Abstract

This article focuses on Nordic eldercare workers and their experiences of working conditions in times of change and reorganisation. In recent years New Public Management-inspired ideas have been introduced to increase efficiency and productivity in welfare services. These reforms have also had an impact on day-to-day care work, which has become increasingly standardized and set out in detailed contracts, leading to time-pressure and an undermining of care workers’ professional discretion and autonomy. The empirical data comes from a survey of unionised eldercare workers in home care and residential care in Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden (N = 2583) and was analysed by bi- and multi-variate methods. The care workers reported that they found their working conditions physically and mentally arduous. They had to a great extent experienced changes for the worse in terms of working conditions and in their opportunity to provide good quality care. In addition, the majority felt they did not receive support from their managers. An alarming finding was that one out of three care workers declared that they had seriously considered quitting their jobs. Care workers with multiple problems at work were much more likely to consider quitting, and the likelihood was increasing with the number of problems reported. Furthermore, care workers lacking support from their managers had double odds of wanting to quit. The Nordic welfare states with growing older populations are facing challenges in retaining care staff in the eldercare services and ensuring they have good working conditions and support in their demanding work.

Keywords: Nordic welfare state, New public management, Eldercare, Care worker, Work environment, Manager support

Introduction

Two basic principles guide eldercare policy in the Nordic countries. First, that care of older people is a public responsibility—although the contribution of family care is extensive, it is not mandatory or laid down in family laws—and second, that care should be provided by trained and qualified staff (Anttonen and Sipilä 1996). Fundamental to the understanding of these welfare service occupations is that care work is created in the encounter between the care worker and the person being cared for (Szebehely 2005). Good care work is based on rationality of caring (Waerness 1984); it is built on relationship and familiarity and an understanding of the older person’s wishes and often fluctuating needs, which makes continuity of staff central to the delivery of quality care (Astvik 2003). Research has demonstrated that staff continuity is the most desired quality attribute from both older people and care workers (Edebalk et al. 1995; Rostgaard and Thorgaard 2007). Hence, it is a major challenge for eldercare employers to recruit, support and—above all—retain care staff.

The quality of care is closely related to the quality of work; care workers cannot provide good quality care unless they have reasonable working conditions. Not being able to provide ‘good enough’ care in accordance with the client’s needs has been reported to be a heavy strain in care work and a primary reason for care workers leaving their jobs (Bowers et al. 2003; Gustafsson and Szebehely 2009).

In recent years, the Nordic countries have been exposed to far-reaching organisational and governance changes influenced by the principles of New public management (NPM). These changes have affected the organisation and delivery of care and care workers’ autonomy and opportunity of providing care consistent with their professional values (Vabø 2009). However, in comparative welfare state research there is a lack of research on the impact of these changes on the day-to-day working conditions of paid care workers (Trydegård 2005; Gustafsson and Szebehely 2009).

The aim of this article is to focus on welfare service employees in times of change and reorganisation by studying eldercare workers’ experiences of their working conditions in two different care settings, home care and residential care, in four Nordic countries, Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. As many of the NPM ideas contradict the basic principles of the traditional Nordic welfare state model, it is crucial to study the consequences of these reforms in the Nordic countries and to explore the implications in different national contexts. The following research questions will be addressed:

In recent years, what changes have Nordic care workers experienced in their working conditions and in their opportunities to provide good quality care?

How do care workers evaluate their present working environment and its impact on their wellbeing and their willingness to remain in the job?

What factors are associated with care workers considering quitting their jobs?

Is it possible to identify positive counterweights to the negative experiences of a demanding working environment?

This article is structured as follows: after a description of the data used for the analysis, the ongoing shifts in the Nordic welfare state model are outlined along with their implications for daily care work. This is followed by an account of the care workers’ experiences of change in their working conditions. Next follows an analysis of the care workers’ assessments of their working conditions and effects on their wellbeing and motivation for staying in the job. Bivariate and multivariate analyses to identify factors associated with care workers considering quitting are reported as well as an analysis of what difference support from managers makes in these circumstances. Finally, the results of the study are summarised and implications of the findings are discussed.

The data base

The data used in this article is taken from the NORDCARE project, whereby a survey was carried out in 2005 by researchers from Denmark, Finland, Norway and Sweden. A questionnaire was sent to a random sample from the membership lists of care workers’ unions in the four countries, 1200 in each country. Response rates varied between 67 and 77%.1 This article focuses on an analysis of the survey data from 2,583 care workers in eldercare, 958 working in home care and 1,625 in residential care.2 These respondents were care workers employed in publicly funded eldercare services, including job categories such as home helpers, assistant nurses, care aides, nurse’s aides and practical nurses (registered nurses were not included) and the vast majority (98%) were women. The greater part (94%) had a public employer; the remaining 6% were employed by a private (tax-funded) provider.3 Of the total sample, about 20% had no or only a short period of care training (less than one year), 44% a medium length of training (1–2 years) and 36% had a longer period of care training (more than 2 years). The four countries differed significantly in this respect with half of the Finnish care workers having had more than 2 years of training, compared to roughly one-third in the other three countries. Also in Finland, care work was mostly a full-time job with 90% of the Finnish respondents working full-time compared to 30–40% in the other three countries.4

The respondents represented an experienced work force: about 85% of the respondents had more than 5 years of care work experience, 70% more than 10 years, and 36% had more than 20 years of experience in care work. Our respondents were unionised, as are the vast majority of Nordic care workers, thereby having more stable working conditions and job security than non-unionised workers. The greater part was born in Scandinavia (87–99%); the largest proportion of workers born abroad was registered in the Swedish sample.5

Data were analysed using bivariate and multivariate (logistic regression) analysis methods.

