Abstract

This narrative review was conducted to provide an overview of the variety of interventions aimed at disability prevention in community-dwelling frail older persons and to summarize promising elements. The search strategy and selection process found 48 papers that met the inclusion criteria. The 49 interventions described in these 48 papers were categorized into ‘comprehensive geriatric assessment’, ‘physical exercise’, ‘nutrition’, ‘technology’, and ‘other interventions’. There is a large diversity within and between the groups of interventions in terms of content, disciplines involved, duration, intensity, and setting. For 18 of the 49 interventions, significant positive effects for disability were reported for the experimental group. Promising features of interventions seem to be: multidisciplinary and multifactorial, individualized assessment and intervention, case management, long-term follow-up, physical exercise component (for moderate physically frail older persons), and the use of technology. Future intervention studies could combine these elements and consider the addition of new elements.

Keywords: Frail older persons, Disability prevention, Review, Frailty, Activities of daily living

Introduction

Frail older persons people are at much higher risk of disabilities, hospitalization, institutionalization, and death, compared with their age-matched non-frail counterparts (Aminzadeh et al. 2002; Espinoza and Walston 2005; Fried et al. 2004a; Storey and Thomas 2004). In scenarios that predict future health service delivery in the Western world, the rapid increase in frail older persons is seen as one of the major challenges to health care (Hooi and Bergman 2005; Markle-Reid and Browne 2003; Slaets 2006). There has been an exponential rise in the use of the term ‘frailty’ in the literature (Hogan et al. 2003). Markle-Reid and Browne (2003) reported substantial disagreement in the literature as to how frailty is defined and measured. The debate has focused on whether frailty should be defined purely in terms of biomedical factors or whether psychosocial factors should be included as well (Lally and Crome 2007). From their literature reviews, Levers et al. (2006) as well as Aminzadeh et al. (2002) conclude that most definitions of frailty do include the idea of loss of age-related reserve capacity, though differences exist regarding other factors contributing to frailty. Despite a lack of consensus about the definition of frailty, a growing number of intervention studies for frail older persons are reported, implying that interventions can be targeted at frail older persons independent of specific diseases. Disability, defined as experienced difficulty in performing activities in any domain of life (Jette 2006), is generally considered as one of the major adverse outcomes of frailty. Prevention of disability in frail older persons is seen as a priority for research in geriatrics (Ferrucci et al. 2004) and can lead to the maintenance of quality of life and reduced health care costs (Cutler 2001). Several systematic reviews are available, which focus on specific categories of interventions for frail older persons, e.g., comprehensive geriatric assessment (Wieland 2003), after-care (Bours et al. 1998), or respite care (Mason et al. 2007). No overview is available, however, which provides an extensive overview of the content of the full range of existing programmes for community-living frail older persons that are aimed at the prevention of disability. The present study is a narrative review covering a wide range of programmes for community-dwelling frail elderly. The primary aim of the study is to provide an overview of the type of interventions studied in randomized or controlled clinical trials regardless of other aspects of their methodological quality. In order to develop future effective interventions aimed at disability prevention lessons can be learned from such studies. Therefore, the secondary aim of the review is to summarize promising components for future interventions from studies that reported significant effects.

Methods

Search strategy

On March 3, 2008 the databases PubMed, the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and CINAHL were searched for randomised controlled clinical trials by use of the words ‘frail*’, ‘vulnerable’, ‘at risk’, ‘high risk’, ‘low functioning’, and the MESH terms ‘chronic disease’ and ‘disabled persons’ in combination with the MESH term ‘aged’. Search terms for outcomes focused on disability measures and included terms like ‘disabil*’, ‘functional decline’, ‘functional capabilit*’, ‘functional performance’, ‘independen*’, and MESH terms ‘activities of daily living’, ‘quality of life’, and ‘well being’. In order to restrict the search to interventions that targeted community-dwelling older persons, terms like ‘home*’, ‘in-home*’, ‘communit*’, ‘independent living’, and MESH term ‘primary care’ were added. Additionally, studies were identified by a manual search of reference lists from relevant papers. The search was restricted to articles in English, Dutch, and German. There was no restriction on type of intervention or year of publication.

Selection criteria

Inclusion criteria were set for study population, outcome measure, and design. Randomised and controlled clinical trials specifically aimed at community-dwelling frail older persons were included. No restrictions were set concerning the definition of frailty. As frailty points to an increased risk of adverse outcomes, only studies that specified the criteria used to operationalise the increased risk were included. Studies that used physical markers to include participants were included as well as studies that used a combination of factors (multifactorial perspective on frailty) as inclusion criteria. Exclusion criteria for the population concerned the selection of participants solely based on age, age and fall incidents, and age and having one chronic disease.

Disability was used as the outcome measure (regardless of whether it was used as a primary or secondary outcome) and defined as difficulty experienced in performing activities (Jette 2006). Avlund (2004) found that most current studies of disability among older persons focus on the ability to carry out activities of daily living. In this review, studies reporting measurements of Activities of Daily Living (ADL) or Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) were included.

Data extraction and analysis

A first selection of relevant studies was made by RD on title-level with a conservative approach, meaning that in case of doubt an article would always be screened on abstract-level. The second (abstract-level) and third selection phases (full-text level) were independently undertaken by two reviewers (RD and SM) scoring ‘relevant’, ‘doubt’, or ‘irrelevant’ on forms. In case of inconsistencies, the reviewers discussed their scores. Consensus on ‘irrelevant’ led to the exclusion of an article. On several occasions, the reviewers asked for the involvement of a third party (EvR) to reach consensus.

The same two reviewers performed the data extraction with respect to aims, target population, design, care disciplines involved, and content of the interventions. Furthermore, follow-up and reported effectiveness on disability were retrieved from the articles. Assessment of the methodological quality of studies was not performed, as the primary aim was to provide an overview of the type of interventions reported for community-dwelling frail older persons. The research team (RD, SM, EvR, LdW, WvdH) discussed ways of categorizing the studies based on descriptions common in geriatric literature. As this review intends to provide an overview of the content of interventions, it was decided to categorize the interventions according to their intervention characteristics. Interventions were classified into ‘comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)’, ‘physical exercise’, ‘nutrition’, ‘assistive technology’, and ‘other interventions’. Studies that reported significant effects in favor of the experimental group on ADL or IADL measures were further explored (by RD and SM) to identify intervention elements that might explain successful outcomes.

Results

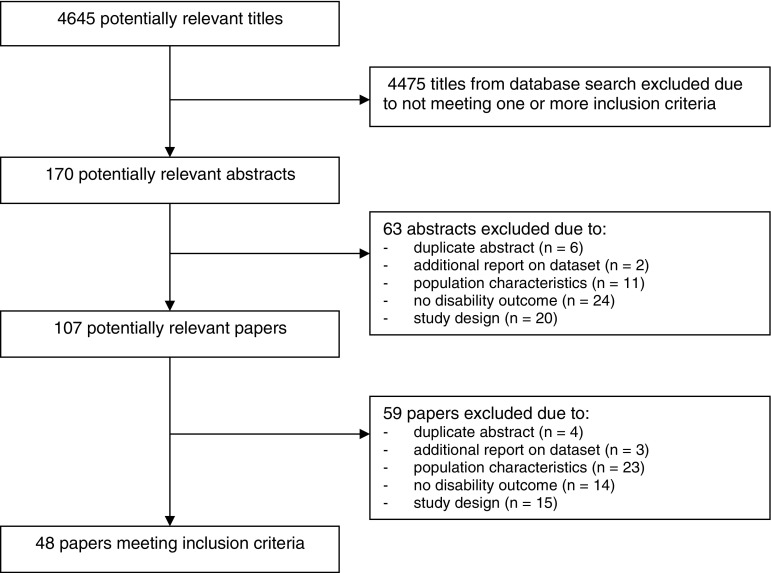

Four thousand, six hundred and forty-five articles were identified in the literature search. After screening of the titles, 170 studies were considered relevant for further screening on abstract-level. Of these, another 63 studies were excluded, because they did not meet the inclusion criteria (Fig. 1). In the next phase, the screening of 107 full-text articles resulted in the exclusion of 59 studies. Of these, 21 were excluded as they did not meet the criteria for population characteristics; 14 did not meet the criteria for the outcome measure (disability), and 14 failed owing to study design. Forty-eight studies, describing 49 interventions, were included. Among these, 26 interventions were categorized as ‘comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA)’, 12 as ‘physical exercise’, 3 as ‘nutrition’, 2 as ‘assistive technology’, and 6 were classified as ‘other interventions’. All studies were published between 1986 and 2008. There is a large variation in the criteria that studies used to include frail older persons (see Table 1). Physical frailty markers are more common as inclusion criteria in physical exercise programs, while more complex interventions (CGA) generally use a combination of factors, taking a multifactorial perspective on frailty. All 48 studies met the inclusion criterion to measure disability by using measurements on ADL or IADL. However, disability was not the primary outcome measure for all studies. Eleven studies did perform a long-term follow-up measurement (≥6 months after the end of the intervention). For nine studies information on follow-up was lacking.

