Abstract

As most countries face the ageing of their population, understanding successful and pathologic ageing is a research priority. Longitudinal studies examining the ageing process from middle-age are required to establish causal and valid relationships. This systematic review of the literature aimed at identifying large community-based longitudinal studies either including exclusively elderly people or following people from middle-age (50+ years at enrolment) to death, and resulted in a selection of 72 cohort studies. Design features of selected studies show that most were conducted in North America or Northern Europe, most included both genders, and follow-up period was often less than 10 years. Many cohorts focused on cardiovascular health, cognitive decline or osteoporosis. Usually collected variables comprise of self-reported data on socio-demographics, chronic diseases and functional status, as well as measures of cognition, anthropometrics and physical performances. Biological samples were taken in about 60% of the studies, and a third also undertook genetic analyses. This review summarises information on design and content of large population-based cohorts of older persons, and represents a valuable background from which additional data may be retrieved.

Keywords: Cohort study, Longitudinal study, Aged, Ageing, Review

Introduction

Parallel to the ageing of populations, the number of dependent older persons has increased considerably, as well as the need for costly long-term care services. In this context, geriatric research has been interested in the determinants of health in later life, and, more recently, the concept of frailty has emerged as a key issue (Rockwood et al. 1994). There is still much debate around the nature and measurement of frailty (Hogan et al. 2003), and further results from population-based longitudinal studies are needed to investigate the determinants of successful ageing and frailty (Fried et al. 2001; Peel et al. 2005). Numerous cohort projects have already been undertaken, or are still ongoing, focusing on the different populations and different health domains. An insight into the existing studies might be useful for the researcher before undertaking a new project and for the clinician interested in a particular health domain. Overviews of the design and content of the previous projects are not so easily available, even though most large cohort studies did publish articles on methodology or have a website providing this type of information. Summary information allowing to compare similar cohort projects is particularly difficult to find. This review aimed at identifying large population-based cohort studies including either middle-aged adults (aged 50 and over) or focusing on older persons. A literature search did not retrieve any comparable work: previous reviews focused on the disease-related morbidity (Pryer et al. 1995; Bosworth and Siegler 2002), or on a specific theme such as functional decline (Stuck et al. 2002). A similar, yet less systematic work, was undertaken in Canada. Its selection of cohorts was slightly different and results may be considered as complementary (Health Canada, Review of longitudinal studies on ageing, available on the Internet).

Our review provides a summary of design characteristics and domains of investigation of selected studies examining age-related health events in older adults and represents a useful source of references for research on health in ageing.

Methods

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria for selecting cohort studies were a lower age limit at enrolment set at 50 years or more and a minimal sample size of 500 subjects at baseline.

By setting this arbitrary lower sample size limit, we intended to select cohort studies large enough to provide sufficient statistical power given attrition over time. Then, to select cohorts representative of the general population, the search was limited to the population-based studies.

Search strategy

We first identified keywords or MesH terms used in several publications related to cohort studies of elderly people. The search strategy combined the terms “ageing” or “aged” with terms related to the study design: “cohort study or studies” or “longitudinal study or studies” and “population-based”. The research was then limited to middle-aged (45–65 years) or aged subjects (65 years or older) and to publications in English, French or German. Medline (Ovid 1966–2002), PsycInfo (1967–2002) and SocioFile (1974–2002) were searched on 31.10.2002, and 1,500, 24 and 1 publications, respectively, were retrieved. The same search strategy was rerun periodically from November 2002 to July 2004 with an extension to the publications of the years 2003 and 2004.

Other data sources

The Cochrane database was searched from October 2002 to January 2003, as well as in November 2003, and in July 2004 and did not yield any further references.

During October to November 2002, a search was conducted on the Web, using the words “cohort” or “longitudinal study”, combined with “elderly” and “health” and identified known or additional cohorts by their Internet site. Internet sites of geriatrics societies were consulted, as well as those of centres and institutes of ageing. Finally, bibliographies of relevant articles or handbooks were hand-searched.

Exclusion criteria

Retrospective or historical cohorts were not considered for inclusion. Studies not focusing on health (e.g. psychological studies) and those focusing on a narrow clinical theme were excluded, as well as studies in which data were collected from administrative or medical databases only, without contacting the participants either face-to-face or by questionnaire. Finally, studies among twins, among very specific ethnics, among people who had been exposed to nuclear irradiation, and studies selecting subjects with a specific disease at inclusion were not selected.

Study selection and data extraction

First, titles and abstracts of all 1,525 publications were screened by the first author, using the exclusion criteria. Abstracts of the 732 remaining publications were reviewed independently by the two authors. In case of disagreement, more information was searched on the study, and inclusion of the study was discussed.

To gather maximum information on each cohort, abstracts of publications related to the same cohort study were then searched in Medline using the entire name or acronym of the cohort as keyword. Whenever this strategy did not identify any publication, or only a few, we retrieved the publications of the principal investigators and identified articles related to the cohort study by reading the abstracts.

The following data were extracted from abstracts and articles: name/acronym of the study, number of subjects, age at inclusion, gender of participants, year of beginning and duration of follow-up, setting (country/town), domains assessed, number of publications in Medline and availability on the Internet. For each cohort, abstracted data were sent to one of the original investigators for review. We also requested information on the data we could not find in the publications. Finally, the investigators were asked for references of publications describing the study methodology and its main findings.

As our aim was not to evaluate the validity of the outcomes but to examine populations and themes under study, we did not assess the methodological quality of the selected studies.

Results

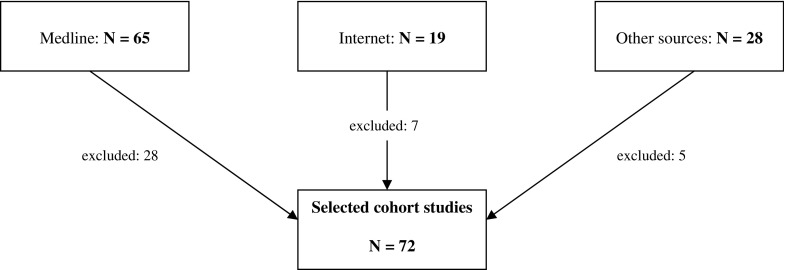

Review of the 732 abstracts by two authors resulted in the selection of 67 cohorts. Then, reading the articles led to an exclusion of 28 studies because age or number of subjects at baseline did not match our inclusion criteria. Nineteen cohorts were retrieved from the Internet search, among which 7 were excluded and 28 were retrieved from other sources, among which 7 were excluded, leaving a sample of 72 cohort studies corresponding to our criteria (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow-chart: source of identification and selection of cohort studies

Table 1 shows the selected studies by world region in alphabetical order and summaries their design: gender, age and number of subjects at inclusion, country, year of baseline assessment, duration of follow-up and major themes under study are displayed. It also indicates how many publications were retrieved using the name or acronym of the cohort as keyword in Medline 1966–2003 and whether the data abstracted from publications were validated by the investigators of the study (about 30% of original investigators did not respond to that request, and data for those studies are displayed as found in publications).

Table 1.