The changing context of care work

According to the traditional Nordic welfare state model, services and care are widely available and of high quality, they are publicly funded and mostly publicly provided (Sipilä 1997; Daly and Lewis 2000). In the last two decades, however, the Nordic welfare states have been under strain and transformation, and these changes have been especially noticeable in eldercare. A growing older population has put pressure on public resources, while financial crises have enforced restrictions on the public supply of eldercare. To increase efficiency and productivity, market inspired organisational and institutional changes have been introduced, commonly known as NPM. In this model, the ‘old’ public administration model is replaced by models from the private sector. The imperative is for public organisations to become ‘businesslike’ where financial management is stressed. Managers are to be the driving forces for increased productivity and efficiency, acting as business entrepreneurs and they are expected to ‘produce value for money’ (Clarke and Newman 1997). Other vital components of the NPM are competition (between public and private providers), contracts (about the services to be provided and their quality), freedom of choice (for users or ‘customers’) and, most importantly, cost control (Hood 1998; Pollitt and Boucaert 2000; Vabø 2007).

As a consequence of these ideas a purchaser–provider split has been introduced in the Nordic municipalities. This is a precondition for outsourcing publicly financed care to private providers through competitive tendering and consumer-choice models. Public and private providers are supposed to compete, on either price or quality. A needs assessment is carried out by a (municipally employed) care assessor, and care is then purchased from either a public or a private provider. In municipalities where consumers’ choice is introduced, the older persons choose the provider they prefer. Elder care is mainly publicly financed by taxes; the user pays only a fraction of the costs, and the user fee is the same, whether the provider is public or private (and Danish long-term care is free of charge, both in residential settings and in the user’s own home (NOSOSCO 2009)).

This new public managerialism has implications not only in regard to the organisation of care but also impacts significantly on the day-to-day care work (Clarke and Newman 1997), especially in home care services. The work tasks are laid down in contracts with tight time-frames and instructions as to how the quality criteria are to be achieved. As a consequence, care work has become increasingly standardized, with laid down rules in manuals and pre-regulated at an organisational level at a distance from the care worker and the care recipient. Research has indicated that this has undermined the care workers’ professional autonomy and qualifications. It has also impacted on and hindered daily negotiations between the care recipient and the care worker about what tasks should be done and how the care should be provided (Vabø 2005; Dybbroe 2008; Tainio and Wrede 2008; Dahl 2009).

NPM-reforms in the Nordic countries

Sweden was the first of the Nordic countries to introduce NPM-inspired organisations in eldercare in the early 1990s. By the middle of the first decade of the 2000s, more than 80% of Swedish municipalities used a purchaser–provider split model to open up the market for private care providers and promote competition. Today, about 19% of publicly funded eldercare (home care as well as residential care) is provided by private agencies, mostly by large for-profit companies (NBHW 2011). An increasing number of municipalities are introducing a consumer-choice model (primarily in home care, but in some municipalities also in residential care), where authorized private care providers compete with public eldercare units by the quality they can offer the individual consumer. Standardized quality assurance is stressed, and authorities have placed emphasis on municipal comparisons of quality indicators for benchmarking purposes (Trydegård and Thorslund 2010).

In 2003, the Danish municipalities were required by law to offer home care recipients a free choice of provider, and more than eight out of ten municipalities have split their organisation in a purchaser–provider model. NPM in Denmark has become strongly connected to the standardization of services by means of time control, codification and governance of details (Dahl 2009). A ‘common language’ has been introduced along with a standardized catalogue of ‘care products’ resulting in an intense debate among Danish care workers, who have remonstrated—by means of street demonstrations and strikes—against what they call ‘bar-code-tyranny’ and standardized work tasks (Petersen 2008). The care workers have to handle their tasks efficiently in a narrow time schedule and according to contractual standards. Their role is to act as a buffer between care recipients and the system, balancing the older person’s needs with society’s wish to limit expenses. According to Hansen (2008), many Danish care workers are worn out and leave their work before retirement age.

In Norway, it is mainly the bigger cities that have adopted NPM models. In her thorough research on these new steering ideals in home care services, Vabø (2007) draws attention to the Norwegian care workers’ silent resistance to top-down-steering principles. Instead of following detailed working instructions decided by a care manager at a distance from the day-to-day care work, the care workers hold on to their traditional welfare-professional identity and provide care according to their own principles, thereby masking to some extent the effects of these reforms on the care recipients. Norwegian care workers are also critical of the standardized quality measures leading to increased administrative tasks such as demand for documentation, which takes time away from the ‘real care work’.

In Finland, NPM was introduced at a slightly slower rate (Vabø 2005). In recent years, however, Finnish researchers report that the traditional Nordic care regime has been influenced by neoliberal policy trends, emphasizing efficiency, competition and cost restraint (Henriksson and Wrede 2008). The public sector is being reorganised with a purchaser–provider split opening up for the private market, and the introduction of a voucher system (Kröger 2011), and in 2007, 30% of care staff was employed outside the public sector (Anttonen and Häikiö 2011, p. 15). As a consequence of the contracting out of care services, care has increasingly been split up in time-limited tasks, assuming that there is a rational way of performing tasks. This ‘tyranny of routines’ has changed both the contents and the rhythm of the work and undermined the care workers’ own understanding of how their work should be carried out. Studies have shown that Finnish home care workers feel frustrated not to be able to manage work in a satisfactory way within the allocated time (Tainio and Wrede 2008).

