Abstract

From a place of “genealogical equivalence” as children of their parents, siblings spend a lifetime developing separate identities. As parents near the end of their lives, issues of sibling equivalence are renegotiated in the face of equal obligations to provide care and equal entitlement to parent assets. In this paper, we hypothesize how unresolved issues of rivalry for parent affection/attention among siblings may be reasserted when parents need care. Data are drawn from a project about how parent care and assets are shared. In-depth interviews with three sibling groups experiencing conflict over sharing parent care and assets along with six Canadian legal case portrayals of disputes among siblings over how parent care and assets were shared are examined. Findings are that disputes occur when siblings perceive others as dominating parent care and assets through tactics such as separating the parent from other siblings and preventing other siblings from being engaged in decisions about care and assets. Discussion is focused on paradoxes faced by siblings given expectations for equity in parent relationships alongside perceived pre-eminence in care and asset decisions.

Keywords: Parent care, Siblings, Equity, Equivalence, Undue influence, Ageing

Introduction

Population ageing has resulted in great concern about sources of care for older adults with chronic health problems. Increasingly families are viewed as being central to the solution, having primary responsibility for such care (Keefe and Fancey 2000; Port et al. 2005; Wisensale 2005); concern is expressed as well that families may lack the resources to care, especially given falling birth rates and fewer children in each generation. In North America, marriage and fertility rates have been declining for nearly 50 years and some scholars have argued that the resultant “bean pole” family with few members in each generation and weak affinal ties is a main source of reduced family care potential (Brannen et al. 2004; Walz and Mitchell 2007).

The cohort of adults now in advanced old age is in a unique situation vis-a-vis these changing family structures. Many were in their child-bearing years after WWII. Following a century-long decline in fertility, the average number of children born to couples in Canada rose during this period, reaching 3.9 births per woman by the end of the 1950s (Turcotte and Schellenberg 2007). Thus people currently in advanced old age are more likely than any living generation to have large numbers of children (Davey and Szinovacz 2008). Data on family contact by older Canadians suggest that at the aggregate, these older adults are embedded in large, supportive family networks. They are more likely than those in younger generations to have regular contact with relatives and to have a high proportion of immediate family members in their social networks (Turcotte and Schellenberg 2007).

Ties between these older adults and their adult children also may be financial. Older Canadians have been called the “trillion dollar generation”, reflecting the magnitude of the net worth of this cohort (Maser and Dufour 2001). Up to half of the wealth of younger generations comes from transfers from parents (Gale and Scholz 1994). One basis for generational connections is the potential for inheritance.

As a collective, older Canadians appear to have excellent social capital in a relatively large group of adult children with whom they have strong connections. When care is needed, adult children are the most likely group of relatives to provide instrumental and emotional assistance (Karantzas et al. 2003; Lawrence et al. 2002). In fact Turcotte and Schellenberg (2007, p. 167) argue that having more children is an “obvious asset”, citing as evidence the fact that the proportion of older adults who receive care exclusively from informal sources is twice as large among those who have six or more children, as among those with none.

In this paper we turn to this assumption that having more children is an obvious caregiving asset. We shift the lens from care received by older adults to an exploration of the dynamics of sibling groups in relation to care decisions. Our purpose is to contribute to understandings of views of fairness among caregiving siblings by illuminating the processes involved as members of sibling groups negotiate and assume care tasks and responsibilities. We focus on tensions over power and identity that can accompany these processes. Drawing upon theoretical constructs of social exchange, equity, filial responsibility, genealogical equivalence and undue influence, we contribute to the literature on structured differentiation of siblings in their parent-care activities. In examining situations in which tensions among siblings are related to involvement in care, we increase knowledge about difficulties faced by caregiving groups.

Siblings and parent care

An examination of caregiving by groups of siblings to an older parent provides insight into the complexities of same-generation and cross-generation relationships in families. Siblings born of the same parents have the longest standing kinship relationships, extending from birth to death. Siblings also have genealogically equivalent relationships to their parents (Finch and Mason 1990), sharing the same location in the family lineage.

Sibling relationships are multifaceted, characterized by tensions between the intimacy of such close relationships and the conflicts that arise from them (Apter 2007; Hequembourg and Brallier 2005). Beginning early in life, siblings experience both a strong sense of identification inherent in their equivalent status and a strong need for differentiation from each other (Apter 2007; Sulloway 1996). Yet relatively little is known about issues of sibling identification and differentiation in adult life stages. Adult sibling relationships have been described as weakly regulated by social norms so that patterns of closeness and contact are idiosyncratic (Conley 2004).

