Abstract

Objective

To examine differences in health information seeking between U.S.-born and foreign-born populations in the U.S.

Design

Data from 2008 to 2014 from the Health Information National Trends Survey were used in this study (n = 15,249). Bivariate analyses, logistic regression, and predicted probabilities were used to examine health information seeking and sources of health information.

Results

Findings demonstrate that 59.3% of the Hispanic foreign-born population reported looking for health information, fewer than other racial/ethnic groups in the sample. Compared with non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black (OR = 0.62) and Hispanic foreign-born individuals (OR = 0.31) were the least likely to use the internet as a first source for health information. Adjustment for language preference explains much of the disparity in health information seeking between the Hispanic foreign-born population and Whites; controlling for nativity, respondents who prefer Spanish have 0.25 the odds of using the internet as a first source of health information compared to those who prefer English.

Conclusion

Foreign-born nativity and language preference are significant determinants of health information seeking. Further research is needed to better understand how information seeking patterns can influence health care use, and ultimately health outcomes. To best serve diverse racial and ethnic minority populations, health care systems, health care providers, and public health professionals must provide culturally competent health information resources to strengthen access and use by vulnerable populations, and to ensure that all populations are able to benefit from evolving health information sources in the digital age.

Keywords: Health information seeking, health information sources, immigrant health, health promotion, digital disparities

As health information sources continue to expand and evolve in online and mobile platforms, people have a greater likelihood of searching for and accessing health information on their own (Fox and Duggan 2013). At the same time, changing health care systems and policies that increase online access to health management services and health care providers place a greater responsibility on the health consumer to access and utilize these resources. Of concern is that different populations may have varying rates of access to and use of new and emerging information sources. As much effort has been put into strengthening the presence of digital health information, differences in health information seeking, as well differences in the ability to use and apply this information, may place certain populations and sub-groups at a disadvantage in accessing and utilizing the most up-to-date and relevant care information (Peña-Purcell 2008). This is particularly problematic given a growing non-English speaking immigrant population in the U.S., many of whom have little to no experience with the U.S. health care system (Huang, Yu, and Ledsky 2006; Ortega et al. 2007) and who may also have variable access to and use of online and digital technologies, especially those with language-appropriate resources (Kontos et al. 2010). While increased access to technologies among minority and immigrant populations has been a major success in reducing the digital divide, recent literature has highlighted other digital disparities including low digital literacy that may limit utilization and functionality of digital technologies among underserved and immigrant populations (Wei et al. 2010; Zach et al. 2012).

Given the growing resources for health information, emerging research has examined racial/ethnic differences in access and use of health information (Nguyen and Bellamy 2006; Rutten, Squiers, and Hesse 2006; Kontos et al. 2011; Richardson and Allen 2012; Rooks et al. 2012; Kontos and Blake 2014). This research has shown consistent differences between racial/ethnic minorities and Whites. Specifically, minority populations are less likely to look for health information. While this research has documented racial/ethnic differences, few studies have examined health information seeking among foreign-born, immigrant populations. Research on this topic has mostly been qualitative, focusing on information pathways in specific immigrant groups (e.g. Korean immigrants) and/or certain types of health information (e.g. cancer health information) (Britigan, Murnan, and Rojas-Guyler 2009; Nguyen and Shungu 2010; Selsky, Luta, and Noone 2013; Wang and Yu 2014; Lubetkin and Zabor 2015). This research has suggested distinct cultural norms in terms of preferences for health information. The limited population-based research has found differences between U.S. and foreign-born Hispanic populations, but has largely focused on cancer information seeking (Vanderpool et al. 2009; Zhao 2010).

The present study builds upon the existing body of research by using population-based survey data to examine differences in health information seeking between U.S.-born populations and the large and growing non-English speaking immigrant population in the US, as well as drivers of health information seeking. We believe it is critical to understand health information seeking behaviors of non-English speaking immigrants, many of whom speak primarily Spanish, because they are a large and growing segment of the population (Brown 2015); they face several unique barriers to accessing high quality health care, including that recent immigrants are excluded from many public health insurance programs (e.g. Medicaid expansion and insurance marketplaces implemented under the ACA); and the post-migration period likely represents a critical transition period in the life course during which immigrants are exposed to different behavior patterns, social norms, and resources. Assessing the extent to which the foreign-born and Spanish speakers access and use varying sources of health information will help inform tailored intervention strategies targeted toward this group. Our study is guided by the following hypotheses:

Foreign-born Hispanics will demonstrate different patterns of health information seeking relative to both non-Hispanic Whites and U.S.-born Hispanics.

These differences will be explained in large part by language preference.

Method

Data and sample

Five iterations of the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) – HINTS 3 and HINTS 4 Cycles 1–4 – were used in this study. Data were collected from 2008 to 2014 with response rates of 21% (HINTS 3 telephone), 31% (HINTS 3 address), 37% (HINTS 4–1), 40% (HINTS 4–2), 35% (HINTS 4–3), and 34% (HINTS 4–4) which is consistent with prior studies in public opinion research (Fox and Jones 2009; The American Association for Public Opinion Research 2016). HINTS 3 implemented a mixed mode data collection method using both telephone and address-based methods, while HINTS 4 cycles used only address-based methods. Mode-specific weights were used in analysis to adjust for data collection method (Cantor and McBride 2009). A total of 15,249 respondents were included in the study sample.

Measures

This study examined two main outcomes: health information seeking and first source of health information. Health information seeking: respondents were asked if they had ever looked for health information (yes/no). First source of health information: respondents who indicated looking for health information were asked to identify the first source that they use. The variable contains five categories, including: internet, health professional, family or friends, print material, and other source.