Fig. 1.

Progress of search for relevant trials

Table 1.

Intervention characteristics

| Study | Participants inclusion criteria | Interventions | Disability outcomes* |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGA: Transmural care | |||

| Burns et al. (1995) USA RCT (N = 128) |

Aged ≥ 65; at least two of following criteria: ADL deficits, two or more chronic diseases, polypharmacy, two or more hospitalizations in the previous year | Initial assessment of functional limitations, gait, incontinence, polypharmacy, depression and cognitive impairment in outpatient geriatric clinic by interdisciplinary primary care team (physician, nurse practitioner, social worker, psychologist and pharmacist), followed by long-term management (2 years) with individualized goals, interventions, treatment and follow-up | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale: Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 12, 24 months. Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale: Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 12 months. No differences between groups at 24 months |

| Hughes et al. (1990) USA RCT (N = 233) |

Two or more impairments based on the Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale | Hospital-based home care program directed by a physician. Approximately 6 home visits by primary care team (physician, nurse, social worker, physical therapist, occupational therapist, dietician, health technician). Medications and supplies from the hospital pharmacy | Barthel ADL Index: No significant differences between groups at 1, 6 months (after discharge) |

| McCusker et al. (2001) RCT Canada (N = 388) |

Aged ≥ 65; score of 2 or more on the Identification of Seniors at Risk Screening Tool | Evaluation by nurse (physical and mental function, medical status and social factors) followed by an interdisciplinary team meeting. After discharge referrals to primary physician, local community health centre, outpatient clinic and other community services. Follow-up visits by nurse to ensure execution of appointments and services | Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (ADL and IADL scale): Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 4 months |

| Naylor et al. (1999) USA RCT (N = 363) |

Aged ≥ 65; medical diagnose AND at least 1 of several criteria, e.g., inadequate support system, depression, impairments, hospitalization, poor self-rating of health | Comprehensive discharge planning and home follow-up (till 4 weeks after discharge). Advanced nurse practitioner did a physical and environmental assessment and targeted efforts at patient’s and caregivers’ management of health problems. Interventions (home visits and telephone follow-up) focused on medications, symptom management, diet, activity, sleep, medical follow-up and emotional status | Enforced Social Dependency Scale: No significant differences between groups at 2, 6, 12, 24 weeks (after discharge) |

| Oktay and Volland (1990) USA CCT (N = 191) |

Aged ≥ 65; chronic post-hospital care needs | Assessment by nurse and social worker. After discharge followed home visits (on average 4 home visits per month during 1 year). Nurse and social worker (supported by weekly staff meetings) provided a coordinated program including case management, counseling, referrals, respite, education, support group sessions, medical back-up and on-call help. Strong focus on caregiver/patient configuration | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale/3 items of Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale: No significant differences between groups at 1, 3, 6, 9, 12 months (after discharge) |

| Rubin et al. (1993) RCT USA (N = 194) |

Aged ≥ 70; at high risk of hospital readmission for inpatient treatment to stabilize acute episodes of chronic illness | Geriatric Assessment Team (internist, psychiatrist, nurse, social worker) did assessment, developed plan for long-term care and directed discharge planning (including referrals for home health services). In the outpatient period comprehensive interdisciplinary care was provided on an ongoing base in the clinic | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale: No significant differences between groups at 12 months (after discharge). Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (ADL and IADL scale): Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 12 months (after discharge) |

| Siu et al. (1996) USA RCT (N = 354) |

Aged ≥ 65; unstable medical problems OR recent functional limitations OR potentially reversible geriatric clinical problems | At hospital nurse practitioner (NP) carried out a physical examination focused on geriatric problems. Multidisciplinary team meeting was followed by recommendations to the primary care physician (strong focus on physician’s adherence with these recommendations). A home visit was made by NP within 1–3 days after discharge. Three home visits followed by the NP and other team members | Medical Outcome Study Short Form: No significant differences between groups at 1, 2 months (after discharge) |

| CGA: Assessment followed by referrals and recommendations | |||

| Hebert et al. (2001) Canada RCT (N = 503) |

Aged ≥ 75; identified at risk by Sherbrooke postal questionnaire | Home visit by nurse to assess problems with medication, mood, cognition, vision, hearing, blood pressure, gait and balance, orthostatic hypotension, environmental risk of fall, malnutrition, incontinence and social support. Recommendations were sent to general practitioner and referrals were made to specialized resources. Nurse contacted monthly clients to check the implementation | Functional Autonomy Measurement System: No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| Reuben et al. (1999) USA RCT (N = 363) |

Aged ≥ 65: failed a screen for at least one condition: falls, incontinence, depressive symptoms, functional impairment | Assessment done by social worker, geriatric nurse practitioner/geriatrician team at community-based clinic, followed by team meeting resulting in written recommendations for the patient and the primary physician. Telephone contact with the primary physician. A booklet (how to talk to your doctor) was given to patient. Telephone contacts with a health educator were applied to enhance adherence | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning scale): Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 15 months |

| Robichaud et al. (2000) Canada RCT (N = 99) |

Aged ≥ 75; identified at risk by Sherbrooke postal questionnaire | Home visit by nurse to assess problems with medication, mood, cognition, vision, hearing, blood pressure, gait and balance, orthostatic hypotension, environmental risk of fall, malnutrition, incontinence and social support. Results and information sheet (summarizing suggested interventions) were send to general practitioner. Nurse conducted bimonthly telephone interviews for follow-up | Functional Autonomy Measurement System: Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 10 months |

| Silverman et al. (1995) USA RCT (N = 442) |

Aged ≥ 65; instability in health status in previous 6 months (one or more specific risk indicators, e.g., difficulty walking, falls, incontinence, loss of vision or hearing) | Hospital geriatric team (internist, nurse, social worker) provided a comprehensive outpatient evaluation (medical, psychological and social health problems) and treatment plan. Findings and treatment plan were discussed with the patient and the family. Recommendations were communicated to referring physicians | Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (ADL and IADL scale)/Barthel ADL Index: No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| CGA: Assessment followed by treatment and care | |||

| Bernabei et al. (1998) Italy RCT (N = 200) |

Aged ≥ 65; already receiving community care services or home assistant programs, mostly because of multiple geriatric conditions | Case-manager performed initial assessment and reported findings to geriatric evaluation unit that designed and implemented individualized care plan in agreement with general practitioner. Weekly team meetings to discuss problems emerging from home visits. Re-assessment every 2 months. Team is constantly available to deal with problems, to monitor the provision of services and to guarantee extra help as requested | 6-item scale of daily living/7-item scale of instrumental activities of daily living (name not specified): Differences (SS) in favor of the IG at 12 months |

| Boult et al. (2001) USA RCT (N = 568) |

Aged ≥ 70; at risk for hospitalization and functional decline: ore likely to use hospitals, nursing homes, home care, emergency rooms and medication | 4-steps assessment: General practitioner, home visit by social worker, 2 visits at GEM clinic (general nurse practitioner, geriatrician, nurse). Team meeting led to care plan, delivered by team (medication, regimes, counseling, health education, advance directives, referrals). Hospital care and 24-hours on-call service. Monthly meeting and phone calls (on average for 6 months) to monitor and coordinate care plan. Recommendation for period after discharge was given to general practitioner | Sickness Impact Profile (physical functioning dimension): Differences (SS) in favor of the IG at 6, 12, and 18 months |

