Abstract

The present article suggests a tentative new theoretical association between the concept of intergenerational ambivalence and the emotions of guilt and shame in care-giving. The article bases the above suggestion on the paradigm of intergenerational ambivalence as well as on existential and psychological emotion theories dealing with guilt and shame. In certain typical care-giving situations (e.g., leading to institutionalization of the elderly) feelings of guilt can mirror personal-subjective ambivalence (micro level ambivalence) while feelings of shame can mirror institutional-structural ambivalence (macro level ambivalence). The article exemplifies this idea, using an empirical study, which was conducted in Israel (1995), about guilt emotions of care-givers in the Kibbutz versus the city, concerning the institutionalization of an elderly parent. In order to support this innovative concept in the gerontological literature, more updated empirical proof is yet needed. Conclusions and implications of the association between guilt, shame and intergenerational ambivalence are discussed, from theoretical and practical perspectives.

Introduction

The intergenerational ambivalence paradigm is a relatively new theoretical perspective aimed at capturing and describing the complex relationships that characterize the intergenerational family in the post-modern society. This perspective emerged in response to the criticism of the intergenerational solidarity paradigm, which has been used as the major theoretical perspective in family research for the past thirty years (Lowenstein et al. 2001; Bengtson and Roberts 1991). Critics claimed that the solidarity paradigm viewed family relationships in an ideal way, ignoring tensions and unpleasant feelings that are part of every family, and regarding harmony as the main theme necessarily present among family members (Stacey 1990). In response to this criticism, the solidarity paradigm has been revised and renamed “solidarity and conflict paradigm” (Bengtson et al. 2002; Katz et al. 2003).

The ambivalence paradigm views the relationships, emotions, and interactions between family members as part of a complex social system, characterized by many contradictions, experienced by the individual as a simultaneous disagreement between either conflicting cognitions (mind) or conflicting emotions (heart) (Lettke and Klein 2004). This is a different view of the family group than that held by the solidarity and conflict paradigm, in which the family is seen as a system characterized by situations and events that produce either consensus and positive feelings among its members (e.g., affection, attraction and warmth) or negative feelings such as anger and hatred (Marshall et al. 1993). According to the intergenerational ambivalence paradigm these contradictory feelings often occur in a mixed and simultaneous way. In the present times of frequent changes, diverse values, and general instability social relations have changed and are considered to be infused with ambivalence (Bauman 1991). Thus, at present the ambivalence paradigm may better represent the social intergenerational relationships in the family than the solidarity and conflict paradigm, especially when dealing with the institutionalization of an aging parent, a situation shown by research to be inherently charged with ambivalence (Rosenthal and Dawson 1991; Ryan and Scullion 2000).

The debate between the two different perspectives of the family system is ongoing in current family research, and the ambivalence paradigm evolves and develops in the course of this debate. Nevertheless, the exploration of ambivalence in the field of family studies is still in its early stages, theoretically (Lettke and Klein 2004). So far, the most serious attempt of conceptualization is Luescher’s (1999) heuristic model. But according to Luescher (2004), more attempts are yet needed in order to refine the concept of intergenerational ambivalence and discover the various methods in which the concept may be used in research and in clinical practice.

The present article is an innovative attempt aimed at refining our understanding of the concept of intergenerational ambivalence, by associating it to the concepts of guilt and shame. This article claims that in some typical care-giving situations, guilt feelings can be viewed as an overt representation of a covert and hidden subjective ambivalence, specifically when having to make a decision whether to institutionalize a close aging relative (e.g., a parent) or when the onstart of care-giving occurs. Feelings of shame can be used in specific care-giving situations as a representation of structural ambivalence. Shame may be a useful way of representing structural ambivalence because the psychological aim at the foundation of shame is to avoid criticism and rejection (Lazarus and Lazarus 1994). In other words, shame has a strong association with public aspects because it is typically accompanied by a sense of exposure before a real or imagined audience (Covert et al. 2003). This is in contrast to guilt, which does not necessarily involve fear of the opinions of others. Guilt is based mainly on an inner-subjective feeling of uneasiness over possibly having violated a moral code (Lazarus and Lazarus 1994). Because of the differentiation between guilt and shame, it is reasonable to assume that shame is well-suited for representing structural ambivalence, which has to do with social norms, while guilt is better suited for representing subjective ambivalence, which has to do mainly with personal feelings and thoughts.