Key strata: examining racial/ethnic and foreign-born differences in health information seeking behaviors was a central component of this study. Two variables – race/ethnicity and nativity – were combined to create the new variable with categories including U.S.-born non-Hispanic White, U.S.-born non-Hispanic Black, U.S.-born Hispanic, foreign-born Hispanic, U.S.-born other, and foreign-born other. In addition, a language variable (English or Spanish) was used to determine respondents’ language preference, based on the language of survey completion.

Covariates: key socio-demographic and health-related variables include age in years (categorical, 18–34, 35–49, 50–64, 65–74, 75+), education (less than high school, high school graduate, some college, college graduate), gender (male/female), health insurance (yes/no), regular provider (yes/no), frequency of health care visits in past year (none, 1–2, 3–4, 5+), ever had cancer (yes/no), and for whom the health information was intended (myself, someone else, or both myself and someone else).

Analysis

Weighted data were used to produce nationally representative estimates of the U.S. adult population (Rizzo et al. 2008). Descriptive statistics described respondent socio-demographics and key covariates by the race/ethnicity foreign-born variable. Bivariate analyses were used to examine key outcomes by the race/ethnicity foreign-born variable and language preference, including source of health information. Logistic regression was used to model health information source on the race/ethnicity foreign-born variable, adjusting for other key covariates. Predicted probabilities for health information source were calculated using the margins command in Stata 14, with all independent variables set to their mean values. All analyses were conducted in Stata 14 (StataCorp 2015).

Results

Socio-demographic and health-related variables

Table 1 describes weighted socio-demographics and health-related variables by race/ethnicity and nativity. Non-Hispanic White respondents made up the largest racial/ethnic group at 67.8%, followed by non-Hispanic Blacks at 9.9%. All socio-demographic and health variables varied significantly across racial/ethnic groups. Most notably, compared to all other racial/ethnic categories, Hispanic foreign-born respondents displayed lower educational attainment (43.4% with less than high school), the lowest percentage of having a regular doctor (43.1%), the highest percentage of not receiving health care in the past year (33.4%), and the lowest percentage of health insurance (59.7%). Other foreign-born respondents displayed a similarly low percentage of having a regular provider (47.8%) and high percentage of not receiving health care in the past year (33.3%). Among Hispanic respondents, 5.3% of U.S.-born respondents completed the survey in Spanish, compared to 54.6% of foreign-born respondents.

Table 1.

Weighted descriptive statistics among study population, HINTS 3, HINTS 4 Cycles 1–4; 2008–2014; n = 15,249.

| Non-Hispanic white |

Non-Hispanic black |

Hispanic U.S. born |

Hispanic foreign born |

Other U.S. born |

Other foreign born |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||

| % | SE (%) | % | SE (%) | % | SE (%) | % | SE (%) | % | SE (%) | % | SE (%) | |

| Race/ethnicity | 67.8 | 0.2 | 9.9 | 0.2 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 7.5 | 0.3 | 3.2 | 0.2 | 4.0 | 0.2 |

| Age group | ||||||||||||

| 18–34 | 27.2 | 0.4 | 34.6 | 2.1 | 54.1 | 2.3 | 29.3 | 2.2 | 49.3 | 4.5 | 34.8 | 3.7 |

| 35–49 | 27.1 | 0.3 | 29.2 | 1.8 | 24.9 | 1.9 | 41.7 | 2.1 | 22.3 | 2.9 | 39.1 | 3.1 |

| 50–64 | 27.2 | 0.3 | 24.5 | 1.2 | 13.4 | 1.1 | 20.6 | 1.5 | 20.7 | 2.4 | 18.0 | 2.2 |

| 65–74 | 10.0 | 0.2 | 7.2 | 0.6 | 4.3 | 0.6 | 5.3 | 0.6 | 4.6 | 0.9 | 5.4 | 1.1 |

| 75+ | 8.5 | 0.2 | 4.5 | 0.5 | 3.3 | 0.7 | 3.2 | 0.5 | 3.2 | 0.7 | 2.6 | 0.8 |

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Female | 51.8 | 0.3 | 58.5 | 2.0 | 47.4 | 2.4 | 50.4 | 2.0 | 50.2 | 4.4 | 44.8 | 3.4 |

| Education | ||||||||||||

| Less than high school | 6.8 | 0.3 | 16.8 | 1.6 | 16.6 | 2.3 | 43.4 | 2.0 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 9.3 | 2.0 |

| High school graduate | 22.8 | 0.5 | 26.5 | 1.8 | 20.9 | 1.8 | 22.0 | 2.0 | 17.0 | 2.9 | 13.6 | 2.7 |

| Some college | 37.2 | 0.6 | 29.7 | 1.8 | 33.8 | 2.3 | 19.3 | 1.6 | 35.3 | 5.1 | 13.3 | 2.4 |

| College graduate | 33.1 | 0.4 | 26.9 | 1.5 | 28.8 | 2.1 | 15.2 | 1.3 | 41.2 | 4.0 | 63.8 | 3.3 |

| Regular doctor | ||||||||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 72.0 | 0.7 | 61.0 | 2.0 | 53.6 | 2.8 | 43.1 | 2.3 | 63.9 | 4.4 | 47.8 | 3.6 |

| Number of health visits in past year | ||||||||||||

| None | 15.3 | 0.6 | 18.5 | 1.9 | 23.4 | 2.2 | 33.4 | 2.5 | 19.7 | 3.2 | 33.3 | 4.1 |

