Abstract

Cognitive adaptation in the elderly and the motivated use of temporal and social comparisons set the conceptual frame for the present study. Three research questions were investigated in a sample of 2.129 persons aged between 50 and 90 years. First, the direction of social and temporal comparisons for three domains (physical fitness, mental fitness, psychological resilience) was studied, and findings did show that especially lateral followed by upward comparisons were most frequent under both perspectives; downward comparisons clearly showed the least frequency. Second, the distribution of comparison directions was investigated across four age groups. These analyses showed that upward comparisons increased and lateral comparisons decreased across age groups; differential results were observed for the domains under consideration. Third, the relation between social and temporal comparisons and self-esteem was studied. Results obtained here indicated a motivated use of specific comparison directions since downward social comparisons and upward temporal comparisons were most frequent in persons with low self-esteem. Taken together, the study underlines the different functions of social and temporal comparisons in adulthood and old age; it indicates a predominant need for consensus and consistency, and it highlights the importance of self-esteem in cognitive adaptation.

Keywords: Cognitive adaptation, Social and temporal comparisons, Self-esteem

Introduction

Comparisons as strategies of cognitive adaptation in the elderly

Social and temporal comparisons represent two ways of obtaining self-evaluative information across the life span. Both are used to compare oneself with specific targets on specific dimensions, and both can lead to three possible results: By comparing oneself with a similar other person or with a younger (or older) self, respectively, one may register (1) social consensus or temporal consistency (i.e. “lateral comparison”), (2) discrepancies in the sense of being better (“downward comparison”), or (3) differences in the sense of being worse off (“upward comparison”) than others or in former times. Social and temporal comparisons represent judgements aiming either at the conservation or a “change of the self” to use the notion already introduced by Rothbaum et al. (1982). They may therefore be classified as ways of cognitive adaptation of the ageing self (Brandtstädter and Greve 1994; Heckhausen and Schulz 1995).

It is assumed here that these forms of cognitive adaptation become more pronounced in age and old age, since the ageing individual is progressively confronted with demands implying irreversible losses (e.g. functional impairments, chronic diseases, or losses of loved ones), which do not allow for attempts at “changing the world.” These latter attempts do comprise behavioural acts described in literature as “problem-focussed coping,” “primary control,” or “assimilative coping” aiming at the change and/or re-establishment of a critical life situation (Brandtstädter and Greve 1994; Heckhausen and Schulz 1995; Lazarus and Folkman 1984). While “changing the world,” thus, largely encompasses problem-directed behaviour, “changing the self” covers cognitive processes protecting individual self-esteem and palliating emotional distress in those situations that do no longer allow for the establishment of a status quo ante. Social and temporal comparisons both should serve these adaptive purposes as well as other motives described in the following.

Motives, directions, and effects of social comparisons

The motivational structure underlying social comparisons has been progressively elaborated since Festinger’s (1954) early work, and especially research in naturalistic settings has proved that social comparisons serve several motives (e.g. Taylor 1983; Taylor et al. 1995; for an overview see Buunk and Gibbons 2007). Taylor et al. (1995) assume four motives directing self-evaluation by social comparisons: Self-assessment serving the need to obtain accurate information about oneself when no objective standards are available, which is in line with the motive already postulated by Festinger; self-enhancement as the motive to achieve and maintain a positive sense of self; self-verification as the need to confirm existing cognitions about oneself, and finally self-improvement, being defined as the need to achieve improvement in specific skills. Social comparisons may thus be used to generate information, which serve the assessment and verification of one’s abilities, the enhancement and maintenance of a positive sense of the self, as well as the improvement of specific skills. Taylor et al. (1995) also point out that more than one self-evaluative motive may be present in a given situation exerting an influence on information processing underlying comparison activity.

Especially downward comparisons have been associated with the need of self-enhancement, and findings reported by Rickabaugh and Tomlinson-Keasy (1997) indicate that these are quite frequent in old age. Wills (1981) proposed that under conditions of threat a person will compare downward with others who are worse off because the contrast between him or herself and the comparison target will enable the person to feel better and to stabilize self-esteem (for another position see Tennen and Affleck 1997). Upward comparisons, though indicating an unfavourable comparison, are mostly associated with self-improvement since the comparison with a better-off person should permit to identify and activate one’s own potentials (see Taylor and Lobel 1989). Finally, lateral comparisons should especially serve the motive of self-assessment (Wayment and Taylor 1995). Several studies have shown that the relations between comparison processes and their presumed function in the regulation of the self and subjective well-being have to be elaborated with respect to moderating personality and contextual characteristics (see Buunk and Gibbons 2007). On the side of the personality characteristics, self-esteem—which will be considered in the following—has proven as a significant moderator of the effects that comparisons may have on individual well-being. This characteristic gets special importance for comparison activity in old age, given that self-esteem is clearly at risk of decline in the elderly (Trzesniewski et al. 2004).

Buunk et al. (1990) showed that the two directions of upward and downward social comparison are not intrinsically linked to affect and that under certain conditions both are capable of generating positive or negative affective responses. They argue that an upward comparison provides the information (a) that one is not as well off as everyone and (b) that it is possible to be better than at the present time. This double meaning also applies to a downward comparison since it conveys (a) that one is not as badly off as a target person and (b) that it is possible to get worse. The authors could illustrate in a sample of cancer patients that persons low in self-esteem were more likely to report about negative implications of downward as well as upward comparisons. In her review of social comparison research, Collins (1996) as well elaborates that upward comparisons may have positive effects on mood in persons with high self-esteem and negative effects in those with low self-esteem. Self-esteem therefore may buffer the effects of upward and downward comparisons on subjective well-being.

Besides its moderating function, self-esteem may also serve as a motive underlying comparison activity since it may determine the preference for and choice of specific comparison information. In accordance with Wills (1981) one may assume that persons low in self-esteem with a correspondingly high need for self-enhancement may prefer downward comparison information on selected dimensions since these may help to enhance the self. This effect depends, however, on the identification with the comparison target, which represents a further moderating variable. Collins (1996) as well as Van der Zee et al. (2000) pointed out that the beneficial effect of downward comparisons may only be expected if the person has a low level of identification with the target person; if this is not the case, downward comparisons will result in fear of ending up the same way. A study by Frieswijk et al. (2004) tested this notion; the authors report that downward comparisons only served their self-enhancing function on life satisfaction among frail older persons if the comparison target was perceived as different from them.