Intergenerational ambivalence: history and conceptualization

The intergenerational ambivalence perspective of the family system stems from the latest years of the modern era, later elaborated by the postmodern era of the twenty-first century. According to Weigert (1991), this period is characterized by pluralism and multi-valence, placing the individual in constant existential dilemmas of choosing between competing meanings. The multiple meanings cause a psychological experience of ambiguity, stress, and ambivalence characterized by conflicting feelings: The need for liberation and existential freedom (Fromm 1965) on the one hand, and the fear of alienation and this same existential freedom on the other hand, drives individuals to search for group security. The conflicts and contradictions are not only typical of the individual at the micro level but also characterize society as a whole at the macro level. This assumption is the basis of the concept of “sociological ambivalence”, first formulated by Merton and Barber (1963), who define it as incompatible normative expectations of attitudes, beliefs, and behavior.

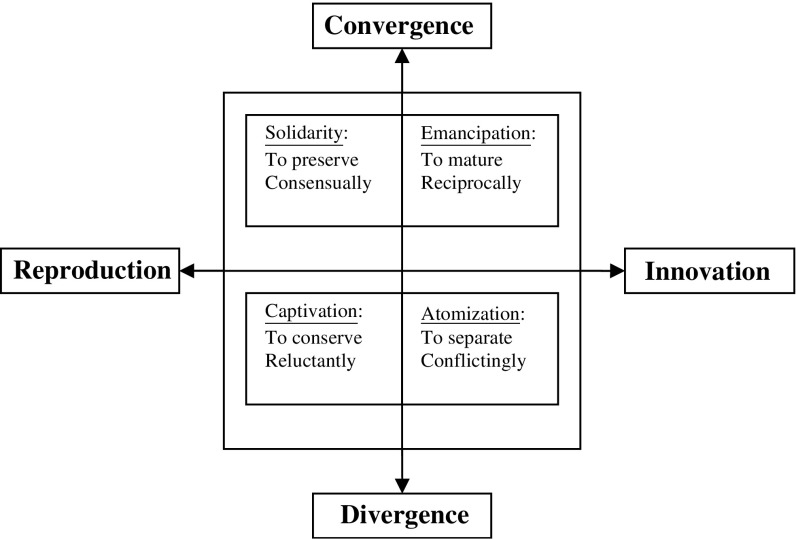

Family researchers have integrated the theories dealing with ambivalence at the personal and interpersonal level (Freud’s theory, 1913/1964, Ainsworth’s 1978 attachment theory) with the theories dealing with ambivalence on the larger social scale (sociological ambivalence) to formulate the concept of intergenerational ambivalence. Generally speaking, intergenerational ambivalence can be defined as simultaneously held conflicting feelings or emotions that are due in part to countervailing expectations about how individuals should act (Luescher and Pillemer 1998; Smelser 1998). More specifically, intergenerational ambivalence is viewed as a concept constructed at two structural levels, macro and micro (Luescher 2004). The macro level captures the social structure as it is represented by societal roles and norms. The micro level concerns the subjective cognitions, emotions, and motivations of the individual in the family. Any attempt to construct a theoretical model of the concept of intergenerational ambivalence should take into account these two levels. Luescher’s heuristic model (1999) captures the two dimensions of ambivalence in the following way (Fig. 1): the structural (macro) dimension is represented by two poles: reproduction and innovation; the inter-subjective (micro) dimension is represented by two other poles: convergence and divergence.

Fig. 1.

The intergenerational ambivalence model

According to Luescher (1999), at the macro level each family system can be seen as a sociological institution characterized by a specific structure as well as by norms and procedures that represent the values and conditions of the larger society in a specific cultural era and geographic place. These institutional values and conditions are, on the one hand, reproduced by the way the family members act out their relations (solidarity, captivation). On the other hand, these values and conditions can be modified (emancipation, atomization), leading to innovations. Hence, reproduction and innovation are two poles where the family is realized as a social institution. In Luescher’s model (1999), these two poles represent structural ambivalence: if one scores highly on both poles, one is viewed as ambivalent, in the structural sense, because the two poles represent opposite themes.

At the micro level, each family can be conceived as an emotional, intimate unit that contains the potential for closeness and subjective identification, reinforcing similarity between children and their parents. On the one hand, this similarity and closeness are psychologically gratifying, but on the other they can also be experienced by family members as a threat to individuality. Thus, family members are motivated to keep the unit’s cohesion (convergence) but at the same time they seek separation and individuality (divergence). Hence, Luescher sees convergence and divergence as two poles representing inter-subjective ambivalence: if one scores high on both convergence and divergence, one is viewed as ambivalent at the micro level.

