Abstract

The aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms among Koreans 50 years of age or older. We used data from the 2009 to 2013 Korean Retirement and Income Panel Study (KReIS), which included data from the 365 baseline participants of 50 years of age or older. Our sample included only newly retired participants who worked in 2009, but had retired in the 2011 and 2013. To monitor the change in depressive symptoms according to retirement preparation, we used repeated measurement data. We measured depressive symptoms using the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression (CES-D) 20-item scale. In addition, we measured retirement preparation using a single self-report question asking whether the participant was financially ready for retirement. We evaluated relationship between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms after multivariable adjustment. Compared to subjects who had prepared for retirement (reference group), participants who had not prepared for retirement had increased depression scores (β = 2.49, P < 0.001). In addition, individuals who had not prepared for retirement and who had low household income had the highest increase in depression scores (β = 4.43, P < 0.001). Individuals, who had not prepared for retirement and without a national pension showed a considerable increase in depression scores (β = 3.02, P < 0.001). It is suggested that guaranteed retirement preparation is especially important for mental health of retired elderly individuals with low economic strata.

Keywords: Depression, Retirement, Income, Pensions

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Populations around the world are rapidly aging. As the aging population retires, retirement behaviors and security including poverty issues have been the subject of much attention and discussion (1). Retirees experience loss of social contacts, financial hardship, and burdensome healthcare needs, which can contribute to stress and exacerbate poor physical and mental well-being (2,3). Therefore, to adapt to these challenges, preparation for retirement is very important for the elderly population.

A growing body of research in the United States and Europe has identified a reliable relationship between retirement preparation and health outcomes including physical and psychological well-being. Studies, both cross-sectional and longitudinal study in the United States, have confirmed the positive effects of retirement preparation, including increased positive attitudes, heightened physical and mental health, and more successful transition into retirement. People who prepare for retirement are more likely to better manage physical health issues and financial planning, and thus have a positive impact on their physical and psychosocial well-being. (4,5,6). A European meta-analysis also showed evidence for positive results on retirement preparation (7). However, there is little evidence of this topic in Asian countries. Studies on Japan and China have mainly examined the relationship between retirement planning and financial literature (8,9).

Recently, Korea was confronted with increasing retirement issues in the elderly. As the baby boomer generation reaches retirement age (7,120,000 individuals retiring from 2010 to 2018), there are increased concerns about retirement issues including retirement preparation among elderly individuals (10,11). The main factors that contribute to retirement issues in the elderly include the lack of a public pension system as well as a weakened family care structure that previously played a dominant role in old-age security (11,12). These phenomena have led to a lack of retirement preparation that might contribute to poverty among the elderly, and thereby will exacerbate mental issues (13). In addition, considering that mental health problems of Korean elderly such as highest suicide rate and depression are urgent public health issues, more studies on mental health issues in terms of diverse perspective is needed (14,15). Hence, it is important to examine how the lack of retirement preparation may increase mental issues in this population. Thus, the present study used longitudinal data and focused on retirement preparation as an important factor for depression among retired elderly individuals. We examined the relationship between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms according to household income and receipt of public pension. Our hypotheses were: 1) lack of retirement preparation after retirement is associated with depressive symptoms; 2) depressive symptoms among retired elderly who is not ready for retirement is strongly associated with low income status.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Data source and study population

We used raw data from the Korean Retirement and Income Panel Study (KReIS) conducted by the National Pension Research Institute. The KReIS is one of the few large panel datasets that targets young older adults aged 50 years and older (especially early baby boomers); it includes economic status, employment, retirement and its preparation, physical and mental health status, and family relationships among middle-aged and older adults. In addition, the KReIS, which is a nationally representative sample of households, is a biennial longitudinal study with data collected in 2005, 2007, 2009, 2011, and 2013. The present study used 2009, 2011, and 2013 data because the KReIS began to include retirement preparation as a variable for the first time in 2009.

We used data from the KReIS 2009–2013 data. To analyze only newly onset retirement, our sample was restricted to individuals aged 50 years or older who responded that they worked in 2009, but they had retired in the 2011 and 2013 surveys. Among those who responded that they had retired in the 2011 and 2013 surveys, respondents maintained their retirement status until the end of follow-up. Thus, we analyzed people who retired between the 2011 and 2013 surveys, which yielded a final sample of 365 participants in the baseline population (2011). From the baseline, all participants were surveyed twice. Thus, the baseline included 365 individuals with a 2-year follow-up.