| Ever had cancer | ||||||||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 9.7 | 0.2 | 4.8 | 0.5 | 3.8 | 0.6 | 4.2 | 0.8 | 5.6 | 1.0 | 2.5 | 0.7 |

| Health insurance | ||||||||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 87.8 | 0.5 | 75.7 | 2.1 | 79.0 | 2.0 | 59.7 | 2.3 | 88.2 | 2.4 | 82.0 | 3.3 |

| Language preference | ||||||||||||

| Spanish | – | – | – | – | 5.3 | 1.0 | 54.6 | 2.4 | – | – | – | – |

| Ever looked for health information? | ||||||||||||

| Yes (vs. No) | 81.4 | 0.6 | 71.2 | 2.0 | 70.3 | 2.8 | 59.3 | 2.3 | 80.7 | 3.9 | 69.0 | 3.5 |

At 81.4%, non-Hispanic White respondents represented the largest group percentage who had looked for health information, compared with 59.3% of Hispanic foreign-born respondents. Non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic U.S.-born, and other foreign-born respondents had similar percentages of health information seeking, at 71.2%, 70.3%, and 69.0%, respectively.

First source of health information

Among the sub-sample of respondents who had looked for health information (n = 10,614), Table 2 describes the source of health information, stratifying by race/ethnicity and nativity, and language preference. Non-Hispanic White, Hispanic U.S.-born, other U.S.-born, and other foreign-born respondents demonstrated similar information seeking patterns, with more than 70% in each group turning to the internet as a first source for health information. In contrast, only 64.8% of non-Hispanic Black respondents and 48.1% of Hispanic foreign-born respondents turned to the internet as a first source of health information.

Table 2.

Health information-seeking behaviors by race/ethnicity and language preference among respondents of HINTS 3, HINTS 4 Cycles 1–4; 2008–2014; n = 10,614.

| Source of health information | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Internet (%) [95% CI] |

Health professional (%) [95% CI] |

Print material (%) [95% CI] |

Family or friend (%) [95% CI] |

Other source (%) [95% CI] |

|||||||||||

| Race/Ethnicity* | |||||||||||||||

| Non-Hisp. White | 74.8 | 11.7 | 8.5 | 3.7 | 1.4 | ||||||||||

| [73.3 | 76.2] | [10.6 | 12.7] | [7.7 | 9.3] | [2.9 | 4.4] | [1.0 | 1.7] | ||||||

| Non-Hisp. Black | 64.8 | 15.9 | 12.1 | 6.0 | 1.2 | ||||||||||

| [60.3 | 69.4] | [12.7 | 19.2] | [9.6 | 14.6] | [3.4 | 8.6] | [0.5 | 1.9] | ||||||

| Hisp. U.S. born | 71.7 | 10.6 | 11.8 | 4.8 | 1.1 | ||||||||||

| [65.6 | 77.8] | [7.3 | 13.9] | [7.2 | 16.3] | [1.4 | 8.3] | [0.2 | 1.9] | ||||||

| Hisp. foreign born | 48.1 | 25.2 | 17.4 | 6.2 | 3.1 | ||||||||||

| [41.9 | 54.3] | [19.5 | 30.9] | [13.2 | 21.7] | [3.3 | 9.1] | [1.2 | 5.0] | ||||||

| Other U.S. born | 74.2 | 12.5 | 6.5 | 6.1 | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| [65.9 | 82.5] | [5.8 | 19.1] | [3.4 | 9.6] | [2.2 | 10.1] | [0.0 | 1.4] | ||||||

| Other foreign born | 72.0 | 11.3 | 9.2 | 6.9 | 0.7 | ||||||||||

| [64.8 | 79.2] | [6.2 | 16.3] | [5.0 | 13.3] | [2.5 | 11.3] | [0.0 | 1.6] | ||||||

| Language preference* | |||||||||||||||

| English | 73.3 | 12.1 | 9.2 | 4.2 | 1.3 | ||||||||||

| [72.0 | 74.6] | [11.2 | 13.0] | [8.4 | 10.0] | [3.6 | 4.9] | [1.0 | 1.5] | ||||||

| Spanish | 29.8 | 35.3 | 21.4 | 7.7 | 5.8 | ||||||||||

| [22.9 | 37.9] | [27.0 | 44.6] | [15.7 | 28.4] | [3.7 | 15.2] | [3.1 | 10.8] | ||||||

| Total | 72.0 | 12.8 | 9.5 | 4.3 | 1.4 | ||||||||||

| [70.8 | 73.3] | [11.8 | 13.7] | [8.7 | 10.3] | [3.6 | 5.0] | [1.1 | 1.6] | ||||||

p < .001.

Among all six groups, Hispanic foreign-born respondents used health professionals the most as a first source of health information (25.2%). Relative to other groups, Hispanic foreign-born respondents also demonstrated the largest percentage of those who used print material (17.4%) as a first source of health information.

When examining first source of health information by language preference, there are significant differences between groups. Compared to 73.3% of respondents who prefer English, 29.8% of respondents who prefer Spanish used the internet as the first source of health information, a significantly lower percentage (p < .001). Large significant differences were also observed among respondents whose first source was a health professional (English 12.1% compared to Spanish 35.3%, p < .001) and print material (English 9.2% compared to Spanish 21.4%, p < .001).