Parent care is a sibling experience where identities relative to ageing parents and relative to each other are reasserted (Harris 1998; Lashewicz et al. 2007). Regardless of the quality of their relationships, the centrality of the sibling bond extends to a shared sense of “ownership” of responsibility for ageing parents (Globerman 1995; Lashewicz et al. 2007). The terms filial obligation and filial responsibility have used to describe a combination of love, duty and the desire to reciprocate for their upbringing on the part of adult children (Aronson 1990; Gans and Silverstein 2006; Ohta and Kai 2007). Adult children who care for their parents have a strong sense of filial obligation experienced both personally, and as a commitment to parents and other siblings (Cicirelli 1995; Donorfio and Kellett 2006). Siblings have a further expectation that parent care responsibilities and tasks will be shared among them (Connidis 2001; Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2003) evidencing their sense of equivalence in relation to parents. For their part, older adults are less likely to expect equal filial responsibility; parents have different expectations for care from adult children who are not employed, who do not have children of their own, and from sons compared to daughters (van der Pas et al. 2005).

Sibling expectations for sharing care responsibilities do not necessarily translate into equality in types or amounts of care provided. Contributions to parent care are often diverse and uneven (Globerman 1995). Silverstein et al. (2008, p. 74) state that “while it is reasonable to assume that siblings share somewhat similar attitudes towards filial duties as a result of having been reared in common home environments, it also is likely that siblings differ based on their unique experiences and social characteristics”. Factors such as personality, gender, other family responsibilities, employment status, and proximity to the care recipient, have been shown to influence expectations for the type and extent of sibling involvement (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2003). Siblings may justify limited participation in caregiving in terms of living at a distance or as a result of having a full-time job (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2003). The influence of gender is evident in the ways in which the division of caregiving responsibility is negotiated among siblings, with brothers sometimes becoming involved in caregiving in roles of helpers and co-providers while sisters more likely become care coordinators (Hequembourg and Brallier 2005).

Much of the literature on siblings and care has been focused on understanding pathways toward differential involvement of siblings. For example, Merrill (1997) found that caregiving sometimes is apportioned to one sibling by default because other siblings are not available or perceived to be capable. Alternatively, caregivers and their tasks may be decided through a family meeting process where some siblings indicate that they are not available (Merrill 1997). Caregivers also may be selected directly by the care-receiving parent based on a perceived match in such characteristics as gender and closeness of relationship (Pillemer and Suitor 2006). Responsibility for providing care may be divided disproportionately among siblings based on the history of the relationship between each sibling and their parent (Connidis and Kemp 2008). Finally, caregiving may evolve from situations of co-residence or training related to caregiving or may emerge because one sibling volunteers for the role (Merrill 1997).

Caregiving in action: evaluating costs and fairness

How then do a group of adults who share a long family history, and who see themselves as equally responsible for parent caregiving, come to terms with inequalities in caregiving contributions? This is relatively unexplored territory. As Silverstein et al. (2008) observe, “most studies that examine division of labor in caregiving do not consider the perspectives of those who actually divide and provide care and consequently, cannot directly consider the interpersonal dynamics that underlie negotiations among adult children”.

There is some evidence of ways in which siblings are aware of each other in the caregiving process. In fact, siblings may provide care to a parent both to meet the needs of the parent, and to alleviate other siblings’ concerns with meeting those needs (Piercy 1998). Thus caregiving can include fulfilling a sense of responsibility not only to the older person, but also to one’s siblings. Caregivers may determine their own care contributions partly based on what their siblings are contributing (Checkovich and Stern 2002). When one sibling begins to provide assistance, the odds increase that other siblings will assume caregiving duties (Dwyer et al. 1992). In larger families, the shared nature of caregiving is evident as the amount of care provided by each sibling is less (Silverstein et al. 2008).

Can we assume then, that having a large number of children inevitably benefits both parents in need of care and their children? In situations of good will among siblings, the answer may be yes. Even lesser contributions to parent care by some siblings may be judged charitably as being grounded in “legitimate excuses” (Campbell and Martin-Matthews 2003; Connidis and Kemp 2008; Globerman 1995) so that family relationships remain harmonious.

Yet parent care also can create tensions among siblings if some are seen as refusing to accept responsibility (Harris 1998), providing insufficient amounts of assistance (Ingersoll-Dayton et al. 2003), or neglecting their obligations for shared responsibility for parent care (Lashewicz et al. 2007). Siblings who do less may be seen as shirking responsibilities with only “flimsy excuses” for their lack of involvement (Merrill 1997). As Davey and Szinovacz (2008, p. 155) note, “larger networks can entail considerable negotiation and re-negotiation of care responsibilities among network members. If such negotiations create conflict, this can contribute to caregiver stress and negatively impact patient [sic] outcomes”.

Clearly caregiving can be difficult. There is ample social gerontology research evidence of the costs of care. [See Fast et al. (1999), for a taxonomy of the domains of these costs]. Most of this research is based on a calculation of economic or social costs experienced by an individual caregiver (Haley 2003; Michelson and Tepperman 2003; van den Berg et al. 2006). Yet if we are to evaluate the question of whether having more sibling caregivers is an advantage, it is important to evaluate costs within a caregiving network of siblings and parent(s). Such an approach requires the consideration of multiple relationships among siblings and the older parent in need of care. Silverstein et al. (2008) argue that if we are to understand the dynamics of sibling relationships in caregiving, it is important to focus on the “maneuvering…that may precede the resolution of a care scenario as it is hashed out among siblings”.

