Abstract

Population ageing has paved the way for important and lasting multigenerational bonds, particularly between grandparents and grandchildren. Proximity is a powerful enhancer of relations, and co-residence, by involving continual proximity and long-term commitment, is particularly facilitative of significant linkages between generations. Although co-residence has generally been decreasing in Western societies, in the last decades of the millennium, a trend reversal was identified in the proportion of multigenerational households in the USA. Using data drawn from the European Community Household Panel, 1994–2001, some descriptive insights are provided that were considered to be missing in regard to the socio-demographic composition of extended households with grandparents in Portugal. Additionally, this study finds a rising trend in the proportion of multigenerational households, specifically those that include both grandparents and grandchildren. Portugal is possibly the European country that has the highest probability of exhibiting this pattern of evolution, because of the combination of its being a welfare state with limited resources, its historical reliance on family solidarity and its high level of participation of women in the labor market. Co-residence is a type of intergenerational transfer that can benefit any of the generations involved, but the direction of its net flow is still open to debate. A breakdown is made of its trend into age, period and cohort effects, in order to contribute to the discussion of the relative importance of the different generations in the shared living arrangement. Our findings suggest a mixture of interests, as well as a predominant influence of contemporary circumstances in the observed trend. These contemporary circumstances may be persistent or transient, but co-residence with grandparents is certainly an enduring mechanism, which households use in order to meet their needs.

Keywords: Grandparents, Multigenerational households, Ageing, Co-residence, Portugal

Life expectancy has been rising, thereby increasing the probability of people experiencing grandparenthood for longer periods. This changing age structure has paved the way not only for more important multigenerational bonds, namely between grandparents and grandchildren, but also for longer “shared lives” (Bengtson 2001; Wilton and Davey 2006; Szinovacz 1998; Barranti 1985). The recognition of this effect has prompted a greater interest in the study of grandparenthood, coupled with the recognition that the present demographic structure necessitates three-generational views (Hagestad 2006).

Although a growing body of research has explored the roles of grandparents in the family, as well as the determinants and the geographic prevalences of grandparenting, some topics have received little attention. A recent broad study of grandparenting in Europe (Glaser et al. 2010) has identified the analysis of trends in co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren, particularly in Europe, as one of the main gaps in the current state of research.

Space transfers, or co-residence, are one of the three dominant forms that transfers between the oldest generation and the younger ones may take, the others are time and money. Co-residence has been gradually decreasing in the western societies since the nineteenth century. That situation is related with the increased importance of the individual in relative terms, which gives more weight to the negative side of co-residence: a loss of independence, a loss of authority, and difficulty in reconciling lifestyles. The consequent change in the co-residence patterns of different generations may stem from the historical rise in the per capita income of the developed economies, particularly that of the oldest generation. However, the economic and social benefits of co-residence are still relevant. There are increasing returns to scale in sharing a house (domestic services and consumption expenses, such as electricity, telephone, or cable TV), and it offers different interaction possibilities from living separately.

For the USA, a trend reversal has been seen to have occurred in the 1980s in the proportion of multigenerational households (Taylor et al. 2010). There has also been an increase in co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren in the USA, and particularly in the number of custodial grandparents (Caputo 2001; Bryson and Casper 1999; Fuller-Thomson and Minkler 2001; Mutchler and Baker 2009).

For Europe, studies of multigenerational households and co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren are not as abundant as they are for the USA. Such studies have usually identified a trend toward a decrease in multigenerational households (Palloni 2002; Tomassini et al. 2004), despite the general recognition of important regional differences, with a much higher prevalence of this type of household in Southern European countries.

Portugal, a Southern European country, exhibits the same decreasing pattern, with a share of 15% of complex households in 1960, and a share of only slightly more than 10% in 2001 (Vasconcelos 2003; Wall 2004). However, Albuquerque (2009) identified an increase in the proportion of extended households in Portugal in the period from 1994 to 2001. There are some differences between these three studies, which should be taken into account. The first two studies use census data, while the third one, namely, Albuquerque (2009) uses survey data, European Community Household Panel (ECHP). Furthermore, in the case of the first two studies, households with parents and adult children with no partner or children of their own are classified as nuclear, irrespective of the children’s ages—complex households are contrasted with these nuclear households—while in the case of Albuquerque’s study, extended households are those that are not nuclear, and nuclear households are considered to be those consisting of a couple living with their children (all children under 26 years of age) or of any subset comprising a possible combination of these people (a father with children, a mother with children, a couple with no children, or even just an individual person). Albuquerque (2009) does not specifically identify households where grandparents and grandchildren co-reside, but we hypothesize that there may be a similar rising trend in such co-residence for the same period. If this is confirmed, then Portugal is the first European country in which a short-term rising trend has been identified.

