Abstract

Promoting quality of life is a central theme in recent ageing policies, but what quality of life means in concrete terms for people in different stages of old age is rather unclear. This study presents a multi-dimensional model of care-related quality of life (crQoL) and, based on analyses of three Finnish cross-sectional datasets from the years 2004–2007, examines the distinctions between dimensions of QoL by age and gender, with a special focus on older home care clients. Correlation analyses (Pearson) and stepwise linear regression were applied to analyse variation in QoL by age group and the association between QoL and perceived quality of home care. The results suggest that individual QoL and the priorities of (physical, psychical, social, and environmental) dimensions in the assessment of QoL by older persons vary considerably and exhibit distinct profiles in different stages of ageing. In addition, four dimensions for good care corresponding to the crQoL model were identified and their empirical relevance demonstrated. From the perspective of older people in need of help, home care is not just about giving them the instrumental help they need to perform their daily activities, but rather about giving responsive care that reflects their personal preferences or their view on a “good life”, and treats them with dignity and respect. The criteria for the evaluation of quality of home care should reflect these insights, and policy measures should take these differences into account.

Keywords: Quality of life, Quality of home care, Old age, Client-centred evaluation

Introduction

Currently, there is an increasing agreement that we should know more about the variation in quality of life (QoL) between different groups of older adults, including frail older people receiving care. According to the literature, major components of good life quality in old age are broadly similar to those of adult populations in general, namely, good subjective physical and mental health, emotional well-being, sufficient financial resources, satisfying social relationships, social activity and a good living environment. But there are also differences between age groups with, for instance, health, functional capacity and mobility achieving much higher ratings among older than in younger age groups (Löwenstein and Ogg 2003; Bowling 2004; Brown et al. 2004; Mollenkopf and Walker 2007, Vaarama et al. 2008). That health and functional capacities decline with age, but life satisfaction does not or only little, is a well established finding, and has been interpreted as beneficial cognitive adaptation to changing life situations (Baltes and Baltes 1990; Cummins 1997; Felce and Perry 1997). Thus, there are differences regarding the relative importance of aspects or dimensions for achieving QoL. Moreover, the need for care, the quality of the care received, and the way care is evaluated as part of their life by older persons has to be considered as an essential feature of the life situation of older persons (Boumans et al. 2005).

The aim of this contribution, therefore, will be to discuss a concept of QoL in old age distinguishing different dimensions of QoL, and to present some empirical evidence showing that different groups—by age, gender and their life situation, especially with regard to receiving care—do vary in the way they appear to be maintaining their individual quality of life. Introducing a concept of care-related QoL (crQoL), an argument will be made for understanding care and subjective care quality as relevant aspects of the life situation of frail older persons. The contribution will proceed in three steps. First, a conceptual framework for the contribution will be presented as a model of care-related QoL, and the research questions specified. Second, a section on methods will briefly describe the data and methods employed, after which the results will be presented and discussed. Finally, some conclusions will round up the discussion.

The concepts of QoL and crQoL

A widely accepted definition or a compelling theory of QoL is missing as observed by many authors. While no single theory defines the field, the model of four dimensions of QoL in old age (functional competence, psychological well-being, social relations and environmental support) suggested by Lawton (1991), the idea of “successful ageing” (Baltes and Baltes 1990), the 5-dimensional (physical, material, social, emotional and productive well-being) model of Felce and Perry (1997), and the model of “the four qualities of life” of Veenhoven (2000) have been used in gerontological QoL research. Today QoL is understood as a dynamic multi-dimensional concept: it is generally agreed that it has both objective and subjective components, that it refers to a dynamic process varying considerably between individuals and over the life-course, and that it deals with a variety of positive and negative components with complex interconnections (Walker and Mollenkopf 2007).

While the major drivers of QoL are included in many taxonomies (e.g. Brown et al. 2004), the differences in different groups of older people (e.g. Bowling 2007) call for more differentiated analyses, including persons receiving help and care (Hellström et al. 2004; Vaarama et al. 2008). Regarding age as a point of differences, Lasslett (1996) introduced a division in the later life-course between the “third and fourth” age, suggesting that the “third age” (about 60–79 years old) is the time of self-realisation and full life, whilst the “fourth age” (about 80+) means moving to “traditional” old age with diminishing health and activity. Lasslet suggests a big difference between these two ages, and this assumption is supported at least in some degree also by Finnish research findings. Considering, for instance, the overall well-being of Finns 60+ since the year 1994 (Vaarama et al. 1999, 2006; Vaarama and Kaitsaari 2002; Vaarama and Ollila 2008), a comparison shows general improvement, which correspond with findings of a longitudinal study on Health in Finland (Koskinen et al. 2006). In comparison with persons 60+ in general, persons aged 80 years and more display lower physical, social and environmental well-being, but do not exhibit lower psychological well-being, or only slightly so. Also this observation is in line with previous research findings. However, another ongoing division of older people into two groups can be observed in Finland: the majority with increased health, functioning and overall well-being, representing mainly the “third” age group, and a smaller less fortunate group of persons in their “fourth” age. This leads us to ask for possible differences also in the priorities on how QoL is assessed in these two groups.

In comparison with other groups of older Finns, older home care (HC) clients are: usually in their “fourth age” (80+); live most often alone; face more often financial problems and problems with access to local amenities; experience more serious problems in performance of daily activities; suffer more often very disturbing daily pain; are less satisfied with their health; feel more often lonely; their subjective QoL is clearly lower; and they all are, by definition, dependent on formal home care. On the other hand, compared with their own age group (80+), HC clients seem to live in better adapted housing (maybe as a part of their care package); are still active in leisure and other activities at home (but less active outside home); and they are considerably more satisfied with personal relationships, although they would like to meet people within them more often. However, they feel lonelier (Vaarama et al. 2006; Vaarama and Ylönen 2006). In many cases, we find a co-production of QoL at home (Netten 2004) as the clients generally receive both formal and informal care.

Concepts and models of QoL in old age should, therefore, allow for distinctions according to age groups and dependency on care. Gerritsen et al. (2004) provide a useful review of a number of conceptual models of QoL of older people receiving care, notably Lawton (1983, 1991, 1994), Hughes (1990) and Ormel and et al. (1997). In these models, similar factors are considered: demographic and socio-economic factors, physical-functional abilities and mental health, personal and psychological factors, life satisfaction, social networks and participation, living environment, life changes and events, and care as relevant especially for the QoL of older persons living at home and in institutions. However, the role of care in production of QoL is seldom specified clear enough to allow for a systematic evaluation of the relationship between QoL in old age and care.