With respect to the choice of comparison information, one can also not exclude that under certain conditions similarity (and identification) with the comparison target may also be desired leading to lateral comparisons, which may then have a self-enhancing effect. This may especially apply for irreversible negative age-related changes; lateral comparisons may help here to experience such changes as “normal” given that age peers are perceived to be in the same situation. Lateral comparisons in old age, thus, may also serve the need to normalize and reduce the discrepancies between oneself and other persons; this need has been convincingly described in victims of life crises, who sometimes even construct a false consensus by overestimating the proportion of others with a similar negative experience (Goethals et al. 1991; see also Ferring and Filipp 2000). This need will be considered here as a fifth motive underlying social comparison activity in old age and it may be characterized as consensus motive.

Taken together the motivated generation of social comparison information as well as the effects of these comparisons depend on several moderating variables and hereby especially individual self-esteem, the comparison dimension, and the identification with the comparison target play an important role.

Motives and effects of temporal comparisons

Temporal comparisons seem to have received less attention in research although their importance for subjective well-being in old age lies at hand (see Staudinger 2001; Wilson and Ross 2000). The comparison with a past self may yield a high probability of resulting in an unfavourable judgement indicating the decrease or loss of the dimension under consideration. This risk is fostered by the self-serving motive underlying temporal comparison activity: According to Albert (1977) temporal comparisons should be triggered in time of change and self-consistency should be the predominant motive governing these processes. “Being still the same” in the face of changes (i.e. a lateral comparison) should therefore be the most preferred form of temporal comparison. Supporting evidence for this notion is reported by Ryff (1991); the author compared elderly, middle-aged, and young adults concerning their present and past perceptions of different dimensions of subjective well-being. She reported that the difference between present and past was quite low indicating a similarity or maintenance of prior levels in the group of the elderly whereas the younger groups perceived improvement on all dimensions.

With respect to the number of age-related changes and losses, one might as well expect a heightened probability of upward comparisons stating that things have been better in former times, which should threaten self-consistency as well as subjective well-being (see Filipp et al. 1997). On the other hand, there is evidence that gain dimensions exist as well in old age (at least till the fourth age; Baltes 1987; Baltes and Smith 2003). These may permit downward temporal comparisons stating that one is better off than in former time, which then should have a self-enhancing effect.

Parallel to social comparison processes one may assume several moderating processes that may buffer the effect of upward comparisons under the temporal perspective. Three processes may be listed here: First, rescaling and reappraisal processes may rearrange the importance of loss domains for the self-definition, and depending on these data- or concept-driven processes temporal upward comparisons may loose their impact on subjective well-being (see Brandtstädter and Greve 1994; Brandtstädter 2002). Given that a positive self-esteem is based on a broad range of self-referential dimensions and domains, a second assumption holds that persons high in self-esteem should be enabled to compensate temporal losses in specific domains by perceiving gains in other ones. Third and related to this, lateral and/or downward social comparisons with respect to a loss dimension may buffer the effect of upward comparisons. Being better off or being in the same situation than similar others may therefore help to buffer the effects of being worse off than in former times.

Research questions and hypotheses

In the following, temporal and social comparisons will be studied in a sample of elderly persons being interviewed within the context of the European Study on Adult Well-Being in Luxembourg1 (ESAW; Ferring et al. 2004), and hereby three research questions will be addressed. First, the direction of social and temporal comparisons in three life domains will be inspected and it will be investigated which comparison direction prevails under which perspective. Following the arguments above, especially lateral temporal comparisons indicating consistency of the self may be assumed to predominate here. Concerning social comparison activity no clear profile of results will be hypothesized given that five different motives may direct the generation of social comparison information. In a second step, comparison directions will be inspected across four age groups ranging from 50 to 90 years. Here, it is expected that especially temporal upward comparisons will increase across age groups reflecting the unfavourable balance between losses and gains in old age (Baltes 1987); again no clear-cut hypothesis with respect to the prevalence of certain judgements is formulated for social comparisons. In a third step, the relation between social and temporal comparisons and self-esteem will be explored by investigating groups high and low in self-esteem with respect to predominant comparison directions. It is hypothesized here in accordance with Wills that persons low in self-esteem will show more downward social comparisons than those with comparatively higher self-esteem.

Method

Sample

A stratified sample of 2.129 adults aged 50–90 mainly living independently was selected including both rural and urban areas. The sampling frame was constructed using national statistics on age and gender stratification as well as population density in urban and rural areas of Luxembourg (STATEC 2002). Respondents were contacted by press announcements as well as information material distributed in leisure centres for the elderly informing about the ESAW and asking for participation in an interview. Data were collected by trained interviewers using a structured interview schedule; additionally, respondents completed a questionnaire, which contained the questions described further below and used within this study.

Characteristics of the sample are depicted in Table 1. Here, it gets evident, that the relative weight of the 10-year age groups decreased from younger to older which reflects the age stratification of the general population. Comparable to other European countries, a majority (56%) of older people were women, indicating their greater longevity in developed countries. The majority of the sample (66.2%) was married, followed by widowed (20.3%; 7.7% male, 29.9% female), single (6.3%; 3.6% male, 8.4% female), divorced (6.0%; 6.1% male, 5.9% female), and persons living separately (1.2%; 1.0% male, 1.3% female). The most frequent educational levels were post high school business or trade school (28.6%), high school (21.7%), and secondary school (20.6%). A proportion of 17% reported having a primary school education; 9.7% reported a college and/or graduate education, 1% held a postgraduate degree. Majority of the respondents estimated their overall physical health as “good” (47.2%) or “fair” (36.4%), 12.8% judged overall health as “excellent,” and only 3.9% estimated it as “poor.”

Table 1.