Care workers and their working conditions

In numerous studies and theoretical analyses researchers have demonstrated that caring and care work—paid as well as unpaid—are characterized by a combination of manual, intellectual and emotional work (Daly and Szebehely 2011). Care work includes both manual household tasks like cleaning, laundry and cooking as well as personal care such as bathing and dressing. Important aspects are emotional and social support, and therefore a good relationship between the care worker and the person being cared for is essential, which takes time and skill to develop. Further, it has been found that care workers find their work meaningful and rewarding but at the same time demanding and burdensome (Trydegård 2005). International studies have demonstrated a high incidence of work-related poor health, stress and burnout, leading to early retirement and high turnover in long-term care occupations (Colombo et al. 2011).

For all Nordic countries, researchers report that care workers are increasingly subjected to time pressures. It has been found that not having enough time to provide good quality care generates problems in the working environment. Care workers feel inadequate and frustrated when they cannot provide the older person with the care they consider essential and in accordance with care rationality. High levels of absenteeism, due to sickness, and difficulties in recruiting staff on a permanent or temporary basis have also been reported in the Nordic eldercare research (Dellve 2003; Trydegård 2005; Elstad and Vabø 2008; Daly and Szebehely 2011). Despite these insights there is a lack of empirical studies on the impact of the ongoing organisational changes of the welfare services.

An often used theoretical frame for studies of psychosocial work environment is the ‘Demand-control-model’ introduced by Karasek and Theorell (1990). People who experience high work demands, e.g. a heavy work-load or time pressure, and at the same time lack control over their work, i.e. limited decision latitude and poor opportunity to use their professional skills, are regarded as having a high-strain job, and are at risk of psychological stress and physical illness. Being responsible for the well-being of other people is a special stressor, and the job of nurse’s aide has been shown to be one of the most exposed to this kind of high level work strain (idem, p. 43). For a healthy work environment, the work demands—quantitative and qualitative—must be balanced by control over and discretion within the work situation. Another dimension in the work environment is social support, e.g. from supervisors and colleagues, which might counteract a stressful work situation (Johnson 2008). Support from supervisors and managers has proved to be especially important in human service work, particularly in times of organisational change (Fläckman 2008) and is also a strong factor for maintaining health in the long run (Aronsson and Lindh 2004).

Nordic care workers’ experiences of change

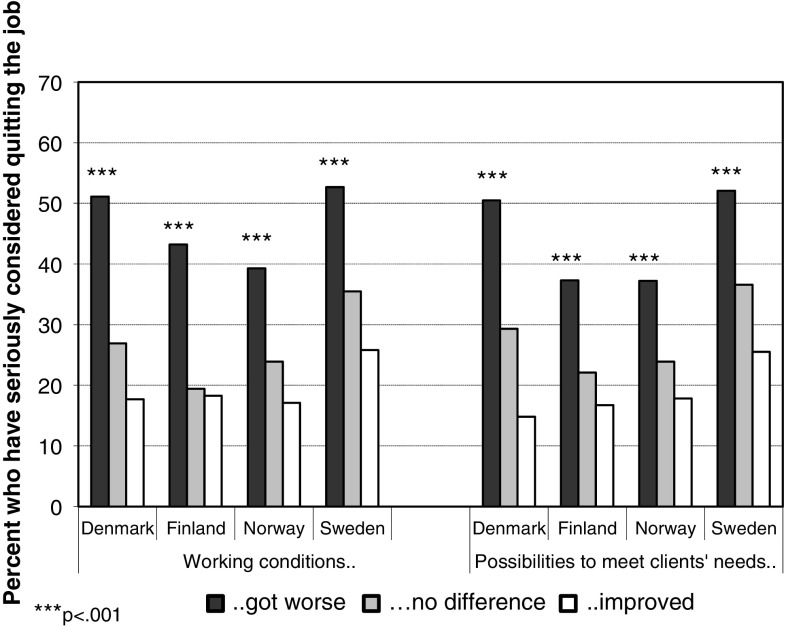

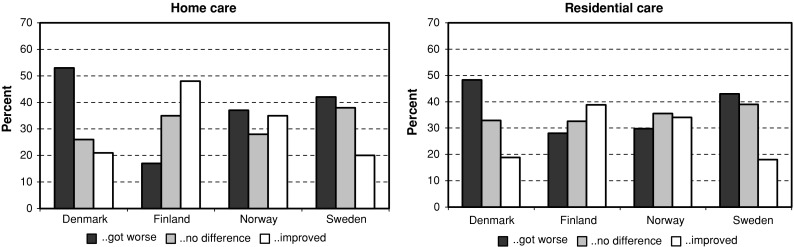

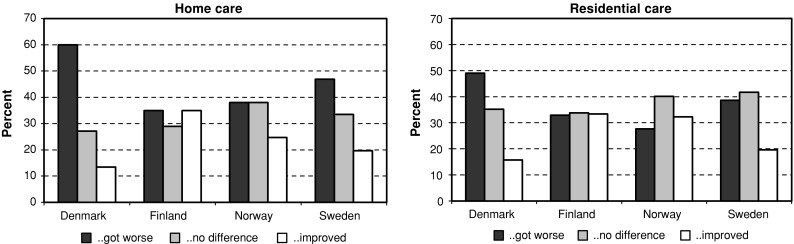

In the NORDCARE project, we used two questions to explore the Nordic care workers’ experience of changes in the care context: “Would you say that your working conditions have improved or got worse in recent years?” and “Would you say that the opportunity for you to meet the clients’ needs has improved or got worse in recent years?” The response alternatives were in both cases: “Mainly improved”, “No difference” and “Mainly got worse”. Figures 1 and 2 demonstrate the assessments from care workers with more than 1 year of experience from the care work (N = 2,555).