Following this heuristic model, Lettke and Klein (2004) described research methods and instruments that have been developed and used to measure the degree and frequency of institutional and subjective ambivalence. They divided the various research designs for studying ambivalence according to two criteria: the method of assessing ambivalence (direct vs. indirect) and the paradigm used (qualitative vs. quantitative). The division to direct and indirect methods is based on the notion that the two dimensions of ambivalence can be experienced either directly and consciously (what is called “overt ambivalence”) or they can be present in the family relationships in an unconscious way (“covert ambivalence”). The difference between overt and covert ambivalence should be taken into account in any attempt to conceptualize intergenerational ambivalence, as well as in any attempt to associate this concept to other related concepts, relevant to care-giving, such as guilt and shame.

Guilt and shame: conceptualization and association with gerontology

The emotions of guilt and shame are pervasive affects in our everyday life (Bedford 2004). In everyday language, the terms “guilt” and “shame” are often used interchangeably to describe emotions that are considered detrimental and are best avoided (Dearing et al. 2005). However, much research has demonstrated that these two emotions are distinct, separable, and have different implications for motivation and adjustment (Tangney and Dearing 2002). As defined by Lewis (1971), shame involves a global negative feeling about the self in response to some misdeed or shortcoming, whereas guilt is a negative feeling about a specific event. This definition differentiates between the emotions by two criteria: the target of the emotion (the self vs. an event) and the generality of the negative emotion (specific vs. global). These criteria are later used to draw conclusions about maladjustment and treatment. Thus, while this definition helps us conceptualize guilt and shame, it may not be useful to adopt this line of thought in gerontology research because guilt and shame often arise in care-giving situations, as in the case of the placement of one’s parents in a nursing home (Grau et al. 1993; McGannon 1993; Tobin and Kulys 1981; Virshup 1999). But these emotions arise as part of normal, expected reactions in the process of care-giving of the elderly, and not as a pathological pattern.

A more useful definition of guilt and shame in gerontology research views these emotions as normal, common experiences in everyday human life. Such a definition was suggested by Lazarus and Lazarus (1994), two well-known emotion researchers who adopted an existential perspective of guilt and shame and defined them as two types of anxiety: shame as an anxiety experienced when one has a feeling of having violated a moral code, and guilt when not having stood up to personal ideals of success. Both guilt and shame make one feel anxious about being a failure. In their emotion taxonomy, Lazarus and Lazarus (1994) define anxiety, guilt, and shame as “existential emotions.” Anxiety-fright,1guilt and shame are existential emotions because the threats on which they are based have to do with meanings and ideas about who we are, our place in the world, life and death and the quality of our existence. We have constructed these meanings for ourselves out of our life experience and the values of the culture in which we live and we are committed to preserving them.” (Lazarus and Lazarus 1994, page 41). This existential definition of guilt and shame seems most relevant to gerontology research because of its reference to meaning, life, and death, themes that occupy the elderly and those taking care of them. Because the elderly are nearing death, being close to them is likely to induce some sort of existential anxiety (e.g., guilt and shame). A typical example is the decision of the child caregiver to institutionalize a parent. In this type of decision-making process the caregiver cannot help but think about death, consciously or unconsciously. Wentzel (1978) assumes that one of the reasons caregivers find the decision to institutionalize their elders so difficult is that it makes the caregivers think of their own death.It is not surprising therefore that many empirical studies, mentioned above, found that caregivers of the aging frequently feel guilt and shame. Generally, guilt and shame function as mechanisms of social control (Creighton 1988) and are largely connected to the norms and expectations of society. People feel these emotions when the society in which they live or feel part of makes them believe that they have violated its norms and expectations. For example, black families experienced guilt and felt a community stigma, which caused them shame, when placing their elderly in a nursing home because the norms and expectations in their society were to take care of the elderly at home (Cyr and Schafft 1980). The opposite is also true. When the family receives support from others in the society to institutionalize their elderly, showing that it is normative, legitimate, and accepted, family members feel less guilt and the decision to institutionalize involves less conflict. For example, it was found that when a physician advices the family to institutionalize (Smallegan 1983) the decision to do so is much easier. The same is true when the larger community is involved in the decision and supports it (Jhonson and Werner 1982).