Respondents who had not provided data on retirement preparation, age, gender, education level, household income, marital status, perceived health status, limited daily activities, chronic medical conditions, retirement satisfaction, receipt of public pension, support from offspring, or living in a household were excluded from the study.

Measurement of depressive symptoms

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) that has been widely used in population-based studies (16,17). The CES-D is a 20-item scale that asks participants to indicate how frequently they experienced certain psychological symptoms or feelings over the past week. Each question is scored on a four-point scale, responses were summed for a total score (possible range 0–60).

We used the Korean version of the CES-D. It has been validated, with the α coefficient rating 0.9098 (16).

Assessment of retirement preparation

We assessed retirement preparation using a single self-report question asking whether the participant was financially ready for retirement: “Did you prepare financially for retirement?” Responses were rated on a 2-point scale: yes or no. Despite limitations due to the question's simplicity, a previous study successfully used this method based on the KReIS data (18).

Covariates

We included age, gender, education level (uneducated, less than middle school, or more than high school), household income (low, middle-low, middle-high, high), marital status (married or single, including separated, divorced, or widowed), health status (perceived health status [healthy, neutral, unhealthy], and limitation of daily activities [yes or no]), chronic mental conditions (present, absent). Retirement-related satisfaction was assessed by the question: “Overall, would you say that your retirement has turned out to be very satisfying, moderately satisfying, or not at all satisfying?” These responses were categorized as “satisfied” (very satisfying, moderately satisfying), “neutral” (neutral), or “unsatisfied” (very unsatisfying, moderately unsatisfying). Receipt of public pension was assessed by the question: “Do you receive any benefits including public pension or special occupational pension from the national pension scheme?” (yes or no). Support from offspring was assessed by asking if respondents received private transfer of income from adult offspring. Those who received private transfer of income from one or more offspring were categorized “yes;” others were categorized as “no”. To determine whether the respondents lived in a household, respondents were asked if they lived with their household. All variables surveyed by the KReIS were repeatedly measured.

Statistical analysis

The study population's general baseline characteristics were examined by t-tests, and analysis of variance was used to compare the averages and standard deviations in depressive symptom (CES-D 20) scores by characteristics. We used repeated-measurement model (generalized estimating equations) and it determine whether probability of depressive symptom changed over time. We also evaluated the relationship between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms using a generalized estimating equation (GEE) model that was an extension of the quasi-likelihood approach used to analyze longitudinal correlated data. The GEE model is used for analyzing longitudinal data, as it accounted for time variation and correlations among repeated measurements (19). All independent variables were adjusted. Subgroup analysis was performed to evaluate possible associations between depressive symptoms and retirement preparation according to household income or receipt of public pension. Statistical analyses were performed using the GENMOD Procedure from SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA). P values were 2-sided and considered significant at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

This study did not require ethical review. Because the KReIS data does not contain private information and is openly available to researchers in de-identified format, we did not have to address ethical concerns regarding informed consent.

RESULTS

The baseline characteristics of the study population are shown in Table 1. Among the 365 individuals, 67.1% (n = 245) did not prepare for retirement. The mean baseline CES-D 20 scores were 11.54 among those who did not prepare for retirement and 7.20 among those who did prepare for retirement. Regarding household income, the CES-D 20 scores were higher in subjects with low household income compared to the other income groups. In addition, the CES-D 20 scores were lower in subjects who received a public pension compared to those who did not. In total, 18.6% (n = 68) of respondents received a public pension.

Table 1. General characteristics of the study populations at the baseline (2011).

| Variables | Subjects | Depressive symptom | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | Mean ± SD | P value | |

| Retirement preparation | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 120 | 32.9 | 7.20 ± 5.94 | |