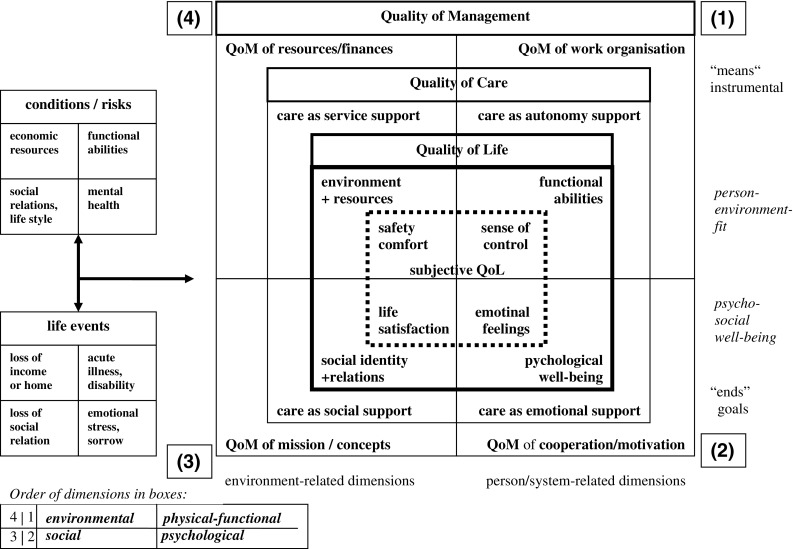

The European Care Keys-project 2003–2006 (Vaarama et al. 2008) focused especially on this relationship, and developed a model of “care-related QoL (crQOL)”, using Lawton (1991), Veenhoven (2000) and the approach of the WHOQOL Group (1998) as a base. The project also developed and tested measures for operationalisation of the theoretical model, on the condition that the measures were to be applicable for use with frail older people receiving care (see Vaarama et al. 2008). The model was designed to be a generic model specifying the general architecture of important dimensions, which then could be further differentiated by more specific aspects of the life domains of different groups—in the present context, especially, of care-dependent older persons of different age, gender and need of care. Furthermore, the model was to have a theoretical foundation clarifying the dimensional structure, integrating subjective and objective factors, and delineating the basic processes assumed to be involved in the achievement and maintenance of QoL. One of the processes—to which we will briefly return in the discussion—is resilience, referring to the capacities of the person to cope with diverse influences on their QoL, providing a kind of “inner resource” in managing everyday life with frailty (for more details see Pieper and Vaarama 2007). At the core of the crQoL model (Fig. 1) is the older person and his/her experience of life quality, divided into four dimensions (physical, psychological, social and environmental). These dimensions are then related to domains of capacities and resources regarded in previous QOL-studies as important for individual QoL. The next layer in the model specifies the role of care in supporting the subjective QoL of older clients. Following Bowers et al. (2001), the model distinguishes three approaches to care: care-as-comfort, care-as-relating, and care-as-service, but also a fourth approach of “care-as-autonomy support” is added to the model. These two layers are assumed to interact in the way that whenever there are deficits in one or more of the four dimensions of QoL by a person in need of care, care should aim at compensating these by offering help that is tailored according to the individual needs to maximize the QoL of the client. The degree of success in this compensation is, then, also a measure of quality (or effectiveness) of care. If all four care functions are fulfilled (and corresponding needs and preferences are met), care is regarded as being of “good quality”. Now a question arises, which type of care and what way of delivery is assessed as “good” in these terms.

Fig. 1.

Care-related quality of life: structural model (Pieper and Vaarama 2007)

Quality of care (QoC) is a rather diffuse concept, and can be approached from many perspectives. Vaarama et al. (2008) followed here the model of Jon Øvretveit (1998), differentiating three perspectives to care quality (the client, the professional, and the management), and approaching the quality as a chain of inputs, processes and outcomes. The approach is presented as a multi-dimensional matrix for evaluation of care quality. The evaluator is, in the first hand, the client her/himself, i.e. the subjective experience of the client is regarded as important and having its own value as nobody else can give this evaluation. With older persons, this is often either neglected by the argument that they do not have themselves enough knowledge to perform a reliable evaluation, or regarded as impossible due to the cognitive impairment. As this study is focusing on cognitively intact persons who can participate in interviews, this problem is not discussed here in greater length. It is just to be noted that, in the present study, care and care quality is only included as care perceived and evaluated by the client. In the empirical Care Keys research, both clinical/professional and subjective (perceived) quality of care appeared as essential components of QoL in older persons receiving formal care (Vaarama et al. 2008).

The two concepts of QoL and QoC were then integrated into a model of care-related QoL (crQoL). As Fig. 1 shows, the original model involves also the quality of care management, but it is not discussed here as it is outside of the scope of this contribution (for the model details, see Pieper and Vaarama 2007).

To summarise, the conceptual framework of this contribution considers the distinction between the “third and fourth age”, and the interaction between dimensions of quality of life and quality of care, where the assumption is that a “good” care aims at maximising the QoL of the client by responding to the individual needs the clients has in the four dimensions of quality of life. The present study involves the following elements or layers of the original Care Keys model (with numbers referring to corresponding dimensions in Fig. 1):

- Client-specific resources, risks and conditions for QoL, divided in four domains

- physical-functional

- psychological

- social

- environmental

- Subjective evaluation of quality of life in four dimensions

- physical-functional

- psychological

- social

- environmental

- Subjective evaluation of quality of professional care practices

- care as sustaining functional competence and autonomy

- care as supporting emotional and existential well-being

- care as supporting social identity, social relations and social participation

- care as providing appropriate interventions, comfort, support and continuity.

Then, research questions can be specified for the present study:

Do individual QoL and the priorities on how QoL is assessed by older persons vary in different stages of ageing (by age, gender, dependency on care)?

Does the subjective quality of care (QoC) play a significant role for QoL in older home care clients, and is it fruitful to analyse this role by structuring care quality in four dimensions corresponding with the four dimensions of quality of life?