Design characteristics of community-based longitudinal studies on elderly people (listed to alphabetical order and by world region)

| Study name and acronym (Reference) | Sample size | Gender | Age | Country | Beginning | Follow-up (years) | Domains assessed | Population | Website | Publicationsa | Validationb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | |||||||||||

| Berlin Ageing Study (BASE) (Borchelt and Horgas 1994) | 516 | W/M | 70+ | Germany | 1990–1993 | Ongoing | Cognitive+functional decline, depression, social network | Community | Yes | 34 | No |

| British Women’s Heart and Health Study (Lawlor et al. 2003) | 4,286 | W | 60–79 | United Kingdom | 1999–2001 | Ongoing | Cardiovascular health | Community | Yes | 6 | Yes |

| Cambridge project for later life, follow-up of Hughes Hall project (CC75C) (Brayne et al. 1992) | 2,609 | W/M | 75+ | United Kingdom | 1985 | 13 | Cognitive decline | Community+institutions | Yes | >40 | Yes |

| Cardiovascular study in the Elderly (CASTEL) (Casiglia et al. 1991) | 2,254 | W/M | 65+ | Italy | 1984 | 7 | Cardiovascular health | Community | No | 8 | No |

| Doorlopend Onderzoek Morbiditeit en Mortaliteit (DOM) (de Waard et al. 1984) | 14,697 | W | 50–65 | Netherlands | 1975 | 2 (ongoing: random subset) | Cancer reproductive health | Community | No | >15 | Yes |

| Edinburgh Artery Study (Donnan et al. 1993) | 1,600 | W/M | 55–74 | United Kingdom | 1987 | 5 | Cardiovascular health | Community | Yes | 45 | No |

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) (Nazroo 2001) | 12,000 | W/M | 50+ | United Kingdom | 2001 | Ongoing | Medical, social and economic data | Community | Yes | 1 | Yes |

| EPIDOS (Dargent-Molina et al. 1996) | 7,575 | W | 75+ | France | 1992 | 4 | Osteoporosis | Community | No | 22 | Yes |

| Etude du Vieillissement Artériel (EVA) (Dufouil et al. 1997) | 1,389 | W/M | 59–71 | France | 1991–1992 | 4 | Cognitive decline | Community | No | >40 | Yes |

| EURONUT-SENECA: Survey Europe on Nutrition in Elderly: Concerted Action (Van’thof et al. 1991) | 2,586 | W/M | 70–75 | 12 Countries | 1988 | 10 | Nutrition, health status, social data | Community | Yes | >40 | Yes |

| European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (EVOS), followed by European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS) (O’Neill et al. 1995) | 13,400 | W/M | 50+ | 19 Countries | 1990 | 3–4 | Osteoporosis | Community | Yes: EPOS | EVOS: 31, EPOS: 9 | Yes |

| FINE study (Menotti et al. 2001) | 2,226 | M | 65–84 | 3 Countries | 1984–1985 | 15 | Cognitive+functional decline, cardiovascular health | Community | No | 8 | Yes |

| Gospel Oak Project (Livingston et al. 1990) | 889 | W/M | 65+ | United Kingdom | 1994 | 1 | Depression, dementia | Community | No | 7 | No |

| Gothenburg H-70 Study (Maxson et al. 1996) | 508 | W/M | 70 | Sweden | 1971 | 20 | Medical and social data | Community | No | 8 | No |

| Groningen Longitudinal Ageing Study (Ormel et al. 1998) | 5,279 | W/M | 56+ | Netherlands | 1993 | Ongoing | Cognitive decline, psychological status | Community | No | 5 | Yes |

| Helsinki Ageing Study (Tilvis et al. 1996) | 795 | W/M | 75+ | Finland | 1990 | 5 | Cognitive decline, dental problems | Community | No | >50 | Yes |

| Hoorn Study (Mooy et al. 1995) | 2,484 | W/M | 50–75 | Netherlands | 1989 | Ongoing | Diabetes and glucose intolerance | Community | Yes | 42 | Yes |

| Italian Longitudinal Study on Ageing (ILSA) (Maggi et al. 1994) | 5,493 | W/M | 65–84 | Italy | 1992 | Ongoing | Cognitive decline, depression | Community+institutions | No | 17 | Yes |

| Kungsholmen Project (Fratiglioni et al. 1991) | 1,810 | W/M | 75+ | Sweden | 1987 | 12 | Cognitive decline | Community | Yes | 27 | Yes |

| Lausanne Cohort 65+ (LC65+) (information available from : http://www.iumsp.ch) | 1,567 | W/M | 65–69 | Switzerland | 2004 | Ongoing | Frailty | Community | No | 0 | Yes |

| Leiden 85-plus study I/II (Westendorp 2002) | I: 977, II: 599 | W/M | 85+ | Netherlands | 1987/1997 | 15/5 | Cognitive+functional decline, depression | Community | No | >10 | Yes |

| LEILA 75+ (Busse et al. 2002) | 1,500 | W/M | 75+ | Germany | 1997 | 1.5 | Cognitive decline, vision | Community+institutions | No | 3 | No |

| Longitudinal Ageing Study Amsterdam (LASA) (Deeg et al. 2002) | 3,107 | W/M | 55–85 | Netherlands | 1992 | 10 | Cognitive+affective status, functional status | Community+institutions | Yes | >35 | Yes |

| Longitudinal Survey of Ageing (information available from: http://www.agenet.ac.uk) | 1,500 | W/M | 65+ | United Kingdom | 1987 | 3 | Health status, health services use | Community | Yes | 0 | No |

| Medical Research Council-Cognitive Function in Ageing Study (MRC-CFAS), including Resource Implication Study (Saunders et al. 1993) | >10,000 | W/M | 65–75 | United Kingdom | 1991 | 5 | Cognitive decline, cardiovascular health, depression, health services use and costs | Community | No | 12 | No |

| Melton Osteoporotic Fracture (McGrother et al. 2002) | 1,289 | W | 70+ | United Kingdom | 1989 | 5–6 | Osteoporosis | Community | No | 2 | Yes |

| Million Women Study (Million Women Study Collaborative Group 1999) | 1,400,000 | W | 50–64 | United Kingdom | 1996–2001 | Ongoing | Hormone replacement therapy, breast cancer | Community | No | 3 | Yes |

| Netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer (Dorant et al. 1994) | 120,852 | W/M | 55–69 | Netherlands | 1986 | 7–8 | Nutrition, cancer | Community | No | 16 | No |

| Nordic Research on Ageing (NORA) (Kauppinen et al. 2002) | 3×400 | W/M | 75+ | 3 Countries | 1990 | 5 | Normal Ageing, functional decline | Community | Yes | 9 via web | No |

| North London Eye Study (Reidy et al. 2002) | 1,318 | W/M | 65+ | United Kingdom | 1997 | 4 | Ophthalmology | Community | No | 1 | No |

| Nottingham Longitudinal Study of Activity and Ageing (Morgan 1998) | 1,042 | W/M | 65+ | United Kingdom | 1985 | 12 | Physical activity, functional decline | Community | No | 3 | No |

| Odense Study (Nielsen et al. 1999) | 2,500 | W/M | 65–85 | Denmark | 1997? | 2 | Cognitive decline, depression | Community | No | 6 | No |

| Personnes âgées QUID? PAQUID (Dartigues et al. 1991) | 3,777 | W/M | 65+ | France | 1988 | Ongoing | Cognitive+functional decline | Community | Yes | 71+report on website | Yes |

| Rotterdam Study (Meijer et al. 2000) | 7,983 | W/M | 55 | Netherlands | 1990–1993 | Ongoing | Cardiovascular health, cognitive+functional decline, depression, ophthalmology | Community+institutions | Forth-coming | >210 | Yes |

| Study of men born in 1913/study of men born in 1914 (Janzon et al. 1986) | 792/703 | M | 55 | Sweden | 1963/1968 | 32/ongoing | Cardiovascular health | Community | No | 72/>80 | Yes |

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (2004)(information available from: http://www.share-project.org) | 1,500 per country (target) | W/M | 50+ | 11 Countries | 2004 | Not yet | Health, functional status, retirement, economics | Community | Yes | 0 | Yes |

| Swiss Evaluation of the methods of Measurement of Osteoporotic Fracture risk (SEMOF) (Krieg et al. 2002) | 7,496 | W | 70–80 | Switzerland | 1998 | 3 | Osteoporosis | Community | No | 1 | Yes |

| Tampere Longitudinal Study of Ageing (TamELSA) (Jylha 1994) | 1,059 | W/M | 60–89 | Finland | 1979 | 20 | Medical and functional data, incontinence | Community | No | 3 | Yes |

| Zutphen Elderly Study (Hertog et al. 1993) | 939 | M | 65–84 | Netherlands | 1985 | 8 | Cognitive+functional decline, nutrition | Community | No | 34 | Yes |

| United States (USA) and Canada (CA) | |||||||||||

| Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), with HRS from 1998 (Soldo et al. 1997) | 8,124 | W/M | 70+ | USA | 1993 | 5 | Health status, functional decline | Community | No | 35 | Yes (referred to website) |

| Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) (The ARIC investigators 1989) | 15,784 | W/M | 51–72 | USA | 1987–1989 | 10 | Cardiovascular health | Community | Yes | 77 | Yes |