Conceptual approach

To better understand sibling perspectives on equity in caregiving we draw on the assumption from choice and exchange theory that people evaluate costs and benefits of their own situation in comparison to the situations of others (Sabatelli and Shehan 1993). Calculations of costs and rewards are based on what individuals believe is deserved and/or realistically obtainable given previous experience with and understanding of their situation. Perceived imbalances in one’s costs and rewards compared with the costs and rewards of others are expected to cause distress in the form of resentment and anger for the under-benefitted and guilt for the over-benefitted (Walster et al. 1978; White and Klein 2002) Further, what is judged as costly or beneficial derives from the standards used to evaluate costs and benefits; standards differ between people and the extent to which something is evaluated as costly or beneficial will depend on where it is placed in an individual’s “hierarchy of values” (Nye 1979). The present examination is concentrated on what siblings regard as costly in their negotiation and navigation with each other over decisions about parent care and assets.

Siblings comprise a distinctly equivalent group who are keenly attentive to how their caregiving costs and benefits compare (Lashewicz et al. 2007) Research to date on sibling perspectives suggests that tensions among siblings arise from assessments by one or more siblings that others provide too little of the (presumably) costly work of care to a frail parent. Based on their equivalent genealogical relationship and shared filial obligation, one might expect that such evaluations are based on a belief caregiving is equitable if all sibs are actively involved.

Under-involvement of others is not the only source of tension among sibling caregivers. There may also be costs related to being excluded from care, since caregiving can bring benefits resulting from the relationship between more-involved sibs and the cared-for parent. The legal principle of “undue influence” provides an additional conceptual tool for understanding how high involvement in care may be seen to benefit one sibling to the determinant of others. Undue influence occurs when a vulnerable person is unfairly influenced by someone who is more powerful (Hall 2005). The legal interest lies with protection of the vulnerable person. However, within a choice and exchange framework, over-involved siblings might be viewed as benefiting unduly from caregiving through capturing parental attention to the exclusion other siblings from decision-making or financial benefit.

Evidence of such influence comes from research findings that adult children may dominate parent affairs. For example, in families where one sibling resides with an ageing parent in need of care, Cicirelli (1995) found that other siblings were troubled by the pre-eminence of decisions made by the co-resident caregiving sibling. More generally, siblings have expressed dissatisfaction at feeling excluded by others who maintain control over decisions pertaining to parents (George 1986). This seems to be a situation in which genealogically equivalent status raises expectations not only of obligations related to care but also of rights to influence the direction and outcomes of care.

An “over-involved” sibling may be seen as having unreasonable influence over their parent’s finances to the exclusive benefit of that sibling. A case in point is situations in which one sibling receives a disproportionate share of the estate of the parent as financial compensation for care. White-Means and Hong (2001) found that competition for parental bequests exists among siblings. Using a subset of data from the 1992 Health and Retirement Study the authors concluded that adult children are more likely to provide time and money to parents if they have siblings, the presence of whom was interpreted by adult children as competition for bequests.

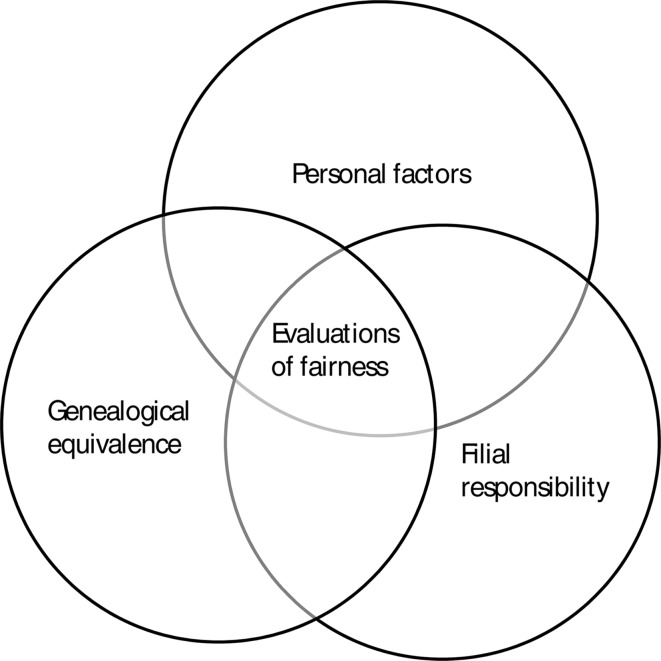

“The need to negotiate and navigate multiple relationships requires greater coordination of care and enhances opportunities for conflict over the allocation of caregiving responsibilities” (Davey and Szinovacz 2008, p. 133). Assumptions that larger sibling networks are better able to meet and manage parent care demands do not account for the complexity of sibling relationships including costs of conflict that may arise over sharing parent care. In examining these conflicts, including those depicted in legal data, we will further illustrate parts of caregiving family life distinguished by sibling competition and how this can impair caregiving capacities. Key elements of our conceptual approach to this examination are shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Conceptual approach

