Abstract

The article addresses the strength and character of intergenerational family solidarity under different family cultures and welfare state regimes in order to answer the following two questions: (1) Is intergenerational solidarity stronger under the more collectivist southern family tradition than under the more individualist northern tradition? (2) Is more generous access to social care services a risk or a resource for family care? These questions are explored with data from the OASIS project, a comparative study among the urban populations aged 25+ (n=6,106) in Norway, England, Germany, Spain, and Israel. The findings indicate that the welfare state has not crowded out the family in elder care, but has rather helped the generations establish more independent relationships. Intergenerational solidarity is substantial in both the northern and southern welfare state regimes, and seems to vary in character more than in strength.

Keywords: Intergenerational solidarity, Family–welfare state balance, Cross-national comparisons, Elder care

Introduction

The focus here is on family solidarity and how responsibilities for elder care should be divided between the family, the welfare state, and others. This is hardly a new theme, but one which has renewed relevance due to the present pressures of population ageing in a climate that constrains welfare state spending. Population ageing adds burdens to families and welfare states, the two major pillars of support in old age.

A concern for family solidarity is an old story, and so to speak a loyal companion during history and possibly eternally linked to generational shifts. Family concerns are often expressed as some form of nostalgia; as a longing back to some noble past when people and families really cared. Substantial majorities in European countries feel that families were more caring in the past. Southern Europeans perhaps feel this even more so than northern Europeans do (Daatland 1997). Present problems are often blamed on modernity and individualism, i.e. that modern man has grown narcissistic and self-centered. Some see the welfare state as the villain because it may have reduced the necessity, and therefore the motivation, for solidarity. Is there a ‘moral risk’ in a generous welfare state (Wolfe 1989)?

Concern for the welfare state is not new either, and has been increasing in recent years. The borders between public and private responsibility are redrawn. Does public responsibility and spending need to be restrained in order to save the financial foundation of the welfare state and possibly even the moral standard of society? Are there good reasons for these concerns? Can we indeed have trust in family solidarity? Is the welfare state a resource or a risk for family elder care? These were among the questions that motivated the OASIS project.

The study and research questions

The OASIS 1 study is a comparative study in five countries with different welfare models and family traditions: Norway, England, Germany, Spain, and Israel. They are located along a north-south axis, and also along a dimension from a presumably more collectivist family tradition in the south to a more individualist tradition in the north (Reher 1998). They also represent different welfare state regimes—social democratic Norway, liberalist England, conservative (corporatist) Germany, and conservative (southern) Spain (Esping-Andersen 1990, 1999; Ferrera 1996). Israel’s welfare state regime is best described as mixed.

The OASIS countries were thus selected to represent different contexts and opportunity structures for family life and elder care. They are confronted by similar challenges, but are inclined towards different solutions. Of particular interest here is that Germany and Spain are familialist welfare states that tend to favour family responsibility and give the state a subsidiary (Germany) or even a residual (Spain) role. These two countries have legal obligations for adult children towards elderly parents and relatively low levels of social care services like elder care, that operate in areas that are by tradition a family responsibility (Table 1). They may, however, have high levels of medical services. England and Norway have individualist social policies, no legal obligations between adult family generations, and higher levels of social care services. When these two countries also have high employment rates for women and comparably high fertility rates, this may be part of the same story. Younger generations in England and Norway probably find it easier to combine work with child raising than do younger generations in Germany and Spain. In the mixed Israeli welfare state regime, there are legal family obligations as in Spain and Germany, but also high service levels like in Norway. The high Israeli fertility rate is probably explained by Jewish family traditions and political conflicts in the region.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the five countries as welfare state regimes

| Norway | England | Germany | Spain | Israel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welfare state regime | Social-democratic | Market-liberal | Conservative/corporatist | Conservative/southern | Mixed |

| Legal family obligation? | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Social care service level | High | Medium | Low | Low | High |

| Female work rate | 72% | 62% | 61% | 45% | 55% |

| Fertility | 1, 7 | 1, 6 | 1, 3 | 1, 1 | 2, 7 |

Data about family values and practices were in OASIS collected via surveys (personal, face-to-face interviews) among random samples of the urban, adult populations aged 25 and over in private households. National samples numbered about 1,200 (6,106 for the five countries), and were drawn from cities with populations over 100,000. The elderly respondents (75+) were oversampled to represent about one-third of the sample in order to allow more detailed analysis of the circumstances and views of the elderly generation. The design allows analyses of a variety of intergenerational relationships, the focus here being relationships between elderly parents and adult children. Random samples were obtained through slightly different procedures, including in some countries random-route procedures that do not allow a calculation of response rates. Although participation rates are often characteristically low in urban areas, the samples were found to be representative for the target populations, with no survey-specific selectivity problems (Motel-Klingebiel et al. 2003).