Fig. 1.

Experienced change in working conditions

Fig. 2.

Experienced change in the opportunities to meet clients’ needs of care

Figures 1 and 2 illustrate that the care workers’ assessment of change varies between countries and care settings. More care workers in Denmark and Sweden report changes for the worse both in working conditions and in regard to their opportunity to meet clients’ needs, especially in home care. Almost 60% of the Danish home care workers think that their opportunity to meet clients’ needs has deteriorated. As previously mentioned, the organisational changes have been most marked in Denmark and Sweden, and at the time when the NORDCARE survey was conducted, the Danish care workers were offering powerful resistance towards the new ways of organising care (Petersen 2008), which might be reflected in the Danish findings. In Finland and Norway, a larger proportion of the samples consider that the changes have been for the better. Only 17% of the Finnish home care workers think that working conditions have got worse, while almost half of them think they have improved—from what level we don’t know, though (Finland was seriously affected by the economic crisis in the 1990s (Kautto 2000), which may have led to tougher demands on work in the welfare sector).

Fig. 3.

Care workers considering quitting the job by change in working conditions and in opportunities to meet clients’ needs; home care and residential care merged %

Arduous working conditions

Many studies of work environments have shown that high demands in combination with low level of control, few opportunities for developing and learning and weak support in the job constitutes a difficult work situation that is hazardous to workers’ health and wellbeing (Karasek and Theorell 1990; Aronsson and Lindh 2004). Table 1 demonstrates the Nordic care workers’ assessment of their working conditions from these aspects.

Table 1.

Nordic care workers’ assessment of their working conditions %

| Denmark | Finland | Norway | Sweden | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | |

| Have too much to doa | 30 | 30 | 28 | 50 | 32 | 38 | 34 | 40 |

| Feel inadequate towards clients’ needsa | 25 | 20 | 25 | 33 | 24 | 18 | 23 | 32 |

| Hard to affect the daily workb | 55 | 34 | 55 | 67 | 62 | 67 | 67 | 53 |

| Poor possibilities to develop in the workb | 66 | 70 | 46 | 55 | 68 | 81 | 85 | 80 |

| Sparse meetings with managerc | 36 | 59 | 19 | 10 | 48 | 66 | 70 | 83 |

| Weak support from managerb | 52 | 54 | 57 | 59 | 45 | 52 | 60 | 66 |

aMost often. Other response alternatives: sometimes, rarely, never

bSometimes, rarely, never. Other response alternative: most often

cOnce a month, more rarely or never. Other response alternatives: almost every day; once a week

Care work has been shown to be one of the most demanding fields in the labour market, both physically and mentally (for an overview of the Nordic research, see Trydegård 2005). This was also confirmed in the NORDCARE study. Table 1 illustrates that the workload is heavy—between 28 and 50% of care workers declare that they most often have too much to do; here the highest figures come from Finnish residential care workers. Furthermore, about 50% report that they are understaffed on a daily or weekly basis (not shown in the table), findings which should be considered in the light of the high rate of the absence due to illness and difficulties in recruiting staff as reported from Nordic eldercare data (Elstad and Vabø 2008). For care workers, an essential factor in the psychosocial work environment is the feeling of doing a good job and being appreciated for their work. Hence, it is a problem that between one-fifth and one-third of care workers in the study state that they most often feel inadequate because they cannot provide the care recipients with the help they consider reasonable.

To lack control over one’s work is a heavy strain in today’s care work. A majority of the informants reported limited influence on how their daily work was organised and carried out and few opportunities to develop in their profession. The Swedish figures are most noteworthy in regard to opportunities for professional development: 80–85% of the Swedish care workers stated that they only sometimes, seldom or never felt that they had the opportunity to develop in their profession.

Turning to care workers’ experiences in regard to support, Finnish care workers reported that they have close contact with their managers, especially in residential care. This contrasts with the other countries, where the majority of care workers meet their managers only once a month or less—in Sweden as many as 70% of workers in home care and 83% in residential care meet with their managers once a month or less. The majority of the care workers in all four countries feel they receive weak support from their managers.

So, care workers report a high level of work demands, low control over their work and lack of support from their managers—a combination which has been demonstrated to be a leading factor in job stress and fatigue (Karasek and Theorell 1990).

From Table 2 we can see that between 59 and 75% of care workers feel physically tired always or often at the end of a working day. This was particularly pronounced among Finnish care workers in residential care. Between 31 and 43% always or often feel mentally exhausted (again the highest figures appear in Finnish residential care, this time in addition with Sweden). Significantly, a substantial proportion (between 21 and 43%) of all the care workers state that during the last year they have seriously considered quitting their jobs. Strangely enough, the Finnish care workers who reported more arduous working conditions, are the least likely to have considered quitting their job, which might be related to the situation in the Finnish labour market at the time of the study.

Table 2.

Consequences of arduous working conditions in Nordic care workers %

| Denmark | Finland | Norway | Sweden | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | Home care | Resid. care | |

| Physically tireda | 59 | 61 | 59 | 75 | 66 | 69 | 62 | 67 |

| Mentally exhausteda | 32 | 31 | 37 | 43 | 35 | 36 | 42 | 42 |

| Have seriously considered quitting the jobb | 34 | 43 | 21 | 27 | 28 | 26 | 42 | 40 |

aAlmost always or often. Other response alternatives: sometimes, rarely, never

bYes. Other response alternative: No

Why do care workers want to quit the job?

As stated earlier, continuity of care is an important quality indicator in eldercare. It has also been demonstrated that care recipients highly value having tasks performed in the same way, at the same point of time and by the same care worker. Consequently, it would seem that continuity of staff is a prerequisite to providing good quality care. In this context it is problematic that so many of the participants in this study have seriously considered quitting their jobs. What are the reasons behind this, and can it be prevented?

