Abstract

Currently for bacterial identification and classification the rrs gene encoding 16S rRNA is used as a reference method for the analysis of strains of the genus Nocardia. However, it does not have enough polymorphism to differentiate them at the species level. This fact makes it necessary to search for molecular targets that can provide better identification. The sodA gene (encoding the enzyme superoxide dismutase) has had good results in identifying species of other Actinomycetes. In this study the sodA gene is proposed for the identification and differentiation at the species level of the genus Nocardia. We used 41 type species of various collections; a 386 bp fragment of the sodA gene was amplified and sequenced, and a phylogenetic analysis was performed comparing the genes rrs (1171 bp), hsp65 (401 bp), secA1 (494 bp), gyrB (1195 bp) and rpoB (401 bp). The sequences were aligned using the Clustal X program. Evolutionary trees according to the neighbour-joining method were created with the programs Phylo_win and MEGA 6. The specific variability of the sodA genus of the genus Nocardia was analysed. A high phylogenetic resolution, significant genetic variability, and specificity and reliability were observed for the differentiation of the isolates at the species level. The polymorphism observed in the sodA gene sequence contains variable regions that allow the discrimination of closely related Nocardia species. The clear specificity, despite its small size, proves to be of great advantage for use in taxonomic studies and clinical diagnosis of the genus Nocardia.

Keywords: hsp65, Nocardia, polymorphism, rrs, sodA

Resumen

Actualmente, para la identificación y clasificación bacteriana se utiliza como método de referencia la secuenciación el gen rrs que codifica al rRNA16S, en el caso del análisis de cepas del género Nocardia, sin embargo, no tiene el suficiente polimorfismo para diferenciarlas a nivel de especie lo que hace necesaria la búsqueda de blancos moleculares que puedan proporcionar una mejor identificación. El gen sodA (que codifica la enzima superóxido dismutasa) ha tenido buenos resultados en la identificación de especies de otros Actinomicetos. En este estudio se propone para la identificación y diferenciación a nivel de especie del género Nocardia. Se utilizaron 41 especies Tipo de diversas colecciones, se amplificó y secuenció un fragmento de 386 pb del gen sodA y se realizó un análisis filogenético comparando los genes rrs (1171 pb) hsp65(401pb) secA1 (494pb), gyrB (1195pb) y rpoB (401pb), las secuencias fueron alineadas utilizando el programa Clustal X, los árboles evolutivos de acuerdo con el método de “Neighbor-Joining”se hicieron con el programa Phylo_win y Mega 6. Se analizó la variabilidad específica del gen sodA del género Nocardia presentando una alta resolución filogenética, una variabilidad genética importante, especificidad y confiabilidad para la diferenciación de los aislados a nivel de especie. El polimorfismo observado en la secuencia del gen sodA contiene regiones variables que posibilitan la discriminación de especies de Nocardia estrechamente relacionadas, y una clara especificidad, a pesar de su pequeño tamaño, demostrando ser de gran ventaja para utilizarse en estudios taxonómicos y en el diagnóstico clínico del género Nocardia.

Mots-clés: Palabras clave, Nocardia, sodA, hsp65, rrs, polimorfismo

Introduction

Actinomycetes are Gram-positive bacteria, soil saprophytes that play an essential role in the processes of humification and decomposition of organic matter, and are also known for their ability to produce metabolites, such as antibiotics, antitumor agents, immunosuppressive agents and enzymes. Apart from their ecologic and industrial role, members of the genus Nocardia are responsible for infections such as nocardiosis and actinomycetoma [1], [2]. Identification of the various species of Nocardia is no longer possible by standard methods such as conventional biochemical tests. Luckily, identification based on molecular tests is every day more promising.

In recent years the sequencing methodology used the rrs gene that encodes the 16S rRNA as a reference method to identify and classify strains of the genus Nocardia at the species level. However, some studies have reported that this gene does not have enough discriminatory power [3] or multiple copies of the rrs gene are present [4]; thus generating problems in the identification of clinical isolates [5].

Other genes have been used as novel genetic targets for the characterization of Nocardia, such as PCR amplification of a segment of the hsp65 gene [6], [7]; the secA1 gene [8]; the gene gyrB [9]; the rpoB and the intergenic spacer 16S-23S, but they can not solve certain identification problems at the species level; nor can they differentiate between species that are closely related and difficult to separate.

The combined use of different genes makes it possible to refine phylogenetic analysis and provide a molecular basis for accurate identification at the species level. However, the use of these genes in a multiple analysis involves the sequencing of each gene for each isolate, which remains laborious and costly for certain diagnostic laboratories [10].

The amplification and sequencing of the sodA gene (gene encoding the enzyme superoxide dismutase) has been used by Zolg and Philippi-Schulz [11] for species-level identification of Mycobacterium strains.

On this basis, we decided to explore the polymorphism of the sodA gene in the genus Nocardia. The objective of this study was to propose a new molecular target that may be useful for the identification and differentiation of clinical and environmental isolates at the species level of the genus Nocardia as well as to evaluate their efficiency.

Materials and Methods

We used 41 strains of the genus Nocardia from international collections, in which the rrs and hsp65 genes absent in GenBank were sequenced. Sequences of the secA1, rpoB and gyrB genes were obtained completely from GenBank. The sodA gene of all strains was sequenced in our laboratory (Table 1).

Table 1.

Accession numbers for six genes of different strains of Nocardia obtained from GenBank

ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CIP, Collection de l’Institut Pasteur; DSM, Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen; JCM, Japan Collection of Microorganisms.

EPV indicates sequences in process of validation in GenBank.

Sequenced by our laboratory.

Methods of DNA extraction

DNA extraction from type strains was performed with the commercial kit UltraClean Microbial DNA isolation kit Mobio, previously reported for bacteria of the order Actinomycetales by Soddell et al. [12]; with the exception of some species such as N. nova, N. anaemiae and N. puris, where the Chelex resin method was used because of problems of concentration and purity of DNA obtained with other methods.

Chelex resin

A bacterial suspension was prepared in an Eppendorf tube containing a dozen 1 mm glass beads and 250 μL of sterile ultrapure water which was homogenized for 5 minutes in a vortex, and 60 μL of Resin Chelex (InstaGene Matrix; 6% w/v Chelex Resin; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) which was previously agitated. The tubes were placed on a heat plate at 100°C for 25 minutes. It was then centrifuged at 10 000g for 5 minutes. Supernatant (200 μL) containing the DNA was taken and transferred to a sterile tube, then frozen at −20°C for storage.

UltraClean Microbial DNA isolation Kit Mobio

A total of 300 μL of the MicroBead solution were added to a MicroBead tube. Once the beads were wetted, the bacterial suspension was added to the tube. Next 50 μL of the MD1 solution was added and the tubes were vortexed at the maximum rate for 10 minutes. The tubes were centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 seconds. The supernatant was then transferred to a tube containing 100 μL of the MD2 solution, vortexed and allowed to incubate at 4°C for 15 minutes, after which the tubes were centrifuged at 10 000g for 1 minute. After this step, 200 μL of the supernatant was transferred to a tube containing 450 μL of the MD3 solution and vortexed for 2 minutes. Immediately 650 μL was transferred to a clean tube with filtration column, centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 seconds, the filtrate discarded and 300 μL of MD4 solution added to the filtration column, which was then centrifuged at 10 000g per 30 seconds. The filtrate column was placed in a 2.0 mL clean microtube, and 35 μL of the MD5 solution was added to the centre of the filter column (where it was allowed to incubate for 5 minutes at room temperature), then centrifuged at 10 000g for 30 seconds. The filtration column was discarded; the DNA was extracted and recovered in the microtube, then stored at −20°C until use.

Amplification and sequencing

Gene rrs (1171 bp)

Sequencing of the rrs gene (16SrRNA) was performed using the following primers: SQ1 (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′), SQ2 (5′-AAACTCAAAGRATTGACGGG-3′), SQ3 (5′-CCCGTCAATYCTTTGAGTTT-3′), SQ4 (5′-CGTGCCAGCAGCCGCG-3′), SQ5 (5′-CGCGGCTGCTGGCACG-3′) and SQ6 (5′-CGGTGTGTACAAGGCCC-3′) (0.2 μM) according to the Sanger method adapted by the DYE terminator sequencing kit (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Sweden). The nucleotide sequences were determined with an automated sequencer ABI 377 (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions by the Biofidal (Vaux-en-Velin, France).

According to the recommendations of Rodríguez-Nava et al. [7]; the sequences were aligned using the Clustal X program [13]. The Phylo_win program [14] and MEGA 6 were used to infer the evolutionary trees according to the neighbour-joining method [15] and Kimura’s two-parameter model [16]. The robustness of the tree was performed with a bootstrap of 1000 replicates.

Gene hsp65 (401 bp)

A fragment of the hsp65 gene encoding the 65 kDa heat shock protein was amplified and sequenced with the following primers: TB11, 5′-ACCAACGATGGTGTGTCCAT-3′ and TB12 5′-CTTGTCGAACCGCATACCCT-3′ (0.6 μM) [17]. The amplification was carried out in Ready-to-Go PCR beads (GE Healthcare UK, Little Chalfont, UK) in a final volume of 25 μL (2.5 U of Taq polymerase, 10 mM Tris-HCl (pH 9) and 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2 and 200 μM of each desoxynucleoside triphosphate) with 10 μL of the DNA extracted by the Chelex method. After initial denaturation at 94°C for 5 minutes, the reaction mixture was run for 35 denaturation cycles at 94°C for 60 seconds, the primers were aligned at 55°C for 60 seconds and the extension was carried out at 72°C for 60 seconds, followed by a postextension extension at 72°C for 5 minutes.

The nucleotide sequence, alignment and analysis of the sequences and the elaboration of the phylogenetic trees were performed under the same conditions described above for the rrs gene.