Methods

Following the narrative tradition that stories provide access to the richness of experience (Rosenblatt 2001), sibling stories of inequity in parent caregiving related to over-involvement of other siblings, were collected and analyzed. These data were gathered from two distinct sources. Legal case depictions of sibling claims that other siblings had unduly influenced an aging parent were collected. Legal cases provide descriptions that are narrowly focused by lawyers and judges in the interest of achieving a specific outcome in the form of a legal determination of whether a sibling unduly influenced a parent. A second source of data was collected through in-depth interviews with siblings who were in conflict with other siblings over decisions about their aging parent. These conflicts were not being pursued through legal channels and were described in first hand detail in a research interview. These two data sources offer stories told in two distinct styles to two different audiences and were brought together in an attempt to yield a more complete picture of tensions among caregivers. Interview data tend to provide fuller illuminations of processes involved as siblings negotiate and assume caregiving while legal data provide greater illustration of extreme forms of sibling conflict over decisions about ageing parents.

Legal cases

Six Canadian legal cases portraying claims by siblings that during the provision of parent care, other siblings exerted undue influence to obtain parent assets were studied. Claims of “undue influence” were selected for this study because they represent situations of over-involvement, depicting disputes specific to some sibling’s concerns that others had dominated decisions about their ageing parent. These six cases are part of a larger sample of eighteen cases which represent cases in Canada initiated between 1995 and 2004 profiling sibling disputes over the distribution of parent assets in relation to care that had been given. Legal case documents are compiled by judges and provide information about a family’s background and structure as well as the progression of the parent’s health status and need for care, including how these needs were met. This description provides context for the focal issue which is sibling disagreement about whether “over-involvement” lead to inequitable benefit from the distribution of parent assets. Compared to interview data, legal case data reflect beliefs that are presented in clear and unambiguous terms to constitute the facts of a case. Documents, including legal cases, can provide information about people and their interactions that is simply unreachable though other means (Berg 2004). Drawing upon legal case data allowed the incorporation of stories of such intense discord that the siblings involved would have been unlikely to agree to discuss their situations with a research interviewer.

Qualitative interviews

Data were drawn from in-depth interviews with a purposive sample of 11 adult siblings from 8 families in a major city in western Canada. Siblings interviewed were part of families with two or more siblings and were facing issues of giving parent care, receiving parent assets, and negotiating multiple relationships with sibs and their frail parent. Family groups with two or more siblings were recruited through a long-term care center, a wills and estates lawyer and a senior’s newsletter. In the interest of gaining as full a sibling perspective as possible, effort was taken to interview as many siblings from each family as were available and would agree to participate. Siblings offered detailed accounts of their experiences in response to questions about how parent care tasks and parent assets were distributed, whether the distribution was fair, and the bases on which fairness was evaluated. Compared with the legal case focus on asset distribution in the interviews, caregiving was focal with questions about asset distribution following in relation to the caregiving context. Siblings described care and asset sharing situations ranging from harmonious to highly conflicted. A subsection of this sample (five sibling perspectives from three of the eight families) is used here to provide accounts of tensions over some siblings dominating parent care and asset decisions. In two of these three families, only one sibling agreed to be interviewed given troubled relationships with other siblings. However, these two siblings elaborated their interviews by sharing records of written correspondence with their siblings in relation to parent care and asset decisions. In the third family, three siblings were interviewed.

These data sources provide illustrative examples of caregiving situations in which one sibling is seen as receiving undue benefit from their caregiving. The number of cases is small and cannot be considered representative of situations of over-involvement in care. However, they serve to expand our understanding of issues of equity among adult siblings.

Analysis

A content analysis of data from both legal cases and interviews was conducted by the first author using choice and exchange concepts of costs and rewards. Data were examined to determine what siblings considered as costs and rewards of sharing responsibility for care for their ageing parent and entitlement to parent assets. Drawing on the caregiving literature, filial responsibility, genealogical equivalence and personal factors were used as sensitizing concepts for this analysis. The data were studied for what siblings, as responsible equals, judge to be fair in how responsibilities and entitlements relative to ageing parents are shared and how the sharing of these is determined. The concept of undue influence was used to focus the analysis on the ways that the involvement of some siblings in parent decisions was restricted by the over-involvement of others.

Results

Siblings in this study expected to share parent care responsibilities and have equal opportunity for influence in matters of parent care and assets. They were dissatisfied when they perceived that others dominated decisions pertaining to parent care and assets. Two strategies to achieve domination were evident: separating the parent from other siblings, or preventing other siblings from being engaged in decision-making.