In this study, we explore co-residence involving both grandparents and grandchildren in Portugal. We chose to focus our interest on this country because little research has been undertaken on these topics for Portugal, and so it makes a timely casestudy. Seen in the light of the categorization of welfare regimes pioneered by Esping-Andersen (1990) and extended by many other authors, Portugal has unique characteristics, which situate it somewhere between a Mediterranean and a liberal welfare regime. The liberal regime is one of the three regimes originally proposed by Esping-Andersen and is characterized by low levels of protection and social services, with means-tested benefits. The Mediterranean or Southern European welfare regime is a fourth regime that has been identified by some authors, including Trifiletti (1999), and is characterized by a lack of resources, which means that protection is provided against a smaller number of social risks, defined as those risks that the family cannot protect itself against sufficiently. Portugal has a shortage of resources to finance social polices (Mediterranean) and a high activity ratio for women with no protection of their family roles (liberal) (Trifiletti 1999). These characteristics suggest that a potentially very important role is played by informal care and extended household structures, which complement or constitute a substitute for the provision of services in weak social states. Hence, it is particularly pertinent to focus on Portugal when analyzing households with grandparents and grandchildren.

Co-residence may be prompted mainly by the interests of the older generations, as a means, for example, of dealing with spousal loss, declining health, or economic difficulties, but it may also be motivated by the interests of the younger generations, who may be faced with credit constraints or find themselves in need of practical help. Unemployment, a late job-entry age, divorce, and a need for childcare among the younger generation are all possible triggers of co-residence. This is clearly applicable to the living arrangements involving grandparents and grandchildren.

Since it is equally plausible that the main beneficiaries of co-residence are the oldest or the youngest generations, this is a research question that has to be assessed empirically. Although some research has already taken place, it remains an open question, partly because we can usually only rely on indirect evidence (Aquilino 1990; Grundy and Harrop 1992; Ward et al. 1992; Lee and Dwyer 1996; Szinovacz 1996).

Even though the quality and meaning of relationships cannot be directly inferred from frequency of contact, some of the many roles that grandparents may play in their grandchildren’s lives, and which are amply recognized in the literature (Bengtson 1985, 2001; Jendrek 1994; Szinovacz 1998; Reynolds et al. 2003; Musil et al. 2006; Denham and Smith 1989), are more difficult, or even impossible, to perform at a distance. This is the case with the provision of physical help as a caregiver.

Shared living arrangements involve continual proximity and long-term commitment, which favors the provision of care (Chappell 1991). Co-resident grandparents are considerably more likely to be caregivers than grandparents without children in the home (Fuller-Thomson et al. 1997), and the presence of co-resident children and grandchildren is a strong predictor of extensive, as opposed to intermediate, care provision (Fuller-Thomson and Minkler 2001).

As stated above, space transfers may also have economic motivations. If they constitute the driving reasons for co-residence, it is probable that families with co-resident grandparents are those that rank lower in terms of their economic status. Moreover, different types of extended families with grandparents may be differently represented across their income distribution. This information is valuable for policy reasons. More than the information about the individual, it is the whole-family perspective that matters for the assessment of economic well-being. Furthermore, in an era of tough budgetary constraints that severely limit welfare support, social policies may be aimed at creating better conditions for families to meet their own needs. Consequently, an overall assessment is essential to identify those types of households that are in greatest need.

In the light of all these considerations, the aims of this paper are (i) to provide some descriptive insights that are missing with regard to the socio-demographic composition of extended households with grandparents in Portugal, distinguishing between several types, while also evaluating the hypothesis that, between 1994 and 2001, the proportion of extended households including grandparents and grandchildren increased; and (ii) to contribute to the debate about the relative importance of the generations in explaining observed trends in co-residence, by helping to clarify which of them benefits more from this situation.

One possible strategy for examining this last issue is to search for an age effect in the trend in co-residence. If co-residence originates mainly in the interests of the younger generations, such as providing a care for children or offering help in household expenses for unemployed or precariously employed adult children, grandparents in their 60s should exhibit higher rates of co-residence than grandparents in their 80s, for instance. On the contrary, if co-residence mainly arises from the needs of frail older people who cannot live independently anymore, then we would expect co-residence rates to mainly increase with age, particularly after a certain age. A mixture of these two may result in approximately null age effects. This was recognized by Christenson and Hermalin (1991), but lacking longitudinal data, they could not separate age effects from cohort and period effects.

It should be noted that when longitudinal data are used, the same individuals are aged differently in different periods, and, in the same period, different ages correspond to different cohorts. Therefore, in order to extract the age effect, it is necessary to separate it from the other two using an Age-Period-Cohort (APC) model.

Methods

Data

We use longitudinal data from the ECHP for Portugal, survey waves 1–8, covering the period from 1994 to 2001. The survey is aimed at individuals living in private households. There are two units of analysis: the individual and the household. The ECHP has four different types of cross-sectional files for each wave (Eurostat 2003b): household file, personal file, relationship file, and register file. It is necessary to combine information from these files to calculate the measures that we use in this article. The response rates for Portugal are high: generally over 90%. As far as attrition is concerned, the main pattern is monotone attrition—individuals dropping out of the panel without returning to it—amounting to 20% of the individuals that were present in the first wave (See Vandecasteele and Debels 2004).