Gene sodA (386 bp)

A 440 bp fragment of the sodA gene was amplified and sequenced with primers SodV1 (5′-CAC CAY WSC AAG CAC CA-3′) and SodV2 (5′-CCT TAG CGT TCT GGT ACT G-3′) where Y = C or T, W = A or T and S = C or G (0.6 μM) (V. Rodríguez-Nava, personal communication). Amplification was performed using both primers in PCR tubes (illustra puReTaq Ready-to-Go PCR Beads; GE Healthcare Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA) under the same conditions as the rrs gene. Amplification was carried out in a thermocycler (PTC-100; MJ Research, Boston, MA, USA). The amplification run included an initial denaturation step of 5 minutes at 94°C, followed by 35 cycles (94°C for 60 seconds, 55°C for 60 seconds and 72°C for 60 seconds) and a final step of 10 minutes at 72°C. The sequences obtained were verified by DNA sequencing in both directions. The nucleotide sequence, alignment, sequence analysis and elaboration of phylogenetic trees was performed under the same conditions described above for the rrs gene).

Phylogenetic analysis

For the comparative phylogenetic analysis, the sodA gene as well as the rrs (1171 bp), hsp65 (401 bp), secA1 (494 bp), gyrB (1195 bp) and rpoB (401 bp) genes of the 41 Nocardia species studied were used. Several newly described species of the genus Nocardia were not included in this study because they were not available at the time we performed the phylogenetic analysis of the sequences.

Results

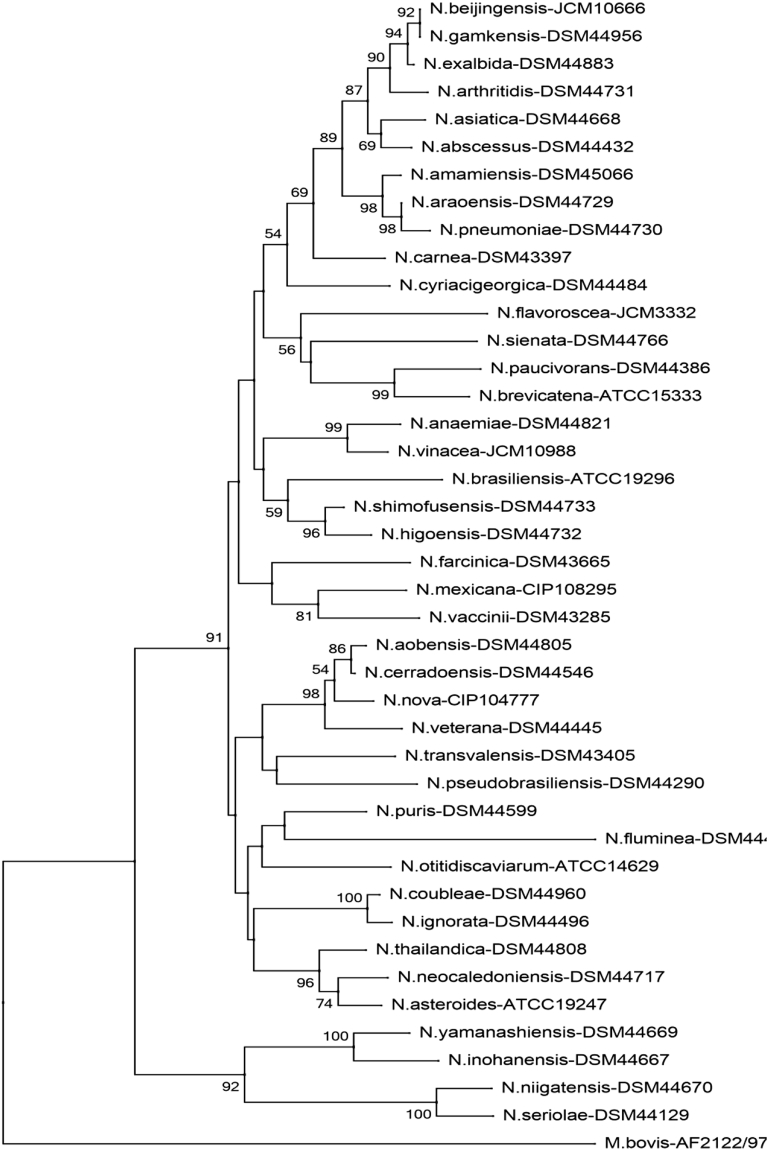

Phylogenetic analysis of sequences of sodA gene of 41 type strains

The sodA gene was successfully amplified in the 41 type species, and phylogenetic analysis of the amplicon sequences showed 15 nodes with bootstrap values of ≥90% representing 38.46%, allowing a robust tree to be constructed. The percentage of minimum similarity found was 79.8% and had a maximum of 100%, which shows a high variability among species. The 386 bp fragment of the sodA gene presented variable regions, with segments of 4 and 5 bp, thus showing an interspecies variability of the sodA gene with the potential to be used as a molecular marker (Table 2).

Table 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of different genes used

| Characteristic | rrs | hsp65 | secA1 | gyrB | rpoB | sodA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylogenetic resolution (%) | 23.07 | 23.68 | 30.7 | 38.48 | 20.51 | 38.48 |

| Gene size (bp) | 1171 | 401 | 494 | 1195 | 401 | 386 |

| Divergence in sequences (bp) | 145 (12.38%) | 114 (28.41%) | 178 (36.03%) | 530 (44.35%) | 151 (37.65%) | 168 (43.52%) |

| Total no. of nodes | 39 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| No. of nodes ≥90% | 9 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 15 |

Polymorphism analysis of different genes

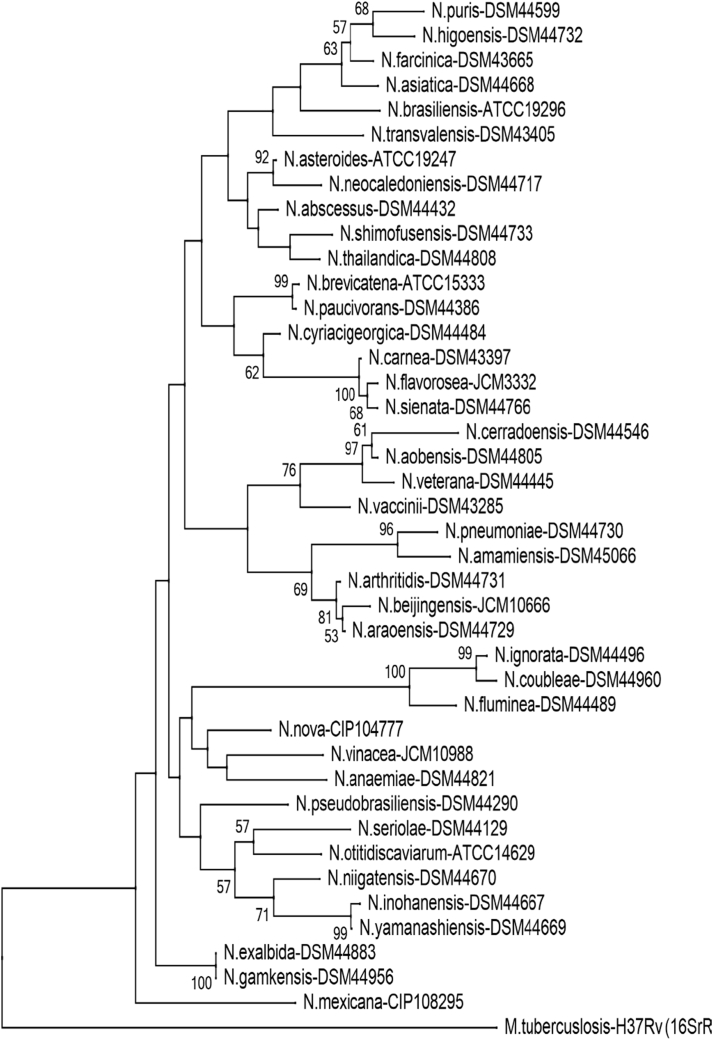

The evolutionary analysis based on distance matrices allowed us to evaluate the interspecies polymorphism for each molecular marker used (rrs, hsp65, secA1, gyrB, rpoB and sodA). We found that the average percentage similarity for the rrs gene was 97.1%, corresponding to 145 nucleotides of difference between species at the interspecies level, whereas for the sodA gene it was 89.9%, corresponding to 168 nucleotides of difference. The variability of substitutions of the sequences of the sodA gene was much greater than those of the rrs gene (Table 2).

