Abstract

Time spent by physicians is a key resource in health care delivery. This study used data captured by the access time stamp functionality of an electronic health record (EHR) to examine physician work effort. This is a potentially powerful, yet unobtrusive, way to study physicians’ use of time. We used data on physicians’ time allocation patterns captured by over thirty-one million EHR transactions in the period 2011–14 recorded by 471 primary care physicians, who collectively worked on 765,129 patients’ EHRs. Our results suggest that the physicians logged an average of 3.08 hours on office visits and 3.17 hours on desktop medicine each day. Desktop medicine consists of activities such as communicating with patients through a secure patient portal, responding to patients’ online requests for prescription refills or medical advice, ordering tests, sending staff messages, and reviewing test results. Over time, log records from physicians showed a decline in the time allocated to face-to-face visits, accompanied by an increase in time allocated to desktop medicine. Staffing and scheduling in the physician’s office, as well as provider payment models for primary care practice, should account for these desktop medicine efforts.

Physician time is a key resource in health services delivery. Understanding how physicians spend their clinical time is essential, given the need to understand practical capacity; guide staffing, scheduling, and support models in the physician’s office; and improve the accuracy of payment for physician services. Fee-for-service payments are intended to reflect resources (captured as relative value units, or RVUs) used before, during, and after clinical encounters associated with face-to-face ambulatory care visits.1–3 Questions have been raised about whether the reports underlying the RVU estimates are accurate and representative of true physician effort in providing patient care services. In the age of electronic health records (EHRs) with patient portals, patients often request services (such as prescription refills and medical advice) online, without face-to-face visits. Physician effort in addressing these online requests was absent from the original RVU calculations.1–3

In addition to physician reports of their own efforts,2,4,5 researchers have used time-and-motion studies6 and video7 and audio recordings.8 While these methods capture significant physician effort,6,9–11 they are costly to use and often evaluate only a limited number of physicians. Even the resource-based relative values scale (RBRVS) was built, for some specialties, on survey responses to vignettes from about twenty physicians.1 This scale is still the chief tool used to determine the periodic updates to the Medicare Fee Schedule. Furthermore, concerns about the Hawthorne effect preclude ongoing, broad-based direct observation of physician work effort.12

The access logs embedded in EHRs offer an unobtrusive way to study physicians’ use of time. Previous research has used access logs to examine how physicians use EHRs,13–18 to develop local access policies,19 and to detect suspicious access.20 We report here on an innovative use of the access log to study primary care physician work effort.

Similar to a customs agent stamping an international traveler’s passport with the time and place of entry and exit, the EpicCare EHR maintains an access log that tracks many discrete, time-stamped actions associated with patient care. The log records the user, time of access, device from which the EHR was accessed, and section of the EHR section that was accessed (for example, a medication list or lab results). To see how these data might characterize individual primary care physicians’ time spent on ambulatory patient care activities, we developed a method to categorize their work effort as captured in the access log.

The Palo Alto Medical Foundation Institutional Review Board approved the research protocol.

Study Data And Methods

The study used EHR data for the period 2011–14 from 471 physicians in forty-eight primary care departments of four divisions of a community-based health care system. This system contracts with multiple public and private payers and uses fee-for-service payment of physicians according to work RVUs.2 Examples of tasks reflected in the EHR data include typing progress notes (that is, the part of the EHR where physicians document a patient’s clinical status), messaging with patients via the secure patient portal, reviewing test results, and making referrals. Examples of time spent without accessing the EHR include huddling with medical assistants before and after visits, attending meetings, holding hallway discussions, taking breaks, and reading. (We discuss below how time spent using the EHR can approximate time spent face-to-face with patients.)

When a physician was not using the EHR, we could not attribute the time to any specific patient or type of activity; thus, this time was not included in our estimates. We calculated the average daily sum of each physician’s “in and out of clinic time” that could be assigned to specific patients. There was a clear decline in the number of logins to the EHR after 2:00 a.m., which suggested that we could use that hour as the natural end for a given day. Therefore, EHR activities between midnight and 2:00 a.m. were treated as activities that occurred late at night in the previous day.

STUDY SAMPLE

The 471 physicians in our sample documented clinical work in the HER records of 765,129 patients, 637,769 of whom were seen at least once in the 2,842,109 face-to-face ambulatory care visits during the four-year study period. Our analyses were based on logs showing when these physicians accessed the EHR from computers or other devices inside or outside the clinic.