Two questions shall be explored here using Spain and Norway as the two contrasting cases: (1) Is intergenerational solidarity stronger in the presumably more collectivist south than in the more individualist north? (2) Is there indeed less family care when services are more available, or put more generally, is the more generous welfare state a risk or a resource for family elder care? The first question may be explored with reference to solidarity between adult children and elderly parents more generally. The second question needs to be tested when there is a need for care, and solidarity is put to a more serious test. Norway and Spain are in both instances assumed to be the two contrasting cases, first because they have different family cultures, and second because they have different welfare states and opportunity structures. We shall return to the ‘culture versus opportunity’ issue later.

Concepts and measurements

‘Intergenerational family solidarity’ is seen here as a multi-dimensional concept in line with a model developed by Vern Bengtson and colleagues on a US data set (Bengtson and Roberts 1991). The original model includes six solidarity dimensions—structural, associational, consensual, affectional, functional and normative solidarity. Factor analyses of the relevant items in OASIS revealed more or less the same structure in all five countries, but with a simpler variant than in the original US model. Dimensions could be reduced to four, implying that solidarity can be expressed in terms of association, affection, helping (functional), and as normative obligations (Daatland and Herlofson 2004). Frequency of contact, emotional closeness, exchange of help, and support for filial norms are taken as operational expressions of these aspects of solidarity. The factor analyses gave no support for ‘consensus’ (sharing the same values) as a distinct solidarity dimension. Nor did the analysis indicate that ‘structural’ (geographical distance) and ‘associational’ solidarity (frequency of contact) could be separated as in the original model. Hence ‘consensus’ and ‘structure’ are not included here as separate dimensions. More details about the measurements are given in the findings section.

The solidarity model has been criticized for being biased toward family harmony (Marshall et al. 1993). ‘Conflict’ was therefore added as a separate dimension in a revised ‘intergenerational solidarity and conflict model’ (Silverstein and Bengtson 1997), and was found to be a distinct factor also in the five OASIS countries. Intergenerational relationships may thus be both close and conflictual; the two are not at opposite ends of the same dimension. In fact, family relationships may, according to Lüscher and Pillemer (1998), be best described as ‘ambivalent’. We shall, however, in this article concentrate on the solidarity aspects of family relationships.

Intergenerational solidarity may be perceived and measured from both sides of the relationship, and usually comes out stronger when seen from above (from parents) than from below (from children), a finding that is given a theoretical formulation in the so-called ‘developmental stake hypothesis’ (Bengtson and Kuypers 1971). This article concentrates on the parents’ perspective, and therefore presents a somewhat greater image of solidarity image than if the children’s perspective were chosen. This should not, however, bias the comparison between the countries.

The second research question, how family care is related to welfare state services, needs to be studied in a more narrow context, and only when needs make services relevant and put family solidarity to a more serious test. Only older respondents (75+) that are in need of help are therefore included in the analysis. The criterion for being included among those ‘in need’ is a score among the lower 60% on a functional ability test (Short Form 12 Schedule, see Ware and Sherbourne 1992).

How the welfare state and the family impact on each other has often been discussed with reference to the crowding-in versus the crowding-out argument (Künemund and Rein 1999; Kohli 1999). Crowding-out is assumed to be the case if countries with high service levels have low levels of family help; the implication being that available services tend to reduce the need for family help, or even to discourage it. Crowding-in implies that countries with high service levels also have high levels of family help, implying that access to services has tended to stimulate, or at least not discourage, family help.

It may be useful to separate the crowding-out hypothesis into two variants—substitution and compensation. Substitution refers to cases where an active welfare state pushes the family out, either because family help is no longer needed (Lingsom 1997), or more radically, because an expanding welfare state tends to demoralize the family—the so-called moral risk argument (Wolfe 1989). Compensation assumes a contrasting dynamics, starting with a decline in family care, which the welfare state later has to compensate for. Both variants indicate that family care and welfare state services are alternative sources of help (either–or) and are negatively correlated, but total help levels are kept more or less in balance. Crowding-in may likewise be split into two variants, as the welfare state may complement or even stimulate the family efforts. The welfare state may complement the family by adding competences to those of the family. Services may even stimulate the family efforts by sharing the burdens. We should in both cases expect an increase of shared or mixed help (both–and), most probably with some functional differentiation between them, as in the so-called ‘task specificity model’ (Litwak 1985). Which of the four patterns finds support here?