Do the results support the four-dimensional model of care-related QoL?

Method

The following empirical evidence is based on three Finnish datasets from the years 2004–2007. They have used slightly different sampling methods, but each contains similar instrumentation, which makes comparisons possible. The empirical analyses employ frequency and correlation analyses (Pearson) and stepwise linear regression analysis.

Sample description

The first database is a representative sample (n = 1913) of Finns aged 60–96 years in the year 2004, taken from the national survey representing the population aged 18 years and more, carried out by the Finnish National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (Stakes). Data collection was carried out by Statistics Finland, which also added to the database some extra information, for example on income and household structure from public registers. The data on persons 18–79 years of age were collected in two stages: first by computer-assisted telephone interviews, after which the interviewed got a postal questionnaire for self-completion. The WHOQOL-instrument was included in the postal survey, so for the present study, for persons aged 60–79 years, the data is taken from persons who had also this scale completed (n = 669, female% = 55.9; mean age 68.1, response rate = 56.2%). For the age group 80+, the data is taken from the above mentioned face-to-face interviews (n = 390, female% = 67.0; mean age 83.9, response rate = 72.5%). The response rate in the postal survey was rather low, rendering possible rather explorative analyses.

Two other data are also cross-sectional, but collected in face-to-face interviews by trained external interviewers in two different Finnish cities, Espoo and Rovaniemi. The city of Espoo is located in the Helsinki region in Southern Finland. It has 239,741 inhabitants (768/km2), which ranks it as the second largest within the Finnish cities. The city has a fragmented area structure with many small city centres, of which most offer good access to a wide range of local amenities and events. The university city of Rovaniemi is the capital of Lapland, and a lively commercial, cultural and tourism centre. After 17 surrounding villages were joined in 2006, it is the 5th largest city in Europe in area terms (8017.23 km2), whilst the number of inhabitants is about 59,000 (8/km2). The city consists of an urbanised city centre (old Rovaniemi) and of surrounding villages, many of which have long distances to amenities and restricted access to transportation. Thus, the two municipalities have quite different conditions and contexts for the function of home care as a service for older people.

Both municipal level samples are random (master) samples of older home care (HC) clients. The Espoo data are from the year 2005 (n = 83; mean age 81; 75% women, MMSE score mean = 24; for MMSE see Folstein et al. 1975). Rovaniemi (ROI) data are from the year 2007 (n = 63; mean age 81; 73% women, MMSE score mean = 24).

Measures

In all these datasets, the WHOQOL-Bref scale furnished the collection of data on QoL. The WHOQOL-Bref scale measures QoL as a profile of a person’s satisfaction in four dimensions (physical, psychological, social, and environmental) with reference to different domains of his/her life, together with two general questions on perceived health and subjective “overall” experience of QoL (“How would you rate your QoL?”). In the present study, the four domains are interpreted to represent the four conceptual dimensions of the Care Keys QoL model. Currently, the WHOQOL-instrument (Skevington et al. 2004) is increasingly used for the measurement of QoL within gerontology (for criticism see, e.g. Rapley 2003). Bowden and Fox-Rushby (2003) evaluated the instrument as the most multi-facetted and leading to most reliable conclusions. Bowling (2007) evaluates the WHOQOL-OLD (Power et al. 2005) as most comprehensive scale for use with older persons in comparison with seven other measures, but it was not yet available in the year 2003 when the first studies discussed here were launched (and it is currently still in field-testing). To ensure the comparability between the national and home care surveys discussed here, a slightly modified version was used, where the question 18 (capacity to work) was replaced by satisfaction with ability to perform activities of everyday life, and the question 21 (satisfaction with sex life) was replaced by a question on loneliness. The decision was based on the piloting results of the European Care Keys research, where these two questions turned to be problematic in use with frail older people (Tiit et al. 2008). The reliability of this modified WHOQOL-Bref -scale was satisfactory (Ch. Alpha 0, 62).

To measure psychological well-being of the respondents, and as an alternative QoL measure, the Philadelphia Geriatric Centre Moral Scale (PGCMS; available at Lawton 2003) was used. The PGCMS-scale combines the aspects of agitation, attitude toward own ageing, and lonely dissatisfaction, and it is considered to measure morale, a concept that involves satisfaction with life and orientation toward future. The maximum score value is 17, and values 9 and lower indicate low QoL. The reliability of this scale was rather good (Ch. alpha 0, 72).

Other instrumentation covers care and diverse variables of resources, needs, risks and conditions for individual QoL: background variables (age, gender, marital status, living alone, cohabitation (with whom the client cohabits); physical-functional ability (subjective health and IADL/ADL-problems); social well-being (variables characterizing social networks, existence of close persons, frequency of contacts, participation in leisure activities, hobbies or activities enjoyed outside home/at home, traumatic life events (death of spouse, serious illness of client or his/her close relation, serious financial problems); physical environment (house/flat ownership, problems with heating, dump, missing lift, difficult stairs, barriers to indoor and outdoor mobility, distance to transport and local amenities); formal help received; and sources of other help (help from spouse, children, friends, paid nurse, church, volunteers). To capture the influence of care on QoL in care-dependent older people, the instrumentation developed in the Care Keys research for measurement of perceived quality of care was used for data collection in Espoo and Rovaniemi (see Tiit et al. 2008). It measures the “goodness of care” subjectively as perceived by clients in four dimensions corresponding to the QoL model: realisation of client autonomy, control and choice (D1); quality of personal interaction between client and care workers (D2); treatment with dignity and respect and giving social support (D3); appropriateness and continuity of care (D4), with an additional question on the “overall” satisfaction with care (the items are contained in Table 4). Most of these measures are incorporated into the Care Keys client interview instrument CLINT, with own versions for home care and for care in institutional settings (see Vaarama et al. 2008).

Table 4.

