Abstract

Emotions towards a relationship partner provide relevant and specific information about relationship quality. Based on this assumption the present study was performed to identify different types of emotional relationship quality of middle-aged adult children with their ageing parents. This was done by cluster analytic procedures in a sample of 1,208 middle-aged adult children (482 men, 726 women). Using ratings of positive and negative emotions towards their mother and father as grouping variables, the same four-cluster solution emerged for both the child–mother relationship and the child–father relationship. Clusters were labelled as amicable, disharmonious, detached and ambivalent relationships. Results showed that especially amicable relationships clearly prevailed followed by ambivalent, detached and disharmonious relationships. Clusters differed significantly with respect to gender of adult child, willingness to support, expected parental support and overt conflicts. In a cross-classification of cluster membership regarding the child–mother relationship (four clusters) and the child–father relationship (four clusters), all possible 16 combinations were observed, with a considerable degree of divergence regarding the type of relationship quality within the same family. Results are discussed with respect to types of emotional relationship quality, within family differences and the intrafamilial regulation of relationship quality.

Keywords: Intergenerational relations, Parent–child relations, Adult offspring, Emotions, Taxonomies

Introduction

Decreasing birth rates and increasing longevity have affected the shape of the family in most western societies in the sense that the size of generations has become smaller, but the number of living generations has increased. Having parents until late adulthood has almost become a ‘normal’ life situation, and compared to earlier times, the shared life span of parents and adult children is extended. At the same time this brings about new roles, expectations and potential sources of support but also sources of conflict and strain (see also Askham et al. 2007). Furthermore, longevity does not imply that there will be a life in old age without physical and functional impairments; quite the contrary is predicted (Baltes 1997). Associated with this, there will be an increased demand of care for older people in the future which will, a fortiori, challenge public expenditures since there will be a misfit between the so-called ‘productive’ and ‘non-productive’ groups within society in favour of the latter. This leaves doubts if the formal care system can be financed in the long run and if it will meet all the needs of older people. Many of the older persons will certainly have to rely on their informal social network (e.g. spouse and children) to receive various forms of support. Given these developments, intergenerational relations in families (and society) have increasingly gained importance, and especially the importance of intergenerational solidarity in alleviating the effects of population ageing and demographic changes is discussed not only within the social sciences, but also by policy makers (e.g. Arber and Attias-Donfut 2000; Commission of the European Communities 2005; Kohli and Künemund 2005; Lang and Perrig-Chiello 2005).

Several studies have provided evidence that the extent to which adult children support their ageing parents depends to a large extent on adult children’s emotional relationship quality with their parents (e.g. Merrill 1997; Rossi and Rossi 1990; Silverstein et al. 1995). In the present study, we will therefore focus on the emotional quality and further elaborate how different types of emotional relationships may be associated with different behaviour-related variables and expectancies concerning support exchange.

On the importance of emotions for the description of intergenerational relations

Scholars of intergenerational relations should be especially interested in the emotional aspect of relationship quality because emotions towards a relationship partner (e.g. admiration, love and hate) provide relevant and specific information about relationship quality. Cognitive appraisal theories of emotions (for an overview, see Roseman and Smith 2001) provide a deeper understanding of why this is so. According to an important variant of these theories, the belief-desire theory of emotion (e.g. Reisenzein 2009), emotions towards an imagined or a real ‘object’ arise out of two kinds of interrelated mental states of an individual, namely, beliefs about that object (e.g. behaviour or traits of a relationship partner) and desires concerning that object (e.g. that the relationship partner should behave in a certain way or that he or she should possess certain attributes). An emotion is assumed to occur as a consequence of a comparison process: positive emotions (e.g. gladness and gratitude) result from a perceived fulfilment, whereas negative emotions (e.g. disappointment and anger) result from a perceived frustration of an individual’s desires. Viewed from this perspective, emotions towards an ageing parent first indicate whether a parent is subjectively relevant to the child. Conversely, never feeling an emotion towards a parent would imply that the parent does not matter or no longer matters to the child at all. Second, an adult child’s positive emotions towards a parent indicate that the parent—as perceived by the child—fulfils an adult child’s desires; and negative emotions towards a parent indicate that the parent as perceived frustrates the child’s desires. Third, because emotions refer to ‘objects’ (e.g. events and persons) as mentally represented by the individual, they appear to be a valuable indicator of experienced relationship quality, especially when—as in adults’ relationships with their parents—direct (e.g. face to face) interactions are not very frequent. Fourth, one should notice that one cannot decide to switch on an emotion towards someone in the same way that one decides to visit that person (cf. Brandtstädter 2000). In other words, emotions reflect an involuntary aspect of relationship quality, which differs from other aspects (i.e. intentional behaviour). Taking for granted that adult children’s parent-related emotions convey important and specific information about the quality of the relationship with a parent, the present study was conducted to identify different types of emotional relationship quality of middle-aged adult children with their ageing parents and to describe the resulting types with respect to external variables.

Role of emotions in research on solidarity, conflict and ambivalence in intergenerational relations

Dimensional descriptions of intergenerational relations

In the intergenerational solidarity approach the emotional aspect of adult parent–child relations is reflected in one of its six well-known dimensions, namely, ‘affectual solidarity’. However, the corresponding measures are confined to just one or two kinds of positive emotions, that is, feeling close or feeling affection, and they disregard other emotions like admiration, pride or gratitude (see Bengtson and Mangen 1988; Lawton et al. 1994; Roberts and Bengtson 1991; Silverstein and Bengtson 1997). Our study will extend this aspect by considering a broader range of adult children’s positive emotions towards their ageing parents.

Research on conflict in intergenerational relations in later life has measured prevalence and/or magnitude of conflicts either globally as frequency of disagreements over certain topics (e.g. Suitor and Pillemer 1988) or with reference to behavioural indicators such as arguing (e.g. Buhl 2008). Negative emotions (e.g. anger, disappointment, hate and bitterness) have sometimes been theoretically conceived as elements of conflict, but to our knowledge they have not been empirically assessed as indicators of conflict. Our study will close this gap by measuring several conflict-related negative emotions of adult children towards their ageing parents.

Within the intergenerational ambivalence approach the aspect of psychological ambivalence (as distinguished from sociological ambivalence; cf. Pillemer and Lüscher 2004) is particularly relevant for our research: it is basically characterised by contradictory emotions towards a relationship partner. This is also reflected in the measures used (cf. Lettke and Klein 2004); either in direct measures referring to global perceptions of ‘mixed feelings’ (cf. Pillemer et al. 2007) or in indices derived from separate ratings of positive and negative ‘feelings’ about the relationship partner or the relationship. However, a closer inspection of the derived measures reveals that the items do not really assess emotions but rather perceptions of the respondent (e.g. adult child) of how the other person (e.g. parent) behaves towards him or her in a positive (understanding) or negative (criticising) manner (cf. Fingerman et al. 2008). In our study, we will assess separately adult children’s positive and negative emotions towards their parents and we expect to identify—besides other groups—an ambivalent group of adult children as well who are characterised by a combination of high positive and high negative emotions towards their parents.