Separating the parent from other siblings

One source of sibling dissatisfaction with the dominating influence of other siblings was sibling beliefs that the dominating sibling had separated the parent from other siblings. “Dominating siblings” were viewed as gatekeepers who wished to control the amount and type of contact between their parent and siblings. The strategy of separating the parent from other siblings is particular to the legal case data. It is consistent with legal representations of sibling disagreements as centered on worry over the parent’s freedom of choice in accordance with the principle of undue influence. In the legal case data, the sibling who controlled access to the parent often was the one who gained most from the parent in terms of affection or assets and these siblings were seen as justifying their favored position with the parent. Those who felt excluded believed that the dominant sib was coloring the parent’s views and/or not treating the parent well.

A dramatic example is evident among the three siblings in the case of the Coughlan Estate (2003) which profiles a dispute between two sisters, Frances and Mary. At different times, each had provided live-in care to their father. Only Mary, who had more recently given live-in care, received assets from their father’s estate. Mary justified her own entitlement to their father’s assets by discrediting Frances’ involvement with their father. Mary claimed Frances had dominated their father by restricting his communication with Mary and isolating and controlling their father when he had lived with Frances including keeping him locked in his room. Mary’s claim was supported by the testimony of the third sibling, Bennet who called Frances a “forceful” person. Bennet also claimed that access to their father was restricted by Frances; for example, Bennet “tried to have a phone put in his father’s room, but Frances wouldn’t allow it”.

Similarly, in the case of Tracy and Boles (1996), two siblings, Katherine and Arthur, contested the distribution of their father’s estate in favor of a third sibling, Doris. Katherine and Arthur were distressed that their sister Doris, who lived in the apartment suite adjacent to the father’s suite, monitored his communication by having “connected his doorbell to a bell in her suite”. Katherine felt further restricted in her access to her father as she indicated that Doris insisted on being present during Katherine’s visits with their father. For her part, Doris claimed that her presence during her siblings’ visits to their father was motivated by her desire to help her father respond clearly to questions from Katherine or Arthur about plans he was making with Doris to relocate to western Canada.

Forced separation of some sibs from their parent is evident in the case of Simpson and Simpson (1997), which pertains to a maintenance agreement between the care-receiving mother and one son, Lloyd. The other three siblings, Alberta, Raymond, and Gordon, contested Lloyd’s receipt of the family home in exchange for caring for their mother which was outlined in the maintenance agreement. Their protest was based on their claims the maintenance agreement was not what their mother had wanted and that because of Lloyd’s influence, the mother was not free to fully discuss the situation with her other children. Alberta, Raymond, and Gordon all claimed that Lloyd had “tried to isolate (our) mother from the rest of the family” and submitted further that their efforts to discuss the particulars of the maintenance agreement with their mother were impeded by her refusal to speak about the agreement when Lloyd or his wife Marilyn was in the home. Alberta noted that she had asked their mother “what she was doing in the downstairs section of the house. Mrs. Simpson cried and pointed to the upstairs”. Gordon claimed that on another occasion, “My mother was quite apprehensive to talk about it; she was pointing up to the sundeck where Marilyn was hanging clothes, and she wouldn’t discuss anything personal about the house”.

The theme of siblings separating a parent from other siblings is evident in the case of Morgan and Lizotte (2003) where one sister viewed her sister as keeping other siblings separate by failing to disclose to her siblings that their mother had been hospitalized. In this case, two sisters from a family of eight siblings legally disagreed over the distribution of their mother’s estate. Both sisters had provided live-in care to their mother, and the dispute arose over the estate being left to one sister. Marylene, the sister who first lived with and cared for their mother, was given the mother’s home during her year of live-in caring. Ella, the sister who was second to provide live-in care, objected to Marylene’s receiving the property and claimed that Marylene had “taken advantage of her position of power and influence”. Ella protested the estate distribution partly on the basis that Marylene had obstructed the relationships between the mother and other siblings specifically by withholding information; Ella claimed that Marylene “did not reveal to her siblings that the property has been transferred to her nor did she reveal her mother’s hospitalization”.

On the surface, these family caregiving situations, brought to court over charges of undue influence, follow the usual focus on parent-child relationships. From that perspective, the main conclusion might be that undue influence is evident of a breakdown of the filial obligation that normally arises from a lifelong generational relationship. The same-generation lens used here reveals differential costs and benefits. Over-involved siblings benefit from capturing parental attention and financial assets, while excluded sibs lose the opportunity for either of these benefits. We know little from these cases about whether relationship tensions among these siblings are longstanding or emerged late in life, nor for whom the absence of close sibling ties is seen as a loss.