Significant correlations between QoL-resources of older homecare clients and the WHOQoL-Bref dimensions in Espoo (2005) and Rovaniemi (2007)

| Variable | ESPOO (n = 83) | Rovaniemi (n = 63) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | Overall | D1 | D2 | D3 | D4 | |

| Subjective QoL variables | ||||||||||

| Positive attitude toward ageing ATOA | 0.378** | 0.544** | 0.282* | 0.444** | 0.622** | 0.456** | 0.489** | 0.325* | 0.381** | |

| Subjective financial problems | −0.317** | −0.233* | ||||||||

| Good subjective health | 0.245* | 0.520** | 0.456** | 0.691** | 0.561** | 0.458** | ||||

| Perceived quality of care/satisfaction with care | ||||||||||

| Autonomy support (care dimension 1) | ||||||||||

| Care workers are good at what they do | 0.268* | 0.339** | 0.324* | 0.272* | 0.360** | |||||

| Care workers give enough information about care | 0.337** | 0.245* | 0.299** | |||||||

| Client gets to eat at the times that suit for him or her | 0.290** | |||||||||

| Interaction quality/emotions (care dimension 2) | ||||||||||

| If client raises concerns, does he or she feel that care worker listens | 0.278* | 0.330* | ||||||||

| Care worker is kind | 0.236* | 0.397* | 0.307* | |||||||

| Client enjoys meals | 0.357** | 0.268* | ||||||||

| Social support (care dimension 3) | ||||||||||

| Care workers have a good understanding of client and client’s needs | 0.278* | 0.338** | ||||||||

| Care workers treat client with dignity and respect | 0.233* | 0.289** | 0.312* | 0.349** | ||||||

| Client mainly see same care workers | 0.278* | |||||||||

| Appropriateness of care (care dimension 4) | ||||||||||

| Care workers do the things that the client wants to be done | 0.378** | 0.247* | 0.380** | |||||||

| Care workers deliver the services as promised | 0.268* | |||||||||

| Care workers have enough time for the client | 0.421** | 0.382** | 0.292* | 0.276* | 0.273* | |||||

| Client’s home is as clean and tidy as he or she would like | 0.335** | 0.427** | 0.253* | 0.374** | 0.385** | 0.357** | 0.518** | |||

| Client able to keep as well dressed as he or she would like | 0.278* | 0.451** | 0.370** | 0.307* | ||||||

| Client is able to keep as clean as he or she would like | 0.307** | 0.242* | ||||||||

| Client would recommend service for others in need of help | 0.251* | |||||||||

| Overall satisfaction with care | ||||||||||

| Client is satisfied with the home care he or she receives | 0.357** | |||||||||

D1 physical-functional, D2 psychological, D3 social, D4 environmental WHOQOL-Bref

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01

Results

Following the first research question stated above, the relationships between the dimensions of QoL and age were analysed. For the survey of Finns aged 60+, a number of variables which—following the model—may be grouped into the four dimensions are correlated with the dimensional WHO-scores (Table 1). The negative correlations between age and physical and psychological dimensions indicate that especially these resources decrease with age, and the negative relations of QoL dimensions to illness, problems with daily activities, living alone, poor access to amenities, and social inactivity reflect this development. Sufficient help when in need, and satisfaction with help are important, whilst the source of help (public, private, family) is not. Vaarama and Kaitsaari (2002) found a similar pattern concerning satisfaction with life in Finns aged 60+ in the year 1998, but the present observation of rather strong positive relation between appropriateness of the received help and the (WHO)QOL dimensions (except the social dimension) is new. Interesting is also the general pattern: the strongest relations tend to appear on the diagonal relating corresponding dimensions; the pattern is not so pronounced in the social and environmental dimensions. The environmental dimension shows a significant influence of health problems (which is apparent in the effects of subjective health), resulting in problems of mobility and access. The psychological dimension was measured additionally by the PGCMS and, while its strongest relations are expectedly with the psychological score, especially a positive attitude toward one’s own ageing shows a strong relation across all dimensions.

Table 1.

Pearson correlations between age, living conditions, and well-being indicators, ordered by dimensions

| WHO physical | WHO psychological | WHO social | WHO environment | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | −0.262** | −0.113** | −0.056 | 0.023 |

| Traumatic life changes during past 12 months | −0.034 | 0.012 | 0.048 | 0.058 |

| Physical-functional dimension | ||||

| Education (ISCED97 1-number level) | 0.197** | 0.089** | −0.009 | 0.184** |

| Subjective health | 0.604** | 0.460** | 0.228** | 0.456** |

| Need of help in ADL-activities/health care | −0.372** | −0.194** | −0.091** | −0.192** |

| Feeling of self-efficacy | 0.476** | 0.353** | 0.186** | 0.343** |

| Active in sports | 0.416** | 0.196** | 0.093* | 0.195** |

| Use of intramural hospital care during the past 12 months | −0.163** | −0.073 | 0.034 | −0.105* |

| Visited hospital polyclinics during past 12 months | −0.159** | −0.085* | −0.052 | −0.072* |

| Psychological dimension | ||||

| Positive attitude toward own ageing (PGCMS) | 0.486** | 0.517** | 0.255** | 0.425** |

| Less lonely (PGCMS) | 0.378** | 0.379** | 0.210** | 0.329** |

| Less agitation (PGCMS) | 0.259** | 0.328** | 0.132** | 0.222** |

| Feeling of self-determination | 0.209** | 0.209** | 0.169** | 0.203** |

| Feels not bored | 0.170** | 0.228** | 0.143** | 0.147** |

| Social dimension | ||||

| Intensive social relationships | 0.032 | 0.063 | 0.180** | 0.096* |

| Lives alone | −0.137** | −0.133** | −0.132** | −0.059 |

| Gives regular informal help/care to someone close | 0.038 | 0.002 | 0.020 | −0.010 |

| Environmental dimension | ||||

| Net income | 0.237** | 0.162** | 0.093** | 0.171** |

| Need of help in IAD-activities | −0.560** | −0.306** | −0.132** | −0.291** |

| Poor access to services and amenities | −0.253** | −0.085 | −0.011 | −0.388** |

| Barrier-free flat/house | 0.245** | 0.173** | 0.111** | 0.202** |

| Uses regularly formal home care | −0.099 | 0.068 | −0.055 | −0.049 |

| Receives informal help from family | 0.094 | −0.016 | 0.090 | −0.027 |

| Uses private care services | 0.003 | −0.061 | −0.044 | 0.091 |

| Gets enough help in right things | 0.266** | 0.205** | 0.143 | 0.362** |

| Satisfied with help received | 0.290** | 0.150 | 0.073 | 0.414** |

Finns aged 60+ in 2004 (n = 1059)

** P < 0.01, * P < 0.05

A further, and rather explorative analysis on the priorities (measured in the WHOQOL-Bref items) on how QoL is assessed by individuals aged 60–96 years show remarkable variation in different stages of ageing according to their chronological age (Table 2). The youngest age group in the analysis (60–64) represents mainly quite newly retired persons in the beginning of their “third age” (average retirement age in Finland in 2004 was 59). The second group (65–79) represents older adults in more advanced stage of their “third age”, and the third group (80+) consists of persons in their “fourth age” (Lasslett 1996).