As the intention here is to study the family–welfare state balance, only those types of help that are relevant for both are included, in this case help with household chores, transport and shopping, and personal care. Medical treatment and emotional support are not included, as the former is a case for professionals only, and the latter (predominantly) a case for informal helpers.

Both help rates and help profiles are of interest. Help rates are indicated by the proportion of elders in need that have received each type of help (with household chores, transport and shopping, and personal care) during a 12-month period. Help profiles tell us from which source the help is provided. The volume of help supplied by each source is not recorded. When we compare sources of help country-by-country, we therefore assume that each source (on average) provides the same amount of help. If the average family helper actually provides more help than the average service provider, this procedure will underestimate the role of families, and vice versa if services actually provide more help. More detailed measurements might have given more accurate help levels, but we assume that the chosen procedure has not biased the comparisons between help sources and countries. A possible limitation may be that help from within the household may be underestimated if such help is more often taken for granted than help from outside, but help of both kinds is indeed reported. Spouses are for example listed among the three most important family helpers in all five countries together with daughters (=most frequent) and sons. If within-household help is still underreported, then the role of family care will be underestimated, and mostly so where co-residence rates between parents and children are high such as in Spain. Note, however, that institutional care is not included, and would have added to the welfare state side of the balance.

Findings

Intergenerational solidarity

What then, is the level and character of solidarity between elderly parents and adult children in the five countries? Is solidarity—as measured here—stronger in the south as should be expected from a family culture perspective? The findings are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

a–c: Solidarity between elderly parents (75+) and adult children, as seen from parents (n = around 330 for each country), and d: support for filial norms in total sample aged 25+ (n = around 1,200 for each country). Percentages

| Norway | England | Germany | Spain | Israel | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a. Associational solidarity | |||||

| Live with child | 7 | 16 | 10 | 38 | 7 |

| Face contact weekly+ | 71 | 80 | 61 | 93 | 84 |

| Face or tel. contact weekly+ | 91 | 93 | 75 | 94 | 97 |

| b. Affectual solidarity | |||||

| Feel very close to child | 69 | 80 | 51 | 70 | 85 |

| Get along very well | 79 | 86 | 50 | 66 | 85 |

| c. Functional solidarity | |||||

| Received help from children | 70 | 75 | 81 | 75 | 69 |

| Given help to children | 56 | 54 | 52 | 50 | 49 |

| d. Normative solidarity (% agree) | |||||

| Filial responsibilitya (index) | 76 | 74 | 68 | 83 | 83 |

| Should be able to trust children | 58 | 41 | 55 | 60 | 51 |

| Children should sacrifice | 41 | 47 | 36 | 44 | 37 |

| Children should live close | 29 | 31 | 40 | 57 | 57 |

| Parents are entitled to returns | 38 | 48 | 26 | 55 | 64 |

a Filial responsibility scale with four items and five response categories (strongly agree, agree, neither–nor, disagree, strongly disagree): (1) adult children should live close to their older parents so that they can help them if needed, (2) parents are entitled to some return for the sacrifices they have made for their own children, (3) adult children should be willing to sacrifice some of the things they want for their own children in order to support their ageing parents, (4) older people should be able to depend on their adult children to help them do the things they need to do (adopted after Lee et al. (1998)). Index = percent in agreement with at least one item, the following lines show agreement with each of the individual items

Spain indeed has the highest level of `associational solidarity’, as indicated by the frequency of contact between parents and children (Table 2a). This is, however, partly due to the higher co-residence rates in Spain, which may be a consequence of fewer opportunities for independent living than of personal choice. Separate households between generations is a growing trend globally (Sundström 1994), and seems to be a more or less universally expanding ideal not only in the younger, but also in the older generations (Daatland 1990). This is suggested also by OASIS data, as the majority in four of the five countries is negative towards shared households. If they could no longer manage by themselves in old age, they would rather move to a nursing home than reside with a child. Spain is the only exception to this pattern, with a majority of elders in favour of co-residence. Younger Spaniards are more reluctant to share households between generations, as are both the younger and older generations in the more northern countries (Daatland and Herlofson 2003).

A comparison with earlier cross-national studies, like ‘Old people in three industrial societies’ (Shanas et al. 1968), suggests that contact frequencies are only slightly lower (5–10% points) in the comparable OASIS countries today. England was included in both studies, while Denmark of the 1960s (in ‘Old people’) may be compared to Norway around 2000 (in OASIS). Considering that the OASIS data refer to the urban populations only, and counts contacts with the most frequently seen child, not any child as was the case in the ‘Old people’ study, the findings suggest a remarkable stability in ‘associational solidarity’ across time and space. Daily contacts are, however, less frequent today than 40 years ago, primarily because cohabitation rates are lower. Modern adult children may also have compensated for larger distances and more time pressure via the telephone, or even e-mail.