The association between guilt, shame and intergenerational ambivalence

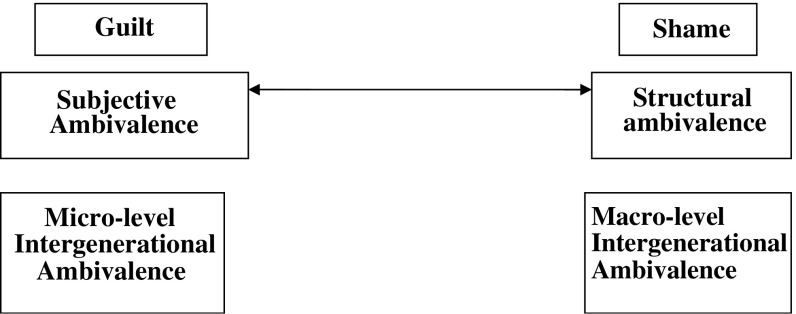

So far, no direct attempt has been made, theoretically or empirically, to associate the concepts of guilt, shame and intergenerational ambivalence, three emotions highly relevant to care-givers today. This article attempts to be the first one offering such an explanatory model (Fig. 2). Since this is a novel attempt, empirical proof is yet needed in order to validate the following model.

Fig. 2.

Guilt, shame and intergenerational ambivalence Existential emotions and the micro/macro levels of ambivalence

As can be seen in Fig. 2, guilt and shame are two distinct existential emotions, which go together, respectively, with subjective and structural ambivalence: While guilt is individually related, thus representing micro-level intergenerational ambivalence, shame is societal related, thus representing macro-level intergenerational ambivalence2At present, this model is yet a theoretical suggestion. Proof is needed to show its validity and its practical and clinical implications. So far, the research of care-giving has not used these three concepts as research variables. Few studies have used two of these three variables together, as part of care-giving research, which concentrated on other issues (since these concepts have not been seen as associated). A detailed example of a study focusing on the decision of care-givers concerning the institutionalization of the elderly, using guilt as a minor variable, will follow. While one study is definitely not enough to validate the theoretical association between the existential emotions and intergenerational ambivalence, it can serve as an initial example of a case-study, showing the future kinds of studies needed to achieve substantial proof of our innovative model.

Two empirical examples of the association between guilt, shame and ambivalence

Some empirical data from two exploratory studies will be presented to reinterpret the association between guilt and inter-subjective ambivalence. The second study refers also to shame and structural-ambivalence. The first is a short description of a study by Lowenstein and Rachman (1995) about the differences between the institutionalization process in the city versus the kibbutz in Israel and the effect on family relationships. These differences are reinterpreted here as showing how the magnitude of guilt feelings in the city versus the kibbutz represent different levels of ambivalence in the two communities concerning institutionalization of an elderly parent in a nursing home.

The second study, a qualitative one, looked at experiences and relationships of older mothers and their adult daughters in the kibbutz versus the city at a point when mothers were at a critical point of becoming physically frail and dependent, needing care and assistance from their daughters. Here the reinterpretation of the data shows both the association between guilt and inter-subjective ambivalence as well as between shame and structural ambivalence (Prilutzky et al. submitted).

The aim of the study by Lowenstein and Rachman (1995) was to reveal and describe the reasons for the decision to institutionalize one’s parents in a nursing home and to analyze the effect of the decision-making process on intergenerational relationships. Another objective was to determine whether this process was different in the city and in the kibbutz. The city and the kibbutz are two distinct sub-cultures in Israel, with different norms and expectations concerning the family. The kibbutz is a unique community, currently in crisis, which until a few years ago, was perceived by its members, as “one big family” (Shapira 1994).3 This affects the expectations of the caregivers in the kibbutz towards their community, to show support for the elders and obligation to them. Conversely, the norms of the kibbutz imply that one is obliged to contribute to the community, functioning primarily as part of the work-force and less as a full-time caregiver (Teresi et al. 1989). By contrast, in the city, society expects children to take care of their aging parents at home, even if that means paying a high economic prize (Berman 1987; Seelbach 1984). Based on this differentiation between city and kibbutz, Lowenstein and Rachman (1995) assumed that the decision process to place one’s parents in a nursing home would arouse greater conflict in the city than in the kibbutz. The amount of stress and burden on the caregiver is much higher in the city than in the kibbutz, with emotional, economic, and physical aspects involved (Lowenstein 1989). In the kibbutz the formal support system is much more accessible than in the city. Several studies found an effective formal support system to be a major factor facilitating the smooth institutionalization of the elderly (Hasselkus 1988; Noelker and Wallace 1985). This is in contrast to the caregiver in the city, who must deal with the bureaucracy of the institutionalization process.