| Buck Centre for Research in Ageing (BCRA), Health and Function cohort (Reed et al. 1995) | 2,025 | W/M | 55+ | USA | 1989–1991 | 4 | Health status, functional decline | Community | No | 2 | Yes |

| Canadian Study of Health and Ageing (CSHA), Etude Santé et Vieillissement au Canada (McDowell et al. 2001) | 10,263 | W/M | 65+ | CA | 1991–1993 | 10 | Cognitive decline | Community+institutions | Yes | 117 | Yes |

| Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) (Fitzpatrick et al. 2004) | 5,201 | W/M | 65+ | USA | 1989 | 7 | Cardiovascular health | Community | Yes | 216 | Yes |

| Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE) (Blazer et al. 1991) | 4,162 | W/M | 65+ | USA | 1986–1988 | 10 | Health status, functional decline, health services use | Community | Yes | 119 | Yes |

| Etude Longitudinale Québécoise sur le Vieillissement (Québec Longitudinal Study on Ageing) (Lefrancois et al. 2000) | 782 | W/M | 60–85 | CA | 1997 | 5 | Functional decline, quality of life, retirement | Community | Yes | 2 | Yes |

| Health Ageing and Body Composition (ABC) Study (Mehta et al. 2003) | 3,075 | W/M | 70–79 | USA | 1997–1998 | Ongoing | Body composition | Community | Yes | 15 | Yes |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and Ageing, Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS), combined with AHEAD (Choi and Schlichting-Ray 2001) | 12,654 | W/M | 50–60 | USA | 1992 | Ongoing | Medical, social and economic data | Community | Yes | 59 | Yes |

| Iowa Women’s Health Study (Folsom et al. 2000) | 41,836 | W | 55–69 | USA | 1986 | Ongoing | Cancers | Community | No | 165 | Yes |

| Longitudinal Study of Ageing (LSOA) I/II (Dunlop et al. 2002) | 7,527/9,447 | W/M | 70+ | USA | 1984/1994 | 6 | Functional decline, health care use | Community | No | 18/429 | Yes |

| MacArthur Studies of Successful Ageing (sub-cohort of EPESE) (Berkman et al. 1993) | 1,189 | W/M | 70–79 | USA | 1988 | 8 | Health status, functional+cognitive decline | Community | No | 36 | Yes |

| Manitoba Study of Health and Ageing (Hawranik 1998) | 1,751 | W/M | 65 | CA | 1991 | 5 | Cognitive decline, health services use | Community | Yes | 3 | Yes |

| Massachusetts Health Care Panel Study (MHCPS) (Jette et al. 1990) | 1,625 | W/M | 65+ | USA | 1974 | 11 | Health services use, functional decline, nutrition | Community | No | 15 | No |

| Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Study (MoVIES) (Ganguli et al. 1993) | 1,681 | W/M | 65+ | USA | 1987 | 15 | Cognitive decline | Community | Yes | 45 | Yes |

| Nun Study (Greiner et al. 1996) | 978 | W | ≥75 | USA | 1991 | 15 | Dementia | Convents | Yes | >40 | Yes |

| Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) (West et al. 1997) | 2,886 | W/M | 65–84 | USA | 1993 | 2 | Ophthalmology, health status | Community | No | 21 | No |

| San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Ageing (SALSA) (Espino et al. 2001) | 833 | W/M | 65–79 | USA | 1992–96 | 3–4 | Health status, functional+cognitive decline | Mexican Americans | No | 8 | No |

| Saunders County Bone Quality Study (Davies et al. 1996) | 1,401 | W/M | 50+ | USA | 1990 | 4 | Osteoporosis | Community | No | 4 | No |

| Study of Osteoporotic Fractures (Black et al. 2001) | 9,704 | W | 65+ | USA | 9 | Osteoporosis, breast cancer | Community | No | 153 | Yes | |

| Victoria Longitudinal Study (Small et al. 1999) | 3×500 | W/M | 75+ | CA | 1990 | 6 | Psychological status | Community | Yes | 6 | No |

| Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Ageing Project (WHICAP) (Tang et al. 1996) | 1,238 | W/M | 65+ | USA | 1991 | 7 | Cognitive decline, neurological status | Community | No | >20 | No |

| Women’s Health and Ageing Study (Simonsick et al. 2001) | 1,002 | W | >65 | USA | 1992–1995 | 3 | Health status, functional+cognitive decline, health services use | Community and institutions (women with functional impairment) | Yes | 49+monography on website | Yes |

| Asia and South America | |||||||||||

| Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing (Anstey et al. 2003) | 2,087 | W/M | 70+ | Australia | 1992 | Ongoing | Cognitive decline, vision, hearing | Community | Yes | 12 | Yes |

| Bambui Health and Ageing Study (Costa et al. 2000) | 1,495 | W/M | 60+ | Brazil | 1996 | 6 | Health status, functional+cognitive decline, health services use | Community | No | 4 | No |

| Canberra Longitudinal Study (Korten et al. 1999) | 897 | W/M | 70+ | Australia | 1991 | 10 | Cognitive decline, psychology | Community | No | 21 | No |

| Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (Jones et al. 1994) | 1,762 | W/M | 60–100 | Australia | 1989 | 7 | Osteoporosis | Community | No | 15 | No |

| Epidemiologia do Idoso (EPIDOSO) (Ramos et al. 1998) | 1,667 | W/M | 65+ | Brazil | 1991 | 22 | Health status, functional+cognitive decline, health services use | Community | No | 4 | No |

| Hong Kong old–old Survey (Ho et al. 1997) | 2,032 | W/M | 70+ | Hong Kong | 1991 | 3 | Cardiovascular health, functional+cognitive decline | Community | No | >25 | Yes |

| Japanese Longitudinal Studies (Japanese Longitudinal Studies 2004) | 4,464 | W/M | 65+ | Japan | 1999 | 4 | Frailty, functional decline | Community | No | 0 (abstracts only) | No |

| Maracaibo Ageing Study (Maestre et al. 2002) | 3,657 | W/M | 55+ | Venezuela | 1998 | Ongoing | Cognitive decline, nutrition | Community | No | 3 | Yes |

| Shanghai Survey of Dementia (Hill et al. 1993) | 3,558 | W/M | 65+ | China | 1957 | 10 | Cognitive decline | Community | No | 15 | Yes |

| Tokyo Metropolitan Institute Of Gerontol–Longitudinal Interdisciplinary Study on Ageing (TMIG–LISA) (Suzuki et al. 1999) | 1,562 | W/M | 65+ | Japan | 1992 | 9 | Health status, functional decline | Community | No | >20 | Yes |

W women, M men

aNumber of publications retrieved on Medline 1966–2003 using the name or acronym of the cohort as keywords

bIndicates whether the data were validated by a principal investigator of the cohort

Finally, one reference per cohort study was chosen upon the indication of the investigators. Three studies had no indexed publications retrieved in our review process, so that their website is cited as a source of information.

Longitudinal studies of older people have been undertaken in all continents, including South America and Asia. In Europe, half of the selected cohorts originated from the United Kingdom, the Netherlands, Sweden and Germany. Most cohorts were strictly community-based, only seven projects also included participants living in institutions and one was conducted in convents.

Many studies include men and women, except for certain themes, such as osteoporosis, breast cancer and prostate cancer. Longitudinal studies focusing on cardiovascular diseases initially enrolled mainly men, and similar studies were later undertaken in women.

Age at inclusion varies with the disease under study; studies on cardiovascular events tend to recruit people in their 50s, while most studies on dementia recruit people aged 70 years or older. Studies including only younger elderly people were quite rare, as those recruiting persons older than 80 years at baseline.

If we look at cohorts focusing on specific health problems, we observe that cardiovascular disease and dementia have been the objects of many studies. On the other hand, there are only five longitudinal studies focusing on cancer. Our domain of interest, age-related fragilisation, has been examined in 28 studies, among which 23 were interested in the functional decline, while 5 focused on successful ageing.

Duration of follow-up is highly variable, from 2 years to more than 30 years. However, the majority of selected studies followed their participants for less than 10 years.