`Affectual solidarity’ seems equally strong in the northern and southern countries, maybe even slightly stronger in the north, as indicated in Table 2b by the proportion of elderly that say they are feeling ‘very or extremely close’ to their children and are getting along ‘very or extremely well’ with them. Some 70–80% of elderly parents responded as above in four of the five countries. The respondents were in this case asked to consider their contacts with ‘a randomly selected child’, not with some ‘average child’.

There is no substantial difference between the countries as far as `functional solidarity’ is concerned. Its level was determined by measuring help given and received during a 12-month period. Table 2c shows the proportion of parents aged 75+ that received and provided at least one of the six types of help (emotional support, transport, gardening, housework, personal care, financial support). Three out of four elderly parents received help from their children, while slightly more than half have provided help. Elderly parents receive more than they give, as is to be expected. As for types of help (not shown in the table), we find that ‘emotional support’ flows in both directions, ‘instrumental help’ (like gardening, transport, and housework) flows mostly upwards from children to parents, while ‘financial support’ flows downwards when economy allows it, which is the case in Norway and Germany where pension levels are high compared to pension levels in the other countries. Israel stands out with substantial levels of financial support in both directions. Financial support flows in the same direction as instrumental help in Spain and (to a lesser degree) in England, i.e. from adult children to elderly parents, indicating that more elders may have economic problems in these two countries. The contrast between Germany and Norway on the one hand, and Spain and England on the other, may be taken as an indication of how a generous pension may strengthen the older generations’ position in the family by allowing them to reciprocate help received. Künemund and Rein (1999) suggest that this is an example of the family being ‘crowded-in’ by a generous welfare state (pension).

`Normative solidarity’ does, however, seem stronger in the south (Spain and Israel), which is in Table 2d indicated by the proportion of respondents (total sample) in agreement with four items on a filial responsibility scale developed by Lee et al. (1998) and adapted for the OASIS study. The first line shows agreement with at least one of the four items; the following lines illustrate the character of the norm in terms of support (agreement) for each of the four individual items on the scale. Filial solidarity as measured here is weaker, but substantial, also in the north, even in a universalist welfare state like Norway and in larger urban areas such as those that the OASIS samples are drawn from. Hence, neither urbanization nor welfare state expansion have eroded filial norms, but may have weakened or changed them.

A closer look at the findings indicates that the country differences are more clearly expressed in the character than in the strength of filial obligations. There is, for example, no difference between the countries in the support for a general responsibility norm indicated by item 1: ‘older parents should be able to depend on their adult children for help when needed’. Six out of ten agree with this norm in both Norway and Spain. In contrast, twice as many Spaniards (and Israelis) as Norwegians agree that ‘adult children should live close to their older parents’ (item 3). Spain (and Israel) also has far higher support for the reciprocity norm (‘parents are entitled to some return for earlier sacrifices’, item 4). Neither of the more prescriptive norms (items 3 and 4) attracts much support in the northern countries. The northern ‘model norm’ seems to be based on a combination of responsibility and independence between the generations. Northern ideals of intergenerational relationships seem more person-driven and less prescriptive, with considerable room for negotiations about how responsibilities should be translated into practice, as suggested also by Finch and Mason (1993, 1990). The southern family seems more duty driven, with more direct and detailed prescriptions about what the responsibilities are and how they should be carried out.

There is a stronger wish for independence amongst the elderly in the northern countries. In the Norwegian case this is demonstrated by reluctance amongst the elderly to ask their children for help with long-term care needs; nine out of ten Norwegian elders would rather turn to services. In Israel a similar reluctance exists amongst the elderly, although it is not as strong as that in Norway (for details, see Daatland and Herlofson 2003). These two countries have rather generous service levels, which indicates that the preference for services (over family care) is a reflection of ‘opportunity’ more than of ‘culture’.

The findings—all in all—give little support to the hypothesis that intergenerational solidarity is substantially stronger in southern than in northern European countries. Whether solidarity between adult children and elderly parents will continue at current levels remains to be seen. Some indication of this may emerge out of the findings of the second research question: whether the availability of social care services is a risk or a resource for family care.