Preventing other siblings from being engaged in decisions

Data from interviews with caregiving siblings also illustrate situations in which one sibling is seen as receiving undue benefit from their caregiving. Here too, attention is directed to the siblings’ opportunities relative to each other. Preventing other siblings from being engaged in decisions was the main strategy evident in these data. In these cases, concerns with the dominating influence of siblings were expressed as beliefs that some siblings had made and acted on decisions in relation to parent care without inviting or allowing input from other siblings. Dominating siblings who acted without input were seen as righteous and uncompromising. Siblings who believed another sib had made decisions without their input sometimes retaliated by reversing their sibling’s decision without their sibling’s knowledge. This resulted in a tug-of-war style of sibling dynamic with each struggling to have influence over the parent and determine how the parent’s care needs would be met.

Joan who was interviewed from the Baker family conveyed distress over her only sister Linda’s failure to get her input regarding the sale of their parents’ home. According to Joan, Linda had single-handedly decided that the parents were no longer able to manage their own dwelling and that the home should be sold. Joan complained in a letter to Linda claiming “Big sister spoke… It was your way or the highway, right?” At another point in their correspondence about where their parents would live following the sale of their house, Joan referred to Linda having acted alone in making decisions for their parents and called her “Linda the Great!” At yet another point in their correspondence, Joan accused Linda of martyr behavior and sarcastically suggested, “Maybe you can pop Dad full of pills and drag him around the Oprah circuit”. Joan neither approved of, nor believed she could influence the ways in which Linda approached care and decision making in relation to their parents.

Further evidence of how Linda and Joan acted without each other’s input was provided as Linda described her disagreement with Joan, prior to the sale of the parents’ home, over their mother’s wish to return to living in the house after living independently in a small apartment for a period of time. Linda supported her mother’s wish and made arrangements for her mother to move back to the house. She states that on the day of the actual move, Joan “intercepted them, forced them to put everything back into Mother’s apartment…My sister had her children unpack everything back into her drawers, back into the closet, into her kitchen.”

Unequal sibling input also was pronounced in the Henry family. During his interview, Victor, one of six siblings, described how determining where his mother would live was a major issue for the siblings. The mother’s need for a supported living environment had been agreed upon. However, the size and location of the setting and the timing of the move were points of contention. One of Victor’s sisters, Paula, thought her mother’s need for a new living arrangement was immediate. Paula believed further, that she and other siblings had not had input into Victor’s decision that the mother’s current living situation was temporarily adequate. Paula issued a call to action to her siblings to override Victor’s decision saying, “Mom is unable to help herself and desperately needs our help…there is no time like the present. What are we waiting for?” Eventually, Paula and another sister, Karen, relocated their mother without the knowledge of two of the other siblings, Victor and Jack. Victor’s response to discovering that the move had taken place was to reverse the move without consulting Paula and Karen:

Paula moved Mom out of her house and didn’t tell me or Jack… So Mom was there three days, and I went in after my sister took her there. And then this memo came out explaining it all… So I went to see Mom there, and she told me she wanted to go home. And she said, “Well, you can give me a ride home.” So her suitcase was there; we just packed it up and left.

Data from these sibling interviews provide increased understanding of tensions among siblings over the right to influence the care of ageing parents. While the examples in these data are about decisions related to the care of the parent, the battles are fought in reference to siblings. The social exchange concept of “comparison level” is highlighted here. When the dominant sib is seen as being over-involved through making too may decisions, other sibs retaliate to recalibrate equity.

Discussion

Findings from this study suggest that we cannot accept at face value the assumption that having more children is an “obvious asset” for older adults in need of care. Larger groups involve a greater number of connections and thus greater potential for disagreement (Davey and Szinovacz 2008). As siblings negotiate their identities as participants in their parents’ later lives, their connections to each other are brought into focus. We applied a framework for understanding sibling connections by examining how siblings compare themselves in terms of filial responsibility, genealogical equivalence, and personal factors. Our findings indicate that within sibling groups negotiating care, the concept of filial rights may be as relevant as that of filial responsibility.

Our samples were chosen to allow for an exploration of sibling relationships. In legal and interview data, siblings spoke of unfairness in the sharing of parent care responsibilities. In both situations unfairness arose from perceived over-involvement leading to one sibling benefiting unfairly. Taking each other to court over inheritance may serve as a formal way for siblings to redress relationship problems beyond disagreements over inheritance. Overturning the caregiving decisions of others may be the continuation of unresolved issues related to sibling differentiation (Apter 2007). In both cases, ownership of responsibility for ageing parents (Globerman 1995; Lashewicz et al. 2007) was contested. This evidence sets the stage for continued deconstruction of assumptions about caregiver availability and constitutes a step towards fuller understandings of family dynamics beyond the caregiver–care receiver relationship. At the same time, the evidence compels us to consider negative outcomes for care receivers in the presence of tensions among their caregivers.