Sample description

| Age group | Urban | Rural | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | ||

| 50–59 | 297 | 243 | 79 | 109 | 728 |

| 41.9 | 29.2 | 35.4 | 29.9 | 34.2 | |

| 60–69 | 289 | 317 | 104 | 117 | 827 |

| 40.8 | 38.1 | 46.6 | 32.1 | 38.8 | |

| 70–79 | 88 | 177 | 32 | 93 | 390 |

| 12.4 | 21.1 | 14.3 | 25.5 | 18.3 | |

| 80–90 | 35 | 96 | 8 | 45 | 184 |

| 4.9 | 11.5 | 3.6 | 12.4 | 8.6 | |

| Total | 709 | 833 | 223 | 364 | 2,129 |

| 33.3 | 39.1 | 10.5 | 17.1 | 100 | |

Absolute and relative frequencies are depicted

The sample was subdivided in four age groups contrasting persons in their fifties, sexagenarians, septuagenarians, and octogenarians. This classification was preferred over a dichotomy of “young old” and “old old,” since it covers more detailed the different tasks and demands associated with ageing. Persons in their fifties are still in working life, may have children living at home, and are normally dealing with the demands of an active work life. Sexagenarians have quitted work life, are receiving retirement incomes and are in general coping with a changed though in most cases desired life situation. Septuagenarians may experience first severe health impairments and personal losses (especially within the second half of this decade), furthermore, facing the end of ones life certainly becomes more salient (especially for men). Octogenarians finally have the highest probability of health problems and loss events, and dealing with one’s mortality becomes quite salient.

Measures

Social and temporal comparisons were assessed by 5-point Likert-type rating scales for three comparison domains using a procedure introduced by Filipp et al. (1997). Three comparison dimensions—physical fitness (PHY), mental fitness (MEN), and psychological resilience (PSY)—were presented for both social and temporal comparisons. These dimensions were chosen as they reflect gain or loss dimensions in age that may be open to interpretative processes to a different degree. Physical fitness represents most clearly a loss dimension in age and—given that most deteriorations of physical fitness are clearly identifiable and visible—palliative re-evaluations of changes on this dimension may therefore be less probable. Mental fitness as the second domain may allow for data- and concept-driven immunization by choosing subjective criteria for the definition of ones personal position in time or towards others. Finally, psychological resilience was chosen as a gain dimension associated with age, given that the elderly evidently have confronted a series of normative and non-normative events fostering their psychological resilience. The defining as well as the comparison criteria underlying this dimension may be largely open to subjective interpretation.

With respect to social comparison, respondents received the instruction “If you think about other men or women of your age, how good or bad are these compared to you? Compared to other men or women my [...] is ....” Assessment of temporal comparisons followed then and here respondents were asked, “Please think now about former times. Do you feel any changes in the following domains compared to former times? Compared to former times my [...] is ....” Both instructions avoided a further specification of the comparison person or the temporal frame, respectively, to leave interpretative space. Ratings for each comparison domain were obtained on a 5-point scale (1 = much worse, 2 = worse, 3 = the same, 4 = better, 5 = much better). Collapsing the rating on “worse” and “much worse” indicated an upward comparison, collapsing the rating on “better” and “much better” indicated a “downward comparison,” and the rating “the same” represented the lateral comparison.

Self-esteem scale

A German Version of the Rosenberg self-esteem scale was used to assess self-esteem (Ferring and Filipp 1996). This scale is widely used and soundly proven with respect to its reliability and validity. It comprises ten items to be answered on a 5-point Likert-type rating scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The composite score computed to indicate individual self-esteem received a high internal consistency of α = .87; split-half reliability estimated according to Spearman’s and Guttman’s formula was quite high as well, a coefficient of r tt = .86 resulting for both estimates.

Results

Direction and combinations of social and temporal comparisons

Frequency of judgement directions in the total sample

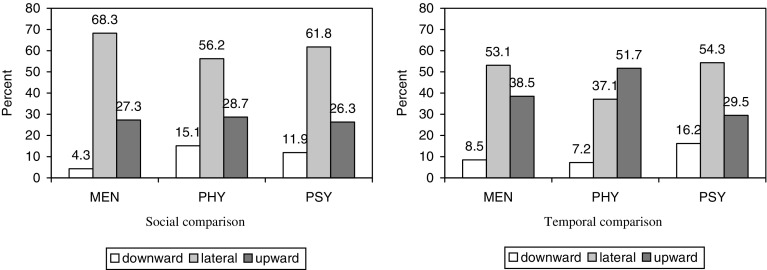

The relative frequencies resulting for the judgement under both comparison directions are depicted in Fig. 1. Here, it gets evident that lateral social comparisons clearly predominated across all three dimensions making up 68.3% of the total ratings for “mental fitness,” 61.8% for “psychological resilience,” and 56.2% for “physical fitness.” The next most frequent category was an upward comparison reflecting a worse condition of mental fitness (27.3%), of physical fitness (28.7%), and of psychological resilience (26.3%) compared to one’s age peers. Downward comparisons resulting in the favourable outcome of being better off were clearly less frequent with a percentage of 4.3% for mental fitness, 12% for psychological resilience, and 15.1% for physical fitness. Taken together, across all three dimensions the majority of respondents stated to be in the same situation than their age peers, followed by a quarter of the sample that registered a worse condition. A lower percentage stated to be better off, and these ratings differed pronouncedly across the three domains.

Fig. 1.

Relative frequencies of social and temporal comparison judgements

With respect to the temporal perspective lateral comparisons did prevail as well for the domain of “mental fitness” (53.1%) and “psychological resilience” (54.3%). Lateral comparisons were less marked for the domain of physical fitness, since only 37.1% of the respondents compared this way; here, upward comparisons reflecting a better condition in former times represented the most frequent category used by approximately 56% of the total sample. Upward comparisons made up for 38.5% of all ratings concerning mental fitness and for 29.5% concerning psychological resilience. Downward comparisons indicating a positive judgement of the current life situation were least frequent under the temporal perspective as well, ranging between 7.2% for physical fitness, 8.5% for mental fitness, and 16.2% for psychological resilience. Comparing these findings to the ones obtained under the social comparison perspective, one may hold the following points: (a) temporal comparison judgements differed more clearly across the three domains reflecting the differential openness of these to construct gains and losses under the temporal perspective; (b) although lateral temporal comparisons still prevailed for two dimensions, the percentage of unfavourable upward comparisons of the current and the past life situations increased more pronouncedly compared to the social perspective; (c) similar to the social perspective downward comparison ratings showed the least percentage.

Frequency analyses of judgement directions across age groups

Overall χ 2-analyses were performed to test the association between age and comparison ratings; if this test reached significance, the distribution of response frequencies observed for upward, lateral, and downward comparisons was inspected across the age groups.2 Overall χ 2-analysis showed that there were significant associations between the age groups and the direction of social comparisons in the domains of mental fitness (χ 2 = 47.0, df = 6, P < .00) and physical fitness (χ 2 = 20.1, df = 6, P < .00); no significant association was found for psychological resilience (χ 2 = 3.03, df = 6).