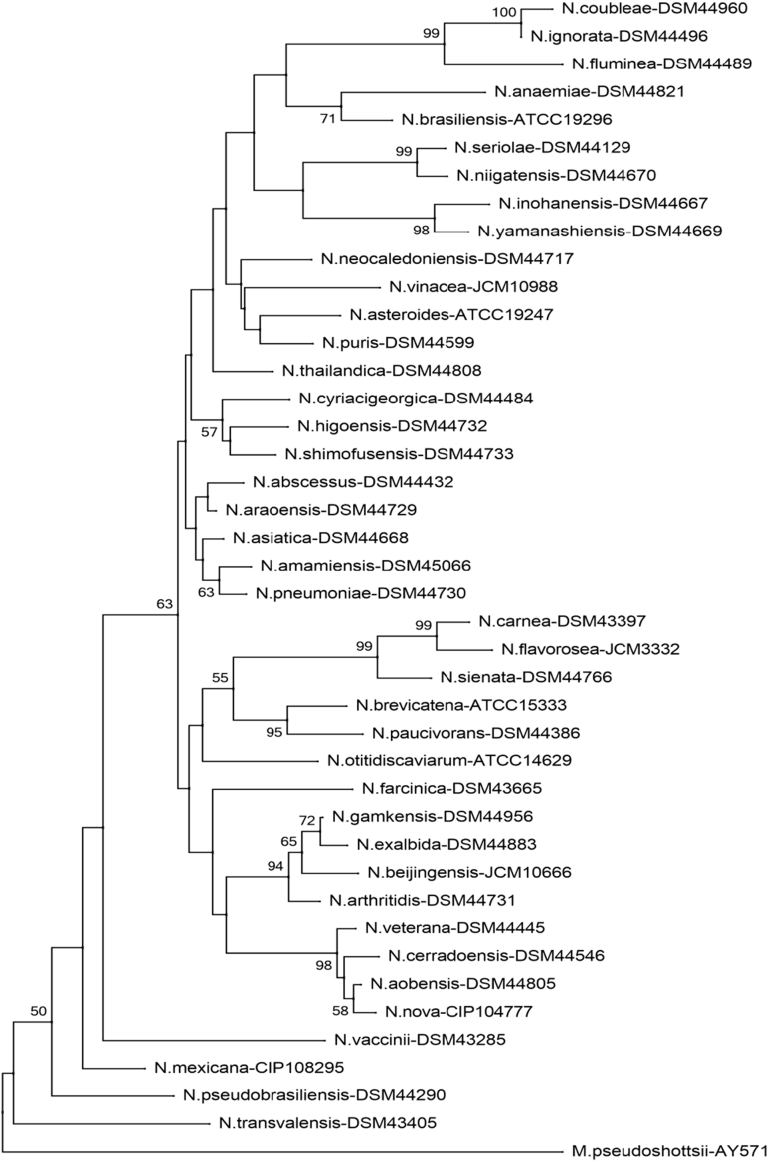

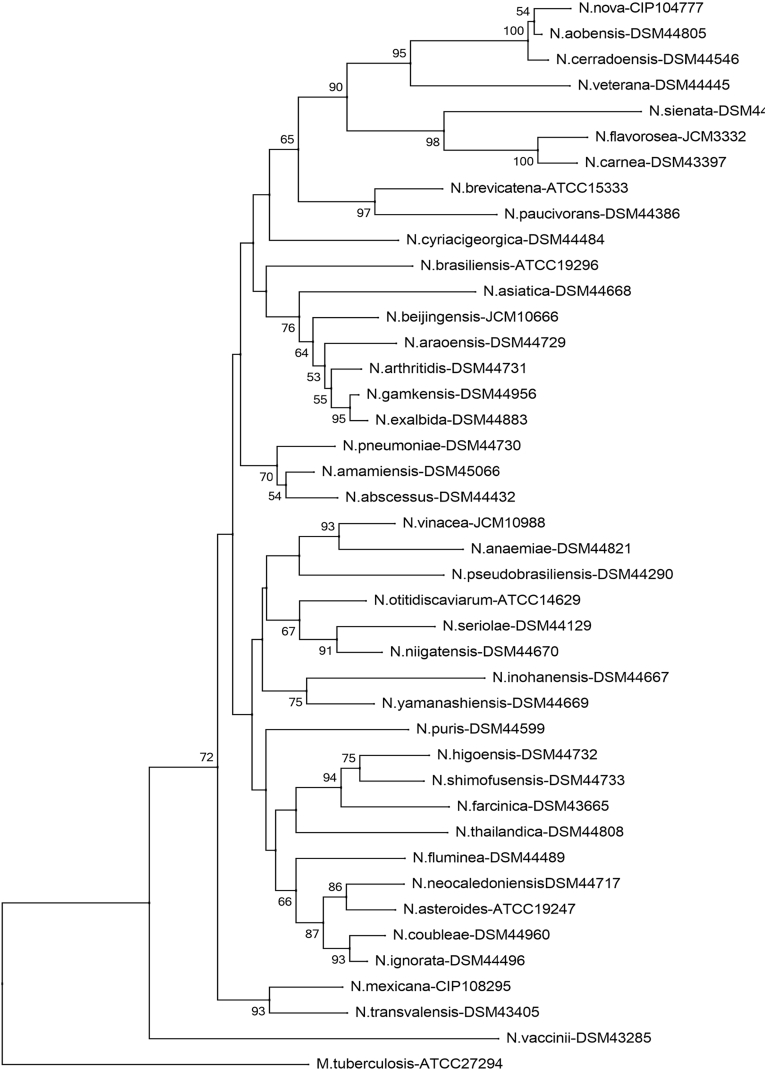

With the analysis of the sequences performed for the sodA gene, 15 nodes (38.48%) were found in the phylogenetic tree (bootstrap values of ≥90%), while for the other genes evaluated, nine nodes (23.07%) were obtained for the rrs gene, nine nodes (23.68%) for hsp65, 12 nodes (30.7%) for secA1 and eight nodes (20.51%) for rpoB; for gyrB, we obtained 15 nodes and a tree robustness of 38.48%.

These results indicate that the sodA gene analysed on a 386 bp fragment compared to the standard rrs identification gene (1171 bp) presents a high resolution and polymorphism as a molecular marker, and presents a variability equivalent to the gyrB gene, with the difference that the gyrB gene corresponds to a bigger fragment of 1195 bp.

As already mentioned, the phylogeny of the genus Nocardia presents certain difficulties, which are reflected in several pairs of species that are hard to differentiate: N. coubleae and N. ignorata; and N. bevicatena and N. paucivorans.

In order to make the phylogenetic analyses more clear and reproducible, all the trees were rooted, as far as possible, with bacteria of the same species. Species of the genus Mycobacterium were used.

Discussion

Sequencing of the rrs gene has been used as the reference method for the identification of Nocardia isolates [18], [19], [20], [21]. However, several studies have revealed the lack of polymorphism of the rrs gene to discriminate between certain closely related species [22]. In our study, the analysis of sequences with the sodA gene revealed an important interspecies polymorphism for the 41 species of Nocardia analysed. It was found that the sequences have a variability of 43.52%, and that contains conserved and other highly variable regions in a small fragment of only 386 bp. It was also observed that it presents the highest phylogenetic resolution (38.48%) compared to the genes already reported, including the reference gene, which presented a lower value (23.07%), except for the gyrB gene, with a resolution of 38.48% but with a large size, resulting in a complex analysis and expensive sequencing.

The phylogenetic distribution found for the Nocardia species obtained with the sodA gene was confirmed by the phylogenetic distribution of the rrs gene, confirming the distribution and position of the associations relative to each species within the tree. The clusters formed between the different species are also present in the other genes (hsp65, secA1, gyrB and rpoB) (Fig. 4, Fig. 5, Fig. 6).