About 62 percent of the physicians started working in the delivery system after it implemented an EpicCare EHR at their site. Equal shares of physicians (36 percent) were in internal and family medicine, and 28 percent were pediatricians. Regarding time spent in the clinic in terms of the share of a full-time equivalent (FTE) position, 52.9 percent of the physicians worked at least 75 percent FTE, 32.1 percent of physicians worked more than 50 percent and less than 75 percent FTE, and 15.1 percent of physicians worked 50 percent FTE or less. The average age of the physicians in 2014 was forty-eight, and 69 percent of them were women.

IDENTIFYING TIME BLOCKS

The underlying unit of our approach, the “time block,” was characterized by four dimensions: the exact time the activity began and ended, patient identification number, the physician accessing the record, and the point of access (which could be a desktop computer in the exam room or at the physician’s desk in the clinic, or a remote secure computer or other device). These data allowed us to create a time block for each workstation-patient-physician combination. Whenever a physician switched patients or workstations, a new time block was created. The time between the end of one block and the start of the next was treated as a “gap” and was not assigned to any patient. There were 31,002,888 time blocks attributed to the 471 physicians in the four-year study period. For an illustration of the kinds of activities that a physician could be engaged in and how we categorized them based on the log data, see the online Appendix.21

CATEGORIZING ENCOUNTER TYPES

To categorize time blocks by clinical work activities,1,3,22 we used the types of EHR fields accessed within each time block. Our mapping of Epic encounter types to the categories of physician work follows the approach used by Richard Baron,22 whose categories were face-to-face ambulatory care visits,

This method of analyzing physician work has far-reaching implications for payment reform.

telephone calls, prescription refills, orders only, and secure messaging to patients. EHR access was considered to have occurred during a face-to-face visit if it was made from an exam room on a day when the patient saw the physician. Some of the documentation reviewed during visits might have been for services provided elsewhere. For example, during a face-to-face visit, a physician might review EHR documentation related to hospital-based services that the patient had had in the past.

ESTIMATING FACE-TO-FACE VISIT TIME

To estimate the length of a face-to-face ambulatory care visit, we used the time of the first EHR transaction and the time of the last EHR transaction for that patient in an exam room on a day that the patient saw the physician (for examples of face-to-face time blocks, see Time Blocks B1, B2, and B4 in the Appendix).21

During a face-to-face visit, a physician often accessed the EHR soon after entering the exam room. For instance, he or she might access it while examining or talking to the patient (such as entering certain information or looking up certain lab values). To protect patients’ privacy, physicians almost always log out of the EHR before leaving the exam room. To examine the validity of this approach to estimating time spent face-to-face with patients, we compared visit lengths calculated by log data with two approaches: in-person observation, and audio recordings of visits. On average, the log-based estimates were two minutes shorter than those based on in-person observation and three minutes shorter than those based on audio recordings. For additional detailed information on this validation process, see the second and third paragraphs in the Appendix.21

DESKTOP MEDICINE

Physicians often access charts of patients with appointments before patients’ arrival to order tests; send staff messages; and review test results, prescriptions, or referrals. Phone calls related to patient care are often documented as telephone encounters. While the duration of phone calls is not recorded, the time spent documenting the conversations in the EHR is recorded. Physicians perform similar tasks after patients depart: ordering tests, reviewing results, submitting referrals, and prescribing medications. Access via the Epic application Haiku was included in our measurements of desktop medicine.

MODELING

Descriptive analyses provided information on physicians’ activities as reflected in EHR logs. Linear regression with robust standard errors was used to analyze the association between EHR-recorded work time allocation and physicians’ characteristics, accounting for clustering of patients at the physician level. The dependent variables were the amounts of time spent on face-to-face visits and desktop medicine at the physician-day level. We adjusted for the number of years the physician had used the Epic-Care EHR; the physician’s sex, race, FTE time, and specialty (pediatrics, internal medicine, or family medicine); and average patient score on the Charlson Comorbidity Index.23 The clinic’s adoption of patient-centered practices was measured by recognition by the National Committee on Quality Assurance (NCQA), with level 3 being the highest level of recognition and level 1 the lowest.24

Data management was completed in SAS, version 5.1. Analyses were conducted in both SAS Enterprise Guide, version 5.1, and Stata, version 13.1.