Table 2.

Subjective (“overall”) QoL and items from WHOQOL-Bref dimensions

| WHOQoL-variable | Overall QoL (50–64) |

Overall QoL (65–79) |

Overall QoL (80+) |

WHOQOL |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beta coefficient | Beta coefficient | Beta coefficient | Dimension | |

| Enjoys life | 0.2477*** | 0.1694*** | 0.2060*** | Psychological |

| Anxiety, depression, blue mood | −0.1424** | Psychological | ||

| Satisfied with self | 0.0848** | Psycho-social | ||

| Satisfied with own health | 0.0886* | 0.1332*** | Physical | |

| Good mobility | 0.1574*** | Physical | ||

| Satisfied with daily I/ADL-performance | 0.0724* | Physical | ||

| Enough energy for everyday life | 0.1060* | Physical | ||

| Disturbing daily pain | −0.1251** | −0.0681** | Physical | |

| Able to concentrate | 0.1104** | Psychological (phys.-cognitive) | ||

| Satisfied with help from friends | 0.1486*** | 0.0521* | Social | |

| Enough money | 0.0872** | 0.1153*** | Environmental | |

| Satisfied with access to health care | 0.0716** | Environmental | ||

| Satisfied with access to leisure activities | 0.1001*** | Environmental (social) | ||

| Enough information about issues important for everyday life | 0.1014** | Environmental | ||

| n | 265 | 404 | 390 | |

| R 2 | 0.491 | 0.546 | 0.397 |

Finns aged 60–96 years. Stepwise linear regression analysis (n = 1059)

* P < 0.05, ** P < 0.01, *** P < 0.001

From the results, three observations can be made. First, the item “enjoys life” has influence over all ages. Second, the youngest group shows an even distribution of items from all four dimensions. The middle group shows a special relevance of physical-functional items, whilst the oldest group displays a special emphasis on items of psychological well-being. The social dimension is, unfortunately, not very well represented in the study, but indicates an importance in all age groups. Third, it is interesting to note the relative importance of specific environmental items.

When looking at the distribution of WHOQOL-Bref mean scores in more refined 5-year age groups, the results show a quite stable evaluations of individual QoL across dimensions and over the different age groups, especially in the psychological and environmental dimensions, with the physical and social dimensions tending to decrease after age 80 (Table 3). Using a 10-point difference in score value as the criterion (Osoba et al. 1998), significant differences can be observed only in physical and social dimensions.

Table 3.

Means of WHOQOL-dimensions in Finnish population aged 60–96 (n = 1059) by age and gender (2004), and in older home care (HC) clients in Espoo (2005, n = 83) and Rovaniemi (ROI 2007, n = 63)

| WHOQoL domain | FIN (60–64) |

FIN (65–74) |

FIN (75–79) |

FIN (80–84) |

FIN (85+) |

Espoo HC (Mean age 81) |

ROI HC (Mean age 81) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| D1 physical | M | 74 | 72 | 69 | 62 | 61 | 61 | 57 |

| F | 73 | 72 | 67 | 65 | 58 | 51 | 57 | |

| D2 psychological | M | 67 | 68 | 67 | 65 | 65 | 59 | 62 |

| F | 65 | 67 | 63 | 63 | 62 | 59 | 62 | |

| D3 social | M | 70 | 73 | 75 | 70 | 62 | 80* | 69 |

| F | 75 | 76 | 73 | 62 | 63 | 80* | 78 | |

| D4 environmental | M | 68 | 69 | 70 | 73 | 72 | 78 | 71 |

| F | 70 | 70 | 68 | 70 | 68 | 66 | 71 | |

* No data by gender available in the present study

The results also prompt interesting observations on differences between genders and groups. In the physical dimension, a more significant drop occurs for males at the age of 80–84, but for females after the age of 85 years, and women drop from a higher level. In the social dimension, the drops occur in reverse order, and again females drop from a higher level. The age 80+ seems to be an important divider in QoL as, at this age, both genders seem to face increasing decline in their QoL, but in a different way.

Following the second research question, the role of home care and care quality was analysed by comparing older Finns in general with the two different groups of HC clients (Table 3). First observation is a continuously high satisfaction with the environmental dimension, with even slightly rising importance for males, especially among the male HC clients in Espoo. Second, a comparison of the HC clients with their own age group (80+) shows that physical and psychological dimensions get lower but not significantly lower score values in HC clients, but—somewhat surprisingly—the social dimension shows significantly higher values, especially in older women. Further, the dimension “social” improves and “environmental” remains high whilst, especially, “physical” declines in the HC clients. Third, a comparison among HC clients shows high gender differences in physical and environmental dimensions in Espoo, and in the social dimension in Rovaniemi.

Focusing on the effects of perceived quality of care (QoC), Table 4 illustrates the interplay between the QoC variables and QoL dimensions. Significant correlations can be observed in all dimensions. Overall QoL shows significant correlations with all care dimensions in Espoo. Most often the QoC items correlate positively with overall QoL evaluation and with the environmental dimension. Again, strong relations in the diagonal of the tables for both Espoo and Rovaniemi can be observed. But the pattern shows also that all four dimensions of QoC and QoL are interacting, and the way the professionals interact with the client in practical care delivery to meet their needs has a strong impact on QoL of the clients. Finally, there are strong positive correlations between attitude towards one’s own ageing (ATOA, factor of the PGCMS-scale) and QoL dimensions.