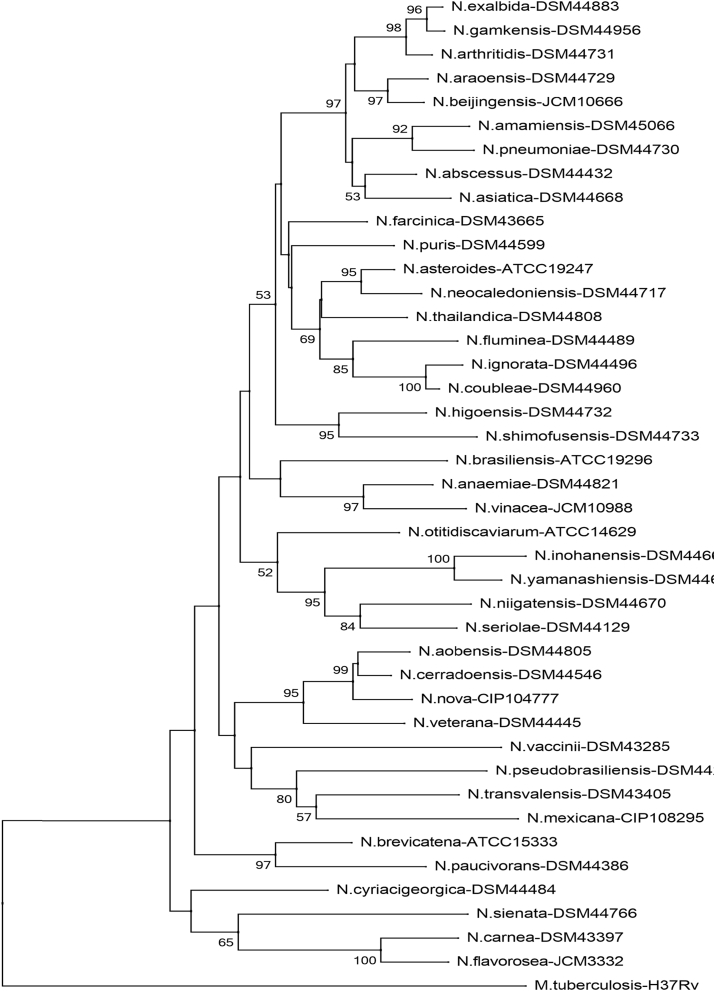

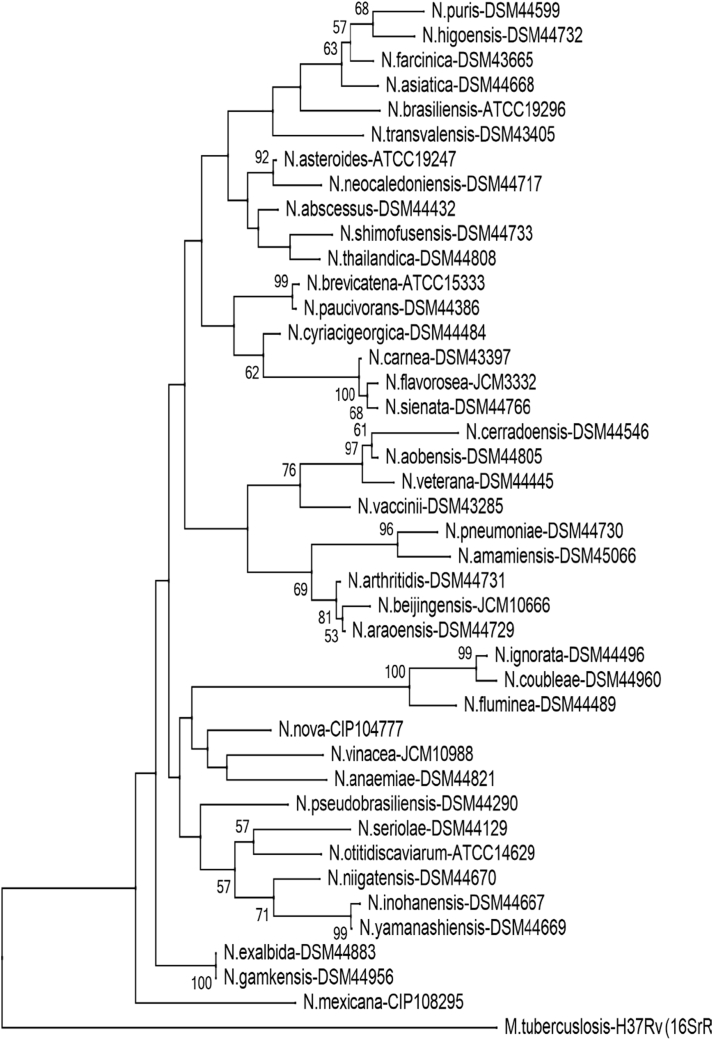

Fig. 1.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (sodA). Phylogenetic distribution of sodA gene (386 bp) of 41 type Nocardia strains analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

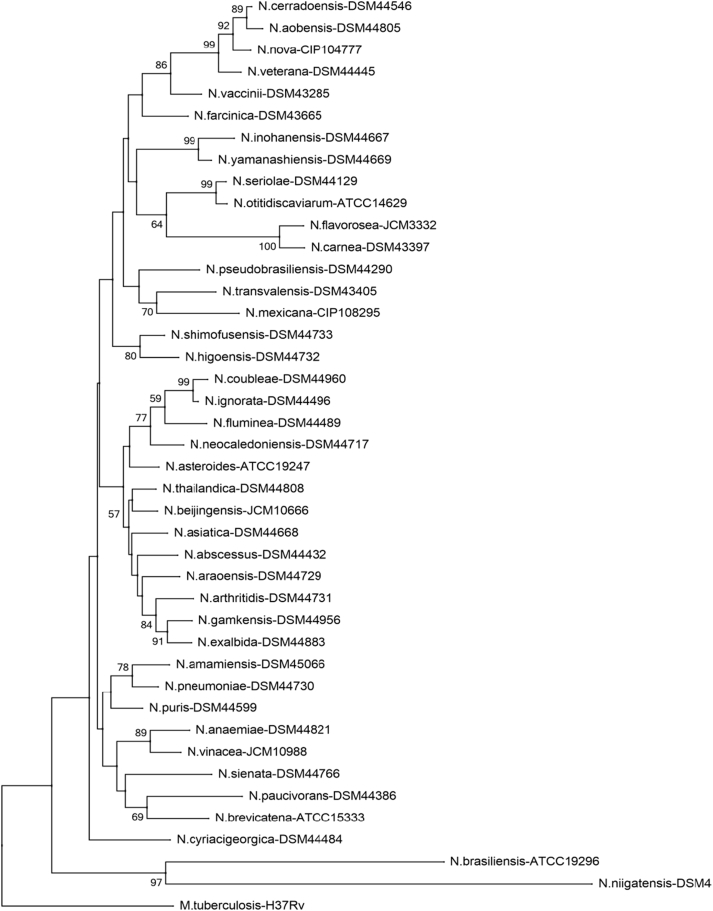

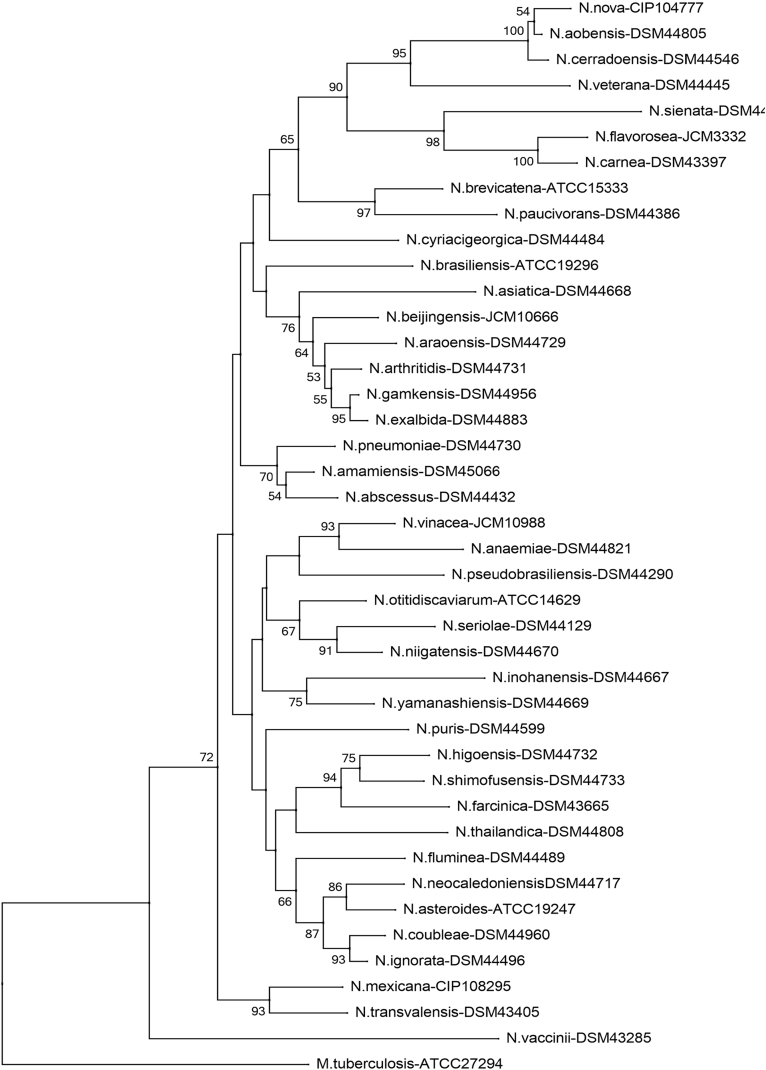

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (hsp65). Phylogenetic distribution of hsp65 gene (401 bp) of 41 Nocardia type strains analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