The inspection of frequencies for social comparison judgements across age groups showed a clear trend indicating a cross-sectional decline of lateral judgements with respect to the domains of mental and physical fitness. This trend was most pronounced for mental fitness: 72% of the first two age groups made a lateral comparison here compared to 62% of the septuagenarians and 49.4% of the octogenarians. With respect to physical fitness, approximately 58% of the first two groups did a lateral comparison, and this percentage declined to 52.3% of the septuagenarians and to 45% of the octogenarians. This decrease was “compensated” by a pronounced increase in upward comparisons for mental fitness; response rates indicating this unfavourable comparison increased from 24.6% in the first two age groups to 32% of the septuagenarians, and to 42.5% of the oldest age group. Upward comparisons concerning physical fitness were also quite pronounced in the oldest group (32.7%), but showed a comparable percentage of 28% in the resting three groups. Finally, downward comparisons increased across age groups. This was most evident for physical fitness: a favourable comparison on this dimension made up for 13.3% of the ratings in the two youngest groups compared to 19.4% of the septuagenarians and 22.2% of the octogenarians. This trend was not that pronounced with respect to mental fitness and might be negligible (see Table 2).

Table 2.

Absolute and relative frequencies of social comparison judgements across four age groups

| Category | Age (years) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–90 | ||

| Mental fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 47.0***) | |||||

| Upward | 179 | 202 | 121 | 73 | 575 |

| 24.6 | 24.5 | 32 | 42.5 | 27.3 | |

| Lateral | 522 | 594 | 234 | 85 | 1,435 |

| 71.9 | 72.0 | 61.9 | 49.4 | 68.3 | |

| Downward | 25 | 29 | 23 | 14 | 91 |

| 3.4 | 3.5 | 6.1 | 8.2 | 4.3 | |

| Total | 726 | 825 | 378 | 172 | 2,101 |

| Physical fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 20.1***) | |||||

| Upward | 208 | 231 | 107 | 56 | 602 |

| 28.6 | 28 | 28.4 | 32.7 | 28.7 | |

| Lateral | 422 | 485 | 197 | 77 | 1,181 |

| 58.0 | 58.7 | 52.3 | 45.0 | 56.2 | |

| Downward | 97 | 110 | 73 | 38 | 318 |

| 13.3 | 13.3 | 19.4 | 22.2 | 15.1 | |

| Total | 727 | 826 | 377 | 171 | 2,101 |

| Psychological resilience (χ 2 (df = 6) = 3.03) | |||||

| Upward | 196 | 211 | 97 | 47 | 552 |

| 27.2 | 25.6 | 25.7 | 27.3 | 26.3 | |

| Lateral | 437 | 524 | 236 | 101 | 1,298 |

| 60.3 | 63.5 | 62.6 | 58.7 | 61.8 | |

| Downward | 91 | 90 | 44 | 24 | 233 |

| 12.6 | 10.9 | 11.7 | 13.9 | 11.9 | |

| Total | 725 | 825 | 377 | 172 | 2,099 |

***P < .00

With respect to the association of temporal comparisons and age group, overall χ 2-analyses yielded significant results for all dimensions and clear cross-sectional trends could be observed (PHY: χ 2 = 55.2, df = 6, P < .00; MEN: χ 2 = 76.1, df = 6, P < .00; PSY: χ 2 = 76.8, df = 6, P < .00). Similar to social comparisons, there was a decrease in lateral comparisons across age groups; this decline was most pronounced for physical fitness, followed by mental fitness, and psychological resilience. While 43.1% of persons in their fifties, 39% of the sexagenarians, and 30% of the septuagenarians made a lateral comparison concerning his or her physical fitness, only 18.5% of the octogenarians did that. With respect to mental fitness, response frequency of lateral comparisons decreased from 59.2% in the youngest to 39.9% in the oldest age group; an equal response rate of 51% resulted for this judgement in the group of sexagenarians and septuagenarians. Lateral comparisons concerning psychological resilience comprised 56% of the responses in the two youngest groups, 51% in the group of septuagenarians, and 47.4% in the oldest group (Table 3).

Table 3.

Absolute and relative frequencies of temporal comparison judgements across four age groups

| Category | Age (years) | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 50–59 | 60–69 | 70–79 | 80–90 | ||

| Mental fitness comparison (χ 2 (df = 6) = 55.2***) | |||||

| Downward | 77 | 74 | 22 | 6 | 179 |

| 10.6 | 8.9 | 5.8 | 3.5 | 8.5 | |

| Lateral | 430 | 427 | 191 | 69 | 1,117 |

| 59.2 | 51.7 | 50.3 | 39.9 | 53.1 | |

| Upward | 219 | 325 | 167 | 98 | 809 |

| 30.1 | 39.3 | 43.9 | 56.7 | 38.5 | |

| Total | 726 | 826 | 380 | 173 | 2,105 |

| Physical fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 76.1***) | |||||

| Downward | 63 | 69 | 14 | 5 | 151 |

| 8.6 | 8.3 | 3.7 | 2.9 | 7.2 | |

| Lateral | 313 | 321 | 114 | 32 | 780 |

| 43.1 | 38.9 | 30.1 | 18.5 | 37.1 | |

| Upward | 350 | 436 | 261 | 136 | 1,173 |

| 48.2 | 52.8 | 66.3 | 78.6 | 55.8 | |

| Total | 726 | 826 | 379 | 173 | 2,104 |

| Psychological resilience (χ 2 (df = 6) = 76.8***) | |||||

| Downward | 163 | 123 | 43 | 11 | 340 |

| 22.5 | 14.9 | 11.3 | 6.4 | 16.2 | |

| Lateral | 406 | 458 | 195 | 82 | 1,141 |

| 56.0 | 55.6 | 51.5 | 47.4 | 54.3 | |

| Upward | 156 | 243 | 141 | 80 | 620 |

| 21.5 | 29.5 | 37.2 | 46.3 | 29.5 | |

| Total | 725 | 824 | 379 | 173 | 2,101 |

***P < .00

As a second analogous trend, there was also a marked cross-sectional increase in upward comparisons describing an unfavourable comparison of the current and past life situation on all three dimensions. Concerning physical fitness, 48% of the youngest group, 53% of the sexagenarians, 66% of the septuagenarians, and 79% of the octogenarians made such a rating. With respect to mental fitness, these ratings comprised 30% in the youngest group, 39% of the sexagenarians, 44% of the septuagenarians, and 57% of the octogenarians. Finally, psychological resilience was also object to growing unfavourable judgement ranging from 21.5% in the first to 46.3% in the last age group.