Discussion

Focusing on the first research question, the WHOQOL-Bref sum scores suggest the subjective QoL to be quite stable across dimensions and over the different age groups. This holds especially in the psychological and environmental dimensions, with the physical and social dimensions tending to decrease after age 80. Considering the relative stability of the psychological dimension, its relative importance can be assumed to increase along the losses in physical and social dimensions. The results also prompt interesting observations on differences between genders and groups: physical decline may have an earlier impact on well-being of males, but the impact is more dramatic in oldest women. In the social dimension, the drops occur in reverse order, and again females drop from a higher level. This might be explained by the likely experience of the loss of the partner (who tends to be older and having a lower life expectancy). The observations suggest the age of 80+ to be an important divider in QoL. In supporting QoL of persons aged 80–84, the priority in males seems to be on physical and in females on social support, and vice versa after 85+ (even at this age, both support forms are necessary for both genders).

The analyses on variation of the individual QoL and on the priorities of dimensions in the self-assessment by older persons show considerable variation in the different stages of ageing. Whilst the item “enjoys life” has influence over all ages, and can be seen as a proxy to QoL in general, the different importance of the dimensions between the age groups is interesting. The youngest group shows an even distribution of items from all four dimensions, and the items the regression model selected regarding subjective health, social relations and financial situation are in general in accordance with previous QoL research. The items which differentiate this group from others are the importance of having enough energy and information for daily living. This cannot be explained in any depth with the variables included in the present study but the finding needs further research. However, it may be allowed to assume that the results are connected with the especial life situation of quite recently retired persons in the process of substituting the role of active workforce by a role of retired person, in the situations where they more and more often are still having all the capacities and also willingness to work. In Finland, there are a lot of expectations that people would continue their working careers longer, until their 65–68 years of age. If this is to be achieved, more research about the factors they consider as important for their QoL is also needed.

The middle group shows a special relevance of physical-functional items reflecting the increasing relevance of health issues and the need to adjustment in this dimension. This may well reflect the situation of people in their advanced “third age”, where the physical symptoms of ageing start to show up and increase, raising—if not worries—at least growing interest in their own health, memory and mobility. For this group, good access to health care is important, but the results also points to a great potential to prevention and self-help, the realisation of which calls for access to appropriate means. The oldest, 80+ group, displays a special emphasis on items of psychological well-being, suggesting that this dimension is especially relevant for their overall QoL. The social dimension is, unfortunately, not very well represented in the study, but indicates an importance in all age groups.

It is also interesting to note the relative importance of specific environmental items: money and information are general resources in the younger group corresponding to a broad scope of activities; in the middle the importance of health care dominates with endangered or restricted options; in the oldest group the leisure activities—closest to psycho-social needs—appear as relevant mirroring the necessity to find life satisfaction “within close reach” to keep “life in years”.

Focusing on the role of care, the rather strong positive relation between appropriateness of the received help and the (WHO) QoL dimensions (except the social dimension) points to the importance of care in shaping QoL in later life. First, the high satisfaction with the environmental dimension, with even slightly rising importance for male homecare clients presumably reflects the role of HC (environmental dimension includes care), indicating the importance of tangible help in everyday life with declining physical well-being. This, together with the finding that HC clients live in better adapted housing may refer also to a good “person-environment fit” (Lawton 1991; see also Oswald and Wahl 2005).

Second, that physical and psychological dimensions get lower but not significantly lower score values in HC clients, but the social dimension shows significantly higher values, especially in older women may indicate that home care is not only important source of tangible help but also of social well-being, and it presumably substitutes lacking social relationships of the clients. This corresponds to the assumption on the relational nature of care suggested in the crQoL model. Further, that dimension “social” improves and “environmental” remains high whilst especially “physical” declines in the HC clients, may refer to a shift in priorities to maintain QoL, suggesting that HC can support this beneficial adaptation. Also Vaarama and Tiit (2008) found that HC which responded well both to the instrumental and relational needs of the clients was able to increase their QoL, and the way care professionals interacted with clients was very important (see also Larsson et al. 1998).

Third, a comparison among HC clients shows high gender differences in physical, environmental and social dimensions. The difference in physical health between males and females in Espoo suggest that men receive HC in better physical condition than women, and they also seem to perceive the service quality as better. Unfortunately the score values in social dimension in Espoo were not available by gender. In Rovaniemi, male clients get almost significantly lower scores in social dimension than females, and somewhat lower values than in Espoo. The result indicates differences in the quality of HC in these two cities.

Considering the effects of perceived quality of care (QoC) on QoL, significant correlations were observed in all dimensions. Overall QoL showed significant correlations with all care dimensions in Espoo, speaking for a strong role of care in shaping subjective QoL of older HC clients in this city. That the QoC items correlated positively with the environmental dimension supports the conceptualisation of care as belonging to this dimension. The strong relations in the diagonal of the tables for both Espoo and Rovaniemi indicate that qualities of care addressing a corresponding dimension of QoL have a corresponding higher effect; this speaks for the “enrichment” of the model by a “layer” of care in a crQoL model. But the pattern showed also that all four dimensions of QoC and QoL are interacting.

Another important observation is that social well-being in older HC clients seem to be co-produced by the client and care worker, and the way the professionals interact with the client in practical care delivery to meet their needs seems to have a strong impact on QoL of the clients. It is of interest for future research to explain the dynamics of this production function. That in the present study the pattern was weak in Espoo but strong in Rovaniemi may be explained by the observations that in Rovaniemi, loneliness was twice as common as in Espoo; there were clients (usually older women) who had nobody visiting them during the 2 weeks prior to the interview. Further, every third person nominated care workers as their close ones (no one in Espoo), and 65% experienced unmet needs in respect to support for participation in social activities. Further, clients in Rovaniemi perceived the qualities of interaction with care workers poorer than was the case in Espoo, reflected in that they felt not to get enough time from the care workers, who “change too often, do not listen to them and only seldom understand their problems”. The care workers in Rovaniemi seem to face high expectations from clients to substitute their often missing social relationships. This is reflected in their case by the fact that all four dimensions of QoC have a significant impact on the social dimension rather than only the social support as in the case of Espoo. Lonely clients could benefit from more psycho-social rehabilitation and activation, but also from getting more time and attention from the care workers.

The results indicate a great potential for home care in contributing to the QoL of the clients. Home care that provides both tangible help and psycho-social support may achieve this goal. Older clients seem to expect more from formal HC than just instrumental support, as also Bowers et al. (2001) and Vaarama and Tiit (2008) suggest. A positive message of the result is that by doing good work in one dimension, HC may improve QoL also in some other dimension, which is an important message for improvement of the effectiveness of home care.

