Abstract

Purpose

The primary objective of this study was to assess long-term safety with sublingual asenapine 2.5 or 5 mg twice daily (BID) in patients with schizophrenia.

Patients and methods

Actively treated patients on asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID, or olanzapine 15 mg once daily (QD) who completed a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo- and olanzapine-controlled study continued lead-in treatment in this 26-week, multicenter, double-blind, double-dummy, olanzapine-controlled Phase IIIB extension study; placebo patients were assigned to asenapine 2.5 mg BID treatment. Safety analyses were based on the all treated set (patients who received one or more doses of extension trial medication); change from baseline analyses used the acute study baseline. Treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs) and changes in laboratory parameters were monitored; weight change for asenapine versus olanzapine was the key secondary objective. Descriptive statistics were used; weight change was analyzed using a mixed-model repeated-measure approach.

Results

Of the 120 patients in the all-treated set, 60% completed treatment (asenapine 2.5 mg BID 66.1% overall, asenapine 5 mg BID 52.4%, olanzapine 15 mg QD 56.3%). The incidence of TEAEs was higher for placebo patients from the lead-in study who switched to asenapine 2.5 mg BID for extension treatment (71.0%) versus patients continuing asenapine 2.5 mg BID (38.7%), asenapine 5 mg BID (38.1%), or olanzapine 15 mg QD (25.0%). The most common TEAE (≥5% in every group) was worsening of schizophrenia. Least squares mean change in body weight from the acute study baseline to week 26 was +0.6 kg for overall asenapine 2.5 mg BID, +0.8 kg for asenapine 5 mg BID, and +1.2 kg for olanzapine 15 mg QD. There were no clinically relevant changes in metabolic parameters; values were generally similar across treatment groups.

Conclusion

Asenapine 2.5 mg BID and 5 mg BID were generally well tolerated in long-term treatment. Weight gain was less for overall asenapine 2.5 mg BID and 5 mg BID than for olanzapine 15 mg QD.

Keywords: asenapine, schizophrenia, long-term, safety, weight, olanzapine

Introduction

Schizophrenia is a serious neuropsychiatric syndrome that is associated with considerable medical morbidity and mortality1 and marked personal, familial, social, and occupational impairment.2 The symptoms of schizophrenia are classified into positive (eg, distortions of thinking and perception), negative (eg, blunted or loss of range of affective and conative functions), cognitive (ie, impairment), disorganization (ie, of thinking and behavior), mood (eg, increased emotional arousal and reactivity), and motor (eg, slowing or increase in motor activity) domains.3 Clinical presentations differ among patients, but schizophrenia is often characterized by a chronic and relapsing course with exacerbations and incomplete remissions and variable degrees of functional and social impairment.3

Although first- and second-generation antipsychotics offer similar efficacy in treating schizophrenia, second-generation agents induce fewer extrapyramidal symptoms (EPS) than haloperidol, a potent first-generation agent.4 However, second-generation antipsychotics are sometimes associated with other serious treatment-related adverse events (AEs), including weight gain, metabolic effects, diabetes, cardiac effects, and prolactin elevation.5 Because second-generation antipsychotics are a heterogeneous class of drugs with different pharmacologic profiles and receptor-binding affinities, their propensity to cause these side effects differs by agent. Consideration of the safety profile of an antipsychotic medication is an important aspect of clinical management in schizophrenia, since long-term treatment is usually necessary to manage symptoms over the course of the illness.

Asenapine (5 mg or 10 mg twice daily [BID] sublin-gually) is a second-generation antipsychotic that is US Food and Drug Administration-approved for the treatment of adults with schizophrenia and for the treatment of acute manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adult and pediatric patients (10–17 years). Asenapine has a unique receptor-binding profile that displays potent multireceptor antagonism for serotonin, dopamine, noradrenaline, and histamine receptors.6 Since asenapine has no affinity for muscarinic receptors, it incurs minimal risk for anticholinergic side effects. The efficacy of asenapine in the treatment of adults with schizophrenia has been demonstrated in two fixed-dose, short-term, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trials.7,8 Maintenance of asenapine efficacy has been demonstrated in a placebo-controlled, double-blind, flexible-dose trial with a randomized withdrawal design.9

We present the results of an extension study that was conducted to evaluate the long-term safety of asenapine 5 mg BID and assess the long-term safety of a lower dose of asenapine (2.5 mg BID) in adult patients with schizophrenia (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01617200). Included patients had completed a 6-week, Phase III, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled acute trial (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT01617187) evaluating the efficacy and safety of asenapine 2.5 mg BID or 5 mg BID in adult patients with schizophrenia; olanzapine was included as an active control. In the acute trial, the difference in change from baseline in Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS)10 total score (primary endpoint) was statistically significant in favor of asenapine 5 mg BID over placebo; there was no statistically significant difference between asenapine 2.5 mg BID and placebo.11

Patients and methods

This extension study was conducted at 39 centers in the US (9), Bulgaria (8), Romania (6), Russian Federation (9), Croatia (3), and Ukraine (4) between March 12, 2013, and March 6, 2015. The study protocol and applicable amendments were approved by independent ethics committees (Table S1), and the trial was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice standards. Written informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Study design

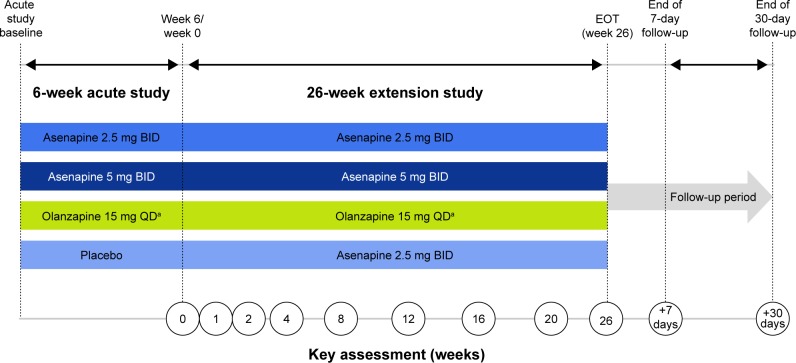

The extension study was a 26-week, Phase IIIB, double-blind, multicenter, double-dummy, fixed-dose study in adult patients (≥18 years of age) who had completed the 6-week acute study; olanzapine was included as the active comparator. A detailed description of the acute lead-in study has been published previously.11 Briefly, the 6-week acute study included male or female patients (≥18 years of age) with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, fourth edition, text revision12 and acute exacerbation at the time of the study. Patients were required to meet clinical criteria: PANSS total score of ≥70, score ≥4 (moderate) on at least two PANSS positive subscale items (delusions, conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, grandiosity, suspiciousness/persecution), and a Clinical Global Impressions – Severity (CGI-S) scale13 score ≥4 (moderately ill). After completing the 6-week double-blind treatment period in the acute trial, patients who had been randomized to asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID, olanzapine 15 mg once daily (QD), or placebo were able to enroll in the extension study. The extension study consisted of a baseline visit (week 6/end of treatment in the acute trial), an extension treatment period of 26 weeks, and 30-day follow-up period (visit on day 7; telephone follow-up on day 30 to determine if serious AEs [SAEs] or pregnancies had occurred) (Figure 1). Day 1 of the extension study overlapped with the last day of the acute trial. The first dose of the study drug in the extension was given on the evening of day 1; patients were contacted by telephone on day 2 to ensure that they understood dosing and to assess for AEs.