Table 2 shows a summary of variables collected in each study: although a high proportion of data are self-reported, most studies also collected data derived from observation (measure of physical or mental performances, clinical assessment), at least in a sub-sample of participants. Besides socio-demographic data, current health status, chronic conditions and medical history, a majority of studies did assess mental health using standardised tests such as Folstein’s mini-mental evaluation, Geriatric Depression Scale or Centre for Epidemiological Studies–Depression Scale. Evaluation of cognitive impairment was more frequent if the study included people aged 60 years or more at baseline. Other risk factors for functional decline such as visual and auditive impairments, incontinence, and falls were not routinely collected. These characteristics were more frequently assessed in studies of successful ageing, while neglected in studies focusing on a specific disease. A few studies described health care services utilisation.

Table 2.

Data collected in community-based cohorts enrolling older people (listed to alphabetical order and by world region)

| Study name | Socio-demographics | Chronic conditions | Functional status (reported) | Mental health | Vision, hearing | Biochemicals | Genetics | Miscellaneous |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Europe | ||||||||

| Berlin Ageing Study (BASE) | + | + | + | + | + | Physical examination, Dental status | ||

| British Women’s Heart and Health Study | + | + | + | + | + | Blood count, lipids, insulin, biochemistry, clotting | Exploratory scanning for cardiovascular disease-related genes | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, ECG, Physical activity, Dietary assessment, current and early life socio-economic environment |

| Cambridge project for later life, follow-up of Hughes Hall project (CC75C) | + | + | + | MMSE, CAMDEX, CAMCOG | No detailed data | Apoe, preselinilin, α1-antichemotrypsin, acetylcholinesterase | Lifestyle (alcohol, smoking), social network, Brain donation program | |

| Cardiovascular study in the Elderly (CASTEL) | + | + | Lipids, liver enzymes, thyroid hormones, uric acid, proteinuria | Blood pressure, Lung function, ECG, echocardiography | ||||

| Doorlopend Onderzoek Morbiditeit en Mortaliteit (DOM) | + | + | Sampling of urine and toenail clipping | BMI, Blood pressure, W/H ratio, Physical examination, Reproductive history, Mammography | ||||

| Edinburgh Artery Study | + | + | +(Bedford-Foulds personality deviance scale) | Viscosity, clotting, lipids, Lp(a), uric acid, sex hormones, glucose intolerance | MTHFR (homocystein), fibrinogen, polymorphism | Ankle-brachial pressure index, reactive hyperaemia test | ||

| English Longitudinal Study of Ageing (ELSA) | + | + | + | + | + | Yes | Yes | Data on financial and social status, use of health services, Physical performance |

| EPIDOS | + | + | + | Cognitive assessment | + | Sex hormones, alkaline phosphatase, vitamin D, osteocalcine, deoxypyridinoline, urin/serum C-telopeptide | BMI, BMD (DXA+US), Physical performance: balance, hand grip, gait | |

| Etude du Vieillissement Artériel (EVA) | + | + | MMSE, Digit Symbol, substitution, Trail making test | Biochemicals including vitamins, selenium | Apoe | Cerebral MRI and US carotid arteries at wave 3 | ||

| EURONUT-SENECA: Survey Europe on Nutrition in Elderly: Concerted Action | + | + | + | MMSE, GDS | + | Haematology, lipids, glucose, insulin, albumin, vitamins | BMI, body composition (W/H ratio, skinfold thickness), Physical performance, Dietary assessment | |

| European Vertebral Osteoporosis Study (EVOS), followed by European Prospective Osteoporosis Study (EPOS) (EVOS) | + | + | + | Creatinine, calcium, phosphate, liver enzymes, markers of bone metabolism | Growth factor polymorphism (TGF-B1) | BMI, Physical activity and dietary assessment, Gynaecologic history, medication use, BMD (DXA and US) | ||

| FINE study | + | + | + | MMSE, Dementia Rating Scale, Clock, Drawing | Lipids | BMI, Blood pressure, ECG, Hand grip | ||

| Gospel Oak Project | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Gothenburg H-70 Study | + | + | + | +neuropsychological assessment in sub-sample | +complete ophthalmological examination | + | − | Physical examination, BMI, Blood pressure, Social contacts, Physical activity, smoking, Medication use |

| Groningen Longitudinal Ageing Study | + | + | Groningen activity restriction scale | MMSE Anxiety Depression Neuroticism | + | |||

| Helsinki Ageing Study | + | + | + | MMSE, CDR | No detailed data | Blood pressure, Dental status | ||

| Hoorn Study | + | + | Ophthalmological examination, fundoscopy | Lipids, glucose, leptin, CRP, homocystein, Von Willebrand f, micro-albunmin, adhesion molecule | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, Physical examination, Glucose tolerance test Ankle-brachial pressure index, US carotid arteries | |||

| Italian Longitudinal Study on Ageing (ILSA) | + | + | MMSE, Digit cancellation, Babcock, Hamilton scale for depression | Lp(a) | ECG Clinical examination | |||

| Kungsholmen Project | + | + | + | MMSE, neuropsychological tests, life satisfaction | Blood count, albumin, iron, vitamin B12+folic acid, thyroid hormones | Apoe | Blood pressure, BMI, Clinical examination, including psychiatric and neurological tests, Medication use, dietary assessment, lifestyle habits, dental status | |

| Lausanne Cohort 65+ (LC65+) | + | + | + | + | + | Physical examination and performance | ||

| Leiden 85-plus study I/II | + | + | ADL+Groningen Activity Restriction Scale | MMSE, neuropsychological tests, GDS | Lipids, Lp(a), hba1c, IL-10, CRP | TNF-a, mutation of hemochromatosis gene | Physical performance: walk test | |

| LEILA 75+ | + | + | + | MMSE+SIDAM (with blind version testing), Neuropsychological assessment) | + | Haematocrit | ||

| Longitudinal Ageing Study Amsterdam (LASA) | + | + | + | MMSE, Auditory verbal learning test, alphabet coding task, self-report+diagnostic interview for depression, mastery, self-efficacy, self-esteem | + | Bone markers: osteocalcin, deoxypyridinoline | Apoe | BMD, Physical performance: mobility, walk, stand up, hand grip, Fall calendar |

| Longitudinal Survey of Ageing | + | + | + | + | Available information is minimal | |||

| Medical Research Council-Cognitive Function in Ageing Study (MRC-CFAS), including Resource Implication Study | + | + | + | Geriatric Mental State, Minimum Data Set, GHQ-30 | Apoe | Medication use (antidepressants, BZD), Postmortem brain examination | ||

| Melton Osteoporotic Fracture | + | + | + | Clifton Assessment Procedure for the Elderly (cognition) | Snellen test (visual acuity) | BMI, Dietary assessment, physical activity, medication, Fall history, fractures, Physical performance: mobility, balance, 10 min walk, stand up from chair, handgrip US of the calcaneus | ||

| Million Women Study | + | + | Yes, no details | Reproductive history, HRT and OC use, familial history of cancer, lifestyle habits (diet, alcohol, tobacco), Early life events, Mammography | ||||

| Netherlands cohort study on diet and cancer | + | + | Toenail clipping | Dietary assessment, medication use, Family history of cancer, smoking | ||||

| Nordic Research on Ageing (NORA) | Interview | + | + | CES-D | Physical performance: muscle strength, stair-mounting test | |||

| North London Eye Study | + | Diabetes | Ophthalmological evaluation | |||||

| Nottingham Longitudinal Study of Activity and Ageing | + | + | + | Physical activity and performance: grip strength, mobility, Lifestyle habits | ||||

| Odense Study (EURODEM) | + | + | CAMCOG, CAMDEX, neuropsychological tests (trail making, Symbol Digit, Benton Boston and Token tests). CDR | |||||

| Personnes âgées QUID? PAQUID | + | + | CES-D, MMSE, neuropsychological tests (Benton, Wechsler) | + | Lipids, hormones | Apoe (sub-sample) | BMI, Dietary assessment, medication use, Home visits | |