Our analysis demonstrated that among those care workers who have reported that they feel mentally exhausted after a working day, a significantly larger proportion have seriously considered quitting their jobs. The analysis gave roughly the same result when we chose “feeling physically tired after a working day” or “feeling inadequate to the clients’ needs” as the independent variable.

As mentioned above, previous research as well as the NORDCARE data indicates that Nordic care workers report to have been exposed to changes in the organisation of care and in the day-to-day work. Do those who have experienced changes for the worse also report the desire to quit their job? In the following analysis (see Fig. 3) those working in home care and residential care settings are merged.

Not surprisingly, those who have experienced changes for the worse in working conditions as well as in their opportunity to meet clients’ needs have significantly more often considered quitting the job; twice as many compared to those who have experienced a change for the better. Perhaps, thoughts of quitting can serve as a safety valve when the job seems to deteriorate in different ways.

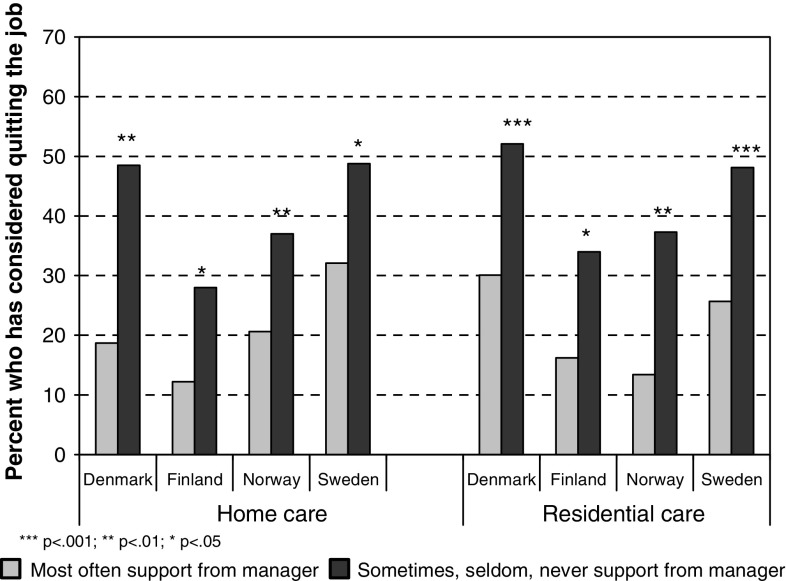

The importance of support from managers

In studies of psychosocial work environment and job stress, it has been demonstrated that support from leader and colleagues is a factor that might reduce stress (Johnson 2008). As shown above (see Table 1), quite a large proportion of care workers seldom meet their managers, and the majority stated that they only sometimes, seldom or never felt support from their managers. Figure 4 shows that there are significantly fewer who have considered quitting their jobs amongst care workers who receive support from their managers.

Fig. 4.

Care workers considering quitting the job by level of support from manager %

Care workers often work alone with the care recipient, especially in home care settings, and have to make difficult professional decisions on their own. It is easy to understand that you feel safer if you have a supportive manager at your back, even if the supervision and support is given ‘at a distance’, which is the case in home care.

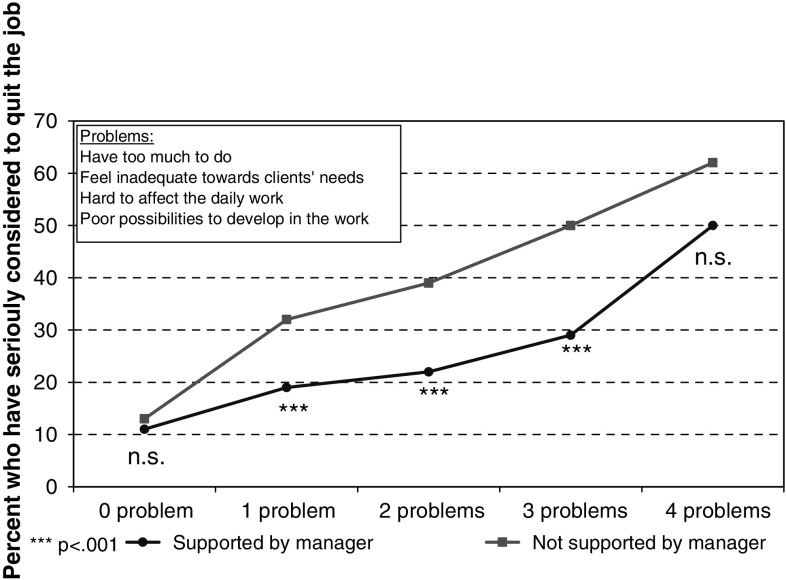

A further step in the analysis was taken to explore if a manager’s support might act as a counterweight in a situation with multiple work-related problems. Figure 5 displays the average pattern of how the percentage of care workers considering quitting their jobs grows with increasing numbers of reported work problems. For this analysis the most frequently stated problems were used: having too much to do, feeling inadequate in dealing with clients’ needs, not being able to affect the daily work and poor possibilities to develop professionally. Here, the samples from all four countries and both care settings were merged.

Fig. 5.

Care workers considering quitting the job by support from manager with different numbers of problems (countries and care settings merged)

A number of conclusions can be drawn from the diagram in Fig. 5. First, and not surprisingly, the more problems the care workers have experienced in the working environment, the more likely it is that they will consider quitting their jobs. Second, among those who have the same number of problems fewer consider quitting if they have support from their managers. Third, those who have reported no problems in their work do not seem to need a manager’s support to stay in their job, and fourth, workers with four problems consider quitting even if supported by a manager.