Figure 1.

Trial design.

Notes: aThe time of the active olanzapine dose (morning or afternoon/evening) was not disclosed in order to preserve blinding. If the active olanzapine dose was taken in the morning, the olanzapine-matched placebo was taken in the afternoon/evening; if the active olanzapine dose was taken in the afternoon/evening, the olanzapine-matched placebo was taken in the morning. The same number of film-coated tablets was taken in the morning and afternoon/evening.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; EOT, end of treatment; QD, once daily.

Inclusion criteria

Patients who had completed the acute trial and who were judged likely to benefit from continued treatment were included in the extension study. Included patients had no newly diagnosed medical or psychiatric condition that would have excluded them from participation in the acute study. Each patient was required to have a reliable caregiver who agreed to provide support for treatment compliance, outpatient visits, and protocol procedures.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with a primary Axis I diagnosis other than schizophrenia that was predominantly responsible for the current symptoms and functional impairment were excluded from the acute study. Patients were also excluded for any uncontrolled, unstable, or clinically significant medical condition, other than schizophrenia, that could interfere with the conduct of the trial. A clinically significant AE or other finding from the acute trial, including pregnancy, was exclusionary. Patients with a baseline CGI-S score ≥6 (severely psychotic) or patients at risk of self-harm or harm to others based on investigator judgment and Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)14 assessment were excluded. Patients with substance abuse or dependence (within the time period between 6 months before the acute trial and the extension trial baseline) or history of imprisonment, parole, or assaultive behavior (within the time period from 2 years before the acute trial and the extension trial baseline) were excluded. Patients were not allowed to use antipsychotics other than the trial medication; psychotropic medications were prohibited, with the exception of lorazepam (for agitation, anxiety, and insomnia), zolpidem, zaleplon, or zopiclone (for insomnia), and medications to treat EPS (including anticholinergics).

Treatment allocation

In the acute study, patients were randomized to placebo, asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID, or olanzapine 15 mg QD. During the 26-week extension period, patients were assigned to the same treatment regimen as during the acute trial; patients who had been randomized to placebo were assigned to asenapine 2.5 mg BID. Treatment groups are referred to by acute and extension-treatment assignment (ie, placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD); asenapine 2.5 mg BID overall refers to all patients who were treated with asenapine 2.5 mg BID in the extension trial, regardless of their lead-in treatment randomization.

Trial medication comprised fast-dissolving sublingual tablets of asenapine and placebo and film-coated tablets of oral olanzapine and placebo. Patients in the asenapine treatment groups received 2.5 mg BID or 5 mg BID in addition to olanzapine-matched placebo tablets BID; patients in the olanzapine treatment group received 15 mg olanzapine QD and olanzapine-matched placebo QD, along with asenapine-matched sublingual placebo tablets BID.

Trial blinding/masking

An interactive voice–response system was contacted at the extension trial baseline to assign unique patient identification numbers. Asenapine and asenapine-matched placebo tablets were indistinguishable in appearance; olanzapine and olanzapine-matched placebo tablets were identical in appearance. Both were administered in a double-dummy fashion. Patients and investigational staff were unaware of treatment assignment; acute treatment assignments remained blinded during the extension study. If the blind was broken during the trial, patients were not excluded from analyses; of note, the study blind was not broken by any patient during treatment.

Safety outcomes

Safety assessments included AEs and SAEs (monitored at every study visit and coded using the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities [MedDRA], version 17.1), weight and abdominal circumference (weeks 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 26), laboratory tests (weeks 4 and 26), vital signs (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 26), physical examination (week 26), and electrocardiography (ECG; day 1 [baseline]). EPS were evaluated as AEs and by abnormal-movement rating scales: Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale (AIMS),15 Barnes Akathisia Scale (BARS),16 and Simpson Angus Rating Scale (SARS)17 (weeks 1, 2, 4, 12, and 26). Treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and behavior were assessed by the C-SSRS (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20, and 26). Telephone contacts were made weekly between study visits to remind the subject to take the study drug as prescribed, to ask about new or ongoing AEs, and to ask about any change in concomitant medications.

Efficacy outcomes

Because the primary objective of this study was the evaluation of safety, there was no primary efficacy analysis; all efficacy endpoints were considered secondary. Secondary efficacy endpoints of interest in the extension study were based on the primary and secondary endpoints in the acute trial. Efficacy endpoints of interest included PANSS total score change from the acute study baseline to weeks 1, 4, 12, and 26 in the extension-treatment period, PANSS response rate at week 26 (≥30% reduction in PANSS total score from acute study baseline), CGI-S score (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 26), and the rate of CGI – Improvement (CGI-I)13 response (score ≤3) (weeks 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 16, and 26).

Sample size

Sample size was determined by the number of patients who completed the acute trial and continued into the extension trial. All completers who may have benefited from treatment with asenapine or olanzapine were able to participate. This trial was not powered for direct comparison among groups.

Statistical analysis

There was no primary analysis in this trial. Safety outcomes were specified as predefined or exploratory. Safety analyses were based on the all treated set (ATS), which included all randomized patients from the acute study who received at least one dose of extension trial medication. Efficacy assessments were based on the full analysis set, which included all randomized patients from the acute study who received at least one dose of extension trial medication and had baseline and at least one postbaseline PANSS total score measurements. All continuous endpoints were summarized using descriptive statistics. The acute study baseline was used for change from baseline analyses for all treatment groups. The study endpoint for safety was defined as the last nonmissing assessment after the extension trial baseline and on or before the last dose date plus 7 days.

Change from acute study baseline for continuous safety and efficacy parameters was analyzed at each study visit using analysis of covariance models to assess the point estimate and 95% confidence interval (CI). Models included fixed effects for treatment and investigative site and baseline value as a covariate. For efficacy parameters, both observed case (OC) and last observation carried forward (LOCF) approaches were used. All efficacy analyses were considered secondary efficacy analyses, and no efficacy hypothesis was tested.

AEs were designated treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) if the event was newly reported or had worsened in severity after acute study baseline; the end of the period for determination of TEAEs was the last dose date plus 7 days for nonserious AEs and the last dose date plus 30 days for SAEs. Treatment-related TEAEs were TEAEs that were determined by the investigator to have a possible or probable relationship to study treatment. EPS assessed by movement disorder rating scales were evaluated by mean change from acute study baseline (the most recent nonmissing assessment before the first dose of acute study drug) and treatment-emergent symptoms (AIMS item 8 [abnormal movements] score ≥2, BARS global score ≥2, and SARS total score >3).

