-asiakkaat sosiaali- ja terveyspalvelujen piirissä 2001, 2003 ja 2005 (Clients with dementia in health and social services, years 2001, 2003 and 2005) Tilastotiedote 20/2007, STAKES. http://www.stakes.fi/tilastot/dementia [in Finnish]

- The Status and Right of Social Welfare Clients 812/2000, Helsinki, Finland. Accessed http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2000/20000812 (in Finnish)

- Thome’ B, Dykes AK, Hallberg I. Home care with regard to definition, care recipients, content and outcome: systematic literature review. J Clin Nurs. 2003;12(6):860–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2702.2003.00803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaarama M (2004) Ikääntyneiden toimintakyky ja hoivapalvelut - nykytila ja vuosi 2015. Teoksessa: Valtioneuvoksen kanslia. Ikääntyminen voimavarana. Tulevaisuusselonteon liiteraportti 5. Valtioneuvoston kansalian julkaisusarja 33/2004. Valtioneuvoston kanslia, Helsinki. (The functional ability and services of the aging people—the present situation and year 2015. Prime Minister’s Office publications 33/2004, Helsinki]

- Van Campen C, van Gameren E. Eligibility for long-term care in The Netherlands: development of a decision support system. Health Soc Care Community. 2004;13(4):287–296. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00546.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Campen C, Woittiez I. Client demand and the allocation of home care in the Netherlands. A multinomial logit model of client types, care needs and referrals. Health Policy. 2003;64:229–241. doi: 10.1016/S0168-8510(02)00156-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Gameren E, Woittiez I. Transitions between care provisions demanded by dutch elderly. Health Care Manage Sci. 2005;8:299–313. doi: 10.1007/s10729-005-4140-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voutilainen P, Vaarama M (2005) Toimintakykymittareiden käyttö ikääntyneiden palvelutarpeen arvioinnissa. Stakes raportteja 7/2005. (Use of measures of functional ability in the assessment of service needs among older people. STAKES, reports 7/2005]

- Wallace DC, Hirst PK. Community-based service use among the young, middle, and old . Public Health Nurs. 1996;13(4):286–293. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1446.1996.tb00252.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waters K, Allsopp D, Davidson I, Dennis A. Sources of support for older people after discharge from hospital: 10 years on. J Adv Nurs. 2001;33(5):575–82. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization (2001) International classification of functioning, disability and health (ICF). WHO, Geneva. www3.who.int/icf/icftemplate.cfm