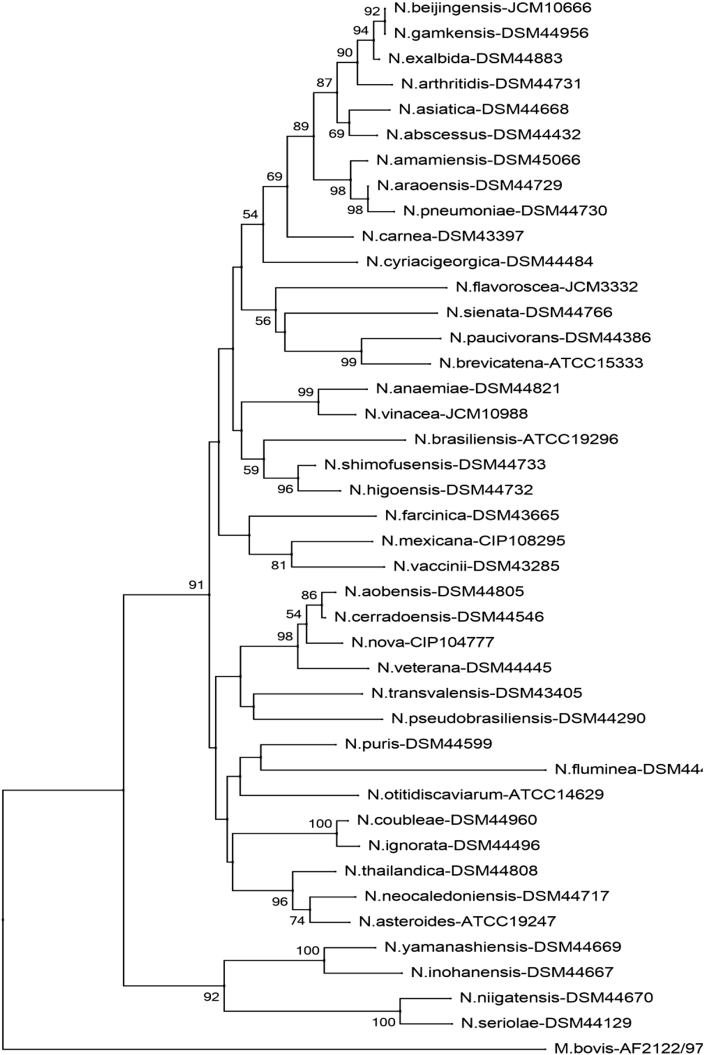

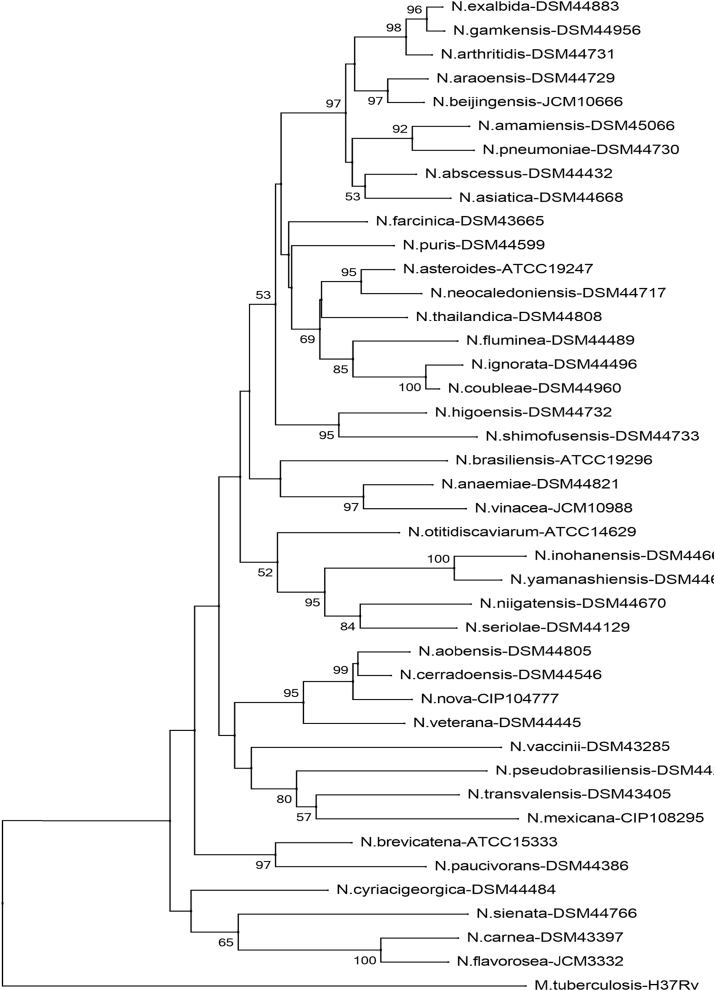

Fig. 3.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (rrs). Phylogenetic distribution of rrs gene (1171 bp) of 41 strains of Nocardia analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

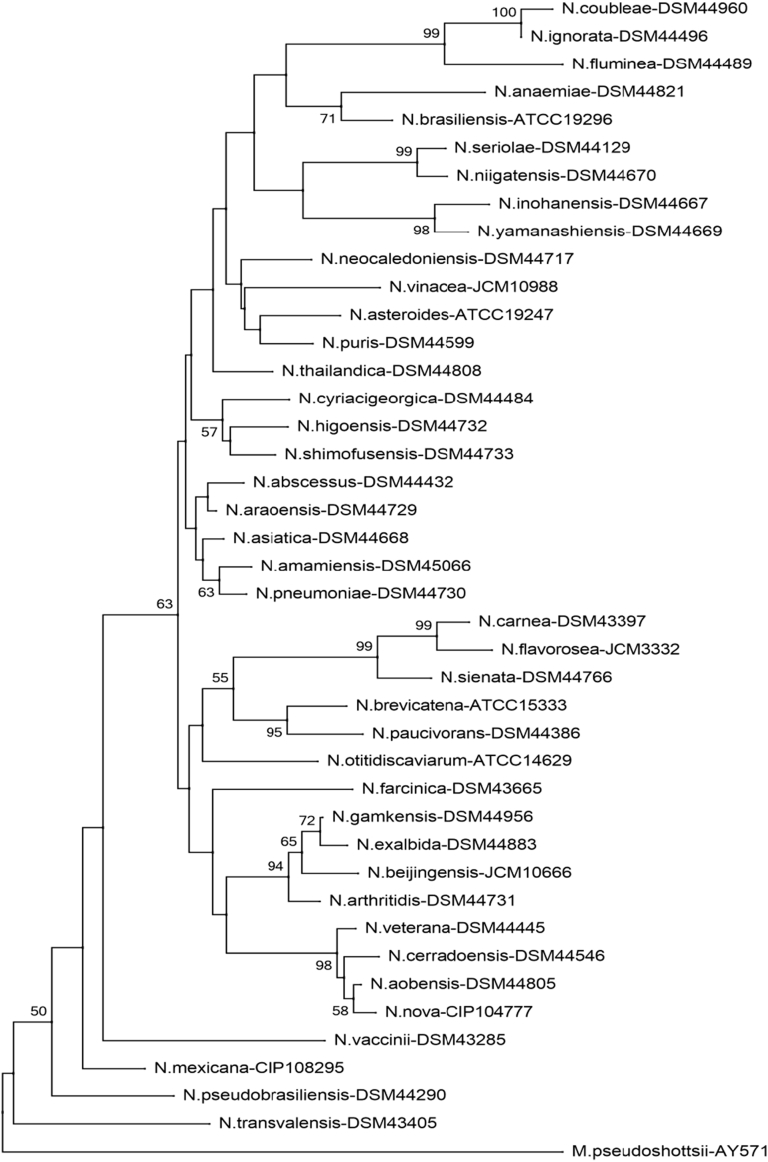

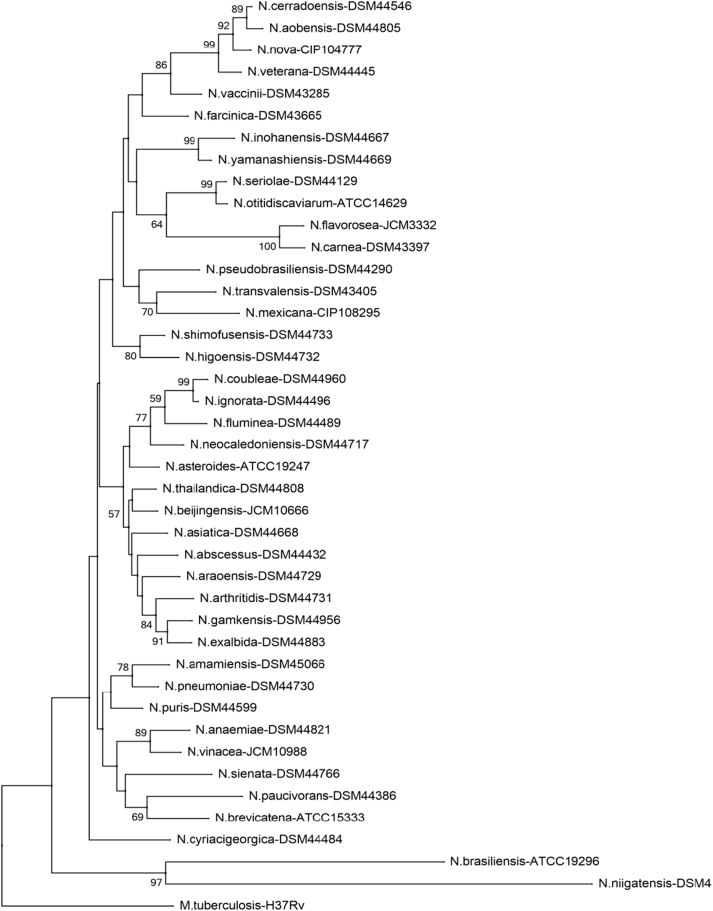

Fig. 4.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (secA1). Phylogenetic distribution of secA1 gene (494 bp) of 41 Nocardia type strains analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

Fig. 5.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (gyrB). Phylogenetic distribution of gyrB gene (1195 bp) of 41 Nocardia type strains analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

Fig. 6.

Phylogenetic tree of Nocardia species (rpoB). Phylogenetic distribution of rpoB gene (401 bp) of 41 strains of Nocardia analysed in this study using neighbour-joining method, Kimura’s two-parameter model and bootstrap of 1000. Only values of bootstrap significance greater than 50% (Clustal X, Phylo_win) were reported.

Conclusions

The specific variability of the sodA gene of the genus Nocardia was analysed. The gene proposed in this work as a molecular genetic marker presented a high phylogenetic resolution, an important genetic variability, and specificity and reliability for the differentiation of isolates at the species level. The polymorphism observed in the sodA gene sequence contains variable regions that enable discrimination of closely related Nocardia species.

We observed a clear specificity of the sodA gene, which we think will prove to be of great advantage for use in taxonomic studies; it could also be used for clinical diagnoses of the genus Nocardia.

Conflict of Interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Deshpande L.M., Fritsche R.N., Jones R.N. Molecular epidemiology of selected multidrug-resistant bacteria: a global report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;4:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodríguez-Nava V., Couble A., Molinard C., Sandoval H., Boiron P., Laurent F. Nocardia mexicana sp. nov., a new pathogen isolated from human mycetomas. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4530–4535. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4530-4535.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yassin F.A., Rainey A.F., Burghardt J., Brzezinka H., Mauch M., Schaal P.K. Nocardia paucivorans sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:803–809. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conville S.P., Witebsky G.F. Multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene in Nocardia nova isolates and implications for sequence-based identification procedures. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2881–2885. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2881-2885.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conville S.P., Witebsky G.F. Analysis of multiple differing copies of the 16S rRNA gene in five clinical isolates and three type strains of Nocardia species and implications for species assignment. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1146–1151. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02482-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Steingrube A.V., Wilson W.R., Brown A.B., Jost C.K., Jr., Blacklock Z., Gibson L.J. Rapid identification of clinically significant species and taxa of aerobic Actinomycetes, including Actinomadura, Gordonia, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces and Tsukamurella isolates, by DNA amplification and restriction endonuclease analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:817–822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.817-822.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rodríguez-Nava V., Couble A., Devulder G., Flandrois J.P., Boiron P., Laurent F. Use of PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis and sequencing dabatase for hsp65 gene-based identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:536–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.536-546.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Conville S.P., Zelazny M.A., Witebsky G.F. Analysis of secA1 gene sequences for identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2760–2766. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00155-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Takeda K., Kang Y., Yazawa K., Gonoi T., Mikami Y. Phylogenetic studies of Nocardia species based on gyrB analyses. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:165–171. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Devulder G., Pérouse de Montclos M., Flandrois P.J. A multigene approach to phylogenetic analysis using the genus Mycobacterium as a model. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:293–302. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zolg J.W., Philippi-Schulz S. The superoxide dismutase gene, a target for detection and identification of mycobacteria by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2801–2812. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2801-2812.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Soddell A.J., Stainsby M.F., Eales L.K., Kroppenstedt M.R., Seviour J.R., Goodfellow M. Millisia brevis gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from activated sludge foam. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:739–744. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J., Clustal W. Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Galtier N., Gouy M., Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Telenti A., Marchesi F., Balz M., Bally F., Bottger E.C., Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson W.R., Steingrube A.V., Brown A.B., Wallace R.J., Jr. Clinical application of PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis for rapid identification of aerobic Actinomycete isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:148–152. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.148-152.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cloud L.J., Conville S.P., Croft A., Harmsen D., Witebsky G.F., Carroll C.K. Evaluation of partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for identification of Nocardia species by using the MicroSeq 500 system with an expanded database. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:578–584. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.578-584.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brown M.J., Pham N.K., McNeil M.M., Lasker A.B. Rapid identification of Nocardia farcinica clinical isolates by a PCR assay targeting a 314-base-pair species-specific DNA fragment. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3655–3660. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3655-3660.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Couble A., Rodríguez-Nava V., Pérouse de Montclos M., Boiron P., Laurent F. Direct detection of Nocardia spp. in clinical samples by a rapid molecular method. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1921–1924. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1921-1924.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roth A., Andrees S., Kroppenste R.M., Harmsen D., Mauch H. Phylogeny of the genus Nocardia based on reassessed 16S rRNA gene sequences reveals underspeciation and division of strains classified as Nocardia asteroides into three established species and two unnamed taxons. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:851–856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.851-856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