| Cohen et al. (2002) USA RCT (N = 1,388) |

Aged ≥ 65; hospitalization; ≥2 frailty criteria: e.g., falls, limitations in BADL or walking, dementia, depression, stroke, bed rest, incontinence, malnutrition | Inpatient and outpatient intervention teams (geriatrician, social worker, nurse) assessed functional, cognitive, affective and nutritional status, caregiver’s capabilities and social situation; team meetings (twice a week) to evaluate and discuss treatment plan with regard to preventive and management services (dietetics, physical and occupational therapy, clinical pharmacy) | Physical Performance Test/Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale: Differences (SS) in favor of inpatient IG in comparison with CG at discharge. No significant differences between groups at 12 months. No significant differences at discharge and at 12 months for the outpatient IG in comparison with CG |

| Gagnon et al. (1999) Canada RCT (N = 427) |

Aged ≥ 70; discharge from hospital previous 12 months at risk for repeated admission (≥40%), assistance with ≥1 ADL OR ≥2 IADL | Nurse assessed health, physical, functional, social, environmental aspects, community services, needs and concerns of older people and caregivers, created and implemented care plan and coordinated professionals. Weekly interdisciplinary case conference. Collaboration with emergency department and community health centre (24-h available). Monthly call, home visits every 6 weeks (10-month period) follow-up by telephone | Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire/Medical Outcome Study Short Form: No significant differences between groups at 10 months |

| Gitlin et al. (2006) USA RCT (N = 319) |

Aged ≥ 70; functional vulnerable defined as needing help with ≥2 IADL OR ≥ 1 ADL OR ≥ 1 falls (last 1 year) | Interviews and observations to assess problem areas. During 6 months physiotherapist provided 1 visit (90 min) consisting of balance, muscle strength, safe fall, recovery training. Occupational therapist provided 4 visits (90 min) for problem solving, use of control-oriented strategies (environmental modifications, behavioral/cognitive strategies). Installation of home modifications. 3 phone contacts (20 min) to reinforce strategy use and to generalize strategies to new problems | ADL index, IADL index (name not specified): Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 6 months. Mobility/transfer index: Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 6 months. ADL index, IADL index, mobility/transfer index: No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| Landi et al. (2001) Italy RCT (N = 187) |

Eligible for home care services: older disabled persons | Case-manager assessed function, health, social support, and service use every 3 months (1 year period) by using Minimum Data Set for Home Care that provided guidelines for further assessment and care (client-oriented assessment protocols). Collaboration with community geriatric evaluation unit and general practitioner led to individualized care plan. Case-manager coordinated and integrated care that is delivered by multidisciplinary tem | Bartel ADL Index/Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 12 months |

| Markle-Reid et al. (2006) Canada RCT (N = 288) |

Aged ≥ 75; referral to personal support services; a model of vulnerability is used to define frailty | Nurse regularly assessed risk factors for functional decline and provided health education regarding lifestyle and management of chronic diseases (telephone calls and home visits during 6 months). A participatory approach, involving empowerment, was used to promote positive attitudes, knowledge and skills. Focus on environmental support, referral and coordination of community services (goals-led health plan) | Medical Outcome Study Short Form: Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 6 months |

| Melin and Bygren (1992) Sweden RCT (N = 249) |

Discharge from hospital (internal medicine, orthopedics); chronically ill and dependent in 1–5 functions of personal ADL according to Katz activities of Daily Living Scale | Assessment of medical and functional status by nurse/home service (phone calls) and physician (home visit) to develop treatment plan. Weekly interdisciplinary team meetings (nurse, home service assistant, geriatrician, psychiatrist). 24 h telephone service. Emergency and routine home visits whenever needed (by nurse, assistant nurse, home aids), also in the weekend (by physician, is always accessible for primary care staff by phone) | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale: No significant differences between groups at 6 months. IADL modified Katz index: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 6 months |

| Melis et al. (2008) The Netherlands RCT (N = 151) |

Aged ≥ 70; living at home or in retirement home; limitations in cognition (Mini Mental State Examination) (I)ADL (Groningen Activity Restriction Scale), or mental health (Medical Outcome Study Short Form) | Home visits by nurse for evaluation and management (max. 6 visits during 3-month period). Multidimensional assessment (cognition, nutrition, behavior, mood, mobility), coordination of care, therapeutic monitoring, case management (individualized and integrated treatment plan, including advices and psycho education). Collaboration with primary care physician, other health professionals and caregivers | Groningen Activity Restriction Scale-3: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 3 months. Slightly smaller differences (NS) in favor of IG at 6 months |

| Phelan et al. (2004) USA RCT (N = 201) |

Aged ≥ 70 AND one more chronic condition; difficulties with ADL but no human help is needed, ability to walk, non-participation in senior centre | General nurse practitioner assessed health and risk factors (self-management of chronic diseases, psychoactive medication, physical activity, depression, social isolation) and developed in collaboration with general practitioner tailor-made health action plan. Senior centre-based, self-management class, peer support, and exercise class (or exercise program at home). Follow-up until 12 months (on average 3 visits and 9 telephone calls) | Health Assessment Questionnaire Disability Index: Incident disability: No significant differences between groups at 6 months. Small differences (NS) in favor of IG at 12 months; Disability improvement: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 6, 12 months; Disability worsening: Small differences (NS) at 6 months, modest differences (NS) at 12 months in favor of IG |

| Rockwood et al. (2000) Canada RCT (N = 182) |

At least one criteria, e.g., concern about community living, acute illness, frequent physician contact, multiple medical problems, functional decline | Geriatrician nurse assessed mental and emotional status, communication, mobility, balance, bowels, bladders, nutrition, daily activities, and social situation. Geriatrician used Goal Attainment Scaling to set goals, finalizing in multidisciplinary conference. Mobile Geriatric Assessment Team (nurse, geriatrician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist, social worker, dietician, audiologist, speech-language pathologist) implemented recommendations. 3 interdisciplinary consults during 3 months period | Barthel ADL Index/Instrumental activities of daily living scale (name not specified): No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| Rubenstein et al. (2007) USA RCT (N = 792) |

Aged ≥ 65; clinical visit previous 18 months; ≥4 positive responses on Geriatric Postal Screening Survey | Case-manager (physician assistant) assessed geriatric target conditions and other health problems. Additional assessment in geriatric clinic (in general 1 visit). Team meeting led to care plan given to primary care provider. Case-manager referred and gave recommendations (health promotion). Telephone follow-up by case-manager every 3 months during 3 years | Functional Status Questionnaire (ADL and IADL scale): No significant differences between groups at 1, 2, 3 years. Differences (NS) between subgroups at 12 months |

| Toseland et al./Engelhardt et al. (1997/1996) USA RCT (N = 160) |

Aged between 55–75 AND ≥ 1 ADL or ≥ 2 IADL impairments; >75 AND any combination of 2 ADL or IADL impairments | Team (nurse practitioner, geriatrician, social worker) participated in assessment, development and implementation of care plan, follow-up and re-assessment, monitoring and revision of care plan, referral to and coordination with health and social services. Advices for hospitalization, discharge planning. Weekly team meetings. Routine follow-up and walk-in care | Functional Independence Measure: No significant differences between groups at 8 and 16 months |

| Williams et al. (1987) USA RCT (N = 117) |

Aged ≥ 65; medical evaluation (last year), decline in functional ability and unmet needs, unstable medical problems; polypharmacy; dissatisfaction with care | Multidisciplinary team (internist, physician, psychiatrist, nurse, social worker, nutritionist) assessed physical, mental, social functioning and resulted in a problem list and team goals. Team provided counseling and family support. Follow-up visits were scheduled, among which home visits if requested | Interviews (name not specified)/Patient Assessment Forms: small non-significant differences in favor of the IG at 8 months. No information provided at 12 months |