LIMITATIONS

We identified several limitations in this study. First, the estimates of time spent on some activities were imprecise. For example, if a physician did not use the HER at all during a face-to-face visit, our approach would not record any visit time. Likewise, time spent talking on the phone was not captured, nor was time spent on administrative tasks such as those related to insurance preauthorization and workers’ compensation cases.6 There was also the possibility of overestimating time if a physician walked away from the computer without logging out. Epic would force a logout after a period of inactivity, however. The health system also impresses upon all Epic users the importance of securing a computer (that is, logging out) whenever they need to step away from it, out of respect for patients’ privacy (for more information on how the health system addresses inactivity, see the last section of the Appendix).21

Second, we treated time “gaps” conservatively by not allocating them to the care of any patient, although it is quite likely that physicians spent some of those gaps providing patient care (for example, accessing the EHR only after some initial conversation with the patient).

Third, NCQA recognition is a composite measure of the adoption of patient-centered care processes. We did not draw causal inferences about the relationship between providing patient-centered care and time allocation.

Lastly, the individual health care system in our analysis was an early adopter of EHR and uses many EHR functions. The results might not be generalizable to later adopters or those that use fewer functions.25

Study Results

We analyzed 31,002,888 distinct physician-patient-location time blocks logged by 471 physicians through three types of access locations: exam rooms, physicians’ clinic desktop computers, or secure remote computers or other secure devices.

TIME SPENT ON CLINICAL ACTIVITIES

The average daily total logged time was 3.08 hours for face-to-face and 3.17 hours for desktop medicine, for a sum of 6.25 hours (Exhibit 1). For purposes of comparison, the average number of visits per physician per day was 12.3 (median: 12; standard deviation: 5.3) (data not shown). The average number of visits per physician per day was 9.5 (SD: 4.9) for physicians whose FTE was 50 percent or less, 12.1 (SD: 5.2) for those whose FTE was greater than 50 percent and less than 75 percent, and 12.9 (SD: 5.3) for those whose FTE was at least 75 percent. On average, 15.0 (SD: 10.7) minutes were recorded for a face-to-face visit in the exam room.

EXHIBIT 1.

Average hours spent on various activities per physician per day, 2011–14

| Desktop medicine, in clinic | Desktop medicine, remote access | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| In clinic and remote access | On day of visit | On other day | On day of visit | On other day | ||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||

| Activity | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD |

| DESKTOP MEDICINE | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Progress notes | 2.10 | 1.14 | 1.33 | 0.86 | 0.52 | 0.72 | 0.13 | 0.37 | 0.11 | 0.36 |

| Telephone encounters | 0.58 | 0.44 | 0.05 | 0.09 | 0.49 | 0.39 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.04 | 0.15 |

| Secure messages | 0.20 | 0.25 | 0.01 | 0.04 | 0.17 | 0.21 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.03 | 0.11 |

| Prescription refills | 0.10 | 0.13 | 0.00 | 0.02 | 0.09 | 0.12 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.05 |

| Other | 0.18 | 0.23 | 0.02 | 0.08 | 0.13 | 0.19 | 0.00 | 0.03 | 0.02 | 0.10 |

| Subtotal | 3.17 | 1.36 | 1.42 | 0.89 | 1.40 | 0.95 | 0.14 | 0.38 | 0.21 | 0.52 |

|

| ||||||||||

| FACE-TO-FACE MEDICINE | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Ambulatory care visits | 3.08 | 1.65 | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| TOTAL TIME | ||||||||||

|

| ||||||||||

| Total logged time | 6.25 | 2.15 | ||||||||

| Total scheduled time for visits | 7.45 | 2.31 | ||||||||

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from access logs embedded in the electronic health records of 471 physicians. NOTES See the text for descriptions of the desktop medicine activities. Total scheduled time for visits is the time between the beginning of the first scheduled face-to-face visit and the end of the last visit. Hours may not sum to total because of rounding. SD is standard deviation.

Of the time spent on desktop medicine, an average of 2.82 hours was spent in the clinic, with 1.42 hours spent on patients who were seen on the same day and 1.40 hours spent on other patients (Exhibit 1). An average of 0.35 hour was spent on secure remote computers, 0.14 hour for patients who were seen on the same day and 0.21 hour for other patients. The primary desktop medicine activity both in the clinic and remotely was typing progress notes. Physicians generally spent more time on progress notes in the clinic on visit days. Other desktop medicine activities, in descending order of time allotted, were logging telephone encounters, exchanging secure messages with patients, and refilling prescriptions. Common desktop medicine activities for patients not seen that day were orders for services, chart reviews, letters for external use, and scanned documents.