Classification of intergenerational relations

Only a few studies have aimed at a classification of intergenerational relations, that is, these studies have tried to identify different types of intergenerational relations characterised by different combinations of values on dimensions of solidarity and/or conflict (e.g. by means of cluster or latent class analysis). Early studies used only solidarity dimensions as grouping variables so that only different types of child–parent solidarity relationships could emerge (e.g. Silverstein and Bengtson 1997). However, Bengtson and colleagues have widened their perspective over the past decade and considered ‘conflict’ as an additional dimension conceptually distinct from and presumably orthogonal to solidarity (e.g. Bengtson et al. 2002; Parrott and Bengtson 1999). Moreover, by cross-classifying both dimensions, Bengtson et al. (2000, p. 128) have suggested a parsimonious fourfold theoretical scheme of intergenerational relationship types: (1) high solidarity/high conflict, (2) high solidarity/low conflict, (3) low solidarity/low conflict and (4) low solidarity/high conflict. Findings from empirical studies (Giarrusso et al. 2005; Lang 2004; Steinbach 2008; van Gaalen and Dykstra 2006) provide ample evidence for the existence of these relationship types as well as data on their prevalence (see Table 1). However, the existing studies have certain limitations, in which the present research will address.

Table 1.

Types of relationships between adult children and their parents identified in empirical studies

| Positive dimensions (solidarity) | Negative dimensions (conflict) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Low | Inconsistent/intermediate | High | |

| Low | Civil (17%, 14%)a | Discordant (4%)b | Disharmonious (26%, 21%)c |

| Civil (28.4%, 24.2%)d | Disharmonious (14.2%, 19.7%)a | ||

| Detached distance (25.2%)e | Disharmonious (11.6%, 1.1%)d | ||

| Inconsistent/intermediate | Resilient giving (20.9%)e | Civil (17%, 14%)c | Strained altruism (21.7%)e |

| Harmonious (40%)b | Obligatory (16%)b | ||

| Affective (11%)d | |||

| High | Amicable (23%, 37%)c | Ambivalent (34%, 28%)c | |

| Amicable (47.2%, 21.9%)a | Ambivalent (13.6%, 4.8%)a | ||

| Amicable (51.6%, 68.4%)d | Ambivalent (8.4%, 6.3%)d | ||

| Close exchange (32.2%)e | Ambivalent (29%)b | ||

Note: The cells contain the names of the relationship types and their prevalence (in percent)

aSteinbach (2008): children’s perspective; first value: relation to mother, second value: relation to father

bvan Gaalen and Dykstra (2006): children’s perspective

cGiarrusso et al. (2005): parents’ perspective: first value: parents <65 years, second value: parents ≥65 years

dSteinbach (2008): children’s and parents’ perspective; first value: relation to mother, second value: relation to daughter

eLang (2004): children’s perspective

First, indicators for the positive and negative dimensions of relationship quality are not well-balanced within some studies: whereas ‘solidarity’ is frequently assessed by separate emotional and behavioural indicators, ‘conflict’ is assessed using only behavioural indicators (e.g. Giarrusso et al. 2005) or a composite indicator that combines behavioural and emotional components (e.g. Lang 2004; Steinbach 2008). In order to ensure a conceptually valid identification of psychologically ambivalent relationships (‘contradictory emotions’) and to provide a better comparability of measures across positive and negative dimensions of relationship quality, we will use emotional indicators for both dimensions—solidarity and conflict—and we expect to find types of emotional relationship quality corresponding to the aforementioned fourfold scheme. Second, the existing classification studies examined adult children’s relationship quality with only one parent (mother or father; Lang 2004; Steinbach 2008; van Gaalen and Dykstra 2006). In order to better reflect the complexity of child–parent relations in later life our study will examine adult children’s relationship quality with both their mother and their father. The different combinations of relationship types regarding both parents reflect the diversity of adult children’s relationships within families and can be systematised according to different aspects. One aspect is the valence pattern of the two relationships (i.e. both positive, both negative and mixed) which may have implications for adult children’s well-being. Another aspect is ‘filial favouritism’ (i.e. adult children’s favouring of the mother over the father or vice versa), which may have implications for the well-being of the favoured or disfavoured ageing parent. Whereas ‘parental favouritism’ (i.e. parents’ favouring of one child over the others) has received increasing interest during recent years (cf. Suitor et al. 2008), the complementary phenomenon of ‘filial favouritism’ has been totally neglected as an issue of research. Our study wants to provide some current data on the prevalence of filial favouritism.

Correlates of emotional relationship types

In our study, we expect to identify at least four types of emotional relationship quality with one’s parents. They should correspond to the fourfold theoretical scheme proposed by Bengtson et al. (2000), and here we refer to them with labels used in prior research (see Table 1). In the following, we will elaborate our assumptions about the relations between these types and demographic characteristics, behaviour-related variables, as well as expectancies about parental support.

Demographic characteristics

Age

With increasing age the probability of being confronted with a deteriorating physical and functional status of one’s parents and the inherent threat of losing them may enhance the frequency and intensity of adult children’s positive emotions towards their ageing parents; on the other hand, strains experienced in the relationship with increasingly impaired parents can evoke more negative emotions towards them. Using age in this sense as a proxy for certain aspects of the parent–child relation, we expect the mean age of adult children to be higher in ambivalent relationships and lower in detached relationships when compared to the other relationship types.

Gender

Relationships between daughters and mothers have been repeatedly found to be the closest kind of child–parent relationships (e.g. Lawton et al. 1994; Rossi and Rossi 1990). However, women have been found to experience more strain in relationships with parents due to normative expectations to provide support and care for their ageing parents while at the same time having to care for their own growing children (e.g. Brody 1999). Thus, we expect a higher probability for women than men to report an ambivalent relationship with their parents even though empirical studies have yielded mixed results on this (e.g. Fingerman et al. 2008; Willson et al. 2003). Moreover, we expect to find a smaller proportion of women than men in detached relationships, especially with their mother.