The ECHP provides weights that are designed to make it nationally representative by correcting any sampling distortion and ensuring that the data reflect the population structure by sex, age, household size, and other criteria. The cross-sectional weights that we use correspond to the variable RG002 when the unit of analysis is the individual, and to HG004 when the unit of analysis is the household. These weights are adjusted from wave to wave by a factor that takes into account both attrition and changes in the distribution of the population. For a detailed description of the weighting procedure used in the ECHP, see Eurostat (2003a) or Peracchi (2002).

In order to obtain an idea of how well data from the ECHP represent the population, we compared the percentage of households containing three or more generations, based on the 2001 Census data, with the percentage of households with grandparents, excluding skipped-generation households, obtained from the ECHP. The ECHP percentages are a little lower: 9.5% as opposed to 11% from the Census. Therefore, we should take this into account when analyzing the numbers.

Measures

Our focus of interest in this article is co-resident grandparents (CGPs): individuals who live in the same household as at least one grandchild. The relationship files allow for the identification of co-resident grandparents in each household, for each wave. In order to obtain information about the grandparent (such as gender or age) or about other individuals in the household, it is necessary to match a relationship file with the corresponding personal file, household file, or register file.

Working status

We consider an adult to be working if he or she answered “normally working (15+ h/week)” to the main activity status—self-defined question (PE002).

Caring status

We consider a grandparent to be caring for a child if he or she claimed to be “looking after children” or “looking after a child and a person (…) other than a child” to the question “Do your present daily activities include looking after children or other persons who need special help because of old age, illness or disability, without receiving any pay for this?” (PR006).

Equivalized household income

A household’s financial status is the result of the combination of the total income of the household and the ratio of dependents to earners. Hence, this is well interpreted by their equivalized household income. Equivalized household income is calculated by dividing HI100 by HD005. HI100 is the total net household income (for the whole year before the survey), whereas HD005 is the equivalized household size, using the modified OECD scale. Using equivalized household income, we calculated the different thresholds for income quartiles for each year. Then, we examined the distribution of the different types of households among these quartiles. The first quartile is the one with the lowest income.

Skipped-generation households

Skipped-generation households are households where grandparents live with their grandchildren, without the presence of the middle generation, i.e., the children’s parents.

Households with teenage parent and grandparent

These are households containing at least three generations, where one of the members is under 18 years old and is the parent of a child.

Statistical analyses

Following a descriptive statistical analysis, where the household was the unit of observation, we tested for the fit of an APC model, where the unit of observation was the individual. In this study, the analysis was not applied to the percentage of households that have a co-resident grandparent, but to the percentage of individuals of a certain age that are co-resident grandparents, each year. A general APC model corresponds to 1.

|

1 |

where Ψijk represents the dependent variable; μ is the overall mean; αi represents the effects of age; DAge are the age dummies; βj represents the effects of the time period; DPeriod are the period dummies; γk represents the cohort effects; DCohort are the cohort dummies; and eijk is a normally distributed error term.

Each age dummy has the value 1 when the observation corresponds to an individual that is a certain age; the same individual observed in a different wave will be a different age. Each period dummy has the value 1 when the observation refers to a certain time period; all the observations in the same wave have the same period dummy values. Each cohort dummy has the value 1 when the observation corresponds to an individual born in a certain year; the same individual observed in a different wave will have the same cohort dummy value.

Age effects are associated with changes in the life course.

Period effects measure the effect of contemporary circumstances, such as short-run economic-cycle fluctuations or social policy developments.

Cohort effects measure trends associated with social change. Individuals that belong to the same birth cohort experience “similar societal circumstances during their formative years” (Coenders and Scheepers 1998, p. 408), which may be reflected in a typical behavior pattern. As new cohorts reach grandparenthood, they may display different preferences for co-residence with younger generations. Furthermore, different cohorts of younger generations may have distinct attitudes toward older parents/grandparents who cannot live independently.

It is well known that there is an identification problem with the linear additive APC model: the perfect linear relationship that exists between the three effects (age = period−cohort) implies that they cannot be estimated separately. Since the pioneering study of Mason et al. (1973), several solutions have been proposed for this problem. The conventional solution has been to set constraints for the parameters being estimated. In particular, if the effects of being in either of two age groups, either of two periods or either of two cohorts are assumed to be equal, then the model becomes identified, and the parameters may be estimated. However, setting constraints is a dangerous practice, since constraints that do not appear to differ greatly may produce very different age, period, and cohort effects (Mason and Wolfinger 2001).

Hence, more recent approaches that show signs of being more reliable have been developed. One of these is the intrinsic estimator approach (Fu 2000; Yang et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2007; Yang et al. 2008; Fu 2008), which is a method based on estimable functions that are invariant to the selection of constraints for the parameters, and yields a unique solution for the APC model. Yang et al. (2004) show that the intrinsic estimator method produces a smaller variance than the classical methods of setting an arbitrary constraint. There are as yet few examples of articles using this form of the APC model, and we have chosen to use it in this article. It has recently and conveniently been included in software packages such as Stata and S-Plus.