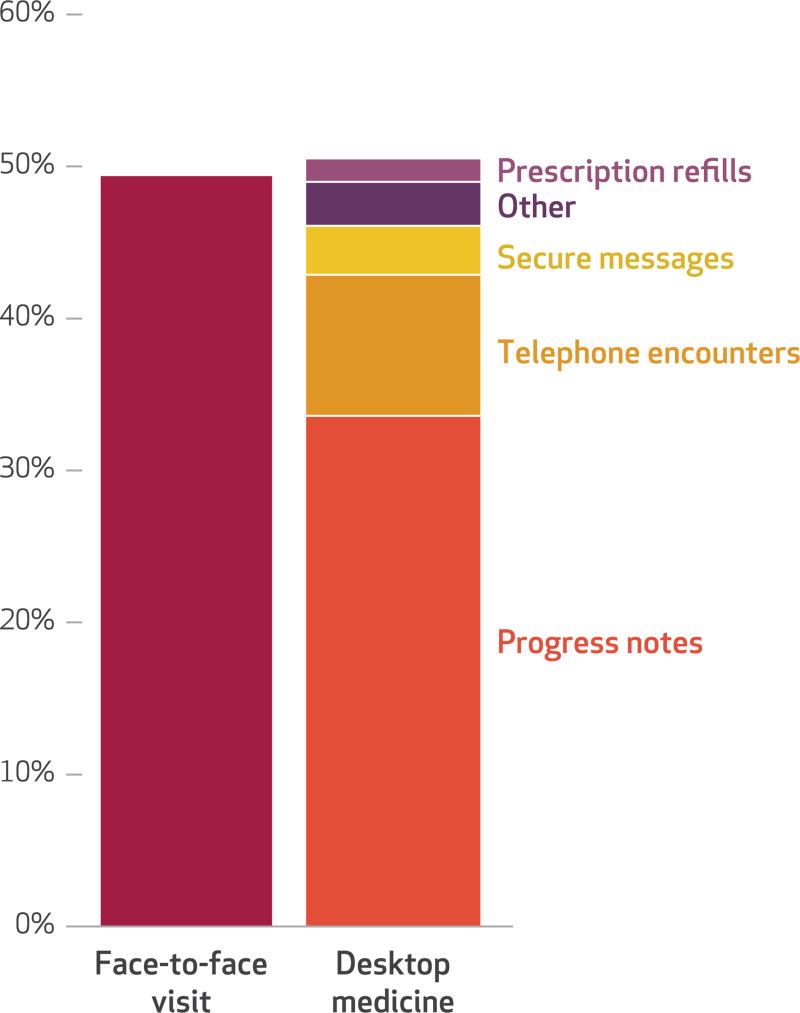

Exhibit 2 displays the distribution of time among face-to-face visits (49 percent) and desktop medicine (51 percent).The desktop medicine portion consists of 34 percent spent on progress notes, 9 percent on documenting telephone encounters, 3 percent on secure message to patients, 2 percent on prescription refills, and 3 percent on other tasks.

EXHIBIT 2. Percentages of physician time spent on various activities, 2011–14.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of access logs embedded in electronic health records of 471 physicians. NOTE The activities in face-to-face medicine are explained in the Exhibit 1 Notes.

TIME ALLOCATION PATTERNS AND PHYSICIAN CHARACTERISTICS

Time allocations for internists and family physicians were roughly comparable, and both recorded more time than pediatricians did on face-to-face visits and desktop medicine (Exhibit 3). For example, internists spent 3.26 hours on face-to-face visits, family physicians spent 3.20 hours, and pediatricians spent 2.72 hours.

EXHIBIT 3.

Average hours spent on various activities per physician per day, by selected characteristics and year

| Face-to-face visit hours per day | Desktop medicine hours per day | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristic or year | Mean | SD | IQR | Mean | SD | IQR |

| SPECIALTY | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Internal medicine | 3.26 | (1.64) | 2.06–4.31 | 3.31 | (1.39) | 2.32–4.11 |

| Family medicine | 3.20**** | (1.60) | 2.03–4.30 | 3.29*** | (1.34) | 2.35–4.12 |

| Pediatrics | 2.72**** | (1.66) | 1.43–3.84 | 2.84**** | (1.30) | 1.91–3.56 |

|

| ||||||

| PORTION OF TIME IN THE CLINIC (PERCENT OF FULL-TIME-EQUIVALENT) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 50% or less FTE | 2.59**** | (1.56) | 1.43–3.49 | 2.52**** | (1.23) | 1.60–3.31 |