Since our data are cross-sectional, it is not clear whether potential financial gain from parental assets intensifies longstanding perceptions of inequity among siblings. Legal cases of undue influence are uncommon. Nonetheless, children of people now in advanced old age, likely have siblings. For them, unresolved issues of identity creation in relation to siblings may well come to the forefront in the intense situation of caregiving. Tensions over the right to influence caregiving decisions and outcomes warrant further exploration.

As we look to a future where people are living increasingly long lives we expect people to require more care as well as to have accumulated more wealth. The stakes for adult children as providers of this care and recipients of this wealth likely will increase and difficult sibling dynamics may increase correspondingly. Perhaps beanpole families, rather than simply having a reduced caregiver pool, will experience benefits of simpler negotiations inherent to smaller groups. Accordingly, larger sibling groups entail more potential within group connections both one on one and in other combinations; consequently, larger groups may be more susceptible to within group alliances such as the “two against one” scenarios depicted in the cases of Tracy versus Boles and the Coughlan estate, or the sisters against brothers divide in the Henry family. Compared with one on one disagreements, disagreements between “camps” that lead to groupings of siblings working in opposition to each other, will likely be more complex, difficult to resolve and detrimental to caregiving capacity. In all, the family care potential of older adults is likely to depend more on how negotiations are managed between their children than on having a large pool of children on which to depend.

Footnotes

Because the legal cases are part of public record, actual names are used in reporting and referencing these data. Pseudonyms were assigned to siblings from caregiving families who were interviewed.

References

- Apter T. The sister knot: why we fight, why we’re jealous, and why we’ll love each other no matter what. New York: W. W. Norton & Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Aronson J. Old women’s experiences of needing care: choice or compulsion? Can J Aging. 1990;9(3):234–247. [Google Scholar]

- Berg B. Qualitative research methods for the social sciences. Boston: Pearson Education; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Brannen J, Moss P, Mooney A. Working and caring in the twentieth century: change and continuity in our generation families. Basingstoke: Palgrave; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell LD, Martin-Matthews A. The gendered nature of men’s filial care. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2003;58B(6):S350–S358. doi: 10.1093/geronb/58.6.s350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checkovich T, Stern S. Shared caregiving responsibilities of adult siblings with elderly parents. J Hum Resour. 2002;XXXVII(3):441–478. doi: 10.2307/3069678. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cicirelli VG. Sibling relationships across the life span. New York: Plenum Press; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Conley D. The pecking order: which siblings succeed and why. New York: Random House; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA. Family ties and aging. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Connidis IA, Kemp CL. Negotiating actual and anticipated parental support: Multiple sibling voices in three-generation families. J Aging Stud. 2008;22(3):229–238. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2007.06.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coughlan Estate, Re (2003) Prince Edward Island Supreme Court. Retrieved 29 May 2004, from the LawSource database at http://ecarswell.westlaw.com

- Davey A, Szinovacz M. Division of care among adult children. In: Szinovacz ME, Davey A, editors. Caregiving contexts: cultural, familial and societal implications. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 133–159. [Google Scholar]

- Donorfio LKM, Kellett K. Filial responsibility and transitions involved: a qualitative exploration of caregiving daughters and frail mothers. J Adult Dev. 2006;13(3/4):158–167. doi: 10.1007/s10804-007-9025-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dwyer J, Henretta J, Coward R, Barton A. Changes in the helping behaviors of adult children as caregivers. Res Aging. 1992;14(3):351–375. doi: 10.1177/0164027592143004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fast J, Williamson D, Keating N. The hidden costs of informal elder care. J Fam Econ Issues. 1999;20(3):301–326. doi: 10.1023/A:1022909510229. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finch J, Mason J. Filial obligations and kin support for elderly people. Ageing Soc. 1990;10:151–175. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00008059. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gale W, Scholz K. IRAs and household saving. Am Econ Rev. 1994;84(5):1233–1260. [Google Scholar]

- Gans DS, Silverstein M. Norms of filial responsibility for aging parents across time and generations. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68(4):961–976. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00307.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- George L. Caregiver burden: conflict between norms of reciprocity and solidarity. In: Pillemer KA, Wolf RS, editors. Elder abuse: conflict in the family. Dover: Auburn House; 1986. pp. 67–92. [Google Scholar]

- Globerman J. The unencumbered child: family reputations and responsibilities in the care of relatives with Alzheimer’s Disease. Fam Process. 1995;34:87–99. doi: 10.1111/j.1545-5300.1995.00087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haley WE. The costs of family caregiving: implications for geriatric oncology. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2003;48(2):151–159. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2003.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MI. Equity and the older adult: the doctrines of undue influence and unconscionability. In: Soden A, editor. Advising the older client. Markham: Lexis Nexus Butterworths; 2005. pp. 329–339. [Google Scholar]