If the true effects of one or two of the three elements—age, period, or cohort—are null, then the full model will overfit the data and produce inexact results. Therefore, as a previous step in the estimation process, Yang et al. (2007) recommend estimating the reduced models (A, P, C, AP, PC, and AC) and comparing them with the complete model, to verify whether the simpler models are not in fact better than the full APC. When the analysis suggests that the three time dimensions are present, we apply the intrinsic estimator.

The estimation of the reduced models will use a generalized linear model (GLM) with a binomial family distribution and a logit link function. The GLM provides a unified framework, which can be applied to various models. The family distribution and the link function, as we specify them, make it equivalent to fitting a logistic regression. The model selection will make use of the two most commonly used information criteria of model selection, the Akaike (AIC) and the Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC). These take into account the parsimony of the models when testing their fit. The punishment for model complexity is larger with BIC. The best models are those with lower values of AIC and BIC. We use Stata in our estimations.

Results

Co-resident grandparents’ profile and evolution

The age range of CGPs in our sample is 32–84, with the average age of each CGP being between 65.2 and 66.3 years old. Grandmothers represent 64% of all CGPs. Table 1 summarizes the characterization of households with grandparents. As hypothesized, these already high rates of co-residence with grandparents increased during the period under analysis, as can be seen by observing either the proportion of households with grandparents or the proportion of individuals of a certain age, who co-reside with grandchildren.

Table 1.

Households with grandparents

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Households with grandparent(s) | 6.58 | 7.61 | 8.33 | 9.43 | 9.94 | 10.42 | 10.53 | 11.01 |

| % Households with grandfather | 3.05 | 3.91 | 4.21 | 4.48 | 4.64 | 5.25 | 5.14 | 5.42 |

| % Households with grandmother | 5.82 | 6.73 | 7.34 | 8.35 | 8.99 | 9.33 | 9.43 | 9.97 |

| % Households with both | 2.36 | 3.13 | 3.32 | 3.48 | 3.71 | 4.21 | 4.23 | 4.55 |

| % Skipped-generation households | 0 | 0.55 | 0.64 | 0.69 | 0.87 | 1.11 | 0.80 | 0.80 |

| % Households with child up to 5 years of age and grandparent | 2.24 | 2.99 | 2.83 | 3.30 | 3.87 | 4.20 | 4.12 | 4.03 |

| % Households with child up to 18 years of age and grandparent | 5.54 | 5.97 | 6.94 | 7.57 | 7.98 | 8.47 | 8.31 | 8.63 |

| % Households with teenage parent and grandparent | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.10 | 0.07 | 0.04 | 0.13 | 0.14 | 0.15 |

| % Households with teenage mother and grandparent | 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.01 | 0.06 | 0.00 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.11 |

| Total number of households | 4,881 | 4,916 | 4,849 | 4,802 | 4,716 | 4,683 | 4,633 | 4,614 |

Source Author’s calculations based on European Community Household Panel data.

Note: Cases weighted by the cross-sectional weight of the households, HG002

There are many studies indicating a larger proportion of older women than men living with adult children. However, these studies do not usually explicitly identify co-residence with grandchildren. Our data revealed that there were more households with grandmothers than households with grandfathers, reflecting the greater longevity of women, the higher probability of their not remarrying after widowhood, as well as their traditional caring role. Less than half of the households with grandmothers were households with both grandmothers and grandfathers. Conversely, about 80% of households with grandfathers were households with both grandmothers and grandfathers. Most of the households with more than two individuals identified as CGPs were vertically extended households where four generations live together, but which did not include the parents of both sides of a couple.

The percentage of skipped-generation households was much smaller than the percentage of three-generation households. It should be noted that these households may have included adult grandchildren. Most households with grandparents contained children aged under 18. Of these, nearly half include children up to the age of five. A very small percentage of households had a teenager with a child (with or without a partner) living with the teenager’s parents.