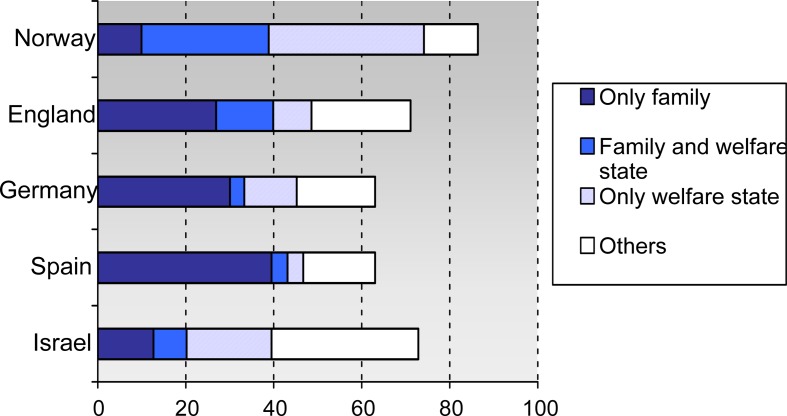

The family–welfare state balance

The analyses here are restricted to a more narrow group of elderly people (75+) that is in need of help (those among the 60% with the lowest scores on the SF12 functional ability scale) and are restricted to types of help that are relevant for both services and families, namely help with household chores, transport and shopping, and personal care. The descriptive findings on help levels and help profiles are presented in Fig. 1 and Table 3. Help profiles are in Fig. 1 classified as help from ‘family only’, from ‘welfare state only’ and ‘mixed help’ (from both family and welfare state). ‘Welfare state’ services include both public services, which is the modal case in Norway, and private non-profit (‘voluntary’) services, which are more prominent in continental welfare states, where service provision is more often contracted out to welfare organizations (publicly financed and regulated) and is therefore here seen as included under the welfare state. All other helpers or combinations of helpers are in Fig. 1 categorized as ‘other sources’, and include help (mixed in some cases) from friends, neighbours, and commercial services.

Fig. 1.

Help rates and help sources by country for those aged 75+ in needa. Percentages

Table 3.

Help rates by source and country for those aged 75+ in needa Percentages

| Help from | Norway | England | Germany | Spain | Israel |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Family | 43 | 49 | 39 | 48 | 29 |

| Welfare stateb | 64 | 22 | 15 | 7 | 27 |

| Commercial services | 11 | 15 | 14 | 15 | 28 |

| Other | 1 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 5 |

| Total (sum help from all sources)c | 119 | 93 | 72 | 72 | 89 |

| Total with helpd | 86 | 71 | 63 | 61 | 73 |

| (n) | (162) | (220) | (253) | (228) | (303) |

a Scoring among the lower 60% of the 75+ sample on the SF12 functional ability scale

b Public services and/or private non-profit (‘voluntary’) services

c Total may exceed 100% as one may have help from several sources

d Percent with help among those in need

Help rates from ‘family only’ are highest in Spain, but differences in (total) family help rates tend to be levelled out when ‘mixed help’ (from the family and the welfare state) is added. Norway, followed by Israel, has the highest rate of help from the welfare state, but access to services does not seem to have crowded-out the family. Instead, it seems to have changed the family role in the care system, possibly towards less burdensome tasks. The high rates of mixed help in Norway suggest this. Total help levels are therefore higher in countries with high service levels (Norway and Israel) than in countries with low service levels, where elder care is predominantly a responsibility of the family (Germany and Spain).

Some crowding-out may, however, also have taken place. Norway has for example a substantial minority of elders who manage with help from the welfare state only. Part of the explanation may be that some elderly people have hardly any family, as childlessness is considerable in these cohorts in northern Europe. Services may also have substituted (crowded-out) the family in some cases, and if so, the explanation may possibly be found in both generations. Services may have allowed children to withdraw, but probably more important is that access to services has reduced elderly people’s dependency on the family and allowed them more autonomy. The latter possibility reminds us that elderly people are not passive recipients of care, but are themselves active in the construction of care systems through their values and preferences; for example, they are often afraid of being a burden to their children and therefore prefer services over family care. Help rates and help patterns should therefore ideally be studied from both sides of the relationships.

Table 3 presents in more detail total help levels from each help source; it includes also commercial services as a separate category. Such market-based services contribute most in Israel, primarily with domestic help, and to a lesser degree with personal care (not shown in Table 3). Norway has the lowest level of commercial services, but only slightly lower than the level in the other countries (except Israel).

Crowding-in or crowding-out

To test the possibility that access to welfare state services may affect family help negatively (crowding-out) or positively (crowding-in) would require a multivariate analysis, where the effect of other relevant factors is controlled for. Table 4 summarizes the results of multiple regressions of the different help sources, while Table 5 tests the hypothesis more directly in a regression of family help on the access to services for each country. Only elders (75+) with children are included in these analyses.