Behaviour-related variables and expectations

Behaviour-related variables

Theories of the motivational consequences of emotions (cf. Frijda 1996; Reisenzein 1996) assume that positive emotions towards someone—like affection, admiration, or gratitude—are linked to general action tendencies and desires like wanting to be near that person or to promote the well-being of that person. Conversely, negative emotions like disappointment, anger or hate are assumed to be linked to general action tendencies or desires like moving away from or interfering with the well-being of that person. Depending on external circumstances or other mental states of the individual (e.g. self-efficacy beliefs), these general action tendencies or desires are assumed to facilitate or inhibit more specific action tendencies or behaviours (e.g. willingness to support that person). In particular, we assume oppositely directed effects of positive versus negative emotions on willingness to support the ageing parents and on overt conflicts with them: willingness to support was expected to be facilitated by positive emotions and inhibited by negative emotions towards the parents. In contrast, overt conflicts were assumed to be facilitated by negative emotions, but inhibited by positive emotions towards parents. Based on this theoretical background, we expected systematic differences between different types of emotional relationships as identified in prior research (see Table 1) and behaviour-related phenomena in adult child–parent relations. Willingness to support one’s parents should be highest in amicable relations followed in descending degree by ambivalent, and then detached and disharmonious relationships. Overt conflicts with parents should be highest in disharmonious relationships followed in descending order by ambivalent, and then detached and amicable relationships.

Expectancies of parental support

Expectancy-value theories hold that persons develop generalised expectations concerning the outcomes of an interaction with specific situations or persons (Beckmann and Heckhausen 2008), and this notion is of special interest with respect to intergenerational support. In general, one may assume here that different types of emotional relationship will be associated with different expectancies of parental support in the case of need. Thus, expectancies of support by father and mother should be highest in amicable relations and they should be lowest in disharmonious and detached relations; these relations may be further moderated by health and functional condition of parents. No clear-cut relationship with support expectancies can be assumed with respect to relationships characterised as ambivalent since both kinds of expectations may be observed here.

Research questions

The present study was guided by the following research questions: (1) What types of emotional relationship quality towards both mother and father can be identified in middle-aged adult children? (2) To what extent do relationship types also differ with respect to external variables such as (a) demographic characteristics, (b) behaviour-related aspects of intergenerational relations (e.g. willingness to support and overt conflicts) and (c) expectancies of parental support?

Method

Sample

The present study is part of a larger research project on sibling and child–parent relations in adulthood in which the sampling was conducted. Thus, the participants had to have at least one living sibling and one living parent to be included in the sample. In a screening phase, an initial random sample of 7,950 adult inhabitants aged 40–50 years (50% male and 50% female) from a mixed urban and rural region of Germany was requested by mail to participate in a study on sibling and child–parent relations and, if they were willing to do so, also to indicate the number and gender of sibling(s), and whether their mother and/or father was still alive. Thus, for the present analysis a total of 1,208 adults (15.2%; one per family, with at least one sibling and one living parent) participated in 2000 (482 men, 726 women; age: M = 44.95, SD = 3.14). The majority of the respondents were either married or involved in long-term relationships (1,006, 83.3%); of the remaining respondents, 68 were never married (5.6%), 112 were either separated or divorced (9.3%), and 18 were widowed (1.5%). With regard to educational level and employment status, the following picture emerged: 442 respondents (34.9%) reported having completed the ‘Volkschule/Hauptschule’ (up to and including ninth grade), 399 respondents (33.0%) completed the ‘mittlere Reife’ (up to and including 10th grade) and 118 (9.8%) completed the ‘Abitur’ (up to and including 13th grade, the highest school-leaving degree in Germany). In addition, a total of 263 respondents (21.8%) completed college education. The largest portion of the sample were employed (n = 959, 79.4%), 141 respondents were homemakers (11.7%), and a small percentage was unemployed (n = 30, 2.5%) or retired (n = 18, 1.6%).

A total of 907 mothers (75.1%) and 605 fathers (50.1%) were still alive at the time of the survey, 494 respondents (40.1%) reported that both parents were still living. Respondents with two living parents filled out the measures for both parents; when one of the parents was no longer alive the respondents simply completed the measures for their living parent. A total of 365 respondents with a living mother (30.2%) and 371 of the respondents with a living father (30.8%) resided in the same community as their respective parent. Neither father (92%) nor mother (91.5%) had to be cared by family members or formal care institutions, a finding which indicates that functional and physical status of the majority of parents was evaluated as unproblematic.

Measures

Experienced emotional relationship quality with mother and father were measured by an Emotion Checklist (EC); a Behavioural Inventory was used to cover (a) overt conflicts with one’s mother and/or father, (b) willingness to support the father and/or mother, and (c) expected support by the mother and/or father. Both instruments are described in the following (see also Boll et al. 2003, 2005).

Emotional relationship quality to parents

The EC administered for mother and/or father was developed by the authors and comprised 26 positive and negative emotion terms. The selection of terms was guided by taxonomies of emotions, and for the checklist we selected those emotions which implied positive or negative evaluations of the parents and appeared to have different motivational implications as well (see Boll et al. 2003, 2005). Respondents were instructed to rate each emotion on 7-point Likert-type scales ranging from 1 (never) to 7 (always) with respect to how often they felt the given emotion when they thought about the person in question (i.e. mother and father). Principal axis analyses were computed for the EC, and they suggested a three-factor solution for both maternal and paternal relationships. The two factors with the highest eigenvalues were retained for the analyses; the same items showed significant loadings on these two factors for both the maternal and paternal version. Subscales were constructed by computing unit-weighted means across the variables, which composed of the respective varimax rotated factors. The first factor analytically derived scale consisted of seven items describing the frequency of emotions expressing attachment/closeness towards the parent (e.g. ‘deep affection’) and proved to be highly consistent in the maternal (M = 4.52, SD = 1.43, α = 0.94) as well as in the paternal version (M = 4.26, SD = 1.58, α = 0.96). The second scale comprised eight items describing the frequency of emotions expressing dislike (e.g. ‘angry’) regarding the mother (M = 2.34, SD = 1.15, α = 0.89) and father (M = 2.28, SD = 1.24, α = 0.91).

Behaviour-related correlates and expectancies of parental support

Two inventories were used to assess positive or negative behaviour-related aspects of the relationship with the mother and father. The inventories were identical and comprised 12 items for each parent which were rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (not at all true) to 6 (absolutely true). For the purpose of the present study, only a subset of eight items that was identical in the mother-related and father-related version was considered further and was used to construct three scales, each of which had been successfully used in prior research (see Boll et al. 2003, 2005). These eight items had been generated on the conceptual basis of functional solidarity (Lawton et al. 1994) and relationship conflict (Canary et al. 1995). A first scale described ‘Overt conflicts’ with father or mother, respectively, each form consisting of four items (e.g. ‘We fight a lot’); consistency coefficients of this scale were very high (maternal version: M = 2.58, SD = 1.20, α = 0.92; paternal version: M = 2.45, SD = 1.24, α = 0.94). ‘Willingness to support one’s parents’ was measured by two items for both mother and father (e.g. ‘I would drop everything to help my father in hard times’), and both versions proved to be very highly consistent (maternal version: M = 5.18, SD = 1.03, α = 0.86; paternal version: M = 5.02, SD = 1.26, α = 0.93). ‘Expectancies concerning parental support’ were measured by two items (e.g. ‘When I need help, my mother helps me as good as she can’); this scale showed high consistency in both versions as well (maternal version: M = 4.78, SD = 1.39, α = 0.90; paternal version: M = 4.66, SD = 1.52, α = 0.92).