| Rotterdam Study | + | + | + | MMSE, CES-D, GMS-organic, battery of other tests | Vision | Lipids, markers of inflammation (CRP, IL-6), hormones, Thyroid antibodies, Clotting, Homocystein, Vitamins, ferritin, caerulopasmin, and other (some in subset only) | Apoe, Polymorphism of hormones receptors, Myocilin mutation, Factor V Leiden, and other (some in subset only) | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, ECG, US of carotid arteries, cerebral MRI, Bone density, RX of knee, Ophthalmological examination, Dietary assessment |

| Study of men born in 1913/study of men born in 1914 | + | + | + | Neuropsychological tests (Men born in 1914) | Hearing | Blood count, lipids, chemistry, PSA, sex hormones, insulin, coagulation factors | Activated C protein resistance | Blood pressure, BMI, ECG, RX of chest, Physical examination, 24-h ECG, echocardiography, US of carotid and peripheral arteries, Lung function, Test of audition |

| Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (2004) | + | + | + | + | Professional occupation and retirement, economics, social situation, intergenerational relationships, health services utilisation | |||

| Swiss Evaluation of the methods of Measurement of the Osteoporotic Fracture risk (SEMOF) | + | + | + | + | Markers of bone metabolism in serum and urine | BMD (DXA and US) | ||

| Tampere Longitudinal Study of Ageing (TamELSA) | + | + | + | + | Medication use, Incontinence | |||

| Zutphen Elderly Study | + | + | + | MMSE Courtald Emotional Control Scale | Lipids, hematocrit, insulin, C-peptide, albumin, creatinine | Blood pressure, BMI, Detailed dietary assessment (vitamins, glycemic index...), Functional performance measured in some individuals (validation of self-report instrument) | ||

| United States (USA) and Canada (CA) | ||||||||

| Asset and Health Dynamics among the Oldest Old (AHEAD), with HRS from 1998 | + | + | + | + | BMI | |||

| Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study (ARIC) | + | + | Blood count, coagulation factors, lipids, chemistry, renal function | No details | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, ECG, echocardiogram | |||

| Buck Centre for Research in Ageing (BCRA), Health and Function cohort | + | + | + | Short Portable Mental Status CES-D | + | No detailed data | Blood pressure, Physical performance: balance, stand up from chair, Extensive visual examination in a subset | |

| Canadian Study of Health and Ageing (CSHA), Etude Santé et Vieillissement au Canada | + | + | + | MMSE, CES-D, Zarit’s Burden Scale, Ryff’s wellbeing measure | Folate, vitamin B12 | Apoe | BMI, Neuropsychological examination | |

| Cardiovascular Health Study (CHS) | + | + | + | + | Lipids, IL-6, CRP, coagulation, fructosamine | + | Blood pressure, ankle blood pressure, BMI, Lung function, ECG, echocardiography, Physical performance: 6 min walk | |

| Established Populations for Epidemiologic Studies of the Elderly (EPESE) | + | + | + | CES-D+MMSE | Blood count, albumin, IL-6, at year 6 | Apoe | BMI, Physical performance: walking speed, balance, stand up from chair, Data on past hospital admissions | |

| Etude Longitudinale Québécoise sur le Vieillissement (Québec Longitudinal Study on Ageing) | + | + | + | |||||

| Health Ageing and Body Composition (ABC) Study | + | + | + | CES-D, MMSE, assessment of anxiety | Self-report of physician diagnosed impairment | Blood count, chemistry (glucose, hormones, inflammation markers), Urine collection | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, DXA, CT of thigh, Physical performance : 6 min walk, stand up from chair, knee extension, grip strength, Physical activity, Medication use, Lung function | |

| Health and Retirement Study (HRS) and Ageing, Demographics and Memory Study (ADAMS), combined with AHEAD | + | + | + | CES-D | Self-rated vision and hearing | BMI, Physical activity, Physical performance: strength, Leisure activity | ||

| Iowa Women’s Health Study | + | + | Sex hormones, insulin in a small subset | Candidate genes for breast cancer | BMI, W/H ratio, Dietary assessment Reproductive history, HRT, Cancer (total and cause-specific mortality, incidence) | |||

| Longitudinal Study of Ageing I/II (LSOA I/II) | + | + | ADL | + | No performance or physical measure | |||

| MacArthur Studies of Successful Ageing (sub-cohort of EPESE) | + | + | ADL | Short Portable, Mental Status, Boston Naming, Task and other cognitive performance measures | IL-6, uric acid, CRP, albumin, cholesterol, cortisol/ACTH, Urinary cortisol and catecholamins | Apoe (other future analyses not yet determined) | Blood pressure, Physical performance: stand on one leg, walking speed, Lung function | |

| Manitoba Study of Health and Ageing | + | + | CES-D, Self-reported memory loss+modified MMSE | Lifestyle habits, Inhome help services use | ||||

| Massachusetts Health Care Panel Study (MHCPS) | + | + | + | + | Physical performance: test of strength and function, Dietary assessment, Health and dental care services use, Blood pressure, physical performance: balance, stand up from chair, Extensive visual examination in a subset |

|||

| Monongahela Valley Independent Elders Study (MoVIES) | + | + | + | MMSE, CES-D, Neuropsychological tests: Story and word recall, Boston naming, Verbal fluency, Praxis, Clock drawing | + | No detailed data | Apoe | Medication use, Use of health care services |

| Nun Study | + | + | + | + | Biochemicals | Apoe | Autopsy (brain) | |

| Salisbury Eye Evaluation (SEE) | + | + | ADL | MMSE | Visual acuity | Opthalmoscopy, Visual performance, Clinical evaluation, BMI, Physical performance: hand grip, Dietary evaluation | ||

| San Antonio Longitudinal Study of Ageing(SALSA) | + | + | MMSE, GDS | Physical performance: mobility of articulations, walking speed, Mcgill pain map | ||||

| Saunders County Bone Quality Study | + | + | BMI, grip strength, Bone quality assessment (RX+US), Dietary assessment, Use of HRT | |||||

| Study of Osteoporotic Fractures | + | + | + | GDS, modified MMSE | Visual acuity | Serum: sex hormones, osteocalcin, alkaline phosphatase, Urin: telopeptides, pyridinolines | Tumour growth factor, vitamin D receptor, apoe | Blood pressure, ankle-brachial pressure index, BMI, Physical performance: hand grip, gait, balance, Medication use, Physical activity, Dietary assessment, Fall calendar, Bone quality assessment (DXA, US) |

| Victoria Longitudinal Study | + | + | + | Memory Compensation Questionnaire, Bradburn Affect Balance scale | Psychological testing | |||

| Washington Heights-Inwood Columbia Ageing Project (WHICAP) | + | + | + | MMSE, Hamilton rating scale for depression, neuropsychological assessment (10 tests) | Lipids Amyloid-beta peptide | Apoe | Blood pressure, Dietary intake (vitamin, antioxydant), Neurologic examination in subset of subjects | |

| Women’s Health and Ageing Study | + | + | ADL | GDS, SF-36, Anxiety/mastery evaluation, Emotional vitality | Self-report+tests | Blood count, chemistry, albumin, lipids, thyroid hormones, IL-6 | Candidates genes for decline | Physical performance: balance, 4 min walk, functional reach, stand up from chair, hand grip, Physical and clinical examination, Hospital use |

| Asia and South America | ||||||||

| Australian Longitudinal Study of Ageing | + | + | + | MMSE, CES-D, well-being evaluation | Measures of vision+hearing | BMI, W/H ratio, Physical performance: Corrected Arm Muscle Area, grip strength, Physical activity assessment, Numerous cognitive tests, History of falls | ||

| Bambui Health and Ageing Study | + | + | + | Depression and cognitive evaluation | Blood count, Chemistry, Lipids, Chagas disease serology | No details | Blood pressure, ECG, BMI, W/H ratio, triceps skinfold, Health services utilisation (including hospitalization) | |

| Canberra Longitudinal Study | + | + | + | Psychiatric evaluation, cognitive performances | + | − | − | Blood pressure, Smoking, Social support, Physical performance: grip strength, reaction time |

| Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study | + | + | Vision | Vitamine D receptor | BMI, Dietary+physical activity assessment, Reproductive history, Physical performance: strength+balance, History of falls, Bone density (DXA), radiological assessment | |||

| Epidemiologia do Idoso (EPIDOSO) | + | + | ADL | Dysthymia, MMSE | Physical activity, Health services utilisation | |||