The prespecified key safety endpoint was change in weight from the acute study baseline to week 26. Weight change was analyzed using a mixed-model repeated-measure approach in the ATS population, with change from acute study baseline score at each visit as the dependent variable, adjusted for acute study baseline weight as a covariate; treatment, investigation site, visit, and treatment by visit interaction as fixed-effect factors; and a random subject effect. Comparisons between the asenapine groups and the olanzapine group were presented as least squares (LS) mean difference and 95% CI; no adjustments were made for multiple comparisons, and no P-values were determined.

Exploratory safety data were analyzed using an a priori multi-tiered approach. Tier 1 and Tier 2 TEAEs were assessed via point estimates and 95% CIs of the adjusted population; Tier 2 laboratory parameters were assessed via point estimates of the LS mean and associated 95% CI. Point estimates by treatment group only were provided for Tier 3 safety parameters. Tier 1 events comprised weight gain ≥7%, AE standardized MedDRA query (narrow) EPS, and preferred terms for AEs of akathisia, combined somnolence/hypersomnia/sedation, dizziness, insomnia, and combined oral hypoesthesia/dysgeusia. Combined endpoints required that a patient had at least one of the included preferred AE terms. Tier 2 safety endpoints required that four or more patients in any treatment group exhibited the event; Tier 2 laboratory endpoints were change from acute study baseline in fasting glucose, fasting triglycerides, fasting cholesterol, prolactin, fasting insulin, and glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c). All other events were classified as Tier 3.

Results

Patient disposition and demographics

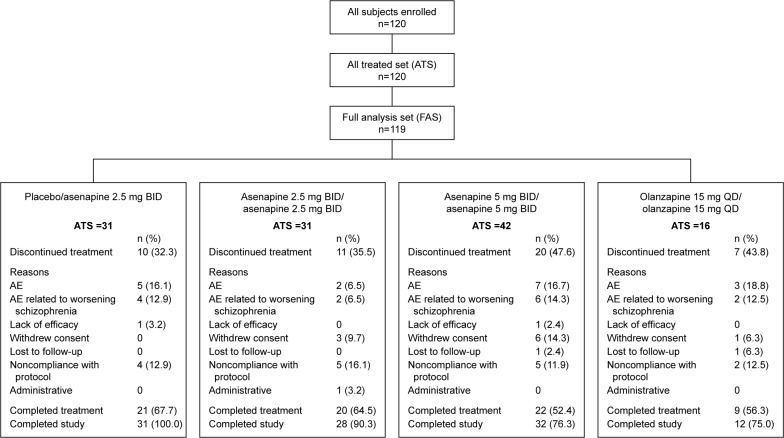

A total of 120 patients continued from the acute study to the extension trial, and 120 patients received at least one dose of extension trial medication (Figure 2). Overall, 72 (60%) patients in the ATS completed treatment. The most common reasons for discontinuation were AEs, most of which were related to worsening schizophrenia disorder and noncompliance with protocol.

Figure 2.

Patient disposition and reasons for discontinuation.

Note: One subject in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group did not have a postbaseline PANSS total score measurement and was therefore not included in the FAS.

Abbreviations: AE, adverse event; ATS, all treated set; BID, twice daily; FAS, full analysis set; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QD, once daily.

Baseline demographic characteristics were recorded during the screening period of the acute trial (Table 1); treatment groups in the ATS were generally well matched. The overall mean patient age was 39.6 years; 95% of patients had a diagnosis of schizophrenia paranoid type. Slight differences were noted among some groups in the duration of schizophrenia, the percentage of white patients, weight, and body mass index.

Table 1.

Patient baseline demographic characteristics (ATS, acute study screening period)

| Characteristics | PBO/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 | ASN 2.5 mg BID/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 | ASN 5 mg BID/ASN 5 mg BID, n=42 | OLZ 15 mg QD/OLZ 15 mg QD, n=16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex, n (%) | ||||

| Male | 18 (58.1) | 18 (58.1) | 25 (59.5) | 10 (62.5) |

| Female | 13 (41.9) | 13 (41.9) | 17 (40.5) | 6 (37.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||

| Black | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (12.5) |

| White | 29 (93.5) | 29 (93.5) | 36 (85.7) | 14 (87.5) |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 39.5 (10.1) | 41.1 (9.8) | 39.5 (10.0) | 37.4 (12.5) |

| Weight (kg), mean (SD) | 76.0 (16.1) | 79.7 (16.1) | 75.1 (18.9) | 79.4 (16.5) |

| BMI (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 26.9 (5.2) | 27.3 (4.7) | 25.4 (5.0) | 26.7 (5.0) |

| Abdominal girth (cm), mean (SD) | 90.4 (16.1) | 91.7 (16.7) | 88.9 (14.2) | 90.5 (13.5) |

| Current schizophrenia diagnosis, n (%) | ||||

| Paranoid type | 29 (93.5) | 31 (100.0) | 38 (90.5) | 16 (100.0) |

| Disorganized type | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Undifferentiated type | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Duration (years), mean (SD) | 12.1 (9.3) | 10.6 (9.1) | 13.4 (10.0) | 10.1 (7.3) |

| Episodes within the past 12 months (including current), n (%) | ||||

| None | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| 1 | 7 (22.6) | 16 (51.6) | 22 (52.4) | 3 (18.8) |

| 2–3 | 22 (71.0) | 14 (45.2) | 16 (38.1) | 10 (62.5) |

| 4 or more | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (9.5) | 3 (18.8) |

| Duration of the current episode (weeks), n (%)a | ||||

| ≤2 | 12 (38.7) | 10 (32.3) | 15 (35.7) | 6 (37.5) |

| >2–≤4 | 11 (35.5) | 11 (35.5) | 18 (42.9) | 4 (25.0) |

| >4–≤6 | 2 (6.5) | 7 (22.6) | 6 (14.3) | 5 (31.3) |

| >6–≤8 | 6 (19.4) | 3 (9.7) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) |

Note:

No current episode was longer than 8 weeks.

Abbreviations: ASN, asenapine; ATS, all-treated set; BID, twice daily; BMI, body mass index; OLZ, olanzapine; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; SD, standard deviation.

Safety

Extent of exposure

The mean (standard deviation) duration of extension-study treatment was 150.4 (56.8) days in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, 145.6 (57.8) days in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, 134.4 (65.4) days in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group, and 123.1 (78.4) days in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group.

Safety overview

No deaths occurred during the extension period. An SAE was reported in five (16.1%) patients in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group (schizophrenia, paranoid type [two], schizophrenia [one], noncardiac chest pain [one], pneumonia [one], psychomotor hyperactivity [one]); in two (6.5%) patients in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group (schizophrenia [two]); in six (14.3%) patients in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group (schizophrenia [five], suicidal ideation [one]); and in two (12.5%) patients in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group (schizophrenia [one], suicide attempt [one]).