Strategy of data analysis

In order to identify types of emotional relationship quality of adult children towards their ageing parents we performed two hierarchical cluster analyses using squared Euclidian distances and the Ward algorithm that were further validated by non-hierarchical k-means clustering. Z-standardised attachment/closeness and dislike scales were entered as grouping variables. The first analysis for identifying types of emotional relationship quality with the mother was performed using the subsample of adult children with at least their mothers still alive (n = 907), and the second analysis for identifying types of emotional relationship quality with the father was performed using the subsample of adult children with at least their fathers still alive (n = 605). We preferred to use these two larger subsamples with at least one living parent instead of just the smaller one with both parents still living (n = 494) because the larger subsample sizes provided more power to the statistical analyses. In order to identify different patterns of adult children’s emotional relationship towards both parents within families, we made a cross-classification of cluster memberships for emotional relationship quality with mother and father; this analysis was of course based on the subsample of adult children with both parents still alive.

Results

Types of relationship quality with mother and father

Identifying clusters of emotional relationships

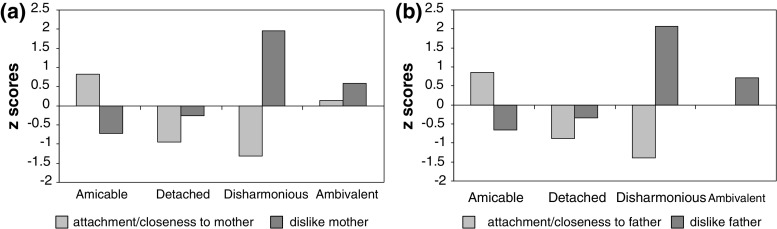

For both parents, a four cluster solution provided the best compromise between low error and parsimony. The mean scores on attachment/closeness and dislike in the four clusters found for both the maternal and paternal relationship are shown in Fig. 1. Here, it becomes evident that the patterns of relationship quality with mother and father were found to be almost identical. For maternal and paternal emotional relationships, the clusters were designated as follows:

Amicable relationship: Above average scores on attachment/closeness (maternal: M = 0.82, SD = 0.49; paternal: M = 0.85, SD = 0.49) and low scores on dislike (maternal: M = −0.72, SD = 0.33; paternal: M = −0.65, SD = 0.34) characterised this cluster. It constituted the largest group for both mother and father (maternal: n = 381—42.0%; paternal: n = 262—43.3%). Standard deviations for both cluster variables were notably below 1 concerning both parental relations, indicating a homogeneous cluster composition.

Detached relationship: Subjects within this second largest group (maternal: n = 213—23.5%; paternal: n = 152—25.1%) showed below average scores both on attachment/closeness (maternal: M = −0.94, SD = 0.61; paternal: M = −0.88, SD = 0.61) and on dislike (maternal: M = −0.26, SD = 0.53; paternal: M = −0.34, SD = 0.47) indicating a detached relationship. Again, the size of standard deviations within this group indicated a homogeneous cluster.

Disharmonious relationship: A smaller number of respondents (maternal: n = 108—11.9%; paternal: n = 65—10.7%) reported low levels on attachment/closeness (maternal: M = −1.31, SD = 0.68; paternal: M = −1.39, SD = 0.52) and high scores on dislike (maternal: M = 1.95, SD = 0.70; paternal: M = 2.06, SD = 0.73) indicating a disharmonious relationship. The within-group variance of the ‘dislike’ score in this special group was only slightly lower than SD = 1.00 indicating higher heterogeneity of the dislike scores within this cluster.

Ambivalent relationship: Subjects in the fourth cluster showed average scores on attachment/closeness (maternal: M = 0.14, SD = 0.49; paternal: M = −0.01, SD = 0.48) while having higher dislike scores (maternal: M = 0.59, SD = 0.51; paternal: M = 0.71, SD = 0.54). Given that the magnitude of the two emotions is not extremely high in the present sample, these clusters represent ‘moderate’ and not ‘extreme’ ambivalence. A total of 205 (22.6%) respondents reported this relationship pattern with respect to their mother and 126 respondents (20.8%) reported such a profile with respect to their father.

Fig. 1.

Patterns of relationship quality to mother (a) and father (b) based on indicators of attachment/closeness and dislike

A comparison of cluster allocations between the two solutions showed that a comparable number of respondents were observed in each of the four clusters obtained for mother and father. Cluster allocation thus did not significantly differ with respect to parent gender (χ2(3) = 0.21, n.s.).

Types of relationship quality with both parents

For those respondents with both parents alive, cluster allocations for father and mother were cross-tabulated in a further step of analysis; results of this analysis are described in Table 2. The table contains the absolute and relative frequencies observed across the clusters.

Table 2.

Cross-tabulation of cluster memberships for maternal and paternal clusters

| Father | Mother | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ambivalent | Amicable | Detached | Disharmonious | |||

| Ambivalent | N | 38 | 32 | 19 | 14 | 103 |

| % of total | 7.7 | 6.5 | 3.8 | 2.8 | 20.9 | |

| Amicable | N | 32 | 158 | 21 | 11 | 222 |

| % of total | 6.5 | 32.0 | 4.3 | 2.2 | 44.9 | |

| Detached | N | 17 | 20 | 72 | 13 | 122 |

| % of total | 3.4 | 4.0 | 14.6 | 2.6 | 24.7 | |

| Disharmonious | N | 11 | 8 | 10 | 18 | 47 |

| % of total | 2.2 | 1.6 | 2.0 | 3.6 | 9.5 | |

| Total | N | 98 | 218 | 122 | 56 | 494 |

| % of total | 19.8 | 44.1 | 24.7 | 11.3 | 100.0 | |

Note: Italics indicate convergence in relationship quality with both parents

As a first general finding one may hold that there is a great variety of adult children’s relationships within families: all cells within the table were occupied, thus there was no configuration of relationship quality that was not represented within the present sample. Second, even though convergence in the type of relationship quality with both parents was predominant (57.9%), there was also a considerable degree of divergence (42.1%). Overall χ2 analysis was significant, indicating the systematic association between the relationship types (χ2(9) = 210.23, Cramer’s V = 0.38, p < 0.00). Third, if one considers the valence pattern of adult children’s relationships with both parents, the mixed patterns were most frequent (37.3%).1 It was followed by the combinations of ‘both relationships positive’ (i.e. amicable) with 32% and ‘both relationships negative’ (i.e. detached or disharmonious) with 22.8%. Least frequent were ambivalent relationships with both parents (7.7%). Fourth, we found evidence for a considerable amount of filial favouritism as indicated by a positive (i.e. amicable) relationship with one parent and an at least partly negative (i.e. ambivalent or detached or disharmonious) relationship with the other parent: the frequency of ‘mother favoured over father’ was 12.1% and the frequency of ‘father favoured over mother’ was 13%, which adds up to a total of 25.1% of adult children in our sample.