| Greater than 50% and less than 75% | 3.04**** | (1.56) | 1.92–4.05 | 3.10**** | (1.33) | 2.15–3.87 |

| 75% or more FTE | 3.19 | (1.70) | 1.93–4.35 | 3.31 | (1.37) | 2.33–4.12 |

|

| ||||||

| NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR QUALITY ASSURANCE RECOGNITION | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Level 3 | 3.15 | (1.60) | 1.98–4.20 | 2.95 | (1.22) | 2.08–3.70 |

| Level 2 | 3.15 | (1.69) | 1.91–4.27 | 3.29**** | (1.39) | 2.31–4.14 |

| Did not apply | 2.87**** | (1.67) | 1.55–4.05 | 3.47**** | (1.54) | 2.36–4.40 |

|

| ||||||

| YEAR | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 2011 | 3.21 | (1.67) | 2.00–4.30 | 3.06 | (1.36) | 2.10–3.84 |

| 2012 | 3.07**** | (1.68) | 1.81–4.21 | 3.16**** | (1.34) | 2.20–3.95 |

| 2013 | 3.00**** | (1.64) | 1.77–4.10 | 3.04** | (1.31) | 2.10–3.83 |

| 2014 | 3.08**** | (1.60) | 1.90–4.18 | 3.37**** | (1.40) | 2.37–4.20 |

| 2011–14 | 3.08 | (1.65) | 1.87–4.19 | 3.17 | (1.36) | 2.20–3.98 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from access logs embedded in the electronic health records of 471 physicians. NOTES Level 3 is the highest of three levels for National Committee for Quality Assurance recognition. SD is standard deviation. IQR is interquartile range.

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

The average recorded face-to-face and desktop medicine time per physician per day also differed across clinics with different NCQA recognition levels. Physicians at clinics with level 3 or level 2 recognition recorded more mean face-to-face hours (3.15 hours in both cases) than those at clinics that didn’t apply for NCQA recognition (2.87 hours). However, the average recorded desktop medicine time for physicians at clinics that did not apply for NCQA recognition (3.47 hours) was higher than for physicians at clinics with level 2 or level 3 recognition (3.29 hours and 2.95 hours, respectively).

Having more years of experience using the EHR was associated with slightly less time spent on desktop medicine (coefficient: −0.04). It is not surprising that physicians whose FTE was 50 percent or less spent less logged time in face-to-face visits (coefficient: −0.51) than physicians whose FTE was 75 percent or higher (Exhibit 4). However, there was no significant difference between physicians in the 50 to <75 percent FTE group (coefficient: −0.10) and those in the 75 percent or higher FTE group. With respect to time allocated to desktop medicine, physicians with <75 percent FTE spent less time on desktop medicine in comparison to those in the 75 percent or higher FTE group.

EXHIBIT 4.

Association between hours spent on various activities and physician characteristics

| Total face-to-face visit time | Total desktop medicine time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|||||

| Characteristic | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI | Coefficient | SE | 95% CI |

| Years using EHR | −0.02 | 0.02 | −0.05, 0.02 | −0.04**** | 0.01 | −0.07, −0.02 |

| Average patient score on Charlson Comorbidity Index | −0.42 | 0.35 | −1.11, 0.27 | 0.15 | 0.30 | −0.43, 0.74 |

|

| ||||||

| PORTION OF TIME IN THE CLINIC (PERCENTAGE OF FULL-TIME-EQUIVALENT) (REF: 75% OR MORE) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 50% or less FTE | −0.51**** | 0.14 | −0.78, −0.25 | −0.49**** | 0.09 | −0.67, −0.31 |

| Greater than 50% and less than 75% | −0.10 | 0.12 | −0.34, 0.13 | −0.21** | 0.09 | −0.39, −0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| SEX (REF: FEMALE) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Male | 0.07 | 0.14 | −0.21, 0.35 | −0.20** | 0.09 | −0.39, −0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| RACE (REF: WHITE) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Asian | 0.16 | 0.13 | −0.10, 0.41 | −0.03 | 0.09 | −0.21, 0.15 |

| Other | 0.91** | 0.39 | 0.14, 1.69 | −0.25 | 0.28 | −0.80, 0.30 |

|

| ||||||

| SPECIALTY (REF: INTERNAL MEDICINE) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Family medicine | −0.20 | 0.17 | −0.54, 0.14 | 0.04 | 0.14 | −0.25, 0.32 |