A summary of AEs and a listing of TEAEs that occurred in ≥5% of patients are presented in Table 2. No SAEs led to study discontinuation in any asenapine-treated group. The most commonly reported AEs leading to discontinuation were classified as psychiatric disorders; all AEs leading to discontinuation were reported by only one patient per treatment group, with the exceptions of worsening schizophrenia (asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, five [11.9%] patients) and worsening schizophrenia, paranoid type (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, two [6.5%] patients). The majority of TEAEs were mild or moderate in intensity; the only TEAEs that were considered severe in intensity were reported in two (12.5%) patients in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group (suicide attempt [one] and pulmonary tuberculosis [one]) and one (2.4%) patient in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group (schizophrenia). As assessed by the investigator, the only treatment-related TEAEs that occurred in three or more patients were schizophrenia (asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID [three patients]), and somnolence and weight increased (asenapine 2.5 mg BID overall, three patients each AE).

Table 2.

Summary of AEs and common TEAEs (ATS)

| Summary of AEs | PBO/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 n (%) |

ASN 2.5 mg BID/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 n (%) |

ASN 5 mg BID/ASN 5 mg BID, n=42 n (%) | OLZ 15 mg QD/OLZ 15 mg QD, n=16 n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with | ||||

| ≥1 SAEs | 5 (16.1) | 2 (6.5) | 6 (14.3) | 2 (12.5) |

| ≥1 AEs | 23 (74.2) | 13 (41.9) | 18 (42.9) | 6 (37.5) |

| ≥1 TEAEs | 22 (71.0) | 12 (38.7) | 16 (38.1) | 4 (25.0) |

| ≥1 AEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 5 (16.1) | 1 (3.2) | 7 (16.7) | 3 (18.8) |

| ≥1 treatment-related TEAEs | 11 (35.5) | 4 (12.9) | 7 (16.7) | 2 (12.5) |

| ≥1 treatment-related TEAEs leading to treatment discontinuation | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) |

| Patients with TEAEs (≥5% in any treatment group) | ||||

| Psychiatric disorder | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (11.9) | 1 (6.3) |

| Insomnia | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Schizophrenia, paranoid type | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Suicide attempt | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Nervous system disorders | ||||

| Somnolence | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Akathisia | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Dyskinesia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Infections and infestations | ||||

| Nasopharyngitis | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (6.3) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Urinary tract infection | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Investigations | ||||

| Weight increased | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood creatine phosphokinase increased | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Blood insulin increased | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Injury, poisoning, and procedural complications | ||||

| Accidental overdose | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | 3 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Respiratory, thoracic, and mediastinal disorders | ||||

| Bronchitis, chronic | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | ||||

| Dermatitis | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| Vascular disorders | ||||

| Hypertension | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

Notes: AEs were coded using MedDRA version 17.1. An AE was any unfavorable and unintended change in the structure, function, or chemistry of the body temporally associated with any use of a study drug, whether or not it was considered related to use; a TEAE was a newly reported event after acute study baseline, or an event reported to have worsened in severity since acute study baseline (period for determination of TEAEs was the last dose date +7 days for nonserious AEs and the last dose date +30 days for SAEs).

Abbreviations: AEs, adverse events; ASN, asenapine; ATS, all-treated set; BID, twice daily; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; OLZ, olanzapine; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; SAEs, serious AEs; TEAEs, treatment-emergent AEs.

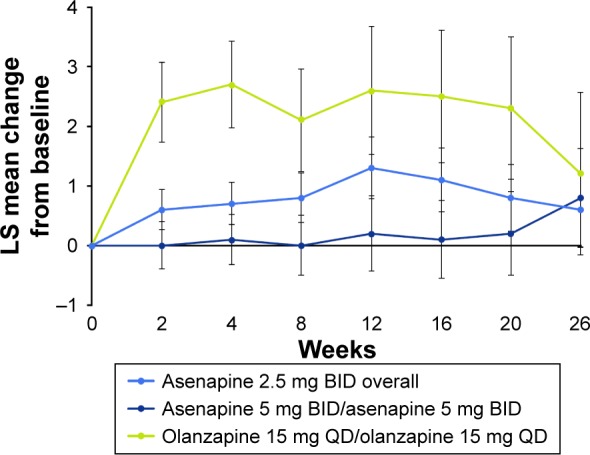

Key safety endpoint

During the 26-week extension study, LS mean change in weight from acute study baseline to week 26 was lower for patients treated with either asenapine 2.5 mg BID or 5 mg BID than for patients treated with olanzapine 15 mg QD (Figure 3). Using mixed-model repeated-measure analysis, the LS mean (standard error) change in body weight from acute study baseline to week 26 was +0.6 (0.63) kg for overall asenapine 2.5 mg BID, +0.8 (0.82) kg for asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, and +1.2 (1.36) kg for olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD. The LS mean difference with associated 95% CI for asenapine 2.5 mg BID overall versus olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD was −0.6 kg (−3.6 to 2.4); the LS mean difference for asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID versus olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD was −0.4 kg (−3.6 to 2.7).

Figure 3.

LS mean change in weight from acute study baseline to week 26 (MMRM, ATS).

Note: Baseline was the last nonmissing assessment before the first dose of acute study medication.

Abbreviations: ATS, all treated set; BID, twice daily; LS, least squares; MMRM, mixed-effect model for repeated measures; QD, once daily.

Prespecified TEAEs of interest

Prespecified TEAEs are presented in Table 3. In general, the incidence of Tier 1 TEAEs was greater in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group; no Tier 1 SAEs/AEs resulted in treatment discontinuation in any group. Weight gain ≥7% had overlapping 95% CIs for all treatment groups; incidence was greatest in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group, followed by the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, and asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID groups. When Tier 2 TEAEs were adjusted for pooled investigation site, the estimated proportion of patients with schizophrenia was greater in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group than in the other treatment groups; the estimated adjusted proportion of patients with weight increased was greater in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID treatment group than in the other treatments groups. There were no notable findings with regard to closely monitored events, SAEs, suicidality, vital signs, ECG, or clinical laboratory results.

Table 3.