Downward comparisons, i.e. favourable comparisons of the current with the past life, had the least prevalence on all domains, and this showed a cross-sectional decrease with comparatively clear-cut differences between the four groups. These will be illustrated by contrasting the first and the last group: Downward comparisons ranged here from 22.5 to 6.4% concerning psychological resilience, they decreased from 10.6 to 3.5% across the groups concerning mental fitness, and they decreased from 8.6 to 2.9% concerning physical fitness.

Taken together, results so far indicate that there was a significant association with age for two domains under the social perspective and all three domains under the temporal perspective. Concerning the comparison direction similar profiles were observed for lateral and upward comparisons under both perspectives: (a) there was a cross-sectional decrease of lateral comparisons across the four age groups, (b) upward comparisons, describing an unfavourable result under both perspectives, increased across age groups. A differential profile resulted for downward comparisons: They increased under the social comparison perspective whereas they decreased across the age groups under the temporal perspective. Finally, differential profiles across age groups did not show for the three life domains under consideration.

Self-esteem and comparison direction

In order to analyse the relation between self-esteem and comparison direction χ 2-analyses were performed as well; this non-parametric approach was preferred to a variance analytic procedure since normal distribution and variance homogeneity were not given for any of the comparison ratings. Therefore, continuous self-esteem was categorized into four equal size quartiles indicating low to high levels of self-esteem; trichotomized comparison ratings were used in this analysis as well.

The crosstabulation of self-esteem quartiles and the three response categories for social and temporal comparisons are displayed in Tables 4 and 5. These tables contain the absolute as well as relative frequencies obtained for the response categories (upward, lateral, and downward) within the four quartiles indicating differing levels of self-esteem. Overall χ 2-test was performed for each crosstabulation; if this test yielded a significant result one-dimensional χ 2-tests were performed for each judgement category testing the observed against a uniform distribution. A uniform distribution was chosen as theoretical reference distribution given that it most clearly indicates no differences in the frequency of comparison judgements between different levels of self-esteem.

Table 4.

Crosstabulation of social comparison ratings and groups with differing self-esteem

| Direction | Self-esteem (quartiles) | Total | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Mental fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 88.0***) | ||||||

| Downward | 59 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 90 | 81.91*** |

| 65.6 | 18.9 | 7.8 | 7.8 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 404 | 388 | 339 | 305 | 1,436 | 17.33** |

| 28.1 | 27.0 | 23.6 | 21.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Upward | 127 | 126 | 160 | 159 | 572 | 7.62 |

| 22.2 | 22.0 | 28.0 | 27.8 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 590 | 531 | 506 | 471 | 2,098 | |

| 28.1 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 22.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Physical fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 122.0***) | ||||||

| Downward | 167 | 64 | 47 | 41 | 319 | 130.84*** |

| 52.4 | 20.1 | 14.7 | 12.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 298 | 321 | 299 | 263 | 1,181 | 5.84 |

| 25.2 | 27.2 | 25.3 | 22.3 | 100.0 | ||

| Upward | 126 | 146 | 160 | 169 | 601 | 7.01 |

| 21.0 | 24.3 | 26.6 | 28.1 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 591 | 531 | 506 | 473 | 2,101 | |

| 28.1 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 22.5 | 100.0 | ||

| Psychological resilience (χ 2 (df = 6) = 138.5***) | ||||||

| Downward | 143 | 45 | 36 | 22 | 246 | 148.4*** |

| 58.1 | 18.3 | 14.6 | 8.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 338 | 344 | 325 | 293 | 1,300 | 4.78 |

| 26.0 | 26.5 | 25.0 | 22.5 | 100.0 | ||

| Upward | 109 | 141 | 145 | 155 | 550 | 8.63 |

| 19.8 | 25.6 | 26.4 | 28.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 590 | 530 | 506 | 470 | 2,096 | |

| 28.1 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 22.4 | 100.0 | ||

1 Low, 4 high

***P < .00; **P < .01; *P < .05

Table 5.

Crosstabulation of temporal comparison ratings and groups with differing self-esteem

| Direction | Self-esteem (quartiles) | Total | χ 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |||

| Mental fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 83.8***) | ||||||

| Upward | 298 | 222 | 169 | 116 | 805 | 89.93*** |

| 37.0 | 27.6 | 21.0 | 14.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 246 | 268 | 292 | 311 | 1,117 | 8.60 |

| 22.0 | 24.0 | 26.1 | 27.8 | 100.0 | ||

| Downward | 47 | 41 | 46 | 44 | 178 | .47 |

| 26.4 | 23.0 | 25.8 | 24.7 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 591 | 531 | 507 | 471 | 2,100 | |

| 28.1 | 25.3 | 24.1 | 22.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Physical fitness (χ 2 (df = 6) = 63.4***) | ||||||

| Upward | 393 | 304 | 265 | 210 | 1,172 | 60.73*** |

| 33.5 | 25.9 | 22.6 | 17.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 164 | 178 | 205 | 230 | 777 | 13.24* |

| 21.1 | 22.9 | 26.4 | 29.6 | 100.0 | ||

| Downward | 34 | 48 | 37 | 31 | 150 | 4.40 |

| 22.7 | 32.0 | 24.7 | 20.7 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 591 | 530 | 507 | 471 | 2,099 | |