| Pediatrics | −0.81*** | 0.27 | −1.34, −0.29 | −0.45** | 0.22 | −0.88, −0.02 |

|

| ||||||

| NATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR QUALITY ASSURANCE RECOGNITION (REF: LEVEL 3) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| Level 2 | −0.17 | 0.16 | −0.49, 0.15 | 0.04 | 0.12 | −0.20, 0.27 |

| Did not apply | −0.44** | 0.17 | −0.77, −0.10 | 0.25* | 0.14 | −0.03, 0.53 |

|

| ||||||

| YEAR (REF: 2011) | ||||||

|

| ||||||

| 2012 | −0.11** | 0.04 | −0.19, −0.02 | 0.15**** | 0.03 | 0.09, 0.21 |

| 2013 | −0.16** | 0.06 | −0.28, −0.03 | 0.02 | 0.05 | −0.08, 0.11 |

| 2014 | −0.10 | 0.08 | −0.25, 0.06 | 0.34**** | 0.06 | 0.22, 0.47 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from access logs embedded in the electronic health records of 471 physicians. NOTES The exhibit shows regression results at the provider-day level. National Committee for Quality Assurance recognition is explained in the Exhibit 3 Notes. SE is standard error. CI is confidence interval. EHR is electronic health record.

p < 0.10

p < 0.05

p < 0.01

p < 0.001

Compared to physicians at clinics with level 3 NCQA recognition, those at clinics that did not apply for NCQA recognition recorded less face-to-face time (coefficients: −0.44) but more desktop medicine time (coefficient: 0.25). Compared to 2011, in 2012 and 2013 the recorded face-to-face time was shorter (coefficients: −0.11 and −0.16, respectively), while in 2012 and 2014 the recorded desktop medicine time was longer (coefficients: 0.15 and 0.34, respectively).

Discussion

This is one of the first studies to use EHR access logs that identify discrete, time-stamped activities to account at least partially for how physicians allocate their time. The time recorded for desktop medicine corroborates previous reports of the extensive time spent by physicians on activities outside of direct face-to-face visits.6,9–11 Our results suggest that physicians spent comparable time in face-to-face visits (3.08 hours per day) and desktop medicine (3.17 hours per day). If we add three minutes to face-to-face visit time to account for the time between entry and first login and the time between last logout and exit, the average visit length comes to about 18.0 minutes, which is consistent with the literature.7 Multiplying 18 minutes by 12.3 (the average number of visits per day) gives us an average of 3.69 hours per day spent on face-to-face visits. We acknowledge, however, that this approach omits work efforts that were not captured by log data, such as phone calls and searching for answers to patients’ questions. Findings from a recent direct-observation study of fifty-seven physicians sponsored by the American Medical Association (AMA) showed that about 19.9 percent of physicians’ time per day was spent on tasks other than direct clinical face time, EHR and desk work, and administrative tasks, including personal time, transit time within the clinic, and unobserved work.6 Combining those results with our findings produces an approximation of how physicians spend time in ambulatory practice in the age of EHRs and patient portals: 40 percent is spent on face-to-face visits, 40 percent on desktop medicine, and 20 percent on other activities that are not logged in the EHR.

The logs suggest that physicians allocate equal amounts of their clinically active time to desktop medicine work and to face-to-face ambulatory care visits. While working on progress notes could be considered pre- or post-service efforts,5 desktop medicine activities not linked to a face-to-face visit are not reimbursable under typical fee-for-service contractual and regulatory arrangements. Many of those activities—such as care coordination and responding to patients’ e-mail—are of high value to the delivery system and to patients, so the staffing, scheduling, and design of primary care practices should reflect this value.

Physician burnout with EHR use has been well documented.25,26 Some organizations are using medical scribes to reduce documentation burden.27 Intriguing findings from the recent AMA study on five specialists who had scribes (with their own user identification) suggested that those specialists spent 43.9 percent of their time on face-to-face visits, compared to 23.1 percent among specialists without scribes.6 Clearly, more studies (preferably with more physicians teamed up with scribes) on the impact of scribes are needed. Our data suggested that 34 percent of logged time (2.10/6.25, based on data shown in Exhibit 1) was spent on progress notes. Having scribes support this effort could potentially remove one-third of physicians’ work efforts and might reduce burnout.25 User-specific log data can be used to inform organizations about how scribes as new members of the care team could reduce the time physicians spend on documentation and whether this would increase the time they spend with patients, either face to face or virtually. Furthermore, some organizations offer EHR optimization training for physicians to improve their efficiency in using EHRs.25 Log data could be used to evaluate the impact of these efforts.