Patients with prespecified TEAEs of special interest (ATS)

| PBO/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 n (%) |

ASN 2.5 mg BID/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 n (%) | ASN 5 mg BID/ASN 5 mg BID, n=42 n (%) |

OLZ 15 mg QD/OLZ 15 mg QD, n=16 n (%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 1 | ||||

| ≥1 Tier 1 TEAEs | 7 (22.6) | 4 (12.9) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (6.3) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.21 (0.081, 0.342) | 0.14 (0.025, 0.258) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.139) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.185) |

| EPS SMQ (narrow) | 4 (12.9) | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (6.3) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.12 (0.018, 0.224) | 0.03 (0.000, 0.087) | – | 0.07 (0.000, 0.185) |

| Insomnia | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 2 (4.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.163) | 0.06 (0.000, 0.136) | 0.05 (0, 0.106) | – |

| Somnolence, sedation, or hypersomnia | 2 (6.5) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.05 (0.000, 0.123) | 0.05 (0.000, 0.13) | 0.02 (0.000, 0.060) | – |

| Akathisia | 2 (6.5) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.150) | – | – | – |

| Dizziness | 1 (3.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.03 (0.000, 0.073) | – | – | – |

| Hypoesthesia oral or dysgeusia | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | – | – | – | – |

| Weight gain ≥7% | 4 (13.3) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (12.2) | 4 (26.7) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.11 (0.019, 0.205) | 0.06 (0.000, 0.138) | 0.12 (0.023, 0.223) | 0.26 (0.081, 0.449) |

| Tier 2 | ||||

| ≥1 Tier 2 TEAEs | 5 (16.1) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (14.3) | 1 (6.3) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.14 (0.041, 0.232) | 0.09 (0.000, 0.179) | 0.13 (0.039, 0.230) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.185) |

| Schizophrenia | 2 (6.5) | 2 (6.5) | 5 (11.9) | 1 (6.3) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.06 (0.000, 0.123) | 0.06 (0.000, 0.134) | 0.11 (0.025, 0.191) | 0.07 (0.000, 0.185) |

| Weight increased | 3 (9.7) | 1 (3.2) | 1 (2.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| P* (95% CI) | 0.08 (0.000, 0.164) | 0.03 (0.000, 0.087) | 0.03 (0.000, 0.073) | – |

| Tier 3 | ||||

| ≥1 Tier 3 TEAEs | 16 (51.6) | 6 (19.4) | 12 (28.6) | 3 (18.8) |

Notes: P*, point estimate of adjusted proportion; P* and 95% CIs calculated using weighted formulae that accounted for pooled investigative site.

Abbreviations: ATS, all-treated set; ASN, asenapine; BID, twice daily; CI, confidence interval; EPS, extrapyramidal symptom; MedDRA, Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities; OLZ, olanzapine; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; SMQ, standardized MedDRA query; TEAEs, treatment-emergent AEs.

Clinical laboratory and electrocardiographic findings

LS mean changes from acute study baseline in Tier 2 clinical laboratory values are presented in Table 4. LS mean changes (95% CI) suggested differentiation (decreases) from the acute study baseline to the extension trial study endpoint for prolactin levels in all treatment groups. Differentiation (increase) from the acute study baseline to study endpoint for HbA1c levels was suggested for the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, but not for the other treatment groups. No differentiation from the acute study baseline to study endpoint was suggested for total fasting cholesterol, fasting insulin, fasting triglycerides, or fasting glucose for any treatment group, as evidenced by 95% CIs that included values of zero.

Table 4.

Summary of Tier 2 laboratory values: LS mean changes from acute study baseline to endpoint (ATS)

| Parameters | PBO/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 | ASN 2.5 mg BID/ASN 2.5 mg BID, n=31 | ASN 5 mg BID/ASN 5 mg BID, n=42 | OLZ 15 mg QD/OLZ 15 mg QD, n=16 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical laboratory values, LS mean change (SE) | ||||

| Total cholesterol (fasting), mg/dL | −2.3 (6.23) | 0.2 (6.28) | −3.6 (5.79) | −12.2 (9.37) |

| 95% CI of LSM | −14.6, 10.0 | −12.2, 12.6 | −15.0, 7.9 | −30.7, 6.3 |

| Prolactin, ng/mL | −13.7 (3.66) | −14.4 (3.69) | −12.4 (3.10) | −14.6 (5.26) |

| 95% CI of LSM | −20.9, −6.5 | −21.6, −7.1 | −18.5, −6.2 | −25.0, −4.2 |

| Insulin (fasting), μIU/mL | −1.6 (4.10) | 2.1 (4.05) | −1.0 (3.98) | −2.5 (6.31) |

| 95% CI of LSM | −9.7, 6.5 | −5.9, 10.1 | −8.9, 6.8 | −15.0, 9.9 |

| Triglycerides (fasting), mg/dL | 1.9 (13.43) | −28.7 (13.81) | −15.8 (12.21) | −2.5 (18.84) |

| 95% CI of LSM | −24.6, 28.5 | −56.0, −1.4 | −40.0, 8.3 | −39.7, 34.7 |

| Glucose (fasting), mg/dL | 0.8 (2.73) | 1.8 (2.74) | 5.8 (2.47) | 1.5 (4.09) |

| 95% CI of LSM | −4.6, 6.2 | −3.6, 7.3 | 0.9, 10.7 | −6.6, 9.6 |

| HbA1c, % | 0.2 (0.06) | 0.1 (0.06) | 0.1 (0.05) | 0.1 (0.08) |

| 95% CI of LSM | 0.1, 0.3 | −0.1, 0.2 | −0.0, 0.2 | −0.0, 0.3 |

Notes: LS mean changes are point estimates. Baseline was the last nonmissing assessment before the first dose of acute trial medication; endpoint was the last nonmissing postbaseline assessment on or prior to the last dose date +7 days.

Abbreviations: ASN, asenapine; ATS, all-treated set; BID, twice daily; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; LS, least squares; LSM, LS mean; OLZ, olanzapine; PBO, placebo; QD, once daily; SE, standard error.

No subjects had elevated liver enzymes that met the criteria for potential drug-induced liver injury; any subject with any level of alanine aminotransferase or aspartate aminotransferase elevation also had total bilirubin that was less than or equal to two times the upper limit of normal. There were no clinically relevant mean changes in biochemistry parameters, and values were generally similar across treatment groups, with the exception of creatine kinase (CK). Mean (standard deviation) increases in CK values were observed in all treatment groups (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 54.2 [214.4] U/L; asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 103.7 [501.2] U/L; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, 23.9 [149.9] U/L; olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, 47.7 [62.3] U/L). Large standard deviations suggest large variations in CK levels over time in the asenapine treatment groups. Mean changes in pulse rate and blood pressure were not suggestive of a treatment-related effect.

Increase in abdominal circumference was higher in the olanzapine treatment group than in the asenapine treatment groups (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 1.67 [3.8] cm; asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, −0.51 [6.0] cm; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, 0.11 [5.6] cm; olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, 2.12 [6.4] cm). The percentage of patients who met the criteria for predefined limits of change for laboratory values was generally small and comparable among treatment groups; no trends were noted. There were no TEAEs reported for ECG abnormalities, nor were there findings of Fridericia-derived QTc interval prolongation >500 ms.

Extrapyramidal symptoms

On the AIMS, mean change from acute study baseline was minimal in all groups (0.0 to −0.2); only one patient (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group) had an AIMS item 8 score ≥2. On the BARS, mean change from acute study baseline was also minimal in all groups (0.0 to –0.2); one patient each in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID and the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID groups and no patients in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD groups had treatment-emergent akathisia (BARS score ≥2). On the SARS, mean change from acute study baseline was again minimal in all groups (−0.3 to −1.1); three patients in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, two patients in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, no patients in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group, and one patient in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group had treatment-emergent parkinsonism (SARS score >3). The incidence of EPS-related TEAEs was higher in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group (12.9%) than in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID (3.2%), asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID (0), and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD (6.3%) groups.