The empirical findings of Lowenstein and Rachman (1995) support these assumptions, as far as feeling of guilt, stress between parents and children, and regret following the decision: all these variables where found to be significantly higher in caregivers living in the city, than in those living on the kibbutz. The findings concerning guilt are the most relevant: whereas 60% of caregivers in the kibbutz hardly felt guilty about the decision to institutionalize their parents, 63.2% of caregivers in the city often felt guilty about the same decision. This is a significant difference between the two Israeli subcultures. These findings concerning guilt were elicited via questionnaires, administrated to care-givers.4

One should bear in mind that this study has not addressed the concept of shame, only the concept of guilt. Thus, it exemplifies only the association between guilt and intergenerational ambivalence. The data from the second study, which will be shortly presented, is reinterpreted looking also at the association between shame and structural ambivalence.

In the second study (Prilutzky et al. ongoing research) the goal was to analyze mother-daughter relationships at a time of transition when mothers begin to show signs of frailty, signaling that caregiving may be needed. Connidis (2001), for example, points out that shifts in support exchange as parents age is a key transition with major consequences for parent-child ties. Fourteen parent-child dyads were interviewed, seven in the city and seven in the kibbutz. All the elderly mothers were widowed, living in separate households. The daughters in the 14 dyads were aged 49–58, all were married and all had two to three children. The interview guide asked questions mainly about the following topics: how do elders and their families construct and make sense of the experience of dependency, i.e., narrative of dependence and changing definitions resulting from failing health; to what extent does the family culture (values and norms) and societal norms influence perceptions about expectations/duties and responsibilities to provide care and support. Two main types of mother–daughter relationships emerged, even though not equally distributed: the first represents a warm-close relationship, the second a warm-conflictual relationship with combined elements of both closeness and conflict. Again differences were evident between the experiences of adult daughters in the city vs. the kibbutz. In the kibbutz the first type was really prevalent whereas in the city the second, the warm-conflictual, was more prevalent expressing many guilt feelings about their inability to answer the mothers’ growing needs for care. Mothers, on the other hand, felt ashamed many times to approach their daughters as the societal norm in the city emphasizes autonomy and if one is needing care one should turn to the welfare state (which is also reflected in the Lon-Term Care Insurance Law of 1988). Congruent with previous studies (e.g., Giarrusso et al. 2005) daughters were more emotionally open to discuss conflicts with their mothers and feelings of guilt, and did not deny their existence, while mothers tended to minimize its impact. If the communication pattern was not open and frank, worries and guilt were mixed, as Mrs. M. (aged 50) describes it:

“...she is a person that gives but does not know how to receive... and I’m afraid that maybe she needs something and I did not notice because I have problems with my own daughter, I am stressed at work and then I feel guilty because I don’t have the energy to look properly after mother...I do not know to whom to turn”

Another example is from a daughter in the city who spoke about her guilt feelings and her mother’s shame to ask for help:

Mrs. S. (aged 49):

...during holidays mother used always to be with us... that means either with me or with my sisters... but as her health declines the situation becomes difficult and we have mixed feelings. She regards her independence as very important and feels shame in asking for help so now she declines our invitations many times... and I feel guilty that I cannot accommodate her but I need my privacy and my life”

In retrospect we maintain that the above findings about guilt in the two studies and about shame as well in the second study can be reinterpreted to represent different levels of subjective intergenerational ambivalence in the two communities, and a level of structural ambivalence, a reasonable tentative indirect inference from the data,5 which uses intergenerational ambivalence as an explanatory concept. However, one should keep in mind that ambivalence was not one of the research variables in the two studies and has not been assessed directly. Thus, at the present state of affairs, these interpretations are tentative and should be tested in future empirical research.

Conclusions and implications

The main conclusion of the present article is that emotions of guilt and shame are promising concepts for refining the model of intergenerational ambivalence, by understanding the link between it’s major concepts and related theoretical concepts (in this case, from emotion research). At the present stage of research this is a tentative conclusion. For its validation, more studies are needed using intergenerational ambivalence as a main research construct (as opposed to an explanatory concept) and correlating it with data about feelings of guilt and shame.