| 28.2 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 22.4 | 100.0 | ||

| Psychological resilience (χ 2 (df = 6) = 109.1***) | ||||||

| Upward | 267 | 146 | 112 | 92 | 617 | 119.55*** |

| 43.3 | 23.7 | 18.2 | 14.9 | 100.0 | ||

| Lateral | 242 | 299 | 312 | 288 | 1,141 | 9.75 |

| 21.2 | 26.2 | 27.3 | 25.2 | 100.0 | ||

| Downward | 81 | 85 | 83 | 90 | 339 | .58 |

| 23.9 | 25.1 | 24.5 | 26.5 | 100.0 | ||

| Total | 590 | 530 | 507 | 470 | 2,097 | |

| 28.1 | 25.3 | 24.2 | 22.4 | 100.0 | ||

1 Low, 4 high

***P < .00; **P < .01; *P < .05

All overall χ 2-tests were significant describing a non-stochastic association between comparison and self-esteem (see Tables 4, 5). One-dimensional χ 2-tests then showed, that upward and lateral social comparisons were uniformly distributed across the four quartiles of self-esteem indicating that these comparison directions were not systematically associated with differing levels of self-esteem or vice versa. Only one exception existed with respect to this general finding: Lateral comparisons concerning mental fitness did not show a uniform distribution the largest residuals resulting for the group highest in self-esteem (−54) followed by the group lowest in self-esteem (45). Considering the linear dependency of χ 2-statistic to sample size one should however not over-interpret this finding, which indicates that persons highest in self-esteem did perform less lateral comparisons whereas those lowest in self-esteem did perform more lateral comparisons as expected under the assumption of uniform distribution.

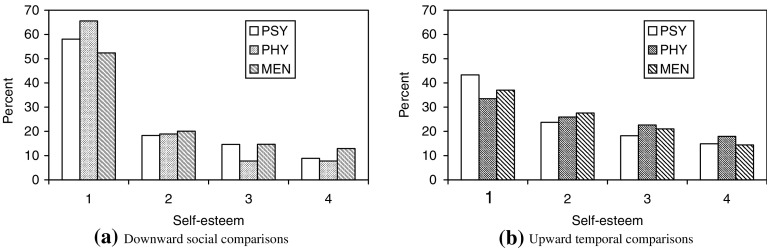

The χ 2-statistics resulting for the response category of downward social comparisons—the judgement that showed the lowest frequency under both comparison perspectives—described a clear trend (see Fig. 2a). All χ 2-values were significant and indicated quite large departures from uniform distribution, because the frequency of downward comparisons was highest within the group with lowest self-esteem and further decreased across the groups. With respect to mental fitness, 65.6% of the downward comparisons—attesting oneself a better or much better condition—were made within the group with lowest self-esteem compared to a response rate of 7.8% in the high self-esteem group. With respect to physical fitness and psychological resilience 52.4 and 58.1% of the downward comparisons were made within the low self-esteem group compared to a proportion of 7.8 and 8.9% in the high self-esteem group.

Fig. 2.

Relative frequencies of a downward social comparisons and b upward temporal comparisons on three dimensions (PSY psychological resilience, PHY physical fitness, MEN mental fitness) across four groups with different self-esteem (1 low self-esteem, 4 high self-esteem)

The result pattern observed for temporal comparisons only partly corresponded with these findings. One-dimensional χ 2-statistics indicated here as well that lateral temporal comparisons were uniformly distributed across the four groups of self-esteem with one exception concerning physical fitness. Here, the group highest in self-esteem showed a higher prevalence of lateral comparisons especially compared with the group lowest in self-esteem; given the small yet significant value of the χ 2-statistic, one should not over-interpret this result as well. Contrary to social comparisons, downward temporal comparisons were also uniformly distributed. Significant deviations from a uniform distribution resulted under the temporal perspective for the category of upward comparisons, indicating an unfavourable comparison between the present and the past life situation, although not as pronounced as for social comparisons. Here, it did show that the majority of upward comparisons were observed within the low self-esteem group; the relative frequency of upward comparisons decreased across groups and was lowest in the high self-esteem group (see Fig. 2b). The differences between the groups with lowest and highest self-esteem ranged between 37 and 14.4% with respect to mental fitness, between 33.5 and 17.9% with respect to physical fitness, and between 43.3 and 14.9% concerning psychological resilience.

Discussion

Social and temporal comparisons have been introduced as ways of cognitive adaptation in age, and the study reported here investigated three research questions concerning this issue. In a first step, the distribution of comparison directions was studied under both perspectives and their distribution across age groups was analysed in a second step. Both analyses served to draw inferences about the motivational structure underlying the comparisons. In a third step, the relation between social and temporal comparisons and self-esteem was investigated, and it was tested if high or low self-esteem goes along with a preference for specific comparisons.

When discussing the notion of cognitive adaptation in age and the role that both comparison processes may play here, one has to refer to the different motives underlying these processes. In general four motives—self-assessment, self-verification, self-enhancement, and self-improvement—are discussed as underlying social comparisons, and here the need to “normalize” ones experiences has been added as consensus motive to this list. Finally and with respect to temporal comparisons in old age, self-consistency has been introduced as the principal motive underlying the generation and use of temporal comparison information.

All motives and associated comparisons with similar others or past times may serve a different adaptive purpose. An accurate self-assessment is essential for action planning in the case of missing objective criteria, and confirming ones self-view by self-verification serves personal consistency (regardless of whether these attributes are positive or negative). All three comparison directions may result under these motives and these may thus be characterized as equifinal: One may feel better, worse or equal to others according to the chosen criteria of self-assessment, and one may confirm ones predominant self-view by feeling better, worse off, or equal to others on a chosen dimension. Contrary to this, specific comparison directions are associated with the following motives. Self-improvement serves the need to advance and further develop ones self and especially comparing with better ones (i.e. upward comparisons) may provide standards for the development of future selves and allow for a positive identification. Self-enhancement is important to avoid feelings of inferiority and reduced self-esteem when the self is under threat and may be served by comparing with persons worse off (i.e. downward comparisons). Consensus information finally may help to normalize age-related changes and here lateral social comparisons may be quite useful.

The need for temporal consistency is served by lateral temporal comparisons and this should guarantee to experience the self as stable and thus avoid restructuring in the face of age-related changes. When discussing the motivational structure of comparison activities one has also to take into account that, several motives may be present in a given situation, and that the most pressing need may prevail in directing comparison activity. Orientation in uncertainty, confirmation of ones self-views, avoiding inferiority and reduced self-esteem, identifying helpful models, and normalizing one’s experiences may thus concur in a given situation, and it is open to discussion which motive will prevail. Findings obtained in the first two steps of analyses gave clear insights into the motivational structure underlying comparison activity in the current sample.