Table 3 displays unadjusted and adjusted models for first source of health information among the sub-sample of participants who had looked for health information. The unadjusted models demonstrate the relationship between the race/ethnicity foreign-born variable and health information source. When examining the internet model, compared to non-Hispanic White respondents, non-Hispanic Black (OR = 0.62, 95% CI = 0.50, 0.77) and Hispanic foreign born (OR = 0.31, 95% CI = 0.24, 0.40) both had lower odds of using the internet as a first source of health information. After adjusting for key covariates including language preference, the internet model demonstrates the same significant relationship with non-Hispanic Black respondents; however, among Hispanic foreign-born respondents there is no longer a significant difference. The adjusted model demonstrates that compared to respondents who prefer English, respondents who prefer Spanish have 0.25 the odds of using the internet as a first source of health information (95% CI = 0.14, 0.44).

Table 3.

Logistic regression models predicting use of health information source, HINTS 3, HINTS 4 Cycles 1–4; 2008–2014; n = 10,614.

| Internet | Doctor | Family/friend | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||

| Unadjusted | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (ref: non-Hisp White) | ||||||||||||

| non-Hisp. Black | 0.62** | 0.50 | 0.77 | 1.43* | 1.10 | 1.86 | 1.37* | 1.15 | 1.89 | 1.67 | 0.98 | 2.86 |

| Hisp. U.S. born | 0.86 | 0.63 | 1.17 | 0.90 | 0.63 | 1.29 | 1.43 | 0.91 | 2.25 | 1.33 | 0.57 | 3.08 |

| Hisp. foreign born | 0.31** | 0.24 | 0.40 | 2.55** | 1.87 | 3.47 | 2.27** | 1.66 | 3.09 | 1.72 | 0.98 | 3.03 |

| Other U.S. born | 0.96 | 0.61 | 1.49 | 1.09 | 0.57 | 2.09 | 0.75 | 0.44 | 1.29 | 1.73 | 0.80 | 3.76 |

| Other foreign born | 0.86 | 0.59 | 1.25 | 0.98 | 0.58 | 1.66 | 1.06 | 0.62 | 1.83 | 1.97 | 0.92 | 4.22 |

| Adjusted models | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | ||||

| Race/ethnicity (ref: non-Hisp White) | ||||||||||||

| non-Hisp. Black | 0.58** | 0.46 | 0.73 | 1.52* | 1.14 | 2.03 | 1.64** | 1.25 | 2.16 | 1.46 | 0.86 | 2.50 |

| Hisp. U.S. born | 0.70* | 0.50 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.71 | 1.50 | 1.96* | 1.23 | 3.13 | 1.10 | 0.47 | 2.55 |

| Hisp. foreign born | 0.69 | 0.47 | 1.01 | 1.37 | 0.87 | 2.16 | 1.84* | 1.11 | 3.05 | 0.88 | 0.33 | 2.34 |

| Other U.S. born | 0.63* | 0.40 | 0.99 | 1.62 | 0.80 | 3.27 | 1.06 | 0.60 | 1.87 | 1.72 | 0.78 | 3.78 |

| Other foreign born | 0.56* | 0.38 | 0.85 | 1.85* | 1.06 | 3.25 | 1.25 | 0.72 | 2.18 | 1.79 | 0.81 | 3.96 |

| Gender (ref: female) | ||||||||||||

| Male | 1.01 | 0.87 | 1.17 | 0.91 | 0.75 | 1.10 | 1.21 | 1.00 | 1.47 | 0.77 | 0.54 | 1.11 |

| Education (ref: Less than HS) | ||||||||||||

| HS graduate | 2.29** | 1.65 | 3.20 | 0.59* | 0.40 | 0.86 | 0.74 | 0.52 | 1.06 | 0.71 | 0.40 | 1.26 |

| Some college | 3.67** | 2.66 | 5.07 | 0.49** | 0.34 | 0.70 | 0.56** | 0.39 | 0.79 | 0.26 | 0.14 | 0.49 |

| College graduate | 5.19** | 3.76 | 7.15 | 0.30** | 0.21 | 0.42 | 0.45** | 0.32 | 0.65 | 0.31 | 0.17 | 0.58 |

| Age group (ref: 18–34) | ||||||||||||

| 35–49 | 0.72* | 0.57 | 0.92 | 1.34 | 0.94 | 1.92 | 1.73* | 1.16 | 2.58 | 0.78 | 0.48 | 1.27 |

| 50–64 | 0.46** | 0.37 | 0.57 | 1.97** | 1.46 | 2.67 | 2.89** | 2.02 | 4.14 | 0.71 | 0.44 | 1.14 |

| 65–74 | 0.22** | 0.17 | 0.28 | 3.16** | 2.19 | 4.55 | 6.36** | 4.36 | 9.29 | 0.88 | 0.51 | 1.53 |

| 75+ | 0.10** | 0.07 | 0.13 | 5.34** | 3.74 | 7.63 | 9.52** | 6.29 | 14.39 | 1.01 | 0.54 | 1.91 |

| Frequency of health care past year (ref: none) | ||||||||||||

| 1–2 times | 1.27 | 1.00 | 1.62 | 1.53* | 1.04 | 2.24 | 0.53** | 0.38 | 0.74 | 0.76 | 0.48 | 1.22 |

| 3–4 times | 1.09 | 0.83 | 1.44 | 2.15** | 1.45 | 3.20 | 0.51** | 0.36 | 0.73 | 0.62 | 0.32 | 1.18 |

| 5 or more | 1.00 | 0.75 | 1.34 | 2.47** | 1.62 | 3.78 | 0.47** | 0.33 | 0.69 | 0.75 | 0.42 | 1.36 |

| Who looking for? (ref: myself) | ||||||||||||

| Someone else | 1.52** | 1.26 | 1.84 | 0.56** | 0.43 | 0.73 | 1.01 | 0.79 | 1.29 | 0.73 | 0.46 | 1.15 |

| Both myself and someone else | 0.89 | 0.75 | 1.06 | 0.89 | 0.71 | 1.11 | 1.64** | 1.33 | 2.03 | 0.86 | 0.59 | 1.24 |

| Language preference (ref: English) | ||||||||||||

| Spanish | 0.25** | 0.14 | 0.44 | 3.24** | 1.86 | 5.63 | 1.39 | 0.69 | 2.81 | 1.38 | 0.32 | 5.93 |