Table 4.

Regressiona of help from different sources among those aged 75+ with children

| Family help | Mixed family and welfare state | Welfare state | Help total (any source) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function (1=limited) | .240 | .199 | .255 | .314 |

| Gender (1=women) | .022 | .019 | −.002 | .009 |

| Civil status (1=married) | −.071 | −.067 | −.098 | −.169 |

| Children close-by (1=yes) | .147 | .036 | −.080 | .030 |

| Emotional close (1=yes) | .063 | .071 | .024 | .053 |

| Preference (1=family help) | .122 | −.076 | −.060 | .054 |

| England | .009 | −.056 | −.251 | −.086 |

| Germany | .039 | −.119 | −.326 | −.067 |

| Spain | −.049 | −.139 | −.292 | −.108 |

| Israel | −.102 | −.095 | −.223 | .015 |

| R2 | .135 | .076 | .164 | .159 |

| (n) | (1,603) | (1,617) | (1,617) | (1,614) |

a OLS standardized regression coefficients, missing cases left out. Children close-by means within 10 min distance. Countries as dummies with Norway as the reference. Significant coefficients (<.05) in bold

Table 5.

Regressiona of help from the family among those aged 75+ with children (1) on help from the welfare state, with (2) control for needs and family resources

| Norway | England | Germany | Spain | Israel | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

| Welfare state help (1=yes) | .194 | .064 | .227 | .148 | −.007 | .001 | .029 | −.006 | .013 | .009 |

| Function (1=limited) | .218 | .301 | .206 | .264 | .088 | |||||

| Gender (1=women) | .066 | .024 | .002 | .010 | .031 | |||||

| Civil status (1=married) | −.054 | −.117 | −.019 | −.114 | .026 | |||||

| Children close-by (1=yes) | .113 | .111 | .178 | .120 | .234 | |||||

| Emotional close (1=yes) | .122 | .048 | .149 | −.020 | −.018 | |||||

| Preference (1=family help) | −.001 | .095 | .176 | .156 | .041 | |||||

| R2 | .038 | .117 | .052 | .197 | .000 | .147 | .001 | .158 | .000 | .074 |

| (n) | (340) | (320) | (315) | (303) | (362) | (350) | (327) | (312) | (343) | (318) |

a OLS standardized regression coefficients, missing cases left out. Children close-by means within 10 min distance. Countries as dummies with Norway as the reference. Significant coefficients (<.05) in bold

The five countries are in Table 4 included as dummies with Norway as the reference. The model also controls for the effects of needs (functional limitations) and family resources (a partner and children living nearby). Help preference (for family care or services) is included to control for the role of the help recipient him- or herself. Neither gender nor ‘class’ (indicated by education and subjective economy) was found to make any difference in access to help, but gender is still included in the model for illustrative purposes. Dependent variables to be explained are access to family help, help from the welfare state, and mixed help (from the family and the welfare state). Total access to help—from all sources—is also analysed in Table 4.

The analyses show that differences between the countries remain after control for the model factors. Total help levels (from all sources) are significantly higher in Norway and Israel than in the three countries with the lowest service levels. Norway has a significantly higher rate of welfare state services than the other four countries, and higher levels of mixed help (than three of the other countries). A high level of mixed help probably indicates some functional differentiation between the help sources. There is, however, no significant difference between countries in levels of family help, except the slightly lower level found in Israel.

Needs (functional limitations) are otherwise the most powerful factor to explain help rates from all of the help sources. Family resources also make a difference: couples manage more often without (outside) help, while a child living nearby is an asset for family help, but reduces the use of services. Being emotionally close to children does not have a significant impact on the access to help, while the attitudes among help recipients themselves make a difference in the sense that people with a preference for family care more often have help from the family (and less often from services). What comes first is not certain. The expressed preferences may be causes—or consequences—of the help patterns.

A more direct test of how access to services may impact on the access to family help is provided in Table 5 in terms of separate analyses of the access to family help for each of the five countries. The first model (column) for each country shows the bivariate correlation between help from the welfare state and the family. The two are significantly (and positively) related only in Norway and England, probably because both the family and the welfare state have responded to the needs for help. The zero correlation for the other three countries is possibly explained by the two being alternative sources of help in these countries; you either have help from one or from the other.