Suicidality

During the extension trial treatment phase, suicidal ideation assessed by the C-SSRS was reported for one (3.2%) patient in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group; the type of ideation was in the least severe category (wish to be dead). Suicidal behavior was also reported for one (6.3%) patient in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group; the type of behavior was an actual attempt, which was classified as a TEAE that was considered related to treatment and resulted in discontinuation from the study. Neither patient had reported suicidal ideation or behavior in the 2 months or 6 months, respectively, prior to enrolling in the acute trial. Additionally, neither patient had a lifetime history of suicidal ideation or behavior. No other patients had a TEAE of suicide attempt.

Efficacy

Efficacy is presented using OC analysis based on the full analysis set; in general, findings observed using the LOCF approach were similar to those observed using the OC approach. LS mean (95% CI) PANSS total score decreased from the acute study baseline to week 26 in the extension trial in all four treatment groups (Figure S1A; placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, −30.2 [−35.24 to −25.19]; asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, −28.5 [−33.9 to −23.14]; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, −32.7 [−37.8 to −27.68]; olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, −36.4 [−44.6 to −28.14]). The percentage of PANSS responders (≥30% reduction in PANSS total score from acute study baseline) at the extension trial baseline in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD groups, respectively, was 32.3%, 29.0%, 45.2%, and 46.7%; the percentage of PANSS responders at week 26 was 66.7%, 47.4%, 68.2%, and 62.5%, respectively. Using the LOCF approach, PANSS responder rates were generally lower than those seen using the OC approach (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 48.4%; asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 51.6%; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, 47.6%; and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, 46.7%).

On the CGI-S, small LS mean (95% CI) decreases from the acute trial baseline to week 26 in the extension study were seen in all treatment groups (Figure S1B; placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, −1.9 [−2.27 to −1.47]; asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, −1.4 [−1.83 to −0.96]; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, −1.5 [−1.9 to −1.07]; and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, −1.8 [−2.47 to −1.16]). Patients were considered CGI-I responders if the change from acute study baseline at each study visit and at week 26 was classified as minimally improved, much improved, or very much improved (CGI-I score ≤3). At the extension trial baseline, CGI-I response rates from the acute trial were high in all active treatment groups (asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 90.3%; asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, 92.9%; olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD, 100%) and lower in the placebo group (placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, 80.6%). CGI-I response rates fluctuated during the extension trial; at week 26, the response rate was 85.7% in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, 94.7% in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group, 86.4% in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group, and 87.5% in the olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD group. Using the LOCF approach, response rates at week 26 were 64.5%, 90.3%, 69.0%, and 80.0% in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD groups, respectively.

Discussion

The primary objective of this extension study was to evaluate the long-term safety of asenapine 2.5 mg BID and 5 mg BID; weight change from the acute study baseline to week 26 for asenapine-treated patients relative to patients treated with the active control olanzapine was the prespecified key safety endpoint. Both asenapine 2.5 mg BID and 5 mg BID were generally tolerated well in long-term treatment.

The majority of SAEs were related to worsening of psychiatric disorders. TEAEs were similar to those previously reported in both short- and longer-term trials9,11,18; the most commonly reported AE leading to treatment discontinuation in this study was worsening of schizophrenia. The incidence of TEAEs was higher in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group relative to the other treatment groups, which is understandable given the asenapine-naïve status of patients in this group. As determined by the investigator, treatment-related TEAEs that occurred at an incidence of at least 5% in any treatment group and more often in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group were somnolence, akathisia, and weight increase; the incidence of treatment-related schizophrenia was higher in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID group than in the other treatment groups. Treatment-related TEAEs of weight increase, somnolence, and akathisia were also the most commonly reported TEAEs in previous long-term studies of asenapine in the treatment of schizophrenia, occurring at rates similar to those seen this study (3%–17% of patients).9,18 The majority of TEAEs were mild/moderate in intensity. On the prespecified key safety endpoint, LS mean change in weight from the acute trial baseline to week 26, patients in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID or 5 mg BID groups gained less weight than patients in the olanzapine 15 mg QD group, although this difference was not statistically significant. Previous post hoc analyses and meta-analyses summarizing the effects of asenapine on weight gain in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar I disorder have shown that asenapine is associated with a lower incidence of weight gain relative to olanzapine,19,20 suggesting that the present study may have been underpowered to detect a statistical difference.

While sedentary lifestyle, smoking, and poor diet contribute to high rates of cardiovascular disease in patients with schizophrenia,21 metabolic syndrome is also an undeniable source of cardiovascular risk for these patients. Metabolic syndrome, which comprises abnormalities in glucose metabolism, lipid metabolism, obesity, and blood pressure, is generally viewed as the link between schizophrenia and cardiovascular disease.21 The prevalence of metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia is about 40%, according to the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE); the prevalence is higher in women (54.2%) than in men (36.6%).22 Because the metabolic effects of antipsychotic medications are different,23,24 knowing the metabolic profile of an individual agent is an important component of good clinical management.

Toward this end, the analytic strategies used in this extension trial helped to specifically characterize important metabolic events associated with asenapine. The inclusion of olanzapine in the study allowed for comparison of asenapine with another approved second-generation antipsychotic. The prespecified key weight safety endpoint, as well as the use of a tiered AE strategy, allowed for particular attention to be paid to metabolic and endocrine laboratory endpoints of special interest. Of note, clinically significant weight gain and mean change from acute study baseline to endpoint in fasting glucose, fasting triglycerides, fasting cholesterol, fasting insulin, and HbA1c, which are factors that increase the risk of metabolic syndrome, were classified as Tier 2 laboratory endpoints.

TEAEs related to cardiovascular and metabolic risk occurred at relatively low rates among asenapine patients. From the acute study baseline to week 26 of the extension study, asenapine-treated patients had less weight gain than olanzapine-treated patients. Although the between-group difference in mean weight increase may not have been large enough to be considered clinically relevant, it is noteworthy that asenapine patients experienced less increase in abdominal girth and a lower incidence of clinically significant weight gain than olanzapine patients. Weight gain and intra-abdominal obesity, which is operationalized as increased waist circumference, are key factors in the development of metabolic syndrome.21 There were no clinically relevant mean changes in metabolic parameters from the acute trial baseline to study endpoint for asenapine-treated patients. This was in accordance with previous post hoc analyses that showed asenapine to be favorable to olanzapine in terms of changes in triglycerides and cholesterol levels.19 No AEs were reported for ECG abnormalities, and no clinically significant QTc prolongation was observed.