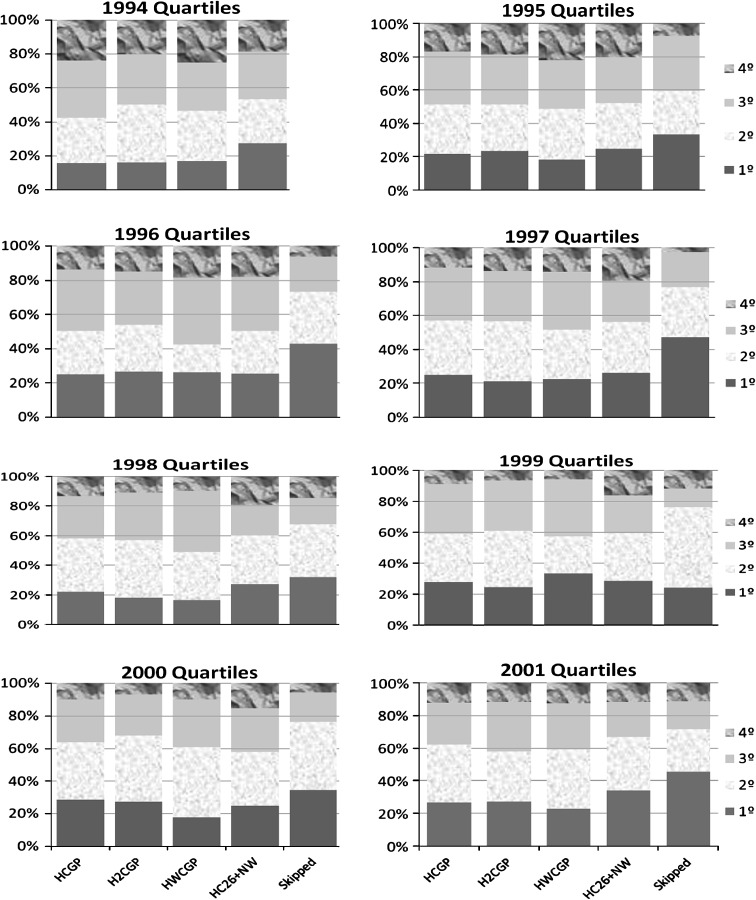

Comparison of the different types of households according to their income revealed that households with grandparents were usually under-represented in the highest income quartile. As the years have passed, the percentage of households with CGPs in the higher income quartiles has decreased. Households with CGPs were initially not very different from the rest of the households, but became relatively poorer. Another salient result was that skipped-generation households tended to be considerably concentrated in the lower income quartiles. On the other hand, among the households with CGPs, it was usually those that had at least one working CGP and those that had a non-working adult aged 26 or higher, which were more frequently represented in the higher income quartiles for most of the years. These results are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Equivalized income quartiles of different types of households with Co-resident Grandparents (CGPs). HCGP households with CGPs, H2CGP households with at least two CGPs, HWCGP households with working CGP, HC26+NW households with children aged 26+ not working, Skipped skipped-generation households. Note: The first quartiles are those with the lowest income levels

The relative importance of the generations in explaining observed trends in co-residence

We then investigated the relative importance of the generations in explaining observed trends in co-residence. In a first approach, we looked for information in the socio-demographic characteristics of households with grandparents that might suggest whether co-residence was mainly in the younger generation’s or the older generation’s interest. See Table 2.

Table 2.

Indicators of whether co-residence is mainly in the younger generation’s or the older generation’s interest

| 1994 | 1995 | 1996 | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Households with grandparents* | 6.58 | 7.61 | 8.33 | 9.43 | 9.94 | 10.42 | 10.53 | 11.01 | |

| With working grandparent* | % Households | 1.74 | 2.46 | 2.45 | 2.87 | 2.84 | 3.63 | 3.11 | 3.29 |

| % Households with CGP | 26.44 | 32.33 | 29.41 | 30.43 | 28.57 | 34.84 | 29.53 | 29.88 | |

| With grandparent and non-working adult aged 26 or older* | % Households | 2.51 | 2.37 | 2.78 | 3.37 | 3.68 | 3.36 | 3.22 | 3.36 |

| % Households with CGP | 38.15 | 31.14 | 33.37 | 35.74 | 37.02 | 32.25 | 30.58 | 30.52 | |

| % CGPs caring for children up to 5 years of age* | 18.23 | 12.42 | 16.16 | 18.55 | 23.05 | 23.51 | 19.46 | 18.89 | |

| % CGPs caring for children up to 18 years of age* | 28.33 | 24.49 | 27.37 | 30.39 | 31.36 | 34.43 | 30.96 | 32.25 | |

| % Three-generation households where the oldest generation is the householder** | 52.1 | ||||||||

*Source Author’s calculations based on ECHP data

** Source 2001 Census, INE

Note: CGP is the acronym for co-resident grandparent

Of the households with grandparents, between 26 and 35% contained at least one working grandparent. A working grandparent is probably not dependent. Using the same basis of comparison, between 31 and 38% contained at least one child, a child-in-law or possibly a grandchild aged 26 or older that was not working at least 15 h per week. These were potentially the interested parties in co-residence. In more than half of the households composed of three generations, the oldest generation was the householder (downward-extended households). These rough indicators suggested that many of the shared living arrangements were mainly in the younger generation’s interest.

Between a quarter and a little over a third of CGPs stated that they took care of children up to 18 years of age and more than half of these took care of children up to 5 years of age. This is certainly an important resource for families, but it is not possible to identify those situations where caring is a motive for co-residence and those where it is simply a by-product.