| No | 245 | 67.1 | 11.54 ± 8.66 | |

| Age, yr | 0.008 | |||

| 50–59 | 219 | 60.0 | 10.88 ± 8.40 | |

| 60–69 | 142 | 38.9 | 9.13 ± 7.62 | |

| ≥ 70 | 4 | 1.1 | 3.50 ± 1.73 | |

| Gender | 0.016 | |||

| Male | 79 | 21.6 | 11.43 ± 9.82 | |

| Female | 286 | 78.4 | 9.75 ± 7.57 | |

| Education level | 0.083 | |||

| Uneducated | 113 | 31.0 | 11.27 ± 8.13 | |

| Middle school or less | 225 | 61.6 | 10.00 ± 8.25 | |

| High school or more | 27 | 7.4 | 6.30 ± 5.68 | |

| Household income | 0.824 | |||

| Low (Q1) | 81 | 22.2 | 10.80 ± 8.62 | |

| Middle-low (Q2) | 93 | 25.5 | 11.16 ± 8.44 | |

| Middle-high (Q3) | 90 | 24.7 | 10.11 ± 7.82 | |

| High (Q4) | 101 | 27.7 | 8.61 ± 7.58 | |

| Marital status | 0.001 | |||

| Married | 319 | 87.4 | 9.63 ± 7.89 | |

| Single | 45 | 12.6 | 13.50 ± 8.99 | |

| Perceived health status | 0.478 | |||

| Healthy | 130 | 35.6 | 8.27 ± 6.60 | |

| Neutral | 121 | 33.2 | 10.32 ± 8.58 | |

| Unhealthy | 114 | 31.2 | 12.00 ± 8.79 | |

| Limitation on daily activities | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 31 | 8.5 | 19.06 ± 11.41 | |

| No | 334 | 91.5 | 9.28 ± 7.23 | |

| Chronic medical conditions | 0.939 | |||

| Present | 162 | 44.4 | 11.09 ± 8.77 | |

| Absent | 203 | 55.6 | 9.35 ± 7.51 | |

| Retirement satisfaction | 0.589 | |||

| Satisfied | 122 | 33.6 | 10.21 ± 8.49 | |

| Neutral | 205 | 56.5 | 9.76 ± 7.63 | |

| Unsatisfied | 38 | 9.9 | 11.86 ± 9.51 | |

| Receipt of national pension | 0.086 | |||

| Yes | 68 | 18.6 | 8.84 ± 8.45 | |

| No | 297 | 81.4 | 10.41 ± 8.04 | |

| Support from offspring | 0.349 | |||

| Yes | 106 | 29.0 | 10.92 ± 8.42 | |

| No | 259 | 71.0 | 9.79 ± 7.99 | |

| No. of household members | 0.329 | |||

| 1 | 26 | 7.1 | 14.23 ± 10.29 | |

| 2 | 181 | 49.6 | 9.28 ± 7.23 | |

| ≥ 3 | 158 | 43.3 | 10.40 ± 8.53 | |

| Total | 365 | 100.0 | 10.12 ± 7.35 | |

SD = standard deviation.

Table 2 shows the association between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms. Retirement preparation was found to have effect on depressive symptoms at follow-up evaluation. After adjusting for independent variables and treating those who prepared for retirement as the reference group, participants who did not prepare for retirement had a statistically significant increase in depression scores compared with those the reference group (β = 2.49; standard error [SE] = 0.64; P < 0.001). Regarding public pension receipt, participants who did not receive a public pension showed higher depression scores (β = 2.18; SE = 0.96; P = 0.023) compared with those who did receive a public pension.

Table 2. Results of the GEE analyzing the effects of retirement preparation.

| Variables | Depressive symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| β | SE | P value | |

| Retirement preparation | |||

| Yes | Reference | - | - |

| No | 2.49 | 0.64 | < 0.001 |

| Age, yr | |||

| 50–59 | Reference | - | - |

| 60–69 | −1.29 | 0.67 | 0.054 |

| ≥ 70 | −7.32 | 0.96 | < 0.001 |

| Gender | |||

| Male | Reference | - | - |

| Female | −3.68 | 0.92 | < 0.001 |

| Education level | |||

| Uneducated | Reference | - | - |

| Middle school or less | −0.28 | 0.79 | 0.717 |

| High school or more | −0.32 | 1.33 | 0.811 |

| Household income | |||

| Low (Q1) | Reference | - | - |

| Middle-low (Q2) | −0.21 | 0.95 | 0.825 |

| Middle-high (Q3) | 0.08 | 0.98 | 0.938 |

| High (Q4) | −0.57 | 1.08 | 0.596 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | Reference | - | - |