To further explore possible factors related to care workers considering quitting their jobs, a multivariate analysis was made, presenting estimates from logistic regressions (Table 3). The analysis shows that the odds ratio for having considered quitting is about double in Denmark and Sweden compared to Finland and Norway. However, whether the worksite is home care or residential care does not seem to make any difference, nor does the number of years in care work. People who have been working in eldercare for 20 years or more have considered quitting their jobs to the same extent as those who have had less experience. It is noteworthy that care workers with longer periods of professional training seem to have higher likelihood of having considered quitting their jobs compared to those with short or medium periods of training.

Table 3.

Odds ratios for likelihood of considering to quit the job by country, care setting, years in care work, professional training, change in working conditions and in opportunities to meet clients’ needs, support from manager and number of work-related problems

| Odds ratio | Sign. | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Finland | 1 | |

| Denmark | 2.035 | 0.000 |

| Norway | 1.134 | 0.379 |

| Sweden | 1.925 | 0.000 |

| Care setting | ||

| Home care | 1 | |

| Residential care | 1.103 | 0.332 |

| Years in care work | ||

| ≤5 | 1 | |

| 6–9 | 1.418 | 0.418 |

| 10–19 | 1.110 | 0.469 |

| 20+ | 0.927 | 0.604 |

| Professional training | ||

| <1 year | 1 | |

| 1–2 years | 1.114 | 0.412 |

| >2 years | 1.310 | 0.050 |

| Change in working conditions | ||

| For the better | 1 | |

| No difference | 1.047 | 0.763 |

| For the worse | 1.668 | 0.002 |

| Change in possibilities to meet clients’ needs | ||

| For the better | 1 | |

| No difference | 1.197 | 0.250 |

| For the worse | 1.503 | 0.017 |

| Support from manager | ||

| Yes | 1 | |

| No | 1.954 | 0.000 |

| Work-related problems | ||

| 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 2.135 | 0.001 |

| 2 | 2.712 | 0.000 |

| 3 | 3.714 | 0.000 |

| 4 | 6.947 | 0.000 |

Significant results in italics N = 2414

The estimates express the odds of having considered quitting the job for each category within each variable compared to a reference category set to 1, and controlling for the other variables in the analysis

The analysis also shows that care workers who have experienced changes for the worse in working conditions are much more likely to have considered quitting their jobs, compared to those who think working conditions have changed for the better. The same goes for those who report changes for the worse in their opportunity to meet clients’ needs. Not feeling supported by one’s manager doubles the odds ratio for having considered quitting; a result that supports the analysis outlined in Figs. 4 and 5.

However, what makes the big difference in regard to the odds of quitting care work is the number of reported work-related problems. Compared to those who have not reported any problems at all, the figures for those workers having considered quitting the job are twice as high for those with one reported problem, three times higher for those with two problems, four times higher for those with three and as much as seven times higher for those with four problems.

Concluding discussion

The Nordic welfare state is moving away from its traditional model. NPM principles have impacted both on the organisation and the provision of publicly financed welfare services, eldercare in particular. Research in Nordic countries illustrates that care work has been split into small, time-limited units, making it impossible for care workers to adjust care to the older persons’ varying and shifting needs. Care workers have also experienced time pressures and constraints, an increased work-load and reduced opportunities to use their professional skills and knowledge. From the care workers perspective, the reforms that have been implemented are in conflict with what is generally believed to be good care practice or care rationality (Vabø 2005, 2007; Gustafsson and Szebehely 2009).

The findings from the NORDCARE study, reported in this article, confirm this picture. In all four Nordic countries, in home-based as well as residential-based eldercare, a number of features of the care workers’ working conditions have been shown to lead to stress and fatigue due to a combination of high demands, low control and little managerial support (Karasek and Theorell 1990; Fläckman 2008). Changes for the worse in working conditions and in the opportunity of care workers to meet clients’ needs were reported from all four countries, mostly from Denmark, where the reforms were very controversial at the time of the study, and Sweden, where the organisational changes were first implemented and most widespread. The analysis illustrated that twice as many care workers who have experienced changes for the worse have considered quitting their jobs, compared to those who think their job has improved; in Denmark and Sweden this figure is 50% or higher. Furthermore, the likelihood of having considered quitting the job was as high among those who have been working in eldercare for many years as among those with less seniority, and care workers with a long period of training for the job were also showing increased odds of having considered quitting. One possible interpretation of these findings is that the prerequisites for care work have changed in a way that has led to particularly experienced and well-educated care workers finding it impossible to perform their work in a manner consistent with their professional values (cf. Tainio and Wrede 2008). In her analysis of Danish care work Dybbroe (2008) draws a similar conclusion:

The standardisation and manualisation of the care work has led to de-qualification of care workers—the professionals do not have to know so much. Work is becoming less dependent on the learning and development of the care worker and more dependent on political and institutionally directed constructions of caring practice (p. 44).

Obviously, the welfare state in its new organisational forms is experiencing a considerable risk in the form of a drain of experienced and competent care workers, in turn resulting in a threat to the quality of care.