As justified above, we then sought to evaluate the importance of age in the trends in living arrangements including grandparents and grandchildren, separating this effect from cohort and period effects. The estimation of the reduced models (A, P, C, AP, PC, and AC) and their comparison with the complete model can be observed in Table 3. Clearly, the complete APC model was never the one best suited to the data. Using either the BIC criterion, or the AIC criterion, the model with only period effect was also found to be the best one for evaluating the proportion of individuals of the same age who were CGPs.

Table 3.

Measures of model fit

| Model I: proportion of individuals that are CGPs | Model II: proportion of CGPs caring for children up to 5 years of age | Model III: proportion of CGPs caring for children up to 18 years of age | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BIC | AIC | BIC | AIC | BIC | AIC | |

| A | −1619.646 | 0.59743 | −906.059 | 0.73615 | −900.299 | 0.88527 |

| P | −2481.515 | 0.49027 | −1591.440 | −0.78036 | −1572.425 | 0.96682 |

| C | −2191.071 | 0.66906 | −1436.439 | 0.83783 | −1432.934 | 0.97327 |

| AC | −1319.519 | 0.91120 | −743.992 | 0.80192 | −741.729 | 1.10092 |

| PC | −2150.916 | 0.69691 | −1398.230 | 0.87793 | −1393.696 | 1.01676 |

| AP | −1579.783 | 0.63957 | −869.817 | 0.9692717 | −863.424 | 0.95421 |

| APC | −1849.278 | 0.93075 | −1195.120 | 1.08831 | 1196.018 | 1.20968 |

Note: CGPs is the acronym for co-resident grandparents

Because one possibly relevant motive for co-residence is childcare by grandparents, and we would expect that older individuals might be less functionally able to provide care, we sought to identify APC effects in the proportion of CGPs who take care of children, expecting a clearer age effect. We considered separately, the care given to children up to 5 years of age and care given to children up to 18 years of age. Again, age and cohort effects did not prove significant, making use of the BIC criterion. While using the AIC criterion, the model with only period effect is again the best for evaluating the proportion of CGPs of the same age, taking care of children up to the age of 5 years. However, this time, the model with only age effect used for evaluating the proportion of CGPs of the same age, taking care of children up to the age of 18 has the lowest value. Nevertheless, the model with only period effect does not look much worse. We conclude that it is not adequate to estimate the APC model with the intrinsic estimator, and that cohort and age effects are not significant in terms of the tendency for individuals to co-reside with grandchildren, because the models with only period effect are the ones with the best fit.

Discussion and conclusions

Portugal exhibits high rates of co-residence with grandparents, which is visible by comparing the rates of co-residence in Portugal (between 6.5 and 11%—see Table 1), with, for e.g., the proportion of households with grandparents in the 2000 census for the USA—3.9% (Simmons and Dye 2003). In our study, we not only found a high level of co-residence involving grandparents and grandchildren, but we also noted that between 1994 and 2001, there was an increase over time, which indicates that this type of living arrangement should not be discarded as having been clearly superseded through modernization. Such a trend has so far been recognized only in the USA. In Europe, Portugal is probably the country where we might expect to find this deviation from the “recent” historical framework, because of the combination of its being a welfare state with limited resources, its traditional reliance on family solidarity, and its high level of participation of women in the labor market.

Some situations that have attracted attention elsewhere and are considered to be at least partly responsible for the increase in co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren (skipped-generation households and teenage pregnancies) occur in only a small proportion of households with co-resident grandparents (CGPs) in Portugal. In order to form an idea of the relative dimension of skipped-generation households, the scores of 0.55 and 1.1% that we obtained may be compared with the estimates of 0.9 and 1.9% for the proportion of skipped-generation households in two different states of the USA, made by Mutchler and Baker (2004). Nevertheless, although skipped-generation households represent only a small proportion of households with CGPs, the number of CGPs increased in the reference period, and the fact that they are over-represented in the lower income quartiles deserves attention. In general, households with CGPs are usually under-represented in the higher income quartiles. This is not surprising, since co-residence is frequently a strategy adopted by low-income households in order to pool their resources.

What caught our attention in particular was that, during the period under consideration, the percentage of households with CGPs in the higher income quartiles decreased, which indicates not only that households with CGPs have, on average, greater financial difficulties than the others, but also that their situation has worsened. Even the households with at least one working grandparent—representing the types of households with CGPs that are generally better positioned in terms of income distribution—have fallen in the income ranking.

One phenomenon that can be seen to have accompanied the overall aging of the population is the reduction in the number of children available to take care of each older parent. Although this subject has not been greatly investigated, it might lead to a rise in the number of households that include parents of both spouses. Interestingly, we found very few examples of this kind of situation in our sample.

The formation of multigenerational households may be determined largely by the needs of the older generation or by the needs of the younger ones. We have no way of establishing directly who are the main beneficiaries of co-residence in households with CGPs. As a contribution to the debate, we began by examining some indicators, such as the prevalence of CGPs providing childcare, the distribution of householder status between generations, the prevalence of households with CGPs in which there is a working grandparent, and/or an adult of the youngest generation aged 26 or older, who is not working at least 15 h per week. These indicators suggest that the number of shared living arrangements that function mainly in the younger generation’s interest is by no means negligible.