Correlates of relationship types

Demographic characteristics

In a subsequent step of analysis, it was tested whether the clusters differed in age and gender of adult children. The associated frequencies and statistics are shown in Table 3 for the relationship with mothers and in Table 4 for the relationships with fathers. Age differences were not found between clusters for neither maternal (F(3, 893) = 0.33; n.s.) nor paternal relations (F(3, 595) = 0.30; n.s.). A small gender effect was observed between clusters for both relationship with the mother (χ2(3) = 27.86, Cramer’s V = 0.17, p < 0.01) and relationship with the father (χ2(3) = 12.65, Cramer’s V = 0.14, p < 0.01). The significant χ2 values were due to a deviation of the gender composition within the ‘detached relationship’ cluster from the distribution within the remaining clusters indicating that men reported detached relations more frequently than women.

Table 3.

Structural differences between maternal relationship clusters

| Correlates | Clusters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amicable | Detached | Disharmonious | Ambivalent | |

| N | 381 (42.0%) | 213 (23.5%) | 108 (11.9%) | 205 (22.6%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 151 (39.6%) | 116 (54.5%) | 32 (31.4%) | 67 (32.7%) |

| Female | 230 (60.4%) | 97 (45.5%) | 76 (70.4%) | 138 (67.3%) |

| Age | ||||

| M | 44.75 | 44.65 | 44.46 | 44.81 |

| SD | 3.01 | 3.01 | 2.97 | 3.25 |

| Expected supporta | ||||

| M | 0.56 | −0.51 | −1.18 | −0.09 |

| SD | 0.53 | 1.01 | 1.07 | 0.80 |

| Willingness to supporta | ||||

| M | 0.45 | −0.51 | −0.93 | 0.17 |

| SD | 0.52 | 1.20 | 1.23 | 0.66 |

| Overt conflictsa | ||||

| M | −0.52 | −0.01 | 1.37 | 0.40 |

| SD | 0.64 | 0.89 | 0.90 | 0.76 |

Note: a z-scores

Table 4.

Structural differences between paternal relationships clusters

| Correlates | Clusters | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amicable | Detached | Disharmonious | Ambivalent | |

| N | 262 (43.2%) | 152 (25.1%) | 65 (10.7%) | 126 (20.8%) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 93 (35.5%) | 78 (51.3%) | 26 (40.0%) | 42 (33.3%) |

| Female | 169 (64.5%) | 74 (48.7%) | 39 (60.0%) | 84 (66.7%) |

| Age | ||||

| M | 44.24 | 44.51 | 44.31 | 44.20 |

| SD | 3.12 | 3.13 | 2.92 | 3.12 |

| Expected supporta | ||||

| M | 0.60 | −0.56 | −1.28 | 0.07 |

| SD | 0.51 | 1.03 | 0.94 | 0.75 |

| Willingness to supporta | ||||

| M | 0.50 | −0.51 | −0.97 | 0.07 |

| SD | 0.48 | 1.15 | 1.31 | 0.74 |

| Overt conflictsa | ||||

| M | −0.52 | −0.24 | 1.40 | 0.64 |

| SD | 0.58 | 0.86 | 0.97 | 0.82 |

Note: a z-scores

Willingness to support and expectancies of parental support

These variables were used as further correlates of cluster allocation; the mean values of these indicators within the four maternal clusters are depicted in Fig. 2a, Table 3 and within the paternal clusters in Fig. 2b, Table 4, respectively. Due to non-normality of the dependent variables and an increased heterogeneity of error variances, both multivariate and univariate analyses of variance were at risk of producing unreliable findings. Since there is no robust test for MANOVA, univariate ANOVAS were cross-checked with robust Welch tests to test group differences (see Tomarken and Serlin 1986). Regarding type I error probabilities, no differences between the results of the ANOVAs and the Welch tests could be found. For the sake of conciseness, only the results of the ANOVAs are presented here. Post-hoc pair-wise comparisons between groups were carried out using Tamhane’s T2 test. It goes without saying that the reported effect size (η2) values thus have only an illustrative character.

Fig. 2.

Mean values of willingness to support, of expected support, and of overt conflicts in four relationship quality clusters on a maternal and b paternal relations

Significant differences were found between the clusters of maternal relationship quality in willingness to support (F(3, 901) = 103.68, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.25) and expectations of maternal support (F(3, 901) = 173.04, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.36). The same significant effects could be observed for the paternal relationship quality (willingness to support: F(3, 601) = 76.37, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.28; expected support: F(3, 601) = 138.74, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.41). Post-hoc comparisons for the maternal relationship showed that all four clusters differed significantly in reported willingness to support and expected support as well (p < 0.01). Willingness to support as well as expected support were highest in the ‘amicable relationship’ cluster, followed by ambivalent, detached and disharmonious relationships. In one aspect, this pattern of results is different in the paternal cluster solution: detached and disharmonious relationship clusters did not significantly differ in the willingness to support one’s father.

Overt conflicts

Significant differences were found in the degree of overt conflicts with the mother (F(3, 900) = 215.39, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.42) versus with the father (F(3, 601) = 149.69, p < 0.01, η2 = 0.43). The average scores of these indicators within the clusters of relationship quality are shown in Fig. 2a, Table 3 for relationships with the mothers and in Fig. 2b, Table 4 for relationships with the fathers. Mean differences between all four clusters were significant for relationship quality with both mother and father (p < 0.01). Overt conflicts yielded the highest scores in the ‘disharmonious relationship’ group followed by decreasing scores in the ambivalent, detached and amicable relationship groups. Within disharmonious and ambivalent relationships, positive mean z-values indicated quite a pronounced degree of overt conflicts, whereas negative mean values were found in the group of detached and amicable relationship.

Discussion

Based on the premise that emotions towards a relationship partner provide relevant information about relationship quality, the present study used adult children’s ratings of positive and negative emotions towards their parents as grouping variables to identify different types of emotional relationship quality with the mother and the father. In this respect, our classification study differed from prior ones which were based either on behavioural indicators only (van Gaalen and Dykstra 2006) or on composite variables combining emotional and behavioural measures (Lang 2004; Steinbach 2008).

Types of emotional relationship quality with parents

Referring to the solidarity-conflict scheme of intergenerational relations (Bengtson et al. 2000) we expected at least four types of emotional relationship quality to emerge which should be characterised by high versus low positive and negative emotions towards the parents. Our findings were in line with this expectation: concerning relationships with both mothers and fathers four clusters emerged. For relationships with both parents, a relatively high prevalence of amicable relationships was found, followed by a smaller proportion of both detached and ambivalent relations; disharmonious relationships were least prevalent within the sample.