IMPLICATIONS FOR RESEARCH

Estimating the time needed for various processes of care has long been an active research area.2,7,28,29 Some researchers have suggested using the time-driven activity-based costing method,29 by asking physicians to use electronic hand-held bar-code or radio frequency identification devices to capture actual times spent on various activities. However, physicians’ receptivity to such approaches is not clear. The unobtrusively collected access log data, while not as precise as those provided by the time-driven activity-based costing method, the process of collecting the log data may be more acceptable to physicians than the process of collecting the other data.

This method of analyzing physician work has far-reaching implications for payment reform. While it may be good or bad that physicians are spending more time documenting care and communicating with other staff members than they are in face-to-face visits with patients, that fact highlights the misalignment of a payment policy that reimburses only office visits, lab work, and procedures while overlooking much of desktop medicine work.

IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY

Twenty-four years after the implementation of the RBRVS-based Medicare Fee Schedule, the Medicare Access and CHIP Reauthorization Act of 2015 established a new framework for Medicare physician payment: the Quality Payment Program. In this program, physicians have two tracks to choose from: the Merit-Based Incentive Payment System and the Advanced Alternative Payment Models.30 Furthermore, CMS has also launched the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model.31 The model has a separate track for practices with relatively more experience in delivering advanced primary care. These practices will receive a hybrid payment of a per beneficiary per month care management fee and fee-for-service payment for claims for evaluation and management services.31 Under this hybrid payment model, practices will have the flexibility to deliver care in the manner that best meets patients’ needs, without being tied to the office visit. This is an explicit move away from payment for visits only, and an acknowledgment that critical aspects of patient care that happen outside the visit require appropriate compensation.

Our research provides empirical data that support this change in physician payment policy. Of the 765,129 patients whose EHRs were accessed by the 471 physicians in the four years of our study, only 637,769 had one or more face-to-face visits. The remaining 127,360 patients received desktop medicine service only. Moreover, consumers increasingly prefer services other than face-to-face visits: A recent survey of several thousand Americans found that 74 percent preferred “virtual” encounters to face-to-face office visits.32 Our results showed that activities associated with virtual encounters included telephone encounters (documenting telephone encounters took up 9 percent of physicians’ logged time), communicating with patients via the secure patient portal (3 percent), and refilling prescriptions (2 percent). Compensation models should make delivering services in ways that meet patients’ preferences the easy thing to do.

CMS has indicated its intention to monitor practices to ensure the delivery of high-quality health care under the Comprehensive Primary Care Plus model. Access logs provide a simple and unobtrusive way for health care delivery systems to examine how their clinicians spend a significant portion of their time. The effective use of such data can help create true learning health systems capable of assessing how best to deploy clinical and other resources to maximize the value of their services to patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (Grant No. HS019167) and Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (Contract No. 1IP2PI000055-01) for funding; Kevin Chen, Gabriel Lewis, Shana Hughes, Caroline Wilson, Eleni Ramphos, and Jenny McKenzie for assistance; and participants at the Sixth Biennial Conference of the American Society of Health Economists for comments on earlier version of the article.

Footnotes

These results were previously presented at the Sixth Biennial Conference of the American Society for Health Economists, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, June 15, 2016.

Contributor Information

Ming Tai-Seale, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute, in Mountain View, California.

Cliff W. Olson, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute.

Jinnan Li, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute.

Albert S. Chan, Sutter Health, in Emeryville, California.

Criss Morikawa, Palo Alto Medical Foundation, in Mountain View, California.

Meg Durbin, Canopy Health, in Emeryville, California.

Wei Wang, Intuit Inc., in Mountain View.

Harold S. Luft, Palo Alto Medical Foundation Research Institute.