| Hong Kong old–old Survey | + | + | Barthel index | GDS, Clifton Assessment Procedure for the Elderly | + | Blood sample in a small subgroup (no details) | Gene polymorphism related to longevity | Blood pressure, BMI, W/H ratio, skinfold thickness, Functional+physical performance: walking test |

| Japanese Longitudinal Studies | + | + | + | + | ||||

| Maracaibo Ageing Study | + | + | + | CDR, MMSE | Hematology, Chemistry, vitamin B12, folic acid, homocystein | Apoe, folate metabolism, presenilinin | Blood pressure, ECG, Holter test, Physical performance treadmill, Dietary evaluation, Anthropometrical measures, Neuropsychiatric evaluation | |

| Shanghai Survey of Dementia | + | + | ADL, Pfeffer, Outpatient, Disability Scale | Chinese MMSE, CES-D | + | No detailed data | Apoe | Neuropsychological tests, The questionnaire of TMIG–LISA was used in this study |

| Tokyo Metropolitan Institute of Gerontol–Longitudinal Interdisciplinary Study on Ageing (TMIG–LISA) | + | + | ADL, TMIG, index of competence (evaluation of higher level of functional capacity) | GDS, index of life satisfaction, self-rated health | +self-report | Blood count, Chemistry, Lipids, Liver enzymes, B2 micro-globulin, sex hormones, Hba1c Urinalysis | Markers of osteoporosis | BMI, skinfold thickness, Physical performance: grip strength, tapping rate, one-leg standing, speed walk, Dental examination, ECG, Dietary assessment, RX of chest, BMD (lumbar) |

The symbol “+” indicates that the study collected data in this domain, but details are not reported here, either because no detailed information was found, or because the amount of information was difficult to summarise. ADL activity of daily living, BMD bone mineral density, BMI body mass index, CAMCOG Cambridge cognitive examination, CAMDEX Cambridge examination for mental disorders of the elderly, CDR clinical dementia rating scale, CES-D Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale, CT computer tomography, DXA dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry, ECG echocardiogram, GDS geriatric depression scale, GHQ general health questionnaire, GMS geriatric mental state, HbA1c glycosylated haemoglobin A1c, IL interleukin, Lp(a) lipoprotein a, MMSE mini-mental state examination, MRI magnetic resonance imaging, RX roentgenogram, SF-36 short form-36 quality of life questionnaire, SIDAM structured interview for the diagnosis of Alzheimer disease, multi-infarct dementia and dementias of other etiology, US ultrasound, W/H ratio waist to hip ratio

A third of the cohorts undertook DNA sampling and analyses. Contrary to our hypothesis, DNA sampling was not undertaken more frequently in the recent studies. In fact, some longitudinal projects, that began before genetic testing was easily available, did collect and store blood samples and are now undertaking these analyses. Other studies collected genetic material during a recent follow-up wave.

While comparing data collected and publication themes, we observed that many cohorts tend to underuse information (data not shown): most papers report results on cardiovascular diseases and dementia, while data on functional status, physical performances or health care utilisation tend to be less frequently reported.

Discussion

Even though we focused on large cohort studies of older persons, the number of studies retrieved was large and populations studied were heterogeneous. The number of publications related to each study was also highly variable and seemed independent of design features. In particular, larger projects did not always lead to a higher number of scientific publications.

It is interesting to observe that some investigators have taken the unique opportunity of longitudinal design in order to collect additional data during follow-up, such as new assessment tools or new technologies like DNA sampling that were often not part of the baseline study protocol.

On the other hand, most studies do collect a great deal of information that is underused in further analyses and publications. Ideally, reasons for assessment of a variable and further use in analytic planning should be decided before the study begins and have valid justification. However, data collection is also influenced by the legitimate concern of collecting data that might be useful later, according to scientific developments and also to compete with other studies (Deeg and Van der Zanden 1991). The gap between variables collected and those used in published analyses might also result from the inability to answer research questions due to insufficient statistical power. Most studies did not recruit participants in a homogeneous age category, but only set a lower age limit at baseline, despite the fact that the health picture is very different at the age of 60 and 80. Studying age-related events might be difficult if the sample size of each age category is small, in particular when attrition over time is taken into consideration. Following a large and homogeneous sample during many years seems necessary to come to valid results.

Finally, there may be insufficient resources available for data analysis, which requests a high level of scientific competence. Underuse of available databases is a very frequent problem in medical studies and more attention should be given to solutions that may overcome this. In particular, allocating time and resources for data analysis and paper redaction is a necessity that might be underestimated by funding sources. Part of the solution is in collaboration and sharing of data among researchers, respecting the huge investment consented by researchers to collect cohort data and to find financial resources.

This work also illustrates the difficulty of retrieving accurate and comprehensive information on this type of study. Depending on the cohort, our initial search strategy retrieved only 30–60% of publications identified by the name or acronym of the cohort on Medline 1966–2003, thus indicating low sensitivity of that initial strategy. We urge researchers to choose a name or acronym at the beginning of the study, to mention it in each related publication, and to create a website, in order to facilitate access to the information.

Then, we had to contact the principal investigators to get accurate and comprehensive results, because information on study design is not always available in published material. For instance, the number of people included at baseline tends to vary from one publication to another, particularly when some assessments were undertaken in a sub-sample only. We therefore recommend that each publication contains a brief but accurate description of the original study design, including more details on participation rates and characteristics of non-participants, or refers to publications describing study design. It would also enable the reader to estimate the representativeness of the population sample under study.

This work of course has some limitations. First, we limited our search to cohorts of subjects that were middle-aged or aged at enrolment. As cohorts recruiting subjects under 50 years were less likely to include a follow-up long enough to observe problems specific to ageing subjects, we decided to exclude such studies from our search. We are, however, conscious that ageing is a continuum, and that any lower limit of age is arbitrary and therefore limits the extent of the results.

Secondly, we excluded studies in developing countries, although ageing of the population will soon be a prevalent problem in these countries also. However, lifestyle, socio-economic circumstances and health care systems are very different in these countries and we believe that many results of these studies would not be applicable to our developed setting and should be studied separately.

Finally, despite our systematic search combined with manual searching, it is of course possible that we overlooked some important projects in the field. Our search on the Internet retrieved other lists of cohort studies, such as the ones from Health Canada (2004), review of longitudinal studies on ageing and from the National Institute on Ageing (2005). When compared to our results, we found that several studies retrieved in our review were not included in these works. Furthermore, our review encompasses a larger number of cohorts, although these databases included studies recruiting young adults as well. Therefore, we think that our review constitutes a valuable resource for researchers involved in geriatric studies, not only as a background for communication and exchanges, but also to foster the use of available resources, to learn from others’ experiences and to help set priorities for future research in ageing communities.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank the investigators of the cohorts for their help in validating our results. Many thanks also to the people who participated in these longitudinal studies.