| Single | 3.51 | 1.28 | 0.006 |

| Perceived health status | |||

| Healthy | Reference | - | - |

| Neutral | 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.031 |

| Unhealthy | 2.83 | 0.9 | 0.002 |

| Limitation on daily activities | |||

| No | Reference | - | - |

| Yes | 7.58 | 1.76 | < 0.001 |

| No. of chronic medical conditions | |||

| Present | Reference | - | - |

| Absent | −0.23 | 0.63 | 0.711 |

| Retirement satisfaction | |||

| Satisfied | Reference | - | - |

| Neutral | 0.4 | 0.63 | 0.522 |

| Unsatisfied | 0.73 | 1.04 | 0.484 |

| Receipt of national pension | |||

| Yes | Reference | - | - |

| No | 2.18 | 0.96 | 0.023 |

| Support from offspring | |||

| Yes | Reference | - | - |

| No | −0.13 | 0.63 | 0.843 |

| Number of household members | |||

| 1 | Reference | - | - |

| 2 | 0.28 | 1.68 | 0.867 |

| ≥ 3 | 0.38 | 1.71 | 0.822 |

| Survey year | |||

| 2011 | Reference | - | - |

| 2013 | −1.61 | 0.55 | 0.003 |

Adjusting for age (year), gender, education level, household income, marital status, perceived health status, limit on daily activities, number of chronic medical conditions, retirement satisfaction, receipt of national pension, support from offspring, number of household members, survey year.

GEE = generalized estimating equation, SE = standard error.

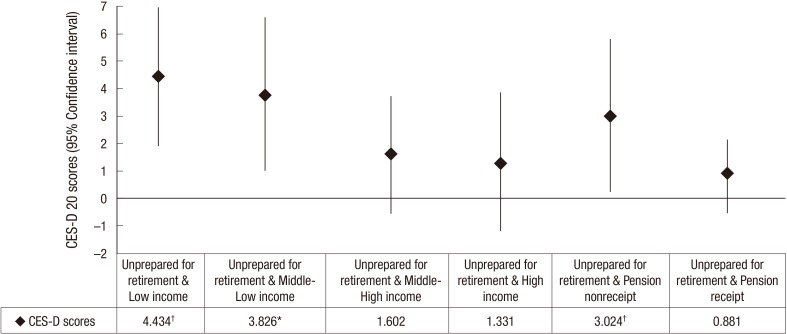

Fig. 1 shows the association between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms by household income or receipt of national pension. Individuals without retirement preparation and with a low household income showed the most drastic increase in depression scores (β = 4.43; SE = 1.29; P < 0.001). Individuals without retirement preparation and the lack of national pension also showed a significant increase in depression scores compared with individuals who had prepared for retirement but lacked national pension (β = 3.02; SE = 0.67; P < 0.001). Retirement preparation was not significantly associated with depressive symptoms among those with middle-high or high levels of household income.

Fig. 1.

Results of the GEE analyzing the effects of retirement preparation and depressive symptoms by household income or national pension receipt.

Adjusting for age, gender, education level, household income, marital status, perceived health status, limited on daily activities, number of chronic medical conditions, retirement satisfaction, receipt of national pension, support from offspring, number of household members, survey year.

GEE = generalized estimating equation, CES-D = Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression, DI = confidence interval.

*P < 0.010, †P < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

Recently, elderly Koreans including baby boomers, listed retirement planning issues as a serious financial stressor. According to a Metlife Mature Market Institute report in 2013, the economic readiness of older adults, including baby boomers, received a D grade, which meant that retirement security for retirement was seriously lacking among retirees (20). Thus, it is necessary to design effective strategies to prevent retirement issues and manage psychological wellbeing among retired elderly.

We found that lack of retirement preparation after retirement was significantly associated with depressive symptoms among the retired elderly population, after multivariable adjustment. Our findings were similar to previous studies about psychological perspective: life satisfaction for elderly retirees was affected by preparing financially for retirement. Retirees who prepared for their economic security during retirement were more likely to have better financial security, and thereby achieve higher life satisfaction (18). In addition, retirees who had not planned for retirement were less financially secure and were more likely to experience financial hardship, which exacerbated their poor psychological wellbeing (21,22).

Our findings suggested that efforts to improve mental issues and retirement security should target retired elderly who did not prepare for retirement. According to a report on the survey of household finances and living conditions in 2015, only 8.8% of households were well prepared for retirement, whereas 72.8% of households were not prepared for retirement (23). This finding means that most elderly Koreans experience lack of retirement preparation. Despite its issues remain a concern, initiatives to resolve lack of retirement preparation are rare. Thus, we suggest that retirement programs, such as financial literacy programs, should focus on supporting retired elderly who did not prepare for retirement. Many retirement studies related financial literacy programs confirmed the positive association between financial literacy and retirement preparation, and suggested that financial literacy might have a beneficial effect on retirement preparation (24,25,26,27,28,29). For example, individuals who have some level of financial literacy are more likely to prepare for financial security, because more knowledge about financial matters enables individuals to make more substantive financial plans and more sound decisions regarding allocations of their money and savings (30). Despite positive outcomes, there are no public financial literacy programs for retirees in Korea. Therefore, policy makers should develop financial literacy programs for retirees.