One major finding is that social and temporal comparisons appear to be mainly guided by consensus and consistency information. Given the predominance of lateral social comparisons, self-assessment and/or the need to normalize ones experiences seem to represent the significant motives underlying social comparisons. In line with this, self-consistency and the inference of a stable self seemed to be the principal motive underlying temporal comparisons at least for mental fitness and psychological resilience; it takes, however, no wonder that physical fitness did not allow in such a pronounced extend for the construction of temporal consistency given the multitude and early onset of age-correlated changes in this domain.

The second key finding concerned the prevalence of upward comparisons, which indicate an unfavourable comparison result under both perspectives. Especially, physical fitness and mental fitness represented the domains that were pronouncedly judged to be worse than in former times or worse compared to ones age peers, respectively (making up for 50 and 40% of the responses). Upward comparisons concerning psychological resilience also represented the second frequent response category under both perspectives but were not that pronounced and accounted for a quarter of the total responses. All in all, it is highly likely, that the response rates obtained for upward comparisons indicate deteriorations in the specific domains and thus an accurate self-assessment. This is all the more confirmed by the increase of upward comparisons and the decrease of lateral comparisons across age groups.

Downward comparisons, finally, were least frequent and the motive of self-enhancement linked to this comparison activity—be it under the social or the temporal perspective—seemed to be less prominent. This stands in contrast to findings reported by Rickabaugh and Tomlinson-Keasy (1997), which were obtained in a small sample of 70 older adults by semi-structured interviews. Results may thus reflect certain method specificity in both studies.

All in all, the result patterns is quite convincing given the large sample size and it confirms a view that social and temporal comparisons in the elderly are indicative of motives serving (a) the need for accurate self-assessment and self-consistency as well as (b) the need for normalizing age-related changes. Results confirm as well that social and temporal comparisons were to lesser degree associated with the motives of self-improvement, as indicated by the lower number of upward comparisons, and of self-enhancement, as indicated by the markedly lower number of downward comparisons.

These general findings are further complemented by the inspection of comparisons across age groups. With the exception of social comparisons concerning the “gain-domain” of psychological resilience, quite clear cross-sectional age-trends were found for all domains under the two perspectives. Concerning social comparisons persons in their fifties and sexagenarians showed a comparable profile, and differed in this from the group of septuagenarians and octogenarians. With respect to temporal comparisons, more pronounced differences could be observed across the four age groups. In general, lateral comparisons indicating social consensus and temporal consistency decreased whereas upward comparisons increased across the age groups. As it has been hypothesized, this latter finding was quite pronounced under the temporal comparison perspective. Interestingly, downward social comparisons, though being the less frequent direction, increased across age groups; this may indicate a growing need for self-enhancement for at least some of the respondents, and will be object to subsequent analyses (Ferring and Hoffmann 2007).

The general notion of an accurate self-assessment was also supported by the findings obtained in the analysis of self-esteem and comparison activity under both perspectives. The frequency of lateral comparisons was uniformly distributed across different levels of self-esteem, indicating that these ratings were not influenced by self-serving motives. Furthermore, the number of upward social comparisons and downward temporal comparisons was also not significantly associated with high or low self-esteem. This excludes a self-serving function in the sense of self-improvement by identifying with better off age peers or in the sense of self-enhancement by comparing with worse times in ones past.

A self-serving comparison activity could nevertheless not be totally excluded given the significant associations between downward social comparisons with self-esteem. Individuals low in self-esteem compared significantly more downward by presuming that they were better off than their peers, and this applied for each of the three comparison domains. This result clearly confirms propositions by Wills (1981); it did show as well that the domains under consideration were to a differing degree open for downward comparisons since the lowest proportion of these ratings resulted for physical fitness, followed by psychological resilience and mental fitness.

Interestingly, the low self-esteem group also showed the highest proportion of temporal upward comparisons, maintaining that former times have been better than today. The proportion of both downward social and upward temporal comparisons decreased across the different levels of self-esteem and was lowest within the high self-esteem group. This complements the findings by qualifying the low self-esteem group by its “susceptibility” for upward temporal comparisons, while at the same trying to compensate the potential and harmful effects of this temporal view by a downward social comparison. With increasing self-esteem upward temporal comparisons decreased as well the “necessity” for downward social comparisons.

Taken together, findings did show that lateral and upward comparisons prevailed within the given sample of comparatively healthy elderly people. This response pattern indicated in part a veridical assessment of age-related changes in the large part of the sample, while self-enhancing comparisons activities were observed to a much lesser extent. Furthermore, self-esteem proved to be a potential moderator of comparison activity, since respondents with low self-esteem made more downward social and upward temporal comparisons. Closing, some limitations of the study have to be taken into account. First, findings were obtained in a healthy and autonomously living sample, which may explain the comparatively low percentage of self-enhancing comparisons of the domains under consideration. Second, comparisons were induced via questionnaire, and this procedure does not permit any conclusion about the salience of these processes in real life (see Wood et al. 2000). Third, nothing is known about the comparison targets and time span underlying social and temporal comparisons. A multitude of targets as well as reference time spans exist here, that may have been applied. Social comparison targets could have implied real or fictive persons, and temporal comparisons certainly relied on different time span (especially within the single age groups). Despite these limitations allowing only for a spotlight on comparison processes, the findings indicate the need for consensus and consistency in age and old age and they especially underline the role of self-esteem in cognitive adaptation.

Acknowledgments

This study was part of the European Study on Adult Well-Being that was funded by a grant from fifth Framework Programme (QLK6-CT-2001-00280; Key Action 6.2 “Determinants of healthy ageing and of well-being in old age” in the Quality of Life and Management of Living Resources programme). The authors wish to thank two anonymous reviewers and Tom Michels (University of Luxembourg) for their constructive feedback; special thanks go to Prof. Dr Sigrun-Heide Filipp (University of Trier, Germany) for inspiring previous work on comparison processes.

Footnotes

The ESAW Project was designed as part of the Global Ageing Initiative, originated by the Indiana University Center on Aging and Aged, under the directorship of Dr Barbara Hawkins. ESAW, funded by the European Union, represents a European sub-group of the larger global study. The ESAW group consists of following research teams: Austria: Weber G. (Principal Investigator). Glück J., Heiss C., Sassenrath S.; Italy: Lamura G. (PI). Melchiorre M.G., Quattrini S., Balducci C., Spazzafumo L.; Luxembourg: Ferring D. (PI). Hoffman M., Petit C.; Netherlands: Thissen F. (PI). Fortujin J.D., van der Meer M., Scharf T.; Sweden: Hallberg I.R. (PI). Borg. C., Paulsson C.; United Kingdom: Wenger G.C. (Project Coordinator). Burholt V. (PI). Windle G., Woods B.