Two of these relationship types, namely, the ambivalent and the detached relationships, deserve a more extensive discussion. The proportion of relations of the ambivalent type, which amounts to more than 20% of all adult child–parent relationships, shows that the growing interest of researchers in ambivalent relations is quantitatively well-founded. However, our prevalence rates, as well as those from prior classification studies (cf. Giarrusso et al. 2005; Steinbach 2008; van Gaalen and Dykstra 2006), question the quite extreme theoretical position according to which all adult parent–child relations should be qualified as ambivalent (cf. Lüscher and Pillemer 1998): an ambivalent relation is just one type of intergenerational relationship among others. Furthermore, types of relationship in general should not be conceptualised as static categories but much more as subject to change as we will elaborate below.

Detached relationships have been characterised by low scores on attachment/closeness and a rather low score on dislike towards parents. Its prevalence rate of more than 20% of all relations with mothers and fathers is considerable, and these relationships should be examined more thoroughly in future research. The belief-desire theory of emotion (e.g. Reisenzein 2009) suggests that a lack of emotions towards parents results from a lack of parent-related desires (e.g. to be close to them, be loved and accepted by them; that they are happy and successful)—within this framework being detached signifies that one no longer has desires concerning one’s parents. It can be derived from theories of goal pursuit and goal adjustment across the life course (e.g. Brandtstädter and Rothermund 2002) that a lack of parent-related desires may be the result of adjustment to insurmountable discrepancies between such desires and the actual behaviour or constitution of the parents. Thus, adult children may modify or even give up their desires in order to diminish or resolve such discrepancies. Future research should examine more thoroughly the content and the dynamics underlying these desires in the developmental course of adult children–parent relationships.

Within family differences in types of emotional relationship quality

In a cross-classification of cluster membership regarding adult children’s relationship with mother and with father, all possible 16 combinations were observed which documents the large diversity of adult children’s relationships with both parents. Given that in more than 40% of the observed relationships the type of adult children’s relationships towards both parents differ within a family, it would be a mistake for researchers or practitioners to infer the quality of relationship with parents from reports about relationship quality with one parent only. With respect to assessment issues, one is well advised to use separate measures for relationships with the mother and the father and not to use global indices for child–parents relationships.

We identified two combinations of adult children’s relationships with both parents which deserve further attention because of possible negative effects on subjective well-being: Adult children (a) with negative and (b) with ambivalent relationships regarding both mother and father; these groups add up to approximately one-third of our sample. Several studies have provided evidence that people with negative and with ambivalent social relationships are characterised by a lower subjective well-being (Pinquart and Sörensen 2000). Future research should examine whether family members involved in the aforementioned combinations of emotional relationship types regarding parents differ in their subjective well-being from family members involved in the more positive combinations.

Filial favouritism (i.e. adult children’s favouring of mother over father or vice versa) was another interesting phenomenon that emerged in our cross-classification: to our knowledge this has not yet been examined in later life families. Filial favouritism as indicated by a positive (i.e. amicable) relationship with one parent and an at least partly negative (i.e. ambivalent or detached or disharmonious) relationship with the other was found in approximately 25% of our sample: About one-half of this group favoured mother over father, and the other half favoured father over mother. Research on the analogous phenomena of parental favouritism or differential parental treatment (for an overview, see Suitor et al. 2008) leads us to complementary questions about filial favouritism: to what degree is this phenomenon not just reported by adult children, but also perceived and evaluated by the parents? According to cognitive approaches of emotion and action, the perceptions and evaluations of the parents are important because they can be regarded as the primary determinants of how the parents will respond to filial favouritism. In order to what degree does filial favouritism have a negative effect on parents’ relationship with adult children as well as on the relationship between mother and father, and on the individual (favoured or disfavoured) parent?

Types of emotional relationship quality and behaviour-related phenomena

Based on models of the motivational consequences of emotions, we expected that willingness to support should be highest in amicable relations followed in descending degree by ambivalent and detached and then disharmonious relationships; overt conflicts with parents were expected to be highest in disharmonious relationships followed in descending order by ambivalent and detached and then amicable relationships. By and large our findings correspond with these expectations and lend support to the underlying reasoning. In ambivalent relationships in which dislike is high and attachment/closeness is moderately high the oppositely directed effects of the two kinds of emotions cancel each other out with the result of a medium degree of willingness to support and overt conflicts. In detached relationships in which both kinds of emotions are low, on the one hand, willingness to support was not high due to lacking attachment/closeness and on the other hand, it was not low due to lack of dislike; moreover, overt conflict did not obtain high values due to lack of dislike and it did not show pronouncedly low values due to lack of attachment/closeness. This results in an intermediate degree of both willingness to support and overt conflicts in detached relationships, too.

The preceding findings advise one not to simply conclude that ambivalent relationships in the sense of mixed emotions (high attachment/closeness, high dislike) are also ambivalent in the sense of mixed behaviours (high support, high conflict). Rather emotional ambivalence is linked to a kind of ‘compromise’ regarding behaviour-related phenomena: a medium level of willingness to support and a medium level of overt conflicts. In a similar way, one should not conclude that detached relationships in the sense of low attachment/closeness and low dislike are also detached in the sense of low willingness to support and low conflict. Emotional detachment, too, is linked to a middle course: a medium level of willingness to support and a medium level of overt conflicts (because both facilitating and inhibiting emotions are missing).

Limitations and further suggestions for future research

As our study was part of larger research project on sibling and child–parent relations, the participants had to have at least one living sibling and one living parent to be included in the sample. Thus, the present results on adult children’s emotional relationship quality are confined to this population. Generalisations to adult children without siblings should be done with great caution only and future research should aim at a replication of findings with samples of only children. Another point that deserves discussion is the seemingly low response rate of our study (15.2%) which has to be put into perspective. The initial random sample of 7,950 adults was not preselected with respect to adults having at least one sibling and one living parent. Two additional figures may further help to put this response rate into perspective: according to the German survey of ageing, only 81.2% of German adults between 40 and 54 (the age group closest to ours) have a sibling; only 71.1% of the same age group has at least one living parent (Kohli et al. 2005; Künemund and Hollstein 2005). Thus, the number of adults in the initial random sample who would have been eligible given our criteria can reasonably be assumed to be substantially lower than 7,950 and, thus, the actual response rate should be substantially higher than our percentage indicates. Nevertheless, one cannot exclude a certain selectivity resulting from the fact that our sample—as is ubiquitous in the social sciences—is composed of ‘volunteer subjects’ (cf. Rosnow and Rosenthal 1997); this has to be taken into account when generalising our results.

Regarding measures, one limitation is that we assessed willingness and expectancies regarding support with rather short scales (two items each). Even though the internal consistencies of these scales are good one may still wonder whether the measurement of the support-related variables was sufficiently comprehensive (e.g. regarding the various kinds of support). Another limitation regarding measures is that we used self-reports of adult children exclusively. Thus, it may well be that the strength of relationships found, for instance, between types of emotional relationship quality and children’s conflict behaviours, willingness or expectancies concerning support is somewhat inflated due to shared method variance. Future research could improve on that by using reports from different informants (e.g. emotions as reported by adult children and behaviours as reported by their parents).