Our subgroup analysis indicated that the lack of retirement preparation was strongly associated with depressive symptoms among individuals with low levels of income or lack of public pension. Few studies have offered potential explanations. Economically vulnerable groups, particularly individuals with low income, are at risk for not preparing adequately for their retirement (31). Thus, economically disadvantaged elderly in particular may be more vulnerable to retirement insecurity, and thereby experience poverty and deterioration in mental health. Our finding regarding the association between lack of public pension and depressive symptoms can be explained by the importance of pension income in Korea. Of note, pension income has become more important in Korea recently because the tradition of family care that has played a dominant role in old-age security is rapidly breaking down through rapid industrialization and urbanization (12). Moreover, lack of national pension with low economic status among retired elderly influences psychological wellbeing including overall quality of life (32). Thus, lack of public pension exacerbates retirement insecurity among unprepared retirees, which results in deterioration of psychological wellbeing, manifested as depressive symptoms.

Several important insights into improving mental issues among retired elderly emerged from our data. First, lack of retirement preparation was associated with increased depressive symptoms. In addition, depressive symptoms increased most drastically among individuals with low income and no retirement preparation. Furthermore, guaranteed preparation for retirement is very important to retired elderly individuals with low economic status. Elderly individuals with high economic status have many mechanisms to ensure retirement security, such as personal pensions and reverse-mortgage loans, whereas there is no way to guarantee income security for retired elderly individuals with low economic bracket. The government should focus on retirement preparation programs for elderly individuals with the lowest incomes to help these individuals improve their retirement security. Moreover, the government could encourage all elderly individuals to prepare for retirement by developing retirement preparation programs such as financial literacy programs.

This study had several strengths compared with previous studies. First, we used a representative sample and longitudinal data collected from a nationally representative dataset. Second, to the best of our knowledge, our study was the first to report the relationship between depressive symptoms among retired elderly individuals and retirement preparation. Finally, we focused on the causes of depressive symptoms among retired elderly individuals.

Our study also had several limitations. First, a major limitation of the present study was the relatively small sample size and short follow-up periods. It is possible that we underestimated the relationship between retirement preparation and depressive symptoms. In addition, regarding the general characteristics of the baseline, there were no significant differences among the groups in some of the general risk factors for elderly depression. Hence, our findings are limited in to the interpretation of the results. Therefore, further studies on this topic are needed using a large sample size and a long follow-up period. Second, regarding the CES-D scores, higher score simply reflects greater depressive symptoms and does not necessarily imply clinical depression. It might be meaningful to categorize the CES-D score based on the cut-off point and analyze the results, but we could not evaluate this due to the small sample size. Third, we did not investigate reasons individuals had for not preparing for retirement. In addition, as causal relationships between independent variables and the dependent variable (depressive symptoms) were tested in only one direction, the results could reflect reverse causality. Therefore, we could not determine whether higher depressive symptoms caused individuals not to prepare retirement or whether there was another explanation for our results.

Despite the limitations, given that baby boomer generation reaches retirement age and that Korea is confronted with increasing retirement issues in older adults, our findings are important for public health practitioner to identify solutions for controlling aging society issues.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank National Pension Research Institute that provided data.

Footnotes

DISCLOSURE: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTION: Conceptualization: Ju YJ, Park EC. Investigation: Ju YJ, Kim W, Lee SA, Lee JE, Yoon H. Supervision: Park EC. Validation: Ju YJ, Kim W, Lee SA, Lee JE, Yoon H, Park EC. Writing - original draft: Ju YJ. Writing – review & editing: Ju YJ, Kim W, Lee JE.

References

- 1.Li J, O'Donoghue C. Incentives of retirement transition for elderly workers: an analysis of actual and simulated replacement rates in Ireland [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://ftp.iza.org/dp5865.pdf.

- 2.van der Heide I, van Rijn RM, Robroek SJ, Burdorf A, Proper KI. Is retirement good for your health? A systematic review of longitudinal studies. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:1180. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Solinge H. Health change in retirement: a longitudinal study among older workers in the Netherlands. Res Aging. 2007;29:225–256. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albert LC. A three part study on the relationship between retirement planning and health [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=3436&context=etd.