- Harris P. Listening to caregiving sons: misunderstood realities. Gerontologist. 1998;38(3):342–352. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.3.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hequembourg A, Brallier S. Gendered stories of parental caregiving among siblings. J Aging Stud. 2005;19(1):53–71. doi: 10.1016/j.jaging.2003.12.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ingersoll-Dayton B, Neal MB, Ha JH, Hammer LB. Redressing inequity in parent care among siblings. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65(1):201–213. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.00201.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karantzas GC, Foddy M, Evans L. Obligatory and discretionary motives of intergenerational caregiving. Aust J Psychol. 2003;55:49. [Google Scholar]

- Keefe J, Fancey P. The care continues: responsibility for elderly relatives before and after admission to a long term care facility. Fam Relat. 2000;49(3):235–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3729.2000.00235.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lashewicz B, Manning G, Hall M, Keating N. Equity matters: doing fairness in the context of family caregiving. Can J Aging. 2007;26(Suppl 1):91–102. doi: 10.3138/cja.26.suppl_1.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence JA, Goodnow JJ, Woods K, Karantzas G. Distributions of caregiving tasks among family members: the place of gender and availability. J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(4):493–509. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, Lizotte (2003) Nova Scotia supreme court. Retrieved 24 May 2004, from the LawSource database at http://ecarswell.westlaw.com

- Maser K, Dufour T (2001) Private pension savings, 1999. Perspectives on labour and income. Catalogue no. 75.001.XIE, Statistics Canada

- Merrill DM. Caring for elderly parents: juggling work, family, and caregiving in middle and working class families. Westport: Auburn House; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Michelson W, Tepperman L. Focus on home: what time-use data can tell about caregiving to adults. J Soc Issues. 2003;59(3):591–610. doi: 10.1111/1540-4560.00079. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nye FI. Choice, exchange, and the family. In: Burr WR, Hill R, Nye FI, Reiss IL, editors. Contemporary theories about the family: general theories/theoretical orientations. New York: The Free Press; 1979. pp. 1–41. [Google Scholar]

- Ohta M, Kai I. The cross-validity of the filial obligation scale. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2007;45(1):1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2006.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piercy KW. Theorizing about family caregiving: the role of responsibility. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:109–118. doi: 10.2307/353445. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ. Making choices: a within-family study of caregiver selection. Gerontologist. 2006;46(4):439–448. doi: 10.1093/geront/46.4.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Port CL, Zimmerman S, Williams CS, Dobbs D, Preisser JS, Wallace Williams S. Families filling the gap: comparing family involvement for assisted living and nursing home residents with dementia. Gerontologist. 2005;45(1):87–95. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.suppl_1.87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenblatt PC. Qualitative research as a spiritual experience. In: Gilbert KR, editor. The emotional nature of qualitative research. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2001. pp. 111–128. [Google Scholar]

- Sabatelli RM, Shehan CL. Exchange and resource theories. In: Boss PG, Doherty WJ, LaRossa R, Schumm WR, Steinmetz SK, editors. Sourcebook of family theories and methods: a contextual approach. New York: Plenum Press; 1993. pp. 385–411. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Conroy S, Gans D. Commitment to caring: filial responsibility and the allocation of support by adult children to older mothers. In: Szinovacz ME, Davey A, editors. Caregiving contexts: cultural, familial and societal implications. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 71–91. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson, Simpson (1997) British columbia supreme court. Retrieved 1 June 2004, from the LawSource database http://ecarswell.westlaw.com

- Sulloway F. Born to rebel: birth order, family dynamics, and creative lives. New York: Random House; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Tracy, Boles (1996) British Columbia Supreme Court. Retrieved 2 March 2004. http://www.courts.gov.bc.ca

- Turcotte M, Schellenberg G (2007) A portrait of seniors in Canada 2006. Ottawa, Statistics Canada

- van den Berg B, Al M, Brouwer W, van Exel J, Koopmanschap M, van den Bos GAM, Rutten F. Economic valuation of informal care: lessons from the application of the opportunity costs and proxy good methods. Soc Sci Med. 2006;62:835–845. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Pas S, van Tilburg T, Knipscheer KCPM. Measuring older adults’ filial responsibility expectations: exploring the application of a vignette technique and an item scale. Educ Psychol Meas. 2005;65(6):1026–1045. doi: 10.1177/0013164405278559. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walster A, Walster G, Berscheid E. Equity: theory and research. Boston: Allyn and Bacon; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Walz HS, Mitchell TE. Adult children and their parents’ expectations of future elder care needs. J Aging Health. 2007;19(3):482–499. doi: 10.1177/0898264307300184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White-Means S, Hong G. Giving incentives of adult children who care for disabled parents. J Consum Aff. 2001;35(2):364–389. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2001.tb00119.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Klein DM (2002) Family theories, 2nd edn. Sage, Thousand Oaks

- Wisensale SK. Aging societies and intergenerational equity issues: beyond paying for the elderly, who should care for them? J Fem Fam Ther. 2005;17(3/4):79–103. [Google Scholar]