Note: Model statistics are odds ratios. All adjusted models also control for the following variables: health insurance status, having a regular provider, ever having cancer, survey mode collection, survey year. Sub-sample is restricted to participants who report having ever looked for health information.

p < .05.

p < .001.

The unadjusted and adjusted health professional models demonstrate similar patterns for both non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic foreign-born respondents. In both models, non-Hispanic Black respondents have higher odds of using a health professional as a first source compared to non-Hispanic White (AOR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.14, 2.03). Among Hispanic foreign-born respondents, the unadjusted model shows higher odds of using a health professional as a first source compared to non-Hispanic Whites; however, after adjusting for language, this relationship is no longer significant with language preference now becoming a significant predictor (Spanish OR = 3.24, 95% CI = 1.86, 5.63).

Finally, in the unadjusted print material model, compared with non-Hispanic White respondents, non-Hispanic Black (OR = 1.37, 95% CI = 1.15, 1.89) and Hispanic foreign born (OR = 2.27, 95% CI = 1.66, 3.09) have higher odds of using print materials for health information. After adjusting for language preference, both significant relationships remain, as well as a new significant relationship with Hispanic U.S. born compared to non-Hispanic Whites (OR = 1.96, 95% CI = 1.23, 3.13). The language preference variable is not significantly associated with using print material as a first source for health information.

Results in Table 3 also display differences based on who the information was for. In the internet model, respondents looking for information for someone else had higher odds of using the internet compared with those looking for information only for themselves (OR = 1.52, 95% CI = 1.26, 1.84). Whereas the print material model suggests that, compared with respondents only looking for themselves, respondents looking for both themselves and others have higher odds of using print materials (OR = 1.64, 95% CI = 1.33, 2.03). When respondents use health professionals as a first source of information, they have lower odds of using this source to look for someone else compared to themselves (OR = 0.56, 95% CI = 0.43, 0.73).

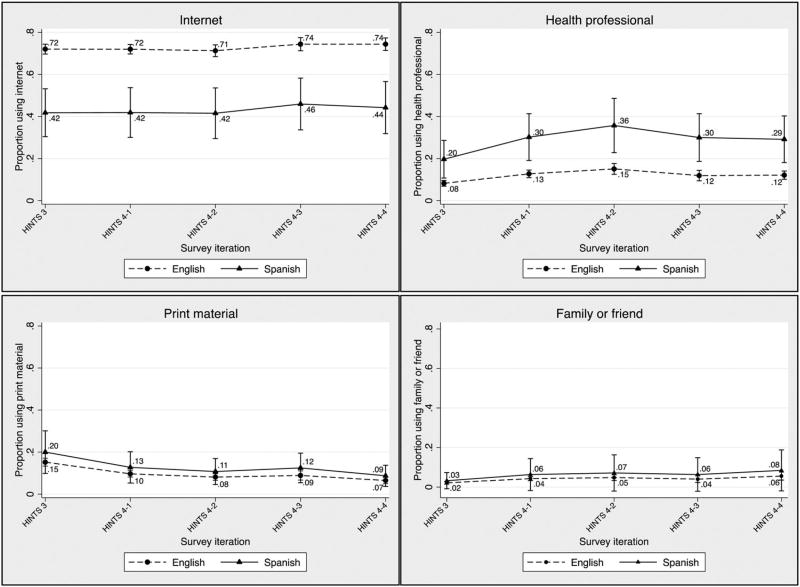

Based on the significant relationship between language preference and health information source described in Table 3, predicted probabilities were used to examine trends in information source over time from 2008 to 2014. Figure 1 shows that differences in information source based on language preference remain constant over the five survey iterations, particularly the significant difference observed in using the internet as a first information source.

Figure 1.

Adjusted and weighted predicted probabilities with 95% confidence intervals of first source of health information by language preference, HINTS 3, HINTS 4 Cycles 1–4 (n = 10,614). HINTS = Health Information National Trends Survey.

Discussion

Findings from this study demonstrate that language preference is an important driver of health information-seeking disparities between foreign-born Hispanics (i.e. those born outside of the US) and other racial/ethnic groups. Hispanic foreign-born individuals were less likely than other groups to look for health information, less likely to use the internet as a first source for health information, but most likely to use a health professional. Adjustment for language differences between racial/ethnic groups suggests that the association between nativity and information source is largely explained by respondent language preference. That is, foreign-born Hispanic populations differ greatly in the first source of health information based on language preference. This study builds upon literature examining unique health information needs and behaviors of non-English speakers, and in particular Spanish speakers. Specifically, Spanish speakers demonstrate a lower trust in media and lower use in various media channels (Clayman et al. 2010), and have differential home access to computers and broadband (Manganello et al. 2015).