References

- Anstey KJ, Hofer SM, Luszcz MA. Cross-sectional and longitudinal patterns of dedifferentiation in late-life cognitive and sensory function: the effects of age, ability, attrition, and occasion of measurement. J Exp Psychol Gen. 2003;132(3):470–487. doi: 10.1037/0096-3445.132.3.470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkman LF, Seeman TE, Albert M, Blazer D, Kahn R, Mohs R, et al. High, usual and impaired functioning in community-dwelling older men and women: findings from the MacArthur Foundation Research Network on Successful Ageing. J Clin Epidemiol. 1993;46(10):1129–1140. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(93)90112-E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black DM, Steinbuch M, Palermo L, Dargent-Molina P, Lindsay R, Hoseyni MS, et al. An assessment tool for predicting fracture risk in postmenopausal women. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12(7):519–528. doi: 10.1007/s001980170072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blazer D, Burchett B, Service C, George LK. The association of age and depression among the elderly: an epidemiologic exploration. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1991;46(6):M210–M215. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.6.m210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borchelt M, Horgas AL. Screening an elderly population for verifiable adverse drug reactions. Methodological approach and initial data of the Berlin Ageing Study (BASE). [Review] [33 refs] Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1994;717:270–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb12096.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bosworth HB, Siegler IC. Terminal change in cognitive function: an updated review of longitudinal studies. Exp Aging Res. 2002;28(3):299–315. doi: 10.1080/03610730290080344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brayne C, Huppert F, Paykel E, Gill C. The Cambridge project for later life: design and preliminary results. Neuroepidemiology. 1992;11(Suppl 1):71–75. doi: 10.1159/000110983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busse A, Sonntag A, Bischkopf J, Matschinger H, Angermeyer MC. Adaptation of dementia screening for vision-impaired older persons: administration of the mini-mental state examination (MMSE) J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(9):909–915. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00449-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casiglia E, Spolaore P, Mormino P, Maschio O, Colangeli G, Celegon L, et al. The CASTEL project (CArdiovascular STudy in the ELderly): protocol, study design, and preliminary results of the initial survey. Cardiologia. 1991;36(7):569–576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi NG, Schlichting-Ray L. Predictors of transitions in disease and disability in pre- and early-retirement populations. J Aging Health. 2001;13(3):379–409. doi: 10.1177/089826430101300304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MF, Uchoa E, Guerra HL, Firmo JO, Vidigal PG, Barreto SM. The Bambui health and ageing study (BHAS): methodological approach and preliminary results of a population-based cohort study of the elderly in Brazil. [Erratum appears in Rev Saude Publica 2000 Jun; 34(3):320] Rev Saude Publica. 2000;34(2):126–135. doi: 10.1590/s0034-89102000000200005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dargent-Molina P, Favier F, Grandjean H, Baudoin C, Schott AM, Hausherr E, et al. Fall-related factors and risk of hip fracture: the EPIDOS prospective study. [Erratum appears in Lancet 1996 Aug 10; 348(9024):416] Lancet. 1996;348(9021):145–149. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)01440-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dartigues JF, Gagnon M, Michel P, Letenneur L, Commenges D, Barberger-Gateau P, et al. The Paquid research program on the epidemiology of dementia. Methods and initial results. Rev Neurol. 1991;147(3):225–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies KM, Stegman MR, Heaney RP, Recker RR. Prevalence and severity of vertebral fracture: the Saunders County Bone Quality Study. Osteoporos Int. 1996;6(2):160–165. doi: 10.1007/BF01623941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg DJ, Van der Zanden GH. Experiences from longitudinal studies of aging: an international perspective. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1991;6:7–22. doi: 10.1007/BF00117109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deeg DJ, van Tilburg T, Smit JH, de Leuw ED. Attrition in the Longitudinal Aging Study Amsterdam. The effect of differential inclusion in side studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2002;55(4):319–328. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(01)00475-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Donnan PT, Thomson M, Fowkes FG, Prescott RJ, Housley E. Diet as a risk factor for peripheral arterial disease in the general population: the Edinburgh Artery Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 1993;57(6):917–921. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/57.6.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorant E, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, Hermus RJ, Sturmans F. Agreement between interview data and a self-administered questionnaire on dietary supplement use. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48(3):180–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dufouil C, Ducimetiere P, Alperovitch A. Sex differences in the association between alcohol consumption and cognitive performance. EVA Study Group. Epidemiology of vascular aging. Am J Epidemiol. 1997;146(5):405–412. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunlop DD, Manheim LM, Sohn MW, Liu X, Chang RW. Incidence of functional limitation in older adults: the impact of gender, race, and chronic conditions. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83(7):964–971. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.32817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino DV, Lichtenstein MJ, Palmer RF, Hazuda HP. Ethnic differences in mini-mental state examination (MMSE) scores: where you live makes a difference. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(5):538–548. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49111.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick AL, Kuller LH, Ives DG, Lopez OL, Jagust W, Breitner JC, et al. Incidence and prevalence of dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(2):195–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52058.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom AR, Kushi LH, Anderson KE, Mink PJ, Olson JE, Hong CP, et al. Associations of general and abdominal obesity with multiple health outcomes in older women: the Iowa Women’s Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(14):2117–2128. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.14.2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fratiglioni L, Grut M, Forsell Y, Viitanen M, Grafstrom M, Holmen K, et al. Prevalence of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias in an elderly urban population: relationship with age, sex, and education. Neurology. 1991;41(12):1886–1892. doi: 10.1212/wnl.41.12.1886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in olders adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56:M146–M156. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganguli M, Belle S, Ratcliff G, Seaberg E, Huff FJ, von der Porten K, et al. Sensitivity and specificity for dementia of population-based criteria for cognitive impairment: the MoVIES project. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1993;48(4):M152–M161. doi: 10.1093/geronj/48.4.m152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greiner PA, Snowdon DA, Greiner LH. The relationship of self-rated function and self-rated health to concurrent functional ability, functional decline, and mortality: findings from the Nun Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1996;51(5):S234–S241. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.5.s234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawranik P. The role of cognitive status in the use of inhome services: implications for nursing assessment. Can J Nurs Res. 1998;30(2):45–65. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Canada, Division of Aging and Seniors, for The Institute of Aging of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Review of longitudinal studies on aging (2004) Information available from: http://www.fhs.mcmaster.ca/clsa/en/links.htm. Accessed 14 July 2004

- Hertog MG, Feskens EJ, Hollman PC, Katan MB, Kromhout D. Dietary antioxidant flavonoids and risk of coronary heart disease: the Zutphen Elderly Study. Lancet. 1993;342(8878):1007–1011. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)92876-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill LR, Klauber MR, Salmon DP, Yu ES, Liu WT, Zhang M, et al. Functional status, education, and the diagnosis of dementia in the Shanghai survey. Neurology. 1993;43(1):138–145. doi: 10.1212/wnl.43.1_part_1.138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho SC, Woo J, Yuen YK, Sham A, Chan SG. Predictors of mobility decline: the Hong Kong old–old study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1997;52(6):M356–M362. doi: 10.1093/gerona/52a.6.m356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15(3 Suppl):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janzon L, Hanson BS, Isacsson SO, Lindell SE, Steen B. Factors influencing participation in health surveys. Results from prospective population study ‘Men born in 1914’ in Malmo, Sweden. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1986;40(2):174–177. doi: 10.1136/jech.40.2.174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Japanese Longitudinal Studies (2004) Japanese Longitudinal Studies: preliminary results presented at the CIFA meeting, Montreal, March 2004

- Jette AM, Branch LG, Berlin J. Musculoskeletal impairments and physical disablement among the aged. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1990;45(6):M203–M208. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.6.m203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones G, Nguyen T, Sambrook PN, Kelly PJ, Gilbert C, Eisman JA. Symptomatic fracture incidence in elderly men and women: the Dubbo Osteoporosis Epidemiology Study (DOES) Osteoporos Int. 1994;4(5):277–282. doi: 10.1007/BF01623352. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jylha M. Ten-year change in the use of medical drugs among the elderly—a longitudinal study and cohort comparison. J Clin Epidemiol. 1994;47(1):69–79. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(94)90035-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kauppinen M, Davidsen M, Valter S. Design, material and methods in the NORA study. Nordic research on ageing. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2002;14(3 Suppl):5–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korten AE, Jorm AF, Jiao L, Letenneur L, Jacomb PA, Henderson AS, et al. Health, cognitive, and psychosocial factors as predictors of mortality in an elderly community sample. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1999;53:83–88. doi: 10.1136/jech.53.2.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krieg MA, Cornuz J, Hartl F, Kraenzlin M, Tyndall A, Hauselmann HJ, et al. Quality controls for two heel bone ultrasounds used in the Swiss Evaluation of the Methods of Measurement of Osteoporotic Fracture Risk Study. J Clin Densitom. 2002;5(4):335–341. doi: 10.1385/JCD:5:4:335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, Bedford C, Taylor M, Ebrahim S. Geographical variation in cardiovascular disease, risk factors, and their control in older women: British Women’s Heart and Health Study. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003;57(2):134–140. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lefrancois R, Hebert R, Dube M, Leclerc G, Hamel S, Gaulin P. Incidence of the onset of disability and recovery of functional autonomy among the very old after one year. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2000;48(2):137–144. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingston G, Hawkins A, Graham N, Blizard B, Mann A. The Gospel Oak Study: prevalence rates of dementia, depression and activity limitation among elderly residents in inner London. Psychol Med. 1990;20(1):137–146. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700013313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maestre GE, Pino-Ramirez G, Molero AE, Silva ER, Zambrano R, Falque L, et al. The Maracaibo Aging Study: population and methodological issues. Neuroepidemiology. 2002;21(4):194–201. doi: 10.1159/000059524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggi S, Zucchetto M, Grigoletto F, Baldereschi M, Candelise L, Scarpini E, et al. The Italian Longitudinal Study on Aging (ILSA): design and methods. Aging Clin Exp Res. 1994;6(6):464–473. doi: 10.1007/BF03324279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxson PJ, Berg S, McClearn G. Multidimensional patterns of aging in 70-year-olds: survival differences. J Aging Health. 1996;8(3):320–333. doi: 10.1177/089826439600800302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDowell I, Hill G, Lindsay J (2001) An overview of the Canadian Study of Health and Aging. Int Psychogeriatr 13(Supp 18) [DOI] [PubMed]