- 5.Wang M. Profiling retirees in the retirement transition and adjustment process: examining the longitudinal change patterns of retirees’ psychological well-being. J Appl Psychol. 2007;92:455–474. doi: 10.1037/0021-9010.92.2.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Noone JH, Stephens C, Alpass FM. Preretirement planning and well-being in later life: a prospective study. Res Aging. 2009;31:295–317. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Topa G, Moriano JA, Depolo M, Alcover CM, Morales JF. Antecedents and consequences of retirement planning and decision-making: a meta-analysis and model. J Vocat Behav. 2009;75:38–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuan H, Yang S. The survey of financial literacy in Shanghai. Int J Manag Stud Res. 2014;2:46–54. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sekita S. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Japan. J Pension Econ Finance. 2011;10:637–656. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang JJ, Klassen TR. Retirement, Work and Pensions in Ageing Korea. New York, NY: Routledge; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jones RS, Urasawa S. Reducing income inequality and poverty and promoting social mobility in Korea [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/5jz0wh6l5p7l-en.

- 12.Kim EH, Cook PJ. Response of family elder support to changes in the income of the elderly in Korea [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://paa2010.princeton.edu/papers/100200.

- 13.Nam SJ. Income mobility of elderly households in Korea. Int J Consum Stud. 2015;39:316–323. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2015: OECD Indicators [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/19991312.

- 15.Kim SW, Yoon JS. Suicide, an urgent health issue in Korea. J Korean Med Sci. 2013;28:345–347. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2013.28.3.345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cho MJ, Kim KH. Diagnostic validity of the CES-D (Korean version) in the assessment of DSM-III-R major depression. J Korean Neuropsychiatr Assoc. 1993;32(9):381–399. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: a self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Appl Psychol Meas. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park J, Park A. Longitudinal effects of economic preparation and social activities on life and family relationship satisfaction among retirees. Asian Soc Work Policy Rev. 2016;10:50–60. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ballinger GA. Using generalized estimating equations for longitudinal data analysis. Organ Res Methods. 2004;7:127–150. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Han G, Choe H, Eun KS, Lee J, Joo SH, Kim J. Korean baby boomers in transition: major findings from the MetLife study on the boomer population in Korea [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at https://www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2011/mmi-korean-boomers-.pdf.

- 21.Hervé C, Bailly N, Joulain M, Alaphilippe D. Comparative study of the quality of adaptation and satisfaction with life of retirees according to retiring age. Psychology (Irvine) 2012;3:322–327. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donaldson T, Earl JK, Muratore AM. Extending the integrated model of retirement adjustment: incorporating mastery and retirement planning. J Vocat Behav. 2010;77:279–289. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Statistics Korea. Report on the survey of housdhold finances and living conditions [Internet] [accessed on 20 June 2017]. Available at http://kostat.go.kr/portal/korea/kor_nw/2/4/4/index.board?bmode=download&bSeq=&aSeq=350552&ord=4.

- 24.Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the United States. J Pension Econ Finance. 2011;10:509–525. doi: 10.1017/S1474747211000448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bucher-Koenen T, Lusardi A. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Germany. J Pension Econ Finance. 2011;10:565–584. [Google Scholar]

- 26.van Rooij MC, Lusardi A, Alessie RJ. Financial literacy and retirement planning in the Netherlands. J Econ Psychol. 2011;32(9):593–608. [Google Scholar]

- 27.van Rooij MC, Lusardi A, Alessie RJ. Financial literacy, retirement planning and household wealth. Econ J. 2012;122:449–478. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Almenberg J, Säve-Söderbergh J. Financial literacy and retirement planning in Sweden. J Pension Econ Finance. 2011;10:585–598. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klapper L, Panos GA. Financial literacy and retirement planning: the Russian case. J Pension Econ Finance. 2011;10:599–618. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mahdzan NS, Tabiani S. The impact of financial literacy on individual saving: an exploratory study in the Malaysian context. Transform Bus Econ. 2013;12:41–55. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lusardi A, Mitchell OS. Baby boomer retirement security: the roles of planning, financial literacy, and housing wealth. J Monet Econ. 2007;54:205–224. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ju YJ, Han KT, Lee HJ, Lee JE, Choi JW, Hyun IS, Park EC. Quality of life and national pension receipt after retirement among older adults. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016 doi: 10.1111/ggi.12846. Forthcoming. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]