References

Introducción

Los actinomicetos son bacterias Gram positivas, saprofitas de suelo que juegan un papel esencial en los procesos de humificación y en la descomposición de la materia orgánica, así como también son conocidos por su capacidad de producir metabolitos, como: antibióticos, agentes antitumorales, agentes inmunosupresores y enzimas. Aparte de su papel ecológico e industrial, se les relaciona con infecciones como la Nocardiosis y el Actinomicetoma, siendo los miembros del género Nocardia los principales responsables [7], [11]. La identificación de las diversas especies de Nocardia ya no es posible por métodos habituales como las pruebas bioquímicas convencionales. Es en este campo, en donde la identificación con base en pruebas moleculares es cada día más promisorio.

En los últimos años se ha empleado la metodología de secuenciación utilizando el gen rrs que codifica al rRNA16S como método de referencia para identificar y clasificar las cepas del género Nocardia a nivel de especie, sin embargo, algunos estudios han reportado que este gen no tiene suficiente polimorfismo para diferenciar entre ciertas especies, por lo que esto puede llevar a identificaciones erróneas, por ejemplo el que dos especies presenten 99.6% de similitud [19] o se presenten múltiples copias del gen rrs [4] generando problemas en la identificación de aislados clínicos [3].

Otros genes han sido utilizados como nuevos blancos genéticos para la caracterización de Nocardia, como la amplificación por PCR, de un segmento del gen hsp65 [12], [16], el gen secA1 [5], el gen gyrB [17], el rpoB y el Espacio de la Región Intergénica 16S-23S (ITS), pero no pueden resolver ciertos problemas de identificación a nivel de especie, ni entre especies estrechamente relacionadas y difíciles de separar.

La utilización combinada de genes diferentes hace posible refinar el análisis filogenético y proporciona una base molecular para la identificación exacta a nivel de especie, no obstante la utilización de estos genes en un análisis múltiple implica la secuenciación de cada gen para cada aislado lo que continua siendo laborioso y costoso para ciertos laboratorios de diagnóstico [8].

La amplificación y secuenciación del gen sodA (gen que codifica la enzima superóxido dismutasa) se ha utilizado por [20] para la identificación a nivel de especie de cepas del género Mycobacterium.

Sobre esta base decidimos explorar el polimorfismo del gen sodA en el género Nocardia. El objetivo de este estudio es proponer un nuevo blanco molecular que pueda ser útil para la identificación y diferenciación de aislados clínicos y ambientales a nivel de especie del género Nocardia así como evaluar su eficiencia.

Materiales Y métodos

Se utilizaron 41 cepas Tipo del género Nocardia de colecciones internacionales, a las cuales fueron secuenciados los genes rrs y hsp65 que no se encontraban en GenBank. Las secuencias de los genes secA1, rpoB y gyrB, fueron obtenidas completamente del GenBank. El gen sodA de todas las cepas fue secuenciado en nuestro laboratorio (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1.

Números de acceso para 6 genes de las diferentes cepas tipo de Nocardia obtenidos del GenBank

| Especie | Números de Acceso |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gen |

||||||||

| Clave | rrs | hsp65 | secA1 | rpoB | gyrB | sodA | ||

| 1 | N. abscessus | DSM 44432T | DQ659895 | AY544983 | DQ360260 | JN215593 | AB447398 | EPV |

| 2 | N. amamiensis | DSM 45066 T | AB275164 | JN041700 | JN041937 | JN215567 | JN041226 | JX519285 |

| 3 | N. anaemiae | DSM 44821 T | JF797304 | JN041769 | JN042006 | JN215636 | AB447400 | KX944462 |

| 4 | N. aobensis | DSM 44805 T | JF797305 | JN041852 | JN042089 | JN215719 | AB447401 | EPV |

| 5 | N. araoensis | DSM 44729 T | JF797306 | AY903637 | EU178745 | DQ085145 | AB450768 | DQ085169 |

| 6 | N. arthritidis | DSM 44731 T | DQ659896 | AY903633 | JN041946 | JN215576 | AB450769 | DQ085166 |

| 7 | N. asiatica | DSM 44668 T | DQ659897 | AY903631 | DQ360263 | JN215591 | AB450770 | DQ085165 |

| 8 | N. asteroides | ATCC 19247 T | DQ659898 | AY756513 | DQ360267 | JN215563 | AB450771 | DQ085146 |

| 9 | N. beijingensis | JCM 10666 T | DQ659901 | AY756515 | JN041942 | JN215572 | AB450772 | DQ085147 |

| 10 | N. brasiliensis | ATCC 19296 T | AF430038 | AY756516 | DQ360269 | JN215639 | AB450773 | DQ085148 |

| 11 | N. brevicatena | ATCC 15333 T | AF430040 | AY756517 | DQ360270 | JN215692 | AB450774 | EPV |

| 12 | N. carnea | DSM 43397 T | AF430035 | AY756518 | DQ360271 | JN215702 | AB450782 | EPV |

| 13 | N. cerradoensis | DSM 44546 T | NR_028704 | AY756519 | JN042082 | JN215712 | AB450777 | EPV |

| 14 | N. coubleae | DSM 44960 T | DQ265689 | DQ250024 | JN041930 | JN215560 | JN041219 | EPV |

| 15 | N. cyriacigeorgica | DSM 44484 T | AF430027 | AY756522 | DQ360272 | JN215664 | AB450784 | EF408035 |

| 16 | N.exalbida | DSM 44883 T | JF797308 | JN041715 | GU584191 | JN215582 | AB447397 | EPV |

| 17 | N. farcinica | DSM 43665 T | AF430033 | AY756523 | DQ360274 | DQ085117 | AB014169 | JX519286 |

| 18 | N. flavorosea | JCM 3332 T | AF430048 | AY756524 | JN042071 | JN215701 | AB450787 | EPV |

| 19 | N. fluminea | DSM 44489 T | AF430053 | AY756525 | JN041926 | JN215556 | AB450788 | DQ085150 |

| 20 | N. gamkensis | DSM 44956 T | DQ235272 | JN041716 | JN041953 | JN215583 | JN041242 | JX519284 |

| 21 | N. higoensis | DSM 44732 T | AB108778 | AY903634 | EU178747 | DQ085142 | AB450789 | DQ085167 |

| 22 | N. ignorata | DSM 44496 T | DQ659907 | AY756526 | JN041928 | JN215558 | AB450790 | DQ085151 |

| 23 | N. inohanensis | DSM 44667 T | AB092560 | AY903625 | DQ360276 | DQ085133 | AB450791 | DQ085159 |

| 24 | N. mexicana | CIP 108295 T | JF797310 | AY903624 | GU584192 | DQ085132 | GQ496104 | EPV |

| 25 | N. neocaledoniensis | DSM 44717 T | AY282603 | AY903628 | JN041932 | JN215562 | AB450795 | DQ085162 |

| 26 | N. niigatensis | DSM 44670 T | DQ659910 | AY903629 | DQ360278 | DQ085137 | AB450796 | DQ085163 |

| 27 | N. nova | CIP 104777 T | AY756555 | AY756527 | DQ360279 | JN215752 | AB450797 | EPV |

| 28 | N. otitidiscaviarum | ATCC 14629 T | AF430067 | AY756528 | DQ360280 | JN215616 | AB450798 | EPV |

| 29 | N. paucivorans | DSM 44386 T | AF179865 | AY756529 | DQ360281 | JN215691 | AB450799 | EPV |

| 30 | N. pneumoniae | DSM 44730 T | JF797313 | AY903636 | EU178749 | JN215569 | AB450801 | EPV |

| 31 | N. pseudobrasiliensis | DSM 44290 T | DQ659914 | AY756530 | DQ360282 | JN215625 | AB450802 | DQ085152 |

| 32 | N. puris | DSM 44599 T | JF797314 | AY903632 | EU178750 | DQ085140 | AB450804 | EPV |

| 33 | N. seriolae | DSM 44129 T | AF430039 | AY756533 | DQ360284 | DQ085125 | AB450805 | DQ085154 |

| 34 | N. shimofusensis | DSM 44733 T | AB108775 | AY903635 | EU178751 | DQ085143 | AB450806 | DQ085168 |

| 35 | N. sienata | DSM 44766 T | NR_024825 | JN041831 | DQ360285 | JN215698 | AB450807 | EPV |

| 36 | N. thailandica | DSM 44808 T | AB126874 | JN041686 | EU178752 | JN215553 | AB450811 | EPV |

| 37 | N. transvalensis | DSM 43405 T | AF430047 | AY756535 | DQ360287 | JN215628 | AB450812 | EPV |

| 38 | N. vaccinii | DSM 43285 T | AF430045 | AY756537 | DQ366276 | DQ085129 | AB450814 | EPV |

| 39 | N. veterana | DSM 44445 T | AF430055 | AY756538 | DQ360288 | JN215706 | AB450816 | EPV |

| 40 | N. vinacea | JCM 10988 T | DQ659919 | AY756539 | DQ360289 | JN215634 | AB450817 | DQ085158 |

| 41 | N. yamanashiensis | DSM 44669 T | AB092561 | AY903630 | DQ360290 | DQ085138 | AB450819 | DQ085164 |

*Todas las claves en “negritas” son cepas secuenciadas por nuestro laboratorio.*EPV: secuencias en proceso de validación en GenBank.