The present study assessed emotional relationships of middle-aged adult children (one per family) towards their ageing parents at one point of measurement. This implies certain limitations which should be addressed in subsequent research. First, in families with more than one adult child, the type of emotional relationship quality towards parents may differ among their various children. Future studies should collect data from several children (cf. van Gaalen et al. 2008) and assess the extent of within family differences regarding adult children’s emotional relationship quality towards their parents and their possible combined effects on family relationships and on individual family members. Second, our analysis on types of adult children’s emotional relationship quality towards their parents needs to be supplemented by an examination of the types of emotional relationship quality that older parents report towards their adult children. In the light of the intergenerational stake effect (e.g. Giarrusso et al. 1995), it can be expected that ageing parents’ emotional relationship quality with their adult children is more positive (e.g. greater proportion of amicable and a smaller proportion of disharmonious and detached relationships) than adult children’s emotional relationship quality with their parents. Third, from a developmental point of view, the type of adult children’s emotional relationship quality towards the parents may change across the life course due to changes of personal and environmental conditions on part of the adult children and/or their parents.

All aforementioned points highlight the importance of relationship regulation within families as well as the complexity of these relations since relationship regulation involves different partners with different normative, familial and generational roles. We follow this line of thought with some tentative considerations. With respect to the process of relationship regulation one may hypothesise that amicable and detached relationships constitute the starting and endpoint of a dysfunctional regulation process. An amicable relation may be challenged by stressors such as care giving which may result in ambivalent emotions of one or both partners if the personal and external resources are not sufficient enough to deal with the demands associated with the changed life situation. Adaptive efforts within this context include individual coping strategies—both of a problem- and an emotion-focused function—but also dyadic coping efforts (as it has been described for couples; Revenson et al. 2005) as well as polyadic efforts of the whole involved family system. Stressors may comprise care giving but several other stressors across the life span may be listed here as well (e.g. value discrepancies, perceived differential treatment of siblings and rejecting in-laws); in general, all issues that are central to the self-definition of the involved partners may be named here.

Functional regulation of ambivalence in a sense of meeting individual criteria of relationship regulation may allow re-establishing an amicable relation, whereas dysfunctional regulation may result in more pronounced disharmonious feelings of one or both partners. Disharmonious feelings may, more than other emotions, urge adaptive efforts given that these may result in high arousal challenging the individual well-being to a higher degree than amicable or ambivalent emotions. Disharmonious feelings may finally result in detached relations if further regulation efforts are not successful in re-establishing a status quo ante. An oscillation between disharmonious and ambivalent emotions may also be imaginable, allowing an individual to escape the strain of tense emotions for a specific period.

Such a dynamic process view of relationship types maintains that, depending on the regulative efforts, changes in relationship quality may always be possible—and even detached relations may be subject to change if personal and contextual conditions within families change. It also emphasizes that the regulation of relationships is a polyadic process which may consist of several differential outcomes for the involved persons depending on their adaptive efforts and subjective criteria of success. Further research will certainly have to put emphasis on these complex and interrelated processes within families.

Taken together, the present study showed that an assessment and classification of adult children’s emotional relationship quality towards ageing parents is viable. Interesting findings on qualitative differences of relationship types and their prevalence rates emerged as well as findings on links with behaviour-related phenomena. The results give rise to several questions for future research, and answering them may greatly enhance our understanding of the complexities of late life family relationships.

Acknowledgements

This study is part of a research project entitled ‘Parental Differential Treatment in Middle Adulthood: Dyadic and Longitudinal Analyses’, which was conducted at the University of Trier (Germany). It was supported by a grant from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to the first author (DFG; FE 502/2-3). We thank Lisa Trierweiler for her very helpful support in preparing the English manuscript.

Footnotes

They included three subgroups of relationships: (a) positive with parent A and negative with parent B (i.e. amicable combined with either detached or disharmonious: 12.1%), (b) ambivalent with parent A and positive with parent B (13.0%) and (c) ambivalent with parent A and negative with parent B (12.2%).

References

- Arber S, Attias-Donfut C, editors. The myth of generational conflict. London: Routledge; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Askham J, Ferring D, Lamura G. Personal relationships in later life. In: Bond J, Peace SM, Dittman-Kohli F, Westerhof GJ, editors. Ageing in society: an introduction to social gerontology. 3. London: Sage; 2007. pp. 186–208. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes PB. On the incomplete architecture of human ontogeny: selection, optimization, and compensation as foundation of developmental theory. Am Psychol. 1997;52:366–380. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.52.4.366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckmann J, Heckhausen H. Motivation as a function of expectancy and incentive. In: Heckhausen J, Heckhausen H, editors. Motivation and action. Berlin: Springer; 2008. pp. 99–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Mangen DJ. Family intergenerational solidarity revisited. In: Mangen DJ, Bengtson VL, Landry PH, editors. Measurement of intergenerational relations. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 1988. pp. 222–238. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Biblarz T, Clarke E, Giarrusso R, Roberts R, Richlin-Klonsky J, Silverstein M. Intergenerational relationships and aging: families, cohorts, and social change. In: Clair JM, Allman RM, editors. The gerontological prism: developing interdisciplinary bridges. Amityville: Baywood; 2000. pp. 115–147. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL, Giarrusso R, Mabry JB, Silverstein M. Solidarity, conflict, and ambivalence: complementary or competing perspectives on intergenerational relationships. J Marriage Fam. 2002;64:568–576. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2002.00568.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boll T, Ferring D, Filipp S-H. Perceived parental differential treatment in middle adulthood: curvilinear relations with individual’s experienced relationship quality to sibling and parents. J Fam Psychol. 2003;17:472–487. doi: 10.1037/0893-3200.17.4.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boll T, Ferring D, Filipp S-H. Effects of parental differential treatment on relationship quality with siblings and parents: justice evaluations as mediators. Soc Justice Res. 2005;18:155–182. doi: 10.1007/s11211-005-7367-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J. Emotion, cognition, and control: limits of intentionality. In: Perrig WJ, Grob A, editors. Control of human behavior, mental processes, and consciousness. Essays in honor of the 60th birthday of August Flammer. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 2000. pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, Rothermund K. The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: a two-process framework. Dev Rev. 2002;22:117–150. doi: 10.1006/drev.2001.0539. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brody EM. Women in the middle: their parent-care years. New York: Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Buhl HM. Significance of individuation in adult child–parent relationships. J Fam Issues. 2008;29:262–281. doi: 10.1177/0192513X07304272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Canary DJ, Cupach WR, Messman SJ. Relationship conflict: conflict in parent–child, friendship, and romantic relationships. Thousands Oaks: Sage; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Commission of the European Communities . Green paper “Confronting demographic change: a new solidarity between generations”. Brussels: Communication from the Commission; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Fingerman KL, Pitzer L, Lefkowitz ES, Birdit KS, Mroczek D. Ambivalent relationship qualities between adults and their parents: implications for the well-being of both parties. J Gerontol B Psychol. 2008;61:P362–P371. doi: 10.1093/geronb/63.6.p362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frijda NH. Passions: emotion and socially consequential behavior. In: Kavanaugh RD, Zimmerberg B, Fein V, editors. Emotion: interdisciplinary perspectives. Mahwah: Erlbaum; 1996. pp. 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso R, Stallings M, Bengtson VL. The “intergenerational stake” hypothesis revisited: parent–child differences in perceptions of relationships 20 years later. In: Bengtson VL, Schaie KW, Burton L, editors. Intergenerational issues in aging. New York: Plenum; 1995. pp. 227–263. [Google Scholar]