The consistent differences observed between 2008 and 2014 in use of health information sources based on language preference, particularly internet information sources, is troublesome in a digital age that strives to create greater access and transparency to health information and communication. This study suggests that only certain populations are benefiting from the expanding digital health information age, while others (i.e. non-English speakers) may be subjected to a widening information gap. This builds upon research highlighting barriers to accessing much of the health information found online, particularly at sites ending in .edu and Wikipedia sites, as most are in English and require high literacy levels to read and comprehend (Mcinnes and Haglund 2011).

As health information resources continue to evolve, understanding the culture of information seeking and leveraging the interactive component of evolving mobile health information sources can be used to tailor resources for diverse audiences by. For instance, information seeking among culturally diverse populations may inherently be more interpersonal than individualized, as demonstrated by the high use of health professionals. Moreover, understanding this culture of information seeking can help target and engage information gatekeepers. Kontos et al. (2011) found that identifying as a health information maven, that is, an individual whose health knowledge is general as opposed to specific and expert, was associated with fewer years in the US and lower language acculturation (Kontos et al. 2011). Strategies that engage gatekeepers and mavens may be an effective way to disseminate health information in diverse cultural and non-English speaking networks. Furthermore, considering this when designing health information resources may prove to be a valuable way to increase the use of technology-based information sources that are championed and disseminated through these community gatekeepers and mavens.

Emerging mobile health (mHealth) information sources may also help increase access to health information for some populations, as smartphones and mobile technologies are more affordable and accessible than traditional computers and broadband. Specifically, mHealth strategies have the potential to impact health disparities populations, as Hispanic, African-American, and younger populations are more likely than White and older respondents to use mobile technologies for health information (Fox and Duggan 2012; Leite et al. 2014). When examining smartphone ownership in a national sample by race/ethnicity, Hispanic youth have the highest smartphone ownership rate at 43%, compared with 40% among African-Americans and 35% among Whites (Lenhart et al. 2010; Zickuhr and Smith 2012). These data indicate an opportunity to reach and engage a diverse audience through smartphones and mHealth strategies. More specifically, given the ability to use various applications and platforms on these devices, more work is needed to explore the cross-platform utilization patterns to develop ‘user-centered’ and more interactive strategies. Importantly, given the differential access to home computers and broadband among non-English speaking populations (Manganello et al. 2015), mHealth strategies may be more accessible and useful as an information source for diverse minority and immigrant audiences.

Strategies that improve the availability and access to Spanish-language digital resources will be paramount to reduce the digital disparities observed in health information seeking. These strategies can build on existing interactive media strategies that utilize traditional media platforms, for instance radio. Ramirez et al. (2015) analyzed calls made to a Spanish radio program hosted by a doctor to answer health-related questions (Ramirez et al. 2015), and found that half of callers needed clarification about a previous medical visit and nearly half of callers were parents calling on behalf of children. The authors discuss potential cultural barriers (respeto) that foreign-born individuals or Spanish speakers may experience during a medical encounter that then necessitates the follow up clarification. Developing digital online resources that allow for consumer interaction may help connect parents or health consumers with similar concerns.

Limitations

This study has some limitations. First, self-report survey data is subject to recall bias that may impact findings. For instance, a respondent could have difficultly remembering the first source used for health information. Despite this potential bias, nationally representative survey data provide relatively stable population-based estimates for key indicators and also highlight current behavioral patterns and trends. Second, this study is a secondary analysis and therefore limited to variables available in the HINTS data. Thus, important aspects of health information seeking (e.g. frequency, satisfaction, knowledge, and comprehension) were not examined as part of this study, including no measure of health literacy or eHealth literacy to assess the association of skills with information preferences. Third, we only had language information for Spanish speakers, a critically important population to study as they make up the largest group of non-English speakers in this US. However, immigrants who speak other non-English languages besides Spanish may have even greater challenges accessing health information in their preferred languages.

Finally, regarding the use of online health information sources, we cannot say from our data that the low use of the internet for health information among participants who prefer Spanish language is a direct result of a lower number of Spanish-language online health resources. Rather, we underscore the importance of making these resources available as behaviors shift toward use of digital resources. For example, not all of the resources listed in the ‘Top 100 List of Health Websites You Can Trust’, produced in September 2015 by the Consumer and Patient Health Information Section (CAPHIS) of the Medical Library Association, are available in Spanish – including the ‘Top 100 List’ itself (resource found at http://caphis.mlanet.org).

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. HINTS is the most comprehensive and inclusive population-based study of health communication and health information seeking of which we are aware. Further, to our knowledge, no previous study has examined disparities across racial/ethnic and immigrant groups in health information seeking and source. Given the large and persistent differences we observed across groups, we believe that this study makes a meaningful and important contribution to the existing literature.

Implications for practice

This study shows that health information-seeking behaviors vary between racial/ethnic groups as well as by language preference, specifically English compared to Spanish. Given these differences in health information seeking, further research is needed to better understand how information seeking patterns can influence health care use, quality of care, and ultimately health outcomes. When available, culturally and linguistically competent websites that provide disease-specific health information for immigrant populations have been well utilized (Simone et al. 2012; Londra et al. 2014; Liu, Haukoos, and Sasson 2014; Wang and Yu 2014). However, understanding how these resources strengthen quality of care and service utilization requires additional investigation, particularly when considering the culture and context of health information seeking.