DSM: Deutsche Sammlung von Mikroorganismen, JCM: Japan Collection of Microorganisms; ATCC: American Type Culture Collection; CIP: Collecction de lÍnstitut Pasteur

Métodos de extracción de DNA.

La extracción de DNA de las cepas Tipo se realizó con el kit comercial el UltraCleanTM Microbial DNA Isolation kit Mobio®, reportado previamente para bacterias del orden de los Actinomicetales por [15]; a excepción de algunas especies como N. nova, N. anaemiae y N. puris, donde se utilizó el método con la resina Chelex® debido a problemas de concentración y pureza del DNA, obtenido con otros métodos.

Resina Chelex®.

Se preparó una suspensión bacteriana en un tubo eppendorf que contuviera una decena de perlas de vidrio de 1 mm y 250 μL de agua ultra pura estéril, la cual se homogeneizó durante 5 min en un vortex, se le agregaron 60 μL de la Resina Chelex® (InstaGene™ Matrix, [6% p/v Resina Chelex] BioRad Laboratories) la cual se agitó previamente, los tubos se pusieron en una placa térmica a 100°C por 25 min. Después se centrifugó a 10,000 rpm durante 5 min, se tomaron 200 μL del sobrenadante que contenía el ADN y se transfirieron a un tubo estéril y se congelaron a -20°C para su conservación.

Kit UltraCleanTM Microbial DNA isolation Mobio®

Se agregaron 300 μL de la solución MicroBead a un tubo MicroBead, una vez humectadas las cuentas se adicionó la suspensión bacteriana al tubo, se agregaron 50 μL de la solución MD1, se pusieron los tubos al vortex a una velocidad máxima durante 10 min, los tubos se centrifugaron a 10,000 x g por 30 seg. Posteriormente se transfirió el sobrenadante a un tubo que contenía 100 μL de la solución MD2, se agitó con el vortex, se dejó incubar a 4°C durante 15 min, una vez pasado el tiempo los tubos se centrifugaron a 10,000 x g durante 1 min. Después de esta etapa se transfirieron 200 μL del sobrenadante a un tubo que contenía 450 μL de la solución MD3 y se pasaron por el vortex durante 2 minutos. Enseguida se transfirieron 650 μL a un tubo limpio con columna de filtración, se centrifugaron a 10,000 x g por 30 seg, se descartó el filtrado y se añadieron 300 μL de la solución MD4 a la columna de filtración, se centrifugó a 10,000 x g por 30 seg. Se colocó la columna de filtración en un microtubo limpio de 2.0 mL y se adicionan 35 μL de la solución MD5 en el centro de la columna del filtro (se dejó incubar 5 min a temperatura ambiente) se centrifugó a 10,000 x g por 30 seg. La columna de filtración se desechó, el DNA extraído y recuperado en el microtubo se almacenó a -20°C hasta su uso.

Amplificación y secuenciación

Gen rrs (1171 pb)

La secuenciación del gen rrs (16SrRNA) se efectuó utilizando los “primers”: SQ1 (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′), SQ2 (5′-AAACTCAAAGRATTGACGGG-3′), SQ3 (5′-CCCGTCAATYCTTTGAGTTT-3′), SQ4 (5′-CGTGCCAGCAGCCGCG-3′), SQ5 (5′-CGCGGCTGCTGGCACG-3′) y SQ6 (5′-CGGTGTGTACAAGGCCC-3′) [0.2 μM] según el método de Sanger adaptado por el kit de secuenciación DYE terminador (Amersham Biosciences, Uppsala, Suecia). Las secuencias de nucleótidos se determinaron con un secuenciador automatizado ABI 377 (Foster City, USA) de acuerdo a las instrucciones del fabricante (PE Applied Biosystems) por la empresa BIOFIDAL (Vaux-en-Velin, Francia).

De acuerdo a las recomendaciones de [12]; las secuencias fueron alineadas utilizando el programa Clustal X [21], el programa Phylo_win [9] y Mega 6 se usaron para inferir los árboles evolutivos de acuerdo con el método de “Neighbor-Joining” [14], los algoritmos de Kimura 2 Parámetros [10], la robustez del árbol se realizó con un bootstrap de 1,000 réplicas.

Gen hsp65 (401 pb).

Se amplificó y secuenció un fragmento del gen hsp65 que codifica la proteína de choque térmico de 65-kDa con los “primers” (TB11, 5’-ACCAACGATGGTGTGTCCAT-3’ TB12, 5’-CTTGTCGAACCGCATACCCT-3’) [0.6 μM] [22]. La amplificación se llevó a cabo en tubos de PCR listos para usarse (Ready-to-Go PCR Beads; illustra™ GE Healtcare UK Limited; Amersham Place, Little Chalfont, Buckinghamshire, UK) en un volumen final de 25 μL (2.5 U de Taq polimerasa “pure Taq”, 10 mM de Tris-HCl [pH 9], 50 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 200 μM de cada desoxinucleósido trifosfato) con 10 μL del DNA extraído por medio del método Chelex®. Después de la desnaturalización inicial a 94°C por 5 min, la mezcla de reacción se corrió durante 35 ciclos de desnaturalización a 94°C por 60 s, los “primers” se alinean a 55°C por 60 s, y la extensión de los “primers” se lleva a cabo a 72°C por 60 s, seguido de una extensión de postamplificación a 72 °C por 5 min.

La secuencia de nucleótidos, la alineación y análisis de las secuencias y la elaboración de los árboles filogenéticos se realizó en las mismas condiciones utilizadas para el gen rrs, mencionadas anteriormente.

Gen sodA (386 pb)

Un fragmento de 440 pb del gen sodA se amplificó y secuenció con los “primers” SodV1 (5′-CAC CAY WSC AAG CAC CA-3’) y SodV2 (5′-CCT TAG CGT TCT GGT ACT G-3’) donde Y= C ó T, W = A ó T y S = C ó G [0.6 μM] (Rodríguez-Nava V. Comunicación personal), la amplificación se realizó empleando ambos “primers” en tubos de PCR (illustraTM puReTaq Ready-to-Go PCR Beads; GE Healthcare Bio-sciences, Piscataway, N.J.) en las mismas condiciones que el gen rrs. La amplificación se llevó a cabo en un termociclador (PTC-100; MJ Research, Boston, Mass.). La corrida de amplificación incluyó un paso de desnaturalización inicial de 5 min a 94°C, seguida por 35 ciclos (94°C por 60 s, 55°C por 60 s, y 72°C por 60 s), y un paso final de 10 min a 72°C.

Las secuencias obtenidas fueron verificadas por la secuenciación del DNA en ambos sentidos. La secuencia de nucleótidos, la alineación, análisis de las secuencias y la elaboración de los árboles filogenéticos se realizó en las mismas condiciones utilizadas para el gen rrs, mencionadas anteriormente.

Análisis filogenético.

Para el análisis filogenético comparativo del gen sodA se utilizaron los genes rrs (1171 pb) hsp65 (401 pb) secA1 (494 pb), gyrB (1195 pb) y rpoB (401 pb) de las 41 especies de Nocardia estudiadas. Varias especies recién descritas del género Nocardia no fueron incluidas en este estudio debido a que no estaban disponibles al momento de realizar el análisis filogenético de las secuencias.

Resultados

Análisis filogenético de las secuencias del gen sodA de las 41 cepas Tipo.

Fue amplificado satisfactoriamente el gen sodA de las 41 especies Tipo, el análisis filogenético de las secuencias de los amplicones mostró en el árbol filogenético 15 nodos con “boostraps” mayor o igual a 90% que representan el 38.46% lo que permite construir un árbol robusto. El porcentaje de similitud mínimo encontrado fue de 79.8% y el máximo de 100% lo que demuestra una alta variabilidad entre las especies, el fragmento de 386 pb del gen sodA, presentó regiones variables con segmentos de 4 y 5 pb, lo que muestra una variabilidad interespecie del gen sodA con potencialidad para usarse como marcador molecular. (Tabla 2)

Tabla 2.

“Análisis filogenético de los diferentes genes utilizados”

| Gen | rrs | hsp65 | secA1 | gyrB | rpoB | sodA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resolución filogenética | 23.07% | 23.68% | 30.7% | 38.48% | 20.51% | 38.48% |

| Tamaño del gen | 1171pb | 401pb | 494pb | 1195pb | 401pb | 386pb |

| pb divergentes en las secuencias | 145 (12.38%) | 114 (28.41%) | 178 (36.03%) | 530 (44.35%) | 151 (37.65%) | 168 (43.52%) |

| Nodos totales | 39 | 38 | 39 | 39 | 39 | 39 |

| Nodos ≥90% | 9 | 9 | 12 | 15 | 8 | 15 |

Análisis del polimorfismo para los diferentes genes comparados.