Given the different sample sizes of the age groups, these descriptive analyses were not accompanied by further χ2-statistics in order to avoid biased estimates. The results reported here thus have an explorative character.

References

- Albert S. Temporal comparison theory. Psychol Rev. 1977;84:485–503. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.84.6.485. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB. Theoretical propositions of life-span developmental psychology: on the dynamics between growth and decline. Dev Psychol. 1987;23:611–626. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.23.5.611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB, Smith J. New frontiers in the future of aging: from successful aging of the young old to the dilemmas of the fourth age. Gerontology. 2003;49:123–135. doi: 10.1159/000067946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J (2002) Protective self-processes in later life: maintaining and revising personal goals. In: Hofsten Cv, Bäckman L (eds) Psychology at the turn of the millenium. Vol 2: Social, developmental, and clinical perspectives. Psychology Press, Hove, pp 133–152

- Brandtstädter J, Greve W. The aging self: stabilizing and protective processes. Dev Rev. 1994;14:52–80. doi: 10.1006/drev.1994.1003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Gibbons FX. Social comparison: the end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ Behav Hum Decis Process. 2007;102:3–21. doi: 10.1016/j.obhdp.2006.09.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buunk BP, Collins RL, Taylor SE, VanYperen NW, Dakof GA. The affective consequences of social comparison: either direction has its ups and downs. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1990;59:1238–1249. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.59.6.1238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins RL. For better or worse: the impact of upward social comparison on self-evaluations. Psychol Bull. 1996;119:51–69. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.119.1.51. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ferring D, Filipp S-H. Messung des Selbstwertgefühls: Befunde zur Reliabilität, Validität und Stabilität der Rosenberg-Skala [Measurement of self-esteem: findings on reliability, validity, and stability of the Rosenberg-Scale] Diagnostica. 1996;42:284–292. [Google Scholar]

- Ferring D, Filipp S-H. Coping as a “reality construction”: on the role of attentive, comparative, and interpretative processes in coping with cancer. In: Harvey J, Miller E, editors. Loss and trauma. General and close relationship perspectives. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 2000. pp. 146–165. [Google Scholar]

- Ferring D, Hoffmann M (2007) Social and temporal comparisons, self-esteem and personal happiness in age. University of Luxembourg, Luxembourg (unpublished manuscript)

- Ferring D, Balducci C, Burholt V, Thissen F, Weber G, Hallberg-Rahm I. Life satisfaction in older people in six European countries: findings from the European Study on Adult Well-Being. Eur J Ageing. 2004;1:15–25. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0011-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Festinger L. A theory of social comparison processes. Hum Relat. 1954;7:117–140. doi: 10.1177/001872675400700202. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Filipp S-H, Ferring D, Mayer A-K, Schmidt K. Selbstbewertungen und selektive Präferenz für temporale vs. soziale Vergleichsinformation bei alten und sehr alten Menschen [Self-evaluations and selective preference for temporal and social comparison information in old and old old persons] Z Sozialpsychol. 1997;28:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Frieswijk N, Buunk BP, Steverink N, Slaets JPJ. The effect of social comparison information on the life satisfaction of frail older persons. Psychol Aging. 2004;19:183–190. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.19.1.183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goethals GR, Messick DM, Allison ST. The uniqueness bias: studies of constructive social comparison. In: Suls J, Wills TA, editors. Social comparison. Contemporary theory and research. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1991. pp. 149–176. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Schulz R. A life-span theory of control. Psychol Rev. 1995;102:284–304. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.102.2.284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Folkman S. Stress, appraisal, and coping. New York: Springer; 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Rickabaugh CA, Tomlinson-Keasy C. Social and temporal comparisons in adjustment to aging. Basic Appl Social Psychol. 1997;19:307–328. doi: 10.1207/s15324834basp1903_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rothbaum F, Weisz JR, Snyder SS. Changing the world and changing the self: a two-process model of perceived control. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1982;42:5–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.42.1.5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff C. Possible selves in adulthood and old age: a tale of shifting horizons. Psychol Aging. 1991;6:286–295. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.6.2.286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- STATEC (2002) National statistics of Luxembourg. Retrieved from: http://www.statec.lu/html_en/statec/index.html (March 2002)

- Staudinger UM. Life reflection: a social-cognitive analysis of life review. Rev Gen Psychol. 2001;5:148–160. doi: 10.1037/1089-2680.5.2.148. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE. Adjustment to threatening events: a theory of cognitive adaptation. Am Psychol. 1983;38:1161–1173. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.38.11.1161. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Lobel M. Social comparison activity under threat: downward evaluation and upward contact. Psychol Rev. 1989;96:569–575. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.96.4.569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SE, Neter E, Wayment HA. Self-evaluation processes. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 1995;21:1278–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Tennen H, Affleck G. Social comparison as a coping process: a critical review and application to chronic pain disorders. In: Buunk BP, Gibbons FX, editors. Health, coping and well-being: perspectives from social comparison theory. Hillsdale: Erlbaum; 1997. pp. 263–298. [Google Scholar]

- Trzesniewski KH, Robins RW, Roberts BW, Caspi A. Personality and self-esteem development across the lifespan. In: Costa PT Jr, Siegler IC, editors. Recent advances in psychology and aging. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 163–185. [Google Scholar]

- Van der Zee KI, Buunk BP, Sanderman R, Botke G, Van den Bergh F. Social comparison and coping with cancer treatment. Pers Individ Dif. 2000;28:17–34. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00045-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wayment HA, Taylor SE. Self-evaluation processes: motives, information use, and self-esteem. J Pers. 1995;63:729–757. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00315.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills TA. Downward comparison principles in social psychology. Psychol Bull. 1981;90:245–271. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.90.2.245. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson AE, Ross M. The frequency of temporal-self and social comparisons in people’s personal appraisals. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78:928–942. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.78.5.928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wood JV, Michela JL, Giordano C. Downward comparison in everyday life: reconciling self-enhancement models with the mood-cognition priming model. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;79:563–579. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]