This is particularly important given large health disparities between racial/ethnic groups (Narayan et al. 2003; Flegal et al. 2012; Dominguez et al. 2015), as well as the considerable heterogeneity within minority populations. Many immigrant groups, including Hispanic sub-populations (i.e. Mexican origin), show better health status than would be expected given their socioeconomic status (termed ‘the immigrant health paradox’); however, this ‘immigrant advantage’ in health tends to erode with time in the US and across generations, such that the health indicators of longer-tenured immigrants and their offspring are similar to other native-born populations (Derose, Escarce, and Lurie 2007). These health disparities have been attributed to a variety of factors at multiple levels of influence, including those at the patient-, provider-, and system-levels (Andersen 1995; Fiscella et al. 2000; Bach et al. 2004). Identifying well-informed, culturally competent strategies to improve health communication among recent immigrants may help this population retain the health advantage with which they arrive to the US. More broadly, to understand the dynamic influence of health information seeking on differences in health outcomes by racial/ethnic and foreign-born groups, as well as by language preference, future research must examine the use and application of health information at these same levels of influence, through a culturally competent lens.

In order to best serve diverse racial and ethnic minority populations, it will be vital for health care systems, health care providers, and public health professionals to tailor health information resources to strengthen access and use by vulnerable populations. The large magnitude of health care disparities experienced by minority and immigrant populations underscores not only the need for increasing access to culturally competent care, but also a more broad line of research to understand how minorities and immigrants access and use health and health care-related information.

Key messages.

Foreign-born nativity is a significant determinant of health information seeking.

Hispanic foreign-born respondents used the internet the least as a first source for health information.

Adjustment for language differences between racial/ethnic groups suggests that the association between nativity and information source is largely explained by respondent language preference.

This study suggests that certain populations are benefiting from the expanding digital health information age, while others (i.e. non-English speakers) may be subjected to a widening information gap.

Footnotes

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Andersen Ronald M. Revisiting the Behavioral Model and Access to Medical Care: Does It Matter? Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1995;36(1):1–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bach PB, Pham HH, Schrag D, Tate RC, Hargraves JL. Primary Care Physicians Who Treat Blacks and Whites. New England Journal of Medicine. 2004;351(6):575–584. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa040609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britigan Denise H, Murnan Judy, Rojas-Guyler Liliana. A Qualitative Study Examining Latino Functional Health Literacy Levels and Sources of Health Information. Journal of Community Health. 2009;34(3):222–230. doi: 10.1007/s10900-008-9145-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown Anna. U.S. Immigrant Population Projected to Rise, Even as Share Falls among Hispanics, Asians. [Accessed 15 January, 2016];Pew Research Center Fact Tank: News in the Numbers. 2015 http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2015/03/09/u-s-immigrant-population-projected-to-rise-even-as-share-falls-among-hispanics-asians/

- Cantor D, McBride B. Analyzing HINTS 2007: Considering Differences between the Mail and RDD Frames. 2009 http://www.niss.org/sites/default/files/cantor and mcbride, itsew.pdf.

- Clayman Marla L, Manganello Jennifer A, Viswanath K, Hesse Bradford W, Arora Neeraj K. Providing Health Messages to Hispanics/Latinos: Understanding the Importance of Language, Trust in Health Information Sources, and Media Use. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(sup3):252–263. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522697. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose KP, Escarce J, Lurie N. Immigrants and Health Care: Sources of Vulnerability. Health Affairs. 2007;26(5):1258–1268. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.26.5.1258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez Kenneth, Penman-Aguilar Ana, Chang Man-Huei, Moonesinghe Ramal, Castellanos Ted, Rodriguez-Lainz Alfonso, Schieber Richard. Vital Signs: Leading Causes of Death, Prevalence of Diseases and Risk Factors, and Use of Health Services Among Hispanics in the United States – 2009–2013. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2015;64(17):469–478. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in Quality: Addressing Socioeconomic, Racial, and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2579–2584. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.19.2579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flegal KM, Carroll MM, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of Obesity and Trends in the Distribution of Body Mass Index among US Adults, 1999–2010. JAMA. 2012;307(5):491–497. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox Susannah, Duggan M. Mobile Health 2012. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Pew Research Center. 2012 http://community.g.pewinternet.com/~/media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_MobileHealth2012_FINAL.pdf.

- Fox Susannah, Duggan Maeve. Health Online 2013. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Pew Research Center. 2013 http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/PIP_HealthOnline.pdf.

- Fox Susannah, Jones Sydney. The Social Life of Health Information. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Pew Research Center. 2009 http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2011/PIP_Social_Life_of_Health_Info.pdf.

- Huang Zhihuan Jennifer, Yu Stella M, Ledsky Rebecca. Health Status and Health Service Access and Use among Children in U.S. Immigrant Families. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96(4):634–640. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.049791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos E, Blake KD. Predictors of eHealth Usage: Insights on the Digital Divide from the Health Information National Trends Survey 2012. Journal of Medical Internet Research. 2014;16(7):e172. doi: 10.2196/jmir.3117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos Emily Z, Emmons Karen M, Puleo Elaine, Viswanath K. Communication Inequalities and Public Health Implications of Adult Social Networking Site Use in the United States. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(sup3):216–235. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522689. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kontos Emily Z, Emmons Karen M, Puleo Elaine, Viswanath K. Determinants and Beliefs of Health Information Mavens among a Lower-socioeconomic Position and Minority Population. Social Science & Medicine. 2011;73(1):22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.04.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leite L, Buresh M, Rios N, Conley A. Cell Phone Utilization among Foreign-born Latinos: A Promising Tool for Dissemination of Health and HIV Information. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;16(4):661–669. doi: 10.1007/s10903-013-9792-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart Amanda, Purcell Kristen, Smith Aaron, Zickuhr Kathryn. Social Media & Mobile Internet Use Among Teens and Young Adults. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Pew Research Center. 2010 http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2010/PIP_Social_Media_and_Young_Adults_Report_Final_with_toplines.pdf.