El análisis evolutivo basado en matrices de distancias nos permitió evaluar el polimorfismo interespecie para cada marcador molecular utilizado (rrs, hsp65, secA1, gyrB, rpoB y sodA). Encontramos que el porcentaje de similitud promedio para el gen de rrs fue de 97.1% que corresponde a 145 nucleótidos de diferencia entre las especies a nivel de interespecie, mientras que para el gen sodA fue de 89.9% que corresponden a 168 nucleótidos de diferencia. La variabilidad de sustituciones de las secuencias del gen sodA fue mucho mayor de aquéllas del gen rrs, (Tabla 2).

Con el análisis de las secuencias realizado para el gen sodA se encontraron 15 nodos (38.48%) en el árbol filogenético (bootstraps ≥ 90%), mientras para los demás genes evaluados se obtuvieron 9 nodos (23.07%) para el gen rrs, 9 nodos (23.68%) para el hsp65, 12 nodos (30.7%) para secA1 y 8 nodos (20.51%) para rpoB, y para gyrB, obtuvimos 15 nodos y un porcentaje de robustez del árbol de 38.48%.

Lo que indica que el gen sodA analizado sobre un fragmento de 386 pb comparado con el gen estándar de identificación rrs (1171 pb) presenta una alta resolución y polimorfismo como marcador molecular y presenta una variabilidad equivalente al gen gyrB, con la diferencia que el gen gyrB corresponde a un fragmento de talla superior con 1195 pb.

Como ya fue mencionado la filogenia del género Nocardia presenta ciertas dificultades lo que se ve reflejado en varias parejas de especies que ningún gen pudo definir como son: N.coubleae/N.ignorata, N.bevicatena/N.paucivorans.

Con el objeto de hacer los análisis filogenéticos más claros y reproducibles, todos los árboles fueron enraizados, en la medida de lo posible, con bacterias de la misma especie, por lo que se usaron especies del género Mycobacterium.

Se muestran los árboles filogenéticos de los genes: sodA (Fig. 1), hsp65 (Fig. 2), rrs (Fig. 3), secA1 (Fig. 4), gyrB (Fig. 5) y rpoB (Fig. 6).

Fig 1.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (sodA). Distribución filogenética del gen sodA (386 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win)

Fig 2.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (hsp65). Distribución filogenética del gen hsp65 (401 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win).

Fig 3.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (rrs). Distribución filogenética del gen rrs (1171 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win).

Fig 4.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (secA1). Distribución filogenética del gen secA1 (494 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win)

Fig 5.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (gyrB). Distribución filogenética del gen gyrB (1195 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win)

Fig 6.

Árbol filogenético de especies de Nocardia (rpoB). Distribución filogenética del gen rpoB(401 pb) de las 41 cepas tipo de Nocardia analizadas en este estudio. Usando el método de neighbor-joining, el modelo de dos parámetros de Kimura y un bootstrap de 1000. Se indicaron solo los valores de significancia de bootstrap mayores de 50% (programas: Clustal X, Phylo_win)

Discusión

La secuenciación del gen rrs se ha utilizado como el método de referencia para la identificación de aislados de Nocardia [1], [2], [6], [18] además de su uso en la descripción de nuevas especies. Sin embargo, diversos estudios han revelado la falta de polimorfismo del gen rrs para discriminar entre ciertas especies estrechamente relacionadas [13]. En nuestro estudio el análisis de las secuencias con el gen sodA, reveló un importante polimorfismo interespecie para las 41 especies Tipo de Nocardia analizadas. Se encontró que las secuencias poseen una variabilidad del 43.52%, y que contiene regiones conservadas y otras altamente variables en un pequeño fragmento de tan solo 386 pb, asimismo se observó que presenta la mayor resolución filogenética (38.48%) comparada con los genes ya reportados, e incluso con el gen de referencia que presentó un valor más bajo (23.07%). Excepto por el gen gyrB con resolución de 38.48%, sin embargo su gran tamaño da como resultado un análisis complejo y una secuenciación costosa.

La distribución filogenética encontrada para las especies de Nocardia obtenidas con el gen sodA, se ratifica con la distribución filogenética del gen rrs, en ella se confirman la distribución y las posiciones de las asociaciones relativas a cada especie dentro del árbol. Los “clústeres” formados entre las diversas especies se presentan también con los demás genes (hsp65, secA1, gyrB y rpoB).

Conclusiones

Se analizó la variabilidad específica del gen sodA del género Nocardia y se encontró que:El gen propuesto en este trabajo como marcador molecular genético presentó una alta resolución filogenética, una variabilidad genética importante, especificidad y confiabilidad para la diferenciación de los aislados a nivel de especie.

El polimorfismo observado en la secuencia del gen sodA contiene regiones variables que posibilitan la discriminación de especies de Nocardia estrechamente relacionadas.

Se observó una clara especificidad del gen sodA, demostró ser de gran ventaja para utilizarse en estudios taxonómicos y en estudios posteriores podría usarse para el diagnóstico clínico del género Nocardia

Bibliografía

- 1.Brown M.J., Pham N.K., McNeil M.M., Lasker A.B. Rapid identification of Nocardia farcinica clinical isolates by a PCR assay tarjeting a 314-base-pair species-specific DNA fragment. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:3655–3660. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.8.3655-3660.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cloud L.J., Conville S.P., Croft A., Harmsen D., Witebsky G.F., Carroll C.K. Evaluation of partial 16S ribosomal DNA sequencing for identification of Nocardia species by using the MicroSeq 500 system with an expanded database. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:578–584. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.2.578-584.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Conville S.P., Witebsky G.F. Analysis of multiple differing copies of the 16S rRNA gene in five clinical isolates and three type strains of Nocardia species and implications for species assignment. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:1146–1151. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02482-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Conville S.P., Witebsky G.F. Multiple copies of the 16S rRNA gene in Nocardia nova isolates and implications for sequence-based identification procedures. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:2881–2885. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2881-2885.2005. 132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conville S.P., Zelazny M.A., Witebsky G.F. Analysis of secA1 gene sequences for identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:2760–2766. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00155-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Couble A., Rodríguez-Nava V., Pérouse de Montclos M., Boiron P., Laurent F. Direct detection of Nocardia spp. in clinical samples by a rapid molecular method. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:1921–1924. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.4.1921-1924.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Deshpande L.M., Fritsche, Jones R.N. Molecular epidemiology of selected multidrug-resistant bacteria: a global report from the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance. Program Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2004;4:231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2004.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Devulder G., Pérouse de Montclos M., Flandrois P.J. A multigene approach to phylogenetic analysis using the genus Mycobacterium as a model. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:293–302. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63222-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galtier N., Gouy M., Gautier C. SEAVIEW and PHYLO_WIN: two graphic tools for sequence alignment and molecular phylogeny. Comput Appl Biosci. 1996;12:543–548. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/12.6.543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J Mol Evol. 1980;16:111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rodríguez-Nava V., Couble A., Molinard C., Sandoval H., Boiron P., Laurent F. Nocardia mexicana sp. nov. a new pathogen isolated from human mycetomas. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4530–4535. doi: 10.1128/JCM.42.10.4530-4535.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodríguez-Nava V., Couble A., Devulder G., Flandrois J.-P., Boiron P., Laurent F. Use of PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis and sequencing dabatase for hsp65 gene-based identification of Nocardia species. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44:536–546. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.536-546.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Roth A., Andrees S., Kroppenste R.M., Harmsen D., Mauch H. “Phylogeny of the Genus Nocardia Based on Reassessed 16S rRNA Gene Sequences Reveals Underspeciation and Division of Strains Classified as Nocardia asteroides into Three Established Species and Two Unnamed Taxons”. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:851–856. doi: 10.1128/JCM.41.2.851-856.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saitou N., Nei M. The neighbor-joining method: a new method for reconstructing phylogenetic trees. Mol Biol Evol. 1987;4:406–425. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a040454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soddell A.J., Stainsby M.F., Eales L.K., Kroppenstedt M.R., Seviour J.R., Goodfellow M. Millisia brevis gen. nov., sp. nov., an actinomycete isolated from activated sludge foam. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56:739–744. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.63855-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Steingrube A.V., Wilson W.R., Brown A.B., Jost C.K., Jr., Blacklock Z., Gibson L.J. Rapid identification of clinically significant species and taxa of aerobic Actinomycetes, including Actinomadura, Gordonia, Nocardia, Rhodococcus, Streptomyces and Tsukamurella isolates, by DNA amplification and restriction endonuclease analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:817–822. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.4.817-822.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takeda K., Kang Y., Yazawa K., Gonoi T., Mikami Y. Phylogenetic studies of Nocardia species based on gyrB analyses. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:165–171. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011346-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wilson W.R., Steingrube A.V., Brown AB, Wallace R.J., Jr. Clinical application of PCR-restriction enzyme pattern analysis for rapid identification of aerobic Actinomycete isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:148–152. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.1.148-152.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yassin F.A., Rainey A.F., Burghardt J., Brzezinka H., Mauch M., Schaal P.K. Nocardia paucivorans sp. nov. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2000;50:803–809. doi: 10.1099/00207713-50-2-803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zolg J.W., Philippi-Schulz S. The superoxide dismutase gene, a target for detection and identification of Mycobacteria by PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1994;32:2801–2812. doi: 10.1128/jcm.32.11.2801-2812.1994. 148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thompson J.D., Higgins D.G., Gibson T.J., Clustal W. Improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Telenti A., Marchesi F., Balz M., Bally F., Bottger E.C., Bodmer T. Rapid identification of mycobacteria to the species level by polymerase chain reaction and restriction enzyme analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:175–178. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.175-178.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]