- Giarrusso R, Silverstein M, Gans D, Bengtson VL. Ageing parents and adult children: new perspectives on intergenerational relationships. In: Johnson ML, Bengtson VL, Coleman PG, Kirkwood TBL, editors. Cambridge handbook of age and ageing. Cambridge: University Press London; 2005. pp. 413–421. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M, Künemund H, editors. Die zweite Lebenshälfte. Gesellschaftliche Lage und Partizipation im Spiegel des Alters-Survey [The second half of life. Social situation and participation as reflected in the ageing survey] 2. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kohli M, Künemund H, Motel A, Szydlik M. Generationenbeziehungen [Intergenerational relations] In: Kohli M, Künemund H, editors. Die zweite Lebenshälfte. Gesellschaftliche Lage und Partizipation im Spiegel des Alters-Survey. 2. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2005. pp. 176–211. [Google Scholar]

- Künemund H, Hollstein B. Soziale Beziehungen und Unterstützungsnetzwerke [Social relationships and support networks] In: Kohli M, Künemund H, editors. Die zweite Lebenshälfte. Gesellschaftliche Lage und Partizipation im Spiegel des Alters-Survey. 2. Wiesbaden: VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften; 2005. pp. 212–276. [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR. The filial task in midlife: ambivalence and the quality of adult children’s relationships with their older parents. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Intergenerational ambivalences: new perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Oxford: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 183–206. [Google Scholar]

- Lang FR, Perrig-Chiello P. Editorial to the special section on intergenerational relations. Eur J Ageing. 2005;2:159–160. doi: 10.1007/s10433-005-0010-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawton L, Silverstein M, Bengtson VL. Affection, social contact, and geographic distance between adult children and their parents. J Marriage Fam. 1994;56:57–68. doi: 10.2307/352701. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lettke F, Klein DM. Methodological issues in assessing ambivalences in intergenerational relations. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Intergenerational ambivalences: new perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Amsterdam: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher K, Pillemer K. Intergenerational ambivalence: a new approach to the study of parent–child relations in later life. J Marriage Fam. 1998;60:413–425. doi: 10.2307/353858. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Merrill D. Caring for elderly parents: juggling work, family, and caregiving in middle and working class families. Westport: Auburn House/Greenwood; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott TM, Bengtson VL. The effects of earlier intergenerational affection, normative expectations, and family conflict on contemporary exchanges of help and support. Res Aging. 1999;21:73–105. doi: 10.1177/0164027599211004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Lüscher K. Introduction: ambivalence in parent–child relations in later life. In: Pillemer K, Lüscher K, editors. Intergenerational ambivalences: new perspectives on parent–child relations in later life. Oxford: Elsevier; 2004. pp. 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pillemer K, Suitor JJ, Mock SE, Sabir M, Pardo TB, Sechrist J. Capturing the complexity of intergenerational relations: exploring ambivalence within later-life families. J Soc Issues. 2007;63:775–791. [Google Scholar]

- Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Influences of socioeconomic status, social network, and competence on subjective well-being in later life: a meta-analysis. Psychol Aging. 2000;15:187–224. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.15.2.187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reisenzein R. Emotional action generation. In: Battmann W, Dutke S, editors. Processes of the molar regulation of behaviour. Lengerich: Pabst Science Publishers; 1996. pp. 151–165. [Google Scholar]

- Reisenzein R. Emotions as metarepresentational states of mind: naturalizing the belief-desire theory of emotion. Cogn Syst Res. 2009;10:6–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cogsys.2008.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Revenson TA, Kayser K, Bodenmann G. Couples coping with stress: emerging perspectives on dyadic coping. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts REL, Bengtson VL. Is intergenerational solidarity a unidimensional construct? A second test of a formal model. J Gerontol B Psychol. 1991;45:S12–S20. doi: 10.1093/geronj/45.1.s12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roseman I, Smith CA. Appraisal theory: overview, assumptions, varieties, controversies. In: Scherer KR, Schorr A, Johnstone T, editors. Appraisal processes in emotion: theory methods research. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001. pp. 3–19. [Google Scholar]

- Rosnow RL, Rosenthal R. People studying people: artefacts and ethics in behavioral research. New York: W.H. Freeman; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Rossi AS, Rossi PH. Of human bonding: parent–child relations across the life course. New York: Aldine de Gruyter; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Bengtson VL. Intergenerational solidarity and the structure of adult child–parent relationships in American families. Am J Sociol. 1997;103:429–460. doi: 10.1086/231213. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Silverstein M, Parrott T, Bengtson V. Factors that predispose middle-aged sons and daughters to provide social support to older parents. J Marriage Fam. 1995;57:465–475. doi: 10.2307/353699. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Steinbach A. Intergenerational solidarity and ambivalence: types of relationships in German families. J Comp Fam Stud. 2008;30:115–127. [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Pillemer K. Explaining intergenerational conflict. When adult children and elderly parents live together. J Marriage Fam. 1988;50:1037–1047. doi: 10.2307/352113. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Suitor JJ, Sechrist J, Plikuhn M, Pardo ST, Pillemer K. Within-family differences in parent–child relations across the life course. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 2008;17:334–338. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00601.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tomarken AJ, Serlin RC. Comparison of ANOVA alternatives under variance heterogeneity and specific noncentrality structures. Psychol Bull. 1986;99:90–99. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.99.1.90. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen RI, Dykstra PA. Solidarity and conflict between adult children and parents: a latent class analysis. J Marriage Fam. 2006;68:947–960. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00306.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- van Gaalen RI, Dykstra PA, Flap H. Intergenerational contact beyond the dyad: the role of the sibling network. Eur J Ageing. 2008;5:19–29. doi: 10.1007/s10433-008-0076-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willson AE, Shuey KM, Elder GH. Ambivalence in the relationship of adult children to aging parents and in-laws. J Marriage Fam. 2003;65:1055–1072. doi: 10.1111/j.1741-3737.2003.01055.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]