Other TEAEs that were of particular interest for asenapine were evaluated as Tier 1 safety events (ie, somnolence, sedation, and hypersomnia combined, dizziness, insomnia, oral hypoesthesia combined with dysgeusia, akathisia, EPS). As observed in the case of general TEAEs, patients in the placebo/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group had the highest incidence of Tier 1 TEAEs (22.6%), followed by patients in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID group (12.9%); patients in the asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD groups had lower and comparable Tier 1 TEAE incidence (7.1% and 6.3%, respectively). No Tier 1 AE and no SAE led to treatment discontinuation in the asenapine-treated groups. Decreases were noted in mean prolactin levels in all treatment groups, suggesting that treatment was not associated with symptoms of hyperprolactinemia, which includes gynecomastia, sexual dysfunction, oligomenorrhea, and amenorrhea.25

For this extension safety study, efficacy measures were collected, but there was no primary efficacy analysis; all efficacy endpoints were considered secondary. Change from the acute trial baseline was summarized, but no efficacy hypotheses were tested, and the trial was not powered for direct comparison. As such, changes in psychiatric symptoms and disease severity can be described, but no efficacy conclusions can be made. Mean PANSS total score decreased from the acute trial baseline to the extension trial study endpoint in all four treatment groups, suggesting symptomatic improvement in all treatment groups. The decrease in score was similar in the asenapine 2.5 mg BID/asenapine 2.5 mg BID, asenapine 5 mg BID/asenapine 5 mg BID, and olanzapine 15 mg QD/olanzapine 15 mg QD groups, and slightly less in the asenapine group that was randomized to placebo in the acute lead-in study. Modest improvement in disease severity was suggested by small decreases in CGI-S score from the acute study baseline at all time points in each treatment group. For patients who were switched from placebo in the acute study to asenapine 2.5 mg BID in the extension, symptomatic improvement was suggested by decreases in PANSS total score and CGI-S score. These data are in accordance with previously published work and suggest that asenapine is efficacious in both the long-term treatment and prevention of relapse in patients with schizophrenia.9,18,26

This study further supports the safety and efficacy of asenapine in the treatment of schizophrenia, which has been shown in previous randomized, double-blind, placebo- and active-controlled trials.7–9,11,18,26 There were relatively few SAEs and TEAEs, and most events were considered mild or moderate in severity, suggesting that asenapine was well tolerated. When taken together with previous post hoc and meta-analyses,19,20 asenapine has favorable effects on weight gain and metabolic function relative to olanzapine, which could be of clinical interest in patient populations in which metabolic function is a concern. Decreases in the PANSS total score and CGI-S score occurred early and were maintained throughout the course of the study, indicating that asenapine is a viable option in maintenance treatment of schizophrenia. Asenapine is the only commercially available antipsychotic approved as a sublingual formulation; additionally, it does not require dose titration,27 which may simplify treatment, especially in patients in which administration of medication must be monitored.

Strengths of this study included the double-blind treatment design, an extended treatment duration, inclusion of an active comparator, and long-term monitoring of TEAEs of special interest to asenapine. Limitations of the study included the lack of a placebo-control group and statistical power that precluded the ability to detect between-treatment group differences. Additionally, there was a relatively low number of patients in the olanzapine treatment group relative to the asenapine treatment groups, and stringent inclusion and exclusion criteria may limit the generalizability of these findings to more general schizophrenia populations. The lack of inferential statistics limits the ability to evaluate these results, and no efficacy conclusions can be made.

Conclusion

In this long-term extension study, 26 weeks of treatment with asenapine 2.5 mg BID and 5 mg BID was generally safe and well tolerated in adults with schizophrenia. No dose-dependent relationships with asenapine treatment were apparent for the predefined TEAEs of special interest. Treatment with asenapine was associated with lower weight gain and lower rates of clinically significant weight gain than treatment with olanzapine.

Supplementary materials

LS mean change in PANSS total score (A) and CGI-S score (B) from acute study baseline to week 26 (FAS).

Notes: Baseline was the last nonmissing assessment before the first dose of acute study medication. Analysis based on observed-case model.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – Severity; FAS, full analysis set; LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QD, once daily.

Table S1.

List of independent ethics committees that approved the study

| Site number | Country | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 2,001 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,002 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,006 | US | University of California San Diego Human Research Protection Program |

| 2,007 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,008 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,009 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,010 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,011 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,012 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,013 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,015 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,018 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,022 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,023 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,025 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,026 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,027 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,030 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,101 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,102 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,104 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,104 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,107 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,108 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,109 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,111 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,127 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,129 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,130 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,131 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,133 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,134 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,153 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,154 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,157 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,200 | Russia | Ethical Council at State Budget Healthcare Institution: Samara Psychiatric Hospital |

| 2,201 | Russia | Ethics Committee of State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education: Yaroslavl State Medical Academy of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,202 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,204 | Russia | Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee on Ethical Review for Clinical Studies: Universimed |

| 2,206 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,209 | Russia | LEC of Mental Health Research Institute |

| 2,210 | Russia | Local Ethics Committee of State Public Healthcare Institution of Moscow Region: Central Clinical Mental Hospital |

| 2,211 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,213 | Russia | Local Ethics Committee of SBHI of Sverdlovsk Region: Sverdlovsk Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital |

| 2,226 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at Territorial Medical Association of Psychiatry in Kiev |

| 2,228 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CI LRCPH |

| 2,229 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CHI Kharkiv Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital 3 |

| 2,231 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CI OI Yushchenko Academy, Vinnytsya Regional Psychoneurological Hospital |

Note:

The National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicine is no longer in place and has since been replaced by the National Bioethics Committee for Medicine and Medical Devices.

Abbreviation: IRB, institutional review board.

Acknowledgments

The study was designed by Merck. This study was supported by funding from Forest Laboratories LLC, an Allergan affiliate. Writing assistance and editorial support for this manuscript were provided by Carol Brown, MS, of Prescott Medical Communications Group, Chicago, Illinois, a contractor of Allergan.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors had full access to the data after study completion and are responsible for the work described in this paper. S Durgam, M Mathews, and X Wu were involved with the conduct of the study, as well as interpretation of the data. R Landbloom and M Mackle were involved with the study design, protocol development, data analysis, and interpretation of the data. H Nasrallah contributed as a clinical expert for analysis and interpretation of data. All authors provided final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and revising the paper and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