- Liu Kirsten Y, Haukoos Jason S, Sasson Comilla. Availability and Quality of Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Information for Spanish-speaking Population on the Internet. Resuscitation. 2014;85(1):131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2013.08.274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Londra Laura C, Tobler Kyle J, Omurtag Kenan R, Donohue Michael B. Spanish Language Content on Reproductive Endocrinology and Infertility Practice Websites. Fertility and Sterility. 2014;102(5):1371–1376. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2014.07.1243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubetkin EI, Zabor EC. Health Literacy, Information Seeking, and Trust in Information in Haitians. American Journal of Health Behavior. 2015;39(3):441. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.39.3.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manganello Jennifer A, Gerstner Gena, Pergolino Kristen, Graham Yvonne, Strogatz David. Media and Technology Use Among Hispanics/Latinos in New York: Implications for Health Communication Programs. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2015;2(3) doi: 10.1007/s40615-015-0169-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mcinnes Nicholas, Haglund Bo JA. Readability of Online Health Information: Implications for Health Literacy. Informatics for Health and Social Care. 2011;36(4):173–189. doi: 10.3109/17538157.2010.542529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narayan KM Venkat, Boyle James P, Thompson Theodore J, Sorensen Stephen W, Williamson David F. Lifetime Risk for Diabetes Mellitus in the United States. JAMA. 2003;290(14):1884–1890. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.14.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GT, Bellamy SL. Cancer Information Seeking Preferences and Experiences: Disparities between Asian Americans and Whites in the Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(sup1):173–180. doi: 10.1080/10810730600639620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen GT, Shungu NP. Cancer-related Information Seeking and Scanning Behavior of Older Vietnamese Immigrants. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(7):754–768. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.514034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega Alexander N, Fang Hai, Perez Victor H, Rizzo John A, Carter-Pokras Olivia, Wallace Steven P, Gelberg Lillian. Health Care Access, Use of Services, and Experiences among Undocumented Mexicans and Other Latinos. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2007;167(21):2354–2360. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.21.2354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peña-Purcell Ninfa. Hispanics’ Use of Internet Health Information: An Exploratory Study. Journal of the Medical Library Association. 2008;96(2):101–107. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.96.2.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez A Susana, Leyva Bryan, Graff Kaitlin, Nelson David E, Huerta Elmer. Seeking Information on Behalf of Others: An Analysis of Calls to a Spanish-language Radio Health Program. Health Promotion Practice. 2015;16(4):501–509. doi: 10.1177/1524839915574246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson A, Allen JA. Effects of Race/ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status on Health Information-seeking, Confidence, and Trust. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved. 2012;23(4):1477–1493. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2012.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzo Lou, Moser Richard P, Waldron William, Wang Zhuoqiao, Davis William W. Analytic Methods to Examine Changes across Years Using HINTS 2003 & 2005 Data. [Accessed 15 January, 2016];NIH Publication. 2008 http://hints.cancer.gov/docs/HINTS_Data_Users_Handbook-2008.pdf.

- Rooks Ronica N, Wiltshire Jacqueline C, Elder Keith, BeLue Rhonda, Gary Lisa C. Health Information Seeking and Use outside of the Medical Encounter: Is It Associated with Race and Ethnicity? Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(2):176–184. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rutten LJF, Squiers L, Hesse B. Cancer-related Information Seeking: Hints from the 2003 Health Information National Trends Survey (HINTS) Journal of Health Communication. 2006;11(sup1):147–156. doi: 10.1080/10810730600637574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selsky C, Luta G, Noone AM. Internet Access and Online Cancer Information Seeking among Latino Immigrants from Safety Net Clinics. Journal of Health Communication. 2013;18(1):58–70. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2012.688248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simone Charles B, Hampshire Margaret K, Vachani Carolyn, Metz James M. The Utilization of Oncology Web-based Resources in Spanish-speaking Internet Users. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012;35(6):520–526. doi: 10.1097/COC.0b013e31821d4906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- The American Association for Public Opinion Research. Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. 9. AAPOR; 2016. http://www.aapor.org/AAPOR_Main/media/publications/Standard-Definitions20169theditionfinal.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Vanderpool Robin C, Kornfeld Julie, Rutten Lila Finney, Squiers Linda. Cancer Information-seeking Experiences: The Implications of Hispanic Ethnicity and Spanish Language. Journal of Cancer Education. 2009;24(2):141–147. doi: 10.1080/08858190902854772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Yu N. Coping with a New Health Culture: Acculturation and Online Health Information Seeking Among Chinese Immigrants in the United States. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2014;17(5):1427–1435. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0106-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei Kwok-Kee, Teo Hock-Hai, Chuan Chan Hock, Tan Bernard CY. Conceptualizing and Testing a Social Cognitive Model of the Digital Divide. Information Systems Research. 2010;22(1):170–187. [Google Scholar]

- Zach Lisl, Dalrymple Prudence W, Rogers Michelle L, Williver-Farr Heather. Assessing Internet Access and Use in a Medically Underserved Population: Implications for Providing Enhanced Health Information Services. Health Information and Libraries Journal. 2012;29(1):61–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2011.00971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X. Cancer Information Disparities Between US-and Foreign-born Populations. Journal of Health Communication. 2010;15(sup3):5–21. doi: 10.1080/10810730.2010.522688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zickuhr Kathryn, Smith Aaron. Digital Differences. [Accessed January 15, 2016];Pew Research Center. 2012 http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2012/PIP_Digital_differences_041312.pdf.