Next, we used a different approach: assuming that the older the grandparents were, the higher was the probability of their needing support and the lower the probability of their providing support, we investigated the effect of age on the proportions of CGPs. In fact, the longitudinal design of our sample makes it possible to distinguish the age effect from other confusing effects. As no age effect was identified, the results obtained point to a mixture of interests. Moreover, the predominant influence of contemporary circumstances on the observed trend suggests that the possible explanations for the ever greater percentage of individuals who are CGPs tend to cut across all cohorts and all ages of CGPs. They may be related to the business cycle, or to social and cultural changes that have affected all cohorts of individuals over 65 similarly, but further research is required to identify the specific underlying causes.

Our results have policy implications: even though the relevance of encouraging or discouraging co-residence between grandchildren and grandparents is not under discussion in this article, if the period effect is the predominant one, then it is probably easier for policies to influence (either deliberately or not) the proportion of CGPs than it would have been, if a strong cohort effect or a strong age effect were detected. There is no need for differential measures to be adopted for separate cohorts or ages, and people are generally expected to act according to contemporary circumstances. Also, policymakers should be aware of the particularly difficult financial circumstances faced by skipped-generation households.

Although this study adds further knowledge to the research currently being undertaken into trends in co-residence between grandparents and grandchildren, particularly in Europe, our results should be interpreted with some caution, as there are certain limitations associated with the data. On the one hand, our conclusions about the relative interest of generations in the co-residence phenomenon are based on indirect evidence; on the other hand, they are based on the examination of a relatively short period of time.

Co-residence with grandparents is the result of a mixture of interests on the part of the generations involved. Although this type of co-residence is frequently found to be decreasing, our study suggests that it is making a comeback in Portugal. This is seen to be the result of contemporary circumstances, which may be either persistent or merely transient, but our findings certainly reveal that it is an enduring mechanism, which households use to meet their needs.

References

- Albuquerque PC. The elderly and the extended household in Portugal: an age-period-cohort analysis. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2009;28:271–289. doi: 10.1007/s11113-008-9099-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aquilino W. The likelihood of parent-adult child coresidence: effects of family structure and parental characteristics. J Marriage Fam. 1990;52:405–419. doi: 10.2307/353035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barranti C. The grandparent/grandchild relationship: family resource in an era of voluntary bonds. Fam Relations. 1985;34:343–352. doi: 10.2307/583572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL. Diversity and symbolism in grandparental roles. In: Bengtson VL, Robertson JF, editors. Grandparenthood. Sage, CA: Beverly Hills; 1985. pp. 11–25. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the nuclear family: the increasing importance of multigenerational bonds. J Marriage Fam. 2001;63:1–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00001.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryson K, Casper L. Coresident grandparents and grandchildren. Washington, DC: US Department of Commerce; 1999. pp. P23–P198. [Google Scholar]

- Caputo RK. Grandparents and coresident grandchildren in a youth cohort. J Fam Issues. 2001;22:541–556. doi: 10.1177/019251301022005001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chappell NL. Living arrangements and sources of caregiving. J Gerontol Soc Sci. 1991;46:S1–S8. doi: 10.1093/geronj/46.1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson B, Hermalin A. A demographic decomposition of elderly living arrangements with a Mexican example. J Cross Cult Gerontol. 1991;6:331–348. doi: 10.1007/BF00116824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coenders M, Scheepers P. Support for ethnic discrimination in the Netherlands 1979–1993: effects of period, cohort, and individual characteristics. Eur Sociol Rev. 1998;14:405–422. [Google Scholar]

- Denham T, Smith C. The influence of grandparents on grandchildren: a review of the literature and resources. Fam Relations. 1989;38:345–350. doi: 10.2307/585064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Esping-Andersen G. The three worlds of welfare capitalism. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat (2003a) Construction of weights in the ECHP, DOC. PAN 165/2003-06. http://www.cmh.ens.fr/acsdm2/equalsoc/ECHP/PAN165-200306.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2011

- Eurostat (2003b) ECHP UDB manual, DOC. PAN 168/2003-12. http://circa.europa.eu/Public/irc/dsis/echpanel/library?l=/user_db/manualpan168200312pdf/_EN_1.0_&a=d. Accessed 20 January 2011

- Fu WJ. Ridge estimator in singular design with application to age-period-cohort analysis of disease rates. Commun Stat Theory Methods. 2000;29:263–278. doi: 10.1080/03610920008832483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu WJ. A smoothing cohort model in age period cohort analysis with applications to homicide arrest rates and lung cancer mortality rates. Sociol Methods Res. 2008;36:327–361. doi: 10.1177/0049124107310637. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M. American grandparents providing extensive child care to their grandchildren: prevalence and profile. Gerontol. 2001;41:201–209. doi: 10.1093/geront/41.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M, Driver D. A profile of grandparents raising grandchildren in the United States. Gerontol. 1997;37:406–411. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaser K, Montserrat E, Waginger U, Price D, Stuchbury R, Tinker A (2010) Grandparenting in Europe. Grandparents plus report/June 2010