NOTES

- 1.Hsiao WC, Yntema DB, Braun P, Dunn D, Spencer C. Measurement and analysis of intraservice work. JAMA. 1988;260(16):2361–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiao WC, Braun P, Dunn D, Becker ER. Resource-based relative values. An overview. JAMA. 1988;260(16):2347–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dunn D, Hsiao WC, Ketcham TR, Braun P. A method for estimating the preservice and postservice work of physicians’ services. JAMA. 1988;260(16):2371–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farber J, Siu A, Bloom P. How much time do physicians spend providing care outside of office visits? Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(10):693–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-10-200711200-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dunn D, Hsiao WC, Ketcham TR, Braun P. A method for estimating the preservice and postservice work of physicians’ services. JAMA. 1988;260(16):2371–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, Prgomet M, Reynolds S, Goeders L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion study in 4 specialties. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(11):753–60. doi: 10.7326/M16-0961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tai-Seale M, McGuire TG, Zhang W. Time allocation in primary care office visits. Health Serv Res. 2007;42(5):1871–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00689.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai-Seale M, Foo PK, Stults CD. Patients with mental health needs are engaged in asking questions, but physicians’ responses vary. Health Aff (Millwood) 2013;32(2):259–67. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2012.0962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gottschalk A, Flocke SA. Time spent in face-to-face patient care and work outside the examination room. Ann Fam Med. 2005;3(6):488–93. doi: 10.1370/afm.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MA, Hollenberg JP, Michelen W, Peterson JC, Casalino LP. Patient care outside of office visits: a primary care physician time study. J Gen Intern Med. 2011;26(1):58–63. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1494-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doerr E, Galpin K, Jones-Taylor C, Anander S, Demosthenes C, Platt S, et al. Between-visit workload in primary care. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1289–92. doi: 10.1007/s11606-010-1470-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Comment letter: CMS’s proposed rule entitled: Medicare program; payment policies under the physician fee schedule, DME face-to-face encounters, elimination of the requirement for termination of non-random prepayment complex medical review, and other revisions to Part B for CY 2013. Washington (DC): MedPAC; 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ES, Cimino JJ. Patterns of usage for a Web-based clinical information system. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2004;107(Pt 1):18–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Natarajan K, Stein D, Jain S, Elhadad N. An analysis of clinical queries in an electronic health record search utility. Int J Med Inform. 2010;79(7):515–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cimino JJ, Li J, Graham M, Currie LM, Allen M, Bakken S, et al. Use of online resources while using a clinical information system. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:175–79. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chen ES, Cimino JJ. Automated discovery of patient-specific clinician information needs using clinical information system log files. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2003;2003:143–49. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fabbri D, LeFevre K, Hanauer DA. Proceedings of the 2011 workshop on data mining for medicine and healthcare. San Diego (CA): Association for Computing Machinery; 2011. Explaining accesses to electronic health records; pp. 10–17. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Adler-Milstein J, Huckman RS. The impact of electronic health record use on physician productivity. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(10 Spec No):SP345–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malin B, Nyemba S, Paulett J. Learning relational policies from electronic health record access logs. J Biomed Inform. 2011;44(2):333–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2011.01.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Boxwala AA, Kim J, Grillo JM, Ohno-Machado L. Using statistical and machine learning to help institutions detect suspicious access to electronic health records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2011;18(4):498–505. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2011-000217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.To access the Appendix, click on the Appendix link in the box to the right of the article online.

- 22.Baron RJ. What’s keeping us so busy in primary care? A snapshot from one practice. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(17):1632–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJMon0910793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90133-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tai-Seale M, Wilson CJ, Panattoni L, Kohli N, Stone A, Hung DY, et al. Leveraging electronic health records to develop measurements for processes of care. Health Serv Res. 2014;49(2):628–44. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, Montague E, Williams E, Schwartz M, et al. Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(e1):e100–6. doi: 10.1136/amiajnl-2013-001875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Meigs SL, Solomon M. Electronic health record use a bitter pill for many physicians. Perspect Health Inf Manag. 2016 Winter;13:1d. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiff GD, Zucker L. Medical scribes: salvation for primary care or workaround for poor EMR usability? J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(9):979–81. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3788-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev. 2004;82(11):131–8. 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaplan RS, Porter ME. How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev. 2011;89(9):46–52. 54, 56–61. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wynne B. For Medicare’s new approach to physician payment, big questions remain. Health Aff (Millwood) 2016;35(9):1643–6. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sessums LL, McHugh SJ, Rajkumar R. Medicare’s vision for advanced primary care: new directions for care delivery and payment. JAMA. 2016;315(24):2665–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.4472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cisco. Cisco study reveals 74 percent of consumers open to virtual doctor visit [Internet] San Jose (CA): Cisco; 2013. Mar 4, [cited 2017 Feb 9]. Available from: http://newsroom.cisco.com/release/1148539/Cisco-Study-Reveals-74-Percent-of-Consumers-Open-to-Virtual-Doctor-Visit. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.