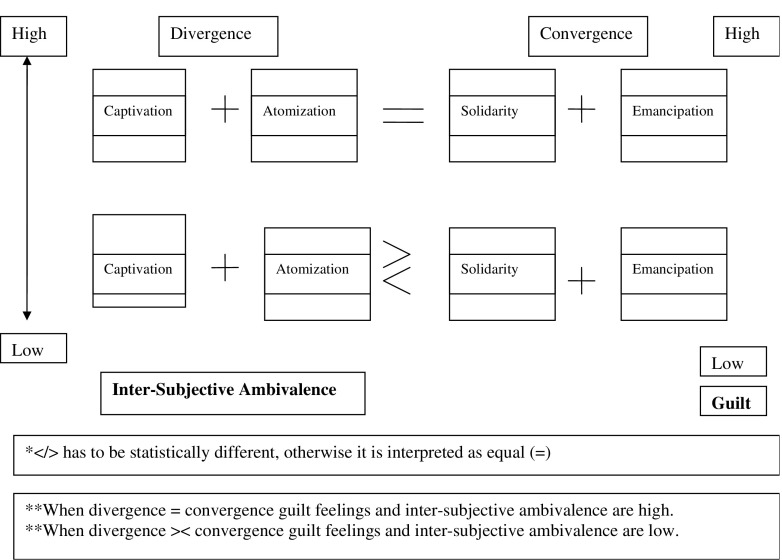

At the theoretical level, we presented the association between intergenerational ambivalence, guilt, and shame clearly. At the empirical level, this association still requires more proof. For example, the claim that the two levels of guilt and inter-subjective ambivalence are positively correlated and thus can serve as a representation of each other might be reflected in Fig. 3, which needs to be empirically tested. This representation is especially important when empirical problems of operationalization of one of the above two constructs exit, as is the case with covert inter-subjective intergenerational ambivalence. This construct is hard to measure, because of its “hidden and academic qualities”. This is in contrast to the construct of guilt, a term which is often used in everyday language by everyone, while ambivalence is a term used by people who have academic or psychological background. The model is based on the following theoretical assumptions:

Inter-subjective intergenerational ambivalence is represented by situations were divergence (emancipation and solidarity) equals convergence (atomization and captivation). When divergence and convergence differ significantly, the person does not feel ambiguity. Thus, this situation is a representation of low feelings of ambivalence.

When convergence and divergence are more or less the same, it means the person feels torn between his need for a united family and his need for separation from it. This contrast makes him feel guilty, after making a decision to choose to act upon one pole of his conflicting needs. The contrast in his opposing emotions often puts him in a moral dilemma, causing guilt.

This postulated theoretical positive association between intergenerational inter-subjective ambivalence has been given some empirical support in the two studies presented above.

Fig. 3.

A suggested relationship between intergenerational inter-subjective ambivalence and guilt

If future research finds guilt and shame indeed to form a valid and sound representation of intergenerational ambivalence, both at the micro and macro levels, it will open the door for further interdisciplinary basic research aimed at linking emotions and relationships in gerontology, studying aging families. Practically and clinically, it can help caregivers of the elderly accept their feelings of guilt and shame as natural and unavoidable, instead of having to struggle with them. Such inner struggle consumes a great deal of emotional energy, placing great stress and burden on caregivers, with negative effects on their well-being, which may have indirect negative effects on the elderly themselves.

Accepting intergenerational ambivalence, and feelings of guilt and shame in care-giving as natural humanistic-existential processes, likely to happen in any family, can have a positive effect on the well-being of the caregivers which in turn can improve the well-being of the elderly recipients of care. Changing the caregivers’ attitude toward their subjective feelings of guilt and shame, as part of their natural existential adjustment, can be seen as a kind of reframing. Reframing is an effective psychological technique, aimed at helping individuals change their point of view about a situation from negative to positive.

Several attempts have already been made in this direction, for example, programs designed to help caregivers deal with their guilt feelings6 (Paton and Lustbader 1994; Schwartz 1977). These programs have a pragmatic orientation but lack a sound theoretical background. If the intergenerational paradigm integrates the concepts of guilt and shame as suggested here, it can serve as the basic theoretical assumption for the development of new programs to help caregivers deal with their guilt, different and perhaps even more effective than earlier programs based on the notion that “guilt is a problem to fix”, an unattainable goal from the existential-humanistic point of view. From the existential-humanistic perspective, the challenge is to accept the natural and unavoidable feelings instead of wasting energy trying to fight them.

If further empirical data will indeed prove the suggested link between guilt, shame and intergenerational ambivalence, specific conclusions should be derived concerning the pragmatic programs, aiming to help care-givers cope with negative emotions. Assuming that guilt is more individual-related, while shame is more societal related, the programs aimed to help care-givers cope with these two distinctive emotions, should differ, concerning the level of their application: While programs aiming to help care-givers cope with guilt should be applied at the individual (micro) level (for example, counseling interventions to families or particular care-givers) programs aiming to help care-givers cope with shame should be applied at the societal (macro) level (for example, radio or television campaigns aiming to convince their audience that putting one’s parents at a nursing home is not shameful. On the contrary: it is a vital step in helping one’s parents cope effectively with their age).