The second column for each country shows the multivariate analysis with control for needs and family resources as in Table 4. Needs are also in Table 5 found to be the major explanation for the receipt of help, supplemented by family resources (a child living nearby). But access to welfare state services does not reduce family help levels, as suggested in the crowding-out hypothesis. If anything, such access may increase access to help from the family, but significantly so only in England. Israeli studies have otherwise shown that the proliferation of services under the Long-term Care Insurance Law (1988) did not decrease family help, but ‘pushed’ the family towards more social and emotional supports (Katan and Lowenstein 2001).

There is little support for the crowding-out hypothesis in these findings, but neither is there much support for the ‘strong variant’ of the crowding-in hypothesis, where services are expected to stimulate (increase) family help. A weaker variant of the crowding-in scenario seems to fit the data best, namely that a generous welfare state neither reduces nor increases family efforts, but allows the family to re-orient their responsibility towards less burdensome tasks and needs that are poorly covered by services. An increase in service provision will therefore contribute to an increase in the total level of care, and to a more mixed, or shared, help profile.

Conclusion and policy implications

In conclusion, intergenerational family solidarity seems to be considerable in both the northern and southern welfare states included in the OASIS study (Table 2). Solidarity seems to vary in character more than in strength, and seems in the northern welfare states to be combined with an ideal of independence between generations, an ideal that may be more of a response to ‘opportunity’ than to ‘culture’. Easier access to welfare state services has not replaced the family, but may have contributed to changing how families relate. The findings suggest that family solidarity is not easily lost. Why should it be, considering the fundamental and often existential character of parent–child relationships?

The mixed models of family care and welfare state provision vary considerably between the countries. The Israeli model is characterized by a fairly even split between the family, the welfare state, and the market (Table 3 and Fig. 1). Family care dominates in Germany, Spain, and England, with the welfare state in second place in England, the market second in Spain, and a rather even split between the market and the welfare state (after the family) in Germany. Norway stands out with the welfare state as the major help source. It has the simplest of the five models, being dominated as it is by two major sources—public services and family care. Spain also has a simple model, but one based on family dominance. The other three countries have more pluralistic models, including a mix of public and private (non-profit) care provision within the welfare state. Some convergence may now be emerging in Europe. Outsourcing and privatization of public services are expanding in Scandinavia, while governmental responsibility is growing in countries like Spain and Germany. In Spain this is happening more directly via increased public service provision, while in Germany it is taking a more indirect route via the introduction of an obligatory long-term care insurance program (Evers 1998; von Kondratowitz et al. 2002).

Family help levels are still rather similar across the five countries, but the actual role of the family seems to differ from country to country; the family is dominant when services are not available (Spain), whereas it is a more or less equal partner (with the welfare state) in a mixed care system such as Norway. In conclusion, more generous welfare state services have not crowded-out the family, but may have reduced dependence on the family, like pensions earlier reduced the dependence on the labour market. Services have thus helped the elderly to establish more independent relationships.

The rather simplistic measurements of help levels, based only on rates (have help or not), and not volumes (how much help), are one limitation of the present study. Future analyses should also include the children’s perspective, rather than only the perspective of the elderly, as in this article. It might also have been useful to include smaller urban areas and rural areas, rather than only large cities as in the OASIS case, in order to test if intergenerational solidarity and the family–welfare state interaction take different forms along the rural–urban dimension within each country. Note also that the explained variance of the mulitivariate analyses (Tables 4 and 5) was rather low, indicating that important factors are not included in the present models. And finally, a true test of crowding-in or crowding-out needs a longitudinal design, not only cross-sectional data as used here.

These limitations invite further studies, and further sophistication of concepts, measurements, and analyses. Of interest is, for example, how we can separate the effects of ‘culture’ from ‘opportunity’ (living conditions and available options). A lesson from the present study is to be careful with the use of ‘culture’ as an explanatory variable; one should at least control for opportunity and other hard-core characteristics that are related to ‘culture’. And secondly, we need to clarify the definition of ‘solidarity’. It is hard to see solidarity in behaviour that is caused by external pressure (necessity or duty). A more narrow definition of ‘solidarity’ may be productive for the analysis of the family–welfare state balance, and we suggest reserving the solidarity term for the willingness to act to the benefit of (significant) other(s). Comparisons of solidarity over time and space are therefore difficult, because the contextual circumstances (opportunities) differ, which makes it hard to separate choices from constraints, and true solidarity from apparent ‘solidarity behaviour’ that in reality is enforced. We need data on both intentions, behaviours, and opportunity structures in order to separate the two variants.

And finally, in terms of policy implications, the reported findings make it hard to see so-called familialist policies as sustainable for a future of population ageing. For one thing, a familialist model is not congruent with the preferences of the present generations, be they young or old, and will probably not be a model preferred by future generations either. Young and old should be encouraged and supported in their mutual concern for each other. That concern should, however, not result from imposed norms or outright necessity, because these are risks to, rather than resources for, family cohesion.