| Physical exercise | |||

| Binder et al. (2002) USA RCT (N = 119) |

Aged ≥ 78; 2 out of 3 criteria: score between 18–32 on Modified Physical Performance Test, peak oxygen uptake between 10 and 18 mL/kg/min, self-reported difficulty in max. 2 ADLs or 1 IADL | 9 month program provided by physiology exercise technicians consisting of three phases of each 36 sessions. Phase 1: Group format: 22 exercises on flexibility, balance, coordination, speed of reaction and strength. Phase 2: Progressive resistance training and shortened version of phase 1 exercises. Phase 3: Endurance training and shortened version of phase 1 and phase 2 exercises | Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (ADL and IADL scale): No differences between group at 3, 6 and 9 months. Functional Status Questionnaire (physical function subscale): Difference (SS) in favor of IG at 6 and 9 months |

| Boshuizen et al. (2005) The Netherlands RCT (N = 72) |

Experiencing difficulty in rising from chair AND maximum knee-extensor torque < 87.5 N-m | 10 week exercise program, each week two group sessions (60 min) by physiotherapist and one unsupervised home session. Focus on exercises with a variation in concentric, isometric and eccentric knee-extensor activity | Groningen Activity Restriction Scale: No differences between groups at 10–12 weeks |

| Chandler et al. (1998) USA RCT (N = 100) |

Aged ≥ 65; Inability to descend stairs step over step without holding the railing | 10 week exercise program, each week three individual in-home sessions by physiotherapist. Focus: progressive resistive lower extremity exercises with theraband | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale): No significant differences between groups at 10 weeks |

| Chin A Paw et al. (2001) Netherlands RCT (N = 157) |

Aged ≥ 70; Physical inactivity and involuntary weight loss OR body mass index below 25 kg/m² | 17 week exercise program, each week 2 group sessions (45 min) by experienced instructors. Focus: skills training focused on learning physiologic parameters to perform and sustain motor action | Self-rated disabilities (name not specified): No differences between groups at 17 weeks |

| Gill et al. (2002) USA RCT (N = 188) |

Aged ≥ 75; performance on rapid gait test >10 s OR inability to stand up from seated position | 12 month program with average of 16 visits (45–60 min) by physiotherapist and home exercising in the first 6 months, followed by 6 phone calls in the next 6 months to encourage further (daily) home exercising. Focus: instruction in safe techniques, proper use of devices, removal of environmental hazards and exercises for range of motion, balance, muscle conditioning and strengthening | Self-reported performance in activities of daily living (name not specified): Differences (SS) in favor of IG 7 and 12 months |

| Jette et al. (1999) USA RCT (N = 215) |

Aged ≥ 60; limitations in at least 1 of 9 items of Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale) | 6 month program with 3-times a week a (videotaped) exercise program for 35 min with elastic bands varying in thickness to individualize resistance. Physiotherapist did two home visits and provided telephone follow-up and support. Several cognitive and behavioral techniques were used to increase adherence | Sickness Impact Profile 68: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 3 and 6 months |

| King et al. (2002) USA RCT (N = 155) |

Aged ≥ 70; Short Physical Performance Battery score ≤ 9 AND independence in at least 5 ADL’s | 18 month exercise program with 6 months of 3 group sessions (75 min) each week (by physiotherapist and/or exercise leader), followed by 6 months of 1 group session a week and two home-exercise sessions, and 6 months of 3 home exercises a week with monthly call from exercise leader. Focus on endurance, strength, balance and flexibility | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale): Slight difference (NS) in favor of CG at 6 and 12 months. Slight difference (NS) in favor of IG 18 months |

| Latham et al. (2003) New Zealand/Australia RCT (N = 243) |

Aged ≥ 65; one or more health problems or functional limitations | 10 weeks three times a week quadriceps exercise program by physiotherapist. Patients performed their first two session in the hospital and continued the rest of their sessions at home. Physiotherapist monitored progress weekly, alternating home visits with telephone calls | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale)/Barthell Self-care index: No significant differences between groups at 3 and 6 months |

| Luukinen et al. (2006) Finland RCT (N = 555) |

Aged ≥ 85; at least one risk factor for disability or mobility, e.g., falls, loneliness, depression, low cognitive status, impaired vision or hearing, impaired balance | Risk inventarisation and suggestions for interventions done by physiotherapist and occupational therapist were discussed by patient and family physician. Home exercises (recommended three times daily with 5–15 repetitions) focused on a number of physical exercises (standing, lying or sitting position) in combination with self-care exercises, walking exercises or/and physical exercises in groups | Postal questionnaire for physical disability (name not specified): No significant differences between groups at 5 months |

| Ota et al. (2007) Japan RCT (N = 46) |

Aged ≥ 65; eligible for long-term care needs | 12 week program with 24 sessions (twice a week) with training machines focused on leg press, leg extension/flexion, torso extension/flexion, rowing, chest press and hip adduction/abduction | TMIG-IC instrumental self-maintenance: No significant differences between groups at 12 weeks |

| Timonen et al. (2006) Finland RCT (N = 68) |

Aged ≥ 75; difficulty with balance AND mobility AND symptoms such as dizziness or reported falls or difficulty in walking independently | 10 week exercise program, each week two group sessions (90 min) supervised by two physiotherapists. Core of program; progressive resistance training (lower extremity) and functional exercises. One home visit to instruct stretching program to be performed 2–3 times a week at home | Joensuu Classification Model: No significant differences between groups at 1 week, 3 and 9 months |

| Worm et al. (2001) Denmark RCT (N = 46) |

Aged ≥ 74; inability to leave home unaided OR unattended OR without mobility aids | 12 weeks exercise program with 2 group sessions per week (60 min); flexibility training, aerobics and rhythm, balance and reaction exercises, muscle training. Participants were also asked to perform a home-based exercise program (8–10 min) every morning | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale): Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 12 weeks |

| Nutritional interventions | |||

| Chin A Paw et al. (2001) Netherlands RCT (N = 157) |

Aged ≥ 70; physical inactivity and involuntary weight loss OR body mass index below 25 kg/m² | 17 weeks nutrition program; several fruit and dairy products enriched with vitamins and minerals. One fruit and a diary product in addition to daily diet or as a replacement | Self-rated disabilities (name not specified): No significant differences between groups at 17 weeks |

| Kretser et al. (2003) USA RCT (N = 203) |

Aged ≥ 60; score < 22.5 on Mini Nutritional Assessment | 6 month nutrition program consisting of weekly 21 meals and 14 snacks meeting 100% of the Daily Reference Intake (DRI) needed for people over 50 and with a daily caloric level of 1,800 kcal | (Self-?) Reported performance of activities of daily living (name not specified): No significant differences between groups at 6 months |

| Payette et al. (2002) Canada RCT (N = 83) |

Aged > 65; involuntary weight loss and Body Mass Index < 27 OR Body Mass Index < 24 | 16 weeks nutrition program; provision of 235-ml cans of nutrient-dense protein-energy liquid. Two cans a day in addition to usual diet. Each month 1 home visit and each two weeks a phone call was conducted by a dietician | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical role functioning scale and emotional role functioning scale): No significant differences between groups at 16 weeks |

| Assistive technology | |||

| Mann et al. (1999) USA RCT (N = 104) |

Receiving services or initial referral for in-home services or in-patient rehabilitation services in previous year | Assessment done by occupational therapists, followed by recommendations for assistive devices and/or home modifications. Participants were trained in the use of the devices and follow-up continued with assessment and provision of assistive technology as needs changed | Functional Independence Measure/Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (IADL scale). Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 18 months |

| Tomita et al. (2007) USA RCT (N = 113) |

Aged ≥ 60; difficulties in ADL or IADL | About 18 months computer and internet facilities were provided. Level of automatization fitted participants’ desire and the capacity of the house. Computer engineer ensured a good fit between computer and users. Smart technology (door and window sensors, motion sensors and remote control for lamps and radio) was installed. Participants received instruction from a geriatric nurse | Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (IADL score)/CHART mobility: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 24 months |

| Others | |||

| Beck et al. (1997) USA RCT (N = 321) |

Aged ≥ 65; high care utilization AND one of the following diseases: lung disease, heart disease, joint disease, diabetes | Monthly group meetings (12 × 2 h) with primary care physician and nurse (contributions of other professionals). Each session had a warming up period and specific health related topic (e.g., disease processes, medication, exercise, alternate care home safety) were presented. Medical assessment (e.g., blood pressure) took place by the nurse and a meeting with the physician was possible | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale/Older American Resources and Services Multidimensional Functional Assessment Questionnaire (IADL score): No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| Giannini et al. (2006) Italy CCT (N = 121) |