Why do care workers consider leaving their jobs? The most striking—and perhaps not surprising—result of the analysis was the fact that care workers with multiple problems at work were much more likely to have considered quitting their jobs, and the likelihood increased with the number of problems they reported. Care workers reporting four problems at work—having too much to do, not being able to influence the work or develop in the job, and feeling inadequate in the care situation—had seven times higher odds of having considered quitting their jobs, compared to those who had not reported these problems. Furthermore, the analysis showed that care workers who did not feel support from their managers had double the odds of considering quitting their jobs. The conclusions drawn from these results seem obvious: employers and managers, whether public or private, who want to keep their care workers, must try to minimize problems at work and give support to workers in the often difficult and demanding care work. In care organisations, managers must have the time and resources to be present and to support the care staff and be able to identify and address problems at the workplace, especially in times of change (Fläckman 2008). In recent years, the jobs of managers and their areas of responsibility have enlarged substantially, and managers have assumed charge of increasing numbers of care workers (Wolmesjö 2005). In NPM-inspired organisations they must also be more focused on financial management, in particular cost cutting, and act like ‘business entrepreneurs’. Thus, the managers’ jobs have changed, and they are increasingly less present and available to support their staff.

Dybbroe (2008) regards the care occupations as fundamental for the creation and maintenance of welfare, as they identify themselves professionally with the political and ethical values of the Nordic welfare state. Hence, she argues, the loss of care staff is an important part of the crises of the welfare state services. According to Nordic legislation, the state has the ultimate responsibility to see to that good quality care is available to all older people according to need. The Nordic welfare states with growing older populations are facing challenges in retaining staff in eldercare services and making sure they have good working conditions and support in their demanding work.

This article was based on empirical material collected in a cross-sectional study in 2005. Obviously, there are limitations as to what conclusions can be drawn about change and consequences of reforms from such material—a longitudinal approach certainly would have captured this more effectively. Our study shows that in 2005 the NPM-inspired reforms had started to affect care workers’ working conditions. Recent studies from the Nordic countries indicate that these reforms continue to gain ground at an increasing rate (Anttonen and Häikiö 2011; Fersch and Jensen 2011; Vabø and Szebehely 2012 forthcoming). This calls for further studies of the impact of ongoing organisational changes on care workers’ working conditions.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research programme financed by the Swedish council for working life and social research, ‘Transformations of care: living the consequences of changing public policies’, and the strand ‘Care in ageing and diversifying societies’ within the Nordic excellence centre REASSESS. The author thanks Professor Marta Szebehely, Stockholm University, for valuable advice in the course of writing.

Footnotes

Response rates: Denmark 77%; Finland 72%; Norway 74%: Sweden 67%.

N in home care: Denmark 333; Finland 169; Norway 244; Sweden 212; N in residential care: Denmark 409; Finland 449; Norway 441; Sweden 326.

No comparative analysis is made between publicly and privately employed care workers, as the number of privately employed respondents was limited.

Our sample is in line with statistics on the Finnish labour market, indicating that Finnish women are more likely to work full-time compared to the other Nordic countries (OECD 2010). This is the case also in the Health and Social care sector (Norman et al. 2009).

In contrast to other European countries, there is no active recruiting of migrant care workers in Sweden—most of the Swedish care workers born in other countries have migrated for other reasons, many as refugees.

References

- Anttonen A, Häikiö L (2011) Care ‘going market’: Finnish elderly-care policy in transition. Nordic journal of social research. Special issue: Welfare-state change, the strengthening of economic principles, and new tensions in relation to care in Europe

- Anttonen A, Sipilä J. European social care services: Is it possible to identify models? J Eur Soc Policy. 1996;6(2):87–100. doi: 10.1177/095892879600600201. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aronsson G, Lindh T (2004) Långtidsfriskas arbetsvillkor. En populationsstudie (Long-term healthy people’s working conditions. A population study). No 2004:10. Arbetslivsinstitutet, Stockholm

- Astvik W (2003) Relationer som arbete. Förutsättningar för omsorgsfulla möten i hemtjänsten (Relating as a primary task. Prerequisits for sustainable caring relations in home-care services). Dissertation, Stockholm University. Arbetslivsinstitutet, Stockholm

- Bowers BJ, Esmond S, Jacobson N. Turnover reinterpreted: CNAs talk about why they leave. J Gerontol Nurs. 2003;29:36–43. doi: 10.3928/0098-9134-20030301-09. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarke J, Newman J. The managerial state. London: Sage; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Colombo F, Nozal AL, Mercier J, Tjadens F. Help Wanted? Providing and Paying for Long-Term Care, OECD Health Policy Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl HM. New public management, care and struggles about recognition. Crit Soc Policy. 2009;29:634–654. doi: 10.1177/0261018309341903. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Lewis J. The concept of social care and the analysis of contemporary welfare states. Br J Sociol. 2000;51(2):281–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-4446.2000.00281.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly T, Szebehely M (2011) Unheard voices, unmapped terrain: care work in long-term residential care for older people in Canada and Sweden. Int J Soc Welf. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2011.00806.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dellve L (2003) Explaining occupational disorders and work ability among home care workers. Dissertation, Göteborg University, Göteborg

- Dybbroe B. Crisis of care in a learning perspective. In: Wrede S, Henriksson L, Høst H, Johansson S, Dybbroe B, editors. Care work in crisis. Reclaiming the Nordic ethos of care. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2008. pp. 41–48. [Google Scholar]

- Edebalk PG, Samuelsson G, Ingvad B. How elderly people rank-order the quality characteristics of home services. Ageing Soc. 1995;15:83–102. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X00002130. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elstad JI, Vabø M. Job stress, sickness absence and sickness presenteeism in Nordic elderly care. Scand J Public Health. 2008;36:467–474. doi: 10.1177/1403494808089557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fersch B, Jensen PH (2011) Experiences with the privatization of home care: evidence from Denmark. Nordic journal of social research. Special issue: Welfare-state change, the strengthening of economic principles, and new tensions in relation to care in Europe