Focusing on the third question, the results support the suggested crQoL model. High inter-correlations between QoL as measured by WHOQOL-Bref and other variables including care, and grouped in corresponding dimensions, formed a pattern supporting an age-adapted model of crQoL. Also the general pattern that the strongest relations tended to appear on the diagonal relating corresponding dimensions was remarkable. The pattern was not so pronounced in the social and environmental dimensions. The reasons may be that social variables are underrepresented in the WHOQOL-Bref measure, and the items also may not capture the content very well, or they may be due to the modified version of the scale used in this study. However, as also Vaarama et al. (2008) have noted, the WHOQOL-Bref instrument has a structural imbalance with a tendency to underrate the social dimension in QoL (physical 7 items, psychological 6 items, social 3 items and environment 8 items), and assignment of items to dimensions is not always clear. This raises the question whether the definition of the items in the scale, especially those of the social dimension, should be improved. Additionally, a 4-dimensional model was produced for each age group (again, except for the social dimension, but the measurement of this dimension may be insufficient). Thus, it may be claimed that the model offers a common framework to study and compare QoL in different ages and different stages of old age. However, more refined analyses are necessary for further validation of the model and its measures.

Interestingly, there were strong positive correlations between positive attitude towards one’s own ageing (ATOA, factor of the PGCMS-scale) and QoL dimensions, raising the interesting question whether this deals with resilience, i.e. whether ATOA does reflect an “inner resource” for QoL that helps in adjusting to life with advanced age. The results show ATOA to be important for QoL both for persons with and without care. Vaarama and Tiit (2007, p. 186) found that a set of quality of care variables explained 17% of the variation in ATOA, and ATOA was—after subjective health—the most powerful single item in explaining variation in QoL in older HC clients. This suggests that care of certain qualities can support ATOA. It is an interesting topic for the future research whether the relationship between ATOA and QoL is meaningfully interpreted in the model as resilience, and whether it may also be captured in a 4-dimensional framework.

Furthermore, analyses support the integration of a 4-dimensional model of care as relevant “layer” into the crQoL model. The pattern of relationships between dimensions of quality of care (QoC) and QoL demonstrated that care dimensions had a relationship to corresponding QoL dimensions. The results confirm previous explorations on QoL in older HC clients by Vaarama et al. (2008), showing the existence of major drivers in all four dimensions of the proposed crQoL model. The results derived from the three present datasets align with the results of previous studies, and support the usability of the proposed 4-dimensional model.

Conclusion

The aim of this contribution was to study whether the individual QoL and its constituents vary in different stages of ageing by age, gender and dependency of care; to examine the role of subjective care quality in shaping the QoL in older home care clients; and to propose a 4-dimensional model of care-related QoL as a framework to study QoL of care-dependent older people. The study focused on people aged 60–96 in Finland, some of whom received formal home care. The analyses were original analyses from one national and two local Finnish datasets from the years 2004–2007. The major thrust of the argument was that a differentiated multi-dimensional approach to QoL is needed as: (a) individual QoL and the priorities on how it is assessed vary considerably and are distinct in different stages of ageing; and (b) for QoL of care-dependent older persons, the quality of care plays an important role.

Enjoying life is the most important overall resource for good QoL in all observed age groups, but for persons aged 60–64 years, similar priorities as for active persons in general are important, and this is important message for policies aiming at keeping older persons longer in the working life. In the more advanced “third age” (65–79), good access to health care is important, but also preventive and self-help measures are needed. In the “fourth age” (80+), appropriate care and help is necessary, but also the psycho-social dimensions of QoL needs more attention. However, it is important to recognise that the differences are not only between the “third age” and the “fourth age”, but also within the age groups.

From the perspective of older people in need of help, home care is not just about giving them the instrumental help they need to perform their daily activities, but rather it is about giving responsive care that reflects their personal preferences or their view on a “good life”, and treats them with dignity and respect. This way, care may be able to support the older clients to keep a positive attitude towards their own ageing (ATOA), which may be interpreted as resilience, an “inner” resource for QoL that helps in adjusting to life with advanced age. The criteria for the evaluation of quality of home care should reflect also these insights.

The results are based on small cross-sectional datasets, so they have to be seen as explorative, and further research with larger databases, preferably with longitudinal designs, are necessary to better understand the variations in individual QoL across the later life-course. However, the research findings indicate a need for more differentiated policies to support well-being of older persons in different stages of ageing, and measures should be tailored to meet the risks and to find the potentials at each stage.

References

- Baltes PB, Baltes MM. Psychological perspectives on successful aging: the model of selective optimization with compensation. In: Baltes PB, Baltes MM, editors. Successful aging. Perspectives from the behavioural sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Boumans N, Berkhou A, Landeweerd A. Effects of resident-oriented care on quality of care. Well-being and satisfaction with care. Scand J Caring Sci. 2005;19:240–250. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2005.00351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowden A, Fox-Rushby JA. A systematic and critical review of the process of translation and adaptation of generic health-related quality of life measures in Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East, South America. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57:1289–1306. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(02)00503-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowers BJ, Fibich B, Jacobson N. Care-as-service, care-as-relating, care-as-comfort: understanding nursing home resident`s definition of quality. Gerontologist. 2001;41(4):539–545. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.4.539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. Measuring health: a review of QoL measurement scales. 3. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Bowling A. Quality of Life in older age: what the older people say. In: Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age. International and multi-disciplinary perspectives. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 15–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brown J, Bowling A, Flynn T (2004) Models of quality of life: a taxonomy and systematic review of the literature. FORUM Project, University of Sheffield, Sheffield. Available via http://www.shef.ac.uk/ageingresearch

- Cummins RA. Assessing QoL. In: Brown RI, editor. QoL for people with disabilities. Models, research and practice. Cheltenham: Stanley Thornes; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Felce D, Perry J. Quality of life: the scope of the term and its breadth of measurement. In: Brown RI, editor. Quality of life for people with disabilities: models, research and practice. London: Stanley Thornes; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Folstein M, Folstein S, McHugh P. Mini mental state a practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. J Psychiatr Res. 1975;12:187–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerritsen D, Steverink N, Ooms M, Ribbe M. Finding a useful conceptual basis for enhancing the quality of life of nursing home residents. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:611–624. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000021314.17605.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hellström Y, Persson G, Hallberg IR. Quality of life and symptoms among older people living at home. J Adv Nurs. 2004;48:584–593. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03247.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes B. Quality of life. In: Peace SM, editor. Researching social gerontology: concepts, methods and issues. London: Sage; 1990. pp. 46–58. [Google Scholar]