Aged (not clear): necessity of help in two ADL or severely chronically ill with mental impairment (Mini Mental State Examination score < 24/30) | Additional home care attendance (HCA) 24 months varying from 4 to 24 h daily. The primary caregiver got vouchers to buy the amount of hours of HCA from health providers who demonstrated to have professional training in the care of frail elderly | Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale/Lawton & Brody Instrumental Activities of Daily Living Scale: Differences (SS) in favor of IG at 24 months |

| Latham et al. (2003) New Zealand/Australia RCT (N = 243) |

Aged ≥ 65; one or more health problems or functional limitations | Vitamin D in a single oral dose. Patients received six 1.25-mg calciferol | Medical Outcome Study Short Form (physical functioning subscale)/Barthell Self-care index: No significant differences between groups at 3 and 6 months |

| Liang et al. (1986) USA RCT (N = 57) |

Inability to perform self-care tasks OR ADL dysfunction AND potential for rehabilitation, judged by physician, home care and physiotherapist for ≥3 months | Two months treatment program provided by physician and physiotherapist with occasional consultation with hospital-based rehabilitation specialists. Interventions included equipment and assistive devices, supervised exercises to improve function and home modifications for safety and improved function | Functional Status Index: No significant differences between groups at 2, 4 and 6 months |

| Ollonqvist et al. (2008) Finland RCT (N = 708) |

Aged ≥ 65; eligibility criteria for SII allowance for pensioners with a medical disability as verified by a physician to be in need of assistance | 3 separate inpatient treatment periods at a rehabilitation centre within 8 months provided by a team (e.g., physician, physiotherapist, social worker, occupational therapist) with focus on physical activation (group). Home visit for advice on personal hygiene and assistive devices. Activation days between rehabilitation periods with focus on discussing topics, e.g., as safety at home, health promotion and cognition | ADL and IADL items (name not specified): No significant differences between groups at 12 months |

| Scott et al. (2004) USA RCT (N = 294) |

Aged ≥ 60; one or more chronic conditions AND at least 11 outpatient clinic visits in the past 18 months | Monthly group meetings (12 × 2 h) with primary care physician and nurse (contributions of other professionals). Each session had a warming up period and specific health related topic (e.g., disease processes, medication, exercise, alternate care home safety) were presented. Medical assessment (e.g., blood pressure) took place by the nurse and a meeting with the physician was possible | ADL and IADL items (name not specified). No significant differences between groups at 24 months |

*Instruments used to measure disability and reported differences (SS = statistically significant difference if p < 0.05; NS = not statistically significant difference) between intervention group (IG) and control group (CG) at follow-up. Follow-up measurements are in weeks or months after randomization, unless stated otherwise

Intervention characteristics

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (N = 26)

Comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) has been defined as ‘a multidimensional, often interdisciplinary, diagnostic process intended to determine a frail older person’s medical, psychosocial, and functional capabilities and problems, with the objective of developing an overall plan for treatment and long-term follow-up’ (Rubenstein et al. 1989). For this review, the included CGA studies were further divided into transmural care and community-based care. In the latter, a distinction was made between studies in which assessment was followed by referrals or recommendations and studies where assessment was directly followed by treatment and care.

Transmural care (N = 7)

In this review, transmural care points to interventions in which clients were identified and assessed during admission to the hospital setting. After discharge, client referrals were made and interventions were delivered in the community. In the seven studies, assessment was performed by a nurse practitioner (McCusker et al. 2001; Naylor et al. 1999; Siu et al. 1996), a physician (Hughes et al. 1990), or an interdisciplinary team (Burns et al. 1995, 2000; Oktay and Volland 1990; Rubin et al. 1993) focusing on a variety of physical, mental, medical, and social factors. Usually, the assessment was followed by a team meeting leading to an individualized treatment plan and a variety of actions, e.g., referrals (McCusker et al. 2001) and recommendations to the general practitioner (Siu et al. 1996), home visits by a nurse practitioner (Naylor et al. 1999) or several disciplines (Hughes et al. 1990; Oktay and Volland 1990; Siu et al. 1996) and long-term outpatient comprehensive care by a geriatric clinic (Burns et al. 1995, 2000; Rubin et al. 1993). Nursing interventions targeted, for example, medications, symptom management, diet, activity, sleep, medical follow-up, and emotional status (Naylor et al. 1999). The interdisciplinary team in the studies by Burns et al. (1995, 2000) focused on functional limitations, gait impairment, incontinence, polypharmacy, depression, cognitive impairments, and caregiver needs.

Out of the seven transmural care interventions, one study reports significant effects in favor of the experimental group (McCusker et al. 2001). Pointing out effective elements is difficult. In the study by McCusker et al. (2001), a two-step screening approach including the ISAR screening tool was used. This screening tool, specifically designed and evaluated for identifying seniors at high risk, might have increased the efficacy of the selection of participants.

In the study by McCusker et al. (2001), treatment was individualized and frail older persons were seen by a variety of disciplines. Referrals were made to the physician, local community, health centre, geriatric outpatient clinic, and other community services. Comparable features, however, are present in the other CGA ‘transmural care’ studies that did not report effectiveness on disability.

Community-based care: assessment followed by referrals and recommendations (N = 4)

Eligible participants for these four studies were identified by a self-administered postal questionnaire (Robichaud et al. 2000; Hebert et al. 2001), telephone interview (Silverman et al. 1995), or an interviewer-assisted self-administered screening (Reuben et al. 1999). Extensive assessment was performed by a nurse during home visits (Hebert et al. 2001; Robichaud et al. 2000) or by a team in community-based clinics (Reuben et al. 1999; Silverman et al. 1995). Medication, mood, cognition, vision, hearing, blood pressure, gait and balance, orthostatic hypotension, environmental risk of fall, malnutrition, incontinence, and social support were part of the assessment in the studies by Hebert et al. (2001) and Robichaud et al. (2000). In all studies, the assessment was followed by recommendations to the general practitioner. In the study by Hebert et al. (2001) and Robichaud et al. (2000), recommendations to other health professionals were also made and bi-monthly or monthly phone follow-up interviews took place (Hebert et al. 2001; Robichaud et al. 2000). In the study by Silverman et al. (1995), the treatment plan was discussed with the frail older person and family. Preparation of the frail older person and caregiver for the meeting with the general practitioner was part of the intervention in the study by Reuben et al. (1999).

Out of these four community-based CGA studies, only the study by Reuben et al. (1999) found significant differences in disability in favor of the experimental group. The near-significant effect that Robichaud et al. (2000) found did not reach significance in the study by Hebert et al. (2001) in the evaluation of the same intervention among a larger group of participants. As all other three interventions have similar features to those of Reuben et al. (1999), elements that produce effectiveness in this type of CGA cannot be identified.

Community-based care: assessment followed by treatment (N = 15)

Two out of 15 studies are about the same intervention (Engelhardt et al. 1996; Toseland et al. 1996). All interventions were delivered by an interdisciplinary team consisting of at least two disciplines. Members of the interdisciplinary team were, for example, general practitioners, geriatricians, nurses, nurse practitioners, social workers, allied health professionals, or medical specialists. The core of the intervention was mainly delivered by primary care professionals. Professionals working in institutions, for example, a geriatric clinic, were, however, often involved in the assessment and the development of the treatment plan, including referrals and recommendations. In addition, they could be consulted about the delivery of supplementary treatment if needed. In many interventions, one person from the interdisciplinary team, often a nurse (practitioner), had the role of a case-manager (Bernabei et al. 1998; Gagnon et al. 1999; Landi et al. 2001; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melin and Bygren 1992; Melis et al. 2008; Phelan et al. 2004; Rubenstein et al. 2007). The case-manager was responsible for planning, coordination, monitoring, and evaluation of assessment and treatment. The assessment in the 15 studies focused on medical conditions and general status of the participants (functional, psychosocial, cognitive, affective, and nutritional), personal resources and preferences, caregiver’s capabilities, and other environmental factors. The focus of the interventions varied strongly across studies. Issues covered were falls, balance, urinary incontinence, functional impairment, depression, cognitive deficits, nutrition, mobility, medication, social support, service use, communication, environmental aspect, and financial needs.