- McGrother CW, Donaldson MM, Clayton D, Abrams KR, Clarke M. Evaluation of a hip fracture risk score for assessing elderly women: the Melton Osteoporotic Fracture (MOF) study. Osteoporos Int. 2002;13(1):89–96. doi: 10.1007/s198-002-8343-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta KM, Simonsick EM, Penninx BW, Schulz R, Rubin SM, Satterfield S, et al. Prevalence and correlates of anxiety symptoms in well-functioning older adults: findings from the health aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51(4):499–504. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meijer WT, Grobbee DE, Hunink MG, Hofman A, Hoes AW. Determinants of peripheral arterial disease in the elderly: the Rotterdam study. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160(19):2934–2938. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.19.2934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menotti A, Mulder I, Nissinen A, Giampaoli S, Feskens EJ, Kromhout D. Prevalence of morbidity and multimorbidity in elderly male populations and their impact on 10-year all-cause mortality: the FINE study (Finland, Italy, Netherlands, Elderly) J Clin Epidemiol. 2001;54(7):680–686. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(00)00368-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mooy JM, Grootenhuis PA, de Vries H, Valkenburg HA, Bouter LM, Kostense PJ, et al. Prevalence and determinants of glucose intolerance in a Dutch Caucasian population. The Hoorn Study. Diabetes Care. 1995;18(9):1270–1273. doi: 10.2337/diacare.18.9.1270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan K. The Nottingham Longitudinal Study of activity and ageing: a methodological overview. Age Ageing. 1998;27(Suppl 3):5–11. doi: 10.1093/ageing/27.suppl_3.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging, U.S. National Institutes of Health (2005) Database of Longitudinal Studies. Information available from: http://www.nia.nih.gov/ResearchInformation/ScientificResources/LongitudinalStudies.htm. Accessed 26 April 2005

- Nazroo J. The English Longitudinal study of Ageing (ELSA): a new data resource on health, economic position, and quality of life for older people. Gen Rev. 2001;11:14. [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen H, Lolk A, Andersen K, Andersen J, Kragh-Sorensen P. Characteristics of elderly who develop Alzheimer’s disease during the next two years—a neuropsychological study using CAMCOG. The Odense Study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 1999;14(11):957–963. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1099-1166(199911)14:11<957::AID-GPS43>3.0.CO;2-B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill TW, Marsden D, Matthis C, Raspe H, Silman AJ. Survey response rates: national and regional differences in a European multicentre study of vertebral osteoporosis. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1995;49(1):87–93. doi: 10.1136/jech.49.1.87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Kempen GI, Deeg DJ, Brilman EI, van Sonderen E, Relyveld J. Functioning, well-being, and health perception in late middle-aged and older people: comparing the effects of depressive symptoms and chronic medical conditions. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46(1):39–48. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01011.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peel NM, McClure RJ, Bartlett HP. Behavioral determinants of healthy aging. Am J Prev Med. 2005;28(3):298–304. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pryer J, Cappuccio FP, Elliott P. Dietary calcium and blood pressure: a review of the observational studies (Review) J Hum Hypertens. 1995;9(8):597–604. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramos LR, Toniolo J, Cendoroglo MS, Garcia JT, Najas MS, Perracini M, et al. Two-year follow-up study of elderly residents in S. Paulo, Brazil: methodology and preliminary results. Rev Saude Publica. 1998;32(5):397–407. doi: 10.1590/S0034-89101998000500001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed D, Satariano WA, Gildengorin G, McMahon K, Fleshman R, Schneider E. Health and functioning among the elderly of Marin County, California: a glimpse of the future. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 1995;50(2):M61–M69. doi: 10.1093/gerona/50a.2.m61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reidy A, Minassian DC, Desai P, Vafidis G, Joseph J, Farrow S, Connolly A. Increased mortality in women with cataract: a population based follow up of the North London Eye Study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2002;86(4):424–428. doi: 10.1136/bjo.86.4.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rockwood K, Fox RA, Stolee P, Robertson D, Beattie BL. Frailty in elderly people: an evolving concept. Can Med Assoc J. 1994;150:489–495. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders PA, Copeland JR, Dewey ME, Gilmore C, Larkin BA, Phaterpekar H, et al. The prevalence of dementia, depression and neurosis in later life: the Liverpool MRC-ALPHA Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22(5):838–847. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.5.838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsick EM, Kasper JD, Guralnik JM, Bandeen-Roche K, Ferrucci L, Hirsch R, et al. Severity of upper and lower extremity functional limitation: scale development and validation with self-report and performance-based measures of physical function. WHAS Research Group. Women’s Health and Aging Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2001;56(1):S10–S19. doi: 10.1093/geronb/56.1.s10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small BJ, Dixon RA, Hultsch DF, Hertzog C. Longitudinal changes in quantitative and qualitative indicators of word and story recall in young–old and old–old adults. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1999;54(2):107–115. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.2.p107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldo BJ, Hurd MD, Rodgers WL, Wallace RB. Asset and health dynamics among the oldest old: an overview of the AHEAD Study. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 1997;52:Spec–20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/52b.special_issue.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stuck AE, Egger M, Hammer A, Minder CE, Beck JC. Home visits to prevent nursing home admission and functional decline in elderly people: systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;287:1022–1028. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.8.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Survey of Health, Ageing and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) (2004) Information available from: http://www.share-project.org. Accessed 14 July 2004

- Suzuki T, Sugiura M, Furuna T, Nishizawa S, Yoshida H, Ishizaki T, et al. Association of physical performance and falls among the community elderly in Japan in a five year follow-up study. Nippon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi—Jpn J Geriatr. 1999;36(7):472–478. doi: 10.3143/geriatrics.36.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang MX, Jacobs D, Stern Y, Marder K, Schofield P, Gurland B, et al. Effect of oestrogen during menopause on risk and age at onset of Alzheimer’s disease [see comment] Lancet. 1996;348(9025):429–432. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)03356-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The ARIC. The Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) Study: design and objectives. Am J Epidemiol. 1989;129(4):687–702. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- The Million Women Study Collaborative Group The Million Women Study: design and characteristics of the study population. Breast Cancer Res. 1999;1(1):73–80. doi: 10.1186/bcr16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tilvis RS, Hakala SM, Valvanne J, Erkinjuntti T. Postural hypotension and dizziness in a general aged population: a four-year follow-up of the Helsinki Aging Study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44(7):809–814. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03738.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van’thof MA, Hautvast JG, Schroll M, Vlachonikolis IG. Design, methods and participation. Euronut SENECA investigators. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1991;45(Suppl 3):5–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Waard F, Collette HJ, Rombach JJ, Baanders-van Halewijn EA, Honing C. The DOM project for the early detection of breast cancer, Utrecht, The Netherlands. J Chron Dis. 1984;37(1):1–44. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(84)90123-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- West SK, Munoz B, Rubin GS, Schein OD, Bandeen-Roche K, Zeger S, et al. Function and visual impairment in a population-based study of older adults. The SEE project. Salisbury Eye Evaluation. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38(1):72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westendorp RG. Leiden research program on ageing. Exp Gerontol. 2002;37(5):609–614. doi: 10.1016/S0531-5565(02)00007-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]