S Durgam and X Wu acknowledge a potential conflict of interest as employees of Allergan. RP Landbloom and M Mackle acknowledge a potential conflict of interest as employees of Merck. At the time of the study, M Mathews was employed by Forest Research Institute (now Allergan). HA Nasrallah has been a consultant for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Boehringer Ingelheim, Grünenthal USA, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Merck Sharp and Dohme, Novartis, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, Roche/Genentech, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Vanda Pharmaceuticals; he has served on speakers’ bureaus for Acadia, Alkermes, Allergan, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, Merck Sharpe and Dohme, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, and Vanda; and he has received grant/research support from Forest Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceutical, and Roche/Genentech. The authors report no other conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Goff DC, Cather C, Evins AE, et al. Medical morbidity and mortality in schizophrenia: guidelines for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(2):183–194. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmer BA, Pankratz V, Bostwick J. The lifetime risk of suicide in schizophrenia: a reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(3):247–253. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.3.247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tandon R, Nasrallah HA, Keshavan MS. Schizophrenia, “just the facts” 4: clinical features and conceptualization. Schizophr Res. 2009;110(1–3):1–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leucht S, Corves C, Arbter D, Engel RR, Li C, Davis JM. Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis. Lancet. 2009;373(9657):31–41. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farah A. Atypicality of atypical antipsychotics. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;7(6):268–274. doi: 10.4088/pcc.v07n0602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shahid M, Walker GB, Zorn SH, Wong EH. Asenapine: a novel psychopharmacologic agent with a unique human receptor signature. J Psychopharmacol. 2009;23(1):65–73. doi: 10.1177/0269881107082944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kane JM, Cohen M, Zhao J, Alphs L, Panagides J. Efficacy and safety of asenapine in a placebo- and haloperidol-controlled trial in patients with acute exacerbation of schizophrenia. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2010;30(2):106–115. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181d35d6b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potkin SG, Cohen M, Panagides J. Efficacy and tolerability of asenapine in acute schizophrenia: a placebo- and risperidone-controlled trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(10):1492–1500. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v68n1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kane JM, Mackle M, Snow-Adami L, Zhao J, Szegedi A, Panagides J. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of asenapine for the prevention of relapse of schizophrenia after long-term treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(3):349–355. doi: 10.4088/JCP.10m06306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13(2):261–276. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Landbloom R, Mackle M, Wu X, et al. Asenapine for the treatment of adults with an acute exacerbation of schizophrenia: results from a randomized, double-blind, fixed-dose, placebo-controlled trial with olanzapine as an active control. CNS Spectr. 2016 Nov 8; doi: 10.1017/S1092852916000377. Epub. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington: APA; 2000. Text revision. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville (MD): US Department of Heath; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Posner K, Brown GK, Stanley B, et al. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale: initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. Am J Psychiatry. 2011;168(12):1266–1277. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guy W. ECDEU Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Rockville (MD): US Department of Heath; 1976. The Abnormal Movement Scale; pp. 218–222. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barnes TR. A rating scale for drug-induced akathisia. Br J Psychiatry. 1989;154:672–676. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.5.672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Simpson GM, Angus JW. A rating scale for extrapyramidal side effects. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1970;212:11–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1970.tb02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schoemaker J, Naber D, Vrijland P, Panagides J, Emsley R. Long-term assessment of asenapine vs. olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2010;43(4):138–146. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1248313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kemp DE, Zhao J, Cazorla P, et al. Weight change and metabolic effects of asenapine in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2014;75(3):238–245. doi: 10.4088/JCP.12m08271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orr C, Deshpande S, Sawh S, Jones PM, Vasudev K. Asenapine for the treatment of psychotic disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2017;62(2):123–137. doi: 10.1177/0706743716661324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Riordan HJ, Antonini P, Murphy MF. Atypical antipsychotics and metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: risk factors, monitoring, and healthcare implications. Am Health Drug Benefits. 2011;4(5):292–302. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McEvoy JP, Meyer JM, Goff DC, et al. Prevalence of the metabolic syndrome in patients with schizophrenia: baseline results from the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE) schizophrenia trial and comparison with national estimates from NHANES III. Schizophr Res. 2005;80(1):19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Meyer JM, Davis VG, Goff DC, et al. Change in metabolic syndrome parameters with antipsychotic treatment in the CATIE schizophrenia trial: prospective data from phase 1. Schizophr Res. 2008;101(1–3):273–286. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2007.12.487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Newcomer JW. Metabolic considerations in the use of antipsychotic medications: a review of recent evidence. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68(Suppl 1):20–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Henderson DC, Doraiswamy PM. Prolactin-related and metabolic adverse effects of atypical antipsychotic agents. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(Suppl 1):32–44. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schoemaker J, Stet L, Vrijland P, Naber D, Panagides J, Emsley R. Long-term efficacy and safety of asenapine or olanzapine in patients with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder: an extension study. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2012;45(5):196–203. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1301310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Citrome L. Asenapine review, part II: clinical efficacy, safety and tolerability. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2014;13(6):803–830. doi: 10.1517/14740338.2014.908183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

LS mean change in PANSS total score (A) and CGI-S score (B) from acute study baseline to week 26 (FAS).

Notes: Baseline was the last nonmissing assessment before the first dose of acute study medication. Analysis based on observed-case model.

Abbreviations: BID, twice daily; CGI-S, Clinical Global Impressions – Severity; FAS, full analysis set; LS, least squares; PANSS, Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale; QD, once daily.

Table S1.

List of independent ethics committees that approved the study

| Site number | Country | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 2,001 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,002 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,006 | US | University of California San Diego Human Research Protection Program |

| 2,007 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,008 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,009 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,010 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,011 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,012 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,013 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,015 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,018 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,022 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,023 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,025 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,026 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,027 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,030 | US | Aspire IRB |

| 2,101 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,102 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,104 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,104 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,107 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,108 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,109 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,111 | Bulgaria | Bulgarian Drug Agency |

| 2,127 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,129 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,130 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,131 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,133 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,134 | Romania | National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicinea |

| 2,153 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,154 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,157 | Croatia | Agency for Medical Products and Medical Devices Central Ethics Committee |

| 2,200 | Russia | Ethical Council at State Budget Healthcare Institution: Samara Psychiatric Hospital |

| 2,201 | Russia | Ethics Committee of State Budgetary Educational Institution of Higher Professional Education: Yaroslavl State Medical Academy of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,202 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,204 | Russia | Independent Interdisciplinary Ethics Committee on Ethical Review for Clinical Studies: Universimed |

| 2,206 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,209 | Russia | LEC of Mental Health Research Institute |

| 2,210 | Russia | Local Ethics Committee of State Public Healthcare Institution of Moscow Region: Central Clinical Mental Hospital |

| 2,211 | Russia | Independent Ethics Committee of Federal State Budget Institution: St Petersburg VM Bekhterev Psychoneurological Research Institute of Ministry of Healthcare of Russian Federation |

| 2,213 | Russia | Local Ethics Committee of SBHI of Sverdlovsk Region: Sverdlovsk Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital |

| 2,226 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at Territorial Medical Association of Psychiatry in Kiev |

| 2,228 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CI LRCPH |

| 2,229 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CHI Kharkiv Regional Clinical Psychiatric Hospital 3 |

| 2,231 | Ukraine | Ethics Commission at CI OI Yushchenko Academy, Vinnytsya Regional Psychoneurological Hospital |

Note:

The National Ethics Committee for the Clinical Study of Medicine is no longer in place and has since been replaced by the National Bioethics Committee for Medicine and Medical Devices.

Abbreviation: IRB, institutional review board.