Nearly all interventions were delivered in an individual format, except for Phelan et al. (2004), who combined individual sessions with group sessions (exercise and self-management classes). Home visits (Williams et al. 1987; Bernabei et al. 1998; Rockwood et al. 2000; Landi et al. 2001; Melis et al. 2008), telephone calls (Rubenstein et al. 2007), or a combination of both (Melin and Bygren, 1992; Phelan et al. 2004; Gitlin et al. 2006; Markle-Reid et al. 2006) are repeatedly used. In three studies, assessment and treatment were done in a (geriatric) clinic (Cohen et al. 2002; Engelhardt et al. 1996; Toseland et al. 1996). Two studies combined clinic visits, home visits, and telephone contacts (Boult et al. 2001; Rubenstein et al. 2007).

Out of 15 CGA studies, 9 studies report significant differences in disability in favor of the experimental group (Bernabei et al. 1998; Boult et al. 2001; Cohen et al. 2002; Gitlin et al. 2006; Landi et al. 2001; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melin and Bygren 1992; Melis et al. 2008; Phelan et al. 2004). There are some features that promising interventions have in common. Out of the nine studies, seven studies report the use of an individualized treatment plan that is based on a multidimensional assessment (Bernabei et al. 1998; Boult et al. 2001; Cohen et al. 2002; Gitlin et al. 2006; Landi et al. 2001; Melin and Bygren 1992; Melis et al. 2008). A case-manager had a key role during the intervention process in six out of nine effective studies (Bernabei et al. 1998; Landi et al. 2001; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melin and Bygren 1992; Melis et al. 2008; Phelan et al. 2004). Regular team meetings were applied in four studies (Bernabei et al. 1998; Cohen et al. 2002; Melin and Bygren 1992; Melis, et al. 2008). In seven out of the nine studies, ongoing assessment, evaluation, and monitoring are described as a feature of the intervention (Bernabei et al. 1998; Boult et al. 2001; Gitlin et al. 2006; Landi et al. 2001; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melis et al. 2008; Phelan et al. 2004). Therefore, a combination of home visits and telephone contacts is often used (Gitlin et al. 2006; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melin and Bygren 1992; Phelan et al. 2004; Rubenstein et al. 2007). Out of nine studies, four interventions also intervene in factors in the social and physical environments of frail older persons (Boult et al. 2001; Gitlin et al. 2006; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melis et al. 2008). Health education is applied in four interventions (Boult et al. 2001; Gitlin et al. 2006; Markle-Reid et al. 2006; Melis et al. 2008; Rubenstein et al. 2007). A complication in drawing conclusions about elements that contributed to effectiveness is the presence of identical features in the six clinical trials that did not show any differences for disability (Engelhardt et al. 1996; Gagnon et al. 1999; Rockwood et al. 2000; Rubenstein et al. 2007; Toseland et al. 1996; Williams et al. 1987). There is, however, some indication that case management, individualized treatment, multidimensional assessment, and ongoing evaluation and monitoring are relevant features in this type of CGA interventions. A combination of home visits and telephone contacts and regular team meetings seems to be promising. Health education may also be an important component for future interventions.

Physical exercise programmes (N = 12)

Twelve studies describing physical exercise interventions were found. Physical exercise interventions for community-dwelling frail older persons show a large variation in content, duration, intensity, balance between supervised and non-supervised sessions, and level of individualization. Five interventions were single-component, focusing mainly on lower extremity strength (Boshuizen et al. 2005; Chandler et al. 1998; Jette et al. 1999; Latham et al. 2003; Ota et al. 2007). The other seven were multi-component, addressing a variety of physical parameters such as endurance, flexibility, balance, and strength (Binder et al. 2002; Chin A Paw et al. 2001; Gill et al. 2002; King et al. 2002; Luukinen et al. 2006; Timonen et al. 2006; Worm et al. 2001). All interventions were offered by professionals in physical exercise, mostly physical therapists. In most studies, participants performed at least three exercise sessions a week (Binder et al. 2002; Boshuizen et al. 2005; Chandler et al. 1998; Gill et al. 2002; Jette et al. 1999; King et al. 2002; Latham et al. 2003; Luukinen et al. 2006; Timonen et al. 2006; Worm et al. 2001). Strength training was usually comprised of a number of exercises for improvement of lower body strength using weights (Latham et al. 2004), elastic bands (Boshuizen et al. 2005; Chandler et al. 1998; Jette et al. 1999), or training machines (Ota et al. 2007). Among the multi-component exercise programmes, three addressed several parameters in all exercise sessions (Luukinen et al. 2006; Timonen et al. 2006; Worm et al. 2001). These also belong to the shortest multicomponent exercise programmes (10–12 weeks). The longest multi-component programmes lasted 9 months (Binder et al. 2002), 12 months (Gill et al. 2002), and 18 months (King et al. 2002). In two studies (Binder et al. 2002; King et al. 2002), different phases (respectively, 3 or 6 months) were distinguished with a focus on specific physical parameters in each phase. The content of the programme of Gill et al. (2002) was more individualized, as the outcomes of an extensive assessment directed the programme. Among the physical exercise programmes, there is a large difference between the number of supervised and non-supervised sessions. For example, Binder et al. (2002) report a total of 108 supervised sessions, while Jette et al. (1999) report only two home visits by a physical therapist. The participants exercised non-supervised, supported by techniques to enhance adherence (Jette et al. 1999).

Out of 12 physical exercise programmes, 4 report significant positive effects for disability. Of the single-component physical exercise programmes (n = 5), one reports positive effects. Jette et al. (1999) found evidence for the effect of resistance training using elastic bands. For three (out of seven) multi-component programmes, significant positive effects are reported on the disability outcome (Binder et al. 2002; Gill et al. 2002; Worm et al. 2001). In these three studies, older persons were included according to physical frailty indicators, and programmes were relatively intensive with at least three exercise sessions per week. Binder et al. (2002) included only moderate physically frail older persons; Gill et al. (2002) found that only moderate physically frail older persons benefited from their intervention.

Nutrition (N = 3)

Studies that investigated the effect of single nutritional interventions focused on macronutrient status (nutrient-dense protein-energy liquid: Payette et al. 2002), micronutrient status (fruits and dairy products enriched with vitamins and minerals: Chin A Paw et al. 2001) or both (meals and snacks providing 100% of macro- and micronutrient requirements: Kretser et al. 2003). In the study by Kretser et al. (2003) participants received 21 meals and 14 snacks every week for 6 months, accounting for most of the daily nutritional intake. In Chin A Paw et al.’s study (2001), frail older persons were asked to eat the products in addition to their daily diet or as a replacement (for 17 weeks). In Payette et al. (2002), the liquid product was an addition to the usual daily dietary intake for 16 weeks. Additional support included monthly home visits by dieticians and a phone call every 2 weeks with nutritional counseling and encouragement (Payette et al. 2002) or daily additional phone calls from older adult volunteers to provide a measure of safety and socialization (Kretser et al. 2003). Despite an observed effect on total energy intake (Payette et al. 2002) and weight gain (Kretser et al. 2003; Payette et al. 2002), none of the three nutritional intervention studies (Chin A Paw et al. 2001; Kretser et al. 2003; Payette et al. 2002) report evidence for the effect of nutritional interventions on disability.