In sum, the idea of guilt and shame as mirroring the micro and macro levels of intergenerational ambivalence is innovative and can have fruitful implications for future theoretical and clinical research. Further research is needed for this idea to realize its full potential.

Footnotes

Lazarus and Lazarus (1994) chose not to differentiate between anxiety and fright because the two terms are usually used interchangeably in everyday language.

The assumption is that the micro and macro levels of ambivalence are distinct, but yet connected. The same is true about guilt and shame: these are two distinct emotions, which are often connected. Since one’s moral internal values, which are the basis of guilt, has been learned through the socialization process, they are connected and often intertwined with one’s feelings of shame, which are external and have to do mostly with the individual’s link to society, and his need not to “loose face” in front of others (to be perceived in a positive way by them).

The perception of the kibbutz as “one big family” was typical at the time the study of Lowenstein and Rachman, which was conducted in 1994. Today, the kibbutz community is going through major changes, including a change in ideological and social structure and this statement may not be an accurate description of the perceptions of all kibbutz members.

Methodologically, the study used both qualitative and quantitative tools: interviews and questionnaires. Reported here are only the quantitative data. The relevant question asked was how often had the care-giver felt guilty after his decision to institutionalize the elderly. Each care-giver had to choose between one of the three possibilities: very often, occasionally, on rare occasions. N = 41 care-givers in the city, N = 10 in the Kibbutz. Average age of care-givers: 48 in the city, 47.3 in the Kibbutz. In the city, the average age of the elderly was 79.8. In the Kibbutz, this average was 80.

The data in the study by Lowenstein and Rachman (1995) was based on interviews and questionnaires administered to the caregivers. The questions had to do with factors relating to the decision to institutionalize, variables having to do with intergenerational relationships (visits, phone calls, frequency of meetings etc.), and a question whether family members believe that they made the right decision about institutionalization. There were no direct questions referring to feelings of ambivalence.

One may wonder why the feeling of guilt is a typical theme in the academic literature of gerontology while feelings of shame appear much less frequently. A possible answer is the typical characterization of shame as the tendency to hide it from the eyes of others.

References

- Ainsworth MD. Patterns of attachment: a psychological study of the strange situation. Hillsdale: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Bauman Z. Modernity and ambivalence. Ithaca: Cornell university press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bedford OA. The individual experience of guilt and shame in Chinese culture. Cult Psychol. 2004;10(1):29–52. doi: 10.1177/1354067X04040929. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Roberts RE. Intergenerational solidarity in aging families: an example of formal theory construction. J Marriage Fam. 1991;53:856–870. doi: 10.2307/352993. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson V, Giarrusso R, Mabry B, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict and ambivalence: complimentary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships? J Marriage Fam. 2002;64:568–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berman JH. Children and their parents: irredeemable obligation and irreplaceable loss. J Gerontol Soc Work. 1987;10(1/2):21–34. doi: 10.1300/J083V10N01_03. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA (2001) Family ties and aging. Thousand Oaks, California, Sage Publications

- Covert MV, Tangney JP, Maddux JE, Heleno NM. Shame-proneness, guilt-proneness, and interpersonal problem solving: a social cognitive analysis. J Soc Clin Psychol. 2003;22(1):1–12. doi: 10.1521/jscp.22.1.1.22765. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Creighton M. Revisiting shame and guilt cultures: a forty-year pilgrimage. Ethos. 1988;18:279–307. doi: 10.1525/eth.1990.18.3.02a00030. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cyr B, Schafft G. Nursing homes and the black elderly: utilization and satisfaction: final report, 1 October 1978–1 October 1979. Washington, DC: Foundation of the American College of Nursing Home Administrators; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addict Behav. 2005;30:1392–1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromm E. Escape from freedom. New York: Avon Books; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. Totem and taboo. London: Hogart; 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso R, Silverstein M, Gans D, Bengtson VL. Aging parents and adult child: New perspectives on intergenerational relationships. In: Johnson M, Bengtson VL, Coleman PG, Kirwood T, editors. Cambridge handbook on aging. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2005. pp. 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- Grau L, Teresi J, Chandler B. Demoralization among sons, daughters, spouses and other relatives of nursing home residents. Res Aging. 1993;15(3):324–345. [Google Scholar]