- Koskinen S, Aromaa A, Huttunen J, Teperi J (eds) (2006) Health in Finland. National Public Health Institute (KTL), National Research and Development Centre for Welfare and Health (Stakes) and Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. Vammalan Kirjapaino, Helsinki

- Larsson G, Wilde Larsson B. Quality of care: relationship between the perceptions of elderly home care users and their caregivers. Scand J Soc Welf. 1998;7:262–268. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2397.1998.tb00289.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lasslett P. A fresh map of life. The emergence of the third age. 2. London: Macmillan; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Environment and other determinants of well-being in older people. Gerontologist. 1983;4:349–357. doi: 10.1093/geront/23.4.349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. A multidimensional view of quality of life in frail elders. In: Birren J, Lubben J, Rowe J, Deutchman D, editors. The concept of measurement of quality of life in frail elders. San Diego: Academic Press; 1991. pp. 3–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP. Quality of life in Alzheimer disease. Alzheimers Dis Assoc Disord. 1994;8:138–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton MP (2003) The Philadelphia geriatric centre morale scale. Available via: http://www.abramsoncenter.org/PRI/scales.htm)

- Löwenstein A, Ogg J (Eds) (2003) OASIS. Old Age and Autonomy: The role of service systems and intergenerational family solidarity. Final report. Haifa: University of Haifa. Available via: http://www.dza.de/forschung/oasis_report.pdf

- Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age. International and multi-disciplinary perspectives. New York: Springer; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Netten A. The social production of welfare. In: Knapp M, Challis D, Fernandez JL, Netten A, editors. Long-term care: matching resources and needs. Aldershot: Ashgate; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Lindenberg S, Steverink N, Vonkorff M. Quality of life and social production functions: a framework for understanding health effects. Soc Sci Med. 1997;45:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/S0277-9536(97)00032-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osoba D, Rodrigues G, Myles J, Zee B, Pater J. Interpreting the significance of changes in health-related quality-of-life scores. J Clin Oncol. 1998;16(1):139–144. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1998.16.1.139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oswald F, Wahl HW. Dimensions of the meaning of home. In: Rowles GD, Chaudry H, editors. Home and identity in late life: international perspectives. New York: Springer; 2005. pp. 21–45. [Google Scholar]

- Øvretveit J (1998) Evaluating health interventions. An introduction to evaluation of health treatments, services, policies and organizational interventions. Open University Press, Buckingham

- Pieper R, Vaarama M. The concept of care-related quality of life. In: Vaarama M, Pieper R, Sixsmith A, editors. Care-related quality of life in old age. Concepts, models, and empirical findings. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 65–101. [Google Scholar]

- Power M, Quinn K, Schmidt S, WHOQOL-OLD Group Development of the WHOQOL-Old module. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:2197–2214. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-7380-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rapley M. Quality of life research. A critical introduction. London: Sage; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Skevington SM, Lofty M, O’Connell K, The WHOQOL Group The World Health Organisation’s WHOQOL-Bref quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and the results of the international field trial. A Report from the WHOQOL Group. Qual Life Res. 2004;13:299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiit E, Saks K, Vaarama M. Care Keys data and statistical methods. In: Vaarama M, Pieper R, Sixsmith A, editors. Care-related quality of life in old age. Concepts, models, and empirical findings. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 45–61. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarama M, Kaitsaari T. Ikääntyneiden toimintakyky ja koettu hyvinvointi. (Subjective well-being in older Finns) In: Heikkilä M, Kautto M, editors. Suomalaisten hyvinvointi (Welfare in Finland in 2002) Jyväskylä: Gummerus Printing; 2002. pp. 120–148. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarama M, Ollila K (2008) Koettu hyvinvointi ja elämänlaatu kolmannessa iässä (Subjective wellbeing and quality of life in the third age). In: Moisio S, Karvonen S, Simpura J, Heikkilä M (eds) Suomalaisten hyvinvointi (Welfare in Finland in 2008). Vammalan kirjapaino Oy, Vammala, pp 116–139

- Vaarama M, Tiit E. Quality of life of older home care clients. In: Vaarama M, Pieper R, Sixsmith A, editors. Care-related quality of life in old age. Concepts, models, and empirical findings. New York: Springer; 2008. pp. 168–195. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarama M, Ylönen L (2006) Kotihoidon laatu ja tuloksellisuus Espoossa. Asiakkaiden näkökulma. (Quality of life and quality of home care in Espoo—the perspective of the clients). Espoon kaupunki ja Stakes. Espoon kaupunki. Sosiaali- ja terveystoimen julkaisuja 3/2006. Available via: http://www.espoo.fi/default.asp?path=1;28;11884;8532

- Vaarama M, Hakkarainen A, Laaksonen S (1999). Vanhusbarometri 1998. (Old age barometer 1998). Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön selvityksiä 1999:3. Helsinki. OY Edita AB

- Vaarama M, Luoma ML, Ylönen L. Ikääntyneiden toimintakyky, palvelut ja koettu elämänlaatu. (Functional ability, services and quality of life in older Finns) In: Kautto M, editor. Suomalaisten hyvinvointi (Welfare in Finland 2005) Stakes. Saarijärvi: Gummerrus printing; 2006. pp. 104–136. [Google Scholar]

- Vaarama M, Pieper R, Sixsmith A, editors. Care-related quality of life in old age. Concepts, models, and empirical findings. New York: Springer; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Veenhoven R. The four qualities of life. Ordering concept and measures of the good life. J Happiness Stud. 2000;1:1–39. doi: 10.1023/A:1010072010360. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Walker A, Mollenkopf H. International and multidisciplinary perspectives on quality of life in old age. conceptual issues. In: Mollenkopf H, Walker A, editors. Quality of life in old age. International and multi-disciplinary perspectives. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- WHOQOL Group Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BFER quality of life assessment. Psychol Med. 1998;28:551–558. doi: 10.1017/S0033291798006667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]