Technological interventions (N = 2)

Environmental adaptations are often part of the multifactorial and multidisciplinary programmes described under CGA. Two reports were found on the effect of single assistive devices and home modifications (Mann et al. 1999) and smart technology on disability (Tomita et al. 2007). In the study by Mann et al. (1999), an occupational therapist performed a comprehensive functional assessment of the person and the home followed by recommendations for assistive devices and/or home modifications. Participants were trained in the use of the devices and follow-up continued with assessment and provision of assistive technology as needs changed. Over about 18 months computer and internet facilities were provided to the participants in the study by Tomita et al. (2007). A computer engineer adapted the computer to ensure was a good fit with its users. Furthermore, smart technology, like door and window sensors, motion sensors, and remote control for lamps and radio, was installed. The level of automatization was determined by the participants’ desire and the capacity of the house. Participants received instruction from a geriatric nurse who was a specialist in computer instruction.

Both studies (Mann et al. 1999; Tomita et al. 2007) report significant differences on disability in favor of the experimental group. In both interventions, there is an emphasis on the adaptation of technology toward the needs of the frail older persons and on intensive instruction in the use of devices.

Other interventions (N = 6)

In this group, six interventions are described. Latham et al. (2003) studied the effect of Vitamin D. Participants in the experimental group received 1.25 mg calciferol. Giannini et al. (2007) focused on the effect of home care attendance (between 4 and 24 h) by professionals with training in the care of frail older persons. In two studies (Beck et al. 1997; Scott et al. 2004), the intervention consisted of monthly group meetings (over 12 months) with a physician and a nurse. The meetings focused on health promotion and control. One intervention (Ollonqvist et al. 2008) contains three inpatient rehab periods with individual and group sessions plus home activation days and home visits for personal hygiene and assistive devices. Liang et al. (1986) used a stepped-up treatment (on top of nursing and social services) provided by a physician and physical therapist focusing on assistive devices and home modification and supervised exercises.

Out of the six interventions, Giannini et al. (2007) report significant positive effects on disability in favor of the experimental group. They describe how the home care attendance, provided by a nurse trained in the care of frail older persons, was delivered according to a programme established by a Geriatric Evaluation Unit. Specific features of this programme are lacking.

Discussion

This review offers a comprehensive overview of the content of interventions targeted at disability prevention in community-dwelling frail older persons. In total, 48 clinical trials evaluating 49 interventions aimed at disability prevention were identified. The majority of trials in 46 RCTs and 2 CCTs were conducted in the field of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) (n = 26). Studies of physical exercise programmes are the second largest group of interventions (n = 12). There is a small number of studies that specifically focuses on the effect of technology (n = 2) or nutrition (n = 3) on disability in community-living frail older persons. Both environmental adaptations and nutrition, however, are frequently mentioned as part of the CGA studies. The results show a large diversity within and between the groups of interventions in terms of content, disciplines involved, duration, intensity, and setting.

The reported effectiveness of interventions is not consistent. Only 18 of the 49 interventions reported significant positive effects for disability for the experimental group. As most studies did not include long-term follow measurement, the preventive potential of interventions remains unclear for the time period after the completion of the intervention.

The most promising findings were found for technology (but only two studies), CGA ‘assessment followed by treatment’ (9 out of 15 studies) and, to a lesser extent, physical exercise programmes (4 out of 12).

Technology, adapted to the needs of the frail older persons and well-taught, may be very effective in preventing disability in community-dwelling frail older persons, though more research is needed in this area.

Most trials were conducted in CGA, but the reported effectiveness of CGA for community-dwelling frail older persons is inconsistent. Comparable findings are reported in previous reviews on CGA (Beswick et al. 2008; Wieland 2003; Wieland and Hirth 2003). Individualized, multifactorial and multidisciplinary assessments and interventions, case management, and ongoing monitoring (long-term management) seem to be essential elements for effective CGA.

The mixed results of physical exercise programmes hamper the identification of effective elements. There is, however, some indication that multi-component high intensive physical exercise programmes may be promising, especially for moderate physically frail community-dwelling older persons.

This overview has some limitations. The use of the term frailty in the literature is relatively new. Although reference lists were checked, a limitation of this overview is that older studies might not have been identified as we searched with terms for frailty and its synonyms. Another risk in terms of publication bias is the selection of 4,602 studies on title-level that may have resulted in the exclusion of relevant articles. Only randomised and controlled clinical trials were selected as we considered these as a (minimal) standard for quality. Some caution in interpretation of results is warranted as the methodological quality of the studies was not assessed. Furthermore, we analyzed the results in a qualitative way. As a consequence effect sizes of interventions were not calculated or taken into account. And last, owing to small sample sizes, trials may have been underpowered to detect differences in the self-reported measures for disability.

Recent literature on disability development suggests that disability is multifactorial in nature. Stuck et al. (1999) reported that risk factors for developing disability in community-dwelling elderly are cognitive impairment, depression, comorbidity, increased and decreased body mass index, lower extremity functional limitation, low frequency of social contacts, and low level of physical activity. Femia et al. (2003) suggest that although disease conditions and physical impairments are as risk factors strongly related to an individual’s ability to carry out activities of daily living, other factors like the beliefs about one’s health (e.g., subjective health), motivation and self-efficacy are potentially as important as the ability to perform them. Therefore, it seems that a combination of risk factors and other factors plays a role in the development of disability implying that disability prevention in frail elderly is complex.

In view of this complexity, the Dutch National Health Council recently pointed out the need for research on ‘function-oriented prevention’. The Health Council states that knowledge of the effectiveness of preventive interventions on disability is fragmented, heterogenic, and still lacking in a variety of areas (Health Council of the Netherlands 2009).

How might the findings of this overview influence future interventions for community-dwelling frail older persons? In the light of this overview, future interventions may be directed toward tailor-made, multidisciplinary and multifactorial interventions, with individualized assessment and interventions conducted by a (primary) care team, involving case management, and long-term follow-up. These tailor-made programmes may include a physical exercise component for moderate physically frail older persons and a technology component tailored to the needs of the clients.

Several new elements might be added to future interventions. For example, technology for monitoring health conditions and enhancing compliance and communication between health professionals and clients is available and can be incorporated in interventions for frail older persons (Botsis and Hartvigsen 2008). Techniques for enhancing self-management abilities in the older persons have been described in several studies (Frieswijk et al. 2006; Lamers et al. 2006) and seem applicable to, and promising for, community-dwelling frail older persons. A systematic approach toward enabling community-dwelling frail older persons to be engaged in meaningful social and productive activities might also be effective to prevent disability, as it fosters natural motivation and self-efficacy in older persons. Recent studies show the potential of meaningful activities as a core of preventive programmes (Fried et al. 2004b; Graff et al. 2006).

It is likely that the development of interventions for community-living frail older persons has still some way to go. Further research with a focus on interventions that can prevent or delay disability in community-dwelling frail older persons is necessary.

References

Studies with an asterisk are part of the analysed papers.