- Hasselkus BR. Meaning in family care-giving: perspectives on caregiver professional relationships. Gerontologist. 1988;28(5):686–691. doi: 10.1093/geront/28.5.686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jhonson MA, Werner C. We had no choice. A study of familial guilt feelings surrounding nursing home care. J Gerontol Nurs. 1982;8(11):641–645. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-19821101-07. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz R, Daatland SO, Lowenstein A, et al. Family norms and preferences in intergenerational relationship. In: Bengston VL, Lowenstein A, et al., editors. Global aging and challenges to families. New York: Aldine De Gruyter; 2003. pp. 305–326. [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus RS, Lazarus BN. Passion and reason: making sense of our emotions. New York: Oxford University Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Lettke F, Klein MD. Methodological issues in assessing ambivalence in intergenerational relations. In: Pillemer K, Luescher K, editors. Intergenerational Ambivalences: New Perspectives on Parent-Child Relations in Later Life. Oxford: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 85–212. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis HB. Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York: International Universities Press; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A, Katz R, Prilutzky D, Mehlhausen-Hassoen D. The intergenerational solidarity paradigm. In: Daatland SO, Herlofson K, editors. Ageing, intergenerational relations, care systems and quality of life. Oslo: Norwegian Social Research; 2001. pp. 11–30. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A. Institutional placement decision making and impact on family relations of the elderly: a filial crisis. Dubrovnik, Yugoslavia: Paper Presented at the Annual Symposium of the European behavioral and Social Science Research Section of the International Association of Gerontology; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Lowenstein A, Rachman Y. Factors involved in the process of the decision to institutionalize the elderly in a nursing home in the city vs the Kibbutz and the way these factors influence the relationships in the family. Gerontology. 1995;70:31–45. [Google Scholar]

- Luescher K (1999) Ambivalence: A key concept for the study of intergenerational relationship. In: S. Trnka. Family Issues Between Gender and Generations. Seminar report, European observatory on family matters, Vienna

- Luescher K. Conceptualizing and uncovering intergenerational ambivalence. In: Pillemer K, Luescher K, editors. Intergenerational ambivalences: new perspectives on parent-child relations in later life. Oxford: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 23–62. [Google Scholar]

- Luescher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: a new approach to the study of parent-child relations in later life. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:413–425. doi: 10.2307/353858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VM, Matthews SH, Rosenthal CJ. Elusiveness of family life: a challenge for the sociology of aging. In: Maddox GL, Lawton MP, editors. Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: focus on kinship, aging and social change. New York: Springer; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- McGannon A. Families in distress: making a long-term placement for someone with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Alzheimer Care Relat Disord Res. 1993;8(1):2–5. [Google Scholar]

- Merton RK, Barber E. Sociological ambivalence. In: Tityakian E, editor. Sociological theory: values and socio cultural change. New York: Free Press; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Noelker LS, Wallace RW. The organization of family care for impaired elderly. J Fam Issues. 1985;6:23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Paton D, Lustbader W (1994) Rx for caregivers take care of yourself. Seattle, WA: Wendy Lustbader (video)

- Rosenthal CJ, Dawson P. Wives of institutionalized elderly men: the first stage of the transition to quasi-widowhood. J Aging Health. 1991;3(3):315–334. [Google Scholar]

- Ryan AA, Scullion HF. Nursing home placement: an exploration of family careers. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32(5):1187–1195. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2000.01589.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz AN. Survival handbook for children of aging parents. Chicago: Follet Publishing; 1977. [Google Scholar]

- Seelbach WC. Filial responsibility and the care of aging family members. In: Quinn WH, Hughston GA, editors. Independent aging: family and social systems perspectives. Rockville: Aspen; 1984. pp. 92–105. [Google Scholar]

- Shapira Z. The contribution of social support to the welfare of the disabled elderly in the Kibbutz. Gerontology. 1994;66:14–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smallegan M. How families decide on nursing home admission. Geriatr Consult. 1983;1(5):21–24. [Google Scholar]

- Smelser NJ. Presidential address 1997. Am Sociol Rev. 1998;63:1–15. doi: 10.2307/2657473. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stacey J. Brave new families: stories of domestic upheaval in the late twentieth century America. New York: Basic Books; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Dearing RL. Shame and guilt. New York: Guilford; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Teresi J, Holmes D, Holmes M, Bergman S, King Y, Bentur N. Factors relating to institutional risk among elderly members of Israeli Kibbutzim. Gerontologist. 1989;29(2):203–208. doi: 10.1093/geront/29.2.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobin SS, Kulys R. Family in the institutionalization of the elderly. J Soc Issues. 1981;37(3):145–157. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1981.tb00834.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Virshup A. Promises to keep. Smart Money. 1999;8(11):152–160. [Google Scholar]

- Weigert AJ. Mixed emotions. New York: State University Press; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wentzel ML. Emotional considerations in the institutionalization of an aged person. J Health Hum Resour Adm. 1978;1(2):177–185. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]