- Grundy E, Harrop A. Co-residence between adult children and their elderly parents in England and Wales. J Soc Policy. 1992;21:325–348. doi: 10.1017/S0047279400019978. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagestad GO. Transfers between grandparents and grandchildren: the importance of taking a three-generation perspective. Zeitschrift für Familienforschung. 2006;18:315–332. [Google Scholar]

- Jendrek M. Grandparents who parent their grandchildren: circumstances and decisions. Gerontol. 1994;34:206–216. doi: 10.1093/geront/34.2.206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee GR, Dwyer JW. Aging parent-adult child coresidence: further evidence on the role of parental characteristics. J Fam Issues. 1996;17:46–59. doi: 10.1177/019251396017001004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mason WM, Wolfinger NH (2001) Cohort analysis. California Center for Population Research WP CCPR-005-01

- Mason KO, Mason WH, Winsborough HH, Poole WK. Some methodological issues in cohort analysis of archival data. Am Sociol Rev. 1973;38:242–258. doi: 10.2307/2094398. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musil CM, Warner CB, Zausznieswski JA, Jeanblanc AB, Kercher K. Grandmothers, caregiving, and family functioning. J Gerontol. 2006;61B(2):S89–S98. doi: 10.1093/geronb/61.2.s89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, Baker LA. A demographic examination of grandparent caregivers in the census 2000 supplementary survey. Popul Res Policy Rev. 2004;23:359–377. doi: 10.1023/B:POPU.0000040018.85009.c1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, Baker LA. The implications of grandparent coresidence for economic hardship among children in mother-only families. J Fam Issues. 2009;30:1576–1597. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09340527. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palloni A. Living arrangements of older persons. Popul Bull UN Special Issue. 2002;42(43):54–110. [Google Scholar]

- Peracchi F. The European community household panel: a review. Empir Econ. 2002;27:63–90. doi: 10.1007/s181-002-8359-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds G, Wright J, Beale B. The roles of grandparents in educating today’s children. J Instr Psychol. 2003;30:316–325. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T, Dye JL (2003) Grandparents living with grandchildren: 2000, census 2000 brief C2KBR-31. U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, DC. www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/c2kbr-31.pdf

- Szinovacz ME. Living with grandparents: variations by cohort, race, and family structure. Int J Sociol Policy. 1996;16:89–123. doi: 10.1108/eb013287. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Szinovacz ME. Grandparents today: a demographic profile. Gerontol. 1998;38:37–52. doi: 10.1093/geront/38.1.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Passel J, Fry R, Morin R, Wang W, Velasco G, Dockterman D (2010) The return of the multi-generational family household. A Social & Demographic Trends Report. Pew Research Center, Washington, DC

- Tomassini C, Kalogirou S, Grundy E, Fokkema T, Martikainen P, Broese van Groenou M, Karisto A. Contacts between elderly parents and their children in four European countries: current patterns and future prospects. Eur J Ageing. 2004;1:54–63. doi: 10.1007/s10433-004-0003-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trifiletti R. Southern European welfare regimes and the worsening position of women. J Eur Social Policy. 1999;9:49–64. doi: 10.1177/095892879900900103. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vandecasteele L, Debels A (2004) Modelling attrition in the European community household panel: the effectiveness of weighting. http://epunet.essex.ac.uk/papers/vandecasteele_pap.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2011

- Vasconcelos P. Famílias complexas: tendências de evolução [complex families: evolution trends] Sociologia, problemas e práticas. 2003;43:83–96. [Google Scholar]

- Wall K. Portugal. In: Cizek B, Richter R, editors. Families in the EU15—policies, challenges and opportunities. Vienna: Austrian Institute for Family Studies; 2004. pp. 195–207. [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Logan J, Spitze G. The influence of parent and child needs on coresidence in middle and later life. J Marriage Fam. 1992;54:209–221. doi: 10.2307/353288. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilton V, Davey JA (2006) Grandfathers—their changing family roles and contributions. Blue Skies Report 3/06

- Yang Y, Fu WJ, Land KC. A methodological comparison of age-period-cohort models: the intrinsic estimator and conventional generalized linear models. Sociol Methodol. 2004;34:75–110. doi: 10.1111/j.0081-1750.2004.00148.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Land KC (2007) A simulation study of the intrinsic estimator for age-period-cohort analysis. http://www.princeton.edu/~sschulho/files/YSL_apcsim.pdf. Accessed 20 January 2011

- Yang Y, Fu WJ, Schulhofer-Wohl S, Land KC. The intrinsic estimator for age-period-cohort analysis: what it is and how to use it. Am J Sociol. 2008;113(6):1697–1736. doi: 10.1086/587154. [DOI] [Google Scholar]