Footnotes

Contributor Information

Svein Olav Daatland, Email: svein.o.daatland@nova.no.

Ariela Lowenstein, Email: ariela@research.haifa.ac.il.

References

- Bengtson VL, Roberts REL. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: an example of formal theory construction. J Marriage Fam. 1991;53:856–870. doi: 10.2307/352993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daatland SO. What are families for? On family solidarity and preferences for help. Ageing Soc. 1990;10:1–15. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00007820. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daatland SO. Family solidarity, popular opinion, and the elderly: perspectives from Norway. Ageing Int. 1997;1:51–62. doi: 10.1007/s12126-997-1023-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daatland SO, Herlofson K (2001) Ageing, intergenerational relations, care systems and quality of life. An introduction to the OASIS project. Oslo: NOVA, report 14–2001

- Daatland SO, Herlofson K. ‘Lost solidarity’ or ‘changed solidarity’: a comparative European view of normative family solidarity. Ageing Soc. 2003;23:537–560. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X03001272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daatland SO, Herlofson K (2004) Familie, velferdsstat og aldring. Familiesolidaritet i et europeisk perspektiv. Oslo: NOVA rapport 7–2004

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. Social foundations of postindustrial economies. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Evers A. The new long-term care insurance program in Germany. J Aging Soc Policy. 1988;10(1):77–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrera M. The ‘southern model’ of welfare in social Europe. J Eur Soc Policy. 1996;6(1):17–37. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600102. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finch J, Mason J. Negotiating family responsibilities. London: Tavistock/Routledge; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Katan J, Lowenstein A. Basing welfare services in a legal infra structure—implications of the Long-term Care Insurance Law. Gerontology. 2001;27(1):55–68. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M (1999) Private and public transfers between generations: linking the family and the state. European Societies 1

- Künemund H, Rein M. There is more to receiving than needing: theoretical arguments and empirical explorations of crowding in and crowding out. Ageing Soc. 1999;19:93–121. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X99007205. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GR, Peek CW, Coward RT. Race differences in filial responsibility expectations among older parents. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:404–412. doi: 10.2307/353857. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lingsom S (1997) The substitution issue. Care policies and their consequences for family care. Oslo: NOVA, report 6–1997

- Litwak E. Helping the elderly: the complementary roles of informal networks and formal systems. New York: Guilford Press; 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A, Ogg J, editors. OASIS. Old age and autonomy: the role of service systems and intergenerational family solidarity. Final report. Haifa: University of Haifa; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A, Katz R. Living arrangements, family solidarity and life satisfaction of two generations of immigrants. Ageing Soc. 2005;25:1–19. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X04002892. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: a new approach to the study of parent–child relations in later life. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:413–425. doi: 10.2307/353858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VW, Matthews SH, Rosenthal CJ. Elusiveness of family life: a challenge for the sociology of aging. In: Maddox GL, Lawton MP, editors. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: focus on kinship, aging and social change. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Millar J, Warman A. Family obligations in Europe. London: Family Policy Studies Centre; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Motel-Klingebiel A, Tesch-Römer C, von Kondratowitz H-J. The quantitative survey. In: Lowenstein A, Ogg J, editors. OASIS old age and autonomy: the role of service systems and intergenerational family solidarity. Final report. Haifa: University of Haifa; 2003. pp. 63–101. [Google Scholar]

- Reher DS. Family ties in western Europe: persistent contrasts. Popul Dev Rev. 1998;24(2):203–234. doi: 10.2307/2807972. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Bengtson VL. Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult–child relationships in American families. Am J Soc. 1997;103(2):429–460. doi: 10.1086/231213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sundström G (1994) Care by families: an overview of trends. In: Hennesy P (ed) Caring for frail elderly people in Europe. New directions in care. Paris: OECD, Social Policy Studies no 14, pp 15–55

- UN (2002) World population ageing 1950–2050

- von Kondratowitz HJ, Tesch-Römer C, Motel-Klingebiel A. Establishing systems of care in Germany: a lpng and winding road. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(4):239–246. doi: 10.1007/BF03324445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Kondratowitz HJ. Comparing welfare states. In: Lowenstein A, Ogg J, editors. OASIS old age and autonomy: the role of service systems and intergenerational family solidarity. Final report. Haifa: University of Haifa; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short-form health survey (SF-36) Med Care. 1992;30(6):473–483. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe A. Whose keeper? Social science and moral obligations. Berkely: University of California Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]