- Fläckman B (2008) Work in eldercare—staying or leaving. Caregivers’ experiences of work and support during organizational changes. Dissertation, Karolinska institutet, Stockholm

- Gustafsson RÅ, Szebehely M. Outsourcing of eldercare services in Sweden: effects on work environment and political legitimacy. In: King D, Meagher G, editors. Paid care in Australia: politics, profits, practices. Sydney: University Press; 2009. pp. 81–112. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen HK. Neglected opportunities for personal development: care work in a perspective of lifelong learning. In: Wrede S, Henriksson L, Høst H, Johansson S, Dybbroe B, editors. Care work in crisis. Reclaiming the Nordic ethos of care. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2008. pp. 75–96. [Google Scholar]

- Henriksson L, Wrede S. Care work in the context of a transforming welfare state. In: Wrede S, Henriksson L, Høst H, Johansson S, Dybbroe B, editors. Care work in crisis. Reclaiming the Nordic ethos of care. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2008. pp. 121–130. [Google Scholar]

- Hood C (1998) The Art of the state—culture, rhetoric and public management. Oxford University Press, Oxford

- Johnson JV. Globalization, workers’ power and the psychosocial work environment—is the demand–control–support model still useful in a neoliberal era? Scand J Work Environ Health. 2008;Suppl. 6:15–21. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Theorell T (1990) Healthy work: stress, productivity and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books Inc., New York

- Kautto M (2000) Two of a Kind? Economic crises, policy responses and well-being during the 1990s in Sweden and Finland. SOU 2000:83. Fritzes, Stockholm

- Kröger T (2011) The adoption of market-based practices within care for older people: is the work satisfaction of Nordic care workers at risk? Nordic journal of social research. Special issue: Welfare-state change, the strengthening of economic principles, and new tensions in relation to care in Europe

- NBHW, National Board of Health and Welfare . Äldre och personer med funktionsnedsättning—regiform mm för vissa insatser år 2010 (Management Form for Certain Services to Older persons and to Persons with Impairments) Stockholm: Socialstyrelsen; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Norman TM, Rønning E, Nørgaard E. Challenges to the Nordic welfare state—comparable indicators. Copenhagen: NOSOSCO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- NOSOSCO, Nordic Social-statistical Committee . Social protection in the Nordic countries: scope, expenditure and financing 2008/2009. Copenhagen: NOSOSCO; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- OECD (2010) OECD Family data base. http://www.oecd.org/els/social/family/database

- Petersen JH (2008) Hjemmehjælpens historie. Idéer, holdinger, handlingar (The history of home help. Ideas, attitudes, actions). Syddansk universitetsforlag, Odense

- Pollitt C, Boucaert G. Public management reform—a comparative analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Rostgaard T, Thorgaard C (2007) God kvalitet i ældreplejen. Sådan vægter de ældre, plejepersonale og visitatorer (Good quality in eldercare. How older persons, staff and assessors evaluate quality). SFI 07:27. SFI—Det Nationale Forskningscenter for Velfærd, Copenhagen

- Sipilä J (ed) (1997) Social care services: the key to the Scandinavian welfare model. Avebury, Aldershot

- Szebehely M. Dilemmas of care in the Nordic welfare state. In: Dahl HM, Eriksen TR, editors. Care as employment and welfare provision—child care and eldercare in Sweden at the dawn of the 21st century. Aldershot: Avebury; 2005. pp. 80–97. [Google Scholar]

- Tainio L, Wrede S. Practical nurses’ work role and workplace ethos in an era of austerity. In: Wrede S, Henriksson L, Høst H, Johansson S, Dybbroe B, editors. Care work in crisis. Reclaiming the Nordic ethos of care. Lund: Studentlitteratur; 2008. pp. 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Trydegård GB (2005) Äldreomsorgspersonalens arbetsvillkor i Norden—en forskningsöversikt (Working conditions of eldercare staff in the Nordic countries: A research overview). In: Szebehely M (ed) Äldreomsorgsforskningen i Norden. En kunskapsöversikt (Nordic eldercare research. An overview). Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, pp 143–195

- Trydegård GB, Thorslund M. One uniform welfare state or a multitude of welfare municipalities? The evolution of local variation in Swedish eldercare. Soc Policy Adm. 2010;44(4):495–511. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9515.2010.00725.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vabø M (2005) New public management i nordisk eldreomsorg—hva forskes det på? (New Public Management in Nordic eldercare: what do researchers focus on?) In: Szebehely M (ed) Äldreomsorgsforskning i Norden. En kunskapsöversikt (Nordic eldercare research. An overview) Nordic Council of Ministers, Copenhagen, pp 73–111

- Vabø M (2007) Organisering for velferd. Hjemmetjenesten i en styringsideologisk brytningstid (Organizing welfare. Home help services in times of steering-ideological changes). Dissertation, Oslo University. NOVA Rapport 11/07, Oslo

- Vabø M. Home care in transition. The complex dynamic of competing drivers of change in Norway. J Health Organ Manag. 2009;23(3):346–359. doi: 10.1108/14777260910966762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vabø M, Szebehely M. A caring state for all older people? In: Anttonen A, Häikiö L, Stefansson K, editors. Welfare state, universalism and diversity. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Waerness K. The rationality of caring. Econ Ind Democr. 1984;5(2):185–211. doi: 10.1177/0143831X8452003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolmesjö M (2005) Ledningsfunktion i omvandling: om förändringar av yrkesrollen för första linjens chefer inom den kommunala äldre- och handikappsomsorgen (Management in transition: on changes of the professional roles of first-line managers in municipal elder- and disability care). Dissertation, Lund University, Lund