- Aminzadeh F, Dalziel W, Molnar F. Targeting frail older adults for outpatient comprehensive geriatric assessment and management services: an overview of concepts and criteria. Rev Clin Gerontol. 2002;12:82–92. doi: 10.1017/S0959259802121101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Avlund K. Disability in old age. Longitudinal population-based studies of the disablement process. Dan Med Bull. 2004;51:315–349. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Beck A, Scott J, Williams P, Robertson B, Jackson D, Gade G, Cowan P. A randomized trial of group outpatient visits for chronically ill older HMO members: the Cooperative Health Care Clinic. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1997;45:543–549. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1997.tb03085.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Bernabei R, Landi F, Gambassi G, Sgadari A, Zuccala G, Mor V, Rubenstein LZ, Carbonin P. Randomised trial of impact of model of integrated care and case management for older people living in the community. BMJ. 1998;316:1348–1351. doi: 10.1136/bmj.316.7141.1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, Ayis S, Gooberman-Hill R, Horwood J, Ebrahim S. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in older persons people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371:725–735. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60342-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Binder EF, Schechtman KB, Ehsani AA, Steger-May K, Brown M, Sinacore DR, Yarasheski KE, Holloszy JO. Effects of exercise training on frailty in community-dwelling older adults: results of a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:1921–1928. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Boshuizen HC, Stemmerik L, Westhoff MH, Hopman-Rock M. The effects of physical therapists’ guidance on improvement in a strength-training program for the frail older persons. J Aging Phys Act. 2005;13:5–22. doi: 10.1123/japa.13.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botsis T, Hartvigsen G. Current status and future perspectives in telecare for older persons people suffering from chronic diseases. J Telemed Telecare. 2008;14:195–203. doi: 10.1258/jtt.2008.070905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Boult C, Boult LB, Morishita L, Dowd B, Kane RL, Urdangarin CF. A randomized clinical trial of outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:351–359. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49076.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bours GJ, Ketelaars CA, Frederiks CM, Abu-Saad HH, Wouters EF. The effects of aftercare on chronic patients and frail older persons patients when discharged from hospital: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 1998;27:1076–1086. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.1998.00647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Burns R, Nichols LO, Graney MJ, Cloar FT. Impact of continued geriatric outpatient management on health outcomes of older veterans. Arch Intern Med. 1995;155:1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, Graney MJ. Interdisciplinary geriatric primary care evaluation and management: two-year outcomes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:8–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chandler JM, Duncan PW, Kochersberger G, Studenski S. Is lower extremity strength gain associated with improvement in physical performance and disability in frail, community-dwelling elders? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1998;79:24–30. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(98)90202-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Chin A, Paw MJ, Jong N, Schouten EG, Hiddink GJ, Kok FJ. Physical exercise and/or enriched foods for functional improvement in frail, independently living older persons: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2001;82:811–817. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2001.23278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Cohen HJ, Feussner JR, Weinberger M, Carnes M, Hamdy RC, Hsieh F, Phibbs C, Courtney D, Lyles KW, May C, McMurtry C, Pennypacker L, Smith DM, Ainslie N, Hornick T, Brodkin K, Lavori P. A controlled trial of inpatient and outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:905–912. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa010285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM. Declining disability among the older persons. Health Aff. 2001;20:11–27. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.20.6.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Engelhardt JB, Toseland RW, O’Donnell JC, Richie JT, Jue D, Banks S. The effectiveness and efficiency of outpatient geriatric evaluation and management. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1996;44:847–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1996.tb03747.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza S, Walston JD. Frailty in older adults: insights and interventions. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72:1105–1112. doi: 10.3949/ccjm.72.12.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrucci L, Guralnik JM, Studenski S, Fried LP, Cutler GB, Jr, Walston JD. Designing randomized, controlled trials aimed at preventing or delaying functional decline and disability in frail, older persons: a consensus report. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:625–634. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52174.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Ferrucci L, Darer J, Williamson JD, Anderson G. Untangling the concepts of disability, frailty, and comorbidity: implications for improved targeting and care. J Gerontol A. 2004;59:255–263. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.3.m255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fried LP, Carlson MC, Freedman M, Frick KD, Glass TA, Hill J, McGill S, Rebok GW, Seeman T, Tielsch J, Wasik BA, Zeger S. A social model for health promotion for an aging population: initial evidence on the Experience Corps model. J Urban Health. 2004;81:64–78. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jth094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frieswijk N, Steverink N, Buunk BP, Slaets JP. The effectiveness of a bibliotherapy in increasing the self-management ability of slightly to moderately frail older people. Patient Educ Couns. 2006;61:219–227. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2005.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gagnon AJ, Schein C, McVey L, Bergman H. Randomized controlled trial of nurse case management of frail older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1118–1124. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb05238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Giannini R, Petazzoni E, Savorani G, Galletti L, Piscaglia F, Licastro F, Bolondi L, Cucinotta D. Outcomes from a program of home care attendance in very frail older persons subjects. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;44:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gill TM, Baker DI, Gottschalk M, Peduzzi PN, Allore H, Byers A. A program to prevent functional decline in physically frail, older persons who live at home. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1068–1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa020423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Gitlin LN, Winter L, Dennis MP, Corcoran M, Schinfeld S, Hauck WW. A randomized trial of a multicomponent home intervention to reduce functional difficulties in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:809–816. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00703.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graff MJ, Vernooij-Dassen MJ, Thijssen M, Dekker J, Hoefnagels WH, Rikkert MG. Community-based occupational therapy for patients with dementia and their care givers: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2006;333:1196. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39001.688843.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health Council of the Netherlands . Prevention in the elderly: focus on functioning in daily life. The Hague: Health Council of the Netherlands; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- *Hebert R, Robichaud L, Roy PM, Bravo G, Voyer L. Efficacy of a nurse-led multidimensional preventive programme for older people at risk of functional decline. A randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2001;30:147–153. doi: 10.1093/ageing/30.2.147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogan DB, MacKnight C, Bergman H. Models, definitions, and criteria of frailty. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2003;15:1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooi WC, Bergman H (2005) A review on models and perspectives on frailty in older persons. SGH Proceedings 14

- *Hughes SL, Cummings J, Weaver F, Manheim LM, Conrad KJ, Nash K. A randomized trial of Veterans Administration home care for severely disabled veterans. Med Care. 1990;28:135–145. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199002000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jette AM. Towards a common language for function, disability and health. Phys Ther. 2006;86(5):726–734. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Jette AM, Lachman M, Giorgetti MM, Assmann SF, Harris BA, Levenson C, Wernick M, Krebs D. Exercise—it’s never too late: the strong-for-life program. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:66–72. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.1.66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *King MB, Whipple RH, Gruman CA, Judge JO, Schmidt JA, Wolfson LI. The Performance Enhancement Project: improving physical performance in older persons. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2002;83:1060–1069. doi: 10.1053/apmr.2002.33653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Kretser AJ, Voss T, Kerr WW, Cavadini C, Friedmann J. Effects of two models of nutritional intervention on homebound older adults at nutritional risk. J Am Diet Assoc. 2003;103:329–336. doi: 10.1053/jada.2003.50052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lally F, Crome P. Understanding frailty. Postgrad Med J. 2007;83:16–20. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.2006.048587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamers F, Jonkers CC, Bosma H, Diederiks JP, van Eijk JT. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of a minimal psychological intervention to reduce non-severe depression in chronically ill older persons patients: the design of a randomised controlled trial [ISRCTN92331982] BMC Public Health. 2006;6:161. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-6-161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Landi F, Onder G, Tua E, Carrara B, Zuccala G, Gambassi G, Carbonin P, Bernabei R. Impact of a new assessment system, the MDS-HC, on function and hospitalization of homebound older people: a controlled clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1288–1293. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.49264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Latham NK, Anderson CS, Lee A, Bennett DA, Moseley A, Cameron ID. A randomized, controlled trial of quadriceps resistance exercise and vitamin D in frail older people: the Frailty Interventions Trial in Older persons Subjects (FITNESS) J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003;51:291–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Latham NK, Bennett DA, Stretton CM, Anderson CS. Systematic review of progressive resistance strength training in older adults. J Gerontol A. 2004;59:48–61. doi: 10.1093/gerona/59.1.m48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levers MJ, Estabrooks CA, Ross Kerr JC. Factors contributing to frailty: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2006;56:282–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.04021.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Liang MH, Partridge AJ, Gall V, Taylor J. Evaluation of a rehabilitation component of home care for homebound older persons. Am J Prev Med. 1986;2:30–34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Luukinen H, Lehtola S, Jokelainen J, Vaananen-Sainio R, Lotvonen S, Koistinen P. Prevention of disability by exercise among the older persons: a population-based, randomized, controlled trial. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2006;24:199–205. doi: 10.1080/02813430600958476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Mann WC, Ottenbacher KJ, Fraas L, Tomita M, Granger CV. Effectiveness of assistive technology and environmental interventions in maintaining independence and reducing home care costs for the frail older persons. A randomized controlled trial. Arch Fam Med. 1999;8:210–217. doi: 10.1001/archfami.8.3.210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markle-Reid M, Browne G. Conceptualizations of frailty in relation to older adults. J Adv Nurs. 2003;44:58–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2648.2003.02767.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *Markle-Reid M, Weir R, Browne G, Roberts J, Gafni A, Henderson S. Health promotion for frail older home care clients. J Adv Nurs. 2006;54:381–395. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2006.03817.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]